30,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- Indian History /

Mughal Empire: Origin, Rise, Administration, Decline

- Updated on

- Mar 9, 2024

The Mughal Empire was one of the most powerful and influential empires in India. The dynasty was the longest-reigning empire in India. From the 16th to the 19th century, the Mughal Emperors left a lasting legacy that still influences Indian culture and history today. In this article, we will delve into the different aspects of the Mughal Empire, exploring how it rose to power and how such a powerful dynasty declined.

Table of Contents

- 1 Origins of the Mughal Empire

- 2 Height of the Mughal Empire

- 3.1 Military Strength

- 3.2 Cultural and Architectural Achievements

- 4 Decline of the Mughal Empire

- 5 Legacy of the Mughal Empire

- 6 Key Emperors of the Mughal Empire:

Origins of the Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was founded in 1526 by Babur , a descendant of the Mongol ruler Genghis Khan and a Timurid Prince. Babur defeated the Sultan of Delhi, Ibrahim Lodhi, at the First Battle of Panipat , establishing the Mughal Empire in India in 1526.

Height of the Mughal Empire

- Under the rule of Emperor Akbar , the Mughal Empire reached its peak in the 16th century.

- Akbar implemented policies of religious tolerance and cultural integration, leading to a golden age of art, architecture and literature in the empire.

- The Mughal Empire under Akbar’s reign was characterized by flourishing trade, advanced infrastructure and efficient governance.

- Until the 7th generation, the Mughal Empire stood as a strong administrative force in Northern India.

- In the expansion of their kingdom, Mughal rulers indulged in battles and sieges with many other kingdoms which included the Battle of Panipat, Battle of Chausa, Battle of Kannauj, Siege of Ranthambore, Battle of Rohilla, Siege of Chittorgarh, etc

Administration and Governance of the Mughal Empire

The administration and governance in the Mughal Administration were streamlined and further disciplined during the rule of Akbar. There lay a ranking system from subedars to tehsildars in the administration.

- Divided into provinces known as “subahs,” each under the control of a governor appointed by the emperor.

- Akbar’s policy of sulh-i kul promoted religious harmony and unity among diverse communities.

- An efficient taxation system based on land revenue helped sustain the empire’s economy.

- The rank system of Mansabdari was also introduced under the Mughal rule

Also Read – Tughlaq Dynasty: Rulers of Delhi Sultanate

Military Strength

- The Mughal army consisted of infantry, cavalry and artillery units and skilled use of war elephants in battles provided a tactical advantage.

- Siege warfare tactics were employed to capture fortified cities and territories.

- According to historical accounts, nearly 911,400 to 4,039,097 infantry and 342,696 cavalry formed the military strength of the Mughal dynasty. The army of the dynasty is termed the largest military on Earth.

Cultural and Architectural Achievements

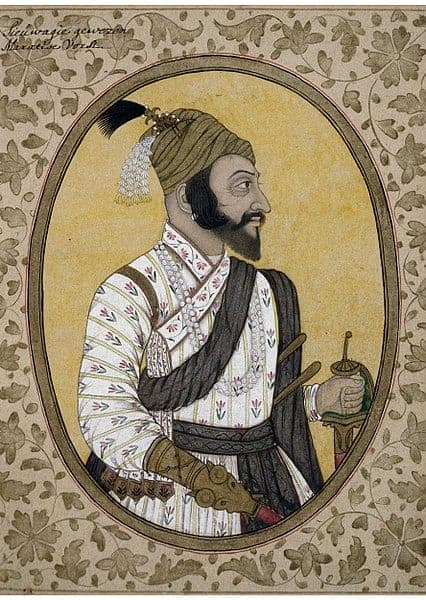

- Patronage of the arts led to the development of Mughal miniature painting and architecture.

- Landmark structures such as the Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi, Agra Fort , Buland Darwaza , Fatehpur Sikri , etc reflect the empire’s architectural intelligentsia and marvels of the period.

- The Urdu language emerged as a blend of Persian, Arabic and local dialects during the Mughal era.

Also Read – Gupta Empire: Rise, Rulers, UPSC Notes

Decline of the Mughal Empire

The decline of the Mughal Empire began in the late 17th century due to internal strife, weak leadership and invasions from foreign powers.

- The empire fragmented into smaller kingdoms, known as the Mughal successor states, which continued to rule over parts of India until the British colonization.

- Aurangzeb’s reign marked the beginning of the empire’s decline due to his strict policies and religious intolerance.

- Continuous invasions by Central Asian and European powers weakened the empire’s military capabilities.

- By the mid-19th century, the British East India Company had significantly reduced Mughal authority.

- The last Mughal ruler Bahadur Shah Zafar II was defeated and had to run to Burma to save his life.

Also Read – Important Notes on the Advent of Europeans in India

Legacy of the Mughal Empire

The Mughal dynasty left a significant impact on Indian society, architecture and culture.

- Mughal architecture, such as the Taj Mahal and Red Fort , exemplifies the grandeur and beauty of the empire’s aesthetic.

- Mughal art and literature, including miniature paintings and Urdu poetry, continue to be celebrated for their artistic achievements.

Also Read – Complete Mughal Empire List: An Overview

Key Emperors of the Mughal Empire:

- Babur (1526-1530): The founder of the Mughal Empire who laid the groundwork for future expansion.

- Akbar (1556-1605) : Known as the greatest Mughal Emperor, Akbar’s reign marked a period of peace and prosperity.

- Jahangir (1605-1627): Jahangir was famous for his love of paintings and a folk tale of the love story between Salim and Anarkali.

- Shah Jahan (1628-1658): Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan is famous for building the Taj Mahal in memory of his wife Mumtaz Mahal.

- Aurangzeb (1658-1707) : Known for his strict Islamic policies and the expansion of the empire through military conquests. Aurangzeb is also called the ruthless ruler among all the rulers.

In conclusion, the Mughal Empire List provides a glimpse into the rich history and grandeur of one of India’s most iconic dynasties. From its humble beginnings to its magnificent achievements, the Mughal Empire’s legacy endures through its architectural wonders, cultural contributions and complex administrative system. Despite facing challenges and eventual decline, the empire’s impact on Indian history and heritage remains significant.

Relevant Blogs

This was all about the Mughal Empire. If you want to know more about topics like this, then visit our general knowledge page! Alternatively, you can also read our blog on general knowledge for competitive exams !

Rajshree Lahoty

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

30,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today.

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

- Modern History

Overview of the Mughal Empire Lesson

Learning objectives

In this lesson, students will delve into the history of the Mughal Empire, exploring its rise under visionary leaders like Babur and Akbar, its architectural marvels, and the factors leading to its decline. They will gain insights into the empire's profound influence on Indian art, culture, administration, and the lasting legacy it left on the subcontinent. Students will have the opportunity to achieve this through choosing their own method of learning, from reading, research, and watching options, as well as the chance to engage in extension activities. This lesson includes a self-marking quiz for students to demonstrate their learning.

How would you like to learn?

Option 1: reading.

Step 1: Download a copy of the reading questions worksheet below:

Step 2: Answer the questions by reading the following webpage:

Option 2: Internet research

Download a copy of the research worksheet and use the internet to complete the tables.

Option 3: Watch video

Step 1: Download a copy of the viewing questions worksheet below:

Step 2: Answer the set questions by watching the following video:

Al Muqaddimah. The History of the Mughal Empire .

Watch on YouTube

Test your learning

Extension activities, resources for subscribers.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.3: Gunpowder Empires- Mughals

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 154809

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The Mughal Empire

The last of our three Islamic states of the early-modern era is the Mughal Empire of South Asia. At their peak in the first half of the sixteenth century, the Mughals were perhaps the richest and most powerful regime in the world. Their political origins were discussed in the previous chapter, so here we can again focus on some of the broader social, cultural, and ideological impacts of Mughal imperialism.

Figure 3.3.1: " Map of the Mughal Empire under Babur (1526-30) ," Avantiputra7 , is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 .

Mughal "India"

To make sense of this, it is first necessary to try to separate out the region we call “India” from the nation of India as it exists today. The fact that the Ottoman Empire was eventually broken up into a series of separate nations while India, with the exception of Pakistan and Bangladesh, became a single nation is more a reflection of the arbitrariness by which nations were formed in the modern age than the existence of some inherent Indian-ness. It is common to present the Indian subcontinent as a more or less fully formed sociocultural zone onto which the Mughal invaders imposed themselves. This view derives from the tendency to understand culture as something fixed and immutable when it is really dynamic and adaptable. Indeed, it is not difficult to make the case that those things we identify as “traditional” characteristics of India and Indians were themselves created through the interactions made possible by the establishment of Mughal rule. In other words, we should not think of the Mughal period as a collision between one coherent ethno-religious community and another, but as a time in which new ethnic, religious, and communal identities were constructed and took on meaning that they did not previously have. Categories and concepts like Hindu, Muslim, or caste acquired new meaning and importance even if they were not entirely inventions of the era.

In the First Battle of Panipat in 1526, Babur defeated Sultan Ibrahim Lodi of the Delhi Sultanate. This victory laid the foundation for the establishment of Mughal rule in India until 1857. In 1527, Babur defeated the Rajputs led by Rana Sangha in the Battle of Khanwa. This victory gave Babur control over northern India. Figure 3.3.1 is a physical map of the Indian subcontinent and it shows the areas under Babur's control, which extended from Kabul in modern-day Afghanistan to Peshawar in modern-day Pakistan to Delhi and Agra in northern India. Babur established his capital in Agra.

The Indian subcontinent had no single unified civilization prior to the sixteenth century. This supposedly changed in 1526 with a warrior chieftain named Babur’s defeat of the Sultan of Delhi; this has been routinely accepted as the start of the Mughal empire, although the actual imperial structure formed under Babur’s grandson, Akbar, during the seventeenth century. Although the empire was formed through military conquest, one key aspect of the creation of this empire that differed from other surrounding territories was the lack of subjugation and assimilation of the other tribes. Instead, it offered more equitable opportunities through bureaucracy and local governance, which, in addition to military support, allowed for a more centralized government structure, with satellite local governors to oversee the day-to-day running of the various territories, at least during the seventeenth century. Given the relative peace of this time period, it allowed for more artistry to flourish, as what would be considered the middle and upper classes of society became more conspicuous consumers of this art. This resulted in more wealth flowing throughout the burgeoning empire and why this period is considered the “golden” age of Indian self-rule, at least before the modern time period of history.

To think of the Mughal as a group of Central Asian Muslims who conquered a huge territory occupied by Hindus vastly oversimplifies the actual nature of Mughal conquest and rule while falling back on the simple binaries that I critiqued earlier. In contrast to that simplified view it is vital to note that the initial Mughal victories that first established them on the subcontinent in the early sixteenth century came at the expense of an Islamic sultanate that in various forms had dominated North India since the 13th century. Indeed, many of their greatest rivals would come in the form of other Muslim rulers. One of the most famous campaigns of the emperor Akbar (r.1555-1605), for instance, was waged against the Muslim sultan of Gujarat and his great-grandson Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707), often depicted as a persecutor of Hindus, spent the final quarter century of his life in a mostly failed attempt to conquer the Deccan Plateau of Central India from a variety of Muslim rulers. Conversely, many of the most loyal supporters of the Mughal regime were Hindu elites, including many of Aurangzeb’s top generals. Compared to the Safavid, and even to the Ottoman, Islam was significantly less significant to the nature of Mughal rule. In discussing this issue, Barbara and Thomas Metcalf note that the Mughal regime was, “ ‘Muslim’ in that they were led by Muslims, patronized (among others) learned and holy Muslim leaders, and justified their existence in Islamic terms. ... The unifying ideology of the regime was that of loyalty, expressed through Persianate cultural forms, not a tribal affiliation (like that of the Ottomans), nor an Islamic or an Islamic sectarian identity (like that of the Safavids).”

Traditional histories of the Mughal liked to center the issue of tolerance and intolerance by stressing, for instance, the open-minded tolerant attitude of Akbar versus the more conservative and intolerant policies of Aurangzeb. It is not that there were no differences between the two emperors, but that, like with the Ottoman, the notion of toleration is not the best way to understand those differences. Empires are by nature based on violence, domination, and exploitation. Some more so, some less so. Which groups suffer from their actions and which benefit from the largesse of the imperial elite is varied and complex. In the case of the Mughal, there are many instances that appear to suggest increasing religious persecution across the life of the empire. Successive Sikh gurus were captured and executed by Mughal forces, Hindu temples were destroyed under the orders of Aurangzeb, a decades long war was waged against the Hindu Marathas, and the longstanding exemption of Hindus from taxes on non-Muslims was reversed late in the 17th century. Yet all of these instances can just as easily be explained as part of regular imperial politics. Sikh leaders were targeted because they supported the losing side in a Mughal succession crisis. The Hindu temples were destroyed because they were centers of anti-Mughal resistance. The Marathas had once been allies of the Mughal before they began to assert their independence. The restoration of old taxes was a means to provide revenue to pay for Aurangzeb’s many wars against Muslim rivals in central and southern India. None of this is to justify violence, oppression, or exploitation. It does, however, help us understand these events as a matter of practical politics instead of seeing them as evidence of centuries-old religious conflict. This difference is not a minor thing at a time when Hindu nationalists use stories of persecution under the Mughals to justify their own oppression of the Muslim minority in contemporary India.

The Mughal period should not be seen as a clash between two coherent religious or ethnic communities, one of whom were foreign conquerors and the other conquered natives. Rather the Mughal period was a time in which new imperial structures encouraged many different communities to interact in more intensive ways than ever before. The result of these interactions were varied. As always when humans interact there was a sharing of customs, habits, tastes, and values. As one example, the Bhakti movement, which emphasized devotion to specific gods as a means of salvation, was present in India well before the Mughal conquest yet seems to have been influenced by elements of Islamic doctrine even as it influenced Sufi Islam. In particular, Bhakti poets adopted genres that came out of Persian tradition while Sufi poets seem to have adopted religious ideas and writing styles from Bhakti poets. What emerged from these cultural interactions was not entirely new, since it pulled from much older traditions, but was also not really ancient since it had never existed in that form before. Caste is maybe the best example of this. The notion that Indian social arrangements were determined by one’s membership in a fixed and hierarchically-arranged social group – traditionally named as the Brahmin priests, Kshatriya warriors, Vaishya merchants, and Shudra peasants – was identified by later British imperialists as an ancient and fundamental aspect of Indian society. Recent scholarship, however, suggests that such a social organization had very little impact on the subcontinent until recent centuries. Without getting into the full complexity of the issue, it seems that caste identity only started to be formalized during the Mughal era and only became fixed under British rule. Interestingly, even as Hindu caste identity became more significant under the Mughals, Indian Muslims also seemed to have adopted more formal social categories. Rather than an interruption, therefore, we should understand the Mughal period as a constructive period in which cultures, identities, and traditions emerged, adapted, and changed. This process would continue right up until the rise of British imperialism in India. The British would then interpret the India they observed as the India that had always been. Part of the project of this textbook is to free our sense of the world from the misinterpretations of 19th century imperialists.

Mughal agriculture has been considered incredibly advanced for its time. However, this is in comparison to European agriculture at the same point, which not only shows a Eurocentric viewpoint, but also doesn’t take into location and geography; sheer landmass with the climate that India occupies makes it a key agricultural state without the comparison. The fact that the Mughal empire was able to unite the majority of this landmass and its peasantry labor for both domestic and foreign trade and consumption is what shows advancement, along with the use of the seed drill before Western adoption. In addition, the Mughal empire adopted coins made of both gold and silver, including taking in gold bullion from other outside locations, also showing a strong foreign trade policy. The increase in artistry, showing an amalgamation of Safavid Persian and pre-Mughal Indian technique, also shows a connection between the Mughal empire and its neighbors, even if they weren’t always on the friendliest of terms.

Empires like the Ottoman, Mughal, and Safavid were key drivers of cultural, social, political, and economic change in the early modern world. By connecting millions of people under something like centralized rule, they established much of the foundation upon which the modern world would be built. So in terms of the meaning of “empire,” historians have argued that these three civilizations fall under that definition. However, others have pointed out that the lack of sheer spread of population and geography that also define “empire,” such as the Ancient Roman empire or contemporary Chinese empires, only allow the Ottomans to retain that definition, while the Safavids and Mughals do not. It’s up to you, the student, to determine what may or may not apply to these particular civilizations.

The Mughal Empire and its Successors

The Mughal Empire united the individual states of India between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries under one sovereign power. It was, necessarily given the diverse nature of Indian society, an empire in which cultures and religions blended rather than asserted dominance. As such, the Mughal court became a flourishing center of art and culture, based on a combination of Indian and Perso-Islamic traditions, until its dissolution into civil war in the nineteenth century.

Related Information

UNESCO History of Civilizations of Central Asia, vol V

This platform has been developed and maintained with the support of:

UNESCO Headquarters

7 Place de Fontenoy

75007 Paris, France

Social and Human Sciences Sector

Research, Policy and Foresight Section

Silk Roads Programme

- Increase Font Size

25 Origin and Foundation of Mughal Empire: Babar, Humayun and Sher Shah Interregnum

Mohammad Nazrul Bari

1. Introduction

Between the 13th and 16th centuries, 33 different sultans ruled this divided territory from their seat in Delhi. In 1398, Timur the Lame destroyed Delhi. The city was so completely devastated that according to one witness, “for months, not a bird moved in the city.” Delhi eventually was rebuilt. But it was not until the 16th century that a leader arose who would unify the empire.

In this lesson you will study about the conquest of India by a new ruling dynasty-the Mughals. The Mughal Empire ruled over India from the early 16th century to the 19th century and controlled most of the India and parts of Afghanistan. The Mughals were led by an able military commander and administrator from Central Asia named Zahiruddin Muhammad Babur. His successors were successful in establishing an all India empire gradually. We will study the details of this process of conquests and consolidation in this lesson. Let us begin with the advent of Babur in India.

Babur was born on 14 February 1483 in the town of Andijan in the Fergana Valley in Uzbekistan. He belonged to the Mongol tribe that also embraced Turkish and Persian. Babur is a Arabic word which means tiger, the nickname given to him because of his attitude shown in battles which he fought there before coming to India. His actual and full name was Zahiruddin Muhammad, yet he was commonly known as Babur. It is said that Babur born, extremely strong and physically fit. He was so powerful that he could allegedly carry two men, one on each of his shoulders, and then climb slopes on the run. According to the legend that Babur swam across every major river he encountered.

His father, Omar Sheik, was king of Ferghana, a district of what is now Russian Turkestan. Omar died in 1495, and Babur, though only twelve years of age, succeeded to the throne. An attempt made by his uncles to dislodge him proved unsuccessful, and no sooner was the young sovereign firmly settled than he began to meditate an extension of his own dominions. In 1497 he attacked and gained possession of Samarkand, but in 1501 his most formidable enemy, Shaibani (Sheibani) Khan, ruler of the Uzbegs, defeated him in a great engagement and drove him from Samarkand. For three years he wandered about trying in vain to recover his lost possessions and finally at last, in the year 1504, he gathered some troops, and crossed the snowy Hindu Kush mountain besieged and captured the strong city of Kabul. But due to the political uncertainties in Central Asia, Babur finally took decision to reassemble his army of 12,000 strong, with some pieces of artillery and marched towards India. Ibrahim, with 100,000 soldiers and numerous elephants, advanced against him. The great battle was fought at Panipat on the April 21, 1526, when Ibrahim was slain and his army routed. Babur at once took possession of Agra and established the Mughal dynasty in the year 1526 AD.

Babur the Mughal had many interests. He wrote his memoir Tujuk I Babari in Turkish language. His memoirs reflect that he had an interest in reading, society, hunting, nature, politics and economics. He had wonderful ideas about architecture, administration, and civilization. Babur was a great patron of cultural activities, and welcomed poets, authors and littérateurs at his court. He was adept in Arabic, Turkish and Persian. Although Babur ruled only four years in India, his love of nature led him to create gardens of great beauty which became an intrinsic part of every Mughal fort, palace and state buildings during the centuries that followed. While alive, Emperor Babur laid out the classical Mughal-style gardens located on a high point in west Kabul which comprised a series of beautiful landscaped hillside. He suffered from ill health during the last years of his life and died at the age of 47 on 26 December 1530. He was succeeded by his son, Humayun.

2.1 Achievements:

The achievements of Babur can be stated as follows:

- Babur established the Mughal dynasty in India by defeating Ibrahim Lodi, the last Delhi Sultan, bringing an end to the Delhi Sultanate, in the 1st Battle of Panipat in 1526 AD.

- In 1527 AD, Babur also defeated the Rajput confederacy which was formed by Rana Sangram Singh of Mewar along with a number of other Rajput kingdoms like Marwar, Gwalior, Ajmer, Ambar, etc. under the leadership of Mahmud Lodi, the brother of Ibrahim Lodi, in the Battle of Khanua.

- In 1529 AD, Babur defeated the Afghans i.e. of Bengal, Bihar, Assam, Orissa, etc., who has formed a powerful alliance with Mahmud Lodi, in the Battle of Gogra. It temporarily weakened the anti-Babur strategies and saved the fledgling Mughal reign. Due to the conquests of Babur, the Mughal Empire extended from Kabul in the west to Gogra in the east, from the Himalayas in the north to Gwalior in the south.

2.1.1 The Battle of Panipat (21 April,1526)

Babur marched upon Delhi via Sirhind and reached Panipat village near Delhi Where the fate of India has been thrice decided. He took up a position which was strategically highly advantageous.

Sultan Ibrahim also reached Panipat at the head of a large army. Babur had an army of 12000 men while the forces of Ibrahim were immensely superior in number one lakh according to Babur‟s estimate. The two armies faced each other for eight days but neither side took the offensive. At last Babur‟s patience was tired out and he resolved on prompt action. During the night of the 20th April Babur sent out 4 to 5 thousand of his men to night attack on the Afghan camp which failed in its object but provoked Ibrahim Lodi. He ordered his army to advance for an attack. On approaching close to Babur‟s lines he found the enemy entrenched, showing no sign of movement. He suddenly grew nervous and ordered his army to halt; this created confusion in his ranks. Babur took advantage of the confusion and took up the offensive. The battle was thus joined on April 21st 1526. Ibrahim‟s soldiers fought valiantly but stood no chance of success in the face of Babur‟s artillery and superior war tactics. Within a few hours about 15 to 16 thousand soldiers lay dead along with their leader Ibrahim Lodi.

The first battle of Panipat occupies a place of great importance in the history of medieval India. The military power of the Lodi‟s was completely shattered. It led to the foundation of the Mughal Empire in India. As far as Babur was concerned, Panipat marks the end of the second stage of his project of the conquest of Northern India. Though after his victory he became king of Delhi and Agra yet his real work was to begin after Panipat. He had to encounter a few formidable enemies before he could become king of Hindustan but Panipat gave him a valid claim to its sovereignty.

2.1.2 Causes of Babur’s success

Causes of Babur‟s success in the battle are numerous. Babur was seasoned General whereas Ibrahim was a head strong, inexperienced youth. As Babur remarks he was „an inexperienced man, careless in his movements, who marched without order, halted or retired without method and engaged without foresight. Babur was the master of a highly evolved system of warfare which was the result of a scientific synthesis of the tactics of the several Central Asian people. While Ibrahim fought according to the old system then in existence in the country. Babur had a park of artillery consisting of big guns and small muskets while Ibrahim‟s soldiers were absolutely innocent of its use. Ibrahim did not get the backing of his people which weakened his power. Moreover his army was organized on clannish basis. The troops lacked the qualities of trained and skillful soldiers. Babur was right when he recorded in his diary that the Indian soldiers knew how to die and not how to fight. On the other hand Babur‟s army was well trained and disciplined and shared the ambition of conquering rich Hindustan.

2.2 Post Panipat Problems

The victory at Panipat was quickly followed by Babur‟s occupation of Delhi and Agra. On 27th April 1526 Khutba was read in the name of Babur in Delhi and alms were distributed to the poor and the needy. Offerings were sent to the holy places in Mecca, Medina and Samarqand. But Babur‟s real task began after Panipat. Taking advantage of the confusion that followed Ibrahim‟s death many Afghan chiefs established them independent. Moreover as Babur proceeded towards Agra the people in the country side fled in fear and he could get provisions for his men and fodder for his animals with great difficulty. The soldiers and peasantry ran away in fear. Babur‟s main task was to restore confidence among the people. Some of his own followers began to desert him on account of the hot climate of country. Babur showed his usual patience and strength of character and made it clear to them that he was determined to stay in India. With the result that most of them decided to sink or swim with their leader. The determination of Babur to stay In India was bound to bring him into conflict with the greatest Rajput ruler Rana Sangha of Mewar.

2.2.1 Conflict with the Rajputs – The Battle of Khanwa (March 16, 1527)

The battle of Panipat had no doubt broken the back bone of the Afghan power in India yet a large number of the Turk Afghan nobles were still at large. Bihar had become the centre of their power. But nearer the capital Babur had to face another threat to his newly conquered kingdom. This threat was posed by the Rajputs under their leader Rana Sanga. He had once defeated the forces of Ibrahim Lodi and was desirous of establishing his rule in the country.

On the eve of the battle of Panipat he had sent greetings to Babur but Babur‟s decision to settle down in India dashed his hopes to ground and he began to prepare himself for a contest with the Mughals. Rana Sanga marched to Bayana. He was joined by some Muslim supporters of the Lodi dynasty. But all the Afghan chiefs could not combine under the Rajputs and this made Babur‟s task easy. Rana Sanga was certainly a more formidable enemy than Ibrahim Lodi. Babur as Lane-poole points out “was now to meet warriors of a higher type than any he had encountered. The Rajputs energetic, Chivalrous, fond of battle and bloodshed, animated by strong regional spirit were ready to meet face to face boldest veterans of the camp and were at all times prepared to lay down their lives for their honour. ”Babur advanced to Sikri. The advance guard of Babur was defeated by the Rajputs and Babur‟s small army was struck with terror. But Babur was indomitable and he at once infused fresh courage and enthusiasm into the hearts of his soldiers. He broke his drinking cups, poured out all the liquor that he had with him on the ground and promised to give up wine for the rest of his life. He made a heroic appeal to them to fight together with faith in victory and god. This had its desired effect. All the officers swore by the Holy Quran to stand firm in this contest. The decisive battle was fought at Khanwa, a village near Agra on 16th March, 1527. Once again by the use of similar tactics as at Panipat, Babur won a decisive victory over the Rajputs. Rana escaped but died broken hearted after about two years.

Importance of the Battle of Khanwa

This battle supplemented Babur‟s work at Panipat and it was certainly more decisive in its results. The defeat of the Rajputs deprived them of the opportunity to regain political ascendancy in the country forever and facilitated Babur‟s task in India and made possible the foundation of the Mughal Rule. Rushbrook William is right when he says that before the battle of Khanwa “the occupation of Hindustan might have looked upon as mere episode in Babur‟s career of adventure; but from henceforth it becomes the keynote of his activities for the remainder of his life. His days of wandering in search of fortune are now passed away; the fortune is his and he has but to show himself worthy of it. And it is also significant of Babur‟s grasp of vital issues that from henceforth the centre of gravity of his power is shifted from Kabul to Hindustan,” Thus within a year Babur had struck two decisive blows which shattered the powers of two great organised forces. The battle of Panipat had utterly ruined the Afghan power in India, the battle of Khanwa crushed the Rajputs. Medini Rai the Rajput chief of Chanderi and a close associate of Rana Sanga had escaped from Khanwa. He took shelter in the fort of Chanderi with a contingent of about 5 thousand Rajputs. Babur besieged the fort and conquered it in January 1528.

2.2.2 The Battle of Ghaghra, May 1529

We have already noted that Babur had hurried to meet the Rajputs and thus had left the task of thorough subjugation of the Afghans incomplete. Now he was free to settle his scores with them, the Afghans of Bihar were led by Mahmud Lodi, the younger brother of Sultan Ibrahim Lodi, Babur met the Afghans in the battle of Ghagra (near Patna) in May 1529 and it was an easy victory. Thus in these battles Babur had reduced Northern India to submission and became the ruler of a territory extending from Oxus to the Ghagra and from Himalayas to Gwalior. But he was not destined to enjoy his hard won empire for long. The strain of continuous warfare, administrative liabilities and excessive drinking till the battle of Khanwa had bad effect on his health. He passed away on 26th December, 1530 at the age of 47. His body was taken to Kabul and buried in one of his favorite gardens.

2.3 Contribution:

Art‟s and Architecture: Mughal Architecture influenced greatly in Babur‟s rule. Mughal architecture under Babur was a beginning of an imperial movement, impressed by local influences. Babur‟s elegant and stylish buildings evolved gradually because of the gifted artists in those provinces. Babur constructed many mosques around India. Three of the famous mosques are the Babri Mosque, the Panipat Mosque and the Jama Masjid.

Babri Mosque :

The Babri mosque was built in Ayodhya,a city in Faizabad. It was constructed in 1527 by the Governor of Babur, Mir Baqi. Babri Masjid was a large imposing structure with three domes, one central and two secondary. It is surrounded by two high walls, running parallel to each other and enclosing a large central courtyard with a deep well, which was known for its cold and sweet water. On the high entrance of the domed structure are fixed two stone tablets which bear two inscriptions in Persian declaring that this structure was built by one Mir Baqi on the orders of Babur. The walls of the Babri Mosque are made of coarse-grained whitish sandstone blocks, rectangular in shape, while the domes are made of thin and small burnt bricks. Both these structural ingredients are plastered with thick lime stone paste mixed with coarse.

Bagh-e-Babur:

The Gardens of Babur locally called Bagh- e-Babur is a historic park in Kabul, Afghanistan, and also the last resting-place of the first Mughal emperor Babur. The gardens are thought to have been developed around 1528. The site of Bagh e Babur is thought to be that of the “paradise.” It is one of several gardens that Babur had laid out for recreation and pleasure during his life, while choosing this site as his last resting place.

Panipat Mosque:

The mosque that Babur himself provided is located in Panipat, presently laced in Karnal District of Haryana State. The mosque has a rectangular prayer chamber which is dominated by a large central dome. The northwest and the southwest corners of the mosque were marked by octagonal towers crowned by domed pavilions, although only one survives. It was completed in 1528 by Babur.

3. Humayun’s Early Life and Accession:

Nasiruddin Muhammad Humayun was the eldest son of Babur and he had three brothers – Kamran, Askari and Hindal. Humayun was born in Kabul in 1508. His father made best arrangements for his education and training in state-craft. He learnt Turkish, Arabic and Persian. As a boy he was associated by his father with civil and military administration. At the age of 20 he was appointed the governor of Badakhshan. Humayun took part in his father‟s campaigns and battles; both in the battle of Panipat and Khanwa he was among the chief commanders of the invading army. After the battle of Khanwa he was sent back to take charge of Badakhshan but he returned to India in 1529 without the permission of his father. Before his death in December 1530 Babur nominated Humayun as his successor. Humayun thus ascended the throne at Agra on December 30, 1530 four days after the death of Babur.

3.1 Challenges before Humayun

The throne inherited by Humayun was not a bed of roses. Along with the empire he inherited many difficulties which were further complicated as he was not a very gifted general nor he was an excellent statesman.

After the death of Babur, a war of succession started. Every prince asserted as independent after getting governorship of various provinces. The three brothers of Humayun also desired the throne. Babur had not left behind him a well organized and consolidated empire. During his four years in India he had been busy in conquests only. He had neither time nor inclination to establish a new system of administration. The Mughal army also was not a national one. It was a mixed body of adventures, viz Moguls, Persians, Afghans, Indians, Turks and Uzbeks. Such an army was not dependable. Humayun‟s court also was full of nobles who had plans for the possession of the throne. More dangerous than the nobles were the princes of the royal blood. His three brothers coveted the throne and added to the difficulties of Humayun. Besides them Humayun‟s cousin brothers Muhammed Zaman Mirza and Muhamad Sultan Mirza also considered their claim to the throne as good as those of the sons of Babur.

The newly founded Mughal state in India was threatened by numerous external enemies. The Afghans had been defeated in the battle of Panipat and in the battle of Ghagra but they were not completely crushed. They refused to submit to the Mughal domination and they proclaimed Mahmud Khan Lodi, brother of Ibrahim Lodi as their king. Sher Khan Sur (later known as Sher Shah Suri) was the most ambitious of the whole Afghan party. He had already entered upon a military career and was making an effort to organize the Afghan. He was soon to drive Humayun into exile and occupy the throne. The Mughal authority was also threatened by the growing power of Gujarat under Bahadur Shah. He was a young and ambitious prince of an extremely rich kingdom. As he had plenty of resources at his command, he aimed at completely taking control of India.

Thus, when Humayun ascended the throne he was faced with a number of internal and external enemies. The need of the hour was a ruler possessed of military genius, political wisdom and diplomatic skill. Unfortunately Humayun lacked all these qualities. He lacked foresight and determination. He could not take quick decisions. He failed to command full control confidence of his subjects and soldiers.

3.2 Wars of Humayun (1530-1540)

From the beginning of his reign Humayun committed a series of mistakes one after another which ultimate cost him his throne and forced him into exile in 1540. Soon after his accession to the throne he divided his empire among his brothers. Kamran was given the governorship of Kabul and Kandahar and in addition was permitted to take the possession of the Punjab and North Western frontier of India. This was a mistake on his part because this created a barrier between him and the lands beyond the Afghan hills and he could not draw troops from central Asia. Askari was given Sambhal while Hindal was given Alwar. He also increased the jagir of every one of his armies. Babur had set a bad precedent by allocating vast tracts of land to his nobles as personal estates in return for the services rendered by them to the throne. Humayun failed to appreciate the fatal consequences of the policy of large scale distribution of territory among military officials. This later on caused him endless worry. Humayun instead of consolidating his position started with a policy of aggressive warfare.

Expedition to Kalinjar (1531)

Within six months of his accession Humayun undertook an expedition against Kalinjar in Bundelkhand, whose raja was suspected to be in sympathy with the Afghans. After a siege of about six months the raja submitted. Humayun made peace with him and accepted huge indemnity from him. The expedition exposed the weakness of the Mughal army as the raja could not be defeated.

First siege of Chunar (1532)

Meanwhile the Afghans of Bihar under Mahmud Lodi were marching on the Mughal province of Jaunpur. Humayun met the Afghan forces and defeated them in the battle of Daurah (or Dadrah) in August 1532. Then he besieged the fort of Chunar which was held by the Afghan chief Sher Khan. The siege lasted for four months and like Kalinjar this fort also could not be conquered by the Mughal army. Humayun abandoned the siege and accepted submission of Sher Khan. He lost a splendid opportunity of crushing the Afghan power for which he had to pay heavily later on.

Battles with Bahadur Shah of Gujarat (1535-1536)

By now Bahadur Shah of Gujarat had consolidated his position. He had already conquered Malwa (1531) and Raisen (1532) and had defeated the Sisodia chief of Chittor (1533). He had openly given shelter and help to many afghan refugees and enemies of Humayun. Humayun therefore decided to proceed against Bahadur Shah (end of 1534) who was at that time conducting a siege of Chittor.

He waited till Chittor fell to Bahadur Shah (March, 1535).After its fall Humayun started his operations against Bahadur shah who was besieged in his camp. His supplies ran short and he was faced with starvation. He fled and took shelter in, the fort of Mandu, Humayun besieged fort of Mandu and captured it in April, 1535. Humayun chased him from Mandu to Champaner and Ahmedabad and then to Combay till he was compelled to seek refuge in the Island of Diu (August 1535). The capture of Mandu and Champaner were great achievements on the part of Humayun. He appointed Askari as the governor of the newly conquered territories. Askari failed to restore law and order. He was too weak to retain Gujarat and internal dissensions broke out among the Mughals which enabled Bahadur Shah to recover his position. The local Gujarati Chiefs who were dis-satisfied with Mughal rule helped Bahadur shah. The result was that Gujarat was completely lost in 1536. Humayun found that it was impossible to retain Malwa as well so he left Mandu in May 1536. Thus the entire province of Malwa was also lost “One year had seen the rapid conquest of the two great provinces; the next saw them quickly lost,” Humayun therefore failed to establish his authority in the west. Now he turned his attention to meet the organized strength of the Afghans under Sher Khan.

Contest with Sher Khan (1537-1540)

While Humayun was busy with Bahadur shah of Gujarat, Sher Khan had strengthened his position in Bihar and Bengal. He had already made himself the master of Bihar and had twice defeated the King of Bengal in 1534 and 1537. The repeated successes of the Afghan hero convinced Humayun who had been then spending his days at Agra without any activity after his return from Mandu in August 1536, of the Afghan danger in the east. He therefore decided to march against Sher Khan in 1537. He besieged the fort of Chunar for the second time in October 1537. A strong garrison left by Sher Khan at Chunar heroically defended the fort for six months though it was ultimately captured by Humayun in March, 1538. During this period Sher Khan was busy in reducing Gaur (Bengal). Sher Khan also captured the fortress of Rohtas (Bihar) and sent his family and wealth there. Humayun now turned his attention towards Bengal. For some time he was undecided for the move. Ultimately he made up his mind to conquer Bengal. The road to Gaur was locked by Jalal Khan, son of Sher Khan. There was fighting and Jalal Khan retired. Sher khan during this period tried to compensate his loss of Bengal by occupying the Mughal possessions in Bihar, Jaunpur and plundering the country as far west as Kannauj and cut off the communication between Agra and Bengal. When Humayun realized the dangerous position in which he was placed he decided to return to Agra immediately. Sher khan blocked the road to Agra and only a decisive victory could help Humayun to reach Agra.

Battle of Chausa (June 26,1539)

When Sher Shah heard of Humayun‟s retreat he collected his troops at Rohtas and decided to give him battle. Humayun was advised by his generals to move along the northern bank of river Ganges up to Jaunpur and then cross over to the other side and then contact Sher Khan but Humayun‟s pride came in the way and he transferred his entire army to the southern bank of Ganges in order to put pressure on Sher Khan, and to make use of a better route, the old grand trunk road to Agra. The road passed through a low lying area which used to be flooded during the rainy season. Humayun learnt about Sher Khan‟s approach when he was near Chausa. The two armies face each other for about three months and none of them started the fighting. The rainy season was approaching. When the rains started the Mughal camp was flooded. Sher Khan was waiting for the opportunity to strike. On 26th June, 1539 the battle of Chausa was fought. Thousands of Mughal soldiers died and many of them drowned in the flood waters of the Ganges. Humayun himself had narrow escape. His life was saved by a water carrier (Nizam) who offered him his mashak (the inflated skin) for swimming across the river. It is said that on reaching Agra Humayun rewarded the water carrier with the grant of kingship for half a day and permitted him to sit on the throne and distributed rich presents to his friends and relatives according to his desire.

The Battle of Kanauj (17 May,1540)

By the victory at Chausa, Sher Khan‟s ambition was immensely widened. The Afghan nobles pressed Sher Khan to assume full sovereignty. He assumed the title of Sher Shah and prepared to march upon Delhi and Agra. The battle of Chausa convinced Humayun of Sher Khan‟s formidable power. Humayun on reaching Agra in spite of his best efforts failed to secure the co-operation of his brothers. Somehow Humayun managed to raise an army to fight against Sher Khan. He could not delay his march much longer because Sher Khan was steadily advancing towards the capital. Humayun had to move towards Kanauj with his army in order to check the advance of his adversary. He set up his military camp at Bhojpur near Kanauj in April 1540 while Sher Shah brought his forces to halt on the southern bank of the Ganges. Humayun again committed the mistake of ordering his army to cross over to the southern bank of the river without taking into consideration the approaching monsoon. The two forces faced each other for over a month. During this period Humayun‟s army swelled up to about two lakhs although most of his men were poorly equipped and were not trained. On May 15, 1540 there was a very heavy shower of rain and the Mughal camp was flooded. As the Mughals were preparing to shift to a higher place Sher Shah ordered his troops to launch the attack. Thus on 17 May,1540 the battle of Kannauj was fought. The Mughal army was severely defeated by the Afghans. Most of the Mughal soldiers fled for their lives without fighting while a large number of them drowned in the Ganges. Sher Shah‟s victory was complete.

Exile in Persia

Narrowly escaping his brother’s forces, Humayun reached Persia, where Shah Tahmasp offered him a hearty reception. Humayun had brought about his own downfall. First, he should never have divided his kingdom among his treacherous brothers. Second, he seems to have believed, until as late as the early months of 1539, that Sher Shah was a mere upstart and could easily be stopped. Third, on reaching Gaur, Humayun had wasted more than eight months during which Sher Shah occupied the country from Teliagarhi to Kanauj. Humayun had shown little determination in bringing down his greatest rival.

Eventually, Humayun would conquer his brothers. When Kamran was later arrested, Humayun had him blinded and exiled to Mecca. Kamran would die in Arabia in 1557. Humayun’s other brother Askari would also be sent to Mecca, while an Afghan would kill Hindal. Thus, Humayun would finally be free of his dangerous rivals, who had been an important link in his expulsion from India.

During his exile in Persia, Humayun’s great rival Sher Shah, who had established a vast and powerful empire supported by a wise system of administration, died in 1545. But Sher Shah’s son, Islam Shah could not keep his Afghan nobles in check. When Islam Shah died in 1553, the Afghan Empire was well on its way to decay. Aware of this disintegration, Humayun was eager to return to India with newly recruited armies. Finally Shah Tahmasp of Persia offered him a force of 14,000 men to regain his lost territory. When Humayun crossed the Indus River, Bairam Khan, the most efficient and faithful of his officers, joined him. Many commanders from Qandahar came to help. While all around there was frequent strife, its governor maintained Qandahar as the undisputed base of Mughal operations. Thus with Persian help and Bairam Khan’s support, Humayun was in a position to capture lost provinces. In February of 1554, he occupied the Punjab, including Lahore, without any serious opposition. At the news of the Mughal success, the Afghan leader Sikandar Shah sent detachments against the Mughals, but at every encounter the Afghans were beaten. According to Mughal historians, Sikander’s armies were larger than the Mughals, but the superior Mughal tactics gave Bairam Khan a resounding victory on June 22, 1555. That same year, after an interval of 15 years, Humayun reconquered the Punjab, Delhi, and Agra, and reoccupied the throne of Delhi. He now appointed Akbar, his young son and heir apparent, governor of Punjab and assigned Akbar’s private tutor, Bairam Khan, to assist him. This step was necessary in order to put down Sikandar Sur whose army had swelled and who was carrying on expeditions in the Punjab.

3.3 Restoration of Mughal Power

Humayun’s second reign lasted only seven months. Still surrounded by Afghan enemies, the supporters of the Sur dynasty, he had recovered only part of his dominion. The most difficult task was that of establishing a firm system of administration and winning the sympathy of the people. There was now one advantage. With his brothers dead or banished, there was nowhere for the loyalty of his followers to swerve. He rewarded his friends and supporters. Bairam Khan was then created Khan-Khanan, the lord of lords.

During this time, Humayun selected sites for several observatories. With poetry almost the lingua franca of court life, discussions took place in the building called the Sher Mandal that was turned into a library. Here his valuable manuscripts were kept in safe custody; here Mir Sayyid Ali taught drawing to Akbar. In fact, both Humayun and Akbar took lessons in drawing. It was under two Persians, Khwaja Abdus Samad and Mir Sayyid Ali, that Indian artists undertook the Dastan-i-Amir-Hamzah, the first great series of paintings in what is now known as the Mughal School of art.

During Humayun’s five-year absence, Sher Shah had greatly improved the system of provincial government and revenue collection. Humayun wanted to recreate the system, maintaining Sher Shah’s village and district administration, while dividing the domain into provinces, each with its own capital. But, on January 24, 1556, in pious response to the sacred call of the muazzin for evening prayer, Humayun, while hurriedly descending from his library in Delhi, stumbled down the stairs. Two days later, in the words of historian Lane-Poole, he “tumbled out of life as he had tumbled through it.” Since Humayun had not had time to introduce reforms, it was now left to his 13-year-old son Akbar to fulfil his intentions, building an enduring administrative edifice on Babur, Sher Shah, and Humayun’s foundations.

Among the first six Great Mughals, the image of Humayun is that of the nonentity, the one obvious failure. He was impetuous as well as indecisive. With all his weaknesses and failings, Humayun deserves a significant place in Indian history. The restoration of Mughal power paved the way for the splendid imperialism of Akbar. The Indo-Persian contact, which Humayan stimulated and reinforced, was of far-reaching consequence in the history of Indian civilization. Humayun also added to the development of Mughal architecture. Aesthetically inclined, he undertook in the early years of his reign, the building of a new “asylum of the wise and intelligent persons.” It was to consist of a magnificent palace of seven stories, surrounded by delightful gardens and orchards of such elegance and beauty that its fame might draw the people from the remotest parts of the world.

4. Sher Shah Suri

Sher Shah Suri, whose original name was Farid was the founder of the Suri dynasty. Son of a petty jagirdar, neglected by his father and ill treated by his step-mother, he very successfully challenged the authority of Mughal emperor Humayun, drove him out of India and occupied the throne of Delhi. All this clearly demonstrates his extra-ordinary qualities of his hand, head and heart. Once again Sher Shah established the Afghan Empire which had been taken over by Babur.

4.1 Sher Shah’s early career:

The intrigues of his mother compelled the young Farid Khan to leave Sasaram (Bihar), the jagir of his father. He went to Jaunpur for studies. In his studies, he so distinguished himself that the subedar of Jaunpur was greatly impressed. He helped him to become the administrator of his father‟s jagir which prospered by his efforts. His step-mother‟s jealousy forced him to search for another employment and he took service under Bahar Khan, the ruler of South Bihar, who gave him the title of Sher Khan for his bravery in killing a tiger single-handed.

But the intrigues of his enemies compelled him to leave Bihar and join the camp of Babur in 1527. He rendered valuable help to Babur in the campaign against the Afghans in Bihar. In due course, Babur became suspicious of Sher Khan who soon slipped away. As his former master Bahar Khan, the ruler of South Bihar had died, he was made the guardian and regent of the minor son of the deceased. Slowly he started grabbing all the powers of the kingdom. Meanwhile the ruler of Chunar died and Sher Shah married his widow. This brought him the fort of Chunar and enormous wealth.

4.2 Military achievements of Sher Shah:

Military achievements of Sher Shah may be categorized under three heads namely:

(i) Encounters with Humayun

(ii) Other encounters

(iii) Conquests after becoming emperor of Delhi.

1. Sher Shah’s encounters with Humayun: Following were the three encounters:

(i) Encounter on the fort of Chunar and Sher Shah‟s diplomatic surrender.

(ii) Battle of Chausa with Humayun and Sher Shah‟s victory.

(iii) Batttle of Kanauj and Sher Shah‟s decisive victory over Humayun. With the victory at Kanauj, Sher Shah became the ruler of Delhi. Agra, Sambhal and Gwalior etc., also came under his sway. This victory ended the rule of the Mughal dynasty for 15 years.

2. Sher Shah’s other conquests:

(1) Battle at Surajgarh (1533):

Sher Shah defeated the combined forces of the Lohani chiefs of Bihar and Mohamud Shah of Bengal at Surajgarh. With this victory, whole of Bihar came under Sher Shah. Dr. Qanungo has described the importance of this victory in these words, “If Sher Shah had not been victorious at Surajgarh, he would have never figured in the political sphere of India and would not have got an opportunity to compete with Humayun… for the founding of an empire.”

(2) Invasion of Bengal:

Sher Shah plundered Bengal several times and by capturing Gaur, the capital of Bengal, forced Mohammad Shah to seek refugee with Humayun.

3. Sher Shah’s conquests after becoming the emperor of Delhi:

(i) Conquest of Punjab (1540-42):

Sher Shah immediately, after his accession to the throne conquered Punjab from Kamran, brother of Humayun.

(ii) Suppression of Khokhars (1542):

Sher Shah suppressed the turbulent Khokhars of the northern region of river Indus and Jhelum.

(iii) Conquest of Malwa (1542):

The ruler of Malwa had not helped Sher Shah in his struggle with Humayun. Therefore he attacked Malwa and annexed it to his empire.

(iv) Conquest of Raisin:

Sher Shah attacked Raisin – a Rajput principality and besieges it. Rajput ruler Purnamal entered into an agreement with Sher Shah that if he surrendered, his family would not be harmed. However Sher Shah did not honour this agreement. In the words of Dr. Ishwari Prasad, “Sher Shah behaved with him very cruely.”

(v) and (vi) conquest of Multan and Sind (1543) :

Sher Shah conquered and annexed these provinces into his empire.

(vii) Conquest of Marwar (1543-1545):

Sher Shah brought Marwar under his control by forged letters and sowing dissensions in the army of Maldev, the ruler of Mewar.

(viii) Conquest of Kalinjar (1545) and death of Sher Shah. Sher Shah launched a fierce

attack. He won but lost his life when he was grievously injured by the blast.

4.3 Sher Shah Suri’s key achievements:

Introduction of an Effective Monetary System

Sher Shah introduced the tri-metal coinage system which later came to characterize the Mughal coinage system. He also minted a coin of silver which was termed the Rupiya that weighed 178 grains and was the precursor of the modern rupee. The same name is still used for the national currency in Pakistan, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Mauritius, Maldives, and Seychelles among other countries.

Development of Roadways

For military and trade movement, Sher Shah connected the important places of his kingdom by a network of excellent roads. The longest of these, called the Sadak-e-Azam or the “Badshahi Sadak” (renamed “Grand Trunk Road” by the British) survives till this day. This road is the longest highway of Asia and extends over 1500 Km from Sonargaon in Eastern Bengal to the Indus. All the roads were flanked by shade giving trees and there were sarayes (traveler‟s inns) all along the routes.

Administrative Subdivision of Empire

The Sur empire was divided into forty-seven separate units called sarkars( districts). Each sarkar was divided into small units called the parganas and each pargana was further subdivided into a number of villages. Like the s arkars, there were two chief officers called a s hiqdar (military officer) and Munsif (civilian judge) who were assisted by other staff in the discharge-of their duties. Each pargana had its own administrative system with its own Amil, law keeper, treasurer and account keepers. Over the next higher administrative unit, the sarkar , were placed a Shiqdar-I-Shiqdaran and a Munsif-I-Munsifan to supervise the work of the pargana officers. To keep a tab on the performance of his officers, Sher shah had planned to rotate them across the empire every two or three years. Every branch of the administration was subject to Sher Shah’s personal supervision.

Development of the First Postal System

The sarayes developed along the road network also served as post offices. Sher Shah Suri established the foundations of a mounted post or horse courier system, wherein conveyance of letters was also extended to traders. This is the first known record of the Postal system of a kingdom being used for non-State purposes, i.e. for trade and business communication.

Administration of Justice:-

Sher Shah was adorned with Jewel of justice and he often times remarks,” Justice is the most excellent of religious right and it is approved both by the king of the infidels and the faithful”. He did not spare even his near relatives if they resorted to any criminal deed. Like other medieval rulers Sher Shah sometimes decided cases in person. Village panchayat was empowered to administer justice in the villages, in the parganas were the munsifs and in the sarkars were the chief munsifs. They administered civil and Revenue cases while the shiqdar and his chief in the sarkar dealt with the criminal cases. In addition there were courts of the Qezi and the mir-adl culminating in the highest courts of the chief Qazi. All higher officers and courts had full authority to hear appeals against the decisions arrived at by their junior counterparts. Above all was situated the king‟s court. The criminal law of the time was very hard and punishments were severe. The object of punishment was not to reform but to set an example so that the others may not do the same.

Land Revenue System of Sher Shah :

Before Sher Shah, the land rent was realized from the peasants on the basis of estimated produce from the land but this system did not seem to be faultless as the produce was not constantly the same. It increased or decreased year after year. Sher Shah introduced a number of reforms in the fields of revenue. These are as follows.

- Sher Shah was the first Muslim ruler who got the whole of the land measured and fixed the land-tax on it on just and fair principles.

- The land of each peasant was measured first in “bighas” and then half of it was fixed as the land tax. According to More land in certain portions of the empire such as Multan the land tax was however one-fourth of the total produce.

- The settlement made between the Govt. and the peasant in respect of the land revenue was always put in black and white. Every peasant was given as written document in which the share of the Govt. was clearly mentioned so that no unscrupulous officer might cheat the innocent peasant. This is known as „Patta‟.

- Each and every peasant was given the option to pay the land-tax either in cash or in kind. The subjects of Sher Shah used to Kabul (Promise) that they should pay taxes in lieu of Patta.

- The peasants were required to credit the land-tax direct into the Govt. treasury, to be on the safe side, so that the collecting officers might not charge them any extra money.

- Strict orders had been issued to the revenue authorities that leniency might be shown while fixing the land tax, but strictness in the collection thereof should be the inevitable rule.

- But suitable subsidy was granted to the farmers in the time of drought, famine or floods from the royal treasury.

- Special orders were issued to soldiers that they should not damage the standing crops in any way. According to Abbas Khan, the cars of those soldiers, who disregarded these orders, were cut off. Even when Sher Shah led an expedition to the territory of his enemy, he was very particular about it that no harm shall come to the farmers in any way from the excesses of his soldiers.

- In case of damages compensation was granted to the former by the Govt. This arrangement of Sher Shah was as reasonable as was adopted not by Akbar only but was followed by the British Govt. also. The well-known „Ryatwari System‟ which has been in vague till now, was not founded by Akbar but by Sher Shah.

Other Major Works

- He also built several monuments including Rohtas Fort, Sher Shah Suri Masjid in Patna, and Qila-i-Kuhna mosque at Purana Qila, Delhi

Sher Shah remained a brave and ambitious warrior till the very end. He was succeeded by his son, Jalal Khan who took the title of Islam Shah Suri. His successors, however, proved to be weak rulers and the Mughals were able to re-establish their rule in India after a few years. Sher Shah Suri died from a gunpowder explosion during the siege of Kalinjar fort on May 22, 1545 fighting against the Chandel Rajputs. Had it not been for his untimely demise the Sur dynasty would not have declined and perished and the Mughal Empire may never have been re-established. After the death, the tomb was built in the memory of Emperor Sher Shah, which was planned by Sher Shah only. The Sher Shah Suri Tomb (122 ft high) stands in the middle of an artificial lake at Sasaram, a town that stands on the Grand Trunk Road, his lasting legacy. This tomb is known as the second Taj Mahal of India.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mughal_emperors

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sur_Empire

- http://www.britannica.com/topic/Mughal-dynasty

- http://asianhistory.about.com/od/india/p/mughalempireprof.htm

- http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?ParagraphID=hkj

- http://www.paradoxplace.com/Insights/Civilizations/Mughals/Mughals.htm

- http://www.britannica.com/topic/Sur-dynasty

- http://www.thefridaytimes.com/tft/the-persian-connection/

- http://www.culturalindia.net/indian-history/akbar.htm

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

The Productive Teacher

The Mughal Empire for AP World History

October 27, 2023 1 Comment

Want to get back to the overview of the 1450 – 1750 CE section?

1450 – 1750 CE OVERVIEW

Ap world history homepage.

The Mughal Empire was an Islamic empire in India from 1526 to 1707. During its best times, the empire was a model for peaceful coexistence between Muslims and Hindus. Click to read all about the Mughal Empire in the Google Slides.

The Founding of the Mughal Empire by Babur

Babur was born in 1483 into the Timurid dynasty, founded by his great-great grandfather, Timur. The kingdom was both Turkish and Mongol. When he was young, he inherited the throne of Fergana, one of the regions of the Timurid dynasty.

In 1526, Babur set his sights on India. At that time, India was divided into various kingdoms, and the ruling Sultan, Ibrahim Lodhi, from the Dehli Sultanate, was unpopular. Babur saw an opportunity to expand his empire and set out on an audacious expedition. His army, which included skilled warriors and war elephants, faced off against Sultan Ibrahim Lodhi’s forces at the First Battle of Panipat.

The battle was fierce, but Babur’s tactics and artillery gave him the upper hand. He emerged victorious, and this battle is considered the starting point of the Mughal Empire. Babur went on to capture Delhi, establishing himself as the ruler.

Timur and India

Timur (also known as Tamerlane) was Babur’s great-great grandfather. He invaded India over one hundred years before Babur. In 1398, he launched a military campaign into the Indian subcontinent. His campaign culminated in the famous sack of Delhi in 1398, during the rule of the Delhi Sultanate.

Tamerlane’s invasion was brutal, resulting in widespread destruction and significant loss of life. He captured and looted Delhi, leaving the city in ruins. This invasion marked a tragic episode in the history of the Indian subcontinent.

It’s important to note that while Tamerlane did invade India, his campaign was relatively short-lived, and he did not establish a long-lasting empire in the subcontinent. The Indian subcontinent would see later incursions and the establishment of the Mughal Empire by his descendant Babur in 1526.

Akbar and Religion in the Mughal Empire

Akbar the Great, the third ruler of the Mughal Empire, reigned from 1556 to 1605 and is remembered as one of the most remarkable and visionary emperors in Indian history. Under his rule, the Mughal Kingdom reached its zenith.

Akbar was known for his policy of religious tolerance, which was groundbreaking in an era marked by religious divisions. Unlike other Muslim rulers, he allowed non-Muslims to worship freely. He also ended the jizya. The jizya was a tax on non-Muslims.

To guide the nation, Akbar conferred with both Hindu and Muslim scholars. He also married Muslim, Hindu, and Christian women.

Many scholars believe Akbar’s greatest achievement was his success blending India’s Hindu and Muslim cultures.

Akbar and Art in the Mughal Empire

Akbar the Great played a pivotal role in shaping the art and cultural landscape of the empire. Akbar had a deep appreciation for the arts and was a patron of artists, scholars, and craftsmen. Under his rule, the Mughal Empire experienced a flourishing of art and culture, often referred to as the “Akbari Age.” He actively promoted a fusion of Persian, Indian, and Central Asian artistic traditions, leading to the development of the distinctive Mughal style. Akbar’s court became a hub for poets, painters, musicians, and scholars, fostering an environment of creativity and innovation. The Mughal miniatures of this period, marked by intricate detailing and vibrant colors, thrived, depicting various facets of Mughal life, nature, and religious themes. Akbar’s legacy in the world of art is a testament to his vision of cultural pluralism and his contribution to the enduring artistic heritage of the Mughal Empire.

Mughal miniatures, also known as Mughal paintings, were a distinctive form of art created in the Mughal Empire of South Asia. These paintings are characterized by their intricate details, vibrant colors, and a focus on depicting scenes from the Mughal court, nature, mythology, and daily life.

Intricate Detail: Mughal miniatures are known for their meticulous attention to detail. Artists used fine brushes and pigments to create intricate patterns, textures, and designs in their paintings.

Vibrant Colors: These paintings are often filled with vibrant colors, including rich reds, blues, and greens, which were made from natural pigments and dyes.

Persian Influence: Mughal miniatures were influenced by Persian art, which is evident in their use of Persian artistic techniques, themes, and motifs.

Mughal Court: Many miniatures depicted scenes from the Mughal court, including portraits of emperors, their families, and nobility, as well as courtly events and ceremonies.

Nature and Landscape: Artists often painted natural landscapes, animals, and plants. The depiction of gardens, rivers, and lush scenery was common in Mughal miniatures.

Religious and Mythological Themes: These paintings also portrayed religious and mythological themes, with subjects like Hindu epics and Islamic stories.

Calligraphy: Mughal miniatures often included calligraphy in the form of poetry, inscriptions, or captions that provided context for the scenes depicted.

Akbar and Architecture in the Mughal Empire

Akbar left an indelible mark on the architecture of the Mughal Empire. Akbar was known for his patronage of art and his keen interest in architectural innovation. He encouraged a synthesis of Persian, Indian, and Central Asian architectural styles, resulting in the distinctive Mughal architectural tradition. One of his most notable architectural achievements is the construction of Fatehpur Sikri, a magnificent palace city that blended elements of Mughal, Persian, and Indian architecture. Akbar also promoted the use of red sandstone in his buildings, which gave them a unique and enduring character. His architectural legacy extended to the construction of impressive forts, ornate palaces, and beautiful gardens. Akbar’s profound influence on Mughal architecture not only reflected his grandeur but also contributed to the creation of architectural masterpieces that continue to enchant and inspire generations to this day.

Akbar and Literature in the Mughal Empire

Akbar the Great was not only a visionary leader in the realm of politics and administration but also made significant contributions to literature and culture. Akbar was a patron of poets, scholars, and intellectuals, and he actively encouraged the production of literary works in various languages, including Persian and the emerging language of Urdu. His court, known as the “Akbari Age,” became a vibrant center of literature and learning. He established a rich tradition of storytelling, which included the translation of Sanskrit texts into Persian, giving rise to a fusion of cultural and intellectual influences. Akbar’s efforts to promote religious tolerance and syncretism were reflected in the literary works of his time. His own biography, the “Akbarnama,” written by his court historian Abul Fazl, is a testament to his support for intellectual endeavors. Akbar’s reign left an indelible mark on the cultural and literary landscape of the Mughal Empire, fostering a legacy of pluralism and creativity that endures to this day.

Urdu is a language that created during Akbar’s reign in the Mughal Empire. It is a fusion of Persian, Arabic, and local Indian languages. Akbar the Great, one of the prominent Mughal emperors, played a significant role in the development and promotion of the Urdu language. He was instrumental in the creation of the “Din-e Ilahi,” a syncretic religious and philosophical system, where Persian and Sanskrit words were blended to create the Urdu vocabulary.

Akbar as a Ruler

Akbar the Great, who ruled the Mughal Empire from 1556 to 1605, is celebrated for his visionary and inclusive approach to governance. His reign was marked by a commitment to religious tolerance and a diverse administration. Akbar appointed officers from various religious and ethnic backgrounds to his bureaucracy, ensuring that different perspectives were represented. He initiated religious debates and discussions, creating an atmosphere of intellectual exchange where scholars from different faiths could share their beliefs and ideas freely. In a groundbreaking move, Akbar abolished the jizya, a tax imposed on non-Muslims, demonstrating his commitment to religious equality. He also introduced a graduated income tax system, which taxed individuals based on their income, thereby promoting economic equity. Akbar’s rule is a shining example of an inclusive and progressive approach to governance, where diversity, intellectual exchange, and social justice were central principles of his reign. His legacy as a just and forward-thinking ruler endures in the annals of history.

Rajput Officers

Akbar the Great recognized the value of incorporating Rajput officers into his administration and military. His reign from 1556 to 1605 was marked by a policy of religious tolerance and a commitment to cultural integration. To promote harmonious relations with the Rajput rulers of North India, Akbar married several Rajput princesses, thereby creating marital alliances and trust.