Abstract Generator

Get your abstract written – skip the headache., writefull's abstract generator gives you an abstract based on your paper's content., paste in the body of your text and click 'generate abstract' . here's an example from hindawi., frequently asked questions about the abstract generator.

Is your question not here? Contact us at [email protected]

What are the Abstract Generator's key features?

| ✂️ Copy & paste | Copy the body of your paper to generate an abstract fast. |

| 🙌 Free to use | No payment required, completely free! |

| 🔒 Safe & secure | Your data is fully encrypted and never stored. |

| 👨💻 API access | API access to the Abstract Generator on request. |

Title is Here

Your abstract is here

- Abstract Generator

Abstract generator lets you create an abstract for the research paper by using advanced AI technology.

This online abstract maker generates a title and precise overview of the given content with one click.

It generates an accurate article abstract by combining the most relevant and important phrases from the content of the article.

How to write an abstract for a research paper?

Here’s how you can generate the abstract of your content in the below easy steps:

- Type or copy-paste your text into the given input field.

- Alternatively, upload a file from the local storage of your system.

- Verify the reCAPTCHA.

- Click on the Generate button.

- Copy the results and paste them wherever you want in real-time.

Features of Our Online Abstract Generator

Free for all.

Our abstract generator APA is completely free for everyone. You don’t have to purchase any subscription to abstract research papers and articles.

Files Uploading

To get rid of typing or pasting long text into the input box, you can use this feature.

This will allow you to upload TXT, DOC, and PDF files from the local storage without any hurdles.

Create Abstract and Title

This abstract creator online makes it easy for you to generate a title and precis overview of the given text with one click.

It takes the important key phrases from the content and combines them to create an accurate abstract with advanced AI.

Click to Copy

You can use this feature of our online abstract maker to copy the result text in real-time and paste it wherever you want without any hassle.

Download File

This feature lets you download the abstracted text in DOC format for future use just within a single click.

No Signup/Registration

This free text abstraction tool requires no signup or registration process to use it. Simply go the Editpad.org , search for the Abstract Generator, open it, and enter your text to create an abstract of any text within seconds.

Other Tools

- Plagiarism Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Reverse Text - Backwards Text Generator

- Small Text Generator - Small Caps / Tiny Text

- Upside Down Text Generator

- Words to Pages

- Case Converter

- Online rich-text editor

- Grammar Checker

- Article Rewriter

- Invisible Character

- Readability Checker

- Diff Checker

- Text Similarity Checker

- Extract Text From Image

- Text Summarizer

- Emoji Translator

- Weird Text Generator

- Stylish Text Generator

- Glitch Text Generator

- Cursive Font Generator

- Gothic Text Generator

- Discord Font Generator

- Aesthetic Text Generator

- Cool Text Generator

- Wingdings Translator

- Old English Translator

- Online HTML Editor

- Cursed Text Generator

- Bubble Text Generator

- Strikethrough Text Generator

- Zalgo Text Generator

- Big Text Generator - Generate Large Text

- Old Norse Translator

- Fancy Font Generator

- Cool Font Generator

- Fortnite Font Generator

- Fancy Text Generator

- Word Counter

- Character Counter

- Punctuation checker

- Text Repeater

- Vaporwave Text Generator

- Citation Generator

- Title Generator

- Text To Handwriting

- Alphabetizer

- Conclusion Generator

- List Randomizer

- Sentence Counter

- Speech to text

- Check Mark Symbol

- Bionic Reading Tool

- Fake Address Generator

- JPG To Word

- Random Choice Generator

- Thesis Statement Generator

- AI Content Detector

- Podcast Script Generator

- Poem Generator

- Story Generator

- Slogan Generator

- Business Idea Generator

- Cover Letter Generator

- Blurb Generator

- Blog Outline Generator

- Blog Idea Generator

- Essay Writer

- AI Email Writer

- Binary Translator

- Paragraph Generator

- Book Title generator

- Research Title Generator

- Business Name Generator

- AI Answer Generator

- FAQ Generator

- Active Passive Voice Converter

- Sentence Expander

- White Space Remover

- Remove Line Breaks

- Product Description Generator

- Meta Description Generator

- Acronym Generator

- AI Sentence Generator

- Review Generator

- Humanize AI Text

Supported Languages

- Refund Policy

Adblock Detected!

Our website is made possible by displaying ads to our visitors. please support us by whitelisting our website.

What do you think about this tool?

Your submission has been received. We will be in touch and contact you soon!

Free Abstract Generator

Make an abstract for your paper in 4 steps:

- Choose between a simple and an advanced option

- Paste the text or add the details

- Click “Generate”

- Check and copy the result

Your abstract may be:

- ⭐️ The Tool’s Benefits

- 🤔 Why Use Our Tool?

📝 What Is an Abstract?

- ✍️ How to Write It

- ✨ Abstract Example

🔗 References

⭐️ abstract generator: the benefits.

| 🌐️ 100% online tool | There is no need to download any apps on your device. |

|---|---|

| 🆓 100% free of charge | This abstract maker for students is absolutely free. |

| 🤗 100% user-friendly | The interface of this tool is intuitive and easy to use. |

| 🎓 Made for students | This online abstract maker is made for educational purposes. |

🤔 Why Use Online Abstract Generator?

Having trouble writing an abstract? You’re not alone.

Crafting an abstract can be problematic, especially when dealing with voluminous work. After all, converting a 100-page academic paper into 150 words is not an easy task. And this is where an abstract maker can help you immensely.

The amount of time you’ll save by relying on a machine to do the work for you is huge. Not to mention the result will be entirely error-free. No logical, grammatical, or other mistakes will spoil your piece.

Sounds interesting? Then, keep reading to learn more about abstracts and our generator.

An abstract is a brief summary of a work. Usually, it's a single paragraph containing 150 to 250 words. It describes all the key points and elements of an article, essay, or work of any other format.

Keep in mind that an abstract merely describes a text. It shouldn’t be an evaluation or an attempt to defend the paper. Instead, it’s just an overview.

Structure of an Abstract

An abstract is not a simple summary. It has a specific structure and should contain the following elements:

- The main issue . Describe the problem you are trying to solve with your research.

- The background . Include everything the reader needs to know before delving into your text.

- The goal . Don’t forget to describe the reasons behind your work.

- The methods . Tell the readers how exactly you performed your research.

- The results . What did you discover? If no particular result comes to mind, you can list your arguments here instead.

- The implications . Show the reader how significant your work is.

Remember that an abstract is separate from the rest of the paper. For the reader to get the complete picture of your research, your abstract must include everything listed above.

✍️ How to Write an Abstract

It can be tempting to go and write an abstract right away. But make sure to finish the planning of your work first. You want to write your abstract about your piece's contents, not build the contents around your abstract.

To make the writing process easier, divide it into 5 manageable steps:

- Check the requirements. First off, you need to know how much you are allowed to write. An average abstract is about 150-250 words long, but there is often a strict limit. Make sure to stay within it!

- Establish the goal and the problems of the research. The reader needs to know what your paper will be about right from the get-go. That’s why you need to formulate your thesis and showcase it first.

- Establish the methods. Tell the reader how you did your research. Don’t go in too deep: simply describe the methods without unnecessary details.

- Describe the results. Write a couple of sentences about the outcome of your investigation.

- Write a conclusion. Address the issue you established in the second step. You might also want to mention your work’s limitations regarding your research samples or methods. Try to give the reader a clear understanding of your goal and how you achieved it.

Want to make the process even easier? Use our abstract tool! Online generators like ours will help you craft an excellent paragraph in a matter of seconds.

Abstract Writing Tips

Finally, we want to help you make your abstract truly amazing. Check out our best tips below:

- It's best to get to the point immediately and without adding any filler or unnecessary details.

- The less specific your abstract is, the better.

- Check out some examples before you start writing. Sometimes the best way to learn something is to watch how everyone else does it.

- Avoid long sentences or bizarre vocabulary to make an abstract paragraph as concise as possible.

- It’s a great idea to single out some keywords from your outline and put them into your abstract.

- Don't forget about formatting. Any serious academic work has its requirements. Make sure you check them before writing your piece.

Following these simple tips will make you a master of abstract writing.

✨ Free Abstract Sample

As an example, check out this abstract of the article “Bioeffcacy of Mentha piperita essential oil against dengue fever mosquito” by Sarita Kumar:

The Mentha balsamea, or peppermint plant, is a result of cross-breeding between spearmint and water mint. These plants are most commonly used in the area of repelling insects. The following research revolves around peppermint oil insect repellent and its development. As a part of an experiment, we obtained 25 grams of fresh peppermint and, after grinding it, put it in a glass jar with olive oil. The jar was then left for two days in a warm temperate. Next, the oil was strained with a cheesecloth, gathered, and diluted at 70%. It then got separated into three different spray bottles. The test was to put the spray sample into a jar with mosquitoes and equate the result to the same test with a commercial repellant. Thus, we challenged the stereotype of synthetic repellents being more efficient than their analogs made from natural materials.

That will be the end of our guide on abstract writing. Thank you for reading, and make sure to try out our abstract writer tool to get the best results!

❓ Abstract Generator FAQ

❓ how do you write an abstract for a research paper.

You may use an abstract tool and make the writing process entirely automatic. If you can’t use it, write an abstract yourself by describing the following:

- The main problem.

- Background information.

- The end goal.

- Description of methods you used.

- The results of the research.

❓ What are the 5 parts of an abstract?

Parts of an abstract depend on the contents and limitations of your research. The 5 main elements are:

- The introduction

- Research significance

- Method description

❓ What makes a good abstract in a research paper?

A good abstract is one that:

- Meets all the requirements.

- Establishes the problem and main issues of the research.

- Describes the methods you used during the analysis.

- Showcases results of the study.

- Provides a clear conclusion.

❓ How long should my abstract be?

An average abstract is about 150-250 words long. You may often get strict limits that can go above or beyond these numbers. Your supervisor should provide the exact requirements for abstract length. So, make sure to double-check them.

Updated: Jun 18th, 2024

- Writing an Abstract: George Mason University

- Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper: University of Wisconsin - Madison

- Writing an Abstract: Australian National University

- The Abstract: The University of Toronto

Abstract Generator

0 Sentence 0 Words

AI Abstract Generator

Creating abstracts can be a challenging task that demands a meticulous approach. It involves carefully dissecting your entire paper and scrutinizing each section to ensure that the vital points are adequately covered while avoiding unnecessary details.

However, despite their difficulties, abstracts play an exceptionally significant role. If your goal is to get your work published, mastering the art of abstract writing becomes essential. Additionally, many academic assignments necessitate the inclusion of an abstract, making it a crucial component of the overall scholarly development process.

| Quickly Generates Abstracts | |

| 😍 Abstracts | Articles, Paragraphs & Sentences |

|---|---|

| 👨🏼🎓 Users | Students, Professionals & Writers |

| 💰 Pricing | 100% Free |

What is an Abstract?

An abstract is a summary of a document, highlighting the full text's main ideas, key points, methodology, results, and conclusions. Its purpose is to quickly understand the document's content without reading the entire text. Abstracts are commonly used in academia and research to help readers assess the relevance and significance of a work.

What are the various structures of an Abstract?

Abstracts can have two main structures:

Structured Abstract:

It follows a specific format with sections like background/objective, methods, results, and conclusion.

Unstructured Abstract:

This format allows more flexibility and is often used in humanities and social sciences.

Both structures serve the purpose of providing a concise overview of the document's main content and findings.

How SpinBot's AI Abstract Generator Tool works?

To use SpinBot's AI Abstract Generator APA, follow the steps below:

Copy and paste the content or upload the document you want to generate an abstract from.

For more accuracy click on Advance Summarize

Remember that SpinBot's Free AI Abstract Generator APA utilizes advanced natural language processing techniques to generate abstracts, but it is always a good idea to review and refine the generated abstract to ensure it accurately represents the original document's content and meets your specific requirements.

Who are the users of SpinBot's Ai Abstract Generator?

SpinBot's AI Abstract Generator is a versatile tool that caters to a wide range of users seeking to create concise and informative abstracts. They include:

SpinBot's AI Abstract Generator assists students in creating well-structured abstracts for their academic assignments, research papers, and projects.

... Read More

It supports teachers in guiding students to develop clear and concise abstracts, enhancing their understanding of abstract writing conventions and facilitating effective communication.

Researchers

Researchers can generate informative abstracts for their studies, enabling them to quickly and accurately summarize their research and share key insights.

It provides bloggers with a convenient tool to create engaging abstracts for their blog posts, captivating readers and giving them a preview of the content.

News Writers and Columnists

SpinBot's AI Abstract Generator helps news writers and columnists craft compelling abstracts for articles, ensuring readers can quickly grasp the main points.

It supports podcasters in creating concise and attention-grabbing abstracts for their episodes, enticing listeners, and summarizing the topics covered.

What are the features of SpinBot's AI Abstract Generator?

Besides its impressive speed, SpinBot's Abstract Creator offers the advantage of being highly accessible. It has been optimized for mobile and desktop usage, allowing users to access the tool from anywhere. Furthermore, the AI abstract generator has the following features:

Generates Abstracts Instantly

SpinBot's AI Abstract Generator allows users to generate abstracts instantly, eliminating the need for time-consuming manual summarization and accelerating the abstract creation process, saving valuable time and effort.

Increases Productivity

By automating the abstract generation process, SpinBot's AI Abstract Generator boosts productivity, enabling users to quickly create high-quality abstracts and focus their time and energy on other important tasks.

Uses AI & ML Technology

Powered by advanced AI and ML technologies, the tool ensures accurate analysis and extraction of key information, resulting in well-crafted abstracts that effectively summarize the content.

Protects Data Privacy

SpinBot prioritizes data privacy and security. The AI Abstract Generator provides a secure platform where users can generate abstracts without worrying about their confidential or sensitive information being compromised or stored.

Remains Free to Use

SpinBot's AI Abstract Generator is available for free, offering accessibility to all users without any cost involved. Users can take advantage of its features and generate abstracts without any financial barriers or restrictions.

How users can create Abstracts for research papers?

Here is a step-by-step guide to writing an abstract:

Step 1: Draft your research paper

Begin by writing your paper, saving the abstract for the end so you can accurately summarize the findings.

Step 2: Review abstract requirements

Familiarize yourself with any specific requirements, such as length or style, if you're writing for publication or a work project.

Step 3: Tailor the abstract to your target audience

Take into account your audience and the intended publication. Adapt the language and level of detail accordingly.

Step 4: Introduce the problem

Start by explaining the problem your research addresses or aims to solve, including the main claim or argument and the scope of your study.

Step 5: Outline your research methods

Describe the methods you employed in your study, including the research conducted, variables considered, and approach taken. Support your assertions with evidence.

Step 6: Highlight the research findings

Share the general findings and answers derived from your study. If necessary, highlight the most significant results.

Step 7: Summarize

Conclude your summary by discussing the meaning of your findings and emphasizing the paper's importance. In the case of an informative abstract, also address the implications of your work.

By following these steps, you can effectively write an abstract that provides a concise and informative overview of your research paper.

Hear what our clients say

Don't just take our word for it, hear what people have to say about us.

What not to say in an abstract?

It is important to avoid providing excessive background information, detailed methodology, extensive citations, subjective statements, personal opinions, or ambiguous language in an abstract. The abstract should focus on conveying the key findings, main arguments, and implications of the research concisely and objectively.

What are the 4 C's of abstract writing?

The 4 C's of abstract writing are clarity, conciseness, completeness, and coherence. Clarity ensures that the abstract is easy to understand, conciseness involves presenting information succinctly, completeness includes covering all key aspects, and coherence ensures that the abstract flows logically and cohesively.

Why is writing an abstract so hard?

Writing an abstract can be challenging due to the inherent difficulty of condensing a complex and detailed content into a concise and coherent summary. It requires careful selection of information, balancing brevity with clarity, and effectively capturing the essence of the work while maintaining its relevance and significance.

What tense should be used in an abstract?

The present tense is commonly used in abstracts to describe the research findings, methodology, and conclusions. However, the specific tense usage may vary depending on the field or journal guidelines. It is recommended to consult the specific guidelines or conventions of the target publication for precise tense usage.

What is the first step in writing an abstract?

The first step in writing an abstract is thoroughly reading and understanding the entire document. Familiarize yourself with the research question, objectives, methodology, major findings, and conclusions. These steps help you identify the key elements that must be included in the abstract and ensure a comprehensive and accurate summary.

What are other tools by SpinBot?

Apart from the free abstract generator, SpinBot offers several other useful tools. These include the Article Rewriter, which helps paraphrase and rewrite text; the Grammar Checker, which identifies grammar and spelling errors; and the Word Counter, which provides accurate word and character counts for text.

Abstract Generator

This Abstract Generator is basically a guideline for writing abstracts. We have also written an article on how to write abstracts. Go through the post and use our tools to create properly formatted abstracts. Note: An abstract should be between 100 - 250 words.

- Plagiarism Checker

- Paraphrasing

- Essay Generator

- Image To Text

Abstract Generator

Table of Contents

Free Abstract Generator

Prepostseo’s Abstract Generator is an online tool that uses AI technology to help you automatically generate abstracts for your thesis, articles, or research papers. Our abstract maker uses accurate AI and language models to collect the most important phrases from a given content, to generate accurate abstracts.

How to Write Abstract By the Free AI Abstract Generator?

Below are the steps to generate abstracts with the help of our AI abstract maker tool:

Type or paste your writing into the input box of our AI abstract maker.

Simply, hit the “ Generate ” button.

The tool will write the abstract in the output box of the tool.

Finally, “ Copy ” or “ Download ” your abstract.

Best AI Abstract Generator: Online & Free

Here is your abstract

If you want to create beautiful abstracts and drastically improve the quality of your research, you've come to the right place. Meet our new mind-blowing AI abstract generator! It will create a fantastic piece of text that incorporates every critical aspect of your research.

- ️🤖 How to Use the Tool

- ️💡 Why Use the Abstract Generator?

- ️🔬 What Is an Abstract?

- ️✅ Abstract Types

- ️✍️ How to Write an Abstract

- ️📝 Abstract Example for Free

- ️❓ AI Abstract Generator FAQ

- ️🔗 References

🤖 How to Use Our Abstract Generator Online

- Paste your text into the empty field.

- Fill in all 5 advanced fields if necessary.

- Press “Generate.”

- An AI bot will generate an abstract for you!

💡 Why Use Our AI Abstract Generator?

Our generator is one of the best study tools you can find online. Here are its most notable advantages:

| 💸 100% free | Use it at no cost! |

|---|---|

| 🤩 Intuitive design | Enjoy the user-friendly interface. |

| 🌐 Readily available | No need to create an account. |

| 🚀 No limits | Generate an unlimited number of abstracts. |

| 💎 Various uses | Works with any academic subject. |

🔬 What Is an Abstract?

An abstract is a paragraph that gives readers a general synopsis of your research's contents and structure. It should include your thesis , main points, methodology, and findings. An abstract is usually 150-200 words in length.

It serves the following purposes:

- Helps to navigate your arguments.

- Allows readers to grasp the main idea from your text quickly.

- Aids in remembering key points from your paper.

✅ Abstract Types

Abstracts come in two general types: informative and descriptive . They differ in terms of components and styles because they have separate goals.

- A descriptive abstract indicates what information is included in your research. It doesn't provide study findings or conclusions. Some view it as an outline of the work rather than a synopsis. Typically, descriptive abstracts are brief, with 100 words or less.

- An informative abstract combines the material provided in a descriptive one (goal, methods, and scope) with the research's findings and conclusions. An informative abstract is usually around 10% of the work in length.

✍️ How to Write an Abstract

Now that you know what abstracts are, it's time to learn how to write them . Just follow our handy step-by-step guide below!

1. Define the Purpose of Your Research

The first step to writing an abstract is clearly outlining your research's general objective and purpose. To do it, answer the following question: What theoretical or practical issue does your study address, and which topic do you want to investigate?

It's better to avoid providing extensive background. Instead, give a brief answer to why your topic is essential. Also, don’t forget to explain all the technical words and terms if you plan to use them in your research.

2. Review the Requirements

You may receive specific requirements from your instructor about the length or style of your project. Neglecting them can result in failing your assignment. That's why it's best to review all the requirements before writing an abstract.

3. Explain the Problem and the Methods

This step requires you to outline a particular issue that your research focuses on and aims to resolve.

- Determine the focus of your study as well as your main arguments.

- Additionally, explain the methodology that you’ve used to make your arguments.

- Don’t forget to mention the evidence that proves your point.

4. Summarize the Findings

Every abstract requires a summary of the research's key findings. If you can’t cover everything, emphasize only the most significant points. Try to draw attention to those aspects that will help the reader understand your conclusions.

5. Conclude

The final step is to conclude your abstract. You can do it by addressing the significance of your findings and the role of your entire research. Note that you will need to write a summary for both types of abstracts, yet only the informative abstract will require you to discuss the effects of your work.

📝 Abstract Example for Free

We've prepared an example of a good abstract made with the help of our online generator. Feel free to use it to boost your inspiration.

Supplies and reserves affect the company's performance, so the choice of methods for controlling the inventory is a critical topic in modern management.

This research aims to study the possibilities of implementing the most effective inventory management system at the enterprise.

This work presents the results of quantitative and qualitative studies of the existing methods of inventory management. The data obtained made it possible to identify the advantages and disadvantages of various methods. Additionally, this research provides recommendations for using different inventory management systems, such as ERP and GSRP.

We hope that you've enjoyed our guide! To get an even better result, try our free abstract generator online. It will help you save time and enhance your academic writing skills. Good luck!

We also recommend using our conclusion generator and research question maker .

❓ AI Abstract Generator FAQ

❓ is there an abstract generator.

You can try out different apps on the internet, but our tool is definitely the best. StudyCorgi’s abstract generator is 100% free and unlimited. Besides, you can use it on any device. Try it out!

❓ How do I create an abstract online?

You can create an abstract using our abstract generator online. To do it, simply fill in all empty fields and press “Generate.” After creating your abstract, you can copy it and polish it however you like. This is how you make a perfect abstract online!

❓ Can AI write an abstract for me?

Our generator's AI can make an abstract for any subject or topic. It has a machine-learning system and can generate abstracts like a real human writer. You can use abstracts made by our app however you want—there are no copyright restrictions!

❓ Is 150 words good for an abstract?

The answer depends on the length of your research paper and the abstract type. For example, if you need to create a descriptive abstract, then 150 words is too lengthy. If your abstract is informative, then its length should be around 150-200 words.

Updated: Jun 5th, 2024

🔗 References

- Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper: University of Wisconsin – Madison

- Writing an Abstract: The University of Melbourne

- Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: The Abstract: University of Southern California

- Abstract Samples: Michigan State University

- Writing an Abstract: George Madison University

Free Abstract Generator for Research Papers

- 🚀 Meet Our Abstract Generator

📃 What Is an Abstract?

- ✍️ How to Write an Abstract

- 🫣 7 Mistakes You Should Avoid

🔗 References

🚀 meet our abstract generator for research papers.

The abstract provides a brief overview of the research assignment. So, this part gives a general assessment of the work and encourages the reader to explore it further. Almost every student dealt with the difficult task of condensing their research results into several hundred words. But that’s not a problem anymore!

We used artificial intelligence to make a tool that will make your academic life more enjoyable . You can get an excellent example of an abstract specifically for your research paper in minutes. To do this, you need to specify the reason for the research, the problems, and the goals. Also, we recommend mentioning the methodology and your findings to ensure the outcome is accurate. After that, the AI abstract maker will do the rest for you!

Key Reasons to Use Our Online Abstract Generator

Students juggle various assignments and obligations. Research papers are among the most challenging tasks they have to complete. What makes them so difficult is the sheer volume of information and study involved. Dealing with large amounts of material often leaves students drained and incapable of summarizing their work correctly.

Our abstract generator for research papers makes this process more straightforward thanks to several factors:

| ✅ Customization | The platform generates abstracts for all types of papers. |

|---|---|

| ✅ Free use | Our tool is provided completely free of charge. |

| ✅ Speed | The abstract generator produces results in a matter of minutes. |

| ✅ User-friendliness | The summary AI writer is accessible to people from all walks of life. |

Abstracts provide short summaries of larger works, including research papers and dissertations. Readers scan them to decide whether or not they wish to continue reading the rest of the paper. In about 150–200 words, you should state the problem and provide the research goal, results, implications, and used methods.

One should write research abstracts only after the rest of the work is ironed out and ready. While this part of research may seem insignificant, students should take the time to write the abstract well. Doing so lets them identify any flaws in the research methodology and results.

Types of Research Paper Abstracts

Many students believe that abstracts come only in one type. In reality, there are several versions of summaries used in academic circles.

- Critical Abstract . These are the most extensive abstracts, at around 450 words. Unlike other entries on this list, they encourage deep analysis: for example, a discussion about the validity or reliability of their studies. It’s mostly used in social science research .

- Descriptive Abstract . This format is quite similar to informative abstracts but much shorter. On average, this type is only 100 words long and covers the main focus of the studies. Descriptive summaries offer no conclusions or recommendations for further research.

- Highlight Abstract . Students rarely get to use this type, as its primary goal is to get the reader’s attention. Highlight abstracts don’t helpfully summarize papers . Instead, they concentrate on the unique parts of the research, such as its results and conclusions.

- Informative Abstract . This is the most common type used by researchers and writers. It provides primary information about research concepts, methodology, findings, and recommendations. Sometimes, informative research abstracts have keywords listed at the bottom, but this practice is mainly reserved for professional publications.

✍️ How to Write an Abstract in 5 Steps

Despite the incredible versatility of our abstract generator, it’s still important to learn how to make abstracts on your own. We’ve dedicated this part of the guide to the five steps of writing these summaries. So, these instructions will help you create an abstract for any academic paper.

- Write the paper . To create an abstract, you first need a research paper. Create an outline of the study detailing the problem and methods you’ll use to address it. Explain the research methodology, state what information can be extracted from it, and show how the findings apply to the overall field of study.

- Review paper requirements . Once you’re done with the draft, review the criteria provided by the educational institution. Use the supporting documents with instructions, as they can clarify the requirements for the work's style, formatting, and length. Different disciplines require specific styles, so read this information carefully.

- Consider the audience . When working on an abstract, it’s crucial to identify who will be reading it afterward. For example, students often adjust their language to reach the general public and not only their respective professors.

- Write the abstract . Now, write the abstract based on the provided requirements. Use the body of the research to summarize the problem, explain the methods used in the paper , and show what their results were. Finish the summary by telling why your findings are valuable to the study field and what can be done in further research.

- Iron it out . Like with all writing pieces, it's essential to review the abstract and check if it has all the necessary components. The text should be easy to follow, cover all points, and be informative. As the abstract creates the first impression, make it a good one.

Abstract Formats: MLA & APA Styles

Abstract types aren’t the only things students should look out for. In academic settings, several formatting styles detail how the text should look on paper. The majority of US colleges use two popular methods: MLA and APA . Here, we discuss how abstracts look in each of them.

- Abstracts have their own page directly after the title or cover pages.

- In the APA style, the first line on the page is the word “Abstract” in the center without quotation marks.

- The following line in APA abstracts summarizes the critical points of the research. It introduces the main topic, questions, methodology, findings, and conclusions.

- Use double spaces and make the abstract under 250 words.

- Include keywords after the summary in APA format to help people find the work in various databases.

- Start with a sentence that contains the thesis statement and reason for readers to care about the research.

- Use short and simple sentences with precise words and phrases, as the abstract needs to be easy-to-understand.

- Use transitional words and phrases to make the writing flow and connect ideas more efficiently.

- Edit the abstract until it is 5-7 sentences long or under 250 words.

- Avoid using footnotes and citations.

🫣 7 Mistakes You Should Avoid When Writing an Abstract

Writing abstracts is a pretty straightforward process. But it doesn’t mean that everybody is immune from making mistakes, especially after spending days toiling away on a research paper.

There are seven common errors everybody should check before submitting an abstract.

- Making it too long . A summary should concisely describe the whole paper. Avoid repetition and details that have little to do with the research.

- Using chopped-up sentences . Ensure that your paper contains only complete sentences. It makes the work more professional and easier to comprehend.

- Adding too much technical jargon . Keep things simple so that anyone reading the abstract understands what it’s about. It will also make more people check out your paper.

- Not correcting the text . Sometimes, students want to finish a work without editing it too much. Take the time and comb the document for errors and factual mistakes.

- Failing to explain the significance of the research . The first couple of sentences should give readers a clear understanding of why the study is essential.

- Using the wrong tense . It’s recommended that abstracts be written in the past tense. Some academic institutions won’t accept papers with improperly written abstracts.

- Too many adjectives and hyperboles . You aren’t writing a 19th-century novel but an academic paper. The work should reflect that, so avoid using too many literary devices .

We hope you’ve found this article interesting and helpful in your academic pursuits. We also suggest taking a look at our guide for creating an excellent research paper . If you have any more questions about the art of writing abstracts, check out the FAQ section below.

❓ Research Abstract Generator – FAQ

- It’s written for the right audience.

- It's in the past tense and third person.

- Stands alone on the page.

- Has keywords and critical references.

- Reason for writing it and the importance of the research.

- Problematics the work attempts to solve.

- Methodology behind the study.

- Results backed by specific data.

- Practical and theoretical applications of the findings.

Updated: Oct 25th, 2023

- What Exactly is an Abstract? – Regents of the University of Michigan

- Abstract and Keywords Guide. – American Psychological Association

- Writing an Abstract. – The University of Melbourne

- Six Steps to Write an Abstract. – The University of Alabama

- How To Write an Abstract in 7 Steps (With an Example). – Indeed

- MLA Formatting: How Do I Do: An Abstract. – Warner Pacific University Library

- Abstracts. – The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Free Essays

- Writing Tools

- Lit. Guides

- Donate a Paper

- Referencing Guides

- Free Textbooks

- Tongue Twisters

- Job Openings

- Video Contest

- Writing Scholarship

- Discount Codes

- Brand Guidelines

- IvyPanda Shop

- IvyPanda Academy

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Copyright Principles

- DMCA Request

- Service Notice

This article offers an excellent generator for students to craft compelling abstracts. Also, you can explore our guide and tips on writing an abstract for research papers. Learn how to streamline the abstract-writing process and ensure your work gets the attention it deserves.

Research Paper Abstract Generator

Writing the abstract for your research paper, dissertation, or book chapter is usually one of the final steps before you submit your work. It’s also the activity that many students and researchers find most difficult. A strong abstract must be clear, succinct and informative, but how do you decide what to include?

Structuring your abstract

Many journals require the abstract to be structured according to

whereas the abstract for your dissertation or chapter may just be a short narrative paragraph. Either way, the abstract should contain key information from the study and be easy to read. Creating an abstract is as much an art as a science.

Happily, Scholarcy can help by identifying exactly the right information to include in your abstract.

Abstract in numbers

4 steps to generate an abstract with scholarcy, upload your article.

Simply upload your article to Scholarcy Library to generate a summary flashcard that outlines your research and contains the information needed to create your abstract.

View Scholarcy Highlights

The Scholarcy Highlights tab contains 5-7 bullet points comprising the background to the study, the key findings, and the conclusion.

View Scholarcy Summary

If your paper contains standard IMRaD sections, then the Scholarcy Summary will automatically be structured to follow these headings and will include any study objectives that you have written.

And the Study subjects and participants tab extracts key information about study participants, interventions, and quantitative results. Perfect for your abstract!

Try Smart Synopsis

Alternatively, for your dissertation or book chapter, you can use our Smart Synopses tool to create a more naturally flowing, narrative abstract.

What People Are Saying

“Quick processing time, successfully summarized important points.”

“It’s really good for case study analysis, thank you for this too.”

“I love this website so much it has made my research a lot easier thanks!”

“The instant feedback I get from this tool is amazing.”

“Thank you for making my life easier.”

Privacy Overview

Generate accurate APA citations for free

- Knowledge Base

- APA Style 7th edition

- How to write and format an APA abstract

APA Abstract (2020) | Formatting, Length, and Keywords

Published on November 6, 2020 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on January 17, 2024.

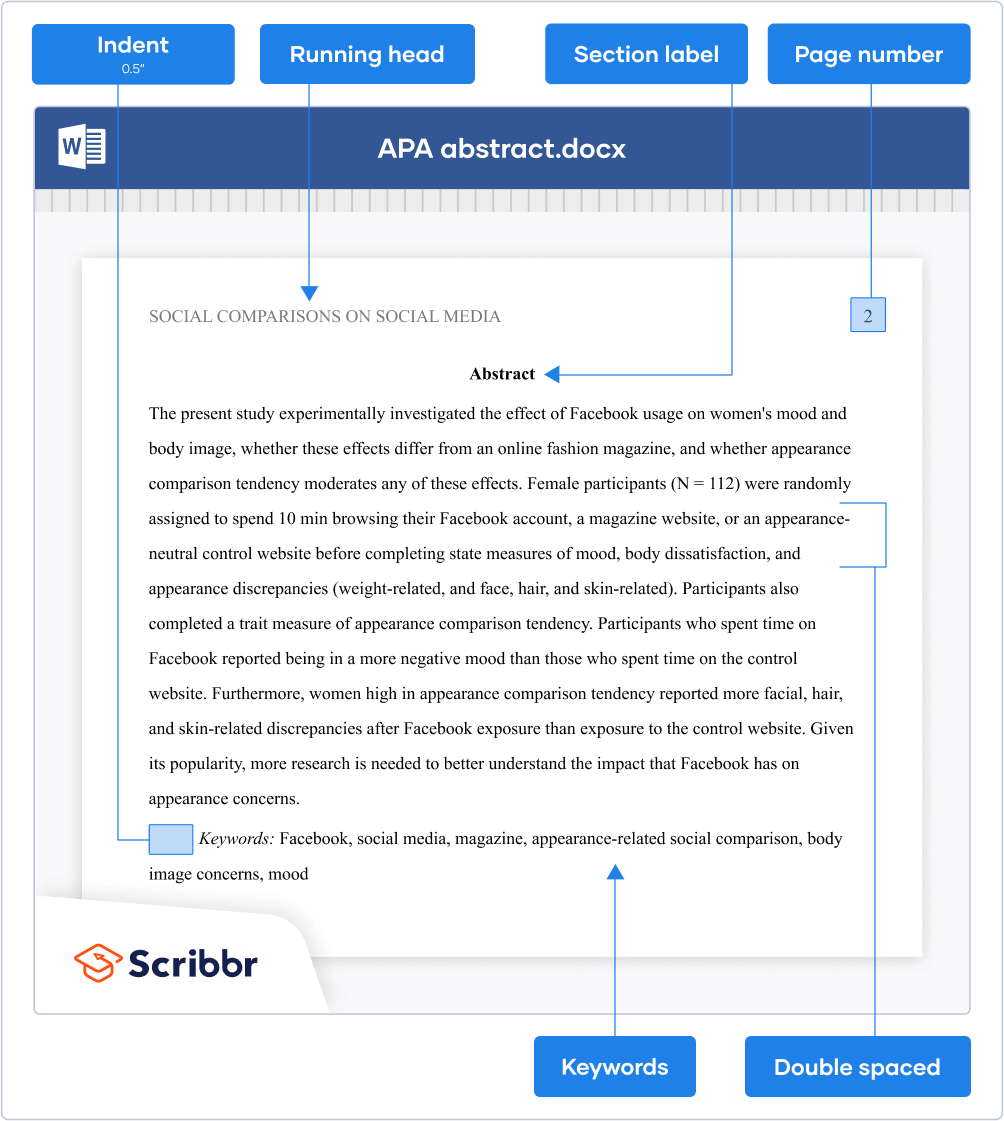

An APA abstract is a comprehensive summary of your paper in which you briefly address the research problem , hypotheses , methods , results , and implications of your research. It’s placed on a separate page right after the title page and is usually no longer than 250 words.

Most professional papers that are submitted for publication require an abstract. Student papers typically don’t need an abstract, unless instructed otherwise.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

How to format the abstract, how to write an apa abstract, which keywords to use, frequently asked questions, apa abstract example.

Formatting instructions

Follow these five steps to format your abstract in APA Style:

- Insert a running head (for a professional paper—not needed for a student paper) and page number.

- Set page margins to 1 inch (2.54 cm).

- Write “Abstract” (bold and centered) at the top of the page.

- Do not indent the first line.

- Double-space the text.

- Use a legible font like Times New Roman (12 pt.).

- Limit the length to 250 words.

- Indent the first line 0.5 inches.

- Write the label “Keywords:” (italicized).

- Write keywords in lowercase letters.

- Separate keywords with commas.

- Do not use a period after the keywords.

Are your APA in-text citations flawless?

The AI-powered APA Citation Checker points out every error, tells you exactly what’s wrong, and explains how to fix it. Say goodbye to losing marks on your assignment!

Get started!

The abstract is a self-contained piece of text that informs the reader what your research is about. It’s best to write the abstract after you’re finished with the rest of your paper.

The questions below may help structure your abstract. Try answering them in one to three sentences each.

- What is the problem? Outline the objective, research questions , and/or hypotheses .

- What has been done? Explain your research methods .

- What did you discover? Summarize the key findings and conclusions .

- What do the findings mean? Summarize the discussion and recommendations .

Check out our guide on how to write an abstract for more guidance and an annotated example.

Guide: writing an abstract

At the end of the abstract, you may include a few keywords that will be used for indexing if your paper is published on a database. Listing your keywords will help other researchers find your work.

Choosing relevant keywords is essential. Try to identify keywords that address your topic, method, or population. APA recommends including three to five keywords.

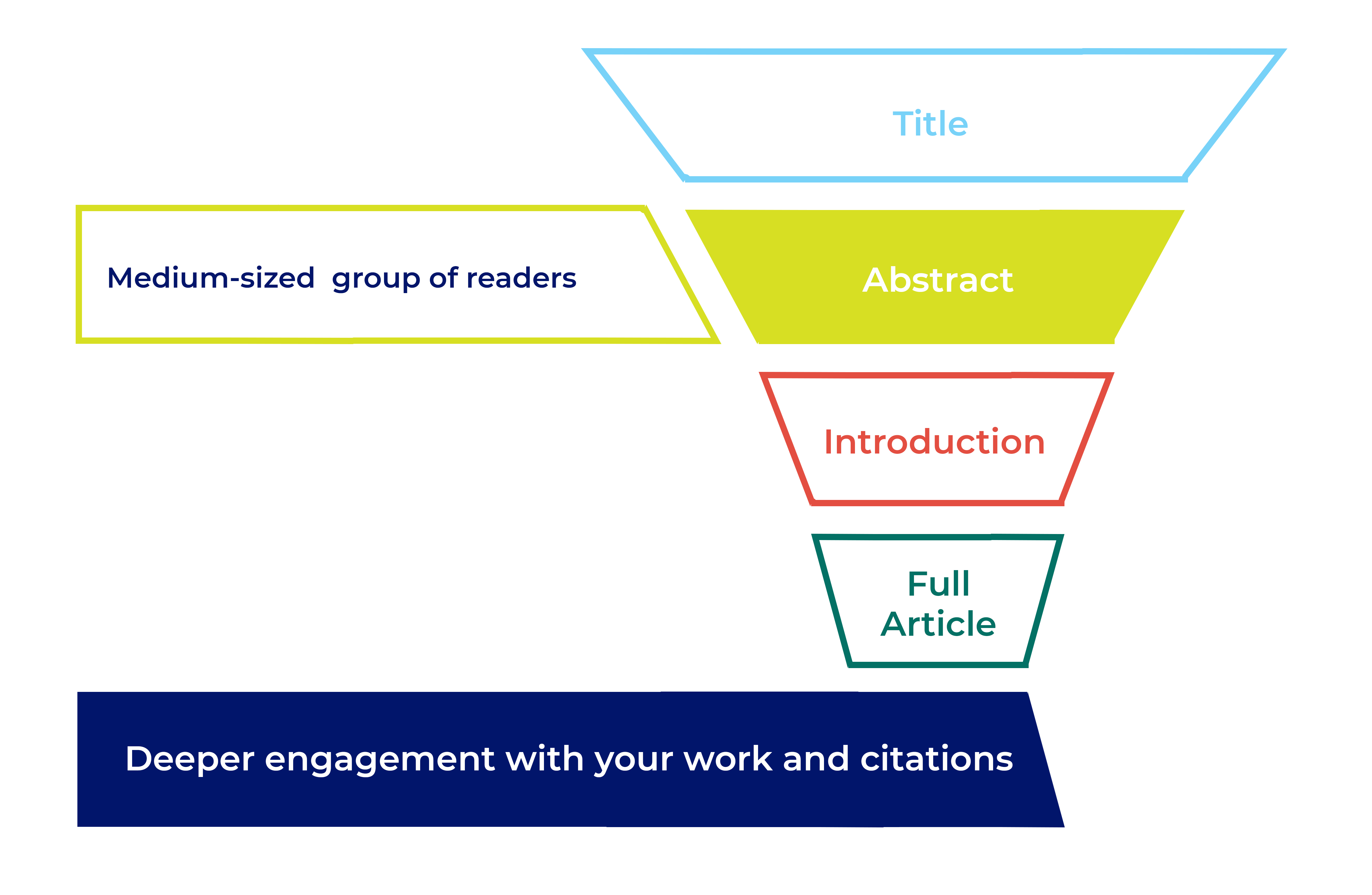

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

An APA abstract is around 150–250 words long. However, always check your target journal’s guidelines and don’t exceed the specified word count.

In an APA Style paper , the abstract is placed on a separate page after the title page (page 2).

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2024, January 17). APA Abstract (2020) | Formatting, Length, and Keywords. Scribbr. Retrieved June 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/apa-style/apa-abstract/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

Other students also liked, apa headings and subheadings, apa running head, apa title page (7th edition) | template for students & professionals, scribbr apa citation checker.

An innovative new tool that checks your APA citations with AI software. Say goodbye to inaccurate citations!

Best Abstract Generator: Generate Abstracts For Research Papers

In the ever-evolving landscape of academic research, AI-powered tools are revolutionising the art of abstract writing. Abstrazer, Scholarcy, WriteFull, and ChatGPT are leading the charge, offering students and researchers efficient ways to condense extensive research into concise summaries.

Harnessing advanced AI algorithms, these tools ensure clarity, grammatical accuracy, and relevance, catering to a diverse range of academic needs. Which of these tools are best for you? Let’s find out.

Best Online Abstract Generator Tool

| Automatic abstract generation Advanced AI technology Concise summaries APA formatting Plugins for academic platforms Mobile & desktop compatibility | |

| AI-powered Quick abstract generation Reads full papers Grammatical accuracy Versatile use cases Language editing Free & premium options. | |

| AI-powered abstracts User-friendly interface Free high-quality abstracts Title generator Paraphrasing & formalizing tools Mobile & desktop access. | |

| Data-driven coherence User-prompted abstracts APA formatting AI-assisted writing Complements researcher expertise. |

Abstrazer offers students and researchers a unique platform to automatically generate abstracts for their research papers, cutting down the arduous process of abstract writing.

Given the specific requirements of abstracts, which typically hover between 150 to 250 words, this tool ensures conciseness without omitting key information.

The strength of Abstrazer lies in its advanced AI technology, which streamlines the abstract generation process.

If you’re grappling with summarizing your paper’s key findings and methods, Abstrazer provides a concise summary by eliminating unnecessary details and highlighting only the pivotal points.

It’s been designed to cater to a wide range of users, ensuring a well-structured abstract irrespective of the academic paper’s complexity.

What sets Abstrazer apart is its versatility. For instance, if one’s specific requirement revolves around APA formatting, the abstract generator utilizes advanced AI feature ensures accurate formatting with spot-on language edits.

This online abstract maker is especially handy when the task of abstract creation seems daunting. With a few inputs, Abstrazer simplifies the process of creating compelling abstracts that resonate with the intended audience.

Additionally, this AI-based tool is also available within various academic platforms through plugins, making it a handy tool on both mobile and desktop interfaces.

For those aiming for error-free, high-quality abstracts, Abstrazer is the go-to tool. It promises efficiency, saving precious time and effort, while still ensuring the final output gives the reader an apt snapshot of the research, making the academic journey a tad easier.

Scholarcy, an online abstract generator, offers a solution for students and researchers grappling with the challenge of abstract writing.

With the increasing demand for a tool to create concise summaries, this AI-powered abstract generator has risen to the occasion. While writing an abstract can be challenging, this tool simplifies the process of creating engaging and compelling abstracts for your research paper.

To use this tool, simply upload your academic paper. Within seconds, Scholarcy automatically generates an abstract that’s well-structured and caters to a wide range of users.

Its AI-based technology reads the entire paper, from introduction to conclusion, and provides a concise summary, highlighting key findings and key points without unnecessary details. The resulting abstract is typically between 150 to 250 words, making it apt for publication guidelines.

What makes Scholarcy stand out is its advanced AI technology. This abstract generator APA utilizes advanced algorithms to ensure abstracts are grammatically correct and error-free.

The abstract generator is a versatile tool, ideal for:

- Literature reviews

- Academic articles

For those with specific requirements, Scholarcy offers language edits to ensure conciseness and accuracy. Additionally, the abstract creator offers plugins for both mobile and desktop, making it accessible to a vast audience.

This free abstract generator saves time and effort, eliminating the struggle to write abstracts manually.

One notable feature is the daily quota for free abstract generation, ensuring users can create abstracts without any cost. However, for those requiring more, premium options are also available within the platform.

Writefull is an AI-powered tool designed to aid researchers in creating well-structured abstracts for their academic papers.

It’s no secret that generating an abstract can be challenging; after all, summarizing months or even years of research into a concise summary isn’t easy.

This is where the Writefull’s abstract generator steps in, simplifying the process of creating compelling abstracts by using advanced AI technology.

The online abstract maker allows you to paste content from your research paper – from the introduction to the conclusion – and automatically generates an abstract, honing in on the key points and findings of your work.

The beauty of this tool is its ability to produce high-quality abstracts without any cost. The abstract generator online not only ensures accurate and concise summaries but also saves time and effort, especially for students and researchers who have a tight daily quota or are on tight deadlines.

In addition to abstract writing, Writefull also offers a title generator to help craft the perfect headline for your research paper. The tool caters to a wide range of users, providing a concise summary while removing unnecessary details, ensuring grammatical accuracy and an error-free result.

But Writefull’s features don’t end there. This versatile tool also offers:

- Paraphrasing option

- Aids in language edits, and

- An ‘Academizer’ feature that turns informal text into formal academic language.

Fascinatingly, the abstract generator APA utilizes advanced AI to distinguish content generated by AI from original text, ensuring the authenticity of your work.

Moreover, the platform is accessible both on mobile and desktop and even offers plugins for instant access. For those who prioritize conciseness and accuracy, Writefull is the go-to solution, ready to serve specific requirements and create engaging abstracts within seconds.

ChatGPT, developed by OpenAI, is a potent abstract generator that, when used right, can provide a high-quality abstract tailored to your academic paper.

Its development process is grounded on extensive datasets, which allows the tool to create abstracts that are not only coherent but original.

This AI-powered abstract generator is a versatile tool that can cater to a wide range of users, from students trying to generate an abstract for their thesis to seasoned researchers working on extensive literature reviews.

One of the unique features of ChatGPT is its ability to generate abstracts based on specific prompts provided by the user.

With just a few clicks, ChatGPT automatically generates an abstract, streamlining the abstract writing process and ensuring conciseness. Users have found it helpful, especially when dealing with specific requirements for their abstracts, which often must be between 150 to 250 words.

This AI-based tool ensures the elimination of unnecessary details, highlighting only the key points that give the reader a well-structured summary of the research.

It’s like having an AI writing assistant that helps you write abstracts efficiently.

While ChatGPT simplifies the process of creating abstracts, it’s essential to note that this AI tool should supplement and not replace the expertise of the researcher. It saves time and effort, but the output should always be reviewed for grammatical accuracy and relevance.

In an ever-evolving academic landscape, the introduction of tools like ChatGPT, powered by advanced AI, is a testament to how technology can assist students and researchers in producing error-free, compelling abstracts for their work.

Wrapping Up: Generate An Abstract From A Research Paper Easily

Navigating the realm of academic research, tools like Abstrazer, Scholarcy, WriteFull, and ChatGPT are leveraging advanced AI to simplify abstract creation. Each offers unique features, from automatic abstract generation to specific formatting like APA.

Designed to cater to various users, from students to seasoned researchers, these platforms streamline the abstract-writing process, ensuring concise and coherent summaries. They highlight the potential of AI in academic writing, merging efficiency with quality.

Dr Andrew Stapleton has a Masters and PhD in Chemistry from the UK and Australia. He has many years of research experience and has worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow and Associate at a number of Universities. Although having secured funding for his own research, he left academia to help others with his YouTube channel all about the inner workings of academia and how to make it work for you.

Thank you for visiting Academia Insider.

We are here to help you navigate Academia as painlessly as possible. We are supported by our readers and by visiting you are helping us earn a small amount through ads and affiliate revenue - Thank you!

2024 © Academia Insider

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write an Abstract

Expedite peer review, increase search-ability, and set the tone for your study

The abstract is your chance to let your readers know what they can expect from your article. Learn how to write a clear, and concise abstract that will keep your audience reading.

How your abstract impacts editorial evaluation and future readership

After the title , the abstract is the second-most-read part of your article. A good abstract can help to expedite peer review and, if your article is accepted for publication, it’s an important tool for readers to find and evaluate your work. Editors use your abstract when they first assess your article. Prospective reviewers see it when they decide whether to accept an invitation to review. Once published, the abstract gets indexed in PubMed and Google Scholar , as well as library systems and other popular databases. Like the title, your abstract influences keyword search results. Readers will use it to decide whether to read the rest of your article. Other researchers will use it to evaluate your work for inclusion in systematic reviews and meta-analysis. It should be a concise standalone piece that accurately represents your research.

What to include in an abstract

The main challenge you’ll face when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND fitting in all the information you need. Depending on your subject area the journal may require a structured abstract following specific headings. A structured abstract helps your readers understand your study more easily. If your journal doesn’t require a structured abstract it’s still a good idea to follow a similar format, just present the abstract as one paragraph without headings.

Background or Introduction – What is currently known? Start with a brief, 2 or 3 sentence, introduction to the research area.

Objectives or Aims – What is the study and why did you do it? Clearly state the research question you’re trying to answer.

Methods – What did you do? Explain what you did and how you did it. Include important information about your methods, but avoid the low-level specifics. Some disciplines have specific requirements for abstract methods.

- CONSORT for randomized trials.

- STROBE for observational studies

- PRISMA for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Results – What did you find? Briefly give the key findings of your study. Include key numeric data (including confidence intervals or p values), where possible.

Conclusions – What did you conclude? Tell the reader why your findings matter, and what this could mean for the ‘bigger picture’ of this area of research.

Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND convering all the information you need to.

- Keep it concise and to the point. Most journals have a maximum word count, so check guidelines before you write the abstract to save time editing it later.

- Write for your audience. Are they specialists in your specific field? Are they cross-disciplinary? Are they non-specialists? If you’re writing for a general audience, or your research could be of interest to the public keep your language as straightforward as possible. If you’re writing in English, do remember that not all of your readers will necessarily be native English speakers.

- Focus on key results, conclusions and take home messages.

- Write your paper first, then create the abstract as a summary.

- Check the journal requirements before you write your abstract, eg. required subheadings.

- Include keywords or phrases to help readers search for your work in indexing databases like PubMed or Google Scholar.

- Double and triple check your abstract for spelling and grammar errors. These kind of errors can give potential reviewers the impression that your research isn’t sound, and can make it easier to find reviewers who accept the invitation to review your manuscript. Your abstract should be a taste of what is to come in the rest of your article.

Don’t

- Sensationalize your research.

- Speculate about where this research might lead in the future.

- Use abbreviations or acronyms (unless absolutely necessary or unless they’re widely known, eg. DNA).

- Repeat yourself unnecessarily, eg. “Methods: We used X technique. Results: Using X technique, we found…”

- Contradict anything in the rest of your manuscript.

- Include content that isn’t also covered in the main manuscript.

- Include citations or references.

Tip: How to edit your work

Editing is challenging, especially if you are acting as both a writer and an editor. Read our guidelines for advice on how to refine your work, including useful tips for setting your intentions, re-review, and consultation with colleagues.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- Pricing(20% Off)

- Account Center

Convert PDF

More pdf tools, organize pdf, protect pdf, image tools, ai abstract generator.

Page loading...

Auto-generate Abstract for Your Paper

Online free ai abstract generator, streamlined abstract generation for everyone, your file security and privacy are guaranteed..

How to Use AI to Generate Abstracts Online for Free

Step 01. upload your pdf to the ai abstract generator., step 02. ai analyzes pdf and generates summaries., step 03. effortlessly revise the generated abstract with ai., make ai abstract generator work efficiently for you, summarize academic studies effortlessly..

Generate informative abstracts for diverse content types.

Swiftly extract abstracts and key points for efficient understanding.

FAQs about Using AI Abstract Generator

What is an abstract.

An abstract is a concise summary that provides an overview of the main points or key elements of a document, research paper, or article.

What makes a good abstract in a research paper?

A good abstract in a research paper should effectively convey the study's purpose, methodology, results, and conclusion concisely and clearly. It should provide a quick overview of the essential information.

Can ChatGPT create abstracts for documents?

ChatGPT can assist in creating abstracts for documents by summarizing text-based content. However, it has a character limit, and for longer documents, it's recommended to use specialized AI tools designed for document summarization.

Is there a free online AI tool that generates abstracts for articles?

Yes, there are free online AI tools that generate abstracts for articles. HiPDF's AI Abstract Generator is one such tool that allows users to create abstracts for articles and other written materials.

What is the best AI abstract generator?

Determining the best AI abstract generator depends on specific needs and preferences. HiPDF's AI Abstract Generator, ChatGPT, and other tools like Sharly AI are among the popular choices, each with unique features.

Is there an AI abstract generator that can craft abstracts for scanned PDFs?

Certainly! For effective abstract generation from scanned PDFs, consider tools equipped with OCR (Optical Character Recognition) and summarization capabilities. PDFelement is a reliable option, utilizing OCR to extract text from scanned documents accurately and then using AI to analyze the PDF for abstract generation. This ensures precise and meaningful abstracts from your scanned PDFs.

More tips for AI Document Summarizer

AI PDF Reader: Summarize, Rewrite, Explain, and Ask PDF Online

Chat with PDF Online for Free Easily

Best AI Content Detector for Free

Top 8 AI PDF Readers 2023

10 Excellent AI PDF Summarizers To Use

AI PDF Summarizer: Summarize PDFs and Text Online Free

Effortlessly Summarize Articles with AI Online

Free Online AI Research Paper Summarizer

Free AI Text Summarizer: Instantly Summarize Any Text Online

Free pdf tools process pdf tasks online..

HiPDF Online Tools quality rating:

~3 min read

Revolutionize Your Lab Work with the Brand-New AI Abstract Generator Tool!

Mindgrasp recently released apa abstract generator.

published 1/10/2023 by Mindgrasp

Big names like Chegg, ChatGPT, and Quizlet have taken loads off of students’ backs for years. We know how painful it is watching peers breeze through their homework plugging in each question and getting neat answers and examples of work.

Finally, researchers’ calls have been answered with an abstract summary generator. The tool for simplifying the scientific writing process is here and it’s powered by Artificial Intelligence. AI has come a long way and it’s normal to be skeptical of the new technology. We challenge you to synthesize your next report faster than Mindgrasp’s automatic abstract maker. Using state-of-the-art tech you’re able to create an abstract by pasting long text from your APA report, other online abstracts, research sources, and notes right into the software. Doing this cuts down on the countless hours spent combing through your own lab jargon to simplify and write an abstract. If you haven’t saved hours of time on your writing, we are willing to bet you couldn’t write a better summary quicker. No more stressing over plagiarism! With an abstract generator tool, you can get completely original outputs and stay on the right side of academic integrity. The text output is written at a professional academic writing level so there are also no worries a professor wouldn’t take this abstract generator’s APA citing seriously. Try out the advanced tools of the future! In just a few moments, you can save hours of work on your next report.

WANT TO SAVE TIME READING LONG RESEARCH ARTICLES?

- Automated Note-Taking

- AI powered Q&A

- Abstract generator

- Quick Summarizer

- Start your 7-day free trial

Generate a Research Abstract from a Title

Wordblot has so many potential uses. Within academic writing, a common problem is generating the abstract. So give it a spin and enter a title to see if we can help you with an abstract.

- @WordblotAI

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2021 All rights reserved.

Knowledge Center

- 9 Ways to Get Over Writer's Block

Free AI Abstract Generator: Abstrazer

Abstrazer v-5.0.20240601, free online abstract maker.

| 🔝 | Sums up text with Top AI |

|---|---|

| 📌 | Detection of the most relevant geographical areas and towns in the text |

| 💪 | NelSenso.Net apps support text up to 32000 characters long. |

| 🌐 | 25 Supported Languages |

| 🌄 | Find the photos most relevant to your article or paper |

| 💲 | 100% Free |

| 🔒 | All the processed texts is not stored or shared with anyone. We value your privacy. |

| 📈 | Graphically discover the most salient points of a text |

| 💗 | Tone analysis of opinions |

| 📝 | online powerfull spell checker |

| 📐 | Select your preferred summary length |

What is Abstrazer?

What is the automatic summary of a text, which languages are supported by nelsenso.net apps, what kind of documents are supported by the nelsenso.net apps, can i specify the size of the documents obtained, is the size of the text to be summarised or edited unlimited, can i use the nelsenso.net apps for free.

Love the work you guys produce over there at nelsenso.net! - Marilyn Marylin 19/01/2024

Nice apps ks 21/03/2023

gooood! carlotta130 30/09/2022

Give us your opinion

Version 5.0 of the NelSenso.Net apps has been released with numerous improvements in the AI algorithms (entities detection and automatic morphological-grammatical analysis)

22:00pm - 23:00pm

New! Summazer not only highlights the most semantically relevant sentences, but also displays in bold those that are fundamental and underlines those that characterise the context or knowledge domain

New! Summazer now automatically detects the rule of five "W": Who, What, Where, When, Why

Clustezer, the online text-clustering app, now also supports Oriental languages: Arabic, Chinese, etc.

Summazer automatically detects the main subject matter of the processed text, improving the quality of the extracted summary.

What this handout is about

This handout provides definitions and examples of the two main types of abstracts: descriptive and informative. It also provides guidelines for constructing an abstract and general tips for you to keep in mind when drafting. Finally, it includes a few examples of abstracts broken down into their component parts.

What is an abstract?

An abstract is a self-contained, short, and powerful statement that describes a larger work. Components vary according to discipline. An abstract of a social science or scientific work may contain the scope, purpose, results, and contents of the work. An abstract of a humanities work may contain the thesis, background, and conclusion of the larger work. An abstract is not a review, nor does it evaluate the work being abstracted. While it contains key words found in the larger work, the abstract is an original document rather than an excerpted passage.

Why write an abstract?

You may write an abstract for various reasons. The two most important are selection and indexing. Abstracts allow readers who may be interested in a longer work to quickly decide whether it is worth their time to read it. Also, many online databases use abstracts to index larger works. Therefore, abstracts should contain keywords and phrases that allow for easy searching.

Say you are beginning a research project on how Brazilian newspapers helped Brazil’s ultra-liberal president Luiz Ignácio da Silva wrest power from the traditional, conservative power base. A good first place to start your research is to search Dissertation Abstracts International for all dissertations that deal with the interaction between newspapers and politics. “Newspapers and politics” returned 569 hits. A more selective search of “newspapers and Brazil” returned 22 hits. That is still a fair number of dissertations. Titles can sometimes help winnow the field, but many titles are not very descriptive. For example, one dissertation is titled “Rhetoric and Riot in Rio de Janeiro.” It is unclear from the title what this dissertation has to do with newspapers in Brazil. One option would be to download or order the entire dissertation on the chance that it might speak specifically to the topic. A better option is to read the abstract. In this case, the abstract reveals the main focus of the dissertation:

This dissertation examines the role of newspaper editors in the political turmoil and strife that characterized late First Empire Rio de Janeiro (1827-1831). Newspaper editors and their journals helped change the political culture of late First Empire Rio de Janeiro by involving the people in the discussion of state. This change in political culture is apparent in Emperor Pedro I’s gradual loss of control over the mechanisms of power. As the newspapers became more numerous and powerful, the Emperor lost his legitimacy in the eyes of the people. To explore the role of the newspapers in the political events of the late First Empire, this dissertation analyzes all available newspapers published in Rio de Janeiro from 1827 to 1831. Newspapers and their editors were leading forces in the effort to remove power from the hands of the ruling elite and place it under the control of the people. In the process, newspapers helped change how politics operated in the constitutional monarchy of Brazil.

From this abstract you now know that although the dissertation has nothing to do with modern Brazilian politics, it does cover the role of newspapers in changing traditional mechanisms of power. After reading the abstract, you can make an informed judgment about whether the dissertation would be worthwhile to read.

Besides selection, the other main purpose of the abstract is for indexing. Most article databases in the online catalog of the library enable you to search abstracts. This allows for quick retrieval by users and limits the extraneous items recalled by a “full-text” search. However, for an abstract to be useful in an online retrieval system, it must incorporate the key terms that a potential researcher would use to search. For example, if you search Dissertation Abstracts International using the keywords “France” “revolution” and “politics,” the search engine would search through all the abstracts in the database that included those three words. Without an abstract, the search engine would be forced to search titles, which, as we have seen, may not be fruitful, or else search the full text. It’s likely that a lot more than 60 dissertations have been written with those three words somewhere in the body of the entire work. By incorporating keywords into the abstract, the author emphasizes the central topics of the work and gives prospective readers enough information to make an informed judgment about the applicability of the work.

When do people write abstracts?

- when submitting articles to journals, especially online journals

- when applying for research grants

- when writing a book proposal

- when completing the Ph.D. dissertation or M.A. thesis

- when writing a proposal for a conference paper

- when writing a proposal for a book chapter

Most often, the author of the entire work (or prospective work) writes the abstract. However, there are professional abstracting services that hire writers to draft abstracts of other people’s work. In a work with multiple authors, the first author usually writes the abstract. Undergraduates are sometimes asked to draft abstracts of books/articles for classmates who have not read the larger work.

Types of abstracts

There are two types of abstracts: descriptive and informative. They have different aims, so as a consequence they have different components and styles. There is also a third type called critical, but it is rarely used. If you want to find out more about writing a critique or a review of a work, see the UNC Writing Center handout on writing a literature review . If you are unsure which type of abstract you should write, ask your instructor (if the abstract is for a class) or read other abstracts in your field or in the journal where you are submitting your article.

Descriptive abstracts

A descriptive abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgments about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract describes the work being abstracted. Some people consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short—100 words or less.

Informative abstracts

The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the writer presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the complete article/paper/book. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract (purpose, methods, scope) but also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is rarely more than 10% of the length of the entire work. In the case of a longer work, it may be much less.

Here are examples of a descriptive and an informative abstract of this handout on abstracts . Descriptive abstract: