The Writing Process

Definitions.

- Stages of the Writing Process

- Strategies for Good Writing

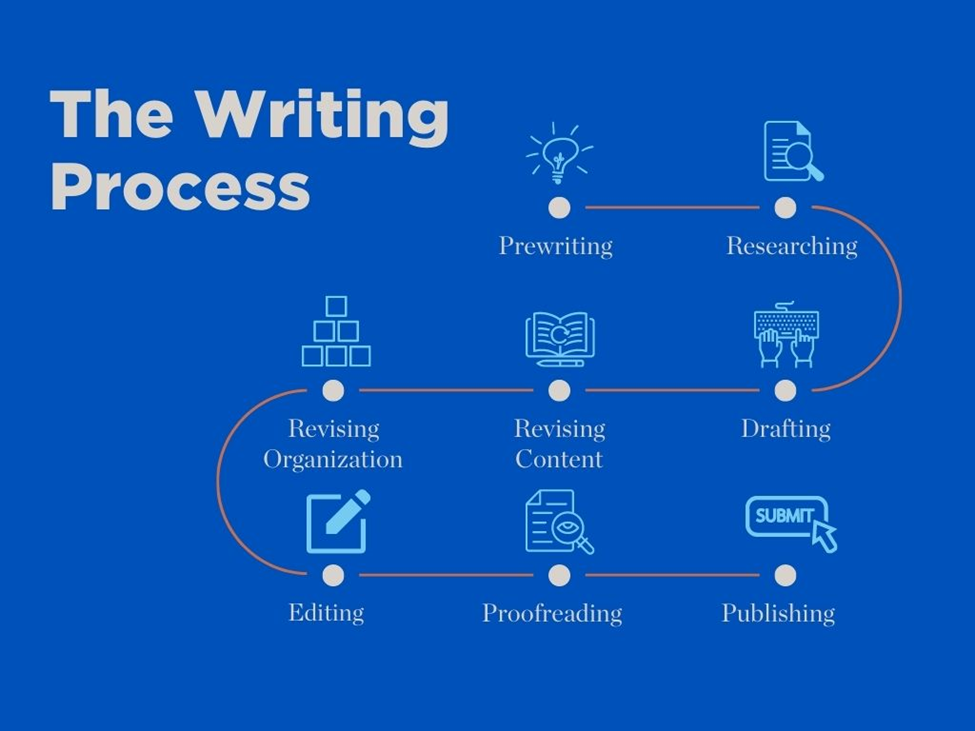

The Writing Process is a cycle of activities that you complete as you generate ideas, compose those ideas into a document or presentation, and refine those ideas. It is a recursive process, meaning that at any one stage in the process, you may find that you have to return to previous steps to review and refine your methods.

To read more about the elements of the Writing Process, we recommend the following resource:

- Dziak, M. (2018). Writing process (planning, drafting, revising, editing, publishing). Salem Press Encyclopedia. The writing process is the series of actions taken by writers to produce a finished work. Writers, educators, and theorists have defined the writing process in many different ways, but it generally involves prewriting tasks, writing tasks, and post-writing tasks. More specifically, these tasks include planning, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing, in approximately that order.

Benefits of following the Writing Process include:

- The ability to revisit previous work completed to find new ideas or refine existing ones.

- A more organized finished product.

- A less stressful experience, which is one cause of Writer's Block .

- Less time spent in the drafting stage.

- << Previous: Welcome

- Next: Stages of the Writing Process >>

- Last Updated: May 22, 2023 10:46 AM

- URL: https://library.tiffin.edu/writingprocess

- Sign Up for Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Resources for Writers: The Writing Process

Writing is a process that involves at least four distinct steps: prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing. It is known as a recursive process. While you are revising, you might have to return to the prewriting step to develop and expand your ideas.

- Prewriting is anything you do before you write a draft of your document. It includes thinking, taking notes, talking to others, brainstorming, outlining, and gathering information (e.g., interviewing people, researching in the library, assessing data).

- Although prewriting is the first activity you engage in, generating ideas is an activity that occurs throughout the writing process.

- Drafting occurs when you put your ideas into sentences and paragraphs. Here you concentrate upon explaining and supporting your ideas fully. Here you also begin to connect your ideas. Regardless of how much thinking and planning you do, the process of putting your ideas in words changes them; often the very words you select evoke additional ideas or implications.

- Don’t pay attention to such things as spelling at this stage.

- This draft tends to be writer-centered: it is you telling yourself what you know and think about the topic.

- Revision is the key to effective documents. Here you think more deeply about your readers’ needs and expectations. The document becomes reader-centered. How much support will each idea need to convince your readers? Which terms should be defined for these particular readers? Is your organization effective? Do readers need to know X before they can understand Y?

- At this stage you also refine your prose, making each sentence as concise and accurate as possible. Make connections between ideas explicit and clear.

- Check for such things as grammar, mechanics, and spelling. The last thing you should do before printing your document is to spell check it.

- Don’t edit your writing until the other steps in the writing process are complete.

- Enroll & Pay

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

The Writing Process

The writing process is something that no two people do the same way. There is no "right way" or "wrong way" to write. It can be a very messy and fluid process, and the following is only a representation of commonly used steps. Remember you can come to the Writing Center for assistance at any stage in this process.

Steps of the Writing Process

Step 1: Prewriting

Think and Decide

- Make sure you understand your assignment. See Research Papers or Essays

- Decide on a topic to write about. See Prewriting Strategies and Narrow your Topic

- Consider who will read your work. See Audience and Voice

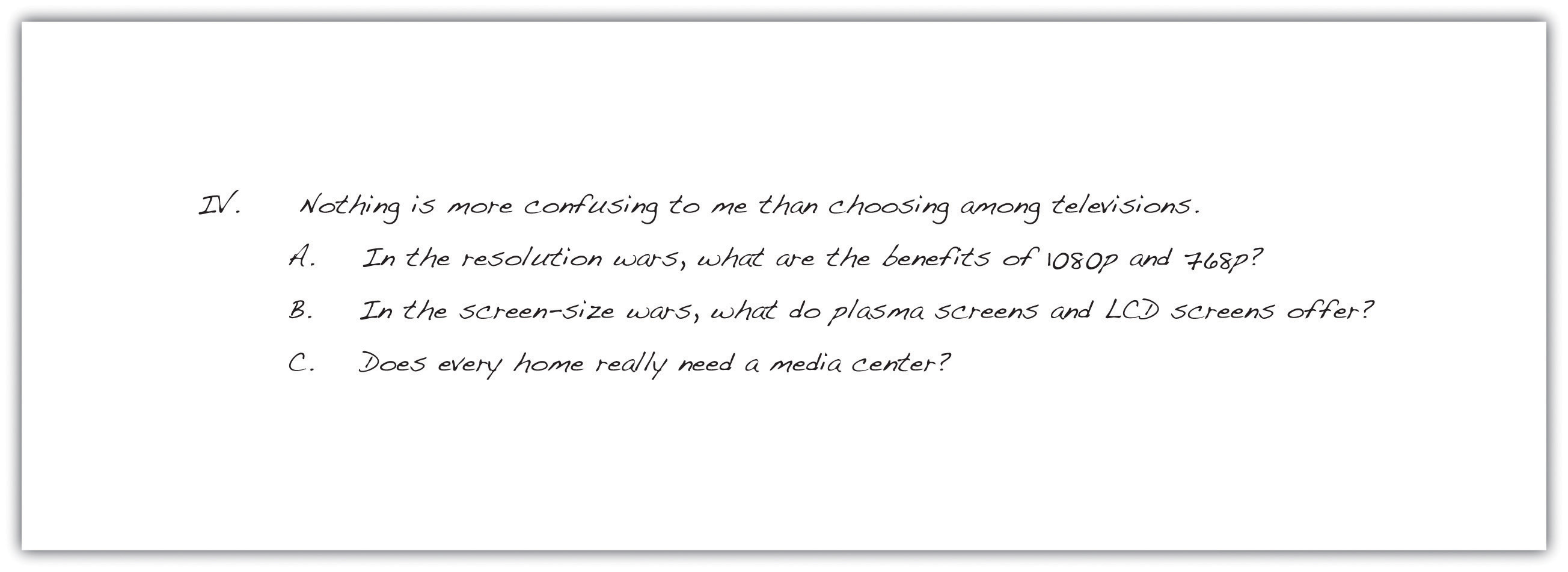

- Brainstorm ideas about the subject and how those ideas can be organized. Make an outline. See Outlines

Step 2: Research (if needed)

- List places where you can find information.

- Do your research. See the many KU Libraries resources and helpful guides

- Evaluate your sources. See Evaluating Sources and Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Make an outline to help organize your research. See Outlines

Step 3: Drafting

- Write sentences and paragraphs even if they are not perfect.

- Create a thesis statement with your main idea. See Thesis Statements

- Put the information you researched into your essay accurately without plagiarizing. Remember to include both in-text citations and a bibliographic page. See Incorporating References and Paraphrase and Summary

- Read what you have written and judge if it says what you mean. Write some more.

- Read it again.

- Write some more.

- Write until you have said everything you want to say about the topic.

Step 4: Revising

Make it Better

- Read what you have written again. See Revising Content and Revising Organization

- Rearrange words, sentences, or paragraphs into a clear and logical order.

- Take out or add parts.

- Do more research if you think you should.

- Replace overused or unclear words.

- Read your writing aloud to be sure it flows smoothly. Add transitions.

Step 5: Editing and Proofreading

Make it Correct

- Be sure all sentences are complete. See Editing and Proofreading

- Correct spelling, capitalization, and punctuation.

- Change words that are not used correctly or are unclear.

- APA Formatting

- Chicago Style Formatting

- MLA Formatting

- Have someone else check your work.

Do You Know The 7 Steps Of The Writing Process?

How much do you know about the different stages of the writing process? Even if you’ve been writing for years, your understanding of the processes of writing may be limited to writing, editing, and publishing.

It’s not your fault. Much of the writing instruction in school and online focus most heavily on those three critical steps.

Important as they are, though, there’s more to creating a successful book than those three. And as a writer, you need to know.

The 7 Steps of the Writing Process

Read on to familiarize yourself with the seven writing process steps most writers go through — at least to some extent. The more you know each step and its importance, the more you can do it justice before moving on to the next.

1. Planning or Prewriting

This is probably the most fun part of the writing process. Here’s where an idea leads to a brainstorm, which leads to an outline (or something like it).

Whether you’re a plotter, a pantser, or something in between, every writer has some idea of what they want to accomplish with their writing. This is the goal you want the final draft to meet.

With both fiction and nonfiction , every author needs to identify two things for each writing project:

- Intended audience = “For whom am I writing this?”

- Chosen purpose = “What do I want this piece of writing to accomplish?”

In other words, you start with the endpoint in mind. You look at your writing project the way your audience would. And you keep its purpose foremost at every step.

From planning, we move to the next fun stage.

2. Drafting (or Writing the First Draft)

There’s a reason we don’t just call this the “rough draft,” anymore. Every first draft is rough. And you’ll probably have more than one rough draft before you’re ready to publish.

For your first draft, you’ll be freewriting your way from beginning to end, drawing from your outline, or a list of main plot points, depending on your particular process.

To get to the finish line for this first draft, it helps to set word count goals for each day or each week and to set a deadline based on those word counts and an approximate idea of how long this writing project should be.

Seeing that deadline on your calendar can help keep you motivated to meet your daily and weekly targets. It also helps to reserve a specific time of day for writing.

Another useful tool is a Pomodoro timer, which you can set for 20-25 minute bursts with short breaks between them — until you reach your word count for the day.

3. Sharing Your First Draft

Once you’ve finished your first draft, it’s time to take a break from it. The next time you sit down to read through it, you’ll be more objective than you would be right after typing “The End” or logging the final word count.

It’s also time to let others see your baby, so they can provide feedback on what they like and what isn’t working for them.

You can find willing readers in a variety of places:

- Social media groups for writers

- Social media groups for readers of a particular genre

- Your email list (if you have one)

- Local and online writing groups and forums

This is where you’ll get a sense of whether your first draft is fulfilling its original purpose and whether it’s likely to appeal to its intended audience.

You’ll also get some feedback on whether you use certain words too often, as well as whether your writing is clear and enjoyable to read.

4. Evaluating Your Draft

Here’s where you do a full evaluation of your first draft, taking into account the feedback you’ve received, as well as what you’re noticing as you read through it. You’ll mark any mistakes with grammar or mechanics.

And you’ll look for the answer to important questions:

- Is this piece of writing effective/ Does it fulfill its purpose?

- Do my readers like my main character? (Fiction)

- Does the story make sense and satisfy the reader? (Fiction)

- Does it answer the questions presented at the beginning? ( Nonfiction )

- Is it written in a way the intended audience can understand and enjoy?

Once you’ve thoroughly evaluated your work, you can move on to the revision stage and create the next draft.

More Related Articles

How To Create An Em Dash Or Hyphen

Are You Ready To Test Your Proofreading Skills?

How To Write A Book For Kindle About Your Expertise Or Passion

5. Revising Your Content

Revising and editing get mixed up a lot, but they’re not the same thing.

With revising, you’re making changes to the content based on the feedback you’ve received and on your own evaluation of the previous draft.

- To correct structural problems in your book or story

- To find loose ends and tie them up (Fiction)

- To correct unhelpful deviations from genre norms (Fiction)

- To add or remove content to improve flow and/or usefulness

You revise your draft to create a new one that comes closer to achieving your original goals for it. Your newest revision is your newest draft.

If you’re hiring a professional editor for the next step, you’ll likely be doing more revision after they’ve provided their own feedback on the draft you send them.

Editing is about eliminating errors in your (revised) content that can affect its accuracy, clarity, and readability.

By the time editing is done, your writing should be free of the following:

- Grammatical errors

- Punctuation/mechanical and spelling errors

- Misquoted content

- Missing (necessary) citations and source info

- Factual errors

- Awkward phrasing

- Unnecessary repetition

Good editing makes your work easier and more enjoyable to read. A well-edited book is less likely to get negative reviews titled, “Needs editing.” And when it comes to books, it’s best to go beyond self-editing and find a skilled professional.

A competent editor will be more objective about your work and is more likely to catch mistakes you don’t see because your eyes have learned to compensate for them.

7. Publishing Your Final Product

Here’s where you take your final draft — the final product of all the previous steps — and prepare it for publication.

Not only will it need to be formatted (for ebook, print, and audiobook), but you’ll also need a cover that will appeal to your intended audience as much as your content will.

Whether you budget for these things or not depends on the path you choose to publish your book:

- Traditional Publishing — where the publishing house provides editing, formatting, and cover design, as well as some marketing

- Self-Publishing — where you contract with professionals and pay for editing, formatting, and cover design.

- Self-Publishing with a Publishing Company — where you pay the company to provide editing, formatting, and cover design using their in-house professionals.

And once your book is live and ready to buy, it’s time to make it more visible to your intended audience. Otherwise, it would fail in its purpose, too.

Are you ready to begin 7 steps of the writing process?

Now that you’re familiar with the writing process examples in this post, how do you envision your own process?

While it should include the seven steps described here, it’ll also include personal preferences of your own — like the following:

- Writing music and other ambient details

- Writing schedule

- Word count targets and time frames

The more you learn about the finer details of the writing process, the more likely you are to create content your readers will love. And the more likely they are to find it.

Wherever you are in the process, our goal here is to provide content that will help you make the most of it.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency.

- Collaboration

Information Literacy

Writing process, the writing process – research on composing.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about their work. They've found that the writing process can be seen in three main ways: (1) a series of steps or stages ; (2) a cognitive, problem-solving activity ; and (3) a creative, intuitive, organic, dialogic process that writers manage by listening to their inner speech and following their felt sense . Learn about scholarship on the writing process so you can understand how to break through writing blocks and find fluency as a writer, researcher, and thought leader.

Synonymous Terms

Composing process.

In writing studies , the writing process may also be known as the composing process . This may be due to the dramatic influence of Janet Emig’s (1971) dissertation, The Composing Processes of Twelfth Graders . Emig’s research employed think-aloud protocols and case-study methods to explore the composing processes of high school students.

Creative Process

In creative writing and literature, the writing process may be known as the creative process .

In the arts and humanities the term creative process is reserved for artistic works, such as paintings, sculptures, performance art, films, and works of literature.

Related Concepts

Composition Studies ; Creativity; Felt Sense ; Growth Mindset ; Habits of Mind ; Intellectual Openness ; Professionalism and Work Ethic ; Resilience ; Self Regulation & Metacognition

What is the Writing Process?

Research on composing processes conducted over the past 60 years has led to three major distinct ways of defining and conceptualizing the writing process:

- prewriting , invention , research , collaboration , planning , designing , drafting , rereading , organizing , revising , editing , proofreading , and sharing or publishing

- The writing process refers to cognitive, problem-solving strategies

- The writing process refers to the act of making composing decisions based on nonrational factors such as embodied knowledge , felt sense , inner speech, and intuition.

1. The writing process refers to writing process steps

The writing process is often characterized as a series of steps or stages. During the elementary and middle-school years, teachers define the writing process simply as prewriting , drafting , revising , and editing . Later, in high-school and college, as writing assignments become more challenging, teachers introduce additional writing steps: invention , research , collaboration , designing , organizing , proofreading , and sharing or proofreading.

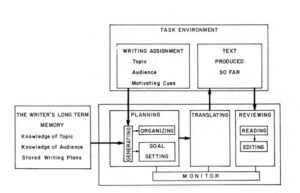

2. The writing process refers to Problem-Solving Strategies

As an alternative to imagining the writing process to be a series of steps or stages that writers work through in linear manner, Linda Flower and John Hayes suggested in 1977 that writing should be thought of as a “thinking problem,” a “problem-solving process,” a “cognitive problem solving process,” or a “goal-directed thinking process.”

3. The writing process refers to the act of making composing decisions based on flow, felt sense and other elements of embodied knowledge

For some writers, viewing the writing process as a series of steps or problems feels to mechanistic, impersonal and formulaic. Rather than view that the writing process to be a series of writing steps or problem solving strategies , Sondra Perl , an English professor, suggests that composing is largely a process of listening to one’s felt sense — one’s “bodily awareness of a situation or person or event:

“A felt sense doesn’t come to you in the form of thoughts or words or other separate units, but as a single (though often puzzling and very complex) bodily feeling”. (Gendlin 1981, 32-33)

What are Writing Process Steps?

In elementary and middle schools in the U.S., the writing process is often simplified and presented at four or five key steps: prewriting , writing , revising , and editing –and sometimes and publishing or sharing . As students progress through school, the writing process is presented in increasingly complex ways. By high school, teachers present “the writing process steps” as

- Proofreading

- Sharing – Publishing

Is there one perfect way to work with the writing process?

People experience and define the writing process differently, according to their historical period, literacy history, knowledge of writing tools, media , genres — and more. One of the takeaways from research on composing is that we’ve learned writers develop their own idiosyncratic approaches to getting the work done. When it comes to how we all develop, research , and communicate information , we are all special snowflakes. For example,

- Hemingway was known for standing while he wrote at first light each morning.

- Truman Capote described himself as a “completely horizontal author.” He wrote lying down, in bed or on a couch, with a cigarette and coffee handy.

- Hunter S. Thompson wrote through the nights, mixing drinking and partying with composing

- J.K. Rowling tracked the plot lines for her Harry Potter novels in a data.

- Maya Angelou would lock herself away in a hotel room from 6:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. so she has no distractions.

Furthermore, the steps of the writing process a writer engages in vary from project to project. At times composing may be fairly simple. Some situations require little planning , research , revising or editing , such as

- a grocery list, a to-do list, a reflection on the day’s activity in a journal

- documents you routinely write, such as the professor’s letter of recommendation, a bosses’ performance appraisal, a ground-water engineer’s contamination report.

Over time, writers develop their own unique writing processes. Through trial and error, people can learn what works for them.

Composing may be especially challenging

- when you are unfamiliar with the topic , genre , medium , discourse community

- when the thesis/research question/topic is complicated yet needs to be explained simply

- when you are endeavoring to synthesize other’s ideas and research

- when you don’t have the time you need to perfect the document.

What are the main factors that affect how writers compose documents?

Writers adjust their writing process in response to

- Writers assess the importance of the exigency, the call to write, before commiting time and resources to launching

- the writers access to information

- What they know about the canon, genre, media and rhetorical reasoning

- their writerly background

- the audience

- Writers assess the importance of the exigency, the call to write, before committing time and resources to working on the project.

Why does the writing process matter?

The writing processes that you use to compose documents play a significant role in determining whether your communications are successful. If you truncate your writing process, you are likely to run out of the time you need to write with clarity and authority .

- Studying the writing processes of successful writers can introduce you to new rhetorical moves, genres , and composing processes. Learning about the composing processes of experienced writers can help you learn how to adjust your rhetorical stance and your writing styles to best accomplish your purpose .

- By examining your writing processes and the writing processes of others, you can learn how to better manage your work and the work of other authors and teams.

- By recognizing that writing is a skill that can be developed through practice and effort, you can become more resilient and adaptable in your writing endeavors.

Do experienced writers compose in different ways than inexperienced writers?

Yes. Experienced writers engage in more substantive, robust writing processes than less experienced writers.

- Experienced writers tend to have more rhetorical knowledge and a better understanding of composing steps and strategies than inexperienced writers.

- Experienced writers tend to be more willing than inexperienced writers to make substantive changes in a draft, often making changes that involve rethinking the meaning of a text. Some professional writers may revise a document hundreds of times before pushing send or publishing it.

- Experienced writers engage in revision as an act of internal conversation, a form of inner speech that they have with themselves and an imagined other–the internalized target audience. In contrast, inexperienced writers tend to confuse editing for revision . They tend to make only a few edits to their initial drafts, focusing primarily on surface-level changes such as correcting grammar, spelling, or punctuation errors.

- Experienced writers are adept at working collaboratively, leveraging the strengths of team members and effectively coordinating efforts to produce a cohesive final product. Inexperienced writers may struggle with collaboration, communication, and division of labor within a writing team

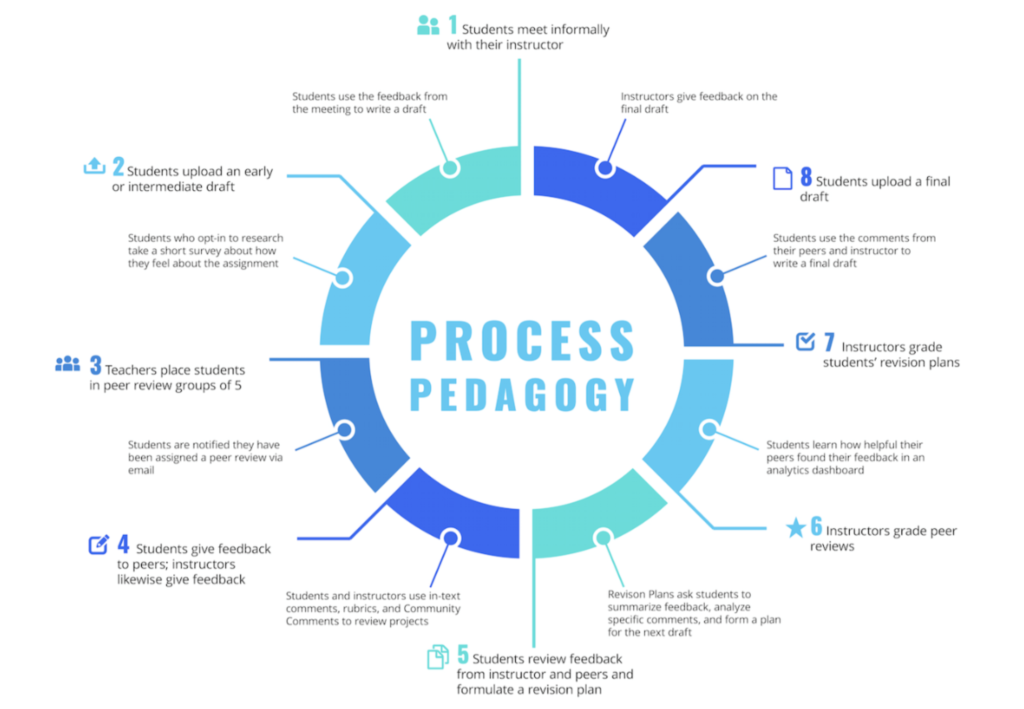

What is Process Pedagogy?

Process pedagogy, which is also known as the process movement, emerged in the United States during the late 1960s and early 1970s. In The Making of Knowledge in Composition , Steve North (1987) links the emergence of process pedagogy to

- Sputnik and America’s concern it was falling behind Russia

- the GI Bill and the changing demographics of undergraduate students in the post-war era.

Additionally, process pedagogy emerged in response to dissatisfaction with traditional, product-oriented approaches to teaching writing. In the current-traditional paradigm of writing, the focus of the classroom was on “the composed product rather than the composing process; the analysis of discourse into words, sentences, and paragraphs; the classification of discourse into description, narration, exposition, and argument; the strong concern with usage (syntax, spelling, punctuation) and with style (economy, clarity, emphasis)” (Young, 1978, p. 25).

The process movement reflected a sea change on the part of middle schools, high schools, and universities in the U.S. Traditionally, classroom instruction focused on analysis and critique of the great works of literature: “The student is (a) exposed to the formal descriptive categories of rhetoric (modes of argument –definition, cause and effect, etc. — and modes of discourse — description, persuasion, etc.), (b) offered good examples (usually professional ones) and bad examples (usually his/her own) and (c) encouraged to absorb the features of a socially approved style, with emphasis on grammar and usage. We help our students analyze the product, but we leave the process of writing up to inspiration” (Flower and Hayes, 1977, p. 449).

In contrast to putting the focus of class time on analyzing great literary works, the canon , process pedagogy calls for teachers to put the emphasis on the students’ writing:

- Students need help with prewriting , invention , research , collaboration , writing , designing , revising , organizing , editing , proofreading , and sharing

- Teachers do not comment on grammar and style matters in early drafts. Instead, they focus on global perspectives . They prioritize the flow of ideas and expression over correctness in grammar and mechanics.

- Students engage in prewriting and invention exercises to discover and develop new ideas

- Students repeatedly revise their works in response to self-critique , peer review , and critiques from teachers

- Teachers should provide constructive feedback throughout the writing process.

What does “teach the process and not the product mean”?

“Teach the process not the product ” is both the title of a Donald Murray (1972) article and the mantra of the writing process movement, which emerged during the 1960s.

The mantra to teach the process not the product emerged in response to the research and scholarship conducted by Donald Murray, Janet Emig, Peter Elbow, Ann Berthoff, Nancy Sommers, Sondra Perl, John Hayes and Linda Flower.

What does it mean to describe the writing process as recursive ?

The term recursive writing process simply means that writers jump around from one activity to another when composing . For instance, when first drafting a document, a writer may pause to reread something she wrote. That might trigger a new idea that shoots her back to Google Scholar or some other database suitable for strategic searching .

How do researchers study the writing process?

The writing process is a major subject of study of researchers and scholars in the fields of composition studies , communication, writing studies , and AI (artificial intelligence).

The writing process is something of a black box: investigators can see inputs (e.g., time on task) or outputs (e.g., written discourse ), yet they cannot empirically observe the internal workings of the writer’s mind. At the end of the day investigators have to jump from what they observe to making informed guesses about what is really going on in the writer. Even if investigators ask a writer to talk out loud about what they are thinking as they compose , the investigators can only hear what the writer is saying: they cannot see the internal machinations associated with the writer’s thoughts. If a writer goes mute, freezes, and just stares blankly at the computer screen, investigators cannot really know what’s going on. They can only speculate about how the brain functions.

Research Methods

To study or theorize about the writing process, investigators may use a variety of research methods .

Doherty, M. (2016, September 4). 10 things you need to know about banyan trees. Under the Banyan. https://underthebanyan.blog/2016/09/04/10-things-you-need-to-know-about-banyan-trees/

Emig, J. (1967). On teaching composition: Some hypotheses as definitions. Research in The Teaching of English, 1(2), 127-135. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED022783.pdf

Emig, J. (1971). The composing processes of twelfth graders (Research Report No. 13). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Emig, J. (1983). The web of meaning: Essays on writing, teaching, learning and thinking. Upper Montclair, NJ: Boynton/Cook Publishers, Inc.

Ghiselin, B. (Ed.). (1985). The Creative Process: Reflections on the Invention in the Arts and Sciences . University of California Press.

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. (1980). Identifying the Organization of Writing Processes. In L. W. Gregg, & E. R. Steinberg (Eds.), Cognitive Processes in Writing: An Interdisciplinary Approach (pp. 3-30). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hayes, J. R. (2012). Modeling and remodeling writing. Written Communication, 29(3), 369-388. https://doi: 10.1177/0741088312451260

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. S. (1986). Writing research and the writer. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1106-1113. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1106

Leijten, Van Waes, L., Schriver, K., & Hayes, J. R. (2014). Writing in the workplace: Constructing documents using multiple digital sources. Journal of Writing Research, 5(3), 285–337. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2014.05.03.3

Lundstrom, K., Babcock, R. D., & McAlister, K. (2023). Collaboration in writing: Examining the role of experience in successful team writing projects. Journal of Writing Research, 15(1), 89-115. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2023.15.01.05

National Research Council. (2012). Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.https://doi.org/10.17226/13398.

North, S. M. (1987). The making of knowledge in composition: Portrait of an emerging field. Boynton/Cook Publishers.

Murray, Donald M. (1980). Writing as process: How writing finds its own meaning. In Timothy R. Donovan & Ben McClelland (Eds.), Eight approaches to teaching composition (pp. 3–20). National Council of Teachers of English.

Murray, Donald M. (1972). “Teach Writing as a Process Not Product.” The Leaflet, 11-14

Perry, S. K. (1996). When time stops: How creative writers experience entry into the flow state (Order No. 9805789). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304288035). https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/when-time-stops-how-creative-writers-experience/docview/304288035/se-2

Rohman, D.G., & Wlecke, A. O. (1964). Pre-writing: The construction and application of models for concept formation in writing (Cooperative Research Project No. 2174). East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University.

Rohman, D. G., & Wlecke, A. O. (1975). Pre-writing: The construction and application of models for concept formation in writing (Cooperative Research Project No. 2174). U.S. Office of Education, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Sommers, N. (1980). Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers. College Composition and Communication, 31(4), 378-388. doi: 10.2307/356600

Vygotsky, L. (1962). Thought and language. (E. Hanfmann & G. Vakar, Eds.). MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/11193-000

Related Articles:

Discovering Your Unique Writing Process: A Guide to Self-Reflection

Problem-Solving Strategies for Writers: a Review of Research

The 7 Habits of Mind & The Writing Process

The Secret, Hidden Writing Process: How to Tap Your Creative Potential

The Ultimate Blueprint: A Research-Driven Deep Dive into The 13 Steps of the Writing Process

Suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Joseph M. Moxley

Understanding your writing process is a crucial aspect of developing as a writer. For both students and professional writers, reflection on the process of writing can lead to more effective...

Traditionally, in U.S. classrooms, the writing process is depicted as a series of linear steps (e.g., prewriting, writing, revising, and editing). However, since the 1980s the writing process has also...

In contrast to the prevailing view that the writing process refers to writing steps or problem solving strategies, a third view is that the writing process involves nonrational factors, such...

This article provides a comprehensive, research-based introduction to the major steps, or strategies, that writers work through as they endeavor to communicate with audiences. Since the 1960s, the writing process has...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.2: Defining the Writing Process

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 22467

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

People often think of writing in terms of its end product—the email, the report, the memo, essay, or research paper, all of which result from the time and effort spent in the act of writing. In this course, however, you will be introduced to writing as the recursive process of planning, drafting, and revising.

Writing is Recursive

You will focus as much on the process of writing as you will on its end product (the writing you normally submit for feedback or a grade). Recursive means circling back; and, more often than not, the writing process will have you running in circles. You might be in the middle of your draft when you realize you need to do more brainstorming, so you return to the planning stage. Even when you have finished a draft, you may find changes you want to make to an introduction. In truth, every writer must develop his or her own process for getting the writing done, but there are some basic strategies and techniques you can adapt to make your work a little easier, more fulfilling and effective.

Developing Your Writing Process

The final product of a piece of writing is undeniably important, but the emphasis of this course is on developing a writing process that works for you. Some of you may already know what strategies and techniques assist you in your writing. You may already be familiar with prewriting techniques, such as freewriting, clustering, and listing. You may already have a regular writing practice. But the rest of you may need to discover what works through trial and error. Developing individual strategies and techniques that promote painless and compelling writing can take some time. So, be patient.

A Writer’s Process: Ali Hale

Read and examine The Writing Process by Ali Hale. Think of this document as a framework for defining the process in distinct stages: Prewriting, Writing, Revising, Editing, and Publishing. You may already be familiar with these terms. You may recall from past experiences that some resources refer to prewriting as planning and some texts refer to writing as drafting.

What is important to grasp early on is that the act of writing is more than sitting down and writing something. Please avoid the “one and done” attitude, something instructors see all too often in undergraduate writing courses. Use Hale’s essay as your starting point for defining your own process.

A Writer’s Process: Anne Lamott

In the video below, Anne Lamott, a writer of both non-fiction and fiction works, as well as the instructional novel on writing Bird by Bird: Instructions on Writing , discusses her own journey as a writer, including the obstacles she has to overcome every time she sits down to begin her creative process. She will refer to terms such as “the down draft,” “the up draft,” and “the dental draft.”

As you watch, think about how her terms, “down draft,” “up draft,” “dental draft,” work with those presented by Hale’s The Writing Process . What does Lamott mean by these terms? Can you identify with her process or with the one Hale describes? How are they related?

Also, when viewing the interview, pay careful attention to the following timeframe: 11:23 to 27:27 minutes and make a list of tips and strategies you find particularly helpful. Think about how your own writing process fits with what Hale and Lamott have to say. Is yours similar? Different? Is there any new information you have learned that you did not know before exposure to these works?

A YouTube element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: http://pb.libretexts.org/temp/?p=1387

- Skip to right header navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

The Writing Process Explained: From Outline to Final Draft

May 30, 2023 // by Lindsay Ann // Leave a Comment

Sharing is caring!

Writing is a messy process. Rarely do writers pick up their pen or open a fresh Google Doc and write everything start to finish. To take the genesis of an idea, consider the rhetorical situation, form that idea into whatever genre and format it needs to take, polish it, and then publish it requires a writing process to help make the non-linear process of writing more manageable and productive.

Student writers often struggle with this process. They think one submitted draft means the writing process is complete. The lack of engagement in the writing process can hold a student’s writing in that rough draft limbo land forever.

Empowering students to have agency in their own writing process can inspire amazing writing, increase engagement, and improve students’ metacognition.

Writing Process 5 Steps

The writing process as we know it has 5 distinct stages.

- Prewriting, research & planning: In this stage, the writer is mapping out the writing.

This may include brainstorming ideas, storyboarding the narrative arc, conducting any necessary research and making an outline. Anything that happens before actually writing is considered prewriting.

- Drafting: In the drafting stage, writers are making their first attempt at getting the words on the page. In this stage the writing isn’t expected to be perfect because the writer will eventually go back and make necessary changes. The goal in this stage is simply to get the ideas on paper. The drafting stage tends to be where student writers think the writing process ends. For many reasons, they lack the understanding that this is a first attempt and will require some finessing.

But writing is definitely not done here.

- Revising: When revising, writers go back into their draft and make changes for content .

This looks like reordering sentences, adding sentences, deleting sentences altogether, reordering paragraphs, etc.

In this stage, writers are really ripping their drafts to shreds, taking out what isn’t working and replacing it with more beautiful and functional content in order to better get their message across and accomplish the purpose of their piece.

- Editing & proofreading: During the editing and proofreading phase, writers are carefully combing through the piece to make sure everything is correct . Word choice, sentence structure, rhythm, punctuation, clarity…getting all of it right matters.

Sometimes in this stage it’s helpful to have an extra set of eyes on the draft because it can be difficult for us to always spot errors in our own writing.

- Publishing: Publishing can look very different for every writer. In a classroom, publishing may just mean, I’m finished and I’m going to turn this into my teacher now and she’s going to post it on the class Padlet . It could also mean sharing it with a collaborative writing group or submitting to the school’s literary magazine. It could also mean pitching the piece to a publication or presenting it to a community group. Basically, in this step, the writer is ready to show off their writing to the world.

Teaching the Writing Process

Students need explicit instruction and time to practice the writing process. Time of course is one of our most precious resources in the classroom, so how can we make the most efficient use of it when teaching the writing process?

Here’s what I’ve found to be particularly helpful:

Use the language of the writing process: Be intentional about using the language of the writing process in your daily agendas, lessons, and feedback. This way when you tell a student something like, “Today you need to focus on prewriting for your upcoming argumentative essay” or “This writing project needs some more revision” or “Do you have your draft completed?” they know what stage of the writing process they’re in and what they need to be doing in that stage of the process.

Teaching writing as a recursive process: The writing process is recursive.

We (and by we I just mean all of us writers out there) can bounce back and forth from the drafting to the revision stage 15 times before moving on. We can also engage in deep and thoughtful prewriting only to abandon the idea before ever drafting because a better one came along and we decided to start prewriting and drafting for that idea.

Breaking students of their bad habits is tough work, but helping students see writing as a recursive process will strengthen their final products and help them gain overall confidence in their writing.

Write daily : Again, I know there are just not enough minutes in the day, but making writing a daily habit is so important.

The writing process doesn’t just have to be used for long-form writing.

If you use a daily quickwrite, journal prompt, or warmup, have students cycle through the writing process by jotting down a few ideas and making a quick outline before writing, writing, and then revising and editing before turning in or sharing with a shoulder partner.

By being in the habit of writing every day, students will find their groove with their own process for writing and it will become second nature!

Model for students your process: Writing in front of students is Vulnerable (yes, with a capital V). I like writing and even I sometimes get nervous before putting my notebook under the document camera. But I try to make writing in front of my students something I do at least once weekly. I model for them my process, I think aloud what I’m going to write, how I want to write it, and they get to watch me write something, hate it, revise it, and cycle through the writing process.

Status of the class for managing it all: Connor may need three days to organize his ideas in the prewriting stage while Ava only needs about 5 minutes to plan her writing and hit the ground running.

There is no time limit for being in a particular stage of the writing process (unless ya know, they’ve got their phone propped up behind their Chromebook watching Euphoria instead of writing, then we’ve got problems. But I digress…).

Despite that knee jerk reaction to herd our students like cattle through the writing process, it needs to be differentiated for each writer in the room.

So how the heck do you manage that?

Utilizing a status of the class for the writing process helps you keep track of where each writer in the room is and can also help you better plan small group or individual instruction and coaching.

If you just do a quick Google search for the status of the class in the writing workshop, you’ll see approximately one million great ways to do it, but I particularly like the visual Stacy Shubitz at Two Writing Teachers created for her classroom.

Ideas for Brainstorming and Initiation

Check out these ideas to get students engaged in the writing process and shorten the time they stare at a blank page:

- Storyboarding: Draw out problems and solutions and organize them in a logical order.

- Alphabet boxes: See if you can come up with one idea for each letter of the alphabet.

- Heart Maps : Can be used for all writing genres!

- Keeping a writer’s notebook: Have all of your brilliant ideas living in one place. When a new one comes along, jot it down in the notebook!

- Pomodoro technique: Set a timer for 25 minutes and write. When the timer goes off, take a 5 minute break, reset the timer for 25 minutes, and continue writing.

- Stream of consciousness: Write whatever comes to mind about your spark of an idea for writing. When you’ve written all you have to say, use a reverse outline to organize your ideas and continue drafting or begin revising.

Writing Process Stages

Break assignment up for students: Depending on your students’ skill levels, they may need you to break the assignment up into the stages of the writing process and assign one stage at a time.

Design cycle for STEM and PBL: The writing process is similar to the design cycle used for STEM and PBL ( yes, even engineers need to understand the writing process!).

Have students create their own goals and workflow calendar: In her book Project Based Writing , Liz Prather shares how she has students establish goals for their writing as part of the prewriting process as well as develop their own calendars using a reverse engineering process.

For example, if a student has 25 days and intends to create a poem about the changing seasons, they will need to break down the project into individual tasks and then map out on their calendar how many days they will need for each task.

Wouldn’t it be amazing if by the end of the year students could move 100% autonomously through the writing process?!

Writing Process Revising v. Editing

What is the difference between revising and editing in the writing process?

Revising focuses on content only. When you are revising your draft you may notice you are missing a comma or misspelled a word. That’s great! But in the revising stage, those observations don’t matter. Instead, you’re only focusing on making your mystery narrative more suspenseful or making your satirical article more humorous.

In the editing stage is when you address those spelling, grammar, and mechanics errors.

Oftentimes in the classroom, the editing phase of the writing process is merely relegated to peer editing, which usually looks like a student’s paper getting shipped off to another student and being told to magically edit it without any guidance.

Peer editing often gets a bad rap, but I have found that peer editing does have some redeeming qualities if explicitly taught and done correctly .

Other Misconceptions

Sometimes misconceptions about the writing process hold us back from being our best possible teacher selves and hold our writers back from being their best possible writing selves. So as we wrap up, let’s debunk some of these common misconceptions.

- Only writers who have problems in their writing need feedback: Ummmmm noooo. Even Jodi Piccoult has a literary agent and a team of editors at her publishing house to make sure her writing is perfect before being published. If it’s good enough for the New York Times bestselling author, it’s good enough for all of us.

- Every piece of writing needs to go through the full cycle: While it would be totally ideal to take every possible idea we ever have for a writing project and then brainstorm it, research it, outline it, draft, revise, edit, and then hit publish, that’s not really realistic. It’s okay to give up on a piece, change your mind on your idea, or have 6 drafts before it’s ready to be edited!

- You need to use the same process each time: The writing process is intended to be flexible.

Now listen, I fully believe students have to learn the rules of writing (writing process included!) before they can learn to break them. But each student’s process doesn’t have to be the same.

If someone in your classroom needs to fully brainstorm each writing assignment using a storyboard before writing and you have another who needs to write a stream of consciousness before getting organized, it’s all good! Allow students to find their own way in the writing process. That’s where the really good, authentic writing lives!

About Lindsay Ann

Lindsay has been teaching high school English in the burbs of Chicago for 19 years. She is passionate about helping English teachers find balance in their lives and teaching practice through practical feedback strategies and student-led learning strategies. She also geeks out about literary analysis, inquiry-based learning, and classroom technology integration. When Lindsay is not teaching, she enjoys playing with her two kids, running, and getting lost in a good book.

Related Posts

You may be interested in these posts from the same category.

10 Most Effective Teaching Strategies for English Teachers

Beyond Persuasion: Unlocking the Nuances of the AP Lang Argument Essay

Book List: Nonfiction Texts to Engage High School Students

12 Tips for Generating Writing Prompts for Writing Using AI

31 Informational Texts for High School Students

Project Based Learning: Unlocking Creativity and Collaboration

Empathy and Understanding: How the TED Talk on the Danger of a Single Story Reshapes Perspectives

Teaching Story Elements to Improve Storytelling

Figurative Language Examples We Can All Learn From

18 Ways to Encourage Growth Mindset Versus Fixed Mindset in High School Classrooms

10 Song Analysis Lessons for Teachers

Must-Have Table Topics Conversation Starters

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

The writing process, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

Introduction

Every writer, whether inexperienced or seasoned, knows that the process can be overwhelming. Whether you are analyzing, reporting, or composing a poem for your creative writing class, writing demands that you expose your innermost thoughts to the scrutiny of others. While you write, concentrating on the writing process, rather than what others will think, can give you the confidence to focus on the task at hand. Although every writer’s process is unique, it usually involves a combination of 1) planning and prewriting, 2) writing, and 3) rewriting/revising.

The Big Picture

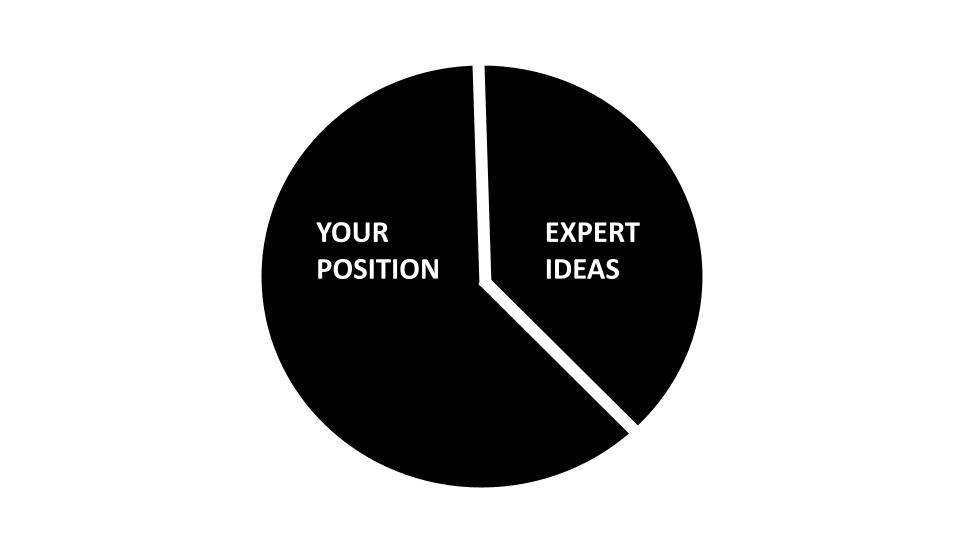

The prewriting and planning phase begins with an understanding of the big picture. If you are new to academic writing, it might be helpful to think about academic writing in a simple way; there are usually three parts:

1) Your position on the topic (prior, current, and future knowledge on the topic)

2) Expert ideas (formal research)

3) A union of those two

Why this balance?

Neither excessive emphasis on your own ideas nor too much information from outside research will lead to well-balanced writing. While expectations are different in every discipline and class, and you should always ask your professor what is preferred, your writing should include mostly your ideas, in a formal tone, with scholarly research that supports and supplements your argument. In other words, your voice carries the argument and flow of any written piece.

Keeping the big picture in mind as you dive into the phases ahead will result in a smoother writing process, while hopefully reaching the main goals of any writing assignment: engaging meaningfully with your topic, demonstrating your knowledge, and educating your audience.

Planning and Prewriting

The purpose of the planning and prewriting phase is to explore your topic from different angles, connect to your own thoughts about the topic, come upon new ideas, and identify new relationships between concepts. When planning and prewriting, you will (click on the arrows):

Study your assignment expectations or writing prompt closely.

Brainstorm your own ideas on the chosen topic., conduct casual research to familiarize yourself with the topic., add these thoughts to a prewriting strategy., add formal research and notes to your chosen prewriting strategy., writing and rewriting.

Writing and rewriting phases allow you to implement your planning and the results of your experimentation while prewriting. You implement your strategy, working out the details and fine-tuning your thoughts. In the rewriting , or revising, phase, you review what you have written and consider how and where your writing can be improved.

It’s important to remember that there is no such thing as a perfect writing process, and you can always edit and polish your thoughts later. Being passionate about your chosen topic can also help motivate you to get started. Write. Generate ideas. Revise later. Try to have fun with it!

Key Takeaways

Planning/prewriting, writing, and revising help organize and guide your writing process.

Academic writing consists of 1) your ideas 2) expert ideas 3) connections between the two.

The writing process is unique to each individual and need not necessarily follow a strict order.

The overall goal in writing is to engage in the pursuit of knowledge so you can share it with others.

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction

Critical Strategies and Writing

Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis

Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation

Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion

Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis

Developing a Paper Using Strategies

Kinds of Assignments You Will Write

Patterns for Presenting Information

Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques

Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data

Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts

Supporting with Research and Examples

Writing Essay Examinations

Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete

Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing

Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question

Chapter 4: The Research Process

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources

Research Resources: What Are Research Resources?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources

Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure

Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure

The Nature of Research

The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated?

The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed?

The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research?

Chapter 5: Academic Integrity

Academic Integrity

Giving Credit to Sources

Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws

Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation

Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides

Integrating Sources

Practicing Academic Integrity

Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources

Types of Documentation

Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists

Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style

Types of Documentation: Note Citations

Chapter 6: Using Library Resources

Finding Library Resources

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing

How Is Writing Graded?

How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool

The Draft Stage

The Draft Stage: The First Draft

The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft

The Draft Stage: Using Feedback

The Research Stage

Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing

Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers

Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure

Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument

Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion

Writing Arguments: Types of Argument

Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your Writing

Dictionaries

General Style Manuals

Researching on the Internet

Special Style Manuals

Writing Handbooks

Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer Reviewing

Collaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project

Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report

Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve

Collaborative Writing: Methodology

Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation

Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members

Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan

General Introduction

Peer Reviewing

Appendix C: Developing an Improvement Plan

Working with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades

Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project Schedule

Devising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule

Reviewing Your Plan with Others

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Chapter 3: The Writing Process, Composing, and Revising

3.1 The Writing Process

Sarah M. Lacy and Melanie Gagich

What is The Writing Process?

Donald M. Murray, a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist and educator, presented his important article, “Teach Writing as a Process Not Product,” in 1972. In the article, he criticizes writing instructors’ tendency to view student writing as “literature” and to focus our attentions on the “product” (the finished essay) while grading. The idea that students are producing finished works ready for close examination and evaluation by their instructor is fraught with problems because writing is really a process and arguably a process that is never finished.

Murray explains why writing is an ongoing process:

What is the process we [writing instructors] should teach? It is the process of discovery through language. It is the process of exploration of what we know and what we feel about what we know through language. It is the process of using language to learn about our world, to evaluate what we learn about our world, to communicate what we learn about our world. Instead of teaching finished writing, we should teach unfinished writing, and glory in its unfinishedness. (4)

You will find that many college writing instructors have answered Murray’s call to “teach writing as a process” and due to shifting our focus on process rather than product, you will find yourself spending a lot of time brainstorming, drafting, revising, and editing. Embracing writing as a process helps apprehensive writers see that writing is not only about grammatical accuracy or “being a good writer.”

The Writing Process

The most important lesson to understand about the writing process, is that it is recursive, meaning that you need to move back and forth between some or all of the steps; there are many ways to approach this process. Allowing yourself enough time to begin the assignment before it is due, will give you time to move from one step to the other, and back as needed. Perhaps the easiest way to think about this process is as a series of steps that you can move from one to the other and back again.

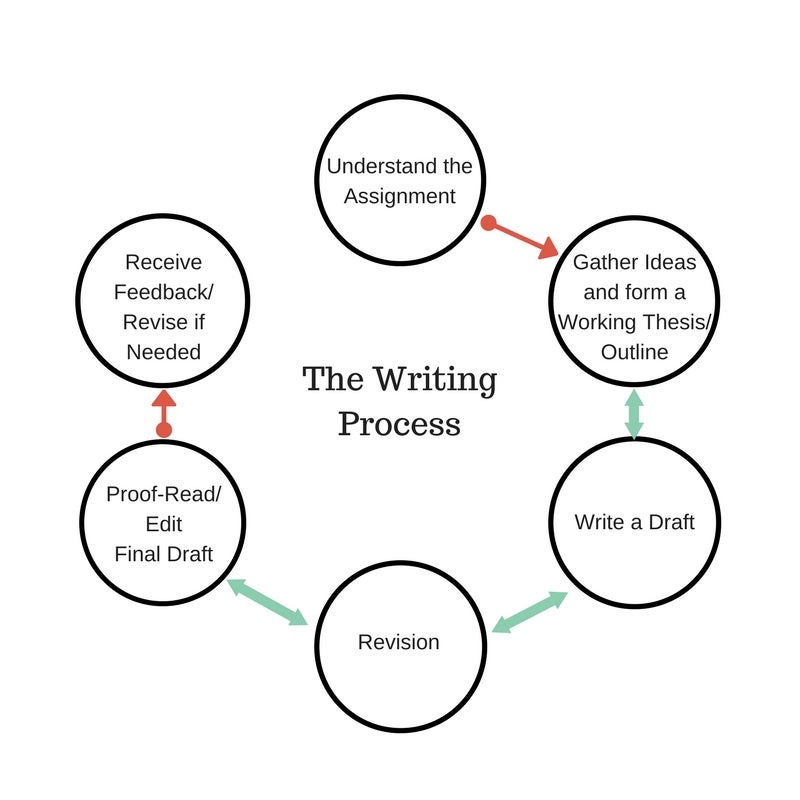

The Writing Process in 6 Steps

The following steps have been adapted from the work of Paul Eschholz and Alfred Rosa, found in their book Subject & Strategy . The authors focus on discussing writing as a series of steps that can be adapted to meet any writer’s needs; below, the steps have been modified to fit your needs as first-year writers. While reading through the steps below, remember that every writer has a unique approach to the writing process. The steps are presented in such a way that allow for any writer to understand the process as a whole, so that they can feel prepared when beginning a paper. Take special note of all the tips and guidance presented with each step, as well as suggested further reading, remembering that writing is a skill that needs practice: make sure to spend time developing your own connection to each step when writing a paper. You can also watch an introductory video on the steps:

The detailed steps are as follows:

Step 1 – Understand the Assignment

Always read over the entire assignment sheet provided to you by your instructor. Think of this sheet as a contract; by accepting the sheet, you are agreeing to follow all guidelines and requirements that have been provided. This sheet is a direct communication from your instructor to you, laying out every expectation and requirement of an assignment. Follow each to ensure you are conducting and completing the assignment properly.

See Section 3.2 for a closer look at how to use an assignment sheet.

Step 2 – Gather Ideas and Form Working Thesis

Once you understand the assignment, you will need to collect information in order to understand your topic, and decide where you would like the paper to lead. This step can be conducted in various ways. Researching to build content knowledge is always a good place to start this step, so make sure to check out Chapter 8: The Research Process for a more specified look at various research methods.

After you have conducted some research begin brainstorming. You can do this in a variety of ways:

- Free Writing

- Listing ideas

- Generate a list of questions

- Clustering/ Mapping (creating a bubble chart)

- Create a basic outline

Then, you will want to formulate a Working Thesis . A working thesis is different than the thesis found in a final draft : it will not be specific nor as narrowed. Think of a working thesis as the general focus of the paper, helping to shape your research and brainstorming activities. As you will later spend ample time working and re-working a draft, allow yourself the freedom to revise this thesis as you become more familiar with your topic and purpose.

See Section 4.2: Creating a Thesis for more information on thesis statements.

Step 3 – Write a Draft

After completing Steps 1 and 2, you are ready to begin putting all parts and ideas together into a full length draft. It is important to remember that this is a first/rough draft, and the goal is to get all of your thoughts into writing, not generating a perfect draft. Do not get hung up with your language at this point, focus on the larger ideas and content.

Organization is a very important part of this step, and if you have not already composed an outline during Step 2, consider writing one now. The purpose of an outline is to create a logical flow of claims, evidence, and links before or during the drafting process; experiment with outlines to learn when and how they can work for you.

Outlines are great at helping you organize your outside sources, if you need to use some within a particular assignment. Start by generating a list of claims (or main ideas) to support your thesis, and decide which source belongs with each idea, knowing that you may (and should) use your sources more than once, with more than one claim.

Step 4 – Revise the Draft(s)

This is the step in which you are likely to spend the majority of your time. This section is different from simply “editing” or “proof reading” because you are looking for larger context issues; for example, this is when you need to check your topic sentences and transitions, make sure each claim matches the thesis statement, and so on. Return to Steps 1 and 2 as needed, to ensure you are on the right track and your draft is properly adhering to the guidelines of the assignment.

The revision portion of the writing process is also where you will need to make sure all of your paragraphs are fully developed as appropriate for the assignment. If you need to have outside sources present, this is when you will make sure that all are working properly together. If the assignment is a summary, this is when you will need to double check all paraphrasing to make sure it correctly represents the ideas and information of the source text .

It is likely that your professor will instruct you to complete Peer Editing . Learn more about this process in Section 3.4.

Step 5 – Proof-Read/Edit the Draft(s)

Once the larger content issues have been resolved and you are moving towards a final draft, work through the paper looking for grammar and style issues. This step is when you need to make sure that your tone is appropriate for the assignment (for example, you will need to make sure you have remained in a formal tone for all academic papers), that sources are properly integrated into your own work if your assignment calls for them, etc. Consider using the checklist offered in Section 3.6 .

When entering the final step, go back to the assignment sheet, read it over once more in full, and then conduct a close reading. Doing this will help you to ensure you have completed all components of the assignment as per your instructor’s guidance.

Step 6 – Turn in the Draft, Receive Feedback, and Revise (if needed)

Once your draft is completed, turned in, and handed back with edits from your instructor, you may have an opportunity to revise, and turn in again to help raise your grade. As the goal of the FYW class is to improve your writing, this is an essential step to consider so that you get the most out of the course. Ask your instructor for more detail.

Works Cited

Eschholz, Paul and Alfred Rosa. Subject & Strategy: A Writer’s Reader. 11th ed., Bedford/St. Martin, 2007.

Text can refer to the written word: “Proofread your text before submitting the paper.”

A text refers to any form of communication, primarily written or oral, that forms a coherent unit, often as an object of study. A book can be a text, and a speech can be a text, but television commercials, magazine ads, website, and emails can also be texts: “Dieting advertisements formed one of the texts we studied in my Sociology class.”

A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing by Sarah M. Lacy and Melanie Gagich is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Feedback/Errata

Comments are closed.

The Writing Process

The Writing Process Explained

Understanding the writing process provides a student with a straightforward step-by-step procedure that they can follow. It means they can replicate the process no matter what type of nonfiction text they are asked to produce.

In this article, we’ll look at the 5 step writing process that guides students from prewriting to submitting their polished work quickly and easily.

While explaining each stage of the process in detail, we’ll suggest some activities you can use with your students to help them successfully complete each stage.

THE STAGES OF THE WRITING PROCESS

The five steps of the writing process are made up of the following stages:

- Pre-writing: In this stage, students brainstorm ideas, plan content, and gather the necessary information to ensure their thinking is organized logically.

- Drafting: Students construct ideas in basic sentences and paragraphs without getting caught up with perfection. It is in this stage that the pre-writing process becomes refined and shaped.

- Revising: This is where students revise their draft and make changes to improve the content, organization, and overall structure. Any obvious spelling and grammatical errors might also be improved at this stage.

- Editing: It is in this stage where students make the shift from improving the structure of their writing to focusing on enhancing the written quality of sentences and paragraphs through improving word choice, punctuation, and capitalization, and all spelling and grammatical errors are corrected. Ensure students know this is their final opportunity to alter their writing, which will play a significant role in the assessment process.

- Submitting / Publishing: Students can share their writing with the world, their teachers, friends, and family through various platforms and tools.

Be aware that this list is not a definitive linear process, and it may be advisable to revisit some of these steps in some cases as students learn the craft of writing over time.

Daily Quick Writes For All Text Types

Our FUN DAILY QUICK WRITE TASKS will teach your students the fundamentals of CREATIVE WRITING across all text types. Packed with 52 ENGAGING ACTIVITIES

STAGE ONE: THE WRITING PROCESS

GET READY TO WRITE

The prewriting stage covers anything the student does before they begin to draft their text. It includes many things such as thinking, brainstorming, discussing ideas with others, sketching outlines, gathering information through interviewing people, assessing data, and researching in the library and online.

The intention at the prewriting stage is to collect the raw material that will fuel the writing process. This involves the student doing 3 things:

- Understanding the conventions of the text type

- Gathering up facts, opinions, ideas, data, vocabulary, etc through research and discussion

- Organizing resources and planning out the writing process.

By the time students have finished the pre-writing stage, they will want to have completed at least one of these tasks depending upon the text type they are writing.

- Choose a topic: Ensure your students select a topic that is interesting and relevant to them.

- Brainstorm ideas: Once they have a topic, brainstorm and write their ideas down, considering what they already know about the topic and what they need to research further. Students might want to use brainstorming techniques such as mind mapping, free writing, or listing.

- Research: This one is crucial for informational and nonfiction writing. Students may need to research to gather more information and use reliable sources such as books, academic journals, and credible websites.

- Organize your ideas: This can be challenging for younger students, but once they have a collection of ideas and information, help them to organize them logically by creating an outline, using headings and subheadings, or grouping related ideas.

- Develop a thesis statement: This one is only for an academic research paper and should clearly state your paper’s main idea or argument. It should be specific and debatable.

Before beginning the research and planning parts of the process, the student must take some time to consider the demands of the text type or genre they are asked to write, as this will influence how they research and plan.

PREWRITING TEACHING ACTIVITY

As with any stage in the writing process, students will benefit immensely from seeing the teacher modelling activities to support that stage.

In this activity, you can model your approach to the prewriting stage for students to emulate. Eventually, they will develop their own specific approach, but for now, having a clear model to follow will serve them well.

Starting with an essay title written in the center of the whiteboard, brainstorm ideas as a class and write these ideas branching from the title to create a mind map.

From there, you can help students identify areas for further research and help them to create graphic organizers to record their ideas.

Explain to the students that while idea generation is an integral part of the prewriting stage, generating ideas is also important throughout all the other stages of the writing process.

STAGE TWO: THE WRITING PROCESS

PUT YOUR IDEAS ON PAPER

Drafting is when the student begins to corral the unruly fruits of the prewriting stage into orderly sentences and paragraphs.

When their writing is based on solid research and planning, it will be much easier for the student to manage. A poorly executed first stage can see pencils stuck at the starting line and persistent complaints of ‘writer’s block’ from the students.