- Privacy Policy

Home » Dissertation – Format, Example and Template

Dissertation – Format, Example and Template

Table of Contents

Dissertation

Definition:

Dissertation is a lengthy and detailed academic document that presents the results of original research on a specific topic or question. It is usually required as a final project for a doctoral degree or a master’s degree.

Dissertation Meaning in Research

In Research , a dissertation refers to a substantial research project that students undertake in order to obtain an advanced degree such as a Ph.D. or a Master’s degree.

Dissertation typically involves the exploration of a particular research question or topic in-depth, and it requires students to conduct original research, analyze data, and present their findings in a scholarly manner. It is often the culmination of years of study and represents a significant contribution to the academic field.

Types of Dissertation

Types of Dissertation are as follows:

Empirical Dissertation

An empirical dissertation is a research study that uses primary data collected through surveys, experiments, or observations. It typically follows a quantitative research approach and uses statistical methods to analyze the data.

Non-Empirical Dissertation

A non-empirical dissertation is based on secondary sources, such as books, articles, and online resources. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as content analysis or discourse analysis.

Narrative Dissertation

A narrative dissertation is a personal account of the researcher’s experience or journey. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as interviews, focus groups, or ethnography.

Systematic Literature Review

A systematic literature review is a comprehensive analysis of existing research on a specific topic. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as meta-analysis or thematic analysis.

Case Study Dissertation

A case study dissertation is an in-depth analysis of a specific individual, group, or organization. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as interviews, observations, or document analysis.

Mixed-Methods Dissertation

A mixed-methods dissertation combines both quantitative and qualitative research approaches to gather and analyze data. It typically uses methods such as surveys, interviews, and focus groups, as well as statistical analysis.

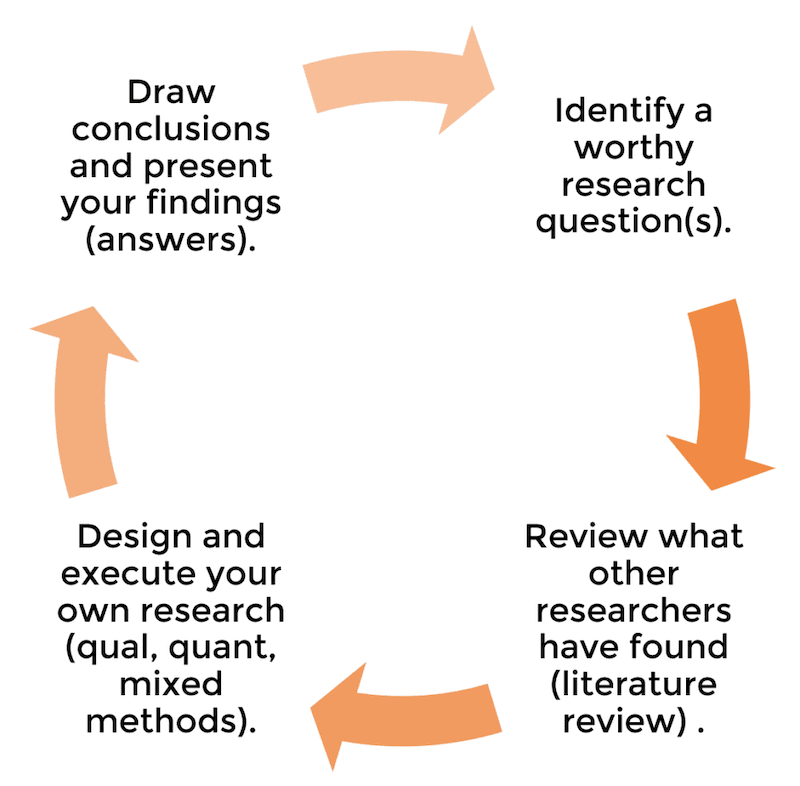

How to Write a Dissertation

Here are some general steps to help guide you through the process of writing a dissertation:

- Choose a topic : Select a topic that you are passionate about and that is relevant to your field of study. It should be specific enough to allow for in-depth research but broad enough to be interesting and engaging.

- Conduct research : Conduct thorough research on your chosen topic, utilizing a variety of sources, including books, academic journals, and online databases. Take detailed notes and organize your information in a way that makes sense to you.

- Create an outline : Develop an outline that will serve as a roadmap for your dissertation. The outline should include the introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- Write the introduction: The introduction should provide a brief overview of your topic, the research questions, and the significance of the study. It should also include a clear thesis statement that states your main argument.

- Write the literature review: The literature review should provide a comprehensive analysis of existing research on your topic. It should identify gaps in the research and explain how your study will fill those gaps.

- Write the methodology: The methodology section should explain the research methods you used to collect and analyze data. It should also include a discussion of any limitations or weaknesses in your approach.

- Write the results: The results section should present the findings of your research in a clear and organized manner. Use charts, graphs, and tables to help illustrate your data.

- Write the discussion: The discussion section should interpret your results and explain their significance. It should also address any limitations of the study and suggest areas for future research.

- Write the conclusion: The conclusion should summarize your main findings and restate your thesis statement. It should also provide recommendations for future research.

- Edit and revise: Once you have completed a draft of your dissertation, review it carefully to ensure that it is well-organized, clear, and free of errors. Make any necessary revisions and edits before submitting it to your advisor for review.

Dissertation Format

The format of a dissertation may vary depending on the institution and field of study, but generally, it follows a similar structure:

- Title Page: This includes the title of the dissertation, the author’s name, and the date of submission.

- Abstract : A brief summary of the dissertation’s purpose, methods, and findings.

- Table of Contents: A list of the main sections and subsections of the dissertation, along with their page numbers.

- Introduction : A statement of the problem or research question, a brief overview of the literature, and an explanation of the significance of the study.

- Literature Review : A comprehensive review of the literature relevant to the research question or problem.

- Methodology : A description of the methods used to conduct the research, including data collection and analysis procedures.

- Results : A presentation of the findings of the research, including tables, charts, and graphs.

- Discussion : A discussion of the implications of the findings, their significance in the context of the literature, and limitations of the study.

- Conclusion : A summary of the main points of the study and their implications for future research.

- References : A list of all sources cited in the dissertation.

- Appendices : Additional materials that support the research, such as data tables, charts, or transcripts.

Dissertation Outline

Dissertation Outline is as follows:

Title Page:

- Title of dissertation

- Author name

- Institutional affiliation

- Date of submission

- Brief summary of the dissertation’s research problem, objectives, methods, findings, and implications

- Usually around 250-300 words

Table of Contents:

- List of chapters and sections in the dissertation, with page numbers for each

I. Introduction

- Background and context of the research

- Research problem and objectives

- Significance of the research

II. Literature Review

- Overview of existing literature on the research topic

- Identification of gaps in the literature

- Theoretical framework and concepts

III. Methodology

- Research design and methods used

- Data collection and analysis techniques

- Ethical considerations

IV. Results

- Presentation and analysis of data collected

- Findings and outcomes of the research

- Interpretation of the results

V. Discussion

- Discussion of the results in relation to the research problem and objectives

- Evaluation of the research outcomes and implications

- Suggestions for future research

VI. Conclusion

- Summary of the research findings and outcomes

- Implications for the research topic and field

- Limitations and recommendations for future research

VII. References

- List of sources cited in the dissertation

VIII. Appendices

- Additional materials that support the research, such as tables, figures, or questionnaires.

Example of Dissertation

Here is an example Dissertation for students:

Title : Exploring the Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on Academic Achievement and Well-being among College Students

This dissertation aims to investigate the impact of mindfulness meditation on the academic achievement and well-being of college students. Mindfulness meditation has gained popularity as a technique for reducing stress and enhancing mental health, but its effects on academic performance have not been extensively studied. Using a randomized controlled trial design, the study will compare the academic performance and well-being of college students who practice mindfulness meditation with those who do not. The study will also examine the moderating role of personality traits and demographic factors on the effects of mindfulness meditation.

Chapter Outline:

Chapter 1: Introduction

- Background and rationale for the study

- Research questions and objectives

- Significance of the study

- Overview of the dissertation structure

Chapter 2: Literature Review

- Definition and conceptualization of mindfulness meditation

- Theoretical framework of mindfulness meditation

- Empirical research on mindfulness meditation and academic achievement

- Empirical research on mindfulness meditation and well-being

- The role of personality and demographic factors in the effects of mindfulness meditation

Chapter 3: Methodology

- Research design and hypothesis

- Participants and sampling method

- Intervention and procedure

- Measures and instruments

- Data analysis method

Chapter 4: Results

- Descriptive statistics and data screening

- Analysis of main effects

- Analysis of moderating effects

- Post-hoc analyses and sensitivity tests

Chapter 5: Discussion

- Summary of findings

- Implications for theory and practice

- Limitations and directions for future research

- Conclusion and contribution to the literature

Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Recap of the research questions and objectives

- Summary of the key findings

- Contribution to the literature and practice

- Implications for policy and practice

- Final thoughts and recommendations.

References :

List of all the sources cited in the dissertation

Appendices :

Additional materials such as the survey questionnaire, interview guide, and consent forms.

Note : This is just an example and the structure of a dissertation may vary depending on the specific requirements and guidelines provided by the institution or the supervisor.

How Long is a Dissertation

The length of a dissertation can vary depending on the field of study, the level of degree being pursued, and the specific requirements of the institution. Generally, a dissertation for a doctoral degree can range from 80,000 to 100,000 words, while a dissertation for a master’s degree may be shorter, typically ranging from 20,000 to 50,000 words. However, it is important to note that these are general guidelines and the actual length of a dissertation can vary widely depending on the specific requirements of the program and the research topic being studied. It is always best to consult with your academic advisor or the guidelines provided by your institution for more specific information on dissertation length.

Applications of Dissertation

Here are some applications of a dissertation:

- Advancing the Field: Dissertations often include new research or a new perspective on existing research, which can help to advance the field. The results of a dissertation can be used by other researchers to build upon or challenge existing knowledge, leading to further advancements in the field.

- Career Advancement: Completing a dissertation demonstrates a high level of expertise in a particular field, which can lead to career advancement opportunities. For example, having a PhD can open doors to higher-paying jobs in academia, research institutions, or the private sector.

- Publishing Opportunities: Dissertations can be published as books or journal articles, which can help to increase the visibility and credibility of the author’s research.

- Personal Growth: The process of writing a dissertation involves a significant amount of research, analysis, and critical thinking. This can help students to develop important skills, such as time management, problem-solving, and communication, which can be valuable in both their personal and professional lives.

- Policy Implications: The findings of a dissertation can have policy implications, particularly in fields such as public health, education, and social sciences. Policymakers can use the research to inform decision-making and improve outcomes for the population.

When to Write a Dissertation

Here are some situations where writing a dissertation may be necessary:

- Pursuing a Doctoral Degree: Writing a dissertation is usually a requirement for earning a doctoral degree, so if you are interested in pursuing a doctorate, you will likely need to write a dissertation.

- Conducting Original Research : Dissertations require students to conduct original research on a specific topic. If you are interested in conducting original research on a topic, writing a dissertation may be the best way to do so.

- Advancing Your Career: Some professions, such as academia and research, may require individuals to have a doctoral degree. Writing a dissertation can help you advance your career by demonstrating your expertise in a particular area.

- Contributing to Knowledge: Dissertations are often based on original research that can contribute to the knowledge base of a field. If you are passionate about advancing knowledge in a particular area, writing a dissertation can help you achieve that goal.

- Meeting Academic Requirements : If you are a graduate student, writing a dissertation may be a requirement for completing your program. Be sure to check with your academic advisor to determine if this is the case for you.

Purpose of Dissertation

some common purposes of a dissertation include:

- To contribute to the knowledge in a particular field : A dissertation is often the culmination of years of research and study, and it should make a significant contribution to the existing body of knowledge in a particular field.

- To demonstrate mastery of a subject: A dissertation requires extensive research, analysis, and writing, and completing one demonstrates a student’s mastery of their subject area.

- To develop critical thinking and research skills : A dissertation requires students to think critically about their research question, analyze data, and draw conclusions based on evidence. These skills are valuable not only in academia but also in many professional fields.

- To demonstrate academic integrity: A dissertation must be conducted and written in accordance with rigorous academic standards, including ethical considerations such as obtaining informed consent, protecting the privacy of participants, and avoiding plagiarism.

- To prepare for an academic career: Completing a dissertation is often a requirement for obtaining a PhD and pursuing a career in academia. It can demonstrate to potential employers that the student has the necessary skills and experience to conduct original research and make meaningful contributions to their field.

- To develop writing and communication skills: A dissertation requires a significant amount of writing and communication skills to convey complex ideas and research findings in a clear and concise manner. This skill set can be valuable in various professional fields.

- To demonstrate independence and initiative: A dissertation requires students to work independently and take initiative in developing their research question, designing their study, collecting and analyzing data, and drawing conclusions. This demonstrates to potential employers or academic institutions that the student is capable of independent research and taking initiative in their work.

- To contribute to policy or practice: Some dissertations may have a practical application, such as informing policy decisions or improving practices in a particular field. These dissertations can have a significant impact on society, and their findings may be used to improve the lives of individuals or communities.

- To pursue personal interests: Some students may choose to pursue a dissertation topic that aligns with their personal interests or passions, providing them with the opportunity to delve deeper into a topic that they find personally meaningful.

Advantage of Dissertation

Some advantages of writing a dissertation include:

- Developing research and analytical skills: The process of writing a dissertation involves conducting extensive research, analyzing data, and presenting findings in a clear and coherent manner. This process can help students develop important research and analytical skills that can be useful in their future careers.

- Demonstrating expertise in a subject: Writing a dissertation allows students to demonstrate their expertise in a particular subject area. It can help establish their credibility as a knowledgeable and competent professional in their field.

- Contributing to the academic community: A well-written dissertation can contribute new knowledge to the academic community and potentially inform future research in the field.

- Improving writing and communication skills : Writing a dissertation requires students to write and present their research in a clear and concise manner. This can help improve their writing and communication skills, which are essential for success in many professions.

- Increasing job opportunities: Completing a dissertation can increase job opportunities in certain fields, particularly in academia and research-based positions.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Library Guides

Dissertations 4: methodology: methods.

- Introduction & Philosophy

- Methodology

Primary & Secondary Sources, Primary & Secondary Data

When describing your research methods, you can start by stating what kind of secondary and, if applicable, primary sources you used in your research. Explain why you chose such sources, how well they served your research, and identify possible issues encountered using these sources.

Definitions

There is some confusion on the use of the terms primary and secondary sources, and primary and secondary data. The confusion is also due to disciplinary differences (Lombard 2010). Whilst you are advised to consult the research methods literature in your field, we can generalise as follows:

Secondary sources

Secondary sources normally include the literature (books and articles) with the experts' findings, analysis and discussions on a certain topic (Cottrell, 2014, p123). Secondary sources often interpret primary sources.

Primary sources

Primary sources are "first-hand" information such as raw data, statistics, interviews, surveys, law statutes and law cases. Even literary texts, pictures and films can be primary sources if they are the object of research (rather than, for example, documentaries reporting on something else, in which case they would be secondary sources). The distinction between primary and secondary sources sometimes lies on the use you make of them (Cottrell, 2014, p123).

Primary data

Primary data are data (primary sources) you directly obtained through your empirical work (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill 2015, p316).

Secondary data

Secondary data are data (primary sources) that were originally collected by someone else (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill 2015, p316).

Comparison between primary and secondary data

Use

Virtually all research will use secondary sources, at least as background information.

Often, especially at the postgraduate level, it will also use primary sources - secondary and/or primary data. The engagement with primary sources is generally appreciated, as less reliant on others' interpretations, and closer to 'facts'.

The use of primary data, as opposed to secondary data, demonstrates the researcher's effort to do empirical work and find evidence to answer her specific research question and fulfill her specific research objectives. Thus, primary data contribute to the originality of the research.

Ultimately, you should state in this section of the methodology:

What sources and data you are using and why (how are they going to help you answer the research question and/or test the hypothesis.

If using primary data, why you employed certain strategies to collect them.

What the advantages and disadvantages of your strategies to collect the data (also refer to the research in you field and research methods literature).

Quantitative, Qualitative & Mixed Methods

The methodology chapter should reference your use of quantitative research, qualitative research and/or mixed methods. The following is a description of each along with their advantages and disadvantages.

Quantitative research

Quantitative research uses numerical data (quantities) deriving, for example, from experiments, closed questions in surveys, questionnaires, structured interviews or published data sets (Cottrell, 2014, p93). It normally processes and analyses this data using quantitative analysis techniques like tables, graphs and statistics to explore, present and examine relationships and trends within the data (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, 2015, p496).

Qualitative research

Qualitative research is generally undertaken to study human behaviour and psyche. It uses methods like in-depth case studies, open-ended survey questions, unstructured interviews, focus groups, or unstructured observations (Cottrell, 2014, p93). The nature of the data is subjective, and also the analysis of the researcher involves a degree of subjective interpretation. Subjectivity can be controlled for in the research design, or has to be acknowledged as a feature of the research. Subject-specific books on (qualitative) research methods offer guidance on such research designs.

Mixed methods

Mixed-method approaches combine both qualitative and quantitative methods, and therefore combine the strengths of both types of research. Mixed methods have gained popularity in recent years.

When undertaking mixed-methods research you can collect the qualitative and quantitative data either concurrently or sequentially. If sequentially, you can for example, start with a few semi-structured interviews, providing qualitative insights, and then design a questionnaire to obtain quantitative evidence that your qualitative findings can also apply to a wider population (Specht, 2019, p138).

Ultimately, your methodology chapter should state:

Whether you used quantitative research, qualitative research or mixed methods.

Why you chose such methods (and refer to research method sources).

Why you rejected other methods.

How well the method served your research.

The problems or limitations you encountered.

Doug Specht, Senior Lecturer at the Westminster School of Media and Communication, explains mixed methods research in the following video:

LinkedIn Learning Video on Academic Research Foundations: Quantitative

The video covers the characteristics of quantitative research, and explains how to approach different parts of the research process, such as creating a solid research question and developing a literature review. He goes over the elements of a study, explains how to collect and analyze data, and shows how to present your data in written and numeric form.

Link to quantitative research video

Some Types of Methods

There are several methods you can use to get primary data. To reiterate, the choice of the methods should depend on your research question/hypothesis.

Whatever methods you will use, you will need to consider:

why did you choose one technique over another? What were the advantages and disadvantages of the technique you chose?

what was the size of your sample? Who made up your sample? How did you select your sample population? Why did you choose that particular sampling strategy?)

ethical considerations (see also tab...)

safety considerations

validity

feasibility

recording

procedure of the research (see box procedural method...).

Check Stella Cottrell's book Dissertations and Project Reports: A Step by Step Guide for some succinct yet comprehensive information on most methods (the following account draws mostly on her work). Check a research methods book in your discipline for more specific guidance.

Experiments

Experiments are useful to investigate cause and effect, when the variables can be tightly controlled. They can test a theory or hypothesis in controlled conditions. Experiments do not prove or disprove an hypothesis, instead they support or not support an hypothesis. When using the empirical and inductive method it is not possible to achieve conclusive results. The results may only be valid until falsified by other experiments and observations.

For more information on Scientific Method, click here .

Observations

Observational methods are useful for in-depth analyses of behaviours in people, animals, organisations, events or phenomena. They can test a theory or products in real life or simulated settings. They generally a qualitative research method.

Questionnaires and surveys

Questionnaires and surveys are useful to gain opinions, attitudes, preferences, understandings on certain matters. They can provide quantitative data that can be collated systematically; qualitative data, if they include opportunities for open-ended responses; or both qualitative and quantitative elements.

Interviews

Interviews are useful to gain rich, qualitative information about individuals' experiences, attitudes or perspectives. With interviews you can follow up immediately on responses for clarification or further details. There are three main types of interviews: structured (following a strict pattern of questions, which expect short answers), semi-structured (following a list of questions, with the opportunity to follow up the answers with improvised questions), and unstructured (following a short list of broad questions, where the respondent can lead more the conversation) (Specht, 2019, p142).

This short video on qualitative interviews discusses best practices and covers qualitative interview design, preparation and data collection methods.

Focus groups

In this case, a group of people (normally, 4-12) is gathered for an interview where the interviewer asks questions to such group of participants. Group interactions and discussions can be highly productive, but the researcher has to beware of the group effect, whereby certain participants and views dominate the interview (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill 2015, p419). The researcher can try to minimise this by encouraging involvement of all participants and promoting a multiplicity of views.

This video focuses on strategies for conducting research using focus groups.

Check out the guidance on online focus groups by Aliaksandr Herasimenka, which is attached at the bottom of this text box.

Case study

Case studies are often a convenient way to narrow the focus of your research by studying how a theory or literature fares with regard to a specific person, group, organisation, event or other type of entity or phenomenon you identify. Case studies can be researched using other methods, including those described in this section. Case studies give in-depth insights on the particular reality that has been examined, but may not be representative of what happens in general, they may not be generalisable, and may not be relevant to other contexts. These limitations have to be acknowledged by the researcher.

Content analysis

Content analysis consists in the study of words or images within a text. In its broad definition, texts include books, articles, essays, historical documents, speeches, conversations, advertising, interviews, social media posts, films, theatre, paintings or other visuals. Content analysis can be quantitative (e.g. word frequency) or qualitative (e.g. analysing intention and implications of the communication). It can detect propaganda, identify intentions of writers, and can see differences in types of communication (Specht, 2019, p146). Check this page on collecting, cleaning and visualising Twitter data.

Extra links and resources:

Research Methods

A clear and comprehensive overview of research methods by Emerald Publishing. It includes: crowdsourcing as a research tool; mixed methods research; case study; discourse analysis; ground theory; repertory grid; ethnographic method and participant observation; interviews; focus group; action research; analysis of qualitative data; survey design; questionnaires; statistics; experiments; empirical research; literature review; secondary data and archival materials; data collection.

Doing your dissertation during the COVID-19 pandemic

Resources providing guidance on doing dissertation research during the pandemic: Online research methods; Secondary data sources; Webinars, conferences and podcasts;

- Virtual Focus Groups Guidance on managing virtual focus groups

5 Minute Methods Videos

The following are a series of useful videos that introduce research methods in five minutes. These resources have been produced by lecturers and students with the University of Westminster's School of Media and Communication.

Case Study Research

Research Ethics

Quantitative Content Analysis

Sequential Analysis

Qualitative Content Analysis

Thematic Analysis

Social Media Research

Mixed Method Research

Procedural Method

In this part, provide an accurate, detailed account of the methods and procedures that were used in the study or the experiment (if applicable!).

Include specifics about participants, sample, materials, design and methods.

If the research involves human subjects, then include a detailed description of who and how many participated along with how the participants were selected.

Describe all materials used for the study, including equipment, written materials and testing instruments.

Identify the study's design and any variables or controls employed.

Write out the steps in the order that they were completed.

Indicate what participants were asked to do, how measurements were taken and any calculations made to raw data collected.

Specify statistical techniques applied to the data to reach your conclusions.

Provide evidence that you incorporated rigor into your research. This is the quality of being thorough and accurate and considers the logic behind your research design.

Highlight any drawbacks that may have limited your ability to conduct your research thoroughly.

You have to provide details to allow others to replicate the experiment and/or verify the data, to test the validity of the research.

Bibliography

Cottrell, S. (2014). Dissertations and project reports: a step by step guide. Hampshire, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lombard, E. (2010). Primary and secondary sources. The Journal of Academic Librarianship , 36(3), 250-253

Saunders, M.N.K., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2015). Research Methods for Business Students. New York: Pearson Education.

Specht, D. (2019). The Media And Communications Study Skills Student Guide . London: University of Westminster Press.

- << Previous: Introduction & Philosophy

- Next: Ethics >>

- Last Updated: Sep 14, 2022 12:58 PM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/methodology-for-dissertations

CONNECT WITH US

Write Your Dissertation Using Only Secondary Research

Writing a dissertation is already difficult to begin with but it can appear to be a daunting challenge when you only have other people’s research as a guide for proving a brand new hypothesis! You might not be familiar with the research or even confident in how to use it but if secondary research is what you’re working with then you’re in luck. It’s actually one of the easiest methods to write about!

Secondary research is research that has already been carried out and collected by someone else. It means you’re using data that’s already out there rather than conducting your own research – this is called primary research. Thankfully secondary will save you time in the long run! Primary research often means spending time finding people and then relying on them for results, something you could do without, especially if you’re in a rush. Read more about the advantages and disadvantages of primary research .

So, where do you find secondary data?

Secondary research is available in many different places and it’s important to explore all areas so you can be sure you’re looking at research you can trust. If you’re just starting your dissertation you might be feeling a little overwhelmed with where to begin but once you’ve got your subject clarified, it’s time to get researching! Some good places to search include:

- Libraries (your own university or others – books and journals are the most popular resources!)

- Government records

- Online databases

- Credible Surveys (this means they need to be from a reputable source)

- Search engines (google scholar for example).

The internet has everything you’ll need but you’ve got to make sure it’s legitimate and published information. It’s also important to check out your student library because it’s likely you’ll have access to a great range of materials right at your fingertips. There’s a strong chance someone before you has looked for the same topic so it’s a great place to start.

What are the two different types of secondary data?

It’s important to know before you start looking that they are actually two different types of secondary research in terms of data, Qualitative and quantitative. You might be looking for one more specifically than the other, or you could use a mix of both. Whichever it is, it’s important to know the difference between them.

- Qualitative data – This is usually descriptive data and can often be received from interviews, questionnaires or observations. This kind of data is usually used to capture the meaning behind something.

- Quantitative data – This relates to quantities meaning numbers. It consists of information that can be measured in numerical data sets.

The type of data you want to be captured in your dissertation will depend on your overarching question – so keep it in mind throughout your search!

Getting started

When you’re getting ready to write your dissertation it’s a good idea to plan out exactly what you’re looking to answer. We recommend splitting this into chapters with subheadings and ensuring that each point you want to discuss has a reliable source to back it up. This is always a good way to find out if you’ve collected enough secondary data to suit your workload. If there’s a part of your plan that’s looking a bit empty, it might be a good idea to do some more research and fill the gap. It’s never a bad thing to have too much research, just as long as you know what to do with it and you’re willing to disregard the less important parts. Just make sure you prioritise the research that backs up your overall point so each section has clarity.

Then it’s time to write your introduction. In your intro, you will want to emphasise what your dissertation aims to cover within your writing and outline your research objectives. You can then follow up with the context around this question and identify why your research is meaningful to a wider audience.

The body of your dissertation

Before you get started on the main chapters of your dissertation, you need to find out what theories relate to your chosen subject and the research that has already been carried out around it.

Literature Reviews

Your literature review will be a summary of any previous research carried out on the topic and should have an intro and conclusion like any other body of the academic text. When writing about this research you want to make sure you are describing, summarising, evaluating and analysing each piece. You shouldn’t just rephrase what the researcher has found but make your own interpretations. This is one crucial way to score some marks. You also want to identify any themes between each piece of research to emphasise their relevancy. This will show that you understand your topic in the context of others, a great way to prove you’ve really done your reading!

Theoretical Frameworks

The theoretical framework in your dissertation will be explaining what you’ve found. It will form your main chapters after your lit review. The most important part is that you use it wisely. Of course, depending on your topic there might be a lot of different theories and you can’t include them all so make sure to select the ones most relevant to your dissertation. When starting on the framework it’s important to detail the key parts to your hypothesis and explain them. This creates a good foundation for what you’re going to discuss and helps readers understand the topic.

To finish off the theoretical framework you want to start suggesting where your research will fit in with those texts in your literature review. You might want to challenge a theory by critiquing it with another or explain how two theories can be combined to make a new outcome. Either way, you must make a clear link between their theories and your own interpretations – remember, this is not opinion based so don’t make a conclusion unless you can link it back to the facts!

Concluding your dissertation

Your conclusion will highlight the outcome of the research you’ve undertaken. You want to make this clear and concise without repeating information you’ve already mentioned in your main body paragraphs. A great way to avoid repetition is to highlight any overarching themes your conclusions have shown

When writing your conclusion it’s important to include the following elements:

- Summary – A summary of what you’ve found overall from your research and the conclusions you have come to as a result.

- Recommendations – Recommendations on what you think the next steps should be. Is there something you would change about this research to improve it or further develop it?

- Show your contribution – It’s important to show how you’ve contributed to the current knowledge on the topic and not just repeated what other researchers have found.

Hopefully, this helps you with your secondary data research for your dissertation! It’s definitely not as hard as it seems, the hardest part will be gathering all of the information in the first place. It may take a while but once you’ve found your flow – it’ll get easier, promise! You may also want to read about the advantages and disadvantages of secondary research .

You may also like

- Utility Menu

Harvard University Program on Survey Research

- How to Frame and Explain the Survey Data Used in a Thesis

Surveys are a special research tool with strengths, weaknesses, and a language all of their own. There are many different steps to designing and conducting a survey, and survey researchers have specific ways of describing what they do.

This handout, based on an annual workshop offered by the Program on Survey Research at Harvard, is geared toward undergraduate honors thesis writers using survey data.

PSR Resources

- Managing and Manipulating Survey Data: A Beginners Guide

- Finding and Hiring Survey Contractors

- Overview of Cognitive Testing and Questionnaire Evaluation

- Questionnaire Design Tip Sheet

- Sampling, Coverage, and Nonresponse Tip Sheet

- Introduction to Surveys for Honors Thesis Writers

- PSR Introduction to the Survey Process

- Related Centers/Programs at Harvard

- General Survey Reference

- Institutional Review Boards

- Select Funding Opportunities

- Survey Analysis Software

- Professional Standards

- Professional Organizations

- Major Public Polls

- Survey Data Collections

- Major Longitudinal Surveys

- Other Links

Quantitative Research

Qualitative research.

- Free plan, no time limit

- Set up in minutes

- No credit card required

7+ Reasons to Use Surveys in Your Dissertation

Writing a dissertation is a serious milestone. Your degree depends on it, so it takes a lot of effort and time to figure out what direction to choose. Everything starts with the topic: you read background literature, consult with your supervisor and seek approval before you start writing the first draft. After that, you need to decide how you will collect the data that is supposed to contribute to the research field.

This is where it gets complicated. If you have never tried conducting primary research (i.e. working with human subjects), it can seem quite scary. Analyzing articles may sound like the safest and the coolest option. Yet, there might not be enough information for you to claim that your research is somehow novel.

To make sure it is, you might need to conduct primary research, and the survey method is the most widespread tool to do that. The number of advantages surveys present is huge. However, there are various perks depending on what approach you pursue. So, let’s go through all of them before you decide to pay for essay and order a dissertation that will go on and on about analyzing literature and nothing else except it.

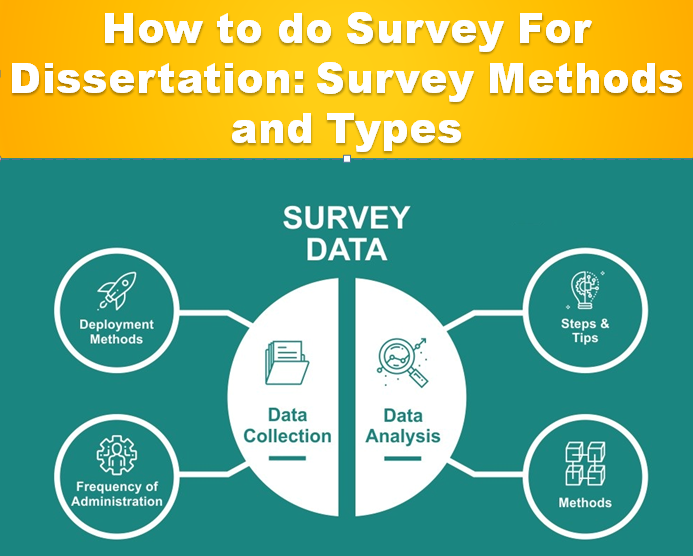

In the quantitative primary research, students have to calculate the data received from typical a, b, c, d questionnaires. The latter provides precise answers and helps prove or reject the formulated hypothesis. For the research to be legit, there are several stages to go through like:

- Discarding irrelevant or subjective questions/answers included in questionnaires.

- Setting criteria for credible answers.

- Composing an explanation of how you will manage ethical concerns (for participants and university committee).

However, all this is done to prevent issues in the future. Provided you have taken care of all the points above, you will get to enjoy the following benefits.

Data Collection Is Less Tedious

There are numerous services, like Survey Monkey, that the best write my essay services use. It can help you distribute your questionnaire among potential participants. These platforms simplify the data collection process. You don’t have to arrange calls or convince someone that they can safely share the information. Just upload the consent letter each participant has to sign and let the platform guide them further.

Data Analysis Is Fast

In quantitative analysis, all you have to take care of is mainly data entry. It requires focus and accuracy, but the rest can be done with the help of software. Whether it’s ordinary Excel or something like SPSS, you don’t have to reread loads of text. Just make sure you download the collected data from the platform correctly, remove irrelevant fields, and feed the rest to your computer.

Numbers Rule

Numbers don’t lie (unless you miscalculated them, of course). They give a clear answer: it’s either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Moreover, they leave more room for creating good visuals and making your paper less boring. Just make sure you explain the numbers properly and compare the results between various graphs and charts.

No Room For Subjectivity

A quantitative dissertation is mostly a technical paper. It’s not about creativity and your ability to impress like in admission essays students usually delegate to admission essay writing services to avoid babbling about things they deem senseless. It’s about following particular procedures. And there is also a less abstract analysis.

Qualitative-oriented surveys are about conducting full-fledged personal interviews, working with focus groups, or distributing open-ended questionnaires requiring short but unique answers. Let’s talk about what makes this approach worth trying!

First-Hand Experience

The ability to gain a unique perspective is what distinguishes interviews from other surveys. Close-ended questions may be too rigid and make participants omit a lot of information that might help the research. In an interview, you may also correct some of your questions, and add more details to them, thus improving the outcomes.

More Diverse and Honest Answers

When participants are limited by only several options, they might choose something they cannot fully relate to. So, there is no guarantee that the results will be authentic. Meanwhile, with open-ended questions, participants share a lot of details.

Sure, some of them may be less relevant to your topic, but the researcher gains a deeper understanding of the issues lying beneath the topic. Of course, all of it is guaranteed only if the researcher provides anonymity and a safe space for the interviewees to share their thoughts freely.

No Need For Complex Software

In contrast to quantitative analysis, here, you won’t have to use formulae and learn how to perform complex tests. You might not even need Excel, except for storing some data about your participants. However, no calculations will be needed, which is also a relief for those who are not used to working with such kind of data.

Both types of research have also other advantages:

- With surveys, you have more chances to fill the literature gap you’ve discovered.

- Primary research may not be quite easy, but it’s highly valued at the doctoral level of education.

- You receive a lot of new information and stay away from retelling literature that has been published before.

- Primary research is less boring.

However, there is a must-remember thing: not every supervisor or university committee approves of surveys and primary research in general. It depends on numerous aspects like topic and subject, the conditions of research, your approach to handling human subjects, etc.

It means that the methodology you are going to use should be approved by your professor first. Otherwise, you may have to discard some parts of your draft and lose time gathering data you won’t be able to use. So, take care and good luck!

7+ Reasons to Use Surveys in Your Dissertation FAQ

What are the benefits of using surveys in a dissertation, surveys can provide a large amount of data in a short amount of time, they are cost-effective and can allow for anonymity, they can reach a wide audience, and they can be used to obtain feedback from the participants., how can i ensure that my survey results are accurate, make sure to ask questions that are clear and concise and that there are no bias in the questions. make sure to have a good sample size and to have a response rate that is high enough to provide accurate results., how can i analyze the survey results, depending on the type of survey, there are various analysis techniques that can be used. these include descriptive statistics, inferential statistics, correlation analysis, and regression analysis., what are the limitations of surveys, surveys can be subject to sampling errors, response bias, and interviewer effects. they may also not be able to capture the full range of opinions and attitudes of the population., like what you see share with a friend..

Sarath Shyamson

Sarath Shyamson is the customer success person at BlockSurvey and also heads the outreach. He enjoys volunteering for the church choir.

Related articles

A/b testing calculator for statistical significance.

Anounymous Feedback: A How to guide

A Beginner's Guide to Non-Profit Marketing: Learn the Tips, Best practices and 7 best Marketing Strategies for your NPO

4 Major Benefits of Incorporating Online Survey Tools Into the Classroom

7 best demographic questions to enhance the quality of your survey

Best Practices for Ensuring Customer Data Security in Feedback Platforms

Confidential survey vs Anonymous survey - How to decide on that

Conjoint analysis: Definition and How it can be used in your surveys

Cross-Tabulation Analysis: How to use it in your surveys?

What is Data Masking- Why it is essential to maintain the anonymity of a survey

The Art of Effective Survey Questions Design: Everything You Need to Know to Survey Students the Right Way

Focus group survey Vs Online survey: How to choose the best method for your Market Research

How Employee Satisfaction Affects Company's Financial Performance

How to create an anonymous survey

How to identify if the survey is anonymous or not

A Simple and Easy guide to understand: When and How to use Surveys in Psychology

How to write a survey introduction that motivates respondents to fill it out

Survey and Question Design: How to Make a Perfect Statistical Survey

Matrix Questions: Definition and How to use it in survey

Maxdiff analysis: Definition, Example and How to use it

How to Maximize Data Collection Efficiency with Web 3.0 Surveys?

Empowering Prevention: Leveraging Online Surveys to Combat School Shootings

Optimizing Survey Results: Advanced Editing And Reporting Techniques

Enhancing Student Engagement and Learning with Online Surveys

Student survey questions that will provide valuable feedback

Preparing Students for the Future: The Role of Technology in Education

When It’s Best To Use Surveys For A Dissertation & How To Ensure Anonymity?

Which Pricing Strategy Should You Choose for Your Product? A Van Westendorp Analysis

Why Are Surveys Important for Financial Companies?

Want to create Anonymous survey in Facebook??- Know why you can't

- Master Your Homework

- Do My Homework

Writing Research Papers without Data

Data-driven research is becoming increasingly popular among scholars and researchers. However, it can be difficult for those without access to relevant data sources or the necessary technical knowhow to write a successful research paper without relying on any data. This article will discuss some of the ways that researchers can still effectively write quality papers when lacking appropriate datasets. It will provide an overview of common strategies used by experienced authors in situations where numerical evidence is not available, as well as considerations about how to make up for lost information from lack of quantitative results. Additionally, this article will offer advice on navigating through potential ethical concerns related to writing research papers without using data at all. Ultimately, it aims to demonstrate that even though collecting and analyzing data may add more depth and authority to one’s work, excellent scholarly works are possible with only qualitative evidence alone.

I. Introduction to Research Papers without Data

Ii. understanding the purpose of a paper without data, iii. evaluating alternative methods for writing a research paper with no data, iv. how to structure an effective argument in a non-data driven environment, v. determining what sources should be used and discussed within the scope of the project, vi. exploring potential implications of relying on other forms of evidence besides quantitative or qualitative datasets, vii. conclusion: examining current practices, opportunities, and challenges around writing research papers without data.

Research papers without data, or qualitative research papers, are not commonly seen in academic circles. However, these studies can still yield important insights and new understanding about a topic. Qualitative research is especially well-suited for exploring complex topics that have no simple answers.

- Nature of Qualitative Research: Rather than relying on numerical evidence to draw conclusions, qualitative researchers use techniques such as interviews and observation to gain an intimate understanding of their subject matter.

Qualitative research often involves intense work with the study participants – listening closely to what they say and observing their behavior – rather than analyzing numbers or statistics. The goal is usually more subjective than quantitative analysis; it seeks to provide an experiential narrative about how people think and feel in relation to a particular issue or phenomenon. By delving deeper into the motivations behind peoples’ actions, we may be able uncover truths that are not easily discernible from hard facts alone.

Gaining Clarity with a Research Paper without Data In any academic research project, the primary goal is to discover insights through data analysis. However, in some cases, it may be difficult or even impossible to obtain accurate data due to limitations on available resources. In such scenarios, how can researchers still gain meaningful results? A research paper without data provides an opportunity for students and academics alike who want to explore ideas and form hypotheses based on their existing knowledge.

The first step in writing a research paper without data is determining what purpose the study aims to serve: does it strive towards proving an existing point of view or exploring new possibilities? Does it seek only theoretical implications or practical applications as well? Once this is established, further considerations must include source material that informs the argument presented; whether evidence from other works should be included and if so how much relevance they hold; as well as details regarding potential arguments against the proposed idea. All these factors are integral in guiding authors when constructing papers which lack quantitative information.

By utilizing qualitative approaches instead of relying solely on numbers derived from empirical studies – for example conducting interviews with relevant experts – authors can formulate conclusions which rely heavily upon understanding contextually nuanced perspectives rather than measurable variables alone. Such processes also help create more engaging content where readers can visualize underlying themes better since less emphasis has been placed purely upon numerical figures and raw statistics.. When done right, presenting valuable findings sans figures helps present unique opinions pertaining complex topics clearly while allowing its audience develop informed opinions about those same subjects within reasonable limits – especially important when considering sensitive topics related but not restricted ethical debates around medical treatments or socio-political stances across different nations/cultures .

Exploring the Options

Writing a research paper without data can present quite a challenge for students. Depending on the context of the assignment, they have several options available to them. Unnumbered lists are an effective tool when comparing and contrasting various approaches:

- One method involves creative writing; this requires extensive knowledge of literary devices and rhetorical strategies.

- Another approach focuses on synthesis – essentially taking other people’s ideas and organizing them into new forms.

In the absence of data to support an argument, one must rely on knowledge and logical reasoning in order to effectively persuade. To structure a convincing non-data driven argument, consider the following components:

- Evidence: Your evidence should come from reliable sources that demonstrate credibility for your position. Personal anecdotes are powerful tools but it is important to supplement them with research material.

- Logic and Reasoning: A compelling argument requires a coherent chain of logic; be sure that each point flows logically into the next without any gaps or leaps in thought.

The quality of sources used within the scope of any project can be an essential factor in determining its success. As such, proper consideration must be given to both what kind and how many references should be included.

In general, academic research papers are preferred when conducting a thorough examination as they offer greater depth than other types of reference materials like blog posts or news articles. However, depending on the specifics of the inquiry being undertaken it may also benefit from consulting non-traditional sources such as those produced by industry insiders or governmental bodies.

- Ensure that all referenced material is reliable.

- Choose enough resources so that ample evidence is collected for accurate conclusions.

In this section, we will explore the implications of relying on evidence other than quantitative and qualitative datasets. Evidence-based research often requires complex analyses to draw meaningful conclusions; however, there are situations in which less structured forms of data can be just as useful for understanding an issue. To begin with, one example is using narrative accounts from interviews or surveys that offer insight into people’s experiences and opinions related to a particular topic.

Stories may provide information about participants’ values and beliefs that cannot easily be captured through statistical means. Narrative inquiry has been used in healthcare settings to understand patients’ perspectives regarding their health issues [1] . Additionally, it has also been used in organizational studies to gain insights about how organizations approach change management processes [2] . In both cases, stories allowed researchers to identify patterns not otherwise found by traditional methods such as questionnaire responses or focus groups.

- Visualizations:

Besides stories, visual materials like photographs have become increasingly popular tools for collecting evidence since they can capture details more quickly than text-based descriptions alone [3] . For instance, recent work demonstrates how photographs taken at regular intervals during archaeological excavations can reveal subtle features of artifacts that would have otherwise gone unnoticed due its small size or complexity.

[1]: Dixson M., & Harris S.(2019). Storytelling within Healthcare Practice Research – Challenges & Opportunities. Qualitative Health Research , 1335–1345 . https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1049732319859800

[2]: Morris T., Coetzer R., Arndt B., LeBaron C.. (2017). Organizational Change Management Strategies Through the Lens of Five Historical Cases Studied Through Narrative Inquiry . Academy Of Management Proceedings , 1–8 . doi : 10.5465/AMBPP171174250204743001801X

[3]: Ponsford J., Abbott E..(2015 ). A Comparison between Recording Archaeological Finds Using Photographic Records Compared With Traditional Drawing Methods — Case Study From Ulaanbaatar Urban Environment Project 2015 Fieldwork Season In Mongolia Journal Of Cultural Heritage 16 , 295–304

Examining Current Practices When it comes to writing research papers without data, current practices vary greatly. In some cases, authors focus on analyzing existing data to draw conclusions; in others, they synthesize theoretical material and concepts from multiple sources as a basis for their argument. Additionally, many approaches involve examining how the topic has been addressed previously by academics or practitioners in the field.

In recent years there have also been advancements in techniques that allow researchers to write effective research papers without relying on numerical data sets. For example, qualitative methods such as document analysis can be used instead of gathering primary quantitative information when conducting research into a particular phenomenon or issue. Similarly, virtual ethnography – which involves using digital technologies like social media platforms – is increasingly being utilized by scholars exploring certain topics from various angles.

- Opportunities

Writing an academic paper without data presents unique opportunities for innovative insights into complex issues and phenomena across disciplines and fields of study. By focusing solely on textual materials (including both traditional literature reviews and more modern forms of discourse), authors are able to establish relationships between theories while avoiding any potential biases associated with collecting physical evidence through surveys or experiments.

Additionally, those who take this approach enjoy greater flexibility when creating arguments since they don’t need to adhere strictly to pre-existing datasets or design strict methodologies before commencing their work – allowing them full creative license over how best represent key points within their research paper without data constraint limitations holding them back

To conclude, it is evident that writing a research paper without data can still be successful as long as the writer understands how to craft and organize their argument in an effective way. Though primary sources such as collected data provide invaluable support for claims, one may find success with critical analysis of existing literature if sufficient thought has been given to constructing the essay’s structure. Furthermore, using techniques like carefully crafted topic sentences and employing rhetorical strategies within one’s writing are essential components of any well-rounded paper that lacks quantitative evidence. As such, it is important to remember all these elements when attempting a research paper devoid of numerical or statistical information.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Survey research means collecting information about a group of people by asking them questions and analysing the results. To conduct an effective survey, follow these six steps:

- Determine who will participate in the survey

- Decide the type of survey (mail, online, or in-person)

- Design the survey questions and layout

- Distribute the survey

- Analyse the responses

- Write up the results

Surveys are a flexible method of data collection that can be used in many different types of research .

Table of contents

What are surveys used for, step 1: define the population and sample, step 2: decide on the type of survey, step 3: design the survey questions, step 4: distribute the survey and collect responses, step 5: analyse the survey results, step 6: write up the survey results, frequently asked questions about surveys.

Surveys are used as a method of gathering data in many different fields. They are a good choice when you want to find out about the characteristics, preferences, opinions, or beliefs of a group of people.

Common uses of survey research include:

- Social research: Investigating the experiences and characteristics of different social groups

- Market research: Finding out what customers think about products, services, and companies

- Health research: Collecting data from patients about symptoms and treatments

- Politics: Measuring public opinion about parties and policies

- Psychology: Researching personality traits, preferences, and behaviours

Surveys can be used in both cross-sectional studies , where you collect data just once, and longitudinal studies , where you survey the same sample several times over an extended period.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Before you start conducting survey research, you should already have a clear research question that defines what you want to find out. Based on this question, you need to determine exactly who you will target to participate in the survey.

Populations

The target population is the specific group of people that you want to find out about. This group can be very broad or relatively narrow. For example:

- The population of Brazil

- University students in the UK

- Second-generation immigrants in the Netherlands

- Customers of a specific company aged 18 to 24

- British transgender women over the age of 50

Your survey should aim to produce results that can be generalised to the whole population. That means you need to carefully define exactly who you want to draw conclusions about.

It’s rarely possible to survey the entire population of your research – it would be very difficult to get a response from every person in Brazil or every university student in the UK. Instead, you will usually survey a sample from the population.

The sample size depends on how big the population is. You can use an online sample calculator to work out how many responses you need.

There are many sampling methods that allow you to generalise to broad populations. In general, though, the sample should aim to be representative of the population as a whole. The larger and more representative your sample, the more valid your conclusions.

There are two main types of survey:

- A questionnaire , where a list of questions is distributed by post, online, or in person, and respondents fill it out themselves

- An interview , where the researcher asks a set of questions by phone or in person and records the responses

Which type you choose depends on the sample size and location, as well as the focus of the research.

Questionnaires

Sending out a paper survey by post is a common method of gathering demographic information (for example, in a government census of the population).

- You can easily access a large sample.

- You have some control over who is included in the sample (e.g., residents of a specific region).

- The response rate is often low.

Online surveys are a popular choice for students doing dissertation research , due to the low cost and flexibility of this method. There are many online tools available for constructing surveys, such as SurveyMonkey and Google Forms .

- You can quickly access a large sample without constraints on time or location.

- The data is easy to process and analyse.

- The anonymity and accessibility of online surveys mean you have less control over who responds.

If your research focuses on a specific location, you can distribute a written questionnaire to be completed by respondents on the spot. For example, you could approach the customers of a shopping centre or ask all students to complete a questionnaire at the end of a class.

- You can screen respondents to make sure only people in the target population are included in the sample.

- You can collect time- and location-specific data (e.g., the opinions of a shop’s weekday customers).

- The sample size will be smaller, so this method is less suitable for collecting data on broad populations.

Oral interviews are a useful method for smaller sample sizes. They allow you to gather more in-depth information on people’s opinions and preferences. You can conduct interviews by phone or in person.

- You have personal contact with respondents, so you know exactly who will be included in the sample in advance.

- You can clarify questions and ask for follow-up information when necessary.

- The lack of anonymity may cause respondents to answer less honestly, and there is more risk of researcher bias.

Like questionnaires, interviews can be used to collect quantitative data : the researcher records each response as a category or rating and statistically analyses the results. But they are more commonly used to collect qualitative data : the interviewees’ full responses are transcribed and analysed individually to gain a richer understanding of their opinions and feelings.

Next, you need to decide which questions you will ask and how you will ask them. It’s important to consider:

- The type of questions

- The content of the questions

- The phrasing of the questions

- The ordering and layout of the survey

Open-ended vs closed-ended questions

There are two main forms of survey questions: open-ended and closed-ended. Many surveys use a combination of both.

Closed-ended questions give the respondent a predetermined set of answers to choose from. A closed-ended question can include:

- A binary answer (e.g., yes/no or agree/disagree )

- A scale (e.g., a Likert scale with five points ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree )

- A list of options with a single answer possible (e.g., age categories)

- A list of options with multiple answers possible (e.g., leisure interests)

Closed-ended questions are best for quantitative research . They provide you with numerical data that can be statistically analysed to find patterns, trends, and correlations .

Open-ended questions are best for qualitative research. This type of question has no predetermined answers to choose from. Instead, the respondent answers in their own words.

Open questions are most common in interviews, but you can also use them in questionnaires. They are often useful as follow-up questions to ask for more detailed explanations of responses to the closed questions.

The content of the survey questions

To ensure the validity and reliability of your results, you need to carefully consider each question in the survey. All questions should be narrowly focused with enough context for the respondent to answer accurately. Avoid questions that are not directly relevant to the survey’s purpose.

When constructing closed-ended questions, ensure that the options cover all possibilities. If you include a list of options that isn’t exhaustive, you can add an ‘other’ field.

Phrasing the survey questions

In terms of language, the survey questions should be as clear and precise as possible. Tailor the questions to your target population, keeping in mind their level of knowledge of the topic.

Use language that respondents will easily understand, and avoid words with vague or ambiguous meanings. Make sure your questions are phrased neutrally, with no bias towards one answer or another.

Ordering the survey questions

The questions should be arranged in a logical order. Start with easy, non-sensitive, closed-ended questions that will encourage the respondent to continue.

If the survey covers several different topics or themes, group together related questions. You can divide a questionnaire into sections to help respondents understand what is being asked in each part.

If a question refers back to or depends on the answer to a previous question, they should be placed directly next to one another.

Before you start, create a clear plan for where, when, how, and with whom you will conduct the survey. Determine in advance how many responses you require and how you will gain access to the sample.

When you are satisfied that you have created a strong research design suitable for answering your research questions, you can conduct the survey through your method of choice – by post, online, or in person.

There are many methods of analysing the results of your survey. First you have to process the data, usually with the help of a computer program to sort all the responses. You should also cleanse the data by removing incomplete or incorrectly completed responses.

If you asked open-ended questions, you will have to code the responses by assigning labels to each response and organising them into categories or themes. You can also use more qualitative methods, such as thematic analysis , which is especially suitable for analysing interviews.

Statistical analysis is usually conducted using programs like SPSS or Stata. The same set of survey data can be subject to many analyses.

Finally, when you have collected and analysed all the necessary data, you will write it up as part of your thesis, dissertation , or research paper .

In the methodology section, you describe exactly how you conducted the survey. You should explain the types of questions you used, the sampling method, when and where the survey took place, and the response rate. You can include the full questionnaire as an appendix and refer to it in the text if relevant.

Then introduce the analysis by describing how you prepared the data and the statistical methods you used to analyse it. In the results section, you summarise the key results from your analysis.

A Likert scale is a rating scale that quantitatively assesses opinions, attitudes, or behaviours. It is made up of four or more questions that measure a single attitude or trait when response scores are combined.

To use a Likert scale in a survey , you present participants with Likert-type questions or statements, and a continuum of items, usually with five or seven possible responses, to capture their degree of agreement.

Individual Likert-type questions are generally considered ordinal data , because the items have clear rank order, but don’t have an even distribution.

Overall Likert scale scores are sometimes treated as interval data. These scores are considered to have directionality and even spacing between them.

The type of data determines what statistical tests you should use to analyse your data.

A questionnaire is a data collection tool or instrument, while a survey is an overarching research method that involves collecting and analysing data from people using questionnaires.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/surveys/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is a likert scale | guide & examples.

Dissertation Format and Submission

- Format Guidelines

- Dissertation Submission

- Getting Survey Permissions

- Help Videos

Instrument Permission documents

Instrument Permissions FAQ

Download a pdf of this faq , download the template permission letter, permissions to use and reproduce instruments in a thesis/dissertation frequently asked questions, why might i need permission to use an instrument in my thesis/dissertation.

- Determine whether you need permission

- Identify the copyright holder

- Ask for permission

- Keep a record

- What if I can't locate the copyright holder?

If you want to use surveys, questionnaires, interview questions, tests, measures, or other instruments created by other people, you are required to locate and follow usage permissions. The instrument may be protected by copyright and/or licensing restrictions.

Copyright Protection

Copyright provides authors of original creative work with limited control over the reproduction and distribution of that work. Under United States law, all original expressions that are “fixed in a tangible medium” are automatically protected by copyright at the time of their creation. In other words, it is not necessary to formally state a declaration of copyright, to use the © symbol, or to register with the United States Copyright Office.

Therefore, you must assume that any material you find is copyrighted, unless you have evidence otherwise. This is the case whether you find the instrument openly on the web, in a library database, or reproduced in a journal article. It is your legal and ethical responsibility to obtain permission to use, modify, and/or reproduce the instrument.

If you use and/or reproduce material in your thesis/dissertation beyond the limits outlined by the “fair use” doctrine, which allows for limited use of a work, without first gaining the copyright holder’s permission, you may be infringing copyright.

Licensing/Terms of Use

Some instruments are explicitly distributed under a license agreement or terms of use. Unlike copyright, which applies automatically, users must agree to these terms in order to use the instrument. In exchange for abiding by the terms, the copyright holder grants the licensee specific and limited rights, such as the right to use the instrument in scholarly research, or to reproduce the instrument in a publication.

When you ask a copyright holder for permission to use or reproduce an instrument, you are in effect asking for a license to do those things.

How do I know if I need permission to use instruments in my thesis/dissertation research? (Adapted from Hathcock & Crews )

Follow the four-step process below:

1. Determine whether you need permission

There are different levels of permissions for using an instrument:

a) No permission required

i. The copyright holder has explicitly licensed the use of instrument for any purpose, without requiring you to obtain permission.

ii. If you are only using a limited portion of the instrument, your use may be covered under the Fair Use Doctrine. See more here: https://uhcl.libguides.com/copyright/fairuse .

iii. If the instrument was developed by the federal government or under a government grant it may be in the public domain, and permission is therefore not required.

iv. If the document was created before 1977, it may be in the public domain, and permission is therefore not required. See the Stanford Public Domain Flowchart at https://fairuse.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/publicdomainflowchart.png .

b) Non-commercial/educational use: The copyright holder has licensed the instrument only for non-commercial research or educational purposes, without requiring you to obtain the permission of the copyright holder. Any other usage requires permission.

Sample Permission for Educational Use: