Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Literature Reviews

- Getting started

What is a literature review?

Why conduct a literature review, stages of a literature review, lit reviews: an overview (video), check out these books.

- Types of reviews

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- 6. Write the review

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

Definition: A literature review is a systematic examination and synthesis of existing scholarly research on a specific topic or subject.

Purpose: It serves to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge within a particular field.

Analysis: Involves critically evaluating and summarizing key findings, methodologies, and debates found in academic literature.

Identifying Gaps: Aims to pinpoint areas where there is a lack of research or unresolved questions, highlighting opportunities for further investigation.

Contextualization: Enables researchers to understand how their work fits into the broader academic conversation and contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

tl;dr A literature review critically examines and synthesizes existing scholarly research and publications on a specific topic to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge in the field.

What is a literature review NOT?

❌ An annotated bibliography

❌ Original research

❌ A summary

❌ Something to be conducted at the end of your research

❌ An opinion piece

❌ A chronological compilation of studies

The reason for conducting a literature review is to:

Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students

While this 9-minute video from NCSU is geared toward graduate students, it is useful for anyone conducting a literature review.

Writing the literature review: A practical guide

Available 3rd floor of Perkins

Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences

Available online!

So, you have to write a literature review: A guided workbook for engineers

Telling a research story: Writing a literature review

The literature review: Six steps to success

Systematic approaches to a successful literature review

Request from Duke Medical Center Library

Doing a systematic review: A student's guide

- Next: Types of reviews >>

- Last Updated: May 17, 2024 8:42 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/litreviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content in this section is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015), Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39: 103-103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

What's in the name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters . By Lynn Kysh from University of Southern California

Systematic review or meta-analysis?

A systematic review answers a defined research question by collecting and summarizing all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria.

A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of these studies.

Systematic reviews, just like other research articles, can be of varying quality. They are a significant piece of work (the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York estimates that a team will take 9-24 months), and to be useful to other researchers and practitioners they should have:

- clearly stated objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies

- assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (e.g. risk of bias)

- systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies

Not all systematic reviews contain meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review. More information on meta-analyses can be found in Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 9 .

A meta-analysis goes beyond critique and integration and conducts secondary statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies. It is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

An advantage of a meta-analysis is the ability to be completely objective in evaluating research findings. Not all topics, however, have sufficient research evidence to allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. In that case, an integrative review is an appropriate strategy.

Some of the content in this section is from Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: step by step guide created by Kate McAllister.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 4:07 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.udel.edu/researchmethods

- Meriam Library

SWRK 330 - Social Work Research Methods

- Literature Reviews and Empirical Research

- Databases and Search Tips

- Article Citations

- Scholarly Journal Evaulation

- Statistical Sources

- Books and eBooks

What is a Literature Review?

Empirical research.

- Annotated Bibliographies

A literature review summarizes and discusses previous publications on a topic.

It should also:

explore past research and its strengths and weaknesses.

be used to validate the target and methods you have chosen for your proposed research.

consist of books and scholarly journals that provide research examples of populations or settings similar to your own, as well as community resources to document the need for your proposed research.

The literature review does not present new primary scholarship.

be completed in the correct citation format requested by your professor (see the C itations Tab)

Access Purdue OWL's Social Work Literature Review Guidelines here .

Empirical Research is research that is based on experimentation or observation, i.e. Evidence. Such research is often conducted to answer a specific question or to test a hypothesis (educated guess).

How do you know if a study is empirical? Read the subheadings within the article, book, or report and look for a description of the research "methodology." Ask yourself: Could I recreate this study and test these results?

These are some key features to look for when identifying empirical research.

NOTE: Not all of these features will be in every empirical research article, some may be excluded, use this only as a guide.

- Statement of methodology

- Research questions are clear and measurable

- Individuals, group, subjects which are being studied are identified/defined

- Data is presented regarding the findings

- Controls or instruments such as surveys or tests were conducted

- There is a literature review

- There is discussion of the results included

- Citations/references are included

See also Empirical Research Guide

- << Previous: Citations

- Next: Annotated Bibliographies >>

- Last Updated: Feb 6, 2024 8:38 AM

- URL: https://libguides.csuchico.edu/SWRK330

Meriam Library | CSU, Chico

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Module 2 Chapter 3: What is Empirical Literature & Where can it be Found?

In Module 1, you read about the problem of pseudoscience. Here, we revisit the issue in addressing how to locate and assess scientific or empirical literature . In this chapter you will read about:

- distinguishing between what IS and IS NOT empirical literature

- how and where to locate empirical literature for understanding diverse populations, social work problems, and social phenomena.

Probably the most important take-home lesson from this chapter is that one source is not sufficient to being well-informed on a topic. It is important to locate multiple sources of information and to critically appraise the points of convergence and divergence in the information acquired from different sources. This is especially true in emerging and poorly understood topics, as well as in answering complex questions.

What Is Empirical Literature

Social workers often need to locate valid, reliable information concerning the dimensions of a population group or subgroup, a social work problem, or social phenomenon. They might also seek information about the way specific problems or resources are distributed among the populations encountered in professional practice. Or, social workers might be interested in finding out about the way that certain people experience an event or phenomenon. Empirical literature resources may provide answers to many of these types of social work questions. In addition, resources containing data regarding social indicators may also prove helpful. Social indicators are the “facts and figures” statistics that describe the social, economic, and psychological factors that have an impact on the well-being of a community or other population group.The United Nations (UN) and the World Health Organization (WHO) are examples of organizations that monitor social indicators at a global level: dimensions of population trends (size, composition, growth/loss), health status (physical, mental, behavioral, life expectancy, maternal and infant mortality, fertility/child-bearing, and diseases like HIV/AIDS), housing and quality of sanitation (water supply, waste disposal), education and literacy, and work/income/unemployment/economics, for example.

Three characteristics stand out in empirical literature compared to other types of information available on a topic of interest: systematic observation and methodology, objectivity, and transparency/replicability/reproducibility. Let’s look a little more closely at these three features.

Systematic Observation and Methodology. The hallmark of empiricism is “repeated or reinforced observation of the facts or phenomena” (Holosko, 2006, p. 6). In empirical literature, established research methodologies and procedures are systematically applied to answer the questions of interest.

Objectivity. Gathering “facts,” whatever they may be, drives the search for empirical evidence (Holosko, 2006). Authors of empirical literature are expected to report the facts as observed, whether or not these facts support the investigators’ original hypotheses. Research integrity demands that the information be provided in an objective manner, reducing sources of investigator bias to the greatest possible extent.

Transparency and Replicability/Reproducibility. Empirical literature is reported in such a manner that other investigators understand precisely what was done and what was found in a particular research study—to the extent that they could replicate the study to determine whether the findings are reproduced when repeated. The outcomes of an original and replication study may differ, but a reader could easily interpret the methods and procedures leading to each study’s findings.

What is NOT Empirical Literature

By now, it is probably obvious to you that literature based on “evidence” that is not developed in a systematic, objective, transparent manner is not empirical literature. On one hand, non-empirical types of professional literature may have great significance to social workers. For example, social work scholars may produce articles that are clearly identified as describing a new intervention or program without evaluative evidence, critiquing a policy or practice, or offering a tentative, untested theory about a phenomenon. These resources are useful in educating ourselves about possible issues or concerns. But, even if they are informed by evidence, they are not empirical literature. Here is a list of several sources of information that do not meet the standard of being called empirical literature:

- your course instructor’s lectures

- political statements

- advertisements

- newspapers & magazines (journalism)

- television news reports & analyses (journalism)

- many websites, Facebook postings, Twitter tweets, and blog postings

- the introductory literature review in an empirical article

You may be surprised to see the last two included in this list. Like the other sources of information listed, these sources also might lead you to look for evidence. But, they are not themselves sources of evidence. They may summarize existing evidence, but in the process of summarizing (like your instructor’s lectures), information is transformed, modified, reduced, condensed, and otherwise manipulated in such a manner that you may not see the entire, objective story. These are called secondary sources, as opposed to the original, primary source of evidence. In relying solely on secondary sources, you sacrifice your own critical appraisal and thinking about the original work—you are “buying” someone else’s interpretation and opinion about the original work, rather than developing your own interpretation and opinion. What if they got it wrong? How would you know if you did not examine the primary source for yourself? Consider the following as an example of “getting it wrong” being perpetuated.

Example: Bullying and School Shootings . One result of the heavily publicized April 1999 school shooting incident at Columbine High School (Colorado), was a heavy emphasis placed on bullying as a causal factor in these incidents (Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017), “creating a powerful master narrative about school shootings” (Raitanen, Sandberg, & Oksanen, 2017, p. 3). Naturally, with an identified cause, a great deal of effort was devoted to anti-bullying campaigns and interventions for enhancing resilience among youth who experience bullying. However important these strategies might be for promoting positive mental health, preventing poor mental health, and possibly preventing suicide among school-aged children and youth, it is a mistaken belief that this can prevent school shootings (Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017). Many times the accounts of the perpetrators having been bullied come from potentially inaccurate third-party accounts, rather than the perpetrators themselves; bullying was not involved in all instances of school shooting; a perpetrator’s perception of being bullied/persecuted are not necessarily accurate; many who experience severe bullying do not perpetrate these incidents; bullies are the least targeted shooting victims; perpetrators of the shooting incidents were often bullying others; and, bullying is only one of many important factors associated with perpetrating such an incident (Ioannou, Hammond, & Simpson, 2015; Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017; Newman &Fox, 2009; Raitanen, Sandberg, & Oksanen, 2017). While mass media reports deliver bullying as a means of explaining the inexplicable, the reality is not so simple: “The connection between bullying and school shootings is elusive” (Langman, 2014), and “the relationship between bullying and school shooting is, at best, tenuous” (Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017, p. 940). The point is, when a narrative becomes this publicly accepted, it is difficult to sort out truth and reality without going back to original sources of information and evidence.

What May or May Not Be Empirical Literature: Literature Reviews

Investigators typically engage in a review of existing literature as they develop their own research studies. The review informs them about where knowledge gaps exist, methods previously employed by other scholars, limitations of prior work, and previous scholars’ recommendations for directing future research. These reviews may appear as a published article, without new study data being reported (see Fields, Anderson, & Dabelko-Schoeny, 2014 for example). Or, the literature review may appear in the introduction to their own empirical study report. These literature reviews are not considered to be empirical evidence sources themselves, although they may be based on empirical evidence sources. One reason is that the authors of a literature review may or may not have engaged in a systematic search process, identifying a full, rich, multi-sided pool of evidence reports.

There is, however, a type of review that applies systematic methods and is, therefore, considered to be more strongly rooted in evidence: the systematic review .

Systematic review of literature. A systematic reviewis a type of literature report where established methods have been systematically applied, objectively, in locating and synthesizing a body of literature. The systematic review report is characterized by a great deal of transparency about the methods used and the decisions made in the review process, and are replicable. Thus, it meets the criteria for empirical literature: systematic observation and methodology, objectivity, and transparency/reproducibility. We will work a great deal more with systematic reviews in the second course, SWK 3402, since they are important tools for understanding interventions. They are somewhat less common, but not unheard of, in helping us understand diverse populations, social work problems, and social phenomena.

Locating Empirical Evidence

Social workers have available a wide array of tools and resources for locating empirical evidence in the literature. These can be organized into four general categories.

Journal Articles. A number of professional journals publish articles where investigators report on the results of their empirical studies. However, it is important to know how to distinguish between empirical and non-empirical manuscripts in these journals. A key indicator, though not the only one, involves a peer review process . Many professional journals require that manuscripts undergo a process of peer review before they are accepted for publication. This means that the authors’ work is shared with scholars who provide feedback to the journal editor as to the quality of the submitted manuscript. The editor then makes a decision based on the reviewers’ feedback:

- Accept as is

- Accept with minor revisions

- Request that a revision be resubmitted (no assurance of acceptance)

When a “revise and resubmit” decision is made, the piece will go back through the review process to determine if it is now acceptable for publication and that all of the reviewers’ concerns have been adequately addressed. Editors may also reject a manuscript because it is a poor fit for the journal, based on its mission and audience, rather than sending it for review consideration.

Indicators of journal relevance. Various journals are not equally relevant to every type of question being asked of the literature. Journals may overlap to a great extent in terms of the topics they might cover; in other words, a topic might appear in multiple different journals, depending on how the topic was being addressed. For example, articles that might help answer a question about the relationship between community poverty and violence exposure might appear in several different journals, some with a focus on poverty, others with a focus on violence, and still others on community development or public health. Journal titles are sometimes a good starting point but may not give a broad enough picture of what they cover in their contents.

In focusing a literature search, it also helps to review a journal’s mission and target audience. For example, at least four different journals focus specifically on poverty:

- Journal of Children & Poverty

- Journal of Poverty

- Journal of Poverty and Social Justice

- Poverty & Public Policy

Let’s look at an example using the Journal of Poverty and Social Justice . Information about this journal is located on the journal’s webpage: http://policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/journals/journal-of-poverty-and-social-justice . In the section headed “About the Journal” you can see that it is an internationally focused research journal, and that it addresses social justice issues in addition to poverty alone. The research articles are peer-reviewed (there appear to be non-empirical discussions published, as well). These descriptions about a journal are almost always available, sometimes listed as “scope” or “mission.” These descriptions also indicate the sponsorship of the journal—sponsorship may be institutional (a particular university or agency, such as Smith College Studies in Social Work ), a professional organization, such as the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) or the National Association of Social Work (NASW), or a publishing company (e.g., Taylor & Frances, Wiley, or Sage).

Indicators of journal caliber. Despite engaging in a peer review process, not all journals are equally rigorous. Some journals have very high rejection rates, meaning that many submitted manuscripts are rejected; others have fairly high acceptance rates, meaning that relatively few manuscripts are rejected. This is not necessarily the best indicator of quality, however, since newer journals may not be sufficiently familiar to authors with high quality manuscripts and some journals are very specific in terms of what they publish. Another index that is sometimes used is the journal’s impact factor . Impact factor is a quantitative number indicative of how often articles published in the journal are cited in the reference list of other journal articles—the statistic is calculated as the number of times on average each article published in a particular year were cited divided by the number of articles published (the number that could be cited). For example, the impact factor for the Journal of Poverty and Social Justice in our list above was 0.70 in 2017, and for the Journal of Poverty was 0.30. These are relatively low figures compared to a journal like the New England Journal of Medicine with an impact factor of 59.56! This means that articles published in that journal were, on average, cited more than 59 times in the next year or two.

Impact factors are not necessarily the best indicator of caliber, however, since many strong journals are geared toward practitioners rather than scholars, so they are less likely to be cited by other scholars but may have a large impact on a large readership. This may be the case for a journal like the one titled Social Work, the official journal of the National Association of Social Workers. It is distributed free to all members: over 120,000 practitioners, educators, and students of social work world-wide. The journal has a recent impact factor of.790. The journals with social work relevant content have impact factors in the range of 1.0 to 3.0 according to Scimago Journal & Country Rank (SJR), particularly when they are interdisciplinary journals (for example, Child Development , Journal of Marriage and Family , Child Abuse and Neglect , Child Maltreatmen t, Social Service Review , and British Journal of Social Work ). Once upon a time, a reader could locate different indexes comparing the “quality” of social work-related journals. However, the concept of “quality” is difficult to systematically define. These indexes have mostly been replaced by impact ratings, which are not necessarily the best, most robust indicators on which to rely in assessing journal quality. For example, new journals addressing cutting edge topics have not been around long enough to have been evaluated using this particular tool, and it takes a few years for articles to begin to be cited in other, later publications.

Beware of pseudo-, illegitimate, misleading, deceptive, and suspicious journals . Another side effect of living in the Age of Information is that almost anyone can circulate almost anything and call it whatever they wish. This goes for “journal” publications, as well. With the advent of open-access publishing in recent years (electronic resources available without subscription), we have seen an explosion of what are called predatory or junk journals . These are publications calling themselves journals, often with titles very similar to legitimate publications and often with fake editorial boards. These “publications” lack the integrity of legitimate journals. This caution is reminiscent of the discussions earlier in the course about pseudoscience and “snake oil” sales. The predatory nature of many apparent information dissemination outlets has to do with how scientists and scholars may be fooled into submitting their work, often paying to have their work peer-reviewed and published. There exists a “thriving black-market economy of publishing scams,” and at least two “journal blacklists” exist to help identify and avoid these scam journals (Anderson, 2017).

This issue is important to information consumers, because it creates a challenge in terms of identifying legitimate sources and publications. The challenge is particularly important to address when information from on-line, open-access journals is being considered. Open-access is not necessarily a poor choice—legitimate scientists may pay sizeable fees to legitimate publishers to make their work freely available and accessible as open-access resources. On-line access is also not necessarily a poor choice—legitimate publishers often make articles available on-line to provide timely access to the content, especially when publishing the article in hard copy will be delayed by months or even a year or more. On the other hand, stating that a journal engages in a peer-review process is no guarantee of quality—this claim may or may not be truthful. Pseudo- and junk journals may engage in some quality control practices, but may lack attention to important quality control processes, such as managing conflict of interest, reviewing content for objectivity or quality of the research conducted, or otherwise failing to adhere to industry standards (Laine & Winker, 2017).

One resource designed to assist with the process of deciphering legitimacy is the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ). The DOAJ is not a comprehensive listing of all possible legitimate open-access journals, and does not guarantee quality, but it does help identify legitimate sources of information that are openly accessible and meet basic legitimacy criteria. It also is about open-access journals, not the many journals published in hard copy.

An additional caution: Search for article corrections. Despite all of the careful manuscript review and editing, sometimes an error appears in a published article. Most journals have a practice of publishing corrections in future issues. When you locate an article, it is helpful to also search for updates. Here is an example where data presented in an article’s original tables were erroneous, and a correction appeared in a later issue.

- Marchant, A., Hawton, K., Stewart A., Montgomery, P., Singaravelu, V., Lloyd, K., Purdy, N., Daine, K., & John, A. (2017). A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: The good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One, 12(8): e0181722. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5558917/

- Marchant, A., Hawton, K., Stewart A., Montgomery, P., Singaravelu, V., Lloyd, K., Purdy, N., Daine, K., & John, A. (2018).Correction—A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: The good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One, 13(3): e0193937. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0193937

Search Tools. In this age of information, it is all too easy to find items—the problem lies in sifting, sorting, and managing the vast numbers of items that can be found. For example, a simple Google® search for the topic “community poverty and violence” resulted in about 15,600,000 results! As a means of simplifying the process of searching for journal articles on a specific topic, a variety of helpful tools have emerged. One type of search tool has previously applied a filtering process for you: abstracting and indexing databases . These resources provide the user with the results of a search to which records have already passed through one or more filters. For example, PsycINFO is managed by the American Psychological Association and is devoted to peer-reviewed literature in behavioral science. It contains almost 4.5 million records and is growing every month. However, it may not be available to users who are not affiliated with a university library. Conducting a basic search for our topic of “community poverty and violence” in PsychINFO returned 1,119 articles. Still a large number, but far more manageable. Additional filters can be applied, such as limiting the range in publication dates, selecting only peer reviewed items, limiting the language of the published piece (English only, for example), and specified types of documents (either chapters, dissertations, or journal articles only, for example). Adding the filters for English, peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2010 and 2017 resulted in 346 documents being identified.

Just as was the case with journals, not all abstracting and indexing databases are equivalent. There may be overlap between them, but none is guaranteed to identify all relevant pieces of literature. Here are some examples to consider, depending on the nature of the questions asked of the literature:

- Academic Search Complete—multidisciplinary index of 9,300 peer-reviewed journals

- AgeLine—multidisciplinary index of aging-related content for over 600 journals

- Campbell Collaboration—systematic reviews in education, crime and justice, social welfare, international development

- Google Scholar—broad search tool for scholarly literature across many disciplines

- MEDLINE/ PubMed—National Library of medicine, access to over 15 million citations

- Oxford Bibliographies—annotated bibliographies, each is discipline specific (e.g., psychology, childhood studies, criminology, social work, sociology)

- PsycINFO/PsycLIT—international literature on material relevant to psychology and related disciplines

- SocINDEX—publications in sociology

- Social Sciences Abstracts—multiple disciplines

- Social Work Abstracts—many areas of social work are covered

- Web of Science—a “meta” search tool that searches other search tools, multiple disciplines

Placing our search for information about “community violence and poverty” into the Social Work Abstracts tool with no additional filters resulted in a manageable 54-item list. Finally, abstracting and indexing databases are another way to determine journal legitimacy: if a journal is indexed in a one of these systems, it is likely a legitimate journal. However, the converse is not necessarily true: if a journal is not indexed does not mean it is an illegitimate or pseudo-journal.

Government Sources. A great deal of information is gathered, analyzed, and disseminated by various governmental branches at the international, national, state, regional, county, and city level. Searching websites that end in.gov is one way to identify this type of information, often presented in articles, news briefs, and statistical reports. These government sources gather information in two ways: they fund external investigations through grants and contracts and they conduct research internally, through their own investigators. Here are some examples to consider, depending on the nature of the topic for which information is sought:

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) at https://www.ahrq.gov/

- Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) at https://www.bjs.gov/

- Census Bureau at https://www.census.gov

- Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report of the CDC (MMWR-CDC) at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/index.html

- Child Welfare Information Gateway at https://www.childwelfare.gov

- Children’s Bureau/Administration for Children & Families at https://www.acf.hhs.gov

- Forum on Child and Family Statistics at https://www.childstats.gov

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) at https://www.nih.gov , including (not limited to):

- National Institute on Aging (NIA at https://www.nia.nih.gov

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) at https://www.niaaa.nih.gov

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) at https://www.nichd.nih.gov

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at https://www.nida.nih.gov

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at https://www.niehs.nih.gov

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) at https://www.nimh.nih.gov

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities at https://www.nimhd.nih.gov

- National Institute of Justice (NIJ) at https://www.nij.gov

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) at https://www.samhsa.gov/

- United States Agency for International Development at https://usaid.gov

Each state and many counties or cities have similar data sources and analysis reports available, such as Ohio Department of Health at https://www.odh.ohio.gov/healthstats/dataandstats.aspx and Franklin County at https://statisticalatlas.com/county/Ohio/Franklin-County/Overview . Data are available from international/global resources (e.g., United Nations and World Health Organization), as well.

Other Sources. The Health and Medicine Division (HMD) of the National Academies—previously the Institute of Medicine (IOM)—is a nonprofit institution that aims to provide government and private sector policy and other decision makers with objective analysis and advice for making informed health decisions. For example, in 2018 they produced reports on topics in substance use and mental health concerning the intersection of opioid use disorder and infectious disease, the legal implications of emerging neurotechnologies, and a global agenda concerning the identification and prevention of violence (see http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Global/Topics/Substance-Abuse-Mental-Health.aspx ). The exciting aspect of this resource is that it addresses many topics that are current concerns because they are hoping to help inform emerging policy. The caution to consider with this resource is the evidence is often still emerging, as well.

Numerous “think tank” organizations exist, each with a specific mission. For example, the Rand Corporation is a nonprofit organization offering research and analysis to address global issues since 1948. The institution’s mission is to help improve policy and decision making “to help individuals, families, and communities throughout the world be safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous,” addressing issues of energy, education, health care, justice, the environment, international affairs, and national security (https://www.rand.org/about/history.html). And, for example, the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation is a philanthropic organization supporting research and research dissemination concerning health issues facing the United States. The foundation works to build a culture of health across systems of care (not only medical care) and communities (https://www.rwjf.org).

While many of these have a great deal of helpful evidence to share, they also may have a strong political bias. Objectivity is often lacking in what information these organizations provide: they provide evidence to support certain points of view. That is their purpose—to provide ideas on specific problems, many of which have a political component. Think tanks “are constantly researching solutions to a variety of the world’s problems, and arguing, advocating, and lobbying for policy changes at local, state, and federal levels” (quoted from https://thebestschools.org/features/most-influential-think-tanks/ ). Helpful information about what this one source identified as the 50 most influential U.S. think tanks includes identifying each think tank’s political orientation. For example, The Heritage Foundation is identified as conservative, whereas Human Rights Watch is identified as liberal.

While not the same as think tanks, many mission-driven organizations also sponsor or report on research, as well. For example, the National Association for Children of Alcoholics (NACOA) in the United States is a registered nonprofit organization. Its mission, along with other partnering organizations, private-sector groups, and federal agencies, is to promote policy and program development in research, prevention and treatment to provide information to, for, and about children of alcoholics (of all ages). Based on this mission, the organization supports knowledge development and information gathering on the topic and disseminates information that serves the needs of this population. While this is a worthwhile mission, there is no guarantee that the information meets the criteria for evidence with which we have been working. Evidence reported by think tank and mission-driven sources must be utilized with a great deal of caution and critical analysis!

In many instances an empirical report has not appeared in the published literature, but in the form of a technical or final report to the agency or program providing the funding for the research that was conducted. One such example is presented by a team of investigators funded by the National Institute of Justice to evaluate a program for training professionals to collect strong forensic evidence in instances of sexual assault (Patterson, Resko, Pierce-Weeks, & Campbell, 2014): https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/247081.pdf . Investigators may serve in the capacity of consultant to agencies, programs, or institutions, and provide empirical evidence to inform activities and planning. One such example is presented by Maguire-Jack (2014) as a report to a state’s child maltreatment prevention board: https://preventionboard.wi.gov/Documents/InvestmentInPreventionPrograming_Final.pdf .

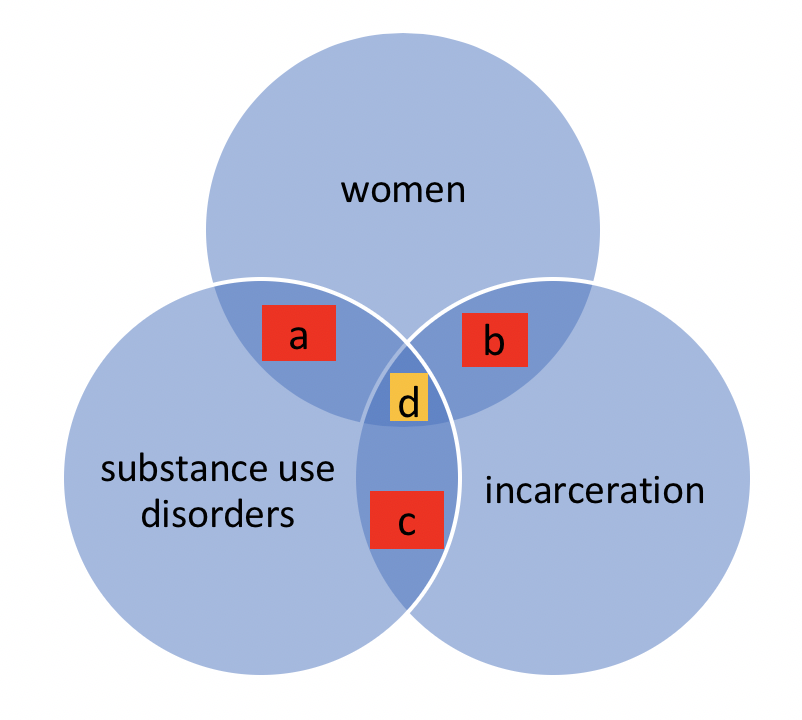

When Direct Answers to Questions Cannot Be Found. Sometimes social workers are interested in finding answers to complex questions or questions related to an emerging, not-yet-understood topic. This does not mean giving up on empirical literature. Instead, it requires a bit of creativity in approaching the literature. A Venn diagram might help explain this process. Consider a scenario where a social worker wishes to locate literature to answer a question concerning issues of intersectionality. Intersectionality is a social justice term applied to situations where multiple categorizations or classifications come together to create overlapping, interconnected, or multiplied disadvantage. For example, women with a substance use disorder and who have been incarcerated face a triple threat in terms of successful treatment for a substance use disorder: intersectionality exists between being a woman, having a substance use disorder, and having been in jail or prison. After searching the literature, little or no empirical evidence might have been located on this specific triple-threat topic. Instead, the social worker will need to seek literature on each of the threats individually, and possibly will find literature on pairs of topics (see Figure 3-1). There exists some literature about women’s outcomes for treatment of a substance use disorder (a), some literature about women during and following incarceration (b), and some literature about substance use disorders and incarceration (c). Despite not having a direct line on the center of the intersecting spheres of literature (d), the social worker can develop at least a partial picture based on the overlapping literatures.

Figure 3-1. Venn diagram of intersecting literature sets.

Take a moment to complete the following activity. For each statement about empirical literature, decide if it is true or false.

Social Work 3401 Coursebook Copyright © by Dr. Audrey Begun is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Penn State University Libraries

Empirical research in the social sciences and education.

- What is Empirical Research and How to Read It

- Finding Empirical Research in Library Databases

- Designing Empirical Research

- Ethics, Cultural Responsiveness, and Anti-Racism in Research

- Citing, Writing, and Presenting Your Work

Contact the Librarian at your campus for more help!

Introduction: What is Empirical Research?

Empirical research is based on observed and measured phenomena and derives knowledge from actual experience rather than from theory or belief.

How do you know if a study is empirical? Read the subheadings within the article, book, or report and look for a description of the research "methodology." Ask yourself: Could I recreate this study and test these results?

Key characteristics to look for:

- Specific research questions to be answered

- Definition of the population, behavior, or phenomena being studied

- Description of the process used to study this population or phenomena, including selection criteria, controls, and testing instruments (such as surveys)

Another hint: some scholarly journals use a specific layout, called the "IMRaD" format, to communicate empirical research findings. Such articles typically have 4 components:

- Introduction : sometimes called "literature review" -- what is currently known about the topic -- usually includes a theoretical framework and/or discussion of previous studies

- Methodology: sometimes called "research design" -- how to recreate the study -- usually describes the population, research process, and analytical tools used in the present study

- Results : sometimes called "findings" -- what was learned through the study -- usually appears as statistical data or as substantial quotations from research participants

- Discussion : sometimes called "conclusion" or "implications" -- why the study is important -- usually describes how the research results influence professional practices or future studies

Reading and Evaluating Scholarly Materials

Reading research can be a challenge. However, the tutorials and videos below can help. They explain what scholarly articles look like, how to read them, and how to evaluate them:

- CRAAP Checklist A frequently-used checklist that helps you examine the currency, relevance, authority, accuracy, and purpose of an information source.

- IF I APPLY A newer model of evaluating sources which encourages you to think about your own biases as a reader, as well as concerns about the item you are reading.

- Credo Video: How to Read Scholarly Materials (4 min.)

- Credo Tutorial: How to Read Scholarly Materials

- Credo Tutorial: Evaluating Information

- Credo Video: Evaluating Statistics (4 min.)

- Next: Finding Empirical Research in Library Databases >>

- Last Updated: Feb 18, 2024 8:33 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/emp

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as you go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface with the option to save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.