Having women in leadership roles is more important than ever, here's why

Finland's Prime Minister Sanna Marin (second from right), Minister of Education Li Andersson, Minister of Finance Katri Kulmuni and Minister of Interior Maria Ohisalo Image: REUTERS

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Leanne Kemp

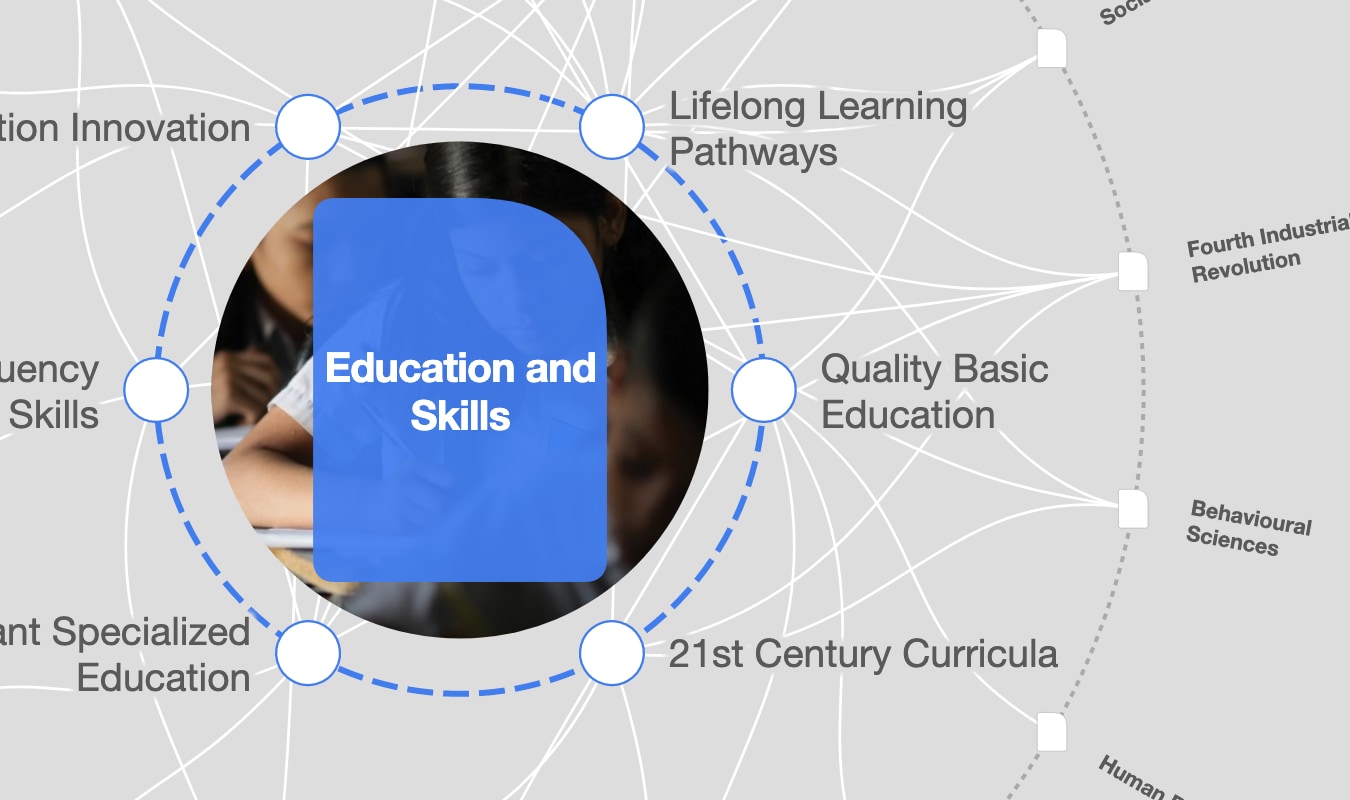

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Education, Gender and Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, education, gender and work.

- Since 2015 the number of women in senior leadership in business has grown and diversity in leadership is good for business;

- Beyond business, female leaders from across generations are working together to find new solutions to the world's biggest problems;

- The tech sector must attract more women to unlock the potential of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and ensure technology is developed from a balanced perspective.

In an ideal world, it shouldn’t matter whether there’s a woman running the IMF, Microsoft or the Democratic Party. Does an SME owner or tech start-up care that it’s a woman who makes finance more accessible? If a miner, factory worker or fisherman gets a better share of the profits and can send his or her children to school, are they bothered that a woman made it possible?

Bush fires, burst riverbanks, melting icecaps, fatbergs, plastic islands and species extinction: none of these considers the sex of the perpetrators or decision-makers. Yet, encouraging more women into leadership positions remains critical in our era and given the fast-approaching challenges of the future.

Have you read?

5 ways to break down the barriers for women to access leadership roles, these are the best countries for women to work in, a woman would have to be born in the year 2255 to get equal pay at work.

The overall number of women in top business roles is still painfully low – only 5% of CEOs of major corporations in the US are women – but there are reasons for optimism. Since 2015 the number of women in senior leadership has grown, particularly in the C-suite where the representation of women has increased from 17% to 21% . Today, 44% of companies have three or more women in their C-suite, up from 29% of companies in 2015. Corporate America scores much lower than France or Norway, where businesses average more than 40% female representation on a board of directors .

Diversity in leadership is good for business. For example, a Harvard Business School report on the male-dominated venture capital industry found that “the more similar the investment partners, the lower their investments’ performance”. In fact, firms that increased their proportion of female partner hires by 10% saw, on average, a 1.5% spike in overall fund returns each year and had 9.7% more profitable exits.

Evolving job needs are empowering women and levelling the playing field. The new service economy doesn’t rely on physical strength but skills that come easily to women, such as determination, attention to detail and measured thinking. The female brain is naturally wired for long-term strategic vision and community building.

The emergence of female leaders can become a centrifugal force for good in the world. For the first time, we’re seeing examples of female leaders emerging from across the generations to cross-weave their knowledge and drive for change. If we take the environment and climate as an example, someone as experienced and respected as Jane Goodall is standing alongside teenage activists like Greta Thunberg. Importantly, there are now ambitious and capable women running influential organizations who can activate physical change through technology and policy. The recent progress with the circular economy and blockchain is a prime example.

There’s nothing inherently masculine about blockchain, artificial intelligence (AI) or machine learning; computers are androgynous by nature. That said, the tech sector remains heavily dominated by men. According to the World Economic Forum , the greatest challenge preventing the economic gender gap from closing is women’s under-representation in emerging roles. In cloud computing, just 12% of professionals are women; in engineering and Data and AI, the numbers are 15% and 26% respectively. Unless the sector can balance the ledger by making roles attractive to women, then we risk missing out on the full potential of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Organizations need to ensure there are sufficient rungs on the ladder to help women climb into management positions. We need to be open-minded enough to bring in female leaders from other industries, who don’t have a tech background. We need to work closely with schools and universities to win the argument that tech isn’t just a male career path. Technology also has a role to play – and responsibility – in promoting diversity in the workplace, given its ability to change working relationships, encourage transparency and connect people around the world. In a period of constant flux, organizations that prioritize a diverse and inclusive culture will be better placed to solve the problems of the future.

Research by Deloitte suggests companies with an inclusive culture are six times more likely to be innovative. By staying ahead of changes, they are twice as likely to hit or better financial targets. This means providing female mentors and role models, demonstrating trust (rather than talking about it), creating an environment that encourages collaboration, using technology to break barriers and sourcing innovation openly.

Women can lead our sector forward too. Now that technology is all-pervasive, the traditional sector lines have become blurred. Brands that cling to the old structures will find themselves overtaken and left behind. This is when women’s ability to empathize and seek compromise becomes a powerful asset. If technology is supposed to service the whole of humanity, the big decisions need to be taken from a balanced perspective.

More women are now being elected to legislatures across the world: women hold 25.2% of parliamentary lower-house seats and 21.2% of ministerial positions, compared to 24.1% and 19% respectively last year. While there is a long way to go, improving political empowerment for women typically corresponds with increased numbers of women in senior roles in the labour market.

In my own Queensland, a women-led government is taking big steps forward on behalf of the state economy. They’ve shown a real desire to listen to experts in the wider world of business. We’re seeing women from other fields, such as ex-Olympic athletes, joining the political arena. Yet, for those countries and political parties – and corporations for that matter – which have never appointed a woman to the top position, the suspicion that the system isn’t fair and that the glass ceilings are unbreakable grows with every election.

The survival of the planet requires new thinking and strategies. We are in a pitched battle between the present array of resources and attitudes and the future struggling to be born. Women get it; young people get it. They are creating a whole different mindset.

Ultimately, the problems we face are not technological, but human – the human system is broken. People should always be appointed on merit and the electorate must decide, but more still needs to be done to give all women the best possible chance of rising to the top. If that happens, then I’ll be the first to say that who’s in charge doesn’t matter a jot.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

This is how AI can empower women and achieve gender equality, according to the founder of Girls Who Code and Moms First

Kate Whiting

May 14, 2024

Here's how rising air pollution threatens millions in the US

5 conditions that highlight the women’s health gap

May 3, 2024

It’s financial literacy month: From schools to the workplace, let's take action

Annamaria Lusardi and Andrea Sticha

April 24, 2024

Bridging the financial literacy gender gap: Here are 5 digital inclusion projects making a difference

Claude Dyer and Vidhi Bhatia

April 18, 2024

Weekend reads: Climate inaction and human rights, the space economy, diversifying genetic data, and more

Julie Masiga

April 12, 2024

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Get New Issue Alerts

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences

Women, Power & Leadership

Many more women provide visible leadership today than ever before. Opening up higher education for women and winning the battle for suffrage brought new opportunities, along with widespread availability of labor-saving devices and the discovery and legalization of reliable, safe methods of birth control. Despite these developments, women ambitious for leadership still face formidable obstacles: primary if not sole responsibility for childcare and homemaking; the lack of family-friendly policies in most workplaces; gender stereotypes perpetuated in popular culture; and in some parts of the world, laws and practices that deny women education or opportunities outside the home. Some observers believe that only a few women want to hold significant, demanding leadership posts; but there is ample evidence on the other side of this debate, some of it documented in this volume. Historic tensions between feminism and power remain to be resolved by creative theorizing and shrewd, strategic activism. We cannot know whether women are “naturally” interested in top leadership posts until they can attain such positions without making personal and family sacrifices radically disproportionate to those faced by men.

Nannerl O. Keohane , a Fellow of the American Academy since 1991, is a political philosopher and university administrator who served as President of Wellesley College and Duke University. She is currently affiliated with the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University and is a Visiting Scholar at the McCoy Family Center for Ethics in Society at Stanford University. Her books include Philosophy and the State in France: The Renaissance to the Enlightenment (1980), Higher Ground: Ethics and Leadership in the Modern University (2006), and Thinking about Leadership (2010). She is a member of the Board of Directors of the American Academy.

One of the most dramatic changes in recent decades has been the increasing prominence of women in positions of leadership. Many more women are providing leadership in government, business, higher education, nonprofit ventures, and other areas of life, in many more countries of the world, than would ever have been true in the past. This essay addresses four aspects of this development.

I will note the kinds of leadership women have routinely provided, and list factors that help explain why this pattern has changed dramatically in the past half century. I will mention some of the obstacles that still block the path for women in leadership. Then I will ask how ambitious women generally are for leadership, and discuss the fraught relationship between feminism and power, before concluding with a brief look at the future that might lie ahead.

As we approach this subject, we need to understand what we mean by “leadership.” I use the following definition: “Leaders define or clarify goals for a group of individuals and bring together the energies of members of that group to pursue those goals.” 1 This conception is deliberately broad, designed to capture various types of leadership, in various groups, not just the work of leaders who hold the most visible offices in a large society.

A leader can define or clarify goals by issuing a memo or an executive order, an edict or a fatwa or a tweet, by passing a law, barking a command, or presenting an interesting idea in a meeting of colleagues. Leaders can mobilize people’s energies in ways that range from subtle, quiet persuasion to the coercive threat or the use of deadly force. Sometimes a charismatic leader such as Martin Luther King Jr. can define goals and mobilize energies through rhetoric and the power of example.

It is also helpful to distinguish leadership from two closely related concepts: power and authority.

All leaders have some measure of power, in the sense of influencing or determining priorities for other individuals. But leadership cannot be a synonym for holding power. Power is often defined in the straightforward way suggested by political scientist Robert Dahl: “ A has power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do.” 2 A bully or an assailant with a gun wields power in this sense, but it would not be appropriate to call such a person a “leader.”

Leadership often involves exercising authority with the formal legitimacy of a position in a governmental structure or high office in a large organization. Holding authority in these ways provides clear opportunities for leadership. Yet many men and women we would want to call leaders are not in positions of authority, and not everyone in a formal office provides leadership. As John Gardner, author of several valuable books on leadership, noted, “We have all occasionally encountered top persons who couldn’t lead a squad of seven-year-olds to the ice cream counter.” 3

We can think of leadership as a spectrum, in terms of both visibility and the power the leader wields. On one end of the spectrum, we have the most visible: authoritative leaders like the president of the United States or the prime minister of the United Kingdom, or a dictator such as Hitler or Qaddafi. At the opposite end of the spectrum is casual, low-key leadership found in countless situations every day around the world, leadership that can make a significant difference to the individuals whose lives are touched by it.

Over the centuries, the first kind–the out-in-front, authoritative leadership–has generally been exhibited by men. Some men in positions of great authority, including Nelson Mandela, have chosen a strategy of “leading from behind”; more often, however, top leaders have been quite visible in their exercise of power. Women (as well as some men) have provided casual, low-key leadership behind the scenes. But this pattern has been changing, as more women have taken up opportunities for visible, authoritative leadership.

Across all the centuries of which we have any record, women have been largely absent from positions of formal authority. Such posts, with a few exceptions, were routinely held by men. Women have therefore lacked opportunities to exercise leadership in the most visible public settings. And as both cause and consequence of this fact, leadership has been closely associated with masculinity. In some parts of the world this assumption is still dominant: even in what we think of as the most advanced countries, there are people who think that men are “natural leaders,” and women are meant to follow them.

Yet despite this stubborn linkage between leadership and maleness, some women in almost every society have proved themselves capable of providing strong, visible leadership. Women exercised formal public authority when dynasty or marriage-lines trumped gender, so that Elizabeth I of England or Catherine the Great of Russia could rule as monarch. There are cultures in which wise women are regularly consulted, either as individuals or as members of the council of the tribe. All-female institutions are especially auspicious for women as leaders, including convents, girls’ schools, and women’s colleges, where women have often held authoritative posts.

Women have led in situations where men are temporarily absent: in wartime when the men are away fighting, or in a community like Nantucket in the eighteenth or nineteenth century, where most of the men were whaling in distant seas for years at a time. Women have provided visible leadership in movements for social betterment, including the prohibition and settlement house campaigns of the late nineteenth century and the battle for women’s suffrage. “First ladies” have leveraged their access to power to promote important causes. The impressive accomplishments of Jane Addams and Eleanor Roosevelt stand as prime examples of female leadership. Women have been leaders in family businesses in many different settings. And countless women across history have provided leadership in education, religious activities, care for the sick and wounded, cultural affairs, and charity for the poor.

So that’s a rough, impressionistic survey of the leadership women have exercised in the past: a very few “out front,” as queens or abbesses or heads of school, with many providing more informal leadership in smaller communities or behind the scenes.

This picture has changed dramatically in the past half-century. Many more women today hold authoritative posts, as prime ministers, heads of universities, CEOs of corporations, presidents of nonprofit organizations, and bishops in Protestant denominations. Why has this happened in the past few decades, rather than sooner, or later, or never?

As we ponder this question, we must also note that the changes have proceeded unevenly. It is still unusual for a woman to be CEO of a major public corporation or the president of a country with direct elections for the head of government, as distinct from parliamentary systems. Women’s leadership in religious organizations depends on the doctrines of the religion or sect and the influences of the surrounding society on how these doctrines are interpreted. We will look at some of the barriers blocking change in these and other areas.

And finally, are women as ambitious for leadership as men, or are there systematic differences between the two sexes in the appetite for gaining and using power? Can tensions between the core concepts of feminism and the wielding of power help us understand these issues?

In the past half-century, fifty-six women have served as president or prime minister of their countries. 4 In the United States, women hold office as senators and congresswomen, governors and mayors, cabinet officers and university presidents, heads of foundations and social service agencies, rabbis, generals, and principal investigators. Women have been the CEOs of GM, IBM, Yahoo, and Pepsi-Cola. There are women judges sitting at all levels of the court system, and women leaders in several prominent international organizations.

In the United States, the unprecedented numbers of women candidates in the 2018 midterm elections and the 2019 Democratic presidential primaries are striking examples of women tackling the long-standing identification of leadership with masculinity. One hundred and seventeen women won office in 2018, including ninety-six members of the House of Representatives, twelve senators, and nine governors. Each of these was a record number, compared with any year in the past. 5 Among Democrats, female candidates were more likely to win than their male counterparts. 6 Hillary Clinton’s candidacy for the presidency was a significant step in splintering, if not yet shattering, one of the hardest “glass ceilings” in the world. And Angela Merkel’s deft leadership for Germany and the European Union has provided a model for women in politics worldwide.

We can multiply instances from many different fields, from many different contexts: women today are much more likely to provide visible leadership in major institutions than they have been at any time in history.

Yet why have these changes occurred precisely at this time? I’ll suggest half a dozen factors that have made it possible for women to take these significant strides in leadership.

First is the establishment of institutions of higher education for women to-ward the end of the nineteenth century. Both men and women worked to open male institutions to women and to build schools and colleges specifically for women students. Careers and activities that had been beyond the reach of all women now for the first time became a plausible ambition. Higher education provided a new platform for leadership by women in many fields.

Virginia Woolf’s powerful essay A Room of One’s Own (1929) makes clear how crucial it was for women to be educated in a university setting. College degrees allowed women to enter professions previously barred to them and, as a result, become financially independent of their fathers and husbands and gain a measure of control over their own lives. Woolf’s less well-known but equally powerful treatise from 1939, Three Guineas, considers the impact of this development on social institutions and practices, including the relations between women and men.

The second crucial development, beginning in the late nineteenth century, was the invention of labor-saving devices such as washing machines and dryers, dishwashers and vacuum cleaners, followed in the second half of the twentieth century by computers and, later still, electronic assistants capable of ordering goods online to be delivered to your door. The women (or men) in charge of running a household today have far more mechanical and electronic support than ever before.

Ironically, for middle-class Americans today, much of the time freed up by these labor-saving devices has been redirected into “super-parenting”: parents are expected to spend much more time educating, protecting, and developing the skills of their children. Yet one might hope that these patterns could be more malleable than the punishing work required of our great-grandmothers to maintain a household.

Third is the success of the long struggle for women’s suffrage in many countries early in the twentieth century. Even more than the efforts that opened colleges and universities for women, the suffrage movements were deliberate, well-organized campaigns in which women leaders used their sources of influence strategically to obtain their goals. Enfranchised women could vote for candidates who advocated policies with particular resonance for them, including family- and child-oriented regulations and laws that tackled discriminatory practices in the labor market. Many female citizens voted as their fathers and husbands did; but the possibility of using the ballot box to pursue their priority interests was for the first time available to them. Women could also stand for election and be appointed to government offices. It is important to note, however, that in the United States, the success of the movement was tarnished by the denial of the vote to many Black persons in the South until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. 7

Fourth factor: the easy availability of reliable methods of birth control. Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own gives a vivid portrayal of women in earlier centuries who were hungry for knowledge or professional activity but bore and tended multiple children, making it impossible to find either the time or the opportunity to be educated. In the early twentieth century, there was for the first time widespread public discussion of the methods and moral dimensions of birth control. The opportunity to engage in family planning by controlling the number and timing of births gave women more freedom to engage in other tasks without worrying about unwanted pregnancies. By 1960, when “the pill” became the birth control device of choice for millions of women, the battle for legal contraception had largely been won in most of the world.

Next is women’s liberation, the “second wave” of feminism from the late 1960s through the early 1980s. This multifaceted movement encouraged countless women to reenvision their options and led to important changes in attitudes, behavior, and legal systems. The ideas of the movement were originally developed by women in Western Europe and the United States, but the implications were felt worldwide, and women in many other countries provided examples of feminist ideas and activities.

Among the most important by-products of the feminist movement in the United States was Title IX, passed as part of the Education Amendments Act in 1972. New opportunities for women in athletics and in combatting job discrimination followed the passage of this bill. There is ample evidence that participating in sports strengthens a girl’s self-confidence as well as her physical capacity. 8 And although the Equal Rights Amendment has not passed, the broadened application of the Fourteenth Amendment by federal courts made a significant difference in opening up equal opportunities for women.

A fifth factor contributing to greater scope for women’s activities is the change in economic patterns–contemporary capitalism–in which many families feel that they need two incomes to maintain themselves or achieve the lifestyle they covet. This puts more women in the workforce and thus on a potential ladder to leadership, despite remaining biases against women in jobs as varied as construction, teaching economics in a university, representing clients in major trials, and fighting forest fires.

Finally, the change in social expectations that is the cumulative result of all these developments, so that for the first time in history, in many parts of the world, it seems “natural” that a woman might be ambitious for a major leadership post and that with the right combination of talent, experience, and luck, she might actually get it. The more often it happens, the more likely it is that others will be inspired to follow that example, whereas in the past, it would never have occurred to a young girl that she might someday be CEO of a company, head of a major NGO, member of Congress, dean of a cathedral, or president of a university.

If you simply project forward the trajectory we have seen since the 1960s, you might assume that the future will be one in which all top leadership posts finally become gender-neutral, as often held by women as by men. The last bastions will fall, and it will be just as likely that the CEO of a company or the president of the country will be a woman as a man; the same will be true of other forms of leadership.

Sometimes we act as though this is the obvious path ahead, and the only question is how long it will take. On this point, the evidence is discouraging. The Gender Parity Project of the World Economic Forum predicted in 2015 that “if you were born today, you would be 118 years old when the economic gender gap is predicted to close in 2133.” 9 The report also notes that although gender parity around the world has dramatically improved in the areas of health and education, “only about 60% of the economic participation gap and only 21% of the political empowerment gap have been closed.”

Yet however glacial the rate of change, we may think: “we’ll get there eventually, because that’s where things are moving.” You might call this path convergence toward parity between men and women as leaders. This is the scenario that appears to underlie much of our current thinking, even if we have not articulated it as such.

This scenario, however, ignores some formidable barriers that women ambitious for formal leadership still face. Several familiar images or metaphors have been coined to make this point: “glass ceiling” or “leaky pipeline.” In Through the Labyrinth , sociologists Alice Eagly and Linda Carli use the ancient female image of the “labyrinth” to describe the multiple obstacles women face on the path to top leadership. It’s surely not a straight path toward eventual convergence. 10

The first and most fundamental obstacle to achieving top leadership in any field is that women in almost all societies still have primary (if not sole) responsibility for childcare and homemaking. Few organizations (or nation-states) have workplace policies that support family-friendly lifestyles, including high-quality, reliable, affordable childcare; flexible work schedules while children are young; and support for anyone caring for a sick child or aging parent. This makes things very hard for working parents, and especially for working mothers.

The unyielding expectation that one must show one’s seriousness about a job by being available to work nine- or ten-hour days, being on-call at any time of the week, and ready to move the family to wherever one’s services are needed is a tremendous obstacle to the advancement of women. Although hours worked are correlated with productivity in some jobs and professions, the situation is far more complicated than such a simple metric would indicate. Nonetheless, this measure is often used for promotion and job opportunities, explicitly or in a more subtle fashion. This expectation cuts heavily against a working mother, or a father who might want to spend significant time with his young children.

One of the most stubborn obstacles in the labyrinth is the lack of “on-ramps”: that is, pathways for women (or men) who have “stopped out” to manage a household and raise their children to rejoin their professions at a level commensurate with their talent and past experience. 11 Choices made when one’s children are born are likely to define the available options for a mother for the rest of her life, in terms of professional opportunities and salary level. We need more flexible pathways through the labyrinth so that women (or men) can–if they wish–spend more time with their kids in their earliest years and still get back on the fast track and catch up.

We need to work toward a world in which marriage with children more often involves parenting and homemaking by both partners, so that all the burden does not fall on the mother. We urgently need more easily available high-quality childcare outside the home so that working parents can be assured that their kids are well cared for while they both work full time. Reaching this goal will require more deliberate action on the part of governments, businesses, and policy-makers to create family-friendly workplaces. Such policies are in place in several European countries but have not so far been implemented in the United States. 12

Other labyrinthine obstacles include gender stereotypes that keep getting in the way of women being judged simply on their own accomplishment. Women are supposed to be nurturing, but if you are kind and sensitive, somebody will say you are not tough enough to make hard decisions; if you show that you are up to such challenges, you may be described as “shrill” or “bitchy.” This “catch-22” clearly plagued Hillary Rodham Clinton in her first campaign for the presidency and took an even more virulent form in her second campaign, when her opponent in the general election and his supporters regularly shouted profoundly misogynistic comments at her.

Women also have fewer opportunities to be mentored. Many (not all) senior women are happy to mentor other women; but if there aren’t any senior women around, and the men aren’t sympathetic, you don’t get this support. Some senior male professors or corporate leaders do try specifically to advance the careers of young women, but many male bosses find it easier to mentor young men, seeing them as younger versions of themselves; they take them out for a beer or a round of golf, and find it hard to imagine doing this for young women.

The #MeToo movement has brought valuable support to many women unwilling to speak out about sexual assault and harassment in the workplace. This is surely a significant step in removing obstacles to women’s advancement. However, this very visible effort has also made some male bosses nervous about reaching out to female subordinates in ways that might be misinterpreted. Men who are already deeply committed to advancing the cause of women do not usually react this way, but those who are less committed may use the #MeToo movement as an excuse not to support women employees, or more often, be genuinely uncertain about which boundaries are inappropriate to cross.

Another insidious obstacle for women on the path to top leadership is popular culture, a formidable force in shaping expectations for young people. Contemporary media rarely suggest a high-powered career as an appropriate ambition for a person of the female sex. The ambitions of girls and women are discouraged when they are taught to be deferential to males and not to compete with them for resources, including power and recognition. Women internalize these expectations, which leads us to question our own abilities. Women are much less likely to put themselves forward for a promotion, a fellowship, or a demanding assignment than men even when they are objectively more qualified in terms of their credentials. 13

And finally, in terms of obstacles to women’s out-front leadership, I have so far been describing the situation in Western democracies. As we know, women who might want to be involved in political activity or provide leadership in any institution face even more formidable obstacles in many parts of the world today. Think of Afghanistan, where the Taliban have denied women education or any opportunities outside the home. For young women in such settings, achieving professional status and leadership is a very distant dream.

For all of these reasons, therefore–expectations of primary responsibility for domestic duties, absence of “on-ramps” for returning to the workforce, gender stereotypes, absence of mentors, the power of popular culture, if not systematic exclusion from political activity–women ambitious for out-front leadership must deal with significant barriers that do not confront their male peers.

Addressing the topic of women’s leadership in terms of the obstacles we face makes sense, however, only if significant numbers of women are ambitious for top leadership. In an essay entitled “You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby–and You’ve Got Miles to Go,” leadership scholar Barbara Kellerman asks us to consider the possibility that most women really do not want such jobs. As she put it, “Work at the top of the greasy pole takes time, saps energy, and is usually all-consuming.” So “maybe the trade-offs high positions entail are ones that many women do not want to make.” Maybe, in other words, there are fewer women senators or CEOs because women “do not want what men have.” 14

If Kellerman is right, as women see what such positions entail, fewer will decide that high-profile leadership is where our ambitions lie, and the numbers of women in such posts will recede from the high-water mark of the late twentieth century toward something more like the world before 1950. Women have proved that we can do it, in terms of high-powered, visible leadership posts. We have seen the promised land, and many women will decide they are happier where most women traditionally have been.

We found something of this kind in a Princeton study on the fortieth anniversary of the university’s decision to include women as undergraduates. President Shirley Tilghman charged a Steering Committee on Undergraduate Women’s Leadership, which issued its report in March 2011, with determining “whether women undergraduates are realizing their academic potential and seeking opportunities for leadership at the same rate and in the same manner as their male colleagues.” 15 In a nutshell, the answer was no: women were not seeking leadership opportunities at the same rate or in the same manner.

Many recent Princeton alumnae and current female students the committee surveyed or interviewed in 2010 were not interested in holding very visible leadership positions like student government president or editor of the Princetonian ; they were more comfortable leading behind the scenes, as vice president or treasurer. There had not been a female president of the student government or of the first-year class at Princeton in the first decade of the twenty-first century. Other young women told us that they were not interested in the traditional student government organizations and instead wanted to lead in an organization that would focus on something they cared about, working for a cause: the environment, education reform, tutoring at Princeton, or a dance club or an a cappella group.

When we asked young women about this, they told us that they preferred to put their efforts where they could have an impact, in places where they could actually get the work of the organization done, rather than advancing their own resumés or having a big title. In this, they gave different answers than many of their male peers. Their attitudes also differed markedly from those of the alumnae who first made Princeton coeducational forty years before. Those women in the 1970s or 1980s were feisty pioneers determined to prove that they belonged at Princeton against considerable skepticism and opposition. They showed very different aspirations than the female students of the first decade of the twentieth century and occupied all the major leadership posts on campus on a regular basis.

Thus, our committee discovered (to quote our first general finding): “There are differences–subtle but real–between the ways most Princeton female undergraduates and most male undergraduates approach their college years, and in the ways they navigate Princeton when they arrive.” We found statistically significant differences between the ambitions and comfort-levels of undergraduate men and women at Princeton in 2010, in terms of the types of leadership that appealed to them and the ways they thought about power.

If you project forward our Princeton findings, and if Barbara Kellerman and others who share her assumptions are correct, there is no reason to believe that women and men will converge in terms of types of leadership. You might instead predict that these differential ambitions will mean that women will always choose and occupy less prominent leadership posts than men, even as they make a significant difference behind the scenes.

However, this conclusion is at odds with the way things are changing today, at Princeton and elsewhere. In addition to hearing from women who preferred low-key posts, our committee learned that women who did consider running for an office like president of college government often got the message from their peers (mostly their male peers) that such posts are more appropriately sought by men. As the discussion of women’s leadership intensifies on campus, more women stand for offices they might not have considered relevant before. Quite a few women have held top positions on campus in the past decade.

The Princeton women tell us that mentoring is very important and being encouraged to compete for a post makes a big difference. When someone–an older student, a friend or colleague, a faculty or staff member–says to a young woman: “You really ought to run for this office, you’d be really good at this,” she is much more likely to decide to be a candidate. There is a good deal of evidence that this is true far beyond the Princeton campus, including the experiences of women who decide to run for political office or state their interest in a top corporate post. 16

Therefore, to those who assert that there is a “natural” difference in motivation that explains the disparities between men and women in leadership, I would respond that we cannot know whether this is true until more women are encouraged to take on positions of leadership. We cannot determine, also, whether women are “naturally” interested in top leadership posts until women everywhere can attain such positions without making personal and family sacrifices radically disproportionate to those faced by men.

In asking what drove the dramatic change in women’s opportunities for leadership over the past half-century, I mentioned as one factor the strength of second-wave feminism. From the point of view of women and leadership, it is ironic that this movement was firmly and explicitly opposed to having any individual speak for and make decisions for other members. The cherished practice was “consciousness-raising,” with a focus on group-enabled insights. The search for consensus and common views was a significant feature of any activity projected by feminist groups in this period.

Second-wave feminism led to some significant advances for women, but the rejection of any out-front leadership meant that the gains were more limited than some members of the movement had envisioned. As was the case with Occupy Wall Street in the twenty-first century, the rejection of visible public leadership constrained the development and implementation of policy, despite the passion and commitment displayed by thousands of participants. The antipathy of second-wave feminists to power, authority, and leadership also means that it is hard to envision a feminist conception of leadership without coming to terms with this legacy.

This tension between “feminism” and “power” long predates the second wave. As women from Mary Wollstonecraft onward have attempted to understand disparities between the situation of women and men, the power held by men–in the state, the economy, and the household–has been a central part of the explanation. Feminists have often identified power with patriarchy, and therefore seen power as antipathetic to their interests as women striving to flourish as independent, creative human beings, rather than as a possible tool for change.

As a result of this age-old linkage of power with patriarchy, one further step in the decades-long progression of women from subordinate positions to positions of authority and leadership is a reconstruction of what it means to provide leadership and hold power. These activities must be detached from their fundamental connection to patriarchy, to make them more compatible with womanhood. There is evidence that this is happening today, as more and more women see power as relevant for accomplishing their goals and are increasingly willing to be seen wielding it with determination and even relish.

Many women today, in multiple contexts and in different parts of the world, are becoming more comfortable with exercising authority and holding power, and are openly ambitious to do so. These leaders see no need to deny or worry about their femininity, but instead concentrate on gaining power and getting things done. For these women, to a large extent, their sex/gender is not a relevant variable.

However, the other side of the equation–men and other women becoming comfortable with women in power and seeing their sex/gender as irrelevant–is lagging behind. Women are ready to take on significant public leadership positions in ways that have never been true before. But what about their potential followers? Large numbers of citizens in many countries and employees in many organizations–men and women–may still be reluctant to accept women as leaders who hold significant power over their lives.

This fluid situation calls both for creative feminist theorizing and for consolidating steps that are already being taken in practice. One of the most effective ways to provide the groundwork for this next stage of development is for more and more women to step forward for leadership posts. As with other profound social changes, including a broader acceptance of homosexuality and support for gay marriage, observing numerous instances of the phenomenon that initially appears “unnatural” can lead, over a remarkably short period of time, to changes in values and beliefs.

People who discover that valued friends, coworkers, or family members are gay are often likely to change their views on homosexuality. The same, one might hypothesize, will be true with women in power, as powerful women become a “normal” part of governments and corporations. The more women we see in positions of power and authority, the more “natural” it will seem for women to hold such posts.

In the final section of the Princeton report, we spoke of a world in which both women and men take on all kinds of leadership posts, out front and behind the scenes, high profile and supportive. This is neither convergence toward parity nor differential ambitions: it is a change in patterns of leadership and in the understanding of what posts are worth striving for, for both women and men.

Some of the Princeton students who argued for the importance of working for a cause saw themselves as carving out a new model of leadership. They rejected the unspoken assumption behind our study that the (only) form of leadership that really counts is being head of student government or president of your class. In doing this, they were reflecting some of the values of second-wave feminism, even when they were not aware of this influence. Believing that a visible leadership post, with a big title and a corner office, is the only type of leadership worth aspiring to is the kind of conception that second-wave feminism was determined to undermine.

Nonetheless, it remains true–and important–that the out-front, high-profile offices in the major organizations and institutions of a society come with exceptional opportunities to influence the course of events and the directions taken by large communities. Even as we value work done behind the scenes and in support of a worthy cause, we should not forget that the leaders who have the most power and the greatest degree of authority in any society are the ones who can make the most substantial difference in the world. Such posts should no longer be disproportionately held by men.

In the conclusion of her feminist classic The Second Sex , published in 1949, Simone de Beauvoir reminds us that it is very hard to anticipate clearly things we have not yet seen, and that in trying to do this, we often impoverish the world ahead. As she puts it, “Let us not forget that our lack of imagination always depopulates the future.” 17 In her chapter on “The Independent Woman,” she writes:

The free woman is just being born. . . . Her “worlds of ideas” are not necessarily different from men’s, because she will free herself by assimilating them; to know how singular she will remain and how important these singularities will be, one would have to make some foolhardy predictions. What is beyond doubt is that until now women’s possibilities have been stifled and lost to humanity, and in her and everyone’s interest it is high time she be left to take her own chances. 18

Because several generations of women and men have worked hard since 1949 to make the path easier for women, our possibilities as leaders are no longer “lost to humanity.” But these gifts are still stifled to some extent, and we are still operating with models of leadership designed primarily by and for men. It is surely high time we as women–with support from our partners, our families, our colleagues, from the political system, and from society as a whole–take our own chances.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

For helpful comments, I am much indebted to Robert O. Keohane, Shirley Tilghman, Nancy Weiss Malkiel, and Dara Strolovich; to the participants in our authors’ conference in April 2019; and to students and colleagues who raised thoughtful questions after the Albright Lecture at Wellesley College in January 2014 and the Astor Lecture at the Blavatnik School of Government, Oxford University, in March 2016.

- 1 Nannerl O. Keohane, Thinking about Leadership (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2010), 23.

- 2 Robert Dahl, “The Concept of Power,” Behavioral Science 2 (3) (1957): 202.

- 3 John W. Gardner, On Leadership (New York: Free Press, 1990), 2.

- 4 A. W. Geiger and Lauren Kent, “ Number of Women Leaders around the World Has Grown, but They’re Still a Small Group ,” Fact Tank, Pew Research Center, March 8, 2017.

- 5 Maya Salam, “ A Record 117 Women Won Office, Reshaping America’s Leadership ,” The New York Times , November 7, 2018.

- 6 Center for American Women and Politics, “By the Numbers: Women Congressional Candidates in 2018,” September 12, 2018.

- 7 On this topic, see Nannerl O. Keohane and Frances McCall Rosenbluth, “Introduction,” Dædalus 149 (1) (Winter 2020).

- 8 Anne Bowker, “The Relationship between Sports Participation and Self-Esteem During Early Adolescence,” Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science 38 (3) (2006): 214–229.

- 9 World Economic Forum, “ Gender Parity .”

- 10 Alice H. Eagly and Linda L. Carli. Through the Labyrinth: The Truth about How Women Become Leaders (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2007).

- 11 Sylvia Ann Hewlett, “Off-Ramps and On-Ramps: Women’s Non-Linear Career Paths,” in Women and Leadership: The State of Play and Strategies for Change , ed. Barbara Kellerman and Deborah L. Rhode (San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2007), 407–430.

- 12 Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn, “Female Labor Supply: Why Is the United States Falling Behind?” The American Economic Review 103 (3) (2013): 251–256.

- 13 Institute of Leadership and Management, “ Ambition and Gender at Work ” (London: Institute of Leadership and Management, 2010).

- 14 Barbara Kellerman, “You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby–and You’ve Got Miles to Go,” in The Difference “Difference” Makes , ed. Deborah Rhode (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2002), 55.

- 15 Steering Committee on Undergraduate Women’s Leadership, Report of the Steering Committee on Undergraduate Women’s Leadership (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University, 2011).

- 16 Richard Fox and Jennifer Lawless, “Uncovering the Origins of the Gender Gap in Political Ambitions,” American Political Science Review 108 (3) (2014): 499–519; and Jennifer Lawless and Richard Fox, It Takes a Candidate: Why Women Don’t Run for Office (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- 17 Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, trans. and ed. Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier (New York: Random House, 2011), 765.

- 18 Ibid., 751.

Unlocking growth: The untapped power of women in political leadership

Tea trumbic, silvana koch-mehrin, dominik weh.

Progress towards legal gender equality has stalled in many parts of the world. The data published earlier this year by Women, Business, and the Law report reveals that women, on average, have less than two-thirds of the legal protections that men have, down from a previous estimate of just over three-quarters. This stark reality is a sobering reminder of the challenges that still lie ahead.

For example, the absence of legislation prohibiting sexual harassment in public spaces, such as mass transit, hampers women's ability to access employment opportunities and fully participate in the workforce. The lack of services and financing for parents with young children places a disproportionate burden on women. Furthermore, the effectiveness of gender-sensitive legislation is often undermined by inadequate enforcement mechanisms. In many regions, women's limited political clout fuels a self-perpetuating cycle of restricted legal rights and reduced economic empowerment.

Recognizing the importance of women's representation in political leadership, the World Bank, represented by the Women Business and the Law (WBL) report , Women Political Leaders (WPL) , and the Oliver Wyman Forum (OWF) , have joined forces to address the challenges faced by women in political leadership positions. Our collaborative efforts under the Representation Matters program aim to foster women’s participation in decision-making positions, and to promote legal equality and economic opportunities not only for women, but for everyone.

The initiative comes at a critical time. Achieving equal opportunity is not only a fundamental human right for half of the world's population; it is also an opportunity to drive faster economic growth, fostering prosperity for all.

Expanding research on women's political representation. The Representation Matters program will focus its efforts on analyzing the impact of bolstering women's political representation on laws and policies that foster economic and legal gender equality. These insights could turn the vicious circle of limited legal rights and diminished economic empowerment into a virtuous one in which women participate at a higher rate in the political process, step into leadership and decision-making positions, and promote laws and policies that empower women.

The dividends of cultivating such a virtuous circle can be substantial. Several World Bank programs have demonstrated that empowering women through information and cash transfers improves children's health and educational outcomes and makes economies more resilient. The World Bank estimates that eliminating discrimination against women could increase the global GDP by 20% over the next decade.

Nevertheless, the political landscape remains challenging for women. Instigating a positive shift will require changes in culture and political institutions. Numerous legislative bodies still lack provisions for paid maternity leave or paternity leave, while gender balance remains elusive in many governing chambers. Hostile environments can often drive many women away from politics, with a significant proportion leaving after just one term. A global survey of female parliamentarians revealed widespread psychological violence, including sexist remarks and imagery, with 44% of respondents facing threats of death, rape, or abduction.

Political institutions could learn from the private sector. While not flawless, leading companies are actively evaluating their policies and work environments to attract and retain talent across genders, while closely monitoring recruitment performance. The recent Oliver Wyman Forum's Global Consumer Sentiment survey showed a shift in attitudes, with fewer Gen Z women than men expressing disinterest in political leadership—a first among all current generations.

The partnership seeks to amplify the message that increased female representation enhances overall progress and countries’ performances in the Women, Business and the Law index through joint research, analysis, and strategic outreach. The expected outcomes include:

The Representation Matters program marks a pivotal stride in the journey toward gender equality and women’s economic empowerment. By leveraging our collective expertise, resources, and networks, we are committed to producing data-driven evidence, raising awareness, and shaping policy dialogues. Through this joint effort, we seek to create a more inclusive and equitable society where women's voices are heard, and their contributions are valued. Together, we can build a future where representation truly matters.

To learn more about the program, please visit Representation Matters .

- Women, Business, and the Law

Women, Business and the Law project Program Manager

President and Founder of Women Political Leaders

Partner, Public Sector, Finance & Risk, Oliver Wyman

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

News from the Columbia Climate School

How Can ESG Support Female Leadership?

Eduarda Zoghbi and Sindhuja Kanteti

Adrienne Day

ESG adoption has been on a sharp rise, and so has criticism of it. ESG—which stands for environment, social and governance —is a framework used to assess a company’s impact on society and the environment, helping investors and stakeholders evaluate its sustainability and ethical practices.

As global awareness of sustainability and responsible business practices continues to grow, ESG has become a pivotal tool for assessing how well companies align with ethical, human capital and environmental considerations, while also laying the foundation for businesses to take sustainability beyond marketing.

As of Feb 2024, more than 90% of S&P 500 companies reported on ESG , indicating that adoption of its precepts is more than just a trend. Investors, ranging from institutional funds to individual shareholders, are increasingly considering ESG criteria when making investment choices. While the years 2021 and 2022 have seen a huge uptick in ESG investments, 2023 saw a downward trend as criticism of the framework continues to rise. Critics say the lack of standards, regulatory requirements and incomplete data collection prevents companies from getting closer to measuring and achieving gender equality.

ESG’s potential to effectively support women

Numerous studies have shown that having women in C-suite positions and enhancing overall diversity makes organizations more profitable (S&P’s When Women Lead, Firms Win and McKinsey’s Diversity Wins , etc.). According to Luisa Palacios, senior research scholar at Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy, gender-diverse corporate boards are a low-cost solution to achieve global standards . Yet businesses continue to overlook the opportunity to drive gender-transformative actions that could be harnessed through ESG metrics.

Investors are becoming more aware of the importance of gender diversity and equity in determining risks and opportunities. Still, women continue to be underrepresented in many sectors. For instance, they account for less than 20% of senior leadership positions in energy companies and 17% of chief information security officer roles in cybersecurity, among other examples that demonstrate the need to consider gender imbalances in hiring, training and promotions.

With growing ESG requirements, private companies stand to benefit from leading measures that support women’s entry, retainment and leadership in the workplace. Women are continuously undervalued in the private sector, as evinced by a UK gender pay gap repor t , where it currently stands at 7.3%; thus offering equal pay, training opportunities, mentorship, sexual harassment prevention workshops and investing in scholarships or funding opportunities to access STEM education are impactful measures to help women thrive in male-dominated sectors.

Governments are becoming more responsive to gender diversity requirements: The UK requires organizations to report on their gender pay gaps while California law mandates certain publicly traded companies include women on their boards. Openly reporting on gender pay allows investors, governments and civil society to hold companies accountable to their ESG standards and encourages equal pay. There are also initiatives helping to bridge the private and public sectors in achieving gender parity, such as the Gender Parity Accelerators . This national collaborative platform brings together ministers and CEOs to advance women’s labor force participation, pay equity and leadership. Nine countries in Latin America have committed to this initiative by creating gender certification programs for companies.

Regulators and policy makers should encourage the private sector to commit with both voluntary and mandatory ESG metrics on gender-related issues. There already are examples used to help companies measure gender equality undertakings. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), the United Nations through the UN Global Compact and UN Women, and Bloomberg have recommended metrics to evaluate a company’s performance specific to women in the workforce.

Lacking a unified methodology

Despite the metrics available to improve gender equality in the workforce, such standards are not widely deployed and used more often by investors to make decisions. While there are regulations to report on Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) data in the US and gender pay-gap data in the UK, human capital regulatory requirements are limited in terms of both number of requirements and definition in comparison with environmental disclosure requirements. This reinforces the need for policymaking and targeted government interventions to adapt standards into regulatory frameworks and laws as a commitment to gender equality. No one country has achieved full gender parity , but some of the ones leading this race had government incentives to bring metrics into regulation.

Furthermore, the vast interpretation of standards and lack of a unified methodology is drawing huge criticism of ESG. When investigating reasons for a downward trend in ESG investing, it can be observed it was not due to lack of importance—rather it’s due to the vast interpretation of standards and the overall number of standards. Unless a more detailed guidance is given on these metrics, it will be challenging for widespread adoption and comparability.

Despite progress in human capital systems and data collection, many companies lack robustness in gathering human capital data compared to financial data. While most S&P 500 companies report on both “environment” and “human capital” metrics, only a few ensure the same level of reliability and accuracy. Gender-related data collection inadequacies within organizations hinder disclosure of gender-related metrics. Robust data collection mechanisms are crucial for accurate gender-related information.

Implementation remains challenging and organizations’ leadership must recognize gender equality is key to operations as part of the UN 2030 Agenda, through Sustainable Development Goal 5. At the current rate, it will take 286 years to close the gender gap and 140 years to achieve equal representation in leadership at the workplace . Business leaders will have to choose between the status quo or leading transformative efforts to make our planet more just and inclusive. This begins by robust data collection and reporting along with actions to increase gender parity.

Eduarda Zoghbi is a SIPA MPA-ESP graduate (’22) and currently works as a climate and energy specialist for the finance and policy organization Climate Investment Funds. Sindhuja Kanteti is an emissions technical advisor at Baker Hughes, an energy and technology company. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of their employers.

Views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Columbia Climate School, Earth Institute or Columbia University.

Related Posts

All in the Family: One Environmental Science and Policy Student’s Path to Columbia

Women in ESG: Working at the Intersection of Business and Sustainability

Decarbonization and the Changing Organizational Culture of Business

Congratulations to our Columbia Climate School MA in Climate & Society Class of 2024! Learn about our May 10 Class Day celebration. #ColumbiaClimate2024

Get the Columbia Climate School Newsletter

More From Forbes

How are women at the top doing it all they aren’t.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Working mothers feel the pressure to do it all.

As a woman with a big career, three kids, and a few side passions, I often get the question: How do you do it all? Well, I’m here to burst your bubble. I don’t do it all—not by a long shot. And the successful women I’ve spoken with don’t either.

The problem is that no one is talking about this, and it’s creating the illusion that some women have figured out how to do it all: Have a successful career, be perfectly present parents, volunteer on the PTA, make organic meals from scratch every day, connect with friends, go to the gym, and maintain a spotless home.

The reality is that these women have a lot of help and those who are trying to do it themselves are burning out!

Jennifer Gore-Cuthbert, the sole owner of Atlanta Personal Injury Law Group had this realization years ago, and it’s served her well. Her business does 7-figures and employs 42 people. By contrast, although 39.1% of all US businesses are women-owned , only 2% of women-owned businesses hit the 7-figure mark .

Gore-Cuthbert says she lives her life radically differently, which is precisely why she’s achieved radically different results. This means outsourcing almost all domestic chores. She claims that men have traditionally had these things managed for them, which has given them a competitive advantage. “I just started modeling what all the men were doing.”

Gore-Cuthbert speaks about it so openly and unapologetically, because she wants more women to have this same advantage.

Danielle Canty, who co-founded and later exited the 8-figure membership company BossBabe, has since launched two new businesses and welcomed her first baby. She’s equally unapologetic. “I do have help. I have a nanny, I have a cleaner, I have a personal assistant. I had a night nurse.”

Google Chrome Gets Third Emergency Update In A Week As Attacks Continue

Biden vs. trump 2024 election polls: biden losing support among key voting blocs, japanese fans are puzzled that yasuke is in assassin s creed shadows.

Canty believes that women aren’t talking about this because of the ‘mum guilt’ we put on ourselves and the judgment of other mothers.

“I’ve unsubscribed from mum guilt,” says Canty. I’m just not doing it.” Canty speaks passionately about the need to have these conversations because she believes that, as a society, we need to “put more emphasis on the mental health of mothers and support them, not berate them.”

Although Gore-Cuthbert and Canty are willing to share openly, multiple other women are less open to sharing due to the fear of others' judgment or a sense of guilt that they have help when others don’t. These women worry they will make women in less fortunate situations feel bad.

This silence is creating two problems for women:

1. women believe they should be able to ‘do it all’..

Because women aren’t aware of the help that so many of us have behind the scenes, they feel as though they are failing when in fact, they are trying to live up to an impossible standard.

2. Women are put at a disadvantage career-wise.

This is the ‘competitive advantage’ that Gore-Cuthbert speaks of. If men are only focused on career advancement, while women are focused on their careers, family management, doctor appointments, laundry, cooking, bake sales, volunteering at school, and more, how on earth can we keep up?

According to Gore-Cuthbert, ambitious women need to consider making this change before we have the corner office because if we don’t, we’ll never get there.

Aimee Gindin, who climbed the corporate ladder to Chief Marketing Officer made the decision to have a single child because she and her husband both wanted big careers. Although she doesn’t feel the pressure for perfection behind closed doors, she admits there’s pressure in what people think.

Gindin’s family invests time in cooking because they love it, but outsources cleaning and landscaping. “I think you can ‘do it all’ but you can't ‘do it all at once.’ Time is finite, so pick the things that are important to you, and if you can afford it, outsource the rest.”

Gindin’s comment about affordability is important because not all women have the resources to outsource domestic duties, but the conversation is important nonetheless. The message is in letting go of perfectionism and prioritizing what matters most to you as a working mother.

That may mean outsourcing cleaning, or it may mean letting the laundry pile up for a few days while you focus on that project, or not feeling guilty when your child watches TV so you can squeeze in a quick workout.

Regardless of your situation, I hope it means giving yourself a little extra grace today.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Join The Conversation

One Community. Many Voices. Create a free account to share your thoughts.

Forbes Community Guidelines

Our community is about connecting people through open and thoughtful conversations. We want our readers to share their views and exchange ideas and facts in a safe space.

In order to do so, please follow the posting rules in our site's Terms of Service. We've summarized some of those key rules below. Simply put, keep it civil.

Your post will be rejected if we notice that it seems to contain:

- False or intentionally out-of-context or misleading information

- Insults, profanity, incoherent, obscene or inflammatory language or threats of any kind

- Attacks on the identity of other commenters or the article's author

- Content that otherwise violates our site's terms.

User accounts will be blocked if we notice or believe that users are engaged in:

- Continuous attempts to re-post comments that have been previously moderated/rejected

- Racist, sexist, homophobic or other discriminatory comments

- Attempts or tactics that put the site security at risk

- Actions that otherwise violate our site's terms.

So, how can you be a power user?

- Stay on topic and share your insights

- Feel free to be clear and thoughtful to get your point across

- ‘Like’ or ‘Dislike’ to show your point of view.

- Protect your community.

- Use the report tool to alert us when someone breaks the rules.

Thanks for reading our community guidelines. Please read the full list of posting rules found in our site's Terms of Service.

Women in Leadership Dominate at Expedia Conference

Dennis Schaal , Skift

May 15th, 2024 at 12:51 PM EDT

Expedia's leadership is unique among major online travel companies in the West.

Dennis Schaal

Expedia Group’s Explore 24 partner meeting in Las Vegas this week has had plenty of news announcements about AI and advertising initiatives. But the women in leadership stood out.

Ariane Gorin became Expedia Group’s CEO on Monday, Julie Whalen has been the chief financial officer since 2022, and Rathi Murthy has been the chief technology officer since 2021.

At a press gathering Tuesday morning, Lauri Metrose, senior vice president of global communications, noted that the company has a “trifecta” of women in those key leadership positions.

Murthy told the press that it was important that she found her “voice” during her career path, and at Expedia she tries to empower women coming up through the ranks.

Expedia’s leadership is unique among major online travel companies in the West — including Airbnb, Booking Holdings, Tripadvisor and Uber. Trip.com Group in China likewise has a woman CEO, Janie Jie Sun, and Chief Financial Officer Cindy Xiaofan Wang.

(From left) Lauri Metrose, Expedia Group’s svp, global communications; CEO Ariane Gorin and CTO Rathi Murthy. They addressed the press May 14, 2024 at Expedia Explore 24 in Las Vegas. Source: Skift

Other female leaders from Expedia also led sessions during the event, including: Jennifer Andre, vice president of business development, media solutions; Michele Rousseau, senior vice president of global brands and creative; Reena Patil, senior vice president of partner product and marketplace; and Karen Bolda, senior vice president of B2B product and technology.

Whether it’s women in leadership or men, investors will be looking to see whether Expedia Group can get back on track and accelerate the growth of its consumer brands, with Vrbo and Hotels.com in particular not bouncing back fast enough after a technology migration.

Barry Diller, Expedia Group’s senior executive and chairman, said the company had conducted an outside search to find a CEO to replace Peter Kern, but chose Gorin, an internal candidate.

Diller said 90% of the mistakes in CEO successions occur when companies opt for an outside candidate whom they might not know very well. When you go for an outside candidate, “the casualty rate is high,” he said.

Of Gorin, Diller said he’s never seen a CEO step in so confidently as a leader.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: ariane gorin , barry diller , corporate governance , DEI , expedia , expedia group , online travel newsletter

Photo credit: Michele Rousseau, Expedia Group senior vice president of global brands and creative, at Explore 24 in Las Vegas May 14, 2024. Expedia Group

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

My hypothesis is that successful female leaders adopt a transformational leadership. style and have a high level of emotional intelligence, as compared to unsuccessful leaders who. will adopt more of a transactional style of leadership and have a lower level of emotional. intelligence. 4.

leadership positions. This thesis is based on the fact that there are less female leaders than male leaders, both globally and in Finland. The thesis aims to find the influential factors behind women's career and ways to increase the number of women in leadership positions. The thesis was commissioned by Havis Amanda Junior Chamber - Helsinki.

in which female leaders behave, such as emphasizing people development and collaboration, can benefit a company's organizational health and financial performance" (McKinsey, 2012, p. 103). ... This doctoral thesis could impact practices for aspiring candidates and for academic institutions seeking diversity in leadership. Leadership and the ...

countries, culture can be understood as a key influencing factor in supporting women as leaders. This thesis aims to contribute to a deeper knowledge about female leadership and women's opportunities in management. The relationship between women in leadership and culture will be highlighted.

Women leaders are likely to have a number of unique soft and hard competitive factors, some of which contribute to their competitive advantage. The results suggest that in order to increase leadership effectiveness, leaders should take advantages from their soft and hard competitive factors. In addition, knowing their own qualities (subjective ...

countries and 94 men-led countries, "Women leaders reacted more quickly and decisively in the face of potential fatalities, locking down earlier than men leaders."1 Outcomes from women-led countries resulted were more positive, such as fewer COVID-19 cases and fatalities during the initial stage of the pandemic.2 These women utilized leadership

leadership style that is quite different than female leaders. Most researchers have found that women typically use a transformational leadership style, in which they seek to motivate and involve employees in decisions, often using charisma to do so (Spurgeon & Cross, 2006). On the contrary, male leaders are more likely to use a more directive and

Research of Leadership Qualities Exhibited by Female Leaders by Leslie Isenhour Graduation December, 2020 ... then be created for other women on qualities that it takes to be a successful female leader. This thesis is an attempt to provide helpful guidance to aspiring, predominantly female leaders of tomorrow. CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW ...

Women In Leadership: A Qualitative Review Of Challenges, Experiences, And Strategies In Addressing Gender Bias ... Thesis Chair: Susan Tortolero Emery, PhD . Women are entering the workforce at an increasing rate, yet they are still drastically underrepresented in leadership positions. The primary research question addressed in this

the goal of this investigation is to gather data on how some women in leadership positions have navigated the complexities specific to their gender when pursuing leadership roles. Hoyt and Murphy (2016) reported that promoting opportunity and expectations for participation by women in leadership roles is important in maintaining a prosperous ...

Focusing on women leaders who perform gender diverging from reproduction of homosocial patterns, the study further extends research on elite leaders as change-agents (Kelan & Wratil, Citation 2020; Wahl, Citation 2014). The article is structured as follows. The following section begins with an overview of previous research on the fields of ...

The thesis is a qualitative study of women and leadership. Particularly women's views on good and effective leadership and women's leadership qualities. The study addresses two ... female leaders including PepsiCo's CEO Indra Nooyi, KPMG CEO Lynne Doughtie to Anne Wojcicki CEO of 23&me (Northouse,2016). Women make effective leaders (Ea-