- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Science Writing

How to Write a Good Lab Conclusion in Science

Last Updated: March 21, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Bess Ruff, MA . Bess Ruff is a Geography PhD student at Florida State University. She received her MA in Environmental Science and Management from the University of California, Santa Barbara in 2016. She has conducted survey work for marine spatial planning projects in the Caribbean and provided research support as a graduate fellow for the Sustainable Fisheries Group. There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 1,763,105 times.

A lab report describes an entire experiment from start to finish, outlining the procedures, reporting results, and analyzing data. The report is used to demonstrate what has been learned, and it will provide a way for other people to see your process for the experiment and understand how you arrived at your conclusions. The conclusion is an integral part of the report; this is the section that reiterates the experiment’s main findings and gives the reader an overview of the lab trial. Writing a solid conclusion to your lab report will demonstrate that you’ve effectively learned the objectives of your assignment.

Outlining Your Conclusion

- Restate : Restate the lab experiment by describing the assignment.

- Explain : Explain the purpose of the lab experiment. What were you trying to figure out or discover? Talk briefly about the procedure you followed to complete the lab.

- Results : Explain your results. Confirm whether or not your hypothesis was supported by the results.

- Uncertainties : Account for uncertainties and errors. Explain, for example, if there were other circumstances beyond your control that might have impacted the experiment’s results.

- New : Discuss new questions or discoveries that emerged from the experiment.

- Your assignment may also have specific questions that need to be answered. Make sure you answer these fully and coherently in your conclusion.

Discussing the Experiment and Hypothesis

- If you tried the experiment more than once, describe the reasons for doing so. Discuss changes that you made in your procedures.

- Brainstorm ways to explain your results in more depth. Go back through your lab notes, paying particular attention to the results you observed. [5] X Trustworthy Source University of North Carolina Writing Center UNC's on-campus and online instructional service that provides assistance to students, faculty, and others during the writing process Go to source

- Start this section with wording such as, “The results showed that…”

- You don’t need to give the raw data here. Just summarize the main points, calculate averages, or give a range of data to give an overall picture to the reader.

- Make sure to explain whether or not any statistical analyses were significant, and to what degree, such as 1%, 5%, or 10%.

- Use simple language such as, “The results supported the hypothesis,” or “The results did not support the hypothesis.”

Demonstrating What You Have Learned

- If it’s not clear in your conclusion what you learned from the lab, start off by writing, “In this lab, I learned…” This will give the reader a heads up that you will be describing exactly what you learned.

- Add details about what you learned and how you learned it. Adding dimension to your learning outcomes will convince your reader that you did, in fact, learn from the lab. Give specifics about how you learned that molecules will act in a particular environment, for example.

- Describe how what you learned in the lab could be applied to a future experiment.

- On a new line, write the question in italics. On the next line, write the answer to the question in regular text.

- If your experiment did not achieve the objectives, explain or speculate why not.

Wrapping Up Your Conclusion

- If your experiment raised questions that your collected data can’t answer, discuss this here.

- Describe what is new or innovative about your research.

- This can often set you apart from your classmates, many of whom will just write up the barest of discussion and conclusion.

Finalizing Your Lab Report

Community Q&A

- If you include figures or tables in your conclusion, be sure to include a brief caption or label so that the reader knows what the figures refer to. Also, discuss the figures briefly in the text of your report. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Once again, avoid using personal pronouns (I, myself, we, our group) in a lab report. The first-person point-of-view is often seen as subjective, whereas science is based on objectivity. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Ensure the language used is straightforward with specific details. Try not to drift off topic. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Take care with writing your lab report when working in a team setting. While the lab experiment may be a collaborative effort, your lab report is your own work. If you copy sections from someone else’s report, this will be considered plagiarism. Thanks Helpful 3 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://phoenixcollege.libguides.com/LabReportWriting/introduction

- ↑ https://www.hcs-k12.org/userfiles/354/Classes/18203/conclusionwriting.pdf

- ↑ https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/english/literacy/Pages/puttingittogether.aspx

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/brainstorming/

- ↑ https://advice.writing.utoronto.ca/types-of-writing/lab-report/

- ↑ http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/hypothes.php

- ↑ https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/conclusion

- ↑ https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/introduction/researchproblem

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/scientific-reports/

- ↑ https://phoenixcollege.libguides.com/LabReportWriting/labreportstyle

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

About This Article

To write a good lab conclusion in science, start with restating the lab experiment by describing the assignment. Next, explain what you were trying to discover or figure out by doing the experiment. Then, list your results and explain how they confirmed or did not confirm your hypothesis. Additionally, include any uncertainties, such as circumstances beyond your control that may have impacted the results. Finally, discuss any new questions or discoveries that emerged from the experiment. For more advice, including how to wrap up your lab report with a final statement, keep reading. Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Maddie Briere

Oct 5, 2017

Did this article help you?

Jun 13, 2017

Saujash Barman

Sep 7, 2017

Cindy Zhang

Jan 16, 2017

Oct 29, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

Complete Guide to Writing a Lab Report (With Example)

Students tend to approach writing lab reports with confusion and dread. Whether in high school science classes or undergraduate laboratories, experiments are always fun and games until the times comes to submit a lab report. What if we didn’t need to spend hours agonizing over this piece of scientific writing? Our lives would be so much easier if we were told what information to include, what to do with all their data and how to use references. Well, here’s a guide to all the core components in a well-written lab report, complete with an example.

Things to Include in a Laboratory Report

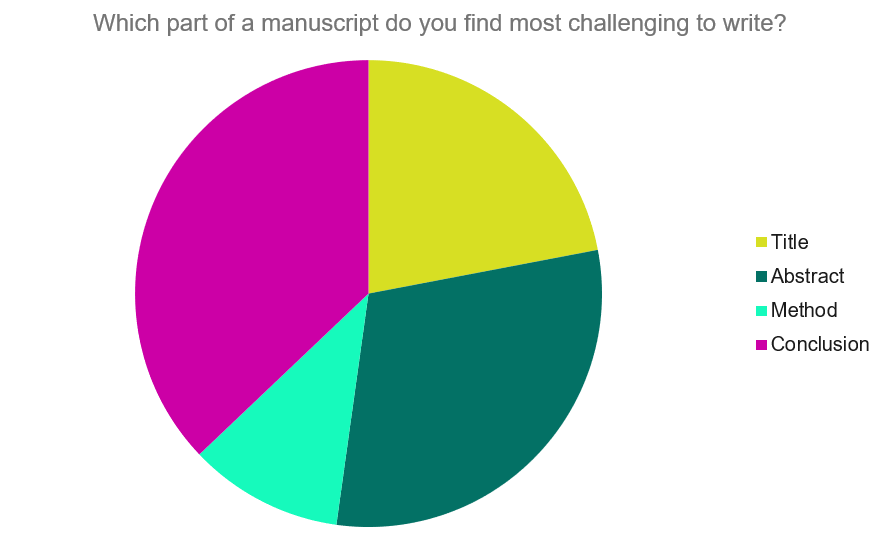

The laboratory report is simply a way to show that you understand the link between theory and practice while communicating through clear and concise writing. As with all forms of writing, it’s not the report’s length that matters, but the quality of the information conveyed within. This article outlines the important bits that go into writing a lab report (title, abstract, introduction, method, results, discussion, conclusion, reference). At the end is an example report of reducing sugar analysis with Benedict’s reagent.

The report’s title should be short but descriptive, indicating the qualitative or quantitative nature of the practical along with the primary goal or area of focus.

Following this should be the abstract, 2-3 sentences summarizing the practical. The abstract shows the reader the main results of the practical and helps them decide quickly whether the rest of the report is relevant to their use. Remember that the whole report should be written in a passive voice .

Introduction

The introduction provides context to the experiment in a couple of paragraphs and relevant diagrams. While a short preamble outlining the history of the techniques or materials used in the practical is appropriate, the bulk of the introduction should outline the experiment’s goals, creating a logical flow to the next section.

Some reports require you to write down the materials used, which can be combined with this section. The example below does not include a list of materials used. If unclear, it is best to check with your teacher or demonstrator before writing your lab report from scratch.

Step-by-step methods are usually provided in high school and undergraduate laboratory practicals, so it’s just a matter of paraphrasing them. This is usually the section that teachers and demonstrators care the least about. Any unexpected changes to the experimental setup or techniques can also be documented here.

The results section should include the raw data that has been collected in the experiment as well as calculations that are performed. It is usually appropriate to include diagrams; depending on the experiment, these can range from scatter plots to chromatograms.

The discussion is the most critical part of the lab report as it is a chance for you to show that you have a deep understanding of the practical and the theory behind it. Teachers and lecturers tend to give this section the most weightage when marking the report. It would help if you used the discussion section to address several points:

- Explain the results gathered. Is there a particular trend? Do the results support the theory behind the experiment?

- Highlight any unexpected results or outlying data points. What are possible sources of error?

- Address the weaknesses of the experiment. Refer to the materials and methods used to identify improvements that would yield better results (more accurate equipment, better experimental technique, etc.)

Finally, a short paragraph to conclude the laboratory report. It should summarize the findings and provide an objective review of the experiment.

If any external sources were used in writing the lab report, they should go here. Referencing is critical in scientific writing; it’s like giving a shout out (known as a citation) to the original provider of the information. It is good practice to have at least one source referenced, either from researching the context behind the experiment, best practices for the method used or similar industry standards.

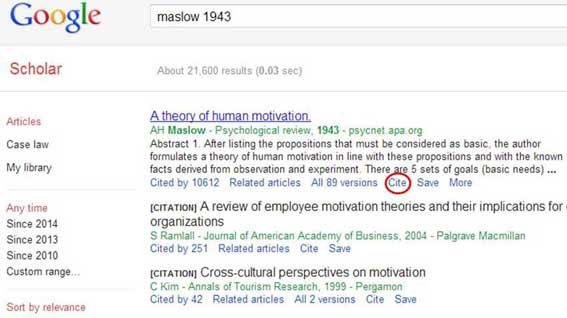

Google Scholar is a good resource for quickly gathering references of a specific style . Searching for the article in the search bar and clicking on the ‘cite’ button opens a pop-up that allows you to copy and paste from several common referencing styles.

Example: Writing a Lab Report

Title : Semi-Quantitative Analysis of Food Products using Benedict’s Reagent

Abstract : Food products (milk, chicken, bread, orange juice) were solubilized and tested for reducing sugars using Benedict’s reagent. Milk contained the highest level of reducing sugars at ~2%, while chicken contained almost no reducing sugars.

Introduction : Sugar detection has been of interest for over 100 years, with the first test for glucose using copper sulfate developed by German chemist Karl Trommer in 1841. It was used to test the urine of diabetics, where sugar was present in high amounts. However, it wasn’t until 1907 when the method was perfected by Stanley Benedict, using sodium citrate and sodium carbonate to stabilize the copper sulfate in solution. Benedict’s reagent is a bright blue because of the copper sulfate, turning green and then red as the concentration of reducing sugars increases.

Benedict’s reagent was used in this experiment to compare the amount of reducing sugars between four food items: milk, chicken solution, bread and orange juice. Following this, standardized glucose solutions (0.0%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%) were tested with Benedict’s reagent to determine the color produced at those sugar levels, allowing us to perform a semi-quantitative analysis of the food items.

Method : Benedict’s reagent was prepared by mixing 1.73 g of copper (II) sulfate pentahydrate, 17.30 g of sodium citrate pentahydrate and 10.00 g of sodium carbonate anhydrous. The mixture was dissolved with stirring and made up to 100 ml using distilled water before filtration using filter paper and a funnel to remove any impurities.

4 ml of milk, chicken solution and orange juice (commercially available) were measured in test tubes, along with 4 ml of bread solution. The bread solution was prepared using 4 g of dried bread ground with mortar and pestle before diluting with distilled water up to 4 ml. Then, 4 ml of Benedict’s reagent was added to each test tube and placed in a boiling water bath for 5 minutes, then each test tube was observed.

Next, glucose solutions were prepared by dissolving 0.5 g, 1.0 g, 1.5 g and 2.0 g of glucose in 100 ml of distilled water to produce 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5% and 2.0% solutions, respectively. 4 ml of each solution was added to 4 ml of Benedict’s reagent in a test tube and placed in a boiling water bath for 5 minutes, then each test tube was observed.

Results : Food Solutions (4 ml) with Benedict’s Reagent (4 ml)

Glucose Solutions (4 ml) with Benedict’s Reagent (4 ml)

Semi-Quantitative Analysis from Data

Discussion : From the analysis of food solutions along with the glucose solutions of known concentrations, the semi-quantitative analysis of sugar levels in different food products was performed. Milk had the highest sugar content of 2%, with orange juice at 1.5%, bread at 0.5% and chicken with 0% sugar. These values were approximated; the standard solutions were not the exact color of the food solutions, but the closest color match was chosen.

One point of contention was using the orange juice solution, which conferred color to the starting solution, rendering it green before the reaction started. This could have led to the final color (and hence, sugar quantity) being inaccurate. Also, since comparing colors using eyesight alone is inaccurate, the experiment could be improved with a colorimeter that can accurately determine the exact wavelength of light absorbed by the solution.

Another downside of Benedict’s reagent is its inability to react with non-reducing sugars. Reducing sugars encompass all sugar types that can be oxidized from aldehydes or ketones into carboxylic acids. This means that all monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, etc.) are reducing sugars, while only select polysaccharides are. Disaccharides like sucrose and trehalose cannot be oxidized, hence are non-reducing and will not react with Benedict’s reagent. Furthermore, Benedict’s reagent cannot distinguish between different types of reducing sugars.

Conclusion : Using Benedict’s reagent, different food products were analyzed semi-quantitatively for their levels of reducing sugars. Milk contained around 2% sugar, while the chicken solution had no sugar. Overall, the experiment was a success, although the accuracy of the results could have been improved with the use of quantitative equipment and methods.

Reference :

- Raza, S. I., Raza, S. A., Kazmi, M., Khan, S., & Hussain, I. (2021). 100 Years of Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Management. Journal of Diabetes Mellitus , 11 (5), 221-233.

- Benedict, Stanley R (1909). A Reagent for the Detection of Reducing Sugars. Journal of Biological Chemistry , 5 , 485-487.

Using this guide and example, writing a lab report should be a hassle-free, perhaps even enjoyable process!

About the Author

Sean is a consultant for clients in the pharmaceutical industry and is an associate lecturer at La Trobe University, where unfortunate undergrads are subject to his ramblings on chemistry and pharmacology.

You Might Also Like…

A guide to pcr and qpcr (quantitative polymerase chain reaction), cytochrome p450 (cyp450) enzymes: meet the family.

If our content has been helpful to you, please consider supporting our independent science publishing efforts: for just $1 a month.

© 2023 FTLOScience • All Rights Reserved

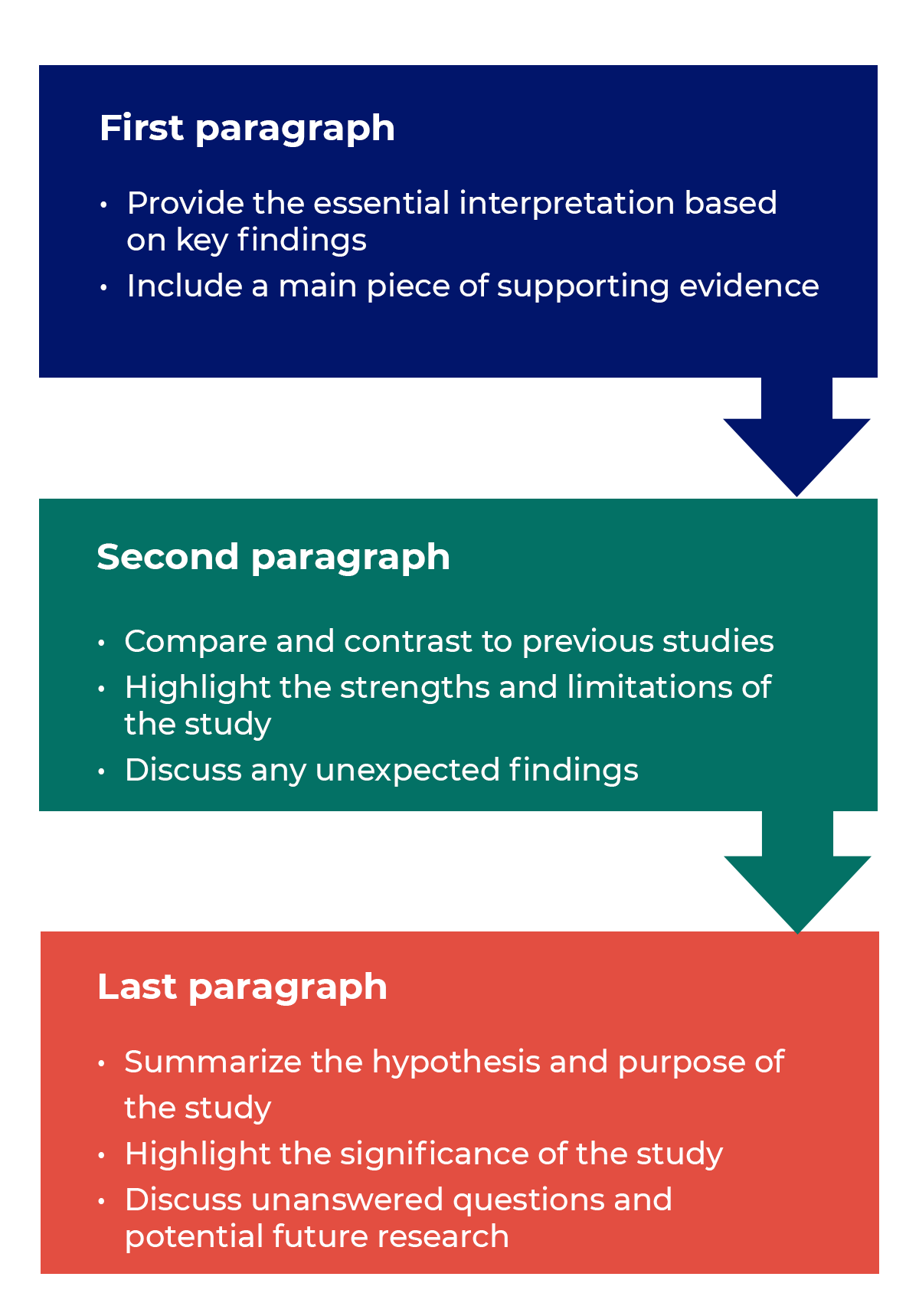

Conclusions

This page will support you in satisfying Writing Learning Outcome:

CONCLUSION - Provide an effective conclusion that summarizes the laboratory's purpose, processes, and key findings, and makes appropriate recommendations.

Learning Objectives

You should be able to

Identify technical audience expectations for engineering lab report conclusions.

Describe what makes a conclusion meaningful, especially to a technical audience.

Relate the idea of audience expectations to prior writing instruction.

Write meaningful conclusions for an engineering lab report.

Summarize the important contents of the laboratory report clearly, succinctly, and with sufficient specificity.

Support conclusions with the evidence presented earlier in the lab report.

What is a Meaningful Conclusion in an Engineering Lab Report?

A conclusion is meaningful if it includes a summary of the work (i.e., objective and process) as well as the key findings (i.e., the results of the work and their implications) of the lab work.

The technical audience expects the following features to make the conclusion meaningful.

Restate the objective briefly.

Restate the lab process briefly.

Restate the important results of the lab work briefly, including any significant errors.

Restate the important findings briefly to meet the objective.

Provide brief recommendations for future actions or laboratories.

What Are Some Common Mistakes Seen in Poorly Written Engineering Lab Reports?

No conclusion is included in the report.

The conclusion is missing an important part (i.e., lab o bjective and key results) of the lab.

New data or new discussion is included that was not written in the report body.

Concluding statements do not address the stated objectives of the report.

The conclusion includes opinions only rather than the facts supported by other sections of the report.

Statements are overly general without containing any meaningful takeaways.

Statements are overly specific with the detailed descriptions which are supposed to be in the body.

Sample Conclusions

Why Does the Technical Audience Value Meaningful Conclusions From Engineering Lab Reports?

The technical audience reads the lab report conclusions carefully to take away the writer’s most important information. If the conclusion is well written, they may not need to read any other part of the report or know that they want to read the rest of the report to understand important details.

How Can we Use Engineering Judgment When Drawing Lab Report Conclusions?

In the context of engineering lab reports, engineering judgment can be defined as an application of evidence (i.e., lab data) and engineering principles (i.e., theory) to make decisions. The technical audience can trust the conclusions only when they are based on accurate data. The writer should use appropriate engineering principles when investigating and discussing lab data.

Common Mistakes

The conclusion is missing an important part (i.e., key results) of the lab.

Kim, J., Kim, D., (2019) “How engineering students draw conclusions from lab reports and design project reports in junior-level engineering courses,” The Proceedings of 2019 ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Tampa, FL, June 2019. https://peer.asee.org/how-engineering-students-draw-conclusions-from-lab-reports-and-design-project-reports-injunior-level-engineering-courses.pdf

“Argument Papers”, Purdue University, Purdue Online Writing Lab, Argument Papers, https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/argument_papers/conclusions.html

“Student Writing Guide”, University of Minnesota Department of Mechanical Engineering, http://www.me.umn.edu/education/undergraduate/writing/MESWG-Lab.1.5.pdf

Lab Report Format: Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

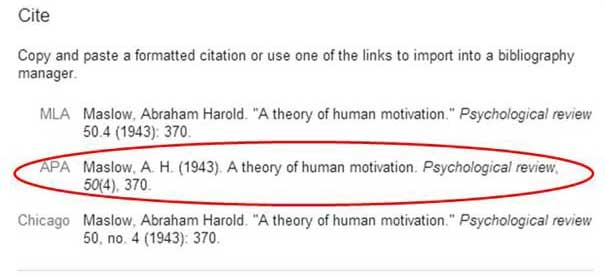

In psychology, a lab report outlines a study’s objectives, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions, ensuring clarity and adherence to APA (or relevant) formatting guidelines.

A typical lab report would include the following sections: title, abstract, introduction, method, results, and discussion.

The title page, abstract, references, and appendices are started on separate pages (subsections from the main body of the report are not). Use double-line spacing of text, font size 12, and include page numbers.

The report should have a thread of arguments linking the prediction in the introduction to the content of the discussion.

This must indicate what the study is about. It must include the variables under investigation. It should not be written as a question.

Title pages should be formatted in APA style .

The abstract provides a concise and comprehensive summary of a research report. Your style should be brief but not use note form. Look at examples in journal articles . It should aim to explain very briefly (about 150 words) the following:

- Start with a one/two sentence summary, providing the aim and rationale for the study.

- Describe participants and setting: who, when, where, how many, and what groups?

- Describe the method: what design, what experimental treatment, what questionnaires, surveys, or tests were used.

- Describe the major findings, including a mention of the statistics used and the significance levels, or simply one sentence summing up the outcome.

- The final sentence(s) outline the study’s “contribution to knowledge” within the literature. What does it all mean? Mention the implications of your findings if appropriate.

The abstract comes at the beginning of your report but is written at the end (as it summarises information from all the other sections of the report).

Introduction

The purpose of the introduction is to explain where your hypothesis comes from (i.e., it should provide a rationale for your research study).

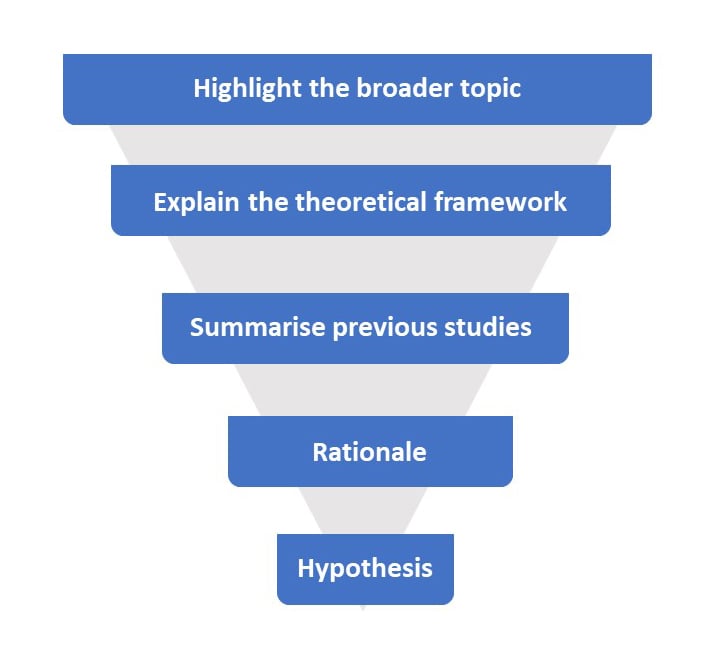

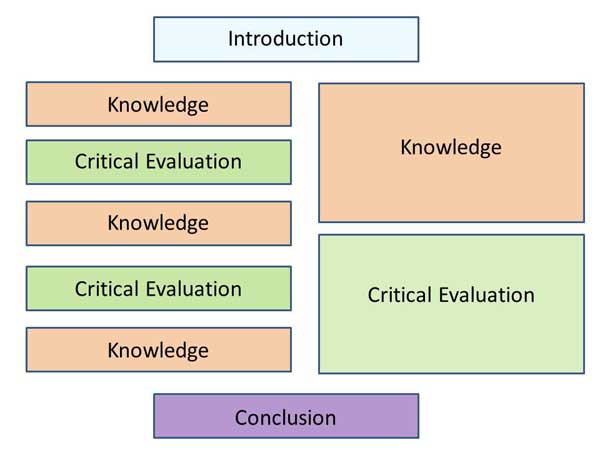

Ideally, the introduction should have a funnel structure: Start broad and then become more specific. The aims should not appear out of thin air; the preceding review of psychological literature should lead logically into the aims and hypotheses.

- Start with general theory, briefly introducing the topic. Define the important key terms.

- Explain the theoretical framework.

- Summarise and synthesize previous studies – What was the purpose? Who were the participants? What did they do? What did they find? What do these results mean? How do the results relate to the theoretical framework?

- Rationale: How does the current study address a gap in the literature? Perhaps it overcomes a limitation of previous research.

- Aims and hypothesis. Write a paragraph explaining what you plan to investigate and make a clear and concise prediction regarding the results you expect to find.

There should be a logical progression of ideas that aids the flow of the report. This means the studies outlined should lead logically to your aims and hypotheses.

Do be concise and selective, and avoid the temptation to include anything in case it is relevant (i.e., don’t write a shopping list of studies).

USE THE FOLLOWING SUBHEADINGS:

Participants

- How many participants were recruited?

- Say how you obtained your sample (e.g., opportunity sample).

- Give relevant demographic details (e.g., gender, ethnicity, age range, mean age, and standard deviation).

- State the experimental design .

- What were the independent and dependent variables ? Make sure the independent variable is labeled and name the different conditions/levels.

- For example, if gender is the independent variable label, then male and female are the levels/conditions/groups.

- How were the IV and DV operationalized?

- Identify any controls used, e.g., counterbalancing and control of extraneous variables.

- List all the materials and measures (e.g., what was the title of the questionnaire? Was it adapted from a study?).

- You do not need to include wholesale replication of materials – instead, include a ‘sensible’ (illustrate) level of detail. For example, give examples of questionnaire items.

- Include the reliability (e.g., alpha values) for the measure(s).

- Describe the precise procedure you followed when conducting your research, i.e., exactly what you did.

- Describe in sufficient detail to allow for replication of findings.

- Be concise in your description and omit extraneous/trivial details, e.g., you don’t need to include details regarding instructions, debrief, record sheets, etc.

- Assume the reader has no knowledge of what you did and ensure that he/she can replicate (i.e., copy) your study exactly by what you write in this section.

- Write in the past tense.

- Don’t justify or explain in the Method (e.g., why you chose a particular sampling method); just report what you did.

- Only give enough detail for someone to replicate the experiment – be concise in your writing.

- The results section of a paper usually presents descriptive statistics followed by inferential statistics.

- Report the means, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each IV level. If you have four to 20 numbers to present, a well-presented table is best, APA style.

- Name the statistical test being used.

- Report appropriate statistics (e.g., t-scores, p values ).

- Report the magnitude (e.g., are the results significant or not?) as well as the direction of the results (e.g., which group performed better?).

- It is optional to report the effect size (this does not appear on the SPSS output).

- Avoid interpreting the results (save this for the discussion).

- Make sure the results are presented clearly and concisely. A table can be used to display descriptive statistics if this makes the data easier to understand.

- DO NOT include any raw data.

- Follow APA style.

Use APA Style

- Numbers reported to 2 d.p. (incl. 0 before the decimal if 1.00, e.g., “0.51”). The exceptions to this rule: Numbers which can never exceed 1.0 (e.g., p -values, r-values): report to 3 d.p. and do not include 0 before the decimal place, e.g., “.001”.

- Percentages and degrees of freedom: report as whole numbers.

- Statistical symbols that are not Greek letters should be italicized (e.g., M , SD , t , X 2 , F , p , d ).

- Include spaces on either side of the equals sign.

- When reporting 95%, CIs (confidence intervals), upper and lower limits are given inside square brackets, e.g., “95% CI [73.37, 102.23]”

- Outline your findings in plain English (avoid statistical jargon) and relate your results to your hypothesis, e.g., is it supported or rejected?

- Compare your results to background materials from the introduction section. Are your results similar or different? Discuss why/why not.

- How confident can we be in the results? Acknowledge limitations, but only if they can explain the result obtained. If the study has found a reliable effect, be very careful suggesting limitations as you are doubting your results. Unless you can think of any c onfounding variable that can explain the results instead of the IV, it would be advisable to leave the section out.

- Suggest constructive ways to improve your study if appropriate.

- What are the implications of your findings? Say what your findings mean for how people behave in the real world.

- Suggest an idea for further research triggered by your study, something in the same area but not simply an improved version of yours. Perhaps you could base this on a limitation of your study.

- Concluding paragraph – Finish with a statement of your findings and the key points of the discussion (e.g., interpretation and implications) in no more than 3 or 4 sentences.

Reference Page

The reference section lists all the sources cited in the essay (alphabetically). It is not a bibliography (a list of the books you used).

In simple terms, every time you refer to a psychologist’s name (and date), you need to reference the original source of information.

If you have been using textbooks this is easy as the references are usually at the back of the book and you can just copy them down. If you have been using websites then you may have a problem as they might not provide a reference section for you to copy.

References need to be set out APA style :

Author, A. A. (year). Title of work . Location: Publisher.

Journal Articles

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Article title. Journal Title, volume number (issue number), page numbers

A simple way to write your reference section is to use Google scholar . Just type the name and date of the psychologist in the search box and click on the “cite” link.

Next, copy and paste the APA reference into the reference section of your essay.

Once again, remember that references need to be in alphabetical order according to surname.

Psychology Lab Report Example

Quantitative paper template.

Quantitative professional paper template: Adapted from “Fake News, Fast and Slow: Deliberation Reduces Belief in False (but Not True) News Headlines,” by B. Bago, D. G. Rand, and G. Pennycook, 2020, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General , 149 (8), pp. 1608–1613 ( https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000729 ). Copyright 2020 by the American Psychological Association.

Qualitative paper template

Qualitative professional paper template: Adapted from “‘My Smartphone Is an Extension of Myself’: A Holistic Qualitative Exploration of the Impact of Using a Smartphone,” by L. J. Harkin and D. Kuss, 2020, Psychology of Popular Media , 10 (1), pp. 28–38 ( https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000278 ). Copyright 2020 by the American Psychological Association.

Related Articles

Student Resources

How To Cite A YouTube Video In APA Style – With Examples

How to Write an Abstract APA Format

APA References Page Formatting and Example

APA Title Page (Cover Page) Format, Example, & Templates

How do I Cite a Source with Multiple Authors in APA Style?

How to Write a Psychology Essay

Scientific Reports

What this handout is about.

This handout provides a general guide to writing reports about scientific research you’ve performed. In addition to describing the conventional rules about the format and content of a lab report, we’ll also attempt to convey why these rules exist, so you’ll get a clearer, more dependable idea of how to approach this writing situation. Readers of this handout may also find our handout on writing in the sciences useful.

Background and pre-writing

Why do we write research reports.

You did an experiment or study for your science class, and now you have to write it up for your teacher to review. You feel that you understood the background sufficiently, designed and completed the study effectively, obtained useful data, and can use those data to draw conclusions about a scientific process or principle. But how exactly do you write all that? What is your teacher expecting to see?

To take some of the guesswork out of answering these questions, try to think beyond the classroom setting. In fact, you and your teacher are both part of a scientific community, and the people who participate in this community tend to share the same values. As long as you understand and respect these values, your writing will likely meet the expectations of your audience—including your teacher.

So why are you writing this research report? The practical answer is “Because the teacher assigned it,” but that’s classroom thinking. Generally speaking, people investigating some scientific hypothesis have a responsibility to the rest of the scientific world to report their findings, particularly if these findings add to or contradict previous ideas. The people reading such reports have two primary goals:

- They want to gather the information presented.

- They want to know that the findings are legitimate.

Your job as a writer, then, is to fulfill these two goals.

How do I do that?

Good question. Here is the basic format scientists have designed for research reports:

- Introduction

Methods and Materials

This format, sometimes called “IMRAD,” may take slightly different shapes depending on the discipline or audience; some ask you to include an abstract or separate section for the hypothesis, or call the Discussion section “Conclusions,” or change the order of the sections (some professional and academic journals require the Methods section to appear last). Overall, however, the IMRAD format was devised to represent a textual version of the scientific method.

The scientific method, you’ll probably recall, involves developing a hypothesis, testing it, and deciding whether your findings support the hypothesis. In essence, the format for a research report in the sciences mirrors the scientific method but fleshes out the process a little. Below, you’ll find a table that shows how each written section fits into the scientific method and what additional information it offers the reader.

Thinking of your research report as based on the scientific method, but elaborated in the ways described above, may help you to meet your audience’s expectations successfully. We’re going to proceed by explicitly connecting each section of the lab report to the scientific method, then explaining why and how you need to elaborate that section.

Although this handout takes each section in the order in which it should be presented in the final report, you may for practical reasons decide to compose sections in another order. For example, many writers find that composing their Methods and Results before the other sections helps to clarify their idea of the experiment or study as a whole. You might consider using each assignment to practice different approaches to drafting the report, to find the order that works best for you.

What should I do before drafting the lab report?

The best way to prepare to write the lab report is to make sure that you fully understand everything you need to about the experiment. Obviously, if you don’t quite know what went on during the lab, you’re going to find it difficult to explain the lab satisfactorily to someone else. To make sure you know enough to write the report, complete the following steps:

- What are we going to do in this lab? (That is, what’s the procedure?)

- Why are we going to do it that way?

- What are we hoping to learn from this experiment?

- Why would we benefit from this knowledge?

- Consult your lab supervisor as you perform the lab. If you don’t know how to answer one of the questions above, for example, your lab supervisor will probably be able to explain it to you (or, at least, help you figure it out).

- Plan the steps of the experiment carefully with your lab partners. The less you rush, the more likely it is that you’ll perform the experiment correctly and record your findings accurately. Also, take some time to think about the best way to organize the data before you have to start putting numbers down. If you can design a table to account for the data, that will tend to work much better than jotting results down hurriedly on a scrap piece of paper.

- Record the data carefully so you get them right. You won’t be able to trust your conclusions if you have the wrong data, and your readers will know you messed up if the other three people in your group have “97 degrees” and you have “87.”

- Consult with your lab partners about everything you do. Lab groups often make one of two mistakes: two people do all the work while two have a nice chat, or everybody works together until the group finishes gathering the raw data, then scrams outta there. Collaborate with your partners, even when the experiment is “over.” What trends did you observe? Was the hypothesis supported? Did you all get the same results? What kind of figure should you use to represent your findings? The whole group can work together to answer these questions.

- Consider your audience. You may believe that audience is a non-issue: it’s your lab TA, right? Well, yes—but again, think beyond the classroom. If you write with only your lab instructor in mind, you may omit material that is crucial to a complete understanding of your experiment, because you assume the instructor knows all that stuff already. As a result, you may receive a lower grade, since your TA won’t be sure that you understand all the principles at work. Try to write towards a student in the same course but a different lab section. That student will have a fair degree of scientific expertise but won’t know much about your experiment particularly. Alternatively, you could envision yourself five years from now, after the reading and lectures for this course have faded a bit. What would you remember, and what would you need explained more clearly (as a refresher)?

Once you’ve completed these steps as you perform the experiment, you’ll be in a good position to draft an effective lab report.

Introductions

How do i write a strong introduction.

For the purposes of this handout, we’ll consider the Introduction to contain four basic elements: the purpose, the scientific literature relevant to the subject, the hypothesis, and the reasons you believed your hypothesis viable. Let’s start by going through each element of the Introduction to clarify what it covers and why it’s important. Then we can formulate a logical organizational strategy for the section.

The inclusion of the purpose (sometimes called the objective) of the experiment often confuses writers. The biggest misconception is that the purpose is the same as the hypothesis. Not quite. We’ll get to hypotheses in a minute, but basically they provide some indication of what you expect the experiment to show. The purpose is broader, and deals more with what you expect to gain through the experiment. In a professional setting, the hypothesis might have something to do with how cells react to a certain kind of genetic manipulation, but the purpose of the experiment is to learn more about potential cancer treatments. Undergraduate reports don’t often have this wide-ranging a goal, but you should still try to maintain the distinction between your hypothesis and your purpose. In a solubility experiment, for example, your hypothesis might talk about the relationship between temperature and the rate of solubility, but the purpose is probably to learn more about some specific scientific principle underlying the process of solubility.

For starters, most people say that you should write out your working hypothesis before you perform the experiment or study. Many beginning science students neglect to do so and find themselves struggling to remember precisely which variables were involved in the process or in what way the researchers felt that they were related. Write your hypothesis down as you develop it—you’ll be glad you did.

As for the form a hypothesis should take, it’s best not to be too fancy or complicated; an inventive style isn’t nearly so important as clarity here. There’s nothing wrong with beginning your hypothesis with the phrase, “It was hypothesized that . . .” Be as specific as you can about the relationship between the different objects of your study. In other words, explain that when term A changes, term B changes in this particular way. Readers of scientific writing are rarely content with the idea that a relationship between two terms exists—they want to know what that relationship entails.

Not a hypothesis:

“It was hypothesized that there is a significant relationship between the temperature of a solvent and the rate at which a solute dissolves.”

Hypothesis:

“It was hypothesized that as the temperature of a solvent increases, the rate at which a solute will dissolve in that solvent increases.”

Put more technically, most hypotheses contain both an independent and a dependent variable. The independent variable is what you manipulate to test the reaction; the dependent variable is what changes as a result of your manipulation. In the example above, the independent variable is the temperature of the solvent, and the dependent variable is the rate of solubility. Be sure that your hypothesis includes both variables.

Justify your hypothesis

You need to do more than tell your readers what your hypothesis is; you also need to assure them that this hypothesis was reasonable, given the circumstances. In other words, use the Introduction to explain that you didn’t just pluck your hypothesis out of thin air. (If you did pluck it out of thin air, your problems with your report will probably extend beyond using the appropriate format.) If you posit that a particular relationship exists between the independent and the dependent variable, what led you to believe your “guess” might be supported by evidence?

Scientists often refer to this type of justification as “motivating” the hypothesis, in the sense that something propelled them to make that prediction. Often, motivation includes what we already know—or rather, what scientists generally accept as true (see “Background/previous research” below). But you can also motivate your hypothesis by relying on logic or on your own observations. If you’re trying to decide which solutes will dissolve more rapidly in a solvent at increased temperatures, you might remember that some solids are meant to dissolve in hot water (e.g., bouillon cubes) and some are used for a function precisely because they withstand higher temperatures (they make saucepans out of something). Or you can think about whether you’ve noticed sugar dissolving more rapidly in your glass of iced tea or in your cup of coffee. Even such basic, outside-the-lab observations can help you justify your hypothesis as reasonable.

Background/previous research

This part of the Introduction demonstrates to the reader your awareness of how you’re building on other scientists’ work. If you think of the scientific community as engaging in a series of conversations about various topics, then you’ll recognize that the relevant background material will alert the reader to which conversation you want to enter.

Generally speaking, authors writing journal articles use the background for slightly different purposes than do students completing assignments. Because readers of academic journals tend to be professionals in the field, authors explain the background in order to permit readers to evaluate the study’s pertinence for their own work. You, on the other hand, write toward a much narrower audience—your peers in the course or your lab instructor—and so you must demonstrate that you understand the context for the (presumably assigned) experiment or study you’ve completed. For example, if your professor has been talking about polarity during lectures, and you’re doing a solubility experiment, you might try to connect the polarity of a solid to its relative solubility in certain solvents. In any event, both professional researchers and undergraduates need to connect the background material overtly to their own work.

Organization of this section

Most of the time, writers begin by stating the purpose or objectives of their own work, which establishes for the reader’s benefit the “nature and scope of the problem investigated” (Day 1994). Once you have expressed your purpose, you should then find it easier to move from the general purpose, to relevant material on the subject, to your hypothesis. In abbreviated form, an Introduction section might look like this:

“The purpose of the experiment was to test conventional ideas about solubility in the laboratory [purpose] . . . According to Whitecoat and Labrat (1999), at higher temperatures the molecules of solvents move more quickly . . . We know from the class lecture that molecules moving at higher rates of speed collide with one another more often and thus break down more easily [background material/motivation] . . . Thus, it was hypothesized that as the temperature of a solvent increases, the rate at which a solute will dissolve in that solvent increases [hypothesis].”

Again—these are guidelines, not commandments. Some writers and readers prefer different structures for the Introduction. The one above merely illustrates a common approach to organizing material.

How do I write a strong Materials and Methods section?

As with any piece of writing, your Methods section will succeed only if it fulfills its readers’ expectations, so you need to be clear in your own mind about the purpose of this section. Let’s review the purpose as we described it above: in this section, you want to describe in detail how you tested the hypothesis you developed and also to clarify the rationale for your procedure. In science, it’s not sufficient merely to design and carry out an experiment. Ultimately, others must be able to verify your findings, so your experiment must be reproducible, to the extent that other researchers can follow the same procedure and obtain the same (or similar) results.

Here’s a real-world example of the importance of reproducibility. In 1989, physicists Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischman announced that they had discovered “cold fusion,” a way of producing excess heat and power without the nuclear radiation that accompanies “hot fusion.” Such a discovery could have great ramifications for the industrial production of energy, so these findings created a great deal of interest. When other scientists tried to duplicate the experiment, however, they didn’t achieve the same results, and as a result many wrote off the conclusions as unjustified (or worse, a hoax). To this day, the viability of cold fusion is debated within the scientific community, even though an increasing number of researchers believe it possible. So when you write your Methods section, keep in mind that you need to describe your experiment well enough to allow others to replicate it exactly.

With these goals in mind, let’s consider how to write an effective Methods section in terms of content, structure, and style.

Sometimes the hardest thing about writing this section isn’t what you should talk about, but what you shouldn’t talk about. Writers often want to include the results of their experiment, because they measured and recorded the results during the course of the experiment. But such data should be reserved for the Results section. In the Methods section, you can write that you recorded the results, or how you recorded the results (e.g., in a table), but you shouldn’t write what the results were—not yet. Here, you’re merely stating exactly how you went about testing your hypothesis. As you draft your Methods section, ask yourself the following questions:

- How much detail? Be precise in providing details, but stay relevant. Ask yourself, “Would it make any difference if this piece were a different size or made from a different material?” If not, you probably don’t need to get too specific. If so, you should give as many details as necessary to prevent this experiment from going awry if someone else tries to carry it out. Probably the most crucial detail is measurement; you should always quantify anything you can, such as time elapsed, temperature, mass, volume, etc.

- Rationale: Be sure that as you’re relating your actions during the experiment, you explain your rationale for the protocol you developed. If you capped a test tube immediately after adding a solute to a solvent, why did you do that? (That’s really two questions: why did you cap it, and why did you cap it immediately?) In a professional setting, writers provide their rationale as a way to explain their thinking to potential critics. On one hand, of course, that’s your motivation for talking about protocol, too. On the other hand, since in practical terms you’re also writing to your teacher (who’s seeking to evaluate how well you comprehend the principles of the experiment), explaining the rationale indicates that you understand the reasons for conducting the experiment in that way, and that you’re not just following orders. Critical thinking is crucial—robots don’t make good scientists.

- Control: Most experiments will include a control, which is a means of comparing experimental results. (Sometimes you’ll need to have more than one control, depending on the number of hypotheses you want to test.) The control is exactly the same as the other items you’re testing, except that you don’t manipulate the independent variable-the condition you’re altering to check the effect on the dependent variable. For example, if you’re testing solubility rates at increased temperatures, your control would be a solution that you didn’t heat at all; that way, you’ll see how quickly the solute dissolves “naturally” (i.e., without manipulation), and you’ll have a point of reference against which to compare the solutions you did heat.

Describe the control in the Methods section. Two things are especially important in writing about the control: identify the control as a control, and explain what you’re controlling for. Here is an example:

“As a control for the temperature change, we placed the same amount of solute in the same amount of solvent, and let the solution stand for five minutes without heating it.”

Structure and style

Organization is especially important in the Methods section of a lab report because readers must understand your experimental procedure completely. Many writers are surprised by the difficulty of conveying what they did during the experiment, since after all they’re only reporting an event, but it’s often tricky to present this information in a coherent way. There’s a fairly standard structure you can use to guide you, and following the conventions for style can help clarify your points.

- Subsections: Occasionally, researchers use subsections to report their procedure when the following circumstances apply: 1) if they’ve used a great many materials; 2) if the procedure is unusually complicated; 3) if they’ve developed a procedure that won’t be familiar to many of their readers. Because these conditions rarely apply to the experiments you’ll perform in class, most undergraduate lab reports won’t require you to use subsections. In fact, many guides to writing lab reports suggest that you try to limit your Methods section to a single paragraph.

- Narrative structure: Think of this section as telling a story about a group of people and the experiment they performed. Describe what you did in the order in which you did it. You may have heard the old joke centered on the line, “Disconnect the red wire, but only after disconnecting the green wire,” where the person reading the directions blows everything to kingdom come because the directions weren’t in order. We’re used to reading about events chronologically, and so your readers will generally understand what you did if you present that information in the same way. Also, since the Methods section does generally appear as a narrative (story), you want to avoid the “recipe” approach: “First, take a clean, dry 100 ml test tube from the rack. Next, add 50 ml of distilled water.” You should be reporting what did happen, not telling the reader how to perform the experiment: “50 ml of distilled water was poured into a clean, dry 100 ml test tube.” Hint: most of the time, the recipe approach comes from copying down the steps of the procedure from your lab manual, so you may want to draft the Methods section initially without consulting your manual. Later, of course, you can go back and fill in any part of the procedure you inadvertently overlooked.

- Past tense: Remember that you’re describing what happened, so you should use past tense to refer to everything you did during the experiment. Writers are often tempted to use the imperative (“Add 5 g of the solid to the solution”) because that’s how their lab manuals are worded; less frequently, they use present tense (“5 g of the solid are added to the solution”). Instead, remember that you’re talking about an event which happened at a particular time in the past, and which has already ended by the time you start writing, so simple past tense will be appropriate in this section (“5 g of the solid were added to the solution” or “We added 5 g of the solid to the solution”).

- Active: We heated the solution to 80°C. (The subject, “we,” performs the action, heating.)

- Passive: The solution was heated to 80°C. (The subject, “solution,” doesn’t do the heating–it is acted upon, not acting.)

Increasingly, especially in the social sciences, using first person and active voice is acceptable in scientific reports. Most readers find that this style of writing conveys information more clearly and concisely. This rhetorical choice thus brings two scientific values into conflict: objectivity versus clarity. Since the scientific community hasn’t reached a consensus about which style it prefers, you may want to ask your lab instructor.

How do I write a strong Results section?

Here’s a paradox for you. The Results section is often both the shortest (yay!) and most important (uh-oh!) part of your report. Your Materials and Methods section shows how you obtained the results, and your Discussion section explores the significance of the results, so clearly the Results section forms the backbone of the lab report. This section provides the most critical information about your experiment: the data that allow you to discuss how your hypothesis was or wasn’t supported. But it doesn’t provide anything else, which explains why this section is generally shorter than the others.

Before you write this section, look at all the data you collected to figure out what relates significantly to your hypothesis. You’ll want to highlight this material in your Results section. Resist the urge to include every bit of data you collected, since perhaps not all are relevant. Also, don’t try to draw conclusions about the results—save them for the Discussion section. In this section, you’re reporting facts. Nothing your readers can dispute should appear in the Results section.

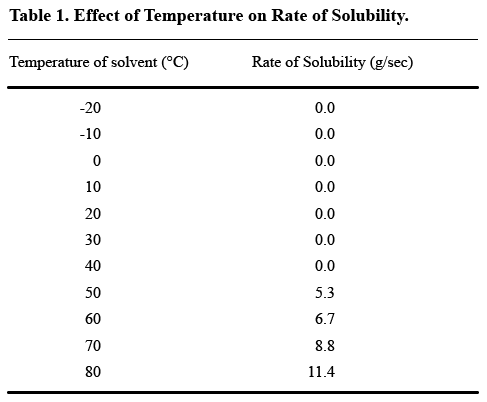

Most Results sections feature three distinct parts: text, tables, and figures. Let’s consider each part one at a time.

This should be a short paragraph, generally just a few lines, that describes the results you obtained from your experiment. In a relatively simple experiment, one that doesn’t produce a lot of data for you to repeat, the text can represent the entire Results section. Don’t feel that you need to include lots of extraneous detail to compensate for a short (but effective) text; your readers appreciate discrimination more than your ability to recite facts. In a more complex experiment, you may want to use tables and/or figures to help guide your readers toward the most important information you gathered. In that event, you’ll need to refer to each table or figure directly, where appropriate:

“Table 1 lists the rates of solubility for each substance”

“Solubility increased as the temperature of the solution increased (see Figure 1).”

If you do use tables or figures, make sure that you don’t present the same material in both the text and the tables/figures, since in essence you’ll just repeat yourself, probably annoying your readers with the redundancy of your statements.

Feel free to describe trends that emerge as you examine the data. Although identifying trends requires some judgment on your part and so may not feel like factual reporting, no one can deny that these trends do exist, and so they properly belong in the Results section. Example:

“Heating the solution increased the rate of solubility of polar solids by 45% but had no effect on the rate of solubility in solutions containing non-polar solids.”

This point isn’t debatable—you’re just pointing out what the data show.

As in the Materials and Methods section, you want to refer to your data in the past tense, because the events you recorded have already occurred and have finished occurring. In the example above, note the use of “increased” and “had,” rather than “increases” and “has.” (You don’t know from your experiment that heating always increases the solubility of polar solids, but it did that time.)

You shouldn’t put information in the table that also appears in the text. You also shouldn’t use a table to present irrelevant data, just to show you did collect these data during the experiment. Tables are good for some purposes and situations, but not others, so whether and how you’ll use tables depends upon what you need them to accomplish.

Tables are useful ways to show variation in data, but not to present a great deal of unchanging measurements. If you’re dealing with a scientific phenomenon that occurs only within a certain range of temperatures, for example, you don’t need to use a table to show that the phenomenon didn’t occur at any of the other temperatures. How useful is this table?

As you can probably see, no solubility was observed until the trial temperature reached 50°C, a fact that the text part of the Results section could easily convey. The table could then be limited to what happened at 50°C and higher, thus better illustrating the differences in solubility rates when solubility did occur.

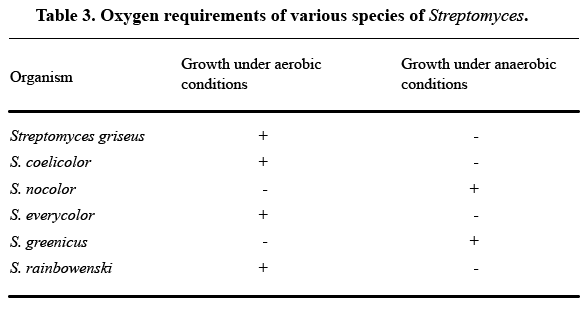

As a rule, try not to use a table to describe any experimental event you can cover in one sentence of text. Here’s an example of an unnecessary table from How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper , by Robert A. Day:

As Day notes, all the information in this table can be summarized in one sentence: “S. griseus, S. coelicolor, S. everycolor, and S. rainbowenski grew under aerobic conditions, whereas S. nocolor and S. greenicus required anaerobic conditions.” Most readers won’t find the table clearer than that one sentence.

When you do have reason to tabulate material, pay attention to the clarity and readability of the format you use. Here are a few tips:

- Number your table. Then, when you refer to the table in the text, use that number to tell your readers which table they can review to clarify the material.

- Give your table a title. This title should be descriptive enough to communicate the contents of the table, but not so long that it becomes difficult to follow. The titles in the sample tables above are acceptable.

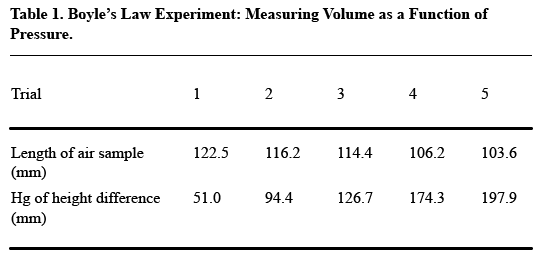

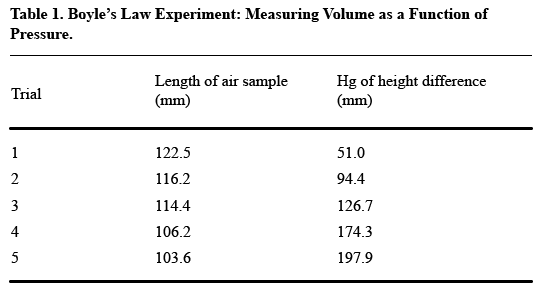

- Arrange your table so that readers read vertically, not horizontally. For the most part, this rule means that you should construct your table so that like elements read down, not across. Think about what you want your readers to compare, and put that information in the column (up and down) rather than in the row (across). Usually, the point of comparison will be the numerical data you collect, so especially make sure you have columns of numbers, not rows.Here’s an example of how drastically this decision affects the readability of your table (from A Short Guide to Writing about Chemistry , by Herbert Beall and John Trimbur). Look at this table, which presents the relevant data in horizontal rows:

It’s a little tough to see the trends that the author presumably wants to present in this table. Compare this table, in which the data appear vertically:

The second table shows how putting like elements in a vertical column makes for easier reading. In this case, the like elements are the measurements of length and height, over five trials–not, as in the first table, the length and height measurements for each trial.

- Make sure to include units of measurement in the tables. Readers might be able to guess that you measured something in millimeters, but don’t make them try.

- Don’t use vertical lines as part of the format for your table. This convention exists because journals prefer not to have to reproduce these lines because the tables then become more expensive to print. Even though it’s fairly unlikely that you’ll be sending your Biology 11 lab report to Science for publication, your readers still have this expectation. Consequently, if you use the table-drawing option in your word-processing software, choose the option that doesn’t rely on a “grid” format (which includes vertical lines).

How do I include figures in my report?

Although tables can be useful ways of showing trends in the results you obtained, figures (i.e., illustrations) can do an even better job of emphasizing such trends. Lab report writers often use graphic representations of the data they collected to provide their readers with a literal picture of how the experiment went.

When should you use a figure?

Remember the circumstances under which you don’t need a table: when you don’t have a great deal of data or when the data you have don’t vary a lot. Under the same conditions, you would probably forgo the figure as well, since the figure would be unlikely to provide your readers with an additional perspective. Scientists really don’t like their time wasted, so they tend not to respond favorably to redundancy.

If you’re trying to decide between using a table and creating a figure to present your material, consider the following a rule of thumb. The strength of a table lies in its ability to supply large amounts of exact data, whereas the strength of a figure is its dramatic illustration of important trends within the experiment. If you feel that your readers won’t get the full impact of the results you obtained just by looking at the numbers, then a figure might be appropriate.

Of course, an undergraduate class may expect you to create a figure for your lab experiment, if only to make sure that you can do so effectively. If this is the case, then don’t worry about whether to use figures or not—concentrate instead on how best to accomplish your task.

Figures can include maps, photographs, pen-and-ink drawings, flow charts, bar graphs, and section graphs (“pie charts”). But the most common figure by far, especially for undergraduates, is the line graph, so we’ll focus on that type in this handout.

At the undergraduate level, you can often draw and label your graphs by hand, provided that the result is clear, legible, and drawn to scale. Computer technology has, however, made creating line graphs a lot easier. Most word-processing software has a number of functions for transferring data into graph form; many scientists have found Microsoft Excel, for example, a helpful tool in graphing results. If you plan on pursuing a career in the sciences, it may be well worth your while to learn to use a similar program.

Computers can’t, however, decide for you how your graph really works; you have to know how to design your graph to meet your readers’ expectations. Here are some of these expectations:

- Keep it as simple as possible. You may be tempted to signal the complexity of the information you gathered by trying to design a graph that accounts for that complexity. But remember the purpose of your graph: to dramatize your results in a manner that’s easy to see and grasp. Try not to make the reader stare at the graph for a half hour to find the important line among the mass of other lines. For maximum effectiveness, limit yourself to three to five lines per graph; if you have more data to demonstrate, use a set of graphs to account for it, rather than trying to cram it all into a single figure.

- Plot the independent variable on the horizontal (x) axis and the dependent variable on the vertical (y) axis. Remember that the independent variable is the condition that you manipulated during the experiment and the dependent variable is the condition that you measured to see if it changed along with the independent variable. Placing the variables along their respective axes is mostly just a convention, but since your readers are accustomed to viewing graphs in this way, you’re better off not challenging the convention in your report.

- Label each axis carefully, and be especially careful to include units of measure. You need to make sure that your readers understand perfectly well what your graph indicates.

- Number and title your graphs. As with tables, the title of the graph should be informative but concise, and you should refer to your graph by number in the text (e.g., “Figure 1 shows the increase in the solubility rate as a function of temperature”).

- Many editors of professional scientific journals prefer that writers distinguish the lines in their graphs by attaching a symbol to them, usually a geometric shape (triangle, square, etc.), and using that symbol throughout the curve of the line. Generally, readers have a hard time distinguishing dotted lines from dot-dash lines from straight lines, so you should consider staying away from this system. Editors don’t usually like different-colored lines within a graph because colors are difficult and expensive to reproduce; colors may, however, be great for your purposes, as long as you’re not planning to submit your paper to Nature. Use your discretion—try to employ whichever technique dramatizes the results most effectively.

- Try to gather data at regular intervals, so the plot points on your graph aren’t too far apart. You can’t be sure of the arc you should draw between the plot points if the points are located at the far corners of the graph; over a fifteen-minute interval, perhaps the change occurred in the first or last thirty seconds of that period (in which case your straight-line connection between the points is misleading).

- If you’re worried that you didn’t collect data at sufficiently regular intervals during your experiment, go ahead and connect the points with a straight line, but you may want to examine this problem as part of your Discussion section.

- Make your graph large enough so that everything is legible and clearly demarcated, but not so large that it either overwhelms the rest of the Results section or provides a far greater range than you need to illustrate your point. If, for example, the seedlings of your plant grew only 15 mm during the trial, you don’t need to construct a graph that accounts for 100 mm of growth. The lines in your graph should more or less fill the space created by the axes; if you see that your data is confined to the lower left portion of the graph, you should probably re-adjust your scale.

- If you create a set of graphs, make them the same size and format, including all the verbal and visual codes (captions, symbols, scale, etc.). You want to be as consistent as possible in your illustrations, so that your readers can easily make the comparisons you’re trying to get them to see.

How do I write a strong Discussion section?

The discussion section is probably the least formalized part of the report, in that you can’t really apply the same structure to every type of experiment. In simple terms, here you tell your readers what to make of the Results you obtained. If you have done the Results part well, your readers should already recognize the trends in the data and have a fairly clear idea of whether your hypothesis was supported. Because the Results can seem so self-explanatory, many students find it difficult to know what material to add in this last section.

Basically, the Discussion contains several parts, in no particular order, but roughly moving from specific (i.e., related to your experiment only) to general (how your findings fit in the larger scientific community). In this section, you will, as a rule, need to:

Explain whether the data support your hypothesis

- Acknowledge any anomalous data or deviations from what you expected

Derive conclusions, based on your findings, about the process you’re studying

- Relate your findings to earlier work in the same area (if you can)

Explore the theoretical and/or practical implications of your findings

Let’s look at some dos and don’ts for each of these objectives.

This statement is usually a good way to begin the Discussion, since you can’t effectively speak about the larger scientific value of your study until you’ve figured out the particulars of this experiment. You might begin this part of the Discussion by explicitly stating the relationships or correlations your data indicate between the independent and dependent variables. Then you can show more clearly why you believe your hypothesis was or was not supported. For example, if you tested solubility at various temperatures, you could start this section by noting that the rates of solubility increased as the temperature increased. If your initial hypothesis surmised that temperature change would not affect solubility, you would then say something like,

“The hypothesis that temperature change would not affect solubility was not supported by the data.”

Note: Students tend to view labs as practical tests of undeniable scientific truths. As a result, you may want to say that the hypothesis was “proved” or “disproved” or that it was “correct” or “incorrect.” These terms, however, reflect a degree of certainty that you as a scientist aren’t supposed to have. Remember, you’re testing a theory with a procedure that lasts only a few hours and relies on only a few trials, which severely compromises your ability to be sure about the “truth” you see. Words like “supported,” “indicated,” and “suggested” are more acceptable ways to evaluate your hypothesis.

Also, recognize that saying whether the data supported your hypothesis or not involves making a claim to be defended. As such, you need to show the readers that this claim is warranted by the evidence. Make sure that you’re very explicit about the relationship between the evidence and the conclusions you draw from it. This process is difficult for many writers because we don’t often justify conclusions in our regular lives. For example, you might nudge your friend at a party and whisper, “That guy’s drunk,” and once your friend lays eyes on the person in question, she might readily agree. In a scientific paper, by contrast, you would need to defend your claim more thoroughly by pointing to data such as slurred words, unsteady gait, and the lampshade-as-hat. In addition to pointing out these details, you would also need to show how (according to previous studies) these signs are consistent with inebriation, especially if they occur in conjunction with one another. To put it another way, tell your readers exactly how you got from point A (was the hypothesis supported?) to point B (yes/no).

Acknowledge any anomalous data, or deviations from what you expected

You need to take these exceptions and divergences into account, so that you qualify your conclusions sufficiently. For obvious reasons, your readers will doubt your authority if you (deliberately or inadvertently) overlook a key piece of data that doesn’t square with your perspective on what occurred. In a more philosophical sense, once you’ve ignored evidence that contradicts your claims, you’ve departed from the scientific method. The urge to “tidy up” the experiment is often strong, but if you give in to it you’re no longer performing good science.

Sometimes after you’ve performed a study or experiment, you realize that some part of the methods you used to test your hypothesis was flawed. In that case, it’s OK to suggest that if you had the chance to conduct your test again, you might change the design in this or that specific way in order to avoid such and such a problem. The key to making this approach work, though, is to be very precise about the weakness in your experiment, why and how you think that weakness might have affected your data, and how you would alter your protocol to eliminate—or limit the effects of—that weakness. Often, inexperienced researchers and writers feel the need to account for “wrong” data (remember, there’s no such animal), and so they speculate wildly about what might have screwed things up. These speculations include such factors as the unusually hot temperature in the room, or the possibility that their lab partners read the meters wrong, or the potentially defective equipment. These explanations are what scientists call “cop-outs,” or “lame”; don’t indicate that the experiment had a weakness unless you’re fairly certain that a) it really occurred and b) you can explain reasonably well how that weakness affected your results.

If, for example, your hypothesis dealt with the changes in solubility at different temperatures, then try to figure out what you can rationally say about the process of solubility more generally. If you’re doing an undergraduate lab, chances are that the lab will connect in some way to the material you’ve been covering either in lecture or in your reading, so you might choose to return to these resources as a way to help you think clearly about the process as a whole.

This part of the Discussion section is another place where you need to make sure that you’re not overreaching. Again, nothing you’ve found in one study would remotely allow you to claim that you now “know” something, or that something isn’t “true,” or that your experiment “confirmed” some principle or other. Hesitate before you go out on a limb—it’s dangerous! Use less absolutely conclusive language, including such words as “suggest,” “indicate,” “correspond,” “possibly,” “challenge,” etc.

Relate your findings to previous work in the field (if possible)

We’ve been talking about how to show that you belong in a particular community (such as biologists or anthropologists) by writing within conventions that they recognize and accept. Another is to try to identify a conversation going on among members of that community, and use your work to contribute to that conversation. In a larger philosophical sense, scientists can’t fully understand the value of their research unless they have some sense of the context that provoked and nourished it. That is, you have to recognize what’s new about your project (potentially, anyway) and how it benefits the wider body of scientific knowledge. On a more pragmatic level, especially for undergraduates, connecting your lab work to previous research will demonstrate to the TA that you see the big picture. You have an opportunity, in the Discussion section, to distinguish yourself from the students in your class who aren’t thinking beyond the barest facts of the study. Capitalize on this opportunity by putting your own work in context.

If you’re just beginning to work in the natural sciences (as a first-year biology or chemistry student, say), most likely the work you’ll be doing has already been performed and re-performed to a satisfactory degree. Hence, you could probably point to a similar experiment or study and compare/contrast your results and conclusions. More advanced work may deal with an issue that is somewhat less “resolved,” and so previous research may take the form of an ongoing debate, and you can use your own work to weigh in on that debate. If, for example, researchers are hotly disputing the value of herbal remedies for the common cold, and the results of your study suggest that Echinacea diminishes the symptoms but not the actual presence of the cold, then you might want to take some time in the Discussion section to recapitulate the specifics of the dispute as it relates to Echinacea as an herbal remedy. (Consider that you have probably already written in the Introduction about this debate as background research.)