If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

World history

Course: world history > unit 4, an introduction to the protestant reformation.

- Introduction to the Protestant Reformation: Setting the stage

- Introduction to the Protestant Reformation: Martin Luther

- Introduction to the Protestant Reformation: Varieties of Protestantism

- Introduction to the Protestant Reformation: The Counter-Reformation

- Read + Discuss

- Protestant Reformation

- Cranach, Law and Gospel (Law and Grace)

- Cranach, Law and Gospel

The Protestant Reformation

The church and the state, martin luther, indulgences, faith alone, scripture alone, the counter-reformation, the council of trent, selected outcomes of the council of trent:.

- The Council denied the Lutheran idea of justification by faith. They affirmed, in other words, their Doctrine of Merit, which allows human beings to redeem themselves through Good Works, and through the sacraments.

- They affirmed the existence of Purgatory and the usefulness of prayer and indulgences in shortening a person's stay in purgatory.

- They reaffirmed the belief in transubstantiation and the importance of all seven sacraments

- They reaffirmed the authority of scripture and the teachings and traditions of the Church

- They reaffirmed the necessity and correctness of religious art (see below)

The Council of Trent on Religious Art

Other developments, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

The reformation.

Erasmus of Rotterdam

Hans Holbein the Younger (and Workshop(?))

Martin Luther (1483–1546)

Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder

- The Last Supper

Designed by Bernard van Orley

The Fifteen Mysteries and the Virgin of the Rosary

Netherlandish (Brussels) Painter

Albrecht Dürer

Four Scenes from the Passion

Follower of Bernard van Orley

Friedrich III (1463–1525), the Wise, Elector of Saxony

Lucas Cranach the Elder and Workshop

Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Johann I (1468–1532), the Constant, Elector of Saxony

The Last Judgment

Joos van Cleve

Chancellor Leonhard von Eck (1480–1550)

Barthel Beham

Anne de Pisseleu (1508–1576), Duchesse d'Étampes

Attributed to Corneille de Lyon

Virgin and Child with Saint Anne

Christ and the Adulteress

Lucas Cranach the Younger and Workshop

The Calling of Saint Matthew

Copy after Jan Sanders van Hemessen

Christ Blessing the Children

Satire on the Papacy

Melchior Lorck

Christ Blessing, Surrounded by a Donor Family

German Painter

Jacob Wisse Stern College for Women, Yeshiva University

October 2002

Unleashed in the early sixteenth century, the Reformation put an abrupt end to the relative unity that had existed for the previous thousand years in Western Christendom under the Roman Catholic Church . The Reformation, which began in Germany but spread quickly throughout Europe, was initiated in response to the growing sense of corruption and administrative abuse in the church. It expressed an alternate vision of Christian practice, and led to the creation and rise of Protestantism, with all its individual branches. Images, especially, became effective tools for disseminating negative portrayals of the church ( 53.677.5 ), and for popularizing Reformation ideas; art, in turn, was revolutionized by the movement.

Though rooted in a broad dissatisfaction with the church, the birth of the Reformation can be traced to the protests of one man, the German Augustinian monk Martin Luther (1483–1546) ( 20.64.21 ; 55.220.2 ). In 1517, he nailed to a church door in Wittenberg, Saxony, a manifesto listing ninety-five arguments, or Theses, against the use and abuse of indulgences, which were official pardons for sins granted after guilt had been forgiven through penance. Particularly objectionable to the reformers was the selling of indulgences, which essentially allowed sinners to buy their way into heaven, and which, from the beginning of the sixteenth century, had become common practice. But, more fundamentally, Luther questioned basic tenets of the Roman Church, including the clergy’s exclusive right to grant salvation. He believed human salvation depended on individual faith, not on clerical mediation, and conceived of the Bible as the ultimate and sole source of Christian truth. He also advocated the abolition of monasteries and criticized the church’s materialistic use of art. Luther was excommunicated in 1520, but was granted protection by the elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise (r. 1483–1525) ( 46.179.1 ), and given safe conduct to the Imperial Diet in Worms and then asylum in Wartburg.

The movement Luther initiated spread and grew in popularity—especially in Northern Europe, though reaction to the protests against the church varied from country to country. In 1529, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V tried, for the most part unsuccessfully, to stamp out dissension among German Catholics. Elector John the Constant (r. 1525–32) ( 46.179.2 ), Frederick’s brother and successor, was actively hostile to the emperor and one of the fiercest defenders of Protestantism. By the middle of the century, most of north and west Germany had become Protestant. King Henry VIII of England (r. 1509–47), who had been a steadfast Catholic, broke with the church over the pope’s refusal to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, the first of Henry’s six wives. With the Act of Supremacy in 1534, Henry was made head of the Church of England, a title that would be shared by all future kings. John Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536) codified the doctrines of the new faith, becoming the basis for Presbyterianism. In the moderate camp, Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (ca. 1466–1536), though an opponent of the Reformation, remained committed to the reconciliation of Catholics and Protestants—an ideal that would be at least partially realized in 1555 with the Religious Peace of Augsburg, a ruling by the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire granting freedom of worship to Protestants.

With recognition of the reformers’ criticism and acceptance of their ideology, Protestants were able to put their beliefs on display in art ( 17.190.13–15 ). Artists sympathetic to the movement developed a new repertoire of subjects, or adapted traditional ones, to reflect and emphasize Protestant ideals and teaching ( 1982.60.35 ; 1982.60.36 ; 71.155 ; 1975.1.1915 ). More broadly, the balance of power gradually shifted from religious to secular authorities in western Europe, initiating a decline of Christian imagery in the Protestant Church. Meanwhile, the Roman Church mounted the Counter-Reformation, through which it denounced Lutheranism and reaffirmed Catholic doctrine. In Italy and Spain, the Counter-Reformation had an immense impact on the visual arts; while in the North , the sound made by the nails driven through Luther’s manifesto continued to reverberate.

Wisse, Jacob. “The Reformation.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/refo/hd_refo.htm (October 2002)

Further Reading

Coulton, G. G. Art and the Reformation . 2d ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1953.

Koerner, Joseph Leo. The Reformation of the Image . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Additional Essays by Jacob Wisse

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Northern Mannerism in the Early Sixteenth Century .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Prague during the Rule of Rudolf II (1583–1612) .” (November 2013)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Burgundian Netherlands: Court Life and Patronage .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Burgundian Netherlands: Private Life .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525–1569) .” (October 2002)

Related Essays

- Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

- Baroque Rome

- Elizabethan England

- The Papacy and the Vatican Palace

- The Papacy during the Renaissance

- Abraham and David Roentgen

- Ceramics in the French Renaissance

- The Crucifixion and Passion of Christ in Italian Painting

- European Tapestry Production and Patronage, 1400–1600

- Genre Painting in Northern Europe

- The Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburgs, 1400–1600

- How Medieval and Renaissance Tapestries Were Made

- Late Medieval German Sculpture: Images for the Cult and for Private Devotion

- Monasticism in Western Medieval Europe

- Music in the Renaissance

- Northern Mannerism in the Early Sixteenth Century

- Painting the Life of Christ in Medieval and Renaissance Italy

- Pastoral Charms in the French Renaissance

- Patronage at the Later Valois Courts (1461–1589)

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525–1569)

- Portrait Painting in England, 1600–1800

- Portraiture in Renaissance and Baroque Europe

- Profane Love and Erotic Art in the Italian Renaissance

- Sixteenth-Century Painting in Lombardy

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Europe

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1400–1600 A.D.

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1600–1800 A.D.

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1400–1600 A.D.

- France, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Rome and Southern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- 17th Century A.D.

- The Annunciation

- Baroque Art

- Central Europe

- Central Italy

- Christianity

- The Crucifixion

- Gilt Silver

- Great Britain and Ireland

- High Renaissance

- Holy Roman Empire

- Literature / Poetry

- Madonna and Child

- Monasticism

- The Nativity

- The Netherlands

- Northern Italy

- Printmaking

- Religious Art

- Renaissance Art

- Southern Italy

- Virgin Mary

Artist or Maker

- Beham, Barthel

- Cranach, Lucas, the Elder

- Cranach, Lucas, the Younger

- Daucher, Hans

- De Lyon, Corneille

- De Pannemaker, Pieter

- Dürer, Albrecht

- Holbein, Hans, the Younger

- Tom Ring, Ludger, the Younger

- Van Cleve, Joos

- Van Der Weyden, Goswijn

- Van Hemessen, Jan Sanders

- Van Orley, Bernard

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How Martin Luther Changed the World

By Joan Acocella

Clang! Clang! Down the corridors of religious history we hear this sound: Martin Luther, an energetic thirty-three-year-old Augustinian friar, hammering his Ninety-five Theses to the doors of the Castle Church of Wittenberg, in Saxony, and thus, eventually, splitting the thousand-year-old Roman Catholic Church into two churches—one loyal to the Pope in Rome, the other protesting against the Pope’s rule and soon, in fact, calling itself Protestant. This month marks the five-hundredth anniversary of Luther’s famous action. Accordingly, a number of books have come out, reconsidering the man and his influence. They differ on many points, but something that most of them agree on is that the hammering episode, so satisfying symbolically—loud, metallic, violent—never occurred. Not only were there no eyewitnesses; Luther himself, ordinarily an enthusiastic self-dramatizer, was vague on what had happened. He remembered drawing up a list of ninety-five theses around the date in question, but, as for what he did with it, all he was sure of was that he sent it to the local archbishop. Furthermore, the theses were not, as is often imagined, a set of non-negotiable demands about how the Church should reform itself in accordance with Brother Martin’s standards. Rather, like all “theses” in those days, they were points to be thrashed out in public disputations, in the manner of the ecclesiastical scholars of the twelfth century or, for that matter, the debate clubs of tradition-minded universities in our own time.

If the Ninety-five Theses sprouted a myth, that is no surprise. Luther was one of those figures who touched off something much larger than himself; namely, the Reformation—the sundering of the Church and a fundamental revision of its theology. Once he had divided the Church, it could not be healed. His reforms survived to breed other reforms, many of which he disapproved of. His church splintered and splintered. To tote up the Protestant denominations discussed in Alec Ryrie’s new book, “ Protestants ” (Viking), is almost comical, there are so many of them. That means a lot of people, though. An eighth of the human race is now Protestant.

The Reformation, in turn, reshaped Europe. As German-speaking lands asserted their independence from Rome, other forces were unleashed. In the Knights’ Revolt of 1522, and the Peasants’ War, a couple of years later, minor gentry and impoverished agricultural workers saw Protestantism as a way of redressing social grievances. (More than eighty thousand poorly armed peasants were slaughtered when the latter rebellion failed.) Indeed, the horrific Thirty Years’ War, in which, basically, Europe’s Roman Catholics killed all the Protestants they could, and vice versa, can in some measure be laid at Luther’s door. Although it did not begin until decades after his death, it arose in part because he had created no institutional structure to replace the one he walked away from.

Almost as soon as Luther started the Reformation, alternative Reformations arose in other localities. From town to town, preachers told the citizenry what it should no longer put up with, whereupon they stood a good chance of being shoved aside—indeed, strung up—by other preachers. Religious houses began to close down. Luther led the movement mostly by his writings. Meanwhile, he did what he thought was his main job in life, teaching the Bible at the University of Wittenberg. The Reformation wasn’t led, exactly; it just spread, metastasized.

And that was because Europe was so ready for it. The relationship between the people and the rulers could hardly have been worse. Maximilian I, the Holy Roman Emperor, was dying—he brought his coffin with him wherever he travelled—but he was taking his time about it. The presumptive heir, King Charles I of Spain, was looked upon with grave suspicion. He already had Spain and the Netherlands. Why did he need the Holy Roman Empire as well? Furthermore, he was young—only seventeen when Luther wrote the Ninety-five Theses. The biggest trouble, though, was money. The Church had incurred enormous expenses. It was warring with the Turks at the walls of Vienna. It had also started an ambitious building campaign, including the reconstruction of St. Peter’s Basilica, in Rome. To pay for these ventures, it had borrowed huge sums from Europe’s banks, and to repay the banks it was strangling the people with taxes.

It has often been said that, fundamentally, Luther gave us “modernity.” Among the recent studies, Eric Metaxas’s “ Martin Luther: The Man Who Rediscovered God and Changed the World ” (Viking) makes this claim in grandiose terms. “The quintessentially modern idea of the individual was as unthinkable before Luther as is color in a world of black and white,” he writes. “And the more recent ideas of pluralism, religious liberty, self-government, and liberty all entered history through the door that Luther opened.” The other books are more reserved. As they point out, Luther wanted no part of pluralism—even for the time, he was vehemently anti-Semitic—and not much part of individualism. People were to believe and act as their churches dictated.

The fact that Luther’s protest, rather than others that preceded it, brought about the Reformation is probably due in large measure to his outsized personality. He was a charismatic man, and maniacally energetic. Above all, he was intransigent. To oppose was his joy. And though at times he showed that hankering for martyrdom that we detect, with distaste, in the stories of certain religious figures, it seems that, most of the time, he just got out of bed in the morning and got on with his work. Among other things, he translated the New Testament from Greek into German in eleven weeks.

Luther was born in 1483 and grew up in Mansfeld, a small mining town in Saxony. His father started out as a miner but soon rose to become a master smelter, a specialist in separating valuable metal (in this case, copper) from ore. The family was not poor. Archeologists have been at work in their basement. The Luthers ate suckling pig and owned drinking glasses. They had either seven or eight children, of whom five survived. The father wanted Martin, the eldest, to study law, in order to help him in his business, but Martin disliked law school and promptly had one of those experiences often undergone in the old days by young people who did not wish to take their parents’ career advice. Caught in a violent thunderstorm one day in 1505—he was twenty-one—he vowed to St. Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary, that if he survived he would become a monk. He kept his promise, and was ordained two years later. In the heavily psychoanalytic nineteen-fifties, much was made of the idea that this flouting of his father’s wishes set the stage for his rebellion against the Holy Father in Rome. Such is the main point of Erik Erikson’s 1958 book, “ Young Man Luther ,” which became the basis of a famous play by John Osborne (filmed, in 1974, with Stacy Keach in the title role).

Today, psychoanalytic interpretations tend to be tittered at by Luther biographers. But the desire to find some great psychological source, or even a middle-sized one, for Luther’s great story is understandable, because, for many years, nothing much happened to him. This man who changed the world left his German-speaking lands only once in his life. (In 1510, he was part of a mission sent to Rome to heal a rent in the Augustinian order. It failed.) Most of his youth was spent in dirty little towns where men worked long hours each day and then, at night, went to the tavern and got into fights. He described his university town, Erfurt, as consisting of “a whorehouse and a beerhouse.” Wittenberg, where he lived for the remainder of his life, was bigger—with two thousand inhabitants when he settled there—but not much better. As Lyndal Roper, one of the best of the new biographers, writes, in “ Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet ” (Random House), it was a mess of “muddy houses, unclean lanes.” At that time, however, the new ruler of Saxony, Frederick the Wise, was trying to make a real city of it. He built a castle and a church—the one on whose door the famous theses were supposedly nailed—and he hired an important artist, Lucas Cranach the Elder, as his court painter. Most important, he founded a university, and staffed it with able scholars, including Johann von Staupitz, the vicar-general of the Augustinian friars of the German-speaking territories. Staupitz had been Luther’s confessor at Erfurt, and when he found himself overworked at Wittenberg he summoned Luther, persuaded him to take a doctorate, and handed over many of his duties to him. Luther supervised everything from monasteries (eleven of them) to fish ponds, but most crucial was his succeeding Staupitz as the university’s professor of the Bible, a job that he took on at the age of twenty-eight and retained until his death. In this capacity, he lectured on Scripture, held disputations, and preached to the staff of the university.

He was apparently a galvanizing speaker, but during his first twelve years as a monk he published almost nothing. This was no doubt due in part to the responsibilities heaped on him at Wittenberg, but at this time, and for a long time, he also suffered what seems to have been a severe psychospiritual crisis. He called his problem his Anfechtungen —trials, tribulations—but this feels too slight a word to cover the afflictions he describes: cold sweats, nausea, constipation, crushing headaches, ringing in his ears, together with depression, anxiety, and a general feeling that, as he put it, the angel of Satan was beating him with his fists. Most painful, it seems, for this passionately religious young man was to discover his anger against God. Years later, commenting on his reading of Scripture as a young friar, Luther spoke of his rage at the description of God’s righteousness, and of his grief that, as he was certain, he would not be judged worthy: “I did not love, yes, I hated the righteous God who punishes sinners.”

There were good reasons for an intense young priest to feel disillusioned. One of the most bitterly resented abuses of the Church at that time was the so-called indulgences, a kind of late-medieval get-out-of-jail-free card used by the Church to make money. When a Christian purchased an indulgence from the Church, he obtained—for himself or whomever else he was trying to benefit—a reduction in the amount of time the person’s soul had to spend in Purgatory, atoning for his sins, before ascending to Heaven. You might pay to have a special Mass said for the sinner or, less expensively, you could buy candles or new altar cloths for the church. But, in the most common transaction, the purchaser simply paid an agreed-upon amount of money and, in return, was given a document saying that the beneficiary—the name was written in on a printed form—was forgiven x amount of time in Purgatory. The more time off, the more it cost, but the indulgence-sellers promised that whatever you paid for you got.

Actually, they could change their minds about that. In 1515, the Church cancelled the exculpatory powers of already purchased indulgences for the next eight years. If you wanted that period covered, you had to buy a new indulgence. Realizing that this was hard on people—essentially, they had wasted their money—the Church declared that purchasers of the new indulgences did not have to make confession or even exhibit contrition. They just had to hand over the money and the thing was done, because this new issue was especially powerful. Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar locally famous for his zeal in selling indulgences, is said to have boasted that one of the new ones could obtain remission from sin even for someone who had raped the Virgin Mary. (In the 1974 movie “ Luther ,” Tetzel is played with a wonderful, bug-eyed wickedness by Hugh Griffith.) Even by the standards of the very corrupt sixteenth-century Church, this was shocking.

In Luther’s mind, the indulgence trade seems to have crystallized the spiritual crisis he was experiencing. It brought him up against the absurdity of bargaining with God, jockeying for his favor—indeed, paying for his favor. Why had God given his only begotten son? And why had the son died on the cross? Because that’s how much God loved the world. And that alone, Luther now reasoned, was sufficient for a person to be found “justified,” or worthy. From this thought, the Ninety-five Theses were born. Most of them were challenges to the sale of indulgences. And out of them came what would be the two guiding principles of Luther’s theology: sola fide and sola scriptura .

Sola fide means “by faith alone”—faith, as opposed to good works, as the basis for salvation. This was not a new idea. St. Augustine, the founder of Luther’s monastic order, laid it out in the fourth century. Furthermore, it is not an idea that fits well with what we know of Luther. Pure faith, contemplation, white light: surely these are the gifts of the Asian religions, or of medieval Christianity, of St. Francis with his birds. As for Luther, with his rages and sweats, does he seem a good candidate? Eventually, however, he discovered (with lapses) that he could be released from those torments by the simple act of accepting God’s love for him. Lest it be thought that this stern man then concluded that we could stop worrying about our behavior and do whatever we wanted, he said that works issue from faith. In his words, “We can no more separate works from faith than heat and light from fire.” But he did believe that the world was irretrievably full of sin, and that repairing that situation was not the point of our moral lives. “Be a sinner, and let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger,” he wrote to a friend.

The second great principle, sola scriptura , or “by scripture alone,” was the belief that only the Bible could tell us the truth. Like sola fide , this was a rejection of what, to Luther, were the lies of the Church—symbolized most of all by the indulgence market. Indulgences brought you an abbreviation of your stay in Purgatory, but what was Purgatory? No such thing is mentioned in the Bible. Some people think that Dante made it up; others say Gregory the Great. In any case, Luther decided that somebody made it up.

Guided by those convictions, and fired by his new certainty of God’s love for him, Luther became radicalized. He preached, he disputed. Above all, he wrote pamphlets. He denounced not only the indulgence trade but all the other ways in which the Church made money off Christians: the endless pilgrimages, the yearly Masses for the dead, the cults of the saints. He questioned the sacraments. His arguments made sense to many people, notably Frederick the Wise. Frederick was pained that Saxony was widely considered a backwater. He now saw how much attention Luther brought to his state, and how much respect accrued to the university that he (Frederick) had founded at Wittenberg. He vowed to protect this troublemaker.

Things came to a head in 1520. By then, Luther had taken to calling the Church a brothel, and Pope Leo X the Antichrist. Leo gave Luther sixty days to appear in Rome and answer charges of heresy. Luther let the sixty days elapse; the Pope excommunicated him; Luther responded by publicly burning the papal order in the pit where one of Wittenberg’s hospitals burned its used rags. Reformers had been executed for less, but Luther was by now a very popular man throughout Europe. The authorities knew they would have serious trouble if they killed him, and the Church gave him one more chance to recant, at the upcoming diet—or congregation of officers, sacred and secular—in the cathedral city of Worms in 1521. He went, and declared that he could not retract any of the charges he had made against the Church, because the Church could not show him, in Scripture, that any of them were false:

Since then your serene majesties and your lordships seek a simple answer, I will give it in this manner, plain and unvarnished: Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the scriptures or clear reason, for I do not trust in the Pope or in the councils alone, since it is well known that they often err and contradict themselves, I am bound to the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not retract anything.

Link copied

The Pope often errs! Luther will decide what God wants! By consulting Scripture! No wonder that an institution wedded to the idea of its leader’s infallibility was profoundly shaken by this declaration. Once the Diet of Worms came to an end, Luther headed for home, but he was “kidnapped” on the way, by a posse of knights sent by his protector, Frederick the Wise. The knights spirited him off to the Wartburg, a secluded castle in Eisenach, in order to give the authorities time to cool off. Luther was annoyed by the delay, but he didn’t waste time. That’s when he translated the New Testament.

During his lifetime, Luther became probably the biggest celebrity in the German-speaking lands. When he travelled, people flocked to the high road to see his cart go by. This was due not just to his personal qualities and the importance of his cause but to timing. Luther was born only a few decades after the invention of printing, and though it took him a while to start writing, it was hard to stop him once he got going. Among the quincentennial books is an entire volume on his relationship to print, “ Brand Luther ” (Penguin), by the British historian Andrew Pettegree. Luther’s collected writings come to a hundred and twenty volumes. In the first half of the sixteenth century, a third of all books published in German were written by him.

By producing them, he didn’t just create the Reformation; he also created his country’s vernacular, as Dante is said to have done with Italian. The majority of his writings were in Early New High German, a form of the language that was starting to gel in southern Germany at that time. Under his influence, it did gel.

The crucial text is his Bible: the New Testament, translated from the original Greek and published in 1523, followed by the Old Testament, in 1534, translated from the Hebrew. Had he not created Protestantism, this book would be the culminating achievement of Luther’s life. It was not the first German translation of the Bible—indeed, it had eighteen predecessors—but it was unquestionably the most beautiful, graced with the same combination of exaltation and simplicity, but more so, as the King James Bible. (William Tyndale, whose English version of the Bible, for which he was executed, was more or less the basis of the King James, knew and admired Luther’s translation.) Luther very consciously sought a fresh, vigorous idiom. For his Bible’s vocabulary, he said, “we must ask the mother in the home, the children on the street,” and, like other writers with such aims—William Blake, for example—he ended up with something songlike. He loved alliteration—“ Der Herr ist mein Hirte ” (“The Lord is my shepherd”); “ Dein Stecken und Stab ” (“thy rod and thy staff”)—and he loved repetition and forceful rhythms. This made his texts easy and pleasing to read aloud, at home, to the children. The books also featured a hundred and twenty-eight woodcut illustrations, all by one artist from the Cranach workshop, known to us only as Master MS. There they were, all those wondrous things—the Garden of Eden, Abraham and Isaac, Jacob wrestling with the angel—which modern people are used to seeing images of and which Luther’s contemporaries were not. There were marginal glosses, as well as short prefaces for each book, which would have been useful for the children of the household and probably also for the family member reading to them.

These virtues, plus the fact that the Bible was probably, in many cases, the only book in the house, meant that it was widely used as a primer. More people learned to read, and the more they knew how to read the more they wanted to own this book, or give it to others. The three-thousand-copy first edition of the New Testament, though it was not cheap (it cost about as much as a calf), sold out immediately. As many as half a million Luther Bibles seem to have been printed by the mid-sixteenth century. In his discussions of sola scriptura , Luther had declared that all believers were priests: laypeople had as much right as the clergy to determine what Scripture meant. With his Bible, he gave German speakers the means to do so.

In honor of the five-hundredth anniversary, the excellent German art-book publisher Taschen has produced a facsimile with spectacular colored woodcuts. Pleasingly, the book historian Stephan Füssel, in the explanatory paperback that accompanies the two-volume facsimile, reports that in 2004, when a fire swept through the Duchess Anna Amalia Library, in Weimar, where this copy was housed, it was “rescued, undamaged, with not a second to lose, thanks to the courageous intervention of library director Dr. Michael Knoche.” I hope that Dr. Knoche himself ran out with the two volumes in his arms. I don’t know what the price of a calf is these days, but the price of this facsimile is sixty dollars. Anyone who wants to give himself a Luther quincentennial present should order it immediately. Master MS’s Garden of Eden is full of wonderful animals—a camel, a crocodile, a little toad—and in the towns everyone wears those black shoes like the ones in Brueghel paintings. The volumes lie flat on the table when you open them, and the letters are big and black and clear. Even if you don’t understand German, you can sort of read them.

Among the supposedly Biblical rules that Luther pointed out could not be found in the Bible was the requirement of priestly celibacy. Well before the Diet of Worms, Luther began advising priests to marry. He said that he would marry, too, if he did not expect, every day, to be executed for heresy. One wonders. But in 1525 he was called upon to help a group of twelve nuns who had just fled a Cistercian convent, an action that was related to his reforms. Part of his duty to these women, he felt, was to return them to their families or to find husbands for them. At the end, one was left, a twenty-six-year-old girl named Katharina von Bora, the daughter of a poor, albeit noble, country family. Luther didn’t want her, he said—he found her “proud”—but she wanted him. She was the one who proposed. And though, as he told a friend, he felt no “burning” for her, he formed with her a marriage that is probably the happiest story in any account of his life.

One crucial factor was her skill in household management. The Luthers lived in the so-called Black Monastery, which had been Wittenberg’s Augustinian monastery—that is, Luther’s old home as a friar—before the place emptied out as a result of the reformer’s actions. (One monk became a cobbler, another a baker, and so on.) It was a huge, filthy, comfortless place. Käthe, as Luther called her, made it livable, and not just for her immediate family. Between ten and twenty students lodged there, and the household took in many others as well: four children of Luther’s dead sister Margarete, plus four more orphaned children from both sides of the family, plus a large family fleeing the plague. A friend of the reformer, writing to an acquaintance journeying to Wittenberg, warned him on no account to stay with the Luthers if he valued peace and quiet. The refectory table seated between thirty-five and fifty, and Käthe, having acquired a large market garden and a considerable amount of livestock (pigs, goats), and now supervising a staff of up to ten employees (maids, a cook, a swineherd, et al.), fed them all. She also handled the family’s finances, and at times had to economize carefully. Luther would accept no money for his writings, on which he could have profited hugely, and he would not allow students to pay to attend his lectures, as was the custom.

Luther appreciated the sheer increase in his physical comfort. When he writes to a friend, soon after his marriage, of what it is like to lie in a dry bed after years of sleeping on a pile of damp, mildewed straw, and when, elsewhere, he speaks of the surprise of turning over in bed and seeing a pair of pigtails on the pillow next to his, your heart softens toward this dyspeptic man. More important, he began to take women seriously. He objects, in a lecture, to coitus interruptus, the most common form of birth control at the time, on the ground that it is frustrating for women. When he was away from home, he wrote Käthe affectionate letters, with such salutations as “Most holy Frau Doctor” and “To the hands and feet of my dear housewife.”

Among Käthe’s virtues was fertility. Every year or so for eight years, she produced a child—six in all, of whom four survived to adulthood—and Luther loved these children. He even allowed them to play in his study while he was working. Of five-year-old Hans, his firstborn, he wrote, “When I’m writing or doing something else, my Hans sings a little tune for me. If he becomes too noisy and I rebuke him for it, he continues to sing but does it more privately and with a certain awe and uneasiness.” That scene, which comes from “ Martin Luther: Rebel in an Age of Upheaval ” (Oxford), by the German historian Heinz Schilling, seems to me impossible to improve upon as a portrait of what it must have been like for Luther to have a little boy, and for a little boy to have Luther as a father. Luther was not a lenient parent—he used the whip when he felt he needed to, and poor Hans was sent to the university at the age of seven—but when, on his travels, the reformer passed through a town that was having a fair he liked to buy presents for the children. In 1536, when he went to the Diet of Augsburg, another important convocation, he kept a picture of his favorite child, Magdalene, on the wall of his chamber. Magdalene died at thirteen. Schilling again produces a telling scene. Magdalene is nearing the end; Luther is holding her. He says he knows she would like to stay with her father, but, he adds, “Are you also glad to go to your father in heaven?” She died in his arms. How touching that he could find this common-sense way to comfort her, and also that he seems to feel that Heaven is right above their heads, with one father holding out a hand to take to himself the other’s child.

One thing that Luther seems especially to have loved about his children was their corporeality—their fat, noisy little bodies. When Hans finally learned to bend his knees and relieve himself on the floor, Luther rejoiced, reporting to a friend that the child had “crapped in every corner of the room.” I wonder who cleaned that up—not Luther, I would guess—but it is hard not to feel some of his pleasure. Sixteenth-century Germans were not, in the main, dainty of thought or speech. A representative of the Vatican once claimed that Luther was conceived when the Devil raped his mother in an outhouse. That detail comes from Eric Metaxas’s book, which is full of vulgar stories, not that one has to look far for vulgar stories in Luther’s life. My favorite (reported in Erikson’s book) is a comment that Luther made at the dinner table while in the grip of a depression. “I am like a ripe shit,” he said, “and the world is a gigantic asshole. We will both probably let go of each other soon.” It takes you a minute to realize that Luther is saying that he feels he is dying. And then you want to congratulate him on the sheer zest, the proto-surrealist nuttiness, of his metaphor. He may feel as though he’s dying, but he’s having a good time feeling it.

The group on which Luther expended his most notorious denunciations was not the Roman Catholic clergy but the Jews. His sentiments were widely shared. In the words of Heinz Schilling, “Late medieval Christians generally hated and despised Jews.” But Luther despised them dementedly, ecstatically. In his 1543 treatise “On the Ineffable Name and the Generations of Christ,” he imagines the Devil stuffing the Jews’ orifices with filth: “He stuffs and squirts them so full, that it overflows and swims out of every place, pure Devil’s filth, yes, it tastes so good to their hearts, and they guzzle it like sows.” Witness the death of Judas Iscariot, he adds: “When Judas Schariot hanged himself, so that his guts ripped, and as happens to those who are hanged, his bladder burst, then the Jews had their golden cans and silver bowls ready, to catch the Judas piss . . . and afterwards together they ate the shit.” The Jews’ synagogues should be burned down, he wrote; their houses should be destroyed. He did not recommend that they be killed, but he did say that Christians had no moral responsibilities to them, which amounts to much the same thing.

This is hair-raising, but what makes Luther’s anti-Semitism most disturbing is not its extremity (which, by sounding so crazy, diminishes its power). It is the fact that the country of which he is a national hero did indeed, quite recently, exterminate six million Jews. Hence the formula “ From Luther to Hitler ,” popularized by William Montgomery McGovern’s 1941 book of that title—the notion that Luther laid the groundwork for the slaughter. Those who have wished to defend him have pointed out that his earlier writings, such as the 1523 pamphlet “That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew,” are much more conciliatory in tone. He seemed to regret that, as he put it, Christians had “dealt with the Jews as if they were dogs.” But making excuses for Luther on the basis of his earlier, more temperate writings does not really work. As scholars have been able to show, Luther was gentler early on because he was hoping to persuade the Jews to convert. When they failed to do so, he unleashed his full fury, more violent now because he believed that the comparative mildness of his earlier writings may have been partly responsible for their refusal.

Luther’s anti-Semitism would be a moral problem under any circumstances. People whom we admire often commit terrible sins, and we have no good way of explaining this to ourselves. But when one adds the historical factor—that, in Luther’s case, the judgment is being made five centuries after the event—we hit a brick wall. At the Nuremberg trials, in 1946, Julius Streicher, the founder and publisher of the Jew-baiting newspaper Der Stürmer , quoted Luther as the source of his beliefs and said that if he was going to be blamed Luther would have to be blamed as well. But, in the words of Thomas Kaufmann, a professor of church history at the University of Göttingen, “The Nuremberg judges sat in judgment over the mass murderers of the twentieth century, not over the delusions of a misguided sixteenth-century theology professor. . . . Another judge must judge Luther.” How fortunate to be able to believe that such a judge will come, and have an answer.

Luther lived to what, in the sixteenth century, was an old age, sixty-two, but the years were not kind to him. Actually, he lived most of his life in turmoil. When he was young, there were the Anfechtungen . Then, once he issued the theses and began his movement, he had to struggle not just with the right, the Roman Church, but with the left—the Schwärmer (fanatics), as he called them, the people who felt that he hadn’t gone far enough. He spent days and weeks in pamphlet wars over matters that, today, have to be patiently explained to us, they seem so remote. Did Communion involve transubstantiation, or was Jesus physically present from the start of the rite? Luther, a “Real Presence” man, said the latter. Should people be baptized soon after they are born, as Luther said, or when they are adults, as the Anabaptists claimed?

When Luther was young, he was good at friendship. He was frank and warm; he loved jokes; he wanted to have people and noise around him. (Hence the fifty-seat dinner table.) As he grew older, he changed. He found that he could easily discard friends, even old friends, even his once beloved confessor, Staupitz. People who had dealings with the movement found themselves going around him if they could, usually to his right-hand man, Philip Melanchthon. Always sharp-tongued, Luther now lost all restraint, writing in a treatise that Pope Paul III was a sodomite and a transvestite—no surprise, he added, when you considered that all popes, since the beginnings of the Church, were full of devils and vomited and farted and defecated devils. This starts to sound like his attacks on the Jews.

His health declined. He had dizzy spells, bleeding hemorrhoids, constipation, urine retention, gout, kidney stones. To balance his “humors,” the surgeon made a hole, or “fontanelle,” in a vein in his leg, and it was kept open. Whatever this did for his humors, it meant that he could no longer walk to the church or the university. He had to be taken in a cart. He suffered disabling depressions. “I have lost Christ completely,” he wrote to Melanchthon. From a man of his temperament and convictions, this is a terrible statement.

In early 1546, he had to go to the town of his birth, Eisleben, to settle a dispute. It was January, and the roads were bad. Tellingly, he took all three of his sons with him. He said the trip might be the death of him, and he was right. He died in mid-February. Appropriately, in view of his devotion to the scatological, his corpse was given an enema, in the hope that this would revive him. It didn’t. After sermons in Eisleben, the coffin was driven back to Wittenberg, with an honor guard of forty-five men on horseback. Bells tolled in every village along the way. Luther was buried in the Castle Church, on whose door he was said to have nailed his theses.

Although his resting place evokes his most momentous act, it also highlights the intensely local nature of the life he led. The transformations he set in motion were incidental to his struggles, which remained irreducibly personal. His goal was not to usher in modernity but simply to make religion religious again. Heinz Schilling writes, “Just when the lustre of religion threatened to be outdone by the atheistic and political brilliance of the secularized Renaissance papacy, the Wittenberg monk defined humankind’s relationship to God anew and gave back to religion its existential plausibility.” Lyndal Roper thinks much the same. She quotes Luther saying that the Church’s sacraments “are not fulfilled when they are taking place but when they are being believed.” All he asked for was sincerity, but this made a great difference. ♦

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Peter Schjeldahl

By James Wood

By Maya Jasanoff

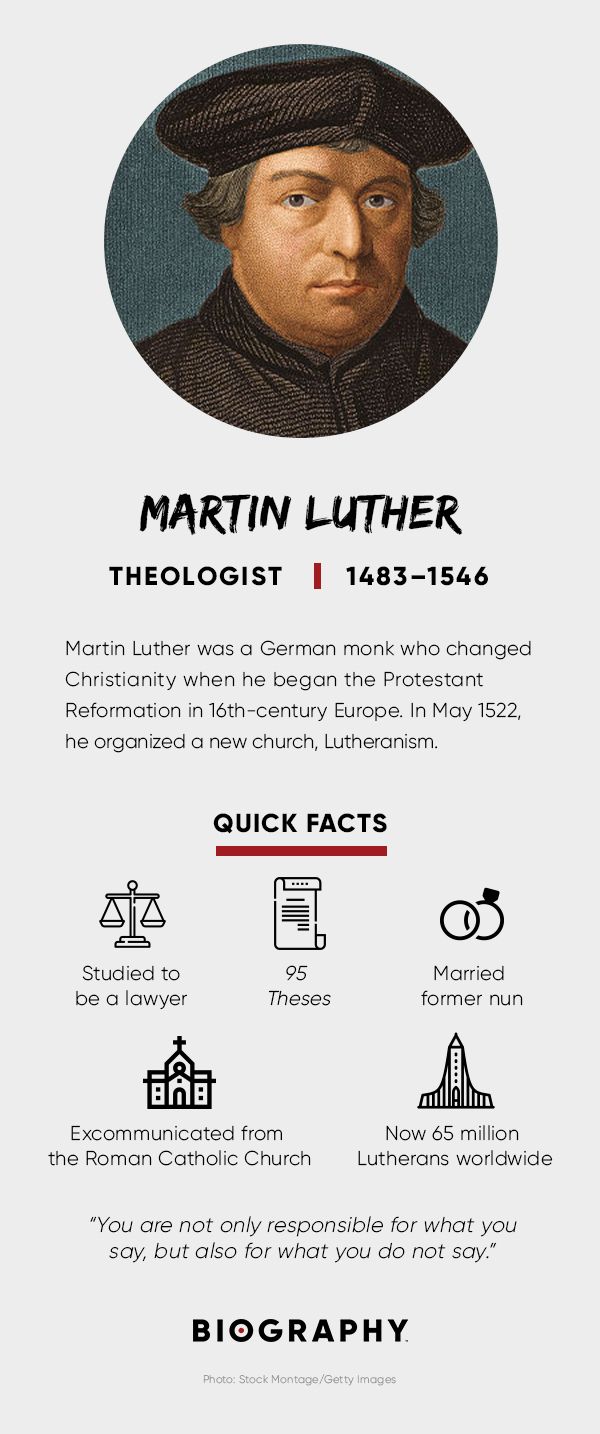

Martin Luther

(1483-1546)

Who Was Martin Luther?

Luther called into question some of the basic tenets of Roman Catholicism, and his followers soon split from the Roman Catholic Church to begin the Protestant tradition. His actions set in motion tremendous reform within the Church.

A prominent theologian, Luther’s desire for people to feel closer to God led him to translate the Bible into the language of the people, radically changing the relationship between church leaders and their followers.

Luther was born on November 10, 1483, in Eisleben, Saxony, located in modern-day Germany.

His parents, Hans and Margarette Luther, were of peasant lineage. However, Hans had some success as a miner and ore smelter, and in 1484 the family moved from Eisleben to nearby Mansfeld, where Hans held ore deposits.

Hans Luther knew that mining was a tough business and wanted his promising son to have a better career as a lawyer. At age seven, Luther entered school in Mansfeld.

At 14, Luther went north to Magdeburg, where he continued his studies. In 1498, he returned to Eisleben and enrolled in a school, studying grammar, rhetoric and logic. He later compared this experience to purgatory and hell.

In 1501, Luther entered the University of Erfurt , where he received a degree in grammar, logic, rhetoric and metaphysics. At this time, it seemed he was on his way to becoming a lawyer.

Becoming a Monk

In July 1505, Luther had a life-changing experience that set him on a new course to becoming a monk.

Caught in a horrific thunderstorm where he feared for his life, Luther cried out to St. Anne, the patron saint of miners, “Save me, St. Anne, and I’ll become a monk!” The storm subsided and he was saved.

Most historians believe this was not a spontaneous act, but an idea already formulated in Luther’s mind. The decision to become a monk was difficult and greatly disappointed his father, but he felt he must keep a promise.

Luther was also driven by fears of hell and God’s wrath, and felt that life in a monastery would help him find salvation.

The first few years of monastic life were difficult for Luther, as he did not find the religious enlightenment he was seeking. A mentor told him to focus his life exclusively on Jesus Christ and this would later provide him with the guidance he sought.

Disillusionment with Rome

At age 27, Luther was given the opportunity to be a delegate to a Catholic church conference in Rome. He came away more disillusioned, and very discouraged by the immorality and corruption he witnessed there among the Catholic priests.

Upon his return to Germany, he enrolled in the University of Wittenberg in an attempt to suppress his spiritual turmoil. He excelled in his studies and received a doctorate, becoming a professor of theology at the university (known today as Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg ).

Through his studies of scripture, Luther finally gained religious enlightenment. Beginning in 1513, while preparing lectures, Luther read the first line of Psalm 22, which Christ wailed in his cry for mercy on the cross, a cry similar to Luther’s own disillusionment with God and religion.

Two years later, while preparing a lecture on Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, he read, “The just will live by faith.” He dwelled on this statement for some time.

Finally, he realized the key to spiritual salvation was not to fear God or be enslaved by religious dogma but to believe that faith alone would bring salvation. This period marked a major change in his life and set in motion the Reformation.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S MARTIN LUTHER FACT CARD

'95 Theses'

On October 31, 1517, Luther, angry with Pope Leo X’s new round of indulgences to help build St. Peter’s Basilica , nailed a sheet of paper with his 95 Theses on the University of Wittenberg’s chapel door.

Though Luther intended these to be discussion points, the 95 Theses laid out a devastating critique of the indulgences - good works, which often involved monetary donations, that popes could grant to the people to cancel out penance for sins - as corrupting people’s faith.

Luther also sent a copy to Archbishop Albert Albrecht of Mainz, calling on him to end the sale of indulgences. Aided by the printing press , copies of the 95 Theses spread throughout Germany within two weeks and throughout Europe within two months.

The Church eventually moved to stop the act of defiance. In October 1518, at a meeting with Cardinal Thomas Cajetan in Augsburg, Luther was ordered to recant his 95 Theses by the authority of the pope.

Luther said he would not recant unless scripture proved him wrong. He went further, stating he didn’t consider that the papacy had the authority to interpret scripture. The meeting ended in a shouting match and initiated his ultimate excommunication from the Church.

Excommunication

Following the publication of his 95 Theses , Luther continued to lecture and write in Wittenberg. In June and July of 1519 Luther publicly declared that the Bible did not give the pope the exclusive right to interpret scripture, which was a direct attack on the authority of the papacy.

Finally, in 1520, the pope had had enough and on June 15 issued an ultimatum threatening Luther with excommunication.

On December 10, 1520, Luther publicly burned the letter. In January 1521, Luther was officially excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church.

Diet of Worms

In March 1521, Luther was summoned before the Diet of Worms , a general assembly of secular authorities. Again, Luther refused to recant his statements, demanding he be shown any scripture that would refute his position. There was none.

On May 8, 1521, the council released the Edict of Worms, banning Luther’s writings and declaring him a “convicted heretic.” This made him a condemned and wanted man. Friends helped him hide out at the Wartburg Castle.

While in seclusion, he translated the New Testament into the German language, to give ordinary people the opportunity to read God’s word.

Lutheran Church

Though still under threat of arrest, Luther returned to Wittenberg Castle Church, in Eisenach, in May 1522 to organize a new church, Lutheranism.

He gained many followers, and the Lutheran Church also received considerable support from German princes.

When a peasant revolt began in 1524, Luther denounced the peasants and sided with the rulers, whom he depended on to keep his church growing. Thousands of peasants were killed, but the Lutheran Church grew over the years.

Katharina von Bora

In 1525, Luther married Katharina von Bora, a former nun who had abandoned the convent and taken refuge in Wittenberg.

Born into a noble family that had fallen on hard times, at the age of five Katharina was sent to a convent. She and several other reform-minded nuns decided to escape the rigors of the cloistered life, and after smuggling out a letter pleading for help from the Lutherans, Luther organized a daring plot.

With the help of a fishmonger, Luther had the rebellious nuns hide in herring barrels that were secreted out of the convent after dark - an offense punishable by death. Luther ensured that all the women found employment or marriage prospects, except for the strong-willed Katharina, who refused all suitors except Luther himself.

The scandalous marriage of a disgraced monk to a disgraced nun may have somewhat tarnished the reform movement, but over the next several years, the couple prospered and had six children.

Katharina proved herself a more than a capable wife and ally, as she greatly increased their family's wealth by shrewdly investing in farms, orchards and a brewery. She also converted a former monastery into a dormitory and meeting center for Reformation activists.

Luther later said of his marriage, "I have made the angels laugh and the devils weep." Unusual for its time, Luther in his will entrusted Katharina as his sole inheritor and guardian of their children.

Anti-Semitism

From 1533 to his death in 1546, Luther served as the dean of theology at University of Wittenberg. During this time he suffered from many illnesses, including arthritis, heart problems and digestive disorders.

The physical pain and emotional strain of being a fugitive might have been reflected in his writings.

Some works contained strident and offensive language against several segments of society, particularly Jews and, to a lesser degree, Muslims. Luther's anti-Semitism is on full display in his treatise, The Jews and Their Lies .

Luther died following a stroke on February 18, 1546, at the age of 62 during a trip to his hometown of Eisleben. He was buried in All Saints' Church in Wittenberg, the city he had helped turn into an intellectual center.

Luther's teachings and translations radically changed Christian theology. Thanks in large part to the Gutenberg press, his influence continued to grow after his death, as his message spread across Europe and around the world.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Luther Martin

- Birth Year: 1483

- Birth date: November 10, 1483

- Birth City: Eisleben

- Birth Country: Germany

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Martin Luther was a German monk who forever changed Christianity when he nailed his '95 Theses' to a church door in 1517, sparking the Protestant Reformation.

- Christianity

- Astrological Sign: Scorpio

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Martin Luther studied to be a lawyer before deciding to become a monk.

- Luther refused to recant his '95 Theses' and was excommunicated from the Catholic Church.

- Luther married a former nun and they went on to have six children.

- Death Year: 1546

- Death date: February 18, 1546

- Death City: Eisleben

- Death Country: Germany

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Martin Luther Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/religious-figures/martin-luther

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: September 20, 2019

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- To be a Christian without prayer is no more possible than to be alive without breathing.

- God writes the Gospel not in the Bible alone, but also on trees, and in the flowers and clouds and stars.

- Let the wife make the husband glad to come home, and let him make her sorry to see him leave.

- You are not only responsible for what you say, but also for what you do not say.

Famous Religious Figures

7 Little-Known Facts About Saint Patrick

Saint Nicholas

Jerry Falwell

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh

Saint Thomas Aquinas

History of the Dalai Lama's Biggest Controversies

Saint Patrick

Pope Benedict XVI

John Calvin

Pontius Pilate

Premium Content

- HISTORY & CULTURE

How Martin Luther Started a Religious Revolution

Five hundred years ago, a humble German friar challenged the Catholic church, sparked the Reformation, and plunged Europe into centuries of religious strife.

Some say that the beginnings of the Reformation can be traced back to a thunderstorm in 1505. After surviving the tempest, a promising law student at the University of Erfurt in Germany changed the course of his life. The young scholar’s name was Martin Luther, and the foul weather set him on a collision course with Rome and would trigger a crisis of faith in Western Christianity.

“Portrait of Martin Luther as a Young Man” by Lucas Cranach the Elder depicts the Protestant founder as a simple, sincere monk.

Luther came from a well-heeled family in the central region of Saxony. Luther was born in Eisleben in November 1483. Shortly after his birth, the family moved about 10 miles away to the town of Mansfeld. A successful businessman in copper mining and refining, his father, Hans, had young Martin educated at a local Latin school and later at schools in Magdeburg and Eisenach. In 1501, at age 19, he enrolled in the University of Erfurt to continue his studies.

In 1505 he was returning to Erfurt after visiting his parents when a violent thunderstorm arose with raging winds and driving rain. “[I was] besieged by the terror and agony of sudden death,” the young Luther later recalled. In his panic he made a terror-stricken vow to St. Anne. He would join a religious order, he promised, if only she would save his life.

Biographies of the founder of the Protestant Reformation point out that a deep sense of religious turmoil probably shaped Luther’s thoughts long before the storm. Even so, following his safe deliverance from the tempest, Luther kept his promise and, to the dismay of his father, abandoned his legal education to join the strictly observant Augustinian monastery in Erfurt. It was a decisive, stubborn act, mixed with a deep sense of religious vocation—an attitude he would display for the rest of his remarkable and turbulent life.

The engraving above shows Martin Luther writing his protest on the door of Wittenberg’s All Saints’ Church. It is from a 1518 German broadside marking the first anniversary of the Ninety-Five Theses. By then, the image of Luther publicly attacking papal corruption had become a potent 16th-century meme.

A Rising Storm

During his first years at the monastery, Luther did not seem to be especially subversive. He quickly made a name for himself not only with his brilliance as a theologian but also with his meticulous observance of the harsh rules governing life in the monastery; he fasted, prayed, and confessed. Content with just a table and chair in his unheated room, he would rise in the early morning hours to pray matins and lauds. By the fall of 1506 he had gained full admission to the order.

Luther continued his theological education after becoming a monk. In 1507 he was ordained by the Bishop of Brandenburg. In 1508 he taught theology at the newly founded University of Wittenberg, where he also received two bachelor degrees.

For Hungry Minds

In 1510 Luther’s studies were interrupted by a political crisis that engulfed the Augustinians. The current pope, Julius II, had decided to merge two opposed branches (the observant and nonobservant) of the order, a plan that horrified Luther’s strictly observant monastery. Luther was chosen by his superiors to defend the views of their monastery before the general Augustinian council in Rome.

In late 1510 Luther made his first—and last—visit to Rome. During his stay, the friar followed traditional pilgrimage customs. Among other observances, he climbed the steps of the St. John Lateran Basilica on his knees, reciting the Lord’s Prayer on each step. It is said that during his ascent he was perplexed to find the words of the Apostle Paul coming back to him: “the righteous shall live by faith,” a tenet that would form a central part of his later doctrine. During his stay, Luther found himself unsettled by the corruption and lack of spirituality he saw in Rome. He saw openly corrupt priests who sneered at the rituals of their faith. He later described his visit: “Rome is a harlot . . . The Italians mocked us for being pious monks, for they hold Christians fools. They say six or seven masses in the time it takes me to say one, for they take money for it and I do not.”

After returning to Germany, Luther earned his doctorate in 1512. As a professor, he taught several classes at the University of Wittenberg. The spiritual hollowness he had seen in Rome did not break his faith with the church, but scholars believe it continued to disquiet him.

Nailing a Myth

That Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses helped launch the Reformation is beyond question. Dated October 31, 1517, Luther’s letter to his superiors did include copies of the theses. But did he actually nail them to the door of Wittenberg’s All Saints’ Church? The historical consensus is . . . probably not. Luther himself never mentioned having done so. At the time, he had no idea his theses would create such a stir and would not have seen the need to carry out such a provocative act. Nevertheless, the legend arose and gained traction.

Luther Enters the Fray

The spark that ignited Luther’s confrontation with Rome was the sale of “indulgences,” which would lessen the impact of, or pardon, a person from their sins. In theory, indulgences were granted by the church on the condition that the recipient carried out some kind of good work or other specified acts of contrition. In practice, indulgences could be bought. The practice was abused by the church, which began relying upon their sale as a way of raising money, especially to pay for costly building projects.

Cameo of Leo X, pope at the time of Luther’s 1517 revolt.

Rome in the early 1500s was under the spell of the artistic projects of the Renaissance. Around 1515, Pope Leo X published a new indulgence in a bid to fund the reconstruction of the Basilica of St. Peter in Rome, entrusting Albert of Brandenburg, the Archbishop of Mainz, with promoting its sale in Germany.

Enraged, Luther took a stand against the papal actions. On October 31, 1517, he composed his Disputation on the Power of Indulgences , better known as the Ninety-Five Theses. According to tradition, he nailed these to the door of All Saints’ Church, Wittenberg, although modern historians are somewhat skeptical that such a lengthy document could be posted in this way. Regardless of how the Ninety-Five Theses were distributed, many found Luther’s arguments explosive. He argued that the practice of relying on indulgences drew believers away from the one true source of salvation: faith in Christ. God alone had the power to pardon the repentant faithful. The pontifical council ordered him to retract his claims immediately, but Luther refused.

An Elector for an Enclave

Luther’s reformation was not born in a vacuum, and his fate rested as much on the turbulent politics of the day as it did on pure questions of theology. Wittenberg was part of Saxony, a state of the Holy Roman Empire, a patchwork of territories in central Europe with roots deep in the medieval past. The Holy Roman Emperor was appointed by the heads of its main states, influential rulers known as electors.

At the time that Luther wrote his theses, the elector of Saxony was Frederick the Wise. A humanist and a scholar, Frederick had founded the new university at Wittenberg that Luther attended. Frederick’s response to Luther’s theological challenge was complex. He never stopped being a Catholic, but he decided from the outset to protect the rebel friar both from the fury of the church and the Holy Roman Emperor. When in 1518 Luther was summoned to Rome, Frederick intervened on his behalf, ensuring that he would be questioned in Germany, a much safer place for him than Rome. The church was forced to respect Elector Frederick’s wishes because he would be instrumental in choosing the replacement to the ailing Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I.

Letters of indulgence, like this one granted in 1512, sparked Luther’s revolt in 1517.

Safe under the wing of Frederick, Luther began to engage in regular public debate on religious reforms. He broadened his arguments, declaring that any church council or even a single believer had the right to challenge the pope, so long as they based their arguments on the Bible. He even dared to argue that the church did not rest on papal foundations but rather on faith in Christ.

Luther must have realized early on that his reform movement had a political dimension. In 1520 he wrote a treatise, “Address to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation.” It argued that all Christians could be priests from the moment of their baptism, that anyone reading the Scripture with faith had the right to interpret it, and that every believer had the right to assemble a free council. This declaration was revolutionary for the ecclesiastic hierarchy of the time.

Heretics and Heroes

This 15th-century print by Diebold Schilling the Elder depicts the burning of Czech reformist Jan Hus in 1415.

Luther was not the first person to confront the Catholic Church. Writing in the 1370s and ‘80s, Oxford scholar John Wycliffe denounced the wealth of the church, called for a greater emphasis on scripture, and oversaw an English biblical translation. The church condemned Wycliffe, but Oxford University shielded him from arrest. In the 1400s Jan Hus, a scholar at the University of Prague, was exposed to Wycliffe’s works. Hus too believed that scripture was greater than tradition and preached in his native language, Czech. His writings led him to leave Prague for fear of reprisals, but Hus was later arrested in 1414, charged with heresy, and burned at the stake in 1415. Following his death, his followers continued the fight, forming the Hussite movement which spread through what is today the Czech Republic.

Luther in Peril

In January 1521 a papal decree was published under which Luther was declared a heretic and excommunicated . Under normal circumstances, this sentence would have meant a trial and, most likely, execution. But these were no ordinary times. Both Frederick and widespread German public opinion demanded that Luther be given a proper hearing. The newly elected Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, finally acquiesced and called Luther to come before the Imperial Diet (assembly) to be held that spring in the ancient Rhineland city of Worms.

You May Also Like

How did Jesus' parents become a couple? Here’s what biblical scholars say.

How did Jesus' final days unfold? Scholars are still debating

Who was Guy Fawkes, the man behind the mask?

On his journey to Worms Luther was acclaimed almost as a messiah by the citizens of the towns he passed through. On his arrival in Worms in April 1521, crowds gathered to see the man who embodied the struggle against the seemingly all-powerful Catholic Church. Once inside the episcopal palace, Luther was met by young Charles V, princes, imperial electors, and other dignitaries. When charged, Luther said that he stood by every one of his published claims.

The Archbishop of Trier urged him to retract his theses, and Luther asked for time for consideration. After a night of reflection, he remained steadfast. His writings, he maintained, were based on Scripture; on his conscience, he declared he could not recant anything “for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe.” He is said to have concluded with the famous words in German: “ Hier stehe ich, ich kann nicht anders —Here I stand, I can do no other.”

Fighting for Faith

Luther’s revolt inspired other religious leaders in cities outside Germany such as Strasbourg, Geneva, Basel, and Lucca. In Zürich Huldrych Zwingli, a Swiss leader of the Reformation, persuaded the city council and a large part of the population to accept a full program for the strict observance of the Gospel. Priestly celibacy was abolished. Baptism and the Eucharist were still celebrated as sacraments, but the belief that during the Mass the bread and wine actually turned into the body and blood of Christ was abandoned. In Zwingli’s view, the Eucharist became a symbolic rite in remembrance of Christ’s sacrifice. Sacred music was prohibited, and paintings in churches were destroyed. An army of preachers was chosen to go out into the city and foment this radical new teaching.

The Revolution Spreads

Luther left Worms unbowed, but his life was in peril. Charles V signed an edict naming him and his followers political outlaws and demanded their writings be burned. Seized by his protector, Frederick, Luther was granted sanctuary in the castle of Wartburg until the situation evolved and the danger passed.

Outlawed for having defended his ideas at the Diet of Worms in 1521, Luther took refuge here in Wartburg Castle, under the protection of Frederick the Wise of Saxony. In this medieval fortress, Luther made his translation of the New Testament into German.

Despite his absence, Luther’s words and writings were spreading like wildfire throughout Germany, thanks in part to the printing revolution. Luther’s declarations at Worms sparked a revolutionary spirit that had been smoldering among the German people, many of who were tired of seeing their earnings gobbled up by the church. Supported by their rulers, also eyeing the opportunity of greater freedom from Rome, a host of reformers came forward in support of Lutheran principles.

Some, to Luther’s dismay, went very much further. Just after Christmas, in 1521, the so-called Zwickau prophets foretold the imminent return of Christ. They wanted to tear down and destroy all religious images, statues, and altarpieces. They even proposed radical changes to the sacraments, the most dramatic of which was their rejection of the rite of baptism for children and a demand that adults be rebaptized. It was from this element that Anabaptism—from the Latin anabaptista , meaning “one who baptizes over again”—grew. Despite savage repression, Anabaptism periodically flared up during the following years.

Another serious threat to the established order was the struggle unleashed by the peasants in 1524 and 1525. The ideas of equality and social justice inherent in Luther’s reform were seized upon by a rural society hungry for change. A revolt erupted across huge swaths of Germany.

Luther may have been a theological radical, but he was not a social reformer. On hearing news of these movements, he voiced his opposition. Having left Wartburg Castle in 1522, he upbraided all Christians who were taking part in insurrections against authority. In an essay entitled “Against the Murderous and Robbing Hordes of the Peasants” (1525), he condemned the peasant violence as work of the devil. He called out for the nobility to track down the rebels like they would rabid dogs as, “nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful and devilish than a rebel.” Without Luther’s backing, the radical revolution was dealt a death blow. In May 1525 the peasants were defeated in Frankenhausen, and their leader was executed.

Rebuilt in the early 1500s on the site of an earlier church, All Saints Church in Wittenberg, Germany, is where Martin Luther was laid to rest in 1546.

An Unstoppable Force

When the Holy Roman Empire attempted to harden its line against Lutheranism and the wider reform movement at the Diet of Speyer in 1529, the pro-reform German princes dissented, or “protested.” Luther spent the rest of his life consolidating this new “Protestant” movement, whose tenets were spreading across Europe to Strasbourg, Zürich, Geneva, and Basel.

Luther’s efforts created a great rift in Western Christianity and dominated European politics for several centuries as western Europe split into a largely Catholic south and a Protestant north. France straddled the fault line, and for much of the later 16th century was engulfed by religious conflict. The Lutheran doctrine, combined with Tudor power politics, led to England’s ultimate break from Rome in 1534. Years of Catholic-Protestant tensions in England prompted the Pilgrims to embark for the New World in the Mayflower, and laid the foundations for the English Civil War—events that stemmed from the actions of an obscure monk, on an October day exactly five hundred years ago.

Historian and author Josep Palau Orta is a specialist in religion in 16th-century Europe.

Related Topics

- HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION

- CATHOLICISM

- CHRISTIANITY

- PEOPLE AND CULTURE

A royal obsession with black magic started Europe's most brutal witch hunts

From allies to enemies: Queen Elizabeth and King Philip

%20-%20Saint%20Romain_4x3.jpg)

A road trip in Burgundy reveals far more than fine wine

See how stonemasons keep England’s oldest cathedrals standing tall

It took a village to build Europe’s Gothic cathedrals

- Paid Content

- Environment

- Photography

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

October 31, 1517: Luther’s 95 Theses Appear

Martin Luther nailing the 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg is one of the iconic images of the Reformation. In this essay, historians Volker Leppin and Timothy Wengert examine the best evidence for and against this famous story. In either case, it is correct to say that Luther posted the 95 Theses on October 31, 2017: that is the date listed on the cover letter that he mailed—posted—to local German bishops.

Essay: “Sources for and Against the Posting of the Ninety-Five Theses” by Volker Leppin and Timothy Wengert, LQ 29 (2015), 373-398. All essays linked in this timeline are offered solely for personal and educational usage.

Image: Text of 95 Theses

Video: Timothy Wengert, “The Reformation: 500 Years Later"

August 29, 1518: Philip Melanchthon Arrives in Wittenberg

Philip Melanchthon’s addition to the University of Wittenberg in 1518 marked the beginning of Reformation partnership that lasted for more than a quarter of a century. In this reflection on his career, Heinz Scheible introduces readers to Melanchthon and corrects many of the misunderstandings that surround Luther’s longtime colleague and the Praeceptor Germaniae (teacher of Germany).

Essay: “Luther and Melanchthon” by Heinz Scheible, LQ 4 (1990), 317-339.

Image: Colored woodcut of Philip Melanchthon (dated 1577) included into a German version of Melanchthon’s 1536 Loci Communes, rare book collection of Wartburg Theological Seminary. Photo by Martin Lohrmann, used with permission.

June 13, 1525: War and Marriage

Amid the tumult of the Peasants War of 1524/25, Martin Luther married Katharina von Bora in a private ceremony in June 1525, a marriage which he viewed as an affirmation of life amid perilous times. Martin and Katie were married over twenty years, until the reformer’s death in 1546. Their relationship was characterized by mutual love and respect. In this essay, Martin Treu describes Katharina’s many major contributions to the Reformation.

Essay: “Katharina von Bora: The Woman at Luther’s Side” by Martin Treu, LQ 13 (1999), 156-178.

Image: “Kattarina Lutterin” by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1526

June 25, 1530: Presentation of Augsburg Confession

Holy Roman Emperor Charles V invited his protesting subjects to defend their faith at the 1530 imperial meeting in Augsburg. Composed primarily by Philip Melanchthon, the Augsburg Confession remains foundational for the preaching and teaching of Lutheran churches around the world today. Author Eric Gritsch (d. 2012) was a longtime professor of church history at Gettysburg Seminary and a noted ecumenical theologian.

Essay: “Reflections on Melanchthon as Theologian of the Augsburg Confession” by Eric Gritsch, LQ 12 (1998), 445-452.

Image: The Diet of Augsburg

September 1534: Publication of the German Bible

In a project that began with Luther’s translation of the New Testament (1522), the entire German Bible was published in September 1534. Though it often carries the name “the Luther Bible,” this translation was the work of a team whose members included Luther, Melanchthon, Caspar Cruciger, Johannes Bugenhagen, Justus Jonas, Matthäus Aurogallus, and Georg Rörer. Here Birgit Stolt studies Luther’s great ability to communicate both meaning and feeling.

Essay: “Luther’s Translation of the Bible” by Birgit Stolt, LQ 28 (2014), 373-400.

Image: Title page to 1541 edition of the German Bible

February 18, 1546: Death of Martin Luther