Get the Reddit app

This subreddit is for discussing academic life, and for asking questions directed towards people involved in academia, (both science and humanities).

Taking a leave of absence from the PhD due to mental illness

I'm in my second-year of a humanities PhD at a top-ranked university in Canada. I've struggled with mental illness throughout my entire life (diagnosed bipolar disorder) and feel as if my health has just gotten worse during this program and especially during the pandemic. I've dealt with these issues before, including having had to take a few months off during my undergraduate studies after being hospitalized. I really thrived during the MA, but I think that was in part because less was expected of me than during the PhD and there was a clear end in sight (my MA program was only 12 months whereas average time to completion of my PhD program is over 7 years and often goes beyond the guaranteed funding period).

Over the past year and a half, I've noticed I've been ignoring my mental well-being in order to keep up with constant deadlines, research, writing, TAing and RAing duties, administrative responsibilities, etc., that I am just burning out and am not sure if finishing this program is even worth it (especially considering I've been doubting recently if I want to be in academia). I think it might be in my best interest to take a leave of absence for a semester or two in order to get my shit together. I've already finished coursework and would take time off after I complete my qualifying field exams in the summer. I would be ABD at this point.

TL;DR: Basically, I was wondering if there were those out there who took a LOA (especially because of mental illness) and what you did during your time off, and ultimately why or why didn't you decide to return to the PhD program?

Thanks for visiting! GoodRx is not available outside of the United States. If you are trying to access this site from the United States and believe you have received this message in error, please reach out to [email protected] and let us know.

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

How to take a mental health related leave of absence (immediately before quals) without revealing mental illness to advisor

Recently due to burn out, my physical and mental health have been deteriorating to the point where I believe I need several months of leave to recover before I can be at a point where I can function normally again. I have been seeing a counsellor. However, now is a particularly 'bad' time to take leave because my PhD qualifying exams (first attempt) is very soon and in the month following, I have conferences/academic travels planned (which are great opportunities for furthering my career that my advisor has offered to me instead of to other students). Any one of these is enough exertion that I serious doubts that my physical and mental health will be recoverable afterwards, which makes me determined to take leave now, before it is too late. However, I am aware that having both these plans disrupted with short notice will not make my advisor or my department happy. Furthermore, while my relationship with my advisor is currently fine, it is not close enough that I feel comfortable confiding in him that I have a mental illness. His personality traits make me suspect that he might either not be particularly sympathetic/understanding, or he will be too afraid to 'break' me in the future. Therefore, I would prefer that the department and my advisor do not know that this leave of absence is due to mental health.

However, I need a compelling reason for the leave to be approved at this point in my studies and to have my qualifiers shifted to an unorthodox later date. My family are supportive of my decision for taking leave and have offered to invent some sort of family emergency which I can use as an excuse. However, my family are overseas, which is a fact known to both my advisor and my department (I am one of very few international students), yet I hope to be able to stay here during leave, where I have the support of both my husband and counsellor. We live close to campus and the counsellor is on campus in a small campus. So I am afraid that if I lie that I need to leave immediately for a family emergency, that during the time of my leave, my advisor/department secretary/chair will see me walking around campus and this might cause problems.

Are there any potential valid justifications for a leave of absence which do not mean that I have to mention mental illness, or leave the country? I will also be discussing this with my counsellor, but perhaps someone here has a clever idea that I have completely missed. Also it would be helpful for me if people can provide me with context/comparisons for just how bad/uncommon it would be to 1) take a leave of absence shortly before a qualifying exam (from the view of the department and advisor) and 2) take a leave of absence that disrupts travel plans where so far no money has been spent (from the view of the advisor), so that I can have some expectation of the resistance I might encounter.

- 6 I would not condone lying in this situation, talk to your advisor. – Solar Mike Apr 25, 2019 at 12:09

- This would honestly be one of the first lies I have ever told. I would also prefer to avoid lying, but questions like academia.stackexchange.com/questions/97439/… and academia.stackexchange.com/questions/77908/… and a suspicion he might ask me to just get over the next few months (and judge me harshly if I do not) make me very reluctant to be honest with him. – user108113 Apr 25, 2019 at 12:34

- 1 I have seen many students start with a lie and watch it unravel... Really causes more grief than you think it solves. – Solar Mike Apr 25, 2019 at 12:35

- 1 An on-campus counsellor should know the procedures for taking a leave of absence. If you have not done so already, I suggest getting their advice on this. They know more than any of us can about your university's policies and procedures, and your mental state. – Patricia Shanahan Apr 25, 2019 at 13:37

- Will you have visa issues as an international student if you try to stay in country while on leave from college? If you are not sure, discuss this on expatriates . You can just say you need the leave for medical reasons. – Patricia Shanahan Apr 25, 2019 at 13:40

Have you considered asking for leave due to "urgent health-related issues" without providing more detail than you feel comfortable providing? There is no need to explain exactly what issues you are dealing with at the moment. It is perfectly sufficient to state convincingly -- perhaps with supporting documents from a medical doctor or other health professional -- that the issue is urgent and requires that you take leave as soon as possible. How you phrase this is something to discuss with your counselor.

Personally, I don't think it's reasonable, when your mental health is at stake, to agonize over what your adviser might or might not think of you. Chances are they will be understanding and appreciate that you come to them now and not later, when your health has deteriorated further and more work has piled up. By contrast, if your adviser turns out to be unsupportive or worse, it's time for you to look for someone else to work with! Also this is worth finding out sooner rather than later, so you may see this request as a litmus test of your adviser's qualities.

As another aside, brooding over other people's impression of you is a habit that isn't conducive to mental well-being. I suggest talking this over with your counselor as well, and finding a way to assert your needs and boundaries with confidence. It will come in handy later in your (academic) career.

- +1. It´s a urgent health issue, period. Details are non of anyone´s business. – asquared Apr 25, 2019 at 13:38

- Thank you for your answer. The form for applying for a leave of absence differentiates between medical issues and psychological ones, so I would need to be specific. But yes, I could still go with the 'urgent mental health issue' line. – user108113 Apr 25, 2019 at 13:44

- And since you have physical health issues, you could just mention those if you wanted to. But that's entirely your choice. – jaia Apr 27, 2019 at 0:55

You must log in to answer this question.

Hot network questions.

- Effects if a human was shot by a femtosecond laser

- Can we find the equivalent resistance just by using series and parallel combinations?

- Why do airplanes sometimes turn more than 180 degrees after takeoff?

- Isomorphism of topological groups

- are "I will check your homework later" and "I will check on your homework later" similar?

- How to use cp's --update=none-fail option

- How much extra did a color RF modulator cost?

- Test for multicollinearity with binary and continuous independent variables

- Do you have an expression saying "when you are very hungry, bread is also delicious for you" or similar one?

- Can LLMs have intention?

- Who are the mathematicians interested in the history of mathematics?

- Why does the proposed Lunar Crater Radio Telescope suggest an optimal latitude of 20 degrees North?

- Is it legal to deposit a check that says pay to the order of cash

- How might a physicist define 'mind' using concepts of physics?

- Find the most isolated point

- unable to ping my router from outside

- Calculating Living Area on a Concentric Shellworld

- What is the U.N. list of shame and how does it affect Israel which was recently added?

- How to justify formula for area of triangle (or parallelogram)

- incorrect signature: void getDescribe() from the type Schema.DescribeFieldResult

- What’s the history behind Rogue’s ability to touch others directly without harmful effects in the comics?

- Transformer with same size symbol meaning

- LilyPond: tuplet bars don't seem to match time used

- Prove that "max independent set is larger than max clique" is NP-Hard

/images/cornell/logo35pt_cornell_white.svg" alt="mental health leave phd"> Cornell University --> Graduate School

Health leave.

Cornell recognizes that medical and mental health conditions can interfere with a student’s ability to be academically successful. Taking a health leave of absence (HLOA) provides students with a break from their studies to attend to treatment or management of a health condition. Any Cornell student can request to take an HLOA. The university’s goal is to enable students to address their health needs and return to complete their academic program.

In essence, a health leave of absence is a voluntary separation from the university for health reasons and allows the student to “stop the clock” on academic responsibilities while prioritizing health needs.

In some cases, reasonable accommodations may enable a student to complete academic coursework and remain on campus rather than taking an HLOA. A physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities is considered a disability and may warrant accommodations. A person who has a history of such an impairment or who is perceived by others as having such an impairment may also be eligible for accommodations (ADA). All students who are considering an HLOA are encouraged to consult with Student Disability Services to discuss eligibility for accommodations before requesting an HLOA.

Only the student can initiate the voluntary process. Graduate and professional students should be informed of the health leave of absence status, especially if health is negatively impacting academic performance.

Details about the health leave of absence process are available .

Any student who may be interested in initiating a health leave of absence should seek guidance from their health care provider, the Health Leaves Coordinator ( [email protected] ), or the Graduate School to help determine when this course of action is appropriate. Some common signs that a health leave might be beneficial include:

- Your medical condition has made it difficult for you to focus or concentrate.

- Your medical condition has left you lacking the motivation needed to successfully pursue graduate studies.

- Your medical condition has made it difficult to complete your academic or research requirements.

Often graduate and professional students will take a health leave of absence when:

- The individual students believe this is the best course of action for them.

- There has been a medical assessment from a provider who has recommended that the student take a break from their academic pursuits.

- Before the quality of their academic responsibilities suffer and becomes noticeable by the faculty. Typically, faculty members are very helpful and supportive when health is a concern; however, there can be limits to how long they are able to be supportive if your lack of academic progress due to health issues continues for an extended period of time. Aim to time a health leave to occur when you, your Special Committee Chair, and your DGS are in productive communications about your future academic plans.

Length of leave

The duration of the leave will depend upon the time you need for treatment and/or recovery, along with the resolution of any academic conditions determined by your graduate program.

The Graduate School allows health leave of absence status at increments of 12 months with a possible annual renewal for up to four years total. Depending on your academic program will determine the flexibility of when you will be able to return. You may not return from a leave within the semester that the leave was taken and you must return at the start of the Fall, Spring or Summer semesters.

For F-1 and J-1 International Students – Please note that if you choose to remain in the U.S. during your leave, you will need to maintain your student visa status. A reduced course load (i.e. health leave) is permitted for up to 12 months. For each semester of medical leave, you must provide medical documentation from a licensed medical doctor, doctor of osteopathy, or licensed clinical psychologist to substantiate the illness or medical condition. Please consult with the Office of Global Learning if you have more questions about the impact health leave of absence will have on your immigration status.

Time to degree

Time away does not count toward time to degree.

Financial support

Financial support is not available to a student on a health leave. By policy, “Students returning from approved health leave of absence within the four-year window are guaranteed any financial support remaining from their original offer of admission modified by any written changes to the financial commitment made prior to the health leave of absence, although the specific duties associated with that support may be adjusted and the return shall be timed to coincide with normal funding cycles.” Note: For U.S. citizens with educational loans, the repayment grace period starts the date the loans become active.

Cornell access

While you are on an HLOA, you will not be a registered student. This will have an impact on your access to university services, but there are some resources, particularly on the Ithaca campus, that students on HLOA can continue to use.

In brief, if you are on a health leave, you will no longer have access to campus facilities and services that you would normally access with your NetID. However, your Cornell email will remain for the duration of your health leave of absence. You may request library privileges with support from your academic advisor and director of graduate studies, and pay any applicable fees.

Health insurance

Review your health insurance coverage to find out how it might be impacted by an HLOA.

- Students who take HLOA mid-plan year may retain their Student Health Plan (SHP) coverage through the end of the plan year (through June 30). Visit the Student Health Benefits website or contact the Office of Student Health Benefits at [email protected] for detailed guidance about options for extending coverage.

- If you have another health insurance plan, contact the plan provider to clarify coverage using the phone number on your insurance card. In some cases, you may need to apply for continuation of coverage.

Access at Cornell Health

Students who are on a health leave of absence are not eligible to use Cornell Health services (including both medical and mental health services), except for pharmacy. If you elect to go on a health leave of absence, Cornell Health will be able to aid in transferring care from Cornell Health to other providers in the community and beyond. This is true for all students on a health leave regardless of individual health insurance plan.

International students

Taking a leave of absence may have implications for an international student’s visa status. If you are on an F-1 or J-1 student visa, you will need written documentation from a health care provider recommending a leave of absence or reduced course load for medical or mental health reasons. Immigration rules for a health leave of absence or reduced course load may not coincide with Cornell’s health leave requirements and limitations. Please contact the Office of Global Learning to discuss the impact of an HLOA on your visa status.

Academic plan

An important part of the process in taking a health leave of absence is that each graduate and professional degree student will receive an academic plan that is expected to be completed prior to returning to registered student status. The purpose of the academic plan is to:

- Determine if you have any outstanding academic work that should be addressed prior to returning from a health leave. It is not meant to be punitive or represent additional work, but instead should address delays or poor academic performance to any academic milestones that likely could not be addressed due to your health while here. Examples include incomplete coursework, drafts of outstanding papers, etc.

- Reiterate any future academic expectations to allow you to fully understand what would be expected upon return. Examples include timing of exams, additional required coursework, etc.

- Any specific needs that supports a smooth transition back into the program. Examples include informing program with plans to return (i.e. needing x months of lead time to secure funding), when a student can return (i.e. only x semester because of course sequencing), etc.

The plan may state that there is nothing academically for you to do during a health leave of absence but take care of health.

Initiating the health leave of absence process

The complete steps to initiate the process are outlined on the Student Disability Services (SDS) Health Leave of Absence webpage .

If you don’t know where to start or whom to contact, please email the Health Leaves Coordinator at [email protected] , who will work with you to facilitate consultations between you, your health care provider, SDS, and your college/school before granting a health leave of absence. If you would like to discuss your situation confidentially and evaluate all options in managing health with your academics and are not sure where to start, please contact Janna Lamey ( [email protected] ).

Return from the health leave of absence

When you are ready to return from an HLOA, you will need to complete a series of administrative processes that is outlined on the SDS HLOA webpage . You will need to make the request through the Health Leaves Coordinator, submit documentations that indicates your fitness to resume your education at Cornell, confirmation that your academic plan has been successfully completed, and consult with the Health Leaves Coordinator, SDS, Graduate School, and a health care provider. While requests to return from a health leave of absence will be accepted on a rolling basis to offer flexibility and accommodate each student’s individual health situation and academic program, please note the deadlines outlined.

Learn more about health leaves

- Read Student Disability Services Health Leave of Absence page

- Read University Policy 7.1 on voluntary leaves of absence for students

- Contact Cornell Health Leaves Coordinator ( [email protected] )

- Contact Janna Lamey ( [email protected] ), associate dean for graduate student life

See the complete FAQ .

- Graduate and Professional Student Parental Accommodation, Policy 1.6

- Graduate Student Assistantships, Policy 1.3

- Cornell Student Disability Services Office

Janna Lamey Associate Dean for Graduate Student Life [email protected]

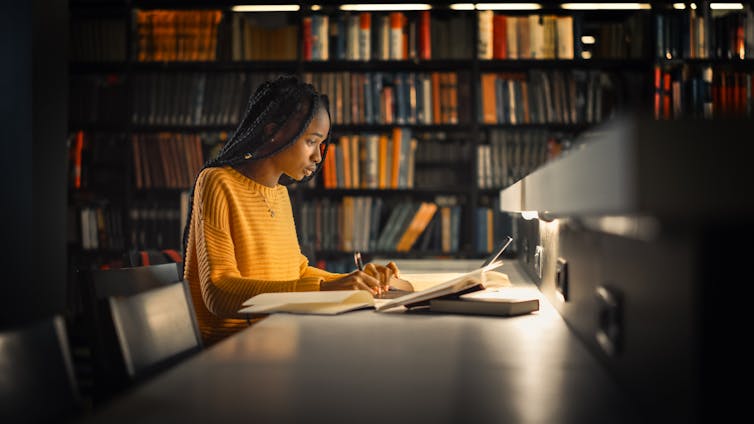

‘You have to suffer for your PhD’: poor mental health among doctoral researchers – new research

Lecturer in Social Sciences, University of Westminster

Disclosure statement

Cassie Hazell has received funding from the Office for Students.

University of Westminster provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

PhD students are the future of research, innovation and teaching at universities and beyond – but this future is at risk. There are already indications from previous research that there is a mental health crisis brewing among PhD researchers.

My colleagues and I studied the mental health of PhD researchers in the UK and discovered that, compared with working professionals, PhD students were more likely to meet the criteria for clinical levels of depression and anxiety. They were also more likely to have significantly more severe symptoms than the working-professional control group.

We surveyed 3,352 PhD students, as well as 1,256 working professionals who served as a matched comparison group . We used the questionnaires used by NHS mental health services to assess several mental health symptoms.

More than 40% of PhD students met the criteria for moderate to severe depression or anxiety. In contrast, 32% of working professionals met these criteria for depression, and 26% for anxiety.

The groups reported an equally high risk of suicide. Between 33% and 35% of both PhD students and working professionals met the criteria for “suicide risk”. The figures for suicide risk might be so high because of the high rates of depression found in our sample.

We also asked PhD students what they thought about their own and their peers’ mental health. More than 40% of PhD students believed that experiencing a mental health problem during your PhD is the norm. A similar number (41%) told us that most of their PhD colleagues had mental health problems.

Just over a third of PhD students had considered ending their studies altogether for mental health reasons.

There is clearly a high prevalence of mental health problems among PhD students, beyond those rates seen in the general public. Our results indicate a problem with the current system of PhD study – or perhaps with academic more widely. Academia notoriously encourages a culture of overwork and under-appreciation.

This mindset is present among PhD students. In our focus groups and surveys for other research , PhD students reported wearing their suffering as a badge of honour and a marker that they are working hard enough rather than too much. One student told us :

“There is a common belief … you have to suffer for the sake of your PhD, if you aren’t anxious or suffering from impostor syndrome, then you aren’t doing it "properly”.

We explored the potential risk factors that could lead to poor mental health among PhD students and the things that could protect their mental health.

Financial insecurity was one risk factor. Not all researchers receive funding to cover their course and personal expenses, and once their PhD is complete, there is no guarantee of a job. The number of people studying for a PhD is increasing without an equivalent increase in postdoctoral positions .

Another risk factor was conflict in their relationship with their academic supervisor . An analogy offered by one of our PhD student collaborators likened the academic supervisor to a “sword” that you can use to defeat the “PhD monster”. If your weapon is ineffective, then it makes tackling the monster a difficult – if not impossible – task. Supervisor difficulties can take many forms. These can include a supervisor being inaccessible, overly critical or lacking expertise.

A lack of interests or relationships outside PhD study, or the presence of stressors in students’ personal lives were also risk factors.

We have also found an association between poor mental health and high levels of perfectionism, impostor syndrome (feeling like you don’t belong or deserve to be studying for your PhD) and the sense of being isolated .

Better conversations

Doctoral research is not all doom and gloom. There are many students who find studying for a PhD to be both enjoyable and fulfilling , and there are many examples of cooperative and nurturing research environments across academia.

Studying for a PhD is an opportunity for researchers to spend several years learning and exploring a topic they are passionate about. It is a training programme intended to equip students with the skills and expertise to further the world’s knowledge. These examples of good practice provide opportunities for us to learn about what works well and disseminate them more widely.

The wellbeing and mental health of PhD students is a subject that we must continue to talk about and reflect on. However, these conversations need to happen in a way that considers the evidence, offers balance, and avoids perpetuating unhelpful myths.

Indeed, in our own study, we found that the percentage of PhD students who believed their peers had mental health problems and that poor mental health was the norm, exceeded the rates of students who actually met diagnostic criteria for a common mental health problem . That is, PhD students may be overestimating the already high number of their peers who experienced mental health problems.

We therefore need to be careful about the messages we put out on this topic, as we may inadvertently make the situation worse. If messages are too negative, we may add to the myth that all PhD students experience mental health problems and help maintain the toxicity of academic culture.

- Mental health

- Academic life

- PhD research

Head of School, School of Arts & Social Sciences, Monash University Malaysia

Chief Operating Officer (COO)

Clinical Teaching Fellow

Data Manager

Director, Social Policy

Mental Health, PhD

Bloomberg school of public health, phd program description.

The PhD program is designed to provide key knowledge and skill-based competencies in the field of public mental health. To gain the knowledge and skills, all PhD students will be expected to complete required coursework, including courses that meet the CEPH competency requirements and research ethics; successfully pass the departmental comprehensive exam; select and meet regularly with a Thesis Advisory Committee (TAC) as part of advancing to doctoral candidacy; present a public seminar on their dissertation proposal; successfully pass the departmental and school-wide Preliminary Oral Exams; complete a doctoral thesis followed by a formal school-wide Final Oral Defense; participate as a Teaching Assistant (TA); attend Grand Rounds in the Department of Psychiatry; and provide a formal public seminar on their own research. Each of these components is described in more detail below. The Introduction to Online Learning course is taken before the start of the first term.

Department Organization

The PhD Program Director, Dr. Rashelle Musci ( [email protected] ), works with the Vice-Chair for Education, Dr. Judy Bass ( [email protected] ), to support new doctoral students, together with their advisers, to formulate their academic plans; oversee their completion of ethics training; assist with connections to faculty who may serve as advisers or sources for data or special guidance; provide guidance to students in their roles as teaching assistants; and act as a general resource for all departmental doctoral students. The Vice-Chair also leads the Department Committee on Academic Standards and sits on the School Wide Academic Standards Committee. Students can contact Drs. Musci or Bass directly if they have questions or concerns.

Within the department structure, there are several standing and ad-hoc committees that oversee faculty and student research, practice and education. For specific questions on committee mandate and make-up, please contact Dr. Bass or the Academic Program Administrator, Patty Scott, [email protected] .

Academic Training Programs

The Department of Mental Health houses multiple NIH-funded doctoral and postdoctoral institutional training programs:

Psychiatric Epidemiology Training (PET) Program

This interdisciplinary doctoral and postdoctoral program is affiliated with the Department of Epidemiology and with the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the School of Medicine. The Program is co-directed by Dr. Peter Zandi ( [email protected] ) and Dr. Heather Volk ( [email protected] ). The goal of the program is to increase the epidemiologic expertise of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals and to increase the number of epidemiologists with the interest and capacity to study psychiatric disorders. Graduates are expected to undertake careers in research on the etiology, classification, distribution, course, and outcome of mental disorders and maladaptive behaviors. The Program is funded with a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Pre-doctoral trainees are required to take the four-term series in Epidemiologic Methods (340.751-340.754), as well as the four-term series in Biostatistics (140.621-624). In addition to the other departmental requirements for the doctoral degree, pre-doctoral trainees must also take four advanced courses in one of the domains of expertise they have selected to pursue: Genetic and Environmental Etiology of Mental Disorders, Mental Health Services and Outcomes, Mental Health and Aging, and Global Mental Health. Pre-doctoral trainees should consult with their adviser and the program director to select courses consistent with their training goals.

Postdoctoral fellows take some courses, depending on background and experience, and engage in original research under the supervision of a faculty member. They are expected to have mastery of the basic principles and methods of epidemiology and biostatistics. Thus, fellows are required to take 340.721 Epidemiologic Inference in Public Health, 330.603 Psychiatric Epidemiology, and some equivalent of 140.621 Statistical Methods in Public Health I and 140.622 Statistical Methods in Public Health II. They may be waived from these requirements by the program director if they can demonstrate equivalent prior coursework.

Drug Dependence Epidemiology Training (DDET) Program

This training program is co-led by Dr. Renee M. Johnson ( [email protected] ) and Dr. Brion Maher ( [email protected] ). The DDET program is designed to train scientists in the area of substance use and substance use disorders. Research training within the DDET Program focuses on: (1) genetic, biological, social, and environmental factors associated with substance use, (2) medical and social consequences of drug use, including HIV/AIDS and violence, (3) co-morbid mental health problems, and (4) substance use disorder treatment and services. The DDET program is funded by the NIH National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The program supports both pre-doctoral and postdoctoral trainees. Pre-doctoral trainees have a maximum of four years of support on the training grant. After completing required coursework, pre-doctoral trainees are expected to complete original research under the supervision of a faculty member affiliated with the DDET program. Postdoctoral trainees typically have two years of support on the training grant. They are required to engage in original research on a full-time basis, under the supervision of a DDET faculty member. Trainees’ research projects must be relevant to the field of substance use.

All trainees are required to attend a weekly seminar series focused on career development and substance use research. The DDET program supports trainees’ attendance at relevant academic meetings, including the Annual Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence (CPDD) each June. Training grant appointments are awarded annually and are renewable given adequate progress in the academic program, successful completion of program and departmental requirements, and approval of the training director.

Pre-doctoral trainees are required to take the required series in epidemiology and biostatistics, as well as The Epidemiology of Substance Use and Related Problems (330.602). In addition, they must take three advanced courses that enhance skills or content expertise in substance use and related problems: one in epidemiology (e.g., HIV/AIDS epidemiology), one in biostatistics, and one in social and behavioral science or health policy. The most appropriate biostatistics course will provide instruction on a method the trainee will use during the thesis research (e.g., survival analysis, longitudinal analysis methods). (Course requirements for trainees from other departments will be decided on a case-by-case basis.)

Postdoctoral trainees are expected to enter the program with mastery of the basic principles and methods of epidemiology and biostatistics. They are required to take The Epidemiology of Substance Use and Related Problems in their first year (330.602), as well as required ethics courses. Postdoctoral trainees are encouraged to take courses in scientific writing and grant writing.

Global Mental Health Training (GMH) Program

The Global Mental Health Training (GMH) Program is a training program to provide public health research training in the field of Global Mental Health. It is housed in the Department of Mental Health , in collaboration with the Departments of International Health and Epidemiology. The GMH Program is supported by a T32 research training grant award from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Dr. Judy Bass ( [email protected] ) is the training program director.

As part of this training program, trainees will undertake a rigorous program of coursework in epidemiology, biostatistics, public mental health and global mental health, field-based research experiences, and integrative activities that will provide trainees with a solid foundation in the core proficiencies of global mental health while giving trainees the opportunity to pursue specialized training in one of three concentration areas that are recognized as high priority: (1) Prevention Research; (2) Intervention Research; or (3) Integration of Mental Health Services Research.

Pre-doctoral trainees are required to take the required series in epidemiology and biostatistics and department of mental health required courses. In addition, they must take three courses that will enhance skills and content expertise in global mental health: 330.620 Qualitative and Quantitative Methods for Mental Health and Psychosocial Research in Low Resource Settings, 224.694 Mental Health Intervention Programming in Low and Middle Income Countries, and 330.680 Promoting Mental Health and Preventing Mental Disorder in Low and Middle Income Countries.

The Mental Health Services and Systems (MHSS) Program

The Mental Health Services and Systems (MHSS) program is an NIMH-funded T32 training program run jointly by the Department of Mental Health and the Department of Health Policy and Management and also has a close affiliation with the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Drs. Elizabeth Stuart ( [email protected] ) and Ramin Mojtabai ( [email protected] ) are the training program co-directors.

The goal of the MHSS Program is to train scholars who will become leaders in mental health services and systems research. This program focuses on producing researchers who can address critical gaps in knowledge with a focus on: (1) how healthcare services, delivery settings, and financing systems affect the well-being of persons with mental illness; (2) how cutting-edge statistical and econometric methods can be used in intervention design, policies, and programs to improve care; and (3) how implementation science can be used to most effectively disseminate evidence-based advances into routine practice. The program strongly emphasizes the fundamental principles of research translation and dissemination throughout its curriculum.

Pre-doctoral trainees in the MHSS program are expected to take a set of core coursework in epidemiology and biostatistics, 5 core courses related to the core elements of mental health services and systems (330.662: Public Mental Health, 330.664: Introduction to Mental Health Services, 140.664: Causal Inference in Medicine and Public Health, 550.601: Implementation Research and Practice, and 306.665: Research Ethics and Integrity), and to specialize in one of 3 tracks: (1) health services and economics; (2) statistics and methodology; or (3) implementation science applied to mental health. Trainees are also expected to participate in a biweekly training grant seminar every year of the program and take a year-long practicum course exposing them to real-world mental health service systems and settings.

For more details see this webpage: http://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/center-for-mental-health-and-addiction-policy-research/training-opportunities/

Epidemiology and Biostatistics of Aging

This program offers training in the methodology and conduct of significant clinical- and population-based research in older adults. This training grant, funded by the National Institute on Aging, has the specific mission to prepare epidemiologists and biostatisticians who will be both leaders and essential members of the multidisciplinary research needed to define models of healthy, productive aging and the prevention and interventions that will accomplish this goal. The Associate Director of this program is Dr. Michelle Carlson ( [email protected]) .

The EBA training grant has as its aims:

- Train pre- and post-doctoral fellows by providing a structured program consisting of: a) course work, b) seminars and working groups, c) practica, d) directed multidisciplinary collaborative experience through a training program research project, and e) directed research.

- Ensure hands-on participation in multidisciplinary research bringing trainees together with infrastructure, mentors, and resources, thus developing essential skills and experience for launching their research careers.

- Provide in-depth knowledge in established areas of concentration, including a) the epidemiology and course of late-life disability, b) the epidemiology of chronic diseases common to older persons, c) cognition, d) social epidemiology, e) the molecular, epidemiological and statistical genetics of aging, f) measurement and analysis of complex gerontological outcomes (e.g, frailty), and g) analysis of longitudinal and survival data.

- Expand the areas of emphasis to which trainees are exposed by developing new training opportunities in: a) clinical trials; b) causal inference; c) screening and prevention; and d) frailty and the integration of longitudinal physiologic investigation into epidemiology.

- Integrate epidemiology and biostatistics training to form a seamless, synthesized approach whose result is greater than the sum of its parts, to best prepare trainees to tackle aging-related research questions.

These aims are designed to provide the fields of geriatrics and gerontology with epidemiologists and biostatisticians who have an appreciation for and understanding of the public health and scientific issues in human aging, and who have the experience collaborating across disciplines that is essential to high-quality research on aging. More information can be found at: https://coah.jhu.edu/graduate-programs-and-postdoctoral-training/epidemiology-and-biostatistics-of-aging/ .

Aging and Dementia Training Program

This interdisciplinary pre- and post-doctoral training program is an interdisciplinary program, funded by the National Institute on Aging, affiliated with the Department of Neurology and the Department of Psychiatry at the School of Medicine, the Department of Mental Health at the School of Public Health and the Department of Psychology and Brain Sciences at the School of Arts and Sciences. The Department of Mental Health contact is Dr. Michelle Carlson ( [email protected] ). The goal of this training program is to train young investigators in age-related cognitive and neuropsychiatric disorders.

Program Requirements

Course location and modality is found on the BSPH website .

Residence Requirements

All doctoral students must complete and register for four full-time terms of a regular academic year, in succession, starting with Term 1 registration in August-September of the academic year and continuing through Term 4 ending in May of that same academic year. Full-time registration entails a minimum of 16 credits of registration each term and a maximum of 22 credits per term.

Full-time residence means more than registration. It means active participation in department seminars and lectures, research work group meetings, and other socializing experiences within our academic community. As such, doctoral trainees are expected to be in attendance on campus for the full academic year except on official University holidays and vacation leave.

Course Requirements

Not all courses are required to be taken in the first year alone; students typically take 2 years to complete all course requirements.

Students must obtain an A or B in all required courses. If a grade of C or below is received, the student will be required to repeat the course. An exception is given if a student receives a C (but not a D) in either of the first two terms of the required biostatistics series, but then receives a B or better in both of the final two terms of the series; then a student will not be required to retake the earlier biostatistics course. However, the student cannot have a cumulative GPA lower than 3.0 to remain in good academic standing. Any other exceptions to this grade requirement must be reviewed and approved by the departmental CAS and academic adviser.

Below are the required courses for the PhD; further Information can be found on the PhD in Mental Health webpage.

BIOSTATISTICS

| Code | Title | Credits |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Methods in Public Health I (first term) | 4 | |

| Statistical Methods in Public Health II (second term) | 4 | |

| Statistical Methods in Public Health III (third term) | 4 | |

| Statistical Methods in Public Health IV (fourth term) | 4 | |

| Total Credits | 16 | |

Must be completed to be eligible to sit for the departmental written comprehensive exams.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

| Code | Title | Credits |

|---|---|---|

| Epidemiologic Methods 1 (first term) | 5 | |

| Epidemiologic Methods 2 (second term) | 5 | |

| Epidemiologic Methods 3 (third term) | 5 |

DEPARTMENT OF MENTAL HEALTH COURSES

| Code | Title | Credits |

|---|---|---|

| Seminars in Research in Public Mental Health (all terms required for first year students) | 1 | |

| Psychopathology for Public Health (first term) | 3 | |

| Public Mental Health (first term) | 2 | |

| Psychiatric Epidemiology (second term) | 3 | |

| Social, Psychological, and Developmental Processes in the Etiology of Mental Disorders (third term) | 3 | |

| PREVENTION of MENTAL DISORDERS: PUBLIC HEALTH InterVENTIONS (third term) | 3 | |

| Introduction to Behavioral and Psychiatric Genetics (fourth term) | 3 | |

| Brain and Behavior in Mental Disorders (fourth term) | 3 | |

| Introduction to Mental Health Services (first term) | 3 | |

| The Epidemiology of Substance Use and Related Problems (second term) | 3 | |

| Statistics for Psychosocial Research: Measurement (first term) | 4 | |

| Grant Writing for the Social and Behavioral Sciences (fourth term) | 3 | |

| Writing Publishable Manuscripts for the Social and Behavioral Sciences (second year and beyond only - second term) | 2 | |

| Doctoral Seminar in Public Mental Health (2nd year PhD students only) | 1 | |

For Department of Mental Health doctoral students, a research paper is required entailing one additional course credit. PH.330.840 Special Studies and Research Mental Health listing Dr. Eaton as the mentor.

COURSE REQUIREMENTS OUTSIDE THE DEPARTMENT OF MENTAL HEALTH

The School requires that at least 18 credit units must be satisfactorily completed in formal courses outside the student's primary department. Among these 18 credit units, no fewer than three courses (totaling at least 9 credits) must be satisfactorily completed in two or more departments of the Bloomberg School of Public Health. The remaining outside credit units may be earned in any department or division of the University. This requirement is usually satisfied with the biostatistics and epidemiology courses required by the department.

Candidates who have completed a master’s program at the Bloomberg School of Public Health may apply 12 credits from that program toward this School requirement. Contact the Academic Office for further information.

SCHOOL-WIDE COURSES

Introduction to Online Learning taken before the first year.

ETHICS TRAINING

PH.550.860 Academic & Research Ethics at BSPH (0 credit - pass/fail) required of all students in the first term of registration.

Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR) connotes a broad range of career development topics that goes beyond the more narrowly focused “research ethics” and includes issues such as conflict of interest, authorship responsibilities, research misconduct, animal use and care, and human subjects research. RCR training requirements for JHPSH students are based on two circumstances: their degree program and their source of funding, which may overlap.

- All PhD students are required to take one of two courses in Responsible Conduct of Research, detailed below one time, in any year, during their doctoral studies.

- All students, regardless of degree program, who receive funding from one of the federal grant mechanisms outlined in the NIH notice below, must take one of the two courses listed below to satisfy the 8 in-person hours of training in specific topic areas specified by NIH (e.g., conflict of interest, authorship, research misconduct, human and animal subject ethics, etc.).

The two courses that satisfy either requirement are:

- PH.550.600 Living Science Ethics - Responsible Conduct of Research [1 credit, Evans]. Once per week, 1st term.

- PH.306.665 Research Ethics and integrity [3 credits, Kass]. Twice per week, 3rd term.

Registration in either course is recorded on the student’s transcript and serves as documentation of completion of the requirement.

- If a non-PhD or postdoctoral student is unsure whether or not their source of funding requires in-person RCR training, they or the PI should contact the project officer for the award.

- Students who have conflicts that make it impossible for them to take either course can attend a similar course offered by Sharon Krag at Homewood during several intensive sessions (sequential full days or half days) that meet either on weekends in October or April, a week in June, or intersessions in January. Permission is required. Elizabeth Peterson ( [email protected] ) can provide details on dates and times.

- Students who may have taken the REWards course (Research Ethics Workshops About Responsibilities and Duties of Scientists) in the SOM can request that this serve as a replacement, as long as they can provide documentation of at least 8 in-person contact hours.

- Postdoctoral students are permitted to enroll in either course but BSPH does not require them to take RCR training. However, terms of their funding might require RCR training and it is their obligation to fulfill the requirement.

- The required Academic Ethics module is independent of the RCR training requirement. It is a standalone module that must be completed by all students at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. This module covers topics associated with maintaining academic integrity, including plagiarism, proper citations, and cheating.

PhD in Mental Health

Department of Mental Health candidates for the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) must fulfill all University and School requirements. These include, but are not limited to, a minimum of four consecutive academic terms at the School in full-time residency (some programs require 6 terms), continuous registration throughout their tenure as a PhD student, satisfactory completion of a Departmental Written Comprehensive Examination, satisfactory performance on a University Preliminary Oral Examination, readiness to undertake research, and preparation and successful defense of a thesis based upon independent research.

PhD Students are required to be registered full-time for a minimum of 16 credits per term and courses must be taken for letter grade or pass/fail. Courses taken for audit do not count toward the 16-credit registration minimum.

Students having already earned credit at BSPH from a master's program or as a Special Student Limited within the past three years for any of the required courses may be able to use them toward satisfaction of doctoral course requirements.

For a full list of program policies, please visit the PhD in Mental Health page where students can find more information and links to our handbook.

Completion of Requirements

The University places a seven-year maximum limit upon the period of doctoral study. The Department of Mental Health students are expected to complete all requirements in an average of 4-5 years.

Learning Outcomes

The PhD program is designed to provide key knowledge and skill-based competencies in the field of public mental health. Upon successful completion of the PhD in Mental Health, students will have mastered the following competencies:

- Evaluate the clinical presentations, incidence, prevalence, course and risk/protective factors for major mental and behavioral health disorders.

- Differentiate important known biological, psychological and social risk and protective factors for major mental and behavioral disorders and assess how to advance understanding of the causes of these disorders in populations.

- Evaluate and explain factors associated with resiliency and recovery from major mental and behavioral disorders.

- Evaluate, select, and implement effective methods and measurement strategies for assessment of major mental and behavioral disorders across a range of epidemiologic settings.

- Critically evaluate strategies for the prevention and treatment of major mental and behavioral disorders as well as utilization and delivery of mental health services over the life course, across a range of settings, and in a range of national contexts.

- Assess preventive and treatment interventions likely to prove effective in optimizing mental health of the population, reducing the incidence of mental and behavioral disorders, raising rates of recovery from disorders, and reducing risk of later disorder recurrence.

According to the requirements of the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH), all BSPH degree students must be grounded in foundational public health knowledge. Please view the list of specific CEPH requirements by degree type .

- Mental Health

- PhD Stories

- Taking Time Off

How I took time out of my PhD to recover

- Posted by by Leafgrabbing

- 15. November 2019

- 7 minute read

After taking two months out of my PhD to reflect, heal and recharge, I have come back with a new focus. A new approach. A much more positive mental attitude. Here is what happened.

My purpose for taking on a PhD has maybe not always been the ‘right’ one. I applied because I was interested in pursuing research on my topic, which is woefully under-researched, particularly with regards to education in divided societies like Northern Ireland, where I come from. Awesome – tick! But, if I’m honest, another BIG push behind me starting a PhD was my fear that I wasn’t good enough to be a teacher, which was my original plan and education.

This fear came off the back of a comment made by another teacher during my first training placement – “maybe you should just think about lecturing adults” . The comment devastated me. Teaching has been the one job I ever really wanted to do. And, no matter the fact that I received an abundance of positive feedback on my teaching style (no one ever doubted my suitability for teaching at secondary level), this stuck with me.

Therefore, I entered into my PhD as a three (more than likely four) year trial that would test my intellect, will-power, endurance, and of course, my mental health .

Impostor syndrome takes its place in the backseat

From my low self-esteem, I adopted a blasé attitude to my work. I always met deadlines, I always did what needed to be done, but I treated my PhD like it was just a stop gap. I didn’t appreciate the position I was in. When I started to think about whether I wanted to do a PhD or not, I felt a deep-seated guilt for wasting the time of my supervisor, my colleagues… even for taking a place with funding that could have gone to someone more deserving.

My issue wasn’t that I didn’t want to do the PhD or that I wasn’t interested in my research. The issue was that I didn’t feel good enough. That I got here by a fluke. My reaction to that was to treat this like something that didn’t really matter or that I didn’t really care about. I had unwittingly been dealing with imposter syndrome .

I worked from home for the majority of my first and second year of research. I lived an hour away from campus and it was quite expensive to travel in every day. However, isolating myself only served to push my self-doubt further. I didn’t appreciate that I had an office full of supportive and encouraging colleagues, who, had I been more present, would have been the best motivation I could have asked for.

My turning point

Then came March 2019, when my world truly felt like it was crumbling around me.

On Sunday 24 th , I received a call from my mum to tell me that my best friend had committed suicide.

The term ‘best friend’ can be thrown about and may, at times, not really reflect the true depth of a friendship. This friend, my best friend, was my first friend. She was the sister I never had. I had never imagined a life without her. She knew everything there was to know about me. When I found out she was gone… I felt totally and completely lost. Incomplete. And for a time, I felt like there was no point to anything.

My supervisor’s reaction

During this time, my supervisor was a godsend. She was one of the first people I contacted when I heard the news. She was kind, empathetic and helped me through reorganising data collection commitments.

Once the dust had settled, she encouraged me to “stop the clock” and take time out of the PhD, so that I could grieve. Instead, I attempted to throw myself back into it.

Ignoring the pain takes its toll

I began preparing for my Annual Progress Review the week after my best friend’s funeral and scheduled in interviews and focus groups.

At the time, I felt like the quality of my data was deteriorating. I wasn’t able to engage as well as I should have with my participants during interviews. They became much more structured and closed – because my own mental health was severely declining.

In qualitative research, you MUST be able to engage with your participants. You must actively listen and ask pertinent, open questions while observing your use of language. When you feel as if you are limply grasping on to the edge of a cliff, this, unsurprisingly, can be difficult to do effectively.

Figuring out what is wrong

I didn’t really understand the influence my mental health was having on my work. Instead, I saw this episode as total incompetence on my side. On reflection, I didn’t fail during that time. The data I collected is not worthless, but, again, my self-doubt drove me to feeling I needed a way out of my PhD.

First, I sought counselling through my university. This was provided by an external organisation. Unfortunately, the counselling provided only allows for four sessions. While my counsellor was incredible, my grief and other issues could not adequately be addressed in such a short space of time. So, while I could give myself a pat on the back for trying, I hadn’t really sought out the level of help I truly needed.

Trying to run away from the problem

One important piece of advice: Do not make rash life-changing decisions while you are experiencing grief or mental health issues. Rather than trying to face my problems, I thought it best to run away.

My form of running away was to apply for a teaching position in my dream school. BIG mistake. During a period of all-time low self-esteem, inability to pick myself up and, in the immortal words of Taylor Swift, “shake it off”, I decided to throw sense to the wind. I was desperate to feel capable of something, to feel worthy. However, in my state at the time, I just opened myself to further disappointment. Needless to say, I didn’t get the job. I’m pretty sure I almost burst into tears during the interview. I had finally hit rock-bottom.

Upon receiving my rejection letter, I emailed my supervisor to ask for the period of temporary withdrawal that she had encouraged me to take long before then. She immediately got the ball rolling and I felt a little more free.

Taking time out of my PhD

My time off didn’t result in the honing of my painting skills, turn me into a guitar player or gain me a second-language. For the most part, I watched A LOT of Netflix and walked my dog around pretty places.

How you use your time really is up to you. I think now of all the things I could have done but I’m here, I feel stronger. Something worked. With my time, I did reflect on what I wanted to do with my life, why I was doing a PhD and what I could do to help myself.

What about quitting?

I flirted with the idea of quitting. My partner (the most patient man in the world) whole-heartedly supported me in whatever decision I wanted to make. However, it was only when I began opening up to friends about how I felt, that I finally started to get a bit of push back: “You only have a year left, why would you even think about leaving?”, “Are you mad?”, “That would be such a waste!” etc.

Initially, I was angry at them for not understanding how bad I felt, how demoralised I was and asking “why the hell weren’t they just patting me on the head and saying ‘there, there, pumpkin’”? I realised I had gotten used to being felt sorry for and it was only enabling my self-doubt and self-pity.

I’ve never told those friends how much they changed me that night but they really did. I decided I was going back to the PhD. I would give it another go. If I didn’t like it when I went back, well, at least I tried.

Being back after taking a break from my PhD

I did make some changes in the run up to starting back. I began to use a bullet journal. This gave me a little bit of a creative outlet while also encouraging me to set tasks and feel like I was able to achieve something, however small, every day.

I created a second Instagram account , removed from my friends or family, so that I could post whatever I wanted, whenever I wanted. I use it to post photos taken on those pretty dog walks and to be reflective regarding my journey through grief. I started exercising more regularly, walking, running, even a little yoga. I tried to adopt a more positive attitude.

I returned at the end of September 2019 and I’m still here.

I’ve recruited my last research site and participants – so I’m on my way to finishing data collection. I’ve attended a HEAP of training and workshops for postgraduates, including one on developing emotional intelligence and resilience – this one was amazing! I’ve started meeting up more with friends and fellow PhD students.

Where I arrived at

I’m trying to keep the positive attitude going and I am, genuinely, enjoying it. I’m in the office at least 4 days a week and I go to the gym regularly. I still have an immense source of support in my supervisor, who I try to be more honest with in terms of what I’m up to work-wise and any doubts I may be having.

I won’t say that my time off fixed everything, but it allowed me the space to grieve without feeling guilty about work. It allowed time to reflect on myself, on who I am and what I want. It gave me a fresh start at this whole PhD thing – at least, in terms of my own approach. I still have off days, but I don’t beat myself up about them or allow myself too much time to wallow.

Take time out of your PhD when you need it

My experience won’t be the same as yours, but maybe there are parts that resonate with you. My advice: Take time out of your PhD when you need it. Share your worries with people who will challenge you when you need to be challenged. Know that there is no shame in seeking professional help. Quitting is always an option but it’s not an easy way out. And, probably a little cliché but still – find a hobby that you actually enjoy.

Megan.

About the author

Megan is entering her third year of PhD study in Northern Ireland, within the field of education. She is Belfast born and bred and began her PhD straight after completing a teaching qualification in secondary education. Megan feels like she made some mistakes in the early days of her PhD, as we all do and wants to share her story about the time when she took time out of her PhD to help others who feel stuck.

What about you? Did you ever take time out of your PhD? Did it help you? Do you know someone who recovered through a PhD break? Share your thoughts in the comments section!

Leave a Comment

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related Articles

- 3 Min Sanity

Build your own safety net

- Posted by by Janika Liebig

- 4 minute read

- Opportunities

Marie Skłodowska-Curie PhD fellowship: How to apply and what to expect

- Posted by by Mónica Fernández Barcia

- Productivity

How to set SMART goals and become more productive

- Posted by by Kristin The PhD

- 3 minute read

Privacy Overview

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 27 April 2022

Navigating mental health challenges in graduate school

- Zachary F. Murguía Burton 1 &

- Xiangkun Elvis Cao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8601-6588 2 , 3

Nature Reviews Materials volume 7 , pages 421–423 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

4 Citations

38 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Institutions

Many graduate students experience mental health struggles that lead them to question their place in academia. Two scientists who experienced extreme lows in graduate school reflect on what helped them during their low points, and suggest strategies for everyone to contribute to mentally healthier workplaces in academia.

We — Elvis and Zack — are two scientists who navigated mental health challenges during graduate school. Elvis is currently a postdoctoral researcher at MIT, and Zack is a mental health advocate and Stanford research affiliate still figuring out what his path as a scientist may look like.

With this piece, we hope to empower students who are facing similar struggles to understand they are not alone, and to call for more support at the institutional level. While we both ended up deciding to complete our PhDs, we want to emphasize that this is not the right choice for everyone — we each have numerous friends and former colleagues who are now leading healthier, happier lives after deciding to leave their graduate programmes. There are many ways to achieve a fulfilling career in and outside of academia, and, most importantly, there are many ways to achieve a fulfilling life.

Elvis’s experience

In November 2016, 3 months into my PhD in Mechanical Engineering at Cornell University, I planned to quit, even though I had wanted to pursue an academic career since my early childhood in China. I struggled to catch up with two advanced-level courses, could not fit into my first lab rotation, lost interest in my research project, and felt isolated as an international student in the small town of Ithaca. Daily frustrations added up to depression. That November, it started snowing in Ithaca, and I felt I had also entered a ‘snow season’ in my life. At that time, I thought pursuing a PhD at Cornell was the worst decision I had ever made and that I could not do it anymore.

Many international students share a similar experience. We choose to hide our struggles from our family and pretend everything is fine during video calls. We simply do not want to make our loved ones over-worried on the other side of the planet. In addition to the isolation from our families, job uncertainty and, for some of us, visa restrictions escalate our anxieties 1 .

I held on. I reached out to old friends back home to rebuild my positivity and confidence. I also spoke to the other international students in my PhD cohort to seek their support. We initially formed a group to support each other during the qualification exam preparation. When I spoke about my mental health challenges, I was surprised to find they resonated a lot with them, and we started openly discussing our issues to get advice from each other.

With the help of the Director of Graduate Studies in my field and the Graduate Field Assistant at Cornell, I switched to another research group within the department. I built connections with new colleagues and became passionate about my new project with the encouragement of my new PhD advisor. An immigrant himself, he provided substantial support: he was always there to help, from guiding my research project to supporting my professional development (for example, he wrote some 20 reference letters for me). After settling into my new research group, I landed on the Forbes 30 Under 30 list for my thesis project, and my side project was featured on the National Institute for Biomedical Imaging’s website . In 2021, I received two postdoctoral fellowships from the MIT Climate & Sustainability Consortium and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation . Pursuing a PhD at Cornell turned out to be the right decision for me.

Looking back, my international peers in the support group helped me navigate the initial struggles in graduate school as I tried to fit into the new environment. The help I received from my department eased the pressure a lot, especially during the lab switch process. The support from my advisor and colleagues in the research group made my pursuit of science in a foreign country an enjoyable experience. As international students and scholars, we will inevitably face many additional challenges in the future, and knowing I have someone to count on greatly relieves my anxiety. I have not seen my family since 2019 owing to COVID, but the friendship and mentorship I received during graduate school made me call Ithaca my new home. More graduate students (especially international students) should be encouraged to form their own support groups and seek institutional support when problems arise. Research groups should be supportive, help lessen feelings of isolation and help students identify solutions for the problems they face.

Zack’s experience

In May 2017, 2 years into my PhD in Geological and Environmental Sciences at Stanford University, I was suicidal. I was hospitalized the morning of my doctoral qualifying exams. For months after, I felt like a failure — I was ashamed, my confidence was destroyed, and I did not think I belonged in academia.

I spent 11 days in the hospital, 6 weeks in all-day group therapy, and 5 months away from my dissertation. But, looking back, taking that time away from academia ended up being the best decision I could have made for my life as a scientist. My mental health crisis taught me the power of unplugging: to take that 2-week vacation; to check in with myself, friends and family rather than checking emails late at night; to actually treat weekends as ‘weekends’.

I also sought support from my California-based family and friends, and — critically — from my PhD advisor. He told me he would continue to fund me, and to take all the time I needed to care for myself. He shared encouraging stories of brilliant scientists he knew with mental health challenges.

Five months after my hospitalization, I passed my qualifying exams.

Since then, I’ve worked for the US Department of Energy and NASA, my research has appeared in Popular Science and CNN , and, in December 2020, I defended my PhD. Beyond the professional opportunities that arose after my lowest point in 2017, I have found purpose in giving back: I share openly about my mental health challenges to foster healthier and more inclusive spaces. I co-created The Manic Monologues (a play showcasing diverse true stories of mental health, made accessible to thousands worldwide), and I have spoken for Amazon’s diversity and inclusion series, NPR and — most meaningfully — for university students and hospital patients like I was.

I still struggle with my mental health. I have many good days, and I also have horrible days. But I am not alone. I take medication and I seek help from health-care professionals when needed, and I have built a wonderful support network of friends, family and colleagues: we all support each other, because we are all in this together.

Mental health issues among graduate students

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, poor mental health was pervasive among graduate students and in academia 2 , 3 . In a 2019 global survey of 6,320 PhD students, 36% of respondents reported seeking help for anxiety or depression caused by their studies 4 . A synthesis of articles published through 2019 yielded a pooled estimate of “clinically significant symptoms of depression” in 24% of PhD students (across 16 studies covering 23,469 students) and of anxiety in 17% of PhD students (across 9 studies covering 15,626 students) — notably higher rates than among young adults in the general population 3 .

The pandemic has exacerbated this already dire situation. A 2020 survey of more than 15,000 graduate students at nine US research universities found that anxiety symptoms rose 50% compared with 2019 (ref. 5 ). The survey found that 32% of graduate students screened positive for symptoms of depression, and 39% screened positive for anxiety 5 . Among faculty, similarly worrying trends are observed. A poll of 1,122 US faculty members found that 70% felt stressed in 2020 versus 32% in 2019 and that more than 50% were seriously considering a career change or early retirement 2 . Another study found moderate to severe signs of mental distress in 78% of UK research staff during the pandemic.

In the USA, international students make up nearly half of all students entering science and engineering graduate programmes . Being an international student comes with many additional mental health challenges, including isolation and separation from family, visa and job prospect uncertainty, acculturation and potential subjection to racism and anti-immigrant rhetoric 4 , 6 , 7 . To make matters worse, mental health impacts may be magnified for groups already most marginalized in STEM and academia, including low-income, first-generation, LGBTQ + , Black, Latinx, Asian, Indigenous, women and non-binary students, as well as students with disabilities and intersecting identities 3 , 5 .

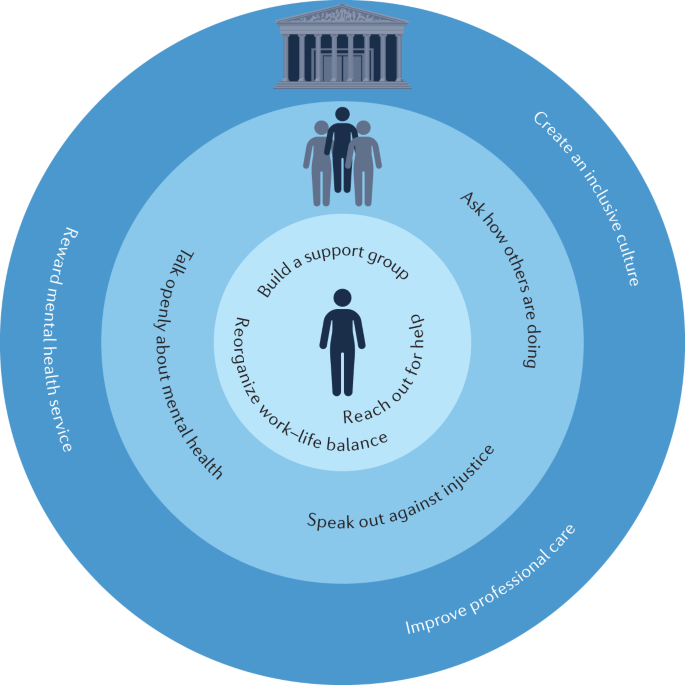

Reflections and strategies for mentally healthier graduate experiences

We navigated our mental health struggles through a combination of reaching out for help (for example, from family, friends, colleagues and supervisors, therapists and mental health professionals), building support groups and finding solidarity among peers, and achieving a better work–life balance by re-organizing priorities and values (Fig. 1 ). Meanwhile, we think it is essential to speak openly about what we went through so that others facing similar challenges know they are not alone. Alongside speaking openly, regular check-ins to see how colleagues are doing and speaking out against injustice are ways we can all help foster mentally healthier environments.

Strategies graduate students and faculty can use for themselves (inner circle) and for others (middle circle), and strategies for institutions to support mentally healthier graduate student experiences (outer circle).

Institutions must also help (Fig. 1 ). In addition to expanding and guaranteeing access to professional mental health services and improving both services and mental health-related policies, institutions must ensure that students are not disadvantaged or implicitly punished for making use of them (for example, via potentially harmful implementation of leave of absence policies ).

Institutions should acknowledge and reward service 8 towards improving mental health. For example, institutions should encourage faculty, staff and students to share vulnerably about their own experiences to create healthier environments and should recognize those who advocate for improved mental health support at the department and university level. Institutions should support and provide resources to graduate students to implement critical social support measures such as peer support groups 9 . Faculty should always strive to foster supportive and positive mentoring relationships with their graduate students, and institutions must support them in doing so. Institutions and graduate advisors alike should support and encourage students in taking healthy breaks when students are feeling stuck, burnt out or overwhelmed (and should explicitly highlight options and examples for taking such breaks). Institutions and faculty should also foster career optimism and remind students that many pathways (both inside and outside of academia and the sciences) can lead to fulfilling careers and lives. Above all, institutions must strive to create an inclusive and supportive culture.

As academics and scientists who faced mental health challenges during graduate school, we are asking individuals and institutions to pay attention to the mental health of students. We must support students — particularly those already under-represented in STEM — to create better workplaces, communities and science for all of us.

If you are struggling right now, you are not alone. We have both been at the lowest of lows. We did not think there was a place for us in academia or in the sciences. But, thankfully, we were wrong. Our lives and careers have never been as fulfilling as they are now.

Finally, we wish to acknowledge that this article is a product of our own experiences and reflections and those of others close to us and, therefore, may not resonate with everyone. Our suggestions similarly cannot be comprehensive in scope, but hopefully may nonetheless further this critical conversation and play some part in bringing about meaningful change to improve mental health support for all.

Cao, X. E., Liu, X. & Zhang, Y. Flourishing as international students and scholars in the US. Matter 5 , 768–771 (2022).

Article Google Scholar

Gewin, V. Pandemic burnout is rampant in academia. Nature 591 , 489–491 (2021).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Satinsky, E. N. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among Ph.D. students. Sci. Rep. 11 , 14370 (2021).

Woolston, C. PhD poll reveals fear and joy, contentment and anguish. Nature 575 , 403–406 (2019).

Woolston, C. Pandemic and panic for US graduate students. Nature 585 , 147–148 (2020).

Mori, S. C. Addressing the mental health concerns of International Students. J. Couns. Dev. 78 , 137–144 (2000).

Ogunsanya, M. E., Bamgbade, B. A., Thach, A. V., Sudhapalli, P. & Rascati, K. L. Determinants of health-related quality of life in international graduate students. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 10 , 413–422 (2018).

Armani, A. M., Jackson, C., Searles, T. A. & Wade, J. The need to recognize and reward academic service. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6 , 960–962 (2021).

Charles, S. T., Karnaze, M. M. & Leslie, F. M. Positive factors related to graduate student mental health. J. Am. Coll. Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1841207 (2021).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

Zachary F. Murguía Burton

Department of Chemical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA

Xiangkun Elvis Cao

MIT Climate & Sustainability Consortium, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Zachary F. Murguía Burton or Xiangkun Elvis Cao .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Related links.