Studies Confirm COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines Safe, Effective for Pregnant Women

Posted on June 1st, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

Clinical trials have shown that COVID-19 vaccines are remarkably effective in protecting those age 12 and up against infection by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. The expectation was that they would work just as well to protect pregnant women. But because pregnant women were excluded from the initial clinical trials, hard data on their safety and efficacy in this important group has been limited.

So, I’m pleased to report results from two new studies showing that the two COVID-19 mRNA vaccines now available in the United States appear to be completely safe for pregnant women. The women had good responses to the vaccines, producing needed levels of neutralizing antibodies and immune cells known as memory T cells, which may offer more lasting protection . The research also indicates that the vaccines might offer protection to infants born to vaccinated mothers.

In one study, published in JAMA [1], an NIH-supported team led by Dan Barouch, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, wanted to learn whether vaccines would protect mother and baby. To find out, they enrolled 103 women, aged 18 to 45, who chose to get either the Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna mRNA vaccines from December 2020 through March 2021.

The sample included 30 pregnant women,16 women who were breastfeeding, and 57 women who were neither pregnant nor breastfeeding. Pregnant women in the study got their first dose of vaccine during any trimester, although most got their shots in the second or third trimester. Overall, the vaccine was well tolerated, although some women in each group developed a transient fever after the second vaccine dose, a common side effect in all groups that have been studied.

After vaccination, women in all groups produced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Importantly, those antibodies neutralized SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern . The researchers also found those antibodies in infant cord blood and breast milk, suggesting that they were passed on to afford some protection to infants early in life.

The other NIH-supported study, published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology , was conducted by a team led by Jeffery Goldstein, Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago [2]. To explore any possible safety concerns for pregnant women, the team took a first look for any negative effects of vaccination on the placenta, the vital organ that sustains the fetus during gestation.

The researchers detected no signs that the vaccines led to any unexpected damage to the placenta in this study, which included 84 women who received COVID-19 mRNA vaccines during pregnancy, most in the third trimester. As in the other study, the team found that vaccinated pregnant women showed a robust response to the vaccine, producing needed levels of neutralizing antibodies.

Overall, both studies show that COVID-19 mRNA vaccines are safe and effective in pregnancy, with the potential to benefit both mother and baby. Pregnant women also are more likely than women who aren’t pregnant to become severely ill should they become infected with this devastating coronavirus [3]. While pregnant women are urged to consult with their obstetrician about vaccination, growing evidence suggests that the best way for women during pregnancy or while breastfeeding to protect themselves and their families against COVID-19 is to roll up their sleeves and get either one of the mRNA vaccines now authorized for emergency use.

References :

[1] Immunogenicity of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in pregnant and lactating women . Collier AY, McMahan K, Yu J, Tostanoski LH, Aguayo R, Ansel J, Chandrashekar A, Patel S, Apraku Bondzie E, Sellers D, Barrett J, Sanborn O, Wan H, Chang A, Anioke T, Nkolola J, Bradshaw C, Jacob-Dolan C, Feldman J, Gebre M, Borducchi EN, Liu J, Schmidt AG, Suscovich T, Linde C, Alter G, Hacker MR, Barouch DH. JAMA. 2021 May 13.

[2] Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccination in pregnancy: Measures of immunity and placental histopathology . Shanes ED, Otero S, Mithal LB, Mupanomunda CA, Miller ES, Goldstein JA. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 May 11.

[3] COVID-19 vaccines while pregnant or breastfeeding . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Barouch Laboratory (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston)

Jeffery Goldstein (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Posted In: News

Tags: breast milk , breastfeeding , cord blood , COVID-19 , COVID-19 vaccine , gynecology , infants , Moderna vaccine , mRNA vaccine , neutralizing antibodies , obstetrics , pandemic , Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine , placenta , pregnancy , pregnancy complications , SARS-CoV-19 variants , SARS-CoV-2 , T cells , women's health

27 Comments

How could they know that? There haven’t been any long-term studies and VAERS is backlogged with reports of adverse reactions. Slow down and focus on the elderly in our country and other countries.

Yes, effective in 12 year olds and older but myocarditis and pericarditis are being investigated currently with this age group. Statistically zero hospitalization and fatality rate for this age group. Risk-Benefit?

I’m an elderly person. Was vaccinated two months ago. My doctor ordered many routine blood test last week for my autoimmune conditions, including an antibody test, to see if I got enough protection and I don’t have any changes. No side effects. Feel great.

I agree! They should end public phase III trials, wait and sit back and really analyze the saers data and wait for the many independent studies to finalize.. Covid curve is down and this is pretty much aftermath. To many professionals warning against theae injections and we don’t know any real life long term effects either.

Go read the study. It explained how that came to believe this.

Agree 100%. They indicate it’s safe for the mother because there was “no damage to the placenta”, but how can they possibly know what the long-term effects will be on either the mother or the baby???

As for the article’s author, ” appear to be completely safe for pregnant women” – remind yourself to do that statistics refresher course.

As a layman American I want to thank everyone for all they did to fight the epidemic, BUT, I have to think – realizing hindsight is 20/20, but still – IF we had, after the first mRNA vaccines were prepared, given the makers of them a green light to vaccinate people at high risk of severe Covid, or if they were unwilling, FORCED them to make the vaccines in large quantities, to be bought by the government, then administered to high risk people on a voluntary basis, we might have kept serious illness way down. If this had been started in March and April, when the first testing of the two mRNA vaccines we are using now began, how many people could have been vaccinated before the midsummer surge, let alone the holiday peaks in states previously not much effected? I am going to say something I know will offend many medical people – I do not feel we learned from this epidemic – not very much – if we had another epidemic, and a vaccine was developed quickly, I believe it would be withheld, for, operationally, about a year, while the epidemic destroyed the country. The reasons given for withholding the vaccine will be, essentially, we’ve always done it this way and we can’t change that just because we have a once in a century pandemic. In the circumstances we faced – not solely the virus, which was very bad, but ultimately, shown to be mostly a threat to old folks, – but the REACTION to the virus, which was extremely destructive, generally – EVERY possible strategy should have been on the table. I see a massive failure I am very angry about, but worse, I think our enemies have seen the failures, and now know one more epidemic like this will destroy the US. We need to have a better plan for a future epidemic and I see no sign we will.

These studies do not address safety, they address effectiveness in pregnant and breast feeding women. The study from Chicago looked at placentas and at antibody levels. The authors assume the lack of placental abnormalities equals safety in the 33 (30% of the 80 enrolled) women whose placentas were examined. The study suffers from being underpowered and the populations were not controlled for. The JAMA paper enrolled a total of 103 women, 30 were vaccinated while pregnant. The results were entirely on immunogenicity with only a mention of “no severe adverse events or pregnancy or neonatal complications were observed.” An n of 30 is not an adequate study to infer anything. This study is way underpowered as well and too small to find any majority much less uncommon adverse events. For those who like to say they follow the science you need to read the papers Blogs like this one reference. There is virtually no meaningful safety data in either of these studies, despite what the blog states. Both studies do, however, give us effectiveness data.

Thank you for your call out on the lack of clarity on this study. I am a woman of child bearing age with uncertainty if I will choose to have another child or not. At this point, I want the raw data from the studies – vaccination prior to pregnancy and during and the outcomes of the vaccinated individuals and their offspring. Not the findings of the data as they’ve been extrapolated by an individual or a group of medical professionals with good intentions but an unconscious bias. I asked my OB for a place where I could start to collect the data as it comes in (given the fact that we are just beginning to see women who may have received the vaccine prior to pregnancy and the outcomes of the pregnancy) and she could not point me to any single data source. She could only “reassure” me that ACOG promotes the vaccine. Again, I don’t need an endorsement by well intended medical professionals. I need the data so I can make an informed, educated decision on my own.

E x a c t l y ‼️

What are your qualifications to evaluate this study?

She sounds pretty knowledgeable to me, but…

If you think she’s wrong, you should have no trouble pointing out why from the papers themselves, rather than questioning her qualifications, a far weaker argument.

There are many, many more pregnant women who have taken the vaccine without being part of a research study. Myself included. If just one had adverse effects so far, it would have made international news. Even if it wasn’t caused by the vaccine. Pregnant women are at increased risk of hospitalization/death from the virus and the general public is at risk of the formation of vaccine-resistant variants popping up due to unvaccinated people. It was a great relief to me to know I wouldn’t play a part in anyone else getting sick. And that my healthy and happy newborn is likely to have immunity. When the vaccines are approved for younger children, I will happily have my 3-1/2 year-old vaccinated!

“If just one had adverse effects so far, it would have made international news. Even if it wasn’t caused by the vaccine.” Are you sure about that…. since our news sources are so clearly biased in encouraging ‘the jab’. It must be easy for others to say “pregnant women should get the vaccine” when they are in fact not pregnant and faced with that difficult decision. There are soo many things pregnant women should not consume or inject in their bodies while pregnant, but others are quick to say a 1 year old vaccine that nobody really knows the long term effects of, is okay for pregnant women. 1 year ago did they predict a booster shot would be needed? No. I rest my case.

When gets the vaccine to the public?

Thank you very much for this very important post.

The value of trust in research studies and their publication. And summary write ups….is vitally important. When a write up over simplifies. Or let’s a casual reader draw am incorrect safety if efficacy conclusion. Beware. As trust. Is vital if this part of our county and world culture wants an vital and happily invited family member at our future crisis and holiday and every dinner table. Break trust. And the family member will be sat in the corner with the face to the wall. Trust and good data transparency and clear not deceptive summaries are vital. The choice to keep this family member at our dinner table. Or not. Is being asked by too many who see to many reasons not to trust. I think it is a vital member. But like a five year old. Needs to know the value of truth.

Spanish flu was a vaccine 60,000,000 dead. 1917 WW1

The first study only looked at antibody response, it was not a safety study. Why are you even mentioning it here? The second study only ensured that the vaccine didn’t cause an immune response to the placenta? That is important, but by itself is a very weak and limited outcome measure. They did not even follow through to see if there was any injury to the newborns. And really, it will take a few years before more subtle neurological damage would even be noticeable. And the sample size is tiny.

These are the studies on which the NIH is basing the claim that the vaccine does not cause reproductive harm? This is shocking and disgraceful. We need accountability.

We should just wait then, until we absolutely KNOW that everyone is SAFE from the vaccine. We can do a longitudinal study of say, 25 years? At that point, many of the infants exposed to the vaccine will be adults and you’ll have you definitive data. If everything looks good at that point, then you can get the vaccine for a virus that is 25 years old and likely doesn’t even resemble the original virus that caused the disease in the first place. Leave the vaccine out of it entirely until we KNOW for CERTAIN beyond ALL doubt that this thing is safe and take your chances on contracting the disease itself. I am glad my parents didn’t wait for the longitudinal Polio study to conclude, but, that being said, this sounds like a solid risk assessment strategy to me.

These studies are weak. Far too small and have not looked at the babies. If this is what we are basing the “safe and effective” mantra on then we are truly lost. Amazing double standard when compared with the kind of evidence they are demanding for early treatments such as ivermectin or fluvoxamine. Hard not to be a conspiracy theorist.

n June 25, the FDA added new warnings for both vaccine provider and recipients to their fact sheets on Pfizer and Moderna over rare cases of heart inflammation called myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) and pericarditis (inflammation of the lining outside the heart). The agency added the warnings just two days after the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) met and confirmed the “likely association” between myocarditis and pericarditis and the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, both of which use mRNA. However, it’s rare, treatable, and usually mild, they say.

Looks like some very helpful information! I read the entire article, and I love the writing style and passion in your posts . . .

I received the first dose of fed Pfizer vaccine when I was only a few weeks pregnant. (I didn’t know that I was pregnant at the time.) I received the second dose the end of January. I carried my baby to term, and I’m happy to say I have a very healthy, happy baby!! I had zero complications during pregnancy and in labor.

Thanks for sharing, good luck with your newborn.

Thank you for sharing such an informative blog with us. I found this very useful for everyone . . .

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

@nihdirector on x, nih on social media.

Kendall Morgan, Ph.D.

Comments and Questions

If you have comments or questions not related to the current discussions, please direct them to Ask NIH .

You are encouraged to share your thoughts and ideas. Please review the NIH Comments Policy

- Visitor Information

- Privacy Notice

- Accessibility

- No Fear Act

- HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- USA.gov – Government Made Easy

Discover more from NIH Director's Blog

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

COVID-19 Vaccines While Pregnant or Breastfeeding

- Everyone ages 6 months and older is recommended to get the updated COVID-19 vaccine, including people who are pregnant, breastfeeding a baby, trying to get pregnant now, or who might become pregnant in the future.

- COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy is safe and effective.

- COVID-19 vaccines are not associated with fertility problems in women or men.

- Infants ages 6 months and older are recommended to get the updated COVID-19 vaccine even if born to people who were vaccinated or had COVID-19 before or during pregnancy.

- If you are pregnant or were recently pregnant, you are more likely to get very sick from COVID-19, compared to those who are not pregnant. Additionally, if you have COVID-19 during pregnancy, you are at increased risk of complications that can affect your pregnancy and your baby from serious illness from COVID-19.

People Who Are Pregnant

Safety and effectiveness of covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy, common questions about vaccination during pregnancy, people who are breastfeeding a baby, people who would like to have a baby, vaccine side effects.

If you are pregnant or were recently pregnant, you are:

- More likely to get very sick from COVID-19 compared to those who are not pregnant.

- More likely to need hospitalization, intensive care, or the use of a ventilator or special equipment to breathe if you do get sick from COVID-19. Severe COVID-19 illness can lead to death.

- At increased risk of complications that can affect your pregnancy and baby including, preterm birth or stillbirth.

COVID-19 vaccination remains the best protection against COVID-19-related hospitalization and death for you and your baby . CDC recommendations align with those from professional medical organizations including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists , Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, and American Society for Reproductive Medicine .

Studies including hundreds of thousands of people around the world show that COVID-19 vaccination before and during pregnancy is safe, effective, and beneficial to both the pregnant person and the baby. The benefits of receiving a COVID-19 vaccine outweigh any potential risks of vaccination during pregnancy. Data show:

- COVID-19 vaccines do not cause COVID-19, including in people who are pregnant or their babies. None of the COVID-19 vaccines contain live virus. They cannot make anyone sick with COVID-19, including people who are pregnant or their babies. Learn more about how vaccines work .

- It is safe to receive an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Moderna or Pfizer-BioNTech), before and during pregnancy. Both vaccines show no increased risk for complications like miscarriage, preterm delivery, stillbirth, or birth defects . 1,2

- mRNA COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy are effective. They reduce the risk of severe illness and other health effects from COVID-19 for people who are pregnant. COVID-19 vaccination might help prevent stillbirths and preterm delivery. 1-4

- COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy builds antibodies that can help protect the baby. 4,5

- Receiving mRNA COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy can help protect babies younger than age 6 months from hospitalization due to COVID-19.

- Most babies hospitalized with COVID-19 were born to pregnant people who were not vaccinated during pregnancy. 6-8

Scientific studies to date have shown no safety concerns for babies born to people who were vaccinated against COVID-19 during pregnancy. Based on how these vaccines work in the body, experts believe they are unlikely to pose a risk for long-term health effects. CDC continues to monitor, analyze, and disseminate information from people vaccinated during all trimesters of pregnancy to better understand effects on pregnancy and babies.

CDC and professional medical organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, recommend COVID-19 vaccination at any point in pregnancy . COVID-19 vaccination can protect you from getting very sick from COVID-19. Keeping yourself as healthy as possible during pregnancy is important for the health of your baby.

Pregnant people can choose which updated COVID-19 vaccine to get.

Children, teens, and adults, including pregnant people, may get a COVID-19 vaccine and other vaccines, including a flu vaccine, at the same time.

If you would like to speak to someone about the COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy, you can talk to your healthcare provider. You can also contact MotherToBaby, whose experts are available to answer questions in English or Spanish by phone or chat. This service is free and confidential. To reach MotherToBaby:

- Call 1-866-626-6847

- Text 855-999-3525

- Chat Click the MotherToBaby Live Chat window

CDC recommends that people who are breastfeeding a baby, and infants 6 months of age and older, get vaccinated and stay up to date with their COVID-19 vaccines .

Vaccines are safe and effective at preventing COVID-19 in people who are breastfeeding a baby. Available data on the safety of COVID-19 vaccination while breastfeeding indicate no severe reactions after vaccination in the breastfeeding person or the breastfed child. 9 There has been no evidence to suggest that COVID-19 vaccines are harmful to either people who have received a vaccine and are breastfeeding or to their babies. 10

Studies have shown that people who are breastfeeding a baby and have received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines have antibodies in their breast milk, which could help protect their babies. 9,10

CDC also recommends COVID-19 vaccines for children aged 6 months and older .

CDC recommends that people who are trying to get pregnant now or might become pregnant in the future , as well as their partners, stay up to date and get the updated COVID-19 vaccine. COVID-19 vaccines are not associated with fertility problems in women or men. COVID-19 vaccines are not associated with fertility problems in women or men .

People who are pregnant have not reported different side effects from people who are not pregnant after vaccination with mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines). 1,2

- Fever during pregnancy, for any reason, has been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

- Fever in pregnancy may be treated with acetaminophen as needed, in moderation, and in consultation with a healthcare provider.

- Learn more about possible side effects and rare severe allergic reactions after receiving a COVID-19 vaccine.

To find COVID-19 vaccine locations near you: Search vaccines.gov , text your ZIP code to 438829, or call 1-800-232-0233.

Related Pages

- Allergic Reactions

For Healthcare and Public Health

- Considerations for the Use of COVID-19 Vaccines in the United States

- COVID-19 Vaccination among Pregnant People

- Management of Anaphylaxis after COVID-19 Vaccination

- ACOG Vaccine Confidence Training

- ACOG Recommendations for Vaccinating Pregnant People

- ACOG video about COVID-19 vaccines for people who are pregnant

- COVID-19 Clinical and Professional Resources

- Clinic Poster: Protect yourself and your baby from COVID-19

- Clinic Poster: Protect yourself and your baby from COVID-19 (Español)

More Information

- Mother-To-Baby: Information for people who are pregnant or breastfeeding a baby

- Pregnant and Protected from COVID-19 | CDC Foundation

- Fleming-Dutra KE, Zauche LH, Roper LE, Ellington SR, Olson CK, Sharma AJ, Woodworth KR, Tepper N, Havers F, Oliver SE, Twentyman E, Jatlaoui TC. Safety and Effectiveness of Maternal COVID-19 Vaccines Among Pregnant People and Infants. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2023 Jun;50(2):279-297. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2023.02.003

- Prasad, S., Kalafat, E., Blakeway, H. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and perinatal outcomes of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat Commun 13, 2414 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30052-w

- Schrag SJ, Verani JR, Dixon BE, et al. Estimation of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine Effectiveness Against Medically Attended COVID-19 in Pregnancy During Periods of Delta and Omicron Variant Predominance in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2233273. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.33273

- Piekos SN, Price ND, Hood L, Hadlock JJ. The impact of maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination on maternal-fetal outcomes. Reprod Toxicol. 2022;114:33-43. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2022.10.003

- Yang YJ, Murphy EA, Singh S, et al. Association of Gestational Age at Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccination, History of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection, and a Vaccine Booster Dose With Maternal and Umbilical Cord Antibody Levels at Delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology: 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004693

- Halasa NB, Olson SM, Staat MA, et al. Maternal Vaccination and Risk of Hospitalization for Covid-19 among Infants. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(2):109-119. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2204399

- Hamid S, Woodworth K, Pham H, et al. COVID-19–Associated Hospitalizations Among U.S. Infants Aged <6 Months — COVID-NET, 13 States, June 2021–August 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:1442–1448. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7145a3

- Simeone RM, Zambrano LD, Halasa NB, et al. Effectiveness of Maternal mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination During Pregnancy Against COVID-19–Associated Hospitalizations in Infants Aged <6 Months During SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Predominance — 20 States, March 9, 2022–May 31, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72:1057–1064. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7239a3

To receive email updates about COVID-19, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 18 March 2022

SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy

- Victoria Male ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5654-5083 1

Nature Reviews Immunology volume 22 , pages 277–282 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

31k Accesses

95 Citations

1334 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Reproductive biology

SARS-CoV-2 infection poses increased risks of poor outcomes during pregnancy, including preterm birth and stillbirth. There is also developing concern over the effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the placenta, and these effects seem to vary between different viral variants. Despite these risks, many pregnant individuals have been reluctant to be vaccinated against the virus owing to safety concerns. We now have extensive data confirming the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy, although it will also be necessary to determine the effectiveness of these vaccines specifically against newly emerging viral variants, including Omicron. In this Progress article, I cover recent developments in our understanding of the risks of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy, and how vaccination can reduce these.

Similar content being viewed by others

Proactive vaccination using multiviral Quartet Nanocages to elicit broad anti-coronavirus responses

Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations

Imprinting of serum neutralizing antibodies by Wuhan-1 mRNA vaccines

Introduction.

Viruses that cause pneumonia, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), have long been known to be of particular concern during pregnancy 1 . So as the world entered the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in early 2020, clinicians and scientists working in obstetrics knew that their patients were likely to be at increased risk. Initially, lockdowns and a tendency towards risk avoidance masked some of the increased risks associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy 2 , 3 , but with the passing of time the risks have become clearer. Although pregnant people were excluded from the first trials of COVID-19 vaccines, the pressing need to protect this group meant that the vaccines were rolled out to them in advance of the completion of clinical trials, and we now have extensive real-world data confirming the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines during pregnancy. In this Progress article, I cover recent developments in our understanding of the risks of SARS-CoV-2 infection that are specific to pregnancy, and how vaccination can safely reduce these.

SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy

Obstetric outcomes following sars-cov-2 infection.

Pregnancy is associated with increased disease severity in those infected with SARS-CoV-2: a meta-analysis of 92 studies comparing outcomes for pregnant patients with COVID-19 with age and sex-matched non-pregnant patients with COVID-19 found that pregnancy increases the risk of needing intensive care (OR 2.13, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.54–2.95), invasive ventilation (OR 2.59, CI 2.28–2.94) and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (OR 2.02, CI 1.22–3.34), although the risk of all-cause mortality was not increased (OR 0.96, CI 0.79–1.18) 4 . A more recent meta-analysis of 111 studies, which compared outcomes for pregnant patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 with those who were not infected, found that infection significantly increased the odds of premature delivery (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.22–1.8), pre-eclampsia (OR 1.6, CI 1.2–2.1), stillbirth (OR 2.36, CI 1.24–4.46), neonatal mortality (OR 3.35, CI 1.07–10.5) and maternal mortality (OR 3.08, CI 1.5–6.3) 5 .

Since the publication of these meta-analyses, further large studies have also found increased risks of maternal morbidity and mortality 6 , preterm birth (PTB) and perinatal death associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy 7 , 8 . There is also evidence that both maternal 9 and neonatal 10 outcomes were worse during the Delta wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic than in preceding periods.

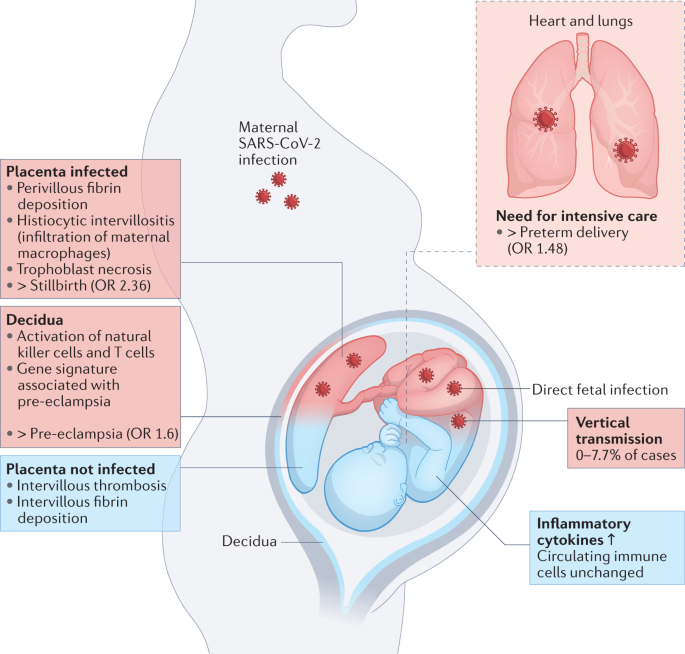

The increased risk of PTB associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection seems to be driven largely by iatrogenic PTBs, with doctors opting to deliver the infant to try to save the critically ill patient 11 . The increased risk of stillbirth and pre-eclampsia are more likely to be associated with inflammatory changes affecting the placenta (Fig. 1 ).

Maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection can impact pregnancy in numerous ways. The need for intensive care associated with severe disease can necessitate delivering the infant, causing an increased rate of preterm delivery. Placental infection can be associated with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis, which is associated with an increased risk of stillbirth. Even in the absence of placental infection, inflammatory changes are observed in the decidua and placenta, and these may be linked to the increased risk of pre-eclampsia associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy. SARS-CoV-2 can also be vertically transmitted to infect the fetus, although this is uncommon. Blue indicates indirect outcomes on the fetus and placenta associated with maternal infection with SARS-CoV-2, whereas red indicates outcomes associated with direct fetal infection.

SARS-CoV-2 and the placenta

The placenta expresses the cellular receptors for SARS-CoV-2, namely angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , and some patients with COVID-19 do become viraemic 16 , meaning there is the potential for SARS-CoV-2 infection of the placenta. However, SARS-CoV-2 viraemia in pregnancy seems to be uncommon 12 , and there is little placental co-expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2, which is required for the canonical route of virus entry into the cell 12 , 13 , 14 . Moreover, placental expression of ACE2 declines over the course of pregnancy 15 .

In addition to the general defences the placenta has against viral infection 17 , these factors might be expected to protect the placenta from infection with SARS-CoV-2. Indeed, placental infection seems to be uncommon. However, SARS-CoV-2-associated coagulation and inflammation occur even in the absence of placental infection, most commonly manifesting as intervillous thrombosis and fibrin deposition 12 , 15 , 18 , 19 , 20 . The mucosal lining of the uterus is a maternal tissue into which the placenta implants and, in pregnancy, is called the decidua. Examination of the decidua in pregnancies affected by SARS-CoV-2 demonstrated local activation of maternal natural killer cells and T cells, including the expression of gene signatures associated with pre-eclampsia 15 , 21 .

A more severe inflammatory syndrome occurs when the placenta does become infected; namely, SARS-CoV-2 placentitis. This is characterized by histiocytic intervillositis, perivillous fibrin deposition and trophoblast necrosis, and is emerging as a risk factor for fetal distress or demise 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 . A series of 68 cases of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis associated with either stillbirth or neonatal death found that the causes of death were likely to be fetal hypoxic-ischaemic injury resulting from severe placental damage, rather than fetal infection with SARS-CoV-2. Indeed, placental infection with SARS-CoV-2 does not necessarily equate with fetal infection; in this case series, infection of the fetus was only confirmed in 2 of the 68 cases 26 .

SARS-CoV-2 and the fetus

Numerous studies have reported SARS-CoV-2 infection in infants born to infected individuals. The largest of these have examined infection by nasopharyngeal swab, finding the rate at which infants test positive for SARS-CoV-2 as between 0.9 and 2.8% 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 . However, infants who test positive in this way have not necessarily been infected in utero, as they may have been infected by horizontal transmission shortly after birth.

Numerous smaller studies have examined umbilical cord blood to more accurately identify those neonates infected by vertical transmission. Although the fetus begins producing both IgG and IgM between 12 and 20 weeks of gestation, maternal IgG can cross the placenta so only the presence of IgM signals fetal exposure to antigen. In pregnancies affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection, detection of Spike-specific IgM in cord blood has been reported in between 0 and 7.7% of cases 21 , 27 , 31 . A systematic review of studies examining the presence of the viral genome in cord blood found it in 2.9% of cases 27 , although since then a larger case series of 64 deliveries was unable to detect the viral genome in the umbilical cord blood of any infant 12 .

Increased levels of inflammatory cytokines have been observed in the cord blood of neonates, even in the absence of placental infection 21 , 32 . It is unclear whether these cytokines were produced locally by the fetus or reflect maternal cytokines that have crossed the placenta 33 . However, the findings that immune cells in cord blood show higher cytokine production if the pregnancy was affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection and that IL-8 concentrations are generally higher in cord blood than that in maternal blood suggest that at least some of these cytokines may be produced by the neonate 32 .

New variants, new outcomes?

One important caveat to much of the preceding data is that they were collected in earlier waves of the pandemic, in which the predominant variants of SARS-CoV-2 were different from those we face now. Of particular concern is that reports of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis were rare in the first wave, caused by the original strain of SARS-CoV-2, but became increasingly common in the Alpha and Delta variant waves of the pandemic 24 , 25 . This demonstrates that we cannot necessarily assume that obstetric outcomes will be the same in the current wave, or in future ones, as they have been previously. At the time of writing, we do not have solid data on how the Omicron wave has affected pregnant people.

Vaccine safety in pregnancy

Benefits of vaccination in pregnancy.

Vaccination in pregnancy to prevent maternal morbidity and mortality, or to confer passive immunity to the infant, has a long and successful history 34 . As early as 1879, it was noticed that infants born to individuals who received the smallpox vaccine during pregnancy were themselves protected, and similar observations were made for pertussis and tetanus vaccination in the middle of the twentieth century. Similar to SARS-CoV-2 infection, infection with influenza virus in pregnancy is associated with increased maternal morbidity and, as a result, influenza vaccination in pregnancy has been recommended in the United States since 1997, although it was not until 2005 that clinical trials formally demonstrated its benefits. In the United Kingdom, influenza and pertussis vaccination have been routinely offered in pregnancy since 2010 and 2012, respectively.

Safety of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy

The increased potential for severe consequences following SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy makes COVID-19 vaccination of this population particularly attractive. However, pregnant patients naturally want to know whether vaccination is safe for them and their infants. Although we await clinical trial data in this population, pregnant people have been vaccinated against COVID-19 since December 2020, and we now have safety data from more than 185,000 individuals vaccinated during pregnancy (Table 1 ).

Because the first countries to offer the COVID-19 vaccine in pregnancy, namely the United States and Israel, were using the mRNA vaccines BNT162b2 (Pfizer) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna), the first data available were on these vaccines. As a result, when other countries later made the vaccines available in pregnancy, many preferentially offered mRNA vaccines to this group. Because of this, mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines have been most widely used in pregnancy and, therefore, the majority of safety data come from these vaccines.

A key finding with regards to safety is that IgM is not detected in umbilical cord blood following vaccination in pregnancy 31 , 35 , 36 . This indicates that the vaccine has not elicited an immune response in the fetus, suggesting that it has not crossed the placental barrier. In line with this, one study that looked for SARS-CoV-2 Spike mRNA or protein in placenta and cord blood following vaccination was unable to detect it 36 . COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy is also not associated with pathological changes to the placenta 37 . These findings indicate that a direct effect of vaccination on fetal development is unlikely. However, local and systemic immune reactions to COVID-19 vaccination do occur in pregnant people, at roughly the same rate at which they occur in the general population 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 . Therefore, it is important to consider the possibility that the immune response to COVID-19 vaccination could affect the placenta or fetus and undertake epidemiological studies to determine whether it could be associated with any poor obstetric outcome. Such studies have taken one of three broad approaches: registry studies, case–control studies and cohort studies (Table 1 ).

Registry studies

Registry studies recruit participants at the time of vaccination, determine the outcomes of their pregnancies and compare the rates at which adverse events occur in the registry population relative to those seen either in the general pregnant population or during pregnancy historically. The first such study used the v-safe pregnancy registry of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Among 713 people vaccinated in pregnancy who had given birth by 30 March 2021, the rates of adverse events were the same as have been reported historically 38 , and a follow-up study looking at 1,613 vaccinated people who had given birth by September 2021 continued to find a normal rate of adverse events 42 . Focusing only on those vaccinated before 20 weeks, there was also no increased risk of miscarriage following vaccination 43 .

The Better Outcomes Registry and Network (BORN) comprises 64,234 people vaccinated against COVID-19 during pregnancy in Ontario, Canada. Of the 31,343 individuals who had given birth by 31 October 2021, the rate of stillbirth, PTB or infants being born small for their gestational age was not increased, compared with either historical data or the background rate 44 . A study of 18,399 people vaccinated against COVID-19 during pregnancy in Scotland found no increased risk of PTB or neonatal mortality, compared with the general pregnant population 8 . An early registry study in Israel examined only 390 people vaccinated with BNT162b2 during pregnancy, but also found no increased risk of miscarriage, PTB or infants being born small for their gestational age 41 .

Case–control studies

Case–control studies identify individuals who experience a predefined adverse event and determine whether those people are more likely to have experienced a particular exposure than those who did not experience the event. Two such studies have been done in the US Vaccine Safety Datalink system, which includes 31,080 people vaccinated during pregnancy. One of these studies found no indication that COVID-19 vaccination is linked to stillbirth 45 ; the second found that people who experienced a miscarriage were no more likely to have been vaccinated in the preceding 28 days than those who did not miscarry 46 . A similar study carried out in Norway found that, among 18,447 pregnancies, those that ended in miscarriage were no more likely to have received a COVID-19 vaccine in either the preceding 3-week or 5-week period than those that continued 47 .

Cohort studies

Cohort studies examine the outcomes for those who are vaccinated against COVID-19 in pregnancy, compared with the outcomes of a contemporary cohort of unvaccinated people. Because the participants in these studies have not been randomized to vaccination, there are systematic differences between those who chose to receive a COVID-19 vaccine and those who declined, although the majority of studies attempt to control for these variables, either with multivariate analysis 48 , 49 , 50 or by identifying pairs matched for potential confounders 51 , 52 . Among seven cohort studies there was no increased risk of miscarriage 52 , pre-eclampsia 49 , 52 , 53 or any adverse outcome at the time of birth 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 associated with COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. One study that followed up infants after birth, to an average of 134 days, also found no increased risk of death or hospitalization in the first months of life in infants born following vaccination during pregnancy 50 .

Although each of these approaches to addressing the question of COVID-19 vaccine safety in pregnancy has its own weakness, the findings from each approach lend weight to the others. Together with the sheer number of participants in these studies, this gives us confidence that COVID-19 vaccination is not associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Vaccine efficacy

Effectiveness of covid-19 vaccination in pregnancy.

Although it is untrue to say that the immune system is weakened in pregnancy, it does differ from the non-pregnant state, with a shift away from cell-mediated immune responses. This is demonstrated by the long-standing observation that cell-mediated autoimmune diseases tend to go into remission during pregnancy, whereas antibody-mediated diseases can flare 55 . It is therefore not unreasonable to ask whether COVID-19 vaccination is as effective at preventing disease during pregnancy as it is in the broader population.

Early attempts to answer this question looked at vaccine immunogenicity in pregnant participants, compared with age and sex-matched non-pregnant controls. Two reports found that the titres of anti-Spike, anti-RBD (receptor binding domain of the Spike protein) and SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies were the same in the two groups 39 , 56 . Importantly, both of these studies found higher virus-specific antibody titres associated with COVID-19 vaccination compared with SARS-CoV-2 infection, underlining the benefits of vaccination even in those who have already been infected. A third study, using systems serology, also found that overall titres of antibodies did not differ between the groups but further revealed that after only one dose of vaccine, antibody effector functions were induced with delayed kinetics in the pregnant group compared with the non-pregnant group: following the second dose, there was no significant difference between the groups 57 . Comparing vaccine responses across trimesters using this approach, the same team also found a subtle reduction in antibody effector functions following vaccination in the second trimester, compared with vaccination in the first or third trimesters, which might reflect trimester-specific immune alterations that are known to be associated with a somewhat more quiescent state in the second trimester 58 . Comparing T cell responses, it was shown that Spike-induced production of IFNγ by total and central memory CD4 + and CD8 + T cells following vaccination did not differ between pregnant and non-pregnant groups 56 .

More recently, two cohort studies from Israel have enabled an estimate of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness during pregnancy, finding it to be roughly the same as in the general population 52 , 59 . UK surveillance data have not been used to model vaccine effectiveness, but nevertheless point to COVID-19 vaccination being effective in pregnancy, particularly against severe disease 60 . In Scotland, 68% of the pregnant population was unvaccinated by October 2021, but unvaccinated individuals accounted for 77.4% of all SARS-CoV-2 infections, 90.9% of COVID-19 hospitalizations and 98% of intensive care unit admissions among pregnant people; furthermore, all perinatal deaths following SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy occurred in unvaccinated individuals 8 . These data sets were collected largely during the period when the Alpha variant was dominant, but with some contribution from the Delta wave. As the Omicron variant becomes prominent, it will be important to determine the effectiveness of vaccination specifically against this strain, how this varies following a booster dose and the extent to which protection wanes over time. It will also be necessary to determine the extent to which vaccination provides protection specifically against COVID-19-associated pregnancy complications.

Protection of infants by maternal COVID-19 vaccination

As expected, maternal IgG raised by vaccination during pregnancy crosses the placenta and is present in umbilical cord blood at birth 31 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 56 , 58 , 61 , 62 , 63 , remaining detectable in the blood of more than half of infants at 6 months 61 . Transplacental transfer of IgG following vaccination against tetanus and pertussis provides infants with protection against these diseases, and by analogy, COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy may provide infants with some protection against COVID-19. Early estimates suggest that vaccination after 20 weeks of pregnancy is 80% effective (95% CI, 55–91%) and vaccination before 20 weeks is 32% effective (95% CI, 43–68%) at preventing hospitalization of infants younger than 6 months old with COVID-19 (ref. 64 ).

This increased protection of infants following vaccination later in pregnancy is in line with findings that maximum cord blood antibody titres are achieved when vaccination occurs in the late second to early third trimester 62 , 63 . This is likely to reflect higher maternal IgG titres at the time of birth when vaccination has occurred more recently, as the efficiency of Spike-specific IgG transfer across the placenta is highest following vaccination in the first trimester 58 . However, it is important to be clear that the main benefit of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy is the reduction in risk of disease during pregnancy. Therefore, the timing of vaccination should seek to optimize protection during pregnancy, rather than that of the infant after birth.

Notably, the titres of anti-Spike antibodies seen in cord blood are lower following SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy compared with COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy 56 , 61 . This is likely to be a result of both lower maternal IgG titres being elicited by infection compared with vaccination 56 , 61 and also because the transport of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies is compromised following SARS-CoV-2 infection in the third trimester 12 , 65 .

SARS-CoV-2 infection poses significant risks to pregnant people and their infants, but COVID-19 vaccination is safe in pregnancy. This underlies the recommendation that pregnant people receive the COVID-19 vaccine, which is now being made by public health bodies all over the world 66 , 67 . Despite these recommendations, in many countries uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine in pregnancy remains low, so it is essential that we continue to communicate this message to those who are making the decision about COVID-19 vaccination, for themselves and their infants. Although it is understandable that this group might feel cautious, the task has been made more difficult by the proliferation of misinformation about the safety of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Strong public health messaging is needed, but more importantly we must ensure that midwives and obstetricians are adequately equipped to counsel their patients on the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination.

Di Mascio, D. et al. Outcome of coronavirus spectrum infections (SARS, MERS, COVID-19) during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2 , 100107 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Docherty, A. B. et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with COVID-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ 369 , m1985 (2020).

Molteni, E. et al. Symptoms and syndromes associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection and severity in pregnant women from two community cohorts. Sci. Rep. 11 , 6928 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Allotey, J. et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 370 , m3320 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Marchand, G. et al. Review and meta-analysis of COVID maternal and neonatal clinical features and pregnancy outcomes to June 3rd 2021. AJOG Glob. Rep. 3 , 100049 (2021).

Google Scholar

Metz, T. D. et al. Association of SARS-CoV-2 infection with serious maternal morbidity and mortality from obstetric complications. JAMA 327 , 748–759 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Piekos, S. N. et al. The effect of maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection timing on birth outcomes: a retrospective multicentre cohort study. Lancet Digit. Health 4 , e95–e104 (2022).

Stock, S. J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland. Nat. Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01666-2 (2022).

Strid, P. et al. COVID-19 severity among women of reproductive age with symptomatic laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 by pregnancy status — United States, Jan 1, 2020–Sep 30, 2021. ResearchSquare https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1090075/v1 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

The National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit. Key information on COVID-19 in pregnancy. NPEU www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/npeu-news/MBRRACE-UK_Rapid_COVID_19_DEC_2021_-__Infographic_v13.pdf (2021).

Vousden, N. et al. The incidence, characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women hospitalized with symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in the UK from March to September 2020: a national cohort study using the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS). PLoS ONE 16 , e0251123 (2021).

Edlow, A. G. et al. Assessment of maternal and neonatal SARS-CoV-2 viral load, transplacental antibody transfer, and placental pathology in pregnancies during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 3 , e2030455 (2020).

Pique-Regi, R. et al. Does the human placenta express the canonical cell entry mediators for SARS-CoV-2? eLife 9 , e58716 (2021).

Ashary, N. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq identifies cell subsets in human placenta that highly expresses factors driving pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8 , 783 (2020).

Lu-Culligan, A. et al. Maternal respiratory SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy is associated with a robust inflammatory response at the maternal–fetal interface. medRxiv 2 , 591–610 (2021).

Fajnzylber, J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality. Nat. Commun. 11 , 5493 (2020).

Delorme-Axford, E., Sadovsky, Y. & Coyne, C. B. The placenta as a barrier to viral infections. Ann. Rev. Virol. 1 , 133–146 (2014).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Mulvey, J. J., Magro, C. M., Ma, L. X., Nuovo, G. J. & Baergen, R. N. Analysis of complement deposition and viral RNA in placentas of COVID-19 patients. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 46 , 151530 (2020).

Prabhu, M. et al. Pregnancy and postpartum outcomes in a universally tested population for SARS-CoV-2 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 127 , 1548–1556 (2020).

Smithgall, M. C. et al. Third-trimester placentas of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-positive women: histomorphology, including viral immunohistochemistry and in-situ hybridization. Histopathology 77 , 994–999 (2020).

Garcia-Flores, V. et al. Maternal–fetal immune responses in pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 13 , 320 (2022).

Watkins, J. C., Torous, V. F. & Roberts, D. J. Defining severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) placentitis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 145 , 1341–1349 (2021).

Linehan, L. et al. SARS-CoV-2 placentitis: an uncommon complication of maternal COVID-19. Placenta 104 , 261–266 (2021).

Shook, L. L. et al. SARS-CoV-2 placentitis associated with B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant and fetal distress or demise. J. Infect. Dis. 225 , 754–758 (2022).

Fitzgerald, B. et al. Fetal deaths in Ireland due to SARS-CoV-2 placentitis caused by SARS-CoV-2 Alpha. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2021-0586-SA (2022).

Schwartz, D. A. et al. Placental tissue destruction and insufficiency from COVID-19 causes stillbirth and neonatal death from hypoxic-ischemic injury: a study of 68 cases with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis from 12 countries. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2022-0029-SA (2022).

Kotlyar, A. M. et al. Vertical transmission of coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 224 , 35–53 (2021).

Woodworth, K. R. et al. Birth and infant outcomes following laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy — SET-NET, 16 jurisdictions, March 29–October 14, 2020. MMWR 69 , 1635–1640 (2020).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Flaherman, V. J. et al. Infant outcomes following maternal infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): first report from the Pregnancy Coronavirus Outcomes Registry (PRIORITY) study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 73 , e2810–e2813 (2021).

Norman, M. et al. Association of maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy with neonatal outcomes. JAMA 325 , 2076–2086 (2021).

Beharier, O. et al. Efficient maternal to neonatal transfer of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. J. Clin. Invest. 131 , e150319 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gee, S. et al. The legacy of maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection on the immunology of the neonate. Nat. Immunol. 22 , 1490–1502 (2021).

Dahlgren, J. et al. Interleukin-6 in the maternal circulation reaches the rat fetus in mid-gestation. Pediatr. Res. 60 , 147–151 (2006).

Mackin, D. W. & Walker, S. P. The historical aspects of vaccination in pregnancy. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 76 , 13–22 (2021).

Mithal, L. B., Otero, S., Shanes, E. D., Goldstein, J. A. & Miller, E. S. Cord blood antibodies following maternal coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination during pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 225 , 192–194 (2021).

Prahl, M. et al. Evaluation of transplacental transfer of mRNA vaccine products and functional antibodies during pregnancy and early infancy. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.09.21267423 (2021).

Shanes, E. D. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccination in pregnancy: measures of immunity and placental histopathology. Obstet. Gynecol. 138 , 281–283 (2021).

Shimabukuro, T. T. et al. Preliminary findings of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N. Engl. J. Med. 384 , 2273–2282 (2021).

Gray, K. J. et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine response in pregnant and lactating women: a cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 225 , 303 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Kadali, R. A. K. et al. Adverse effects of COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccines among pregnant women: a cross-sectional study on healthcare workers with detailed self-reported symptoms. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 225 , 458–460 (2021).

Bookstein Peretz, S. et al. Short-term outcome of pregnant women vaccinated with BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 58 , 450–456 (2021).

Olson, C. K. COVID-19 vaccine safety in pregnancy: updates from the v-safe COVID-19 Vaccine Pregnancy Registry . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2021-09-22/09-COVID-Olson-508.pdf (2021).

Zauche, L. H. et al. Receipt of mRNA COVDID-19 vaccines and risk of spontaneous abortion. N. Engl. J. Med. 385 , 1533–1535 (2021).

BORN Ontario. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy in Ontario. BORN Ontario https://www.bornontario.ca/en/whats-happening/covid-19-vaccination-during-pregnancy-in-ontario.aspx (2021).

Kharbanda E. O. Safety of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy, interim data from the Vaccine Safety Datalink. Centers for Disease Control https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2021-09-22/10-COVID-Kharbanda-508.pdf (2021).

Kharbanda, E. O. et al. Spontaneous abortion following COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. JAMA 326 , 1629–1631 (2021).

Magnus, M. C. et al. Covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy and first-trimester miscarriage. N. Engl. J. Med. 385 , 2008–2010 (2021).

Lipkind, H. S. et al. Receipt of COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy and preterm or small-for-gestational-age at birth — eight integrated health care organizations, United States, December 15, 2020–July 22, 2021. MMWR 71 , 26–30 (2022).

Wainstock, T., Yoles, I., Sergienko, R. & Sheiner, E. Prenatal maternal COVID-19 vaccination and pregnancy outcomes. Vaccine 39 , 6037–6040 (2021).

Goldshtein, I. et al. Association of BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy with neonatal and early infant outcomes. JAMA Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0001 (2022).

Blakeway, H. et al. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: coverage and safety. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 10 , S0002–S9378 (2021).

Goldshtein, I. et al. Association between BNT162b2 vaccination and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women. JAMA 326 , 728–735 (2021).

Theiler, R. N. et al. Pregnancy and birth outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 3 , 100467 (2021).

UK Health Security Agency. COVID-19 vaccine surveillance report. Week 4. UK Health Security Agency https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1050721/Vaccine-surveillance-report-week-4.pdf (2022).

Buyon, J. P. The effects of pregnancy on autoimmune diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 6 , 281–287 (1998).

Collier, A. Y. et al. Immunogenicity of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in pregnant and lactating women. JAMA 325 , 2370–2380 (2021).

Atyeo, C. et al. COVID-19 mRNA vaccines drive differential antibody Fc-functional profiles in pregnant, lactating, and nonpregnant women. Sci. Transl. Med. 13 , eabi8631 (2021).

Atyeo, C. et al. Maternal immune response and placental antibody transfer after COVID-19 vaccination across trimester and platforms. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.12.21266273 (2021).

Dagan, N. et al. Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in pregnancy. Nat. Med. 27 , 1693–1695 (2021).

Vousden, N. et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 variant on the severity of maternal infection and perinatal outcomes: data from the UK Obstetric Surveillance System national cohort. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.22.21261000 (2021).

Shook, L. L. et al. Durability of anti-spike antibodies in infants after maternal COVID-19 vaccination or natural infection. JAMA 327 , 1087–1089 (2022).

Rottenstreich, A. et al. Timing of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy and transplacental antibody transfer: a prospective cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 3 , S1198–S1743 (2021).

Yang, Y. J. et al. Association of gestational age at coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination, history of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, and a vaccine booster dose with maternal and umbilical cord antibody levels at delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 139 , 373–380 (2021).

Halasa, N. B. et al. Effectiveness of maternal vaccination with mRNA COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy against COVID-19-associated hospitalization in infants aged <6 months — 17 states, July 2021–January 2022. MMWR 71 , 264–270 (2022).

Atyeo, C. et al. Compromised SARS-CoV-2-specific placental antibody transfer. Cell 184 , 628–642 (2021).

UK Health Security Agency. Pregnant women urged to come forward for COVID-19 vaccination. GOV.UK https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pregnant-women-urged-to-come-forward-for-covid-19-vaccination (2021).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 vaccine monitoring systems for pregnant people. CDC https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/safety/monitoring-pregnant-people.html (2021).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Metabolism, Digestion and Reproduction, Imperial College London, London, UK

Victoria Male

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Victoria Male .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declared no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Male, V. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol 22 , 277–282 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00703-6

Download citation

Accepted : 28 February 2022

Published : 18 March 2022

Issue Date : May 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00703-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Sars-cov-2 vaccination may mitigate dysregulation of il-1/il-18 and gastrointestinal symptoms of the post-covid-19 condition.

- Claudia Fischer

- Edith Willscher

- Christoph Schultheiß

npj Vaccines (2024)

COVID-19 Vaccination and Reproductive Health: a Comprehensive Review for Healthcare Providers

- Yaima Valdes

- Braian Ledesma

- Himanshu Arora

Reproductive Sciences (2024)

The COVID-19 International Drug Pregnancy Registry (COVID-PR): Protocol Considerations

- Diego F. Wyszynski

- Aris T. Papageorghiou

- Sonia Hernández-Díaz

Drug Safety (2024)

Intrauterine transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to and prenatal ultrasound abnormal findings in the fetus of a pregnant woman with mild COVID-19

- Meixiang Zhang

- Liqiong Hou

- Yingchun Luo

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2023)

Commentary: Predicting adverse outcomes in pregnant patients positive for SARS-CoV-2 by a machine learning approach

- Noemi Salmeri

- Massimo Candiani

- Paolo Ivo Cavoretto

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Microbiology newsletter — what matters in microbiology research, free to your inbox weekly.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

News releases.

News Release

Wednesday, June 23, 2021

NIH begins study of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy and postpartum

Researchers will evaluate antibody responses in vaccinated participants and their infants.

A new observational study has begun to evaluate the immune responses generated by COVID-19 vaccines administered to pregnant or postpartum people. Researchers will measure the development and durability of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in people vaccinated during pregnancy or the first two postpartum months. Researchers also will assess vaccine safety and evaluate the transfer of vaccine-induced antibodies to infants across the placenta and through breast milk.

The study, called MOMI-VAX, is sponsored and funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health. MOMI-VAX is conducted by the NIAID-funded Infectious Diseases Clinical Research Consortium (IDCRC) .

“Tens of thousands of pregnant and breastfeeding people in the United States have chosen to receive the COVID-19 vaccines available under emergency use authorization. However, we lack robust, prospective clinical data on vaccination in these populations,” said NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., “The results of this study will fill gaps in our knowledge and help inform policy recommendations and personal decision-making on COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy and in the postpartum period.”

Pregnant people with COVID-19 are more likely to be hospitalized, be admitted to the intensive care unit, require mechanical ventilation, and die from the illness than their non-pregnant peers. Severe COVID-19 during pregnancy also may put the infant at risk for complications such as preterm birth. Individuals who are pregnant or breastfeeding can choose to receive authorized COVID-19 vaccines, and studies to gather safety data in these populations are ongoing. So far, COVID-19 vaccines appear to be safe in these populations. The NIAID study will build on these studies by improving the understanding of antibody responses to COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant and postpartum people and the transfer of antibodies to their infants during pregnancy or through breast milk. Experience with other diseases suggests that the transfer of vaccine-induced antibodies from mother to baby could help protect newborns and infants from COVID-19 during early life.

Investigators will enroll up to 750 pregnant individuals and 250 postpartum individuals within two months of delivery who have received or will receive any COVID-19 vaccine authorized or licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Their infants also will be enrolled in the study. Vaccines are not provided to participants as part of the study protocol. Currently, three COVID-19 vaccines are available in the United States under emergency use authorization: the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccines and the Johnson & Johnson adenoviral vector vaccine. The study is designed to assess up to five types of FDA-licensed or authorized COVID-19 vaccines, should additional options become available.

Participants and their infants will be followed through the first year after delivery. To assess the development and durability of vaccine-induced antibodies overall and by vaccine type and vaccine platform, researchers will analyze blood samples collected from pregnant and postpartum participants. These samples will be collected at study enrollment; at delivery for participants who enrolled during pregnancy; and two, six, and 12 months after delivery. Pregnant participants enrolled in the study prior to receiving the vaccine will have blood drawn at enrollment as well as approximately one month after vaccination. To assess transfer of antibodies through the placenta and the levels and durability of antibodies in infants, researchers will perform antibody testing on samples from umbilical cord blood collected at delivery and blood samples collected from infants two and six months after delivery.

Investigators also will assess the potential effects on maternal immune responses and transfer of antibodies across the placenta according to the mother’s age, the trimester of pregnancy during which the vaccine was received, the mother’s health, and the mother’s COVID-19 risk status. Additionally, mothers will have the option of providing breast milk samples at approximately two weeks, two months, six months, and 12 months after delivery. The investigators will evaluate breast milk antibodies to assess the potential for protection against COVID-19 in breastfed infants. Study staff also will gather information on COVID-19 illnesses in pregnant and postpartum participants, birth and neonatal outcomes, and COVID-19 illnesses in infant participants.

The work is led by principal investigators Flor M. Munoz, M.D., of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and Richard H. Beigi, M.D., of University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. The study will be conducted at up to 20 clinical research sites nationwide. More information about the study, including a list of sites, is available on the IDCRC website .

NIAID conducts and supports research—at NIH, throughout the United States, and worldwide—to study the causes of infectious and immune-mediated diseases, and to develop better means of preventing, diagnosing and treating these illnesses. News releases, fact sheets and other NIAID-related materials are available on the NIAID website .

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov .

NIH…Turning Discovery Into Health ®

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Ann Med Surg (Lond)

- v.72; 2021 Dec

Covid-19 vaccine and its consequences in pregnancy: Brief review

Nang kham oo leik.

a Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia

Fatimah Ahmedy

b Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia

Rhanye Mac Guad

c Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia

Dg Marshitah Pg Baharuddin

Pregnancy is linked to a higher incidence of severe Covid-19. It's critical to find safe vaccinations that elicit protective pregnant and fetal immune responses. This review summarises the rate of COVID-19 infection, maternal antibodies responsiveness, placenta antibody transmission, and adverse events after COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy studied in epidemiological studies evaluating mRNA vaccines. Potential COVID-19 infection in pregnant women can be prevented using mRNA-based vaccinations. Gestation, childbirth, and perinatal mortality were proven unaffected by COVID-19 vaccination. Injection-site discomfort, tiredness, and migraine are the most prevalent side effects, but these are temporary. After the first dosage of vaccinations, fast antibody responses were demonstrated. The adaptive immunity is found to be more significant after booster vaccination, and is linked to improved placental antigen transmission. Two vaccination doses are associated with more robust maternal and fetal antibody levels. Longer delays between the first immunization dosage and birth are linked to greater fetal IgG antibody levels with reduction in antigen transmission proportion. The mRNA vacciness are effective in reducing the severity of COVID-19 infection and these vaccinations are regarded to be safe options for pregnant women and their unborn fetus.

- • mRNA vacciness are effective and regarded safe for reducing the severity of COVID-19 infection in pregnancy.

- • Injection-site discomfort, tiredness, and migraine are the most prevalent side effects, but these are temporary.

- • Adaptive immunity is more significant after booster vaccination with improved placental antigen transmission.

- • Longer delay between first immunization and birth is linked to higher fetal IgG antibody level and lower antigen transmission.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 infection in pregnancy leads to expansion of the respiratory tract and increases the susceptibility of expectant mother for acquiring respiratory diseases [ 1 ]. A pro-inflammatory stage is more evident during the first trimester where embryonic and placental implantation occur, as well as within the third trimester for adaptation towards delivery [ 2 ]. In particular, cytokine outbursts production is linked to acute COVID-19. This pro-inflammatory stage of gestation throughout the first and third trimesters rendered pregnant women to be more susceptible for more severe presentations of COVID-19 infection. Although the majority of pregnant mothers experienced mild to moderate symptoms with COVID-19 infection, the illness is more severe in this group compared to non-pregnant females, with a higher risk of hospitalization. Most of the hospitalized expectant mothers with COVID-19 infection were asymptomatic, allowing the virus to spread unnoticed [ 3 ]. This demonstrates the importance of effective measure that halt the viral transmission from one person to another.

One of the most effective public health measures to counter the spread of communicable diseases is through vaccination. The main goal of nationwide vaccination programs is to accomplish the desired herd immunity, but only if high vaccination rate is achieved [ 4 ]. mRNA vaccine, Moderna and Pfizer–BioNTech, are proven to be effective in preventing and reducing the severity of COVID-19 infections. However, the evidence on mRNA vaccines’ safety profile and effectiveness during pregnancy are gradually emerging [ 5 ].

This brief review intends to summarise the rate of COVID-19 infection, maternal antibodies responsiveness, placenta antibody transmission, and adverse events after COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. The data involved the outcomes of epidemiological studies that evaluated two different mRNA vaccines; Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine and Moderna vaccine. The outcomes from this review should help to enhance the understanding on COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy for assisting healthcare professionals on counselling expectant mothers.

1.1. COVID-19 infection after vaccination