Essay on Organizational Culture

Organizational culture: essay introduction, project management & organizational design, the importance of culture in an organization: formal management vs parent company, organizational culture: essay conclusion.

Culture in an organization refers to the values, beliefs, history and attitudes of a particular organization. Culture also refers to the ideals of an organization that dictate the way members of the organization relate to each other and to the outside environment.

An organization’s culture defines its values; the values of an organization refer to the ideology that the members of an organization have as pertains their goals and the mechanisms to be used to achieve these goals. The organization’s values map out the way employees are required to behave and relate to each other in the workplace (Allan, 2004).

There is a very important need to develop healthy cultures in all organizations whether they are religious, commercial or institutional. The culture of an organization determines how it is perceived both by its own employees and its stakeholders. The managers of an organization are said to be able to influence the culture of the organization. This can be done by the implementation of various policies that lead to a culture change.

Many organizations have two types of cultures, the culture that management wants to enforce and a culture that dictates the relationships of the employees among each other. Many institutions have been found to have a persistent and hidden culture among the employees. This is the biggest task to organizational management; how to replace the employee culture with the desired culture (Young, 2007).

There are two types of culture; namely strong culture and weak culture. Strong culture is whereby the actions and beliefs of the employees are guided by the values of the company. Such a culture ensures smooth and efficient flow of an organization’s activities. Strong cultures result in successful and united organizations.

Weak culture on the other hand refers to instances where the activities of the employees are not guided by the values of the company. A weak culture results in the need for a strict administration that is bureaucratic so as to ensure that the company’s activities flow well. Weak cultures result in increased overheads and under motivated employees.

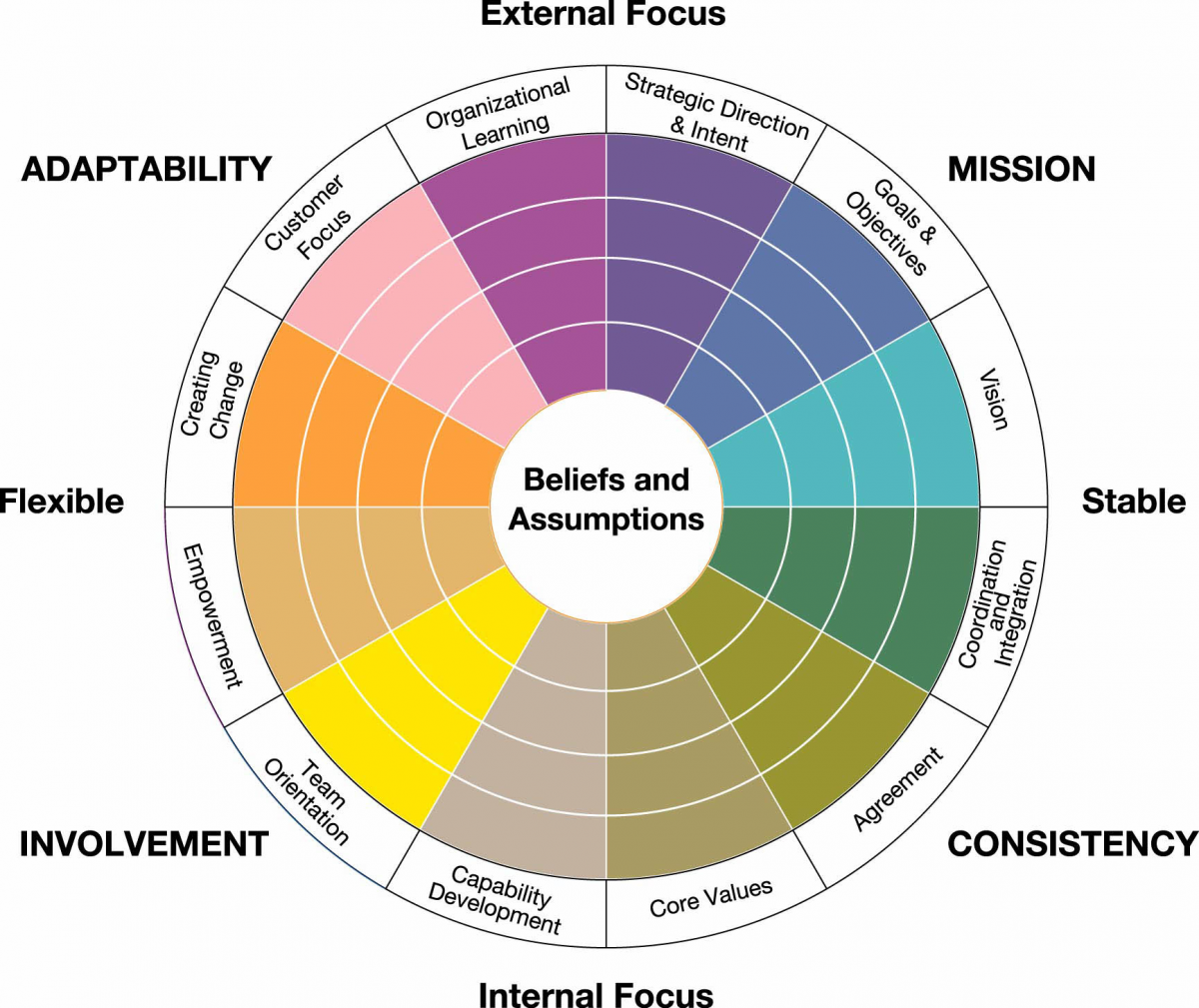

Fig. 1: Organization culture (Burke, 1999).

There are five dimensions of an organization’s culture namely power distance, risk taking tendencies, gender issues and employee psychology. The power distance aspect refers to the mentality among the employees on who wields more power and how much power they wield.

This will vary among organizations as some have more powerful managers as compared to others. Risk taking tendencies refers to the willingness of the employees and the organization to take risks in an attempt to grow and improve (Jack et al, 2003). Employee psychology on the other hand is an aspect that covers issues such as individualism and collectiveness mentalities in an organization. Companies that have a collective psychology have been found to work and do well as compared to individualistic ones.

The individualistic psychology has been found to cause a lack of coordination and flow of activities in organizations. Lastly the gender dimension refers to the mentality of an organization’s employees towards members of the male and female genders. Companies that view women as weaker and disadvantaged sexes have been found to discriminate among each other and result in a reduction of the employee cooperation levels (Jack et al, 2003).

There are four types of cultures in modern day organizations, role cultures, power cultures, person cultures and task cultures. Role cultures exist in organized and systematic organizations where the amount of power that an employee has is determined by the need that they fulfill in the organization.

Power cultures are those that have a few powerful individuals who are required to drive and direct the rest of the organization. Person cultures are cultures that exist when an organization’s employees feel superior to the company; this is a common culture in most law firms and firms that are formed by individual professionals who merge with others to form organizations. A tasks culture is a culture that is geared towards accomplishing tasks and doing things.

It is very important to understand the culture of an organization so as to enable an organization to map out the type of management that suits it. Culture as mentioned, is the accepted standard in which the employees of an organization relate to each other and to the stakeholders.

There are several factors that affect the culture of an organization. These include technological exposure, environmental conditions, geographical situation, organizational rules and procedures and influence of organizational peers on a subject. Such factors affect the culture of an organization and in the long run its management structure (Johnstone et al, 2002).

Organizational cultures can have both positive and negative effects on the organization. Negative and unwanted cultures are those that oppose change in an organization. These cultures have the tendency of inhibiting the innovation and implementation of change in an organization. Therefore the understanding of an organization’s culture can be used to determine:

- Why certain projects of the organization have failed or are failing

- Aspects of the culture that hinder innovation and change

- What needs to corrected so as to improve how the organization operates

- The origin of certain culture within an organization

- Measures that can be taken so as to introduce new culture or improve on the current culture

An in depth understanding of an organization’s culture is important so as to allow project managers and other managers to affect the mode in which activities are carried out. To influence the performance of the organization an understanding of its cultures is very necessary so as it enables the management to filter its employees and choose performers from non performers (Johnstone et al, 2002).

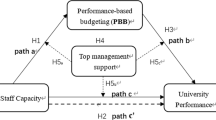

The proper understanding of organizational culture and its use in deciding a suitable management structure cannot be stressed further. The success of a project depends on how it is managed. There are three major types of project management namely; project, functional and matrix management structures.

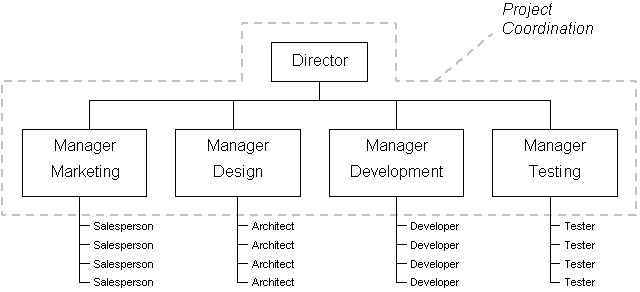

Functional management refers to the type of management that focuses on specialty areas and skills. The departments and responsibilities are determined by the skills of the members. There is vertical and horizontal communication between the departments. To allow operation of all arms of the organization bureaucratic means are used so as to ensure smooth flow of the business.

This type of management tends to reduce operational costs and encourage the specialization of labour. Specialization in turn leads to better efficiency and standardization of activities. Disadvantages of the functional approach include the integration of budgets, operational plans and procedures into the project activities making it cumbersome to implement (Kloppenborg, 2009).

Fig.1: Functional project management (Young, 2007).

Project based organization on the other hand is whereby the activities of a company are organized according to its ongoing projects. This type of management is based on the objectivity principle that emphasizes the importance of solid objectives in improving the efficiency of an organization’s processes.

This principle is used in scenarios that require the efficient management of projects that involve activities from different disciplines e.g. medicine, engineering, law.

The advantages of such management techniques include the fact that power and responsibility is decentralized and is carried out by managers of different teams. Such a management technique also allows for the proper utilization of time, leads to reduced cost and enhanced quality levels. Such a management technique is suitable for certain company profiles and cultures, for example:

- Management of large projects and organizations that require the delegation of responsibilities

- Situations with restricted cost and specification parameters

- Situations that require the coordination and completion of projects from different but interrelated disciplines

- In cultures that value responsibility and accountability of ones actions / decisions

- Cultures that encourage communication among all management levels

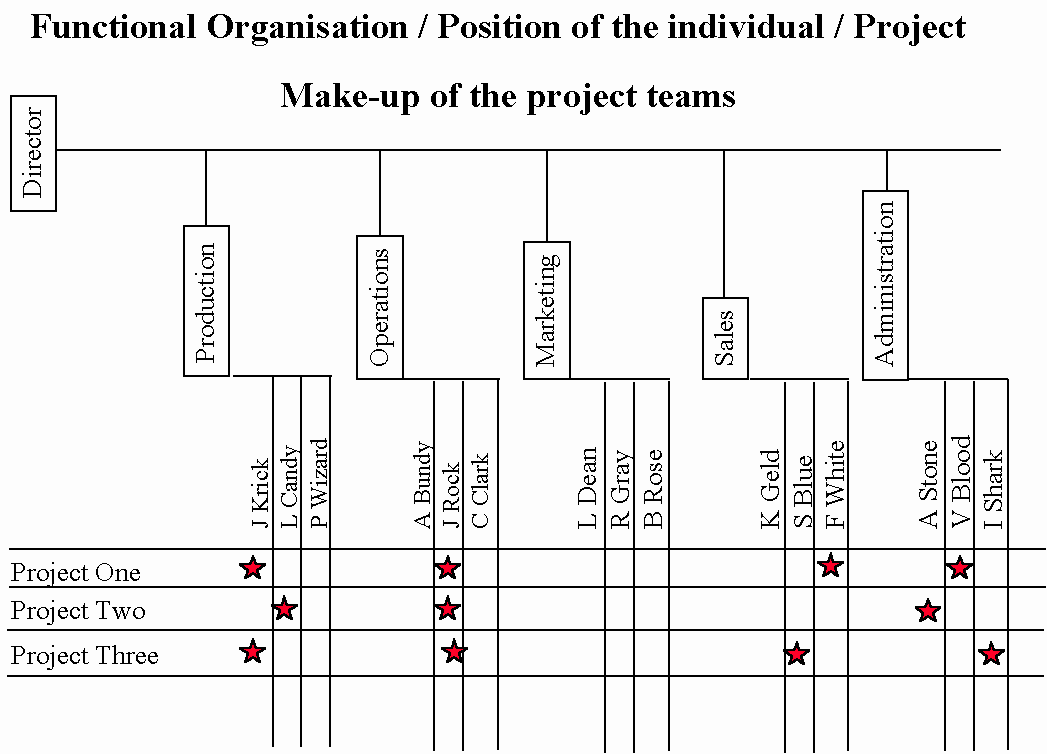

Fig. 2: Example of a project based management (Allan, 2004).

The project based management structure also faces a few limitations like any other structure. Limitations include the inability of a project manager to mobilize all the resources of a company as he has direct control of only what falls under his area of specialty. Employees and managers of such projects have been found to become slack towards the termination of projects due to the fear of losing their jobs once their projects have been completed (Kloppenborg, 2009).

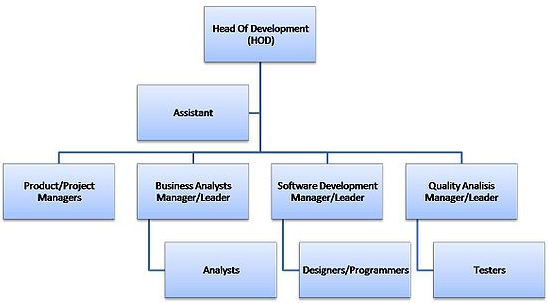

Due to the limitations of both the operational and functional management structures the matrix was developed. This structure combines both structures to form a hybrid structure. In this type of structure there are two types of managers, namely functional and operational who work together in the same system.

The functional managers are responsible for the distribution of resources in their specialty departments and the operational managers coordinate and manage the activities of their departments. The functional managers are also responsible for overseeing all the technical decisions that fall under their departments.

This method of management has its advantages such as: the project manager oversees all activities that fall under his department. He has all authority and power and thus this eliminates the wastage of time as a result of quarrels and conflicts among the top levels of an organization.

Secondly the manager is able to use organization resources in facilitating the execution of the intended goals and objectives of the company. Disadvantages include the conflicts and coercion between project managers and functional managers that is bound to occur in such a setting. This kind of relationship has an eventual effect on employee motivation as it often results in the demoralization of employees (Young, 2007).

Fig. 3: Matrix management structure (Burke, 1999)

There are various factors that are considered when choosing the management structure of a project. These include the type of activities to be carried out, their importance / order of priority, the human skill required, the amount of time needed and the resources that are required to accomplish the set targets.

Situations that require extensive cooperation and interaction of the functions of an organization require matrix types of management. However there is no optimum type of organization and the organization must strive to come up with solutions to its unique needs and situations.

For a project to be well managed a healthy culture of communication must be developed. Communication theories propose that the project manager should always be like the hub of a bicycle. This means that the project manager acts as a focal point through which suggestions and results are received from various stakeholders.

The project manager also acts as the supporting point for the communication wheel. It is therefore very important for project managers to assist in maintaining a good communicative culture within the organization (Burke, 1999).

Factors such as nature of businesses in which the organization is in, size of projects and type of projects will also have a strong impact on the type of management structure that an organization may use.

Formal management has an overall effect on the operations of an organization. The type of management that an organization has ultimately affects how its activities are carried out. Formal management is important in an organization as it serves as a foundation on which an organization’s goals and principles are guided. There are various guidelines that dictate the behavior and characters of managers in formal systems.

Managers in formal managements are required to have high integrity / moral standards, should be an effective communicators and listeners of others. Managers serve as the basis through which a formal management system is enforced. The project manager should also relate well with people.

He should have the ability to motivate and influence his workers positively. The project manager is also bestowed with the responsibility of ensuring that all aspects and stakeholders of a project work together for the common good of the organization. The manager is also responsible for setting time frames and ensuring that the project adheres to the set schedules.

This serves the purpose of ensuring that there is timely flow of an organization’s activities. Project managers are also required to make assessment of risks that could affect a project and try to manage the risks. In summary, project managers make up the backbone of any formal project management system and the performance of any project depends on the managers themselves (Burke, 1999).

There are three distinct characteristics that define a formal management structure; formality, the presence of groupings and the implementation of various systems. There exist rules and regulations that govern the relationships of the members of the organization. These rules also guide the reporting mechanisms of the members and the responsibilities / power which each member holds. These rules and regulations form the basis of all relationships and activities within the organization.

Formal organizations also group their members into teams and taskforces that are designed to suit various needs within the organization. For example accountants will usually be grouped together, designers with fellow designers and so forth. The groupings form departments and many departments form the organization.

However formal management has been said to be a very rigid mechanism by which an organization / project should be kept in check. This is because failure on the part of the managers would result in the total collapse of the organization. This is because managers are expected to provide guidance, direction and ensure that all members perform their duties.

Culture on the other hand is a better driver as it does not need to be enforced by anyone. Culture is self driven and once the members of an organization have adopted a desirable culture they will conduct themselves in accord to the culture without being supervised by a manager (Johnstone et al 2002).

Culture is also a better means of ensuring that a project is completed as it allows people to go out of the set boundaries and make innovations. Culture driven projects are better as they allow for unified and independent thinking at the same time. Whereas a formal management structure relies on the manager to make decisions a culture driven project accepts all decisions as long as they fall under the culture boundaries of the organization.

Formal management structures are slow and time consuming. This is because all major decisions and control is dependent on the managers. This leads to a very slow decision making process as the managers have to receive reports from members, deliberate on the reports and then give their recommendations. In cases where the manager is slow or is not presence this hinders the further development of the project (Young, 2007).

Many organizations that employ the formal type of management usually group their employees into departments. The departments are usually made up of people with common skills and areas of expertise. However such departmental setups hinder the exchange and sharing of ideas between people of different areas of expertise.

Due to the formal setup members from different departments lack a common factor that would enhance cooperation between the departments. This leads to poor coordination between the departments. In culture driven organizations, the members are unified by the common culture and this enhances the cooperation levels of the employees. Culture driven projects are therefore much more organized and have a better flow of activities as compared to formal projects (Kloppenborg, 2009).

Formal management of projects requires the mapping out and development of clear cut systems that will ensure the smooth flow of the project. These systems are essential in ensuring efficient execution of the project and its activities. Culture driven projects however do not need such a system so as to run smoothly. The culture itself forms a dynamic system through which all the activities are executed effectively.

Strategic management is a major component of formal management systems. It involves the science and methodologies of formulating cross functional parameters that enable an organization to achieve its objectives. Strategic management involves the development of missions and visions, mapping out of objectives and the making of critical decisions for the company (Allan, 2004).

Projects in formal management are stepping stones on which a firm uses to achieve its goals and objectives. The project development processes of a firm are driven by its strategic development goals and objectives. Examples of strategic elements include mission, objective, goals, programs and workable strategies.

Formal management is however beneficial as it promotes proper and sober decision making as compared to culture based management. This is because decision making and planning activities in a formal management are usually done after careful consideration and assessment. Culture based management is however prone to errors and misguided actions due inadequate consideration and thinking.

From the study it is evident that culture is an important aspect of any organization. Culture has been found to affect the behavioral attitudes of a company’s employees and the manner through which these attitudes are manifested. The strong impacts of culture have resulted in the need for managers to find ways to affect the culture of their employees and of the work places.

By influencing the culture of an organization the managers are therefore able to influence the way the organization operates. Culture is an unsaid norm which the members of an organization abide to (Jack et al, 2003).

Organizations implement different types of organization structures. The type of organization structure implemented depends on the size and project characteristics. The type of project management has an effect on the eventual delivery of the project. The study has shown that there is no perfect method of management.

Managers of projects are therefore required to assess and identify the appropriate structure for their specific conditions. Project management structures have a great effect on the quality and effectiveness of the organization’s activities (Allan, 2004).

The study has brought to light the importance of proper culture in an organization. Culture has been found to be a better determinant of employee behavior as compared to formal management. Formal management is dependent on the enforcement of those in authority / wield power.

Culture on the other hand is enforced by the members themselves as they are part and pertinent of the culture. Formal management has also been found to be excessively bureaucratic and procedural and thus its implementation is rather cumbersome and expensive. Culture has therefore been found as the most appropriate way of managing a project.

Allan, B., 2004. Project Management: tools and techniques for today’s ILS professional. London: Facet Publishing.

Ashish, D., 2010. Project management Module. Hull: University of Hull.

Burke, R., 1999. Project Management, Planning and control Techniques. Chichester: Wiley.

Jack, M. & Mentel, S., 2003. Project Management: A Managerial Approach. New Jersey: Wiley and Sons.

Johnston, R. Chambers, S. & Slack, N., 2002. Operations management . Essex: Pearson Publishers.

Kloppenborg, T., 2009. Project management A Contemporary. Chicago: Xavier University.

Young, T., 2007. The Handbook of Project Management, A practical Guide to Effective Policies and Procedures . Washington: Kogan Page publishers.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, April 18). Essay on Organizational Culture. https://ivypanda.com/essays/organizations-culture/

"Essay on Organizational Culture." IvyPanda , 18 Apr. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/organizations-culture/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Essay on Organizational Culture'. 18 April.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Essay on Organizational Culture." April 18, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/organizations-culture/.

1. IvyPanda . "Essay on Organizational Culture." April 18, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/organizations-culture/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Essay on Organizational Culture." April 18, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/organizations-culture/.

- Sociology. Evolution of Formal Organizations

- Preferred Organizational Structure: Functional Organizational Structure

- Importance of Communication in an Organization - Essay

- Management Skills in the 21st Century

- Challenges Inherent in Repositioning a Fast Food Chain

- Impact of Resolution Act of 1998 on Women-Workers

- Leadership and Management Strategies

- The Product and Service Development Process

Module 9: Culture and Diversity

Introduction to organizational culture, what you’ll learn to do: describe organizational culture, and explain how culture can be a competitive advantage.

Organizational culture is a term that describes the shared values and goals of an organization. When everyone in a corporation shares the same values and goals, it’s possible to create a culture of mutual respect, collaboration, and support. Companies that have a strong, supportive culture are more likely to attract highly qualified, loyal employees who understand and work toward the company’s best interests.

- Introduction to Organizational Culture. Authored by : Lisa Jo Rudy and Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

Privacy Policy

What Is Organizational Culture?

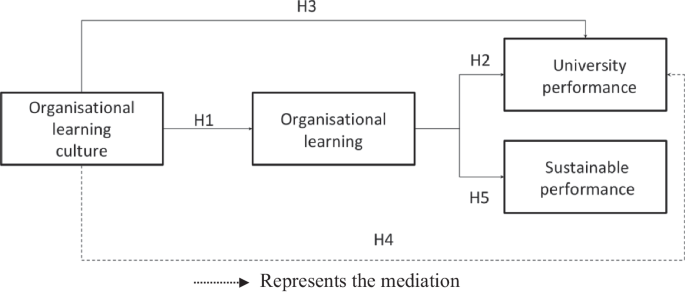

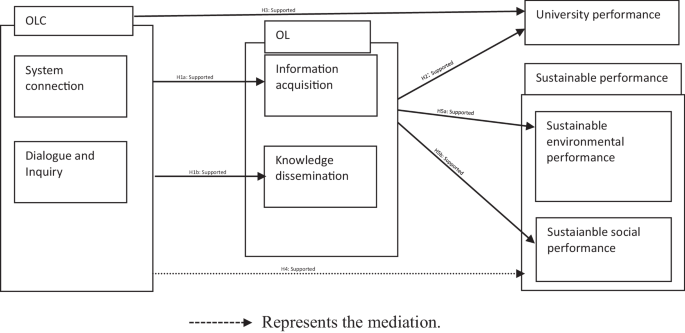

Companies have to create environments in which their employees are motivated to deliver excellent results each day in order to operate efficiently. Organizational culture is considered to be among the crucial components that help businesses operate because it helps create a unified vision of objectives and targets. This paper aims to define organizational culture, identify types of culture, examine approaches to communicating it, and research changes that can occur.

What is Organizational Culture?

Both within a society and in the environment of companies the concept of culture describes a complex structure of shared values that transpire to daily actions. The Cambridge Dictionary (n.d.) defines culture as “the way of life, especially the general customs and beliefs, of a particular group of people at a particular time” (para. 1). Therefore, this definition applies to companies as well because they employ people who interact and communicate within a particular timeframe and should have a unified understanding of the business’s objectives.

Definition of Organizational Culture

While the previous paragraph explains the general meaning of this concept, it is necessary to determine whether there are particular features applicable to this model in terms of private companies. Organizational culture has many definitions depending on a specific perspective from which an author regards this phenomenon. According to Naranjo-Valencia, Jiménez-Jiménez, and Sanz-Valle (2016), “organizational culture can be defined as the values, beliefs and hidden assumptions that the members of an organization have in common” (p. 30).

Moreover, the authors argue that innovation cannot be executed without proper culture. Pang (2017) states that the notion can be viewed as a specific approach a business takes towards its operations. Thus, organizations depend on culture because it defines the internal processes and interactions that occur in a particular environment.

Moreover, leaders who disregard this element of organizational structure can not benefit from enhanced efficiency and adequate cooperation, which will be discussed in detail in the next section of this paper. Groysberg, Lee, Price, and Cheng (2018) state that “strategy and culture are among the primary levers at top leaders’ disposal in their never-ending quest to maintain organizational viability and effectiveness” (para. 1). While the first component is a formalized reflection of goals and responsibilities, the second is an intangible representation of norms within a firm.

How is Organizational Culture Created and Communicated?

It is evident that organizational cultures a crucial component of any company. Executives can leverage this by developing an appropriate culture that inspires employees to work towards the set goals. Firstly, it is necessary to clearly define the mission of business in question and using that information as well as strategic plans to create culture. Additionally, leaders should pay specific attention to ensuring that newcomers correctly comprehend the existing culture, which can be done through training.

While executives are responsible for ensuring that a company has adequate culture, it should be noted that it defines the approaches that leaders can take towards their work and communication with followers. Both Forbes Communication Council (2017) and Pang (2017) emphasize the importance of communicating culture to employees through vision and mission statements. Other materials that managers can distribute are manuals and policy statements. However, these do not guarantee that all staff members comprehend the culture appropriately.

A better method of ensuring a proper understanding of culture is through the actions of executives. Pang (2017) states that “the culture of a business has a significant impact on its performance in the marketplace” (para. 1). However, without a commitment from top-level leaders employees would not be as eager to perform tasks well. Additionally, strategies that can encourage behaviors that correspond to a particular culture should be encouraged through rewards.

Personal Culture and Market Culture

The two primary types of culture in companies are personal and market, which imply a different approach to managing people and achieving strategic objectives. Personal culture refers to a structure in which individuals that work for an organization are considered to be more valuable than the business itself. From this perspective, a horizontal structure is the most suitable for establishments that apply this approach. The downside of this model is that it can organizations may face difficulties with sustaining and growing their operations. Additionally, if key people of a film decide to leave, such a company would be unable to proceed with its services and obtain revenue.

In this regard, market culture can be as considered a drastically different approach. In this model, competition and achievements are the primary objectives of work for people. It can be argued that this method allows organizations to avoid issues that can occur in the previously described personal culture model. Due to the fact that results are prioritized, the problem with this model is that the value of individuals is inevitably connected to the benefit that they bring for a company.

Adaptive Culture and Adhocracy Culture

The next two types of organizational culture are adaptive and adhocracy, which can be applied in industries that require constant innovation and adjustments of approaches. Adaptive culture implies that changes in how business functions are part of the daily operations, and thus they occur regularly and without difficulties. This is especially important for industries that are subjected to many altercations within their environment because employees can change their daily tasks efficiently.

Adhocracy is an entrepreneurial strategy that values an individual’s creativity and utilization of new approaches. The ability to create and develop new products, services, or management techniques are the crucial components of this strategy. Consecutively, this approach implies risk-taking and exploration of new abilities. It can be argued that this culture type is the most appropriate one for modern day information technology companies and startups.

Power Culture, Role Culture, and Hierarchy Culture

Power culture can be characterized as a type, which uses the leader’s authority. The power that leads to formal leadership in such company is held in by a few people (Driskill, 2019). They are capable of making decisions that would affect each component of such a company. Similarly to market culture, achievements are the focus of work when evaluating employees’ contributions. The issue with this approach is highlighted by Driskill (2019) who states that while this method can help make decisions quickly and adjust operations following market demands. However, the issue is that the risk of such an environment becoming toxic is high.

Role culture is highly regulated and each in such company knows his or her responsibilities and tasks. Major decisions in such structure are made by people in managerial positions (Driskill, 2019). While the environment of such companies implies that all staff members should perform their tasks well because they are fully aware of what should be done, the process of decision-making is usually long due to bureaucracy.

Thus, such organizations are unlikely to make strategic decisions that imply risk and struggle with adopting new approaches. Next, as the name of this approach suggests, hierarchy culture focuses on formal interactions within an organization. The structure of the company is the primary element that coordinates the work relationships within this environment. Additionally, the leaders prioritize long-term operations and thus, the planning for execution of each task is thorough. Such settings are highly predictable in terms of decisions that such companies make.

Task Culture and Clan Culture

Task culture is oriented towards creating an environment in which projects are prioritized. Thus, the primary objective is to create an ecosystem in which tasks are done through proper planning and preparation. Driskill (2019) states that this method is facilitated through the creation of teams that are responsible for a particular project. Expert power is the most critical element for leaders in this case. Depending on a specific outline, different members of the organization can take leadership. Based on the information it can be concluded that this approach focusses on results as well.

Clan culture is a structure in that values internal relationships and mentoring of newcomers. Driskill (2019) compares this structure to tribes, which implies that such organizations function using informal connections. In addition, it means that the competition prevalent in market culture is mitigated. Arguably, this can lead to a worse completion of tasks, although Driskill (2019) emphasizes that loyalty that is the basis of this approach ensures proper motivation for employees.

Other issues connected to this model are inadequate diversity because the process of hiring new members to such companies can be biased. Both of these approaches focus on the commitment of staff members towards achieving goals that the company’s leaders set. However, the distinct difference is that in task-oriented environments the knowledge and skills of individuals have a crucial role. Clan culture, on the other hand, emphasizes the process of mentoring new members, which can lead to a disregard for their actual capabilities.

How and Why Does Organizational Culture Change?

Inevitably, due to changes in the industry or other alterations such as political or economic issues, organizations have to adapt their approaches to operations to be more efficient. In this case, changing the culture is necessary because, as was described before, each model is suitable for a particular strategy and target in regards to employee performance. Groysberg et al. (2018) state that “the best leaders we have observed are fully aware of the multiple cultures within which they are embedded, can sense when change is required, and can deftly influence the process” (para. 5).

Alternatively, culture can evolve as the leaders, and other members of organizations gain new knowledge and identify what approaches lead to successful operations and an increase in revenue. The following paragraphs describe the process of culture change and components that contribute to it.

Top Management Vision

The first step is to critically examine the existing culture and deciding which model would correspond to the current conditions better. The C-level executives are responsible for ensuring that the existing culture corresponds to the type of tasks and goals that a company wants to achieve because this element directly affects the outcomes of work. Groysberg et al. (2018) emphasize the connection between culture and strategy; therefore, the first step in the process of changing the company’s approaches is to develop new objectives by creating and stating new vision and mission.

Top Management Commitment

Secondly, the executives of an organization should display readiness for the changes, which should transpire to its employees because they can witness the application of new values. This can be achieved through actions so that staff members could observe the changes and become accustomed to the new culture. This would ensure that the leaders of the company respect the culture and are ready to perform their daily tasks in regards to it.

Model Culture Change at the Highest Level

Similarly to the previous step, this component requires particular attention from managers of a firm. People should showcase the values that the company aims to nurture within its internal environment at managerial positions, which would communicate the change correctly. As was previously discussed communication of culture through actions is the best method. In this regard, the role of change agents who facilitate the adoption of new approaches to operations is crucial.

Modify the Organization to Support Organizational Change

The fourth step requires a critical examination of the current components that enable operations and identifying which of those should be changed to suit the new culture better. Particular types of organizational cultures imply a specific structure of processes and interactions within a business. For instance, adhocracy requires flexibility while role culture is based on formal relationships. The leaders should change the existing elements for the new model to be adopted.

Select newcomers and terminate deviants

Next, a strategy for hiring and terminating employees should be in place. In some cases, particular individuals are not able to fit in with the new approach.

Asli (2016) states that this step is connected to human resource functions and determines whether newly hired individuals can adapt to the selected culture model. The process of firing individuals should be tailored towards the new values as well. However, culture change helps performance results, thought enabling better performance and efficiency; thus some individuals have to be terminated.

An executive has to create approaches for mitigating risks of the new model for developing ethical and legal sensitivity. Asli (2016) states that in most cases, a severe change in a company’s culture would result in fear of uncertainty and insecurity for the staff members. This should be mitigated through ethical and legal considerations. Asli (2016) recommends applying the method of periodic evaluation for determining if this strategy helps minimize the conflict between new culture and employees. This can help ensure a smooth transition towards a new model.

Organizational Subcultures

Subcultures may exist in any company regardless of the model that it applies. Faller, de Kinderen, Constantinidis (2016) conducted a study by examining several companies in Europe and identifying how subcultures affect productivity and achievement of results. The authors concluded that both differences and similarities in the subcultures of a company’s department could lead to a decrease in the efficiency of enterprise architecture.

This can be due to difficulties in communicating information between different structural elements that are guided by varied organizational environments. For instance, issues may arise if departments prefer to work in isolation from others, or if one of the teams uses this approach while others interact. Therefore, identifying them and ensuring that they can communicate with each other is crucial.

Overall, a thriving organizational culture has several benefits for companies. Firstly, leaders can enhance their commitment towards achieving their strategic goals through proper culture. Secondly, every company develops a particular environment, and improper models can lead to reduced motivation and an inability to perform tasks efficiently. Due to this reason, executives can leverage culture to ensure better work efficiency. Finally, this element shapes the behaviors and interactions within an organization, and employees can benefit from this by assuming particular roles and fulfilling tasks.

Asli, G. (2016). Organizational change management strategies in modern business. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Culture. (n.d.). In Cambridge Dictionary. Web.

Driskill, G. W. (2019). Organizational culture in action: A cultural analysis workbook (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Faller, H., de Kinderen, S., Constantinidis, K. (2016). Organizational subcultures and enterprise architecture effectiveness: Findings from a case study at a European airport company. 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS) , Koloa, HI, 2016, pp. 4586-4595. Web.

Forbes Communication Council. (2017). Telling your company’s culture story . Forbes . Web.

Groysberg, B., Lee, J., Price, J., & Cheng, J. Y. (2018). The leader’s guide to corporate culture . Web.

Naranjo-Valencia, J., Jiménez-Jiménez, D., & Sanz-Valle, R. (2016). Studying the links between organizational culture, innovation, and performance in Spanish companies. Revista Latinoamericana De Psicología , 48 (1), 30-41. Web.

Pang, K. (2017). Are you nurturing a positive company culture? Communication is the key . Web.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, January 8). What Is Organizational Culture? https://studycorgi.com/what-is-organizational-culture/

"What Is Organizational Culture?" StudyCorgi , 8 Jan. 2021, studycorgi.com/what-is-organizational-culture/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) 'What Is Organizational Culture'. 8 January.

1. StudyCorgi . "What Is Organizational Culture?" January 8, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/what-is-organizational-culture/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "What Is Organizational Culture?" January 8, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/what-is-organizational-culture/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "What Is Organizational Culture?" January 8, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/what-is-organizational-culture/.

This paper, “What Is Organizational Culture?”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: January 8, 2021 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Organizational Culture

Armstrong (1999) said that the organizational culture is the pattern of values, norms, beliefs, attitudes and assumptions that may not have been articulated but shape the ways in which people behave and things get done.

Organizational Culture: Introduction, Components, Functions and Barriers

- Introduction to Organizational Culture

- Organizational Culture ― An Analytical Overview

- Beginning of Organizational Culture

- Components of Organizational Culture

- Functions of Organizational Culture

- Adaptation of Organizational Culture by the Employees

- Organizational Culture as a Barrier

- Organizational Cultures in the 21st Century

- Sustaining Basics and Developing Variable Aspects of Organizational Culture- Conclusion

# 1. Introduction to Organizational Culture:

The idea of viewing organizations as cultures—where there is a system of shared meaning among members—is a relatively recent phenomenon. Until the mid-1980s, organizations were, for most part, simply thought of as rational means by which to coordinate and control a group of people, which have vertical levels, departments, authority relationships, and so forth. But organizations are more than that.

They have personalities too, just like individuals which can be rigid or flexible, unfriendly or supportive, innovative or conservative. For example, general electric offices and people are different from the offices and people at general mills. Harvard and MIT are in the same business of education—separated only by the width of the Charles River in Massachusetts, USA, but each has a unique feeling and character beyond its structural characteristics. Organization theorists now acknowledge this by recognizing the important role that culture plays in the lives of organizational members.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Interestingly, though, the origin of organizational culture as an independent variable affecting an employee’s attitude and behaviour can be traced back more than 50 years to the notion of institutionalization. When an organization becomes institutionalized, it takes on a life of its own, apart from its founders and any of its members. For example, Ross Perot created electronic data systems (EDS) in the early 1960s and left in 1987 to establish a new company, Perot Systems.

EDS has, however, continued to thrive despite the departure of its founder. Sony, Eastman, Kodak, Gillette, McDonald’s, and Disney are a few other examples of organizations that have existed beyond lives of their founders or any one member and have developed their own self-initiated organizational cultures over the period of time. Additionally, when an organization becomes institutionalized, it becomes valued for itself and not merely for the goods and services it produces. It acquires corporate immortality. If its goods are no longer relevant, it does not go out of business. Rather it redefines itself.

When the demand for Timex watches declined, the Timex Corporation merely redirected itself into consumer electronics business-making, in addition to watches, clocks, computers, and health care products such as digital thermometers and blood pressure testing devices. Timex Corp took on an existence that went beyond its original mission to manufacture low cost mechanical watches. This sense of redefining itself became a part of Timex’s organizational culture.

Hence, institutionalization operates to produce common understandings among members about what is appropriate and, fundamentally, meaningful behaviour. So when an organization takes on institutional permanence, acceptable modes of behaviour, it becomes largely self-evident to its members. This is almost the same thing that organizational culture does.

Hence; an understanding of what makes up an organization’s culture, and how it is created, sustained, and learned, further enhances the manager’s ability to explain and predict the behaviour of people at work.

# 2. Organizational Culture ― An Analytical Overview:

Armstrong (1999) said that the organizational culture is the pattern of values, norms, beliefs, attitudes and assumptions that may not have been articulated but shape the ways in which people behave and things get done. Values refer to what is believed to be important about how people and the organizations behave. Norms are unwritten rules of behaviour.

This definition emphasizes that organizational culture is concerned with abstractions such as values and norms which pervade the whole or part of an organization. There seems to be wide agreement that organizational culture refers to a system of shared meaning held by members that distinguishes the organization from other organizations. This system of shared meaning is a set of key characteristics that the organization values.

O’Reilly III, Chatman and Caldwell (1991) suggests that there are seven primary characteristics that, in aggregate, capture the essence of an organization’s culture:

i. Innovation and Risk-Taking:

The degree to which employees are encouraged to be innovative and take risks.

ii. Attention to Detail:

The degree to which employees are expected to exhibit precision, analysis, and attention to detail.

iii. Outcome Orientation:

The degree to which management focuses on results or outcomes rather than on the techniques and processes used to achieve those outcomes.

iv. People Orientation:

The degree to which management decisions take into consideration the effect of outcomes on people within the organization.

v. Team Orientation:

The degree to which the work activities are organized around teams rather than individuals.

vi. Aggressiveness:

The degree to which people are aggressive and competitive rather than easy-going.

vii. Stability:

The degree to which the organizational activities emphasize maintaining the status quo in contrast to growth.

Each of these characteristics consists on a continuum from low to high. Appraising the organization on these seven characteristics, then, gives a composite picture of the organization’s culture. This picture becomes the basis for feelings of shared understanding that members have about the organization, how things are done in it, and the way members are supposed to behave.

Organizational culture is, therefore concerned with how employees perceive the characteristics of organization’s culture, not with whether or not they like them. Organizational culture represents a common perception held by the organization’s members. It is widely accepted that individuals with different backgrounds or at different levels in the organization will tend to describe the organization’s culture in similar terms.

It is this ‘shared meaning’ aspect of organizational culture that makes it such a potent device for guiding and shaping behaviour. That is what determines, e.g., Microsoft’s culture which values aggressiveness and risk-taking. This gives the managers the insight and information to better understand the behaviour of Microsoft’s executives and employees.

It can be concluded that organizational culture provides stability to an organization. Furthermore, every organization has a culture and, depending on its strength, it can have a significant influence on the attitudes and behaviours of organization’s members. In order to successfully understand the culture of an organization, it is important first of all to understand how culture begins in an organization.

# 3. Beginning of Organizational Culture:

An organization’s culture does not pop out of thin air. Once established, it rarely fades away. An organization’s current customs, traditions, and general ways of doing things are largely due to what it has done before and the degree of success it has had with those endeavours. This leads to the ultimate source of organization’s culture and its founders.

The founders of an organization traditionally have a major impact on that organization’s early culture. They have a vision of what organization should be. They are unconstrained by the previous customs and ideologies. The small size that typically characterizes new organizations further facilitates the: founder’s imposition of their vision on all organizational members.

The process of culture creation occurs in three ways ― First, founders only hire and keep employees who think and feel the way they do. Second, they indoctrinate and socialize these employees to their way of thinking and feeling. And finally, the founder’s own behaviour acts as a role model that encourages employees to identify with them and thereby internalize their beliefs, values and assumptions. When the organization succeeds, the founder’s vision is seen as a primary determinant of that success. At this point, the founder’s entire personality becomes embedded in the culture of the organization.

To substantiate this, citing the example of Sony will be quite appropriate as Sony can truly be viewed as the Essence of Akio Morita. Akio Morita, Sony Corporation’s co-founder had such a tremendous influence on the company’s culture that people often referred to him as Mr. Sony.

Morita was described as a passionate lover of music and art, a workaholic, a great socialiser, a brilliant observer of people’s behaviour, and a man with an un-bounding energy, a relentless drive, and a determined focus. Morita applied these qualities in pursuing his vision of creating a brand name for products that appealed to people worldwide.

He chose a short, catchy name for his company so people everywhere could easily pronounce and remember it. Morita began his globalization strategy in the United States, where he moved his family so that he could study American culture and increase Sony’s chance of success. Today, Sony is recognized throughout the world as a leading brand name.

Citing another recent example, Southwest Airlines can be aptly described as Herbert Kelleher s passion. The actions of Herbert Kelleher, Southwest Airlines’ Chief Executive, had a strong influence on the company’s casual, fun-loving culture. He stars in the company’s orientation film, where new employees see their leader singing and dancing. Kelleher models the light-hearted behaviour he expects of his employees so they, in turn, know that it is okay as a part of providing exceptional customer service, to have fun with the airline’s passengers.

Similarly, the culture at Hyundai the giant Korean Conglomerate is largely a reflection of its founder Chung Ju Yung. Hyundai’s fierce, competitive style and its disciplined, authoritarian nature are the same characteristics used to describe Chung.

Other contemporary examples of founders who have had an immeasurable impact on their organization’s culture include ― Bill Gates at Microsoft, David Packard at Hewlett-Packard, Fred Smith at Federal Express, Mary Kay at Mary Kay Cosmetics, and Richard Branson at the Virgin Group.

# 4. Components of Organizational Culture:

The culture of an organization represents a complex pattern of shared values, norms and artefacts which are characteristics of the organization. Hence, organizational culture can be said to comprise of three different components viz., values, norms and artefacts.

These terms are further described below:

Values are the beliefs in what is good for the organization and what should or ought, to happen. The ‘value set’ of an organization may only be recognized at top level, or it may be shared throughout the business, in which case the organization could be described as value-driven. The stronger the values, the more they will influence behaviour. This does not depend upon their having been articulated.

Implicit values that are deeply embedded in the culture of the organization and are reinforced by the behaviour of the management can be highly influential, while espoused values that are idealistic and are not expressed in the managerial behaviour may have little or no effect. Some of the most typical areas in which values can be expressed, implicitly, or explicitly are: performance, competence, competitiveness and teamwork.

Norms are the unwritten rules of behaviour, the ‘rules of the game’ that provide informal guidelines on how to behave. Norms tell people what they are supposed to be doing, saying, believing and even wearing. They are never expressed in writing—if they were, they would be policies or procedures.

They are passed on by the word of mouth or behaviour and can be enforced by the reactions of the people if they are violated. They can exert very powerful influence on the behaviour because of these reactions—people are controlled by the way others react to them. Norms can be very well illustrated by the prevailing work ethics, e.g., ‘work hard, play hard’, ‘come in early, stay late’, look busy at all times’ or ‘look relaxed at all times’.

3. Artefacts:

Artefacts are the visible and tangible aspects of an organization that people hear, say or feel. Artefacts can include such things as the working environment, the tone and language used in letters and memoranda, the manner in which people address each other at meetings or over the telephone, the welcome (or lack of welcome) given to the visitors and the way in which receptionists deal with outside calls. Artefacts can be very revealing.

# 5. Functions of Organizational Culture:

After having described what an organizational culture is, along with its origin and components, it will be appropriate to probe into the wide array of meaningful functions performed by the organizational culture for the organization.

Staw and Cummings (1996) described that organizational culture performs a number of functions within an organization. First, it has a boundary-defining role, i.e. it creates distinctions between one organization and others. Second, it conveys a sense of identity for organizational members. Third, organizational culture facilitates the generation of commitment to something larger than one individual’s self-interest. Fourth, it enhances, social system stability.

Organizational culture is therefore, the social glue that helps hold the organization together by providing appropriate standards of what employees should say and do. Finally, organizational culture serves as a sense-making and control mechanism that guides and shapes the attitudes and behaviour of the employees. The role of organizational culture in influencing employees’ behaviour appears to be increasingly important in today’s work-place.

As organizations have widened the spans of control, flattened structures, introduced teams, reduced formalization, and empowered employees, the shared meaning provided by a strong culture ensures that everyone is pointed in the same direction. For instance, the employees at Disney theme parks appear to be almost universally attractive, clean and wholesome looking, with bright, smiles. That is what the organizational culture at Disney imbibes and conveys.

The company selects employees who will maintain that image. And once on the job, a strong organizational culture, supported by the formal rules and regulations, ensures that Disney-theme park employees will act in a relatively uniform and predictable way. Also, to illustrate the notion of shared meaning, ‘Yahoo! Incorporation.’ presents a good example.

The shared meaning provided by Yahoo Inc.’s strong organizational culture is stated in the company’s motto—’Do what’s crazy, but not stupid.’ The motto guides employees as they develop entertaining programmes and services that grab the attention of today’s internet users. Employee creativity is the key to keeping ‘Yahoo!’ the leading search engine on the internet. ‘Yahoo!’ hires young net enthusiastic who thrive in an informal setting where there are few rules and regulations to stifle the creative process.

# 6. Adaptation of Organizational Culture by the Employees:

How Employees Adopt Culture:

Once an organizational culture is in place, there are practices within the organization that act to maintain it by giving employees a set of similar. Culture is transmitted to employees in a number of forms, the most potent being stories, rituals, material symbols and language.

1. Stories:

During the days when Henry Ford II was the chairman of the Ford Motor Co., one would have been hard pressed to find a manager who had not heard the story about Mr. Ford reminding his executives, when they got too arrogant, that “it’s my name that is on the building.” The message was clear- Henry Ford II ran the company.

Stories such as that circulate through many organizations. They typically contain a narrative of events about the organization’s founders, rule-breaking, rags-to-riches successes, reductions in the workforce, relocation of employees, reactions to past mistakes and organizational coping. For most of the part, these stories develop spontaneously. But some organizations actually try to manage this element of organizational culture’s learning.

For instance, Krispy Kreme, a large doughnut maker out of North Carolina, USA has a full time ‘Minister of Culture’ whose primary responsibility is to tape interviews with customers and employees. The stories these people tell are then put into company’s video magazine that describes Krispy Kreme’s history and values. These stories anchor the present in the past and provide explanations and legitimacy for current practices.

2. Rituals:

Rituals are repetitive sequences of activities that express and reinforce the key values of the organization; which goals are most important, and which people are important and which are expendable. One of the best known examples for organizational rituals is Mary Kay Cosmetics’ Annual Award Meeting. Looking like a cross between a circus and a Miss America pageant, the meeting takes place over a couple of days in a large auditorium, on a stage in front of a large, cheering audience, with all the participants dressed in glamorous evening clothes. Sales women are rewarded with an array of flashy gifts—gold and diamond pins, fur stoles, pink Cadillacs—based on the success in achieving sales quota.

This ‘show’ acts as a motivator by publicly recognizing outstanding sales performance. In addition, this ritual aspect reinforces Mary Kay’s personal determination and optimism, which enabled her to overcome personal hardships, establish her own company, and achieve material success. It conveys to her sales people that reaching their sales quota is important and that through hard work and encouragement they too can achieve success.

3. Material Symbols:

The headquarters of Alcoa, world’s leading producer of primary aluminum, fabricated aluminum, and alumina, does not look like a typical head office operation. It has few individual offices. It is essentially made up of cubicles, common areas, and meeting rooms. This informal corporate headquarters convey to the employees that Alcoa values openness, equality, creativity and flexibility.

Some corporations provide their top executives with chauffeur-driven limousines and, when they travel by air, unlimited use of the corporate jet. Others may not get to ride in limousines or private jets but they might still get a car and air transportation paid for by the company. Only the car is Chevrolet (with no driver) and the jet seat is in the economy section of a commercial airliner.

The layouts of the corporate headquarters, the types of automobiles top executives are given, and the presence or absence of corporate aircraft, are a few examples of material symbols. Others include size of offices,’ the elegance of furnishings, executive perks and dress attires. These material symbols convey to employees who is important, the degree of egalitarianism desired by the top management, and the kinds of behaviour (for example, Risk-taking, conservative, authoritarian, participative, individualistic, social) that are appropriate.

4. Language:

Many organizations and units within the organizations use language as a way to identify its organizational members. By learning this language, members attest to their acceptance of the culture and, in doing so help to preserve it. For example, employees at Tattoo, a marketing services agency in San Francisco, USA use special words to convey the organization’s unique culture.

They call the Tattoo’s three floors of office space the ‘hive’ because it buzzes with activity as employees move between the floors to work on different client projects. They refer to themselves as ‘Tattools’, because the company discourages the formal job titles and other symbols of formal authority.

Unlike most marketing firms that use market research studies and focus groups for developing brand campaigns, Tattoo uses an intuitive approach it calls ‘living the brand’. Employees call client presentations ‘collages’, a blending of music and visuals intended to show the sensory and emotional aspects of brand.

Hence, organizations, over a period of time, often develop unique terms to describe equipment, offices, key personnel, suppliers, customers, or products that relate to their business. New employees are frequently overwhelmed with acronyms and jargon that, after 6 months on the job, have become fully a part of their language. Once, assimilated, this terminology acts as a common denominator that unites members of a given organizational culture.

# 7. Organizational Culture as a Barrier:

Every coin has two sides and so has organizational culture. On the one hand, organizational culture plays a very integral part in the organizations’ overall conduct. Many of its functions are valuable to both the organizations and the employees. Organizational culture enhances organizational commitment and increases the consistency of employee behaviour.

These are clearly benefits to organizations. From an employee’s standpoint, organizational culture is valuable because it reduces ambiguity. It tells employees how the things are done and what is important. On the other hand, organizational culture can also pose to become a barrier to organizational growth and development.

This fact is well-depicted in some potentially dysfunctional aspects of organizational culture and its effects on the organization, especially a strong one, on an organization’s effectiveness:

1. A Barrier to Change:

Culture is a liability when shared values are not in agreement with those that will further the organization’s effectiveness. This is most likely to occur as an organization’s environment is dynamic. When an organization is undergoing rapid change, organization’s entrenched culture may no longer be appropriate.

So consistency of behaviour is an asset to an organization when it faces a stable environment. It may, however, burden the organization and make it difficult to respond to changes in the environment. For instance, JC Penney and Sears once ruled the USA’s retail department store market.

Their executives considered their markets immune to competition. Beginning in the mid-1970s, Wal-Mart did a pretty effective job of humbling Penney’s and Sear’s managements. General Motors’ executives, safe and cloistered in their Detroit headquarters in USA, ignored the aggressive efforts by the Japanese auto firms to penetrate its markets. The result is history. General Motors market share has been in a free fall for three decades.

Toyota, once one of those aggressive Japanese firms that was successfully stealing market share from General Motors, itself became a casualty of its own success. During the first half of 1990s, having been slow to respond to the recreational vehicle market and stuck with a cumbersome vehicle development process, Toyota experienced a serious loss in market share and profit margins.

2. A Barrier to Diversity:

Hiring new employees who, because of race, gender, disability, or other differences, are not like majority of the organization’s members, creates a paradox. Management wants new employees to accept the organization’s core cultural values. Otherwise, these employees are unlikely to fit in or be accepted. But at the same time, management wants to openly acknowledge and demonstrate support for the differences that these employees bring to the workplace.

Strong cultures put considerable pressure on employees to conform. They limit the range of values and styles that are acceptable. In some instances, such as the widely publicized Texaco case (which was settled on behalf of 14000 employees for $ 176 million) in which senior managers made disparaging remarks about minorities; a strong culture that condones prejudice can even undermine formal corporate diversity policies.

Organizations seek out and hire diverse individuals because of the alternative strengths these people bring to the workplace. Yet, diverse behaviours and strengths are likely to diminish in strong cultures as people attempt to fit in. Strong organizational cultures can, therefore, be liabilities when they effectively eliminate those unique strengths that people of different backgrounds bring to the organization. Moreover, strong organizational cultures can also be liabilities when they support institutional bias or become insensitive to people who are different.

3. A Barrier to Acquisitions and Mergers:

Historically, the key factors that management looked at in making acquisitions or merger decisions were related to financial advantages or product synergy, but, in recent years, organizational cultural compatibility has become the primary concern. While a favourable financial statement or product line may be the initial attraction of an acquisition candidate, whether the acquisition actually works seems to have more to do with how well the two organizations’ cultures match up.

A number of acquisitions consummated in the 1990s already have failed. And primary cause is conflicting organizational cultures. For instance, AT and T’s 1991 acquisition of NCR was a disaster. AT and T’s unionized employees objected to working in the same building as NCR’s non-union staff. Meanwhile, NCR’s conservative, centralized culture did not take kindly to AT and T’s insistence on calling supervisors ‘coaches’ and removing executive’s office doors. By the time AT and T finally sold NCR, the failure of the deal had cost AT and T more than $ 3 billion.

Similarly, Word-Perfect Corp. bought Novell Inc. in 1994 to give it a viable word-processing product to compete against Microsoft. But the employees and the managers from the two organizations could never see eye to eye on important issues. When Word Perfect was sold to Corel Corp. in 1996, Novell got $ 1 billion less than it had paid just two years earlier. Hence, it is clearly evident from the above real-life corporate examples that rigid organizational cultures can pose to be significant barriers to the organization’s future growth and development.

# 8. Organizational Cultures in the 21st Century:

Any group of people who have worked together for some time, any organization of long standing, indeed, any state or national body over a period of time develops a philosophy and a series of traditions. These are unique and they fully define the organization, setting it aside for better or worse from similar organizations.

To cite an example from the fast-moving, ever changing information technology world, this article dwells into Hewlett-Packard which is a leading giant in the computer and information technology business. At Hewlett-Packard, whole of its organizational culture goes under the general heading of the ‘H-P Way’.

In general terms, ‘H-P Way’ is the policies and actions that flow from the belief that men and women want to do a good job, a creative job, and that if they are provided with the proper environment, they will do so. But that’s only a part of it. Closely coupled with this is the H-P tradition of treating each individual with consideration and respect and recognizing personal achievements.

This really catches the essence of the ‘H-P Way’. It cannot be described in number and statistics. Basically, it is the spirit, a point of view. It is a feeling that everyone is the part of a team, and that team is Hewlett- Packard. It exists because people have seen that it works, and they believe in it and support it. The belief is that this feeling makes Hewlett-Packard what it is, and that it is worth perpetuating. And this belief forms the crux of Organizational Culture at Hewlett-Packard.

This example provides some insight into the organizational culture of Hewlett-Packard. In many respects, its culture is unique in itself and is very different from that of IBM or Apple Computers or Texas Instruments. In fact, two organizations might be in essentially the same business, be located in the same geographic area, have similar form of organizational structure, and yet be, somehow, very different as places to work.

This difference can be credited, to a large extent, to different organizational cultures unique to an organization itself. This goes on to substantiate the fact that a strong organizational culture can affect employees’ behaviours and commitment to the organization in a significant manner.

# 9. Sustaining Basics and Developing Variable Aspects of Organizational Culture- Conclusion:

In the end, it would be wise to acknowledge the fact that in order to make organizational cultures work for the organization, we have to sustain some of the basic aspects of the organizational culture as they provide stability to the organization, while developing certain variable aspects of organizational cultures in order to equip the organization to survive in a dynamic environment of today’s modern day corporate world.

An organization’s culture is largely made up of relatively stable characteristics. It develops over many years and is rooted in deeply held values to which employees are strongly committed. In addition, they are a number of forces continually operating to maintain a given culture.

These would include written statements about the organization’s mission and philosophy, the design of the physical space and buildings, the dominant leadership style, hiring criteria, entrenched rituals, popular stories about key people and events, past promotion practices, the organization’s historic performance evaluation criteria, and the organization’s formal structure.

Selection and promotion policies are particularly important devices that work for sustaining the basics of organizational culture. Employees choose an organization because they perceive their own values to be a good fit with the organization. They become comfortable with that fit.

Hence, one of the most important managerial implications of organizational culture relates to the selection decisions. Hiring individuals whose values do not align with those of the organization is likely to lead to employees who lack motivation and commitment and who are dissatisfied with their jobs and the organizations.

Employees form an overall subjective perception of the organization based on such factors as degree of risk tolerance, team emphasis, and support of people. This overall perception becomes, in effect, the organization’s culture or personality. These favourable or unfavourable perceptions then affect employee performance and satisfaction, with impact being greater for stronger cultures, just as people’s personalities tend to be stable over time, so too strong cultures do.

This makes strong cultures difficult for managers to change. When a culture becomes mismatched to its environment, management would want to change it. But changing an organization’s culture is a long and difficult process. The result, at least in the short-term, is that managers should treat their organization’s culture as relatively fixed. Robbins (2003) says that culture is largely stable in nature but that does not mean it cannot be changed.

In the unusual case when an organization confronts a survival-threatening crisis— a crisis that is universally acknowledged as a {rue life-or-death situation— members of the organization will be responsive to efforts at cultural change. Hence, changing an organization’s culture is extremely difficult, but cultures can be changed.

Roth (1998) suggests that cultural change is most likely to take place when most or all of the following conditions exists:

First condition is of a dramatic crisis. This is the shock that undermines the status quo and calls into question the relevance of the current culture. Examples of this crisis might be a surprising financial setback, the loss of a major client or customer base, or a dramatic technological breakthrough by a competitor.

Second condition is of turnover in leadership. This happens basically when the new top leadership, which can provide an alternative set of key values, may be perceived as more capable of responding to the crisis.

Third is the case of young and small organizations. The younger the organization the less entrenched its culture will be. Similarly, it is easier for the management to communicate its new values when the organization is small and young.

And finally, there is the case of a weak culture. The more widely held the culture and the higher the agreement among members on its values, the more difficult it will be to change. Conversely, weak cultures are more amendable to change than strong ones.

If the preceding conditions exist, the following actions may lead to change- new stories and rituals need to be set in place by top management; employees should be selected and promoted who espouse these new values and the reward system needs to be changed to support the new values. Under the best of conditions, these actions would not result in an immediate or dramatic shift in the prevailing organizational culture. This is because cultural change is a lengthy process—measured in years rather than in months. But cultures can be changed.

Related Articles:

- Relation between Performance and Organisation Culture

- Difference between Organisation Climate and Organisation Culture

- Business and Culture: Relationship

- Organisational Culture: Definitions, Features, Significance, Elements, Types

We use cookies

Privacy overview.

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

How Does Leadership Influence Organizational Culture?

- 02 Mar 2023

Organizational culture is a powerful driver of success. Yet it’s difficult to quantify and track, making it an intimidating but necessary challenge leaders must face.

How can you, as an organizational leader, shape a strong culture? Before exploring how, here’s a primer on organizational culture and why it matters.

What Is Organizational Culture, and Why Is It Important?

Organizational culture is the collection of values, beliefs, assumptions, and norms that guide activity and mindset in an organization.

Culture impacts every facet of a business, including:

- The way employees speak to each other

- The norms surrounding work-life balance

- The implied expectations when challenges arise

- How each employee feels about their work

- The permissibility of making mistakes

- How each team and department collaborate

Having a strong culture pays off financially: It can impact employees’ motivation, which, in turn, influences their work’s quality and efficiency, ability to reach goals, and retention rates. Having a culture that fosters innovation can also pay off in the form of new product ideas and creative solutions to problems .

It’s not possible to opt out of having an organizational culture—if you don’t put effort into crafting it, a negative one can emerge. If you’re an organizational leader —especially at a large company—you can’t directly speak to every employee, so you must influence culture from a high level.

Here are three ways you can influence organizational culture, the importance of effective communication, and how to build your skills.

Access your free e-book today.

How Do Leaders Influence Organizational Culture?

1. ensuring alignment on mission, purpose, and vision.

One way you can influence your organization’s culture is by ensuring everyone’s aligned on its mission, purpose, and vision.

Think of this communication as laying the foundation for culture. What customer need does your company fulfill? How does it make a positive impact? What’s its vision for the future, and what strategies are in place for getting there?