Develop your skills as an historian

Top tips to develop your skills.

1) Read books & journal articles

Read, think, write and talk about whatever you find interesting about the past.

Work out what you think about what you read. For instance, ask yourself: what is the author’s argument? Is it convincing? Why (or why not)? What evidence does the author use to make their argument? What is missing from their approach to the past? What else do historians need to find out? What primary sources would enable historians to understand this topic better?

You might find history books that inspire you by asking your history teacher for recommendations, visiting your local public library, or finding out about books that have just been published in history podcasts or newspaper book reviews. You can also look at:

Access to Research - provides free access to many academic journal articles, so that you can search for the latest research on whatever aspect of history interests you. - https://accesstoresearch.org.uk/search

JSTOR - a searchable digital library of journal articles and books. If your school or local library doesn’t have access, you can normally register for an individual researcher account to read 6 free articles per month. - https://www.jstor.org/

Write about your ideas and talk with other people about whatever you find interesting.

Apply these same critical skills to everything you watch, listen to, or visit.

2) Listen to history podcasts

- Faculty of History Recordings

- BBC podcasts - Radio 4 ‘In Our Time’, ‘The Long View’, ‘Document’; BBC World Service ‘Witness’; Radio 3 ‘Free Thinking’, all available via BBC Sounds.

- BBC History Extra podcasts: http://www.historyextra.com/podcasts

- Historical Association podcasts: https://www.history.org.uk/podcasts

- Royal Historical Society podcasts: https://royalhistsoc.org/category/podcasts/

- Gresham College lectures: https://www.gresham.ac.uk/watch

- TED talks: https://www.ted.com/

- Intelligence Squared debates: https://www.intelligencesquared.com/watch-and-listen/

- Malcolm Gladwell ‘Revisionist History’ podcasts: http://revisionisthistory.com/about

3) Visit museums, archives, or other historic sites

- Museums, archives and galleries: https://museumcrush.org/

- BBC Arts https://www.bbc.co.uk/arts

- British Library primary sources and resources: https://www.bl.uk/learning/online-resources

- National Archives primary sources and resources: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/

4) Engage with the news

- ‘The Conversation’ - academic research relevant to news stories: https://theconversation.com/uk

- The Guardian ‘The long read’ - in-depth reporting: https://www.theguardian.com/news/series/the-long-read

- History & Policy - connections between history and current policy-making: http://www.historyandpolicy.org/

5) Take part in outreach activities

- Oxford University outreach events – free events for which students or teachers can apply: http://www.ox.ac.uk/admissions/undergraduate/increasing-access

- Oxplore: the Home of Big Questions – explore ideas and debates online with researchers at Oxford University: https://oxplore.org/

Primary Source Exercises

These exercises allow you to explore the primary sources that shape Oxford historians’ latest research and teaching. We have also suggested online resources that enable you to develop your own interests in the past and to do original historical research. These research skills will also help you to feel confident when reading a primary source in the History Admissions Test or as part of an interview.

The Princeton Guide to Historical Research

- Zachary Schrag

Before you purchase audiobooks and ebooks

Please note that audiobooks and ebooks purchased from this site must be accessed on the Princeton University Press app. After you make your purchase, you will receive an email with instructions on how to download the app. Learn more about audio and ebooks .

Support your local independent bookstore.

- United States

- United Kingdom

The essential handbook for doing historical research in the twenty-first century

- Skills for Scholars

- Look Inside

- Request Exam Copy

- Download Cover

The Princeton Guide to Historical Research provides students, scholars, and professionals with the skills they need to practice the historian’s craft in the digital age, while never losing sight of the fundamental values and techniques that have defined historical scholarship for centuries. Zachary Schrag begins by explaining how to ask good questions and then guides readers step-by-step through all phases of historical research, from narrowing a topic and locating sources to taking notes, crafting a narrative, and connecting one’s work to existing scholarship. He shows how researchers extract knowledge from the widest range of sources, such as government documents, newspapers, unpublished manuscripts, images, interviews, and datasets. He demonstrates how to use archives and libraries, read sources critically, present claims supported by evidence, tell compelling stories, and much more. Featuring a wealth of examples that illustrate the methods used by seasoned experts, The Princeton Guide to Historical Research reveals that, however varied the subject matter and sources, historians share basic tools in the quest to understand people and the choices they made.

- Offers practical step-by-step guidance on how to do historical research, taking readers from initial questions to final publication

- Connects new digital technologies to the traditional skills of the historian

- Draws on hundreds of examples from a broad range of historical topics and approaches

- Shares tips for researchers at every skill level

Skills for Scholars: The new tools of the trade

Awards and recognition.

- Winner of the James Harvey Robinson Prize, American Historical Association

- A Choice Outstanding Academic Title of the Year

- Introduction: History Is for Everyone

- History Is the Study of People and the Choices They Made

- History Is a Means to Understand Today’s World

- History Combines Storytelling and Analysis

- History Is an Ongoing Debate

- Autobiography

- Everything Has a History

- Narrative Expansion

- From the Source

- Public History

- Research Agenda

- Factual Questions

- Interpretive Questions

- Opposing Forces

- Internal Contradictions

- Competing Priorities

- Determining Factors

- Hidden or Contested Meanings

- Before and After

- Dialectics Create Questions, Not Answers

- Copy Other Works

- History Big and Small

- Pick Your People

- Add and Subtract

- Narrative versus Thematic Schemes

- The Balky Time Machine

- Local and Regional

- Transnational and Global

- Comparative

- What Is New about Your Approach?

- Are You Working in a Specific Theoretical Tradition?

- What Have Others Written?

- Are Others Working on It?

- What Might Your Critics Say?

- Primary versus Secondary Sources

- Balancing Your Use of Secondary Sources

- Sets of Sources

- Sources as Records of the Powerful

- No Source Speaks for Itself

- Languages and Specialized Reading

- Choose Sources That You Love

- Workaday Documents

- Specialized Periodicals

- Criminal Investigations and Trials

- Official Reports

- Letters and Petitions

- Institutional Records

- Scholarship

- Motion Pictures and Recordings

- Buildings and Plans

- The Working Bibliography

- The Open Web

- Limits of the Open Web

- Bibliographic Databases

- Full-Text Databases

- Oral History

- What Is an Archive?

- Archives and Access

- Read the Finding Aid

- Follow the Rules

- Work with Archivists

- Types of Cameras

- How Much to Shoot?

- Managing Expectations

- Duck, Duck, Goose

- Credibility

- Avoid Catastrophe

- Complete Tasks—Ideally Just Once, and in the Right Order

- Maintain Momentum

- Kinds of Software

- Word Processors

- Means of Entry

- A Good Day’s Work

- Word Count Is Your Friend

- Managing Research Assistants

- Research Diary

- When to Stop

- Note-Taking as Mining

- Note-Taking as Assembly

- Identify the Source, So You Can Go Back and Consult if Needed

- Distinguish Others’ Words and Ideas from Your Own

- Allow Sorting and Retrieval of Related Pieces of Information

- Provide the Right Level of Detail

- Notebooks and Index Cards

- Word Processors for Note-Taking

- Plain Text and Markdown

- Reference Managers

- Note-Taking Apps

- Relational Databases

- Spreadsheets

- Glossaries and Alphabetical Lists

- Image Catalogs

- Other Specialized Formats

- The Working Draft

- Variants: The Ten- and Thirty-Page Papers

- Thesis Statement

- Historiography

- Sections as Independent Essays

- Topic Sentences

- Answering Questions

- Invisible Bullet Points

- The Perils of Policy Prescriptions

- A Model (T) Outline

- Flexibility

- Protagonists

- Antagonists

- Bit Players

- The Shape of the Story

- The Controlling Idea

- Alchemy: Turning Sources to Stories

- Turning Points

- Counterfactuals

- Point of View

- Symbolic Details

- Combinations

- Speculation

- Is Your Jargon Really Necessary?

- Defining Terms

- Word Choice as Analysis

- Period Vocabulary or Anachronism?

- Integrate Images into Your Story

- Put Numbers in Context

- Summarize Data in Tables and Graphs

- Why We Cite

- Citation Styles

- Active Verbs

- People as Subjects

- Signposting

- First Person

- Putting It Aside

- Reverse Outlining

- Auditing Your Word Budget

- Writing for the Ear

- Conferences

- Social Media

- Coauthorship

- Tough, Fair, and Encouraging

- Manuscript and Book Reviews

- Journal Articles

- Book chapters

- Websites and Social Media

- Museums and Historic Sites

- Press Appearances and Op-Eds

- Law and Policy

- Graphic History, Movies, and Broadway Musicals

- Acknowledgments

"This volume is a complete and sophisticated addition to any scholar’s library and a boon to the curious layperson. . . . [A] major achievement."— Choice Reviews

"This book is quite simply a gem. . . . Schrag’s accessible style and comprehensive treatment of the field make this book a valuable resource."—Alan Sears, Canadian Journal of History

"A tour de force that will help all of us be more capable historians. This wholly readable, delightful book is packed with good advice that will benefit seasoned scholars and novice researchers alike."—Nancy Weiss Malkiel, author of "Keep the Damned Women Out": The Struggle for Coeducation

"An essential and overdue contribution. Schrag's guide offers a lucid breakdown of what historians do and provides plenty of examples."—Jessica Mack, Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, George Mason University

"Extraordinarily useful. If there is another book that takes apart as many elements of the historian's craft the way that Schrag does and provides so many examples, I am not aware of it."—James Goodman, author of But Where Is the Lamb?

"This is an engaging guide to being a good historian and all that entails."—Diana Seave Greenwald, Assistant Curator of the Collection, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

"Impressive and engaging. Schrag gracefully incorporates the voices of dozens, if not hundreds, of fellow historians. This gives the book a welcome conversational feeling, as if the reader were overhearing a lively discussion among friendly historians."—Sarah Dry, author of Waters of the World: The Story of the Scientists Who Unraveled the Mysteries of Our Oceans, Atmosphere, and Ice Sheets and Made the Planet Whole

"This is a breathtaking book—wide-ranging, wonderfully written, and extremely useful. Every page brims with fascinating, well-chosen illustrations of creative research, writing, and reasoning that teach and inspire."—Amy C. Offner, author of Sorting Out the Mixed Economy

historyprofessor.org website, maintained by Zachary M. Schrag, Professor of History at George Mason University

Stay connected for new books and special offers. Subscribe to receive a welcome discount for your next order.

- ebook & Audiobook Cart

- Researching

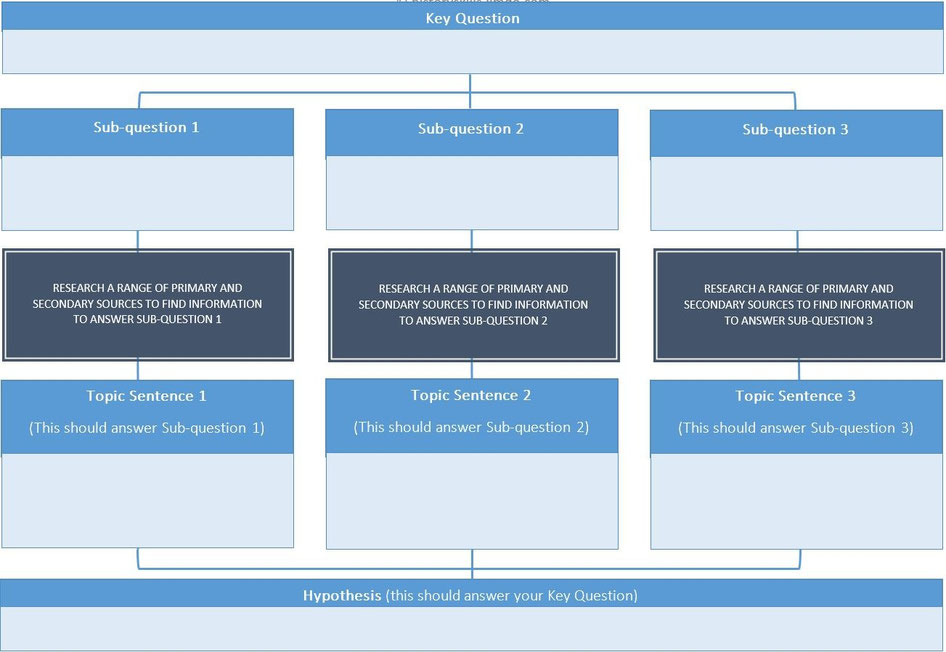

The historical research process explained

Researching for a History assessment piece can often be the most daunting part of the subject. However, it needn't be. Research is a systematic process that, if followed step-by-step, will become a logical and efficient part of your work. Below are links to the nine stages of good research, providing explanations and examples for each one.

- Key Inquiry Question

- Background Research

- Sub-questions

- Source Research

- Organise Quotes

- Topic Sentences

- Draft Writing

- Final Draft

Other potential research stages:

- Research Rationale

- Critical Summary of Research

Overview of the research process

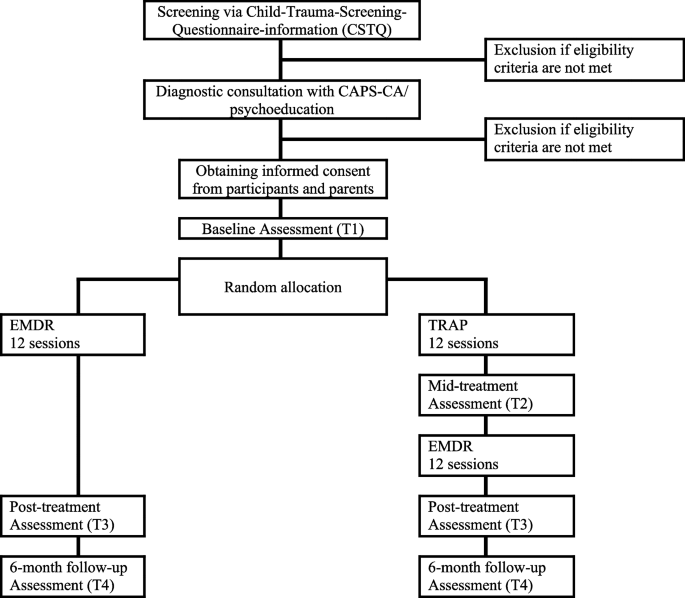

Below is a pictorial explanation about how the research process works to create a hypothesis from the results of question-driven research. As you follow the research steps, each section of the diagram is completed.

Let's get started

Need a digital Research Journal?

Additional resources

What do you need help with, download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- Undergraduate courses

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Postgraduate courses

- How to apply

- Postgraduate events

- Fees and funding

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Term dates and calendars

- Visiting the University

- Annual reports

- Equality and diversity

- A global university

- Public engagement

- Give to Cambridge

- For Cambridge students

- For our researchers

- Business and enterprise

- Colleges & departments

- Email & phone search

- Museums & collections

- Student information

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

- About the Department overview

- How to find the Department

- Annual Report

- HPS Discussion email list

- Becoming a Visiting Scholar or Visiting Student overview

- Visitor fee payment

- Becoming an Affiliate

- Applying for research grants and post-doctoral fellowships

- Administration overview

- Information for new staff

- Information for examiners and assessors overview

- Operation of the HPS plagiarism policy

- Information for supervisors overview

- Supervising Part IB and Part II students

- Supervising MPhil and Part III students

- Supervising PhD students

- People overview

- Teaching Officers

- Research Fellows and Teaching Associates

- Professional Services Staff

- PhD Students

- Research overview

- Research projects overview

- Digitising Philippine Flora

- Colonial Natures overview

- The Challenge of Conservation

- Natural History in the Age of Revolutions, 1776–1848

- In the Shadow of the Tree: The Diagrammatics of Relatedness as Scientific, Scholarly and Popular Practice

- The Many Births of the Test-Tube Baby

- Culture at the Macro-Scale: Boundaries, Barriers and Endogenous Change

- Making Climate History overview

- Project summary

- Workstreams

- Works cited and project literature

- Histories of Artificial Intelligence: A Genealogy of Power overview

- From Collection to Cultivation: Historical Perspectives on Crop Diversity and Food Security overview

- Call for papers

- How Collections End: Objects, Meaning and Loss in Laboratories and Museums

- Tools in Materials Research

- Epsilon: A Collaborative Digital Framework for Nineteenth-Century Letters of Science

- Contingency in the History and Philosophy of Science

- Industrial Patronage and the Cold War University

- FlyBase: Communicating Drosophila Genetics on Paper and Online, 1970–2000

- The Lost Museums of Cambridge Science, 1865–1936

- From Hansa to Lufthansa: Transportation Technologies and the Mobility of Knowledge in Germanic Lands and Beyond, 1300–2018

- Medical Publishers, Obscenity Law and the Business of Sexual Knowledge in Victorian Britain

- Kinds of Intelligence

- Varieties of Social Knowledge

- The Vesalius Census

- Histories of Biodiversity and Agriculture

- Investigating Fake Scientific Instruments in the Whipple Museum Collection

- Before HIV: Homosex and Venereal Disease, c.1939–1984

- The Casebooks Project

- Generation to Reproduction

- The Darwin Correspondence Project

- History of Medicine overview

- Events overview

- Past events

- Philosophy of Science overview

- Study HPS overview

- Undergraduate study overview

- Introducing History and Philosophy of Science

- Frequently asked questions

- Routes into History and Philosophy of Science

- Part II overview

- Distribution of Part II marks

- BBS options

- Postgraduate study overview

- Why study HPS at Cambridge?

- MPhil in History and Philosophy of Science and Medicine overview

- A typical day for an MPhil student

- MPhil in Health, Medicine and Society

- PhD in History and Philosophy of Science overview

- Part-time PhD

PhD placement record

- Funding for postgraduate students

- Student information overview

- Timetable overview

- Primary source seminars

- Research methods seminars

- Writing support seminars

- Dissertation seminars

- BBS Part II overview

- Early Medicine

- Modern Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

- Philosophy of Science and Medicine

- Ethics of Medicine

- Philosophy and Ethics of Medicine

- Part III and MPhil

- Single-paper options

- Part IB students' guide overview

- About the course

- Supervisions

- Libraries and readings

- Scheme of examination

- Part II students' guide overview

- Primary sources

- Dissertation

- Key dates and deadlines

- Advice overview

- Examination advice

- Learning strategies and exam skills

- Advice from students

- Part III students' guide overview

- Essays and dissertation

- Subject areas

- MPhil students' guide overview

- PhD students' guide overview

- Welcome to new PhDs

- Registration exercise and annual reviews

- Your supervisor and advisor

- Progress log

- Intermission and working away from Cambridge

- The PhD thesis

- Submitting your thesis

- Examination

- News and events overview

- Seminars and reading groups overview

- Departmental Seminars

- Coffee with Scientists

- Cabinet of Natural History overview

- Publications

- History of Medicine Seminars

- Purpose and Progress in Science

- The Anthropocene

- Calculating People

- Measurement Reading Group

- Teaching Global HPSTM

- Pragmatism Reading Group

- Foundations of Physics Reading Group

- History of Science and Medicine in Southeast Asia

- Atmospheric Humanities Reading Group

- Science Fiction & HPS Reading Group

- Values in Science Reading Group

- Cambridge Reading Group on Reproduction

- HPS Workshop

- Postgraduate Seminars overview

- Images of Science

- Language Groups overview

- Latin Therapy overview

- Bibliography of Latin language resources

- Fun with Latin

- Archive overview

- Lent Term 2024

- Michaelmas Term 2023

- Easter Term 2023

- Lent Term 2023

- Michaelmas Term 2022

- Easter Term 2022

- Lent Term 2022

- Michaelmas Term 2021

- Easter Term 2021

- Lent Term 2021

- Michaelmas Term 2020

- Easter Term 2020

- Lent Term 2020

- Michaelmas Term 2019

- Easter Term 2019

- Lent Term 2019

- Michaelmas Term 2018

- Easter Term 2018

- Lent Term 2018

- Michaelmas Term 2017

- Easter Term 2017

- Lent Term 2017

- Michaelmas Term 2016

- Easter Term 2016

- Lent Term 2016

- Michaelmas Term 2015

- Postgraduate and postdoc training overview

- Induction sessions

- Academic skills and career development

- Print & Material Sources

- Other events and resources

Tools and techniques for historical research

- About the Department

- News and events

If you are just starting out in HPS, this will be the first time for many years – perhaps ever – that you have done substantial library or museum based research. The number of general studies may seem overwhelming, yet digging out specific material relevant to your topic may seem like finding needles in a haystack. Before turning to the specific entries that make up this guide, there are a few general points that apply more widely.

Planning your research

Because good research and good writing go hand in hand, probably the single most important key to successful research is having a good topic. For that, all you need at the beginning are two things: (a) a problem that you are genuinely interested in and (b) a specific issue, controversy, technique, instrument, person, etc. that is likely to offer a fruitful way forward for exploring your problem. In the early stages, it's often a good idea to be general about (a) and very specific about (b). So you might be interested in why people decide to become doctors, and decide to look at the early career of a single practitioner from the early nineteenth century, when the evidence for this kind of question happens to be unusually good. You can get lots of advice from people in the Department about places to look for topics, especially if you combine this with reading in areas of potential interest. Remember that you're more likely to get good advice if you're able to mesh your interests with something that a potential supervisor knows about. HPS is such a broad field that it's impossible for any department to cover all aspects of it with an equal degree of expertise. It can be reassuring to know that your topic will evolve as your research develops, although it is vital that you establish some basic parameters relatively quickly. Otherwise you will end up doing the research for two, three or even four research papers or dissertations, when all you need is the material for one.

Before beginning detailed work, it's obviously a good idea to read some of the secondary literature surrounding your subject. The more general books are listed on the reading lists for the Part II lecture courses, and some of the specialist literature is listed in these research guides. This doesn't need to involve an exhaustive search, at least not at this stage, but you do need to master the fundamentals of what's been done if you're going to be in a position to judge the relevance of anything you find. If there are lectures being offered in your topic, make sure to attend them; and if they are offered later in the year, try to see if you can obtain a preliminary bibliography from the lecturer.

After that, it's usually a good idea to immerse yourself in your main primary sources as soon as possible. If you are studying a museum object, this is the time to look at it closely; if you're writing about a debate, get together the main papers relevant to it and give them a close read; if you're writing about a specific experiment, look at the published papers, the laboratory notebook, and the relevant letters. Don't spend hours in the early stages of research ferreting out hard-to-find details, unless you're absolutely positive that they are of central importance to the viability of your topic. Start to get a feel for the material you have, and the questions that might be explored further. Make an outline of the main topics that you hope to cover, organized along what you see as the most interesting themes (and remember, 'background' is not usually an interesting theme on its own).

At this stage, research can go in many different directions. At some point, you'll want to read more about the techniques other historians have used for exploring similar questions. Most fields have an established repertoire of ways of approaching problems, and you need to know what these are, especially if you decide to reject them. One of the advantages of an interdisciplinary field like HPS is that you are exposed to different and often conflicting ways of tackling similar questions. Remember that this is true within history itself, and you need to be aware of alternatives. This may well involve looking further afield, at classic books or articles that are not specifically on 'your' subject. For example, it may be that you could find some helpful ideas for a study of modern scientific portraiture in a book on the eighteenth century. The best books dealing with educational maps may not be on the astronomical ones you are studying, but on ones used for teaching classical geography. See where the inspiration for works you admire comes from, and have a look at the sources they have used. This will help you develop the kind of focussed questions that make for a successful piece of work.

As you develop an outline and begin to think through your topic in more detail, you'll be in good position to plan possible lines of research. Don't try to find out everything about your topic: pick those aspects that are likely to prove most fruitful for the direction your essay seems to be heading. For example, it may be worth spending a long time searching for biographical details about a person if their career and life are central to your analysis; but in many other cases, such issues may not be very important. If your interest is in the reception of a work, it is likely to be more fruitful to learn a lot about a few commentaries or reviews (where they appeared, who wrote them, and so forth) than to gather in randomly all the comments you can find.

Follow up hints in other people's footnotes. Works that are otherwise dull or outdated in approach are sometimes based on very solid research. One secondary reference to a crucial letter or newspaper article can save you hours of mindless trawling, and lead you straight to the information you need. Moreover, good historians often signal questions or sources that they think would be worth investigating further.

Remember that the best history almost always depends on developing new approaches and interpretations, not on knowing about a secret archive no one has used before. If you give your work time to develop, and combine research with writing, you will discover new sources, and (better still) a fresh importance for material that has supposedly been known for a long time. As you become familiar with your topic, you are likely to find that evidence you dug out at the beginning of your project is much more significant than you thought it was. In historical research, the most important evidence often isn't sitting there on the surface – it's something you need to dig out through close reading and an understanding of the situation in which the document you are studying was written, or in which the object was produced. This is especially true of instruments, paintings and other non-textual sources.

Some standard reference works

Your research should become more focussed as time goes on. Don't just gather randomly: you should always have at least some idea of why you are looking for something, and what you might hope to find. Make guesses, follow up hunches, see if an idea you have has the possibility to work out. At the beginning, it can be valuable to learn the full range of what is available, but eventually you should be following up specific issues, a bit like a detective tracing the clues to a mystery. It is at this stage of research, which is often best done in conjunction with writing up sections of your project, that knowing where to find answers to specific questions is most useful. There is nothing more disheartening than spending a week to find a crucial fact, only to discover that it's been sitting on the shelf next to you all term. The Whipple has a wide variety of guides, biographical dictionaries and bibliographies, so spend a few minutes early on looking at the reference shelves.

Every major country has a national biographical dictionary (the new version of the British one is the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , available 2004 online). For better-known scientists, a good place to start is Charles C. Gillispie (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography (1970–1980). There are more specialized dictionaries for every scientific field, from entomology to astronomy. The University Library has a huge selection of biographical sources; ask your supervisor about the best ones for your purpose.

Preliminary searching for book titles and other bibliographical information is now often best done online, and every historian should know how to use the British Library's online search facility; COPAC (the UK national library database); and WorldCat (an international database). All of these are accessible through the HPS Whipple Library website (under 'other catalogues'). At the time of writing, the University Library is remains one of the few libraries of its size to have many of its records not available online, so remember that you have to check the green guard-book catalogues (and the supplementary catalogues) for most items published before 1977. It is hoped that this situation will be rectified soon. There are also numerous bibliographies for individual sciences and subjects, together with catalogues of relevant manuscripts. Most of these are listed elsewhere in this guide.

As questions arise, you will want to be able to access books and articles by other historians that touch upon your subject. There are many sources for this listed elsewhere in this guide, but you should definitely know about the Isis Current Bibliography and The Wellcome Bibliography for the History of Medicine . Both are available online, the former through the RLG History of Science, Technology and Medicine database, the latter through the website of the Wellcome Library.

Libraries and museums

Finally, a word in praise of libraries and museums. As the comments above make clear, the internet is invaluable for searching for specific pieces of information. If you need a bibliographical reference or a general reading list from a course at another university, it is an excellent place to begin. If you are looking for the source of an unidentified quotation, typing it into Google (or an appropriate database held by the University Library) will often turn up the source in seconds. Many academic journals are now online, as are the texts of many books, though not always in a paginated or citable form.

For almost all historical topics, however, libraries filled with printed books and journals will remain the principal tools for research, just as museums will continue to be essential to any work dealing with the material culture of past science. The reason for this is simple: what is on the internet is the result of decisions by people in the past decade, while libraries and museums are the product of a continuous history of collecting over several thousand years. Cambridge has some of the best collections for the history of science anywhere. Despite what is often said, this is not because of the famous manuscripts or showpiece books (these are mostly available in other ways), but because of the depth and range of its collections across the whole field. The Whipple Library is small and friendly, and has an unparalleled selection of secondary works selected over many years – don't just go for specific titles you've found in the catalogue, try browsing around, and ask the librarians for help if you can't see what you are looking for. Explore the Whipple Museum and talk to the curator and the staff. There are rich troves of material in these departmental collections, on topics ranging from phrenology and microscopy to the early development of pocket calculators. Become familiar with what the University Library has to offer: it is large and sometimes idiosyncratic, but worth getting to know well if you are at all serious about research. It is a fantastic instrument for studying the human past – the historian's equivalent of CERN or the Hubble Telescope. And all you need to get in is a student ID.

Further reading

Wayne C. Booth, Gregory G. Colomb, and Joseph M. William, The Craft of Research , 2nd ed. (University of Chicago Press, 2003).

Email search

Privacy and cookie policies

Study History and Philosophy of Science

Undergraduate study

Postgraduate study

Library and Museum

Whipple Library

Whipple Museum

Museum Collections Portal

Research projects

History of Medicine

Philosophy of Science

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- Contact the University

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

- Privacy policy and cookies

- Statement on Modern Slavery

- Terms and conditions

- University A-Z

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- Research news

- About research at Cambridge

- Spotlight on...

- Create new account

Historians research, analyze, interpret, and write about the past by studying historical documents and sources.

Historians typically do the following:

- Gather historical data from various sources, including archives, books, and artifacts

- Analyze and interpret historical information to determine its authenticity and significance

- Trace historical developments in a particular field

- Engage with the public through educational programs and presentations

- Archive or preserve materials and artifacts in museums, visitor centers, and historic sites

- Provide advice or guidance on historical topics and preservation issues

- Write reports, articles, and books on findings and theories

Historians conduct research and analysis for governments, businesses, individuals, nonprofits, historical associations, and other organizations. They use a variety of sources in their work, including government and institutional records, newspapers, photographs, interviews, films, and unpublished manuscripts, such as personal diaries, letters, and other primary source documents. They also may process, catalog, and archive these documents and artifacts.

Many historians present and interpret history in order to inform or build upon public knowledge of past events. They often trace and build a historical profile of a particular person, area, idea, organization, or event. Once their research is complete, they present their findings through articles, books, reports, exhibits, websites, and educational programs.

In government, some historians conduct research to provide information on specific events or groups. Many write about the history of a particular government agency, activity, or program, such as a military operation or space missions. For example, they may research the people and events related to Operation Desert Storm.

In historical associations, historians may work with archivists, curators, and museum workers to preserve artifacts and explain the historical significance of a wide variety of subjects, such as historic buildings, religious groups, and battlegrounds. Workers with a background in history also may go into one of these occupations.

Many people with a degree in history also become high school teachers or postsecondary teachers.

Historians held about 3,300 jobs in 2021. The largest employers of historians were as follows:

| Professional, scientific, and technical services | 25% |

| Federal government, excluding postal service | 23 |

| Local government, excluding education and hospitals | 15 |

| State government, excluding education and hospitals | 15 |

Historians work in museums, archives, historical societies, and research organizations. Some work as consultants for these organizations while being employed by consulting firms, and some work as independent consultants.

Work Schedules

Most historians work full time during regular business hours. Some work independently and are able to set their own schedules. Historians who work in museums or other institutions open to the public may work evenings or weekends. Some historians may travel to collect artifacts, conduct interviews, or visit an area to better understand its culture and environment.

Historians typically need at least a master’s degree to enter the occupation. Those with a bachelor’s degree in history may qualify for some entry-level positions, but most will find jobs in different fields.

Historians typically need a master’s degree or Ph.D. to enter the occupation. Many historians have a master’s degree in history or public history. Others complete degrees in related fields, such as museum studies, historical preservation, or archival management.

In addition to coursework, most master’s programs in public history and similar fields require an internship as part of the curriculum.

Research positions in the federal government and positions in academia typically require a Ph.D. Students in history Ph.D. programs usually concentrate in a specific area of history. Possible specializations include a particular country or region, period, or field, such as social, political, or cultural history.

Candidates with a bachelor’s degree in history may qualify for entry-level positions at museums, historical associations, or other small organizations. However, most bachelor’s degree holders usually work outside of traditional historian jobs—for example, jobs in education, communications, law, business, publishing, or journalism.

Other Experience

Many employers recommend that prospective historians complete an internship during their formal educational studies. Internships offer an opportunity for students to learn practical skills, such as handling and preserving artifacts and creating exhibits. They also give students an opportunity to apply their academic knowledge in a hands-on setting.

Historians typically have an interest in the Thinking interest area, according to the Holland Code framework. The Thinking interest area indicates a focus on researching, investigating, and increasing the understanding of natural laws.

If you are not sure whether you have a Thinking interest which might fit with a career as a historian, you can take a career test to measure your interests.

Historians should also possess the following specific qualities:

Analytical skills. Historians must be able to examine the information and data in historical sources and draw logical conclusions from them, whether the sources are written documents, visual images, or material artifacts.

Communication skills. Communication skills are important for historians because many give presentations on their historical specialty to the public. Historians also need communication skills when they interview people to collect oral histories, consult with clients, or collaborate with colleagues in the workplace.

Problem-solving skills. Historians try to answer questions about the past. They may investigate something unknown about a past idea, event, or person; decipher historical information; or identify how the past has affected the present.

Research skills. Historians must be able to examine and process information from a large number of historical documents, texts, and other sources.

Writing skills. Writing skills are essential for historians as they often present their findings in reports, articles, and books.

The median annual wage for historians was $63,940 in May 2021. The median wage is the wage at which half the workers in an occupation earned more than that amount and half earned less. The lowest 10 percent earned less than $37,310, and the highest 10 percent earned more than $118,380.

In May 2021, the median annual wages for historians in the top industries in which they worked were as follows:

| Federal government, excluding postal service | $101,910 |

| Professional, scientific, and technical services | 61,910 |

| State government, excluding education and hospitals | 51,460 |

| Local government, excluding education and hospitals | 45,940 |

Most historians work full time during standard business hours. Some work independently and are able to set their own schedules. Historians who work in museums or other institutions open to the public may work evenings or weekends. Some historians may travel to collect artifacts, conduct interviews, or visit an area to better understand its culture and environment.

Employment of historians is projected to grow 4 percent from 2021 to 2031, about as fast as the average for all occupations.

About 300 openings for historians are projected each year, on average, over the decade. Many of those openings are expected to result from the need to replace workers who transfer to different occupations or exit the labor force, such as to retire.

Organizations that employ historians, such as historical societies and government agencies, often depend on donations or public funding. Thus, employment growth will depend largely on the amount of funding available.

For more information about historians, visit

American Association for State and Local History

American Historical Association

National Council on Public History

Organization of American Historians

Where does this information come from?

The career information above is taken from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Outlook Handbook . This excellent resource for occupational data is published by the U.S. Department of Labor every two years. Truity periodically updates our site with information from the BLS database.

I would like to cite this page for a report. Who is the author?

There is no published author for this page. Please use citation guidelines for webpages without an author available.

I think I have found an error or inaccurate information on this page. Who should I contact?

This information is taken directly from the Occupational Outlook Handbook published by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Truity does not editorialize the information, including changing information that our readers believe is inaccurate, because we consider the BLS to be the authority on occupational information. However, if you would like to correct a typo or other technical error, you can reach us at [email protected] .

I am not sure if this career is right for me. How can I decide?

There are many excellent tools available that will allow you to measure your interests, profile your personality, and match these traits with appropriate careers. On this site, you can take the Career Personality Profiler assessment, the Holland Code assessment, or the Photo Career Quiz .

Get Our Newsletter

Please enable JavaScript in your web browser to get the best experience.

You are here:

- Study & Training

Research Training

We deliver high-quality training programmes and short courses to a wide community of historians and professionals, and provide unique distance learning opportunities.

- Share page on Twitter

- Share page on Facebook

- Share page on LinkedIn

Research Training at the IHR

Each year we run an extensive programme of training in historical research skills for professional historians, independent researchers, and early career scholars. Courses vary in length from one day to one term, and cover a variety of subjects from language learning to digital research practices.

Contact the Research Training office

Please get in touch to learn more about research training opportunities at the IHR.

Contact: Dr Eve Hayes de Kalaf General enquiries: [email protected] Office hours: Monday-Friday (09:00-16:30) For booking and payment enquiries, please contact the SAS Academic Engagement and Impact team: [email protected]

Upcoming Training Events

Academic Self-Publishing – how, why

Our courses.

Applied Public History: Places, People, Stories

This course introduces learners to applied public history: understanding and interpreting the past today, and engaging diverse communities in the practice of making and sharing histories.

Databases for historians

This 4-day course is an introduction to the theory and practice of constructing and using databases.

Day for new research students

The Institute of Historical Research is delighted to welcome those commencing research degrees in history and related disciplines in London, the South East and throughout the UK.

Online Sources for Historians

This one-day course provides an intensive introduction to using the internet as a tool for academic historical research, demonstrating the most useful resources, and teaching techniques to make the best use of them.

Making Maps and Analysing Historical Data in GIS

This 1 day course introduces the practicalities of mapping historical information using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software.

Methods and sources for historical research

This course aims to equip historical researchers with the skills they will need to find and gain access to all the primary source materials they need for their projects.

Palaeography and diplomatic

The course is designed to help students to work with medieval and early modern manuscripts.

Using Historical Maps in GIS

This 1 day course focuses upon working with historic maps as sources, and the skills and tools needed to work with them digitally.

Book your place

Browse our full programme of research training sessions and book your place.

Related Content

Study with Us

We offer an M.Phil/PhD programme supervised by research subject area experts.

Early Career Fellowships

IHR Early Career Research Fellowships provide funding to enable early career historians to complete a doctorate or to undertake post-doctoral research.

The IHR offers a wide range of awards, bursaries and prizes to enable and reward high-quality research and publishing.

IHR Internships

- Request Info

- Resource Library

How to Become a History Researcher: Steps and Career Outlook

History Researcher

Researchers in all fields leverage their intellectual curiosity and analytical skills to uncover new information and share their findings with the world. History researchers are no exception, as they often have a zeal for sifting through the fragments of the historical record in order to gather details that may illuminate significant moments of the past. Individuals who pursue careers in history research can put their skills to use in a variety of professions in academia, government, military, economics, museums, and the private sector. Individuals interested in how to become a history researcher can prepare for the role by pursuing a Master of Arts in History degree.

What Does a History Researcher Do?

History researchers study past events, people, policies, and documents to gain an in-depth understanding of their significance and impact on modern and future societies. Examining primary and secondary sources is an essential part of a history researcher’s job. They interpret and translate texts into different languages, contribute to research for textbooks, and assist museum curators and historians in preserving artifacts and documents. History researchers may work at universities and conduct specialized research on a certain topic. Areas of study can range from the impact of religion on ancient governments to American history.

History researchers begin by identifying a broad question or topic, and then search for and analyze past research studies on the same subject. After refining or narrowing their scope of study, they decide which historical research method to use. They find primary and secondary sources through university or library archives, historical societies, and public records, analyzing the accuracy of these sources and using their findings to write and publish academic papers or books.

Career Options for History Researchers

History researchers can take on many important roles in a range of private industries and government agencies. Advanced history degree programs, such as a Master of Arts in History, focus heavily on research techniques, subject matter expertise, and practical applications of findings. An advanced history degree can help individuals learn how to become history researchers and achieve success in their field. Some career options for history researchers include those in the following sections.

Research Historian

A research historian’s goal is to understand how and why important past events occurred by interpreting facts in many different contexts. The grist of the researcher’s analysis is historical evidence, which includes primary sources, such as material artifacts, documents, and recorded firsthand recollections, and secondary sources, which are often the work of other historians. Their work may be exhibited in museums, used in lectures, published in academic journals, or referenced in a variety of other media.

Museum Researcher

Museum researchers are responsible for providing artifact descriptions, authenticating historical materials, and contributing to exhibits and educational programs. Most museum researchers possess specialized knowledge in a particular field, and some focus their work on a particular type of historical record, such as manuscripts, photographs, maps, or video and audio recordings. Museum researchers may also be involved in acquiring and curating new pieces for display.

Cultural Resource Manager

Cultural resource managers are charged with not only safeguarding historically significant artifacts and materials but also memorializing the cultural heritage that they represent. The tools of the cultural preservationist’s trade include historical maps, government records, contemporary publications, oral histories, and secondary sources.

FBI Intelligence Analyst

Historians with strong technical and analytical skills may qualify for specialized careers in the intelligence community. FBI intelligence analysts collect and interpret information from many different sources to identify threats and communicate them to decision-makers. Analysts with backgrounds in historical research can advise on potential responses to these threats by drawing from their knowledge of similar events in the past. The FBI Intelligence Analyst Selection Process (IASP) tests critical thinking, writing, analytical skills, and time management—all areas of emphasis in Master of Arts in History programs.

U.S. Navy Historian

History researchers can leverage their expertise in past social and political events to support and consult government agencies. The Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) employs history researchers, archivists, and other personnel who are responsible for “using the power of history and heritage to enhance the warfighting capability of the U.S. Navy,” according to the NHHC. Specifically, the agency collects and preserves materials of historical significance to the Navy, in addition to assisting in the recovery and preservation of lost Navy ships and aircraft.

University Professor

As businesses and government agencies increasingly hire historians as consultants, higher education institutions are in need of history professors to prepare the next generation of researchers, according to the Journal of Research Practice. In addition to teaching and conducting research in history departments at colleges and universities, history professors may teach courses in other departments, such as political science and public affairs.

History Researcher Salaries

History researchers earn different salaries based on their specific jobs, education level, and years of experience.

- Historian . Historians earned a median annual salary of $63,690 as of May 2019, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

- Museum researcher . The BLS reports that the median annual salary for archivists, curators, and museum researchers was $49,850 as of May 2019.

- Cultural resource manager . The BLS groups cultural resource managers with anthropologists and archaeologists, and reports that individuals in these positions earned a median annual salary of $63,670 as of May 2019.

- FBI intelligence analyst . The median annual salary for FBI intelligence analysts is about $70,000, according to the compensation website PayScale.

- Navy historian . Annual salaries for navy historians range depending on the position, but a supervisory curator, for example, may earn between $96,070 and $126,062, according to the U.S. Office of Personnel Management.

- University professor . Postsecondary history professors earned a median annual salary of $75,170 as of May 2019, according to the BLS.

Steps for Becoming a History Researcher

While no standard path to become a history researcher exists, the common thread for those who work in the field is thorough academic preparation combined with real-world experience gained through internships and jobs.

Step 1: Pursue an Advanced Education

The first step in preparing to thrive as a history researcher is to lay a solid academic foundation, beginning with a bachelor’s degree in a relevant field. While working through their undergraduate history coursework, aspiring researchers can build valuable career skills by taking classes in computer science, data analysis, writing, or a foreign language. A bachelor’s degree may be sufficient to qualify for some entry-level historian positions, but for most historian jobs, a master’s degree or doctorate is mandatory. Many history researchers have a Master of Arts in History degree, while some hold degrees in subjects such as museum studies, historic preservation, and archiving.

Step 2: Gain Experience

While students may learn about the day-to-day work of history researchers in internships and field assignments, there’s no substitute for the practical knowledge that comes from working in a full-time position, such as research assistant or assistant museum curator. Being immersed in the job is an effective way to evaluate various career options available to researchers while practicing hands-on skills, such as designing exhibits and processing and preserving artifacts. These roles also provide opportunities to apply broader skills developed through academic work, such as writing research reports, using technology resources, and analyzing data.

Step 3: Earn a Doctorate Degree

Researchers who wish to pursue an advanced specialization may enter a doctoral program in history, particularly if their goal is a research position in academia or with a federal government agency. Specializations typically represent a particular country or region; a period of time; or a specific subfield, such as political, cultural, or social history. Colleges and universities often fill teaching positions with people who hold a master’s degree and are pursuing a doctoral degree.

Earn a Master of Arts in History Degree

Norwich University offers an online Master of Arts in History program focused on meeting the needs of today’s historians. Norwich’s program can prepare students to think like researchers with an insatiable historical curiosity and unyielding desire to ask why. Through the 18-month program, individuals can gain in-depth knowledge of historical topics, as well as advanced writing, research, analytical, and presentation skills. The program offers four concentrations―Public History, American History, World History, and Legal and Constitutional History―allowing students to tailor their studies to their interests and goals.

Explore how Norwich’s online Master of Arts in History degree can help you learn how to become a history researcher and prepare you for a successful career in the field.

How Historians Work , National Council on Public History Career Resources , American Historical Association What Does a Historian Do? , CareerExplorer Archivists, Curators, and Museum Workers , U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Anthropologists and Archeologists , U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Postsecondary Teachers , U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Historians , U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Operations Research Analysts , U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Average Intelligence Analyst Salary at Federal Bureau of Investigation , PayScale Intelligence Analysts , FBI Who We Are , Naval History and Heritage Command Supervisory Staff Curator (Museum Management) , USAJOBS Research Skills for the Future: Summary and Critique of a Comparative Study in Eight Countries , Journal of Research Practice Postsecondary Teachers , U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Where Historians Work: An Interactive Database of History PhD Career Outcomes , American Historical Association Challenges for History Doctoral Programs and Students: Rising Admissions and High Attrition , American Historical Association A (Very) Brief History of the Master’s Degree , American Historical Association Master of Arts (MA), History Degree , PayScale

Explore Norwich University

Your future starts here.

- 30+ On-Campus Undergraduate Programs

- 16:1 Student-Faculty Ratio

- 25+ Online Grad and Undergrad Programs

- Military Discounts Available

- 22 Varsity Athletic Teams

Future Leader Camp

Join us for our challenging military-style summer camp where we will inspire you to push beyond what you thought possible:

- Session I July 13 - 21, 2024

- Session II July 27 - August 4, 2024

Explore your sense of adventure, have fun, and forge new friendships. High school students and incoming rooks, discover the leader you aspire to be – today.

- Bodleian Libraries

- Oxford LibGuides

- Research training for historians

History: Research training for historians

- Guides to History collections

- History Thesis Fair for Undergraduates

- Keeping up-to-date

Use this page to find out about information skills resources and courses relevant to History and allied fields. These may be courses offered locally or outside Oxford, most notably the Institute of Historical Research ( more ), The British Library ( more ) or The National Archives TNA ( more ).

History students and research can make use of a wide range of information skills courses, workshops and events.

Information skills training for historians

Radcliffe Camera staff offer tailored courses and events to historians at various times of the year. They include:

- Library inductions & tours ( more on this - History Faculty Canvas)

- Finding resources for your UG thesis: Bodleian Libraries’ research skills (more on this - History Faculty Canvas)

- 1-1 sessions with the History Librarian. Students: email the History Librarian (Teaching) ; reseachers & DPhil: email the History Librarian (Research) .

- Act-on-Acceptance and Open Access briefings ( email the History Librarian (Research)

Bodleian iSkills - Workshops in Information Discovery & Scholarly Communications

This programme is designed to help you to make effective use of scholarly materials. We cover

- Information discovery and searching for scholarly materials

- Endnote, RefWorks, Zotero and Mendeley for managing references and formatting footnotes and bibliographies

- Keeping up to date with new research

- Measuring research impact

- Understanding copyright and looking after your intellectual property

- Open Access publishing and complying with funder mandates for open access

- Managing your research data

The art of deciphering handwriting: some palaeographic resources online

- English Handwriting 1500-1700: an online course

- Palaeography: reading old handwriting 1500 - 1800: A practical online tutorial

- Scottish Handwriting.com

- German script tutorial

Check out more palaeographic sources bookmarked on HFL Diigo .

Institute of Historical Research - research training

Each year they run an extensive programme of training in historical research skills for professional historians, independent researchers, and early career scholars.

Courses vary in length from one day to one term, and cover a variety of subjects from language learning to digital research practices.

The National Archives: Postgraduate archival skills training (PAST)

- Introduction to archival research (Level 1) . Aimed at 3rd year undergraduates and postgraduate students.

- Skills and methodology workshops (Level 2) . Aimed at taught postgraduates and DPhil students, covering particular topics or periods.

- Record workshops (Level 3) . Aimed at DPhil students and early career researchers

See their website for further details and sign up to their newletter to receive information about upcoming PAST sessions.

Need to brush up your Français? Have to learn Deutsch?

The University's Language Centre has a lot to offer for historians wishing to upgrade their language skills or, quite simply, start learning a language. There are a variety of regular Languages for All courses for all skill ranges.

They also have a lending library encouraging self-learning with a lot of language learning resources for 180 languages, including books and CDs, a very nice film collection and satellite television available in several languages. They also encourage online learning.

And finally, they have a successful language exchange programme which allows you to speak with native speakers.

IT Services offers a great range of courses which are useful to historians. These include managing images or using Word effectively for your dissertation.

Students and researchers also have access to Self-service learning which is a huge library of online, video based, courses covering a wide range of software and IT related topics.

1-1 with a History Librarian

Students: email the History Librarian (Teaching) ;

Reseachers & DPhil: email the History Librarian (Research) .

You can find details of Bodleian Libraries' subject specialists online for other areas.

Making Maps: self-teaching resources from the Bodleian Map Department

There are tutorials for ArcGIS Desktop and QGIS.

More assistance in learning how to find, use or create maps is available from staff in the Bodleian Library's Map Department .

Gough Maps Oxfordshire 12 (1751) from Digital.Bodleian .

- << Previous: History Thesis Fair for Undergraduates

- Next: Keeping up-to-date >>

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 4:55 PM

- URL: https://libguides.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/history

Website feedback

Accessibility Statement - https://visit.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/accessibility

Google Analytics - Bodleian Libraries use Google Analytics cookies on this web site. Google Analytics anonymously tracks individual visitor behaviour on this web site so that we can see how LibGuides is being used. We only use this information for monitoring and improving our websites and content for the benefit of our users (you). You can opt out of Google Analytics cookies completely (from all websites) by visiting https://tools.google.com/dlpage/gaoptout

© Bodleian Libraries 2021. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

- Privacy Policy

Home » Historian – Definition, Types, Work Area

Historian – Definition, Types, Work Area

Table of Contents

Definition:

Historian is a person who studies and writes about the past, with an emphasis on interpreting and understanding historical events, processes, and phenomena. Historians use a wide range of sources, such as written documents, oral histories, artifacts, and archaeological evidence, to reconstruct and analyze the past.

Their work often involves researching and analyzing primary sources, evaluating conflicting evidence, and developing arguments and theories about historical events and trends. Historians play a crucial role in helping us understand the complex social, political, economic, and cultural forces that have shaped human societies over time.

Types of Historian

Types of Historian are as follows:

- Academic Historians: These are historians who work in universities or other academic institutions. They conduct research, write scholarly articles and books, and teach courses in history. Academic historians often specialize in a particular area or time period of history.

- Public Historians: These are historians who work outside of academia and are focused on making history accessible to the public. They may work in museums, historical societies, or government agencies, and their work may involve creating exhibits, leading tours, or conducting public lectures.

- Social Historians: These are historians who study the lives of ordinary people, focusing on issues such as class, gender, race, and ethnicity. They are interested in the social, cultural, and economic forces that shape society and how they have changed over time.

- Political Historians: These are historians who focus on political events and movements, such as wars, revolutions, and political leaders. They analyze the motivations, decisions, and actions of political actors and how they have affected society and the world.

- Economic Historians : These are historians who study economic systems and how they have evolved over time. They are interested in issues such as trade, capitalism, and economic growth, and how these factors have influenced historical events.

- Environmental Historians: These are historians who study the interactions between humans and the natural environment. They are interested in issues such as climate change, deforestation, and pollution, and how these factors have affected historical events and societies.

- Oral Historians: These are historians who specialize in collecting and analyzing oral histories, or first-person accounts of historical events from people who experienced them. They use interviews and other oral sources to build a more complete picture of history from the perspective of those who lived it.

- Cultural Historians : These are historians who focus on the study of culture, including art, literature, music, religion, and other forms of expression. They analyze how cultural values and beliefs have influenced historical events and how these forms of expression have changed over time.

- Military Historians: These are historians who specialize in the study of warfare and military history. They examine the strategies, tactics, and technology used in different historical conflicts and how they have influenced the outcome of wars and the development of military technology.

- Intellectual Historians : These are historians who focus on the study of ideas and the intellectual history of societies. They analyze the evolution of ideas and theories in different fields such as philosophy, science, and politics, and how these ideas have shaped historical events.

- Gender Historians : These are historians who focus on the study of gender roles and identities throughout history. They analyze how gender has influenced historical events and how ideas about gender have changed over time.

- Digital Historians: These are historians who use digital tools and methods to research and analyze historical data. They may use data visualization, computational analysis, or other digital techniques to uncover new insights and patterns in historical data.

- Public Memory Historians : These are historians who focus on how societies remember and commemorate historical events. They analyze the ways in which different groups remember and interpret events, and how these memories influence contemporary politics and social issues.

- Global Historians: These are historians who focus on the interconnectedness of world events and how different regions and societies have influenced each other over time. They are interested in global processes such as imperialism, colonization, migration, and globalization and how these processes have shaped historical events.

- Environmental Historians: These are historians who study the relationships between humans and the natural world throughout history. They are interested in how natural resources have been used, how humans have impacted the environment, and how environmental factors have influenced historical events.

- Legal Historians: These are historians who specialize in the study of law and legal systems throughout history. They analyze how legal systems have evolved over time and how legal decisions have impacted social and political developments.

- Archaeologists: These are historians who study past societies through material remains such as artifacts, structures, and landscapes. They use methods such as excavation, analysis of artifacts, and remote sensing to reconstruct the lives and activities of past societies.

- Religious Historians: These are historians who focus on the study of religion throughout history. They analyze how different religious traditions have influenced historical events and how religious beliefs and practices have changed over time.

- Oral Tradition Historians: These are historians who specialize in the study of oral traditions and folklore. They analyze how stories, legends, and myths have been transmitted over time and how they reflect the beliefs and values of different societies.

- Medical Historians: These are historians who focus on the study of medicine and health throughout history. They analyze the development of medical practices and how they have been influenced by social, cultural, and political factors. They also examine the impact of disease and public health issues on historical events and societies.

Historian Examples

There are many examples of historians who have made significant contributions to the study and understanding of history. Here are just a few examples:

- Herodotus (c. 484 – 425 BCE): Known as the “Father of History,” Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who wrote a comprehensive account of the Greco-Persian Wars.

- Thucydides (c. 460 – 400 BCE): Another ancient Greek historian, Thucydides wrote the History of the Peloponnesian War, a detailed account of the conflict between Athens and Sparta.

- Ibn Khaldun (1332 – 1406 CE): A Muslim historian and philosopher from North Africa, Ibn Khaldun wrote the Muqaddimah, an influential work on the philosophy of history.

- William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616 CE): Although primarily known as a playwright, Shakespeare was also a historian who used historical events and figures as the basis for many of his plays.

- Edward Gibbon (1737 – 1794 CE): An English historian, Gibbon wrote The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, a comprehensive account of the fall of the Roman Empire.

- Fernand Braudel (1902 – 1985 CE): A French historian, Braudel was a pioneer in the field of world history and wrote extensively on the economic, social, and cultural forces that have shaped human history.

- Howard Zinn (1922 – 2010 CE): An American historian and social activist, Zinn wrote A People’s History of the United States, which focused on the experiences of ordinary people throughout American history.

- Yuval Noah Harari (born 1976 CE): An Israeli historian, Harari is known for his best-selling books Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind and Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, which explore the history and future of humanity.

What Do Historians Do?

Here are some of the specific activities that historians engage in:

- Research : Historians spend a great deal of time conducting research on the events, people, and cultures they are interested in. They collect and analyze primary sources such as letters, diaries, newspapers, government documents, and other written materials.

- Interpretation : Once historians have gathered information, they interpret and analyze it to create a narrative or explanation of the past. They try to make sense of the information they have gathered and create a coherent story that explains why certain events happened and what their significance was.

- Writing : Historians write books, articles, and other works that present their research and interpretation of the past. They use their writing to communicate their findings to other scholars and to the general public.

- Teaching : Many historians also teach at colleges and universities, where they share their knowledge and expertise with students.

- Preservation : Historians work to preserve and protect historical artifacts and sites. They may work with museums, archives, and historical societies to ensure that important historical documents and objects are properly cared for and made available to the public.

- Consulting : Historians may also be called upon to provide their expertise in legal cases or government policy decisions that involve historical issues.

What Skills Must a Historian Have?

Historians require a broad range of skills and abilities to excel in their profession. Some of the key skills that historians need include:

- Research skills: Historians must have strong research skills to identify, locate, and analyze relevant historical sources.

- Critical thinking skills: Historians must be able to evaluate historical evidence critically, discerning the strengths and weaknesses of different sources, and identifying biases and inaccuracies.

- Analytical skills: Historians must be able to analyze complex historical data and events, discern patterns and trends, and draw meaningful conclusions.

- Communication skills: Historians must be able to communicate their findings effectively, both verbally and in writing. This includes being able to craft clear and concise arguments, present data in a compelling way, and write engaging narratives.

- Language skills: Historians may need to be proficient in multiple languages to be able to read and interpret historical sources from different regions and time periods.

- Technological skills : Historians must be able to use technology to facilitate research, analysis, and communication. This includes being proficient in digital research tools and methods, as well as using software for data analysis and visualization.

- Interdisciplinary knowledge: Historians must have a broad understanding of multiple disciplines, including economics, political science, sociology, and anthropology, to contextualize historical events and draw meaningful conclusions.

Where Historians Work

Historians work in a variety of settings, including:

- Universities and colleges: Many historians work in academic institutions, teaching courses on history, conducting research, and publishing scholarly works.

- Museums and archives : Historians may work in museums or archives, where they manage collections of historical artifacts, documents, and other materials, and conduct research on these collections.

- Government agencies: Historians may work for government agencies, such as the National Park Service or the Smithsonian Institution, conducting research and providing historical expertise for public programs and exhibits.

- Non-profit organizations: Historians may work for non-profit organizations, such as historical societies or preservation groups, where they conduct research, provide historical expertise, and advocate for the preservation of historical sites and artifacts.

- Private companies: Some historians may work for private companies, such as consulting firms or media outlets, where they provide historical expertise and research for various projects.

- Freelance: Some historians work as freelance writers, researchers, or consultants, providing historical expertise for a variety of clients and projects.

How to Become A Historian

To become a historian, you typically need to follow these steps:

- Obtain a bachelor’s degree: Most historians have a bachelor’s degree in history or a related field. You can also major in a related discipline, such as anthropology, archaeology, or political science, but you will likely need to take several history courses to build a solid foundation in the subject.

- Consider a graduate degree: While a bachelor’s degree is sufficient for some entry-level jobs, most historians have a graduate degree in history or a related field. A master’s degree can provide a more in-depth education in historical research and analysis, while a Ph.D. can lead to academic and research positions.

- Gain experience: While in school, try to gain experience through internships, research assistantships, or volunteer work at museums, archives, or historical societies. This can help you build practical skills and make connections in the field.

- Develop specialized expertise : As you progress in your education and career, consider developing specialized expertise in a particular area of history, such as a specific time period, region, or theme. This can help you stand out in a competitive job market and may lead to more specialized positions.

- Network: Attend conferences and events in the field to meet other historians, build relationships, and learn about job opportunities. You can also join professional organizations such as the American Historical Association or the Organization of American Historians to connect with other professionals in the field.