- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write the Rationale of the Study in Research (Examples)

What is the Rationale of the Study?

The rationale of the study is the justification for taking on a given study. It explains the reason the study was conducted or should be conducted. This means the study rationale should explain to the reader or examiner why the study is/was necessary. It is also sometimes called the “purpose” or “justification” of a study. While this is not difficult to grasp in itself, you might wonder how the rationale of the study is different from your research question or from the statement of the problem of your study, and how it fits into the rest of your thesis or research paper.

The rationale of the study links the background of the study to your specific research question and justifies the need for the latter on the basis of the former. In brief, you first provide and discuss existing data on the topic, and then you tell the reader, based on the background evidence you just presented, where you identified gaps or issues and why you think it is important to address those. The problem statement, lastly, is the formulation of the specific research question you choose to investigate, following logically from your rationale, and the approach you are planning to use to do that.

Table of Contents:

How to write a rationale for a research paper , how do you justify the need for a research study.

- Study Rationale Example: Where Does It Go In Your Paper?

The basis for writing a research rationale is preliminary data or a clear description of an observation. If you are doing basic/theoretical research, then a literature review will help you identify gaps in current knowledge. In applied/practical research, you base your rationale on an existing issue with a certain process (e.g., vaccine proof registration) or practice (e.g., patient treatment) that is well documented and needs to be addressed. By presenting the reader with earlier evidence or observations, you can (and have to) convince them that you are not just repeating what other people have already done or said and that your ideas are not coming out of thin air.

Once you have explained where you are coming from, you should justify the need for doing additional research–this is essentially the rationale of your study. Finally, when you have convinced the reader of the purpose of your work, you can end your introduction section with the statement of the problem of your research that contains clear aims and objectives and also briefly describes (and justifies) your methodological approach.

When is the Rationale for Research Written?

The author can present the study rationale both before and after the research is conducted.

- Before conducting research : The study rationale is a central component of the research proposal . It represents the plan of your work, constructed before the study is actually executed.

- Once research has been conducted : After the study is completed, the rationale is presented in a research article or PhD dissertation to explain why you focused on this specific research question. When writing the study rationale for this purpose, the author should link the rationale of the research to the aims and outcomes of the study.

What to Include in the Study Rationale

Although every study rationale is different and discusses different specific elements of a study’s method or approach, there are some elements that should be included to write a good rationale. Make sure to touch on the following:

- A summary of conclusions from your review of the relevant literature

- What is currently unknown (gaps in knowledge)

- Inconclusive or contested results from previous studies on the same or similar topic

- The necessity to improve or build on previous research, such as to improve methodology or utilize newer techniques and/or technologies

There are different types of limitations that you can use to justify the need for your study. In applied/practical research, the justification for investigating something is always that an existing process/practice has a problem or is not satisfactory. Let’s say, for example, that people in a certain country/city/community commonly complain about hospital care on weekends (not enough staff, not enough attention, no decisions being made), but you looked into it and realized that nobody ever investigated whether these perceived problems are actually based on objective shortages/non-availabilities of care or whether the lower numbers of patients who are treated during weekends are commensurate with the provided services.

In this case, “lack of data” is your justification for digging deeper into the problem. Or, if it is obvious that there is a shortage of staff and provided services on weekends, you could decide to investigate which of the usual procedures are skipped during weekends as a result and what the negative consequences are.

In basic/theoretical research, lack of knowledge is of course a common and accepted justification for additional research—but make sure that it is not your only motivation. “Nobody has ever done this” is only a convincing reason for a study if you explain to the reader why you think we should know more about this specific phenomenon. If there is earlier research but you think it has limitations, then those can usually be classified into “methodological”, “contextual”, and “conceptual” limitations. To identify such limitations, you can ask specific questions and let those questions guide you when you explain to the reader why your study was necessary:

Methodological limitations

- Did earlier studies try but failed to measure/identify a specific phenomenon?

- Was earlier research based on incorrect conceptualizations of variables?

- Were earlier studies based on questionable operationalizations of key concepts?

- Did earlier studies use questionable or inappropriate research designs?

Contextual limitations

- Have recent changes in the studied problem made previous studies irrelevant?

- Are you studying a new/particular context that previous findings do not apply to?

Conceptual limitations

- Do previous findings only make sense within a specific framework or ideology?

Study Rationale Examples

Let’s look at an example from one of our earlier articles on the statement of the problem to clarify how your rationale fits into your introduction section. This is a very short introduction for a practical research study on the challenges of online learning. Your introduction might be much longer (especially the context/background section), and this example does not contain any sources (which you will have to provide for all claims you make and all earlier studies you cite)—but please pay attention to how the background presentation , rationale, and problem statement blend into each other in a logical way so that the reader can follow and has no reason to question your motivation or the foundation of your research.

Background presentation

Since the beginning of the Covid pandemic, most educational institutions around the world have transitioned to a fully online study model, at least during peak times of infections and social distancing measures. This transition has not been easy and even two years into the pandemic, problems with online teaching and studying persist (reference needed) .

While the increasing gap between those with access to technology and equipment and those without access has been determined to be one of the main challenges (reference needed) , others claim that online learning offers more opportunities for many students by breaking down barriers of location and distance (reference needed) .

Rationale of the study

Since teachers and students cannot wait for circumstances to go back to normal, the measures that schools and universities have implemented during the last two years, their advantages and disadvantages, and the impact of those measures on students’ progress, satisfaction, and well-being need to be understood so that improvements can be made and demographics that have been left behind can receive the support they need as soon as possible.

Statement of the problem

To identify what changes in the learning environment were considered the most challenging and how those changes relate to a variety of student outcome measures, we conducted surveys and interviews among teachers and students at ten institutions of higher education in four different major cities, two in the US (New York and Chicago), one in South Korea (Seoul), and one in the UK (London). Responses were analyzed with a focus on different student demographics and how they might have been affected differently by the current situation.

How long is a study rationale?

In a research article bound for journal publication, your rationale should not be longer than a few sentences (no longer than one brief paragraph). A dissertation or thesis usually allows for a longer description; depending on the length and nature of your document, this could be up to a couple of paragraphs in length. A completely novel or unconventional approach might warrant a longer and more detailed justification than an approach that slightly deviates from well-established methods and approaches.

Consider Using Professional Academic Editing Services

Now that you know how to write the rationale of the study for a research proposal or paper, you should make use of our free AI grammar checker , Wordvice AI, or receive professional academic proofreading services from Wordvice, including research paper editing services and manuscript editing services to polish your submitted research documents.

You can also find many more articles, for example on writing the other parts of your research paper , on choosing a title , or on making sure you understand and adhere to the author instructions before you submit to a journal, on the Wordvice academic resources pages.

How to Write the Rationale for a Research Paper

- Research Process

- Peer Review

A research rationale answers the big SO WHAT? that every adviser, peer reviewer, and editor has in mind when they critique your work. A compelling research rationale increases the chances of your paper being published or your grant proposal being funded. In this article, we look at the purpose of a research rationale, its components and key characteristics, and how to create an effective research rationale.

Updated on September 19, 2022

The rationale for your research is the reason why you decided to conduct the study in the first place. The motivation for asking the question. The knowledge gap. This is often the most significant part of your publication. It justifies the study's purpose, novelty, and significance for science or society. It's a critical part of standard research articles as well as funding proposals.

Essentially, the research rationale answers the big SO WHAT? that every (good) adviser, peer reviewer, and editor has in mind when they critique your work.

A compelling research rationale increases the chances of your paper being published or your grant proposal being funded. In this article, we look at:

- the purpose of a research rationale

- its components and key characteristics

- how to create an effective research rationale

What is a research rationale?

Think of a research rationale as a set of reasons that explain why a study is necessary and important based on its background. It's also known as the justification of the study, rationale, or thesis statement.

Essentially, you want to convince your reader that you're not reciting what other people have already said and that your opinion hasn't appeared out of thin air. You've done the background reading and identified a knowledge gap that this rationale now explains.

A research rationale is usually written toward the end of the introduction. You'll see this section clearly in high-impact-factor international journals like Nature and Science. At the end of the introduction there's always a phrase that begins with something like, "here we show..." or "in this paper we show..." This text is part of a logical sequence of information, typically (but not necessarily) provided in this order:

Here's an example from a study by Cataldo et al. (2021) on the impact of social media on teenagers' lives.

Note how the research background, gap, rationale, and objectives logically blend into each other.

The authors chose to put the research aims before the rationale. This is not a problem though. They still achieve a logical sequence. This helps the reader follow their thinking and convinces them about their research's foundation.

Elements of a research rationale

We saw that the research rationale follows logically from the research background and literature review/observation and leads into your study's aims and objectives.

This might sound somewhat abstract. A helpful way to formulate a research rationale is to answer the question, “Why is this study necessary and important?”

Generally, that something has never been done before should not be your only motivation. Use it only If you can give the reader valid evidence why we should learn more about this specific phenomenon.

A well-written introduction covers three key elements:

- What's the background to the research?

- What has been done before (information relevant to this particular study, but NOT a literature review)?

- Research rationale

Now, let's see how you might answer the question.

1. This study complements scientific knowledge and understanding

Discuss the shortcomings of previous studies and explain how'll correct them. Your short review can identify:

- Methodological limitations . The methodology (research design, research approach or sampling) employed in previous works is somewhat flawed.

Example : Here , the authors claim that previous studies have failed to explore the role of apathy “as a predictor of functional decline in healthy older adults” (Burhan et al., 2021). At the same time, we know a lot about other age-related neuropsychiatric disorders, like depression.

Their study is necessary, then, “to increase our understanding of the cognitive, clinical, and neural correlates of apathy and deconstruct its underlying mechanisms.” (Burhan et al., 2021).

- Contextual limitations . External factors have changed and this has minimized or removed the relevance of previous research.

Example : You want to do an empirical study to evaluate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of tourists visiting Sicily. Previous studies might have measured tourism determinants in Sicily, but they preceded COVID-19.

- Conceptual limitations . Previous studies are too bound to a specific ideology or a theoretical framework.

Example : The work of English novelist E. M. Forster has been extensively researched for its social, political, and aesthetic dimensions. After the 1990s, younger scholars wanted to read his novels as an example of gay fiction. They justified the need to do so based on previous studies' reliance on homophobic ideology.

This kind of rationale is most common in basic/theoretical research.

2. This study can help solve a specific problem

Here, you base your rationale on a process that has a problem or is not satisfactory.

For example, patients complain about low-quality hospital care on weekends (staff shortages, inadequate attention, etc.). No one has looked into this (there is a lack of data). So, you explore if the reported problems are true and what can be done to address them. This is a knowledge gap.

Or you set out to explore a specific practice. You might want to study the pros and cons of several entry strategies into the Japanese food market.

It's vital to explain the problem in detail and stress the practical benefits of its solution. In the first example, the practical implications are recommendations to improve healthcare provision.

In the second example, the impact of your research is to inform the decision-making of businesses wanting to enter the Japanese food market.

This kind of rationale is more common in applied/practical research.

3. You're the best person to conduct this study

It's a bonus if you can show that you're uniquely positioned to deliver this study, especially if you're writing a funding proposal .

For an anthropologist wanting to explore gender norms in Ethiopia, this could be that they speak Amharic (Ethiopia's official language) and have already lived in the country for a few years (ethnographic experience).

Or if you want to conduct an interdisciplinary research project, consider partnering up with collaborators whose expertise complements your own. Scientists from different fields might bring different skills and a fresh perspective or have access to the latest tech and equipment. Teaming up with reputable collaborators justifies the need for a study by increasing its credibility and likely impact.

When is the research rationale written?

You can write your research rationale before, or after, conducting the study.

In the first case, when you might have a new research idea, and you're applying for funding to implement it.

Or you're preparing a call for papers for a journal special issue or a conference. Here , for instance, the authors seek to collect studies on the impact of apathy on age-related neuropsychiatric disorders.

In the second case, you have completed the study and are writing a research paper for publication. Looking back, you explain why you did the study in question and how it worked out.

Although the research rationale is part of the introduction, it's best to write it at the end. Stand back from your study and look at it in the big picture. At this point, it's easier to convince your reader why your study was both necessary and important.

How long should a research rationale be?

The length of the research rationale is not fixed. Ideally, this will be determined by the guidelines (of your journal, sponsor etc.).

The prestigious journal Nature , for instance, calls for articles to be no more than 6 or 8 pages, depending on the content. The introduction should be around 200 words, and, as mentioned, two to three sentences serve as a brief account of the background and rationale of the study, and come at the end of the introduction.

If you're not provided guidelines, consider these factors:

- Research document : In a thesis or book-length study, the research rationale will be longer than in a journal article. For example, the background and rationale of this book exploring the collective memory of World War I cover more than ten pages.

- Research question : Research into a new sub-field may call for a longer or more detailed justification than a study that plugs a gap in literature.

Which verb tenses to use in the research rationale?

It's best to use the present tense. Though in a research proposal, the research rationale is likely written in the future tense, as you're describing the intended or expected outcomes of the research project (the gaps it will fill, the problems it will solve).

Example of a research rationale

Research question : What are the teachers' perceptions of how a sense of European identity is developed and what underlies such perceptions?

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology , 3(2), 77-101.

Burhan, A.M., Yang, J., & Inagawa, T. (2021). Impact of apathy on aging and age-related neuropsychiatric disorders. Research Topic. Frontiers in Psychiatry

Cataldo, I., Lepri, B., Neoh, M. J. Y., & Esposito, G. (2021). Social media usage and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence: A review. Frontiers in Psychiatry , 11.

CiCe Jean Monnet Network (2017). Guidelines for citizenship education in school: Identities and European citizenship children's identity and citizenship in Europe.

Cohen, l, Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education . Eighth edition. London: Routledge.

de Prat, R. C. (2013). Euroscepticism, Europhobia and Eurocriticism: The radical parties of the right and left “vis-à-vis” the European Union P.I.E-Peter Lang S.A., Éditions Scientifiques Internationales.

European Commission. (2017). Eurydice Brief: Citizenship education at school in Europe.

Polyakova, A., & Fligstein, N. (2016). Is European integration causing Europe to become more nationalist? Evidence from the 2007–9 financial crisis. Journal of European Public Policy , 23(1), 60-83.

Winter, J. (2014). Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

How do you Write the Rationale for Research?

- By DiscoverPhDs

- October 21, 2020

What is the Rationale of Research?

The term rationale of research means the reason for performing the research study in question. In writing your rational you should able to convey why there was a need for your study to be carried out. It’s an important part of your research paper that should explain how your research was novel and explain why it was significant; this helps the reader understand why your research question needed to be addressed in your research paper, term paper or other research report.

The rationale for research is also sometimes referred to as the justification for the study. When writing your rational, first begin by introducing and explaining what other researchers have published on within your research field.

Having explained the work of previous literature and prior research, include discussion about where the gaps in knowledge are in your field. Use these to define potential research questions that need answering and explain the importance of addressing these unanswered questions.

The rationale conveys to the reader of your publication exactly why your research topic was needed and why it was significant . Having defined your research rationale, you would then go on to define your hypothesis and your research objectives.

Final Comments

Defining the rationale research, is a key part of the research process and academic writing in any research project. You use this in your research paper to firstly explain the research problem within your dissertation topic. This gives you the research justification you need to define your research question and what the expected outcomes may be.

Thinking about applying to a PhD? Then don’t miss out on these 4 tips on how to best prepare your application.

This post gives you the best questions to ask at a PhD interview, to help you work out if your potential supervisor and lab is a good fit for you.

The term rationale of research means the reason for performing the research study in question.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

Starting your PhD can feel like a daunting, exciting and special time. They’ll be so much to think about – here are a few tips to help you get started.

Multistage sampling is a more complex form of cluster sampling for obtaining sample populations. Learn their pros and cons and how to undertake them.

Dr Ilesanmi has a PhD in Applied Biochemistry from the Federal University of Technology Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. He is now a lecturer in the Department of Biochemistry at the Federal University Otuoke, Bayelsa State, Nigeria.

Ryan is in the final write up stages of his PhD at the University of Southampton. His research is on understanding narrative structure, media specificity and genre in transmedia storytelling.

Join Thousands of Students

Setting Rationale in Research: Cracking the code for excelling at research

Knowledge and curiosity lays the foundation of scientific progress. The quest for knowledge has always been a timeless endeavor. Scholars seek reasons to explain the phenomena they observe, paving way for development of research. Every investigation should offer clarity and a well-defined rationale in research is a cornerstone upon which the entire study can be built.

Research rationale is the heartbeat of every academic pursuit as it guides the researchers to unlock the untouched areas of their field. Additionally, it illuminates the gaps in the existing knowledge, and identifies the potential contributions that the study aims to make.

Table of Contents

What Is Research Rationale and When Is It Written

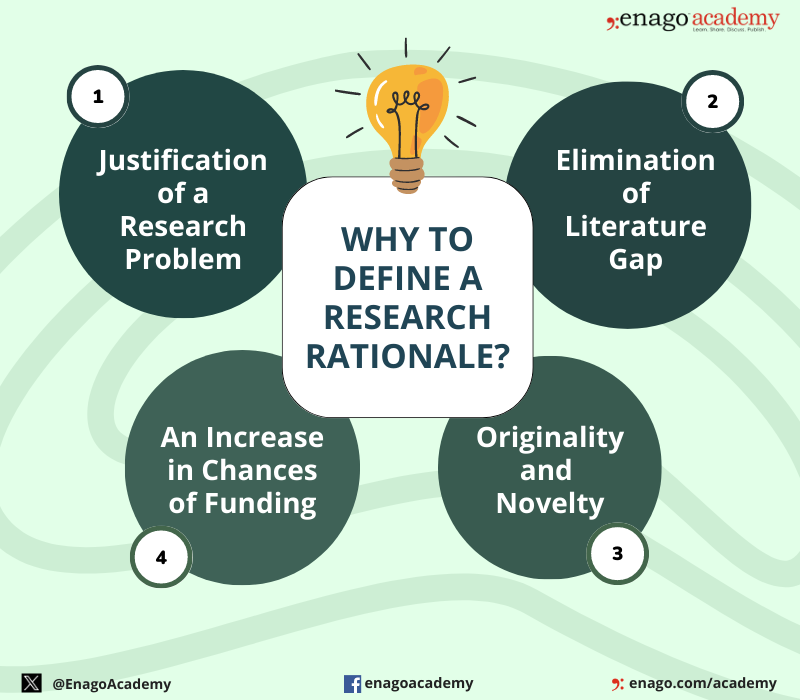

Research rationale is the “why” behind every academic research. It not only frames the study but also outlines its objectives , questions, and expected outcomes. Additionally, it helps to identify the potential limitations of the study . It serves as a lighthouse for researchers that guides through data collection and analysis, ensuring their efforts remain focused and purposeful. Typically, a rationale is written at the beginning of the research proposal or research paper . It is an essential component of the introduction section and provides the foundation for the entire study. Furthermore, it provides a clear understanding of the purpose and significance of the research to the readers before delving into the specific details of the study. In some cases, the rationale is written before the methodology, data analysis, and other sections. Also, it serves as the justification for the research, and how it contributes to the field. Defining a research rationale can help a researcher in following ways:

1. Justification of a Research Problem

- Research rationale helps to understand the essence of a research problem.

- It designs the right approach to solve a problem. This aspect is particularly important for applied research, where the outcomes can have real-world relevance and impact.

- Also, it explains why the study is worth conducting and why resources should be allocated to pursue it.

- Additionally, it guides a researcher to highlight the benefits and implications of a strategy.

2. Elimination of Literature Gap

- Research rationale helps to ideate new topics which are less addressed.

- Additionally, it offers fresh perspectives on existing research and discusses the shortcomings in previous studies.

- It shows that your study aims to contribute to filling these gaps and advancing the field’s understanding.

3. Originality and Novelty

- The rationale highlights the unique aspects of your research and how it differs from previous studies.

- Furthermore, it explains why your research adds something new to the field and how it expands upon existing knowledge.

- It highlights how your findings might contribute to a better understanding of a particular issue or problem and potentially lead to positive changes.

- Besides these benefits, it provides a personal motivation to the researchers. In some cases, researchers might have personal experiences or interests that drive their desire to investigate a particular topic.

4. An Increase in Chances of Funding

- It is essential to convince funding agencies , supervisors, or reviewers, that a research is worth pursuing.

- Therefore, a good rationale can get your research approved for funding and increases your chances of getting published in journals; as it addresses the potential knowledge gap in existing research.

Overall, research rationale is essential for providing a clear and convincing argument for the value and importance of your research study, setting the stage for the rest of the research proposal or manuscript. Furthermore, it helps establish the context for your work and enables others to understand the purpose and potential impact of your research.

5 Key Elements of a Research Rationale

Research rationale must include certain components which make it more impactful. Here are the key elements of a research rationale:

By incorporating these elements, you provide a strong and convincing case for the legitimacy of your research, which is essential for gaining support and approval from academic institutions, funding agencies, or other stakeholders.

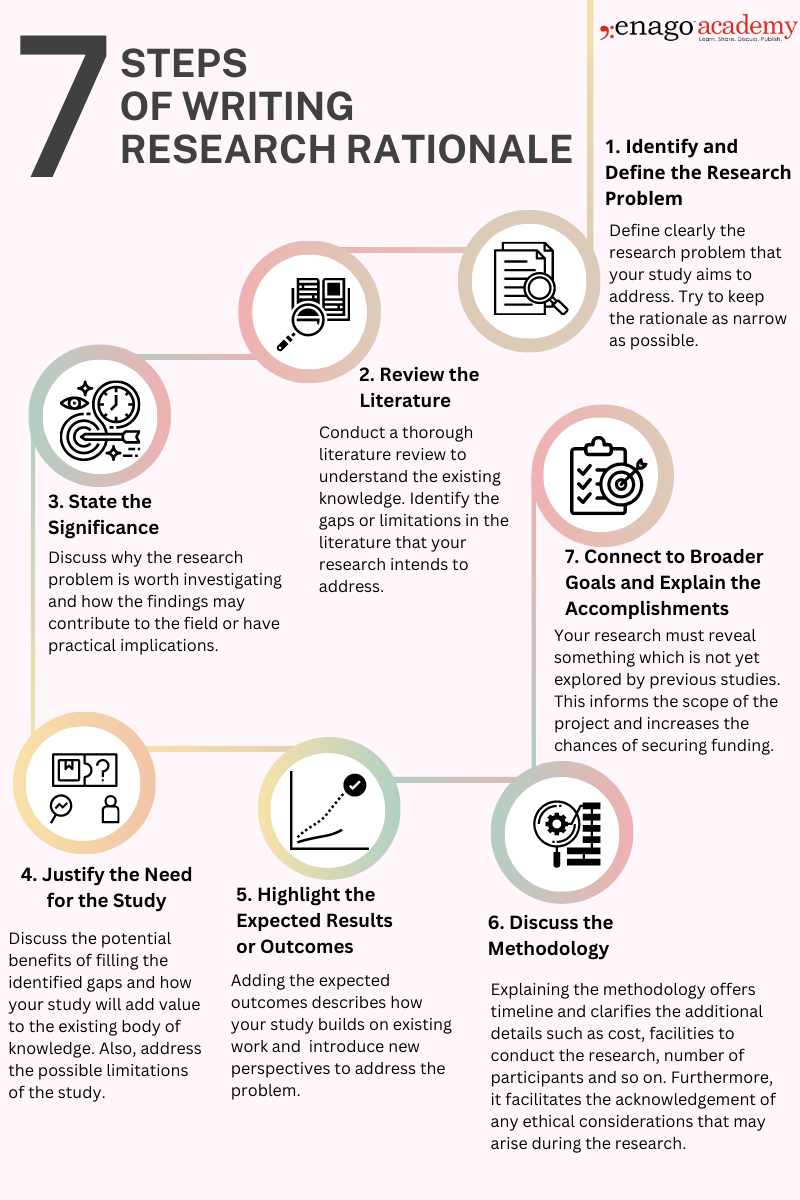

How to Write a Rationale in Research

Writing a rationale requires careful consideration of the reasons for conducting the study. It is usually written in the present tense.

Here are some steps to guide you through the process of writing a research rationale:

After writing the initial draft, it is essential to review and revise the research rationale to ensure that it effectively communicates the purpose of your research. The research rationale should be persuasive and compelling, convincing readers that your study is worthwhile and deserves their attention.

How Long Should a Research Rationale be?

Although there is no pre-defined length for a rationale in research, its length may vary depending on the specific requirements of the research project. It also depends on the academic institution or organization, and the guidelines set by the research advisor or funding agency. In general, a research rationale is usually a concise and focused document.

Typically, it ranges from a few paragraphs to a few pages, but it is usually recommended to keep it as crisp as possible while ensuring all the essential elements are adequately covered. The length of a research rationale can be roughly as follows:

1. For Research Proposal:

A. Around 1 to 3 pages

B. Ensure clear and comprehensive explanation of the research question, its significance, literature review , and methodological approach.

2. Thesis or Dissertation:

A. Around 3 to 5 pages

B. Ensure an extensive coverage of the literature review, theoretical framework, and research objectives to provide a robust justification for the study.

3. Journal Article:

A. Usually concise. Ranges from few paragraphs to one page

B. The research rationale is typically included as part of the introduction section

However, remember that the quality and content of the research rationale are more important than its length. The reasons for conducting the research should be well-structured, clear, and persuasive when presented. Always adhere to the specific institution or publication guidelines.

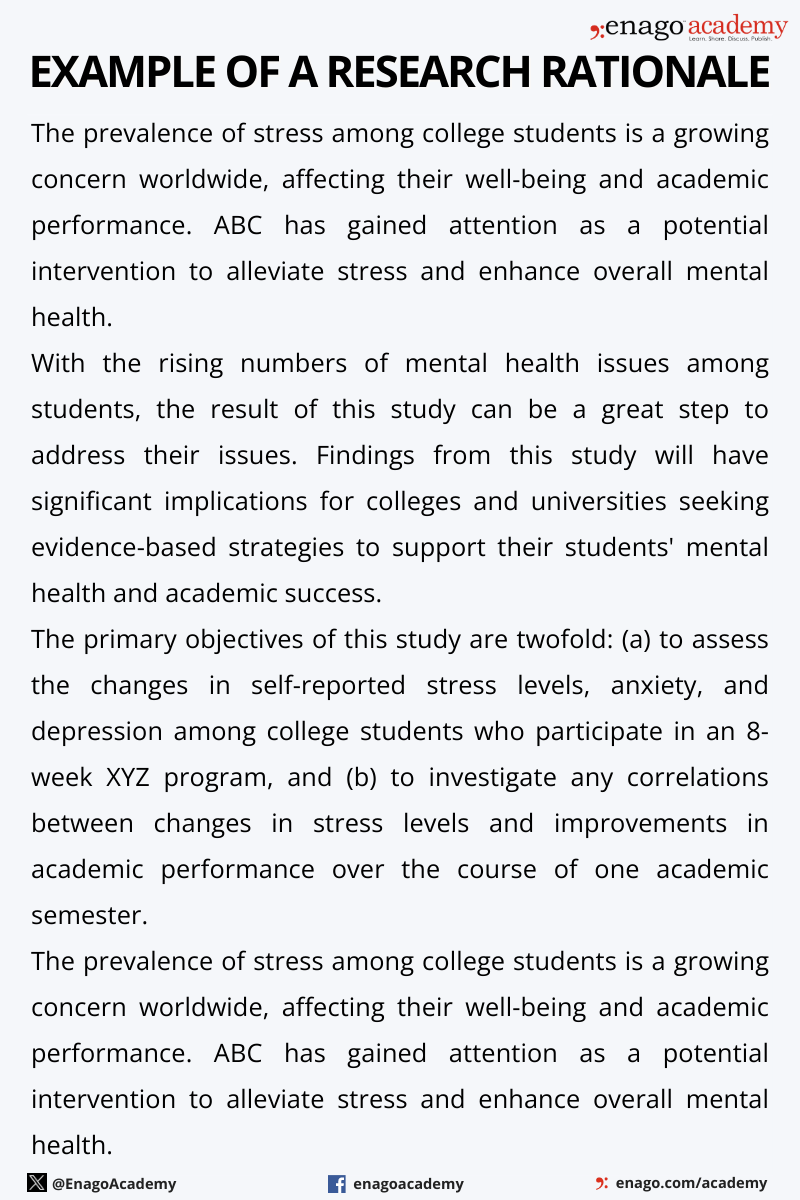

Example of a Research Rationale

In conclusion, the research rationale serves as the cornerstone of a well-designed and successful research project. It ensures that research efforts are focused, meaningful, and ethically sound. Additionally, it provides a comprehensive and logical justification for embarking on a specific investigation. Therefore, by identifying research gaps, defining clear objectives, emphasizing significance, explaining the chosen methodology, addressing ethical considerations, and recognizing potential limitations, researchers can lay the groundwork for impactful and valuable contributions to the scientific community.

So, are you ready to delve deeper into the world of research and hone your academic writing skills? Explore Enago Academy ‘s comprehensive resources and courses to elevate your research and make a lasting impact in your field. Also, share your thoughts and experiences in the form of an article or a thought piece on Enago Academy’s Open Platform .

Join us on a journey of scholarly excellence today!

Frequently Asked Questions

A rationale of the study can be written by including the following points: 1. Background of the Research/ Study 2. Identifying the Knowledge Gap 3. An Overview of the Goals and Objectives of the Study 4. Methodology and its Significance 5. Relevance of the Research

Start writing a research rationale by defining the research problem and discussing the literature gap associated with it.

A research rationale can be ended by discussing the expected results and summarizing the need of the study.

A rationale for thesis can be made by covering the following points: 1. Extensive coverage of the existing literature 2. Explaining the knowledge gap 3. Provide the framework and objectives of the study 4. Provide a robust justification for the study/ research 5. Highlight the potential of the research and the expected outcomes

A rationale for dissertation can be made by covering the following points: 1. Highlight the existing reference 2. Bridge the gap and establish the context of your research 3. Describe the problem and the objectives 4. Give an overview of the methodology

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

![sample rationale for thesis proposal What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Mitigating Survivorship Bias in Scholarly Research: 10 tips to enhance data integrity

The Power of Proofreading: Taking your academic work to the next level

Facing Difficulty Writing an Academic Essay? — Here is your one-stop solution!

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

We use cookies on this site to enhance your experience

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

A link to reset your password has been sent to your email.

Back to login

We need additional information from you. Please complete your profile first before placing your order.

Thank you. payment completed., you will receive an email from us to confirm your registration, please click the link in the email to activate your account., there was error during payment, orcid profile found in public registry, download history, how to write the rationale for your research.

- Charlesworth Author Services

- 19 November, 2021

The rationale for one’s research is the justification for undertaking a given study. It states the reason(s) why a researcher chooses to focus on the topic in question, including what the significance is and what gaps the research intends to fill. In short, it is an explanation that rationalises the need for the study. The rationale is typically followed by a hypothesis/ research question (s) and the study objectives.

When is the rationale for research written?

The rationale of a study can be presented both before and after the research is conducted.

- Before : The rationale is a crucial part of your research proposal , representing the plan of your work as formulated before you execute your study.

- After : Once the study is completed, the rationale is presented in a research paper or dissertation to explain why you focused on the particular question. In this instance, you would link the rationale of your research project to the study aims and outcomes.

Basis for writing the research rationale

The study rationale is predominantly based on preliminary data . A literature review will help you identify gaps in the current knowledge base and also ensure that you avoid duplicating what has already been done. You can then formulate the justification for your study from the existing literature on the subject and the perceived outcomes of the proposed study.

Length of the research rationale

In a research proposal or research article, the rationale would not take up more than a few sentences . A thesis or dissertation would allow for a longer description, which could even run into a couple of paragraphs . The length might even depend on the field of study or nature of the experiment. For instance, a completely novel or unconventional approach might warrant a longer and more detailed justification.

Basic elements of the research rationale

Every research rationale should include some mention or discussion of the following:

- An overview of your conclusions from your literature review

- Gaps in current knowledge

- Inconclusive or controversial findings from previous studies

- The need to build on previous research (e.g. unanswered questions, the need to update concepts in light of new findings and/or new technical advancements).

Example of a research rationale

Note: This uses a fictional study.

Abc xyz is a newly identified microalgal species isolated from fish tanks. While Abc xyz algal blooms have been seen as a threat to pisciculture, some studies have hinted at their unusually high carotenoid content and unique carotenoid profile. Carotenoid profiling has been carried out only in a handful of microalgal species from this genus, and the search for microalgae rich in bioactive carotenoids has not yielded promising candidates so far. This in-depth examination of the carotenoid profile of Abc xyz will help identify and quantify novel and potentially useful carotenoids from an untapped aquaculture resource .

In conclusion

It is important to describe the rationale of your research in order to put the significance and novelty of your specific research project into perspective. Once you have successfully articulated the reason(s) for your research, you will have convinced readers of the importance of your work!

Maximise your publication success with Charlesworth Author Services.

Charlesworth Author Services , a trusted brand supporting the world’s leading academic publishers, institutions and authors since 1928.

To know more about our services, visit: Our Services

Share with your colleagues

Related articles.

How to identify Gaps in research and determine your original research topic

Charlesworth Author Services 14/09/2021 00:00:00

Tips for designing your Research Question

Charlesworth Author Services 01/08/2017 00:00:00

Why and How to do a literature search

Charlesworth Author Services 17/08/2020 00:00:00

Related webinars

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication - Module 1: Know when are you ready to write

Charlesworth Author Services 04/03/2021 00:00:00

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication- Module 3: Understand the structure of an academic paper

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication: Module 4: Prepare to write your academic paper

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication: Module 5: Conduct a Literature Review

Article sections.

How to write an Introduction to an academic article

Writing a strong Methods section

Charlesworth Author Services 12/03/2021 00:00:00

Strategies for writing the Results section in a scientific paper

Charlesworth Author Services 27/10/2021 00:00:00

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Academic Proposals

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource introduces the genre of academic proposals and provides strategies for developing effective graduate-level proposals across multiple contexts.

Introduction

An important part of the work completed in academia is sharing our scholarship with others. Such communication takes place when we present at scholarly conferences, publish in peer-reviewed journals, and publish in books. This OWL resource addresses the steps in writing for a variety of academic proposals.

For samples of academic proposals, click here .

Important considerations for the writing process

First and foremost, you need to consider your future audience carefully in order to determine both how specific your topic can be and how much background information you need to provide in your proposal. While some conferences and journals may be subject-specific, most will require you to address an audience that does not conduct research on the same topics as you. Conference proposal reviewers are often drawn from professional organization members or other attendees, while journal proposals are typically reviewed by the editorial staff, so you need to ensure that your proposal is geared toward the knowledge base and expectations of whichever audience will read your work.

Along those lines, you might want to check whether you are basing your research on specific prior research and terminology that requires further explanation. As a rule, always phrase your proposal clearly and specifically, avoid over-the-top phrasing and jargon, but do not negate your own personal writing style in the process.

If you would like to add a quotation to your proposal, you are not required to provide a citation or footnote of the source, although it is generally preferred to mention the author’s name. Always put quotes in quotation marks and take care to limit yourself to at most one or two quotations in the entire proposal text. Furthermore, you should always proofread your proposal carefully and check whether you have integrated details, such as author’s name, the correct number of words, year of publication, etc. correctly.

Methodology is often a key factor in the evaluation of proposals for any academic genre — but most proposals have such a small word limit that writers find it difficult to adequately include methods while also discussing their argument, background for the study, results, and contributions to knowledge. It's important to make sure that you include some information about the methods used in your study, even if it's just a line or two; if your proposal isn't experimental in nature, this space should instead describe the theory, lens, or approach you are taking to arrive at your conclusions.

Reasons proposals fail/common pitfalls

There are common pitfalls that you might need to improve on for future proposals.

The proposal does not reflect your enthusiasm and persuasiveness, which usually goes hand in hand with hastily written, simply worded proposals. Generally, the better your research has been, the more familiar you are with the subject and the more smoothly your proposal will come together.

Similarly, proposing a topic that is too broad can harm your chances of being accepted to a conference. Be sure to have a clear focus in your proposal. Usually, this can be avoided by more advanced research to determine what has already been done, especially if the proposal is judged by an important scholar in the field. Check the names of keynote speakers and other attendees of note to avoid repeating known information or not focusing your proposal.

Your paper might simply have lacked the clear language that proposals should contain. On this linguistic level, your proposal might have sounded repetitious, have had boring wording, or simply displayed carelessness and a lack of proofreading, all of which can be remedied by more revisions. One key tactic for ensuring you have clear language in your proposal is signposting — you can pick up key phrases from the CFP, as well as use language that indicates different sections in academic work (as in IMRAD sections from the organization and structure page in this resource). This way, reviewers can easily follow your proposal and identify its relatedness to work in the field and the CFP.

Conference proposals

Conference proposals are a common genre in graduate school that invite several considerations for writing depending on the conference and requirements of the call for papers.

Beginning the process

Make sure you read the call for papers carefully to consider the deadline and orient your topic of presentation around the buzzwords and themes listed in the document. You should take special note of the deadline and submit prior to that date, as most conferences use online submission systems that will close on a deadline and will not accept further submissions.

If you have previously spoken on or submitted a proposal on the same topic, you should carefully adjust it specifically for this conference or even completely rewrite the proposal based on your changing and evolving research.

The topic you are proposing should be one that you can cover easily within a time frame of approximately fifteen to twenty minutes. You should stick to the required word limit of the conference call. The organizers have to read a large number of proposals, especially in the case of an international or interdisciplinary conference, and will appreciate your brevity.

Structure and components

Conference proposals differ widely across fields and even among individual conferences in a field. Some just request an abstract, which is written similarly to any other abstract you'd write for a journal article or other publication. Some may request abstracts or full papers that fit into pre-existing sessions created by conference organizers. Some request both an abstract and a further description or proposal, usually in cases where the abstract will be published in the conference program and the proposal helps organizers decide which papers they will accept.

If the conference you are submitting to requires a proposal or description, there are some common elements you'll usually need to include. These are a statement of the problem or topic, a discussion of your approach to the problem/topic, a discussion of findings or expected findings, and a discussion of key takeaways or relevance to audience members. These elements are typically given in this order and loosely follow the IMRAD structure discussed in the organization and structure page in this resource.

The proportional size of each of these elements in relation to one another tends to vary by the stage of your research and the relationship of your topic to the field of the conference. If your research is very early on, you may spend almost no time on findings, because you don't have them yet. Similarly, if your topic is a regular feature at conferences in your field, you may not need to spend as much time introducing it or explaining its relevance to the field; however, if you are working on a newer topic or bringing in a topic or problem from another discipline, you may need to spend slightly more space explaining it to reviewers. These decisions should usually be based on an analysis of your audience — what information can reviewers be reasonably expected to know, and what will you have to tell them?

Journal Proposals

Most of the time, when you submit an article to a journal for publication, you'll submit a finished manuscript which contains an abstract, the text of the article, the bibliography, any appendices, and author bios. These can be on any topic that relates to the journal's scope of interest, and they are accepted year-round.

Special issues , however, are planned issues of a journal that center around a specific theme, usually a "hot topic" in the field. The editor or guest editors for the special issue will often solicit proposals with a call for papers (CFP) first, accept a certain number of proposals for further development into article manuscripts, and then accept the final articles for the special issue from that smaller pool. Special issues are typically the only time when you will need to submit a proposal to write a journal article, rather than submitting a completed manuscript.

Journal proposals share many qualities with conference proposals: you need to write for your audience, convey the significance of your work, and condense the various sections of a full study into a small word or page limit. In general, the necessary components of a proposal include:

- Problem or topic statement that defines the subject of your work (often includes research questions)

- Background information (think literature review) that indicates the topic's importance in your field as well as indicates that your research adds something to the scholarship on this topic

- Methodology and methods used in the study (and an indication of why these methods are the correct ones for your research questions)

- Results or findings (which can be tentative or preliminary, if the study has not yet been completed)

- Significance and implications of the study (what will readers learn? why should they care?)

This order is a common one because it loosely follows the IMRAD (introduction, methods, results and discussion) structure often used in academic writing; however, it is not the only possible structure or even always the best structure. You may need to move these elements around depending on the expectations in your field, the word or page limit, or the instructions given in the CFP.

Some of the unique considerations of journal proposals are:

- The CFP may ask you for an abstract, a proposal, or both. If you need to write an abstract, look for more information on the abstract page. If you need to write both an abstract and a proposal, make sure to clarify for yourself what the difference is. Usually the proposal needs to include more information about the significance, methods, and/or background of the study than will fit in the abstract, but often the CFP itself will give you some instructions as to what information the editors are wanting in each piece of writing.

- Journal special issue CFPs, like conference CFPs, often include a list of topics or questions that describe the scope of the special issue. These questions or topics are a good starting place for generating a proposal or tying in your research; ensuring that your work is a good fit for the special issue and articulating why that is in the proposal increases your chances of being accepted.

- Special issues are not less valuable or important than regularly scheduled issues; therefore, your proposal needs to show that your work fits and could readily be accepted in any other issue of the journal. This means following some of the same practices you would if you were preparing to submit a manuscript to a journal: reading the journal's author submission guidelines; reading the last several years of the journal to understand the usual topics, organization, and methods; citing pieces from this journal and other closely related journals in your research.

Book Proposals

While the requirements are very similar to those of conference proposals, proposals for a book ought to address a few other issues.

General considerations

Since these proposals are of greater length, the publisher will require you to delve into greater detail as well—for instance, regarding the organization of the proposed book or article.

Publishers generally require a clear outline of the chapters you are proposing and an explication of their content, which can be several pages long in its entirety.

You will need to incorporate knowledge of relevant literature, use headings and sub-headings that you should not use in conference proposals. Be sure to know who wrote what about your topic and area of interest, even if you are proposing a less scholarly project.

Publishers prefer depth rather than width when it comes to your topic, so you should be as focused as possible and further outline your intended audience.

You should always include information regarding your proposed deadlines for the project and how you will execute this plan, especially in the sciences. Potential investors or publishers need to know that you have a clear and efficient plan to accomplish your proposed goals. Depending on the subject area, this information can also include a proposed budget, materials or machines required to execute this project, and information about its industrial application.

Pre-writing strategies

As John Boswell (cited in: Larsen, Michael. How to Write a Book Proposal. Writers Digest Books , 2004. p. 1) explains, “today fully 90 percent of all nonfiction books sold to trade publishers are acquired on the basis of a proposal alone.” Therefore, editors and agents generally do not accept completed manuscripts for publication, as these “cannot (be) put into the usual channels for making a sale”, since they “lack answers to questions of marketing, competition, and production.” (Lyon, Elizabeth. Nonfiction Book Proposals Anybody Can Write . Perigee Trade, 2002. pp. 6-7.)

In contrast to conference or, to a lesser degree, chapter proposals, a book proposal introduces your qualifications for writing it and compares your work to what others have done or failed to address in the past.

As a result, you should test the idea with your networks and, if possible, acquire other people’s proposals that discuss similar issues or have a similar format before submitting your proposal. Prior to your submission, it is recommended that you write at least part of the manuscript in addition to checking the competition and reading all about the topic.

The following is a list of questions to ask yourself before committing to a book project, but should in no way deter you from taking on a challenging project (adapted from Lyon 27). Depending on your field of study, some of these might be more relevant to you than others, but nonetheless useful to reiterate and pose to yourself.

- Do you have sufficient enthusiasm for a project that may span years?

- Will publication of your book satisfy your long-term career goals?

- Do you have enough material for such a long project and do you have the background knowledge and qualifications required for it?

- Is your book idea better than or different from other books on the subject? Does the idea spark enthusiasm not just in yourself but others in your field, friends, or prospective readers?

- Are you willing to acquire any lacking skills, such as, writing style, specific terminology and knowledge on that field for this project? Will it fit into your career and life at the time or will you not have the time to engage in such extensive research?

Essential elements of a book proposal

Your book proposal should include the following elements:

- Your proposal requires the consideration of the timing and potential for sale as well as its potential for subsidiary rights.

- It needs to include an outline of approximately one paragraph to one page of prose (Larsen 6) as well as one sample chapter to showcase the style and quality of your writing.

- You should also include the resources you need for the completion of the book and a biographical statement (“About the Author”).

- Your proposal must contain your credentials and expertise, preferably from previous publications on similar issues.

- A book proposal also provides you with the opportunity to include information such as a mission statement, a foreword by another authority, or special features—for instance, humor, anecdotes, illustrations, sidebars, etc.

- You must assess your ability to promote the book and know the market that you target in all its statistics.

The following proposal structure, as outlined by Peter E. Dunn for thesis and fellowship proposals, provides a useful guide to composing such a long proposal (Dunn, Peter E. “Proposal Writing.” Center for Instructional Excellence, Purdue University, 2007):

- Literature Review

- Identification of Problem

- Statement of Objectives

- Rationale and Significance

- Methods and Timeline

- Literature Cited

Most proposals for manuscripts range from thirty to fifty pages and, apart from the subject hook, book information (length, title, selling handle), markets for your book, and the section about the author, all the other sections are optional. Always anticipate and answer as many questions by editors as possible, however.

Finally, include the best chapter possible to represent your book's focus and style. Until an agent or editor advises you to do otherwise, follow your book proposal exactly without including something that you might not want to be part of the book or improvise on possible expected recommendations.

Publishers expect to acquire the book's primary rights, so that they can sell it in an adapted or condensed form as well. Mentioning any subsidiary rights, such as translation opportunities, performance and merchandising rights, or first-serial rights, will add to the editor's interest in buying your book. It is enticing to publishers to mention your manuscript's potential to turn into a series of books, although they might still hesitate to buy it right away—at least until the first one has been a successful endeavor.

The sample chapter

Since editors generally expect to see about one-tenth of a book, your sample chapter's length should reflect that in these building blocks of your book. The chapter should reflect your excitement and the freshness of the idea as well as surprise editors, but do not submit part of one or more chapters. Always send a chapter unless your credentials are impeccable due to prior publications on the subject. Do not repeat information in the sample chapter that will be covered by preceding or following ones, as the outline should be designed in such a way as to enable editors to understand the context already.

How to make your proposal stand out

Depending on the subject of your book, it is advisable to include illustrations that exemplify your vision of the book and can be included in the sample chapter. While these can make the book more expensive, it also increases the salability of the project. Further, you might consider including outstanding samples of your published work, such as clips from periodicals, if they are well-respected in the field. Thirdly, cover art can give your potential publisher a feel for your book and its marketability, especially if your topic is creative or related to the arts.

In addition, professionally formatting your materials will give you an edge over sloppy proposals. Proofread the materials carefully, use consistent and carefully organized fonts, spacing, etc., and submit your proposal without staples; rather, submit it in a neat portfolio that allows easy access and reassembling. However, check the submission guidelines first, as most proposals are submitted digitally. Finally, you should try to surprise editors and attract their attention. Your hook, however, should be imaginative but inexpensive (you do not want to bribe them, after all). Make sure your hook draws the editors to your book proposal immediately (Adapted from Larsen 154-60).

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on 14 February 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 11 November 2022.

A dissertation proposal describes the research you want to do: what it’s about, how you’ll conduct it, and why it’s worthwhile. You will probably have to write a proposal before starting your dissertation as an undergraduate or postgraduate student.

A dissertation proposal should generally include:

- An introduction to your topic and aims

- A literature review of the current state of knowledge

- An outline of your proposed methodology

- A discussion of the possible implications of the research

- A bibliography of relevant sources

Dissertation proposals vary a lot in terms of length and structure, so make sure to follow any guidelines given to you by your institution, and check with your supervisor when you’re unsure.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Step 1: coming up with an idea, step 2: presenting your idea in the introduction, step 3: exploring related research in the literature review, step 4: describing your methodology, step 5: outlining the potential implications of your research, step 6: creating a reference list or bibliography.

Before writing your proposal, it’s important to come up with a strong idea for your dissertation.

Find an area of your field that interests you and do some preliminary reading in that area. What are the key concerns of other researchers? What do they suggest as areas for further research, and what strikes you personally as an interesting gap in the field?

Once you have an idea, consider how to narrow it down and the best way to frame it. Don’t be too ambitious or too vague – a dissertation topic needs to be specific enough to be feasible. Move from a broad field of interest to a specific niche:

- Russian literature 19th century Russian literature The novels of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky

- Social media Mental health effects of social media Influence of social media on young adults suffering from anxiety

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Like most academic texts, a dissertation proposal begins with an introduction . This is where you introduce the topic of your research, provide some background, and most importantly, present your aim , objectives and research question(s) .

Try to dive straight into your chosen topic: What’s at stake in your research? Why is it interesting? Don’t spend too long on generalisations or grand statements:

- Social media is the most important technological trend of the 21st century. It has changed the world and influences our lives every day.

- Psychologists generally agree that the ubiquity of social media in the lives of young adults today has a profound impact on their mental health. However, the exact nature of this impact needs further investigation.

Once your area of research is clear, you can present more background and context. What does the reader need to know to understand your proposed questions? What’s the current state of research on this topic, and what will your dissertation contribute to the field?

If you’re including a literature review, you don’t need to go into too much detail at this point, but give the reader a general sense of the debates that you’re intervening in.

This leads you into the most important part of the introduction: your aim, objectives and research question(s) . These should be clearly identifiable and stand out from the text – for example, you could present them using bullet points or bold font.

Make sure that your research questions are specific and workable – something you can reasonably answer within the scope of your dissertation. Avoid being too broad or having too many different questions. Remember that your goal in a dissertation proposal is to convince the reader that your research is valuable and feasible:

- Does social media harm mental health?

- What is the impact of daily social media use on 18– to 25–year–olds suffering from general anxiety disorder?

Now that your topic is clear, it’s time to explore existing research covering similar ideas. This is important because it shows you what is missing from other research in the field and ensures that you’re not asking a question someone else has already answered.

You’ve probably already done some preliminary reading, but now that your topic is more clearly defined, you need to thoroughly analyse and evaluate the most relevant sources in your literature review .

Here you should summarise the findings of other researchers and comment on gaps and problems in their studies. There may be a lot of research to cover, so make effective use of paraphrasing to write concisely:

- Smith and Prakash state that ‘our results indicate a 25% decrease in the incidence of mechanical failure after the new formula was applied’.

- Smith and Prakash’s formula reduced mechanical failures by 25%.

The point is to identify findings and theories that will influence your own research, but also to highlight gaps and limitations in previous research which your dissertation can address:

- Subsequent research has failed to replicate this result, however, suggesting a flaw in Smith and Prakash’s methods. It is likely that the failure resulted from…

Next, you’ll describe your proposed methodology : the specific things you hope to do, the structure of your research and the methods that you will use to gather and analyse data.

You should get quite specific in this section – you need to convince your supervisor that you’ve thought through your approach to the research and can realistically carry it out. This section will look quite different, and vary in length, depending on your field of study.

You may be engaged in more empirical research, focusing on data collection and discovering new information, or more theoretical research, attempting to develop a new conceptual model or add nuance to an existing one.

Dissertation research often involves both, but the content of your methodology section will vary according to how important each approach is to your dissertation.

Empirical research

Empirical research involves collecting new data and analysing it in order to answer your research questions. It can be quantitative (focused on numbers), qualitative (focused on words and meanings), or a combination of both.

With empirical research, it’s important to describe in detail how you plan to collect your data:

- Will you use surveys ? A lab experiment ? Interviews?

- What variables will you measure?

- How will you select a representative sample ?

- If other people will participate in your research, what measures will you take to ensure they are treated ethically?

- What tools (conceptual and physical) will you use, and why?

It’s appropriate to cite other research here. When you need to justify your choice of a particular research method or tool, for example, you can cite a text describing the advantages and appropriate usage of that method.

Don’t overdo this, though; you don’t need to reiterate the whole theoretical literature, just what’s relevant to the choices you have made.

Moreover, your research will necessarily involve analysing the data after you have collected it. Though you don’t know yet what the data will look like, it’s important to know what you’re looking for and indicate what methods (e.g. statistical tests , thematic analysis ) you will use.

Theoretical research

You can also do theoretical research that doesn’t involve original data collection. In this case, your methodology section will focus more on the theory you plan to work with in your dissertation: relevant conceptual models and the approach you intend to take.

For example, a literary analysis dissertation rarely involves collecting new data, but it’s still necessary to explain the theoretical approach that will be taken to the text(s) under discussion, as well as which parts of the text(s) you will focus on:

- This dissertation will utilise Foucault’s theory of panopticism to explore the theme of surveillance in Orwell’s 1984 and Kafka’s The Trial…

Here, you may refer to the same theorists you have already discussed in the literature review. In this case, the emphasis is placed on how you plan to use their contributions in your own research.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

You’ll usually conclude your dissertation proposal with a section discussing what you expect your research to achieve.

You obviously can’t be too sure: you don’t know yet what your results and conclusions will be. Instead, you should describe the projected implications and contribution to knowledge of your dissertation.

First, consider the potential implications of your research. Will you:

- Develop or test a theory?

- Provide new information to governments or businesses?

- Challenge a commonly held belief?

- Suggest an improvement to a specific process?

Describe the intended result of your research and the theoretical or practical impact it will have:

Finally, it’s sensible to conclude by briefly restating the contribution to knowledge you hope to make: the specific question(s) you hope to answer and the gap the answer(s) will fill in existing knowledge:

Like any academic text, it’s important that your dissertation proposal effectively references all the sources you have used. You need to include a properly formatted reference list or bibliography at the end of your proposal.

Different institutions recommend different styles of referencing – commonly used styles include Harvard , Vancouver , APA , or MHRA . If your department does not have specific requirements, choose a style and apply it consistently.

A reference list includes only the sources that you cited in your proposal. A bibliography is slightly different: it can include every source you consulted in preparing the proposal, even if you didn’t mention it in the text. In the case of a dissertation proposal, a bibliography may also list relevant sources that you haven’t yet read, but that you intend to use during the research itself.

Check with your supervisor what type of bibliography or reference list you should include.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, November 11). How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved 26 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, what is a dissertation | 5 essential questions to get started, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

- AI Content Shield

- AI KW Research

- AI Assistant

- SEO Optimizer

- AI KW Clustering

- Customer reviews

- The NLO Revolution

- Press Center

- Help Center

- Content Resources

- Facebook Group

How to Write the Rationale for a Research Proposal

Table of Contents

Writing a research proposal can be intimidating, especially when you are expected to explain the rationale behind your project. This article will help you learn how to write the rationale for a research proposal to provide justification for why it should be pursued. A good rationale should give readers an understanding of why your project is worth undertaking and how it will contribute to existing knowledge. It should outline any practical implications that could come from your work. By thoroughly preparing this section of your proposal , you will increase the chances of having your research approved.

What Is a Rationale in Research?

A research rationale provides a detailed explanation of why a study is necessary and should be carried out. It convinces the reader or examiner of the importance of the research by outlining its relevance, significance, and potential contribution to existing knowledge. Additionally, it helps transition from the research problem to the methods used in the study, connecting both elements into one comprehensive argument. The research rationale justifies why the researcher chose to conduct this particular study over any other possible alternative studies.

Why Is a Research Rationale Important?

A well-written rationale can help demonstrate your commitment to the project. It can convince reviewers that you have put thought into developing a high-quality research plan. When composing this section, focus on the scientific merit of your proposed study by providing clear and concise reasons for conducting the research. Your goal is to communicate the potential benefits of your project and show that you understand its limitations. Include sufficient detail about the methods you plan to use, any ethical considerations to consider, and how you will evaluate your results. Explaining why your research is important and necessary is essential for getting approval from funding bodies or academic institutions. Your rationale should provide a convincing argument for why the project needs to be conducted. The rationale must make it clear that there are potential benefits that justify its costs. Consider the broader impact of your work and describe how it could contribute to furthering knowledge in the field.

The rationale for research is also known as the justification of the study. Make a mention of the following points while writing the rationale for a research proposal:

Background on All Previous Research on the Subject of Your Study

It is important to include background information on what research has already been done on the study topic. This will help to build a foundation for understanding the current knowledge, open questions, and gaps.

The Open Questions of the Study

Highlighting the open questions related to the study topic helps to identify potential areas for further exploration. It gives readers an understanding of where new research could be helpful. It is essential to state these questions to have clear objectives and goals for the research proposal.

Identify the Gaps in Literature

Identifying literature gaps helps highlight areas that have not yet been studied. This provides the opportunity to add new information and understanding to the field. By including these points in the rationale, the writer can showcase how his work will contribute to existing research.

Highlight the Significance of Addressing These Gaps

Emphasizing why it is important to address those gaps is vital in any research proposal. It allows readers to understand why this particular project needs to be undertaken. By clearly outlining why addressing these gaps is crucial, the writer can successfully argue why his proposed project should be given consideration.

A rationale for a research proposal can help convince the reader of the importance and relevance of your study. This article explains the importance of a rationale and discusses the key elements to learn how to write the rationale for a research proposal . Following these tips will let you create a powerful research rationale that will help convince others of the value of your project.

Abir Ghenaiet

Abir is a data analyst and researcher. Among her interests are artificial intelligence, machine learning, and natural language processing. As a humanitarian and educator, she actively supports women in tech and promotes diversity.

Explore All Proposal Generator Articles

Creative terms and conditions agreement in business proposal.

In business, proposals are essential for securing contracts and agreements with clients. However, a proposal is only complete with terms…

- Proposal Generator

Free guide to a statement of proposal sample

A statement of proposal is a document that outlines a proposed project or initiative in detail. It is typically used…

Free Proposal Letter for Training and Development for a Head Start

Training and development are essential to improve employees’ skills, knowledge, and productivity. A well-crafted training proposal can help an organization…