6 Work-Life Balance Tips for PhD Students

To keep up to date, or follow our social media, the author of this post:.

Jayron Habibe

A finishing PhD students in Medical Biochemistry. He has a love for writing about practical tools that make life as a PhD student just a little bit easier. Learn more about Jayron

Posts recommended by Jayron:

The Best Project Management Methods for Researchers and Academics

What Is Project Management And Why Do You Need It Project management methods are the

The Art of Efficient Note Taking: Strategies to Excel in Your Academic Journey

Why is Note Taking Important for Academics? Note taking is a skill that lies at

How to Stop Procrastinating: A Guide for PhD Students and Academics

🧠Introduction As a PhD student or academic, you are well aware of the unique challenges

Join our Team!

Support us.

6 Work-life Balance Tips for PhD Students

“failure may make you miserable but i’m not sure success will make you happy” – chris williamson (host of the modern wisdom podcast).

I think balance in anything is always good however when it comes to obtaining work-life balance achieving it is going to depend on your individual needs and circumstances.

On the surface, the term is self-explanatory and sounds great. Especially when it can reduce symptoms of fatigue, help lower stress levels and increase our work and life satisfaction.

Who wouldn’t want to achieve a good, healthy, and sustainable harmony between their career and the rest of their life?

Exactly! …Supervisors!

JK of course😉

But in all seriousness, while we all know what work-life balance is it can be quite difficult to achieve so with that said here are 6 tips that will hopefully help you in achieving said balance and making sure to prioritize all the things you deem important!

Ultimately this list will probably contain some things you don’t care about at all or things that are of vital importance to you. Feel free to pick and choose which tips resonate with you and try them out. The goal after all is to get closer to a balanced state for us and everyone’s definition of that might differ.

Here are 6 tips to help you get closer to your ideal work-life balance

Tip #1. start saying no more often .

You won’t have this option for everything but it’s important to start exercising your “no muscles” before they atrophy and you are spread too thin. Maybe this means that some experiments will take longer or you will have to pass up going to a conference here and there but in the long run prioritizing your mental health and your health is more important.

This is one of the things I struggle with a lot myself as I’m quite a people pleaser and I often feel like I’m letting people down if I say no but sometimes you just have to. For my fellow people-pleasers out there, It helps to think of it as you want to give people your best and you can only do that if you are focused, energized, and happy. If you are unfocused, tired, and depressed then you aren’t going to be much help to the latest person asking you for something anyway so you’re better off just being direct and honest with no. In the end, it’s the best thing you can do for both you and them.

Tip #2. Schedule regular breaks

The best of both worlds, you get to be productive and still take breaks, all while eliminating the feeling of guilt associated with procrastination! I like this one because it’s easy to do and there are ways of doing it while still being very productive. The Pomodoro technique is one such method and it involves setting a timer and focussing on work for 25 mins then taking a 5 min break and rinse and repeat.

I use it myself for my writing sessions or for doing stuff related to the podcast and it works while taking the stress off of having to make a ton of progress when you start something. By scheduling regular breaks we get to still make progress in a way that accounts for us being human and needing breaks every once in a while. While on these breaks make sure to do something that you enjoy and that energizes you, whether that’s going for a short walk or getting a cup of coffee, or talking with a colleague, doesn’t matter just do you.

Tip #3. Take care of your health

Your health is your number one asset in life. As long as you are healthy you have options but as soon as you aren’t those options evaporate quickly. Now just to be clear here I’m not suggesting you get a gym membership and go 3-5x week or start running marathons but just to put your health at the forefront of your mind and your schedule. Whatever that looks like for you is fine, especially at the beginning when exercising or eating healthy sucks the most. Some low-cost, high-leverage things you can start doing to take better care of your health include prioritizing getting enough sleep every night, drinking more water, going out for more walks, and reducing junk food consumption. You’d be surprised at how effective doing the simple things consistently over time is compared to doing hard things rarely. Here is a quote I love that explains this well.

“It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent.”- Charlie Munger

P.S. I am not a registered physician so my advice is not medical advice at all but if you somehow manage to fail at drinking water and getting enough sleep then you have no one but yourself to blame for that.

Tip #4. Making time for family and friends

While it might often seem like time is scarce and it probably is, you do have it in your power to block off time for the things like friends and family. An example of this could be that every Friday evening is Dungeons and Dragons night with your friends ( Yes I’m nerdy) and you won’t miss that for any work-related event whether that’s a conference or anything else. Time blocking isn’t free of course as it ties in quite well with saying no. You’re just choosing to say no to everything that conflicts with your predefined time with friends and family.

Tip #5. Setting healthy boundaries between work and life

Boundaries are important, especially in academia where work never ends and there is constantly some new paper to read, experiment to do, or project to finish. Having clearly defined boundaries helps you focus your attention better and be actively engaged with either your work or your relationships. A good example of doing this well is not responding to work emails during the weekend or after working hours. Another often used tip for setting boundaries, especially on holidays is to enable the automatic response to emails saying you are on holiday and cannot / will not respond to emails for the duration of your holiday.

Tip #6. Start practicing self-compassion/mindfulness

I’m not saying this to add one more thing to your to-do list but rather to help you clear your mind and reflect and accept the situation you’re in and the emotions you are feeling. Let’s face it, life is hard, and doing a PhD doesn’t make it any easier. Not everything is going to always go our way and we need to accept that and be ready for that both mentally and emotionally.

Having said this, you don’t need to start journaling and meditating for 1hr a day from now of course. Instead, test some meditating for 5-10 mins a day or journaling how your day went or what you are grateful for. The way I think of these things is that our mind needs a moment to unload all the work and life-related things we have going on and just relax for a second. Sort of like running a diagnostic check on your computer and closing background apps that are slowing it down. Overall it’s good for your performance and mental health to have a moment of introspection whatever form that takes for you.

So those were the 6 tips for trying to achieve work-life balance. Important to note that these are not strict requirements but instead just suggestions made by a fellow PhD on the interwebs just trying to help and figuring things out as they go along. In the end, how you choose to approach work-life balance is going to depend primarily on your circumstances, needs, values so while there is no universal correct way of doing it there is a correct way for you.

Further reading

Thank you for reading and if you haven’t started your PhD journey yet, but are interested in some tips for that then feel free to check out our Tips for Future PhDs blog series. Part 1 focuses on whether doing a PhD is actually a good idea or not. Part 2 is full of advice on finding a PhD position that works best for you. Part 3 has advice on the actual application process and tips for that.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Other Posts you might like:

How to prepare PhD students for their career

Traditionally, PhDs are trained within academia with the perspective of landing an academic job. But

A Hitchhikers Guide to a PhD: Don’t panic!

For effective learning make sure you get enough sleep

We spend approximately one-third of our lives asleep. Despite the vast amount of time we

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.17(7); 2021 Jul

Ten simple rules to improve academic work–life balance

Michael john bartlett.

1 Scion, Rotorua, New Zealand

Feyza Nur Arslan

2 Institute of Science and Technology Austria, Klosterneuburg, Austria

Adriana Bankston

3 Future of Research, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, United States of America

Sarvenaz Sarabipour

4 Institute for Computational Medicine and Department of Biomedical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America

Introduction

The ability to strike a perceived sense of balance between work and life represents a challenge for many in academic and research sectors around the world. Before major shifts in the nature of academic work occurred, academia was historically seen as a rewarding and comparatively low-stress working environment [ 1 ]. Academics today need to manage many tasks during a workweek. The current academic working environment often prioritizes productivity over well-being, with researchers working long days, on weekends, on and off campus, and largely alone, potentially on tasks that may not be impactful. Academics report less time for research due to increasing administrative burden and teaching loads [ 1 – 3 ]. This is further strained by competition for job and funding opportunities [ 4 , 5 ], leading to many researchers spending significant time on applications, which takes away time from other duties such as performing research and mentorship [ 1 , 2 ]. The current hypercompetitive culture is particularly impactful on early career researchers (ECRs) employed on short-term contracts and is a major driver behind the unsustainable working hours reported in research labs around the world, increases in burnout, and decline in satisfaction with work–life balance [ 6 – 10 ]. ECRs may also find themselves constrained by the culture and management style of their laboratory and principal investigator (PI) [ 11 – 12 ]. Work–life balance can be defined as an individual’s appraisal of how well they manage work- and nonwork-related obligations in ways that the individual is satisfied with both, while simultaneously maintaining their health and well-being [ 13 ]. Increasing hours at work can conflict with obligations outside of work, including but not limited to family care commitments, time with friends, time for self-care, and volunteering and community work. The increasing prevalence of technology that allows work to be out of the office can also exacerbate this conflict [ 14 , 15 ].

The academic system’s focus on publications and securing grant funding and academic positions instead of training, mentoring, and mental health has skewed the system negatively against prioritizing “The whole scientist” [ 5 , 16 ]. Research focused on the higher education sector has revealed that poor work–life balance can result in lower productivity and impact, stifled academic entrepreneurship, lower career satisfaction and success, lower organizational commitment, intention to leave academia, greater levels of burnout, fatigue and decreased social interactions, and poor physical and mental health, which has become increasingly prevalent among graduate students [ 1 , 17 – 22 ]. For instance, a recent international survey of over 2,000 university staff views on work–life balance found that many academics feel stressed and underpaid and struggle to fit in time for personal relationships and family around their ever-growing workloads [ 20 ]. These systemic issues are making it increasingly difficult to maintain an efficient, productive, and healthy research enterprise [ 23 ].

In the academic context, work–life balance needs to be examined with regard to spatial and temporal flexibility, employment practices, and employee habits. The need to improve work–life balance is recognized for researchers at all career stages [ 7 , 22 , 24 , 25 ]. While there is a growing literature providing specific strategies to cope with busy academic life [ 26 – 28 ], collating these disparate advice pieces into a coherent framework is a daunting task and few capture multifaceted advice by ECRs for ECRs. Departments and institutes need to contribute to improving research practices for academics at all levels on the career ladder [ 29 , 30 ]. PIs and mentors can promote healthier environments in their laboratories by respecting boundaries and providing individuals with greater autonomy over their own working schedule [ 11 , 12 , 31 – 33 ]. However, institutions do not typically prioritize work–life balance, leading to the loss of valuable talent in the research pipeline. The power dynamics within academia are evident now more than ever, with ECRs lacking agency at multiple time points and in controlling many aspects of their training. This may be especially true for trainees from underrepresented backgrounds, who face additional hurdles to their professional advancement in the current academic environment while attempting to maintain work–life balance. Furthermore, academia, in general, does not always value the aspects of a researcher’s job that the researcher finds important such as teaching, mentoring, and service. Thus, the experience of individual researchers regarding work–life balance will vary depending on multiple factors [ 34 – 39 ], including personal circumstances and satisfaction with aspects of life outside of work [ 40 ]. It is therefore unlikely that there is a “one size fits all” approach to effectively address work–life balance issues.

In order to support ECRs in maintaining work–life balance, institutions should support individualized strategies that are continually refined during their training. Here, drawing from our discussion as part of the 2019–2020 eLife Community Ambassador program and our experiences as ECRs, we examine the strategies individuals can adapt to strike a healthier balance between the demands of personal life and a career in research.

While many of the challenges junior academics face are systemic problems and will take a while to fix, some level of individual adjustment and planning may help ECRs more immediately and on an individual level. The rules presented here seek to empower ECRs to take action in improving their own well-being, while also providing a call to action for institutions to increase mechanisms of support for their trainees so they can thrive and move forward in their careers.

Rule 1: Long hours do not equal productive hours

One common reason for work–life imbalance is the feeling of lagging behind as a result of the present-day competitive nature of academia. This has led to incorrectly normalized practice of overwork, due to a sense of pressure from colleagues or ourselves, contributing to increasing mental health problems in academia [ 3 , 7 , 9 ]. On the other hand, keeping a balance sets one for higher productivity and creativity [ 41 ] and long-term satisfaction with work [ 17 , 18 ]. It is important to focus on the benefits of work–life balance on overall well-being and to accept that performing research and building a career in academia is a long process. Taking time off should not be associated with a feeling of guilt for not working at that moment. On the contrary, it should be seen as a necessity to have good health, energy, and motivation for the next return to work. A break can result in a boost to your productivity (rate of output) [ 42 ]. Studies show output of working hours to not increase linearly after a threshold and absence of a rest day to decrease output, as long hours result in errors and accidents, as well as fatigue, stress, and sickness [ 43 , 44 ]. It can be challenging to cut down on work hours when you feel that there is so much to get done. We also acknowledge that there are times when putting in long hours may be needed, for example, to meet a deadline; however, keeping this behavior constant might have more disadvantages than advantages in the long term.

Having flexibility in when and where you work can help you manage tasks and feel more balanced. It is important to discuss your needs with people at work and at home, in order to establish expectations and fit your lifestyle.

Rule 2: Examine your options for flexible work practices

Examine your relationship with your work, and try alternative schedules. Review your expected obligations, employer work hour rules, and offered benefits. Where possible, make use of modernization of work tools (such as remote work methods using digital technologies); working time is no longer exclusively based on in-person presence at the workplace, but rather the accomplishment of tasks [ 45 , 46 ]. The virtual office aspect can offer extensive flexibility in terms of time and location of work, reduce time spent traveling and commuting, and allow easier management of schedules and lives. Attending conferences online and giving invited talks, seminars, and interviews virtually can reduce fatigue and increase the time available for activities essential for your well-being [ 47 , 48 ]. Working remotely may not work for all or on many days of a week, but an overall reduction in travel is possible. In some instances, it may be difficult to know beforehand how much time you will be allocating to particular tasks in your new job, also some tasks such as fieldwork or labwork cannot be done remotely. Factor in workplace flexibility policies when looking at employment options and negotiating contracts. At the interview stage, ask your employer and prospective supervisor about flexible hours, options such as compressed workweeks, job sharing, telecommuting, or other scheduling flexibility to work in a way that best fits your efficiency and productivity. The more control you have over where and when you work, the less stressed you are likely to be. Once you know the options available to you, agree on a schedule based on your expectations and needs. Clear agreements on how and when to work are necessary to avoid conflict between work and nonwork obligations [ 45 ], so it is important to effectively communicate agreements with your managers, mentors [ 31 ], supervisors, colleagues, and also with your family. Having said this, in reality, ECRs may not always be able to negotiate salaries and benefits as conditions might be predetermined by an institution, a fellowship, or a PI’s strict expectations. Weigh the pros and cons of nonnegotiable job offers carefully. Remember that some constraints might be relaxed over time as your new employers build trust in you; therefore, continue the communication to find the best arrangements for your work.

As you try to reduce overworking and be more flexible with working arrangements, you will need to be very focused within the time frame that you have available. This is especially important as work–life balance boundaries become blurred if working from home. Setting boundaries is critical to success, as detailed below.

Rule 3: Set boundaries to establish your workplace and time

Setting spatial and temporal boundaries around your work is important for focusing on the task in hand and preventing work from taking over other parts of your life. When you are in the office and need to focus, make sure you can work in a quiet place where colleagues are unlikely to distract you. If you work in a shared office space, communicate with those around you to let them know your needs, or if you need complete silence, then consider working in a designated space for focused work. While working from home, some may struggle to disconnect from work, step away from screens, and set clear boundaries between digital and physical settings. Screen time needs to be managed so that remote workers do not blur the lines of work and life, as that can result in discouragement and burnout. Ask your coworkers to not demand your attention toward work after a certain time in the evening. Turn off email notifications outside of working hours. By setting boundaries, you will also set an example for your coworkers and mentees. When working at home, separating your workspaces from relaxation spaces can be helpful. This way, less clutter can decrease your stress levels, and a separated space can help you to draw a line between work and family. Even carving an area on a table dedicated to your work time can help with calm and work–life balance.

In order for your resulting work to be of high quality, diligence is key. In addition to being focused on your task, you should also establish a routine and prioritize your tasks, being able to then gain more control over your time. Learning to say no is also critical. Below we expand on these issues in the context of efficiency and productivity.

Rule 4: Commit to strategies that increase your efficiency and productivity

Many people use to-do lists and outline daily/weekly tasks, defining both work- and nonwork-related obligations that need to be accomplished. For nonwork responsibilities, devise a strategy with your family or those you live with to delegate tasks. Make sure responsibilities at home are clearly outlined and evenly distributed.

- Manage your time. Learning how to effectively manage your time and focus while at work is critical. Set a schedule to help in managing time, and do not forget to include buffer times between your plans, such as a coffee break with colleagues and a walk away from the bench or computer screen, to socialize and rest. Outside of busy periods, try to keep routines of work hours. Try time blocking, for example, check email and other social media (e.g., Slack) messages at specific times of the workday, and, if possible, arrange meetings at concentrated times during the day. This will maximize the amount of deep work that can be done during work hours. Sometimes, multitasking, for instance, running a few experiments at the same time or trying to work in between several meetings, may not result in great outcomes; have realistic plans and monotask if you find it better.

- Minimize decision fatigue. Decision fatigue refers to the deteriorating quality of decisions made by an individual after a long session of decision-making. Decision fatigue depletes self-control, which results in emotional stress, underachievement, lack of persistence, and even failures of task performance [ 49 ]. To reduce this, make the most important decisions first in your workday, and limit and simplify your choices.

- Collaborate. Workplace and home collaborations can take some of the load off and help in managing stress. Adjusting to teamwork or training a student may seem like extra commitments at the beginning, but, in the long run, they can help delegate some of the tasks on your calendar and help maintain a better work–life balance.

- Do not overcommit. Learn to say “no” [ 46 ]. Consider that accepting extra, low-impact tasks will sacrifice your nonwork time and may also take attention off your other important work appointments. Try to drop activities that drain your energy, such as nonessential meetings that do not enhance your life or career, and be efficient within this limited time with set goals.

- Discover your own strategies. Try to figure out what strategies work for you, and apply these to your life. Individuals respond differently to time of the day, physical conditions, and stress. Productivity may come with creative arrangements, and a high degree of organization may not work for everyone. Sometimes, improvisation and flexible schedules might be what you need.

As you begin to make decisions about the best way to manage your time, being strategic is key to prioritizing. You should aim to review your strategy and ability to stick to it often.

Rule 5: Have a long-term strategy to help with prioritization, and review it regularly

Having a long-term strategy that considers what you want to achieve and the timelines needed to get there can help with prioritization and deciding what to take on and what to say no to. This not only includes goals linked to your research career but also what is important to you outside of work, whatever this may be. When managing your work and nonwork tasks, see how well they align with your short- and long-term goals when you are deciding on the time and energy you need to allocate to attain them. With daily tasks, starting each day with the most important task, allocating the most productive hours to important tasks, as well as grouping similar tasks might help increase productivity and efficiency. A long-term look can help justify time spent on particular tasks, such as learning new skills, which might be taking extra time now but would help reduce stress in the long term. It is important to review your strategic goals and how well you are doing regularly, updating your strategy as needed. Consider using weekly time management charts to assess your task delegation retrospectively ( Fig 1 ). Have you been able to reach the goals you set? Did your time get taken up by other tasks? Did you use additional time to meet work goals at the expense of priorities outside of work? Are the goals you have set realistic and achievable, or do you need to make adjustments? If this appears overwhelming remember that your plans do not necessarily need to be detailed, simply keeping track of the hours spent working can be useful [ 26 ]. It is normal for priorities to change over time. Choose mentors that can help you achieve your short- and long-term goals, and consult with them regularly on your work–life balance strategies [ 31 ].

Dynamic, prospective, or retrospective weekly or monthly time management assessment charts can help researchers with improving their work–life balance by determining exactly how they spend their time. There are 164 hours in a week. Example hour allocation is shown here for academics across career stages [ 50 ]. Hours allocated will vary depending on the researcher’s disciplines (for instance, humanities versus life sciences or engineering) and circumstances such as end or beginning of semester, when approaching a deadline, or when a committee is busiest. Teaching responsibilities include course instruction and administration, including grading and evaluation. Family time includes interacting, dining, and performing housekeeping chores with family members. Research activities include performing research and literature review time. External service may include manuscript or grant reviewing and editorial tasks. Meetings may include lab/group meetings, departmental faculty meetings, or other council meetings. Self-care activities may include attending to one’s hobbies. Internal service includes department and university service. Weekends and public holidays are included in the weeks. Other tasks not included in this chart may be professional development, writing letters of recommendation, advising undergraduate students, faculty and student hiring/recruitment, marketing/public relations, fundraising, phone calls, reception/dinner, commute/travel, scheduling/planning, and reporting. ECR, early career researcher; MLCR, mid- to later career researcher; PI, principal investigator. Figure created using ggplot library in R [ 51 ].

In order to do your best in life and work, you need to put yourself first. You can do that by paying attention to your eating and sleeping schedule and engaging in activities that will keep you physically healthy and stimulate your mind.

Rule 6: Make your health a priority

You are not only defined by your work. Spending time on self-care and relaxation is a necessity in life to maintain a healthy body and mind, leading to a fulfilling lifestyle. This, in turn, will enable you to achieve peak performance and productivity in the workspace.

- Eat a healthy diet. A balanced diet with emphasis on fresh fruits, vegetables, and lean protein enhances the ability to retain knowledge as well as stamina and well-being. An option could be keeping fruit baskets in your office with your colleagues.

- Get enough sleep. Lack of sleep increases stress, and associated fatigue is linked to poor work–life balance [ 52 ]. One potential way to improve sleep quality is to avoid using personal electronic devices, such as smartphones and tablets, during your personal and other nonwork times, particularly right before going to sleep as screen time is associated with less and poorer quality rest [ 53 , 54 ].

- Prioritize your physical and mental health. Set time aside for individual or group physical activities of your choice. Schedule specific times for social activities and exercise to unwind, by arranging ahead of time with others or signing up to regular classes, making the plans harder to cancel. Using the gym at your workplace during a break can freshen you. Or you can bike or jog to work if safe to have some daily exercise. Equally important is dedicated time for your mental health. Reading a book, listening to music, gardening, many other activities, or if you prefer, regularly talking to a therapist could help you disengage from work, enjoy other aspects of life, rest, process, and recharge.

- Try meditation or mindfulness exercises. Meditation can reduce stress and increase productivity [ 29 ]; it will help you focus your thoughts and develop more self-awareness. If you are aware of when and why you are stressed or exhausted, these feelings become a trigger for you to lean into a boundary such as taking a screen break, going for a walk, or simply resting your eyes for 15 minutes before jumping back into a task or meeting. You can do meditation or yoga at home for short intervals. Do what is realistic for your life at the time and what helps you along.

- Make time for your hobbies and relaxation. Set aside time each day for an activity that you enjoy [ 28 , 55 , 56 ]. Discover activities you can do with your partner, family, or friends—such as hiking, dancing, or taking cooking classes. Listen to your favorite music at work to foster concentration, reduce stress and anxiety, and stimulate creativity [ 57 ].

While your work is important, you will be much happier if you schedule some social time into your week. This is a simple need, and methods vary from person to person, but the common goal is to increase your sense of connection and belonging, satisfaction with life, and/or energy.

Rule 7: Regularly interact with family and friends

Your work schedule does not need to lead to loss of your personal relationships. Scheduling time off to meet in-person or interact online with your loved ones in advance will make it harder to cancel plans in favor of working longer. As an example of good practice, most parents, even in academia, need to schedule their time around family responsibilities, which actually obliges them to maintain a work–life balance; they typically do not overstay at work every day, take the weekends off, and use annual leave. Meeting with friends and family will provide a chance to reconnect with them and your shared values. If you live in a country different from your family and friends, it is important to keep in touch using online audiovisual call and chat technologies. Other ways to relax include taking walks with loved ones, being out in nature, or playing board games. Social downtime can help replenish a person’s attention and motivation, encourages productivity and creativity, and is essential to both achieve our highest levels of performance and form stable memories in everyday life [ 58 ].

In addition to spending time for yourself and with family and friends, engaging in activities that are important to you, even when these activities are demanding, can bring a needed sense of achievement and satisfaction.

Rule 8: Make time for volunteer work or similar commitments that are important and meaningful to you

Many find additional engagements outside of their day to day jobs both important and rewarding. These activities would not be considered hobbies or relaxation, examples may include volunteering for the local community (e.g., at pet shelters, food banks, and environmental efforts), regional and online communities (e.g., student advocacy groups), time on boards or committees outside of work (e.g., acting as treasurer or secretary of a club), and learning a new language when you have moved to a new place. Many ECRs enjoy taking their work one step forward to volunteer with organizations focused on the societal value or impact of their work. This can help expand your perspective as an ECR working on a particular research topic, by understanding the broader picture of what you are working on and why and giving it a human impact dimension. Others may opt to volunteer in activities that are entirely independent of their research, which can provide opportunities to clear your mind for a good period of time and boost your mood. Although these activities add extra work to your schedule, if they are important to you, then you might find it difficult to find balance without the sense of achievement and reward they bring. However, when under pressure from work and home, finding time for these activities can be challenging—remember that work–life balance needs to be continually reassessed; consider taking a break if you need to and revisiting these extra commitments at a better time.

In addition to advisors and departments, institutions can take measures to support ECRs and provide them with necessary resources to thrive. They should also create a culture where asking for help is encouraged, and support for the well-being of researchers exists at their institution.

Rule 9: Seek out or help create peer and institutional support systems

Support systems are also critical to your success, and building more than one will increase your chances of success and balance overall [ 59 ]. At work, join forces with coworkers who can cover for you—and vice versa—when family conflicts arise. At home, enlist trusted friends and loved ones to pitch in with childcare or household responsibilities when you need to work overtime or travel. Seek support in academic communities and organizations who are working on mental health and well-being. For instance, PhD balance is a community space for academics to learn from shared experiences, to openly discuss and receive help for difficult situations, and to create resources and connect with others [ 60 ]. Dragonfly Mental Health, a nonprofit organization, strives to improve mental health care access and address the unhealthy culture pervading academia [ 61 ]. Everyone may need help from time to time. If life feels too chaotic to manage and you feel overwhelmed, talk with a professional, such as a counselor or other mental health provider. If your employer offers an employee assistance program, take advantage of available services. Joining a support and peer mentorship group, such as graduate, postdoctoral or faculty Slack communities [ 31 ], or working parents seeking and sharing work–life balance strategies, provides at least two key advantages: an opportunity to vent to people who truly understand your experiences and the ability to strategize with a group about how to improve your situation. A combination of these steps will help researchers to improve their work–life balance.

Finally, if your ability to effectively implement the advice in Rules 1 to 8 is constrained by the culture in your lab or pressure from the academic system, seek support from mentors, and advocate for yourself and for the change you would like to see.

Rule 10: Open a dialogue about the importance of work–life balance and advocate for systemic change

Spreading awareness and promoting good practice for managing work–life balance are essential toward shifting the prevailing culture away from current excellence at any cost practices. While major change is only likely to come about with a coordinated shift in the way that research laboratories, institutions, publishers, funders, and governments assess research endeavors at a broadscale, there is much that can be done at smaller scales to improve the culture at institutions and within labs [ 62 ]. Leverage the support of communities that empower ECRs to participate in advocating for the importance of mental well-being in academia through research and programs (see Rule 9). Discussions on work–life balance can also be initiated through seminars and courses. You can ask for, or if you plan to get more involved, organize workshops and training in your institute for ECRs. Another way to encourage collective work–life balance could be to host activities such as family and employee sports, outdoor movies, or picnic events encouraging family-friendly time and team building. Advocate for policies in your workplace that can help reduce conflict between work and other responsibilities, for example, childcare services or pet-friendly workspaces. To advocate at larger scales, you can join graduate/postdoctoral researcher associations, unions, or work councils to actively pursue work–life balance–friendly policies and employment contracts at institutes and through funding agencies. For instance, institutions and funding agencies that do not encourage the traditional gender roles allowing both men and women to take family leave, see better work–life balance, and reduced work–life conflict [ 63 , 64 ]. If the culture in your research lab constrains your ability to manage your work–life balance in a way you find satisfactory, shifting departmental and institutional attitudes and policies can put pressure on PIs to build a more supportive work culture via steps outlined elsewhere [ 11 , 12 , 31 – 33 ]. Although organizational culture cannot be changed overnight, changes in policy can go a long way in creating a culture that aids work–life balance in the academic workplace [ 62 – 64 ].

Conclusions

Most academic jobs come with flexible working hours, which can be advantageous when researchers attempt to balance the competing obligations in their lives. Yet, ECRs typically work significantly longer than the normal working hours of academic employment contracts [ 65 ]. How researchers spend their time has major impacts on their well-being, productivity, and professional scale of impact and those of their mentees, family, colleagues, and institutions in the short and long term. Academic culture has normalized and ignored overworking often at the expense of a social life, or of even greater concern, at the expense of researchers’ health and well-being. It is important for all academic researchers, institutions, and funding agencies to credit service and administrative activities, to acknowledge difficulties in satisfying work- and nonwork-related obligations in academic careers, and support diverse strategies to attain work–life balance [ 29 , 30 ]. It is imperative to examine work–life balance practices by ECRs, suggest improvements, and integrate these into employment and promotion offers. Here, we provided recommendations for ECRs to improve management of the balance between their professional and personal lives, but striking a healthy work–life balance is not a one-shot deal. Managing work–life balance is a continuous process as your family, interests, and work life change. Working long hours does not equate to working better. Regularly examine your priorities—and, if necessary, make changes—to ensure you stay on track. Ultimately, for the benefit of researchers and the important work that they do, both individuals and institutions need to make health and well-being a priority.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Inez Lam of Johns Hopkins University for valuable comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. We also thank the facilitators of the 2019–2020 eLife Community Ambassador program.

Funding Statement

This work was the product of volunteer time and the authors received no specific funding for this work.

Balancing Work, School, and Personal Life among Graduate Students: a Positive Psychology Approach

- Published: 24 July 2018

- Volume 14 , pages 1265–1286, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Jessica M. Nicklin 1 ,

- Emily J. Meachon 1 &

- Laurel A. McNall 2

6598 Accesses

21 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

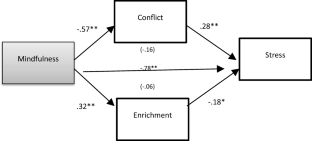

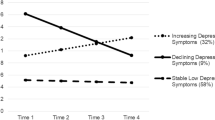

Graduate students are faced with an array of responsibilities in their personal and professional lives, yet little research has explored how working students maintain a sense of well-being while managing work, school, and personal-life. Drawing on conservation of resources theory and work-family enrichment theory, we explored personal, psychological resources that increase enrichment and decrease conflict, and in turn decrease perceptions of stress. In a study of 231 employed graduate students, we found that mindfulness was negatively related to stress via perceptions of conflict and enrichment, whereas self-compassion, resilience, and recovery experience were negatively related to stress, but only through conflict, not enrichment. These findings suggest that graduate students who are able to be “in the moment” may experience higher levels of well-being, in part due to greater enrichment and lower conflict.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Exploring How Mindfulness Links to Work Outcomes: Positive Affectivity and Work-Life Enrichment

Examining ways that a mindfulness-based intervention reduces stress in public school teachers: a mixed-methods study.

Charting a Course, Weathering Storms, and Making Lemonade: A Person-Centered Mixed Methods Analysis of Emotional Wellbeing and Dispositional Strengths following University Graduation

Allen, T. D., & Kiburtz, K. M. (2012). Trait mindfulness and work-family balance among working parents: The mediating effects of vitality and sleep quality. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80 , 372–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.09.002 .

Article Google Scholar

Allen, T. D., & Paddock, E. L. (2015). How being mindful impacts individuals' work-family balance, conflict, and enrichment: A review of existing evidence, mechanisms and future directions. In J. Reb, P. B. Atkins, J. Reb, & P. B. Atkins (Eds.), Mindfulness in organizations: Foundations, research, and applications (pp. 213–238). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Amstad, F. T., Meier, L. L., Fasel, U., Elfering, A., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16 (2), 151–169 http://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0022170 .

Baghurst, T., & Kelley, B. C. (2014). An examination of stress in college students over the course of a semester. Health Promotion Practice, 15 (3), 438–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839913510316 .

Baron, R. M. & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51 (6), 1173–1182.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life . New York: Wiley.

Google Scholar

Bonifas, R. P., & Napoli, M. (2013). Mindfully increasing quality of life: A promising curriculum for MSW students. Social Work Education, 33 , 469–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2013.838215 .

Braunstein-Bercovitz, H., Frish-Burstein, S., & Benjamin, B. A. (2012). The role of personal resources in work–family conflict: Implications for young mothers' well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80 (2), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.10.003 .

Britt, T. W., Shen, W., Sinclair, R. R., Grossman, M. R., & Klieger, D. M. (2016). How much do we really know about employee resilience? Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 9 (2), 378–404. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2016.36 .

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84 , 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822 .

Carley-Baxter, L. R., Hill, C. A., Roe, D. J., Twiddy, S. E., Baxter, R. K., & Ruppenkamp, J. (2009). Does response rate matter? Journal editors use of survey quality measures in manuscript publication decisions. Survey Practice, 2 (7), 1–7.

Carlson, L. E., & Brown, K. W. (2005). Validation of the mindful attention awareness scale in a cancer population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58 , 29–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.04.366 .

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Wayne, J. H., Grzywacz, J. G. (2006). Measuring the positive side of the work–family interface: Development and validation of a work–family enrichment scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68 (1), 131–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.02.002 .

Cheng, B. H., & McCarthy, J. M. (2013). Managing work, family, and school roles: Disengagement strategies can help and hinder. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18 , 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032507 .

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18 (2), 76–82.

Council of Graduate Schools. Graduate Schools Report Strong Growth In First-Time Enrollment Of Underrepresented Minorities . 2016. Print.

Creed, P. A., French, J., & Hood, M. (2015). Working while studying at university: The relationship between work benefits and demands and engagement and well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86 , 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.11.002 .

Davis, J. (2012). School enrollment and work status: 2011. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/acsbr11-14.pdf .

Ditto, B., Eclache, M., & Goldman, N. (2006). Short-term autonomic and cardiovascular effects of mindfulness body scan meditation. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 32 (3), 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3203_9 .

Dyrbye, L. N., Power, D. V., Massie, F. S., et al. (2010). Factors associated with resilience to and recovery from burnout: A prospective, multi-institutional study of US medical students. Medical Education, 44 , 1016–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03754.x .

Etzion, D., Eden, D., & Lapidot, Y. (1998). Relief from job stressors and burnout: Reserve service as a respite. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83 , 377–585.

Evans, T. M., Bira, L., Gastelum, J. B., Weiss, T. L., & Vanderford, N. L. (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36 , 282–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4089 .

Flavin, C. & Swody, C. (2016). LeaderMoms use self-compassion as antidote to unproductive guilt. Tech report. Thrive Leadership.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 359 (1449), 1367–1378. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1512 .

Gable, S. L., & Haidt, J. (2005). What (and why) is positive psychology? Review of General Psychology, 9 (2), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.103 .

Gilbert, P. (2005). Compassion and cruelty: A biopsychosocial approach. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 9–74). London: Routledge.

Goewey, (2015). Generation stress. The Huffington Post. Retrieved From: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/don-joseph-goewey-/generation-stress_b_8062346.html .

Greenhaus, J. H., & Parasuraman, S. (1999). Research on work, family, and gender: Current status and future directions. In G. N. Powell (Ed.), Handbook of Gender & Work (pp. 391–412). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31 , 72–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.02.002 .

Greeson, J. M., Juberg, M. K., Maytan, M., James, K., & Rogers, H. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of KORU: A mindfulness program for college students and other emerging adults. Journal of American College Health, 64 (4), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2014.887571 .

Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57 , 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7 .

Hahn, V. C., Binnewies, C., Sonnentag, S., & Mojza, E. J. (2011). Learning how to recover from job stress: Effects of a recovery training program on recovery, recovery-related self-efficacy, and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16 (2), 202–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022169 .

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach . New York: Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2016). Partial, conditional, and moderated mediation: Quantification, inference and interpretation . Retrieved from http://afhayes.com/public/pmm2016.pdf .

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44 (3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513 .

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6 , 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307 .

Hoffman, J. (2015). Anxiety on campuses: Reporter’s notebook. The New York Times . Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/times-insider/2015/05/28/anxiety-on-campus-reporters-notebook/ .

Holland, K. (2014). Back to school: Older students on the rise in college classrooms. Nbcnews.com . Retrieved from: http://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/back-school-older-students-rise-college-classrooms-n191246 .

Kabat-Zinn. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness . New York: Bantam Dell.

Kadziolka, M. J., Di Pierdomenico, E., & Miller, C. J. (2016). Trait-like mindfulness promotes healthy self-regulation of stress. Mindfulness, 7 (1), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0437-0 .

Karatepe, O. M., & Karadas, G. (2014). The effect of psychological capital on conflicts in the work-family interface, turnover and absence intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 43 , 132–143.

Kiburz, K.M., & Allen, T.D. (2012). Dispositional mindfulness as a unique predictor of work-family conflict . Paper presented at the 27th annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, April 2012, San Diego, CA.

Kiburz, K.M., & Allen, T.D. (2014). Examining the effects of mindfulness based work-family interventions. In J.G. Randall and M. Beier (Co-chairs), in MindWandering and Mindfulness: Self-regulation at Work. Symposium presented at the 29 th Annual conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, May 2014, Honolulu, HI.

King, J. (2006). Working their way through college: Student employment and its impact on the college experience. ACE Issue Brief. Retrieved from: http://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Documents/IssueBrief-2006-Working-their-way-through-College.pdf .

Krisor, S. M., Diebig, M., & Rowold, J. (2015). Is cortisol as a biomarker of stress influenced by the interplay of work-family conflict, work-family balance and resilience? Personnel Review, 44 (4), 648–661.

Kruger, S., & Sonoro, E. (2016). Physical activity and psychosomatic-related health problems as correlates of quality of life among university students. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 26 , 357–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2016.1185907 1-6.

Kunz-Ebrecht, S. R., Kirschbaum, C., Marmot, M., & Steptoe, A. (2004). Differences in cortisol awakening response on work days and weekends in women and men from the Whitehall II cohort. Physchoneuroendocrinology, 29 , 516–528.

Lemyre, L., & Tessier, R. (2003). Measuring psychological stress. Concept, model, and measurement instrument in primary care research. Canadian Family Physician Medecin De Famille Canadien, 49 , 1159–1160.

Li, M. (2008). Relationships among stress coping, secure attachment, and the trait of resilience among Taiwanese college students. College Student Journal, 42 (2), 312–325.

Lundberg, U., & Frankenhaeuser, M. (1999). Stress and workload of men and women in high-ranking positions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 4 , 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.4.2.142 .

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and job satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60 , 541–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x .

Mallya, S., & Fiocco, A. J. (2016). Effects of mindfulness training on cognition and well-being in healthy older adults. Mindfulness, 7 (2), 453–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0468-6 .

Markel, K. S., & Frone, M. R. (1998). Job characteristics, work-school conflict, and school outcomes among adolescents: Testing a structural model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83 , 277–287.

Marks, S. R. (1977). Multiple roles and role strain: Some notes on human energy, time and commitment. American Sociological Review, 41 , 921–993.

McNall, L. A., & Michel, J. S. (2011). A dispositional approach to work–school conflict and enrichment. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26 (3), 397–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9187-0 .

McNall, L. A., & Michel, J. S. (2017). The relationship between student core self-evaluations, support for school, and the work–school interface. Community, Work & Family, 20 , 253–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2016.1249827 .

McNall, L. A., Nicklin, J. M., & Masuda, A. (2010). A meta- analytic review of the consequences associated with work- family enrichment. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25 , 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9141-1 .

Michel, A., Bosch, C., & Rexroth, M. (2014). Mindfulness as a cognitive–emotional segmentation strategy: An intervention promoting work–life balance. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87 (4), 733–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12072 .

Moreno-Jiménez, B., Mayo, M., Sanz-Vergel, A. I., Geurts, S., Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., & Garrosa, E. (2009). Effects of work–family conflict on employees’ well-being: The moderating role of recovery strategies. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14 (4), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016739 .

Mosewich, A. D., Kowalski, K. C., Sabiston, C. M., Sedgwick, W. A., & Tracy, J. L. (2011). Self-compassion: A potential resource for young women athletes. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 33 (1), 103–123.

National Center for Education Statistics (2017). Postbaccalaureate Enrollment. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_chb.asp .

Neely, M. E., Schallert, D. L., Mohammed, S. S., Roberts, R. M., & Chen, Y. (2009). Self-kindness when facing stress: The role of self-compassion, goal regulation, and support in college students’ well-being. Motivation and Emotion, 33 , 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9119-8 .

Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2 , 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860390129863 .

Neff, K., & Germer, C. (2013). Being kind to yourself: The science of self-compassion. In T. Singer & M. Bolz (Eds.), Compassion: Bridging theory and practice: A multimedia book (pp. 291–312). Leipzig: Max-Planck Institute.

Neff, K. D., & McGehee, P. (2009). Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self and Identity, 9 (3), 226–240 http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15298860902979307 .

Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L., & Rude, S. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41 , 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004 .

Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., & Mcmurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81 (4), 400–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400 .

Nicklin, J. M., & McNall, L. A. (2013). Work–family enrichment, support, and satisfaction: A test of mediation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22 (1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2011.616652 .

Nicklin, J. M., McNall, L. A., & Janssen, A. (2018). An examination of positive psychological resources for promoting work-life balance. In J. M. Nicklin (Ed.), Work-family balance in the 21 st century . New York: Nova.

Park, Y., & Fritz, C. (2015). Spousal recovery support, recovery experiences, and life satisfaction crossover among dual-earner couples. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 557–566. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037894 .

Park, Y. A., & Sprung, J. M. (2013). Work-school conflict and health outcomes: Beneficial resources for working college students. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18 , 384–394. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033614 .

Park, Y., & Sprung, J. M. (2015). Weekly work-school conflict, sleep quality, and fatigue: Recovering self-efficacy as a cross-level moderator. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36 , 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1953 .

Parker, K., & Wang, W. (2013). Modern parenthood: Roles of moms and dads converge as they balance work and family. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/03/14/modern-parenthood-roles-of-moms-and-dads-converge-as-they-balance-work-and-family/ .

Parkinson, B., & Totterdell, P. (1999). Classifying affect regulation strategies. Cognition and Emotion, 13 , 277–303.

Phillips, W. J., & Ferguson, S. J. (2012). Self-compassion: A resource for positive aging. Journal of Gerontology, 68 (4), 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs091 .

Podsako, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsako, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88 (5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 .

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36 (4), 717–731.

Pryor, J. H., Hurtado, S., DeAngelo, L., Palucki Blake, L., & Tran, S. (2010). The American freshman: National norms fall 2010 . Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA.

Qu, Y., Dasborough, M. T., & Todorova, G. (2015). Which mindfulness measures to choose to use? Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 8 (04), 710–723. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.105 .

Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18 , 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.702 .

Roche, M., Haar, J. M., & Luthans, F. (2014). The role of mindfulness and psychological capital on the well-being of leaders. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19 (4), 476–489. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037183 .

Roeser, R. W., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Jha, A., Cullen, M., Wallace, L., Wilensky, R., Oberle, E., Thomson, K., Taylor, C., & Harrison, J. (2013). Mindfulness training and reductions in teacher stress and burnout: Results from two randomized, waitlist-control field trials. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105 , 787–804. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032093 .

Sanz-Vergel, A., Demerouti, E., Moreno-Jimenez, B., & Mayo, M. (2010). Work-family balance and energy: A day-level study on recovery conditions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76 (1), 118–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.07.001 .

Seligman, M. E. P. (1998). Positive social science. APA monitor, 29 (4), 2–5.

Sherrington, C. B. (2014). Graduate psychology students' experience of stress: Is a symptom expression modified by dispositional mindfulness, experiential avoidance, and self-attention style? Dissertation Abstracts International, 75 , 117.

Sieber, S. D. (1974). Toward a theory of role accumulation. American Sociological Review, l39 (4), 567–578. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094422 .

Singh, N. N., Singh, A. N., Lancioni, G. E., Singh, J., Winton, A. S. W., & Adkins, A. D. (2010). Mindfulness training for parents and their children with ADHD increases the children’s compliance. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19 , 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9272-z .

Sirois, F. M. (2014). Procrastination and stress: Exploring the role of self- compassion. Self and Identity, 13 (2), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2013.763404 .

Siu, O. L., Cooper, C. L., & Phillips, D. R. (2014). Intervention studies on enhancing work well-being, reducing burnout, and improving recovery experiences among Hong Kong health care workers and teachers. International Journal of Stress Management, 21 (1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033291 .

Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). The recovery experience questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12 , 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.204 .

Soysa, C. K., & Wilcomb, C. J. (2013). Mindfulness, self-compassion, self-efficacy, and gender as predictors of depression, anxiety, stress, and well-being. Mindfulness, 6 , 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0247-1 .

Steinhardt, M., & Dolbier, C. (2008). Evaluation of a resilience intervention to enhance coping strategies and protective factors and decrease symptomatology. Journal of American College Health, 56 , 445–453. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.56.44.445-454 .

Stuart, E. A. (2010). Academy health: Advancing research, policy and practice. Academy Health . Retrieved from: www.academyhealth.org/files/2010/sunday/stuartE.pdf .

Tarrasch, R. (2015). Mindfulness meditation training for graduate students in educational counseling and special education: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24 (5), 1322–1333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9939-y .

Thompson, C. (2001). Conservation of resources theory. Sloan Network Encyclopedia. Retrieved from: https://workfamily.sas.upenn.edu/wfrn-repo/object/pt3yu38m2ae8vj2t .

Van der Klink, J. J. L., Blonk, R. W. B., Schene, A. H., & Van Dijk, F. J. H. (2001). The benefits of interventions for work-related stress. American Journal of Public Health, 91 , 270–276.

Wilks, S. E. (2008). Resilience amid academic stress: The moderating impact of social support among social work students. Advances in Social Work, 9 , 106–125 Retrieved.

Wilks, E. S., & Spivey, C. A. (2010). Resilience in undergraduate social work students: Social support and adjustment to academic stress. Social Work Education, 28 (3), 276–288.

Wyland, R. L., Lester, S. W., Mone, M. A., & Winkel, D. E. (2013). Work and school at the same time: A conflict perspective of the work–school interface. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 20 , 346–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051813484360 .

Wyland, R., Lester, S. W., Ehrhardt, K., & Standifer, R. (2015). An examination of the relationship between the work–school interface, job satisfaction, and job performance. Journal of Business and Psychology, 31 (2), 187-203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-015-9415-8 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Hartford, 200 Bloomfield Avenue, West Hartford, CT, 06119, USA

Jessica M. Nicklin & Emily J. Meachon

The College at Brockport, State University of New York, New York, NY, USA

Laurel A. McNall

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jessica M. Nicklin .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interested associated with this paper and we did not include any identifying information in the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Nicklin, J.M., Meachon, E.J. & McNall, L.A. Balancing Work, School, and Personal Life among Graduate Students: a Positive Psychology Approach. Applied Research Quality Life 14 , 1265–1286 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9650-z

Download citation

Received : 02 August 2017

Accepted : 09 July 2018

Published : 24 July 2018

Issue Date : November 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9650-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Self-compassion

- Mindfulness

- Graduate students

- Conservation of resources

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Nov. 13, 2023

Work-life balance in graduate school, by: manuel carmona pichardo. manuel explores ways of maintaining a work-life balance in graduate school..

Graduate school is a challenging yet rewarding journey that demands rigorous academic commitment, research, and personal growth. As graduate students navigate this phase of their education, balancing academic pursuits and emotional well-being is essential. A healthy work-life balance is crucial for success and maintaining physical and mental health. In this blog, I will discuss the importance of work-life balance in graduate school, including some common barriers and practical tips to help establish this balance.

Maintaining a work-life balance in graduate school is essential for preserving one's physical and mental well-being, fostering creativity, nurturing strong relationships, and setting the stage for a sustainable and successful academic and professional journey. However, maintaining such balance is easier said than done! Sadly, there can be a lack of open discussion about work-life balance in the context of graduate studies and academia. This can be attributed to several factors, such as:

- Lab/group culture: In some academic and research environments, there is a culture of overwork and extreme dedication to one's studies or work. This can create a stigma around discussing work-life balance, as some may perceive it as a sign of weakness or lack of commitment.

- Academic Pressure: Graduate students often feel immense pressure to excel academically, which can deter them from addressing issues related to work-life balance. They might be concerned that discussing these issues could be seen as a sign of inadequacy or an inability to handle the demands of their field.

- Lack of Awareness: Some students and faculty may not fully understand the importance of work-life balance or the potential consequences of neglecting it. This lack of awareness can lead to a failure to prioritize discussions around this topic.

- Advisor-Student Dynamics: In academia, the dynamic between advisors and their students can make students hesitant to discuss personal concerns, including work-life balance. Students may fear repercussions or that they are potentially jeopardizing academic or professional relationships.

- Perceived Competition: Graduate students may feel a sense of competition with their peers, and discussing work-life balance might be seen as a weakness or a lack of commitment to the field. This perceived competition can discourage open conversations about balance.

- Institutional Expectations: Some academic institutions place a heavy emphasis on research, publishing, and academic performance, which can reinforce a culture of overwork and devalue work-life balance. This can create an institutional barrier to open discussions on the topic.

There is growing recognition within academia and among students of the importance of work-life balance. Many universities and organizations are taking steps to address this issue by offering resources, workshops, and support services focused on well-being and work-life balance. Graduate student associations and advocacy groups are also crucial in promoting conversations around a sustainable work-life balance and encouraging cultural shifts within academia.

Despite acknowledging the importance of work-life balance, students may face several challenges that complicate maintaining a healthy schedule. For one, graduate school comes with intensive workloads and expectations. The academic demands, including coursework, research, and teaching responsibilities, can be overwhelming, leaving little time for personal life. This heavy workload can lead students to experience mental health issues. Burnout can also hinder productivity and harm one's overall quality of life.

Another problem is that graduate students can have irregular and unpredictable schedules due to the timing of experiments and other activities, making it difficult to plan and maintain consistent routines outside their academic commitments. Participating in group activities can also help reduce some of the stress of graduate studies. Many graduate students also face financial constraints, which may lead them to take up additional work outside of their studies to make ends meet. This can further exacerbate the challenges of balancing work and personal life.

Below are some tips for prioritizing a healthy work-life balance:

- Prioritize Time Management: Effective time management is the cornerstone of maintaining work-life balance. Develop a schedule that allocates dedicated time for research, coursework, and personal activities. Use calendars or digital planners to stay organized and set realistic daily goals.

- Establish clear boundaries between work and personal life: Avoid working excessively long hours or bringing work home. Setting specific boundaries allows you to disconnect from academic responsibilities when it's time for relaxation and self-care.

- Practice Self-Care: Make self-care a priority. Engage in activities that promote physical and mental well-being, such as exercise, meditation, reading for pleasure, or pursuing hobbies. Take breaks to recharge and reduce stress.

- Seek Support: Don't hesitate to seek support when needed. Reach out to friends, labmates, mentors, academic advisors, or counselors if you face academic or personal challenges. Sharing your concerns with a support network can help alleviate stress and anxiety.

- Socialize and Network: Attend departmental events, conferences, and social gatherings to connect with peers and faculty. Building a supportive community can enhance your academic and personal life.

- Learn to Say No: It's essential to recognize your limitations and not overcommit. Politely decline additional responsibilities or commitments that may interfere with your work-life balance. Prioritize your well-being.

In conclusion, work-life balance is vital to success and well-being in graduate school. Balancing academic rigor with personal life can help you avoid burnout, maintain mental health, foster creativity, and build strong relationships. Ultimately, a balanced approach will lead to success in graduate school and set the foundation for a happy and healthy future. I hope this blog has helped you in some way!

Work Life Balance in Graduate School

By Luke Wink-Moran

Photo by Pixel-Shot

Deadlines, classes, and work all sometimes feel a higher priority than resting or spending time with friends and family. But according to UArizona experts, unbalanced priorities can be harmful to your health and compromise your professional success.

“Time away from work is incredibly important,” says Dr. David Sbarra, a professor in the Department of Psychology where he directs the Laboratory for Social Connectedness and Health. “People misunderstand this key point all of the time and just try to take on more and more work.”

According to Dr. Sbarra, students who take on too much work risk placing themselves in a state of chronic stress, which can lead to sleep disruptions and create “a psychological environment in our body that makes us more susceptible to disease.” Dr. Sbarra explained that sleep disruptions can also lead to an increased risk of adverse events like car accidents and chronic illness.

Graduate students should be aware of the risks of chronic stress because, according to Dr. Leslie Ralph, a psychologist who works in the University of Arizona’s CAPS department, “Research on graduate students does show that they experience a much higher level of distress than the general population. Studies on graduate and professional students also shows that quality of life and general well-being are significant protective factors in their success. In other words, having a low quality of life and general well-being can put students at risk for failing.”

So the case for finding work-life balance becomes clear: a well-balanced life benefits not only students’ mental health, but their performance in school.

When asked why some graduate students might have a hard time finding a work-life balance, and what she might like to say to them, Dr. Ralph said, “Many times, grad students have high (or even unrealistic) expectations for themselves, might feel like an “imposter,” or be afraid of disappointing others. It can sometimes feel like it isn’t safe to feel good, and it can be hard to remember that well-being involves so much more than academic success.”

For those students who want to take strides towards a healthier work-life balance, Dr. Sbarra shared this advice: “Setting and maintaining good boundaries are important to establishing work-life balance. I work best when I do not work too much. There’s irony in this statement: To work better, work smarter hours, not necessarily longer hours. For me, smarter hours means being well-rested.”

For more specific strategies that students, faculty, and staff can use to maintain a healthy work-life balance, Lourdes A. Rodríguez, Manager of Childcare and Family Resources at Life & Work Connections, offers the following suggestions:

Self-care: Everything starts with recognizing the importance of caring for yourself. If you do not take the time and needed steps to stay physically and mentally healthy, you won’t be able to achieve your goals.

Reasonable expectations : Thoroughly assess what you can and cannot do. Nobody is perfect; therefore, do not aim for perfection, but for “good enough.” This means you need to learn to say “no” sometimes.

Planning: Good time management enables us to work smarter, not harder.

Adaptability: N o matter how much we plan, the unexpected can happen; therefore, it is important to accept changes and adapt as needed.

Boundaries : Establish clear guidelines for suitable behaviors and responsibilities. Often, expectations are implied or assumed. It’s helpful to be explicit about boundaries in order to benefit fully from the safeguards they allow.

Communication : This includes not only speaking, but active listening. Developing good communication skills helps us to clearly share our opinions, desires, and needs.

For more information, check out the CAPS graduate student groups and self-help resources in the following links:

Self-Care Tips for Grad Students: https://caps.arizona.edu/self-care-tips-grad-students

Pathways to Wellness Personal Wellness Plan: https://caps.arizona.edu/pathwaystowellness

CAPS groups overview: https://caps.arizona.edu/groups-overview

A List of Resources for Graduate Students with Children https://grad.arizona.edu/diversityprograms/sites/default/files/uagc_page/final_students_who_are_parents_resources.pdf

The Cognitive Sciences Graduate Student Corner

at UC Irvine

Achieve work-life balance in grad school

A good work-life balance contributes to your overall mental and physical health. Since graduate students are six times more likely to experience depression or anxiety than the general population, achieving a good work-life balance should be one of your top priorities.

Working Longer ≠ Working Better

The stereotypical grad student is overworked and doesn’t have time for anything but their research. But this stereotype is based on a flawed idea. Working longer doesn’t mean you’re working better. Are you really doing your best work after 12 straight hours on the same task? Is there really any benefit to starting a new project at 8 pm rather than waiting until the next morning?