A Marxist View of Medical Care

This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst . For more information or to support the project, email [email protected]

by Howard Waitzkin

‘science for the people’ vol. 10, no. 6, november/december 1978, p. 31–42.

Reprinted, with modifications, from Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 89, No.2, Aug. 1978, with permission of the editor.

This version has been condensed. Readers are referred to the original article for the complete text and unedited references. Reprints are available from Howard Waitzkin at La Clinica de Ia Raza, 1501 Fruitvale Avenue, Oakland, CA 94601. To cover postage and printing, $2 would be appreciated if possible.

Howard Waitzkin is a health worker at La Clinica de Ia Raza, a community health center in Oakland, California.

This article surveys the Marxist literature in medical care. The Marxist viewpoint questions whether major improvements in the health system can occur without fundamental changes in the broad social order. One thrust of the field—an assumption also accepted by many non-Marxists—is that the problems of the health system reflect the problems of our larger society and cannot be separated from those problems.

Marxist analyses of health care have burgeoned in the United States during the past decade. However, it is not a new field. Its early history and the reasons for its slow growth until recently deserve attention.

Historical Development of the Field

The first major Marxist study of health care was Engels’ The Condition of the Working Class in England , originally published in 1845—three years before Engels co-authored with Marx The Communist Manifesto . This book described the dangerous working and housing conditions that created ill health. In particular, Engels traced such diseases as tuberculosis, typhoid, and typhus to malnutrition, inadequate housing, contaminated water supplies, and overcrowding. Engels’ analysis of health care was part of a broader study of working-class conditions under capitalist industrialization. But his treatment of health problems was to have a profound effect on the emergence of social medicine in Western Europe and, in particular, on the work of Rudolph Virchow.

Virchow’s pioneering studies in infectious disease, epidemiology, and “social medicine” (a term Virchow popularized in Western Europe) appeared soon after the publication of Engels’ book. Virchow himself acknowledged Engels’ influence on this thought. In 1847, at the request of the Prussian government, Virchow investigated a severe typhus epidemic in a rural area of the country. Based on this study, he recommended a series of profound economic, political, and social changes that included increased employment, better wages, local autonomy in government, agricultural cooperatives, and a more progressive taxation structure. Virchow advocated no strictly medical solutions, like more clinics or hospitals. Instead, he saw the origins of ill health in societal problems. The most reasonable approach to the problem of epidemics, then, was to change the conditions that permtited them to occur.

During this period Virchow became committed to combining his medical work with political activities. In 1848 he joined the first major working-class revolt in Berlin. During the same year he strongly supported the short-lived revolutionary efforts of the Paris Commune. 1 In his scientific investigations and in his political practice, Virchow expressed two overriding themes. First, that there are many interacting causes of disease. Among the most important factors in causation are the material conditions of people’s everyday lives. Secondly, an effective health-care system cannot limit itself to treating the illnesses of individual patients. Instead, to be successful, improvements in the health-care system must coincide with fundamental economic, political, and social changes. The latter changes often impinge upon the privileges of wealth and power enjoyed by the dominant classes of society and encounter resistance. Therefore, in Virchow’s view, the responsibilities of the medical scientist frequently extend to direct political action.

After the revolutionary struggles of the late 1840s suffered defeat, Western European governments heightened their conservative social policies. Marxist analysis of health care entered a long period of eclipse, and Virchow and his colleagues turned to relatively uncontroversial research in laboratories and to private practice.

During the late nineteenth century, with the work of Ehrlich, Koch, Pasteur, and other prominent bacteriologists, germ theory gained ascendancy and created a profound change in medicine’s diagnostic and therapeutic assumptions. A single-factor model of disease emerged. Medical scientists searched for organisms causing infections and single lesions in non-infectious disorders. The discoveries of this period undeniably improved medical practice. Still, as numerous investigators have shown, the historical importance of these discoveries has been overrated. For example, the major declines in mortality and morbidity from most infectious diseases preceded rather than followed the isolation of specific “germs” and the use of anti-microbial therapy. In Western Europe and the United States, improved outcomes in infections occurred after the introduction of better sanitation, regular sources of nutrition, and other broad environmental changes. In most cases, improvements in disease patterns antedated the advances of modern bacteriology. 2

Why did the unifactorial perspective of germ theory achieve such prominence? And why have the investigational techniques based on this perspective retained a nearly mythic character in medical science and practice to the present day? A serious historical re-examination of early twentieth century medical science, that attempts to answer these questions, has begun only in the last few years. Some preliminary explanations have emerged; they focus on events that led to and followed publication of the Flexner Report on medical education in 1910. 3

The Flexner Report has held high esteem as the document that helped change modern medicine from quackery to responsible practice. One underlying assumption of the Report was that laboratory-based scientific medicine, oriented especially to the concepts and methods of European bacteriology, produced a higher quality and more effective medical practice. Although the comparative effectiveness of various medical traditions (including homeopathy, traditional folk healing, chiropractic, etc.) had never been subjected to systematic test, the Report argued that medical schools not oriented to scientific medicine fostered mistreatment of the public. The Report called for the closure or restructuring of schools that were not equipped to teach laboratory-based medicine. The Report’s repercussions were swift and dramatic. Scientific, laboratory-based medicine became the norm for medical education, practice, research, and analysis.

Recent historical studies cast doubt on assumptions in the Flexner Report that have comprised the widely accepted dogma of the last century. They also document the un-critical support that the Report’s recommendations received from parts of the medical profession and the large private philanthropies. 4 At least partly because of these events, the Marxist orientation in medical care remained in eclipse.

Although some of Virchow’s works gained recognition as classics, the multifactorial and politically oriented model that guided his efforts has remained largely buried. Without doubt, Marxist perspectives had important impacts on health care outside Western Europe and the United States. For example, Lenin applied these perspectives to the early construction of the Soviet health system. Salvador Allende’s treatise on the political economy of health care, written while Allende was working as a public health physician, exerted a major influence on health programs in Latin America. The Canadian surgeon, Norman Bethune, contributed analyses of tuberculosis and other diseases, as well as direct political involvement, that affected the course of post-revolutionary Chinese medicine. 5 Che Guevara’s analysis of the relations among politics, economics, and health care—emerging partly from his experience as a physician—helped shape the Cuban medical system. 6

Perhaps reflecting the political ferment of the late 1960s and widespread dissatisfaction with various aspects of modern health systems, serious Marxist scholarship of health care has grown rapidly. 7 The following sections of this review cover some of the current areas of research and analysis.

Class Structure

Marx’s definitions of social class emphasized the social relations of economic production. He noted that one group of people, the capitalist class or bourgeoisie, own and/or control the means of production—the machines, factories, land, and raw materials necessary to make products for the market. The working class or proletariat, who do not own or control the means of production, must sell their labor for a wage. But the value of the product that workers produce is always greater than their wage. Workers must give up their product to the capitalist; by losing control of their own productive process, workers become subjectively “alienated” from their labor. The need to maintain profits motivates the capitalist to keep wages low, to change the work process (by automation and new technologies, close supervision, lengthened work day or overtime, speed-ups and dangerous working conditions), and to resist workers’ organized attempts to gain higher wages or more control in the workplace.

While acknowledging the historical changes that have occurred since Marx’s time, recent Marxist studies have reaffirmed the presence of highly stratified class structures in advanced capitalist societies and Third World nations. 8 Another topic of great interest is the persistence or reappearance of class structure, usually based on expertise and professionalism, in countries where socialist revolutions have taken place; 9 a later section of the review focuses on this problem. These theoretical and empirical analyses show that relations of economic production remain a primary basis of class structure and a reasonable focus of strategies for change.

Control over health institutions. Navarro has documented the pervasive control that members of the corporate and upper-middle classes exert within the policymaking bodies of American health institutions. These classes predominate on the governing boards of private foundations in the health system, private and state medical teaching institutions, and local voluntary hospitals. Only on the boards of state teaching institutions and voluntary hospitals do members of the lower middle class or working class gain any appreciable representation; even there, the participation from these classes falls far below their proportion in the general population. Navarro has argued, based partly on these observations, that control over health institutions reflects the same patterns of class dominance that have arisen in other areas of American economic and political life.

Stratification within health institutions . As members of the upper middle class, physicians occupy the highest stratum among workers in health institutions. Comprising 7 percent of the health labor force, physicians receive a median net income (approximately $53,900 in 1975) that places them in the upper 5 percent of the income distribution of the United States. Under physicians and professional administrators are members of the lower middle class: nurses, physical and occupational therapists and technicians. They make up 29 percent of the health labor force, are mostly women, and earn about $8,500. At the bottom of institutional hierarchies are clerical workers, aides, orderlies, kitchen and janitorial personnel, who are the working class of the health system. They have an income of about $5,700 per year, represent 54 percent of the health labor force, and are 84 percent female and 30 percent black. 10

Recent studies have analyzed the forces of professionalism, elitism, and specialization that divide health workers from each other and prevent them from realizing common interests. These patterns affect physicians, 11 nurses, and technical and service workers who comprise the fastest growing segment of the health labor force. 12 Bureaucratization, unionization, state intervention, and the potential “proletarianization” of professional health workers may alter future patterns of stratification.

Occupational mobility. Class mobility into professional positions is quite limited. Investigations of physicians’ class backgrounds in both Britain and the United States have shown a consistently small representation of the lower middle and working classes among medical students and practicing doctors. 13 As Ziem has found, despite some recent improvements for blacks and women, recruitment of working-class medical students as a whole has been very limited since shortly after publication of the Flexner Report. In 1920, 12 percent of medical students came from working-class families, and this percentage has stayed almost exactly the same until the present time.

Emergence of Monopoly Capital in the Health Sector

During the past century, economic capital has become more concentrated in a smaller number of companies—the monopolies. Monopoly capital has become a prominent feature of most capitalist health systems and is manifest in several ways.

Medical centers . Since about 1910, a continuing growth of medical centers has occurred, usually in affiliation with universities. Capital is highly concentrated in these medical centers, which are heavily oriented to advanced technology. Practitioners have received training where technology is available and specialization is highly valued. Partly as a result, health workers are often reluctant to practice in areas without easy access to medical centers. The nearly unrestricted growth of medical centers, coupled with their key role in medical education and the “technologic imperative” they encourage, has contributed to the maldistribution of health workers and facilities throughout the United States and within regions(12, 16).

Finance capital . Monopoly capital also has been apparent in the position of banks, trusts, and insurance companies—the largest profit-making corporations under capitalism. For example, in 1973, the flow of health-insurance dollars through private insurance companies was $29 billion, about one-half of the total insurance sold. Among commercial insurance companies, capital is highly concentrated; about 60 percent of the health-insurance industry is controlled by the ten largest insurers. Metropolitan Life and Prudential each control over $30 billion in assets, more than General Motors, Standard Oil of New Jersey, or International Telephone and Telegraph. 14

Finance capital figures prominently in current health reform proposals. Most plans for national health insurance would permit a continuing role for the insurance industry. Moreover, corporate investment in health maintenance organizations is increasing, under the assumption that national health insurance, when enacted, will assure the profitability of these ventures. 15

The “medical-industrial complex.” The “military-industrial complex” has provided a model of industrial penetration in the health system, popularized by the term, “medical-industrial complex.” Investigations by the Health Policy Advisory Center 16 and others have emphasized that the exploitation of illness for private profit is a primary feature of the health systems in advanced capitalist societies. 17 Recent reports have criticized the pharmaceutical amd medical equipment industries for advertising and marketing practices, 18 price and patent collusion, 19 marketing of largely untested drugs in the Third World, and promotion of expensive diagnostic and therapeutic innovations without controlled trials demonstrating their effectiveness.

In this context, “cost-effectiveness” analysis has yielded useful appraisals of several medical practices and clinical decision making, based in part on analysis of cost relative to effectiveness. 20 While recognizing its contributions, Marxist researchers have criticized the cost-effectiveness approach for asking some questions at the wrong level of analysis. This approach usually does not help clarify the over-all dynamics of the health system that encourage the adoption of costly and ineffective technologic innovations. The practices evalvated by cost-effectiveness research generally emerge with the growth of monopoly capital in the health system. Costly innovations often are linked to the expansion of medical centers, the penetration of finance capital in the health system, and the promotion of new drugs and instrumentation by medical industries. Cost-effectiveness research and clinical decision analysis remain incomplete unless they consider broader political and economic trends that propel apparent irrationalities in the health system. 21

The State and State Intervention

Marx and Engels emphasized the state’s crucial role in protecting the capitalist economic system and the interests of the capitalist class. The state comprises the interconnected public institutions that act to preserve the capitalist economic system and the interests of the capitalist class. This definition includes the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government, the military, and the criminal justice system, all of which hold varying degrees of coercive power. It also encompasses relatively non-coercive institutions within the educational, public welfare, and health-care systems. Through such non-coercive institutions, the state offers services or conveys ideologic messages that both stabilize and legitimate the capitalist system. Especially in periods of economic crisis, the state can use these same institutions to provide public subsidization of private enterprise.

The private-public contradiction. Within the health system, the “public sector,” as part of the state, operates through public expenditures and employs health workers in public institutions. The “private sector” is based in private practice and in companies that manufacture medical products or control medical finance capital. Nations vary greatly in the private-public duality. In the United States, a dominant private sector coexists with an increasingly large public sector. The public sector is even larger in Great Britain and Scandinavia. In Cuba and China, the private sector has been essentially eliminated. 22

A general theme of Marxist analysis is that the private sector drains public resources and health workers’ time, in behalf of private profit and to the detriment of patients using the public sector. This framework has helped explain some of the problems that have arisen in such countries as Great Britain 23 and Chile, where private sectors persisted after the enactment of national health services. In these countries, practitioners have faced financial incentives to increase the scope of private practice, which they often have conducted within public hospitals or clinics. In the United States, the expansion of public payment programs such as Medicare and Medicaid has led to increased public subsidization of private practice and private hospitals, as well as abuses of these programs by individual practitioners. 24

Similar problems have undermined other public health programs. These programs frequently have obtained finances through regressive taxation, placing low-income taxpayers at a relative disadvantage. Likewise, the deficiencies of the Blue Cross-Blue Shield insurance plans have derived largely from the failure of public regulatory agencies to control payments to practitioners and hospitals in the private sector. When enacted, national health insurance also would use public funds to reinforce and strengthen the private sector, by assuring payment for hospitals and individual physicians and possibly by permitting a continued role for commercial insurance companies. 25

Throughout the United States the problems of the private-public contradiction are becoming more acute. In most large cities, public hospitals are facing cutbacks, closure, or conversion to private ownership and control. This trend heightens low-income patients’ difficulties in finding adequate health care. It also reinforces private hospitals’ tendency to “dump” low-income patients to public institutions. 26

General functions of the state within the health system . The state’s functions in the health system have increased in scope and complexity. In the first place, through the health system, the state acts to legitimate the capitalist economic system based in private enterprise. 27 The history of public health and welfare programs shows that state expenditures usually increase during periods of social protest and decrease as unrest becomes less widespread. 28 Recently a Congressional committee summarized public opinion surveys that uncovered a profound level of dissatisfaction with government and particularly the role of business interests in government policies: ” … citizens who thought something was ‘deeply wrong’ with their country had become a national majority …. And, for the first time in the ten years of opinion sampling by the Harris Survey, the growing trend of public opinion toward disenchantment with government swept more than half of all Americans with it.” Under such circumstances, the state’s predictable response is to expand health and other welfare programs. These incremental reforms, at least in part, reduce the legitimacy crisis of the capitalist system by restoring confidence that the system can meet the people’s basic needs. The cycle of political attention devoted to national health insurance in the United States appear to parallel cycles of popular discontent. 29 Recent cutbacks in public health services to low-income patients follow the decline of social protest by low-income groups since the 1960s.

The second major function of the state in the health system is to protect and reinforce the private sector more directly. As previously noted, most plans for national health insurance would permit a prominent role and continued profits for the private insurance industry, particularly in the administration of payments, record keeping, and data collection. 30 Corporate participation in new health initiatives sponsored by the state—including health maintenance organizations, preventive screening programs, computerized components of professional standards review organizations, algorithm and protocol development for para-professional training, and audiovisual aids for patient education programs—is providing major sources of expanded profit. 31

A third (and subtler) function of the state is the reinforcement of dominant frameworks in scientific and clinical medicine that are consistent with the capitalist economic system, and the suppression of alternative frameworks that might threaten the system. The United States government has provided generous funding for research on the physiology and treatment of specific diseases. As critics even within government have recognized, the disease-centered approach has reduced the level of analysis to the individual organism and, often inappropriately, has stimulated the search for single rather than multiple causes. More recently, analyses emphasizing the importance of individual “life style” as a cause of disease 32 have received prominent attention by state agencies in the United States and Canada. Clearly, individual differences in personal habits do affect health in all societies. On the other hand, the lifestyle argument, perhaps even more than the earlier emphasis on specific etiology, obscures important sources of illness and disability in the capitalist work process and industrial environment; it also puts the burden of good health squarely on the individual, rather than seeking collective solutions to health problems. 33

The issues that the state has downplayed in its research and development programs are worth noting. For example, based on available data, it is estimated that in Western industrialized societies environmental factors are involved in approximately 80 percent of all cancers. In its session on “health and work in America,” the American Public Health Association in 1975 produced an exhaustive documentation of common occupational carcinogens. 34 A task force for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare on “Work in America,” published by a non-government press in 1973, reported: “In an impressive 15-year study of aging, the strongest predictor of longevity was work satisfaction. The second best predictor was overall ‘happiness’ … Other factors are undoubtedly important—diet, exercise, medical care, and genetic inheritance. But research findings suggest that these factors may account for only about 25 percent of the risk factors in heart disease, the major cause of death … “. 35 Such findings are threatening to the current organization of capitalist production. They have received little attention or support from state agencies. A framework for clinical investigation that links disease directly to the structure of capitalism is likely to face indifference or active discouragement from the state.

Medical Ideology

Ideology is an interlocking set of ideas and doctrines that form the distinctive perspective of a social group. Along with other institutions like the educational system, family, mass media, and organized religion, medicine promulgates an ideology that helps maintain and reproduce class structure and patterns of domination. Medicine’s ideologic features in no way diminish the efforts of individuals who use currently accepted methods in their clinical work and research. Nevertheless, medical ideology, when analyzed as part of the broad social superstructure, has major social ramifications beyond medicine itself. Recent studies have identified several components of modern medical ideology:

1) Disturbances of biological homeostasis are equivalent to breakdowns of machines. Modern medical science views the human organism mechanistically. The health professional’s advanced training permits the recognition of specific causes and treatments for physical disorders. The mechanistic view of the human body deflects attention from environmental causes of disease, including work processes or social stress. It also reinforces a general ideology that favors industrial technology under specialized control. 36

2) Disease is a problem of the individual human being. The unifactorial model of disease has always focused on the individual rather than the illness-generating conditions of society. More recently, attempts have been made to blame disease on an individual’s “life style” (smoking, overeating, etc.). In both cases, the responsibility for disease and cure rests at the individual rather than the collective level. In this sense medical science offers no basic critical appraisal of class structure and relations of production, even in their implications for health and illness. 37

3) Science permits the rational control of human beings. The natural sciences have led to a greater control over nature. Similarly, it is often assumed that modern medicine, by correcting defects of individuals, can enhance their controllability. The quest for a reliable work force has been one motivation for the support of modern medicine by capitalist economic interests. 38 Physicians’ certification of illness historically has expanded or contracted to meet industry’s need for labor. 39 Thus, medicine is seen as contributing to the rational governance of society, and managerial principles increasingly are applied to the organization of the health system. 40

4) Many spheres of life are appropriate for medical management . This ideologic assumption has led to an expansion of medicine’s social control function. Many behaviors that do not adhere to society’s norms have become appropriate for management by health professionals. The “medicalization of deviance” and health workers’ role as agents of social control have received critical attention. 41 The medical management of behavioral difficulties, such as hyperactivity, and aggression, often coincides with attempts to find specific biological lesions associated with these behaviors. 42 Historically, medicine’s social control function has expanded in periods of intense social protest or rapid social change.

5) Medical science is both esoteric and excellent . According to this ideologic principle, medical science involves a body of advanced knowledge and standards of excellence in both research and practice. Because scientific knowledge is esoteric, a group of professionals tend to hold elite positions. Lacking this knowledge, ordinary people are dependent on professionals for interpretation of medical data. The health system therefore reproduces patterns of domination by “expert” decision makers in the workplace, government, and many other areas of social life. The ideology of excellence helps justify these patterns, although the quality of much medical research and practice is far from excellent; this contradiction recently has been characterized as “the excellence deception” in medicine. 43 Ironically, a similar ideology of excellence has justified the emergence of new class hierarchies based on expertise in some countries, like the Soviet Union, that have undergone socialist revolutions. Other countries, such as the People’s Republic of China, have tried to overcome these ideologic assumptions and to develop a less esoteric “people’s medicine.”

Studies of medical ideology have focused on public statements by leaders of the profession (in professional journals or the mass media), as well as state and corporate officials whose organizations regulate or sponsor medical activities. However, health professionals also express ideologic messages in their face-to-face interaction with patients. 44 The transmission of ideologic messages within doctor-patient interaction currently is the subject of empirical research. 45

Comparative International Health Systems

Health care and imperialism . Imperialism may be defined as capital’s expansion beyond national boundaries, as well as the social, political, and economic effects of this expansion. One basic feature of imperialism is the extraction of raw materials and human resources which move from Third World nations to economically dominant countries. Navarro has analyzed how the “underdevelopment of health” in the Third World follows inevitably from this depletion of natural and human resources. The extraction of wealth limits underdeveloped countries’ ability to construct effective health systems. Many Third World countries face a net loss of health workers who migrate to economically dominant nations after expensive training at home. 46

Through imperialism, corporations also seek a cheap labor force. Workers’ efficiency was one important goal of public health programs sponsored abroad, especially in Latin America and Asia, by philanthropies closely tied to expanding industries in the United States. 47 Moreover, population control programs initiated by the United States and other dominant countries have sought a more reliable participation by women in the labor force. 48 At the same time, workers abroad who are employed by multinational corporations also face high risks of occupational disease.

Another thrust of imperialism is the creation of new markets for products manufactured in dominant nations and sold in the Third World. This process is nowhere clearer than in the pharmaceutical and medical equipment industries. The penetration of these multinationals, with its stultifying impact on local medical research and development, has led to the advocacy of nationalized drug and equipment formularies in several Third World countries.

As in the United States, medical professionals in the Third World most often come from higher income families. Even when they do not, they frequently view medicine as a route of upward mobility. As a result, medical professionals tend to ally themselves with the capitalist class—the “national bourgeoisie”—of Third World countries. They also frequently support cooperative links between the local capitalist class and business interests in economically dominant countries. The class position of health professionals has led them to resist social change that would threaten current class structure, either nationally or internationally. Similar patterns have emerged in some post-revolutionary societies. In the U.S.S.R., professionals’ new class position, based on expertise, has caused them to act as a relatively conservative group in periods of social change. Elitist tendencies in the post-revolutionary Cuban profession also have received criticism from Marxist analysts. 49

Frequently imperialism has involved direct military conquest; recently health workers have assumed military or paramilitary roles in Indochina and Northern Africa. Health institutions also have taken part as bases for counterinsurgency and intelligence operations in Latin America and Asia.

Health care and the transition to socialism . The number of nations undergoing socialist revolutions has increased dramatically in recent years, particularly in Asia and Africa but also in parts of Latin America, the Caribbean, and Southern Europe. Socialism is no panacea. Numerous problems have arisen in all countries that have experienced socialist revolutions. The contradictions that have emerged in most postrevolutionary countries are deeply troubling to Marxists; these contradictions have been the subject of intensive analysis and debate.

On the other hand, socialism can produce major modifications in health-system organization, nutrition, sanitation, housing, and other services. These changes can lead, through a sometimes complex chain of events, to remarkable improvements in health. The remarkable improvements in morbidity and mortality that followed socialist revolutions in such countries as Cuba and China now are well known. 50 The transition to socialism in every case has resulted in reorganization of the health system, emphasizing better distribution of health care facilities and personnel. Local political groups in the commune, neighborhood, or workplace have assumed responsibility for health education and preventive medicine programs. Class struggle continues throughout the transition to socialism. During Chile’s brief period of socialist government, many professionals resisted democratization of health institutions and supported the capitalist class that previously and subsequently ruled the country. 51 Countries like China and Cuba eliminated the major source of social class—the private ownership of the means of production. However, as mentioned previously, new class relations began to emerge that were based on differential expertise. Health professionals received larger salaries and maintained higher levels of prestige and authority. One focus of the Chinese Cultural Revolution was the struggle against the new class of experts that had gained power in the health system and elsewhere in the society. 52 Other countries, including Cuba, have not confronted these new class relations as explicitly (see article on Health Care in Tanzania elsewhere in this issue).

Contradictions of capitalist reform. While retaining the essential features of their capitalist economic systems, several nations in Europe and North America have instituted major reforms in their health systems. Some reforms have produced beneficial effects that U.S. policy makers view as possible models for this country. However, recent Marxist studies, while acknowledging many improvements, have revealed troublesome contradictions that seem inherent in reforms attempted within capitalist systems.

Great Britain’s national health service has attracted great interest. Serious problems have balanced many of the undeniable benefits that the British health service has achieved. Chief among these problems is the professional and corporate dominance that has persisted since the service’s inception. Decision-making bodies contain large proportions of professional specialists, bankers, and corporate executives, many of whom have direct or indirect links with pharmaceutical and medical equipment industries. 53

The private-public contradiction, discussed earlier, has remained a source of conflict in several countries that have established national health services or universal insurance programs. Use of public facilities for private practice has generated criticism focusing on public subsidization of the private sector. In Britain, for example, this concern (along with more general organizational problems that impeded comprehensive care) was a primary motivation for the recent reorganization of the national health service. 54 In Chile, the attempt to reduce the use of public facilities for private practice led to crippling opposition from the organized medical profession. The private-public contradiction will continue to create conflict and to limit progress when countries institute national health services while preserving a strong private sector.

The limits of state intervention also have become clearer from the examples of Quebec and Sweden. Both have tried to establish far-reaching programs of health insurance, while preserving private practice and corporate dealings in pharmaceuticals and medical equipment. Recent studies have demonstrated the inevitable constraints of such reform. Maldistribution of facilities and personnel have persisted, and costs have remained high. The accomplishments of Quebec’s and Sweden’s reforms cannot pass beyond the state’s responsibility for protecting private enterprise. 55 This observation leads to skepticism about health reforms in the United States that rely on private market mechanisms and that do not challenge the broader structures within which the health system is situated. 56

Historical Materialist Epidemiology

Historical materialist epidemiology relates patterns of death and disease to the political, economic, and social structures of society. The field emphasizes changing historical patterns of disease and the specific material circumstances under which people live and work. These studies try to transcend the individual level of analysis, to find how historical social forces influence or determine health and disease.

Many different diseases have been examined from this viewpoint. The incidence of mental illness, for example, has been shown to correlate with economic growth or recession. 57 The cause of stress and stress-related problems, such as coronary heart disease, anxiety, suicide, hypertension, and cancer, generally has been viewed as a problem at the individual level. Historical materialist epidemiology shifts the emphasis to stressful forms of social organization linked to capitalist production and industrialization. 58

The social causes of occupational disease have become more apparent. Diseases such as asbestosis, mesothelioma, and complications of vinyl chloride all point to the contradiction between profitability and improved health in capitalist countries. Sexism also can be seen as a factor in the differential production of ill health among women and men. Men, for instance, generally die younger than women, and this may be a result of their greater exposure to occupational hazards in jobs from which women traditionally have been excluded. Historically, a woman’s access to health facilities and the way she is treated by doctors have been strongly influenced by her social class. The history of the birth control movement, 59 the sexist assumptions of psychiatric diagnosis (see article on the Worcester Ward in this issue) and the misuse of gynecologic surgery all illustrate the social and sexist nature of women’s health problems. 60

One unifying theme in this field is modern medicine’s limitations. 61 Traditional epidemiology has searched for causes of morbidity and mortality that are amenable to medical intervention. While acknowledging the importance of traditional techniques, historical materialist epidemiology has demonstrated causes of disease and death that derive from broad social structures beyond the reach of medicine alone.

Health Praxis

Marxist research conveys another basic message: that research is not enough. “Praxis,” as proposed throughout the history of Marxist scholarship, is the disciplined uniting of thought and practice, study and action.

Contradictions of patching . Health workers concerned about progressive social change face difficult dilemmas in their day-to-day work. Clients’ problems often have roots in the social system. Examples abound: drug addicts and alcoholics who prefer numbness to the pain of confronting problems like unemployment and inadequate housing; persons with occupational diseases that require treatment but will worsen upon return to illness-generating work conditions; people with stress-related cardiovascular disease; elderly or disabled people who need periodic medical certification to obtain welfare benefits that are barely adequate; prisoners who develop illness because of prison conditions. 62 Health workers usually feel obliged to respond to the expressed needs of these and many similar clients.

In doing so, however, health workers engage in “patching.” On the individual level, patching usually permits clients to keep functioning in a social system that is often the source of the problem. At the societal level, the cumulative effect of these interchanges is the patching of a social system whose patterns of oppression frequently cause disease and personal unhappiness. The medical model that teaches health workers to serve individual patients deflects attention from this difficult and frightening dilemma. 63

The contradictions of patching have no simple resolution. Clearly health workers cannot deny services to clients, even when these services permit clients’ continued participation in illness-generating social structures. On the other hand, it is important to draw this connection between social issues and personal troubles. Health praxis should link clinical activities to efforts aimed directly at basic sociopolitical change.

Reformist versus nonreformist reform . When oppressive social conditions exist, reforms to improve them seem reasonable. However, the history of reform in capitalist countries has shown that reforms most often follow social protest, make incremental improvements that do not change overall patterns of oppression, and face cutbacks when protest recedes. Health praxis includes a careful study of reform proposals and the advocacy of reforms that will have a long-term progressive impact.

A distinction developed by Gorz clarifies this problem. “Reformist reforms” provide small material improvements while leaving intact current political and economic structures. These reforms may reduce discontent for periods of time, while helping to preserve the system in its present form. “A reformist reform is one which subordinates objectives to the criteria of rationality and practicability of a given system and policy … (it) rejects those objectives and demands—however deep the need for them—which are incompatible with the preservation of the system”. 64 “Nonreformist reforms,” on the other hand achieve true and lasting changes in the present system’s structures of power and finance. Rather than obscuring sources of exploitation by small incremental improvements, nonreformist reforms expose and highlight structural inequities. Such reforms ultimately increase frustration and political tension in a society; they do not seek to reduce these sources of political energy. As Gorz puts it: ” … although we should not reject intermediary reforms … , it is with the strict proviso that they are to be regarded as a means and not an end, as dynamic phases in a progressive struggle, not as stopping places”. 65 From this viewpoint health workers can try to discern which current health reform proposals are reformist and which are nonreformist. They also can take active advocacy roles, supporting the latter and opposing the former. Although the distinction is seldom easy, it has received detailed analysis with reference to specific proposals. 66

Reformist reforms would not change the overall structure of the health system in any basic way. For example, national health insurance chiefly would create changes in financing, rather than in the organization of the health system. This reform may reduce the financial crises of some patients; it would help assure payment for health professionals and hospitals. On the other hand, national health insurance will do very little to control profit for medical industries or to correct problems of maldistributed health facilities and personnel. Its incremental approach and reliance on private market processes would protect the same economic and professional interests that currently dominate the health system. 67

Other examples of reformist reforms are health maintenance organizations, prepaid group practice, medical foundations, and professional standards review organizations. 68 With the rare exception of those organized as consumer cooperatives, these innovations preserve professional dominance in health care. There have been few incentives to improve existing patterns of maldistributed services. Moreover, large private corporations have entered this field rapidly, sponsoring profit-making health maintenance organizations and marketing technologic aids for peer review. 69

Until recently, there has been little support for a national health service in the United States. For several years, however, Marxist analysts have worked with members of Congress in drafting preliminary proposals for a national health service. These proposals, if enacted, would be progressive in several ways. They promise to place stringent limitations on private profit in the health sector. Most large health institutions gradually would come under state ownership. Centralized health planning would combine with policy input from local councils to foster responsiveness and to limit professional dominance. Financing by progressive taxation is designed explicitly to benefit low-income patients. Periods of required practice in underserved areas would address the problem of maldistribution. The eventual development of a national drug and medical equipment formulary promises to curtail monopoly capital in the health sector.

Although these proposals face dim political prospects, support is growing. For instance, the Governing Council of the American Public Health Association has passed two resolutions supporting the concept of a national health service that would be community-based and financed by progressive taxation. 70 While advancing a model for a more responsive health care system, this reform also contains contradictions that probably would generate frustration and pressure for change. In particular, these proposals would permit the continuation of private practice and help expose the inequities of the private-public dichotomy.

Health care and political struggle. Fundamental social change,however, comes not from legislation but from direct political action. Currently, coalitions of community residents and health workers are trying to gain control over the governing bodies of health institutions that affect them. 71 Unionization activity and minority group organizing in health institutions are exerting pressure to modify previous patterns of stratification. 72

Recognizing the impact of medical ideology has motivated attempts to demystify current ideologic patterns and to develop alternatives. This “counterhegemonic” work often involves opposition to the social control function of medicine in such areas as drug addiction, genetic screening, contraception and sterilization abuse, psychosurgery, and women’s health care. A network of alternative health programs has emerged that tries to develop self-care and nonhierarchical, anticapitalist forms of practice; these ventures then would provide models of progressive health work when future political change permits their wider acceptance. 73

In anti-imperialist organizing, several groups have assisted persecuted health workers and have spoken out against medical complicity in torture. Health and science workers also have used historical materialist epidemiology in occupational health projects and unionization struggles. A common criticism of the Marxist perspective is that it presents many problems with few solutions. Clearly, however, this approach has clarified some useful directions of political strategy. This struggle will be a protracted one, and will involve action on many fronts. The present holds little room for complacence or misguided optimism. Our future health system, as well as the social order of which it will be a part, depends largely on the praxis we choose now.

>> Back to Vol. 10, No. 6 <<

- Rosen, G., From Medical Police to Social Medicine: Essays on the History of Health Care . New York, Science History Publications, 1974.

- McKeown, T., “An Historical Appraisal of the Medical Task,” Medical History and Medical Care . Edited by T. McKoewn, G. McLachlan. New York, Oxford University Press, 1971; Illich, I., Medical Nemesis . New York, Pantheon, 1976; Powles, J., “On the Limitations of Modern Medicine.” Sci. Med. & Man 1:1-30,1973.

- Flexner, A., Medical Education in the United States and Canada . New York, Carnegie Foundation, 1910.

- Berliner, H., “A Larger Perspective on the Flexner Report.” Int. J. Health Serv . 5:573-592, 1975; Ehrenreich, B., English D., Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers . Old Westbury, NY, Feminist Press, 1973; Brown, E. R., “Public Health in Imperialism: Early Rockefeller Programs at Home and Abroad.” Am. J. Public Health 66:897-903, 1976.

- Horn, J. S., A way with All Pests: An English Surgeon in People’s China . New York, Monthly Review Press, 1969.

- Guevara, E., “On Revolutionary Medicine,” Venceremos . Edited by J. Gerassi. New York, Simon & Schuster, 1969; Harper, G., “Ernesto Guevara, M.D.: Physician – Revolutionary Physician- Revolutionary.” N. Engl. J. Med. 281:1285-1289, 1969.

- Divoky, D., and P. Schrag The Myth of the Hyperactive Child . New York, Pantheon, 1976.

- Poulantzas, N., Classes in Contemporary Capitalism . London: New Left Books, 1975.

- Bettelheim, C., Class Struggles in the USSR. New York, Monthly Review Press, 1976.

- Navarro, V., Medicine Under Capitalism . New York, Prodist, 1976.

- Waitzkin, H., and B. Waterman, The Exploitation of Illness in Capitalist Society . Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill, 1974.

- Stevenson, G., “Social relations of production and consumption in the human service occupations.” Monthly Rev. 28:78-87, JulyAugust 1976.

- Robson, J., “The NHS Company, Inc.? The Social Consequences of the Professional Dominance in the National Health Service.” Int. J. Health Serv . 3:413-426,1973.

- Salmon, J. W., “Health Maintenance Organization Strategy: A Corporate Takeover of Health Services.” Int. J. Health Serv. 5:609- 624, 1975.

- Prognosis Negative . Edited by D. Kotelchuck. New York, Vintage, 1976.

- Prognosis Negative . Edited by D. Kotelchuck. New York, Vintage, 1976; Silverman, M., and P.R. Lee, Pills, Profits. and Politics . Berkeley, University of California Press, 1974.

- Lichtman, R. “The Political Economy of Medical Care,” The Social Organization of Health . Edited by HP Dreitzel. New York, Macmillan, 1971.

- Bloom, B. S. and D. L. Peterson, “End Results, Cost and Productivity of Coronary-Care Units.” N. Engl. J. Med . 288:72-78, 1973.

- 90 (missing)

- Roemer, M.l., and J.A. Mera, “Patient Dumping and Other Voluntary Agency Contributions to Public Agency Problems.” Med. Care 11:30-39, 1973.

- Waitzkin, H., and B. Waterman, The Exploitation of Illness in Capitalist Society . Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill, 1974; Renaud, M., “On the Structural Constraints to State Intervention in Health.” Int. J. Health Serv. 5:559-571, 1975.

- Piven, F. F*. and R. A. Cloward, Regulating the Poor . New York, Vintage, 1971.

- Illich, I., Medical Nemesis . New York, Pantheon, 1976; Fuchs, V.R., Who Shall Live? Health, Economics, and Social Choice . New York, Basic Books, 1974.

- Navarro, V., Medicine Under Capitalism . New York, Prodist, 1976; Waitzkin, H., “Recent Studies in Medical Sociology: The New Reductionism.” Contemp. Sociol. 5:401-405, 1976.

- American Public Health Association, Chart Book. Health and Work in America . Washington, DC, The Association, 1975.

- Special Task Force to the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare: Work in America . Cambridge, MIT Press, 1973, pp. 73-79.

- Navarro, V., Medicine Under Capitalism . New York, Prodist, 1976; Berliner, H., “Emerging Ideologies in Medicine.” Rev. Radical Polit. Econ . 8:116-124, Spring 1977.

- Brown, E. R., “Public Health in Imperialism: Early Rockefeller Programs at Home and Abroad.” Am. J. Public Health 66:897-903, 1976.

- Ehrenreich, B., and D. English Complaints and Disorders: The Sexual Politics of Sickness. Old Westbury, NY, Feminist Press, 1973.

- Krause, E., “Health Planning as a Managerial Ideology.” Int. J. Health Serv. 3:445-463, 1973.

- Poulantzas, N., Classes in Contemporary Capitalism . London: New Left Books, 1975; Waitzkin, H., and B. Waterman, The Exploitation of Illness in Capitalist Society . Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill, 1974; Zola, I. K., “In the Name of Health and Illness: On Some Socio-political Consequences of Medical Influence. Soc. Sci. Med. 9: 83-87, 1975; Pfohl, S. J. “The Discovery of Child Abuse.” Soc. Problems 24: 310-323, 1977.

- Divoky, D., and P. Schrag The Myth of the Hyperactive Child . New York, Pantheon, 1976; Beckwith, J., and L. Miller, “Behind the Mask of Objective Science,” The Sciences (New York), 16-19, 29-31, Nov.-Dec. 1976.

- Holman, H.R., “The Excellence Deception in Medicine.” Hosp. Practice 11:11-21, April 1976.

- Zola, I. K., “In the Name of Health and Illness: On Some Socio-political Consequences of Medical Influence. Soc. Sci. Med. 9: 83-87, 1975.

- Waitzkin, H., and J. D. Stoeckle, “The Communication of Information About Illness: Clinical, Sociological, and Methodological Considerations.” Adv. Psychosom. Med . 8: 180-215, 1972.

- Mass, B., Population Target: The Political Economy of Population Control in Latin America . Toronto, Latin American Working Group, 1976.

- Navarro, V., “Health Services in Cuba: An Initial Appraisal.” N. Engl. J. Med. 287:954-959, 1972.

- Navarro, V., “Health Services in Cuba: An Initial Appraisal.” N. Engl. J. Med. 287:954-959, 1972; Danielson, R. Cuban Medicine . New Brunswick, NJ, Transaction Books, in press; Sidel, V. W., and R. Sidel, Serve the People: Observations of Medicine in the People’s Republic of China. Boston, Beacon, 1973; Wen C. P., and C. W. Hays, “Medical Education in China in the Postcultural Revolution Era.” N. Engl. J. Med. 292:998-1006,1975.

- Navarro, V., Medicine Under Capitalism . New York, Prodist, 1976; APHA Task Force on Chile, “History of the Health Care System in Chile.” Am. J. Public Health 67:31-36, 1977.

- Waitzkin, H., “Recent Studies in Medical Sociology: The New Reductionism.” Contemp. Sociol. 5:401-405, 1976.

- Robson, J., “The NHS Company, Inc.? The Social Consequences of the Professional Dominance in the National Health Service.” Int. J. Health Serv . 3:413-426,1973; Gill, D.G., “The Reorganization of the National Health Service.” Sociol. Rev. [ Monogr] 22:9-22, 1976.

- Gill, D.G., “The Reorganization of the National Health Service.” Sociol. Rev. [ Monogr] 22:9-22, 1976.

- Renaud, M., “On the Structural Constraints to State Intervention in Health.” Int. J. Health Serv. 5:559-571, 1975.

- Waitzkin, H., and B. Waterman, The Exploitation of Illness in Capitalist Society . Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill, 1974; Navarro, V., “A Critique of the Present and Proposed Strategies for Redistributing Resources in the Health Sector and a Discussion of Alternatives.” Med. Care 12:721-742, 1974.

- Brenner, H., Mental Illness and the Economy . Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1973.

- Eyer, J. and P. Sterling “Stress-related Mortality and Social Organization.” Rev. Radical Polit. Econ . 8:1-44, Spring 1977; Health Movement Organization Packet #2, “The Social Etiology of Disease.” Health/PAC , 17 Murray St., N.Y., 1977.

- Gordon, L., Woman’s Body, Woman’s Right: A Social History of Birth Control in America. New York, Viking, 1976.

- Powles, J., “On the Limitations of Modern Medicine.” Sci. Med. & Man 1:1-30,1973.

- Waitzkin, H., and B. Waterman, The Exploitation of Illness in Capitalist Society . Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill, 1974; Twaddle, A. C. “Utilization of Medical Services by a Captive Population: An Analysis of Sick Call in a State Prison.” J. Health Soc. Behav. 17:236-248, 1976.

- Gorz, A., Socialism and Revolution . Garden City, NY, Anchor, 1973.

- Waitzkin, H., and B. Waterman, The Exploitation of Illness in Capitalist Society . Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill, 1974; Prognosis Negative . Edited by D. Kotelchuck. New York, Vintage, 1976; Navarro, V., “A Critique of the Present and Proposed Strategies for Redistributing Resources in the Health Sector and a Discussion of Alternatives.” Med. Care 12:721-742, 1974.

- Governing Council, American Public Health Association, “Resolutions and Policy Statements: Committee for a National Health Service.” Am. J. Public Health 67:84-87, 1977.

- Waitzkin, H., “What To Do When Your Local Medical Center Tries to Tear Down Your Home.” Science for the People 9:22-23, 28- 39, March-April 1977.

- Chamberlin, R.W., and J. F. Radebaugh, “Delivery of Primary Care- Union Style.” N. Engl. J. Med. 294:641-645, 1976.

- Marieskind, H. I., and B. Ehrenreich, “Toward Socialist Medicine: The Women’s Health Movement.” Soc. Policy 6:34-42, Sept.- Oct. 1975; Douglas, C., and J. Scott, “Toward an Alternative Health Care System.” Win Magazine 11:14-19, Aug. 7, 1975.

A Marxist view of medical care

- PMID: 354452

- DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-2-264

Marxist studies of medical care emphasize political power and economic dominance in capitalist society. Although historically the Marxist paradigm went into eclipse during the early twentieth century, the field has developed rapidly during recent years. The health system mirrors the society's class structure through control over health institutions, stratification of health workers, and limited occupational mobility into health professions. Monopoly capital is manifest in the growth of medical centers, financial penetration by large corporations, and the "medical-industrial complex." Health policy recommendations reflect different interest groups' political and economic goals. The state's intervention in health care generally protects the capitalist economic system and the private sector. Medical ideology helps maintain class structure and patterns of domination. Comparative international research analyzes the effects of imperialism, changes under socialism, and contradictions of health reform in capitalist societies. Historical materialist epidemiology focuses on economic cycles, social stress, illness-generating conditions of work, and sexism. Health praxis, the disciplined uniting of study and action, involves advocacy of "nonreformist reforms" and concrete types of political struggle.

Publication types

- Historical Article

- Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S.

- Delivery of Health Care / history

- Delivery of Health Care / organization & administration*

- Health Services*

- History, 19th Century

- History, 20th Century

- Internationality

- Philosophy, Medical*

- Public Policy

- Social Change

- Social Conditions

- United States

The UK Faculty of Public Health has recently taken ownership of the Health Knowledge resource. This new, advert-free website is still under development and there may be some issues accessing content. Additionally, the content has not been audited or verified by the Faculty of Public Health as part of an ongoing quality assurance process and as such certain material included maybe out of date. If you have any concerns regarding content you should seek to independently verify this.

Section 1: The theoretical perspectives and methods of enquiry of the sciences concerned with human behaviour

PLEASE NOTE:

We are currently in the process of updating this chapter and we appreciate your patience whilst this is being completed.

Section 1: The theoretical perspectives and methods of enquiry of the sciences concerned with human behaviour

This section covers:

- Disciplines concerned with human behaviour

- Theoretical perspectives

- Defining the field of medical sociology

- Research methodologies

1. Disciplines concerned with human behaviour

Psychology, anthropology, history and sociology are all disciplines concerned with human behaviour. While these approaches differ in terms of their perspectives and methodologies, there is also considerable overlap between them. Rather than contradict each other, they complement one another in developing our understanding of human behaviour and a multi-disciplinary approach to public health. Applying theories and research from these disciplines can help to explain the behaviours of individuals, groups within populations, and healthcare organisations. In doing so we can begin to understand how different concepts of health, wellbeing and illness evolved through changes in societies and cultures.

Psychology is the scientific study of people, the mind and behaviour. It is both an academic discipline and an applied science or professional practice. [1] By developing our understanding of how we think, feel, act and interact, individually and in groups, psychology can contribute to developing solutions for social problems. In terms of public health theory and practice, health psychology and social psychology are particularly relevant, although there is also considerable overlap with other psychological disciplines including developmental and cognitive psychology. Health psychology is concerned with people’s attitudes, beliefs and behaviours about health, including models to predict and enable behaviour change. Social psychology is concerned with the behaviour of individuals and groups as part of their wider societies.

Anthropology is the study of various aspects of human life (e.g. societies, cultures and languages) within societies of the past and present. Within this discipline, social anthropology and medical anthropology are especially relevant to public health. Social anthropology is the study of human society and cultures, seeking to understand how people live in societies and how they make their lives meaningful. Medical anthropology draws upon other anthropological sub-disciplines including social, cultural, biological, and linguistic anthropology to examine individual, population and environmental health from the perspective of interactions between humans and other species; cultural norms and social institutions; micro and macro politics; and forces of globalisation.

History is the recording and interpretation of past events. Understanding history puts current social structures, norms and behaviours into context, and is crucial for learning lessons for the future. The history of medicine demonstrates how approaches to health and illness in societies have changed over time. Developments in medicine, science and technology have both influenced and been influenced by understanding of anatomy; beliefs about health and illness; treatment paradigms; and the social and political environments in which healthcare systems operate.

Sociology is the study of social behaviour or society, including its origins, development, organisation, networks, and institutions. It is a social science that uses empirical research and critical analysis to understand social order, disorder and change. The simplest view of the academic discipline of sociology is that it is somehow concerned with the understanding of human societies. However, this does not take us very far as most people feel they know a good deal about the society in which they live because they experience it every day; this can be described as 'common-sense' or experiential knowledge. Another approach would be to define sociology as a research-based study of society. However, there are other academic disciplines such as history, politics, economics, anthropology and social psychology that also have human society as the object of study. Probably the best way of defining the contribution of sociology is by looking at the key questions that originally stimulated the development of the academic discipline and which continue to underpin sociological research today:

- What gives social life a sense of stability and order?

- How does social change and development come about?

- What is the nature of the relationship between the individual and the society in which they live?

- To what extent does the society into which people are born shape their beliefs, behaviours, and life chances (including health outcomes)

Understanding and explaining social phenomena

- Sociology, in pursuing an objective scientific approach to answering the questions posed above, attempts to explain why social life is not a random series of events, but is structured and shaped by particular sets of rules (both obvious and hidden). This is not to say that social structures determine human behaviour, rather that social structure is both the ever-present condition for , and reproduced outcome of , intentional human agency or actions.

- Sociology, like any other academic discipline, is theory-based. That is, in order to understand how societies work (or why particular bio-chemical processes occur), we must go beyond a simplistic description of the phenomenon under investigation.

- Sociology, also like any other academic discipline which has as its object of study the human and social world, consists of a range of competing explanatory paradigms. Empirical research necessarily involves making assumptions about the nature of social reality.

- Sociology challenges both naturalistic and individualistic explanations of social phenomena ( see Activity 1) . These understandings arise as a consequence of growing up (`being socialised') within a particular culture and set of social structures, and can result in people seeing their everyday roles and behaviour as being somehow `natural'. Equally, when looking at other people`s behaviour, i.e. `unhealthy lifestyles' or lack of motivation for example, the focus is all too often on particular individual characteristics, ignoring the social factors that influence such behaviour and beliefs.

2. Theoretical approaches within Sociology

A single unified sociological perspective concerning the nature of social reality does not exist. In this respect sociology is no different to any other academic discipline, for all embrace competing perspectives or paradigms - this is how subject knowledge is advanced.

The major long-standing epistemological divide that exists within sociological theory is that between those sociologists who argue that society can be studied in an objective way through identifying and examining the structures of society, and those who argue for an interpretative or subjective approach to social phenomena more focused on social actors . Structuralist approaches often tend to focus on the macro level while subjectivist approaches tend to focus on the micro level of interaction. However, in more recent times a third position has developed which attempts to breakdown this duality between the relative importance attached to social actors versus social structures. These three approaches are explored below.

a. Social structural approaches: Societies as objective realities

Social structural approaches to exploring social reality include those empiricist sociologists who believe that an objective 'science of society' is possible in much the same way as a physical science such as biology or physics. This empirical sociology seeks to explain the norms of social life in terms of various identifiable linear causal influences. Social structural approaches would also include those sociologists who see human society as being shaped by an underlying material social and economic structure. These are structures that may not always be visible, but nevertheless are fundamental in explaining social and individual processes.

In relation to health, a predominantly social structural approach would draw upon quantitative data derived from social surveys, epidemiological studies and comparative studies in order to point to the relative influence of societal structures and processes in determining health outcomes for social groups.

Within the academic discipline of sociology, two major theoretical perspectives exist which seek to analyse human societies utilising a social structural or systems approach. These perspectives are structural functionalism and Marxism, and their very different organising principles are described in relation to the social determination of health outcomes below. As a brief illustration of the two approaches to structural analysis we will briefly examine the issue of poverty. The functionalist explanation would set poverty in the context of social stratification and the unequal distribution of rewards associated with complex economies where different tasks are performed by different groups within society. Some groups are relatively less well off than others because they have less skills and knowledge and so their contribution to the functioning of society is not as extensive as other groups. The Marxist explanation, on the other hand, would set poverty in the context of the class structure, specifically the relationship of social groups within a capitalist system of economic production in which there are the exploited and the exploiters (with some intermediate groups of managers and supervisors).

The functionalist perspective of health and illness

This theoretical perspective stresses the essential stability and cooperation within modern societies. Social events are explained by reference to the functions they perform in enabling continuity within society. Society itself is likened to a biological organism in that the whole is seen to be made up of interconnected and integrated parts; this integration is the result of a general consensus on core values and norms. Through the process of socialisation we learn these rules of society which are translated into roles. Thus, consensus is apparently achieved through the structuring of human behaviour. Within medical sociology, this approach is essentially concerned with the theme of the 'sick role', and the associated issue of illness behaviour. Talcott Parsons, the leading figure within this sociological tradition, identified illness as a social phenomenon rather than as a purely physical condition. Health, as against illness, being defined as:

'The state of optimum capacity of an individual for the effective performance of the roles and tasks for which s/he has been socialised.' Parsons, 1951

Health within the functionalist perspective thus becomes a prerequisite for the smooth functioning of society. To be sick is to fail in terms of fulfilling one's role in society; illness is thus seen as 'unmotivated deviance'. The regulation of this sickness/deviance comes about through the mechanism of the 'sick role' concept and the associated 'social control' role of doctors in allowing an individual to take on a sick status.

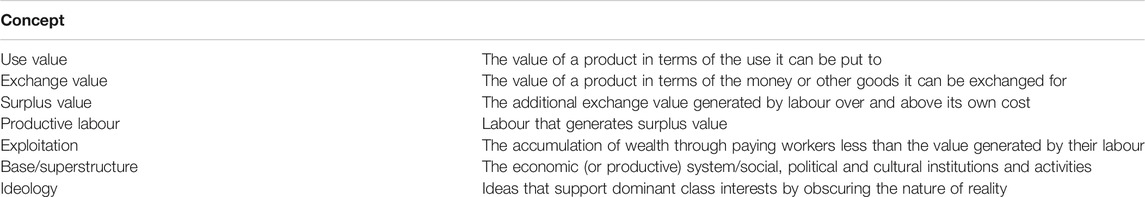

The Marxist perspective of health and illness

A key assertion of the Marxist perspective is that material production is the most fundamental of all human activities - from the production of the most basic of human necessities such as food, shelter and clothing in a subsistence economy, to the mass production of commodities in modern capitalist societies. Whether this production takes place within a modern or a subsistence economy, it involves some sort of organisation and the use of appropriate tools; this is termed the 'forces of production'. Production of any type was recognised by Marx as also involving social relations. In modern capitalist societies these 'relations of production' lead to the development of a division of labour reflected in the existence of different social classes. For Marxists, it is these forces and relations of production together that constitute the economic base (infrastructure) of society. The superstructure of a society - the political, legal, educational, and health systems and so on - are shaped and determined by this economic base.

The orientation of this approach as applied within medical sociology is towards the social origins of disease. Health outcomes for the population are seen as being influenced by the operation of the capitalist economic system at two levels.

First, at the level of the production process itself, health is affected either directly in terms of industrial diseases and injuries, stress-related ill health, or indirectly through the wider effects of the process of commodity production within modern societies. The production processes create environmental pollution, whilst the process of consuming the commodities themselves has long-term health consequences associated with eating processed foods, chemical additives, car accidents and so on. Second, health is influenced at the level of distribution. Income and wealth are major determinants of people's standard of living - where they live, their access to educational opportunities, their access to health care, their diet, and their recreational opportunities. All of these factors are significant in the social patterning of health.

b. Interpretative aproaches: Societies as subjective realities

Sociologists within this wide tradition would argue that the social world cannot be studied in the same way as the physical world because people:

'Engage in conscious intentional activity and, through language, attach meanings to their actions... [therefore] sociologists should be less concerned to explain behaviour than to understand how people come to interpret the world in the way they do.' Taylor and Field, 1993:15

In attempting to achieve this goal of interpretative understanding, reliance is placed on essentially qualitative research methodologies in order to get as close as possible to the world of the subjects or social actors being studied. In terms of health and illness, this interpretative approach focuses upon the (symbolic) meanings of what it is to be ill in our society, and would not confine its interest in health to what would be perceived as the closed world of clinical biomedicine (this would not rule out the study of the interactions of clinicians themselves both with patients and with colleagues).

Within this interpretative sociological tradition two distinct perspectives stand out; symbolic interactionism and social constructionism. These approaches are outlined below in relation to health and illness.

The Symbolic Interactionist perspective of health and illness

This perspective developed from a concern with language and the ways in which it enables us to become self-conscious beings. The basis of any language is the use of symbols that reflect the meanings that we endow physical and social objects with. In any social setting in which communication takes place, there is an exchange of these symbols: that is, we look for clues in interpreting the behaviour and intentions of others. Communication being a two-way process, this interpretative process involves a negotiation between the parties concerned. The negotiated order that develops therefore involves:

'People construct[ing] understandings of themselves and of others out of experiences they have and the situations they find themselves in. These understandings have consequences in turn for the way in which people act, and the manner in which others react to them.' Aggleton, 1990:91

Interactionist sociology asserts that the social identities we possess are influenced by the reactions of others. So if we demonstrate some abnormal or 'deviant' behaviour it is likely that the particular label that is attached within a society at a particular time to this behaviour will then become attached to us as individuals. This can bring about important changes in our self-identity. A disease diagnosis could be one such label: for example, clinical depression and the assumptions about the person so labelled that then follow; here Goffman's (1968) work on this form of social stigma is particularly influential and will be discussed in detail in Section 3 of this module.

Within this perspective, medicine too would be viewed as a social practice and its claims to be an objective science would be disputed. In the doctor-patient interaction, patient dissatisfaction can result if the doctor too rigidly superimposes a pre-existing framework (disease categories) upon the subjective illness experience of the patient. For example, by presuming that they can understand what that individual is suffering because of an interpretation of their signs and symptoms without reference to their health beliefs (explored in Section 4 ).

See Activity 2

The Social Constructionist perspective of health and illness - The relativity of social reality