Science Fair Central

Scientific Steps

Students who want to find out things as a scientist, will want to conduct a hands-on investigation. While scientists study a whole area of science, each investigation is focused on learning just one thing at a time. This is essential if the results are to be trusted by the entire science community.

Follow the Scientific Steps below to complete your scientific process for your investigation.

What do scientists think they already know about the topic? What are the processes involved and how do they work? Background research can be gathered first hand from primary sources such as interviews with a teacher, scientist at a local university, or other person with specialized knowledge. Or use secondary sources such as books, magazines, journals, newspapers, online documents, or literature from non-profit organizations. Don’t forget to make a record of any resource used so that credit can be given in a bibliography.

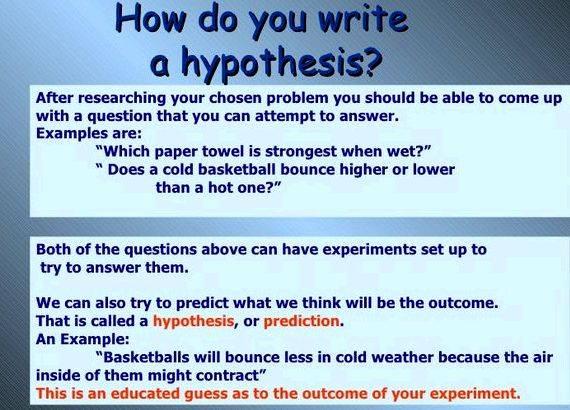

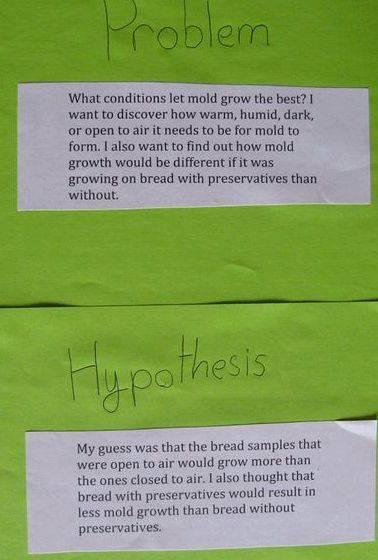

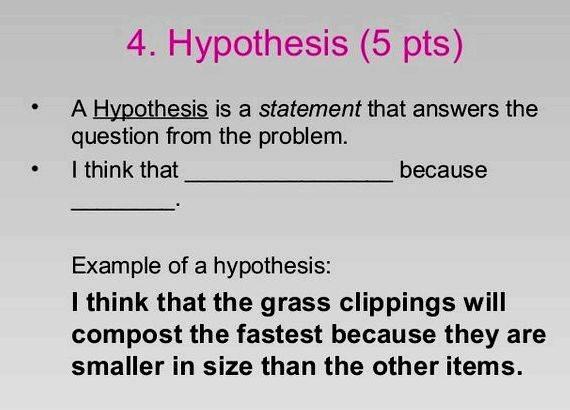

After gathering background research, the next step is to formulate a hypothesis. More than a random guess, a hypothesis is a testable statement based on background knowledge, research, or scientific reason. A hypothesis states the anticipated cause and effect that may be observed during the investigation.

Consider the following hypothesis: If ice is placed in a Styrofoam container, it will take longer to melt than if placed in a plastic or glass container. I think this is true because my research shows that a lot of people purchase Styrofoam coolers to keep drinks cool.

The time it takes for ice to melt (dependent variable) depends on the type of container used (independent variable.). A hypothesis shows the relationship among variables in the investigation and often (but not always) uses the words if and then.

Design Experiment

Once a hypothesis has been formulated, it is time to design a procedure to test it. A well-designed investigation contains procedures that take into account all of the factors that could impact the results of the investigation. These factors are called variables.

There are three types of variables to consider when designing the investigation procedure.

- The independent variable is the one variable the investigator chooses to change.

- Controlled variables are variables that are kept the same each time.

- The dependent variable is the variable that changes as a result of /or in response to the independent variable.

Step A – Clarify Variable

Clarify the variables involved in the investigation by developing a table such as the one below.

Step B – List Materials Make a list of materials that will be used in the investigation.

Step C – List Steps List the steps needed to carry out the investigation.

Step D – Estimate Time Estimate the time it will take to complete the investigation. Will the data be gathered in one sitting or over the course of several weeks?

Step E – Check Work Check the work. Ask someone else to read the procedure to make sure the steps are clear. Are there any steps missing? Double check the materials list to be sure all to the necessary materials are included.

Data Collection

After designing the experiment and gathering the materials, it is time to set up and to carry out the investigation.

When setting up the investigation, consider...

Carrying out the investigation involves data collection. There are two types of data that may be collected—quantitative data and qualitative data.

Quantitative Data

- Uses numbers to describe the amount of something.

- Involves tools such as rulers, timers, graduated cylinders, etc.

- Uses standard metric units (For instance, meters and centimeters for length, grams for mass, and degrees Celsius for volume.

- May involve the use of a scale such as in the example below.

Qualitative Data

- Uses words to describe the data.

- Describes physical properties such as how something looks, feels, smells, tastes, or sounds.

As data is collected it can be organized into lists and tables. Organizing data will be helpful for identifying relationships later when making an analysis. Using technology, such as spreadsheets, to organize the data can make it easily accessible to add to and edit.

Analyze Data

After data has been collected, the next step is to analyze it. The goal of data analysis is to determine if there is a relationship between the independent and dependent variables. In student terms, this is called “looking for patterns in the data.” Did the change I made have an effect that can be measured?

Recording data on a table or chart makes it much easier to observe relationships and trends. There are many observations that can be made when looking at a data table. Comparing mean average or median numbers of objects, observing trends of increasing or decreasing numbers, comparing modes or numbers of items that occur most frequently are just a few examples of quantitative analysis.

Besides analyzing data on tables or charts, graphs can be used to make a picture of the data. Graphing the data can often help make those relationships and trends easier to see. Graphs are called “pictures of data.” The important thing is that appropriate graphs are selected for the type of data. For example, bar graphs, pictographs, or circle graphs should be used to represent categorical data (sometimes called “side by side” data). Line plots are used to show numerical data. Line graphs should be used to show how data changes over time. Graphs can be drawn by hand using graph paper or generated on the computer from spreadsheets for students who are technically able.

These questions can help with analyzing data:

- What can be learned from looking at the data?

- How does the data relate to the student’s original hypothesis?

- Did what you changed (independent variable) cause changes in the results (dependent variable)?

Draw Conclusions

After analyzing the data, the next step is to draw conclusions. Do not change the hypothesis if it does not match the findings.The accuracy of a hypothesis is NOT what constitutes a successful science fair investigation. Rather, Science Fair judges will want to see that the conclusions stated match the data that was collected.

Application of the Results: Students may want to include an application as part of their conclusion. For example, after investigating the effectiveness of different stain removers, a student might conclude that vinegar is just as effective at removing stains as are some commercial stain removers. As a result, the student might recommend that people use vinegar as a stain remover since it may be the more eco-friendly product.

In short, conclusions are written to answer the original testable question proposed at the beginning of the investigation. They also explain how the student used science process to develop an accurate answer.

Kids Workshops

To learn more visit, homedepot.com/kids

Kids Workshops provide a mix of skill-building, creativity, and safety for future DIYers every month in Home Depot stores across the country. After registering for the next Workshop, download these exclusive extension activities from Discovery Education. Each extension provides opportunities to reimagine or use their Workshop creation in an unexpected new way.

Grill Gift Card Box

Blooming Picture Frame

Use nature as inspiration for creative writing. Students will research a variety of flowers to create a poem for their Blooming Picture Frame.

Lattice Planter

Explore the features of plants and consider how they impact our world. Students will select the type of plant they want to grow and map out a watering schedule to ensure it thrives in their Lattice Planter

Steps in a Science Fair Project

What are the steps in a science fair project.

- Pick a topic

- Construct an exhibit for results

- Write a report

- Practice presenting

Some science fair projects are experiments to test a hypothesis . Other science fair projects attempt to answer a question or demonstrate how nature works or even invent a technology to measure something.

Before you start, find out which of these are acceptable kinds of science fair projects at your school. You can learn something and have fun using any of these approaches.

- First, pick a topic. Pick something you are interested in, something you'd like to think about and know more about.

- Then do some background research on the topic.

- Decide whether you can state a hypothesis related to the topic (that is, a cause and effect statement that you can test), and follow the strict method listed above, or whether you will just observe something, take and record measurements, and report.

- Design and carry out your research, keeping careful records of everything you do or see and your results or observations.

- Construct an exhibit or display to show and explain to others what you hoped to test (if you had a hypothesis) or what question you wanted to answer, what you did, what your data showed, and your conclusions.

- Write a short report that also states the same things as the exhibit or display, and also gives the sources of your initial background research.

- Practice describing your project and results, so you will be ready for visitors to your exhibit at the science fair.

Do a Science Fair Project!

How do you do a science fair project.

Ask a parent, teacher, or other adult to help you research the topic and find out how to do a science fair project about it.

Test, answer, or show?

Your science fair project may do one of three things:

Test an idea (or hypothesis.)

Answer a question.

Show how nature works.

Topic ideas:

Space topics:.

How do the constellations change in the night sky over different periods of time?

How does the number of stars visible in the sky change from place to place because of light pollution?

Learn about and demonstrate the ancient method of parallax to measure the distance to an object, such as stars and planets.

Study different types of stars and explain different ways they end their life cycles.

Earth topics:

How do the phases of the Moon correspond to the changing tides?

Demonstrate what causes the phases of the Moon?

How does the tilt of Earth’s axis create seasons throughout the year?

How do weather conditions (temperature, humidity) affect how fast a puddle evaporates?

How salty is the ocean?

Solar system topics:

How does the size of a meteorite relate to the size of the crater it makes when it hits Earth?

How does the phase of the Moon affect the number of stars visible in the sky?

Show how a planet’s distance from the Sun affects its temperature.

Sun topics:

Observe and record changes in the number and placement of sun spots over several days. DO NOT look directly at the Sun!

Make a sundial and explain how it works.

Show why the Moon and the Sun appear to be the same size in the sky.

How effective are automobile sunshades?

Study and explain the life space of the sun relative to other stars.

Pick a topic.

Try to find out what people already know about it.

State a hypothesis related to the topic. That is, make a cause-and-effect-statement that you can test using the scientific method .

Explain something.

Make a plan to observe something.

Design and carry out your research, keeping careful records of everything you do or see.

Create an exhibit or display to show and explain to others what you hoped to test (if you had a hypothesis) or what question you wanted to answer, what you did, what your data showed, and your conclusions.

Write a short report that also states the same things as the exhibit or display, and also gives the sources of your initial background research.

Practice describing your project and results, so you will be ready for visitors to your exhibit at the science fair.

Follow these steps to a successful science fair entry!

If you liked this, you may like:

How to Do a Science Fair Project

Design a Project & Collect Data

- Projects & Experiments

- Chemical Laws

- Periodic Table

- Scientific Method

- Biochemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Medical Chemistry

- Chemistry In Everyday Life

- Famous Chemists

- Activities for Kids

- Abbreviations & Acronyms

- Weather & Climate

- Ph.D., Biomedical Sciences, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

- B.A., Physics and Mathematics, Hastings College

Okay, you have a subject and you have at least one testable question. If you haven't done so already, make sure you understand the steps of the scientific method . Try to write down your question in the form of a hypothesis. Let's say your initial question is about determining the concentration required for salt to be tasted in water. Really, in the scientific method, this research would fall under the category of making observations. Once you had some data, you could go on to formulate a hypothesis, such as: "There will be no difference between the concentration at which all members of my family will detect salt in water." For elementary school science fair projects and possibly high school projects , the initial research may be an excellent project in itself. However, the project will be much more meaningful if you can form a hypothesis, test it, and then determine whether or not the hypothesis was supported.

Write Down Everything

Whether you decide on a project with a formal hypothesis or not, when you perform your project (take data), there are steps you can take to make the most of your project. First, write everything down. Gather your materials and list them, as specifically as you can. In the scientific world, it is important to be able to duplicate an experiment, especially if surprising results are obtained. In addition to writing down data, you should note any factors that could affect your project. In the salt example, it is possible that the temperature could affect my results (alter the solubility of salt, change the body's rate of excretion, and other factors I might not consciously consider). Other factors you might note could include relative humidity, the age of participants in my study, a list of medications (if anyone is taking them), etc. Basically, write down anything of note or potential interest. This information could lead your study in new directions once you start taking data. The information you take down at this point could make a fascinating summary or discussion of future research directions for your paper or presentation.

Don't Discard Data

Perform your project and record your data. When you form a hypothesis or seek the answer to a question, you probably have a preconceived idea of the answer. Don't let this preconception influence the data you record! If you see a data point that looks 'off', don't throw it out, no matter how strong the temptation. If you are aware of some unusual event that occurred when the data was being taken, feel free to make a note of it, but don't discard the data.

Repeat the Experiment

To determine the level at which you taste salt in water , you can keep adding salt to water until you have a detectable level, record the value, and move on. However, that single data point will have very little scientific significance. It is necessary to repeat the experiment, perhaps several times, to achieve significant value. Keep notes on the conditions surrounding a duplication of an experiment. If you duplicate the salt experiment, perhaps you would get different results if you kept tasting salt solutions over and over than if you performed the test once a day over a span of several days. If your data takes the form of a survey, multiple data points might consist of many responses to the survey. If the same survey is resubmitted to the same group of people in a short time span, would their answers change? Would it matter if the same survey was given to a different, yet seemingly, a similar group of people? Think about questions like this and take care in repeating a project.

- How to Write a Science Fair Project Report

- How To Design a Science Fair Experiment

- How to Organize Your Science Fair Poster

- Chemistry Science Fair Project Ideas

- How to Select a Science Fair Project Topic

- Make a Science Fair Poster or Display

- Science Projects for Every Subject

- 5 Types of Science Fair Projects

- 6th Grade Science Fair Projects

- Biology Science Fair Project Ideas

- Six Steps of the Scientific Method

- Middle School Science Fair Project Ideas

- Science Lab Report Template - Fill in the Blanks

- High School Science Fair Projects

- 4th Grade Science Fair Projects

- 7th Grade Science Fair Projects

What is a hypothesis?

No. A hypothesis is sometimes described as an educated guess. That's not the same thing as a guess and not really a good description of a hypothesis either. Let's try working through an example.

If you put an ice cube on a plate and place it on the table, what will happen? A very young child might guess that it will still be there in a couple of hours. Most people would agree with the hypothesis that:

An ice cube will melt in less than 30 minutes.

You could put sit and watch the ice cube melt and think you've proved a hypothesis. But you will have missed some important steps.

For a good science fair project you need to do quite a bit of research before any experimenting. Start by finding some information about how and why water melts. You could read a book, do a bit of Google searching, or even ask an expert. For our example, you could learn about how temperature and air pressure can change the state of water. Don't forget that elevation above sea level changes air pressure too.

Now, using all your research, try to restate that hypothesis.

An ice cube will melt in less than 30 minutes in a room at sea level with a temperature of 20C or 68F.

But wait a minute. What is the ice made from? What if the ice cube was made from salt water, or you sprinkled salt on a regular ice cube? Time for some more research. Would adding salt make a difference? Turns out it does. Would other chemicals change the melting time?

Using this new information, let's try that hypothesis again.

An ice cube made with tap water will melt in less than 30 minutes in a room at sea level with a temperature of 20C or 68F.

Does that seem like an educated guess? No, it sounds like you are stating the obvious.

At this point, it is obvious only because of your research. You haven't actually done the experiment. Now it's time to run the experiment to support the hypothesis.

A hypothesis isn't an educated guess. It is a tentative explanation for an observation, phenomenon, or scientific problem that can be tested by further investigation.

Once you do the experiment and find out if it supports the hypothesis, it becomes part of scientific theory.

Notes to Parents:

- Every parent must use their own judgment in choosing which activities are safe for their own children. While Science Kids at Home makes every effort to provide activity ideas that are safe and fun for children it is your responsibility to choose the activities that are safe in your own home.

- Science Kids at Home has checked the external web links on this page that we created. We believe these links provide interesting information that is appropriate for kids. However, the internet is a constantly changing place and these links may not work or the external web site may have changed. We also have no control over the "Ads by Google" links, but these should be related to kids science and crafts. You are responsible for supervising your own children. If you ever find a link that you feel is inappropriate, please let us know.

Kids Science Gifts Science Experiments Science Fair Projects Science Topics Creative Kids Blog

Kids Crafts Privacy Policy Copyright © 2016 Science Kids at Home, all rights reserved.

- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

Hypothesis Examples

A hypothesis is a prediction of the outcome of a test. It forms the basis for designing an experiment in the scientific method . A good hypothesis is testable, meaning it makes a prediction you can check with observation or experimentation. Here are different hypothesis examples.

Null Hypothesis Examples

The null hypothesis (H 0 ) is also known as the zero-difference or no-difference hypothesis. It predicts that changing one variable ( independent variable ) will have no effect on the variable being measured ( dependent variable ). Here are null hypothesis examples:

- Plant growth is unaffected by temperature.

- If you increase temperature, then solubility of salt will increase.

- Incidence of skin cancer is unrelated to ultraviolet light exposure.

- All brands of light bulb last equally long.

- Cats have no preference for the color of cat food.

- All daisies have the same number of petals.

Sometimes the null hypothesis shows there is a suspected correlation between two variables. For example, if you think plant growth is affected by temperature, you state the null hypothesis: “Plant growth is not affected by temperature.” Why do you do this, rather than say “If you change temperature, plant growth will be affected”? The answer is because it’s easier applying a statistical test that shows, with a high level of confidence, a null hypothesis is correct or incorrect.

Research Hypothesis Examples

A research hypothesis (H 1 ) is a type of hypothesis used to design an experiment. This type of hypothesis is often written as an if-then statement because it’s easy identifying the independent and dependent variables and seeing how one affects the other. If-then statements explore cause and effect. In other cases, the hypothesis shows a correlation between two variables. Here are some research hypothesis examples:

- If you leave the lights on, then it takes longer for people to fall asleep.

- If you refrigerate apples, they last longer before going bad.

- If you keep the curtains closed, then you need less electricity to heat or cool the house (the electric bill is lower).

- If you leave a bucket of water uncovered, then it evaporates more quickly.

- Goldfish lose their color if they are not exposed to light.

- Workers who take vacations are more productive than those who never take time off.

Is It Okay to Disprove a Hypothesis?

Yes! You may even choose to write your hypothesis in such a way that it can be disproved because it’s easier to prove a statement is wrong than to prove it is right. In other cases, if your prediction is incorrect, that doesn’t mean the science is bad. Revising a hypothesis is common. It demonstrates you learned something you did not know before you conducted the experiment.

Test yourself with a Scientific Method Quiz .

- Mellenbergh, G.J. (2008). Chapter 8: Research designs: Testing of research hypotheses. In H.J. Adèr & G.J. Mellenbergh (eds.), Advising on Research Methods: A Consultant’s Companion . Huizen, The Netherlands: Johannes van Kessel Publishing.

- Popper, Karl R. (1959). The Logic of Scientific Discovery . Hutchinson & Co. ISBN 3-1614-8410-X.

- Schick, Theodore; Vaughn, Lewis (2002). How to think about weird things: critical thinking for a New Age . Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 0-7674-2048-9.

- Tobi, Hilde; Kampen, Jarl K. (2018). “Research design: the methodology for interdisciplinary research framework”. Quality & Quantity . 52 (3): 1209–1225. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0513-8

Related Posts

Learn STEM by Doing (and having fun)!

The Ultimate Science Fair Project Guide – From Start to Finish

When our daughter entered her first science fair, we kept seeing references to the Internet Public Library Science Fair Project Resource Guide . However, the IPL2 permanently closed… taking the guide with it. Bummer ! After now participating in over a half-dozen elementary school science fairs (including a first-place finish!), we created our own guide to help other students go from start to finish in their next science fair project. If this is your first science fair, have fun! If you’ve done it before, we hope this is your best one! Let’s science!

*Images from Unsplash

How to Use the STEMium Science Fair Project Ultimate Guide?

If you are just starting off and this is your first science fair, here’s how to get started:

- Start with the STEMium Science Fair Project Roadmap . This is an infographic that “maps” out the process from start to finish and shows all the steps in a visual format.

- Getting Started – Why Do a Science Fair Project . Besides walking through some reasons to do a project, we also share links to examples of national science fair competitions, what’s involved and examples of winning science fair experiments . *Note: this is where you’ll get excited!!

- The Scientific Method – What is It and What’s Involved . One of the great things about a science fair project is that it introduces students to an essential process/concept known as the scientific method. This is simply the way in which we develop a hypothesis to test.

- Start the Process – Find an Idea . You now have a general idea of what to expect at the science fair, examples of winning ideas, and know about the scientific method. You’re ready to get started on your own project. How do you come up with an idea for a science fair project? We have resources on how to use a Google tool , as well as some other strategies for finding an idea.

- Experiment and Build the Project . Time to roll up those sleeves and put on your lab coat.

- Other Resources for the Fair. Along the way, you will likely encounter challenges or get stuck. Don’t give up – it’s all part of the scientific process. Check out our STEMium Resources page for more links and resources from the web. We also have additional experiments like the germiest spot in school , or the alka-seltzer rocket project that our own kids used.

Getting Started – Why Do a Science Fair Project

For many students, participating in the science fair might be a choice that was made FOR you. In other words, something you must do as part of a class. Maybe your parents are making you do it. For others, maybe it sounded like a cool idea. Something fun to try. Whatever your motivation, there are a lot of great reasons to do a science fair project.

- Challenge yourself

- Learn more about science

- Explore cool technology

- Make something to help the world! (seriously!)

- Win prizes (and sometimes even money)

- Do something you can be proud of!

Many students will participate in a science fair at their school. But there are also national competitions that include 1000s of participants. There are also engineering fairs, maker events, and hackathons. It’s an exciting time to be a scientist!! The list below gives examples of national events.

- Regeneron Science Talent Search

- Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair

- Google Science Fair

- Conrad Challenge

- Microsoft Imagine Cup

- JSHS Program

- Exploravision

What’s the Scientific Method?

Before we jump into your project, it’s important to introduce a key concept: The Scientific Method . The scientific method is the framework scientists use to answer their questions and test their hypothesis. The figure below illustrates the steps you’ll take to get to the end, but it starts with asking a question (you’ve already finished the first step!).

After we find a problem/idea to tackle, and dig into some background research, we create a guess on a potential solution. This is known as our hypothesis.

Example of a Hypothesis

My brother can hold his breath underwater longer than I can (“our problem”) –> how can I hold my breath longer? (“our question”) –> if I drink soda with caffeine before I hold my breath, I will be able to stay underwater longer (“our solution”). Our hypothesis is that using caffeine before we go underwater will increase the time we hold our breath. We’re not sure if that is a correct solution or not at this stage – just taking a guess.

Once we have a hypothesis, we design an experiment to TEST our hypothesis. First, we will change variables/conditions one at a time while keeping everything else the same, so we can compare the outcomes.

Experimental Design Example

Using our underwater example, maybe we will test different drinks and count how long I can hold my breath. Maybe we can also see if someone else can serve as a “control” – someone who holds their breath but does not drink caffeine. For the underwater experiment, we can time in seconds how long I hold my breath before I have a drink and then time it again after I have my caffeine drink. I can also time how long I stay underwater when I have a drink without caffeine.

Then, once we finish with our experiment, we analyze our data and develop a conclusion.

- How many seconds did I stay underwater in the different situations?

- Which outcome is greater? Did caffeine help me hold my breath longer?

Finally, (and most important), we present our findings. Imagine putting together a poster board with a chart showing the number of seconds I stayed underwater in the different conditions.

Hopefully you have a better sense of the scientific method. If you are completing a science fair project, sticking with these steps is super important. Just in case there is any lingering confusion, here are some resources for learning more about the scientific method:

- Science Buddies – Steps of the Scientific Method

- Ducksters – Learn About the Scientific Method

- Biology4kids – Scientific Method

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences – Scientific Method

What Science Fair Project Should I Do?

And science is no different.

Just know that if you can get through the idea part, the rest of the science fair is relatively smooth sailing. Remember to keep an open mind and a positive outlook . Each year 100s of 1000s of kids, teenagers and college students come up with new projects and ideas to test. You’ve got this!

What Makes a Great Science Fair Project? Start with a Problem To Solve

As we discuss below, good science experiments attempt to answer a QUESTION. Why is the sky blue? Why does my dog bark at her reflection? First, we will step through some ways to find TESTABLE QUESTIONS. These questions that you create will be what you work on for your science fair project. Pick something fun, something interesting and something that you are excited about. Not sure what that looks like? Step through some of the tips below for help.

Use the Google Science Fair Idea Generator

Are you surprised Google made a tool for science fair projects?? Our post called the low-stress way to find a science fair project gives a more in-depth overview about how to use it. It’s a great first stop if you’re early in the brainstorming process.

Answer your own questions

- What type of music makes you run faster?

- Can boys hold their breath underwater longer than girls?

- How can I be sure the sandwich I bought is gluten free?

- If we plant 100 trees in our neighborhood, will the air be cleaner?

Still stuck? Get inspiration from other science fair projects

Check out the Getting Started section and look at some of the winning science project ideas, our STEMium experiments and our Resource page. We’ve presented a ton of potential idea starters for you – take time to run through some of these, but our suggestion is to give yourself a deadline to pick an idea . Going through the lists could take you longer than you think, and in many cases sometimes it’s just better to pick something and go for it! The next section will take you through how to create testable questions for your project.

Starting Your Project: Find A Testable Question

The best experiments start with a question. Taking that a step further, the questions you useyou’re your science fair project should be ones that are TESTABLE. That means something you can measure. Let’s look at an example. Let’s say I’m super excited about baking. OH YEA!! I love baking. Specifically, baking cakes. In fact, I love baking cakes so much that I want to do a science project related to cakes. We’ve got two questions on cakes that we created. Which question below could be most useful for a science fair project:

1) Can eating cake before a test improve your score?

2) Why isn’t carrot cake more popular than chocolate cake?

The second question isn’t necessarily a bad question to pick. You could survey people and perhaps tackle the question that way. However, chances are you will get a lot of different answers and it will probably take a lot of surveys to start to pick up a trend.

Although, the first question might be a little easier. How would you test this? Maybe you pick one type of cake and one test that you give people. If you can get five people to take the test after eating cake and five people take the test with no cake, you can compare the test results. There might be other variables beyond cake that you could test (example: age, sex, education). But you can see that the first question is probably a little easier to test. The first question is also a little easier to come up with a hypothesis.

At this point, you’ve got an idea. That was the hard part! Now it’s time to think a little more about that idea and focus it into a scientific question that is testable and that you can create a hypothesis around .

What makes a question “testable”?

Testable questions are ones that can be measured and should focus on what you will change. In our first cake question, we would be changing whether or not people eat cake before a test. If we are giving them all the same test and in the same conditions, you could compare how they do on the test with and without cake. As you are creating your testable question, think about what you WILL CHANGE (cake) and what you are expecting to be different (test scores). Cause and effect. Check out this reference on testable questions for more details.

Outline Your Science Project – What Steps Should I Take?

Do Background Research / Create Hypothesis

Science experiments typically start with a question (example: Which cleaning solution eliminates more germs?). The questions might come up because of a problem. For example, maybe you’re an engineer and you are trying to design a new line of cars that can drive at least 50 mph faster. Your problem is that the car isn’t fast enough. After looking at what other people have tried to do to get the car to go faster, and thinking about what you can change, you try to find a solution or an answer. When we talk about the scientific method, the proposed answer is referred to as the HYPOTHESIS.

- Science Buddies

- National Geographic

The information you gather to answer these research questions can be used in your report or in your board. This will go in the BACKGROUND section. For resources that you find useful, make sure you note the web address where you found it, and save in a Google Doc for later.

Additional Research Tips

For your own science fair project, there will likely be rules that will already be set by the judges/teachers/school. Make sure you get familiar with the rules FOR YOUR FAIR and what needs to be completed to participate . Typically, you will have to do some research into your project, you’ll complete experiments, analyze data, make conclusions and then present the work in a written report and on a poster board. Make a checklist of all these “to do” items. Key things to address:

- Question being answered – this is your testable question

- Hypothesis – what did you come up with and why

- Experimental design – how are you going to test your hypothesis

- Conclusions – why did you reach these and what are some alternative explanations

- What would you do next? Answering a testable question usually leads to asking more questions and judges will be interested in how you think about next steps.

Need more help? Check out these additional resources on how to tackle a science fair project:

- Developing a Science Fair Project – Wiley

- Successful Science Fair Projects – Washington University

- Science Fair Planning Guide – Chattahoochee Elementary

Experiment – Time to Test That Hypothesis

Way to go! You’ve found a problem and identified a testable question. You’ve done background research and even created a hypothesis. It’s time to put it all together now and start designing your experiment. Two experiments we have outlined in detail – germiest spot in school and alka-seltzer rockets – help show how to set up experiments to test variable changes.

The folks at ThoughtCo have a great overview on the different types of variables – independent, dependent and controls. You need to identify which ones are relevant to your own experiment and then test to see how changes in the independent variable impacts the dependent variable . Sounds hard? Nope. Let’s look at an example. Let’s say our hypothesis is that cold weather will let you flip a coin with more heads than tails. The independent variable is the temperature. The dependent variable is the number of heads or tails that show up. Our experiment could involve flipping a coin fifty times in different temperatures (outside, in a sauna, in room temperature) and seeing how many heads/tails we get.

One other important point – write down all the steps you take and the materials you use!! This will be in your final report and project board. Example – for our coin flipping experiment, we will have a coin (or more than one), a thermometer to keep track of the temperature in our environment. Take pictures of the flipping too!

Analyze Results – Make Conclusions

Analyzing means adding up our results and putting them into pretty pictures. Use charts and graphs whenever you can. In our last coin flipping example, you’d want to include bar charts of the number of heads and tails at different temperatures. If you’re doing some other type of experiment, take pictures during the different steps to document everything.

This is the fun part…. Now we get to see if we answered our question! Did the weather affect the coin flipping? Did eating cake help us do better on our test?? So exciting! Look through what the data tells you and try to answer your question. Your hypothesis may / may not be correct. It’s not important either way – the most important part is what you learned and the process. Check out these references for more help:

- How to make a chart or graph in Google Sheets

- How to make a chart in Excel

Presentation Time – Set Up Your Board, Practice Your Talk

Personally, the presentation is my favorite part! First, you get to show off all your hard work and look back at everything you did! Additionally, science fair rules should outline the specific sections that need to be in the report, and in the poster board – so, be like Emmett from Lego Movie and read the instructions. Here’s a loose overview of what you should include:

- Title – what is it called.

- Introduction / background – here’s why you’re doing it and helping the judges learn a bit about your project.

- Materials/Methods – what you used and the steps in your experiment. This is so someone else could repeat your experiment.

- Results – what was the outcome? How many heads/tails? Include pictures and graphs.

- Conclusions – was your hypothesis correct? What else would you like to investigate now? What went right and what went wrong?

- References – if you did research, where did you get your information from? What are your sources?

The written report will be very similar to the final presentation board. The board that you’ll prepare is usually a three-panel board set up like the picture shown below.

To prepare for the presentation, you and your partner should be able to talk about the following:

- why you did the experiment

- the hypothesis that was tested

- the data results

- the conclusions.

It’s totally OK to not know an answer. Just remember this is the fun part!

And that’s it! YOU DID IT!!

Science fair projects have been great opportunities for our kids to not only learn more about science, but to also be challenged and push themselves. Independent projects like these are usually a great learning opportunity. Has your child completed a science fair project that they are proud of? Include a pic in the comments – we love to share science!! Please also check out our STEMium Resources page for more science fair project tips and tricks .

STEMomma is a mother & former scientist/educator. She loves to find creative, fun ways to help engage kids in the STEM fields (science, technology, engineering and math). When she’s not busy in meetings or carpooling kids, she loves spending time with the family and dreaming up new experiments or games they can try in the backyard.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

- +254-729-010-973

- [email protected]

Notice: Get Professional Academic Writing

Homework Help

Premier write my essay and Homework help service

Writing a hypothesis for science fair projects

What is a Hypothesis?

A hypothesis is a tentative, testable answer to a scientific question. Once a scientist has a scientific question she is interested in, the scientist reads up to find out what is already known on the topic. Then she uses that information to form a tentative answer to her scientific question. Sometimes people refer to the tentative answer as “an educated guess.” Keep in mind, though, that the hypothesis also has to be testable since the next step is to do an experiment to determine whether or not the hypothesis is right!

A hypothesis leads to one or more predictions that can be tested by experimenting.

Predictions often take the shape of “If ____then ____” statements, but do not have to. Predictions should include both an independent variable (the factor you change in an experiment) and a dependent variable (the factor you observe or measure in an experiment). A single hypothesis can lead to multiple predictions, but generally, one or two predictions is enough to tackle for a science fair project.

Examples of Hypotheses and Predictions

How does the size of a dog affect how much food it eats?

Larger animals of the same species expend more energy than smaller animals of the same type. To get the energy their bodies need, the larger animals eat more food.

If I let a 70-pound dog and a 30-pound dog eat as much food as they want, then the 70-pound dog will eat more than the 30-pound dog.

Does fertilizer make a plant grow bigger?

Plants need many types of nutrients to grow. Fertilizer adds those nutrients to the soil, thus allowing plants to grow more.

If I add fertilizer to the soil of some tomato seedlings, but not others, then the seedlings that got fertilizer will grow taller and have more leaves than the non-fertilized ones.

Does an electric motor turn faster if you increase the current?

Electric motors work because they have electromagnets inside them, which push/pull on permanent magnets and make the motor spin. As more current flows through the motor’s electromagnet, the strength of the magnetic field increases, thus turning the motor faster.

If I increase the current supplied to an electric motor, then the RPMs (revolutions per minute) of the motor will increase.

Is a classroom noisier when the teacher leaves the room?

Teachers have rules about when to talk in the classroom. If they leave the classroom, the students feel free to break the rules and talk more, making the room nosier.

If I measure the noise level in a classroom when a teacher is in it and when she leaves the room, then I will see that the noise level is higher when my teacher is not in my classroom.

What if My Hypothesis is Wrong?

What happens if, at the end of your science project, you look at the data you have collected and you realize it does not support your hypothesis? First, do not panic! The point of a science project is not to prove your hypothesis right. The point is to understand more about how the natural world works. Or, as it is sometimes put, to find out the scientific truth. When scientists do an experiment, they very often have data that shows their starting hypothesis was wrong. Why? Well, the natural world is complexit takes a lot of experimenting to figure out how it worksand the more explanations you test, the closer you get to figuring out the truth.

For scientists, disproving a hypothesis still means they gained important information, and they can use that information to make their next hypothesis even better. In a science fair setting, judges can be just as impressed by projects that start out with a faulty hypothesis; what matters more is whether you understood your science fair project, had a well-controlled experiment, and have ideas about what you would do next to improve your project if you had more time. You can read more about a science fair judge’s view on disproving your hypothesis here.

It is worth noting, scientists never talk about their hypothesis being “right” or “wrong.” Instead, they say that their data “supports” or “does not support” their hypothesis. This goes back to the point that nature is complexso complex that it takes more than a single experiment to figure it all out because a single experiment could give you misleading data. For example, let us say that you hypothesize that earthworms do not exist in places that have very cold winters because it is too cold for them to survive. You then predict that you will find earthworms in the dirt in Florida, which has warm winters, but not Alaska, which has cold winters. When you go and dig a 3-foot by 3-foot-wide and 1-foot-deep hole in the dirt in those two states, you discover Floridian earthworms, but not Alaskan ones. So, was your hypothesis right? Well, your data “supported” your hypothesis, but your experiment did not cover that much ground. Can you really be sure there are no earthworms in Alaska? No. Which is why scientists only support (or not) their hypothesis with data, rather than proving them. And for the curious, yes there are earthworms in Alaska.

Hypothesis Checklist

What Makes a Good Hypothesis?

By Anne Marie Helmenstine, Ph.D. Chemistry Expert

Anne Helmenstine, Ph.D. is an author and consultant with a broad scientific and medical background. Read more

Writing a science fair project report may seem like a challenging task, but it is not as difficult as it first appears. This is a format that you may use to write a science project report. If your project included animals, humans, hazardous materials, or regulated substances, you can attach an appendix that describes any special activities your project required. Also, some reports may benefit from additional sections, such as abstracts and bibliographies.

Continue Reading Below

You may find it helpful to fill out the science fair lab report template to prepare your report.

Important: Some science fairs have guidelines put forth by the science fair committee or an instructor. If your science fair has these guidelines, be sure to follow them.

- Title For a science fair, you probably want a catchy, clever title. Otherwise, try to make it an accurate description of the project. For example, I could entitle a project, ’;Determining Minimum NaCl Concentration that can be Tasted in Water’;. Avoid unnecessary words, while covering the essential purpose of the project. Whatever title you come up with, get it critiqued by friends, family, or teachers.

- Introduction and Purpose Sometimes this section is called ’;Background’;. Whatever its name, this section introduces the topic of the project, notes any information already available, explains why you are interested in the project, and states the purpose of the project. If you are going to state references in your report, this is where most of the citations are likely to be, with the actual references listed at the end of the entire report in the form of a bibliography or reference section.

- Materials and Methods List the materials you used in your project and describe the procedure that you used to perform the project. If you have a photo or diagram of your project, this is a good place to include it.

- Data and Results Data and Results are not the same thing. Some reports will require that they be in separate sections, so make sure you understand the difference between the concepts. Data refers to the actual numbers or other information you obtained in your project. Data can be presented in tables or charts, if appropriate. The Results section is where the data is manipulated or the hypothesis is tested. Sometimes this analysis will yield tables, graphs, or charts, too. For example, a table listing the minimum concentration of salt that I can taste in water, with each line in the table being a separate test or trial, would be data. If I average the data or perform a statistical test of a null hypothesis. the information would be the results of the project.

- Conclusion The Conclusion focuses on the Hypothesis or Question as it compares to the Data and Results. What was the answer to the question? Was the hypothesis supported (keep in mind a hypothesis cannot be proved, only disproved)? What did you find out from the experiment? Answer these questions first. Then, depending on your answers, you may wish to explain ways in which the project might be improved or introduce new questions that have come up as a result of the project. This section is judged not only by what you were able to conclude, but also by your recognition of areas where you could not draw valid conclusions based on your data.

Appearances Matter Neatness counts, spelling counts, grammar counts. Take the time to make the report look nice. Pay attention to margins, avoid fonts that are difficult to read or are too small or too large, use clean paper, and make print the report cleanly on as good a printer or copier as you can.

COMMENTS

A hypothesis is a tentative, testable answer to a scientific question. Once a scientist has a scientific question she is interested in, the scientist reads up to find out what is already known on the topic. Then she uses that information to form a tentative answer to her scientific question. Sometimes people refer to the tentative answer as "an ...

The goal of a science project is not to prove your hypothesis right or wrong. The goal is to learn more about how the natural world works. Even in a science fair, judges can be impressed by a project that started with a bad hypothesis. What matters is that you understood your project, did a good experiment, and have ideas for how to make it better.

Developing a hypothesis (with example) Step 1. Ask a question. Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project. Example: Research question.

Step 5C: Draft your hypothesis. Your draft hypothesis statement should include the following: the question or problem you are trying to answer; how the independent variable will be changed; the measurable or testable effect it will have on the dependent variable; and your best guess as to what you think the outcome will be.

Formulate a Hypothesis. Need help writing your hypothesis? Try using the hypothesis worksheet to help you. Scientists at Argonne National Laboratory can help you with your project. ( just ask) Step 3C: Research your process. Step 5: Design an experiment. The digital library project.

Scientific Projects. Students who want to find out things as a scientist, will want to conduct a hands-on investigation. While scientists study a whole area of science, each investigation is focused on learning just one thing at a time. This is essential if the results are to be trusted by the entire science community.

Research. Hypothesis. Experiment. Construct an exhibit for results. Write a report. Practice presenting. Some science fair projects are experiments to test a hypothesis. Other science fair projects attempt to answer a question or demonstrate how nature works or even invent a technology to measure something. Before you start, find out which of ...

Before you start off your science fair experimentation or engineering project (whether you are in elementary, middle, or high school), you will most likely b...

The Science Fair: Close-up photo of a smart girl looking at the microscope. In the pursuit of scientific enquiry, data is our most valuable asset. It allows us to observe patterns, draw conclusions, and validate our hypotheses. To ensure our science fair projects are grounded in reliable evidence, we must be meticulous in gathering data.

Your science fair project may do one of three things: test an idea (hypothesis), answer a question, and/or show how nature works. Ask a parent, teacher, or other adult to help you research the topic and find out how to do a science fair project about it. ... Write a short report that also states the same things as the exhibit or display, and ...

How to Do a Science Fair Project. Design a Project & Collect Data. Okay, you have a subject and you have at least one testable question. If you haven't done so already, make sure you understand the steps of the scientific method. Try to write down your question in the form of a hypothesis. Let's say your initial question is about determining ...

An ice cube will melt in less than 30 minutes. You could put sit and watch the ice cube melt and think you've proved a hypothesis. But you will have missed some important steps. For a good science fair project you need to do quite a bit of research before any experimenting. Start by finding some information about how and why water melts.

Here are some research hypothesis examples: If you leave the lights on, then it takes longer for people to fall asleep. If you refrigerate apples, they last longer before going bad. If you keep the curtains closed, then you need less electricity to heat or cool the house (the electric bill is lower). If you leave a bucket of water uncovered ...

When our daughter entered her first science fair, we kept seeing references to the Internet Public Library Science Fair Project Resource Guide. However, the IPL2 permanently closed… taking the guide with it. Bummer! After now participating in over a half-dozen elementary school science fairs (including a first-place finish!), we created our ...

Week 6 in the Science Fair Friday series. This week we explain Hypothesis and Design Goal writing for students doing an experimental or engineering project.S...

A hypothesis leads to one or more predictions that can be tested by experimenting. Predictions often take the shape of "If ____then ____" statements, but do not have to. Predictions should include both an independent variable (the factor you change in an experiment) and a dependent variable (the factor you observe or measure in an experiment).

An abstract is an abbreviated version of your science fair project final report. For most science fairs, it is limited to a maximum of 250 words (check the rules for your competition). The science fair project abstract appears at the beginning of the report as well as on your display board. • Introduction.

The curse of hypothesis testing is that we will never know if we are dealing with a True or a False Positive (Negative). All we can do is fill the confusion matrix with probabilities that are acceptable given our application. To be able to do that, we must start from a hypothesis. Step 1. Defining the hypothesis