Parent Experiences of Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis: a Scoping Review

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 16 February 2021

- Volume 8 , pages 267–284, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Amber Makino ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2406-575X 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Laura Hartman 1 , 4 ,

- Gillian King 1 , 4 ,

- Pui Ying Wong 3 &

- Melanie Penner 1 , 2 , 3 , 5 , 6

15k Accesses

37 Citations

17 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The purpose of this review was to identify the quantity, breadth, and methodological characteristics of literature examining parent perspectives of autism spectrum disorder diagnosis, synthesize key research findings, and highlight gaps in the current literature. A systematic search was conducted for the period January 1994–February 2020. One hundred and twenty-two articles underwent data extraction. The majority of studies took place in Europe and North America in high-income countries. Over half of the studies used qualitative methodology. Four key components of the diagnostic experience were identified: journey to assessment, assessment process, delivery of the diagnosis and feedback session, and provision of information, resources, and support. Themes of parental emotions and parental satisfaction with the diagnostic process were also found.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Experiences of Late-diagnosed Women with Autism Spectrum Conditions: An Investigation of the Female Autism Phenotype

Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies

Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults with Autism: Third Generation Review

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

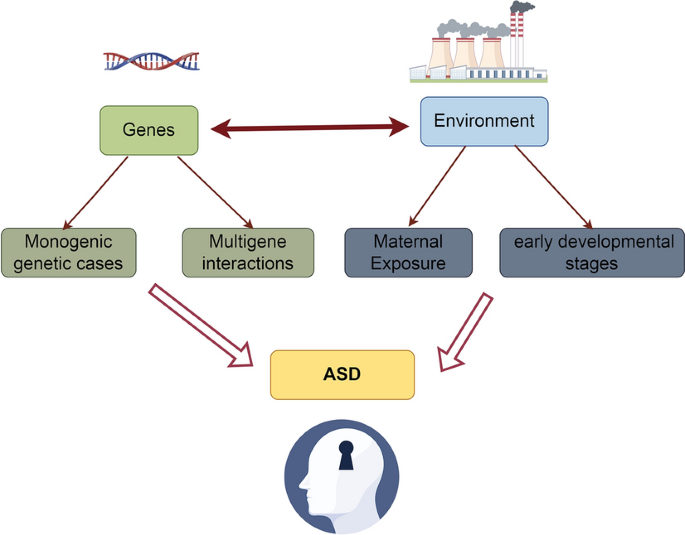

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder defined by impairment in social communication and the presence of restricted repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association 2013 ). ASD has steadily increased in reported prevalence over the past decade (Maenner et al. 2020 ), leading to growing pressure on professionals and systems to provide timely and accurate diagnosis. Aspects of diagnosing ASD have been shown to be challenging for professionals. Firstly, while numerous clinical diagnostic guidelines have been published (Brian et al. 2019 ; Filipek et al. 2000 ; Johnson et al. 2007 ; National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health 2011 ; Volkmar et al. 2014 ; Whitehouse et al. 2018 ), they vary in their recommendations for assessment and are of variable quality, especially in regard to applicability and rigor of development (Penner et al. 2018 ). This variability has led to inconsistent processes and practices across systems, with diagnostic pathways varying according to where a child lives. Delivering the diagnosis to families has also been shown to be challenging for professionals. In a recent large-scale United Kingdom (UK) survey of professionals providing ASD diagnoses, the three most challenging aspects of delivering an ASD diagnosis were reported to be (1) ensuring caregivers understood the diagnosis and why it was given; (2) communicating information that could be comprehended by the family; and (3) managing familial distress (Rogers et al. 2016 ). Professionals are also challenged by making ASD diagnoses and refer to the complexities of assessment, especially when evaluating phenotypic profiles that are seen as “atypical” (e.g., subtle cases, ASD in females) (Rogers et al. 2016 ). Similar themes were found in qualitative studies of physicians caring for children with ASD, which identified barriers to conducting ASD diagnostic assessments including inadequate training, challenges disclosing the diagnosis to families, and concerns about how to help families navigate resources in a fragmented system (Jacobs et al. 2018 ; Penner et al. 2017 ).

While it is important to understand professionals’ views of ASD diagnoses and processes, parents of children diagnosed with ASD are experts on their children and family needs. The goal of diagnostic assessment is not only to clarify the diagnosis but also to help the caregivers and child understand the diagnosis and direct the family to appropriate supports (Abbott et al. 2013 ; Zwaigenbaum and Penner 2018 ). Because families are the constant in the child’s life, they are considered best suited to determine their young child’s needs. Providing family-centered care that supports this approach is broadly considered best practice within the field of pediatrics, especially among children with chronic conditions (King et al. 2004 ). Family-centered care models have also been linked with increased parent satisfaction, decreased parent stress, and improved child outcomes (King et al. 2004 ; Woodside et al. 2001 ). Having a thorough understanding of clients’ and families’ ASD diagnostic experience is an important starting point for optimizing care for children with ASD and their families. Parent perceptions and expertise should therefore be understood and integrated into considerations of the appropriateness of existing diagnostic pathways. To date, reviews have mostly focused broadly on parent perspectives of raising a child with ASD (DePape and Lindsay 2016 ; Keok 2012 ) as opposed to the more specific time period around diagnosis. Recently, a systematic review and meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature about the ASD diagnostic experience for parents in the UK was performed (Legg and Tickle 2019 ). However, to our knowledge, no existing work has provided a systematic, in-depth, and international review of the existing evidence about parent or caregiver perceptions of the ASD diagnostic process.

The purpose of the current review is to (a) identify the quantity, breadth, and methodological characteristics of the current literature examining parent and caregivers’ perspectives of ASD diagnosis, (b) summarize and synthesize key research findings, and (c) highlight gaps and limitations in the current literature to direct future research.

We conducted a scoping review, which is a method of knowledge synthesis that aims to systematically and comprehensively examine a broad exploratory research question (Colquhoun et al. 2014 ). This methodology was chosen given the heterogeneous nature of the research on parent perspectives of ASD diagnosis and our aim for a comprehensive review. The current scoping review was performed following a protocol that was developed a priori and followed the 5-stage framework outlined by Arksey and O'Malley ( 2005 ) and further refined by the Joanna Briggs Institute (Peters et al. 2015 ).

Stage 1: Identify the Research Question

This scoping review addressed the following broad question: What is known about parent or caregiver perspectives of the ASD diagnostic experience?

Stage 2: Identify Relevant Studies

A systematic search of CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE (OVID), PsychINFO, and Scopus databases was conducted. These databases were selected for their relevance to the field concerned. We aimed to identify peer-reviewed articles published between January 1994 (when DSM IV criteria for autism were published) and February 2020 that were focused on the experiences of caregivers of children with ASD during the diagnostic process. A search strategy was developed in consultation with a hospital librarian (PW). All searches included at least one identifier for ASD (e.g., autism, Asperger) linked to at least one identifier for caregiver (e.g., parent), and diagnosis (e.g., assessment). Search terms were truncated when appropriate to maximize recall (see Table 1 for an example of our search strategy).

Stage 3: Select Studies

A systematic selection process was used to arrive at the final article set. After duplicate records were removed, the first author (AM) and principal investigator (MP) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts for relevance. At this stage, all articles identified by either author were included for full-text review. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were assessed by both authors independently for eligibility. Hand searching reference lists of highly relevant articles was also performed to identify additional studies. Inclusion criteria were purposely broad given the comprehensive nature of our research question and comprised of the following: (a) studies that collected or reported on experience data directly from parents/caregivers of a child with ASD; and (b) the diagnostic assessment or time surrounding diagnosis was specifically assessed. We decided not to include unpublished, non-peer-reviewed articles due to the considerable number of publications in peer-reviewed journals as well as the extensive number of unpublished theses found in this subject area, which led to concerns about the feasibility of accurately capturing the gray literature in our narrative synthesis of the study results. Non-English articles were excluded due to inability for the authors to accurately extract data. Consensus for inclusion was achieved between authors in face-to-face discussion. All articles were accessed electronically.

Stage 4: Charting and Analyzing the Data

Descriptive characteristics including the year of publication, country of origin, study methodology, and study objectives were extracted by AM using a customized data extraction sheet which was developed in a draft during protocol development. Findings related to parent perceptions of ASD diagnosis were also charted. This section of the data extraction form was trialed and refined in an iterative manner as familiarity with the data increased. The parent perceptions of the various components of the diagnostic process on which each article focused were identified and charted by AM. These key findings were then grouped under overarching themes which were organized into an inductive conceptual framework constructed through regular discussion between AM and MP. GK and LH reviewed and provided input on the final themes based on synthesized results .

Stage 5: Summarizing and Reporting the Results

The results were summarized in chart format with regard to time, location, and methodology. Quantitative analysis of parental perceptions is presented in tables indicating the frequency of themes in articles. Qualitative analysis of themes is presented narratively. A narrative synthesis format was chosen to discuss results as articles varied in terms of research design and data outcomes.

Search Results

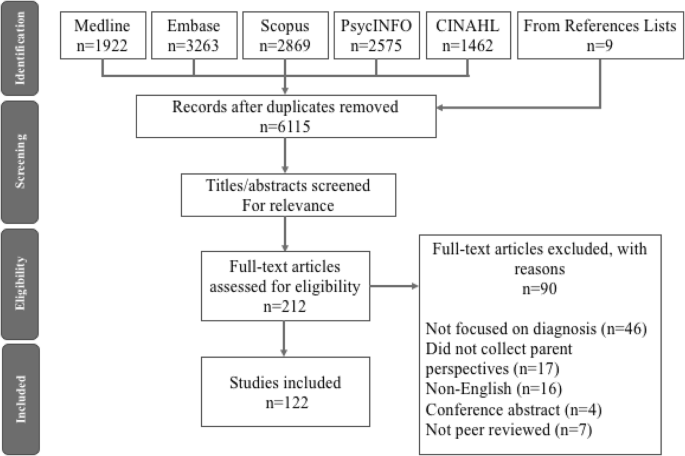

Figure 1 outlines the study retrieval and selection results. The electronic search resulted in 6115 records . Two hundred and twelve articles were identified as potentially relevant. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 122 articles were included.

Identification of included articles (PRISMA diagram)

Year of Publication

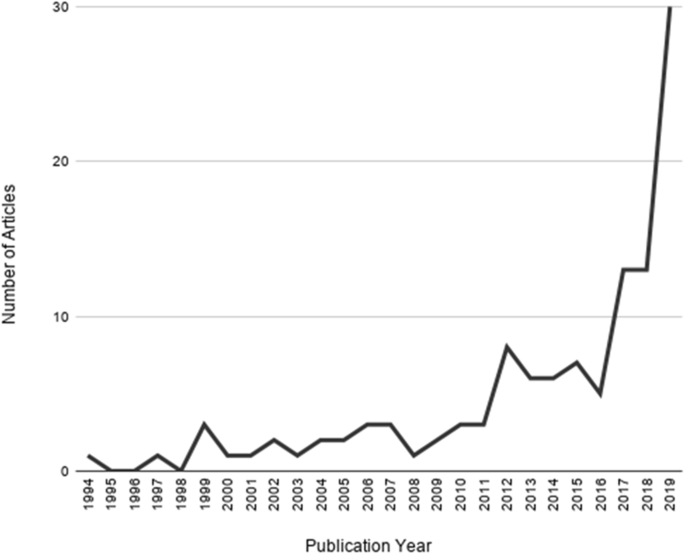

Studies were charted by year of publication demonstrating an increase in publications on the topic over the last decade with a dramatic increase in articles published since 2017 (see Fig. 2 ).

Number of articles by publication year

Study Methodology

Study methodology is summarized in Table 2 . More than half of the studies used qualitative methodology ( n = 66) with the majority analyzing data from interviews and focus groups asking parents about their experience of receiving a diagnosis of ASD for their child. Almost one-quarter of the studies were quantitative questionnaire-based studies of parent perceptions of ASD diagnosis ( n = 28). Mixed-methods studies made up 16% ( n = 20) of the literature reviewed, mainly where questionnaire data was analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively or interview and questionnaire data were combined.

Secondary research reflected the significant amount of qualitative literature in the area with our review finding four qualitative meta-syntheses of parent experiences. One systematic review and meta-synthesis looked at qualitative literature about the parental experience of their child receiving a diagnosis of ASD in the UK (Legg and Tickle 2019 ). Two meta-syntheses by the same author group looked at parental perceptions of advocating for their child with ASD, one specifically during the diagnostic process (Boshoff et al. 2019 ) and the other across the lifespan including diagnosis (Boshoff et al. 2018 ). One meta-synthesis looked at parental perceptions of caring for a child with ASD, in which the diagnostic experience was found to be a major theme (DePape and Lindsay 2016 ). Three non-systematic literature reviews that included discussion of literature on parental experience of ASD diagnosis were also found (Bloch and Weinstein 2009 ; Reed and Osborne 2012 ; Sritharan and Koola 2019 ). One commentary authored by a parent containing their personal experience with receiving an ASD diagnosis for their child was also published (Henderson 2017 ).

Location of Studies

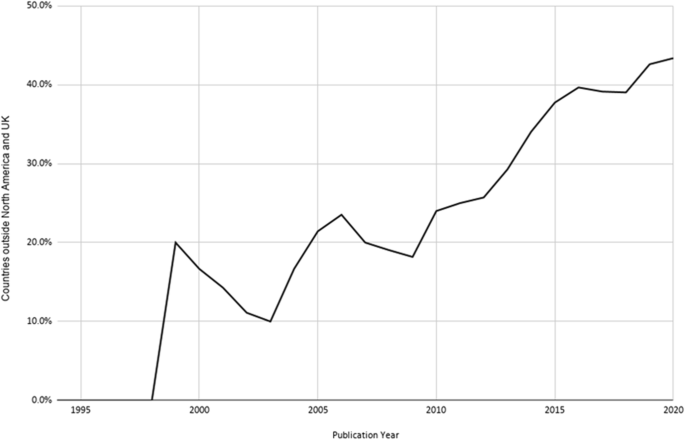

Studies were charted by country of origin and this data was further categorized using the World Bank’s regional and income classification system (The World Bank 2019 ). Until 2004, all but one study took place in the UK or North America. After that time, studies from international sources have increased (see Fig. 3 ). However, over three-quarters of all primary studies were conducted in Europe and North America and 83% of studies were performed in high-income countries (see Tables 3 and 4 ).

Cumulative percentage of articles from countries outside of the UK and North America

Specific Populations

During the last decade, there has been an interest in looking at the unique diagnostic experiences of specific subgroups of parents and their children, including research focused on the experience of parents of girls with ASD (Rabbitte et al. 2017 ), autistic adults (Raymond-Barker et al. 2018 ), children with ASD who have visual impairment (de Verdier et al. 2019 ), and children with ASD who have hearing impairment (Wiley et al. 2014 ). Also, experiences of fathers of children with ASD (Hannon and Hannon 2017 ; Potter 2017 ), African American parents in the USA (Lovelace et al. 2018 ; Pearson and Meadan 2018 ), Latino parents in the USA (Lopez et al. 2018 ; Zuckerman et al. 2014 , 2017 ), immigrant families (Nilses et al. 2019 ; Rivard et al. 2019 ; Sakai et al. 2019 ), and military families (Cramm et al. 2019 ) have been studied.

Key Study Findings

Parental perceptions of ASD diagnosis were coded and organized into themes which were formed into an inductive conceptual framework identifying four central parts of the diagnostic experience for parents: (1) the journey to assessment, (2) the assessment process, (3) delivery of the diagnosis and feedback session, and (4) post-diagnostic provision of information, resources, and support. In addition, themes of parental emotions and reactions at the time of diagnosis and parental satisfaction were also identified. The frequency and presence of these themes in the articles of our review are displayed in Appendix Table 5. Experiences of the diagnostic process vary considerably given the heterogeneity of effects of ASD on individuals, characteristics, and experiences of caregivers, as well as regional variation in ASD diagnostic practice. In the proceeding narrative synthesis, we attempt to articulate the current state of knowledge of parental perceptions of ASD diagnosis based on the key themes identified in our review.

The Journey to Assessment

Of all the parts of the diagnostic experience, parental perceptions of the journey to assessment is the most studied aspect with 70% of articles ( n = 85) in our review containing findings related to this theme. Overall, the journey to ASD diagnosis is perceived by parents as fraught with delays. The most common way studies measured this delay was with parent-reported time lapse from age of first concern to age of diagnosis with averages ranging from 12 months to 55 months (Bejarano-Martín et al. 2019 ; Chao et al. 2018 ; Crane et al. 2016 ; Hofer et al. 2019 ; Martinez et al. 2018 ; Moh and Magiati 2012 ; Ribeiro et al. 2017 ; Schelly et al. 2019 ). Studies also recorded parent-reported number of professionals consulted in order to obtain a diagnosis with an average of three to five professionals seen (Eggleston et al. 2019 ; Goin-Kochel et al. 2006 ; Hofer et al. 2019 ; Howlin and Asgharian 1999 ; Mahapatra et al. 2019 ; Siklos and Kerns 2007 ; Wong et al. 2017 ). The perceived barriers to timely ASD diagnosis by parents were studied in many articles and the most often reported include (1) false reassurance or dismissal of concerns by health care practitioners (Barnard-Brak et al. 2017 ; Boshoff et al. 2019 ; Brookman-Frazee et al. 2012 ; Chamak and Bonniau 2013 ; Chamak et al. 2011 ; Dababnah and Bulson 2015 ; de Verdier et al. 2019 ; Elder et al. 2016 ; Ferguson and Vigil 2019 ; Henderson 2017 ; Hidalgo et al. 2015 ; Legg and Tickle 2019 ; Lopez et al. 2018 ; Lovelace et al. 2018 ; Navot et al. 2017 ; Oswald et al. 2017 ; Pearson et al. 2020 ; Ribeiro et al. 2017 ; Sansosti et al. 2012 ; Schelly et al. 2019 ; Smith-Young et al. 2020 ; Stahmer et al. 2019 ; Sudhinaraset and Kuo 2013 ; Upoma et al. 2020 ; Wong et al. 2017 ), (2) lack of expertise in ASD diagnosis among consulted health care practitioners (An et al. 2020 ; Brookman-Frazee et al. 2012 ; Crane et al. 2018 ; Lloyd et al. 2019 ; Mitchell and Holdt 2014 ; Pearson and Meadan 2018 ; Pearson et al. 2020 ; Raymond-Barker et al. 2018 ; Reddy et al. 2019 ; Sansosti et al. 2012 ; Zarafshan et al. 2019 ), (3) lack of awareness and knowledge among parents of ASD signs and symptoms (An et al. 2020 ; Chao et al. 2018 ; Crane et al. 2018 ; Elder et al. 2016 ; Rivard et al. 2019 ; Schelly et al. 2019 ; Zuckerman et al. 2014 , 2017 ), (4) misdiagnosis or need for further referral extending wait times (Brookman-Frazee et al. 2012 ; Lloyd et al. 2019 ; Martinez et al. 2018 ; Rabbitte et al. 2017 ; Smith-Young et al. 2020 ; Stahmer et al. 2019 ; Upoma et al. 2020 ), (5) parental denial (Chao et al. 2018 ; Clasquin-Johnson and Clasquin-Johnson 2018 ; Crane et al. 2018 ; Dababnah et al. 2018 ; Hidalgo et al. 2015 ; Pearson and Meadan 2018 ; Sakai et al. 2019 ), (6) waitlist times for assessment (Lappe et al. 2018 ; Legg and Tickle 2019 ; Raymond-Barker et al. 2018 ; Sakai et al. 2019 ; Wong et al. 2017 ; Yi et al. 2020 ), and (7) cultural beliefs and differences that act as barriers to diagnosis (Dababnah et al. 2018 ; Mahapatra et al. 2019 ; Pearson and Meadan 2018 ; Reddy et al. 2019 ; Rivard et al. 2019 ; Sritharan and Koola 2019 ; Stahmer et al. 2019 ; Zeleke et al. 2018 ; Zuckerman et al. 2014 ).

The Assessment Process

There has been comparatively less research focus on parental perceptions of the diagnostic assessment process itself. Research on parental perceptions in this area tends to have a mix of positive and negative perception which may be related to practice variation in service delivery across studies. Many studies collected information on structural aspects of the diagnostic assessment such as who completed the assessment (Brogan and Knussen 2003 ; Crane et al. 2016 ; Daniels et al. 2017 ; Eggleston et al. 2019 ; Goin-Kochel et al. 2006 ; Hackett et al. 2009 ; Osborne and Reed 2008 ; Rhoades et al. 2007 ; Siklos and Kerns 2007 ; Zarafshan et al. 2019 ), where the assessment took place (Brogan and Knussen 2003 ; Renty and Roeyers 2006 ), and how long it took (Ha et al. 2017 ; Raymond-Barker et al. 2018 ). A number of studies reporting on parental perceptions of the process include comments on the length and perceived thoroughness of the overall assessment process with some studies reporting parents felt the process was too lengthy and overly comprehensive (Mulligan et al. 2012 ; Wong et al. 2017 ) and others reporting that the assessment was perceived as too short and superficial (Ha et al. 2017 , Selimoglu et al. 2013 ; Yi et al., 2020 ; Zarafshan et al. 2019 ). Some studies commented on parental perceptions of validity of methods used for assessment (Bejarano-Martín et al. 2019 ; Crane et al. 2018 ; Ha et al. 2017 ; Ho et al. 2014 ; Raymond-Barker et al. 2018 ; Wiley et al. 2014 ; Zarafshan et al. 2019 ) and professional’s qualifications, experience, or competence (Bejarano-Martín et al. 2019 ; Carlsson et al. 2016 ; de Verdier et al. 2019 ; Harrington et al. 2006 ; Wiley et al. 2014 ) with a mix of positive and negative perceptions. In a few studies, parents reported wanting to be prepared for the assessment with information on the nature and structure of the assessment upfront (Braiden et al. 2010 ; Hackett et al. 2009 ; Mockett et al. 2011 ). Desire and appreciation for parental involvement and collaboration with assessor was reported in a number of studies (Ha et al. 2017 ; Moh and Magiati 2012 ; Selimoglu et al. 2013 ; Wiley et al. 2014 ). Some studies commented on private assessment practices being perceived as superior to publicly funded assessments and also noting that the associated shorter wait times were also desirable (Ho et al. 2014 ; Hurt et al. 2019 ).

Two studies in this review compared parental perceptions between different diagnostic models (Ahlers et al. 2019 ; Reese et al. 2013 ). One study looked at parental perceptions of a model where assessment for ASD was done first by general pediatricians with only uncertain cases being referred for further assessment by psychologists compared with a model where all cases referred for psychologist ASD assessment. It found no significant differences in parental satisfaction, perceptions of family-centered care, or shared decision-making between the two models of assessment (Ahlers et al. 2019 ). The other study compared the process of completing diagnostic tools including the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised and the Autism Diagnostic Observational Schedule (Module 1) in-person versus using teleconferencing technology. The study found no significant difference in parent satisfaction when comparing both methods (Reese et al. 2013 ).

Delivery of the Diagnosis and Feedback Session

Nearly one-third of articles ( n = 39) in our review reported parental perceptions of the delivery of the ASD diagnosis and feedback session. Findings indicate that the tone and approach employed when delivering the diagnosis of ASD is very important to parents. Caregivers report that they want professionals delivering the diagnosis to be empathetic (Finnegan et al. 2014 ; Ho et al. 2014 ; Jegatheesan et al. 2010 ; Molteni and Maggiolini 2015 ; Nissenbaum et al. 2002 ; Osborne and Reed 2008 ). Parents desire a strength-based approach that highlights positive attributes about their child and they want to hear optimistic statements about prognosis and intervention that preserve hope (Abbott et al. 2013 ; Crane et al. 2018 ; Mulligan et al. 2012 ; Nissenbaum et al. 2002 ). On a practical level, parents report wanting opportunity to ask questions and time to process the information provided (Abbott et al. 2013 ; Brogan and Knussen 2003 ; Molteni and Maggiolini 2015 ). Parents appreciate and desire discussion about prognosis and what might be expected in the future (Braiden et al. 2010 ; de Alba and Bodfish 2011 ; Hennel et al. 2016 ; Ho et al. 2014 ; Molteni and Maggiolini 2015 ; Osborne and Reed 2008 ).

A number of studies reported that parents perceived inadequate explanation of their child’s diagnosis (Samadi et al. 2012 ; Selimoglu et al. 2013 ; Yi et al., 2020 ; Zarafshan et al. 2019 ) whereas a few studies contained parental reports of being overwhelmed by the amount of information provided during the feedback (Abbott et al. 2013 ; Jashar et al. 2019 ; Renty and Roeyers 2006 ). Several studies found that when children have been given tentative diagnoses of “probably,” “suspected,” and “borderline” ASD as well as “autistic traits, tendencies, or features” this leads to parental confusion and lower levels of satisfaction (Brogan and Knussen 2003 ; Ho et al. 2014 ; Molteni and Maggiolini 2015 ; Samadi et al. 2012 ). Some studies reported a perceived hierarchical relationship between the physician and parent impacting effectiveness of communication (Carlsson et al. 2016 ; Ha et al. 2017 ; Ho et al. 2014 ).

Post-diagnostic Provision of Information, Resources, and Support

The provision of information and support immediately post-diagnosis was reviewed in more than one-third of the articles ( n = 46) included in our review. Studies repeatedly showed that information at diagnosis is extremely important to parents. In particular, parents report that they value and desire information and recommendations that are tailored to the specific needs of their child, as opposed to more generic information on ASD (Crane et al. 2016 ; de Verdier et al. 2019 ; Hennel et al. 2016 ; Ho et al. 2014 ; Nissenbaum et al. 2002 ; Renty and Roeyers 2006 ; Sansosti et al. 2012 ). Specifically, caregivers report that being provided with information on intervention services (de Alba and Bodfish 2011 ; Hennel et al. 2016 ; Moh and Magiati 2012 ; Tait et al. 2016 ) and about school support (de Alba and Bodfish 2011 ; Hennel et al. 2016 ; Renty and Roeyers 2006 ) is highly important. Two studies reported that parents find it beneficial if they receive written information (Brogan and Knussen 2003 ; Chamak et al. 2011 ). In three studies, parents expressed a desire to be connected to other parents who have a child diagnosed with ASD where they could be provided with practical advice from other caregivers (de Verdier et al. 2019 ; Osborne and Reed 2008 ; Stahmer et al. 2019 ).

The post-diagnosis support provided to caregivers was widely reported to be unsatisfactory and an area of particular concern (Crane et al. 2016 ; Dababnah and Bulson 2015 ; Hurt et al. 2019 ; Jacobs et al. 2020 ; Legg and Tickle 2019 ; Mitchell and Holdt 2014 ; Potter 2017 ; Rasmussen et al. 2020 ; Raymond-Barker et al. 2018 ; Tait et al. 2016 ). Parents feel “alone” and abandoned after the diagnosis (Carlsson et al. 2016 ; Ho et al. 2014 ; Jegatheesan et al. 2010 ; Raymond-Barker et al. 2018 ; Tait et al. 2016 ) and multiple studies reported parental desire for further support and direction with service navigation and coordination (de Verdier et al. 2019 ; Legg and Tickle 2019 ; Pearson et al. 2020 ; Rabba et al. 2019 ; Tait et al. 2016 ). A number of studies mentioned barriers to accessing interventions including lack of referral to interventions provided (Yi et al., 2020 ; Zarafshan et al. 2019 ), language barriers (Ferguson and Vigil 2019 ; Jegatheesan et al. 2010 ; Sakai et al. 2019 ), and the need to advocate in order to get support (Carlsson et al. 2016 ; Mulligan et al. 2012 ; Rabbitte et al. 2017 ).

Parental Emotions and Reactions Around the Time of Diagnosis

Parent’s self-reported emotional reactions around the time of diagnosis were reported or analyzed in over half of all included articles ( n = 64) in this review (see Appendix Table 5). Overall, the literature indicates that receiving a diagnosis of ASD for their child is an emotionally intense experience for parents. Parents reported a range of difficult reactions to a diagnosis of ASD in their child including the commonly described feelings of shock, sadness, stress, grief, denial, guilt, anger, and worry. A number of studies reported that parents felt the diagnosis of ASD was associated with stigma which led to shame and isolation (Russell and Norwich 2012 ; Sakai et al. 2019 ; Sansosti et al. 2012 ; Tait et al. 2016 ). However, the most frequently cited reaction to the diagnosis across studies was relief, and parents also report positive aspects of the diagnosis including providing an explanation for their child’s behavior for which they are not to blame (Jacobs et al. 2020 ; Nissenbaum et al. 2002 ; Reddy et al. 2019 ) and as a means of accessing support for their child (Chamak et al. 2011 ; Chell 2006 ; Nissenbaum et al. 2002 ; Osborne and Reed 2008 ; Rasmussen et al. 2020 ; Russell and Norwich 2012 ).

Satisfaction

Parental satisfaction was examined in more than three-quarters of quantitative studies ( n = 23) in this review (see Appendix Table 5). A majority of the studies measured parental satisfaction with the diagnostic process overall (Chamak and Bonniau 2013 ; Chamak et al. 2011 ; Crane et al. 2016 ; Eggleston et al. 2019 , Goin-Kochel et al. 2006 ; Hidalgo et al. 2015 ; Hofer et al. 2019 ; Howlin and Asgharian 1999 ; Howlin and Moore 1997 ; Jashar et al. 2019 ; Renty and Roeyers 2006 ; Sansosti et al. 2012 ; Siklos and Kerns 2007 ; Yi et al., 2020 ) and some studies measured satisfaction with various components of the process such as: professional response to initial concerns (Bejarano-Martín et al. 2019 ), wait times for assessment (Bejarano-Martín et al. 2019 ; Eggleston et al. 2019 ), methods used for assessment (Bejarano-Martín et al. 2019 ; Raymond-Barker et al. 2018 ), communication style of the diagnosing professional (Bejarano-Martín et al. 2019 ; Brogan and Knussen 2003 ; Crane et al. 2016 ), information provided at diagnosis (Bejarano-Martín et al. 2019 ; Brogan and Knussen 2003 ; Chiu et al. 2014 ; Crane et al. 2016 ; Mansell and Morris 2004 ; Raymond-Barker et al. 2018 ), the diagnostic report (Eggleston et al. 2019 ) and post-diagnostic supports (Bejarano-Martín et al. 2019 ; Crane et al. 2016 ; Eggleston et al. 2019 ; Mansell and Morris 2004 ). While the majority of studies used Likert scales to measure satisfaction, there is inconsistency between studies with how the scales were defined. Studies also examined the correlation between overall satisfaction with the diagnostic process and other factors such as age of child at diagnosis (Brogan and Knussen 2003 ; Goin-Kochel et al. 2006 ; Renty and Roeyers 2006 ; Siklos and Kerns 2007 ), severity level, or features of ASD (Brogan and Knussen 2003 ; Howlin and Asgharian 1999 ; Jashar et al. 2019 ; Moh and Magiati 2012 ), parent income and/or education level (Goin-Kochel et al. 2006 ; Hidalgo et al. 2015 ; Jashar et al. 2019 ) and family race/ethnicity (Jashar et al. 2019 ). A few studies have correlated decreased satisfaction with increased parental reported stress levels during the diagnostic period (Crane et al. 2016 ; Jashar et al. 2019 ; Moh and Magiati 2012 ). Perhaps unsurprisingly, multiple studies have found that delay in diagnosis correlated with decreased levels of parental satisfaction with the diagnostic process overall (Bejarano-Martín et al. 2019 ; Crane et al. 2016 ; Goin-Kochel et al. 2006 ; Howlin and Moore 1997 ; Howlin and Asgharian 1999 ; Mansell and Morris 2004 ; Moh and Magiati 2012 ; Sansosti et al. 2012 ; Wong et al. 2017 ). Studies also made attempts to see how other key aspects of the diagnostic process affect overall satisfaction. Overall satisfaction has been found to positively correlate with satisfaction with the following areas: professional’s initial reactions to first concerns (Brogan and Knussen 2003 ), manner of the diagnosing professional (Brogan and Knussen 2003 ; Crane et al. 2016 ; Moh and Magiati 2012 ), information provided at diagnosis (Brogan and Knussen 2003 ; Crane et al. 2016 ; Moh and Magiati 2012 ; Renty and Roeyers 2006 ), the diagnostic report (Eggleston et al. 2019 ), and post-diagnostic supports (Crane et al. 2016 ). Across studies results of correlation attempts have been inconsistent and there is great variation in how these correlates were measured.

This review summarizes the growing body of research on parent perceptions of ASD diagnosis using systematic methods. Over the last two decades, research on the topic has evolved from focusing on studies originating in North America and the UK to a more global perspective, reflective of increasing research activity and awareness of ASD around the world. However, over three-quarters of studies in this review still took place in Europe and North America among high-income countries. As we anticipate the global interest in research of the diagnostic experience to continue to grow and evolve, research synthesizing perspectives by location, such as the recent meta-synthesis from the UK by Legg and Tickle ( 2019 ), would be helpful to further understanding how to improve systems on a local level. Our work also showed that more recent research has begun examining the unique experiences of different subgroups of children and parents, showing recognition of the fact that receiving a diagnosis of ASD for one’s child is a complex and individual experience influenced by personal, cultural, and environmental factors.

The current review revealed four central components of the diagnostic experience that are often studied: the journey to assessment, the diagnostic assessment itself, delivery of the diagnosis, and provision of information and support. Many articles in the review also studied parental emotions at the time of diagnosis and many measured parental satisfaction with the diagnostic process. While some jurisdictions were able to show a general trend over time towards increasing satisfaction among parents (Chamak et al. 2011 ; Crane et al. 2016 ), overall this review revealed many aspects of the diagnostic process that should be highlighted for improvement.

This review shows that wait times for diagnostic assessment have been a persistent concern among parents over the years with many families reporting their journey to diagnosis lasting multiple years. This is a concern from a public health perspective; delay in accessing diagnosis often means delay in accessing early therapies, which have been shown to be more effective at younger ages (Perry et al. 2011 ). Multiple studies in this review reveal that the wait period between initial referral for concerns and assessment is especially anxiety provoking and affects families’ overall satisfaction with the diagnostic process (Abbott et al. 2013 ; Bejarano-Martín et al. 2019 ; Crane et al. 2016 ; Goin-Kochel et al. 2006 ; Howlin and Moore 1997 ; Howlin and Asgharian 1999 ; Mansell and Morris 2004 ; Moh and Magiati 2012 ; Sansosti et al. 2012 ; Wong et al. 2017 ). This presents a strong argument to provide families with clear expectations for an expected length of wait for a diagnosis, as well as efforts to help families feel supported while they wait. Research examining how best to build capacity for diagnosis to reduce wait times and support timely access to services has the potential to improve the diagnostic experience for families.

Our review also indicates that parents perceive cultural barriers and stigma as contributors to delays in their decision to access diagnosis (Dababnah et al. 2018 ; Mahapatra et al. 2019 ; Pearson and Meadan 2018 ; Reddy et al. 2019 ; Rivard et al. 2019 ; Sritharan and Koola 2019 ; Stahmer et al. 2019 ; Zeleke et al. 2018 ; Zuckerman et al. 2014 ). Identifying and addressing such cultural factors could influence early detection for many families. There is a need for initiatives that address cultural barriers and stigma as well as for increasing the amount, quality, and diversity of research in this area for a more comprehensive understanding of the factors and how best to address them. In the interim, clinicians should seek to understand parents’ experiences of their child’s diagnosis and potential cultural influences on the family’s perception of diagnosis in order to provide supports and services that are best tailored and beneficial to the family. There is research to indicate that the impact of stigma tends to decrease over time as parents form social networks of people who accept their child’s ASD diagnosis (Gray 2002 ). Practitioners should attempt to connect families to support networks early. Longer term studies demonstrate that many parents describe benefits to caring for a child with ASD such as becoming more patient, less judgmental, and better at coping with life’s challenges (DePape and Lindsay 2016 ). Our review revealed that connecting families with experienced peer supports is desired (de Verdier et al. 2019 ; Osborne and Reed 2008 ; Stahmer et al. 2019 ) and may help dispel negative stereotypes and highlight these rewards of caring for a child with ASD.

Attitudes and knowledge of professionals were also reported to be a barrier to diagnosis from the parent perspective in our review. Early identification of ASD is complex due to the significant heterogeneity in presentation (Anagnostou et al. 2014 ). It is clear, however, that professionals should be careful not to dismiss early parental concerns. In fact, recent research confirms that parents are often more accurate than clinicians in identifying clinically relevant behaviors in toddlers with ASD based on their day-to-day observations (Sacrey et al. 2018 ). Primary care providers have been shown to often be parents’ first point of contact after a concern has been identified and education efforts focused on this group are likely to improve access to diagnosis (Hyman et al. 2020 ).

Our review revealed that little attention has been given to parent perceptions of diagnostic assessment methods. This is in contrast to the amount of research examining the diagnostic accuracy of various tools for diagnosis (Randall et al. 2018 ). A recent Canadian study examining self-reported practice patterns and wait times for ASD diagnosis revealed an association between longer time spent on assessment and longer total wait from referral to diagnosis (Penner et al. 2018 ). Our review found that parents prefer to know what to expect in terms of length and components of the assessment ahead of time and that they expect the diagnostician or diagnostic team to collaborate with them, taking the time to understand their perspectives as experts on their own children (Ha et al. 2017 ; Moh and Magiati 2012 ; Selimoglu et al. 2013 ; Wiley et al. 2014 ). However, further study is needed to examine acceptability of different assessment methods and diagnostician characteristics (i.e., multi-disciplinary team versus solo practitioner, generalist versus sub-specialist). In our review, two studies comparing different diagnostic models examined parent acceptability (Ahlers et al. 2019 ; Reese et al. 2013 ). Future studies examining the accuracy and efficiency of different assessors and assessment methods should also consider parent acceptability as this has the potential to affect acceptance of the diagnosis and sets the tone for future interactions with healthcare and support services.

Our review highlights that parent preferences in regard to diagnosis delivery echo many of the themes noted in studies of parents receiving a diagnosis of other childhood disabilities, chronic diseases, and even life-threatening illness (Sardell and Trierweiler 1993 ; Sharp et al. 1992 ; Sloper and Turner 1993 ). Parents receiving life-changing diagnoses want clarity, transparency, compassion, and optimism. They remember in vivid detail their diagnostic experiences and perceive the delivery of the diagnosis as framing their experience going forward either positively or negatively. They also perceive that the delivery of the diagnosis affects their future coping and adjustment. The Autism Treatment Network Guide for Providing Effective Feedback to Families Affected by Autism (Austin et al. 2012 ) contains practical recommendations for ASD diagnosis delivery, including preparing for the session, discussing the child’s strengths, prioritizing next steps, and providing written information. However, no guideline can provide the best response for each question posed by each family. Our study showed variation in preferences among parents, such as individual differences in the preferred amount and form in which information is provided. This speaks to the additional requirement that providers be flexible and able to adjust in real-time to the family in front of them.

Our review found that challenges and stress associated with navigating the healthcare system persist long after diagnosis. Diagnosis appears to be just one event in an ongoing series of adaptations. Our review highlighted that parents often feel alone and burdened with educating themselves on how best to care for their child. However, reviews that take a longer lifespan perspective indicate that parents often evolve from feeling dissatisfied with the information received to feeling empowered as advocates for their child (DePape and Lindsay 2016 ). A recent qualitative study on parent engagement showed the close relationship between parent engagement and the process of navigating the system (Gentles et al. 2019 ). Parents themselves have suggested various supports that could be helpful during this period including one-stop access to therapy, access to advisors, and other case coordination support (Legg and Tickle 2019 ; Pearson et al. 2020 ; Rabba et al. 2019 ; Tait et al. 2016 ). As current early identification efforts are happening in the context of limited publicly funded services and long waitlists for therapy, innovative treatment delivery models are likely required. Some parents are highly motivated to take action to help their children during this time, and parent-mediated therapies such as Social ABCs (Brian et al. 2017 ) and Joint Attention Symbolic Play and Engagement Regulation (JASPER; Shire et al. 2016 ) may present effective options.

Parent perspectives in our review show alignment as well as important differences when compared with the perspectives of professionals and service providers in studies. Like parents, professionals are concerned about accessibility and have also indicated a need to improve knowledge and training of professionals referring individuals to ASD diagnostic services, to create effective referral pathways, and to reduce wait times (Rogers et al. 2016 ). Studies of professionals’ perceptions indicate that one of the most helpful aspects of an ASD diagnosis is the practical supports that the diagnosis opens up in terms of information, explanation, and supports (Jacobs et al. 2018 ). Our review indicates that while parents are seeking supports, they perceive that the supports they receive are often lacking, leaving them responsible for information-seeking and navigation. Clinicians should be mindful of this gap between their perceived utility of the ASD diagnosis and the perceptions of families, who shoulder much of the post-diagnostic work of accessing information and services. The concern from professionals about managing distress and appropriately tailoring information to the needs of parents (Rogers et al. 2016 ) indicates that diagnosticians are acutely aware of the emotional impact of delivering a diagnosis and they see the value of adapting information to the family in front of them.

Our review revealed that for parents, receiving a diagnosis of ASD for their child is an emotionally complex process. While our review revealed a diverse range of challenging emotions experienced, many parents also reflected on positive aspects of diagnosis. Helping parents frame diagnosis around these positive aspects, which include providing understanding of their child’s behavior, relieving guilt and self-blame, and as a means of accessing support, may help parents adjust to the diagnosis. At the same time, denial appeared to be a common barrier and parental reaction to diagnosis. Clinicians need to validate that the experience of receiving a diagnosis can be scary and they should try to meet parents where they are at in their personal emotional process. Relational continuity between care providers and families allows reactions and perceptions to be revisited and is likely to be particularly beneficial.

In addition to the gaps in research already highlighted, a major limitation of the current literature is the inconsistency of tools used to measure parent satisfaction, which tends to be a poorly defined term. Because of this variability, meta-analysis of the existing quantitative literature is not currently possible. Studies interested in measuring trends in parent satisfaction over time or with adjustments to the process should give consideration to using consistent scales and validated tools, such as the Measures of Processes of Care (King et al. 1995 ), a standardized measure of perceptions of family-centeredness of care.

There are some limitations associated with this review. Although we had intended to include gray literature, due to the large number of articles we retrieved in the scientific literature, we were unable to extend our search to gray literature, excluding many thesis projects in the area. This would be important to note and consider if any further qualitative syntheses of the literature are being performed. As well, we limited the included studies to those disseminated in English, which may have decreased the international content and therefore limits generalizability of our results. Despite this limitation, the review still captured many studies from around the world, adding a global perspective to our synthesis. Due to the heterogeneity of methodological approaches in the literature at this time, a scoping review with narrative summary was selected as the most appropriate method but we anticipate that as the body of the literature continues to grow, other more precise methods of analysis will be possible and more appropriate including meta-synthesis and meta-analysis.

This scoping review revealed a growing body of literature looking at the experience of parents during ASD diagnostic assessment. In recent years, there has been a shift in the literature towards understanding the unique experiences of different subgroups of parents and children and a more global perspective in the literature, although gaps remain in terms of understanding the full breadth of factors that influence the diagnostic experience for all families. Researchers are encouraged to study parent acceptability with the evolution of diagnostic pathways. There are certain elements of the diagnostic experience that have been studied in depth including the path to assessment, the diagnostic assessment itself, the delivery of the diagnosis, and provision of supports. Despite variation in experience and satisfaction, studies indicate that diagnosis is a uniquely stressful and emotionally intense experience for parents.

Abbott, M., Bernard, P., & Forge, J. (2013). Communicating a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder-a qualitative study of parents’ experiences. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 18 (3), 370–382.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ahlers, K., Gabrielsen, T., Ellzey, A., Brady, A., Litchford, A., Fox, J., et al. (2019). A pilot project using pediatricians as initial diagnosticians in multidisciplinary autism evaluations for young children. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 40 (1), 1–11.

Article Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

An, S., Chan, C. K., & Kaukenova, B. (2020). Families in transition: Parental perspectives of support and services for children with autism in Kazakhstan. International Journal of Disability, Development & Education, 67 (1), 28–44.

Anagnostou, E., Zwaigenbaum, L., Szatmari, P., Fombonne, E., Fernandez, B. A., Woodbury-Smith, M., et al. (2014). Autism spectrum disorder: advances in evidence-based practice. CMAJ, 186 (7), 509–519.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8 (1), 19–32.

Austin, H., Katz, T., & Reyes, J.P.M. (2012). A clincian’s guide to providing effective feedback to families affected by autism. Retrieved from New York, NY: https://www.autismspeaks.org/tool-kit/atnair-p-guide-providing-feedback-families-affected-autism . Accessed 29 November 2020.

Barnard-Brak, L., Richman, D., Ellerbeck, K., & Moreno, R. (2017). Health care provider responses to initial parental reports of autism spectrum disorder symptoms: results from a nationally representative sample. Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 22 (1), 30–35.

Bejarano-Martín, Á., Canal-Bedia, R., Magán-Maganto, M., Fernández-Álvarez, C., Cilleros-Martín, M. V., Sánchez-Gómez, M. C., et al. (2019). Early detection, diagnosis and intervention services for young children with autism spectrum disorder in the European Union (ASDEU): family and professional perspectives. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50 (9), 3380–3394 (2020).

Bloch, J. S., & Weinstein, J. D. (2009). Families of young children with autism. Social Work in Mental Health, 8 (1), 23–40.

Boshoff, K., Gibbs, D., Phillips, R. L., Wiles, L., & Porter, L. (2018). Parents’ voices: ‘our process of advocating for our child with autism.’ A meta-synthesis of parents’ perspectives. Child: Care, Health & Development, 44 (1), 147–160.

Boshoff, K., Gibbs, D., Phillips, R. L., Wiles, L., & Porter, L. (2019). A meta-synthesis of how parents of children with autism describe their experience of advocating for their children during the process of diagnosis; 30548710. Health and Social Care in the Community, 27 (4), e143–e157.

Braiden, H.-J., Bothwell, J., & Duffy, J. (2010). Parents’ experience of the diagnostic process for autistic spectrum disorders. Child Care in Practice, 16 (4), 377–389.

Brian, J. A., Smith, I. M., Zwaigenbaum, L., & Bryson, S. E. (2017). Cross-site randomized control trial of the Social ABCs caregiver-mediated intervention for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 10 (10), 1700–1711.

Brian, J. A., Zwaigenbaum, L., & Ip, A. (2019). Standards of diagnostic assessment for autism spectrum disorder. Paediatrics & Child Health, 24, 444–451.

Brogan, C. A., & Knussen, C. (2003). The disclosure of a diagnosis of an autistic spectrum disorder: determinants of satisfaction in a sample of Scottish parents. Autism, 7 (1), 31–46.

Brookman-Frazee, L., Baker-Ericzén, M., Stadnick, N., & Taylor, R. (2012). Parent perspectives on community mental health services for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child and Family Studies . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9506-8 .

Carlsson, E., Miniscalco, C., Kadesjö, B., & Laakso, K. (2016). Negotiating knowledge: Parents’ experience of the neuropsychiatric diagnostic process for children with autism. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 51 (3), 328–338.

Chamak, B., & Bonniau, B. (2013). Changes in the diagnosis of autism: how parents and professionals act and react in France. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 37 (3), 405–426.

Chamak, B., Bonniau, B., Oudaya, L., & Ehrenberg, A. (2011). The autism diagnostic experiences of French parents. Autism, 15 (1), 83–97.

Chao, K.-Y., Chang, H.-L., Chin, W.-C., Li, H.-M., & Chen, S.-H. (2018). How Taiwanese parents of children with autism spectrum disorder experience the process of obtaining a diagnosis: a descriptive phenomenological analysis; 28205453. Autism, 22 (4), 388–400.

Chell, N. (2006). Experiences of parenting young people with a diagnosis of Asperger syndrome: a focus group study. The International Journal of Psychiatric Nursing Research, 11 (3), 1348–1358.

PubMed Google Scholar

Chiu, Y.-N., Chou, M.-C., Lee, J.-C., Wong, C.-C., Chou, W.-J., Wu, Y.-Y., et al. (2014). Determinants of maternal satisfaction with diagnosis disclosure of autism. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 113 (8), 540–548.

Clasquin-Johnson, M., & Clasquin-Johnson, M. (2018). ‘How deep are your pockets?’ Autoethnographic reflections on the cost of raising a child with autism. African Journal of Disability, 7 , 356.

Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O'Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., Kastner, M., & Moher, D. (2014). Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67 (12), 1291–1294.

Cramm, H., Smith, G., Samdup, D., Williams, A., & Ruhland, L. (2019). Navigating health care systems for military-connected children with autism spectrum disorder: a qualitative study of military families experiencing mandatory relocation. Paediatrics & Child Health, 24 (7), 478–484.

Crane, L., Batty, R., Adeyinka, H., Goddard, L., Henry, L. A., & Hill, E. L. (2018). Autism diagnosis in the United Kingdom: Perspectives of autistic adults, parents and professionals. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 48 (11), 3761–3772.

Crane, L., Chester, J. W., Goddard, L., Henry, L. A., & Hill, E. (2016). Experiences of autism diagnosis: a survey of over 1000 parents in the United Kingdom. Autism, 20 (2), 153–162.

Dababnah, S., & Bulson, K. (2015). “On the Sidelines”: access to autism-related services in the West Bank. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45 (12), 4124–4134.

Dababnah, S., Shaia, W. E., Campion, K., & Nichols, H. M. (2018). “We had to keep pushing”: caregivers’ perspectives on autism screening and referral practices of black children in primary care. Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities, 56 (5), 321–336.

Daniels, A., Como, A., Herguner, S., Kostadinova, K., Stosic, J., & Shih, A. (2017). Autism in southeast Europe: a survey of caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 47 (8), 2314–2325.

de Alba, M. J. G., & Bodfish, J. W. (2011). Addressing parental concerns at the initial diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5 (1), 633–639.

de Verdier, K., Fernell, E., & Ek, U. (2019). Blindness and autism: parents’ perspectives on diagnostic challenges, support needs and support provision. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50 (6), 1921–1930.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

DePape, A. M., & Lindsay, S. (2016). Lived experiences from the perspective of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 31 (1), 60–71.

Eggleston, M. J. F., Thabrew, H., Frampton, C. M. A., Eggleston, K. H. F., & Hennig, S. C. (2019). Obtaining an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis and supports: New Zealand parents’ experiences. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 62 , 18–25.

Elder, J. H., Brasher, S., & Alexander, B. (2016). Identifying the barriers to early diagnosis and treatment in underserved individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and their families: a qualitative study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37 (6), 412–420.

Ferguson, A., & Vigil, D. C. (2019). A comparison of the ASD experience of low-SES Hispanic and non-Hispanic White parents. Autism Research, 12 (12), 1880–1890.

Filipek, P. A., Accardo, P. J., Ashwal, S., Baranek, G. T., Cook Jr., E. H., Dawson, G., et al. (2000). Practice parameter: Screening and diagnosis of autism: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society. Neurology, 55 (4), 468–479.

Finnegan, R., Trimble, T., & Egan, J. (2014). Irish parents’ lived experience of learning about and adapting to their child's autistic spectrum disorder diagnosis and their process of telling their child about their diagnosis. The Irish Journal of Psychology, 35 (2–3), 78–90.

Gentles, S. J., Nicholas, D. B., Jack, S. M., McKibbon, K. A., & Szatmari, P. (2019). Parent engagement in autism-related care: a qualitative grounded theory study. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 7 (1), 1–18.

Goin-Kochel, R. P., Mackintosh, V. H., & Myers, B. J. (2006). How many doctors does it take to make an autism spectrum diagnosis? Autism, 10 (5), 439–451.

Gray, D. E. (2002). ‘Everybody just freezes. Everybody is just embarrassed’: felt and enacted stigma among parents of children with high functioning autism. Sociology of Health & Illness, 24 (6), 734–749.

Ha, V. S., Whittaker, A., & Rodger, S. (2017). Assessment and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in Hanoi, Vietnam. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26 (5), 1334–1344.

Hackett, L., Shaikh, S., & Theodosiou, L. (2009). Parental perceptions of the assessment of autistic spectrum disorders in a tier three service. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 14 (3), 127–132.

Hannon, M., & Hannon, L. (2017). Fathers' orientation to their children's autism diagnosis: a grounded theory study. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 47 (7), 2265–2274.

Harrington, J. W., Patrick, P. A., Edwards, K. S., & Brand, D. A. (2006). Parental beliefs about autism: Implications for the treating physician. Autism, 10 (5), 452–462.

Henderson, S. (2017). Jemma’s diagnosis. Journal of Paediatrics & Child Health, 53 (6), 605–606.

Hennel, S., Coates, C., Symeonides, C., Gulenc, A., Smith, L., Price, A. M., & Hiscock, H. (2016). Diagnosing autism: Contemporaneous surveys of parent needs and paediatric practice. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 52 (5), 506–511.

Hidalgo, N. J., McIntyre, L. L., & McWhirter, E. H. (2015). Sociodemographic differences in parental satisfaction with an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 40 (2), 147–155.

Ho, H. S., Yi, H., Griffiths, S., Chan, D. F., & Murray, S. (2014). ‘Do It Yourself’in the parent–professional partnership for the assessment and diagnosis of children with autism spectrum conditions in Hong Kong: a qualitative study. Autism, 18 (7), 832–844.

Hofer, J., Hoffmann, F., Kamp-Becker, I., Poustka, L., Roessner, V., Stroth, S., et al. (2019). Pathways to a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in Germany: a survey of parents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13 (1), 16.

Howlin, P., & Asgharian, A. (1999). The diagnosis of autism and Asperger syndrome: findings from a survey of 770 families. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 41 (12), 834–839.

Howlin, P., & Moore, A. (1997). Diagnosis in autism: a survey of over 1200 patients in the UK. Autism, 1 (2), 135–162.

Hurt, L., Langley, K., North, K., Southern, A., Copeland, L., Gillard, J., & Williams, S. (2019). Understanding and improving the care pathway for children with autism. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 32 (1), 208–223.

Hyman, S. L., Levy, S. E., & Myers, S. M. (2020). Identification, evaluation, and Management of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-3447 .

Jacobs, D., S. J, Dierickx, K., & Hens, K. (2020). Parents' views and experiences of the autism spectrum disorder diagnosis of their young child: a longitudinal interview study. European Child Adolescent Psychiatry., 29 (8), 1143–1154.

Jacobs, D., Steyaert, J., Dierickx, K., & Hens, K. (2018). Implications of an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis: an interview study of how physicians experience the diagnosis in a young child. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 7 (10), 348.

Jashar, D. T., Fein, D., Berry, L. N., Burke, J. D., Miller, L. E., Barton, M. L., & Dumont-Mathieu, T. (2019). Parental perceptions of a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation for toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 49 (5), 1763–1777.

Jegatheesan, B., Fowler, S., & Miller, P. J. (2010). From symptom recognition to services: how South Asian Muslim immigrant families navigate autism. Disability, Handicap & Society, 25 (7), 797–811.

Johnson, C. P., Myers, S. M., & American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children With Disabilities. (2007). Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 120 (5), 1183–1215.

Keok, C. A. (2012). Parental experience of having a child diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder: an integrative literature review. Singapore Nursing Journal, 39 (1), 8–18.

Google Scholar

King, S., King, G., & Rosenbaum, P. (2004). Evaluating health service delivery to children with chronic conditions and their families: development of a refined measure of processes of care (MPOC−20). Children’s Health Care, 33 (1), 35–57.

King, S., Rosenbaum, P., & King, G. (1995). The measure of processes of care: a means to assess family-centred behaviours of health care providers . Hamilton, ON: McMaster University, Neurodevelopmental Clinical Research Unit.

Lappe, M., Lau, L., Dudovitz, R. N., Nelson, B. B., Karp, E. A., & Kuo, A. A. (2018). The diagnostic odyssey of autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics, 141 , S272–S279.

Legg, H., & Tickle, A. (2019). UK parents’ experiences of their child receiving a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Autism: The International Journal of Research & Practice, 23 (8), 1897–1910.

Lloyd, S., Osborne, L. A., & Reed, P. (2019). Personal experiences disclosed by parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: a YouTube analysis. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 64 , 13–22.

Lopez, K., Xu, Y., Magana, S., & Guzman, J. (2018). Mother’s reaction to autism diagnosis: a qualitative analysis comparing Latino and White parents. Journal of Rehabilitation, 84 (1), 41–50.

Lovelace, T. S., Robertson, R. E., & Tamayo, S. (2018). Experiences of African American mothers of sons with autism spectrum disorder: lessons for improving service delivery. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 53 (1), 3–16.

Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Baio, J., et al. (2020). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years — autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report . https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1 .

Mahapatra, P., Pati, S., Sinha, R., Chauhan, A. S., Nanda, R. R., & Nallala, S. (2019). Parental care-seeking pathway and challenges for autistic spectrum disorders children: a mixed method study from Bhubaneswar, Odisha. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 61 (1), 37–44.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mansell, W., & Morris, K. (2004). A survey of parents’ reactions to the diagnosis of an autistic spectrum disorder by a local service: access to information and use of services. Autism, 8 (4), 387–407.

Martinez, M., Thomas, K. C., Williams, C. S., Christian, R., Crais, E., Pretzel, R., et al. (2018). Family experiences with the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: system barriers and facilitators of efficient diagnosis. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 48 (7), 2368–2378.

Mitchell, C., & Holdt, N. (2014). The search for a timely diagnosis: parents’ experiences of their child being diagnosed with an autistic spectrum disorder. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 26 (1), 49–62.

Mockett, M., Khan, J., & Theodosiou, L. (2011). Parental perceptions of a manchester service for autistic spectrum disorders. International Journal of Family Medicine, 2011, 1–6.

Moh, T. A., & Magiati, I. (2012). Factors associated with parental stress and satisfaction during the process of diagnosis of children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6 (1), 293–303.

Molteni, P., & Maggiolini, S. (2015). Parents’ perspectives towards the diagnosis of autism: an Italian case study research. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24 (4), 1088–1096.

Mulligan, J., MacCulloch, R., Good, B., & Nicholas, D. B. (2012). Transparency, hope, and empowerment: a model for partnering with parents of a child with autism spectrum disorder at diagnosis and beyond. Social Work in Mental Health, 10 (4), 311–330.

National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. (2011). Autism: recognition, referral and diagnosis of children and young people on the autism spectrum . London, UK: RCOG Press.

Navot, N., Jorgenson, A. G., & Webb, S. J. (2017). Maternal experience raising girls with autism spectrum disorder: a qualitative study. Child: Care, Health and Development, 43 (4), 536–545.

Nilses, Ã., Jingrot, M., Linnsand, P., Gillberg, C., & Nygren, G. (2019). Experiences of immigrant parents in Sweden participating in a community assessment and intervention program for preschool children with autism. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment . https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S221908 .

Nissenbaum, M. S., Tollefson, N., & Reese, R. M. (2002). The interpretative conference: sharing a diagnosis of autism with families. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17 (1), 30–43.

Osborne, L. A., & Reed, P. (2008). Parents’ perceptions of communication with professionals during the diagnosis of autism. Autism, 12 (3), 309–324.

Oswald, D. P., Haworth, S. M., Mackenzie, B. K., & Willis, J. H. (2017). Parental report of the diagnostic process and outcome: ASD compared with other developmental disabilities. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities, 32 (2), 152–160.

Pearson, J. N., & Meadan, H. (2018). African American parents’ perceptions of diagnosis and services for children with autism. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 53 (1), 17–32.

Pearson, J. N., Meadan, H., Malone, K. M., & Martin, B. M. (2020). Parent and professional experiences supporting African-American children with autism. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 7 (2), 305–315.

Penner, M., Anagnostou, E., & Ungar, W. J. (2018). Practice patterns and determinants of wait time for autism spectrum disorder diagnosis in Canada. Molecular Autism, 9 (1), 16.

Penner, M., King, G. A., Hartman, L., Anagnostou, E., Shouldice, M., & Hepburn, C. M. (2017). Community general pediatricians’ perspectives on providing autism diagnoses in Ontario, Canada: a qualitative study. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 38, 593–602.

Perry, A., Cummings, A., Geier, J. D., Freeman, N. L., Hughes, S., Managhan, T., et al. (2011). Predictors of outcome for children receiving intensive behavioral intervention in a large, community-based program. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5 (1), 592–603.

Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13 (3), 141–146.

Potter, C. A. (2017). “I received a leaflet and that is all”: father experiences of a diagnosis of autism. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45 (2), 95–105.

Rabba, A. S., Dissanayake, C., & Barbaro, J. (2019). Parents’ experiences of an early autism diagnosis: Insights into their needs. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 66 .

Rabbitte, K., Prendeville, P., & Kinsella, W. (2017). Parents’ experiences of the diagnostic process for girls with autism spectrum disorder in Ireland: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Educational and Child Psychology, 34 , 54–66.

Randall, M., Egberts, K. J., Samtani, A., Scholten, R. J., Hooft, L., Livingstone, N., et al. (2018). Diagnostic tests for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in preschool children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7 .

Rasmussen, P. S., Pedersen, I. K., & Pagsberg, A. K. (2020). Biographical disruption or cohesion?: How parents deal with their child’s autism diagnosis. Social Science & Medicine . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112673 .

Raymond-Barker, P., Griffith, G. M., & Hastings, R. P. (2018). Biographical disruption: experiences of mothers of adults assessed for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 43 (1), 83–92.

Reddy, G., Fewster, D. L., & Gurayah, T. (2019). Parents’ voices: experiences and coping as a parent of a child with autism spectrum disorder. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 49 (1), 43–50.

Reed, P., & Osborne, L. A. (2012). Diagnostic practice and its impacts on parental health and child behaviour problems in autism spectrum disorders. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 97 (10), 927–931.

Reese, R., Jamison, R., Wendland, M., Fleming, K., Braun, M. J., Schuttler, J. O., & Turek, J. (2013). Evaluating interactive videoconferencing for assessing symptoms of autism. Telemedicine and e-Health, 19 (9), 671–677.

Renty, J., & Roeyers, H. (2006). Satisfaction with formal support and education for children with autism spectrum disorder: the voices of the parents. Child: Care, Health and Development, 32 (3), 371–385.

Rhoades, R. A., Scarpa, A., & Salley, B. (2007). The importance of physician knowledge of autism spectrum disorder: results of a parent survey. BMC Pediatrics, 7 (1), 37.

Ribeiro, S. H. B., de Paula, C. S., Bordini, D., Mari, J. J., & Caetano, S. C. (2017). Barriers to early identification of autism in Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 39 (4), 352–354.

Rivard, M., Millau, M., Magnan, C., Mello, C., & Boule, M. (2019). Snakes and ladders: barriers and facilitators experienced by immigrant families when accessing an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 31 (4), 519–539.

Rogers, C. L., Goddard, L., Hill, E. L., Henry, L. A., & Crane, L. (2016). Experiences of diagnosing autism spectrum disorder: A survey of professionals in the United Kingdom. Autism, 20, 820–831.

Russell, G., & Norwich, B. (2012). Dilemmas, diagnosis and de-stigmatization: parental perspectives on the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17 (2), 229–245.

Sacrey, L. A. R., Zwaigenbaum, L., Bryson, S., Brian, J., Smith, I. M., Roberts, W., et al. (2018). Parent and clinician agreement regarding early behavioral signs in 12-and 18-month-old infants at-risk of autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 11 (3), 539–547.

Sakai, C., Mule, C., Leclair, A., Chang, F., Sliwinski, S., Yau, Y., et al. (2019). Parent and provider perspectives on the diagnosis and management of autism in a Chinese immigrant population; 30908425. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 40 (4), 257–265.

Samadi, S. A., McConkey, R., & Kelly, G. (2012). The information and support needs of Iranian parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Early Child Development and Care, 182 (11), 1439–1453.

Sansosti, F. J., Lavik, K. B., & Sansosti, J. M. (2012). Family experiences through the autism diagnostic process. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 27 (2), 81–92.

Sardell, A. N., & Trierweiler, S. J. (1993). Disclosing the cancer diagnosis. Procedures that influence patient hopefulness. Cancer, 72 (11), 3355–3365.

Schelly, D., González, P. J., & Solís, P. J. (2019). Barriers to an information effect on diagnostic disparities of autism spectrum disorder in young children. Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology . https://doi.org/10.1177/2333392819853058 .

Selimoglu, O. G., Ozdemir, S., Toret, G., & Ozkubat, U. (2013). An examination of the views of parents of children with autism about their experiences at the post-diagnosis period of autism. International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education, 5 (2).

Sharp, M. C., Strauss, R. P., & Lorch, S. C. (1992). Communicating medical bad news: parents’ experiences and preferences. The Journal of Pediatrics, 121 (4), 539–546.

Shire, S. Y., Gulsrud, A., & Kasari, C. (2016). Increasing responsive parent-child interactions and joint engagement: comparing the influence of parent-mediated intervention and parent psychoeducation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46 (5), 1737–1747.

Siklos, S., & Kerns, K. A. (2007). Assessing the diagnostic experiences of a small sample of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 28 (1), 9–22.

Sloper, P., & Turner, S. (1993). Determinants of parental satisfaction with disclosure of disability. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 35 (9), 816–825.

Smith-Young, J., Chafe, R., & Audas, R. (2020). “Managing the Wait”: parents’ experiences in accessing diagnostic and treatment services for children and adolescents diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Health services insights, 13 , 1178632920902141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632920902141 .

Sritharan, B., & Koola, M. M. (2019). Barriers faced by immigrant families of children with autism: a program to address the challenges. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 39 , 53–57.

Stahmer, A. C., Vejnoska, S., Iadarola, S., Straiton, D., Segovia, F. R., Luelmo, P., et al. (2019). Caregiver voices: cross-cultural input on improving access to autism services. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 6 (4), 752–773.

Sudhinaraset, A., & Kuo, A. (2013). Parents’ perspectives on the role of pediatricians in autism diagnosis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43 (3), 747–748.

Tait, K., Fung, F., Hu, A., Sweller, N., & Wang, W. (2016). Understanding Hong Kong Chinese families’ experiences of an autism/ASD diagnosis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46 (4), 1164–1183.

The World Bank (2019). World Bank list of economies (June 2019) [data set]. The World Bank Group. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/site-content/CLASS.xls . Accessed 25 Feb 2020.

Upoma, T. F., Moonajilin, M. S., Rahman, M. E., & Ferdous, M. Z. (2020). Mothers initial challenges having children with autism spectrum disorders in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Medical Science, 19 (2), 268–272.

Volkmar, F., Siegel, M., Woodbury-Smith, M., King, B., McCracken, J., State, M., et al. (2014). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53 (2), 237–257.

Whitehouse, A. J. O., Evans, K., Eapen, V., & Wray, J. (2018). A national guideline for the assessment and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in Australia . Brisbane, Australia: Autism Cooperative Research Centre (CRC).

Wiley, S., Gustafson, S., & Rozniak, J. (2014). Needs of parents of children who are deaf/hard of hearing with autism spectrum disorder. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 19 (1), 40–49.

Wong, V., Yu, Y., Keyes, M. L., & McGrew, J. H. (2017). Pre-diagnostic and diagnostic stages of autism spectrum disorder: a parent perspective. Child Care in Practice, 23 (2), 195–217.

Woodside, J. M., Rosenbaum, P. L., King, S. M., & King, G. A. (2001). Family-centered service: developing and validating a self-assessment tool for pediatric service providers. Children’s Health Care, 30 (3), 237–252.

Yi, H., Siu, Q., Ngan, O., & Chan, D. (2020). Parents’ experiences of screening, diagnosis, and intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90 (3), 297–311.

Zarafshan, H., Mohammadi, M. R., Abolhassani, F., Motevalian, S. A., Sepasi, N., & Sharifi, V. (2019). Current status of health and social services for children with autism in Iran: parents’ perspectives. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 14 (1), 76–83.

Zeleke, W. A., Hughes, T., & Chitiyo, M. (2018). The path to an autism spectrum disorders diagnosis in Ethiopia: parent perspective; 28816489. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88 (3), 316–327.

Zuckerman, K. E., Lindly, O. J., Reyes, N. M., Chavez, A. E., Macias, K., & Smith, K. N. (2017). Disparities in diagnosis and treatment of autism in Latino and non-Latino White families. Pediatrics, 139 (5), 1–10.

Zuckerman, K. E., Sinche, B., Mejia, A., Cobian, M., Becker, T., & Nicolaidis, C. (2014). Latino parents’ perspectives on barriers to autism diagnosis. Academic Pediatrics, 14 (3), 301–308.

Zwaigenbaum, L., & Penner, M. (2018). Autism spectrum disorder: advances in diagnosis and evaluation. BMJ, 361 , k1674.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jesiqua Rapley for her help with formatting the paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Bloorview Research Institute, 150 Kilgour Road, Toronto, ON, M4G 1R8, Canada

Amber Makino, Laura Hartman, Gillian King & Melanie Penner

Department of Paediatrics, University of Toronto, 555 University Ave, Toronto, ON, M5G 1X8, Canada

Amber Makino & Melanie Penner

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, 150 Kilgour Road, Toronto, ON, M4G 1R8, Canada

Amber Makino, Pui Ying Wong & Melanie Penner

Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, University of Toronto, 555 University Ave, Toronto, ON, M5G 1X8, Canada

Laura Hartman & Gillian King

Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, 155 College St 4th Floor, Toronto, ON, M5T 3M6, Canada

Melanie Penner

Institute of Medical Sciences, University of Toronto, 1 King’s College Circle, Toronto, ON, M5S 1A8, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AM conceived and designed review, assessed all articles for inclusion, interpreted results, and drafted the manuscript; MP conceived the review, participated in the design of review, assessed all articles for inclusion, and helped draft the manuscript; LH helped conceive the review; GK helped conceive the review; PYW participated in design of review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Amber Makino .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

Melanie Penner has received funding from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Canadian Federal Government, and Autism Speaks. She has also received an honorarium for consulting with Addis & Associates (who were contracted by Roche). The other authors have no conflicts to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Makino, A., Hartman, L., King, G. et al. Parent Experiences of Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis: a Scoping Review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 8 , 267–284 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-021-00237-y

Download citation

Received : 13 September 2019

Accepted : 11 January 2021

Published : 16 February 2021

Issue Date : September 2021