An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Family Matters: Research on Family Ties and Health, 2010-2020

Debra umberson.

Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin, 305 E 23 rd Street, Austin TX

Mieke Beth Thomeer

Department of Sociology, University of Alabama at Birmingham

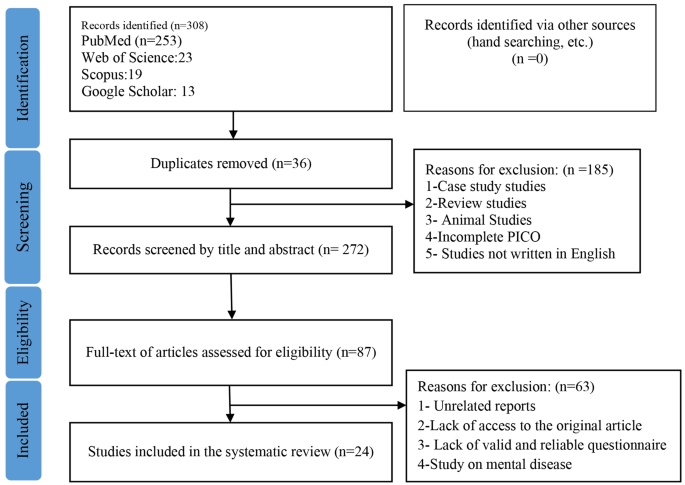

Family ties have wide-ranging consequences for health, for better and for worse. This decade review uses a life course perspective to frame significant advances in research on the effects of family structure and transitions (e.g., marital status), and family dynamics and quality (e.g., emotional support from family members), on health across the life course. Significant advances include the linking of childhood family experiences to health at older ages, identification of biosocial processes that explain how family ties influence health throughout life, research on social contagion showing how family members influence one another’s health, and attention to diversity in family and health dynamics, including gender, sexuality, socioeconomic, and racial diversity. Significant innovations in methods include dyadic and family-level analysis and causal inference strategies. The review concludes by identifying directions for future research on families and health, advocating for a “family biography” framework to guide future research, and calling for more research specifically designed to assess policies that affect families and their health from childhood into later life.

Parents, children, intimate partners, and other family members have the power to improve—or undermine—health. Recent advances in research on family ties and health, built on increasingly sophisticated data and innovative methods, examine variation in these linkages across demographic and social contexts. These studies identify the specific and intersecting biosocial pathways through which family ties influence health in ways that sometimes vary by social position. Through these pathways, family ties exert both short- and long-term effects on health from childhood through later life. In this review, we highlight key themes and advances in the past decade of research on families and health.

We use a life course framework ( Elder, Johnson & Crosnoe, 2003 ) to organize this review. Research on family ties and health tends to fall into two camps: one focusing on health in childhood and the other focusing on health in adulthood. A life course perspective helps synthesize these literatures by emphasizing the inextricable links between these life stages. The life course concepts of cumulative advantage and disadvantage and stress proliferation help scholars show how social contexts and resources in childhood matter for health and well-being at older ages. A life course perspective highlights “linked lives” across life stages, the importance of early family experiences for lifelong health, and the significance of family ties and transitions throughout adulthood for health trajectories. No single theoretical paradigm dominates research of the past decade; however, a consistent theoretical strand across studies is attention to stress (either imposed on families or arising within families) and the associated accumulation of advantage or disadvantage in health through intersecting biological, psychological, and social pathways.

In this review, we focus on relationships with parents in childhood and relationships with intimate partners in adulthood, reflecting the primary areas of research on family ties and health over the past decade. We recognize the importance of other family ties, including children, siblings, and grandparents, but a detailed analysis of these areas is beyond the scope of this review and is addressed in other articles in this volume (see MS#6776, 2020 ; MS#6759, 2020 ). Life course approaches further emphasize the importance of social position—as patterned by gender and sexuality, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic status—in shaping family ties and life course experiences that influence health. Social position matters in at least two important ways. First, some groups are exposed to more adverse family circumstances (e.g., higher rates of incarceration among minority families, lack of access to marriage for same-sex couples historically). Second, the effects of family circumstances on health may vary by social position (e.g., gender differences in effects of relationship stress on health). We call attention to such diversity throughout this review while recognizing that the complexity associated with each of these systems of stratification warrants fuller discussion than we can provide.

An exciting advance in research has been growing theoretical and empirical sophistication in clarifying the intersecting biosocial pathways through which family ties and social conditions influence health ( Repetti, Robles, & Reynolds, 2011 ). The increasing availability of quality biomarker data (i.e., medical indicators that can be measured objectively, accurately, and reproducibly, such as blood pressure and C-reactive protein) has yielded significant insights into how and when families impact health, even prior to any specific diagnosis. This work emphasizes the effect of family stress on physiological systems: for example, family stress activates cardiovascular arousal and inflammatory and immune responses that undermine health in childhood and have the potential to increase chronic disease risk with advancing age (see a review in Miller, Chen, & Parker 2011 ).

In this review, we focus first on family ties and child health and then on family ties and health in adulthood. We address the broad themes of: (a) family structure and transitions (e.g., marital status, divorce) and (b) family relationship quality and dynamics (e.g., emotional support and conflict in family ties). We then turn to innovations in data and methods that undergird research advances over the past ten years. In conclusion, we identify significant directions for future research and emphasize the critical value of this research for informing policies that affect families and their health.

Families and Child/Adolescent Health

A significant theoretical advance over the past decade has been the placement of research on family ties’ consequences for child health squarely within a life course perspective. This research has shown that family experiences early in the life course have the potential to launch trajectories of mental and physical health that extend beyond childhood (e.g., Gaydosh & Harris, 2018 ). Whereas past research on childhood tended to “stay in childhood,” life course scholarship shows that childhood experiences shape the accumulation of health-related advantage or disadvantage throughout life ( Avison, 2010 ). For example, exposure to social resources in childhood can add to cumulative advantage in health over time. For children, family contexts and relationships are the starting point of early-life exposure to both stress and resources, with implications for both later-life family relationships and later-life health ( Umberson et al., 2014 ). We first focus on recent work that considers family stress in relation to the health of children and adolescents and then turn to family resources that may protect children’s health. We conclude by discussing the impact of stressful family conditions in childhood on health in adulthood.

Childhood and the Stress Universe

The past decade of research on children’s health has advanced the perspective that family (structure) instability, stressful family dynamics, and family social position are inextricably linked. A key life course concept is stress proliferation—the idea that stressors often occur in tandem and one stressor triggers another, leading to a pileup of stressors that can be emotionally and physically overwhelming ( Pearlin et al. 2005 ). Avison (2010) has called for more attention to the “stress universe” of children, including family stress. Before turning to recent research that sheds light on major childhood family stressors that contribute to child health, we briefly describe how child health is typically assessed and discuss recent research on the pathways that link family stress to child health.

Child Health Measures

In the following review, we define health broadly. Most studies of children and adolescents focus on internalizing and externalizing symptoms as indicators of health and well-being. Internalizing symptoms include bodily complaints, social withdrawal, depression, and anxiety; externalizing symptoms include delinquent and aggressive behaviors. These measures typically rely on parent reports for younger children and self-reports for older children and adolescents, but some studies also consider reports from teachers (e.g., Early Childhood Longitudinal Study; https://nces.ed.gov/ecls/ ). The focus on emotional and behavioral symptoms reflects current concerns about mental health in the early life course; about 21 percent of children aged 2 to 17 have a diagnosed behavioral or psychological condition, and trend data indicate increasing rates of depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among youth ( The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2016 ). There have also been sharp rises in childhood obesity, asthma, bronchitis, and hay fever ( Delaney & Smith, 2012 ), and much of the influential research on childhood family environments and health focuses on these outcomes (e.g., Bair-Merritt, et al, 2015 ; Schreier & Chen, 2013 ).

Family Structure and Instability

Research on children and families focuses on varying levels of stability and stress within families as a major influence on children’s health. Overall, studies suggest that children of married parents have better mental and physical health than children of cohabiting parents ( Cavanagh & Fomby, 2019 ). The key explanation for this finding is the tendency of married couples’ families to feature less instability (i.e., disruption and change in family structure); instability contributes to parenting strain and distress, creates new economic strains, and disrupts children’s ongoing family relationships and routines. These strains and disruptions result in increasing stress for children, especially when there are multiple family transitions (e.g., parental divorce, re-partnering and remarriage, new half-siblings, and step-families; Lee & McLanahan, 2015 ), and this increasing stress reduces children’s health and well-being ( Cavanagh & Fomby, 2019 ).

However, recent work suggests two caveats regarding family instability. First, stability can be found in nontraditional family structures. For example, Reczek and colleagues (2016b) show that children’s health benefits from living with married same-sex as well as different-sex parents but that cohabiting parents (whether in same- or different-sex unions) do not provide the same health benefits because cohabiting unions tend to be less stable (e.g., more likely to dissolve). Second, the growing literature on family instability points to the need to clarify predictive and mediating factors that make family instability more (or less) harmful for children’s health. Fomby and Osborne (2017) emphasize the importance of family-level stressors in mediating the impact of both family instability and parents’ multi-partner fertility on children’s externalizing behavior. Also important is the timing of events and stress levels both preceding and following those events. For example, a father’s departure from the home seems to have less impact on adolescent delinquency if the departure occurs earlier in childhood ( Markowitz & Ryan, 2016 ). We need more work on the complex interrelationships between associated stressors, mediating factors, and timing of the family transitions that put children at risk, as well as protective factors that promote children’s resilience and health.

Growing evidence suggests that family transitions and instability characterized by the loss of a family member are particularly damaging to children. Stable attachment to family members is essential to child development and well-being, and loss may be a uniquely traumatic stressor. The death of a parent in childhood or adolescence has adverse effects on health that last into young adulthood ( Amato & Anthony, 2014 ; Gaydosh & Harris, 2018 ), and other studies show that early parental death increases health and mortality risk even into mid- and later life ( Guldin, 2015 ). Given the extent of mass incarceration in the United States, some of the most significant research of the past decade has addressed the impact of parental incarceration , another type of parent loss, on children’s health and well-being (e.g., Turney, 2014 ). Children of incarcerated parents are embedded in a dense constellation of risk associated with disadvantage before the parent’s incarceration, disadvantage associated with losing access to a parent, and stress proliferation that results from having an incarcerated parent ( Wakefield & Uggen, 2010 ). Much like incarceration, immigration status has taken on greater significance in the United States as family separation has become a greater threat to children ( Landale et al., 2015 ). Family separation due to military deployments has also been negatively linked to child health ( Paley, Lester, & Mogil, 2013 ). Notably, race, ethnicity, and social class are associated with the risk of parental loss through death ( Umberson, 2017 ), incarceration ( Wakefield & Uggen, 2010 ), and immigration policies ( Landale et al., 2015 ). Given the clear importance of family stability for children, future research should identify the mechanisms through which family separation and loss affect child health, sources of resilience, and later health into and throughout adulthood.

Parent Characteristics and Family Stress

Recent research has advanced understanding of how stress and health spread between family members and has directed attention to stressful family dynamics for children associated with parents’ financial resources, health problems, relationship problems, and aggression. Inadequate financial resources are a major source of children’s stress, and financial strain and poverty contribute to family instability and many of the specific family stressors described below. Child poverty rates have remained high (about 20 percent) since the 1970s ( Chaudry & Wimer 2016 ). Children in families of lower socioeconomic status are in poorer health for many reasons, including having more stressed/distressed parents and caregivers, more chaotic family routines, more conflict in family relationships, greater family embeddedness in poor neighborhoods and schools, and significantly higher levels of family instability ( Raver, Roy and Pressler 2015 )—all sources of childhood stress. Family socioeconomic status operates through multiple pathways to influence children’s health behaviors, psychological states, and physiological processes; low socioeconomic status undermines health by decreasing access to helpful resources while increasing exposure to harmful stressors ( Schreier & Chen, 2013 ).

Parents’ poor health, which often co-occurs with poverty ( Hardie & Landale, 2013 ), also has a negative impact on children’s health, indicating that these should be studied together and in relation to family instability in order to best assess risk to children’s health. Most studies of parental health problems have focused on the negative impact of mothers’ depression and have shown that the effect on child health is mediated by family instability and financial stress ( Turney, 2011 ). But parents’ physical health and health behaviors also matter for children’s health, sometimes through reciprocal pathways; for example, one study found that a parent’s drinking was associated with child and adolescent externalizing behaviors, which in turn exacerbated the parent’s drinking ( Zebrak & Green, 2016 ; see review in Shreier & Chen, 2013 ). Mothers’ health limitations may matter more for children’s well-being than father’s health limitations, and the life course timing of parental health problems may also contribute to heterogeneity in children’s responses; for example, Hardie and Turney (2017) consider children up to age nine and find that parental health problems have a greater impact when they occur in middle childhood than at older or younger ages.

Recent research on why divorce appears to negatively affect children’s well-being indicates that harmful effects on children are better explained by parents’ strained relationship dynamics, mental health problems, and lower socioeconomic status (all of which contribute to the risk of divorce) prior to divorce than by the divorce event itself ( Amato & Anthony, 2014 ). Parents’ relationship quality is dynamic, and the timing, persistence, and trajectory of parents’ relationship problems clearly matter for children’s well-being. For example, Bair-Merritt and colleagues (2015) link mothers’ exposure to intimate partner violence to their children’s cortisol reactivity and asthma problems. Marital conflict is especially detrimental for children’s externalizing behaviors if conflict is frequent and escalating ( Madigan, Plamondon, & Jenkins, 2016 ). Future research should identify other pre–family transition factors that protect children’s health or increase vulnerability following family transitions.

A substantial literature shows that child neglect and abuse activate biosocial processes that take a lasting toll on health, and numerous studies over the past decade have gone further to show that parents’ more routine patterns of hostility and aggression also affect children (see MS#6811, 2020 ; MS#6755, 2020 for more detailed discussion of this point). Miller and Chen (2010 : 854) find that “even mild exposure to a risky family in early life can shift the developmental trajectory toward a proinflammatory phenotype” evident in adolescence. There is also a growing consensus that spanking, widely used as a form of discipline by parents, is a significant stressor in the lives of children, with adverse short- and long-term effects on health and well-being that are consistent across social and cultural contexts ( Gershoff et al., 2018 ).

Family Resources for Children

The focus of most research has been on family factors that create disadvantages for children’s health, but several research themes identify ways that families protect children’s health. First, family practices that promote stability and routine and minimize physical punishment ( Cavanagh & Fomby, 2019 ; Gershoff et al., 2018 ; Schreirer & Chen, 2013 ) can benefit youth. Second, parents’ good health reduces the stress of parenting and contributes to family stability ( Hardie & Turney, 2017 ). Third, close and cohesive family relationships protect children and adolescents ( Maimon, Browning, & Brooks-Gunn, 2010 ). On this last point, emerging research suggests that parental support can mitigate stress for children and adolescents at high risk due to discrimination based on race ( Benner, et al., 2018 ), sexual orientation or gender identity ( Thomeer, Paine, & Bryant, 2018 ), and immigration status ( Mood, Jonsson, & Låftman, 2016 ). Additionally, close relationships with siblings may protect adolescents from family stress ( Waite et al., 2011 ). Future research should expand understanding of family contexts that protect children’s health and how these resources are unequally distributed in the population (e.g., by socioeconomic status).

Family financial resources are highly correlated with many other family resources that benefit youth (e.g., parents’ mental and physical health, safe neighborhoods), and it is possible that the key intervention to improve child well-being is to improve parents’ financial resources ( MS#6827, 2020 ). Critiques of policy programs that seek to improve children’s health and well-being by improving parents’ marital quality point out that the more effective path to improving both parents’ relationships and children’s health is to lift children out of poverty ( Turney, 2011 ). Financial resources may also alleviate parental stress and promote family stability, rendering these protective family factors more accessible. Financial resources further reduce family members’ risk of incarceration and death, both of which are highly stressful for youth. A family’s financial resources can mitigate the effects of stress on children and add to their cumulative advantage in mental and physical health beyond childhood ( Schreier & Chen, 2013 ).

The Long Arm of Family Ties in Childhood

In line with a cumulative disadvantage perspective, childhood family ties have consequences for health in adulthood. This occurs in part because stressful family environments in childhood activate physiological (e.g., cardiovascular reactivity), psychological (e.g., emotional reactivity), behavioral (e.g., self-medication with drugs, alcohol), and social (e.g., educational attainment) processes that affect health both directly and indirectly by increasing the risk of social isolation and relationship strain and instability throughout life ( Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011 ; Repetti, Robles, & Reynolds, 2011 ). When activated early in life, these intersecting processes influence lifelong patterns in family relationships and psychological and physiological systems, which in turn create an increasing disadvantage for health ( Umberson et al., 2014 ).

In particular, studies using biomarkers provide a way to examine the same outcome at different stages of the life course, which makes it possible to unpack how family ties and health are linked as people age. There are theoretical reasons to expect family structures and processes to affect health differently at different ages, and researchers should assess these measures over time, and develop theories of why we might see this variation. For example, some family dynamics may be more important for health in the early life course (e.g., due to sensitive periods of development in childhood), whereas others may be more important in later life (e.g., as individuals become more physically fragile or vulnerable). These details are essential to understanding how early-life family experiences affect mid- to later life health disparities. Researchers have increasingly asked how family ties in childhood matter for health at older ages (e.g., Umberson et al., 2014 ), but most studies of connections between family relationships and health in adulthood continue to exclude discussion of the health impact of early life family ties. Future research can fill this gap by addressing these key life course linkages.

Family Ties and Adult Health

In the following discussion of family ties and health in adulthood, we describe advances in research on union status/transitions and health in adulthood, partner dynamics and intersecting pathways that affect health, and intertwined union status/parental status trajectories over the life course.

Union Status, Union Transitions, and Health

Decades of research have addressed the link between intimate partnership status and health. Over time, although the quality of data and methods has improved and research better reflects the diversity of people’s relationships and their movement in and out of these relationships, many basic findings regarding union status and health remain unchanged. The preponderance of the evidence suggests that the married are in better health than the unmarried, cohabitors are in better health than the unmarried but worse than the married, and men benefit from marriage more than women do ( Rendall et al., 2011 ). There are two primary explanations for these patterns. First, through selection, people who are healthier and wealthier are more likely to marry and remain married, making it appear that marriage benefits health when it is actually health that predicts marriage ( Tumin & Zhang, 2018 ). Second, the married enjoy certain resources that promote health, including pooled economic assets, greater access to emotional and social support, and the spouse’s encouragement and coercion of healthy behaviors (i.e., social control; Rendall et al., 2011 ). While the never married and cohabitors may have fewer of these resources, transitions out of marriage through divorce or widowhood are especially detrimental to health, because these transitions trigger a wide array of new stressors and diminished resources that combine to undermine health and well-being ( Dupre, 2016 ; Roelfs, 2012 ).

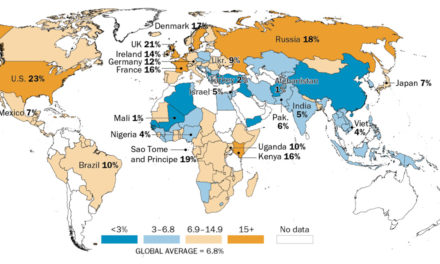

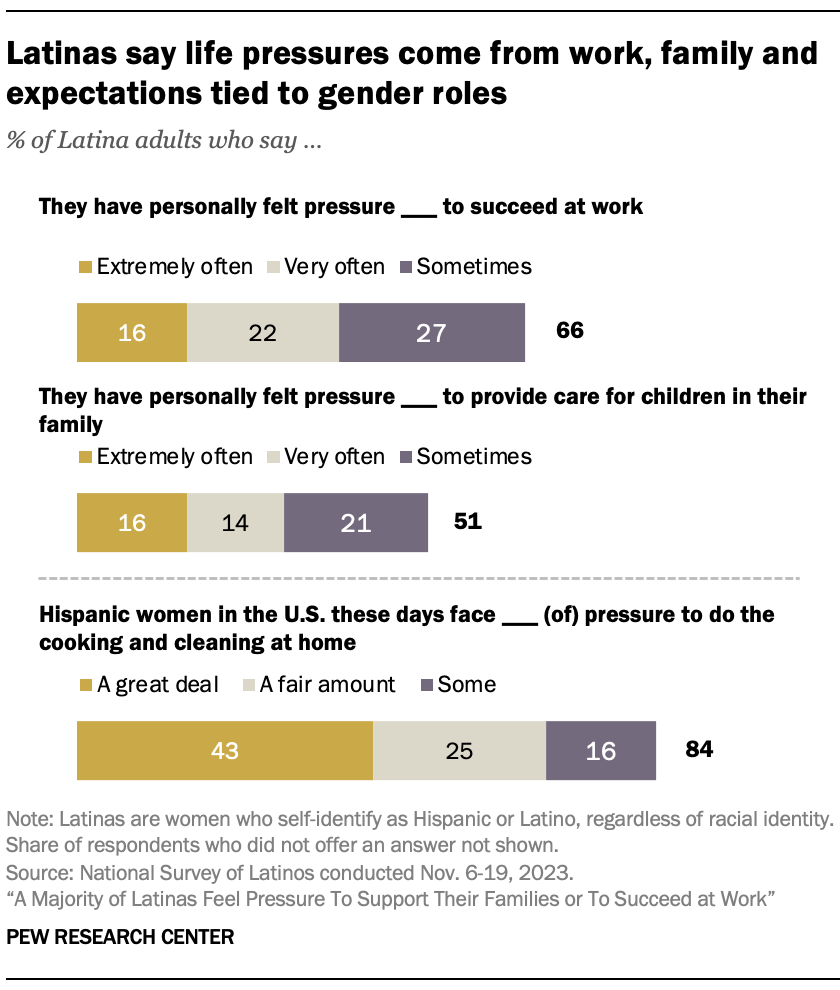

Men seem to benefit more than women from marriage because women typically provide more emotional support, social control of health behaviors, and caregiving to their spouses than men do; in addition to lower benefits, women may experience more costs associated with their relatively high levels of care work ( Glauber & Day, 2018 ). Health disparities by relationship status may be greater for those with higher household incomes and more educational attainment than for their lower-income and less educated peers ( Roxburgh, 2014 ). Such disparities may also be greater for white adults than black adults ( Roxburgh, 2014 ); for example, Dupre (2016) found that divorced white adults have a much higher risk of stroke than married white adults but found no difference between married and divorced black adults. More research is needed to unpack how and why the benefits of marriage and costs of dissolution vary by race, gender, class, and other sociodemographic factors.

Research over the past decade has innovated in two key areas concerning union status/transitions and health. First, this work has gone beyond the traditional focus on heterosexual relationships to include same-sex couples, leading to new ways of thinking about gendered dynamics within relationships. Second, scholars increasingly recognize that health is the outcome of accumulated experiences, including the unique relationship biographies that individuals form over the course of their lives. These biographies may include intertwined intimate relationship and parenting histories, as well as longer periods of singleness and social isolation, both of which may vary by systems of social stratification.

Same-sex Unions

An explosion of research over the past decade has focused on same-sex unions and health. In a significant historical shift, the United States extended constitutional protection for marriage equality in 2015, with proponents of this expansion arguing that same-sex marriage recognition could improve the health of sexual minority adults and their children and that restriction from marriage was discriminatory and negatively impacted health. MS#6668’s article in this issue provides a comprehensive overview of LGBTQ families (see also Thomeer, Paine, & Bryant, 2018 ); here, we briefly highlight findings related to same-sex union status and health. Theoretical work on minority stress and gender-as-relational perspectives undergirds much of the influential research in this area. Minority stress theory points to the unique stressors and stigma associated with sexual minority status ( LeBlanc, Frost, & Bowen, 2018 ), and gender-as-relational perspectives emphasize the different patterns that men’s and women’s partner interactions follow depending on whether they are in a same- or different-sex union ( Umberson et al., 2016 ).

Some of the first evidence to rely on nationally representative data emerged in 2013, when two studies concluded that same-sex cohabiting couples’ health is worse than different-sex married couples’ but better than that of unpartnered adults, and that same-sex and different-sex cohabitors report similar levels of health once socioeconomic status is taken into account ( Denney, Gorman, & Barrera, 2013 ; Liu, Reczek, & Brown, 2013 ). Although few studies have compared same-sex married couples to same-sex cohabiting couples, research suggests that greater legal recognition (i.e., marriages, civil unions, and registered domestic partnerships versus no legal status) is associated with better health and that same- and different-sex couples receive similar health benefits from marriage ( LeBlanc, Frost, & Bowen 2018 ; Reczek et al., 2016b ).

Notably, because most large-scale data collections have included only heterosexual couples, these prior studies on same-sex marriage have had to rely on cross-sectional data and smaller samples. Longitudinal data on same-sex couples is needed to better assess the long-term impact of marriage access on both overall health and health disparities. Future research should also focus on how these experiences may differ by class, race/ethnicity, and sexual identities beyond the heterosexual and gay/lesbian dichotomy (e.g., bisexual people). Gender differences have been a major theme of past research on union status and health for different-sex couples, and gendered patterns in relationships may unfold differently depending on whether one has a same- or different-sex partner. For example, compared to men, women in both same- and different-sex unions provide more care to a spouse during serious illness, but this care work is much more likely to be reciprocated and appreciated when women are in same-sex unions ( Umberson, et al., 2016 ). Given the current political environment, continued discrimination, and the disadvantage that the privileging of marriage may create for single adults, marriage’s availability to same-sex couples does not automatically translate into improved health for members of diverse sexual minority populations ( Thomeer, et al., 2018 ).

Transgender and gender-nonconforming partners.

Over the next decade, family scholars should consider relationship status and health for couples in which at least one partner is transgender or gender nonconforming, including variations by class, race, and ethnicity. Current research in this area is limited: most studies have focused on transgender men partnered with cisgender women and have relied on cross-sectional, non-probability samples. Despite these limitations, emerging evidence shows that an intimate partner relationship is a source of social support that can reduce perceived levels of discrimination for transgender people ( Liu & Wilkinson, 2017 ; Pfeffer, 2016 ), suggesting potential health benefits, although this remains to be tested. Moving outside the gender binary will provide new opportunities for understanding gendered health dynamics across intimate partnerships.

Marital Biography, Singleness, and Absence of Family Ties

Relationship histories are becoming increasingly complex as adults live longer, are less likely to marry and more likely to marry later, spend fewer years married, experience remarriages and stepfamilies, cohabit rather than marry, and express more sexual and gender fluidity as norms and stigma around sexual and gender identity shift (see MS#6668, 2020 and MS#6760, 2020 this issue). At the same time, research has documented the accumulation of health benefits and risks over the life course. One advance of the past decade is research on how complex marital biographies—with variability in number, duration, type, and timing of unions and transitions—shape later health. For example, Reczek and colleagues (2016a) analyzed dyadic longitudinal data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS; http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/ ) to look at individual- and couple-level trajectories of heavy alcohol use in relation to personal histories of marital status and transitions. Marriage and remarriage were associated with less drinking from mid- to later life for men but not women, and divorce increased men’s heavy drinking while leading women to drink less.

A marital biography focus also advances understanding of how time spent unpartnered shapes health. This research has focused on divorce and widowhood and has found that years spent divorced or widowed add to subsequent health risk whereas years spent married are protective ( McFarland, Hayward, & Brown, 2013 ). Moreover, there may be race and other population group differences in these patterns; Dupre (2016) found that stroke risk was increased more for white than black respondents with a history of marital dissolution. Marital biography studies have primarily addressed transitions in and out of marriage, but recent evidence points to the importance of other types of unions by showing that cohabitation breakups can affect health similarly to divorce ( Kamp Dush, 2013 ). The health effects of periods of social isolation and lack of family ties are also important features of a marital biography and need more attention in future research.

A life course approach emphasizes the linked lives of family members beyond the marital relationship. Studies using a relationship biography approach have innovated by studying the interdependent effects of parenthood and partnership histories on health. For example, Williams and colleagues (2011) found that women who were unmarried at the time of their first birth experienced worse health, more chronic disease, and higher mortality risk by age 40, yet this effect was attenuated for white women (but not black women) who eventually married and remained married to the child’s father. Future research should weave together the different strands of family biographies that coalesce to uniquely shape health, perhaps differently for different groups.

Loss of family ties may contribute to racial disparities in family and health disadvantage. Black Americans are more likely than white Americans to experience the death of a child, sibling, parent, and spouse over their lifetime and to experience these losses earlier in the life course, potentially adding to social isolation, caregiving burdens, strains within families, and cumulative disadvantage in health ( Umberson, 2017 ). Mass incarceration and current immigration policies also sever family ties and increase social isolation; these experiences affect health and are disproportionately common for racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. ( MS#6752, 2020 ; Wakefield & Uggen, 2010 ). Family scholars should identify who is most likely to lack and lose family ties, the duration of and reasons for socially isolated periods of the life course, the extent of loneliness in relation to social isolation, and variations in these experiences’ consequences for health across and within diverse socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic communities.

Relationship Processes and Adult Health

Research over the past decade has illuminated the processes through which family ties affect adults’ health by highlighting the dynamics and quality of adults’ intimate partnerships. We call attention to innovation in two main aspects of the relationship between health and the dynamics and quality of social ties: (a) the impact of relationship quality (e.g., strain, support) on health, and (b) the role of social contagion (i.e., the spread of health across individuals within social networks).

Relationship Quality

Recent research shows that the quality of an intimate relationship can affect health more than marital status per se ( Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2013 ). Over the past decade, family scholars have expanded understanding of how relationship quality matters for health by taking advantage of longitudinal and dyadic data, including biomarkers as mediators and outcomes, and innovating methodologically to identify key mechanisms linking relationship quality to health. Longitudinal data have made it possible to draw on multiple waves of data collection covering twenty or more years. This research has made significant advances by demonstrating that changes in marital quality are related to changes in health over time and that this link is likely causal as well as bidirectional ( Robles et al., 2014 ). These studies show that marital quality is more salient for health at older ages than at younger ages and that negative marital interactions (e.g., conflict, demands) have stronger effects on health than do positive interactions (e.g., support, closeness; Miller et al. 2013 ). The growing availability of longitudinal data that follow individuals and couples over decades will provide rich opportunities for research over the next decade. For example, the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health Study (Add Health; https://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth ) began collecting data from children when they were in grades 7–12 in 1994–95, and they have continued data collection since then, providing unique opportunities to study health and family relationships starting in adolescence and aging into midlife. The collection of longitudinal data is difficult, given that it takes many decades before data can be analyzed; alternative strategies include cohort studies (e.g., multiple age cohorts followed over shorter periods of time).

Like research on families and childhood health, research on the biological pathways through which relationships impact adult health has advanced significantly over the past decade ( Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, 2017 ). This research has shown how multiple dimensions of relationship quality (e.g., strain, support, closeness, satisfaction) shape biomarkers. For example, recent studies find that relationship quality is inversely associated with inflammation across multiple markers (e.g., interleukin‐6 and C‐reactive protein; Bajaj, et al., 2016 ). Biomarkers reveal complex and interrelated physiological responses to marital dynamics and suggest that women’s physiological responses to marital stress are stronger than men’s ( Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, 2017 ).

Relationship quality studies have also benefited from dyadic data that has made it possible to analyze the perspectives and experiences of both members of a couple. Dyadic studies allow researchers to identify how gender operates within intimate relationships and better test theories related to “his and hers” marriages in relation to each partner’s health ( Iveniuk et al. 2014 ; Thomeer, Umberson, & Pudrovska, 2013 ). Researchers are also beginning to move beyond the “his and hers” model to queer notions of intimate relationships. These studies use dyadic methods to critically examine whether the assumptions we make about relationship quality and health in heterosexual couples apply to same-sex couples ( Umberson et al., 2016 ). However, due to a lack of longitudinal and nationally representative data, dyadic studies of relationship quality in same-sex couples lags far behind research on different-sex couples—an important data challenge that needs to be addressed in the next decade.

Another important advance in studies of relationship dynamics involves social contagion—the idea that health can “spread” across relationships or “spill over” from one family member to another. Over the past decade, longitudinal studies have shown that the depressive symptoms of one spouse—especially the wife in a different-sex couple—influence the other spouses’ depressive symptoms over time (e.g., Thomeer et al., 2013 ). Similarly, health behaviors such as alcohol use and unhealthy eating can also “spread” within a couple ( Reczek et al., 2016a ); for instance, a study found that when one spouse became obese, the other spouse’s risk of obesity almost doubled over a 25-year period ( Cobb et al. 2015 ). Recent work considers how biomarkers spread within couples. For example, a recent study found that spouses have more similar gut microbiota (i.e., microbe population in the intestine) than siblings, but only if spouses report having a close relationship ( Dill-McFarland et al., 2019 ).

Health contagion between partners is due partly to assortative mating but also to shared resources, environments, and life events—including shared stressors—and mutual influence between spouses (e.g., one spouse’s mood spreading to the other spouse and vice versa; see Kiecolt-Glaser and Wilson 2017 for an overview). Future research can use longitudinal data, qualitative data, biomarker data, and mixed methods approaches to unpack the many mechanisms that help explain processes of contagion. The gut microbiotas are a key pathway through which a couples’ shared stressors, emotions, lifestyles, and routines may get “under the skin” in ways that jointly influence the couple’s health ( Kiecolt-Glaser, Wilson & Madison, 2018 ). There is also evidence of cortisol synchrony in long-term couples, such that partners’ levels of physiological arousal become linked over time—a phenomenon that has implications for both partners’ health ( Timmons, Margolin & Saxbe, 2015 ).

Advances in Data and Methods

Overall, research on families and health has generally followed the methodological innovations of relationship quality research, owing in large part to the greater availability of nationally representative longitudinal data, inclusion of biomarker data and explanatory mechanisms, and novel smaller-scale data collection efforts. We highlight three key advances: (a) biosocial processes linking family to health, (b) dyadic and family-level analysis, and (c) strategies for addressing selection and causal inference. We also identify areas for future research.

Biosocial Mechanisms Linking Family to Health

Research over the past decade has made important contributions to understanding the mechanisms through which family structures and dynamics are related to health throughout the life course. These innovations have progressed in large part due to increased commitments to interdisciplinary partnerships and collection of biomarker data in large-scale and longitudinal datasets. Advances in data and analysis of biosocial mechanisms has been especially influential in clarifying how physiological functioning is impacted by social conditions (e.g., family structures and dynamics) in ways that impact health. Even studies that do not explicitly discuss these biosocial pathways often build their arguments on an understanding that family experiences somehow “get under the skin” to shape both specific health outcomes and overall health. For example, family stress is theorized to increase a person’s allostatic load (i.e., cumulative “wear and tear” on the body across multiple health systems including immune, cardiovascular, and metabolic systems), thus contributing to symptoms across multiple health domains ( Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011 ; Repetti, Robles, & Reynolds, 2011 ). Our understanding has benefited from the inclusion of biomarkers within study designs, especially longitudinal designs with repeated measures of specific biomarkers. Yet few studies that consider biomarkers theorize about why family ties would affect some biomarkers but not others.

A theoretically driven selection of biomarkers and other specific health outcomes will provide new insights into the complex and intersecting behavioral, psychological, social, and biological mechanisms through which families matter for health from childhood through later life. Inclusion of multiple biomarkers and health outcomes allows for a more robust understanding of how family ties affect overall health and especially how these outcomes might be connected to one another or cluster together ( Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, 2017 ; Repetti, Robles, & Reynolds, 2011 ). Future research should seek to disentangle the complex interconnections among the multiple pathways that are most predictive of specific health outcomes and identify how these interconnections vary depending on social contexts and genetic vulnerabilities.

Dyadic and Family-Level Analysis

Carr and Springer (2010) called for more dyadic and family-level data to address the failure of individual-level data “to capture the complexities of family life, including the possibility that two romantic partners, siblings, or co-parents experience their relationship (and the health consequences thereof) in starkly different ways” (p. 755). Dyadic, family-level analysis has advanced significantly over the past decade and has been featured in more than fifty studies in JMF alone. Dyadic and family-level methods allow researchers to more effectively study linked lives over the life course. For example, studies of sexual behavior such as condom use and oral sex that rely on dyadic data (e.g., Cordero-Coma & Breen, 2012 ) allow us to consider the perspectives and experiences of both partners in relation to their sexual encounters. Quantitative dyadic studies typically use Actor-Partner Interdependence Models (APIM) and adopt special protocols when individuals within dyads are indistinguishable such as same-sex couples or same-sex siblings ( Kroeger and Powers 2019 ). But qualitative dyadic studies have also emerged (e.g., Reczek & Umberson, 2016 ), and blended methods have the potential to spur new insights into dyadic processes that influence health.

Dyadic data offer three significant innovations for family research. First, studies of discordance and concordance within a dyad promote a fuller understanding of the couple’s dynamics and the health consequences of the two members’ discordance or concordance. Second, dyadic data tell us how one partner influences the other by drawing on information that each member provides independently. Third, data can be collected from both members of the dyad at the same time to develop a holistic narrative about the dyad and their interactions ( Thomeer et al. 2018 ). This is a common approach in experimental studies, including Kiecolt-Glaser and Wilson’s (2017) research on couple interactions (e.g., marital conflict), which combined observational data with biomarker assessments of the physiological consequences of the interactions for both partners. Some family-level studies move beyond the dyad to include more family members (e.g., children, siblings, parents). Like dyadic data, family-level methods give researchers access to different family member perspectives, which enhances understanding of what may be going on within the family. Ethnographic studies can also provide rich examples of family-level data. For example, the Three-City Study ethnography project ( http://web.jhu.edu/threecitystudy/index.html )—which also collects survey and interview data—followed 256 low-income mothers and their children over a six-year period to understand the unfolding processes of childhood illness, family comorbidities, and domestic violence in families and communities ( Burton, Purvin, & Garrett-Peters, 2015 ). Over the next decade, family and health studies would benefit from more studies that include multiple family members and blend ethnographic inquiry with quantitative data (e.g., Bair-Merritt et al., 2015 ; Burton, Purvin & Garrett-Peters, 2015 ) to assess the complex ways that families and health are related.

Causal Inference

Decades of research make it clear that family ties and health are closely linked, but questions remain about the extent to which these linkages reflect selection versus causation. Selection bias is likely an important driver in many of the observed differences in health among people with different family structures and family dynamics. For example, prior research finds a strong association between parental divorce and children’s poor health. It is difficult to claim that this link is causal, however, because many of the same factors that predispose people to divorce (e.g., poverty, mental disorders) also negatively impact children’s health ( Amato & Anthony, 2014 ). Recent methodological innovations have allowed for better disentanglement of the processes that link family ties and dynamics to health and specifically enable researchers to address the role of selection. For example, researchers increasingly use matching techniques, which reduce imbalance, model dependence, and the influence of confounding variables and provide insight into long-assumed causal family-health linkages. Tumin and Zheng (2018) used a composite of demographic, economic, and health characteristics to generate propensity scores for estimating the likelihood of marriage and found that once these propensities for marriage were taken into account, married adults were only modestly healthier than unmarried adults both physically and mentally. Other techniques to address causal inference, such as fixed-effect models, placebo regressions, and inverse‐probability‐weighted estimation of marginal structural models, are also gaining popularity in family and health studies ( Gangl, 2010 ). Each of these techniques has key limitations, however, including limitations related to unobserved heterogeneity despite attempts to eliminate this issue.

Going forward, two approaches are particularly likely to spur innovation and new insights into causal processes. First, quantitative behavior-genetic designs may allow researchers to better understand causal paths and the role of selection by ruling out possible confounding genetic factors ( Oppenheimer, Tenenbaum, & Krynski, 2013 ). For example, the quality of the parent-child relationship is associated with child-adjustment outcomes, but it may be that these links reflect gene-environment interplay effects ( Oppenheimer, Tenenbaum, & Krynski, 2013 ). Genetically informed studies over the past decade have interrogated whether the well-documented associations between marital status or marital quality and health may be artifacts of genetic and/or shared environmental selection; many of these studies have used population-level twin samples (e.g., Dinescu, et al., 2016 ). Studies with a behavior-genetics design can also provide insight into why some people’s health is more sensitive than others’ to family dynamics. Second, natural experiments in which people are exposed to either the experimental or the control condition by an external force (e.g., natural disaster, public policies) are a useful way to test causal inferences about family and health ( Craig, et al., 2017 ). For example, Everett and colleagues (2016) compared depressive symptoms before and after the passage of an Illinois law recognizing same-sex civil unions. They found that this supportive social policy benefited the health of sexual minority women, especially sexual minority women of color. Regardless of the specific approach, any research attempting to make causal claims about family ties and health must recognize methodological limitations and carefully interpret findings within the context of rich theoretical frameworks and critical descriptive research.

Research on families and health is thriving. It is moving in exciting, new directions and offers great potential to inform efforts to improve population health and reduce health disparities, especially those connected to the family. Many of the major research advances over the past decade were made possible by innovative and novel sources of data and methods, particularly high-quality longitudinal data, dyadic and multiple-family-member reporting, inclusion of underrepresented populations (e.g., sexual and gender diverse populations, children in nontraditional families), and the increasing sophistication of biomarker measures to help explain the impact of family ties on health from childhood through adulthood. Significant advances include: (a) growing evidence that family structures and dynamics in childhood have lasting effects not only into adolescence and early adulthood but throughout the life course, even affecting later life risk for chronic diseases and mortality; (b) biosocial approaches that take into account multiple levels of analysis to show how family experiences activate psychological, physiological, behavioral, and social pathways that intersect and cascade to influence health from childhood through adulthood; (c) attention to reciprocity and contagion to show how family members influence each other’s health and well-being over time; and (d) increased recognition and understanding of sociodemographic variability and the role of selection bias in the linkages between family ties and health.

Future research on families and health should extend these accomplishments by more fully addressing the complexity of family structures and dynamics over the entire life course and expanding knowledge about the factors and mechanisms that protect and promote the health of multiple family members. The lifelong health consequences of childhood family environments point to the need to bridge the literature on family ties and child health with that on family ties and adult health—now two largely separate literatures. This will require long-term investment in longitudinal data collections that follow individuals from childhood into later life and inclusion of wide-ranging explanatory mechanisms and health outcomes. Typically, researchers analyze very different outcomes when they study health at different ages. For example, studies of children and adolescents rely heavily on measures of externalizing behaviors, mental health, asthma, and obesity, but studies of older adults primarily consider mortality, disability, and cognitive decline. Longitudinal studies—together with a strong theoretical foundation and richly textured biosocial measures that can be assessed across the lifespan—can further clarify how family and health are connected and how explanatory biosocial mechanisms unfold over time (e.g., family stress in childhood might contribute to asthma which leads to midlife inflammation and later-life chronic conditions). Similar consideration should be given to measures of family dynamics across the life course; for example, a life course approach to family and health would benefit by comparing types and degree of support and conflict between adolescent children and their parents to support and conflict those same children have with their parents in midlife. Across these areas, research should attend to diversity in family and health experiences associated with race, ethnicity, gender and sexuality, and socioeconomic status, as well as the health effects of the absence of family ties and socially isolated periods over the lifespan.

Recent advances in research on family instability in childhood ( Cavanagh & Fomby, 2019 ) and marital biographies in adulthood ( McFarland, Hayward, & Brown, 2013 ) take into account life course relationship experiences that accumulate over time to predict health. These advances suggest the usefulness of developing a family biography approach to promote and synthesize future research advances. A family biography would take into account family experiences throughout childhood (e.g., timing and sequencing of major transitions and periods of instability); document subsequent family structures and transitions as individuals grow older (e.g., intimate partnerships, parenthood, unpartnered periods); consider how childhood family experiences are linked to subsequent family ties; assess how the entire family biography coalesces to protect or undermine health (including both specific health outcomes/causes of death and overall health and mortality risk), and address how these processes vary across diverse populations. A family biography approach could serve as an organizational tool for future research on families and health and would be useful across theoretical perspectives and methods. Indeed, richer theoretical and methodological breadth at any point in the family biographical timeline would enrich our understanding of when, how, and for whom family ties shape health trajectories and turning points over the lifespan. A life course approach that addresses childhood through adulthood also provides a framework for clarifying the transmission of family dynamics and health across generations.

Research over the next decade should be designed with attention to policy and practice. Growing attention to the lifelong consequences of childhood family experiences highlights the potential lifelong reach of early-life interventions and policies that support families and children. Yet family ties and transitions throughout adulthood also offer opportunities to promote health and well-being across diverse populations. To successfully support the health of individual family members, intervention strategies and policies must be based on sound evidence. For example, Gershoff and colleagues (2018) rally substantial empirical evidence pointing to the need to better educate parents about the adverse short- and long-term effects of spanking on the health and well-being of children and to implement social policies and laws that prohibit physical punishment of children. Such policies offer the opportunity to reduce stress and promote childhood health. Research specifically designed to assess the efficacy of policies and interventions is also needed. For example, studies conducted over the past decade establish the potential population health benefits of marriage equality for same-sex couples ( Denney, et al., 2013 ; Liu, et al., 2013 ). Yet LeBlanc and colleagues (2018) show that legal changes do not fully address the negative mental health effects of institutionalized discrimination against same-sex couples. These studies underscore the need for nuanced and methodologically sophisticated research that will generate the evidence needed to design effective policies and interventions and to evaluate their effectiveness and consequences.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This work was supported in part by grant P2CHD042849, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and grant R01 AG054624 (PI, Debra Umberson) awarded by the National Institute on Aging.

Contributor Information

Debra Umberson, Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin, 305 E 23 rd Street, Austin TX.

Mieke Beth Thomeer, Department of Sociology, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

- Amato PR, & Anthony CJ (2014). Estimating the effects of parental divorce and death with fixed effects models . Journal of Marriage and Family , 76 , 370–386. 10.1111/jomf.12100 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- The Annie E.Casey Foundation. (2016). Kids Count Data Center . https://datacenter.kidscount.org

- MS#6668. (2020). A decade of research on gender and sexual minority families . Journal of Marriage and Family 82 ( 1 ): pp. XXX. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- MS#6752. (2020). Spanning borders, cultures, and generations: A decade of research on immigrant families . Journal of Marriage and Family 82 ( 1 ): pp. XXX. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- MS#6755. (2020). Children’s and adolescent’s development and well-being: Family processes and features . Journal of Marriage and Family 82 ( 1 ): pp. XXX. [ Google Scholar ]

- MS#6759. (2020). Parenthood, childlessness, and well-being research in the 2010s . Journal of Marriage and Family 82 ( 1 ): pp. XXX. [ Google Scholar ]

- MS#6760. (2020). The demography of families: A review of the 2010s . Journal of Marriage and Family 82 ( 1 ): pp. XXX. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- MS#6776. (2020). Families in later life: A decade in review . Journal of Marriage and Family . 82 ( 1 ): pp. XXX. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- MS#6811. (2020). Intimate partner violence: A decade in review . Journal of Marriage and Family . 82 ( 1 ): pp. XXX. [ Google Scholar ]

- MS#6827. (2020). Families across the income spectrum: A decade in review . Journal of Marriage and Family . 82 ( 1 ): pp. XXX. [ Google Scholar ]

- Avison WR (2010). Incorporating children’s lives into a life course perspective on stress and mental health . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 51 , 361–375. 10.1177/0022146510386797 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bair-Merritt MH, Voegtline K, Ghazarian SR, Granger DA, Blair C, Family Life Project Investigators, & Johnson, S. B. (2015). Maternal intimate partner violence exposure, child cortisol reactivity and child asthma . Child Abuse & Neglect , 48 , 50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.11.003 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bajaj A, John-Henderson NA, Cundiff JM, Marsland AL, Manuck SB & Kamarck TW (2016). Daily social interactions, close relationships, and systemic inflammation in two samples: Healthy middle-aged and older adults . Brain, Behavior, and Immunity , 58 , 152–64. 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.06.004. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Benner AD, Wang Y, Shen Y, Boyle AE, Polk R, & Cheng YP (2018). Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: A meta-analytic review . The American Psychologist , 73 , 855–883. 10.1037/amp0000204 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burton LM, Purvin D, & Garrett-Peters R (2015). Longitudinal ethnography: Uncovering domestic abuse in low-income women’s lives. In Hall J (Ed.), Female Students and Cultures of Violence in Cities (pp. 37–88). New York: Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carr D, & Springer KW (2010). Advances in families and health research in the 21st century . Journal of Marriage and Family , 72 , 743–761. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00728.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cavanagh SE, & Fomby P (2019). Family instability in the lives of American children . Annual Review of Sociology , 45 . 10.1146/annurev-soc-073018-022633 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chaudry A, & and Wimer C (2016). Poverty is not just an indicator: The relationship between income, poverty, and child well-being . Academic Pediatrics , 16 , S23–S29. 10.1016/j.acap.2015.12.010 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cobb LK, McAdams-DeMarco MA, Gudzune KA, Anderson CA, Demerath E, Woodward M, … Coresh J (2015). Changes in body mass index and obesity risk in married couples over 25 years: The Aric Cohort Study . American Journal of Epidemiology , 183 , 435–443. 10.1093/aje/kwv112 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cordero‐Coma J & Breen R (2012). HIV prevention and social desirability: Husband–wife discrepancies in reports of condom use . Journal of Marriage and Family , 74 , 601–613. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00976.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Craig P, Katikireddi SV, Leyland A, & Popham F (2017). Natural experiments: an overview of methods, approaches, and contributions to public health intervention research . Annual Review of Public Health , 38 , 39–56. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044327 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Delaney L, & Smith JP (2012). Childhood health: Trends and consequences over the life course . The Future of Children , 22 , 43–63. PMC3652568 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Denney JT, Gorman BK, & Barrera CB (2013). Families, resources, and adult health: Where do sexual minorities fit? Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 54 , 46–63. 10.1177/0022146512469629 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dill-McFarland K, Tang Z, Kemis J, Kerby R, Chen G, Palloni A, Sorenson T, Rey FE, & Herd P (2019). Close social relationships correlate with human gut microbiota composition . Scientific Reports , 9 , 703. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dinescu D, Turkheimer E, Beam CR, Horn EE, Duncan G, & Emery RE (2016). Is marriage a buzzkill? A twin study of marital status and alcohol consumption . Journal of Family Psychology , 30 , 698–707. 10.1037/fam0000221 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dupre ME (2016). Race, marital history, and risks for stroke in US older adults . Social Forces , 95 , 439–468. 10.1037/fam0000068 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elder Glenn H. Jr., Johnson MK, & Crosnoe R 2003. “The emergence and development of life course theory.” Pp. 3–19 in Handbook of the Life Course , edited by Mortimer JT and Shanahan MJ. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Everett BG, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Hughes TL (2016). The impact of civil union legislation on minority stress, depression, and hazardous drinking in a diverse sample of sexual-minority women: A quasi-natural experiment . Social Science & Medicine , 169 , 180–190. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.036 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fomby P, & Osborne C (2017). Family instability, multipartner fertility, and behavior in middle childhood . Journal of Marriage and Family , 79 , 75–93. 10.1111/jomf.12349 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gangl M (2010). Causal inference in sociological research . Annual Review of Sociology , 36 , 21–47. 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102702 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gaydosh L, & Harris KM (2018). Childhood family instability and young adult health . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 59 , 371–390. 10.1177/0022146518785174 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gershoff ET, Goodman GS, Miller-Perrin CL, Holden GW, Jackson Y, & Kazdin AE (2018). The strength of the causal evidence against physical punishment of children and its implications for parents, psychologists, and policymakers . American Psychologist , 73 , 626–638. 10.1037/amp0000327 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Glauber R, & Day MD (2018). Gender, spousal caregiving, and depression: Does paid work matter? Journal of Marriage and Family , 80 , 537–554. 10.1111/jomf.12446 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guldin M-B, Li J, Pedersen HS, Obel C, Agerbo E, Gissler M, … Vestergaard M (2015). Incidence of suicide among persons who had a parent who died during their childhood: A population-based cohort study . JAMA Psychiatry , 72 , 1227–34. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2094 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hardie JH, & Landale NS (2013). Profiles of risk: Maternal health, socioeconomic status, and child health . Journal of Marriage and Family , 75 , 651–66. 10.1111/jomf.12021 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hardie JH, & Turney K (2017). The intergenerational consequences of parental health limitations . Journal of Marriage and Family , 79 , 801–815. 10.1111/jomf.12341 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Iveniuk J, Waite LJ, Laumann E, McClintock MK, & Tiedt AD (2014). Marital conflict in older couples: Positivity, personality, and health . Journal of Marriage and Family , 76 , 130–144. 10.1111/jomf.12085 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kamp Dush CM (2013). Marital and cohabitation dissolution and parental depressive symptoms in fragile families . Journal of Marriage and Family , 75 , 91–109. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01020.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, & Wilson SJ (2017). Lovesick: How couples’ relationships influence health . Annual Review of Clinical Psychology , 13 , 421–443. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045111 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Wilson SJ, & Madison A (2018). Marriage and gut (microbiome) feelings: Tracing novel dyadic pathways to accelerated aging .” Psychosomatic Medicine . DOI: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000647 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kroeger Rhiannon A and Powers Daniel A. 2019. “Examining same-sex couples using dyadic data methods.” Pp. 157–86 in Analytical Family Demography : Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Landale NS, Hardie JH, Oropesa RS, & Hillemeier MM (2015). Behavioral functioning among Mexican-origin children: Does parental legal status matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 56 , 2–18. 10.1177/0022146514567896 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- LeBlanc AJ, Frost DM, & Bowen K (2018). Legal marriage, unequal recognition, and mental health among same‐sex couples . Journal of Marriage and Family , 80 , 397–408. 10.1111/jomf.12460 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee D, & McLanahan S (2015). Family structure transitions and child development: Instability, selection, and population heterogeneity . American Sociological Review , 80 , 738–763. 10.1177/0003122415592129 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu H, Reczek C, & Brown D (2013). Same-sex cohabitors and health: The role of race-ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 54 , 25–45. 10.1177/0022146512468280 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu H, & Wilkinson L (2017). Marital status and perceived discrimination among transgender people . Journal of Marriage and Family , 79 , 1295–1313. 10.1111/jomf.12424 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Madigan S, Plamondon A, & Jenkins JM (2016). Marital conflict trajectories and associations with children’s disruptive behavior . Journal of Marriage and Family , 79 , 437–450. 10.1111/jomf.12356 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maimon D, Browning CR, & Brooks-Gunn J (2010). Collective efficacy, family attachment, and urban adolescent suicide attempts . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 51 , 307–324. 10.1177/0022146510377878 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Markowitz AJ, & Ryan RM (2016). Father absence and adolescent depression and delinquency: A comparison of siblings approach . Journal of Marriage and Family , 78 , 1300–14. 10.1111/jomf.12343 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McFarland MJ, Hayward MD, & Brown D (2013). I’ve got you under my skin: Marital biography and biological risk . Journal of Marriage and the Family , 75 , 363–380. 10.1111/jomf.12015 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller GE, & Chen E (2010). Harsh family climate in early life presages the emergence of a proinflammatory phenotype in adolescence . Psychological Science , 21 , 848–856. 10.1177/0956797610370161 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller GE, Chen E, & Parker KJ (2011). Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms . Psychological Bulletin , 137 , 959–997. 10.1037/a0024768 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller RB, Hollist CS, Olsen J, & Law D (2013). Marital quality and health over 20 years: A growth curve analysis . Journal of Marriage and Family , 75 , 667–680. 10.1111/jomf.12025 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mood C, Jonsson JO, & Låftman SB (2016). The mental health advantage of immigrant‐background youth: The role of family factors . Journal of Marriage and Family , 79 , 419–436. 10.1111/jomf.12340 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oppenheimer DM, Tenenbaum JB, & Krynski TR (2013). Categorization as causal explanation: Discounting and augmenting in a Bayesian framework. In Ross BH (Ed.), Psychology of Learning and Motivation (Vol. 58 , pp. 203–231). Academic Press. 10.1016/B978-0-12-407237-4.00006-2 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paley B, Lester P, & Mogil C (2013). Family systems and ecological perspectives on the impact of deployment on military families . Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review , 16 , 245–265. https://doi-org/10.1007/s10567-013-0138-y [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, & Meersman SC (2005). Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 46 , 205–219. 10.1177/002214650504600206 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pfeffer CA (2016). Queering families: The postmodern partnerships of cisgender women and transgender men . New York: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Raver C Cybele, Roy Amanda L and Pressler Emily. 2015. “Struggling to Stay Afloat: Dynamic Models of Poverty-Related Adversity and Child Outcomes.” Pp. 201–12 in Families in an Era of Increasing Inequality : Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reczek C, Pudrovska T, Carr D, Thomeer MB, & Umberson D (2016a). Marital histories and heavy alcohol use among older adults . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 57 , 77–96. 10.1177/0022146515628028 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reczek C, Spiker R, Liu H, & Crosnoe R (2016b). Family structure and child health: Does the sex composition of parents matter? Demography , 53 , 1605–30. 10.1007/s13524-016-0501-y [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reczek C, & Umberson D (2016). Greedy spouse, needy parent: The marital dynamics of gay, lesbian, and heterosexual intergenerational caregivers . Journal of Marriage and Family , 78 , 957–74. 10.1111/jomf.12318 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rendall MS, Weden MM, Favreault MM, & Waldron H (2011). The protective effect of marriage for survival: A review and update . Demography , 48 , 481–506. 10.1007/s13524-011-0032-5 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Repetti RL, Robles TF, & Reynolds B (2011). Allostatic processes in the family . Development and psychopathology , 23 , 921–938. 10.1017/S095457941100040X [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, & McGinn MM (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review . Psychological Bulletin , 140 , 140–187. 10.1037/a0031859 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Roelfs DJ, Shor E, Curreli M, Clemow L, Burg MM, & Schwartz JE (2012). Widowhood and mortality: A meta-analysis and meta-regression . Demography , 49 , 575–606. 10.1007/s13524-012-0096-x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Roxburgh S (2014). Race, class, and gender differences in the marriage-health relationship . Race, Gender & Class , 21 , 7–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43496982 [ Google Scholar ]

- Schreier H, & Chen E (2013). Socioeconomic status and the health of youth: A multilevel multidomain approach to conceptualizing pathways . Psychological Bulletin , 139 , 606–654). 10.1037/a0029416 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thomeer MB, LeBlanc AJ, Frost DM, & Bowen K (2018). Anticipatory minority stressors among same-sex couples: A relationship timeline approach . Social Psychology Quarterly , 81 , 126–148. 10.1177/0190272518769603 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thomeer MB, Paine E, & Bryant C (2017). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender families and health . Sociology Compass , 12 , e12552. 10.1111/soc4.12552 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thomeer MB, Umberson D, & Pudrovska T (2013). Marital processes around depression: A gendered and relational perspective . Society and Mental Health , 3 , 151–69. 10.1177/2156869313487224 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Timmons AC, Margolin G, & Saxbe DE (2015). Physiological linkage in couples and its implications for individual and interpersonal functioning: A literature review . Journal of Family Psychology , 29 , 720–731. 10.1037/fam0000115 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tumin D, & Zheng H (2018). Do the health benefits of marriage depend on the likelihood of marriage? , Journal of Marriage and Family , 80 , 622–636. 10.1111/jomf.12471 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Turney K (2011). Maternal depression and childhood health inequalities . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 52 , 314–332. 10.1177/0022146511408096 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Turney Kristin. (2014). Stress proliferation across generations? Examining the relationship between parental incarceration and childhood health . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 55 , 302–319. https://doi.org/0.1177/0022146514544173 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D (2017). Black deaths matter: Race, relationship loss, and effects on survivors . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 58 , 405–420. 10.1177/0022146517739317 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D, Thomeer M, Reczek C, & Donnelly R (2016). Physical illness in gay, lesbian, and heterosexual marriages: Gendered dyadic experiences . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 57 , 517–531. 10.1177/0022146516671570 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D, Williams K, Thomas PA, Liu H, & Thomeer MB (2014). Race, gender, and chains of disadvantage: Childhood adversity, social relationships, and health . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 55 , 20–38. 10.1177/0022146514521426 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Waite EB, Shanahan L, Calkins SD, Keane SP, & O’Brien M (2011). Life events, sibling warmth, and youths’ adjustment . Journal of Marriage and Family , 73 , 902–912. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00857.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wakefield S, & Uggen C (2010). Incarceration and stratification . Annual Review of Sociology , 36 , 387–406. 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102551 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Williams K, Sassler S, Frech A, Addo F, & Cooksey E (2011). Nonmarital childbearing, union history, and women’s health at midlife . American Sociological Review , 76 , 465–486. 10.1177/0003122411409705 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zebrak KA, & Green KM (2016). Mutual influences between parental psychological distress and alcohol use and child problem behavior in a cohort of urban African Americans . Journal of Family Issues , 37 , 1869–1890. 10.1177/0192513X14553055 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Articles on Families

Displaying 1 - 20 of 184 articles.

‘It’s a deep emotional ride’ – 12 young people in Philly’s toughest neighborhoods explain how violence disrupts their physical and mental health

Kalen Flynn , University of Pennsylvania

A survey of non-traditional family-making suffers from a ‘ feminism-lite ’ lack of focus

Amy Walters , Australian National University

3 years after Canada’s landmark investment in child care, 3 priorities all levels of government should heed

Elizabeth Dhuey , University of Toronto

Why are Americans fighting over no-fault divorce? Maybe they can’t agree what marriage is for

Marcia Zug , University of South Carolina