- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Qualitative Methods

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The word qualitative implies an emphasis on the qualities of entities and on processes and meanings that are not experimentally examined or measured [if measured at all] in terms of quantity, amount, intensity, or frequency. Qualitative researchers stress the socially constructed nature of reality, the intimate relationship between the researcher and what is studied, and the situational constraints that shape inquiry. Such researchers emphasize the value-laden nature of inquiry. They seek answers to questions that stress how social experience is created and given meaning. In contrast, quantitative studies emphasize the measurement and analysis of causal relationships between variables, not processes. Qualitative forms of inquiry are considered by many social and behavioral scientists to be as much a perspective on how to approach investigating a research problem as it is a method.

Denzin, Norman. K. and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Introduction: The Discipline and Practice of Qualitative Research.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman. K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. 3 rd edition. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005), p. 10.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Below are the three key elements that define a qualitative research study and the applied forms each take in the investigation of a research problem.

- Naturalistic -- refers to studying real-world situations as they unfold naturally; non-manipulative and non-controlling; the researcher is open to whatever emerges [i.e., there is a lack of predetermined constraints on findings].

- Emergent -- acceptance of adapting inquiry as understanding deepens and/or situations change; the researcher avoids rigid designs that eliminate responding to opportunities to pursue new paths of discovery as they emerge.

- Purposeful -- cases for study [e.g., people, organizations, communities, cultures, events, critical incidences] are selected because they are “information rich” and illuminative. That is, they offer useful manifestations of the phenomenon of interest; sampling is aimed at insight about the phenomenon, not empirical generalization derived from a sample and applied to a population.

The Collection of Data

- Data -- observations yield a detailed, "thick description" [in-depth understanding]; interviews capture direct quotations about people’s personal perspectives and lived experiences; often derived from carefully conducted case studies and review of material culture.

- Personal experience and engagement -- researcher has direct contact with and gets close to the people, situation, and phenomenon under investigation; the researcher’s personal experiences and insights are an important part of the inquiry and critical to understanding the phenomenon.

- Empathic neutrality -- an empathic stance in working with study respondents seeks vicarious understanding without judgment [neutrality] by showing openness, sensitivity, respect, awareness, and responsiveness; in observation, it means being fully present [mindfulness].

- Dynamic systems -- there is attention to process; assumes change is ongoing, whether the focus is on an individual, an organization, a community, or an entire culture, therefore, the researcher is mindful of and attentive to system and situational dynamics.

The Analysis

- Unique case orientation -- assumes that each case is special and unique; the first level of analysis is being true to, respecting, and capturing the details of the individual cases being studied; cross-case analysis follows from and depends upon the quality of individual case studies.

- Inductive analysis -- immersion in the details and specifics of the data to discover important patterns, themes, and inter-relationships; begins by exploring, then confirming findings, guided by analytical principles rather than rules.

- Holistic perspective -- the whole phenomenon under study is understood as a complex system that is more than the sum of its parts; the focus is on complex interdependencies and system dynamics that cannot be reduced in any meaningful way to linear, cause and effect relationships and/or a few discrete variables.

- Context sensitive -- places findings in a social, historical, and temporal context; researcher is careful about [even dubious of] the possibility or meaningfulness of generalizations across time and space; emphasizes careful comparative case study analysis and extrapolating patterns for possible transferability and adaptation in new settings.

- Voice, perspective, and reflexivity -- the qualitative methodologist owns and is reflective about her or his own voice and perspective; a credible voice conveys authenticity and trustworthiness; complete objectivity being impossible and pure subjectivity undermining credibility, the researcher's focus reflects a balance between understanding and depicting the world authentically in all its complexity and of being self-analytical, politically aware, and reflexive in consciousness.

Berg, Bruce Lawrence. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences . 8th edition. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2012; Denzin, Norman. K. and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Handbook of Qualitative Research . 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000; Marshall, Catherine and Gretchen B. Rossman. Designing Qualitative Research . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2009.

Basic Research Design for Qualitative Studies

Unlike positivist or experimental research that utilizes a linear and one-directional sequence of design steps, there is considerable variation in how a qualitative research study is organized. In general, qualitative researchers attempt to describe and interpret human behavior based primarily on the words of selected individuals [a.k.a., “informants” or “respondents”] and/or through the interpretation of their material culture or occupied space. There is a reflexive process underpinning every stage of a qualitative study to ensure that researcher biases, presuppositions, and interpretations are clearly evident, thus ensuring that the reader is better able to interpret the overall validity of the research. According to Maxwell (2009), there are five, not necessarily ordered or sequential, components in qualitative research designs. How they are presented depends upon the research philosophy and theoretical framework of the study, the methods chosen, and the general assumptions underpinning the study. Goals Describe the central research problem being addressed but avoid describing any anticipated outcomes. Questions to ask yourself are: Why is your study worth doing? What issues do you want to clarify, and what practices and policies do you want it to influence? Why do you want to conduct this study, and why should the reader care about the results? Conceptual Framework Questions to ask yourself are: What do you think is going on with the issues, settings, or people you plan to study? What theories, beliefs, and prior research findings will guide or inform your research, and what literature, preliminary studies, and personal experiences will you draw upon for understanding the people or issues you are studying? Note to not only report the results of other studies in your review of the literature, but note the methods used as well. If appropriate, describe why earlier studies using quantitative methods were inadequate in addressing the research problem. Research Questions Usually there is a research problem that frames your qualitative study and that influences your decision about what methods to use, but qualitative designs generally lack an accompanying hypothesis or set of assumptions because the findings are emergent and unpredictable. In this context, more specific research questions are generally the result of an interactive design process rather than the starting point for that process. Questions to ask yourself are: What do you specifically want to learn or understand by conducting this study? What do you not know about the things you are studying that you want to learn? What questions will your research attempt to answer, and how are these questions related to one another? Methods Structured approaches to applying a method or methods to your study help to ensure that there is comparability of data across sources and researchers and, thus, they can be useful in answering questions that deal with differences between phenomena and the explanation for these differences [variance questions]. An unstructured approach allows the researcher to focus on the particular phenomena studied. This facilitates an understanding of the processes that led to specific outcomes, trading generalizability and comparability for internal validity and contextual and evaluative understanding. Questions to ask yourself are: What will you actually do in conducting this study? What approaches and techniques will you use to collect and analyze your data, and how do these constitute an integrated strategy? Validity In contrast to quantitative studies where the goal is to design, in advance, “controls” such as formal comparisons, sampling strategies, or statistical manipulations to address anticipated and unanticipated threats to validity, qualitative researchers must attempt to rule out most threats to validity after the research has begun by relying on evidence collected during the research process itself in order to effectively argue that any alternative explanations for a phenomenon are implausible. Questions to ask yourself are: How might your results and conclusions be wrong? What are the plausible alternative interpretations and validity threats to these, and how will you deal with these? How can the data that you have, or that you could potentially collect, support or challenge your ideas about what’s going on? Why should we believe your results? Conclusion Although Maxwell does not mention a conclusion as one of the components of a qualitative research design, you should formally conclude your study. Briefly reiterate the goals of your study and the ways in which your research addressed them. Discuss the benefits of your study and how stakeholders can use your results. Also, note the limitations of your study and, if appropriate, place them in the context of areas in need of further research.

Chenail, Ronald J. Introduction to Qualitative Research Design. Nova Southeastern University; Heath, A. W. The Proposal in Qualitative Research. The Qualitative Report 3 (March 1997); Marshall, Catherine and Gretchen B. Rossman. Designing Qualitative Research . 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1999; Maxwell, Joseph A. "Designing a Qualitative Study." In The SAGE Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods . Leonard Bickman and Debra J. Rog, eds. 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2009), p. 214-253; Qualitative Research Methods. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Yin, Robert K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish . 2nd edition. New York: Guilford, 2015.

Strengths of Using Qualitative Methods

The advantage of using qualitative methods is that they generate rich, detailed data that leave the participants' perspectives intact and provide multiple contexts for understanding the phenomenon under study. In this way, qualitative research can be used to vividly demonstrate phenomena or to conduct cross-case comparisons and analysis of individuals or groups.

Among the specific strengths of using qualitative methods to study social science research problems is the ability to:

- Obtain a more realistic view of the lived world that cannot be understood or experienced in numerical data and statistical analysis;

- Provide the researcher with the perspective of the participants of the study through immersion in a culture or situation and as a result of direct interaction with them;

- Allow the researcher to describe existing phenomena and current situations;

- Develop flexible ways to perform data collection, subsequent analysis, and interpretation of collected information;

- Yield results that can be helpful in pioneering new ways of understanding;

- Respond to changes that occur while conducting the study ]e.g., extended fieldwork or observation] and offer the flexibility to shift the focus of the research as a result;

- Provide a holistic view of the phenomena under investigation;

- Respond to local situations, conditions, and needs of participants;

- Interact with the research subjects in their own language and on their own terms; and,

- Create a descriptive capability based on primary and unstructured data.

Anderson, Claire. “Presenting and Evaluating Qualitative Research.” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 74 (2010): 1-7; Denzin, Norman. K. and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Handbook of Qualitative Research . 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2009.

Limitations of Using Qualitative Methods

It is very much true that most of the limitations you find in using qualitative research techniques also reflect their inherent strengths . For example, small sample sizes help you investigate research problems in a comprehensive and in-depth manner. However, small sample sizes undermine opportunities to draw useful generalizations from, or to make broad policy recommendations based upon, the findings. Additionally, as the primary instrument of investigation, qualitative researchers are often embedded in the cultures and experiences of others. However, cultural embeddedness increases the opportunity for bias generated from conscious or unconscious assumptions about the study setting to enter into how data is gathered, interpreted, and reported.

Some specific limitations associated with using qualitative methods to study research problems in the social sciences include the following:

- Drifting away from the original objectives of the study in response to the changing nature of the context under which the research is conducted;

- Arriving at different conclusions based on the same information depending on the personal characteristics of the researcher;

- Replication of a study is very difficult;

- Research using human subjects increases the chance of ethical dilemmas that undermine the overall validity of the study;

- An inability to investigate causality between different research phenomena;

- Difficulty in explaining differences in the quality and quantity of information obtained from different respondents and arriving at different, non-consistent conclusions;

- Data gathering and analysis is often time consuming and/or expensive;

- Requires a high level of experience from the researcher to obtain the targeted information from the respondent;

- May lack consistency and reliability because the researcher can employ different probing techniques and the respondent can choose to tell some particular stories and ignore others; and,

- Generation of a significant amount of data that cannot be randomized into manageable parts for analysis.

Research Tip

Human Subject Research and Institutional Review Board Approval

Almost every socio-behavioral study requires you to submit your proposed research plan to an Institutional Review Board. The role of the Board is to evaluate your research proposal and determine whether it will be conducted ethically and under the regulations, institutional polices, and Code of Ethics set forth by the university. The purpose of the review is to protect the rights and welfare of individuals participating in your study. The review is intended to ensure equitable selection of respondents, that you have met the requirements for obtaining informed consent , that there is clear assessment and minimization of risks to participants and to the university [read: no lawsuits!], and that privacy and confidentiality are maintained throughout the research process and beyond. Go to the USC IRB website for detailed information and templates of forms you need to submit before you can proceed. If you are unsure whether your study is subject to IRB review, consult with your professor or academic advisor.

Chenail, Ronald J. Introduction to Qualitative Research Design. Nova Southeastern University; Labaree, Robert V. "Working Successfully with Your Institutional Review Board: Practical Advice for Academic Librarians." College and Research Libraries News 71 (April 2010): 190-193.

Another Research Tip

Finding Examples of How to Apply Different Types of Research Methods

SAGE publications is a major publisher of studies about how to design and conduct research in the social and behavioral sciences. Their SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases database includes contents from books, articles, encyclopedias, handbooks, and videos covering social science research design and methods including the complete Little Green Book Series of Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences and the Little Blue Book Series of Qualitative Research techniques. The database also includes case studies outlining the research methods used in real research projects. This is an excellent source for finding definitions of key terms and descriptions of research design and practice, techniques of data gathering, analysis, and reporting, and information about theories of research [e.g., grounded theory]. The database covers both qualitative and quantitative research methods as well as mixed methods approaches to conducting research.

SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases

NOTE : For a list of online communities, research centers, indispensable learning resources, and personal websites of leading qualitative researchers, GO HERE .

For a list of scholarly journals devoted to the study and application of qualitative research methods, GO HERE .

- << Previous: 6. The Methodology

- Next: Quantitative Methods >>

- Last Updated: May 15, 2024 9:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 679–689, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Drishti Yadav ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2974-0323 1

82k Accesses

28 Citations

72 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then, references of relevant articles were surveyed to find noteworthy, distinct, and well-defined pointers to good qualitative research. This review presents an investigative assessment of the pivotal features in qualitative research that can permit the readers to pass judgment on its quality and to condemn it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the necessity to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. It also offers some prospects and recommendations to improve the quality of qualitative research. Based on the findings of this review, it is concluded that quality criteria are the aftereffect of socio-institutional procedures and existing paradigmatic conducts. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single and specific set of quality criteria is neither feasible nor anticipated. Since qualitative research is not a cohesive discipline, researchers need to educate and familiarize themselves with applicable norms and decisive factors to evaluate qualitative research from within its theoretical and methodological framework of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Good Qualitative Research: Opening up the Debate

Beyond qualitative/quantitative structuralism: the positivist qualitative research and the paradigmatic disclaimer.

What is Qualitative in Research

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“… It is important to regularly dialogue about what makes for good qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 , p. 837)

To decide what represents good qualitative research is highly debatable. There are numerous methods that are contained within qualitative research and that are established on diverse philosophical perspectives. Bryman et al., ( 2008 , p. 262) suggest that “It is widely assumed that whereas quality criteria for quantitative research are well‐known and widely agreed, this is not the case for qualitative research.” Hence, the question “how to evaluate the quality of qualitative research” has been continuously debated. There are many areas of science and technology wherein these debates on the assessment of qualitative research have taken place. Examples include various areas of psychology: general psychology (Madill et al., 2000 ); counseling psychology (Morrow, 2005 ); and clinical psychology (Barker & Pistrang, 2005 ), and other disciplines of social sciences: social policy (Bryman et al., 2008 ); health research (Sparkes, 2001 ); business and management research (Johnson et al., 2006 ); information systems (Klein & Myers, 1999 ); and environmental studies (Reid & Gough, 2000 ). In the literature, these debates are enthused by the impression that the blanket application of criteria for good qualitative research developed around the positivist paradigm is improper. Such debates are based on the wide range of philosophical backgrounds within which qualitative research is conducted (e.g., Sandberg, 2000 ; Schwandt, 1996 ). The existence of methodological diversity led to the formulation of different sets of criteria applicable to qualitative research.

Among qualitative researchers, the dilemma of governing the measures to assess the quality of research is not a new phenomenon, especially when the virtuous triad of objectivity, reliability, and validity (Spencer et al., 2004 ) are not adequate. Occasionally, the criteria of quantitative research are used to evaluate qualitative research (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008 ; Lather, 2004 ). Indeed, Howe ( 2004 ) claims that the prevailing paradigm in educational research is scientifically based experimental research. Hypotheses and conjectures about the preeminence of quantitative research can weaken the worth and usefulness of qualitative research by neglecting the prominence of harmonizing match for purpose on research paradigm, the epistemological stance of the researcher, and the choice of methodology. Researchers have been reprimanded concerning this in “paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2000 ).

In general, qualitative research tends to come from a very different paradigmatic stance and intrinsically demands distinctive and out-of-the-ordinary criteria for evaluating good research and varieties of research contributions that can be made. This review attempts to present a series of evaluative criteria for qualitative researchers, arguing that their choice of criteria needs to be compatible with the unique nature of the research in question (its methodology, aims, and assumptions). This review aims to assist researchers in identifying some of the indispensable features or markers of high-quality qualitative research. In a nutshell, the purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyze the existing knowledge on high-quality qualitative research and to verify the existence of research studies dealing with the critical assessment of qualitative research based on the concept of diverse paradigmatic stances. Contrary to the existing reviews, this review also suggests some critical directions to follow to improve the quality of qualitative research in different epistemological and ontological perspectives. This review is also intended to provide guidelines for the acceleration of future developments and dialogues among qualitative researchers in the context of assessing the qualitative research.

The rest of this review article is structured in the following fashion: Sect. Methods describes the method followed for performing this review. Section Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies provides a comprehensive description of the criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. This section is followed by a summary of the strategies to improve the quality of qualitative research in Sect. Improving Quality: Strategies . Section How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings? provides details on how to assess the quality of the research findings. After that, some of the quality checklists (as tools to evaluate quality) are discussed in Sect. Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality . At last, the review ends with the concluding remarks presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook . Some prospects in qualitative research for enhancing its quality and usefulness in the social and techno-scientific research community are also presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook .

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed from many databases using generic search terms such as Qualitative Research , Criteria , etc . The following databases were chosen for the literature search based on the high number of results: IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The following keywords (and their combinations using Boolean connectives OR/AND) were adopted for the literature search: qualitative research, criteria, quality, assessment, and validity. The synonyms for these keywords were collected and arranged in a logical structure (see Table 1 ). All publications in journals and conference proceedings later than 1950 till 2021 were considered for the search. Other articles extracted from the references of the papers identified in the electronic search were also included. A large number of publications on qualitative research were retrieved during the initial screening. Hence, to include the searches with the main focus on criteria for good qualitative research, an inclusion criterion was utilized in the search string.

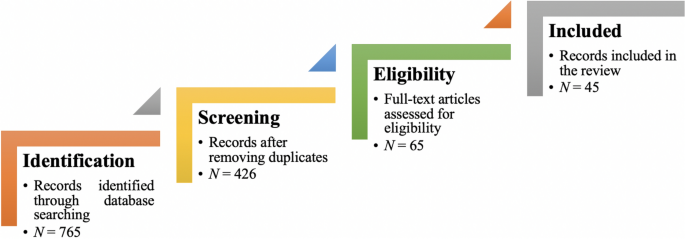

From the selected databases, the search retrieved a total of 765 publications. Then, the duplicate records were removed. After that, based on the title and abstract, the remaining 426 publications were screened for their relevance by using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2 ). Publications focusing on evaluation criteria for good qualitative research were included, whereas those works which delivered theoretical concepts on qualitative research were excluded. Based on the screening and eligibility, 45 research articles were identified that offered explicit criteria for evaluating the quality of qualitative research and were found to be relevant to this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete review process in the form of PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, i.e., “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” is employed in systematic reviews to refine the quality of reporting.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and inclusion process. N represents the number of records

Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies

Fundamental criteria: general research quality.

Various researchers have put forward criteria for evaluating qualitative research, which have been summarized in Table 3 . Also, the criteria outlined in Table 4 effectively deliver the various approaches to evaluate and assess the quality of qualitative work. The entries in Table 4 are based on Tracy’s “Eight big‐tent criteria for excellent qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 ). Tracy argues that high-quality qualitative work should formulate criteria focusing on the worthiness, relevance, timeliness, significance, morality, and practicality of the research topic, and the ethical stance of the research itself. Researchers have also suggested a series of questions as guiding principles to assess the quality of a qualitative study (Mays & Pope, 2020 ). Nassaji ( 2020 ) argues that good qualitative research should be robust, well informed, and thoroughly documented.

Qualitative Research: Interpretive Paradigms

All qualitative researchers follow highly abstract principles which bring together beliefs about ontology, epistemology, and methodology. These beliefs govern how the researcher perceives and acts. The net, which encompasses the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises, is referred to as a paradigm, or an interpretive structure, a “Basic set of beliefs that guides action” (Guba, 1990 ). Four major interpretive paradigms structure the qualitative research: positivist and postpositivist, constructivist interpretive, critical (Marxist, emancipatory), and feminist poststructural. The complexity of these four abstract paradigms increases at the level of concrete, specific interpretive communities. Table 5 presents these paradigms and their assumptions, including their criteria for evaluating research, and the typical form that an interpretive or theoretical statement assumes in each paradigm. Moreover, for evaluating qualitative research, quantitative conceptualizations of reliability and validity are proven to be incompatible (Horsburgh, 2003 ). In addition, a series of questions have been put forward in the literature to assist a reviewer (who is proficient in qualitative methods) for meticulous assessment and endorsement of qualitative research (Morse, 2003 ). Hammersley ( 2007 ) also suggests that guiding principles for qualitative research are advantageous, but methodological pluralism should not be simply acknowledged for all qualitative approaches. Seale ( 1999 ) also points out the significance of methodological cognizance in research studies.

Table 5 reflects that criteria for assessing the quality of qualitative research are the aftermath of socio-institutional practices and existing paradigmatic standpoints. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single set of quality criteria is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the researchers must be reflexive about the criteria they use in the various roles they play within their research community.

Improving Quality: Strategies

Another critical question is “How can the qualitative researchers ensure that the abovementioned quality criteria can be met?” Lincoln and Guba ( 1986 ) delineated several strategies to intensify each criteria of trustworthiness. Other researchers (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016 ; Shenton, 2004 ) also presented such strategies. A brief description of these strategies is shown in Table 6 .

It is worth mentioning that generalizability is also an integral part of qualitative research (Hays & McKibben, 2021 ). In general, the guiding principle pertaining to generalizability speaks about inducing and comprehending knowledge to synthesize interpretive components of an underlying context. Table 7 summarizes the main metasynthesis steps required to ascertain generalizability in qualitative research.

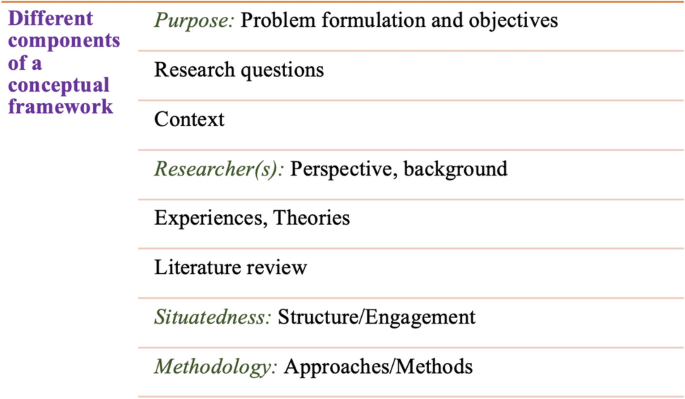

Figure 2 reflects the crucial components of a conceptual framework and their contribution to decisions regarding research design, implementation, and applications of results to future thinking, study, and practice (Johnson et al., 2020 ). The synergy and interrelationship of these components signifies their role to different stances of a qualitative research study.

Essential elements of a conceptual framework

In a nutshell, to assess the rationale of a study, its conceptual framework and research question(s), quality criteria must take account of the following: lucid context for the problem statement in the introduction; well-articulated research problems and questions; precise conceptual framework; distinct research purpose; and clear presentation and investigation of the paradigms. These criteria would expedite the quality of qualitative research.

How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings?

The inclusion of quotes or similar research data enhances the confirmability in the write-up of the findings. The use of expressions (for instance, “80% of all respondents agreed that” or “only one of the interviewees mentioned that”) may also quantify qualitative findings (Stenfors et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the persuasive reason for “why this may not help in intensifying the research” has also been provided (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020 ). Further, the Discussion and Conclusion sections of an article also prove robust markers of high-quality qualitative research, as elucidated in Table 8 .

Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality

Numerous checklists are available to speed up the assessment of the quality of qualitative research. However, if used uncritically and recklessly concerning the research context, these checklists may be counterproductive. I recommend that such lists and guiding principles may assist in pinpointing the markers of high-quality qualitative research. However, considering enormous variations in the authors’ theoretical and philosophical contexts, I would emphasize that high dependability on such checklists may say little about whether the findings can be applied in your setting. A combination of such checklists might be appropriate for novice researchers. Some of these checklists are listed below:

The most commonly used framework is Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007 ). This framework is recommended by some journals to be followed by the authors during article submission.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is another checklist that has been created particularly for medical education (O’Brien et al., 2014 ).

Also, Tracy ( 2010 ) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021 ) offer criteria for qualitative research relevant across methods and approaches.

Further, researchers have also outlined different criteria as hallmarks of high-quality qualitative research. For instance, the “Road Trip Checklist” (Epp & Otnes, 2021 ) provides a quick reference to specific questions to address different elements of high-quality qualitative research.

Conclusions, Future Directions, and Outlook

This work presents a broad review of the criteria for good qualitative research. In addition, this article presents an exploratory analysis of the essential elements in qualitative research that can enable the readers of qualitative work to judge it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. In this review, some of the essential markers that indicate high-quality qualitative research have been highlighted. I scope them narrowly to achieve rigor in qualitative research and note that they do not completely cover the broader considerations necessary for high-quality research. This review points out that a universal and versatile one-size-fits-all guideline for evaluating the quality of qualitative research does not exist. In other words, this review also emphasizes the non-existence of a set of common guidelines among qualitative researchers. In unison, this review reinforces that each qualitative approach should be treated uniquely on account of its own distinctive features for different epistemological and disciplinary positions. Owing to the sensitivity of the worth of qualitative research towards the specific context and the type of paradigmatic stance, researchers should themselves analyze what approaches can be and must be tailored to ensemble the distinct characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. Although this article does not assert to put forward a magic bullet and to provide a one-stop solution for dealing with dilemmas about how, why, or whether to evaluate the “goodness” of qualitative research, it offers a platform to assist the researchers in improving their qualitative studies. This work provides an assembly of concerns to reflect on, a series of questions to ask, and multiple sets of criteria to look at, when attempting to determine the quality of qualitative research. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the need to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. Bringing together the vital arguments and delineating the requirements that good qualitative research should satisfy, this review strives to equip the researchers as well as reviewers to make well-versed judgment about the worth and significance of the qualitative research under scrutiny. In a nutshell, a comprehensive portrayal of the research process (from the context of research to the research objectives, research questions and design, speculative foundations, and from approaches of collecting data to analyzing the results, to deriving inferences) frequently proliferates the quality of a qualitative research.

Prospects : A Road Ahead for Qualitative Research

Irrefutably, qualitative research is a vivacious and evolving discipline wherein different epistemological and disciplinary positions have their own characteristics and importance. In addition, not surprisingly, owing to the sprouting and varied features of qualitative research, no consensus has been pulled off till date. Researchers have reflected various concerns and proposed several recommendations for editors and reviewers on conducting reviews of critical qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2021 ; McGinley et al., 2021 ). Following are some prospects and a few recommendations put forward towards the maturation of qualitative research and its quality evaluation:

In general, most of the manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts. Hence, it is more likely that they would prefer to adopt a broad set of criteria. However, researchers and reviewers need to keep in mind that it is inappropriate to utilize the same approaches and conducts among all qualitative research. Therefore, future work needs to focus on educating researchers and reviewers about the criteria to evaluate qualitative research from within the suitable theoretical and methodological context.

There is an urgent need to refurbish and augment critical assessment of some well-known and widely accepted tools (including checklists such as COREQ, SRQR) to interrogate their applicability on different aspects (along with their epistemological ramifications).

Efforts should be made towards creating more space for creativity, experimentation, and a dialogue between the diverse traditions of qualitative research. This would potentially help to avoid the enforcement of one's own set of quality criteria on the work carried out by others.

Moreover, journal reviewers need to be aware of various methodological practices and philosophical debates.

It is pivotal to highlight the expressions and considerations of qualitative researchers and bring them into a more open and transparent dialogue about assessing qualitative research in techno-scientific, academic, sociocultural, and political rooms.

Frequent debates on the use of evaluative criteria are required to solve some potentially resolved issues (including the applicability of a single set of criteria in multi-disciplinary aspects). Such debates would not only benefit the group of qualitative researchers themselves, but primarily assist in augmenting the well-being and vivacity of the entire discipline.

To conclude, I speculate that the criteria, and my perspective, may transfer to other methods, approaches, and contexts. I hope that they spark dialog and debate – about criteria for excellent qualitative research and the underpinnings of the discipline more broadly – and, therefore, help improve the quality of a qualitative study. Further, I anticipate that this review will assist the researchers to contemplate on the quality of their own research, to substantiate research design and help the reviewers to review qualitative research for journals. On a final note, I pinpoint the need to formulate a framework (encompassing the prerequisites of a qualitative study) by the cohesive efforts of qualitative researchers of different disciplines with different theoretic-paradigmatic origins. I believe that tailoring such a framework (of guiding principles) paves the way for qualitative researchers to consolidate the status of qualitative research in the wide-ranging open science debate. Dialogue on this issue across different approaches is crucial for the impending prospects of socio-techno-educational research.

Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16 (10), 1472–1482.

Article Google Scholar

Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (3–4), 201–212.

Bryman, A., Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 261–276.

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2 (2), 1–13.

CASP (2021). CASP checklists. Retrieved May 2021 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6 (4), 331–339.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd.

Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Epp, A. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2021). High-quality qualitative research: Getting into gear. Journal of Service Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520961445

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. In Alternative paradigms conference, mar, 1989, Indiana u, school of education, San Francisco, ca, us . Sage Publications, Inc.

Hammersley, M. (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 30 (3), 287–305.

Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A Delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406920976417.

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99 (2), 178–188.

Horsburgh, D. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12 (2), 307–312.

Howe, K. R. (2004). A critique of experimentalism. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 42–46.

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84 (1), 7120.

Johnson, P., Buehring, A., Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2006). Evaluating qualitative management research: Towards a contingent criteriology. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8 (3), 131–156.

Klein, H. K., & Myers, M. D. (1999). A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 23 (1), 67–93.

Lather, P. (2004). This is your father’s paradigm: Government intrusion and the case of qualitative research in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 15–34.

Levitt, H. M., Morrill, Z., Collins, K. M., & Rizo, J. L. (2021). The methodological integrity of critical qualitative research: Principles to support design and research review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68 (3), 357.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986 (30), 73–84.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 163–188). Sage Publications.

Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91 (1), 1–20.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2020). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Health Care . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867.ch15

McGinley, S., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The state of qualitative research in hospitality: A 5-year review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62 (1), 8–20.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, US.

Meyer, M., & Dykes, J. (2019). Criteria for rigor in visualization design study. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 26 (1), 87–97.

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2020). When I say… quantification in qualitative research. Medical Education, 54 (3), 186–187.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 250.

Morse, J. M. (2003). A review committee’s guide for evaluating qualitative proposals. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (6), 833–851.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24 (4), 427–431.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406919899220.

Reid, A., & Gough, S. (2000). Guidelines for reporting and evaluating qualitative research: What are the alternatives? Environmental Education Research, 6 (1), 59–91.

Rocco, T. S. (2010). Criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. Human Resource Development International . https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2010.501959

Sandberg, J. (2000). Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (1), 9–25.

Schwandt, T. A. (1996). Farewell to criteriology. Qualitative Inquiry, 2 (1), 58–72.

Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (4), 465–478.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 (2), 63–75.

Sparkes, A. C. (2001). Myth 94: Qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qualitative Health Research, 11 (4), 538–552.

Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2004). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence.

Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17 (6), 596–599.

Taylor, E. W., Beck, J., & Ainsworth, E. (2001). Publishing qualitative adult education research: A peer review perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 33 (2), 163–179.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19 (6), 349–357.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16 (10), 837–851.

Download references

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Informatics, Technische Universität Wien, 1040, Vienna, Austria

Drishti Yadav

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Drishti Yadav .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yadav, D. Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31 , 679–689 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Download citation

Accepted : 28 August 2021

Published : 18 September 2021

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Evaluative criteria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Chapter 2. Research Design

Getting started.

When I teach undergraduates qualitative research methods, the final product of the course is a “research proposal” that incorporates all they have learned and enlists the knowledge they have learned about qualitative research methods in an original design that addresses a particular research question. I highly recommend you think about designing your own research study as you progress through this textbook. Even if you don’t have a study in mind yet, it can be a helpful exercise as you progress through the course. But how to start? How can one design a research study before they even know what research looks like? This chapter will serve as a brief overview of the research design process to orient you to what will be coming in later chapters. Think of it as a “skeleton” of what you will read in more detail in later chapters. Ideally, you will read this chapter both now (in sequence) and later during your reading of the remainder of the text. Do not worry if you have questions the first time you read this chapter. Many things will become clearer as the text advances and as you gain a deeper understanding of all the components of good qualitative research. This is just a preliminary map to get you on the right road.

Research Design Steps

Before you even get started, you will need to have a broad topic of interest in mind. [1] . In my experience, students can confuse this broad topic with the actual research question, so it is important to clearly distinguish the two. And the place to start is the broad topic. It might be, as was the case with me, working-class college students. But what about working-class college students? What’s it like to be one? Why are there so few compared to others? How do colleges assist (or fail to assist) them? What interested me was something I could barely articulate at first and went something like this: “Why was it so difficult and lonely to be me?” And by extension, “Did others share this experience?”

Once you have a general topic, reflect on why this is important to you. Sometimes we connect with a topic and we don’t really know why. Even if you are not willing to share the real underlying reason you are interested in a topic, it is important that you know the deeper reasons that motivate you. Otherwise, it is quite possible that at some point during the research, you will find yourself turned around facing the wrong direction. I have seen it happen many times. The reason is that the research question is not the same thing as the general topic of interest, and if you don’t know the reasons for your interest, you are likely to design a study answering a research question that is beside the point—to you, at least. And this means you will be much less motivated to carry your research to completion.

Researcher Note

Why do you employ qualitative research methods in your area of study? What are the advantages of qualitative research methods for studying mentorship?

Qualitative research methods are a huge opportunity to increase access, equity, inclusion, and social justice. Qualitative research allows us to engage and examine the uniquenesses/nuances within minoritized and dominant identities and our experiences with these identities. Qualitative research allows us to explore a specific topic, and through that exploration, we can link history to experiences and look for patterns or offer up a unique phenomenon. There’s such beauty in being able to tell a particular story, and qualitative research is a great mode for that! For our work, we examined the relationships we typically use the term mentorship for but didn’t feel that was quite the right word. Qualitative research allowed us to pick apart what we did and how we engaged in our relationships, which then allowed us to more accurately describe what was unique about our mentorship relationships, which we ultimately named liberationships ( McAloney and Long 2021) . Qualitative research gave us the means to explore, process, and name our experiences; what a powerful tool!

How do you come up with ideas for what to study (and how to study it)? Where did you get the idea for studying mentorship?

Coming up with ideas for research, for me, is kind of like Googling a question I have, not finding enough information, and then deciding to dig a little deeper to get the answer. The idea to study mentorship actually came up in conversation with my mentorship triad. We were talking in one of our meetings about our relationship—kind of meta, huh? We discussed how we felt that mentorship was not quite the right term for the relationships we had built. One of us asked what was different about our relationships and mentorship. This all happened when I was taking an ethnography course. During the next session of class, we were discussing auto- and duoethnography, and it hit me—let’s explore our version of mentorship, which we later went on to name liberationships ( McAloney and Long 2021 ). The idea and questions came out of being curious and wanting to find an answer. As I continue to research, I see opportunities in questions I have about my work or during conversations that, in our search for answers, end up exposing gaps in the literature. If I can’t find the answer already out there, I can study it.

—Kim McAloney, PhD, College Student Services Administration Ecampus coordinator and instructor

When you have a better idea of why you are interested in what it is that interests you, you may be surprised to learn that the obvious approaches to the topic are not the only ones. For example, let’s say you think you are interested in preserving coastal wildlife. And as a social scientist, you are interested in policies and practices that affect the long-term viability of coastal wildlife, especially around fishing communities. It would be natural then to consider designing a research study around fishing communities and how they manage their ecosystems. But when you really think about it, you realize that what interests you the most is how people whose livelihoods depend on a particular resource act in ways that deplete that resource. Or, even deeper, you contemplate the puzzle, “How do people justify actions that damage their surroundings?” Now, there are many ways to design a study that gets at that broader question, and not all of them are about fishing communities, although that is certainly one way to go. Maybe you could design an interview-based study that includes and compares loggers, fishers, and desert golfers (those who golf in arid lands that require a great deal of wasteful irrigation). Or design a case study around one particular example where resources were completely used up by a community. Without knowing what it is you are really interested in, what motivates your interest in a surface phenomenon, you are unlikely to come up with the appropriate research design.

These first stages of research design are often the most difficult, but have patience . Taking the time to consider why you are going to go through a lot of trouble to get answers will prevent a lot of wasted energy in the future.

There are distinct reasons for pursuing particular research questions, and it is helpful to distinguish between them. First, you may be personally motivated. This is probably the most important and the most often overlooked. What is it about the social world that sparks your curiosity? What bothers you? What answers do you need in order to keep living? For me, I knew I needed to get a handle on what higher education was for before I kept going at it. I needed to understand why I felt so different from my peers and whether this whole “higher education” thing was “for the likes of me” before I could complete my degree. That is the personal motivation question. Your personal motivation might also be political in nature, in that you want to change the world in a particular way. It’s all right to acknowledge this. In fact, it is better to acknowledge it than to hide it.

There are also academic and professional motivations for a particular study. If you are an absolute beginner, these may be difficult to find. We’ll talk more about this when we discuss reviewing the literature. Simply put, you are probably not the only person in the world to have thought about this question or issue and those related to it. So how does your interest area fit into what others have studied? Perhaps there is a good study out there of fishing communities, but no one has quite asked the “justification” question. You are motivated to address this to “fill the gap” in our collective knowledge. And maybe you are really not at all sure of what interests you, but you do know that [insert your topic] interests a lot of people, so you would like to work in this area too. You want to be involved in the academic conversation. That is a professional motivation and a very important one to articulate.

Practical and strategic motivations are a third kind. Perhaps you want to encourage people to take better care of the natural resources around them. If this is also part of your motivation, you will want to design your research project in a way that might have an impact on how people behave in the future. There are many ways to do this, one of which is using qualitative research methods rather than quantitative research methods, as the findings of qualitative research are often easier to communicate to a broader audience than the results of quantitative research. You might even be able to engage the community you are studying in the collecting and analyzing of data, something taboo in quantitative research but actively embraced and encouraged by qualitative researchers. But there are other practical reasons, such as getting “done” with your research in a certain amount of time or having access (or no access) to certain information. There is nothing wrong with considering constraints and opportunities when designing your study. Or maybe one of the practical or strategic goals is about learning competence in this area so that you can demonstrate the ability to conduct interviews and focus groups with future employers. Keeping that in mind will help shape your study and prevent you from getting sidetracked using a technique that you are less invested in learning about.

STOP HERE for a moment

I recommend you write a paragraph (at least) explaining your aims and goals. Include a sentence about each of the following: personal/political goals, practical or professional/academic goals, and practical/strategic goals. Think through how all of the goals are related and can be achieved by this particular research study . If they can’t, have a rethink. Perhaps this is not the best way to go about it.

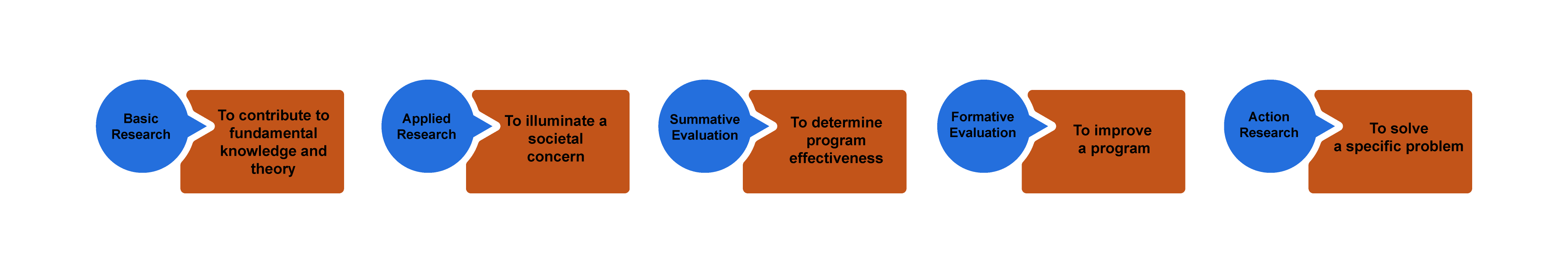

You will also want to be clear about the purpose of your study. “Wait, didn’t we just do this?” you might ask. No! Your goals are not the same as the purpose of the study, although they are related. You can think about purpose lying on a continuum from “ theory ” to “action” (figure 2.1). Sometimes you are doing research to discover new knowledge about the world, while other times you are doing a study because you want to measure an impact or make a difference in the world.

Basic research involves research that is done for the sake of “pure” knowledge—that is, knowledge that, at least at this moment in time, may not have any apparent use or application. Often, and this is very important, knowledge of this kind is later found to be extremely helpful in solving problems. So one way of thinking about basic research is that it is knowledge for which no use is yet known but will probably one day prove to be extremely useful. If you are doing basic research, you do not need to argue its usefulness, as the whole point is that we just don’t know yet what this might be.

Researchers engaged in basic research want to understand how the world operates. They are interested in investigating a phenomenon to get at the nature of reality with regard to that phenomenon. The basic researcher’s purpose is to understand and explain ( Patton 2002:215 ).

Basic research is interested in generating and testing hypotheses about how the world works. Grounded Theory is one approach to qualitative research methods that exemplifies basic research (see chapter 4). Most academic journal articles publish basic research findings. If you are working in academia (e.g., writing your dissertation), the default expectation is that you are conducting basic research.

Applied research in the social sciences is research that addresses human and social problems. Unlike basic research, the researcher has expectations that the research will help contribute to resolving a problem, if only by identifying its contours, history, or context. From my experience, most students have this as their baseline assumption about research. Why do a study if not to make things better? But this is a common mistake. Students and their committee members are often working with default assumptions here—the former thinking about applied research as their purpose, the latter thinking about basic research: “The purpose of applied research is to contribute knowledge that will help people to understand the nature of a problem in order to intervene, thereby allowing human beings to more effectively control their environment. While in basic research the source of questions is the tradition within a scholarly discipline, in applied research the source of questions is in the problems and concerns experienced by people and by policymakers” ( Patton 2002:217 ).

Applied research is less geared toward theory in two ways. First, its questions do not derive from previous literature. For this reason, applied research studies have much more limited literature reviews than those found in basic research (although they make up for this by having much more “background” about the problem). Second, it does not generate theory in the same way as basic research does. The findings of an applied research project may not be generalizable beyond the boundaries of this particular problem or context. The findings are more limited. They are useful now but may be less useful later. This is why basic research remains the default “gold standard” of academic research.

Evaluation research is research that is designed to evaluate or test the effectiveness of specific solutions and programs addressing specific social problems. We already know the problems, and someone has already come up with solutions. There might be a program, say, for first-generation college students on your campus. Does this program work? Are first-generation students who participate in the program more likely to graduate than those who do not? These are the types of questions addressed by evaluation research. There are two types of research within this broader frame; however, one more action-oriented than the next. In summative evaluation , an overall judgment about the effectiveness of a program or policy is made. Should we continue our first-gen program? Is it a good model for other campuses? Because the purpose of such summative evaluation is to measure success and to determine whether this success is scalable (capable of being generalized beyond the specific case), quantitative data is more often used than qualitative data. In our example, we might have “outcomes” data for thousands of students, and we might run various tests to determine if the better outcomes of those in the program are statistically significant so that we can generalize the findings and recommend similar programs elsewhere. Qualitative data in the form of focus groups or interviews can then be used for illustrative purposes, providing more depth to the quantitative analyses. In contrast, formative evaluation attempts to improve a program or policy (to help “form” or shape its effectiveness). Formative evaluations rely more heavily on qualitative data—case studies, interviews, focus groups. The findings are meant not to generalize beyond the particular but to improve this program. If you are a student seeking to improve your qualitative research skills and you do not care about generating basic research, formative evaluation studies might be an attractive option for you to pursue, as there are always local programs that need evaluation and suggestions for improvement. Again, be very clear about your purpose when talking through your research proposal with your committee.

Action research takes a further step beyond evaluation, even formative evaluation, to being part of the solution itself. This is about as far from basic research as one could get and definitely falls beyond the scope of “science,” as conventionally defined. The distinction between action and research is blurry, the research methods are often in constant flux, and the only “findings” are specific to the problem or case at hand and often are findings about the process of intervention itself. Rather than evaluate a program as a whole, action research often seeks to change and improve some particular aspect that may not be working—maybe there is not enough diversity in an organization or maybe women’s voices are muted during meetings and the organization wonders why and would like to change this. In a further step, participatory action research , those women would become part of the research team, attempting to amplify their voices in the organization through participation in the action research. As action research employs methods that involve people in the process, focus groups are quite common.

If you are working on a thesis or dissertation, chances are your committee will expect you to be contributing to fundamental knowledge and theory ( basic research ). If your interests lie more toward the action end of the continuum, however, it is helpful to talk to your committee about this before you get started. Knowing your purpose in advance will help avoid misunderstandings during the later stages of the research process!

The Research Question

Once you have written your paragraph and clarified your purpose and truly know that this study is the best study for you to be doing right now , you are ready to write and refine your actual research question. Know that research questions are often moving targets in qualitative research, that they can be refined up to the very end of data collection and analysis. But you do have to have a working research question at all stages. This is your “anchor” when you get lost in the data. What are you addressing? What are you looking at and why? Your research question guides you through the thicket. It is common to have a whole host of questions about a phenomenon or case, both at the outset and throughout the study, but you should be able to pare it down to no more than two or three sentences when asked. These sentences should both clarify the intent of the research and explain why this is an important question to answer. More on refining your research question can be found in chapter 4.

Chances are, you will have already done some prior reading before coming up with your interest and your questions, but you may not have conducted a systematic literature review. This is the next crucial stage to be completed before venturing further. You don’t want to start collecting data and then realize that someone has already beaten you to the punch. A review of the literature that is already out there will let you know (1) if others have already done the study you are envisioning; (2) if others have done similar studies, which can help you out; and (3) what ideas or concepts are out there that can help you frame your study and make sense of your findings. More on literature reviews can be found in chapter 9.

In addition to reviewing the literature for similar studies to what you are proposing, it can be extremely helpful to find a study that inspires you. This may have absolutely nothing to do with the topic you are interested in but is written so beautifully or organized so interestingly or otherwise speaks to you in such a way that you want to post it somewhere to remind you of what you want to be doing. You might not understand this in the early stages—why would you find a study that has nothing to do with the one you are doing helpful? But trust me, when you are deep into analysis and writing, having an inspirational model in view can help you push through. If you are motivated to do something that might change the world, you probably have read something somewhere that inspired you. Go back to that original inspiration and read it carefully and see how they managed to convey the passion that you so appreciate.

At this stage, you are still just getting started. There are a lot of things to do before setting forth to collect data! You’ll want to consider and choose a research tradition and a set of data-collection techniques that both help you answer your research question and match all your aims and goals. For example, if you really want to help migrant workers speak for themselves, you might draw on feminist theory and participatory action research models. Chapters 3 and 4 will provide you with more information on epistemologies and approaches.

Next, you have to clarify your “units of analysis.” What is the level at which you are focusing your study? Often, the unit in qualitative research methods is individual people, or “human subjects.” But your units of analysis could just as well be organizations (colleges, hospitals) or programs or even whole nations. Think about what it is you want to be saying at the end of your study—are the insights you are hoping to make about people or about organizations or about something else entirely? A unit of analysis can even be a historical period! Every unit of analysis will call for a different kind of data collection and analysis and will produce different kinds of “findings” at the conclusion of your study. [2]

Regardless of what unit of analysis you select, you will probably have to consider the “human subjects” involved in your research. [3] Who are they? What interactions will you have with them—that is, what kind of data will you be collecting? Before answering these questions, define your population of interest and your research setting. Use your research question to help guide you.

Let’s use an example from a real study. In Geographies of Campus Inequality , Benson and Lee ( 2020 ) list three related research questions: “(1) What are the different ways that first-generation students organize their social, extracurricular, and academic activities at selective and highly selective colleges? (2) how do first-generation students sort themselves and get sorted into these different types of campus lives; and (3) how do these different patterns of campus engagement prepare first-generation students for their post-college lives?” (3).

Note that we are jumping into this a bit late, after Benson and Lee have described previous studies (the literature review) and what is known about first-generation college students and what is not known. They want to know about differences within this group, and they are interested in ones attending certain kinds of colleges because those colleges will be sites where academic and extracurricular pressures compete. That is the context for their three related research questions. What is the population of interest here? First-generation college students . What is the research setting? Selective and highly selective colleges . But a host of questions remain. Which students in the real world, which colleges? What about gender, race, and other identity markers? Will the students be asked questions? Are the students still in college, or will they be asked about what college was like for them? Will they be observed? Will they be shadowed? Will they be surveyed? Will they be asked to keep diaries of their time in college? How many students? How many colleges? For how long will they be observed?

Recommendation

Take a moment and write down suggestions for Benson and Lee before continuing on to what they actually did.

Have you written down your own suggestions? Good. Now let’s compare those with what they actually did. Benson and Lee drew on two sources of data: in-depth interviews with sixty-four first-generation students and survey data from a preexisting national survey of students at twenty-eight selective colleges. Let’s ignore the survey for our purposes here and focus on those interviews. The interviews were conducted between 2014 and 2016 at a single selective college, “Hilltop” (a pseudonym ). They employed a “purposive” sampling strategy to ensure an equal number of male-identifying and female-identifying students as well as equal numbers of White, Black, and Latinx students. Each student was interviewed once. Hilltop is a selective liberal arts college in the northeast that enrolls about three thousand students.

How did your suggestions match up to those actually used by the researchers in this study? It is possible your suggestions were too ambitious? Beginning qualitative researchers can often make that mistake. You want a research design that is both effective (it matches your question and goals) and doable. You will never be able to collect data from your entire population of interest (unless your research question is really so narrow to be relevant to very few people!), so you will need to come up with a good sample. Define the criteria for this sample, as Benson and Lee did when deciding to interview an equal number of students by gender and race categories. Define the criteria for your sample setting too. Hilltop is typical for selective colleges. That was a research choice made by Benson and Lee. For more on sampling and sampling choices, see chapter 5.

Benson and Lee chose to employ interviews. If you also would like to include interviews, you have to think about what will be asked in them. Most interview-based research involves an interview guide, a set of questions or question areas that will be asked of each participant. The research question helps you create a relevant interview guide. You want to ask questions whose answers will provide insight into your research question. Again, your research question is the anchor you will continually come back to as you plan for and conduct your study. It may be that once you begin interviewing, you find that people are telling you something totally unexpected, and this makes you rethink your research question. That is fine. Then you have a new anchor. But you always have an anchor. More on interviewing can be found in chapter 11.

Let’s imagine Benson and Lee also observed college students as they went about doing the things college students do, both in the classroom and in the clubs and social activities in which they participate. They would have needed a plan for this. Would they sit in on classes? Which ones and how many? Would they attend club meetings and sports events? Which ones and how many? Would they participate themselves? How would they record their observations? More on observation techniques can be found in both chapters 13 and 14.