Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 76, Issue 2

- COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on social relationships and health

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1512-4471 Emily Long 1 ,

- Susan Patterson 1 ,

- Karen Maxwell 1 ,

- Carolyn Blake 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7342-4566 Raquel Bosó Pérez 1 ,

- Ruth Lewis 1 ,

- Mark McCann 1 ,

- Julie Riddell 1 ,

- Kathryn Skivington 1 ,

- Rachel Wilson-Lowe 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4409-6601 Kirstin R Mitchell 2

- 1 MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit , University of Glasgow , Glasgow , UK

- 2 MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, Institute of Health & Wellbeing , University of Glasgow , Glasgow , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Emily Long, MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G3 7HR, UK; emily.long{at}glasgow.ac.uk

This essay examines key aspects of social relationships that were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. It focuses explicitly on relational mechanisms of health and brings together theory and emerging evidence on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic to make recommendations for future public health policy and recovery. We first provide an overview of the pandemic in the UK context, outlining the nature of the public health response. We then introduce four distinct domains of social relationships: social networks, social support, social interaction and intimacy, highlighting the mechanisms through which the pandemic and associated public health response drastically altered social interactions in each domain. Throughout the essay, the lens of health inequalities, and perspective of relationships as interconnecting elements in a broader system, is used to explore the varying impact of these disruptions. The essay concludes by providing recommendations for longer term recovery ensuring that the social relational cost of COVID-19 is adequately considered in efforts to rebuild.

- inequalities

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated and/or analysed for this study. Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated or analysed for this essay.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2021-216690

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Infectious disease pandemics, including SARS and COVID-19, demand intrapersonal behaviour change and present highly complex challenges for public health. 1 A pandemic of an airborne infection, spread easily through social contact, assails human relationships by drastically altering the ways through which humans interact. In this essay, we draw on theories of social relationships to examine specific ways in which relational mechanisms key to health and well-being were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Relational mechanisms refer to the processes between people that lead to change in health outcomes.

At the time of writing, the future surrounding COVID-19 was uncertain. Vaccine programmes were being rolled out in countries that could afford them, but new and more contagious variants of the virus were also being discovered. The recovery journey looked long, with continued disruption to social relationships. The social cost of COVID-19 was only just beginning to emerge, but the mental health impact was already considerable, 2 3 and the inequality of the health burden stark. 4 Knowledge of the epidemiology of COVID-19 accrued rapidly, but evidence of the most effective policy responses remained uncertain.

The initial response to COVID-19 in the UK was reactive and aimed at reducing mortality, with little time to consider the social implications, including for interpersonal and community relationships. The terminology of ‘social distancing’ quickly became entrenched both in public and policy discourse. This equation of physical distance with social distance was regrettable, since only physical proximity causes viral transmission, whereas many forms of social proximity (eg, conversations while walking outdoors) are minimal risk, and are crucial to maintaining relationships supportive of health and well-being.

The aim of this essay is to explore four key relational mechanisms that were impacted by the pandemic and associated restrictions: social networks, social support, social interaction and intimacy. We use relational theories and emerging research on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic response to make three key recommendations: one regarding public health responses; and two regarding social recovery. Our understanding of these mechanisms stems from a ‘systems’ perspective which casts social relationships as interdependent elements within a connected whole. 5

Social networks

Social networks characterise the individuals and social connections that compose a system (such as a workplace, community or society). Social relationships range from spouses and partners, to coworkers, friends and acquaintances. They vary across many dimensions, including, for example, frequency of contact and emotional closeness. Social networks can be understood both in terms of the individuals and relationships that compose the network, as well as the overall network structure (eg, how many of your friends know each other).

Social networks show a tendency towards homophily, or a phenomenon of associating with individuals who are similar to self. 6 This is particularly true for ‘core’ network ties (eg, close friends), while more distant, sometimes called ‘weak’ ties tend to show more diversity. During the height of COVID-19 restrictions, face-to-face interactions were often reduced to core network members, such as partners, family members or, potentially, live-in roommates; some ‘weak’ ties were lost, and interactions became more limited to those closest. Given that peripheral, weaker social ties provide a diversity of resources, opinions and support, 7 COVID-19 likely resulted in networks that were smaller and more homogenous.

Such changes were not inevitable nor necessarily enduring, since social networks are also adaptive and responsive to change, in that a disruption to usual ways of interacting can be replaced by new ways of engaging (eg, Zoom). Yet, important inequalities exist, wherein networks and individual relationships within networks are not equally able to adapt to such changes. For example, individuals with a large number of newly established relationships (eg, university students) may have struggled to transfer these relationships online, resulting in lost contacts and a heightened risk of social isolation. This is consistent with research suggesting that young adults were the most likely to report a worsening of relationships during COVID-19, whereas older adults were the least likely to report a change. 8

Lastly, social connections give rise to emergent properties of social systems, 9 where a community-level phenomenon develops that cannot be attributed to any one member or portion of the network. For example, local area-based networks emerged due to geographic restrictions (eg, stay-at-home orders), resulting in increases in neighbourly support and local volunteering. 10 In fact, research suggests that relationships with neighbours displayed the largest net gain in ratings of relationship quality compared with a range of relationship types (eg, partner, colleague, friend). 8 Much of this was built from spontaneous individual interactions within local communities, which together contributed to the ‘community spirit’ that many experienced. 11 COVID-19 restrictions thus impacted the personal social networks and the structure of the larger networks within the society.

Social support

Social support, referring to the psychological and material resources provided through social interaction, is a critical mechanism through which social relationships benefit health. In fact, social support has been shown to be one of the most important resilience factors in the aftermath of stressful events. 12 In the context of COVID-19, the usual ways in which individuals interact and obtain social support have been severely disrupted.

One such disruption has been to opportunities for spontaneous social interactions. For example, conversations with colleagues in a break room offer an opportunity for socialising beyond one’s core social network, and these peripheral conversations can provide a form of social support. 13 14 A chance conversation may lead to advice helpful to coping with situations or seeking formal help. Thus, the absence of these spontaneous interactions may mean the reduction of indirect support-seeking opportunities. While direct support-seeking behaviour is more effective at eliciting support, it also requires significantly more effort and may be perceived as forceful and burdensome. 15 The shift to homeworking and closure of community venues reduced the number of opportunities for these spontaneous interactions to occur, and has, second, focused them locally. Consequently, individuals whose core networks are located elsewhere, or who live in communities where spontaneous interaction is less likely, have less opportunity to benefit from spontaneous in-person supportive interactions.

However, alongside this disruption, new opportunities to interact and obtain social support have arisen. The surge in community social support during the initial lockdown mirrored that often seen in response to adverse events (eg, natural disasters 16 ). COVID-19 restrictions that confined individuals to their local area also compelled them to focus their in-person efforts locally. Commentators on the initial lockdown in the UK remarked on extraordinary acts of generosity between individuals who belonged to the same community but were unknown to each other. However, research on adverse events also tells us that such community support is not necessarily maintained in the longer term. 16

Meanwhile, online forms of social support are not bound by geography, thus enabling interactions and social support to be received from a wider network of people. Formal online social support spaces (eg, support groups) existed well before COVID-19, but have vastly increased since. While online interactions can increase perceived social support, it is unclear whether remote communication technologies provide an effective substitute from in-person interaction during periods of social distancing. 17 18 It makes intuitive sense that the usefulness of online social support will vary by the type of support offered, degree of social interaction and ‘online communication skills’ of those taking part. Youth workers, for instance, have struggled to keep vulnerable youth engaged in online youth clubs, 19 despite others finding a positive association between amount of digital technology used by individuals during lockdown and perceived social support. 20 Other research has found that more frequent face-to-face contact and phone/video contact both related to lower levels of depression during the time period of March to August 2020, but the negative effect of a lack of contact was greater for those with higher levels of usual sociability. 21 Relatedly, important inequalities in social support exist, such that individuals who occupy more socially disadvantaged positions in society (eg, low socioeconomic status, older people) tend to have less access to social support, 22 potentially exacerbated by COVID-19.

Social and interactional norms

Interactional norms are key relational mechanisms which build trust, belonging and identity within and across groups in a system. Individuals in groups and societies apply meaning by ‘approving, arranging and redefining’ symbols of interaction. 23 A handshake, for instance, is a powerful symbol of trust and equality. Depending on context, not shaking hands may symbolise a failure to extend friendship, or a failure to reach agreement. The norms governing these symbols represent shared values and identity; and mutual understanding of these symbols enables individuals to achieve orderly interactions, establish supportive relationship accountability and connect socially. 24 25

Physical distancing measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 radically altered these norms of interaction, particularly those used to convey trust, affinity, empathy and respect (eg, hugging, physical comforting). 26 As epidemic waves rose and fell, the work to negotiate these norms required intense cognitive effort; previously taken-for-granted interactions were re-examined, factoring in current restriction levels, own and (assumed) others’ vulnerability and tolerance of risk. This created awkwardness, and uncertainty, for example, around how to bring closure to an in-person interaction or convey warmth. The instability in scripted ways of interacting created particular strain for individuals who already struggled to encode and decode interactions with others (eg, those who are deaf or have autism spectrum disorder); difficulties often intensified by mask wearing. 27

Large social gatherings—for example, weddings, school assemblies, sporting events—also present key opportunities for affirming and assimilating interactional norms, building cohesion and shared identity and facilitating cooperation across social groups. 28 Online ‘equivalents’ do not easily support ‘social-bonding’ activities such as singing and dancing, and rarely enable chance/spontaneous one-on-one conversations with peripheral/weaker network ties (see the Social networks section) which can help strengthen bonds across a larger network. The loss of large gatherings to celebrate rites of passage (eg, bar mitzvah, weddings) has additional relational costs since these events are performed by and for communities to reinforce belonging, and to assist in transitioning to new phases of life. 29 The loss of interaction with diverse others via community and large group gatherings also reduces intergroup contact, which may then tend towards more prejudiced outgroup attitudes. While online interaction can go some way to mimicking these interaction norms, there are key differences. A sense of anonymity, and lack of in-person emotional cues, tends to support norms of polarisation and aggression in expressing differences of opinion online. And while online platforms have potential to provide intergroup contact, the tendency of much social media to form homogeneous ‘echo chambers’ can serve to further reduce intergroup contact. 30 31

Intimacy relates to the feeling of emotional connection and closeness with other human beings. Emotional connection, through romantic, friendship or familial relationships, fulfils a basic human need 32 and strongly benefits health, including reduced stress levels, improved mental health, lowered blood pressure and reduced risk of heart disease. 32 33 Intimacy can be fostered through familiarity, feeling understood and feeling accepted by close others. 34

Intimacy via companionship and closeness is fundamental to mental well-being. Positively, the COVID-19 pandemic has offered opportunities for individuals to (re)connect and (re)strengthen close relationships within their household via quality time together, following closure of many usual external social activities. Research suggests that the first full UK lockdown period led to a net gain in the quality of steady relationships at a population level, 35 but amplified existing inequalities in relationship quality. 35 36 For some in single-person households, the absence of a companion became more conspicuous, leading to feelings of loneliness and lower mental well-being. 37 38 Additional pandemic-related relational strain 39 40 resulted, for some, in the initiation or intensification of domestic abuse. 41 42

Physical touch is another key aspect of intimacy, a fundamental human need crucial in maintaining and developing intimacy within close relationships. 34 Restrictions on social interactions severely restricted the number and range of people with whom physical affection was possible. The reduction in opportunity to give and receive affectionate physical touch was not experienced equally. Many of those living alone found themselves completely without physical contact for extended periods. The deprivation of physical touch is evidenced to take a heavy emotional toll. 43 Even in future, once physical expressions of affection can resume, new levels of anxiety over germs may introduce hesitancy into previously fluent blending of physical and verbal intimate social connections. 44

The pandemic also led to shifts in practices and norms around sexual relationship building and maintenance, as individuals adapted and sought alternative ways of enacting sexual intimacy. This too is important, given that intimate sexual activity has known benefits for health. 45 46 Given that social restrictions hinged on reducing household mixing, possibilities for partnered sexual activity were primarily guided by living arrangements. While those in cohabiting relationships could potentially continue as before, those who were single or in non-cohabiting relationships generally had restricted opportunities to maintain their sexual relationships. Pornography consumption and digital partners were reported to increase since lockdown. 47 However, online interactions are qualitatively different from in-person interactions and do not provide the same opportunities for physical intimacy.

Recommendations and conclusions

In the sections above we have outlined the ways in which COVID-19 has impacted social relationships, showing how relational mechanisms key to health have been undermined. While some of the damage might well self-repair after the pandemic, there are opportunities inherent in deliberative efforts to build back in ways that facilitate greater resilience in social and community relationships. We conclude by making three recommendations: one regarding public health responses to the pandemic; and two regarding social recovery.

Recommendation 1: explicitly count the relational cost of public health policies to control the pandemic

Effective handling of a pandemic recognises that social, economic and health concerns are intricately interwoven. It is clear that future research and policy attention must focus on the social consequences. As described above, policies which restrict physical mixing across households carry heavy and unequal relational costs. These include for individuals (eg, loss of intimate touch), dyads (eg, loss of warmth, comfort), networks (eg, restricted access to support) and communities (eg, loss of cohesion and identity). Such costs—and their unequal impact—should not be ignored in short-term efforts to control an epidemic. Some public health responses—restrictions on international holiday travel and highly efficient test and trace systems—have relatively small relational costs and should be prioritised. At a national level, an earlier move to proportionate restrictions, and investment in effective test and trace systems, may help prevent escalation of spread to the point where a national lockdown or tight restrictions became an inevitability. Where policies with relational costs are unavoidable, close attention should be paid to the unequal relational impact for those whose personal circumstances differ from normative assumptions of two adult families. This includes consideration of whether expectations are fair (eg, for those who live alone), whether restrictions on social events are equitable across age group, religious/ethnic groupings and social class, and also to ensure that the language promoted by such policies (eg, households; families) is not exclusionary. 48 49 Forethought to unequal impacts on social relationships should thus be integral to the work of epidemic preparedness teams.

Recommendation 2: intelligently balance online and offline ways of relating

A key ingredient for well-being is ‘getting together’ in a physical sense. This is fundamental to a human need for intimate touch, physical comfort, reinforcing interactional norms and providing practical support. Emerging evidence suggests that online ways of relating cannot simply replace physical interactions. But online interaction has many benefits and for some it offers connections that did not exist previously. In particular, online platforms provide new forms of support for those unable to access offline services because of mobility issues (eg, older people) or because they are geographically isolated from their support community (eg, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) youth). Ultimately, multiple forms of online and offline social interactions are required to meet the needs of varying groups of people (eg, LGBTQ, older people). Future research and practice should aim to establish ways of using offline and online support in complementary and even synergistic ways, rather than veering between them as social restrictions expand and contract. Intelligent balancing of online and offline ways of relating also pertains to future policies on home and flexible working. A decision to switch to wholesale or obligatory homeworking should consider the risk to relational ‘group properties’ of the workplace community and their impact on employees’ well-being, focusing in particular on unequal impacts (eg, new vs established employees). Intelligent blending of online and in-person working is required to achieve flexibility while also nurturing supportive networks at work. Intelligent balance also implies strategies to build digital literacy and minimise digital exclusion, as well as coproducing solutions with intended beneficiaries.

Recommendation 3: build stronger and sustainable localised communities

In balancing offline and online ways of interacting, there is opportunity to capitalise on the potential for more localised, coherent communities due to scaled-down travel, homeworking and local focus that will ideally continue after restrictions end. There are potential economic benefits after the pandemic, such as increased trade as home workers use local resources (eg, coffee shops), but also relational benefits from stronger relationships around the orbit of the home and neighbourhood. Experience from previous crises shows that community volunteer efforts generated early on will wane over time in the absence of deliberate work to maintain them. Adequately funded partnerships between local government, third sector and community groups are required to sustain community assets that began as a direct response to the pandemic. Such partnerships could work to secure green spaces and indoor (non-commercial) meeting spaces that promote community interaction. Green spaces in particular provide a triple benefit in encouraging physical activity and mental health, as well as facilitating social bonding. 50 In building local communities, small community networks—that allow for diversity and break down ingroup/outgroup views—may be more helpful than the concept of ‘support bubbles’, which are exclusionary and less sustainable in the longer term. Rigorously designed intervention and evaluation—taking a systems approach—will be crucial in ensuring scale-up and sustainability.

The dramatic change to social interaction necessitated by efforts to control the spread of COVID-19 created stark challenges but also opportunities. Our essay highlights opportunities for learning, both to ensure the equity and humanity of physical restrictions, and to sustain the salutogenic effects of social relationships going forward. The starting point for capitalising on this learning is recognition of the disruption to relational mechanisms as a key part of the socioeconomic and health impact of the pandemic. In recovery planning, a general rule is that what is good for decreasing health inequalities (such as expanding social protection and public services and pursuing green inclusive growth strategies) 4 will also benefit relationships and safeguard relational mechanisms for future generations. Putting this into action will require political will.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not required.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS)

- Ford T , et al

- Riordan R ,

- Ford J , et al

- Glonti K , et al

- McPherson JM ,

- Smith-Lovin L

- Granovetter MS

- Fancourt D et al

- Stadtfeld C

- Office for Civil Society

- Cook J et al

- Rodriguez-Llanes JM ,

- Guha-Sapir D

- Patulny R et al

- Granovetter M

- Winkeler M ,

- Filipp S-H ,

- Kaniasty K ,

- de Terte I ,

- Guilaran J , et al

- Wright KB ,

- Martin J et al

- Gabbiadini A ,

- Baldissarri C ,

- Durante F , et al

- Sommerlad A ,

- Marston L ,

- Huntley J , et al

- Turner RJ ,

- Bicchieri C

- Brennan G et al

- Watson-Jones RE ,

- Amichai-Hamburger Y ,

- McKenna KYA

- Page-Gould E ,

- Aron A , et al

- Pietromonaco PR ,

- Timmerman GM

- Bradbury-Jones C ,

- Mikocka-Walus A ,

- Klas A , et al

- Marshall L ,

- Steptoe A ,

- Stanley SM ,

- Campbell AM

- ↵ (ONS), O.f.N.S., Domestic abuse during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, England and Wales . Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabuseduringthecoronaviruscovid19pandemicenglandandwales/november2020

- Rosenberg M ,

- Hensel D , et al

- Banerjee D ,

- Bruner DW , et al

- Bavel JJV ,

- Baicker K ,

- Boggio PS , et al

- van Barneveld K ,

- Quinlan M ,

- Kriesler P , et al

- Mitchell R ,

- de Vries S , et al

Twitter @karenmaxSPHSU, @Mark_McCann, @Rwilsonlowe, @KMitchinGlasgow

Contributors EL and KM led on the manuscript conceptualisation, review and editing. SP, KM, CB, RBP, RL, MM, JR, KS and RW-L contributed to drafting and revising the article. All authors assisted in revising the final draft.

Funding The research reported in this publication was supported by the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00022/1, MC_UU_00022/3) and the Chief Scientist Office (SPHSU11, SPHSU14). EL is also supported by MRC Skills Development Fellowship Award (MR/S015078/1). KS and MM are also supported by a Medical Research Council Strategic Award (MC_PC_13027).

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A literature review

Affiliations.

- 1 Medical Research Unit, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia; Tropical Disease Centre, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia; Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Division of Infectious Diseases, AichiCancer Center Hospital, Chikusa-ku Nagoya, Japan. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 3 Department of Family Medicine, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 4 Department of Pulmonology and Respiratory Medicine, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 5 School of Medicine, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 6 Siem Reap Provincial Health Department, Ministry of Health, Siem Reap, Cambodia. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 7 Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Warmadewa University, Denpasar, Indonesia; Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of California, Davis, CA, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 8 Medical Research Unit, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia; Tropical Disease Centre, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia; Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia; Department of Clinical Microbiology, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 9 Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, MI 48109, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 10 Medical Research Unit, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia; Tropical Disease Centre, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia; Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 32340833

- PMCID: PMC7142680

- DOI: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.03.019

In early December 2019, an outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), occurred in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China. On January 30, 2020 the World Health Organization declared the outbreak as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. As of February 14, 2020, 49,053 laboratory-confirmed and 1,381 deaths have been reported globally. Perceived risk of acquiring disease has led many governments to institute a variety of control measures. We conducted a literature review of publicly available information to summarize knowledge about the pathogen and the current epidemic. In this literature review, the causative agent, pathogenesis and immune responses, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment and management of the disease, control and preventions strategies are all reviewed.

Keywords: 2019-nCoV; COVID-19; Novel coronavirus; Outbreak; SARS-CoV-2.

Copyright © 2020 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd.. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

- COVID-19 pandemic and Internal Medicine Units in Italy: a precious effort on the front line. Montagnani A, Pieralli F, Gnerre P, Vertulli C, Manfellotto D; FADOI COVID-19 Observatory Group. Montagnani A, et al. Intern Emerg Med. 2020 Nov;15(8):1595-1597. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02454-5. Epub 2020 Jul 31. Intern Emerg Med. 2020. PMID: 32737837 Free PMC article. No abstract available.

Similar articles

- Initial Public Health Response and Interim Clinical Guidance for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak - United States, December 31, 2019-February 4, 2020. Patel A, Jernigan DB; 2019-nCoV CDC Response Team. Patel A, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Feb 7;69(5):140-146. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6905e1. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020. PMID: 32027631 Free PMC article.

- The First 75 Days of Novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Outbreak: Recent Advances, Prevention, and Treatment. Yan Y, Shin WI, Pang YX, Meng Y, Lai J, You C, Zhao H, Lester E, Wu T, Pang CH. Yan Y, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Mar 30;17(7):2323. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072323. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. PMID: 32235575 Free PMC article. Review.

- COVID-19: The outbreak caused by a new coronavirus. Sifuentes-Rodríguez E, Palacios-Reyes D. Sifuentes-Rodríguez E, et al. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2020;77(2):47-53. doi: 10.24875/BMHIM.20000039. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2020. PMID: 32226003 Review. English.

- The Novel Coronavirus: A Bird's Eye View. Habibzadeh P, Stoneman EK. Habibzadeh P, et al. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2020 Apr;11(2):65-71. doi: 10.15171/ijoem.2020.1921. Epub 2020 Feb 5. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2020. PMID: 32020915 Free PMC article. Review.

- Occupational health responses to COVID-19: What lessons can we learn from SARS? Koh D, Goh HP. Koh D, et al. J Occup Health. 2020 Jan;62(1):e12128. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12128. J Occup Health. 2020. PMID: 32515882 Free PMC article.

- Evaluating the resilience of residential buildings during a pandemic with a sustainable construction approach. Heydari A, Abbasianjahromi H. Heydari A, et al. Heliyon. 2024 May 14;10(10):e31006. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31006. eCollection 2024 May 30. Heliyon. 2024. PMID: 38803988 Free PMC article.

- Network pharmacology, molecular docking, and dynamics analyses to predict the antiviral activity of ginger constituents against coronavirus infection. Samy A, Hassan A, Hegazi NM, Farid M, Elshafei M. Samy A, et al. Sci Rep. 2024 May 27;14(1):12059. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-60721-3. Sci Rep. 2024. PMID: 38802394 Free PMC article.

- Inflammatory Biomarkers for Assessing In-Hospital Mortality Risk in Severe COVID-19-A Retrospective Study. Bimbo-Szuhai E, Botea MO, Romanescu DD, Beiusanu C, Gavrilas GM, Popa GM, Antal D, Bontea MG, Sachelarie L, Macovei IC. Bimbo-Szuhai E, et al. J Pers Med. 2024 May 10;14(5):503. doi: 10.3390/jpm14050503. J Pers Med. 2024. PMID: 38793085 Free PMC article.

- Vascular Alterations Following COVID-19 Infection: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Karakasis P, Nasoufidou A, Sagris M, Fragakis N, Tsioufis K. Karakasis P, et al. Life (Basel). 2024 Apr 24;14(5):545. doi: 10.3390/life14050545. Life (Basel). 2024. PMID: 38792566 Free PMC article. Review.

- Job burnout and its influencing factors among village doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Zhao Z, Li Q, Yang C, Zhang Z, Chen Z, Yin W. Zhao Z, et al. Front Public Health. 2024 Apr 18;12:1388831. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1388831. eCollection 2024. Front Public Health. 2024. PMID: 38699414 Free PMC article.

- Lu H., Stratton C.W., Tang Y.W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020 - PMC - PubMed

- Hui D.S., E I.A., Madani T.A., Ntoumi F., Kock R., Dar O. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health – the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;91:264–266. - PMC - PubMed

- Gorbalenya A.E.A. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: the species and its viruses – a statement of the Coronavirus Study Group. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.07.937862. - DOI

- Burki T.K. Coronavirus in China. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 - PMC - PubMed

- NHS press conference, February 4, 2020. Beijing, China. National Health Commission (NHC) of the People's Republic of China. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/xwbd/202002/235990d202056cfcb202043f202004a202... .

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

- Europe PubMed Central

- PubMed Central

Other Literature Sources

- The Lens - Patent Citations

Research Materials

- NCI CPTC Antibody Characterization Program

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 June 2021

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: an overview of systematic reviews

- Israel Júnior Borges do Nascimento 1 , 2 ,

- Dónal P. O’Mathúna 3 , 4 ,

- Thilo Caspar von Groote 5 ,

- Hebatullah Mohamed Abdulazeem 6 ,

- Ishanka Weerasekara 7 , 8 ,

- Ana Marusic 9 ,

- Livia Puljak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8467-6061 10 ,

- Vinicius Tassoni Civile 11 ,

- Irena Zakarija-Grkovic 9 ,

- Tina Poklepovic Pericic 9 ,

- Alvaro Nagib Atallah 11 ,

- Santino Filoso 12 ,

- Nicola Luigi Bragazzi 13 &

- Milena Soriano Marcolino 1

On behalf of the International Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (InterNetCOVID-19)

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 21 , Article number: 525 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

28 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

Navigating the rapidly growing body of scientific literature on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is challenging, and ongoing critical appraisal of this output is essential. We aimed to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in humans that were available at the beginning of the pandemic.

Nine databases (Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Web of Sciences, PDQ-Evidence, WHO’s Global Research, LILACS, and Epistemonikos) were searched from December 1, 2019, to March 24, 2020. Systematic reviews analyzing primary studies of COVID-19 were included. Two authors independently undertook screening, selection, extraction (data on clinical symptoms, prevalence, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, diagnostic test assessment, laboratory, and radiological findings), and quality assessment (AMSTAR 2). A meta-analysis was performed of the prevalence of clinical outcomes.

Eighteen systematic reviews were included; one was empty (did not identify any relevant study). Using AMSTAR 2, confidence in the results of all 18 reviews was rated as “critically low”. Identified symptoms of COVID-19 were (range values of point estimates): fever (82–95%), cough with or without sputum (58–72%), dyspnea (26–59%), myalgia or muscle fatigue (29–51%), sore throat (10–13%), headache (8–12%) and gastrointestinal complaints (5–9%). Severe symptoms were more common in men. Elevated C-reactive protein and lactate dehydrogenase, and slightly elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferase, were commonly described. Thrombocytopenia and elevated levels of procalcitonin and cardiac troponin I were associated with severe disease. A frequent finding on chest imaging was uni- or bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacity. A single review investigated the impact of medication (chloroquine) but found no verifiable clinical data. All-cause mortality ranged from 0.3 to 13.9%.

Conclusions

In this overview of systematic reviews, we analyzed evidence from the first 18 systematic reviews that were published after the emergence of COVID-19. However, confidence in the results of all reviews was “critically low”. Thus, systematic reviews that were published early on in the pandemic were of questionable usefulness. Even during public health emergencies, studies and systematic reviews should adhere to established methodological standards.

Peer Review reports

The spread of the “Severe Acute Respiratory Coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2), the causal agent of COVID-19, was characterized as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020 and has triggered an international public health emergency [ 1 ]. The numbers of confirmed cases and deaths due to COVID-19 are rapidly escalating, counting in millions [ 2 ], causing massive economic strain, and escalating healthcare and public health expenses [ 3 , 4 ].

The research community has responded by publishing an impressive number of scientific reports related to COVID-19. The world was alerted to the new disease at the beginning of 2020 [ 1 ], and by mid-March 2020, more than 2000 articles had been published on COVID-19 in scholarly journals, with 25% of them containing original data [ 5 ]. The living map of COVID-19 evidence, curated by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), contained more than 40,000 records by February 2021 [ 6 ]. More than 100,000 records on PubMed were labeled as “SARS-CoV-2 literature, sequence, and clinical content” by February 2021 [ 7 ].

Due to publication speed, the research community has voiced concerns regarding the quality and reproducibility of evidence produced during the COVID-19 pandemic, warning of the potential damaging approach of “publish first, retract later” [ 8 ]. It appears that these concerns are not unfounded, as it has been reported that COVID-19 articles were overrepresented in the pool of retracted articles in 2020 [ 9 ]. These concerns about inadequate evidence are of major importance because they can lead to poor clinical practice and inappropriate policies [ 10 ].

Systematic reviews are a cornerstone of today’s evidence-informed decision-making. By synthesizing all relevant evidence regarding a particular topic, systematic reviews reflect the current scientific knowledge. Systematic reviews are considered to be at the highest level in the hierarchy of evidence and should be used to make informed decisions. However, with high numbers of systematic reviews of different scope and methodological quality being published, overviews of multiple systematic reviews that assess their methodological quality are essential [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. An overview of systematic reviews helps identify and organize the literature and highlights areas of priority in decision-making.

In this overview of systematic reviews, we aimed to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in humans that were available at the beginning of the pandemic.

Methodology

Research question.

This overview’s primary objective was to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews that assessed any type of primary clinical data from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Our research question was purposefully broad because we wanted to analyze as many systematic reviews as possible that were available early following the COVID-19 outbreak.

Study design

We conducted an overview of systematic reviews. The idea for this overview originated in a protocol for a systematic review submitted to PROSPERO (CRD42020170623), which indicated a plan to conduct an overview.

Overviews of systematic reviews use explicit and systematic methods for searching and identifying multiple systematic reviews addressing related research questions in the same field to extract and analyze evidence across important outcomes. Overviews of systematic reviews are in principle similar to systematic reviews of interventions, but the unit of analysis is a systematic review [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

We used the overview methodology instead of other evidence synthesis methods to allow us to collate and appraise multiple systematic reviews on this topic, and to extract and analyze their results across relevant topics [ 17 ]. The overview and meta-analysis of systematic reviews allowed us to investigate the methodological quality of included studies, summarize results, and identify specific areas of available or limited evidence, thereby strengthening the current understanding of this novel disease and guiding future research [ 13 ].

A reporting guideline for overviews of reviews is currently under development, i.e., Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR) [ 18 ]. As the PRIOR checklist is still not published, this study was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 statement [ 19 ]. The methodology used in this review was adapted from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and also followed established methodological considerations for analyzing existing systematic reviews [ 14 ].

Approval of a research ethics committee was not necessary as the study analyzed only publicly available articles.

Eligibility criteria

Systematic reviews were included if they analyzed primary data from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 as confirmed by RT-PCR or another pre-specified diagnostic technique. Eligible reviews covered all topics related to COVID-19 including, but not limited to, those that reported clinical symptoms, diagnostic methods, therapeutic interventions, laboratory findings, or radiological results. Both full manuscripts and abbreviated versions, such as letters, were eligible.

No restrictions were imposed on the design of the primary studies included within the systematic reviews, the last search date, whether the review included meta-analyses or language. Reviews related to SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses were eligible, but from those reviews, we analyzed only data related to SARS-CoV-2.

No consensus definition exists for a systematic review [ 20 ], and debates continue about the defining characteristics of a systematic review [ 21 ]. Cochrane’s guidance for overviews of reviews recommends setting pre-established criteria for making decisions around inclusion [ 14 ]. That is supported by a recent scoping review about guidance for overviews of systematic reviews [ 22 ].

Thus, for this study, we defined a systematic review as a research report which searched for primary research studies on a specific topic using an explicit search strategy, had a detailed description of the methods with explicit inclusion criteria provided, and provided a summary of the included studies either in narrative or quantitative format (such as a meta-analysis). Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews were considered eligible for inclusion, with or without meta-analysis, and regardless of the study design, language restriction and methodology of the included primary studies. To be eligible for inclusion, reviews had to be clearly analyzing data related to SARS-CoV-2 (associated or not with other viruses). We excluded narrative reviews without those characteristics as these are less likely to be replicable and are more prone to bias.

Scoping reviews and rapid reviews were eligible for inclusion in this overview if they met our pre-defined inclusion criteria noted above. We included reviews that addressed SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses if they reported separate data regarding SARS-CoV-2.

Information sources

Nine databases were searched for eligible records published between December 1, 2019, and March 24, 2020: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews via Cochrane Library, PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Web of Sciences, LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature), PDQ-Evidence, WHO’s Global Research on Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), and Epistemonikos.

The comprehensive search strategy for each database is provided in Additional file 1 and was designed and conducted in collaboration with an information specialist. All retrieved records were primarily processed in EndNote, where duplicates were removed, and records were then imported into the Covidence platform [ 23 ]. In addition to database searches, we screened reference lists of reviews included after screening records retrieved via databases.

Study selection

All searches, screening of titles and abstracts, and record selection, were performed independently by two investigators using the Covidence platform [ 23 ]. Articles deemed potentially eligible were retrieved for full-text screening carried out independently by two investigators. Discrepancies at all stages were resolved by consensus. During the screening, records published in languages other than English were translated by a native/fluent speaker.

Data collection process

We custom designed a data extraction table for this study, which was piloted by two authors independently. Data extraction was performed independently by two authors. Conflicts were resolved by consensus or by consulting a third researcher.

We extracted the following data: article identification data (authors’ name and journal of publication), search period, number of databases searched, population or settings considered, main results and outcomes observed, and number of participants. From Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), we extracted journal rank (quartile) and Journal Impact Factor (JIF).

We categorized the following as primary outcomes: all-cause mortality, need for and length of mechanical ventilation, length of hospitalization (in days), admission to intensive care unit (yes/no), and length of stay in the intensive care unit.

The following outcomes were categorized as exploratory: diagnostic methods used for detection of the virus, male to female ratio, clinical symptoms, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, laboratory findings (full blood count, liver enzymes, C-reactive protein, d-dimer, albumin, lipid profile, serum electrolytes, blood vitamin levels, glucose levels, and any other important biomarkers), and radiological findings (using radiography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasound).

We also collected data on reporting guidelines and requirements for the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses from journal websites where included reviews were published.

Quality assessment in individual reviews

Two researchers independently assessed the reviews’ quality using the “A MeaSurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR 2)”. We acknowledge that the AMSTAR 2 was created as “a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomized or non-randomized studies of healthcare interventions, or both” [ 24 ]. However, since AMSTAR 2 was designed for systematic reviews of intervention trials, and we included additional types of systematic reviews, we adjusted some AMSTAR 2 ratings and reported these in Additional file 2 .

Adherence to each item was rated as follows: yes, partial yes, no, or not applicable (such as when a meta-analysis was not conducted). The overall confidence in the results of the review is rated as “critically low”, “low”, “moderate” or “high”, according to the AMSTAR 2 guidance based on seven critical domains, which are items 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 as defined by AMSTAR 2 authors [ 24 ]. We reported our adherence ratings for transparency of our decision with accompanying explanations, for each item, in each included review.

One of the included systematic reviews was conducted by some members of this author team [ 25 ]. This review was initially assessed independently by two authors who were not co-authors of that review to prevent the risk of bias in assessing this study.

Synthesis of results

For data synthesis, we prepared a table summarizing each systematic review. Graphs illustrating the mortality rate and clinical symptoms were created. We then prepared a narrative summary of the methods, findings, study strengths, and limitations.

For analysis of the prevalence of clinical outcomes, we extracted data on the number of events and the total number of patients to perform proportional meta-analysis using RStudio© software, with the “meta” package (version 4.9–6), using the “metaprop” function for reviews that did not perform a meta-analysis, excluding case studies because of the absence of variance. For reviews that did not perform a meta-analysis, we presented pooled results of proportions with their respective confidence intervals (95%) by the inverse variance method with a random-effects model, using the DerSimonian-Laird estimator for τ 2 . We adjusted data using Freeman-Tukey double arcosen transformation. Confidence intervals were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method for individual studies. We created forest plots using the RStudio© software, with the “metafor” package (version 2.1–0) and “forest” function.

Managing overlapping systematic reviews

Some of the included systematic reviews that address the same or similar research questions may include the same primary studies in overviews. Including such overlapping reviews may introduce bias when outcome data from the same primary study are included in the analyses of an overview multiple times. Thus, in summaries of evidence, multiple-counting of the same outcome data will give data from some primary studies too much influence [ 14 ]. In this overview, we did not exclude overlapping systematic reviews because, according to Cochrane’s guidance, it may be appropriate to include all relevant reviews’ results if the purpose of the overview is to present and describe the current body of evidence on a topic [ 14 ]. To avoid any bias in summary estimates associated with overlapping reviews, we generated forest plots showing data from individual systematic reviews, but the results were not pooled because some primary studies were included in multiple reviews.

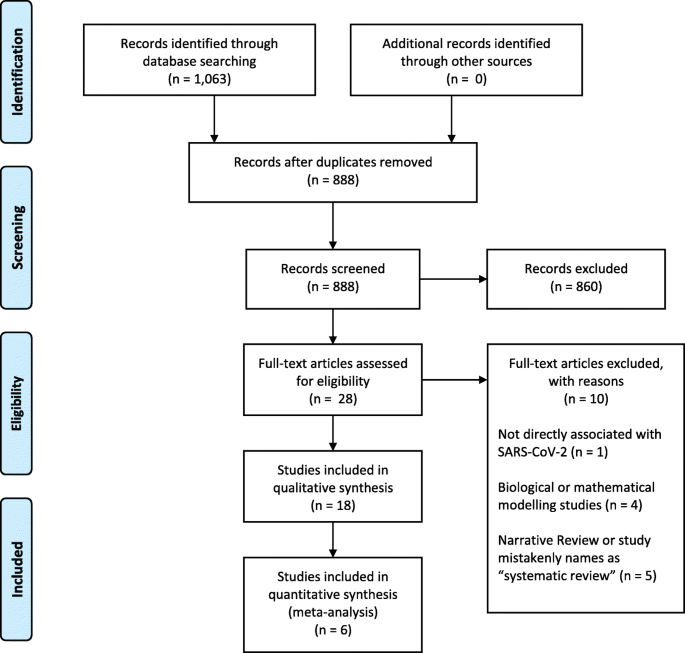

Our search retrieved 1063 publications, of which 175 were duplicates. Most publications were excluded after the title and abstract analysis ( n = 860). Among the 28 studies selected for full-text screening, 10 were excluded for the reasons described in Additional file 3 , and 18 were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1 ) [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Reference list screening did not retrieve any additional systematic reviews.

PRISMA flow diagram

Characteristics of included reviews

Summary features of 18 systematic reviews are presented in Table 1 . They were published in 14 different journals. Only four of these journals had specific requirements for systematic reviews (with or without meta-analysis): European Journal of Internal Medicine, Journal of Clinical Medicine, Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Clinical Research in Cardiology . Two journals reported that they published only invited reviews ( Journal of Medical Virology and Clinica Chimica Acta ). Three systematic reviews in our study were published as letters; one was labeled as a scoping review and another as a rapid review (Table 2 ).

All reviews were published in English, in first quartile (Q1) journals, with JIF ranging from 1.692 to 6.062. One review was empty, meaning that its search did not identify any relevant studies; i.e., no primary studies were included [ 36 ]. The remaining 17 reviews included 269 unique studies; the majority ( N = 211; 78%) were included in only a single review included in our study (range: 1 to 12). Primary studies included in the reviews were published between December 2019 and March 18, 2020, and comprised case reports, case series, cohorts, and other observational studies. We found only one review that included randomized clinical trials [ 38 ]. In the included reviews, systematic literature searches were performed from 2019 (entire year) up to March 9, 2020. Ten systematic reviews included meta-analyses. The list of primary studies found in the included systematic reviews is shown in Additional file 4 , as well as the number of reviews in which each primary study was included.

Population and study designs

Most of the reviews analyzed data from patients with COVID-19 who developed pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), or any other correlated complication. One review aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of using surgical masks on preventing transmission of the virus [ 36 ], one review was focused on pediatric patients [ 34 ], and one review investigated COVID-19 in pregnant women [ 37 ]. Most reviews assessed clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, or radiological results.

Systematic review findings

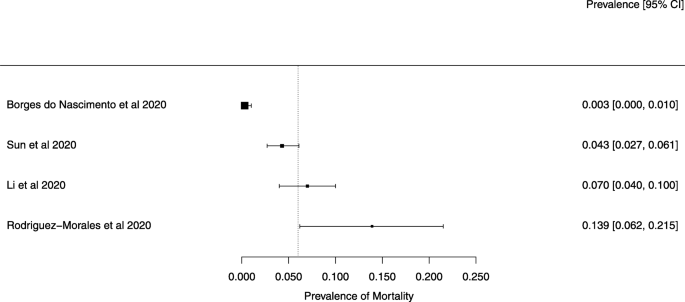

The summary of findings from individual reviews is shown in Table 2 . Overall, all-cause mortality ranged from 0.3 to 13.9% (Fig. 2 ).

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of mortality

Clinical symptoms

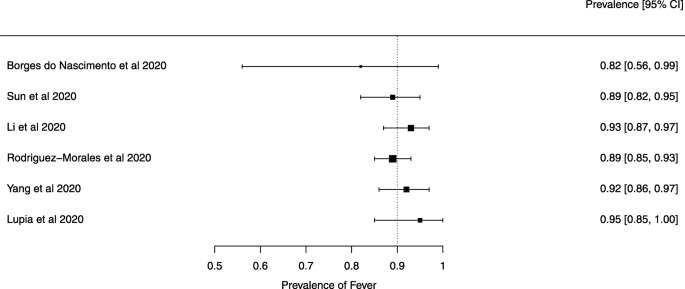

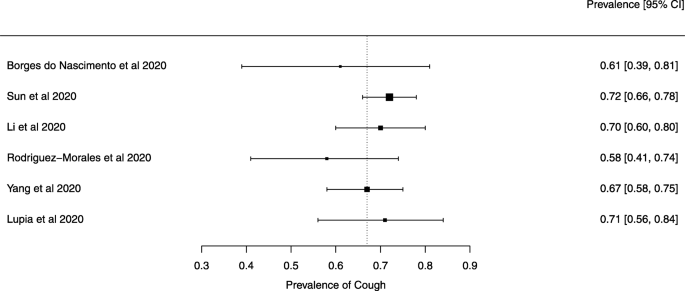

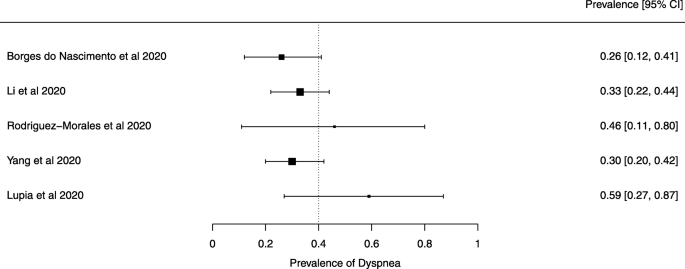

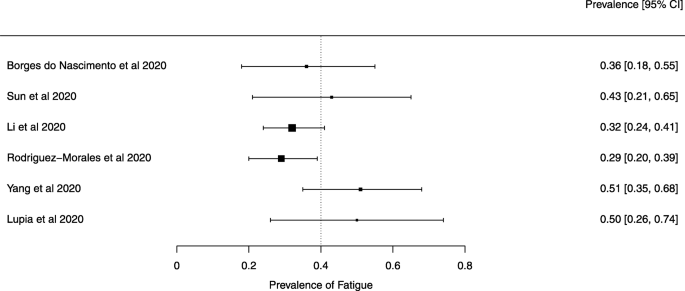

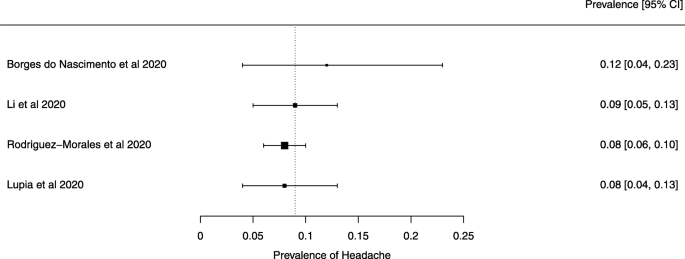

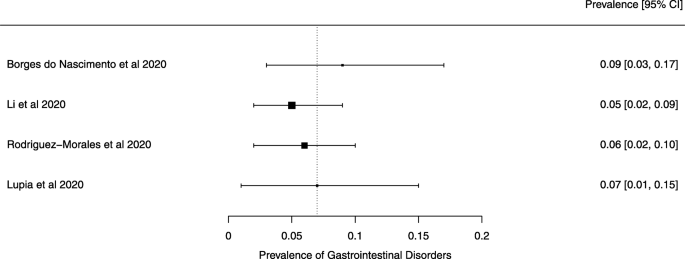

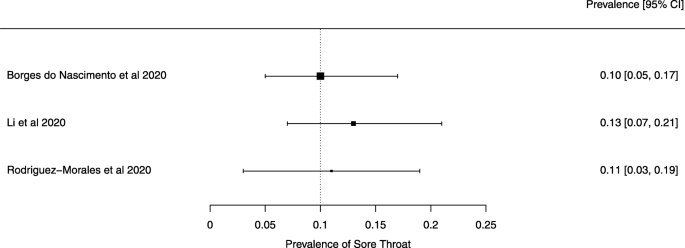

Seven reviews described the main clinical manifestations of COVID-19 [ 26 , 28 , 29 , 34 , 35 , 39 , 41 ]. Three of them provided only a narrative discussion of symptoms [ 26 , 34 , 35 ]. In the reviews that performed a statistical analysis of the incidence of different clinical symptoms, symptoms in patients with COVID-19 were (range values of point estimates): fever (82–95%), cough with or without sputum (58–72%), dyspnea (26–59%), myalgia or muscle fatigue (29–51%), sore throat (10–13%), headache (8–12%), gastrointestinal disorders, such as diarrhea, nausea or vomiting (5.0–9.0%), and others (including, in one study only: dizziness 12.1%) (Figs. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 and 9 ). Three reviews assessed cough with and without sputum together; only one review assessed sputum production itself (28.5%).

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of fever

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of cough

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of dyspnea

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of fatigue or myalgia

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of headache

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of gastrointestinal disorders

A meta-analysis of the prevalence of sore throat

Diagnostic aspects

Three reviews described methodologies, protocols, and tools used for establishing the diagnosis of COVID-19 [ 26 , 34 , 38 ]. The use of respiratory swabs (nasal or pharyngeal) or blood specimens to assess the presence of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid using RT-PCR assays was the most commonly used diagnostic method mentioned in the included studies. These diagnostic tests have been widely used, but their precise sensitivity and specificity remain unknown. One review included a Chinese study with clinical diagnosis with no confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection (patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 if they presented with at least two symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, together with laboratory and chest radiography abnormalities) [ 34 ].

Therapeutic possibilities

Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions (supportive therapies) used in treating patients with COVID-19 were reported in five reviews [ 25 , 27 , 34 , 35 , 38 ]. Antivirals used empirically for COVID-19 treatment were reported in seven reviews [ 25 , 27 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 41 ]; most commonly used were protease inhibitors (lopinavir, ritonavir, darunavir), nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (tenofovir), nucleotide analogs (remdesivir, galidesivir, ganciclovir), and neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir). Umifenovir, a membrane fusion inhibitor, was investigated in two studies [ 25 , 35 ]. Possible supportive interventions analyzed were different types of oxygen supplementation and breathing support (invasive or non-invasive ventilation) [ 25 ]. The use of antibiotics, both empirically and to treat secondary pneumonia, was reported in six studies [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 34 , 35 , 38 ]. One review specifically assessed evidence on the efficacy and safety of the anti-malaria drug chloroquine [ 27 ]. It identified 23 ongoing trials investigating the potential of chloroquine as a therapeutic option for COVID-19, but no verifiable clinical outcomes data. The use of mesenchymal stem cells, antifungals, and glucocorticoids were described in four reviews [ 25 , 34 , 35 , 38 ].

Laboratory and radiological findings

Of the 18 reviews included in this overview, eight analyzed laboratory parameters in patients with COVID-19 [ 25 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 39 ]; elevated C-reactive protein levels, associated with lymphocytopenia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, as well as slightly elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferase (AST, ALT) were commonly described in those eight reviews. Lippi et al. assessed cardiac troponin I (cTnI) [ 25 ], procalcitonin [ 32 ], and platelet count [ 33 ] in COVID-19 patients. Elevated levels of procalcitonin [ 32 ] and cTnI [ 30 ] were more likely to be associated with a severe disease course (requiring intensive care unit admission and intubation). Furthermore, thrombocytopenia was frequently observed in patients with complicated COVID-19 infections [ 33 ].

Chest imaging (chest radiography and/or computed tomography) features were assessed in six reviews, all of which described a frequent pattern of local or bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacity [ 25 , 34 , 35 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]. Those six reviews showed that septal thickening, bronchiectasis, pleural and cardiac effusions, halo signs, and pneumothorax were observed in patients suffering from COVID-19.

Quality of evidence in individual systematic reviews

Table 3 shows the detailed results of the quality assessment of 18 systematic reviews, including the assessment of individual items and summary assessment. A detailed explanation for each decision in each review is available in Additional file 5 .

Using AMSTAR 2 criteria, confidence in the results of all 18 reviews was rated as “critically low” (Table 3 ). Common methodological drawbacks were: omission of prospective protocol submission or publication; use of inappropriate search strategy: lack of independent and dual literature screening and data-extraction (or methodology unclear); absence of an explanation for heterogeneity among the studies included; lack of reasons for study exclusion (or rationale unclear).

Risk of bias assessment, based on a reported methodological tool, and quality of evidence appraisal, in line with the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) method, were reported only in one review [ 25 ]. Five reviews presented a table summarizing bias, using various risk of bias tools [ 25 , 29 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]. One review analyzed “study quality” [ 37 ]. One review mentioned the risk of bias assessment in the methodology but did not provide any related analysis [ 28 ].

This overview of systematic reviews analyzed the first 18 systematic reviews published after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, up to March 24, 2020, with primary studies involving more than 60,000 patients. Using AMSTAR-2, we judged that our confidence in all those reviews was “critically low”. Ten reviews included meta-analyses. The reviews presented data on clinical manifestations, laboratory and radiological findings, and interventions. We found no systematic reviews on the utility of diagnostic tests.

Symptoms were reported in seven reviews; most of the patients had a fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia or muscle fatigue, and gastrointestinal disorders such as diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting. Olfactory dysfunction (anosmia or dysosmia) has been described in patients infected with COVID-19 [ 43 ]; however, this was not reported in any of the reviews included in this overview. During the SARS outbreak in 2002, there were reports of impairment of the sense of smell associated with the disease [ 44 , 45 ].

The reported mortality rates ranged from 0.3 to 14% in the included reviews. Mortality estimates are influenced by the transmissibility rate (basic reproduction number), availability of diagnostic tools, notification policies, asymptomatic presentations of the disease, resources for disease prevention and control, and treatment facilities; variability in the mortality rate fits the pattern of emerging infectious diseases [ 46 ]. Furthermore, the reported cases did not consider asymptomatic cases, mild cases where individuals have not sought medical treatment, and the fact that many countries had limited access to diagnostic tests or have implemented testing policies later than the others. Considering the lack of reviews assessing diagnostic testing (sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of RT-PCT or immunoglobulin tests), and the preponderance of studies that assessed only symptomatic individuals, considerable imprecision around the calculated mortality rates existed in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Few reviews included treatment data. Those reviews described studies considered to be at a very low level of evidence: usually small, retrospective studies with very heterogeneous populations. Seven reviews analyzed laboratory parameters; those reviews could have been useful for clinicians who attend patients suspected of COVID-19 in emergency services worldwide, such as assessing which patients need to be reassessed more frequently.

All systematic reviews scored poorly on the AMSTAR 2 critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews. Most of the original studies included in the reviews were case series and case reports, impacting the quality of evidence. Such evidence has major implications for clinical practice and the use of these reviews in evidence-based practice and policy. Clinicians, patients, and policymakers can only have the highest confidence in systematic review findings if high-quality systematic review methodologies are employed. The urgent need for information during a pandemic does not justify poor quality reporting.

We acknowledge that there are numerous challenges associated with analyzing COVID-19 data during a pandemic [ 47 ]. High-quality evidence syntheses are needed for decision-making, but each type of evidence syntheses is associated with its inherent challenges.

The creation of classic systematic reviews requires considerable time and effort; with massive research output, they quickly become outdated, and preparing updated versions also requires considerable time. A recent study showed that updates of non-Cochrane systematic reviews are published a median of 5 years after the publication of the previous version [ 48 ].

Authors may register a review and then abandon it [ 49 ], but the existence of a public record that is not updated may lead other authors to believe that the review is still ongoing. A quarter of Cochrane review protocols remains unpublished as completed systematic reviews 8 years after protocol publication [ 50 ].

Rapid reviews can be used to summarize the evidence, but they involve methodological sacrifices and simplifications to produce information promptly, with inconsistent methodological approaches [ 51 ]. However, rapid reviews are justified in times of public health emergencies, and even Cochrane has resorted to publishing rapid reviews in response to the COVID-19 crisis [ 52 ]. Rapid reviews were eligible for inclusion in this overview, but only one of the 18 reviews included in this study was labeled as a rapid review.

Ideally, COVID-19 evidence would be continually summarized in a series of high-quality living systematic reviews, types of evidence synthesis defined as “ a systematic review which is continually updated, incorporating relevant new evidence as it becomes available ” [ 53 ]. However, conducting living systematic reviews requires considerable resources, calling into question the sustainability of such evidence synthesis over long periods [ 54 ].

Research reports about COVID-19 will contribute to research waste if they are poorly designed, poorly reported, or simply not necessary. In principle, systematic reviews should help reduce research waste as they usually provide recommendations for further research that is needed or may advise that sufficient evidence exists on a particular topic [ 55 ]. However, systematic reviews can also contribute to growing research waste when they are not needed, or poorly conducted and reported. Our present study clearly shows that most of the systematic reviews that were published early on in the COVID-19 pandemic could be categorized as research waste, as our confidence in their results is critically low.

Our study has some limitations. One is that for AMSTAR 2 assessment we relied on information available in publications; we did not attempt to contact study authors for clarifications or additional data. In three reviews, the methodological quality appraisal was challenging because they were published as letters, or labeled as rapid communications. As a result, various details about their review process were not included, leading to AMSTAR 2 questions being answered as “not reported”, resulting in low confidence scores. Full manuscripts might have provided additional information that could have led to higher confidence in the results. In other words, low scores could reflect incomplete reporting, not necessarily low-quality review methods. To make their review available more rapidly and more concisely, the authors may have omitted methodological details. A general issue during a crisis is that speed and completeness must be balanced. However, maintaining high standards requires proper resourcing and commitment to ensure that the users of systematic reviews can have high confidence in the results.

Furthermore, we used adjusted AMSTAR 2 scoring, as the tool was designed for critical appraisal of reviews of interventions. Some reviews may have received lower scores than actually warranted in spite of these adjustments.

Another limitation of our study may be the inclusion of multiple overlapping reviews, as some included reviews included the same primary studies. According to the Cochrane Handbook, including overlapping reviews may be appropriate when the review’s aim is “ to present and describe the current body of systematic review evidence on a topic ” [ 12 ], which was our aim. To avoid bias with summarizing evidence from overlapping reviews, we presented the forest plots without summary estimates. The forest plots serve to inform readers about the effect sizes for outcomes that were reported in each review.

Several authors from this study have contributed to one of the reviews identified [ 25 ]. To reduce the risk of any bias, two authors who did not co-author the review in question initially assessed its quality and limitations.

Finally, we note that the systematic reviews included in our overview may have had issues that our analysis did not identify because we did not analyze their primary studies to verify the accuracy of the data and information they presented. We give two examples to substantiate this possibility. Lovato et al. wrote a commentary on the review of Sun et al. [ 41 ], in which they criticized the authors’ conclusion that sore throat is rare in COVID-19 patients [ 56 ]. Lovato et al. highlighted that multiple studies included in Sun et al. did not accurately describe participants’ clinical presentations, warning that only three studies clearly reported data on sore throat [ 56 ].

In another example, Leung [ 57 ] warned about the review of Li, L.Q. et al. [ 29 ]: “ it is possible that this statistic was computed using overlapped samples, therefore some patients were double counted ”. Li et al. responded to Leung that it is uncertain whether the data overlapped, as they used data from published articles and did not have access to the original data; they also reported that they requested original data and that they plan to re-do their analyses once they receive them; they also urged readers to treat the data with caution [ 58 ]. This points to the evolving nature of evidence during a crisis.

Our study’s strength is that this overview adds to the current knowledge by providing a comprehensive summary of all the evidence synthesis about COVID-19 available early after the onset of the pandemic. This overview followed strict methodological criteria, including a comprehensive and sensitive search strategy and a standard tool for methodological appraisal of systematic reviews.

In conclusion, in this overview of systematic reviews, we analyzed evidence from the first 18 systematic reviews that were published after the emergence of COVID-19. However, confidence in the results of all the reviews was “critically low”. Thus, systematic reviews that were published early on in the pandemic could be categorized as research waste. Even during public health emergencies, studies and systematic reviews should adhere to established methodological standards to provide patients, clinicians, and decision-makers trustworthy evidence.

Availability of data and materials

All data collected and analyzed within this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

World Health Organization. Timeline - COVID-19: Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline . Accessed 1 June 2021.

COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Anzai A, Kobayashi T, Linton NM, Kinoshita R, Hayashi K, Suzuki A, et al. Assessing the Impact of Reduced Travel on Exportation Dynamics of Novel Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19). J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):601.

Chinazzi M, Davis JT, Ajelli M, Gioannini C, Litvinova M, Merler S, et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020;368(6489):395–400. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba9757 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fidahic M, Nujic D, Runjic R, Civljak M, Markotic F, Lovric Makaric Z, et al. Research methodology and characteristics of journal articles with original data, preprint articles and registered clinical trial protocols about COVID-19. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-01047-2 .

EPPI Centre . COVID-19: a living systematic map of the evidence. Available at: http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Projects/DepartmentofHealthandSocialCare/Publishedreviews/COVID-19Livingsystematicmapoftheevidence/tabid/3765/Default.aspx . Accessed 1 June 2021.

NCBI SARS-CoV-2 Resources. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sars-cov-2/ . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Gustot T. Quality and reproducibility during the COVID-19 pandemic. JHEP Rep. 2020;2(4):100141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100141 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kodvanj, I., et al., Publishing of COVID-19 Preprints in Peer-reviewed Journals, Preprinting Trends, Public Discussion and Quality Issues. Preprint article. bioRxiv 2020.11.23.394577; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.23.394577 .

Dobler CC. Poor quality research and clinical practice during COVID-19. Breathe (Sheff). 2020;16(2):200112. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0112-2020 .

Article Google Scholar

Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 2010;7(9):e1000326. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000326 .

Lunny C, Brennan SE, McDonald S, McKenzie JE. Toward a comprehensive evidence map of overview of systematic review methods: paper 1-purpose, eligibility, search and data extraction. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):231. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0617-1 .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane. 2020. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane. 2020; Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Newton AS, Scott SD, Hartling L. The impact of different inclusion decisions on the comprehensiveness and complexity of overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0914-3 .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Newton AS, Scott SD, Hartling L. A decision tool to help researchers make decisions about including systematic reviews in overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0768-8 .

Hunt H, Pollock A, Campbell P, Estcourt L, Brunton G. An introduction to overviews of reviews: planning a relevant research question and objective for an overview. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0695-8 .

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Pieper D, Tricco AC, Gates M, Gates A, et al. Preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews (PRIOR): a protocol for development of a reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):335. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1252-9 .

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e123–30.

Krnic Martinic M, Pieper D, Glatt A, Puljak L. Definition of a systematic review used in overviews of systematic reviews, meta-epidemiological studies and textbooks. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):203. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0855-0 .

Puljak L. If there is only one author or only one database was searched, a study should not be called a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91:4–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.08.002 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gates M, Gates A, Guitard S, Pollock M, Hartling L. Guidance for overviews of reviews continues to accumulate, but important challenges remain: a scoping review. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):254. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01509-0 .

Covidence - systematic review software. Available at: https://www.covidence.org/ . Accessed 1 June 2021.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Borges do Nascimento IJ, et al. Novel Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19) in Humans: A Scoping Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):941.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu YJ, Mao YP, Ye RX, Wang QZ, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x .