Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

Published on August 21, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 18, 2023.

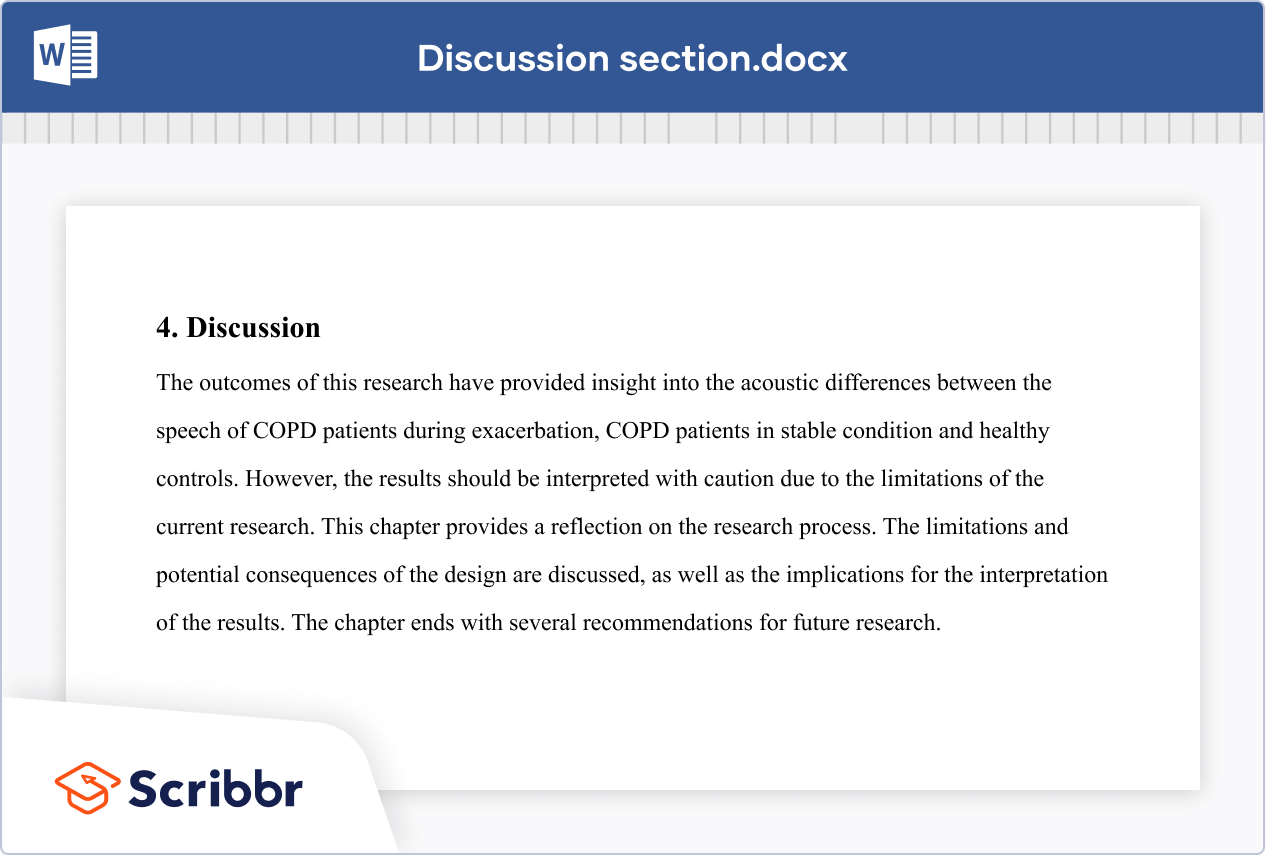

The discussion section is where you delve into the meaning, importance, and relevance of your results .

It should focus on explaining and evaluating what you found, showing how it relates to your literature review and paper or dissertation topic , and making an argument in support of your overall conclusion. It should not be a second results section.

There are different ways to write this section, but you can focus your writing around these key elements:

- Summary : A brief recap of your key results

- Interpretations: What do your results mean?

- Implications: Why do your results matter?

- Limitations: What can’t your results tell us?

- Recommendations: Avenues for further studies or analyses

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What not to include in your discussion section, step 1: summarize your key findings, step 2: give your interpretations, step 3: discuss the implications, step 4: acknowledge the limitations, step 5: share your recommendations, discussion section example, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about discussion sections.

There are a few common mistakes to avoid when writing the discussion section of your paper.

- Don’t introduce new results: You should only discuss the data that you have already reported in your results section .

- Don’t make inflated claims: Avoid overinterpretation and speculation that isn’t directly supported by your data.

- Don’t undermine your research: The discussion of limitations should aim to strengthen your credibility, not emphasize weaknesses or failures.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

Start this section by reiterating your research problem and concisely summarizing your major findings. To speed up the process you can use a summarizer to quickly get an overview of all important findings. Don’t just repeat all the data you have already reported—aim for a clear statement of the overall result that directly answers your main research question . This should be no more than one paragraph.

Many students struggle with the differences between a discussion section and a results section . The crux of the matter is that your results sections should present your results, and your discussion section should subjectively evaluate them. Try not to blend elements of these two sections, in order to keep your paper sharp.

- The results indicate that…

- The study demonstrates a correlation between…

- This analysis supports the theory that…

- The data suggest that…

The meaning of your results may seem obvious to you, but it’s important to spell out their significance for your reader, showing exactly how they answer your research question.

The form of your interpretations will depend on the type of research, but some typical approaches to interpreting the data include:

- Identifying correlations , patterns, and relationships among the data

- Discussing whether the results met your expectations or supported your hypotheses

- Contextualizing your findings within previous research and theory

- Explaining unexpected results and evaluating their significance

- Considering possible alternative explanations and making an argument for your position

You can organize your discussion around key themes, hypotheses, or research questions, following the same structure as your results section. Alternatively, you can also begin by highlighting the most significant or unexpected results.

- In line with the hypothesis…

- Contrary to the hypothesized association…

- The results contradict the claims of Smith (2022) that…

- The results might suggest that x . However, based on the findings of similar studies, a more plausible explanation is y .

As well as giving your own interpretations, make sure to relate your results back to the scholarly work that you surveyed in the literature review . The discussion should show how your findings fit with existing knowledge, what new insights they contribute, and what consequences they have for theory or practice.

Ask yourself these questions:

- Do your results support or challenge existing theories? If they support existing theories, what new information do they contribute? If they challenge existing theories, why do you think that is?

- Are there any practical implications?

Your overall aim is to show the reader exactly what your research has contributed, and why they should care.

- These results build on existing evidence of…

- The results do not fit with the theory that…

- The experiment provides a new insight into the relationship between…

- These results should be taken into account when considering how to…

- The data contribute a clearer understanding of…

- While previous research has focused on x , these results demonstrate that y .

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Even the best research has its limitations. Acknowledging these is important to demonstrate your credibility. Limitations aren’t about listing your errors, but about providing an accurate picture of what can and cannot be concluded from your study.

Limitations might be due to your overall research design, specific methodological choices , or unanticipated obstacles that emerged during your research process.

Here are a few common possibilities:

- If your sample size was small or limited to a specific group of people, explain how generalizability is limited.

- If you encountered problems when gathering or analyzing data, explain how these influenced the results.

- If there are potential confounding variables that you were unable to control, acknowledge the effect these may have had.

After noting the limitations, you can reiterate why the results are nonetheless valid for the purpose of answering your research question.

- The generalizability of the results is limited by…

- The reliability of these data is impacted by…

- Due to the lack of data on x , the results cannot confirm…

- The methodological choices were constrained by…

- It is beyond the scope of this study to…

Based on the discussion of your results, you can make recommendations for practical implementation or further research. Sometimes, the recommendations are saved for the conclusion .

Suggestions for further research can lead directly from the limitations. Don’t just state that more studies should be done—give concrete ideas for how future work can build on areas that your own research was unable to address.

- Further research is needed to establish…

- Future studies should take into account…

- Avenues for future research include…

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

In the discussion , you explore the meaning and relevance of your research results , explaining how they fit with existing research and theory. Discuss:

- Your interpretations : what do the results tell us?

- The implications : why do the results matter?

- The limitation s : what can’t the results tell us?

The results chapter or section simply and objectively reports what you found, without speculating on why you found these results. The discussion interprets the meaning of the results, puts them in context, and explains why they matter.

In qualitative research , results and discussion are sometimes combined. But in quantitative research , it’s considered important to separate the objective results from your interpretation of them.

In a thesis or dissertation, the discussion is an in-depth exploration of the results, going into detail about the meaning of your findings and citing relevant sources to put them in context.

The conclusion is more shorter and more general: it concisely answers your main research question and makes recommendations based on your overall findings.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 18). How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/discussion/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a results section | tips & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

How to Write the Discussion Section of a Research Paper

The discussion section of a research paper analyzes and interprets the findings, provides context, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future research directions.

Updated on September 15, 2023

Structure your discussion section right, and you’ll be cited more often while doing a greater service to the scientific community. So, what actually goes into the discussion section? And how do you write it?

The discussion section of your research paper is where you let the reader know how your study is positioned in the literature, what to take away from your paper, and how your work helps them. It can also include your conclusions and suggestions for future studies.

First, we’ll define all the parts of your discussion paper, and then look into how to write a strong, effective discussion section for your paper or manuscript.

Discussion section: what is it, what it does

The discussion section comes later in your paper, following the introduction, methods, and results. The discussion sets up your study’s conclusions. Its main goals are to present, interpret, and provide a context for your results.

What is it?

The discussion section provides an analysis and interpretation of the findings, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future directions for research.

This section combines information from the preceding parts of your paper into a coherent story. By this point, the reader already knows why you did your study (introduction), how you did it (methods), and what happened (results). In the discussion, you’ll help the reader connect the ideas from these sections.

Why is it necessary?

The discussion provides context and interpretations for the results. It also answers the questions posed in the introduction. While the results section describes your findings, the discussion explains what they say. This is also where you can describe the impact or implications of your research.

Adds context for your results

Most research studies aim to answer a question, replicate a finding, or address limitations in the literature. These goals are first described in the introduction. However, in the discussion section, the author can refer back to them to explain how the study's objective was achieved.

Shows what your results actually mean and real-world implications

The discussion can also describe the effect of your findings on research or practice. How are your results significant for readers, other researchers, or policymakers?

What to include in your discussion (in the correct order)

A complete and effective discussion section should at least touch on the points described below.

Summary of key findings

The discussion should begin with a brief factual summary of the results. Concisely overview the main results you obtained.

Begin with key findings with supporting evidence

Your results section described a list of findings, but what message do they send when you look at them all together?

Your findings were detailed in the results section, so there’s no need to repeat them here, but do provide at least a few highlights. This will help refresh the reader’s memory and help them focus on the big picture.

Read the first paragraph of the discussion section in this article (PDF) for an example of how to start this part of your paper. Notice how the authors break down their results and follow each description sentence with an explanation of why each finding is relevant.

State clearly and concisely

Following a clear and direct writing style is especially important in the discussion section. After all, this is where you will make some of the most impactful points in your paper. While the results section often contains technical vocabulary, such as statistical terms, the discussion section lets you describe your findings more clearly.

Interpretation of results

Once you’ve given your reader an overview of your results, you need to interpret those results. In other words, what do your results mean? Discuss the findings’ implications and significance in relation to your research question or hypothesis.

Analyze and interpret your findings

Look into your findings and explore what’s behind them or what may have caused them. If your introduction cited theories or studies that could explain your findings, use these sources as a basis to discuss your results.

For example, look at the second paragraph in the discussion section of this article on waggling honey bees. Here, the authors explore their results based on information from the literature.

Unexpected or contradictory results

Sometimes, your findings are not what you expect. Here’s where you describe this and try to find a reason for it. Could it be because of the method you used? Does it have something to do with the variables analyzed? Comparing your methods with those of other similar studies can help with this task.

Context and comparison with previous work

Refer to related studies to place your research in a larger context and the literature. Compare and contrast your findings with existing literature, highlighting similarities, differences, and/or contradictions.

How your work compares or contrasts with previous work

Studies with similar findings to yours can be cited to show the strength of your findings. Information from these studies can also be used to help explain your results. Differences between your findings and others in the literature can also be discussed here.

How to divide this section into subsections

If you have more than one objective in your study or many key findings, you can dedicate a separate section to each of these. Here’s an example of this approach. You can see that the discussion section is divided into topics and even has a separate heading for each of them.

Limitations

Many journals require you to include the limitations of your study in the discussion. Even if they don’t, there are good reasons to mention these in your paper.

Why limitations don’t have a negative connotation

A study’s limitations are points to be improved upon in future research. While some of these may be flaws in your method, many may be due to factors you couldn’t predict.

Examples include time constraints or small sample sizes. Pointing this out will help future researchers avoid or address these issues. This part of the discussion can also include any attempts you have made to reduce the impact of these limitations, as in this study .

How limitations add to a researcher's credibility

Pointing out the limitations of your study demonstrates transparency. It also shows that you know your methods well and can conduct a critical assessment of them.

Implications and significance

The final paragraph of the discussion section should contain the take-home messages for your study. It can also cite the “strong points” of your study, to contrast with the limitations section.

Restate your hypothesis

Remind the reader what your hypothesis was before you conducted the study.

How was it proven or disproven?

Identify your main findings and describe how they relate to your hypothesis.

How your results contribute to the literature

Were you able to answer your research question? Or address a gap in the literature?

Future implications of your research

Describe the impact that your results may have on the topic of study. Your results may show, for instance, that there are still limitations in the literature for future studies to address. There may be a need for studies that extend your findings in a specific way. You also may need additional research to corroborate your findings.

Sample discussion section

This fictitious example covers all the aspects discussed above. Your actual discussion section will probably be much longer, but you can read this to get an idea of everything your discussion should cover.

Our results showed that the presence of cats in a household is associated with higher levels of perceived happiness by its human occupants. These findings support our hypothesis and demonstrate the association between pet ownership and well-being.

The present findings align with those of Bao and Schreer (2016) and Hardie et al. (2023), who observed greater life satisfaction in pet owners relative to non-owners. Although the present study did not directly evaluate life satisfaction, this factor may explain the association between happiness and cat ownership observed in our sample.

Our findings must be interpreted in light of some limitations, such as the focus on cat ownership only rather than pets as a whole. This may limit the generalizability of our results.

Nevertheless, this study had several strengths. These include its strict exclusion criteria and use of a standardized assessment instrument to investigate the relationships between pets and owners. These attributes bolster the accuracy of our results and reduce the influence of confounding factors, increasing the strength of our conclusions. Future studies may examine the factors that mediate the association between pet ownership and happiness to better comprehend this phenomenon.

This brief discussion begins with a quick summary of the results and hypothesis. The next paragraph cites previous research and compares its findings to those of this study. Information from previous studies is also used to help interpret the findings. After discussing the results of the study, some limitations are pointed out. The paper also explains why these limitations may influence the interpretation of results. Then, final conclusions are drawn based on the study, and directions for future research are suggested.

How to make your discussion flow naturally

If you find writing in scientific English challenging, the discussion and conclusions are often the hardest parts of the paper to write. That’s because you’re not just listing up studies, methods, and outcomes. You’re actually expressing your thoughts and interpretations in words.

- How formal should it be?

- What words should you use, or not use?

- How do you meet strict word limits, or make it longer and more informative?

Always give it your best, but sometimes a helping hand can, well, help. Getting a professional edit can help clarify your work’s importance while improving the English used to explain it. When readers know the value of your work, they’ll cite it. We’ll assign your study to an expert editor knowledgeable in your area of research. Their work will clarify your discussion, helping it to tell your story. Find out more about AJE Editing.

Adam Goulston, PsyD, MS, MBA, MISD, ELS

Science Marketing Consultant

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

- 4 minute read

- 16.6K views

Table of Contents

The discussion section in scientific manuscripts might be the last few paragraphs, but its role goes far beyond wrapping up. It’s the part of an article where scientists talk about what they found and what it means, where raw data turns into meaningful insights. Therefore, discussion is a vital component of the article.

An excellent discussion is well-organized. We bring to you authors a classic 6-step method for writing discussion sections, with examples to illustrate the functions and specific writing logic of each step. Take a look at how you can impress journal reviewers with a concise and focused discussion section!

Discussion frame structure

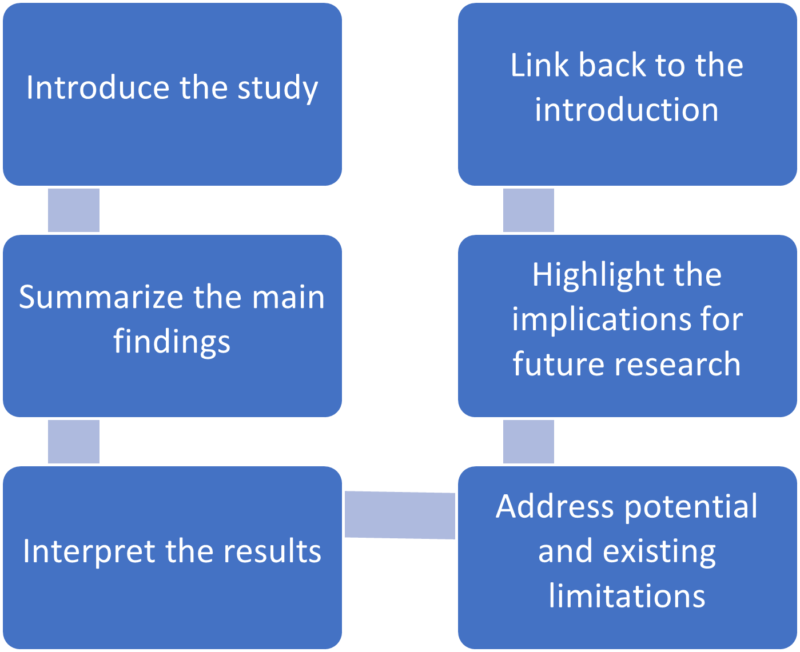

Conventionally, a discussion section has three parts: an introductory paragraph, a few intermediate paragraphs, and a conclusion¹. Please follow the steps below:

1.Introduction—mention gaps in previous research¹⁻ ²

Here, you orient the reader to your study. In the first paragraph, it is advisable to mention the research gap your paper addresses.

Example: This study investigated the cognitive effects of a meat-only diet on adults. While earlier studies have explored the impact of a carnivorous diet on physical attributes and agility, they have not explicitly addressed its influence on cognitively intense tasks involving memory and reasoning.

2. Summarizing key findings—let your data speak ¹⁻ ²

After you have laid out the context for your study, recapitulate some of its key findings. Also, highlight key data and evidence supporting these findings.

Example: We found that risk-taking behavior among teenagers correlates with their tendency to invest in cryptocurrencies. Risk takers in this study, as measured by the Cambridge Gambling Task, tended to have an inordinately higher proportion of their savings invested as crypto coins.

3. Interpreting results—compare with other papers¹⁻²

Here, you must analyze and interpret any results concerning the research question or hypothesis. How do the key findings of your study help verify or disprove the hypothesis? What practical relevance does your discovery have?

Example: Our study suggests that higher daily caffeine intake is not associated with poor performance in major sporting events. Athletes may benefit from the cardiovascular benefits of daily caffeine intake without adversely impacting performance.

Remember, unlike the results section, the discussion ideally focuses on locating your findings in the larger body of existing research. Hence, compare your results with those of other peer-reviewed papers.

Example: Although Miller et al. (2020) found evidence of such political bias in a multicultural population, our findings suggest that the bias is weak or virtually non-existent among politically active citizens.

4. Addressing limitations—their potential impact on the results¹⁻²

Discuss the potential impact of limitations on the results. Most studies have limitations, and it is crucial to acknowledge them in the intermediary paragraphs of the discussion section. Limitations may include low sample size, suspected interference or noise in data, low effect size, etc.

Example: This study explored a comprehensive list of adverse effects associated with the novel drug ‘X’. However, long-term studies may be needed to confirm its safety, especially regarding major cardiac events.

5. Implications for future research—how to explore further¹⁻²

Locate areas of your research where more investigation is needed. Concluding paragraphs of the discussion can explain what research will likely confirm your results or identify knowledge gaps your study left unaddressed.

Example: Our study demonstrates that roads paved with the plastic-infused compound ‘Y’ are more resilient than asphalt. Future studies may explore economically feasible ways of producing compound Y in bulk.

6. Conclusion—summarize content¹⁻²

A good way to wind up the discussion section is by revisiting the research question mentioned in your introduction. Sign off by expressing the main findings of your study.

Example: Recent observations suggest that the fish ‘Z’ is moving upriver in many parts of the Amazon basin. Our findings provide conclusive evidence that this phenomenon is associated with rising sea levels and climate change, not due to elevated numbers of invasive predators.

A rigorous and concise discussion section is one of the keys to achieving an excellent paper. It serves as a critical platform for researchers to interpret and connect their findings with the broader scientific context. By detailing the results, carefully comparing them with existing research, and explaining the limitations of this study, you can effectively help reviewers and readers understand the entire research article more comprehensively and deeply¹⁻² , thereby helping your manuscript to be successfully published and gain wider dissemination.

In addition to keeping this writing guide, you can also use Elsevier Language Services to improve the quality of your paper more deeply and comprehensively. We have a professional editing team covering multiple disciplines. With our profound disciplinary background and rich polishing experience, we can significantly optimize all paper modules including the discussion, effectively improve the fluency and rigor of your articles, and make your scientific research results consistent, with its value reflected more clearly. We are always committed to ensuring the quality of papers according to the standards of top journals, improving the publishing efficiency of scientific researchers, and helping you on the road to academic success. Check us out here !

Type in wordcount for Standard Total: USD EUR JPY Follow this link if your manuscript is longer than 12,000 words. Upload

References:

- Masic, I. (2018). How to write an efficient discussion? Medical Archives , 72(3), 306. https://doi.org/10.5455/medarh.2018.72.306-307

- Şanlı, Ö., Erdem, S., & Tefik, T. (2014). How to write a discussion section? Urology Research & Practice , 39(1), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.5152/tud.2013.049

Navigating “Chinglish” Errors in Academic English Writing

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

You may also like.

Page-Turner Articles are More Than Just Good Arguments: Be Mindful of Tone and Structure!

A Must-see for Researchers! How to Ensure Inclusivity in Your Scientific Writing

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Personalised content for

You're viewing this site as a domestic an international student

You're an international student if you are:

- intending to study on a student visa

- not a citizen of Australia or New Zealand

- not an Australian permanent resident

- not a holder of an Australian humanitarian visa.

You're a domestic student if you are:

- a citizen of Australia or New Zealand

- an Australian permanent resident

- a holder of an Australian humanitarian visa.

- Alumni & Giving

- Current students

Search Charles Darwin University

Study Skills

Writing a discussion section

In the discussion section, you will draw connections between your findings, existing theory and other research. You will have an opportunity to tell the story arising from your findings.

This page will help you to:

understand the purpose of the discussion section

follow the steps required to plan your discussion section

structure your discussion

enhance the depth of your discussion

use appropriate language to discuss your findings.

Introduction to the discussion section

When you have reached this stage, you might be thinking “All I have to do now is to sum up what I have done, and then make a few remarks about what I did” (as cited in Swales & Feak, 2012, p.263). However, writing a discussion section is not that simple. Read on to learn more.

Before you continue, reflect on your earlier writing experiences and the feedback you have received. How would you rate your ability in the following skills? Rate your ability from ‘good’ to ‘needs development’.

Reflect on your answers. Congratulations if you feel confident about your skills. You may find it helpful to review the materials on this page to confirm your knowledge and possibly learn more. Don't worry if you don't feel confident. Work through these materials to build your skills.

A discussion critically analyses and interprets the results of a scientific study, placing the results in the context of published literature and explaining how they affect the field .

In this section, you will relate the specific findings of your research to the wider scientific field. This is the opposite of the introduction section, which starts with the broader context and narrows to focus on your specific research topic.

The discussion will:

review the findings

put the findings into the context of the overall research

tell readers why the research results are important and where they fit in with the current literature

acknowledge the limitations of the study

make recommendations for future research.

Let's review your understanding of the discussion section by identifying what makes a strong discussion.

Planning for a discussion section

Planning for a discussion section starts with analysing your data. For some kinds of research, the analysis cannot be done until your data has been collected. For others, analysing data can happen early as the data already exists in literary texts, archival documents or similar.

Before starting to write the discussion section, it is important to:

analyse your data (usually reported in the Results or Findings section)

select the key issues that are the substance of your research

relate the findings to the literature and

plan for the process of going from your specific findings to the broader scientific field.

Your analysis of the results will inform the Findings or Results section of your thesis or publication. It is the stage where you organise and visualise your data, and identify trends, patterns and causal relationships in the themes.

As the section discusses the key findings without restating the results, it is important to identify the key issues. For example, you should focus on four or five issues that agree or do not agree with your hypothesis or with previously published work. It is also important to include and discuss any unexpected results.

You refer to previous research in your discussion section for explaining your results, confirming how your results support the theories and previous studies, comparing your results with similar studies, or showing how your results contradict similar studies.

Therefore, papers that you are likely to refer to in your discussion are those that led to:

your hypothesis

your experimental design

your results.

In writing the discussion section, you will start with your research and then broaden your focus to the field or scientific community. This means you will go from narrowest (your specific findings) to broadest (the wider scientific community). You do this by following the six moves:

As you can see, your discussion may follow six moves (stages) which broadens the scope of your discussion section. Watch this video to learn how to apply these moves.

Structuring your discussion

This section reviews how a discussion section can be organised.

A discussion section usually includes five parts or steps, which are illustrated in the image below.

In some disciplines, the researcher's argument determines the structure of the presentation and discussion of findings. In other disciplines, the structure follows established conventions. Therefore, it is important for you to investigate the conventions of your own discipline, by looking at theses in your discipline and articles published in your target journals. The discussion section may be:

in a combined section called Results and Discussion

in a combined section called Discussion and Conclusion

in a separate section.

Your discussion section may be an independent chapter or it might be combined with the Findings chapter. Common chapter headings include:

Discussion chapter

Findings and Discussion chapter

Discussion, Recommendations and Conclusion chapter

Discussion and Conclusion chapter

It is important to have a good understanding of the expected content of each chapter. Below is an example of a chapter in which discussion, recommendations and conclusion are combined.

Click on the hotspots to learn more.

This section focuses on useful language for writing your discussion.

Boosters and hedges should be used to demonstrate your confidence in your interpretation of the results. They help you to distinguish between clear and strong results and those that you feel less confident about or that may be open to different interpretations.

Read both sentences. Which one shows more confidence in the results?

The Dutch supervisors reported using different types of questions more frequently and deliberately than the Chinese supervisors. This difference may have its roots in the underlying educational philosophies. (Adapted from Hu, Rijst, Veen, & Verloop, 2016)

The findings clearly demonstrate that psychological capital had considerable influence on the 10 employability skills included in the study, and especially on those related to teamwork, self-knowledge and self-management (Adapted from Harper, Bregta & Rundle, 2021)

The writers of sentence two are more confident in the interpretation of their results.

Test your knowledge of hedges and boosters by doing the task below.

It is important to make it clear in your discussion:

which research has been done by you

which research has been done by other people

how they complement each other.

Image 2: Note that present perfect is also used to refer to other studies when you want to emphasise that an area of research is still current and ongoing. Take a look at the example below which uses present perfect to refer to other studies

Like other studies (e.g., Larcombe et al., 2021; Naylor, 2020) that have shown a strong connection between course experience and wellbeing, our study shows that a significant portion of international students believe that aspects of their immediate environment could be improved to better support their wellbeing.

More information on tenses in the Discussion section is presented in Language Tip 4 below.

Below are some useful discussion phrases that were adapted from Paltridge & Starfield (2020) and the APA Discussion phrases guide (7th edition).

You can download this APA discussion phrase guide here and visit the Academic Phrasebank for further phrases and examples.

Let's look at these extracts and identify the functions of the paragraphs.

Past, present and present perfect tenses are commonly used in the discussion section.

- Past tense is used to summarise the key findings and to refer to the work of previous researchers

- Present perfect is used to refer to the work of previous researchers (usually an area of research that is current and on-going rather than one single study)

- Present tense is used to interpret the results or describe the significance of the findings

- Future is used to make recommendations for further research or providing future direction

Below is an example of some paragraphs in a discussion section in which different tenses are used.

Test your knowledge of using the right tenses in the discussion section by doing the task below.

Use this template to plan your discussion.

The template is an example of a planning tool that will help you develop an overview of the key content that you are going to include in your section. You can download the draft and save it as a Word document once you have finished.

You may have more or less than 3 key findings that you would like to discuss in your section.

1 | Revisit the self-analysis quiz at the top of the page. How would you rate your skills now?

|

2 | Remember that writing is a process and mistakes aren't a bad thing. They are a normal part of learning and can help you to improve. |

If you would like more support, visit the Language and Learning Advisors page.

Butler, K. (2020, 7 April). Breakdown of an ideal discussion of scientific research paper. Scientific Communications . https://butlerscicomm.com/breakdown-of-ideal-discussion-section-research-paper

Calvo, J. C. A & García, G. M. (2021). The influence of psychological capital on graduates’ perception of employability: the mediating role of employability skills. Higher Education Research & Development , 40(2), 293-308, DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1738350

Cenamor, J. (2022) To teach or not to teach? Junior academics and the teaching-research relationship. Higher Education Research & Development , 41(5), 1417-1435. DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2021.1933395

Harper, R., Bretag, T & Rundle, K. (2021) Detecting contract cheating: examining the role of assessment type. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(2), 263-278, DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1724899

Hu, Y., Rijst, R. M., Veen, K & N Verloop, N. (2016) The purposes and processes of master's thesis supervision: a comparison of Chinese and Dutch supervisors. Higher Education Research & Development , 35(5), 910-924, DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2016.1139550

Humphrey, P. (2015). English language proficiency in higher education: student conceptualisations and outcomes . [Doctoral dissertation, Griffith University]

Marangell, S., & Baik, C. (2022). International students’ suggestions for what universities can do to better support their mental wellbeing. Journal of International Students, 12(4), 933-954.

Merga, M., & Mason, S. (2021) Early career researchers’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of sharing research with academic and non-academic end-users, Higher Education Research & Development , 40(7), 1482-1496, DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1815662

Paltridge, B., & Starfield, S. (2019). Thesis and Dissertation Writing in a Second Language: A Handbook for Students and their Supervisors (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Rendle-Short, J. (2009). The Address Term Mate in Australian English: Is it Still a Masculine Term?. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 29(2), 245-268, DOI: 10.1080/07268600902823110

Did you know CDU Language and Learning Advisors offer a range of study support options?

https://www.cdu.edu.au/library/language-and-learning-support

Cookie compliance notice

We use cookies to improve our service. By continuing you agree to our privacy statement . EU/EA members can update your cookie settings here .

Guide to Writing the Results and Discussion Sections of a Scientific Article

A quality research paper has both the qualities of in-depth research and good writing ( Bordage, 2001 ). In addition, a research paper must be clear, concise, and effective when presenting the information in an organized structure with a logical manner ( Sandercock, 2013 ).

In this article, we will take a closer look at the results and discussion section. Composing each of these carefully with sufficient data and well-constructed arguments can help improve your paper overall.

The results section of your research paper contains a description about the main findings of your research, whereas the discussion section interprets the results for readers and provides the significance of the findings. The discussion should not repeat the results.

Let’s dive in a little deeper about how to properly, and clearly organize each part.

How to Organize the Results Section

Since your results follow your methods, you’ll want to provide information about what you discovered from the methods you used, such as your research data. In other words, what were the outcomes of the methods you used?

You may also include information about the measurement of your data, variables, treatments, and statistical analyses.

To start, organize your research data based on how important those are in relation to your research questions. This section should focus on showing major results that support or reject your research hypothesis. Include your least important data as supplemental materials when submitting to the journal.

The next step is to prioritize your research data based on importance – focusing heavily on the information that directly relates to your research questions using the subheadings.

The organization of the subheadings for the results section usually mirrors the methods section. It should follow a logical and chronological order.

Subheading organization

Subheadings within your results section are primarily going to detail major findings within each important experiment. And the first paragraph of your results section should be dedicated to your main findings (findings that answer your overall research question and lead to your conclusion) (Hofmann, 2013).

In the book “Writing in the Biological Sciences,” author Angelika Hofmann recommends you structure your results subsection paragraphs as follows:

- Experimental purpose

- Interpretation

Each subheading may contain a combination of ( Bahadoran, 2019 ; Hofmann, 2013, pg. 62-63):

- Text: to explain about the research data

- Figures: to display the research data and to show trends or relationships, for examples using graphs or gel pictures.

- Tables: to represent a large data and exact value

Decide on the best way to present your data — in the form of text, figures or tables (Hofmann, 2013).

Data or Results?

Sometimes we get confused about how to differentiate between data and results . Data are information (facts or numbers) that you collected from your research ( Bahadoran, 2019 ).

Whereas, results are the texts presenting the meaning of your research data ( Bahadoran, 2019 ).

One mistake that some authors often make is to use text to direct the reader to find a specific table or figure without further explanation. This can confuse readers when they interpret data completely different from what the authors had in mind. So, you should briefly explain your data to make your information clear for the readers.

Common Elements in Figures and Tables

Figures and tables present information about your research data visually. The use of these visual elements is necessary so readers can summarize, compare, and interpret large data at a glance. You can use graphs or figures to compare groups or patterns. Whereas, tables are ideal to present large quantities of data and exact values.

Several components are needed to create your figures and tables. These elements are important to sort your data based on groups (or treatments). It will be easier for the readers to see the similarities and differences among the groups.

When presenting your research data in the form of figures and tables, organize your data based on the steps of the research leading you into a conclusion.

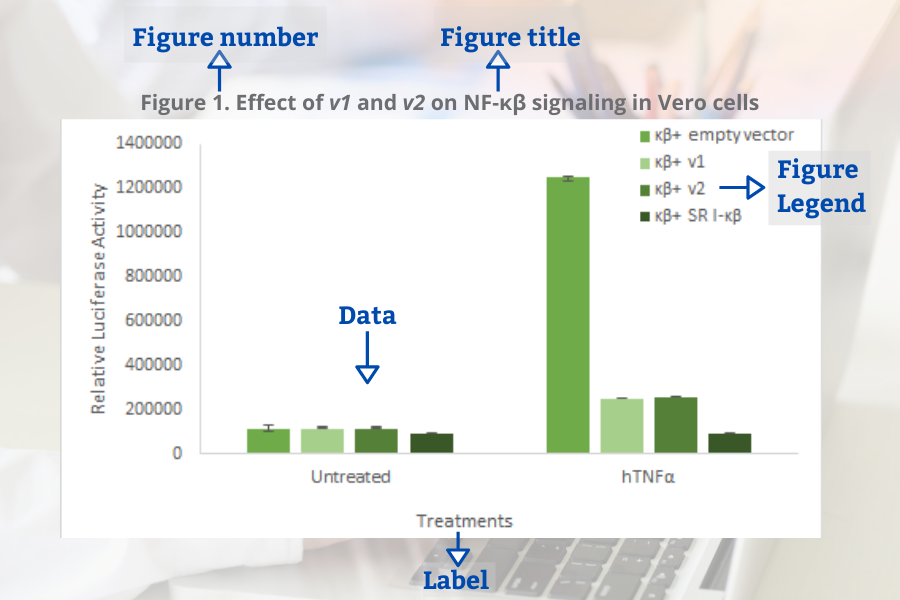

Common elements of the figures (Bahadoran, 2019):

- Figure number

- Figure title

- Figure legend (for example a brief title, experimental/statistical information, or definition of symbols).

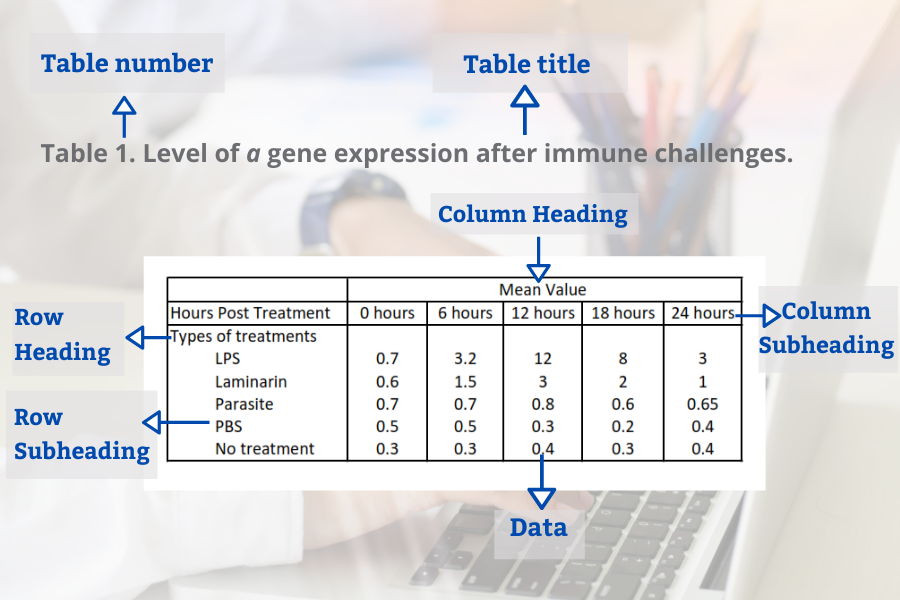

Tables in the result section may contain several elements (Bahadoran, 2019):

- Table number

- Table title

- Row headings (for example groups)

- Column headings

- Row subheadings (for example categories or groups)

- Column subheadings (for example categories or variables)

- Footnotes (for example statistical analyses)

Tips to Write the Results Section

- Direct the reader to the research data and explain the meaning of the data.

- Avoid using a repetitive sentence structure to explain a new set of data.

- Write and highlight important findings in your results.

- Use the same order as the subheadings of the methods section.

- Match the results with the research questions from the introduction. Your results should answer your research questions.

- Be sure to mention the figures and tables in the body of your text.

- Make sure there is no mismatch between the table number or the figure number in text and in figure/tables.

- Only present data that support the significance of your study. You can provide additional data in tables and figures as supplementary material.

How to Organize the Discussion Section

It’s not enough to use figures and tables in your results section to convince your readers about the importance of your findings. You need to support your results section by providing more explanation in the discussion section about what you found.

In the discussion section, based on your findings, you defend the answers to your research questions and create arguments to support your conclusions.

Below is a list of questions to guide you when organizing the structure of your discussion section ( Viera et al ., 2018 ):

- What experiments did you conduct and what were the results?

- What do the results mean?

- What were the important results from your study?

- How did the results answer your research questions?

- Did your results support your hypothesis or reject your hypothesis?

- What are the variables or factors that might affect your results?

- What were the strengths and limitations of your study?

- What other published works support your findings?

- What other published works contradict your findings?

- What possible factors might cause your findings different from other findings?

- What is the significance of your research?

- What are new research questions to explore based on your findings?

Organizing the Discussion Section

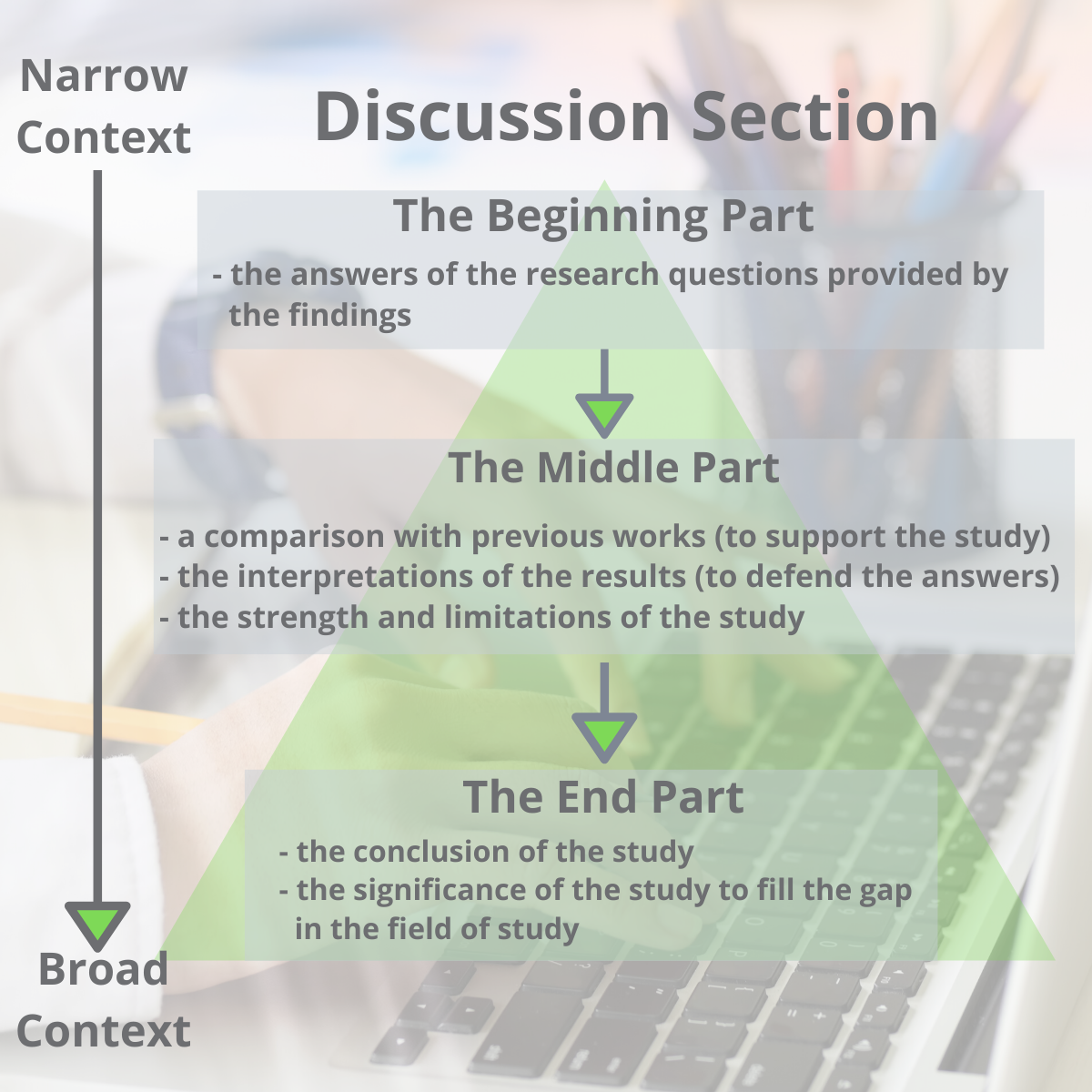

The structure of the discussion section may be different from one paper to another, but it commonly has a beginning, middle-, and end- to the section.

One way to organize the structure of the discussion section is by dividing it into three parts (Ghasemi, 2019):

- The beginning: The first sentence of the first paragraph should state the importance and the new findings of your research. The first paragraph may also include answers to your research questions mentioned in your introduction section.

- The middle: The middle should contain the interpretations of the results to defend your answers, the strength of the study, the limitations of the study, and an update literature review that validates your findings.

- The end: The end concludes the study and the significance of your research.

Another possible way to organize the discussion section was proposed by Michael Docherty in British Medical Journal: is by using this structure ( Docherty, 1999 ):

- Discussion of important findings

- Comparison of your results with other published works

- Include the strengths and limitations of the study

- Conclusion and possible implications of your study, including the significance of your study – address why and how is it meaningful

- Future research questions based on your findings

Finally, a last option is structuring your discussion this way (Hofmann, 2013, pg. 104):

- First Paragraph: Provide an interpretation based on your key findings. Then support your interpretation with evidence.

- Secondary results

- Limitations

- Unexpected findings

- Comparisons to previous publications

- Last Paragraph: The last paragraph should provide a summarization (conclusion) along with detailing the significance, implications and potential next steps.

Remember, at the heart of the discussion section is presenting an interpretation of your major findings.

Tips to Write the Discussion Section

- Highlight the significance of your findings

- Mention how the study will fill a gap in knowledge.

- Indicate the implication of your research.

- Avoid generalizing, misinterpreting your results, drawing a conclusion with no supportive findings from your results.

Aggarwal, R., & Sahni, P. (2018). The Results Section. In Reporting and Publishing Research in the Biomedical Sciences (pp. 21-38): Springer.

Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., Zadeh-Vakili, A., Hosseinpanah, F., & Ghasemi, A. (2019). The principles of biomedical scientific writing: Results. International journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 17(2).

Bordage, G. (2001). Reasons reviewers reject and accept manuscripts: the strengths and weaknesses in medical education reports. Academic medicine, 76(9), 889-896.

Cals, J. W., & Kotz, D. (2013). Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part VI: discussion. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 66(10), 1064.

Docherty, M., & Smith, R. (1999). The case for structuring the discussion of scientific papers: Much the same as that for structuring abstracts. In: British Medical Journal Publishing Group.

Faber, J. (2017). Writing scientific manuscripts: most common mistakes. Dental press journal of orthodontics, 22(5), 113-117.

Fletcher, R. H., & Fletcher, S. W. (2018). The discussion section. In Reporting and Publishing Research in the Biomedical Sciences (pp. 39-48): Springer.

Ghasemi, A., Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., Hosseinpanah, F., Shiva, N., & Zadeh-Vakili, A. (2019). The Principles of Biomedical Scientific Writing: Discussion. International journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 17(3).

Hofmann, A. H. (2013). Writing in the biological sciences: a comprehensive resource for scientific communication . New York: Oxford University Press.

Kotz, D., & Cals, J. W. (2013). Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part V: results. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 66(9), 945.

Mack, C. (2014). How to Write a Good Scientific Paper: Structure and Organization. Journal of Micro/ Nanolithography, MEMS, and MOEMS, 13. doi:10.1117/1.JMM.13.4.040101

Moore, A. (2016). What's in a Discussion section? Exploiting 2‐dimensionality in the online world…. Bioessays, 38(12), 1185-1185.

Peat, J., Elliott, E., Baur, L., & Keena, V. (2013). Scientific writing: easy when you know how: John Wiley & Sons.

Sandercock, P. M. L. (2012). How to write and publish a scientific article. Canadian Society of Forensic Science Journal, 45(1), 1-5.

Teo, E. K. (2016). Effective Medical Writing: The Write Way to Get Published. Singapore Medical Journal, 57(9), 523-523. doi:10.11622/smedj.2016156

Van Way III, C. W. (2007). Writing a scientific paper. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 22(6), 636-640.

Vieira, R. F., Lima, R. C. d., & Mizubuti, E. S. G. (2019). How to write the discussion section of a scientific article. Acta Scientiarum. Agronomy, 41.

Related Articles

A quality research paper has both the qualities of in-depth research and good writing (Bordage, 200...

How to Survive and Complete a Thesis or a Dissertation

Writing a thesis or a dissertation can be a challenging process for many graduate students. There ar...

12 Ways to Dramatically Improve your Research Manuscript Title and Abstract

The first thing a person doing literary research will see is a research publication title. After tha...

15 Laboratory Notebook Tips to Help with your Research Manuscript

Your lab notebook is a foundation to your research manuscript. It serves almost as a rudimentary dra...

Join our list to receive promos and articles.

- Competent Cells

- Lab Startup

- Z')" data-type="collection" title="Products A->Z" target="_self" href="/collection/products-a-to-z">Products A->Z

- GoldBio Resources

- GoldBio Sales Team

- GoldBio Distributors

- Duchefa Direct

- Sign up for Promos

- Terms & Conditions

- ISO Certification

- Agarose Resins

- Antibiotics & Selection

- Biochemical Reagents

- Bioluminescence

- Buffers & Reagents

- Cell Culture

- Cloning & Induction

- Competent Cells and Transformation

- Detergents & Membrane Agents

- DNA Amplification

- Enzymes, Inhibitors & Substrates

- Growth Factors and Cytokines

- Lab Tools & Accessories

- Plant Research and Reagents

- Protein Research & Analysis

- Protein Expression & Purification

- Reducing Agents

How to Start a Discussion Section in Research? [with Examples]

The examples below are from 72,017 full-text PubMed research papers that I analyzed in order to explore common ways to start writing the Discussion section.

Research papers included in this analysis were selected at random from those uploaded to PubMed Central between the years 2016 and 2021. Note that I used the BioC API to download the data (see the References section below).

Examples of how to start writing the Discussion section

In the Discussion section, you should explain the meaning of your results, their importance, and implications. [for more information, see: How to Write & Publish a Research Paper: Step-by-Step Guide ]

The Discussion section can:

1. Start by restating the study objective

“ The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between muscle synergies and motion primitives of the upper limb motions.” Taken from the Discussion section of this article on PubMed

“ The main objective of this study was to identify trajectories of autonomy.” Taken from the Discussion section of this article on PubMed

“ In the present study, we investigated the whole brain regional homogeneity in patients with melancholic MDD and non-melancholic MDD at rest . “ Taken from the Discussion section of this article on PubMed

2. Start by mentioning the main finding

“ We found that autocracy and democracy have acted as peaks in an evolutionary landscape of possible modes of institutional arrangements.” Taken from the Discussion section of this article on PubMed

“ In this study, we demonstrated that the neural mechanisms of rhythmic movements and skilled movements are similar.” Taken from the Discussion section of this article on PubMed

“ The results of this study show that older adults are a diverse group concerning their activities on the Internet.” Taken from the Discussion section of this article on PubMed

3. Start by pointing out the strength of the study

“ To our knowledge, this investigation is by far the largest epidemiological study employing real-time PCR to study periodontal pathogens in subgingival plaque.” Taken from the Discussion section of this article on PubMed

“ This is the first human subject research using the endoscopic hemoglobin oxygen saturation imaging technology for patients with aero-digestive tract cancers or adenomas.” Taken from the Discussion section of this article on PubMed

“ In this work, we introduced a new real-time flow imaging method and systematically demonstrated its effectiveness with both flow phantom experiments and in vivo experiments.” Taken from the Discussion section of this article on PubMed

Most used words at the start of the Discussion

Here are the top 10 phrases used to start a discussion section in our dataset:

| Rank | Phrase | Percent of occurrences |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “In this study,…” | 4.48% |

| 2 | “In the present study,…” | 1.66% |

| 3 | “To our knowledge,…” | 0.73% |

| 4 | “To the best of our knowledge,…” | 0.51% |

| 5 | “In the current study,…” | 0.38% |

| 6 | “The aim of this study was…” | 0.38% |

| 7 | “This is the first study to…” | 0.28% |

| 8 | “The purpose of this study was to…” | 0.22% |

| 9 | “The results of the present study…” | 0.14% |

| 10 | “The aim of the present study was…” | 0.11% |

- Comeau DC, Wei CH, Islamaj Doğan R, and Lu Z. PMC text mining subset in BioC: about 3 million full text articles and growing, Bioinformatics , btz070, 2019.

Further reading

- How Long Should the Discussion Section Be? Data from 61,517 Examples

- How to Write & Publish a Research Paper: Step-by-Step Guide

- “I” & “We” in Academic Writing: Examples from 9,830 Studies

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Discussion Section for a Research Paper

We’ve talked about several useful writing tips that authors should consider while drafting or editing their research papers. In particular, we’ve focused on figures and legends , as well as the Introduction , Methods , and Results . Now that we’ve addressed the more technical portions of your journal manuscript, let’s turn to the analytical segments of your research article. In this article, we’ll provide tips on how to write a strong Discussion section that best portrays the significance of your research contributions.

What is the Discussion section of a research paper?

In a nutshell, your Discussion fulfills the promise you made to readers in your Introduction . At the beginning of your paper, you tell us why we should care about your research. You then guide us through a series of intricate images and graphs that capture all the relevant data you collected during your research. We may be dazzled and impressed at first, but none of that matters if you deliver an anti-climactic conclusion in the Discussion section!

Are you feeling pressured? Don’t worry. To be honest, you will edit the Discussion section of your manuscript numerous times. After all, in as little as one to two paragraphs ( Nature ‘s suggestion based on their 3,000-word main body text limit), you have to explain how your research moves us from point A (issues you raise in the Introduction) to point B (our new understanding of these matters). You must also recommend how we might get to point C (i.e., identify what you think is the next direction for research in this field). That’s a lot to say in two paragraphs!

So, how do you do that? Let’s take a closer look.

What should I include in the Discussion section?

As we stated above, the goal of your Discussion section is to answer the questions you raise in your Introduction by using the results you collected during your research . The content you include in the Discussions segment should include the following information:

- Remind us why we should be interested in this research project.

- Describe the nature of the knowledge gap you were trying to fill using the results of your study.

- Don’t repeat your Introduction. Instead, focus on why this particular study was needed to fill the gap you noticed and why that gap needed filling in the first place.

- Mainly, you want to remind us of how your research will increase our knowledge base and inspire others to conduct further research.

- Clearly tell us what that piece of missing knowledge was.

- Answer each of the questions you asked in your Introduction and explain how your results support those conclusions.

- Make sure to factor in all results relevant to the questions (even if those results were not statistically significant).

- Focus on the significance of the most noteworthy results.

- If conflicting inferences can be drawn from your results, evaluate the merits of all of them.

- Don’t rehash what you said earlier in the Results section. Rather, discuss your findings in the context of answering your hypothesis. Instead of making statements like “[The first result] was this…,” say, “[The first result] suggests [conclusion].”

- Do your conclusions line up with existing literature?

- Discuss whether your findings agree with current knowledge and expectations.

- Keep in mind good persuasive argument skills, such as explaining the strengths of your arguments and highlighting the weaknesses of contrary opinions.

- If you discovered something unexpected, offer reasons. If your conclusions aren’t aligned with current literature, explain.

- Address any limitations of your study and how relevant they are to interpreting your results and validating your findings.

- Make sure to acknowledge any weaknesses in your conclusions and suggest room for further research concerning that aspect of your analysis.

- Make sure your suggestions aren’t ones that should have been conducted during your research! Doing so might raise questions about your initial research design and protocols.

- Similarly, maintain a critical but unapologetic tone. You want to instill confidence in your readers that you have thoroughly examined your results and have objectively assessed them in a way that would benefit the scientific community’s desire to expand our knowledge base.

- Recommend next steps.

- Your suggestions should inspire other researchers to conduct follow-up studies to build upon the knowledge you have shared with them.

- Keep the list short (no more than two).

How to Write the Discussion Section

The above list of what to include in the Discussion section gives an overall idea of what you need to focus on throughout the section. Below are some tips and general suggestions about the technical aspects of writing and organization that you might find useful as you draft or revise the contents we’ve outlined above.

Technical writing elements

- Embrace active voice because it eliminates the awkward phrasing and wordiness that accompanies passive voice.

- Use the present tense, which should also be employed in the Introduction.

- Sprinkle with first person pronouns if needed, but generally, avoid it. We want to focus on your findings.

- Maintain an objective and analytical tone.

Discussion section organization

- Keep the same flow across the Results, Methods, and Discussion sections.

- We develop a rhythm as we read and parallel structures facilitate our comprehension. When you organize information the same way in each of these related parts of your journal manuscript, we can quickly see how a certain result was interpreted and quickly verify the particular methods used to produce that result.

- Notice how using parallel structure will eliminate extra narration in the Discussion part since we can anticipate the flow of your ideas based on what we read in the Results segment. Reducing wordiness is important when you only have a few paragraphs to devote to the Discussion section!

- Within each subpart of a Discussion, the information should flow as follows: (A) conclusion first, (B) relevant results and how they relate to that conclusion and (C) relevant literature.

- End with a concise summary explaining the big-picture impact of your study on our understanding of the subject matter. At the beginning of your Discussion section, you stated why this particular study was needed to fill the gap you noticed and why that gap needed filling in the first place. Now, it is time to end with “how your research filled that gap.”

Discussion Part 1: Summarizing Key Findings

Begin the Discussion section by restating your statement of the problem and briefly summarizing the major results. Do not simply repeat your findings. Rather, try to create a concise statement of the main results that directly answer the central research question that you stated in the Introduction section . This content should not be longer than one paragraph in length.

Many researchers struggle with understanding the precise differences between a Discussion section and a Results section . The most important thing to remember here is that your Discussion section should subjectively evaluate the findings presented in the Results section, and in relatively the same order. Keep these sections distinct by making sure that you do not repeat the findings without providing an interpretation.

Phrase examples: Summarizing the results

- The findings indicate that …

- These results suggest a correlation between A and B …

- The data present here suggest that …

- An interpretation of the findings reveals a connection between…

Discussion Part 2: Interpreting the Findings

What do the results mean? It may seem obvious to you, but simply looking at the figures in the Results section will not necessarily convey to readers the importance of the findings in answering your research questions.

The exact structure of interpretations depends on the type of research being conducted. Here are some common approaches to interpreting data:

- Identifying correlations and relationships in the findings

- Explaining whether the results confirm or undermine your research hypothesis

- Giving the findings context within the history of similar research studies

- Discussing unexpected results and analyzing their significance to your study or general research

- Offering alternative explanations and arguing for your position

Organize the Discussion section around key arguments, themes, hypotheses, or research questions or problems. Again, make sure to follow the same order as you did in the Results section.

Discussion Part 3: Discussing the Implications

In addition to providing your own interpretations, show how your results fit into the wider scholarly literature you surveyed in the literature review section. This section is called the implications of the study . Show where and how these results fit into existing knowledge, what additional insights they contribute, and any possible consequences that might arise from this knowledge, both in the specific research topic and in the wider scientific domain.

Questions to ask yourself when dealing with potential implications:

- Do your findings fall in line with existing theories, or do they challenge these theories or findings? What new information do they contribute to the literature, if any? How exactly do these findings impact or conflict with existing theories or models?

- What are the practical implications on actual subjects or demographics?

- What are the methodological implications for similar studies conducted either in the past or future?

Your purpose in giving the implications is to spell out exactly what your study has contributed and why researchers and other readers should be interested.

Phrase examples: Discussing the implications of the research

- These results confirm the existing evidence in X studies…

- The results are not in line with the foregoing theory that…

- This experiment provides new insights into the connection between…

- These findings present a more nuanced understanding of…

- While previous studies have focused on X, these results demonstrate that Y.

Step 4: Acknowledging the limitations

All research has study limitations of one sort or another. Acknowledging limitations in methodology or approach helps strengthen your credibility as a researcher. Study limitations are not simply a list of mistakes made in the study. Rather, limitations help provide a more detailed picture of what can or cannot be concluded from your findings. In essence, they help temper and qualify the study implications you listed previously.

Study limitations can relate to research design, specific methodological or material choices, or unexpected issues that emerged while you conducted the research. Mention only those limitations directly relate to your research questions, and explain what impact these limitations had on how your study was conducted and the validity of any interpretations.

Possible types of study limitations:

- Insufficient sample size for statistical measurements

- Lack of previous research studies on the topic

- Methods/instruments/techniques used to collect the data

- Limited access to data

- Time constraints in properly preparing and executing the study

After discussing the study limitations, you can also stress that your results are still valid. Give some specific reasons why the limitations do not necessarily handicap your study or narrow its scope.

Phrase examples: Limitations sentence beginners

- “There may be some possible limitations in this study.”

- “The findings of this study have to be seen in light of some limitations.”

- “The first limitation is the…The second limitation concerns the…”

- “The empirical results reported herein should be considered in the light of some limitations.”

- “This research, however, is subject to several limitations.”

- “The primary limitation to the generalization of these results is…”

- “Nonetheless, these results must be interpreted with caution and a number of limitations should be borne in mind.”

Discussion Part 5: Giving Recommendations for Further Research

Based on your interpretation and discussion of the findings, your recommendations can include practical changes to the study or specific further research to be conducted to clarify the research questions. Recommendations are often listed in a separate Conclusion section , but often this is just the final paragraph of the Discussion section.

Suggestions for further research often stem directly from the limitations outlined. Rather than simply stating that “further research should be conducted,” provide concrete specifics for how future can help answer questions that your research could not.

Phrase examples: Recommendation sentence beginners

- Further research is needed to establish …

- There is abundant space for further progress in analyzing…

- A further study with more focus on X should be done to investigate…

- Further studies of X that account for these variables must be undertaken.

Consider Receiving Professional Language Editing

As you edit or draft your research manuscript, we hope that you implement these guidelines to produce a more effective Discussion section. And after completing your draft, don’t forget to submit your work to a professional proofreading and English editing service like Wordvice, including our manuscript editing service for paper editing , cover letter editing , SOP editing , and personal statement proofreading services. Language editors not only proofread and correct errors in grammar, punctuation, mechanics, and formatting but also improve terms and revise phrases so they read more naturally. Wordvice is an industry leader in providing high-quality revision for all types of academic documents.

For additional information about how to write a strong research paper, make sure to check out our full research writing series !

Wordvice Writing Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

Additional Academic Resources

- Guide for Authors. (Elsevier)

- How to Write the Results Section of a Research Paper. (Bates College)

- Structure of a Research Paper. (University of Minnesota Biomedical Library)

- How to Choose a Target Journal (Springer)

- How to Write Figures and Tables (UNC Writing Center)

- Langson Library

- Science Library

- Grunigen Medical Library

- Law Library

- Connect From Off-Campus

- Accessibility

- Gateway Study Center

Email this link

Writing a scientific paper.

- Writing a lab report

- INTRODUCTION

Writing a "good" discussion section

"discussion and conclusions checklist" from: how to write a good scientific paper. chris a. mack. spie. 2018., peer review.

- LITERATURE CITED

- Bibliography of guides to scientific writing and presenting

- Presentations

- Lab Report Writing Guides on the Web

This is is usually the hardest section to write. You are trying to bring out the true meaning of your data without being too long. Do not use words to conceal your facts or reasoning. Also do not repeat your results, this is a discussion.

- Present principles, relationships and generalizations shown by the results

- Point out exceptions or lack of correlations. Define why you think this is so.

- Show how your results agree or disagree with previously published works

- Discuss the theoretical implications of your work as well as practical applications

- State your conclusions clearly. Summarize your evidence for each conclusion.

- Discuss the significance of the results

- Evidence does not explain itself; the results must be presented and then explained.

- Typical stages in the discussion: summarizing the results, discussing whether results are expected or unexpected, comparing these results to previous work, interpreting and explaining the results (often by comparison to a theory or model), and hypothesizing about their generality.

- Discuss any problems or shortcomings encountered during the course of the work.

- Discuss possible alternate explanations for the results.

- Avoid: presenting results that are never discussed; presenting discussion that does not relate to any of the results; presenting results and discussion in chronological order rather than logical order; ignoring results that do not support the conclusions; drawing conclusions from results without logical arguments to back them up.

CONCLUSIONS

- Provide a very brief summary of the Results and Discussion.

- Emphasize the implications of the findings, explaining how the work is significant and providing the key message(s) the author wishes to convey.

- Provide the most general claims that can be supported by the evidence.

- Provide a future perspective on the work.

- Avoid: repeating the abstract; repeating background information from the Introduction; introducing new evidence or new arguments not found in the Results and Discussion; repeating the arguments made in the Results and Discussion; failing to address all of the research questions set out in the Introduction.

WHAT HAPPENS AFTER I COMPLETE MY PAPER?

The peer review process is the quality control step in the publication of ideas. Papers that are submitted to a journal for publication are sent out to several scientists (peers) who look carefully at the paper to see if it is "good science". These reviewers then recommend to the editor of a journal whether or not a paper should be published. Most journals have publication guidelines. Ask for them and follow them exactly. Peer reviewers examine the soundness of the materials and methods section. Are the materials and methods used written clearly enough for another scientist to reproduce the experiment? Other areas they look at are: originality of research, significance of research question studied, soundness of the discussion and interpretation, correct spelling and use of technical terms, and length of the article.

- << Previous: RESULTS

- Next: LITERATURE CITED >>

- Last Updated: Aug 4, 2023 9:33 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uci.edu/scientificwriting

Off-campus? Please use the Software VPN and choose the group UCIFull to access licensed content. For more information, please Click here

Software VPN is not available for guests, so they may not have access to some content when connecting from off-campus.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

General Research Paper Guidelines: Discussion

Discussion section.