Background of Financial Instruments

- First Online: 01 January 2012

Cite this chapter

- Sven-Eric Bärsch 2

1232 Accesses

Since the current financial and economic environment presents many challenges for most economic agents, financial transactions and their instruments are likely be one of those challenges. Hereby, this thesis deals with the treatment of hybrid financial instruments for corporate income tax purposes in an international and cross-border context. But, before focusing on the relevant tax aspects on this matter, it is essential to depict a more detailed overview of what hybrid financial instruments are, the extent to which they influence or are influenced by the environment from an economic and legal perspective, and the general tax consequences of financial instruments in a cross-border context. This outline is necessary to assess how hybrid financial instruments affect the design of tax rules as well as how the given fundamental corporate income tax treatment limits this design.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Cf. MacNeil 2005 : 208; Brealey et al. 2008 : 386 et seq.; Hillier et al. 2008 : 3 et seq.

Based on the following distinction both instruments can be labeled as non-mezzanine and non-structured financial instruments.

Cf. Sect. 3.2.1; Hillier et al. 2008 : 5, 32; Helminen 2010 : 166.

Cf. Schneider 1992 : 21; Drukarczyk 1993 : 35; Pratt 2000 : 1056 et seq.

Representative for many other cf. Eber-Huber 1996 : 8; Jänisch et al. 2002 : 2451; Schrell and Kirchner 2003 : 13; Bogenschütz 2008a : 533; Bogenschütz 2008b : 50; Küting et al. 2008 : 941; Bock 2010 : 66.

Cf. OECD 1994 : 7 et seq.; Funk 1998 : 138; Duncan 2000 : 22 et seq.; Pistone and Romano 2001 : 35; Krause 2006 : 58 et seq.; Briesemeister 2006 : 12 et seq., with further references; Helminen 2010 : 164, with further references.

Cf. Sect. 3.2.1.

Figure 2.1 presents a classification of financial instruments with a focus on hybrid financial instruments. However, since each kind of classification is purpose-driven, there is no universally correct classification. With regard to the scope of this thesis the emphasis is on the demarcation of such hybrid financial instruments which are affected by the debt/equity distinction. In simple terms see also Krause 2006 : 79 et seq. Regarding an exchange market segment-based classification see also Krause 2006 : 79 et seq.; Bogenschütz 2008b : 51 et seq. For another classification with a focus on derivative components see e.g. Laukkanen 2007 : 18 et seq.

Cf. Brealey et al. 2008 ; Hillier et al. 2008 ; Ross et al. 2008 . See also IAS 32 Para. AG15.

Cf. inter alia MacNeil 2005 : 108 et seq. See also IAS 32 Para. AG15 and IAS 39 Para. 9; Herzig 2000: 482.

Yet, their terms are not used consistently in practice and theory. Cf. inter alia Briesemeister 2006 : 14 et seq., with further references.

Cf. Briesemeister 2006 : 14 et seq., with further references; Schulz 2006 : 9; Natusch 2007 : 22 et seq.; Bogenschütz 2008b : 51 et seq.; Mäntysaari 2010 : 283. See further Lang 1991 : 14; Drukarczyk 1993 : 581; Eber-Huber 1996 : 8; Haun 1996 : 7 et seq., with further references; Herzig 2000: 482; MacNeil 2005 : 209; Eilers and Rödding 2007 : 84 et seq.; Helminen 2010 : 164 et seq.; Lampreave 2011 : Footnote 67. However, the term ‘hybrid financial instrument’ will be used oftentimes synonymously for mezzanine financial instruments in practice and theory. See e.g. Eber-Huber 1996 : 8; Haun 1996 : 10; Wagner 2005c : 499; Laukkanen 2007 : 37; Bogenschütz 2008a : 533; Bogenschütz 2008b : 50; Bock 2010 : 65 et seq.; Helminen 2010 : 164.

Cf. Dombek 2002 : 1065 et seq.; Briesemeister 2006 : 17 et seq., with further references; German Institute of Public Auditors 2008 : 455; Schaber et al. 2008 : 1; Reiner and Schacht 2010 : 387; Murre 2012 : 25 et seq. See further also Luttermann 2001 : 1901. These financial instruments fulfill the definition of financial instruments in accordance to IAS 39 Para. 8 and IAS 39 Para. 11.

Cf. Chaps. 4 and 5 .

Cf. e.g. Storck 2011 : 29 et seq. Although the focus is on the capital market as a part of the financial markets, both are used synonymously here.

Cf. Allen and Santomero 1998 : 1464; Alworth 1998 : 509; Hillier et al. 2008 : 25; Ledure et al. 2010 : 352.

Other developments, which are not within the scope of the further analysis, are in particular the proliferation of derivative instruments (representative for many see Warren 1993 : 460 et seq.; Hull 2009 : 1 et seq.; Hartmann-Wendels et al. 2010 : 271 et seq.; Valdez and Molyneux 2010 : 381 et seq.) and securization transactions (see e.g. Allen and Santomero 1998 : 1474; Hartmann-Wendels et al. 2010 : 207 et seq.; Valdez and Molyneux 2010 : 273 et seq.).

For a distinction between direct and portfolio investments cf. Herman 2002 : 71 et seq.; Graetz and Grinberg 2003 : 547 et seq.

Cf. Bulow et al. 1990 : 135, 139; Polito 1998 : 778; Benshalom 2010 : 1238, 1246. See further also Avi-Yonah 2004 : 1232.

Cf. Pratt 2000 : 1072 et seq.; Teichmann 2001 : 651 et seq.; Graetz and Grinberg 2003 : 542 et seq.;European Commission 2004b : 9. See further also Allen and Santomero 1998 : 1464; Avi-Yonah 2004 : 1232. In practice, see also e.g. Storck and Spori 2008 : 250 et seq.; Siemens 2010a : 59.

Cf. Kopcke and Rosengren 1989 : 4; Herman 2002 : 9 et seq.; Benshalom 2010 : 1239. See further also Allen 1989 : 16 et seq.; Allen and Santomero 1998 : 1464 et seq.

Cf. Hariton 1988 : 770; Franke and Hax 2009 : 56; Semer 2010 : 1478.

Cf. Allen 1989 : 17; Teichmann 2001 : 651 et seq.

Cf. IFRS Framework Para. 12. See also Brinkmann 2007 : 229 et seq.; Cuzmann et al. 2010 : 284 et seq.

Cf. Brealey et al. 2008 : 944 et seq.; Hillier et al. 2008 : 19, 21. See further also Rudolph 2006 : 400 et seq.; Bundgaard 2010a : 442.

Cf. inter alia Rudolf 2005 : 2. See also Grinblatt and Titman 2002 : 19; Friderichs and Körting 2011 : 31 et seq., both for Germany. See further also Hillier et al. 2008 : 20.

Cf. Ledure et al. 2010 : 352, 354; Valdez and Molyneux 2010 : 299. In practice, see e.g. Siemens 2010b : 103. However, a remarkable stability in bank financing could be observed in particular for Germany. Cf. Friderichs and Körting 2011 : 36 et seq.

Cf. Sect. 2.2.2 ; Waschbusch et al. 2009 : 353.

Cf. Ledure et al. 2010 : 354; Bourtourault and Bénard 2011 : 187; Storck 2011 : 29. See further also Friderichs and Körting 2011 : 35.

Cf. Herman 2002 : 9 et seq.; Allen and Santomero 1998 : 1464 et seq.; Teichmann 2001 : 652; Brealey et al. 2008 : 390 et seq., 396 et seq., 400 et seq., 946; Hartmann-Wendels et al. 2010 : 18. When markets were complete and perfect, the allocation of resources is efficient, so that there is no need for intermediaries to improve welfare. Cf. Fama 1980 : 39 et seq.; Franke and Hax 2009 : 501; Hartmann-Wendels et al. 2010 : 123. However, markets are characterized by asymmetric information and transaction costs. Cf. Allen and Santomero 1998 : 1464 et seq.; Hartmann-Wendels et al. 2010 : 123 et seq., both with further references.

Cf. Bodie 1989 : 107; Gebhardt et al. 1993 : 10 et seq.; Allen and Santomero 1998 : 1482; MacNeil 2005 : 7; Hartmann-Wendels et al. 2010 : 18. Nevertheless, there is also a trend towards the market (instead of the intermediaries) allowing borrowers to occupy the financial markets directly for fund raising, inter alia due to recent technological developments as well as financial innovation (disintermediation). Cf. Horne 1985 : 621; Gebhardt et al. 1993 : 14; Herman 2002 : 17 et seq.; Hartmann-Wendels et al. 2010 : 18; Valdez and Molyneux 2010 : 170. However, financial intermediaries have not become obsolete (in fact, quite the reverse has happened), but rather their role has moved from between lender and borrower to between lender and market since financial instruments and markets have become more complex and riskier. Cf. Allen and Santomero 1998 : 1483.

Cf. Allen and Santomero 1998 : 1464; Alworth 1998 : 509; Brealey et al. 2008 : 390 et seq., 396 et seq.; Valdez and Molyneux 2010 : 235 et seq. See further also Bulow et al. 1990 : 139; Eilers and Rödding 2007 : 83; Kalss 2007 : 523. See also Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2010 : 10, for the United States; OECD 2009 : 72, for OECD Member States. For a distinction between bank and non-bank financial intermediaries see in more detail e.g. Valdez and Molyneux 2010 : 73 et seq., 235 et seq.

Cf. e.g. Allen and Santomero 1998 : 1464, 1474.

Cf. further Valdez and Molyneux 2010 : 469.

Cf. Horne 1985 : 630; Bodie 1989 : 116 et seq.; Herman 2002 : 15. See further also Kalss 2007 : 523.

Cf. Kopcke and Rosengren 1989 : 1; Herman 2002 : 15. In practice, see also Siemens 2010b : 58. For the factors as causes of financial innovation in more detail see Finnerty 1988 : 16 et seq.

Cf. Pratt 2000 : 1075 et seq.; Hillier et al. 2008 : 53 et seq. See further also Jacobs and Haun 1995 : 405; Bundgaard 2010a : 442. Besides the introduction of new financial products, this includes also pure derivative instruments which are, however, not within the scope of this thesis. Cf. Allen and Santomero 1998 : 1464. With regard thereto see fundamentally Hull 2009 : 1 et seq.; Hartmann-Wendels et al. 2010 : 271 et seq. The dynamic development is attributed in particular to both the increase in economic uncertainty and rapid technological developments. Cf. Ramsler 1993 : 434 et seq.; Herman 2002 : 19 et seq. See further also Horne 1985 : 630; Bodie 1989 : 116.

Cf. Allen 1989 : 12; Bulow et al. 1990 : 135; Cerny 1994 : 333; Polito 1998 : 778. However, this dichotomy constitutes merely a simplification, since already in history an array of financial instruments has been issued albeit at a slower pace. Cf. Allen 1989 : 14 et seq.; Allen and Gale 1994 : 11 et seq. Against it, recent past’s as well as today’s pace and volume of financial innovation has no equal in history. Cf. Miller 1986 : 459 et seq.; Allen and Santomero 1998 : 1464; Alworth 1998 : 509; Edgar 2000 : 25; Hillier et al. 2008 : 53 et seq.

Cf. Schneider 1992 : 21; Drukarczyk 1993 : 35; Pratt 2000 : 1056 et seq. With regard to bonds see e.g. Hillier et al. 2008 : 44.

Cf. Hariton 1994 : 501 et seq.; Santangelo 1997 : 332; Edgar 2000 : 92 et seq. For a classification of the precise risks associated with financial investments see MacNeil 2005 : 5 et seq.

Cf. Kopcke and Rosengren 1989 : 3; Normandin 1989 : 65; Bulow et al. 1990 : 135 et seq.

Cf. e.g. Allen 1989 : 16 et seq.

Cf. also Hariton 1988 : 775; Kopcke and Rosengren 1989 : 1 et seq., 11; Hariton 1994 : 501 et seq.; Santangelo 1997 : 332. See further also Elschen 1993 : 586; Ramsler 1993 : 439; Edgar 2000 : 25, 93 et seq.; Hillier et al. 2008 : 25, 52 et seq. From the market perspective, financial innovations may make financial markets more efficient and complete in terms of enhanced prospects for risk sharing between investors. Cf. e.g. Horne 1985 : 621 et seq. For the development of equivalent cash flows under the use of the put-call parity theorem see Warren 1993 : 465 et seq.; Shaviro 1995 : 652 et seq.; Edgar 2000 : 21 et seq., 94 et seq.

Cf. Arouri et al. 2010 : 145, 148; Eiteman et al. 2010 : 377 et seq.; Zodrow 2010 : 866; Martínez Bárbara 2011 : 270. See further also Alworth 1998 : 509; Herman 2002 : 48 et seq.; Hillier et al. 2008 : 20 et seq., 25.

Cf. Herman 2002 : 63; Arouri et al. 2010 : 152 et seq.; Eiteman et al. 2010 : 432 et seq.

Cf. Cerny 1994 : 330 et seq.; Lothian 2002 : 723; Hillier et al. 2008 : 26; Arouri et al. 2010 : 148, 151; Zodrow 2010 : 866; Martínez Bárbara 2011 : 270. See further also Alworth 1998 : 509; Herman 2002 : 56; Eidenmüller 2007 : 487; Kalss 2007 : 523. For the main advantages and disadvantages of an enhanced international financial integration see e.g. Arouri et al. 2010 : 152 et seq.

Cf. Fukao and Hanazaki 1986 : 6, 13; European Commission 2004b : 9; Heathcotea and Perri 2004 : 207 et seq.; Hillier et al. 2008 : 74 et seq.; Arouri et al. 2010 : 145; Zodrow 2010 : 866. See also Jacobs and Haun 1995 : 405. In practice, see e.g. Siemens 2010b: 104. This development is by no means a new phenomenon, but reaches back much further in history. Cf. Herman 2002 : 30; Lothian 2002 : 700 et seq. However, the financial integration today is more complete and more geographically ubiquitous and the number of financial markets has grown enormously. Cf. Lothian 2002 : 700, 723. For instance, today’s emerging countries have started to participate effectively in international integration of financial markets since only the 1990s. Cf. Haggard and Maxfield 1996 : 35 et seq.; Arouri et al. 2010 : 147.

Cf. Kose et al. 2006 : 23 et seq.; Hines 2007 : 268 et seq.; Griffith et al. 2010 917; Zodrow 2010 : 866. See Graetz and Grinberg 2003 : 542 et seq., for the United States. For a distinction between direct and portfolio investments see Herman 2002 : 71 et seq.; Graetz and Grinberg 2003 : 547 et seq.

Cf. Fukao and Hanazaki 1986 : 13; Hines 2007 : 268 et seq.; Arouri et al. 2010 : 147; Zodrow 2010 : 866.

Cf. Emmerich 1985 : 134; Eiteman et al. 2010 : 24 et seq.; 410 et seq. See further also Perridon et al. 2009 : 10 et seq.

Cf. Modigliani and Miller 1958 : 261 et seq. See also Myers 2001 : 84 et seq.; Brealey et al. 2008 : 472 et seq.; Hillier et al. 2008 : 508 et seq.; Ross et al. 2008 : 428 et seq.; Wüstemann and Bischof 2011 : 214 et seq.

Cf. Brealey et al. 2008 : 487.

Cf. Modigliani and Miller 1963 : 433 et seq.; Myers 2001 : 86 et seq.; Brealey et al. 2008 : 497 et seq.; Hillier et al. 2008 : 516 et seq.; Ross et al. 2008 : 441 et seq., 465. More controversially see Miller 1977 : 268 et seq. Regarding the prevailing concept of the tax deductibility of debt financing costs see in more detail Sect. 2.3 .

Cf. Graham 2000 : 1901 et seq.; Myers 2001 : 82 et seq.; Ross et al. 2008 : 479 et seq.

Cf. Baxter 1967 : 396 et seq. Such costs include, for instance, legal and administrative costs as well as the interrupted ability to conduct business and to make appropriate investments. Cf. Brealey et al. 2008 : 487, 503 et seq.; Ross et al. 2008 : 455 et seq. See further Miller 1977 : 262 et seq.; Edgar 2000 : 99 et seq., with further references; Hillier et al. 2008 : 569 et seq.

Considering company law, obligations derived from financial instruments classified as debt differ from those derived from financial instruments classified as equity as, for instance, the latter do not legally entitle a company to remuneration payments in the way the former provides legal entitlement. Cf. Sect. 3.2.1.

Cf. Scott 1976 : 33 et seq.; DeAngelo and Masulis 1980 : 3 et seq.; Graham and Harvey 2001 : 210; Myers 2001 : 88 et seq.; Brealey et al. 2008 : 503 et seq., 515 et seq.; Ross et al. 2008 : 465 et seq.; Cotei and Farhat 2009 : 4.

Cf. Bradley et al. 1984 : 869 et seq.; Rajan and Zingales 1991 : 1421 et seq.; Graham and Harvey 2001 : 209 et seq.; Myers 2001 : 82 et seq.; Hillier et al. 2008 : 625 et seq.; Ross et al. 2008 : 481. In practice, see also Siemens 2010b : 58 et seq., 100.

Cf. Ackermann and Jäckle 2006 : 879; Rudolph 2006 : 404; Blaurock 2007 : 609 et seq.; Wiehe et al. 2007 : 222 et seq.; Kessler et al. 2008 : 903; Horst 2011 : 590; Sheppard 2011 : 1107; Storck 2011 : 30.

Cf. Graham and Harvey 2001 : 211; Storck 2011 : 30. In practice, see also Siemens 2010a : 59;Siemens 2010b : 99. For the rating methodologies of Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s see e.g. Rüßmann and Vögtle 2010: 209 et seq.

Cf. Wald 1999 : 161 et seq.; Brealey et al. 2008 : 516 et seq. See also Noulas and Genimakis 2011 : 384 et seq. Moreover, there are critics pointing out that costs of financial distress seem to be much smaller than the tax benefits. Cf. e.g. Miller 1977 : 262 et seq. However, the pure threat of bankruptcy can be also cost-increasing with regard to stakeholders, who do not have capital stakes in the corporations such as e.g. customers and suppliers, since such stakeholders are increasingly reluctant to do business with financially distressed corporations. Cf. in more detail Hillier et al. 2008 : 607 et seq.

Cf. Myers and Majluf 1984 : 203 et seq.; Graham and Harvey 2001 : 219; Myers 2001 : 91 et seq.; Frank and Goyal 2003 : 220; Brealey et al. 2008 : 517 et seq.; Ross et al. 2008 : 472 et seq.; Cotei and Farhat 2009 : 3.

Cf. Myers 1984 : 581 et seq.; Graham and Harvey 2001 : 215; Myers 2001 : 91 et seq.; Brealey et al. 2008 : 519 et seq.; Hillier et al. 2008 : 622 et seq.; Ross et al. 2008 : 473 et seq. However, this theory could be observed only conditionally. Cf. Graham and Harvey 2001 : 219 et seq. See further also Helwege and Liang 1996 : 457.

Cf. Ghosh and Cai 1999 : 32 et seq.; Brealey et al. 2008 : 520 et seq.

Cf. Shyam-Sunder and Myers 1999 : 219 et seq.; Brealey et al. 2008 : 521.

Cf. also Sect. 2.2.1.1 .

Cf. Hackbarth et al. 2007 , 1389 et seq. See further Teichmann 2001 : 655 et seq.

Cf. also Sect. 4.2.4.3 “ First Test Layer: International Financial Accounting Purposes ”.

Cf. Baetge et al. 2004 : 228 et seq.; Coenenberg 2009 : 1054 et seq.; Franke and Hax 2009 : 113 et seq.; Küting and Weber 2009 : 135 et seq. Furthermore, the classification of financial instruments for financial accounting purposes also affects the judgments of external financial analysts. Cf. Hopkins 1996 : 33 et seq.

Cf. Rüßmann and Vögtle 2010: 208.

Cf. in more detail Sect. 4.2.4.3 “ Debt/Equity Test ”.

Cf. Assef and Morris 2005 : 147 et seq.; Ryan 2007 : 24; Cottani and Liebentritt 2008 : 62 et seq.; Kraay and Bloom 2012 : 529 et seq. For the specific requirements in the United States see Ryan 2007 : 24 et seq. For the Australian requirements see Joseph 2006b : 231 et seq.

Cf. Santos 2001 : 52 et seq., with further references; Ryan 2007 : 24; Cottani and Liebentritt 2008 : 62 et seq.; Kraay and Bloom 2012 : 529.

Cf. Santos 2001 : 46 et seq.

Assef and Morris 2005 : 147 et seq.; Cottani and Liebentritt 2008 : 62 et seq.

Cf. e.g. Lühn 2006a : 27.

Cf. Behnes and Helios 2012 : 25 et seq.; Krause 2012 : 11; Haisch and Renner 2012: 135 et seq. See further also Becker et al. 2011 : 375 et seq.; Kraay and Bloom 2012 : 528 et seq.

However, Iceland and Israel will be neglected due to the limited scope of this thesis and the limited information basis.

Estonia is the only member state which has eliminated the ‘traditional’ corporate income tax and has introduced a distribution tax on distributed profits. Cf. IBFD 2011a : Chap. 1 (Estonia).

Cf. Bird 1996 : 1 et seq.

Cf. Endres et al. 2007 : 18 et seq.; IBFD 2011a : Sect. 1.1.4. See also McDaniel et al. 2005 : 16, for the United States; Jacobs 2009 : 92 et seq., for Germany.

Cf. Bird 1996 : 3 et seq.; Mintz 1996 : 24 et seq.; Avi-Yonah 2004 : 1200 et seq.

Cf. McLure 1979 : 20; Mintz 1996 : 25 et seq.; Avi-Yonah 2004 : 1201.

Cf. Bird 1996 : 9; Mintz 1996 : 25 et seq.

Cf. Bird 1996 : 9 et seq.

Cf. Mintz 1996 : 25 et seq.; Avi-Yonah 2004 : 1202.

Cf. Mintz 1996 : 27. See also Sect. 2.3.2 .

Cf. Avi-Yonah 2004 : 1202 et seq.

Cf. Bird 1996 : 4 et seq.; Mintz 1996 : 25.

Cf. Bird 1996 : 4 et seq.; Mintz 1996 : 25; Graetz and O’Hear 1997 : 1036 et seq. A precised benefit can be seen, for instance, in the greater liquidity granted by access to the capital market. Cf. Rudnick 1989 : 985 et seq.; Avi-Yonah 2004 : 1206 et seq., with further references.

Cf. Mintz 1996 : 25.

Cf. Avi-Yonah 2004 : 1207.

Cf. Mintz 1996 : 34; Wendt 2009 : 31.

Cf. Bird 1996 : 5.

Cf. Mintz 1996 : 35.

Cf. Avi-Yonah 2004 : 1211 et seq.; Devereux and Sørensen 2006 : 23.

Cf. Musgrave and Musgrave 1989 : 372 et seq.; Bird 1996 : 1 et seq.

Cf. Avi-Yonah 2004 : 1208, with further reference.

Cf. Avi-Yonah 2004 : 1231 et seq.; IBFD 2011a : Sect. 0.1. See also Jacobs 2009 : 92 et seq., for Germany.

Cf. Avi-Yonah 2004 : 1212 et seq., 1231 et seq.

Avi-Yonah 2004 : 1210.

Bird 1996 : 13.

For these elements in more detail see e.g. Endres et al. 2007 : 17 et seq.; Jacobs et al. 2011 : 122 et seq.

Cf. inter alia Endres et al. (eds.) 2007 : 17.

Across the globe national GAAP converges to a considerable extent. Cf. Schön 2005a : 112 et seq.

Cf. Schön 2005a : 111 et seq., 115 et seq.; Endres et al. 2007 : 25 et seq.; Wendt 2009 : 55; Ault and Arnold 2010 : 18 et seq., 38 et seq., 61, 87 et seq., 107 et seq., 164 et seq.; IBFD 2011a : Sect. 1.1.2, 1.2. See also Grimes and Maguire 2006 : 577 et seq., for the Republic of Ireland; IBFD 2011a : Sect. 12.1, for the Republic of Korea. Iceland and Israel will be neglected here and in the following due to limited information.

Cf. e.g. IAS 32 Para. 35 et seq.

Cf. e.g. IFRS Framework Para. 4.29; IAS 18 Para. 29 et seq.

Cf. IBFD 2011a : Sects. 1.2.1 and 1.4.4. See also IBFD 2011a : Sects. 2.3.1 and 2.3.3.6, for Luxembourg; IBFD 2011b : Sects. 1.3.3.2, for the United States.

For the notional interest deduction for equity implemented in Belgium see in more detail Heyvaert and Deschrijver 2005 : 459 et seq.; Vanhaute 2008 : 157 et seq.; IBFD 2011a : Sect. 1.9.6. In the past, this concept has been implemented also in Austria and Italy. Cf. inter alia de Mooij and Devereux 2011 : 97. However, Italy has recently reintroduced this concept at least for newly contributed equity. Cf. Sect. 4.2.4.2. .

In Estonia, profits before taxes are distributed, but are subsequently subject to the distribution tax. Cf. IBFD 2011a : Chap. 1.

Cf. Endres et al. 2007 : 18 et seq.; IBFD 2011a : Sects. 1.2.3 and 6.1. See also IBFD 2011a : Chaps. 9 and 11, for Luxembourg. In addition, see McDaniel et al. 2005 : 9 et seq.; IBFD 2011b : Sect. 2.2, both for the United States. Although with a partially differing division see further also de Wilde 2011 : 67.

Cf. IBFD 2011a : Chaps. 11 and 12, for Belgium and the Netherlands.

Cf. Gutiérrez et al. 2010 : Sect. 1.3.3.; HM Treasury 2010 : 14; IBFD 2011a : Sect. 1.4.5. See also IBFD 2011a : Sect. 2.3.3.4, for Luxembourg. IBFD 2011a : Chap. 12, for the Republic of Korea. In addition, see McDaniel et al. 2005 : 7 et seq., 11; IBFD 2011b : Sect. 1.3.3.1, both for the United States. See further also Wendt 2009 : 82.

Cf. Sects. 4.2.3.1 and 4.2.4.1 . See also instead of many Wendt 2009 : 82 et seq.; IBFD 2011a : Sect. 10.3; Jacobs et al. 2011 : 980 et seq., 1008 et seq.; de Wilde 2011 : 67 et seq. Nevertheless, these interest deduction limitation mechanisms are not within the scope of this thesis and will not be further considered.

Cf. Gutiérrez et al. 2010 : Sect. 1.3.; IBFD 2011a : Sect. 1.2. For the Republic of Korea see IBFD 2011a : Sect. 14; for Luxembourg IBFD 2011a : Sect. 2.3. For the United States see McDaniel et al. 2005 : 7; IBFD 2011b : Sects. 1.3.1 and 1.3.2. See further also Endres et al. 2007 : 31.

Cf. in more detail for Hungary Felkai 2009 : 611 et seq. See also Dikmans 2007 : 162 et seq.; Storck 2011 : 35 et seq.; Smit et al. 2011 : 508 et seq., all for the Netherlands. For the Dutch group interest box see e.g. Flipsen and Burgers 2010 : 22 et seq.

Cf. Sect. 2.3.2.2 .

Cf. Jacobs et al. 2011 : 6 et seq. See also Schäfer 2006 : 31 et seq.; Panayi 2007 : 2 et seq.; Wendt 2009 : 91 et seq., all with further references.

Cf. Jacobs et al. 2011 : 10 et seq. See also Braunagel 2008 : 35 et seq.

For the mechanisms to avoid/mitigate the economic double taxation see also Sect. 2.3.1.2 .

Cf. Sect. 3.1.3.

Cf. Sect. 2.3.1.2 .

Cf. IBFD 2011a : Sect. 7.2.1.

Cf. Tables A.2 and A.3, both in the annex; IBFD 2011b : Sects. 6.3.1 and 6.3.5.

Additionally, dividends paid to non-resident pension funds, investment funds and/or insurance companies may be exempted from withholding tax in some countries (e.g. in Poland and Slovenia).

For the precise withholding tax rates on dividends (portfolio shareholding) of the agreed income tax treaties between all regarded EEA/EU/OECD Member States see Table A.2 in the annex.

For the precise withholding tax rates on dividends (substantial shareholding) of the agreed income tax treaties between all regarded EEA/EU/OECD Member States see Table A.3 in the annex.

Cf. Council Directive, 90/435/EEC: 6, as lastly amended by Council Directive, 2003/123/EC: 41. See in more detail Sect. 4.2.1.2 ; Jacobs et al. 2011 : 167 et seq.

Cf. IBFD 2011a : Sect. 7.2.1. In some countries exceptions for specific types of income are made under domestic tax law by the application of the territoriality principle. See IBFD 2011a : Sect. 7.2.1 (Denmark); IBFD 2011a : Sect. 7.2.1 (France). See also Gouthière 2011 : 188, 191 et seq., for France.

Cf. IBFD 2011a : Chap. 7; IBFD 2011b : Chap. 6. See also Bieber et al. 2008 : 583 et seq., for Austria; IBFD 2011a : Chap. 8, for Luxembourg. In Austria, from 2011 the tax exemption method for portfolio participations shall be extended to apply as well to Non-EEA/EU-situations. Cf. IBFD 2011b : Sect. 6.1 (Austria).

Corporations in the United Kingdom may elect for a non-application of the tax exemption method, but contemporaneously for an avoidance of jurisdiction double taxation.

Corporations in the United Kingdom may elect for a non-application of the tax exemption method, but contemporaneously for direct and indirect tax credits.

These limitations may be used either in a cross-border situation or, in addition, in a pure domestic context as already indicated above. Cf. Zielke 2010 : 69 et seq.; IBFD 2011a : Sect. 10.3. Nevertheless, these regimes are not within the scope of this thesis and will not be further considered.

Cf. Sects. 4.2.3.2 and 4.2.4.2 .

Cf. IBFD 2011b : Sects. 6.3.2 and 6.3.5.

For the precise withholding tax rates on interest payments of the agreed upon income tax treaties between all regarded EEA/EU/OECD Member States see Table A.4 in the annex.

Cf. Council Directive, 2003/49/EC: 49. See in more detail Sect. 4.2.1.2 ; Jacobs et al. 2011 : 179 et seq.

Ackermann U, Jäckle J (2006) Ratingverfahren aus Emittentensicht. Betriebs-Berater 878–884

Google Scholar

Allen F (1989) The changing nature of debt and equity: a financial perspective. In: Kopcke RW, Rosengren ES (eds) Are the distinctions between debt and equity disappearing? Proceedings of a conference held at Melvin Village, New Hampshire, pp 12–38

Allen F, Gale D (1994) Financial innovation and risk sharing. Cambridge

Allen F, Santomero AM (1998) The theory of financial intermediation. J Bank Financ 1461–1485

Alworth JS (1998) Taxation and integrated financial markets: the challenges of derivatives and other financial innovations. Int Tax Public Financ 507–534

Arouri MElH, Jawadi F, Nguyen DK (2010) The dynamics of emerging stock markets: empirical assessments and implications. Berlin/Heidelberg

Assef S, Morris D (2005) Transfer pricing implications of the basel II capital accord. Deriv Financ Instrum 147–151

Ault HJ, Arnold BJ (eds) (2010) Comparative income taxation, 3rd edn. The Hague

Avi-Yonah R (2004) Corporations, society, and the state: a defense of the corporate tax. Va Law Rev 1193–1255

Baetge J, Kirsch H-J, Thiele S (2004) Bilanzanalyse, 2nd edn. Düsseldorf

Baxter ND (1967) Leverage, risk of ruin and the cost of capital. J Financ, 395–403

Becker B et al (2011) Basel III und die möglichen Auswirkungen auf die Unternehmensfinanzierung. Deutsches Steuerrecht 375–380

Behnes S, Helios M (2012) Steuerliche Aspekte der CRD IV. Recht der Finanzinstrumente 25–33

Benshalom I (2010) How to live with a tax code with which you disagree? Doctrine, optimal tax, common sense and the debt and equity distinction. N C Law Rev 1217–1274

Bieber T, Haslehner W, Kofler G, Schindler CP (2008) Taxation of cross-border portfolio dividends in Austria: the Austrian Supreme Administrative Court interprets EC law. Eur Tax 583–589

Bird RM (1996) Why tax corporations?, Working paper no. 96-2 prepared for the Technical Committee on Business Taxation, Ottawa

Blaurock U (2007) Verantwortlichkeit von Ratingagenturen – Steuerung durch Privat- oder Aufsichtsrecht?. Zeitschrift für Unternehmens- und Gesellschaftsrecht 603–653

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2010), Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States. http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/current/z1.pdf . Accessed 2 Feb 2011

Bock C (2010) Vorteilhaftigkeit hybrider Finanzinstrumente gegenüber klassischen Finanzierungsformen unter Unsicherheit. Wiesbaden

Bodie Z (1989) The lender’s view of debt and equity: the case of pension fund. In: Kopcke RW, Rosengren ES (eds) Are the distinctions between debt and equity disappearing?, Proceedings of a conference held at Melvin Village, New Hampshire, pp 106–121

Bogenschütz E (2008a) Hybride Finanzierungen im grenzüberschreitenden Kontext. Die Unternehmensbesteuerung 533–543

Bogenschütz N (2008b) Neuausrichtung des Eigenkapitalbegriffs: dogmatische Überlegungen im Lichte hybrider Finanzierungen. Frankfurt am Main

Bourtourault P-Y, Bénard M (2011) French tax aspects of cross-border restructuring. Bull Int Tax 179–187

Bradley M, Jarrell GA, Han Kim E (1984) On the existence of an optimal capital structure: theory and evidence. J Financ 857–878

Braunagel RU (2008) Gemeinsame Körperschaftsteuer-Bemessungsgrundlage in der EU. Lohmar/Cologne

Brealey RA, Myers SC, Allen F (2008) Principles of corporate finance, 9th edn. Boston

Briesemeister S (2006) Hybride Finanzinstrumente im Ertragsteuerrecht, Düsseldorf

Brinkmann J (2007) Die Informationsfunktion der Rechnungslegung nach IFRS – Anspruch und Wirklichkeit. Teil I: Anforderungen an informationsvermittelnde Rechenwerke. Zeitschrift für Corporate Governance 228–232

Bulow JI, Summers LH, Summers VP (1990) Distinguishing debt from equity in the junk bond era. In: Shoven J, Waldfogel J (eds) Debt taxes and corporate restructuring. Washington, DC, pp 135–166

Bundgaard J (2010a) Classification and treatment of hybrid financial instruments and income derived therefrom under EU corporate tax directives – part 1. Eur Tax 442–456

Cerny PG (1994) The dynamics of financial globalization: technology, market structure, and policy response. Policy Sci 319–342

Coenenberg AG (2009) Jahresabschluss und Jahresabschlussanalyse. Betriebswirtschaftliche, handelsrechtliche, steuerrechtliche und internationale Grundsätze – HGB, IFRS und US-GAAP, 21th edn. Stuttgart

Cotei C, Farhat J (2009) The trade-off theory and the pecking order theory: are they mutually exclusive?. N Am J Financ Bank Res 1–16

Cottani G, Liebentritt M (2008) Tier 1 capital instruments: regulatory and tax issues. Deriv Financ Instrum 62–74

Cuzmann I, Dima B, Dima SM (2010) IFRSs for financial instruments, quality of information and capital market’s volatility: an empirical assessment for Eurozone. J Account Manage Inform Syst 284–304

De Mooij RA, Devereux MP (2011) An applied analysis of ACE and CBIT reforms in the EU. Int Tax Public Financ 93–120

De Wilde MF (2011) A step towards a fair corporate taxation of groups in the emerging global market. Intertax 62–84

DeAngelo H, Masulis R (1980) Optimal capital structure under corporate and personal taxation. J Financ Econ 3–29

Devereux M, Sørensen P (2006) The corporate income tax: international trends and options for fundamental reforms, European economy, European commission, directorate-general for economic and financial affairs, Economic papers no. 264, Brussels

Dikmans S (2007) New Netherlands corporate income tax provisions for 2007. Eur Tax 158–167

Dombek M (2002) Die Bilanzierung von strukturierten Produkten nach deutschem Recht und nach den Vorschriften des IASB. Die Wirtschaftsprüfung 1065–1074

Drukarczyk J (1993) Theorie und Politik der Finanzierung, 2nd edn. Munich

Duncan JA (2000) General report. In: IFA (ed) Tax treatment of hybrid financial instruments in cross-border transactions, vol 85a. The Hague, pp 21–34

Eber-Huber H (1996) Introduction. In: Bureau Francis Lefebvre, Loyens & Volkmaars, Oppenhoff & Rädler (eds) Hybrid Financing. pp 7–14

Edgar T (2000) Income tax treatment of financial instruments: theory and practice. Toronto

Eidenmüller H (2007) Forschungsperspektiven im Unternehmensrecht. Zeitschrift für Unternehmens- und Gesellschaftsrecht 484–499

Eilers S, Rödding A (2007) Neue Finanzierungsinstrumente für den Mittelstand im Steuerrecht. In: Piltz DJ, Günkel M, Niemann U (eds) Steuerberater-Jahrbuch 2006/2007. pp 81–104

Eiteman DK, Stonehill AI, Moffett MH (2010) Multinational business finance, 12th edn. Boston

Elschen R (1993) Eigen- und Fremdfinanzierung – Steuerliche Vorteilhaftigkeit und betriebliche Risikopolitik. In: Gebhardt G, Gerke W, Steiner M (eds) Handbuch des Finanzmanagements. München, pp 585–617

Emmerich AO (1985) Hybrid instruments and the debt-equity distinction in corporate taxation. Univ Chicago Law Rev 118–148

Endres D et al (eds) (2007) Determination of corporate taxable income in the EU Member States. Alphen aan den Rijn

European Commission (2004b) Fostering an appropriate regime for shareholders’ rights, consultation document of the services of the Internal Market Directorate General, 16.9.2004. http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/company/docs/shareholders/consultation_en.pdf . Accessed 31 Mar 2011

Fama EF (1980) Banking in the theory of finance. J Monet Econ 39–58

Felkai R (2009) Hungary – 2010 tax changes. Eur Tax 611–613

Finnerty JD (1988) Financial innovation: an overview. Financ Manage 14–33

Flipsen P, Burgers O (2010) Proposed changes to the Dutch corporate income tax act (CITA). Int Tax J 21–26

Frank MZ, Goyal VK (2003) Testing the pecking order theory of capital structure. J Financ Econ 217–248

Franke G, Hax H (2009) Finanzwirtschaft des Unternehmens und Kapitalmarkt, 6th edn. Heidelberg

Friderichs H, Körting T (2011) Die Rolle der Bankkredite im Finanzierungsspektrum der deutschen Wirtschaft. Wirtschaftsdienst 31–38

Fukao M, Hanazaki M (1986) Internationalisation of Financial Markets, OECD Economics Department working papers no. 37, Paris

Funk TE (1998) Hybride Finanzinstrumente im US-Steuerrecht. Recht der Internationalen Wirtschaft, 138–145

Gebhardt G, Gerke W, Steiner M (1993) Ziele und Aufgaben des Finanzmanagements. In: Gebhardt G, Gerke W, Steiner M (eds) Handbuch des Finanzmanagements. München, pp 1–23

German Institute of Public Auditors (2008) IDW Stellungnahme zur Rechnungslegung: Zur einheitlichen oder getrennten handelsrechtlichen Bilanzierung strukturierter Finanzinstrumente (IDW RS HFA 22). In: Institut der Wirtschaftsprüfer Fachnachrichten No. 10/2008, pp 455–459

Ghosh A, Cai F (1999) Capital structure: new evidence of optimality and pecking order theory. Am Bus Rev 32–38

Gouthière B (2011) Key practical issues in eliminating the double taxation of business income. Bull Int Tax 188–198

Graetz MJ, Grinberg I (2003) Taxing international portfolio income. Tax Law Rev 537–586

Graetz MJ, O’Hear MM (1997) The “original intent” of U.S. international taxation. Duke Law J 1022–1109

Graham JR (2000) How big are the tax benefits of debt?. J Finance 1901–1941

Graham JR, Harvey CR (2001) The theory and practice of corporate finance: evidence from the field. J Financ Econ 187–243

Griffith R, Hines JR Jr, Sørensen PB (2010) International Capital Taxation. In: Mirrless J et al (eds) Dimensions of tax design. The Mirrless review. Oxford/New York, pp 914–996

Grimes L, Maguire T (2006) The adoption of international financial reporting standards for tax purposes by Ireland. Eur Tax 577–582

Grinblatt M, Titman S (2002) Financial markets and corporate strategy, 2nd edn. Boston

Gutiérrez C et al (eds) (2010) Global corporate tax handbook 2010. Amsterdam

Hackbarth D, Hennessy CA, Leland HE (2007) Can the trade-off theory explain debt structure?. Rev Financ Stud 1389–1428

Haggard S, Maxfield S (1996) The political economy of financial internationalization in the developing world. Int Org 35–68

Hariton DP (1988) The taxation of complex financial instruments. Tax Law Rev 731–788

Hariton DP (1994) Distinguishing between equity and debt in the new financial environment. Tax Law Rev 499–524

Hartmann-Wendels T, Pfingsten A, Weber M (2010) Bankbetriebslehre, 5th edn. Berlin/Heidelberg

Haun J (1996) Hybride Finanzierungsinstrumente im deutschen und US-amerikanischen Steuerrecht. Frankfurt am Main

Heathcotea J, Perri F (2004) Financial globalization andreal regionalization. J Econ Theory 207–243

Helminen M (2010) The international tax law concept of dividend. Alphen aan den Rijn

Helwege J, Liang N (1996) Is there a pecking order? Evidence from a panel of IPO firms. J Financ Econ 429–458

Herman D (2002) Taxing portfolio income in global financial markets. Amsterdam

Heyvaert W, Deschrijver D (2005) Belgium stimulates equity financing. Intertax 458–465

Hillier D, Grinblatt M, Titman S (2008) Financial markets and corporate strategy. London

Hines JR (2007) Corporate taxation and international competition. In: Auerbach A, Hines JR, Slemrod J (eds) Taxing corporate income in the 21st century 2007. pp 268–295

Hopkins PE (1996) The effect of financial statement classification of hybrid financial instruments on financial analysts’ stock price judgments. J Account Res 33–50

Horst T (2011) How to determine tax-deductible, debt-related costs for a subsidiary. Tax Notes Int 589–603

Hull JC (2009) Options, futures, and other derivatives, 7th edn. Upper Saddle River

IBFD (2011a) Country analyses – corporate taxation. http://www.ibfd.org

IBFD (2011b) Country surveys – corporate taxation. http://www.ibfd.org

Jacobs OH (ed) (2009) Unternehmensbesteuerung und Rechtsform, 4th edn. Munich

Jacobs OH, Haun J (1995) Financial derivatives in international tax law – a treatment of certain key considerations. Intertax 405–420

Jacobs OH, Endres D, Spengel C (eds) (2011) Internationale Unternehmensbesteuerung, Deutsche Investitionen im Ausland – Ausländische Investitionen im Inland, 7th edn. Munich

Jänisch C, Moran K, Waibel N (2002) Mezzanine-Finanzierung – Intelligentes Fremdkapital und deutsches Steuerrecht. Der Betrieb 2451–2456

Joseph A (2006b) Securization, capital adequacy and impact of IFRS, FASB 140 and FIN 46R. Deriv Financ Instrum 231–235

Kalss S (2007) Maßgebliche Forschungsfelder in der nächsten Dekade im Bereich des Gesellschafts- und Kapitalmarktrechts. Zeitschrift für Unternehmens- und Gesellschaftsrecht 520–531

Kessler W, Kröner M, Köhler S (eds) (2008) Konzernsteuerrecht, 2nd edn. Munich

Kopcke RW, Rosengren ES (1989) Are the distinctions between debt and equity disappearing? An overview. In: Kopcke RW, Rosengren ES (eds) Are the distinctions between debt and equity disappearing?, Proceedings of a conference held at Melvin Village, New Hampshire, pp 1–11

Kose MA et al (2006) Financial globalization: a reappraisal, IMF working paper no. 06/189, Washington, DC

Kraay N, Bloom, L (2012) The missing link: transfer pricing and regulatory capital compliance for global financial institutions. Tax Notes Int 527–531

Krause H (2006) Die Besteuerung hybrider Finanzinstrumente. Frankfurt am ain

Krause M (2012) Basel III: the regulatory framework. Deriv Financ Instrum 11–16

Küting K, Weber C-P (2009) Die Bilanzanalyse: Beurteilung von Abschlüssen nach HGB und IFRS. 9th edn. Stuttgart

Küting K, Erdmann M-K, Dürr UL (2008) Ausprägungsformen von Mezzanine-Kapital in der Rechnungslegung nach IFRS (Teil I). Der Betrieb 941–948

Lampreave P (2011) Fiscal competitiveness versus harmful tax competition in the European union. Bull Int Tax, 17 et seq. http://www.ibfd.org . Accessed 28 Aug 2011

Lang M (1991) Hybride Finanzierungen im Internationalen Steuerrecht. Vienna

Laukkanen A (2007) Taxation of investment derivatives. Amsterdam

Ledure D et al (2010) Financial transactions in today’s world: observations from a transfer pricing perspective. Intertax 350–358

Lothian JR (2002) The internationalization of money and finance and the globalization of financial markets. J Int Money Financ 699–724

Lühn M (2006a) Bilanzierung und Besteuerung von Genussrechten. Wiesbaden

Luttermann C (2001) Aktienverkaufoptionsanleihen (“reverse convertible notes”), standardisierte Information und Kapitalmarktdemokratie. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsrecht 1901–1906

MacNeil I (2005) An introduction to the law on financial investment. Oxford/Portland

Mäntysaari P (2010) The law of corporate finance: general principles and EU law. Volume III: funding, exit, takeovers. Heidelberg

Martínez Bárbara G (2011) The role of good governance in the tax systems of the European union. Bull Int Tax 270–280

McDaniel PR, Ault HJ, Repetti JR (2005) Introduction to United States international taxation, 5th edn. New York

McLure CE (1979) Must corporate income be taxed twice?. Washington, DC

Miller MH (1977) Debt and taxes. J Financ 261–275

Miller MH (1986) Financial innovation: the last twenty years and the next. J Financ Quant Anal 459–471

Mintz J (1996) Corporation tax: a survey. Fiscal Stud 23–68

Modigliani F, Miller M (1958) The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. Am Econ Rev 261–297

Modigliani F, Miller M (1963) Corporate income taxes and the cost of capital: a correction. Am Econ Rev 433–443

Murre, D. (2012) The European financial transaction tax: issues for derivatives, structured products and securization. Deriv Financ Instrum 25–31

Musgrave RA, Musgrave PB (1989) Public finance in theory and practice, 5th edn. New York

Myers SC (1984) The capital structure puzzle. J Financ 575–592

Myers SC (2001) Capital structure. J Econ Perspect 81–102

Myers SC, Majluf NS (1984) Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. J Financ Econ 187–221

Natusch I (2007) Wirtschaftliche Grundlagen. In: Häger M, Elkemann-Reusch M (eds) Mezzanine Finanzierungsinstrumente. Berlin, pp 21–69

Normandin CP (1989) The changing nature of debt and equity: a legal perspective. In: Kopcke RW, Rosengren ES (eds) Are the distinctions between debt and equity disappearing?, Proceedings of a conference held at Melvin Village, New Hampshire, pp 49–66

Noulas A, Genimakis G (2011) The determinants of capital structure choice: evidence from Greek listed companies. Appl Financ Econ 379–387

OECD (1994) Taxation of new financial instruments. Paris

OECD (2009) OECD in figures. Paris

Panayi CHJI (2007) Double taxation, tax treaties, treaty-shopping and the European community. Alphen aan den Rijn

Perridon L, Steiner M, Rathgeber AW (2009) Finanzwirtschaft der Unternehmung, 15th edn. Munich

Pistone P, Romano C (2001) Short report on the proceedings of the 54th IFA congress, Munich 2000, Bulletin, pp 35–42

Polito AP (1998) Useful ficitons: debt and equity classification in corporate tax law. Ariz State Law J 761–810

Pratt K (2000) The debt-equity distinction in a second-best world. Vanderbilt Law Rev 1055–1158

Rajan RG, Zingales L (1991) What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international Data. J Financ 1421–1460

Ramsler M (1993) Finanzinnovationen. In: Gebhardt G, Gerke W, Steiner M (eds) Handbuch des Finanzmanagements. München, pp 429–444

Reiner G, Schacht JA (2010) Credit Default Swaps und verbriefte Kreditforderungen in der Finanzmarktkrise. Bemerkungen zum Wesen verbindlicher und unverbindlicher Risikoverträge. Teil II. Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts- und Bankrecht 385–436

Roos SA et al (2008) Modern financial management, 8th edn. Boston

Rudnick RS (1989) Who should pay the corporate tax in a flat tax world?. Case West Reserve Law Rev 965–1209

Rudolf S (2005) Entwicklungen im Kapitalmarkt Deutschland. In: Habersack M, Mülbert PO, Schlitt M (eds) Unternehmensfinanzierung am Kapitalmarkt, pp 1–37

Rudolph B (2006) Unternehmensfinanzierung und Kapitalmarkt. Tübingen

Ryan SG (2007) Financial instruments and institutions, 2nd edn. Hoboken

Santangelo RA (1997) Towards reshaping the debt-equity distinction. J Corp Tax 312–341

Santos JAC (2001) Bank capital regulation in contemporary banking theory: a review of the literature. Financ Market Inst Instrum 41–84

Schaber M, Rehm K, Märkl H (2008) Handbuch strukturierter Finanzinstrumente. Düsseldorf

Schäfer A (2006) International company taxation in the era of information and communication technologies: issues and options for reform. Wiesbaden

Schneider D (1992) Investitionen, Finanzierung und Besteuerung, 7th edn. Wiesbaden

Schön W (2005a) The odd couple: a common future for financial and tax accounting?. Tax Law Rev 111–148

Schrell TK, Kirchner A (2003) Mezzanine Finanzierungsstrategien. Zeitschrift für Bank- und Kapitalmarktrecht 13–20

Schulz M (2006) Wandelanleihen in der Unternehmensfinanzierung. Hamburg

Scott JH Jr (1976) A theory of optimal capital structure. Bell J Econ 33–54

Semer SL (2010) Understanding the real purpose of financial derivatives. Tax Notes 1478–1481

Shaviro DN (1995) Risk-based rules and the taxation of capital income. Tax Law Rev 643–724

Sheppard LA (2011) Do corporate tax rates matter?. Tax Notes 1105–1110

Shyam-Sunder L, Myers SC (1999) Testic static trade-off against pecking-order theories of capital structure. J Financ Econ 219–244

Siemens AG (2010a) Company report 2010. http://www.siemens.com/annual/10/_pdf/Siemens_AR2010_CompanyReport.pdf . Accessed 3 Mar 2011

Siemens AG (2010b) Financial report 2010. http://www.siemens.com/annual/10/_pdf/Siemens_AR2010_FinancialReport.pdf . Accessed 3 Mar 2011

Smit PM, van Strien J, Valkenburg JW (2011) Netherlands government bites the bullet: fiscal agenda – tax policy and reform announcements. Bull for Int Tax 508–513

Storck A (2011) The Financing of multinational companies and taxes: an overview of the issues and suggestions for solutions and improvements. Bull Int Tax 27–41

Storck A, Spori P (2008) Konzernfinanzierung in der Schweiz – Fakten und Steuern. Forum für Steuerrecht 249–265

Teichmann C (2001) Corporate Governance in Europa. Zeitschrift für Unternehmens- und Gesellschaftsrecht 645–679

HM Treasury (2010) Part 1: the corporate tax road map. http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/corporate_tax_reform_part1a_roadmap.pdf . Accessed 21 April 2011

Valdez S, Molyneux P (2010) An introduction to global financial markets, 6th edn. New York

Van Horne JC (1985) Of financial innovation and excesses. J Financ 621–631

Vanhaute PAA (2008) Belgium in international tax planning, 2nd edn. Amsterdam

Wagner S (2005c) Bilanzierungsfragen und steuerliche Aspekte bei “hybriden” Finanzierungen. Der Konzern 499–510

Wald JK (1999) How firm characteristics affect capital structure: an international comparison. J Financ Res 161–187

Warren AC Jr (1993) Financial contract innovation and income tax policy. Harv Law Rev 460–492

Waschbusch G, Knoll J, Druckenmüller J (2009) Mittelstandsfinanzierung: Finanzierung mit Fremdkapital – Ist die klassische Kreditfinanzierung noch zeitgemäß. Die Steuerberatung 351–358

Wendt C (2009) A common tax base for multinational enterprises in the European union. Wiesbaden

Wiehe H, Jordans R, Roser E (2007) Mezzanine Finance Structures under German Law. J Int Bank Law Regul 218–223

Wüstemann J, Bischof J (2011) Eigenkapital im nationalen und internationalen Bilanzrecht: Eine ökonomische Analyse. Zeitschrift für das gesamte Handelsrecht und Wirtschaftsrecht 210–246

Zielke R (2010) Shareholder debt financing and double taxation on the OECD: an empirical survey with recommendations for the further development of the OECD model and international tax planning. Intertax 62–92

Zodrow GR (2010) Capital mobility and capital tax competition. Natl Tax J 865–902

Haisch M, Renner D (2012) Auswirkungen von Basel III auf hybride Instrumente in der Handels- und Steuerbilanz. In: Der Betrieb p. 135–141

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Business School Chair of International Taxation, University of Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany

Sven-Eric Bärsch

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sven-Eric Bärsch .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Bärsch, SE. (2012). Background of Financial Instruments. In: Taxation of Hybrid Financial Instruments and the Remuneration Derived Therefrom in an International and Cross-border Context. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-32457-4_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-32457-4_2

Published : 15 September 2012

Publisher Name : Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN : 978-3-642-32456-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-642-32457-4

eBook Packages : Business and Economics Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

FinancialInstruments →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is a Financial Instrument?

Understanding financial instruments, types of financial instruments, types of asset classes of financial instruments.

- Financial Instruments FAQs

The Bottom Line

- Investing Basics

Financial Instruments Explained: Types and Asset Classes

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/wk_headshot_aug_2018_02__william_kenton-5bfc261446e0fb005118afc9.jpg)

Gordon Scott has been an active investor and technical analyst or 20+ years. He is a Chartered Market Technician (CMT).

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/gordonscottphoto-5bfc26c446e0fb00265b0ed4.jpg)

Katrina Ávila Munichiello is an experienced editor, writer, fact-checker, and proofreader with more than fourteen years of experience working with print and online publications.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/KatrinaAvilaMunichiellophoto-9d116d50f0874b61887d2d214d440889.jpg)

Financial instruments are assets that can be traded, or they can also be seen as packages of capital that may be traded. Most types of financial instruments provide efficient flow and transfer of capital throughout the world’s investors . These assets can be in the form of cash, a contractual right to deliver or receive cash or another type of financial instrument, or evidence of one’s ownership in some entity.

Examples of financial instruments include stocks, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), bonds, certificates of deposit (CDs), mutual funds, loans, and derivatives contracts, among others.

Key Takeaways

- A financial instrument is a real or virtual document representing a legal agreement involving any kind of monetary value.

Financial instruments may be divided into two types: cash instruments and derivative instruments.

- Financial instruments may also be divided according to an asset class, which depends on whether they are debt-based or equity-based.

- Foreign exchange instruments comprise a third, unique type of financial instrument.

Madelyn Goodnight / Investopedia

Financial instruments can be real or virtual documents representing a legal agreement involving any kind of monetary value. Equity-based financial instruments represent ownership of an asset. Debt-based financial instruments represent a loan made by an investor to the owner of the asset.

Foreign exchange instruments comprise a third, unique type of financial instrument. Different subcategories of each instrument type exist, such as preferred share equity and common share equity.

International Accounting Standards (IAS) define financial instruments as “any contract that gives rise to a financial asset of one entity and a financial liability or equity instrument of another entity.”

Cash Instruments

- The values of cash instruments are directly influenced and determined by the markets. These can be securities that are easily transferable. Stocks and bonds are common examples of such primary instruments .

- Cash instruments may also be deposits and loans agreed upon by borrowers and lenders . Checks are an example of a cash instrument because they transmit payment from one bank account to another.

Derivative Instruments

- The value and characteristics of derivative instruments are based on the vehicle’s underlying components, such as assets, interest rates, or indices.

- An equity options contract—such as a call option on a particular stock, for example—is a derivative because it derives its value from the underlying shares. The call option gives the right, but not the obligation, to buy shares of the stock at a specified price and by a certain date. As the price of the underlying stock rises and falls, so does the value of the option, although not necessarily by the same percentage.

- There can be over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives or exchange-traded derivatives. OTC is a market or process whereby securities—which are not listed on formal exchanges—are priced and traded.

Financial instruments may also be divided according to an asset class , which depends on whether they are debt-based or equity-based.

Debt-Based Financial Instruments

Debt-based instruments are essentially loans made by an investor to the owner of the asset. Short-term debt-based financial instruments last for one year or less. Securities of this kind come in the form of Treasury bills (T-bills) and commercial paper . Bank deposits and certificates of deposit (CDs) are also technically debt-based instruments that credit depositors with interest payments.

Exchange-traded derivatives exist for short-term, debt-based financial instruments, such as short-dated interest rate futures. OTC derivatives also exist, such as forward rate agreements (FRAs) .

Long-term debt-based financial instruments last for more than a year. Long-term debt securities are typically issued as bonds or mortgage-backed securities (MBS) . Exchange-traded derivatives on these instruments are traded in the form of fixed-income futures and options. OTC derivatives on long-term debts include interest rate swaps, interest rate caps and floors, and long-dated interest rate options.

Equity-Based Financial Instruments

Equity-based instruments represent ownership of an asset. Securities that trade under the banner of equity-based financial instruments are most often stocks , which can be either common stock or preferred shares. ETFs and mutual funds may also be equity-based instruments.

Exchange-traded derivatives in this category include stock options and equity futures.

Foreign Exchange Instruments

Foreign exchange (forex, or FX) instruments include derivatives such as forwards , futures , and options on currency pairs , as well as contracts for difference (CFDs) . Currency swaps are another common form of forex instrument. In addition, forex traders may engage in spot transactions for the immediate conversion of one currency into another.

What Are Some Examples of Financial Instruments?

Financial instruments come in many forms and types. What makes them financial instruments is that they confer a financial obligation or right to the holder . Common examples of financial instruments include stocks, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), mutual funds, real estate investment trusts (REITs) , bonds, derivatives contracts (such as options, futures, and swaps), checks, certificates of deposit (CDs), bank deposits, and loans.

Are Commodities Financial Instruments?

While commodities themselves, such as precious metals, energy products, raw materials, or agricultural products, are traded on global markets, they do not typically meet the definition of a financial instrument. That’s because they do not confer a claim or obligation over something else. But commodities derivatives are financial instruments, They include futures, forwards, and options contracts that use a commodity as the underlying asset.

Are Insurance Policies Financial Instruments?

An insurance policy is a legally binding contract established with the insurance company and policy owner that provides monetary benefits if certain conditions are met (e.g., death in the case of life insurance). If the insurer is a mutual company, the policy may also confer ownership and a claim to dividends. Insurance policies also have a specified value in terms of both the death benefit and living benefits (e.g., cash value) for permanent policies.

Insurance policies are not considered securities, but one could possibly view them as an alternative type of financial instrument because they confer a claim and certain rights to the policyholder and obligations to the insurer.

A financial instrument is effectively a monetary contract (real or virtual) that confers a right or claim against some counterparty in the form of a payment ( checks , bearer instruments ), equity ownership or dividends (stocks), debt (bonds, loans, deposit accounts), currency (forex), or derivatives (futures, forwards, options, and swaps). Financial instruments can be segmented by asset class and as cash-based, securities, or derivatives.

Depending on their type, financial instruments may be exchangeable on listed or OTC markets.

Emanuel Camilleri and Roxanne Camilleri, via Google Books. “ Accounting for Financial Instruments: A Guide to Valuation and Risk Management .” Page 62. Taylor & Francis, 2017.

Corporate Finance Institute. " Financial Instrument ."

FinancialEdge. " Derivative Financial Instruments ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/78036503-5bfc2b8b4cedfd0026c118ed.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Financial Instruments: The Main Types Term Paper

Introduction.

Generally, in active financial markets business organizations depend on financial instruments (FI) such as bonds, and equities to help them reduce potential risks they might encounter during their operations. For instance, issues such as increasing interest rates and changes in commodity prices are more likely to affect enterprises thus they rely on the various forms of securities to reduce the impacts. Apart from the aspect of reducing potential business hazards, the FIs are useful in enabling business owners to generate the required capital. In most cases, companies trade shares to raise additional funds for their operations. The approach allows investors to own a portion of the respective business organization. Therefore, the concept of FI is an essential facet of the money market hence it is necessary to have proper knowledge about it to ensure effective financial reporting by enterprises.

The Concept of FI

The term FI refers to a form of assets that can be traded in the money market. In financial institutions, FI provides an effective and efficient flow of funds from different investors across the world. In other words, FI can be defined as either a virtual or real document that represents a legal arrangement involving any form of monetary value between two or more parties (Stolowy & Ding, 2017). In general, FI is a contract for a monetary value that can be created, modified, purchased, or even settled. In terms of the agreement, FI requires a contractual obligation between the people or institutions involved in the transactions of FI. In other words, FI encompasses a two-way commitment whereby each party must comply with the agreed conditions. For instance, assuming a company is supposed to obtain cash from investors, it will be required to provide shares for the respective financier while the individual is obligated to issue the arranged funds.

Types and Categories of FI

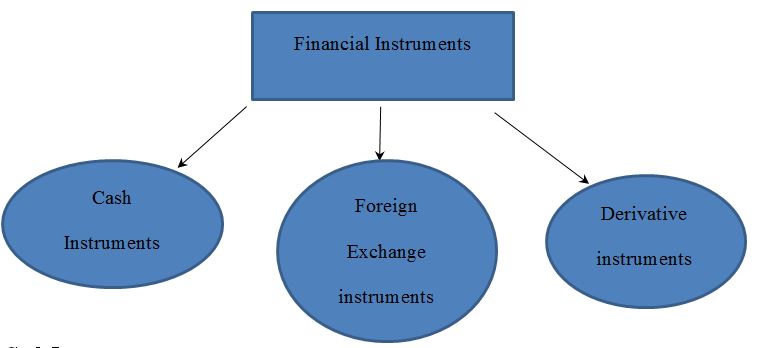

The FI are grouped into two broad types namely; derivative instruments, cash instruments, and foreign exchange instruments as shown in figure 1 below. Each of the categories functions differently making them unique from one another. Furthermore, the FI is categorized into two main asset classes which are debt-based FI and equity-based FI (Kańduła & Przybylska, 2021). The mentioned sets make the FI have wide functions that enable business organizations and potential investors to achieve their objectives in the money market.

Cash Instruments

Cash instruments are types of FI whose values are impacted directly by the prevailing condition of the general market. This type of FI further known as cash equivalents is categorized into additional two groups. The classes include securities and loans, and deposits which investors and business organizations can choose from depending on their needs in the financial market (Parameswaran, 2022). Generally, securities are FI that has monetary value and are mostly traded in the stock exchange market (SEM). There are a number of marketable securities that investors and business organizations can opt to purchase or buy in the money market. They include bonds, stocks, preferred shares, and debentures. When the given securities are purchased, they represent a significant portion of the publicly-traded enterprise in the SEM. In addition, the other category of cash instruments that are loans and deposits represent assets having monetary value. The cash equivalents require parties involved to have a well-formulated contractual agreement to which the participants must adhere to.

Derivate Instruments

Derivative instruments are FI that derive their values or performance from the underlying asset. Some of the underlying assets that can determine the values of derivatives include commodities such as oil, gold, and cotton. Other assets are stocks, interest rates, currencies, bonds, and market indices (Parameswaran, 2022). The mentioned items have the potential of influencing the creation of different financial derivatives in the market. Derivative instruments are classified into five main categories namely; options, future, interest rate swaps, and forwards. In most cases, the derivatives mentioned above are used for the precautionary purpose to enable business organizations and investors to manage possible risks and further facilitate the aspect of speculation in the market (Kang, 2019). Generally, the given types of derivatives fall into two broad classes known as option and lock.

A future is a contract between two parties that is buyer and seller for the purchase of an asset at a pre-determined exchange rate in the future. In most cases, the derivate is used by traders to enable them to hedge possible risks that are likely to occur. Furthermore, a future contract allows investors to speculate the forthcoming price of the underlying asset (Dungore et al., 2022). Based on the agreement, both participants are obligated to accomplish the commitment to sell or buy the given commodity.

Based on the concept of derivative instruments, an option is a FI whereby two parties agree on a given contract to undertake a transaction of an asset at an already determined price before the future date. In other words, the FI permits the owner of the asset to sell or buy the underlying asset at the specified exercise price. In this type of derivative, the buyer is limited from engaging in the buy or sell agreement. The different options include selling a call option, selling a put option, and buying a call or a put option. Generally, options are used by investors to speculate the probable prices of the underlying asset.

Swaps are types of FI mostly used by business organizations to facilitate the altercation of one cash flow with another. The agreement is made between two parties to involve in the swapping of the interest rates (Dungore et al., 2022). For instance, an investor may opt to use an interest rate swap to switch from a fixed to a variable interest rate. The FI is essential to business organizations because it allows companies to effectively revise the conditions of the debts in order to benefit the expected or even current situations of the market.

Forward contracts are FI involving an agreement between two parties to undertake the exchange of the given asset at a specified price during the end of the arrangement. In most cases, the forwards are traded over the counter (OTC) (Dungore et al., 2022). In the process of the transaction, both the buyer and seller may agree to customize the size, terms, and even procedures of settlements once the contract has been created. Its OTC feature makes the forward derivate bear a significant counterparty risk that has the potential of affecting any of the involved participants. For example, one of the participants may fail to adhere to the obligation stated in the contract. In such a situation, the affected party will be forced to take the risks.

Foreign Exchange Instruments

Generally, foreign exchange instruments are usually derivatives. These are FI that are fully represented in the foreign markets. The FI is mainly the spot markets, swaps, option, future, and forward markets. This type of FI is designed to facilitate the management of financial risks that involves foreign exchange. The aspect makes the FI an essential tool that business organizations can use to reduce the hazards they are likely to encounter following the fluctuations in currencies in the money market.

The Asset Classes of FI

Apart from the various types of FI discussed above, FI can be further classified on the basis of assets. The two main categories are debt-based FI and equity-based FI. Each of the groups presents business organizations with essential opportunities for instance; the former presents business organizations with the ability to increase their capital base for smooth operations (Kańduła & Przybylska, 2021). They include mortgages, credit cards, debentures, bonds, and lines of credit. In most cases, the mentioned FI is short-term and last for about 12 months. On the other hand, long-term debt-based FI usually takes more than a year and they are mainly cash equivalents and exotic derivatives. The latter provides investors with the capacity of legal ownership of the company offering securities in the market. In this group, the FI includes preferred stock, common stock, transferrable subscription rights, and convertible debentures. Even though both classes enable corporations to raise the necessary capital, equity-based FI provides funds for the firms over a long period of time than debt-based FI.

Importance of the FI Concept

The concept is useful, especially to investors and business organizations which operate in the money market. The topic equips individuals with adequate knowledge about the various types of FI thus making it easier to choose the best option when engaging in any contractual obligation. With such understanding, a person may opt to advice companies concerning the nature of FI to enable them to gain effectively from their usage.

Furthermore, the topic increases the individual’s perspective of FI and how business organizations through the use of various types of FI can limit or avoid the potential risks in the market. The FI concept further makes it easier to speculate the future changes in market prices which is important for making an effective and informed decision for the business. Having a proper understanding of the FI idea, it will be easier to conduct a thorough research about the performance of securities in the financial industry.

In addition, the FI concept is essential in enabling accountants to classify various forms of derivatives and cash equivalents in financial statements. When the entries are made accordingly, it allows investors to have a clear picture of the respective organization based on its financial performance in relation to both equity and debt (Havemann et al., 2020). Furthermore, the FI idea allows investors to hedge their assets effectively hence they face limited financial risks.

Furthermore, the concept of FI is important because it gives people an opportunity to understand different ways of generating capital for business operations. Since there are various options in the market, with efficient knowledge it becomes easier to choose the best alternative to raise the necessary funds.

The concept of FI enables people to understand the importance of transferring risks to the other party. For instance, an investor may opt to buy instruments such as interest-rate swaps to give them the ability to protect their businesses against losses. Based on the FI idea, it becomes easier to remain effective in the market despite the challenges a firm may encounter. The FI topic is fundamental, especially in speculating sectors that are more likely to face frequent fluctuations leading to high risks in the market.

New Areas Learned in the FI Topic

In the process of exploring the FI concept, several new pieces of information I encountered. For instance, I learned about floating rate bonds which are essential financial securities that provide various interest influenced by the coupon rate that changes based on the market interest rates. In the US, the floating rate bond is preferred by most business organizations because of its feature that allows it to increase in value depending on the current status of the market. In other words, floaters make it possible for investors to continue receiving benefits following changes in the rates. Furthermore, the securities are less affected by market volatility hence they are effective and productive. However, despite the benefits associated with investing in a floating-rate bond, the FI experiences significant limitations. For example, in terms of rates, the security offers lower rates than their counterparts the fixed-rate bonds. The aspect makes them less attractive to business organizations that are attracted to higher rates.

Relationship between the FI and Financial Reporting and Analysis

Generally, the aspect of financial reporting and analysis encompasses the recording of the monetary details in the books of account. The practice is aimed at making a comprehensive financial statement that captures all the facets of a company’s financial information. Most sources of funds for the business organization include loans and equities which are major parts of the FI. The concept of FI makes it easier for accountants to effectively classify the various FI as financial assets, liabilities, or equities. The relationship between the reporting and FI makes it easier to analyze core aspects such as bank loans, amortized cost accounting, fair value, and balance sheets. After a proper examination of the FI, the analysts are then able to provide an accurate and reliable financial statement containing the necessary details that can be used by potential investors. Furthermore, the correlation ensures the reporting provides details of possible risks that are associated with different types of FI in the market.

To sum up, the concept of FI is essential, especially for business organizations that depend on the performance of the financial market. The FI are classified into three broad categories namely; cash instruments, foreign exchange instruments, and derivatives. The various types of FI play a vital role in enabling companies to have access to adequate sources of capital. In addition, the equity-based FI allows investors to own a portion of companies that are publicly traded in the SEM. By using the FI, business organizations have the ability to reduce potential risks through hedging practices. Similarly, the companies enhance their chances of benefiting future operations following effective speculations accompanied by either sell or purchase of the underlying asset. Based on the financial details in the FI concept, it is important for people especially accountants to have adequate knowledge about the FI topic. The aspect will enable them to develop effective financial reports that capture the key types of FI and classify them accordingly.

Dungore, P. P., Singh, K., & Pai, R. (2022). An analytical study of equity derivatives traded on the NSE of India . Cogent Business & Management , 9 (1). Web.

Havemann, T., Negra, C., & Werneck, F. (2020). Blended finance for agriculture: Exploring the constraints and possibilities of combining financial instruments for sustainable transitions . Agriculture and Human Values , 37 (4), 1281-1292. Web.

Kańduła, S., & Przybylska, J. (2021). Financial instruments used by Polish municipalities in response to the first wave of COVID-19 . Public Organization Review , 21 (4), 665-686. Web.

Kang, B. J. (2019). Economic benefits of derivatives for long term investments-equity linked securities . Journal of Derivatives and Quantitative Studies . Web.

Parameswaran, S. K. (2022). Fundamentals of financial instruments: An introduction to stocks, bonds, foreign exchange, and derivatives . John Wiley & Sons.

Stolowy, H., & Ding, Y. (2017). Financial accounting and reporting: A global perspective , (5th ed.). London: South-Western Cengage Learning.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, May 10). Financial Instruments: The Main Types. https://ivypanda.com/essays/financial-instruments-the-main-types/

"Financial Instruments: The Main Types." IvyPanda , 10 May 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/financial-instruments-the-main-types/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Financial Instruments: The Main Types'. 10 May.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Financial Instruments: The Main Types." May 10, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/financial-instruments-the-main-types/.

1. IvyPanda . "Financial Instruments: The Main Types." May 10, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/financial-instruments-the-main-types/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Financial Instruments: The Main Types." May 10, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/financial-instruments-the-main-types/.

- Summary of the Article “Should We Fear Derivatives?”

- Derivatives and Derivatives Market

- Derivatives: A Contract Between a Buyer and a Seller

- Horizontal and Vertical Financial Analysis

- Navigating Turkish Market Expansion: Currency, Management, and Entry Strategies

- Impact of Debts on Returns: Discussion

- Burberry Group's Financial Reporting in 2021

- Financial Reporting for Non-Profit Organizations

Green finance, sustainability disclosure and economic implications

Fulbright Review of Economics and Policy

ISSN : 2635-0173

Article publication date: 19 April 2023

Issue publication date: 6 June 2023

In this study, the authors provide a systematic literature review of articles in the emerging areas of green finance and discuss the status and challenges in sustainability disclosure, which is crucial for the efficiency of green financial instruments. The authors then review the literature on the economic implications of green finance and outline future research directions.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors use the analytical framework – Search, Appraisal, Synthesis, and Analysis (SALSA) to conduct the systematic review of the literature.

Increasing public attention to the environment motivates the use of green finance to fund environmentally sustainable projects, and the rise of green finance intensifies the demand for environmental disclosure. Literature has documented tremendous growth in sustainability reporting over time and around the globe, as well as raised concerns about how such reporting lack consistency, comparability, and assurance. Despite these challenges, the authors find that in general, the literature agrees that a firm’s green practice is positively associated with its financial performance and negatively related to a firm’s cost of capital. Green finance is also found to bring about enhanced risk management and economic development.

Originality/value

The authors provide one of the first reviews of green finance, sustainability disclosure and the impact of green finance on financial performance, capital market and economic development.

- Green finance

- Sustainability disclosure

- Sustainable investing

Liu, C. and Wu, S.S. (2023), "Green finance, sustainability disclosure and economic implications", Fulbright Review of Economics and Policy , Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1108/FREP-03-2022-0021

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023, Chen Liu and Serena Shuo Wu

Published in Fulbright Review of Economics and Policy . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/ legalcode

1. Introduction

As the world economy recovers from the impacts of COVID-19, the “green recovery” approach was proposed, making it a critical time to review existing research on green finance. In this paper, we follow G20’s definition and consider green finance as the financial instruments (such as green bonds), arrangements, mechanisms, and environmentally friendly operational practices, and the disclosure of these arrangements toward reducing carbon emissions and developing climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable infrastructure [1] , [2] .