An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The likelihood of having a household emergency plan: understanding factors in the US context

Jason d. rivera.

Department of Political Science and Public Administration, SUNY Buffalo State, Buffalo, NY 14222 USA

Individual household emergency planning is the most fundamental and can be the least expensive way to prepare for natural disasters. However, despite government and nonprofit educational campaigns, many Americans still do not have a household plan. Using a national sample of Americans, this research observes factors that influence people’s likelihood of developing a household emergency plan. Based on the analysis, people’s efficacy in preparedness activities, previous exposure to disasters and preparedness information positively influence the likelihood that someone will have developed a household emergency plan. Alternatively, demographic variables such as being Hispanic/Latino, identifying as Asian, and being a renter decrease the likelihood that someone will have developed a plan in the American context. But, the reason for these negative relationships are unclear. Subsequent to the analysis, recommendations for future research are provided to better understand observed relationships.

Introduction

Throughout the world, household disaster preparedness is viewed as the first step to reducing vulnerability to natural events. Within the USA, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and the American Red Cross have historically attempted to encourage individuals to develop and maintain household emergency plans (Murphy et al. 2009 ). However, despite the historic and widespread effort, Kapucu ( 2008 ) maintains that most people do not actually prepare for disasters despite knowing that they should. Along these lines, Levac et al. ( 2012 ) argue that many people overestimate their capacity to deal with emergency situations, and predominately plan to rely on emergency relief services for assistance in the aftermath of an event. As a result, according to the Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction for the Red Cross (Falkiner 2003 ), there is a general lack of household preparedness within the USA and Canada.

Because of this lack of preparedness, various studies have attempted to observe factors that contribute to individuals’ preparedness behaviors. Although a variety of studies (Diekman et al. 2007 ; Burke et al. 2010 ; Levac et al. 2012 ; Silver and Mathews 2017 ) have sought to observe what effects individuals’ stocking of supplies, household mitigation techniques, and information seeking, fewer have specifically attempted to investigate what effects the most basic form of disaster preparedness—the development of a household emergency plan. Household plans have been encouraged by a wide range of public, nonprofit and faith-based organizations because they require little to no upfront monetary investment due to their emphasis on household discussions and theorizing of hypothetical situations as opposed to investing in physical mitigation strategies. As such, this allows people from all socioeconomic levels to engage in this preparedness activity. However, despite the research that is available on what factors influence individuals to engage in this activity, people’s perceived efficacy surrounding this encouraged action has not been investigated at a national level (Lindell and Prater 2002 ; Murphy et al. 2009 ; Lindell et al. 2009 ; Bourque 2013 ).

Due to the increasing frequency and severity of a variety of natural disaster occurrences in the USA and throughout the world (i.e., hurricanes, flooding, wildfire, etc.) that interact with human systems (Burton et al. 1978 ; Oliver 1980 ; Peek and Mileti 2002 ), this study seeks to observe how people’s efficacy surrounding the development of a household emergency plan influences their decision to develop and discuss one with family members. Through the analysis of the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMAs) 2018 National Household Survey, I observe that people’s efficacy has a significant effect on people having had developed a household emergency plan. Additionally, other factors that have been observed in the literature to effect such a decision are tested to observe their respective influences on this most fundamental preparedness behavior (Burke et al. 2010 ; Levac et al. 2012 ; Silver and Mathews Silver and Matthews 2017 ). Based on the results of this study, recommendations are provided as a means of enhancing people’s proclivity to engage in the development of household emergency plans, in addition to potential avenues for future research.

Factors effecting household emergency planning

According to Bourque ( 2013 ; see also Lindell 2013 ), there are a number of household characteristics that have been investigated as a means of understanding what influences individuals to prepare for disasters. One of these factors is self-efficacy. Bandura ( 1977 ) maintains that self-efficacy refers to one’s perception of how competent they are in organizing and completing actions needed to manage risks. Along these lines, individuals with a relatively high sense of self-efficacy in disaster preparedness believe that their actions specifically contribute to reducing their vulnerability and enhancing their recovery in the aftermath of a disaster. As such, several studies have observed that households are more likely to engage in emergency planning when they believe their actions will be helpful or beneficial to their survival (Lindell and Whitney 2000 ; Lindell and Prater 2002 ; Martin et al. 2007 , 2008 , 2009 ; Olympia et al. 2010 ). However, most of these studies have observed preparedness behaviors as a continuum of actions, that include household planning, structural mitigation techniques, information seeking, stockpiling of nonperishable goods, and developing an evacuation plan, but not specifically the sole action of developing a household emergency plan. Moreover, many of these studies have observed the effect of self-efficacy in relation to different types of disasters as opposed to populations in general. Although it is not argued that the development of a plan is where preparedness should end, it is the most fundamental and accessible way individuals can begin to prepare for future events. By understanding how the general population’s self-efficacy effects the development of household disaster plans, programs can be enhanced in ways that attempt to build people’s sense of capacity.

Another factor that has been observed to effect individual preparedness is exposure to hazards. A variety of studies (Bourque et al. 2012 ; Paul and Bhuiyan 2010 ; Perry and Lindell 2008 ; Pennings and Grossman 2008 ), across a host of different types of natural occurrences, have observed that when people have had past experiences with previous disasters, they are more inclined to engage in preparedness activities. For example, Peacock ( 2003 ), Heller et al. ( 2005 ), and Nguyen et al. ( 2006 ) have all observed that when households have been exposed to previous disasters, they are more likely to make structural investments in their homes to mitigate against future damages. Sattler et al. ( 2000 ) observed that when individual’s perceptions of their risk to disasters is heightened as a function of their exposure, households are more likely to stockpile supplies for future events. Moreover, Basolo et al. ( 2009 ) found that people’s fear of risk, which was partially a byproduct of their previous exposure to a disaster, was positively correlated with their development of a family emergency plan.

In addition to past experiences, exposure to information about preparedness practices has been observed to effect individuals’ actions. A number of studies (Perry and Lindell 2008 ; Paton et al. 2005 ; Schwab et al. 2017 ) have observed that people’s active information seeking has had a positive effect on households’ preparedness; however, there are a number of other studies (Wood et al. 2012 ; Bourque 2015 ; Houston et al. 2015 ) that have observed positive influences on individual preparedness activities as a byproduct of their receipt of passive information. Along these lines, information received by households through the print media, radio, television, and, more recently, through social media have been observed to increase household preparedness and mitigation practices such as the development of emergency plans (Wood et al. 2012 ; Bourque 2015 ; Houston et al. 2015 ). Although the clarity and accessibility of messaging are important so that preparedness information has the broadest possible benefit to populations, simple exposure to this information is argued to be influential throughout all phases of emergency preparedness (Paton and Johnson 2001 ; Chen et al. 2009 ).

Finally, individuals’ proclivity to engage in preparedness activities has also been studied as a function of their demographic characteristics. However, Lindell ( 2013 ) maintains that the findings relating to the influence of demographic characteristics on preparedness activities are mixed. Characteristics such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, number of dependents, educational level, and income level have been found to be significant in some studies, and not in others (Edwards 1993 ; Lindell and Whitney 2000 ; Nguyen et al. 2006 ; Eisenman et al. 2006 ; Spittal et al. 2008 ; Lee and Lemyre 2009 ; Tekeli-Yesil et al. 2010 ; O’Sullivan and Bourgoin 2010 ; Levac et al. 2012 ). Moreover, Mulilis et al. ( 2000 ) argue property owners typically engage in preparedness behaviors more than renters; however, even this characteristic is not always predictive (Lindell 2013 ).

As a result of these mixed observations, this study seeks to contribute to our scope of knowledge on what factors influence the likelihood of an individual developing a household emergency plan. Based on previous research that has theorized the influence of self-efficacy on other preparedness and mitigation activities, I hypothesize that a person’s level of self-efficacy in preparedness activities will positively affect the odds of them having developed a household emergency plan (H1). Additionally, since past studies have examined the effect of individuals’ exposure to disaster mitigation and planning information on their individual preparedness, I also hypothesize that having received information on disaster preparedness will have a positive influence on the odds of an individual having developed a household emergency plan (H2). Finally, because of the lack of consensus on the effect that demographics has on preparedness and mitigation, this study will seek to observe the influence of various demographic factors on having developed a household emergency plan.

In order to investigate the factors that influence people to develop individual household emergency plans, data from FEMA’s 2018 National Household Survey (NHS) (FEMA 2019 ) 1 was analyzed. This survey has been conducted annually since 2007 and seeks to measure people’s preparedness behaviors, attitudes and motivations in relation to a number of different disaster events. The 2018 NHS interviewed 5003 adult respondents through mobile and landline telephones in both English and Spanish, and oversampled individuals that experienced earthquakes, flooding, wildfire, urban events, hurricanes, winter storms, extreme heat, and tornados. Oversamples were based on hazard histories on individuals (FEMA 2019 ). However, not all respondents answered all of the questions needed for this current study. As a result, the final sample is composed of 4538 respondents who addressed all of the germane questions. Table 1 presents a demographic breakdown of the sample used in the study.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics ( n = 4538)

Sampling weights were calculated to adjust for sample design aspects, such as the unequal probability of selection, and for nonresponse bias arising from differential response rates across various geographic regions and demographic groups (Maddala 1977 ; Kennedy 2007 ). The resulting weighted sample data reflect the entire target population of US adults. Beyond commonly used demographic variables, Table 1 includes a couple of variables important to this project. First, 50.55 percent of the sample indicated that they have developed and discussed a household emergency plan. Second, 63.16 percent of the sample indicated that they believed that taking actions to prepare for a disaster would be “Quite a Bit” or “A Great Deal” helpful to get them through a disaster. Third, 49.96 percent of the sample indicated that they had been exposed to information that could enhance their preparedness for a disaster in the last 6 months.

The dependent variable under investigation in this study is whether or not a respondent had developed and discussed a household emergency plan. Survey participants were asked: “Has your household developed and discussed an emergency plan that includes instructions for household members about where to go and what to do in the event of a local disaster?” The close-ended responses were coded zero (No) and one (Yes). As such, the dichotomous variable measures whether an individual has a household emergency plan.

The main independent variable in this research is an individual’s personal efficacy related to their disaster preparedness actions. In other words, respondents were asked to indicate how helpful they perceive preparedness behaviors to be in the event a disaster effected their geographic area. In response to this close-ended question, initial responses were coded from one to seven, but recoded in the analysis from zero to six, where zero indicated that the respondent believed that developing a household emergency plan in addition to other preparedness techniques would be “Not at all” helpful and four indicating that they believed preparing would be “A great deal” helpful. Responses that were coded with a five indicated that the respondent did not know, and those that were coded with a six indicated that the respondent had refused to answer the question. Because the data used in this study is secondary, there is no way to decern between respondents that specifically refused to answer the question and those that simply did not answer. As a result, all individuals that either refused to answer or simply did not answer compose the same category—“Refused.” As Table 1 highlights that only 4.01 percent of the sample indicated that preparedness activities would be “Not at all” helpful versus 40.77 percent that indicated that these types of practices would be “A great deal” helpful.

Because past research has indicated that exposure to disasters and emergency preparedness information has an influence on whether individuals engage in preparedness and mitigation practices, a variable measuring whether a respondent had been previously exposed to this type of information was included in the analysis. The survey asked respondents: “In the past 6 months, have you read, seen or heard of any information about how to get better prepared for a disaster?” The responses to this question are coded dichotomously, with zero indicating that an individual had not been exposed to this type of information and one indicating that they had. As indicated in Table 1 , 49.96 percent of the sample indicated that they recalled being exposed to information on how to become better prepared for disasters.

Literature also indicates an individual’s experience with disasters in the past has an influence on their preparedness practices. As such, an individual’s disaster experience was measured and included as a control variable in this study. The survey instrument asked respondents, “Have you or your family every experienced the impacts of a disaster?” Responses to this question were coded from zero to three, with zero indicating no and one indicating yes. Individuals that indicated that they did not know were coded with two and those that refused to answer the question were coded with a three. Table 1 highlights that 51.12 percent of the sample indicated that neither they nor their families had ever experienced a disaster; whereas, 48.53 percent responded that they had.

Finally, various demographic variables were included in the analysis due to their argued importance in disaster preparedness practices in the literature. Along these lines, respondents’ educational level, gender, race, homeownership, age, number of dependents under the age of 18 living in the same household, whether or not they are Hispanic/Latino, whether English is the primary language spoken in the household, and income were measured. Although household income is commonly measured per year, the survey asked respondents to indicate their level of household income per month. As such, the income categories represented in Table 1 are reflective of this.

For this study, logistic regression was used to observe how the previously discussed factors were associated with the odds of a respondent having developed and discussed a household emergency plan. Logistic regression is a technique which allows a researcher to relate a dichotomous dependent variable to a set of independent variables that may be continuous, categorical, and discrete or a combination of these (Petersen 1985 ; Warner 2008 ; Tabachnick and Fidell 2007 ). According to Petersen ( 1985 ), logit models allow a researcher to predict the probabilities of belonging to one of the categories on the dependent variable, in addition to predicting changes in probabilities resulting from changes in independent variables. This technique is therefore appropriate for this research in the context of assessing whether respondents developed a household emergency plan or not as a result of other independent variables since the dependent variable under investigation is dichotomous.

In order to observe how various factors influence individuals to develop and discuss a household emergency plan, the following equation was used:

In this equation, i indexes individual respondents, houseplan i represents if a respondent indicated that they had developed and discussed a household emergency plan (1) or 0 if not, x i is a vector of all the factors discussed previously that are represented in Table 1 , β are the coefficients to be estimated, and Λ is the cumulative logistic probability function. Standard assumptions for logistic regression were evaluated by preforming Spearman correlations, approximate likelihood ratio tests, and Brant tests (Brant 1990 ) on the regression model. The results of these tests demonstrated that the proportional odds assumptions held for each of the independent variables in the model. Moreover, the sample being analyzed in this study exceeds the ideal minimum number of observations for logistic regression (Petersen 1985 ).

Table 2 highlights the results of the logistic regression. Based on the analysis, several variables were observed to have statistically significant and positive influences on the odds of an individual having developed and discussed a household emergency plan. First, various levels of an individual’s personal efficacy in preparedness practices were found to be statistically significant and positively related to the odds of an individual developing and discussing a household emergency plan while holding all other variables constant. Specifically, as an individual’s level of efficacy increased the positive effect on the odds of them having developed and discussed a household plan also increased. Second, a statistically significant and positive relationship was observed between someone indicating they had been exposed to disaster preparedness information in the last six months and the odds of them having a household emergency plan in comparison to those that had not received similar information. Third, in comparison to individuals that indicated they nor their family had ever experienced a disaster, having experienced a disaster increased the odds of an individual having developed and discussed a household disaster plan while holding all other variables constant.

Table 2

Logistic regression of households with an emergency plan

In addition to these variables that had positive effects on the odds of someone having and discussing a household emergency plan, several variables were observed to have statistically significant and negative relationships with the dependent variable. First, Hispanic/Latino respondents were observed to have a statistically significant and negative relationship with the odds of having developed and discussed a household emergency plan in comparison to those that indicated they were not Hispanic/Latino and while holding all other variables constant. Second, being Asian also had a statistically significant and negative effect on the odds of having a household plan in comparison to Whites while holding all other variables constant. Third, renting one’s home had a statistically significant and negative effect on the odds of a respondent having developed and discussed a household emergency plan.

This study sought to investigate the influence of factors that have been observed to affect general household disaster preparedness on the specific action of developing a household emergency plan within the US context. Through the analysis of a national representative sample of Americans, various factors were observed to have an effect on the odds of someone developing a household emergency plan. Along these lines, two hypotheses were tested through the use of a logistic regression model. In line with past research on preparedness, an individuals’ efficacy in relation to developing a disaster plan was hypothesized and observed to be positively related to the odds of them developing an emergency plan. Moreover, as one’s relative level of efficacy increased, so too did the odds of them having developed a household plan. Additionally, it was also hypothesized and observed that having been passively exposed to disaster preparedness information, in addition to having previously experienced a disaster also positively influenced the odds of someone having developed a household emergency plan. As a result, this current research supports the observations of previous studies that have examined the influence of self-efficacy and passive information exposure on preparedness activities and broadens these variables’ potential influence on the development of individual household emergency plans.

These results also seem to indicate that outreach initiatives focused on educating the public about preparedness practices are somewhat effective. However, what is less understood is why some people have higher levels of self-efficacy when it comes to household preparedness activities than others. Is it that exposure to information over time contributes to someone’s sense of capacity to effectively deal with future disasters, and if so, is the way in which the information is presented more or less important in bestowing psychological support to people’s likelihood of engaging in these types of preparedness actions? Along these lines, future research should seek to address the influence preparedness information has on people’s efficacy based on the mediums through which the information is presented in the USA. Or, is a person’s efficacy a byproduct of their past experiences in disaster recovery? If this is the case, research should seek to qualify an individual’s previous preparedness behaviors, and their perceived effectiveness on an individual’s ability to recover from a past event as a means of observing whether the success or failure of past practices has affected their self-efficacy separately from their exposure to preparedness information.

In addition to understanding how efficacy influences people’s odds of developing a household emergency plan in the US context, this research also observed the effect of demographic variables on this practice. As was previously pointed out, many of the demographic variables that were controlled for in this study were not found to have statistically significant influences; however, there were a few that did. First, being Hispanic/Latino had a negative effect on the odds of an individual having developed a household emergency plan. The reason for this is unclear. Is it that Hispanics/Latinos are exposed to lower levels of passive information about disaster preparedness than their ethnic counterparts? Or, do Hispanics/Latinos tend to have relatively lower levels of self-efficacy than individuals belonging to other racial/ethnic categories? Future research might investigate this dynamic to understand why Hispanic/Latinos in the US context have a decreased odds of developing a household emergency plan in comparison to individuals that are not.

A similar relationship was also observed in reference to Asians. The analysis showed that being Asian decreased the odds of an individual developing a household emergency plan in comparison to their White counterparts. The reason for this relationship may have some similarity to that of Hispanics/Latinos; however, the effect that information exposure may have on this relationship maybe more prominent for Asians. The reason for this hypothesis is potentially related to the availability of documents and other preparedness information materials in languages that are accessible to Asian populations throughout the USA. Unlike Hispanics/Latinos that might require materials translated into Spanish or possibly Portuguese, Asians living within the USA speak a wide range of different languages, which many disaster mitigation and preparedness organizations do not have the capacity to translate. But the true reason for this relationship is unknown. Again, future research should attempt to understand why Asians in the USA are less likely than their White counterparts to develop household emergency plans.

Finally, renters were observed to have a decreased likelihood of developing a household emergency plan in comparison to their homeowning counterparts. As a result, this research seems to support Mulilis et al.’s ( 2000 ) findings that property owners are more inclined to engage in preparedness activities than renters; however, the reason for this is unclear and beyond the scope of this study. Future research may attempt to investigate through qualitative designs why renters are less likely to engage in household disaster planning. Additionally, future research may seek to observe the likelihood of renters developing household plans using a representative sample entirely composed of renters as a mean of understanding what characteristics among this particular group may affect preparedness at the household level.

Limitations and conclusion

Although this study observed various factors that potentially influence an individual’s odds of developing a household emergency plan, there are a few limitations that should be pointed out. First, this study did not account for the influence that an individual’s geographic location may have on their odds of developing a household plan. It may be that place (Cutter 1996 ; Wisner et al. 2004 ), which affects an individuals’ vulnerability to natural hazards, has a significant influence on household emergency planning. Second, and related to this first point, this study lacks clarity on the potentially differing affects that exposure to different types of disasters may have on household emergency planning. For example, does someone’s previous exposure to hurricanes have a stronger or weaker influence on the odds of them developing a household plan than if they had been exposed to an earthquake or their lived experiences throughout the COVID-19 pandemic? By better understanding these dynamics beyond what was observed in this current study, emergency management planning agencies can enhance their messaging and educational campaigns to more geographically situated populations and also potentially develop people's self-efficacy in preparedness activities.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to our knowledge of individual household emergency planning. Generally, speaking the development of a household emergency plan is the first step in enhancing people’s resilience to disasters. However, if people do not feel that their actions will result in beneficial outcomes, they will be less inclined to engage in this fundamental preparedness activity. Along these lines, having access to preparedness information is important. But, it is equally important that people feel that if this information is internalized and transferred into action, there will be direct benefits to them. When we enhance people’s efficacy in preparedness not only do we make individual households more prepared to deal with natural occurrences, but we also begin to more broadly influence the resilience of whole communities.

1 FEMA and the Federal Government cannot vouch for the data or analyses derived from these data after the data have been retrieved from the Agency's website.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977; 84 (2):191–215. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Basolo V, Steinberg LJ, Burby RJ, Levine J, Cruz AM, Huang C. The effects of confidence in government and information on perceived and actual preparedness for disasters. Environ Behav. 2009; 41 (3):338–364. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bourque L. Household preparedness and mitigation. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters. 2013; 31 (3):360–372. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bourque L. Demographic characteristics, sources of information, and preparedness for earthquakes in California. Earthq Spectra. 2015; 31 (4):1909–1930. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bourque L, Mileti DS, Kano M, Wood MM. Who prepares for terrorism? Environ Behav. 2012; 44 (3):374–409. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brant R. Assessing proportionality in the proportional odds model for ordinal logistic regression. Biometrics. 1990; 46 :1171–1178. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burke JA, Spence PR, Lachlan KA. Crisis preparation, media use, and information seeking during Hurricane Ike: lessons learned for emergency communication. J Emerg Manag. 2010; 8 (5):27–37. [ Google Scholar ]

- Burton I, Kates R, White G. The environment as hazard. New York: Oxford University Press; 1978. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen J, Wilkinson D, Richardson RB, Waruszynski F. Issues, considerations and recommendations on emergency preparedness for vulnerable population groups. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2009; 134 (3–4):132–135. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cutter SL. Vulnerability to environmental hazards. Prog Hum Geogr. 1996; 20 (4):529–539. [ Google Scholar ]

- Diekman ST, Kearney SP, O’neil ME, Mack KA. Qualitative study of homeowners’ emergency preparedness: experiences, perceptions, and practices. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2007; 22 (6):494–501. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Edwards ML. Social location and self-protective behavior: implications for earthquake preparedness. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters. 1993; 11 (3):293–304. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eisenman DPC, Wold J, Fielding A, Long C, Setodji S Hickey, Gelberg L. Differences in individual-level terrorism preparedness in Los Angeles County. Am J Prev Med. 2006; 30 (1):1–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Falkiner L (2003) Impact analysis of the Canadian red cross expect the unexpected program. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.617.9512&rep=rep1&type=pdf . Retrieved 2/25/20

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) (2019) 2018 National Household Survey Data Set. https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/182373 . Retrieved 1/2/2020

- Heller KDB, Alexander M, Gatz BG Knight, Rose T. Social and personal factors as predictors of earthquake preparation: the role of support provision, network discussion, negative affect, age, and education. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2005; 35 (2):399–422. [ Google Scholar ]

- Houston JB, Hawthorne J, Perreault MF, Park EH, Hode MG, Halliwell MR, Griffith SA. Social media and disasters: a functional framework for social media use in disaster planning, response and research. Disasters. 2015; 39 (1):1–22. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kapucu N. Culture of preparedness: household disaster preparedness. Disaster Prevent Manag. 2008; 17 (4):535–536. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kennedy C. Evaluating the effects of screening for telephone service in dual frame RDD surveys. Public Opin Q. 2007; 71 (5):750–771. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee JEC, Lemyre L. A social-cognitive perspective for terrorism risk perception and individual response in Canada. Risk Anal. 2009; 29 (9):1265–1280. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levac J, Total-Sullivan D, O’Sullivan TL. Household emergency preparedness: a literature review. J Community Health. 2012; 37 (3):725–733. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lindell MK. North American cities at risk: household responses to environmental hazards. In: Joffe H, Rossetto T, Adams J, editors. Cities at risk: living with perils in the 21st century. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 109–130. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lindell MK, Prater CS. ‘Risk area residents’ perceptions and adoption of seismic hazard adjustments. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002; 32 (11):2377–2392. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lindell MK, Whitney DJ. Correlates of household seismic hazard adjustment adoption. Risk Anal. 2000; 20 (1):13–25. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lindell MK, Arlikatti S, Prater CS. Why people do what they do to protect against earthquake risk: perceptions of hazard adjustment attributes. Risk Anal. 2009; 29 (8):1072–1088. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maddala GS. Econometrics. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1977. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martin IM, Bender H, Raish C. What motivates individuals to protect themselves from risks? the case of wildland fires. Risk Anal. 2007; 27 (4):887–900. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martin IM, Bender H, Raish C. Making the decision to mitigate. In: Martin WE, Raish C, Kent B, editors. Wildfire risk: human perceptions and management implications. Washington: Resources for the Future Press; 2008. pp. 117–141. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martin WE, Martin IM, Kent B. The role of risk perceptions in the risk mitigation process: the case of wildfire in high risk communities. J Environ Manag. 2009; 91 (2):489–498. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mulilis JP, Duval TS, Bovalino K. Tornado preparedness of students, nonstudent renters and nonstudent owners: issues of PrE theory. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000; 30 (6):1310–1329. [ Google Scholar ]

- Murphy ST, Cody M, Frank LB, Glik D, Ang A. Predictors of emergency preparedness and compliance. Disaster Med Public Health Preparedness. 2009; 3 (2):1–10. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nguyen LHH, Shen D, Ershoff AA Afifi, Bourque LB. Exploring the causal relationship between exposure to the 1994 Northridge Earthquake and pre- and post-earthquake preparedness activities. Earthq Spectra. 2006; 22 (3):569–587. [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Sullivan T, Bourgoin M (2010). Vulnerability to an influenza pandemic: looking beyond medical risk. Literature review prepared for the Public Health Agency of Canada. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tracey_Osullivan/publication/282817477_Vulnerability_in_an_Influenza_Pandemic_Looking_Beyond_Medical_Risk/links/561d4ae308aef097132b209c/Vulnerability-in-an-Influenza-Pandemic-Looking-Beyond-Medical-Risk.pdf . Retrieved 2/26/20

- Oliver J. The disaster potential. In: Oliver J, editor. Response to disaster. North Queensland: Center for Disaster Studies, James Cook University; 1980. pp. 3–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Olympia RP, Rivera R, Heverley S, Anyanwu U, Gregorits M. Natural disasters and mass-casualty events affecting children and families: a description of emergency preparedness and the role of the primary care physician. Clin Pediatr. 2010; 49 (7):686–698. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paton D, Johnson D. Disasters and communities: vulnerability, resilience and preparedness. Disaster Prev Manag. 2001; 10 (4):270–277. [ Google Scholar ]

- Paton D, Smith L, Johnson D. When good intentions turn bad: promoting natural hazard preparedness. Aust J Emerg Manag. 2005; 20 (1):25–30. [ Google Scholar ]

- Paul BK, Bhuiyan RH. Urban earthquake hazard: perceived seismic risk and preparedness in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Disasters. 2010; 34 (2):337–359. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peacock WG. Hurricane mitigation status and factors influencing mitigation status among Florida’s single-family homeowners. Natural Hazards Review. 2003; 4 (3):149–158. [ Google Scholar ]

- Peek LA, Mileti DS. The history and future of disaster research. In: Bechtel RB, Churchman A, editors. Handbook of environmental psychology. New York: Wiley; 2002. pp. 511–524. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pennings JME, Grossman DB. Responding to crises and disasters: the role of risk attitudes and risk perceptions. Disasters. 2008; 32 (3):434–448. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perry RW, Lindell MK. Volcanic risk perception and adjustment in a multi-hazard environment. J Volcanol Geoth Res. 2008; 172 (3–4):170–178. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petersen Trond. A comment on presenting results from logit and probit models. Am Sociol Rev. 1985; 50 (1):30–131. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sattler DN, Kaiser CF, Hittner JB. Disaster preparedness: relationships among prior experience, personal characteristics and distress. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000; 30 (7):1396–1420. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwab A, Sandler D, Brower DJ. Hazard mitigation and preparedness: an introductory text for emergency management and planning professionals. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Silver A, Matthews L. The use of Facebook for information seeking, decision support, and self-organization following a significant disaster. Inf Commun Soc. 2017; 20 (11):1680–1697. [ Google Scholar ]

- Spittal MJ, McClure J, Siegert RJ, Walkey FH. Predictors of two types of earthquake preparations: survival activities and mitigation activities. Environ Behav. 2008; 40 (6):798–817. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. New York: Pearson/Ally & Bacon; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tekeli-Yeşil S, Dedeoğlu N, Braun-Fahrlaender C, Tanner M. Factors motivating individuals to take precautionary action for an expected earthquake in Istanbul. Risk Anal: Int J. 2010; 30 (8):1181–1195. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Warner RM. Applied statistics: from bivariate through multivariate techniques. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wisner B, Blaikie P, Cannon T, Davis I. At risk: natural hazards, people’s vulnerability, and disasters. 2. New York: Routledge; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wood MM, Mileti DS, Kano M, Kelley MM, Regan R, Bourque LB. Communicating actionable risk for terrorism and other hazards. Risk Anal. 2012; 32 (4):601–615. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Need to SPEAK with an EXPERT? Call (888) 579-6849

The Importance of a Family Emergency Plan

By Dave Plunkett

","after_title":"

As the evening news and twitter feeds tell us, we’re all about to live on a planet with unbreathable air; undrinkable water (when you can Replace it); inedible food; and weather that makes guessing what to wear a real challenge on a daily basis. The bottom line, the world is changing and you’ve got to prepare your family for the worst.

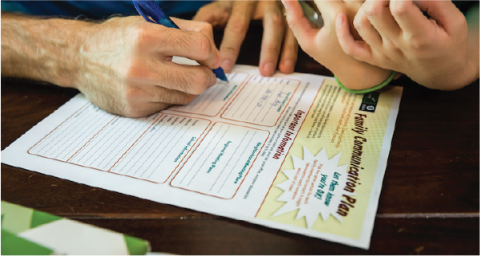

The road to proper preparation is paved with half-truths and political points of view. The main thing to remember is that you are preparing for immediate emergencies, so base your food storage plan on diversity and ease of preparation. But before you begin making an investment in survival food supplies and gear, you need to start with the creation of your family emergency plan. This plan will help you decide when an emergency situation (weather or natural disaster) forces you to decide whether to utilize a shelter in place solution or evacuate with your grab & go emergency kits.

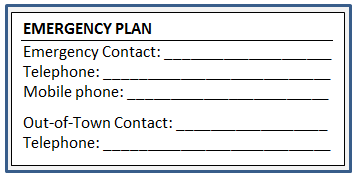

Your family emergency plan is just that – an emergency plan so that you know regardless of the disaster, you’ll be ready and prepared to do what you need to do to survive the situation. Your FEP should cover all the major topics that come into play when a natural disaster or major storm hits your area. Basically, you need to discuss and write down the following:

- The names, birthdates and social security numbers for each member of your family.

- Your chosen meeting places – you need to pick and then list three different locations: the place you’ll meet in your neighborhood; the place you’ll meet outside of your immediate neighborhood; and finally, a place to meet should you all be out of town when a disaster strikes.

- A list of where everyone spends their weekdays – schools, work and any other places one member of your family goes to during the day should be listed, along with its address and phone number.

- Insurance & other important documents. List everyone’s drivers license numbers, passport numbers and any insurance policy you are carrying. Having your policy information at the ready will make getting any insurance settlements much easier to accomplish.

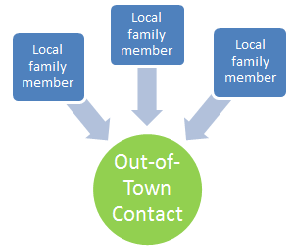

- Out of state contact(s) – you will need to decide on one or two people to use as your family’s check-in buddies. Every family member should use these numbers to call and inform them of your status should you family become separated during a storm or other disaster.

- Doctor or hospital contacts – be sure to list your family doctor’s name and number, along with the information about the nearest hospital. If applicable, include your Vet’s info as well.

To download your own Family Emergency Plan, go to FEMA’s website at: FEMA This site can not only provide the forms you need to fill out, but it also offers free of charge, a set of wallet cards your family can fill out to keep in their wallets and purses for quick reference.

Make sure to fill your family emergency food storage pantry by shopping our National Preparedness Month sale and save up to 58% on select essentials. We’re also offering FREE Shipping on all orders over $100, so get ready for winter by stocking up now.

Crystal Minnick

We’re pleased to hear that our articles are helpful. Thank you for the feedback!

It was very useful.

Your article was useful.

Thank you very much .

ahmad mehri

Your article was very good.

Thank you .

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published

- food storage

- gear and supplies

- getting started with prep

- in the news

- natural disaster preparedness

- preparedness skills

- preparedness stories

- staff picks

- water preparedness

Subscribe to our newsletter

Be the first to hear about deals, new products, emergency prep tips, and more.

100% free, unsubscribe any time.

Emergency Planning

Crafting a Family Emergency Plan: Essential Elements

January 18, 2024

The intelligent digital vault for families

Trustworthy protects and optimizes important family information so you can save time, money, and enjoy peace of mind

Try it free

Keeping you and your family safe should be a priority during times of crisis. Doing what's best for your loved ones involves being wise and making the best decisions, such as creating a family emergency plan.

However, developing one takes time. This guide covers all the essentials to create an effective energy family plan and provides tips and guidance to ensure you and your family are safe during times of uncertainty. Key Takeaways

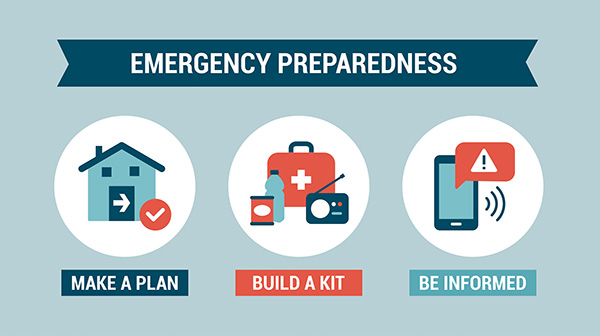

Having a family emergency plan helps ensure your family is protected. Whether it's a natural disaster or a public health crisis, an emergency plan will better prepare you.

A family emergency plan should be well thought out and include important information. Typically, it has a communication strategy and an evacuation plan establishing a defined meeting point.

There are always ways to improve your family emergency plan. Practices such as doing drills and staying informed can help you make small improvements to the plan.

The Importance of Crafting a Family Emergency Plan

A family emergency plan increases the chances of your family’s safety during an emergency event . The plan typically includes instructions on what to do to ensure safety.

Establishing a family emergency plan reduces the time it takes to respond appropriately to threats. However, it requires adequate planning and consideration of such events to make them effective.

For example, in a natural disaster such as a nearby wildfire, a good family plan should address “how to act, where to go, and how to communicate.” In this scenario, you could gather certain essential items, head to a safe location from the wildfire, and reach out to emergency contacts.

In most cases, not every family emergency plays out the same way. Having various plans can help your family be more flexible in responding to various emergency situations.

What Should a Family Emergency Plan Include?

Here are some important things to consider as you construct your emergency family plan.

Communication Plan

A well-thought-out communication plan involves establishing who to contact and how to do so during an emergency.

Create a list of emergency contacts for services or trustworthy people you know can help. Document the list and place it in an accessible location for easy access.

Within the emergency contact list, include the means of reaching out, which may be phone numbers, email, and location addresses, as well as any other means of contact, such as social media accounts.

Evacuation Plan

When developing an evacuation plan, identify the threat, and determine the best means of escape based on the event.

Making emergency plans for various scenarios, such as natural disasters, a break-in, or a national emergency, can help tailor the plan for the most efficient and safest evacuation method.

Map out the most effective evacuation routes and include details of alternative routes to take if one direction is not feasible. Include details on modes of transportation and note any items you should bring with you.

Have a Grab-and-Go Bag

Creating an accessible grab-and-go bag with essential items should be at the top of the list when developing any sort of evacuation plan. To determine what items are essential to include in your bag, consider the nature of the threat. If it's a situation where you won't have access to the house for a prolonged period, include a change of clothes. In addition, always include items you or your family can’t live without, such as essential medications. Incorporate basic necessities like food and water as well.

Remember to put the grab-and-go bag in a convenient location that’s quick and easy to reach during an emergency.

Take Essential Documents

Documents are one of the most common things people forget to take during an evacuation. Don’t make that mistake. Some documents, such as IDs, communication information, or irreplaceable legal papers, can lead to challenges later down the road when they aren’t in your possession.

Disaster Preparedness and Emergency Management Specialist at FEMA, Nick Miller , advises:

“You have to prioritize. What is the most important stuff to get out? I always say that is clothing, food, your emergency shelter supplies, and your important papers. I would have all your important papers and documents backed up.”

One recommendation is to make copies of any important documents that you have. Create both physical and digital versions so you will always have a backup. Of course, there might not be time to grab hard copies if evacuation from an emergency is urgent. Storing important documents online ensures their safety.

We have you covered if you want reliable online storage to protect your important documents. Trustworthy offers an online platform to store and organize all your essential documents for later access. In the event of an emergency, you can rest assured knowing everything is kept safe and organized whenever you need it.

Meetup Location

Knowing where to meet up during a family emergency is essential. Choose a spot before the crisis occurs.

When determining a meetup location for your family, you must consider certain factors. One is how accessible the location is for all of your family members. Ideally, find one centralized location that’s achievable for all members to reach.

The meetup location must also be accessible during the emergency itself. If the known threat could block off the location, have an alternative strategy for your family to reach safety.

Consider reevaluating family emergency plans from time to time to determine their effectiveness. Do an emergency drill to test and gauge if it's the right means of evacuation for you and your family.

Plan for Shelter-in-Place Scenarios

Sometimes, there are emergencies where it’s safer to shelter in place. Identifying these situations and planning accordingly helps ensure the best safety.

If the environment is too dangerous to leave your home, such as certain natural disasters or moments of political unrest, fortifying your location may be wiser than trying to abandon it.

Planning for sheltering in place requires you to stockpile essential resources, such as non-perishable foods, water, and medicines, to allow you to stay in place for a prolonged period. Being prepared for either sheltering in place or evacuating can help ensure your family's safety.

Stockpile Certain Supplies

During times of crisis, you don’t know when things will eventually settle. This is why you must stockpile certain items to ensure their safety and well-being for the long term.

With family emergency planning, stockpile supplies that will help protect your family from harm and keep them healthy when the emergency ends. Stockpiling is encouraged for shelter-in-place scenarios. However, you can also do it in advance for determined evacuation designations.

Only stockpile essential items. Here’s a list to take into consideration:

2-week supply of water (as recommended by FEMA )

2-week supply of non-perishable foods

First aid supplies

Personal hygiene items

Emergency lighting (flashlights, lamps)

Tools (knives, scissors, etc.)

Important documents (IDs, legal documentations, etc.)

Cooking appliances (pots, utensils, etc.)

Tips to Ensure Your Family Emergency Plan Is Foolproof

There is more to creating a family emergency plan than just planning. To help get the most out of it, follow these tips to ensure it’s effective when the time comes to follow through.

Practice the Emergency Plan

It’s a good idea to practice the plan through a series of drills and routines.

Some evacuation plans require you and your family to leave the area within minutes of the situation. In events where time is crucial, practicing drills is a good way of testing the efficiency of your strategy. If it takes too long to escape, you can adjust the pace as needed to address the time limit. Practicing and going through your established emergency plans at least once or twice a year helps keep you and your family sharp on emergency protocols.

Stay Informed

Staying informed on current events is a great way to be ahead of the curve when planning for potential disasters. You can plan ahead for some disasters by following reputable news sources. For example, news outlets notify people about natural disasters in advance, which can help you decide what's best for your family. The best way to stay informed is to subscribe to alert services on your phone. They tend to be the most reliable in informing whether the state of emergency is lifted and can often provide you with information on what to do and how to prepare.

Learn Prepper Basics

Being willing to learn basic prepper skills is greatly beneficial for you in being adept and providing safety for your family. Some skills such as first aid, effective communication, and food storage can help prepare you for almost any situation. Encouraging your family to learn with you is recommended, so they also learn the best practices.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How many steps are there for creating a family emergency plan?

While the number of steps may vary depending on the situation, here’s a common series of steps to take:

Step One: Determine likely risks

Step Two: Communicate with family

Step Three: Create a list of things you need and plans for emergencies

Step Four: Practice the emergency plans (evacuation and shelter-in-place) regularly

What are examples of family emergency meeting places?

Designated family meeting locations can be any safe and secure place. Some common locations include a room in a house, a nearby landmark, a community center, or another house or building within close access.

What is an example of a public emergency?

A public emergency is an event posing a significant threat to you and your family. These can be anything from natural disasters to public health crises, and industrial accidents to terrorist attacks or civil unrest.

Try Trustworthy today.

Try the Family Operating System® for yourself. You (and your family) will love it.

View pricing

Try Trustworthy Free

No credit card required.

Related Articles

Mar 27, 2024

Choosing the Best Household First Aid Kit

Jan 31, 2024

Schools' Emergency Guidelines: A Critical Overview

Jan 26, 2024

School Emergencies Exposed: The Alarming Reality

Jan 24, 2024

School Liability: Student Safety Beyond the Classroom

First Aid Skills Every Teacher Should Know

Jan 22, 2024

Emergency Note Essentials for Every Babysitter

Jan 19, 2024

Why Your Emergency Contact Matters: A Must-Read Guide

Jan 18, 2024

Minors As Emergency Contacts: Is It Legal?

Jan 11, 2024

Essential Emergency Medical Supplies: A Comprehensive List

Jan 10, 2024

Effective Communication in Emergency Situations

Jan 9, 2024

Daycare Emergency Plans: Preparing for the Unthinkable

Mar 6, 2023

The Top 5 Pieces of Information People Want Their Loved Ones to Have in an Emergency

Feb 1, 2023

How To Ask For Time Off For A Funeral (10 Templates)

Content Search

Creating a family emergency preparedness plan.

- Mercy Corps

Preparing for emergency situations can be overwhelming — but it’s also an important way to protect yourself and your family. When you know about the risks and hazards in your area, you can plan for them with awareness and forethought and have the appropriate supplies ready if and when they happen.

Recognized as a leader in delivering rapid, lifesaving aid to hard-hit communities, we have responded to numerous disasters, including the 2018 earthquake and tsunami in Indonesia, Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, the 2017 Horn of Africa drought and hunger crisis, and the 2015 Nepal earthquakes.

We know firsthand that emergencies can change everything in an instant.

In case of a serious emergency, emergency responders will be overwhelmed and unable to help for some time — possibly weeks. Your neighborhood may find itself stranded and isolated by fallen infrastructure. Those who aren’t prepared will face a harder time and could be a liability to neighbors.

This guide can help you prepare for many of the kinds of emergencies we respond to: power outages, violent storms, flooding, hurricanes, earthquakes, and more.

Building a communication and action plan

Stocking an emergency preparedness kit and emergency supplies Water Non-perishable food First aid Prescription medicine To-go emergency kit list Legal documents Pet safety Preparing your home for an emergency Have alternative sanitation Shut off utilities Secure furniture Insure your home How Mercy Corps responds to and prepares people for emergencies

Preparing for an emergency is about more than assembling supplies. One of the most important steps is making a plan with your family.

You’ll want to communicate with your loved ones so everyone knows what each person is going to do in the event of an emergency.

Everyone should know where your family will meet. Most people choose their home as their primary meeting place. You should also have a second place in mind as an alternate. It’s possible homes won’t be safe to enter. The area around your home may not be safe due to fire, poor air quality, or other hazards.

Consider the following. Where will you go immediately if the emergency:

Happens at home Happens while you are at work and the kids are at school Happens while you’re running errands Happens while you’re commuting

It’s also important to plan what you’ll do if members of your family are in different places when the earthquake hits:

Where will you meet each other? Who will be in charge of picking up your kids from school? Who is your emergency contact outside of your immediate location?

Make sure everyone in your family is aware of the plan, including where children should go and who will pick them up. Print copies and place them in your most frequented locations.

For the days after the disaster, you will also want to consider:

Where will you go if your home is no longer habitable? Where are your important documents and contact information? How will you evacuate, if needed?

Making a family plan and practicing it doesn’t have to be scary. You can make it a fun family event. This kind of practice is important because it gives your family the muscle-memory they need to be prepared in a variety of contexts. They might feel confident doing drills at school, but what about at home?

None of these preparedness actions cost money. The main cost is your time. This kind of planning is important not just for a big emergency, but also for more common emergencies, like home fires.

Back to top

Stocking an emergency preparedness kit and emergency supplies

Mercy Corps delivered relief kits in Kavresthali, Nepal. The kits included a tarp, sleeping mat, blanket, water purification drops, soap and other basic items. PHOTO: Miguel Samper for Mercy Corps

Emergency supplies are an essential part of a preparedness plan. You can assess your supply needs by thinking about where you spend extended periods of time. If you work outside the home, you might wish to have a home kit, a work kit, and even a commuting kit.

We recommend keeping your at-home emergency supplies together in a durable container with a lid. Organize your supplies in a safe and protected, easily-accessible area. Your kit should contain items to help you provide for your family for two weeks. Don’t “poach” supplies for other purposes, but do review them every six months, including expiration dates, to ensure safety.

You can keep an office go-bag under your desk at work. It should be something you can carry with you, containing items to help you survive, whether you’re trying to get home or staying where you are. Many people also keep a commuter kit in their cars, or in a bag they carry on transit or on their bikes.

As you assemble your emergency supplies, consider what items you may already have, such as camping gear, your kitchen pantry, or first aid supplies in your medicine cabinet. Just make sure you know where the necessary items are, and ask yourself, “Where are the gaps?”

Essential preparedness supplies are water, non-perishable food, and first aid. The following are considerations for the contents of your emergency kits.

Water Non-perishable food First aid Prescription medicine To-go emergency kit list Legal documents Pet safety Water

Water is the most essential element to survival, and a necessary item in every emergency kit. Following a disaster, clean drinking water may not be available. Your regular water source could be cut off or compromised through contamination.

In your home, plan to store at least one gallon of water per person per day for about 14 days. One gallon should cover drinking and sanitation. Children, nursing mothers and sick people may need more. A medical emergency might require even more.

You can purchase commercially bottled water for the safest and most reliable emergency water supply. Store your water in a cool, dark place. Keep bottled water in its original containers and do not open until you need to use it. Observe expiration dates. Replace your water supply about once every six months.

For to-go kits, consider using light-weight water packets or a water purifier to supplement small water bottles.

Non-perishable food

A Mercy Corps team member distributing cooked food. Following Hurricane Maria, Mercy Corps is supporting relief and recovery efforts in Puerto Rico. PHOTO: Ernesto Robles for Mercy Corps

Buy food you’d normally eat. Store enough to last two weeks per person. Stock up on canned foods, packets, dry mixes and other staples for your home. Emergency foods should not require refrigeration, cooking, water or special preparation.

Remember any special dietary needs. Avoid foods that make you thirsty. Choose salt-free crackers, whole grain cereals and canned foods with high liquid content. Here are some other food ideas:

Ready-to-eat canned meats, fruits, vegetables Protein or fruit bars Dry cereal or granola Powdered milk Peanut butter Dried fruit and nuts Crackers Canned juices Food for infants and children Spices Don’t forget utensils, plates, cups and a can opener!

A note about cooking without power: alternative cooking sources may be used in an emergency, such as chafing dishes, fondue pots and camping stoves. Depending on the severity of the emergency, your gas grill might be available. Remember to follow safety procedures, and never barbecue indoors.

If you’re cooking canned food with an alternative cooking source, remember to remove the label, thoroughly wash the can and open it before heating.

Your first aid supplies should be capable of dealing with moderate injuries, if possible. You might want to have enough supplies to treat multiple people.

Ideally, your first aid supplies would include:

Dressings Bandages Burn gel Splints Antiseptic

Since disaster responders may not be available, you may need to be able to treat more than the common cuts, scraps and burns.

Prescription medicine

Talk with your doctor about how to make sure you have enough prescription medications for at least a month, if possible. Keep your prescriptions current. Your doctor may be willing to write you an extra prescription for a disaster kit. Also keep in mind prescription expiration dates.

At the very least, make sure any necessary medications are easy to locate and grab in case of a sudden evacuation.

To-go emergency kit list

Members of Mercy Corps and the Zakat Foundation distributed solar lights and water filters to residents of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. PHOTO: J. Jimenez-Tirado for Mercy Corps

Keep a to-go kit in a backpack or satchel near an exit. Your to-go kit may also be used if you are at home. These are some items you might want to include:

Additional water packets, bottled water, or water purifiers Non-perishable, easy-to-carry food, such as meat packets, protein and fruit bars A mess kit with utensils, plate, cup and a can-opener Necessary medications, vitamins and first-aid supplies Prescription glasses and sunglasses Cash Pens & notebook Battery-powered or hand-crank radio Flashlight Batteries Solar phone-charger; car-battery phone charger Whistle or alarm to signal for help Lighter, or matches in a waterproof container Feminine supplies Personal hygiene, including toothbrush, toothpaste Toilet-in-a-Bag Moist towelettes. Dental floss – it has many uses! Clothing, including changes in underwear, hat, gloves Pet supplies and food Legal documents Tools: wrench, pliers Dust mask to help filter contaminated air Sleeping bag, blanket, bedding Complete change of clothes including long sleeved shirt, long pants, sturdy shoes Garbage bags A fun kit, including books, games, puzzles, cards, crayons, paper Legal documents

To help you think about what documents you may need access to, FEMA provides a checklist on its website, called the Emergency Financial First Aid Kit (EFFAK).

At a minimum, you should consider having photocopies of:

Identification, including birth certificates, social security card, citizenship papers Financial documents, including credit card and banking information Legal documents, including estate planning documents, property deeds, mortgage documentation, car titles Medical information, including health and life insurance policies, healthcare provider information Household contacts Pet safety Your pets will depend on you in case of a disaster, so think about them in advance.

The first step in a pet safety plan is to make sure your pets are properly identified. Does your pet have a license or ID tag? A microchip recommended by the ASPCA and can be read at most animal shelters.

Alternate care arrangements may be necessary for your pets. Arrange a safe haven: don’t leave your pets behind. Keep a list with several alternatives. Include phone numbers of alternate sites.

A designated caregiver is recommended in case an emergency occurs while pets are home alone. Perhaps you have a stay-at-home neighbor who is familiar and friendly with your pet. Do they have a key to access your home to provide care? You may wish to let them know what you’re thinking and provide orientation.

Include pet supplies in your family’s emergency kits, or make a specific kit for your pet. A good pet safety kit would be easy to carry, labeled, and easily accessible near a likely exit. Make sure everyone in your family knows where it is, including alternate caregivers.

What to include:

About one ounce of bottled water per pound per day Canned or dry food to last a week or more. Remember to rotate food and water periodically. Can opener Serving knife Bowls with lids Pet carrier Label with your pet’s name and your contact information Cage liner Pet first-aid kit and guidebook Medications in waterproof container Photocopies of medical records Photocopies of vaccination records Recent photos of your pets List of feeding habits, medical concerns, and behavioral issues Disposable dog scoop bags or disposable litter trays. You can use soil or sand in place of litter. Disinfectant Grooming supplies

Preparing your home for an emergency

Beyond having your supplies ready at home, it’s also important to consider other areas that might be affected by a disaster.

Have alternative sanitation Shut off utilities Secure furniture Insure your home Have alternative sanitation

During some emergencies, it’s unlikely that toilets will be operable. You can use the two-bucket method with camping toilet seats and sawdust for an alternate toilet, or purchase toilet-in-a-bag solutions to keep with your supplies.

Shut off utilities

Your utilities could be affected by some disaster situations. This is why you should know how to shut off your utilities — gas, water, and electricity. If you live in a house, make sure you and others in your household know how to do this.

Make sure you know where your home’s gas shut-off valve is. Keep a wrench by the gas valve so you will have it handy in an emergency.

If you’re in an apartment or condominium, make sure you know who would be in charge of this. It’s generally recommended that if you don’t smell gas, you don’t need to turn it off. But since we’ll have aftershocks and the situation may change, keep checking as long as it’s safe to do so. Apartment or condominium dwellers should manage gas systems for their own units only. DO NOT manipulate shared building systems.

Secure furniture

Secure tall or heavy furniture to walls to prevent it from falling during an earthquake. Falling furniture can cause injury or death, and can also block exit routes. Even without the threat of an earthquake, tall furniture should be secured for child safety. Tall appliances (refrigerators, washer/dryers) can also be secured to prevent movement during an earthquake. Furniture and appliances may be secured using furniture straps or other securing devices.

Insure your home

Only you can determine your risk tolerance and what kind of insurance coverage is right for you. Consult your insurance agent to determine what’s available to suit your needs.

How Mercy Corps responds to and prepares people for emergencies

Around the world, 160 million people per year are affected by some type of natural disaster.

In these emergency situations, people need immediate access to food, water and other basic necessities. Once recovery begins, they often need access to jobs or other activities and functional markets where they can buy and sell goods.

We help provide both.

Our responses start with meeting the most urgent needs. Lack of clean water and poor sanitary conditions are a major threat to people in emergencies. We often provide water, sanitation and hygiene support, which helps save lives and preserve health.

When possible, we choose cash-based assistance in emergency response in order to empower people to buy what they need most. We also help ensure access to adequate and safe food, since that is one of the most critical needs in an emergency.

As time passes, we focus on helping people build resilience to future emergencies. Often, that means helping build back markets where people can buy and sell goods. We also explore how we can get people back to work.

Related Content

World + 4 more

Introducting Anticipatory Action: A Feasibility Study for Malteser International

World + 16 more

Mrs. Reena Ghelani Assistant Secretary-General, Climate Crisis Coordinator for the El Niño / La Niña Response: Remarks to the Virtual Inter-ministerial Meeting of the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC)

Co-investment platform on climate information and early warning systems (ciews) established.

World + 11 more

Locusts: Towards sustainable management in Caucasus and Central Asia

Create a Family Emergency Plan Today

Having difficult conversations can make your kids feel safer..

Posted July 26, 2022 | Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

If there was an emergency, would you have a plan? What if there is a school shooting or a mass shooting at the local grocery store and you have no way to contact your children? The best way to protect your family is to have a safety plan.

Children feel better when they know they are emotionally and physically safe, but many families do not have a safety plan nor have they spoken directly about safety issues with their children. I hear a variety of excuses, like, “We are so busy,” “We just haven’t gotten around to it, though it’s on our to-do list,” or, “We have talked about what we would do if there was a flood or an earthquake.” The primary reason for putting off this discussion seems to be that parents are concerned that if they talk about scary things, they will frighten their kids.

Don’t be naive.

This generation of children has been exposed to a great deal of excessive content, often not appropriate for their age. This includes violent video games, overhearing parents listening to the news, images in the newspaper, or videos on social media sites. Consequently, many kids already live with a lot of fears, ranging from natural disasters to terrorist attacks, and of course, school shootings. Talking with them in a structured, forthright manner can only help. In fact, talking to them about a safety plan may be one of the most important discussions you have.

Putting Together Your Plan

Having a family safety plan begins with sitting down and holding a meeting. Come prepared with paper and pen to write down ideas. Set the goal that you will have a complete step-by-step guide for what each family member is to do in a variety of potential crisis situations. Also, specifically discuss what to do if an emergency happens during school hours, and go over school procedures in case of an emergency.

Here are some sample conversation starters:

- “We are going to talk about some things that may make you feel uncomfortable or even a bit scared. Hopefully, we will never have to use the information we are talking about, but we need to talk about it.”

- “You know how you have lockdown drills and fire drills at school? The principal and the teachers practice with you to make sure you are prepared in case of an emergency. We are going to do the same thing at home.”

- “What would you do if…?”

Create a list of questions for your kids to answer. Don’t make it scary; be matter-of-fact about knowing what to do based on the small possibility that something could happen.

Your family safety plan should be based on different scenarios, such as “What if mom and dad can’t get home from work before kids are home?” Ready.gov has created a complete set of instructions for parents to discuss with families, including elements of the plan below. Depending on the age of your children, decide which of the following components are appropriate:

- Set a general meeting place. Designate a general meeting place if one or more of you cannot make it home or to school.

- Create an emergency backpack. A great idea one mom shared with me was to have an “emergency backpack” ready in case of an unexpected event. In the backpack is a piece of paper with everyone’s contact information, insurance information, flashlight, protein bars, and assorted other things she thought her family may need.

- Set up an alert system. Set up a system that allows you to receive alerts and warnings from your local police on your phones. Go to your local police website or call them to find out how to set up receiving alerts on your electronic devices. FEMA has an Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS). Learn more from FEMA here, and sign up to receive alerts.

- Compile a list of all emergency phone numbers. These should include parents’ work and cell numbers, as well as the cellphone numbers of each child. Write all the numbers on a piece of paper or print out from your computer in case you can’t access electronic devices. Also write down the numbers of friends and neighbors in case of emergency. Put all of these important papers in a safe place and make sure all family members know where it is. Share with your kids who is on the list and why they are included, then add the list to everyone's phones and email it to a trusted friend or family member not living in your home.

- Talk about what to do if there is a shooting in a nearby school or similar emergency. Initiate this conversation with your child in a calm manner. Plan so you know what your mission is and how you can get there. Leave time for your child to ask questions. Be patient and stay silent letting your child absorb the information and think about how they are feeling.

- Have a social media plan. If cell service is down, plan to go to Facebook, Snapchat, or Instagram for information. Social media sites can be very effective in times of crisis.

- Learn about what type of natural disasters may affect your community. Discuss this with your children in a matter-of-fact way. Come up with several plans for how you would evacuate if need be. Become familiar with shelters in your area. If you have a pet, check to see if they accept pets . Keep your fuel tank full, especially if a storm is headed your way.

Remember: The goal is to create open communication with your children about “scary” and uncomfortable conversations. Conveying that you are available to talk about uncomfortable feelings and thoughts is critical for helping your child feel safe and protected.

Kislin, Nancy. Lockdown: Talking to Your Kids About School Violence, 2019.

Nancy J. Kislin, LCSW, MFT, is a therapist and educator who helps parents, educators, and communities cultivate resilience.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Based on Zip Code Change

- Shop the Red Cross Store

Disaster Preparedness Plan

- Share via Email

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

Make a Plan

DO NOT DELETE THE "EMPTY" SECTION CONTROL BELOW THIS. IT CONTAINS THE GHOST OF CLARA BARTON.

With your family or household members, discuss how to prepare and respond to the types of emergencies that are most likely to happen where you live, learn, work and play.

Identify responsibilities for each member of your household and how you will work together as a team.

Practice as many elements of your plan as possible.

Document Your Plan with Our Free Templates

Family Disaster Plan Template - English

Template Tips - English

Family Disaster Plan Template - Spanish

Template Tips - Spanish

Include Common Emergency Scenarios When You Plan