Journal Article: Abstract

When to write the abstract.

- Introduction

Writing an abstract can be difficult because you are tasked with condensing tons of work into such a small amount of space. To make things easier, write your abstract last. Read through your entire paper and distill each section down to its main points. Sometimes it can be helpful to answer this question through a subtractive process. For example, if you are trying to distill down your results, simply list all your findings and then go through that list and start crossing off or consolidating each finding until you are left with a only the most crucial results.

Your title and abstract are the primary medium through which interested readers will find your work amidst the deluge of scientific publications, posters, or conference talks. When a fellow scientist happens upon your abstract they will quickly skim it to determine if it is worth their time to dive into the main body of the paper. The main purpose of an abstract, therefore, is to contextualize and describe your work in a concise and easily-understood manner. This will ensure that your scientific work is found and read by your intended audience.

Abstract Formula

Clarity is achieved by providing information in a predictable order: successful abstracts therefore are composed of 6 ordered components which are referred to as the “abstract formula”.

General and Specific Background (~1 sentence each). Introduce the area of science that you will be speaking about and the state of knowledge in that area. Start broad in the general background, then narrow in on the relevant topic that will be pursued in the paper. I f you use jargon, be sure to very briefly define it.

Knowledge Gap (~1 sentence). Now that you’ve stated what is already known, state what is not known. W hat specific question is your work attempting to answer?

“Here we show…” (~1 sentence). State your general experimental approach and the answer to the question which you just posed in the “Knowledge Gap” section.

Experimental Approach & Results (~1-3 sentences). Provide a high-level description of your most important methods and results. How did you get to the conclusion that you stated in the “Here we show…” section?

Implications (~1 sentence). Describe how your findings influence our understanding of the relevant field and/or their implications for future studies.

This content was adapted from from an article originally created by the MIT Biological Engineering Communication Lab .

Resources and Annotated Examples

Annotated example 1.

Annotated abstract of a microbiology paper published in Nature . 4 MB

Annotated Example 2

Annotated abstract of a paper published in Nature . 2 MB

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

3 Marvelous MIT Essay Examples

What’s covered:, essay example #1 – simply for the pleasure of it, essay example #2 – community, essay example #3 – overcoming challenges.

- Where to Get Feedback on Your MIT Essay

Sophie Alina , an expert advisor on CollegeVine, provided commentary on this post. Advisors offer one-on-one guidance on everything from essays to test prep to financial aid. If you want help writing your essays or feedback on drafts, book a consultation with Sophie Alina or another skilled advisor.

MIT is a difficult school to be admitted into; a strong essay is key to a successful application. In this post, we will discuss a few essays that real students submitted to MIT, and outline the essays’ strengths and areas of improvement. (Names and identifying information have been changed, but all other details are preserved).

Read our MIT essay breakdown to get a comprehensive overview of this year’s supplemental prompts.

Please note: Looking at examples of real essays students have submitted to colleges can be very beneficial to get inspiration for your essays. You should never copy or plagiarize from these examples when writing your own essays. Colleges can tell when an essay isn’t genuine and will not view students favorably if they plagiarized.

Prompt: We know you lead a busy life, full of activities, many of which are required of you. Tell us about something you do simply for the pleasure of it.

After devouring Lewis Carrolls’ masterpiece, my world shifted off its axis. I transformed into Alice, and my favorite place, the playground, became Wonderland. I would gallivant around, marveling at flowers and pestering my parents with questions, murmuring, “Curiouser and curiouser.” If Alice’s “Drink Me” potion was made out of curiosity, I drank liters of it. Alice, along with fairytale retellings like the Land of Stories by Chris Colfer, kickstarted my lifelong love of reading.

Especially when I was younger, reading brought me solace when the surrounding world was filled with madness (and sadly, not like the fun kind in Alice in Wonderland ). There are so many nonsensical things that happen in the world, from shootings at a movie theater not thirty minutes from my home, to hate crimes targeted towards elderly Asians. Reading can be a magical escape from these problems, an opportunity to clear one’s mind from chaos.

As I got older, reading remained an escape, but also became a way to see the world and people from a new perspective. I can step into so many different people’s shoes, from a cyborg mechanic ( Cinder ), to a blind girl in WWII’s France (Marie-Laure, All the Light We Cannot See ). Sure, madness is often prevalent in these worlds too, but reading about how these characters deal with it helps me deal with our world’s madness, too.

Reading also transcends generational gaps, allowing me to connect to my younger siblings through periodic storytimes. Reading is timeless — something I’ll never tire of.

What This Essay Did Well

This essay is highly detailed and, while it plays off a common idea that reading is an escape, the writer brings in personal examples of why this is so, making the essay more their own. These personal examples often include strong language (e.g. “devoured,” “gallivant,” “pestering” ), which make the imagery more vivid, the writing more interesting. More advanced language can add more nuance to an essay– instead of “ate,” the writer chooses to say “devoured, ” and you can almost see the writer taking the book in almost as quickly as they might polish off a tray of cookies.

The writer also discusses how reading can not only be a solace from events that seem nonsensical, but a way to understand the madness in these events. By giving two different examples of how this can be so, that seem so varied from each other (the cyborg mechanic and the girl in WWII’s France), the writer creates more depth to this idea.

What Could be Improved

At the beginning, the writer should consider cutting the introduction paragraph by a line to leave more room for the two major points of the essay in the following paragraphs. Instead of a long sentence about a love of reading being kickstarted, the writer could create a short, powerful sentence to kick off the next two paragraphs. “I was in love with reading.”

The detail at the end about how reading also transcends generational gaps seems like an add-on that doesn’t connect to the past two ideas– instead, I would suggest that this author expand a little more on the prior two ideas and tie them together at the end. “In this timeless world of reading, I can keep drinking from the well of curiosity. In the pages of a book, I have a space to find out more about the world around me, process its events, and more deeply understand others.”

Prompt: At MIT, we bring people together to better the lives of others. MIT students work to improve their communities in different ways, from tackling the world’s biggest challenges to being a good friend. Describe one way in which you have contributed to your community, whether in your family, the classroom, your neighborhood, etc. (200-250 words)

“Orange throw!”

As I extended my arm to signal properly, the smallest girl on the orange team picked up the ball to throw it back into play. In AYSO, U10 players often lift their back foot when throwing the ball, so I focused my attention there.

Don’t lift it. Keep it down.

It shot straight up.

My instincts blew the whistle to stop the game. The rulebook is simple: the rule was broken, give it to the other team. But the way she tried, eager to play, eager to learn and try again— I couldn’t punish that. So I made my way over to the sideline to try it myself.

“When we’re throwing it in, we wanna keep our back foot down. Try again!” After demonstrating, I backpedaled a bit and watched her throw again.

Don’t lift it. Keep it down… Ah, it stayed down.

“Nice throw!”

And just like that, we were off again. These short, educational encounters happen multiple times a game. And while they may not be prescribed, they provide so many learning opportunities. These kids, they’re the future of soccer. If they learn the basics, they can achieve greatness.

Every time I step out onto the pitch, that’s what I see: potential. Little Alex may not throw correctly now, but with work, she could become the next Alex Morgan. That’s why, in every soccer game I referee, every new situation I’m thrust into, I strive to see what’s more; I strive to see the potential.

What the Essay Did Well

There is so much imagery in this essay! It’s easy to see the scene in your mind. Through details such as “smallest girl” and describing the team as the “orange,” the reader can more easily picture the scene in their mind. Giving color, size, and other details such as these can make the imagery stronger and the picture clearer in the reader’s mind.

The writer narrates their thought process through their use of italics, bringing the reader into the mind of the writer. The space for each line of dialogue separates each thought, so that the reader can feel the full emphasis of each line. The mingling of cognitive narration and details about the setting keep the momentum of the essay.

Through this essay, we learn that this referee is supportive to the members of the youth soccer teams that they are refereeing; instead of seeing the role of referee as punitive (punishing), this writer sees it as a coaching experience. This idea of creating educational encounters as one’s contribution to the community is definitely a great idea to build upon for this essay prompt.

What Could Be Improved

The contribution to the community is clear because of the emphasis on the coaching aspect of refereeing. However, especially thinking about structure, the author spends about half the essay on a single situation. Limiting this story to a third of the essay could give the writer more space to provide examples of other ways that the author has coached others. The author could have also connected this coaching experience to a mentoring experience in a different context, such as mentoring students at the YMCA, to create more connections between other extracurriculars and give more weight to this author’s contributions to the community.

The second to last paragraph ( “And just like that, we were off again…” ) could benefit from another example or two about showing, not telling. The sentence “And while they might not be prescribed, they provide so many learning opportunities” is already clear from the situation that the author has given; the author has already called these “educational encounters” in the prior sentence. Instead of that sentence, the writer could have given another example about a child thanking the writer for a coaching tip, or the expression on a different player’s face when they learned a new skill.

Additionally, the role of the writer is not immediately clear at the beginning, although it’s suspected that this student is most likely the referee. The writer also provides details about “AYSO” (American Youth Soccer Organization) and “U10,” where they could have simply referred to the games as “youth soccer games” to get the point across that the players are still learning basic skills about throwing the ball in.

To make all of this clear, the writer could have said “As a referee for youth soccer games, I have seen that players often lift their back foot when throwing the ball, so I focused my attention there.” Acronyms are usually best to be avoided in essays- they can take the reader’s attention away from what is actually happening and lead them to wonder about what the letters in the acronym stand for.

Prompt: Tell us about the most significant challenge you’ve faced or something important that didn’t go according to plan. How did you manage the situation?

“It’s… unique,” they say.

I sag, my younger sister’s koala drawing staring at me from the wall. It always seemed like her art ended up praised and framed, while mine ended up in the trash can when I wasn’t looking. In contrast to my sister, art always came as a bit of a struggle for me. My bowls were lopsided and my portraits looked like demons. Many times, I’ve wanted to scream and quit art once and for all. I craved my parents’ validation, a nod of approval or a frame on the wall.

Eventually, my art improved, and I made some of my favorite projects, from a ceramic haunted house to mushroom salt-and-pepper shakers. Even then, I didn’t get much praise from my parents, but I realized I genuinely loved art. It wasn’t something I enjoyed because of others’ praise; I just liked creating things of my own and the inexplicable thrill of chasing a challenge. Art has taught me to love failing miserably at something to continue it again the next day. If I never endured countless Bob Ross tutorials, I never would’ve made the mountain painting that I hang in my room today; if I never made pottery that blew up (just once!), I wouldn’t have my giant ceramic pie.

I’m still light years from being an expert, but I’ll never tire of the kick of a challenge.

The detail about the sister’s koala drawing being framed and praised while this writer’s portraits look like “demons” and bowls “lopsided” draws a nice contrast between the skills of the sister versus those of the writer. In response to this “Overcoming Challenges” prompt , the author justifies that this is a significant challenge by saying that they “wanted to scream and quit art once and for all” and that they still desired their parents’ approval.

The writer’s response to the situation— taking more tutorials online, creating many different pots before getting it right– is nicely framed. Many times, students forget to include examples that demonstrate how they respond to the situation, and this writer does a good job of including some of those details.

The writer seems to emphasize the parents’ approval piece in the first paragraph, but then moves away from that point more to focus on the “thrill of chasing a challenge.” This essay could be improved by focusing a little more on how the writer emotionally moved past not getting that approval “Even then, I didn’t get much praise from my parents, but I finally realized I didn’t need to focus on that. I could focus on my love of art, on the inexplicable thrill of chasing the challenge…”

Additionally, the sentence that starts with “Eventually, my art improved…” leaves the reader with the ques tion– how? Saying something like “Eventually, after many YouTube tutorials and a few destroyed pots, my art improved” would add detail, without taking away from the sentence about the Bob Ross tutorials and the pot blowing up.

Where to Get Feedback on Your MIT Essay

Do you want feedback on your MIT essays? After rereading your essays countless times, it can be difficult to evaluate your writing objectively. That’s why we created our free Peer Essay Review tool , where you can get a free review of your essay from another student. You can also improve your own writing skills by reviewing other students’ essays.

If you want a college admissions expert to review your essay, advisors on CollegeVine have helped students refine their writing and submit successful applications to top schools. Find the right advisor for you to improve your chances of getting into your dream school!

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Are you seeking one-on-one college counseling and/or essay support? Limited spots are now available. Click here to learn more.

MIT Supplemental Essays 2023-24 – Prompts and Tips

September 8, 2023

When applying to MIT, a school with a 4% acceptance rate where a 1500 SAT would place you below the average enrolled student (seriously), teens should be aware that it takes a lot to separate yourself from the other 26,000+ applicants you are competing against. While trying to be among the 1 in 25 who will ultimately be accepted sounds like (and is) a rather intimidating proposition, every year around 1,300 individuals accomplish this epic feat. We’ve worked with many of these students personally and can tell you one thing they all had in common—exceptionally strong MIT supplemental essays.

(Want to learn more about How to Get Into MIT? Visit our blog entitled: How to Get Into MIT: Admissions Data and Strategies for all of the most recent admissions data as well as tips for gaining acceptance.)

There are few schools that offer as many essays as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All applicants are required to respond to five prompts as they work through the MIT application. Your mission is to write compelling, standout compositions that showcase your superior writing ability and reveal more about who you are as an individual. Below are the MIT supplemental essays for the 2023-24 admissions cycle along with tips about how to address each one.

MIT Supplemental Essays – Prompt #1:

We know you lead a busy life, full of activities, many of which are required of you. Tell us about something you do simply for the pleasure of it. (200-250 words)

There are many different ways that you can approach this prompt, but the first step is to take MIT at their word that they are sincerely interested in what you do “simply for the pleasure of it.” While this may be something that also happens to be high-minded and/or STEM-oriented in nature, there is no expectation that this will be the case.

In essence, you want to ask yourself, what brings you great pleasure and happiness? Universal experiences of joy like family, a beautiful sunset, smiling children, or your cat or dog curled on your lap are perfectly acceptable answers here. However, you could also talk about dreams for the future, more bittersweet moments, abstract thoughts, moments of glorious introversion, or even something semi-embarrassing and vulnerable. The only “wrong” answer to this question would be an insincere one. As you enter the brainstorming phase, just make sure to turn off your “resume mode” setting. Instead, allow yourself to embrace the limitless possibilities of this essay.

Essay Prompt #2

What field of study appeals to you the most right now? Tell us more about why this field of study at MIT appeals to you. (Note: You’ll select your preferred field of study from a drop-down list.) (100 words or fewer)

Generally speaking, we all have a story of what drives us to pursue a certain academic pathway and career. How did your interest initially develop? What was the spark? How have you nurtured this passion and how has it evolved over time? If you desire to go into engineering, this is a chance to talk about everything from your childhood fascination with how things work to your participation in an award-winning robotics program at your high school. Share a compelling (and, of course, true!) narrative about how your love of your future area of study has blossomed to its present levels.

In other words, this essay should show evidence of intense hunger for knowledge that extends well outside of the classroom. How do you learn about your favorite subjects? What books have you read on the subject? Which podcasts have you listened to? What museums have you visited?

You can also tie your passions into specific academic opportunities at MIT including courses , professors , hands-on research programs , or any other aspects of your desired major that appeals most to you.

MIT Supplemental Essays – Prompt #3

MIT brings people with diverse backgrounds together to collaborate, from tackling the world’s biggest challenges to lending a helping hand. Describe one way you have collaborated with others to learn from them, with them, or contribute to your community together. (225 words)

How you interact with your present surroundings is the strongest indicator of what kind of community member you will be in your future collegiate home. This prompt asks you to discuss how you have collaborated with others (in any setting) in order to learn from them or contribute to a particular community. This could mean how you’ve collaborated with others during a group project, internship, extracurricular opportunity, sports event, or service project, to name a few.

Some words of warning: don’t get too grandiose in explaining the positive change that you brought about. Of course, if you and your team truly brought peace to a war-torn nation or influenced climate change policy on a global scale, share away. However, nothing this high-profile is expected. Essentially, MIT wants to understand how you’ve worked with other people—in any capacity—to expand your thinking or reach a common goal.

A few potential ideas for areas where you may have worked with/alongside others include:

- Racial injustice

- Assisting those with special needs

- Climate justice/the environment

- Making outsiders in a group feel welcome

- The economically disadvantaged

- Mental health awareness

- Clean-up projects

- Tutoring peers or younger students

- Charitable work through a religious organization

This is, of course, by no means a comprehensive list of potential topics. Most importantly, your story should be personal, sincere, and revealing of your core character and developing values system.

Essay Prompt #4

How has the world you come from—including your opportunities, experiences, and challenges—shaped your dreams and aspirations? (225 words or fewer)

This essay encourages you to describe how your world has shaped your aspirations. We all have any number of “worlds” to choose from, and MIT is inviting you to share more about one of these worlds through the lens of how that has shaped your dreams and aspirations.

Take note of the wide-open nature of this prompt. You are essentially invited to talk about any of the following topics:

- A perspective you hold

- An experience/challenge you had

- A community you belong to

- Your cultural background

- Your religious background

- Your family background

- Your sexual orientation or gender identity

Although this prompt’s open floor plan may feel daunting, a good tactic is to first consider what has already been communicated within on other areas of your application. What important aspect(s) of yourself have not been shared (or sufficiently discussed)? The admissions officer reading your essay is hoping to connect with you through your written words, so—within your essay’s reflection—be open, humble, thoughtful, inquisitive, emotionally honest, mature, and/or insightful about what you learned and how you grew.

You’ll then need to discuss how your chosen “world” has influenced your future, and in what ways.

MIT Supplemental Essays – Prompt #5

How did you manage a situation or challenge that you didn’t expect? What did you learn from it? (225 words)

Note this prompt’s new wording: How did you manage a situation or challenge that you didn’t expect ? Can you think of a time when you felt surprisingly overwhelmed? When something out-of-the-ordinary occurred? When you were caught off guard? Basically, MIT is trying to discover how you deal with unforeseen setbacks, and the important thing to keep in mind is that the challenge/story itself is less important than what it reveals about your character and personality.

Of course, some teens have faced more challenges than others, potentially related to an illness or medical emergency, frequent moving, socioeconomic situation, natural disaster, or learning disability, to name a few. However, you don’t have to have faced a significant challenge to write a compelling essay (and even if you have faced a significant challenge, you don’t have to write about it if you’re not comfortable doing so). Writing about a common topic like getting cut from a sports team, struggling in a particular advanced course, or facing an obstacle within a group project or extracurricular activity is perfectly fine. Any story told in an emotionally compelling, honest, and connective manner can resonate with an admissions reader. The bottom line here is that there are no trite topics, only trite answers.

Given the 225-word limit, your essay needs to be extremely tight and polished. In all likelihood, getting this one precisely right will involve a round or two of revision, ideally with some insight/feedback from a trusted adult or peer in the process.

Some tips to keep in mind include:

- Firstly, make sure you share what you were feeling and experiencing. This piece should demonstrate openness and vulnerability.

- Additionally, you don’t need to be a superhero in the story. You can just be an ordinary human trying their best to learn how to navigate a challenging world.

- Don’t feel boxed into one particular structure for this essay. The most common (which there is nothing wrong with), is 1) introducing the problem 2) explaining your internal and external decision-making in response to the problem 3) Revealing the resolution to the problem and what you learned along the way.

- Lastly, don’t be afraid that your “problem” might sound “trite” in comparison to those of others. This essay is about you. Y our job is to make sure that your response to the problem shows your maturity and resilience in an authentic way. That matters far more than the original challenge itself.

Essay Prompt #6 (Optional)

Please tell us more about your cultural background and identity in the space below. (150 words)

Unlike other optional essays, this one truly is optional. You don’t need to respond unless you have something significant to share about your cultural background and identity that hasn’t already been shared elsewhere on the application.

How important are the MIT supplemental essays?

There are 8 factors that MIT considers to be “very important” to their evaluation process. They are: rigor of secondary school record, class rank, GPA, standardized test scores, recommendations, extracurricular activities, and most relevant to this blog—the MIT supplemental essays.

Moreover, character/personal qualities are the only factor that is “very important” to the MIT admissions committee. Of course, part of how they assess your character and personal qualities is through what they read in your essays.

Want personalized assistance with your MIT supplemental essays?

In conclusion, if you are interested in working with one of College Transitions’ experienced and knowledgeable essay coaches as you craft your MIT supplemental essays, we encourage you to get a quote today.

- College Essay

Dave Bergman

Dave has over a decade of professional experience that includes work as a teacher, high school administrator, college professor, and independent educational consultant. He is a co-author of the books The Enlightened College Applicant (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016) and Colleges Worth Your Money (Rowman & Littlefield, 2020).

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Data Visualizations

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

I am a... Student Student Parent Counselor Educator Other First Name Last Name Email Address Zip Code Area of Interest Business Computer Science Engineering Fine/Performing Arts Humanities Mathematics STEM Pre-Med Psychology Social Studies/Sciences Submit

First-year applicants: Creative portfolios

Researchers, performing artists, visual artists, and makers may submit optional portfolios for review by MIT staff or faculty through SlideRoom . For more information on each type of portfolio, please review the descriptions below. Creative portfolios are truly optional, and should only be submitted if they feature work that is both significant to you and relevant to your MIT application.

Portfolios must be submitted by the same deadline as your corresponding application cycle—Early Action or Regular Action.

Students who have worked on a significant research project outside of high school classes are welcome to submit the Research Supplement via SlideRoom . If you have worked on more than one research project, focus on one project that is most significant to you.

- Please answer a brief questionnaire about your research experience.

- Include a PDF of your abstract or research poster, if available. If the work being submitted has been published, provide a citation.

- Nominate your research advisor, mentor, or Principal Investigator to submit a letter of recommendation directly through the SlideRoom portfolio.

Note: only one Research Supplement is permitted per applicant.

Music & Theater Arts

Students with exceptional musical, theater arts, or performing arts talent who would like their work to be reviewed by professional faculty from the MIT Music & Theater Arts department may submit a portfolio via SlideRoom .

- All Music & Theater Arts submissions: We require one letter of recommendation from a current or recent music or theater arts teacher, requested directly through the SlideRoom portfolio. We also ask that you upload a performing arts résumé.

- If you play two instruments equally well, you may optionally choose to submit a separate music portfolio for each instrument. Please create a second SlideRoom account using a different email address to submit a separate portfolio for your second instrument.

- The composition portfolio is currently designed for musicians who compose music using Western musical notation. If possible, we ask that submissions that feature music production or electronic beats provide some musical notation, scores, or arrangements.

- Actors, dancers, directors, and designers: Submit up to three videos or images. 10 minutes maximum total combined video time.

- This portfolio option is meant for screenwriters/playwrights only. While MIT values creative writing, we do not currently offer a portfolio to review creative writing, essays, poetry, etc.

Visual Art & Architecture

The Visual Art & Architecture portfolio is designed for students with exceptional creative talent who would like their work to be reviewed by professional faculty and staff at MIT. You should consider submitting work via SlideRoom if your work is a significant part of your application and demonstrates strong creative talent for a young artist.

- We encourage all types of media art, including design, drawing, painting, mixed media, digital media, photography, sculpture, and architectural work.

- You may submit a portfolio of up to 10 images of your work for review. Include the title, medium, a brief description, date completed, and a brief description of each work’s concept or inspiration.

Note: only one Visual Art & Architecture portfolio is permitted per applicant.

The Maker Portfolio is an opportunity for students to showcase their technical creativity—from carpentry to coding to cosplay. Your submission will be evaluated by the Engineering Advisory Board, a group of MIT faculty, staff, and alumni with notable technical expertise in different modes of making. If you make the kind of thing(s) you might exhibit at a Maker Faire, demo at a hackathon, or just do for yourself and friends, then the Maker Portfolio in SlideRoom is a way to show us.

- Please answer a brief questionnaire about what you make, how you make, and why you make. Provide clarity on relevant goals, issues, setbacks, and lessons learned. We want to know about your problem-solving process and motivations, not just your visible end result.

- Sometimes, less is more! If you’re particularly prolific, consider focusing on the details for a few of your favorite projects.

Note: only one Maker Portfolio is permitted per applicant.

Portfolio fee or waivers

The fee to submit each portfolio is $10. However, we understand that paying college application fees presents a hardship for some families. If the submission fee presents a hardship for you and your family, you may qualify for a fee waiver. To request a fee waiver, send a brief email to our SlideRoom portfolio team with the subject line “SlideRoom Fee Waiver” by the deadlines listed below. Include your full name and date of birth in the body of the email. Your SlideRoom portfolio must be in progress to receive a fee waiver; we cannot proactively grant fee waivers for portfolios that have not been started.

Fee Waiver Deadlines

Early Action: October 27 (Portfolios must be submitted by November 1)

Regular Action: December 28 (Portfolios must be submitted by January 4)

Allow 3–5 days for your request to be processed. You will receive an email once your fee has been waived; you must then submit your portfolio by the submission deadline.

Political Science: Articles and Theses

- Articles and Theses

- Data + Statistics

- Popular Journals

- Congressional News

- Security Studies News

- Books for Thesis Writers

- Search Tips

- Interlibrary Borrowing - Articles

Quick search

Search article title, author, or keywords. MIT Libraries full text holdings are linked in right column of Google Scholar results

-> To get the full text of articles not in our collection, request through Interlibrary Borrowing or Search our Collections

Journal Articles and Theses

Start your search

- Search our Collections Start with the MIT libraries' mega search. This contains the libraries full collection of books, full text articles, government. documents, and more. PRO TIP: For a more comprehensive search, click "expand beyond MIT collections" button at upper left of results to see many more articles which can be ordered via inter-library borrowing.

- Google Scholar Free scholarly article database. Link to MIT libraries for full text and Web of Science citing articles.

- Political Science Complete Citations, abstracts, and indexing of the international journal literature in political science and its complementary fields, including international relations, law, and public administration/policy. Reference books and conference papers are also available.

- EBSCO literature database search This searches a collection of EBSCO social science databases: Political Science Complete, Academic Search Complete, Econlit, Business Source Complete, Gender Studies, Education Source, Anthropology Plus, Environment Index, Urban Studies, LBGTQ+ Source, Agricola

Article databases and resources

- ABI/Inform Find articles from major business publications and trade journals about business conditions, management techniques, business trends, management practice and theory, corporate strategy and tactics, and competitive landscape worldwide.

- Advanced Technologies & Aerospace Collection Aeronautics, astronautics, and space sciences 1962 - present. Contains abstracts of Jane's Defense Weekly, 1996-present

- Aerospace Research Central (ARC) Full text of all technical papers & articles from the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics journals, and selected eBooks. 1963 - present .

- Agricultural and Environmental Science Database Journal & conference articles, reports, books & government publications with comprehensive coverage of environmental & pollution issues.

- America: History and Life US & Canadian history, prehistory-present. Indexes articles, book reviews, essay collections, dissertations, media.

- Annual Review of Political Science Annual edited volume that covers significant developments in the field of political science including political theory and philosophy, international relations, political economy, political behavior, American and comparative politics, public administration and policy, and methodology. Covers 1998-present.

- China Research Gateway Indexing and full text content of articles in scholarly Chinese-language journals in political science, military affairs, and law. 1994 to present

- Dspace@MIT MIT authored papers and theses

- Historical Abstracts Resource covering world history (excluding US and Canada), 1450 to present. Indexes and abstracts articles, books, essay collections, dissertations, and media.

- JSTOR Scholarly Archive A collection of scholarly journals in many fields. Includes deep historical coverage but current years are excluded.

- Military Balance The Military Balance is the International Institute for Strategic Studies annual assessment of the military capabilities and defence economics of 171 countries worldwide.

- Oxford Handbooks Online: Political Science Authoritative reviews of political science research. Introductions to topics and a critical survey of the current state of scholarship in political science. 2009 - present.

- Proquest Dissertations and Theses Indexing and abstracting of non-MIT dissertations and theses 1861 - present. Full text for most dissertations 1997-present and selective full-text for earlier dissertations. Comprehensive coverage of North American universities and selective coverage worldwide.

- SSRN (Social Science Research Network) SSRN is an open-access online preprint community. MIT Political Science working papers are deposited in SSRN

- Web of Science / Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) Top tier journal articles in science, social science, engineering, art & humanities research journals,

Articles you need not at MIT?

Use the Interlibrary Borrowing Service to order articles and other items not available at MIT.

Request scan

Request a pdf scanned copy of a book chapter or article the library owns in print.

MIT Political Science

News + Events

Working Papers + Research

Book a Study Room

- Go to mycard.mit.edu

- Select Room Group > MIT Libraries on the top right drop-down menu (if applicable).

- Click the Reserve button next to the room you want (Dewey is e53)

- Click the Confirm button to make the reservation.

- For more information: Reserve a study room

Related Guides

- Congressional Publications

- Country Data & Analysis

- Data Management

- GIS Services

- Government Information

- Security Studies

- Social Science Data Services

- Next: Databases >>

- Last Updated: Jan 30, 2024 5:18 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mit.edu/polisci

- Sponsorship

- The MITIR Approach

- How to Submit

- Advertising

- Originality : The paper must contain original and unpublished work.

- File Format : Papers should be submitted as Microsoft Word files (*.doc) or as Rich Text Format files (*.rtf).

- Length : Maximum words of possible submission categories: - Traditional Essays (4000) - Original Data-Centered Research (2000, free of all technical jargon) - Case Studies (2000) - Interviews (1500) (e.g., medical treatments) for the resolution of a global problem - Field Reports (1500): For those who can impart an outsider’s perspective on global problems and what is being done about them - Work-in-Progress (1200): For those who are pioneering new technologies or services - Opinion Editorials (800) - Photo Essays (maximum: 10 photographs).

- Contact Information : A separate page should list: - Name(s) of the author(s) - Address - Telephone (and fax number) - E-mail address - Institutional affiliation.

- Abstract : The first page of the actual article should contain the following information: - Title - Name(s) of the author(s) - An abstract of no more than 100 words - Word count of the article.

- Accuracy : Facts in submissions will be reviewed to ensure accuracy.

- References should be included.

- Figures should not be copyrighted.

Please submit your work to [email protected] .

Note : After initial submission, writers whose articles are being considered for publication may be asked to resubmit their articles according to more specific guidelines.

MIT Libraries home DSpace@MIT

- DSpace@MIT Home

- MIT Libraries

- Doctoral Theses

Essays on the economics of science and innovation

Other Contributors

Terms of use, description, date issued, collections.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write an Abstract (With Examples)

Sarah Oakley

Table of Contents

What is an abstract in a paper, how long should an abstract be, 5 steps for writing an abstract, examples of an abstract, how prowritingaid can help you write an abstract.

If you are writing a scientific research paper or a book proposal, you need to know how to write an abstract, which summarizes the contents of the paper or book.

When researchers are looking for peer-reviewed papers to use in their studies, the first place they will check is the abstract to see if it applies to their work. Therefore, your abstract is one of the most important parts of your entire paper.

In this article, we’ll explain what an abstract is, what it should include, and how to write one.

An abstract is a concise summary of the details within a report. Some abstracts give more details than others, but the main things you’ll be talking about are why you conducted the research, what you did, and what the results show.

When a reader is deciding whether to read your paper completely, they will first look at the abstract. You need to be concise in your abstract and give the reader the most important information so they can determine if they want to read the whole paper.

Remember that an abstract is the last thing you’ll want to write for the research paper because it directly references parts of the report. If you haven’t written the report, you won’t know what to include in your abstract.

If you are writing a paper for a journal or an assignment, the publication or academic institution might have specific formatting rules for how long your abstract should be. However, if they don’t, most abstracts are between 150 and 300 words long.

A short word count means your writing has to be precise and without filler words or phrases. Once you’ve written a first draft, you can always use an editing tool, such as ProWritingAid, to identify areas where you can reduce words and increase readability.

If your abstract is over the word limit, and you’ve edited it but still can’t figure out how to reduce it further, your abstract might include some things that aren’t needed. Here’s a list of three elements you can remove from your abstract:

Discussion : You don’t need to go into detail about the findings of your research because your reader will find your discussion within the paper.

Definition of terms : Your readers are interested the field you are writing about, so they are likely to understand the terms you are using. If not, they can always look them up. Your readers do not expect you to give a definition of terms in your abstract.

References and citations : You can mention there have been studies that support or have inspired your research, but you do not need to give details as the reader will find them in your bibliography.

Good writing = better grades

ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments.

If you’ve never written an abstract before, and you’re wondering how to write an abstract, we’ve got some steps for you to follow. It’s best to start with planning your abstract, so we’ve outlined the details you need to include in your plan before you write.

Remember to consider your audience when you’re planning and writing your abstract. They are likely to skim read your abstract, so you want to be sure your abstract delivers all the information they’re expecting to see at key points.

1. What Should an Abstract Include?

Abstracts have a lot of information to cover in a short number of words, so it’s important to know what to include. There are three elements that need to be present in your abstract:

Your context is the background for where your research sits within your field of study. You should briefly mention any previous scientific papers or experiments that have led to your hypothesis and how research develops in those studies.

Your hypothesis is your prediction of what your study will show. As you are writing your abstract after you have conducted your research, you should still include your hypothesis in your abstract because it shows the motivation for your paper.

Throughout your abstract, you also need to include keywords and phrases that will help researchers to find your article in the databases they’re searching. Make sure the keywords are specific to your field of study and the subject you’re reporting on, otherwise your article might not reach the relevant audience.

2. Can You Use First Person in an Abstract?

You might think that first person is too informal for a research paper, but it’s not. Historically, writers of academic reports avoided writing in first person to uphold the formality standards of the time. However, first person is more accepted in research papers in modern times.

If you’re still unsure whether to write in first person for your abstract, refer to any style guide rules imposed by the journal you’re writing for or your teachers if you are writing an assignment.

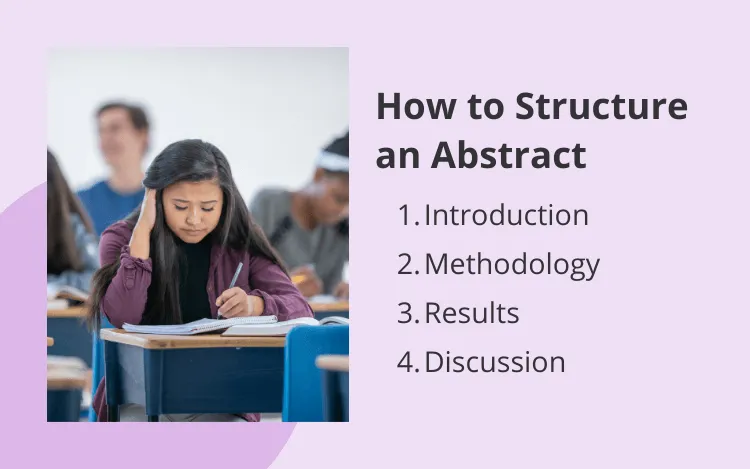

3. Abstract Structure

Some scientific journals have strict rules on how to structure an abstract, so it’s best to check those first. If you don’t have any style rules to follow, try using the IMRaD structure, which stands for Introduction, Methodology, Results, and Discussion.

Following the IMRaD structure, start with an introduction. The amount of background information you should include depends on your specific research area. Adding a broad overview gives you less room to include other details. Remember to include your hypothesis in this section.

The next part of your abstract should cover your methodology. Try to include the following details if they apply to your study:

What type of research was conducted?

How were the test subjects sampled?

What were the sample sizes?

What was done to each group?

How long was the experiment?

How was data recorded and interpreted?

Following the methodology, include a sentence or two about the results, which is where your reader will determine if your research supports or contradicts their own investigations.

The results are also where most people will want to find out what your outcomes were, even if they are just mildly interested in your research area. You should be specific about all the details but as concise as possible.

The last few sentences are your conclusion. It needs to explain how your findings affect the context and whether your hypothesis was correct. Include the primary take-home message, additional findings of importance, and perspective. Also explain whether there is scope for further research into the subject of your report.

Your conclusion should be honest and give the reader the ultimate message that your research shows. Readers trust the conclusion, so make sure you’re not fabricating the results of your research. Some readers won’t read your entire paper, but this section will tell them if it’s worth them referencing it in their own study.

4. How to Start an Abstract

The first line of your abstract should give your reader the context of your report by providing background information. You can use this sentence to imply the motivation for your research.

You don’t need to use a hook phrase or device in your first sentence to grab the reader’s attention. Your reader will look to establish relevance quickly, so readability and clarity are more important than trying to persuade the reader to read on.

5. How to Format an Abstract

Most abstracts use the same formatting rules, which help the reader identify the abstract so they know where to look for it.

Here’s a list of formatting guidelines for writing an abstract:

Stick to one paragraph

Use block formatting with no indentation at the beginning

Put your abstract straight after the title and acknowledgements pages

Use present or past tense, not future tense

There are two primary types of abstract you could write for your paper—descriptive and informative.

An informative abstract is the most common, and they follow the structure mentioned previously. They are longer than descriptive abstracts because they cover more details.

Descriptive abstracts differ from informative abstracts, as they don’t include as much discussion or detail. The word count for a descriptive abstract is between 50 and 150 words.

Here is an example of an informative abstract:

A growing trend exists for authors to employ a more informal writing style that uses “we” in academic writing to acknowledge one’s stance and engagement. However, few studies have compared the ways in which the first-person pronoun “we” is used in the abstracts and conclusions of empirical papers. To address this lacuna in the literature, this study conducted a systematic corpus analysis of the use of “we” in the abstracts and conclusions of 400 articles collected from eight leading electrical and electronic (EE) engineering journals. The abstracts and conclusions were extracted to form two subcorpora, and an integrated framework was applied to analyze and seek to explain how we-clusters and we-collocations were employed. Results revealed whether authors’ use of first-person pronouns partially depends on a journal policy. The trend of using “we” showed that a yearly increase occurred in the frequency of “we” in EE journal papers, as well as the existence of three “we-use” types in the article conclusions and abstracts: exclusive, inclusive, and ambiguous. Other possible “we-use” alternatives such as “I” and other personal pronouns were used very rarely—if at all—in either section. These findings also suggest that the present tense was used more in article abstracts, but the present perfect tense was the most preferred tense in article conclusions. Both research and pedagogical implications are proffered and critically discussed.

Wang, S., Tseng, W.-T., & Johanson, R. (2021). To We or Not to We: Corpus-Based Research on First-Person Pronoun Use in Abstracts and Conclusions. SAGE Open, 11(2).

Here is an example of a descriptive abstract:

From the 1850s to the present, considerable criminological attention has focused on the development of theoretically-significant systems for classifying crime. This article reviews and attempts to evaluate a number of these efforts, and we conclude that further work on this basic task is needed. The latter part of the article explicates a conceptual foundation for a crime pattern classification system, and offers a preliminary taxonomy of crime.

Farr, K. A., & Gibbons, D. C. (1990). Observations on the Development of Crime Categories. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 34(3), 223–237.

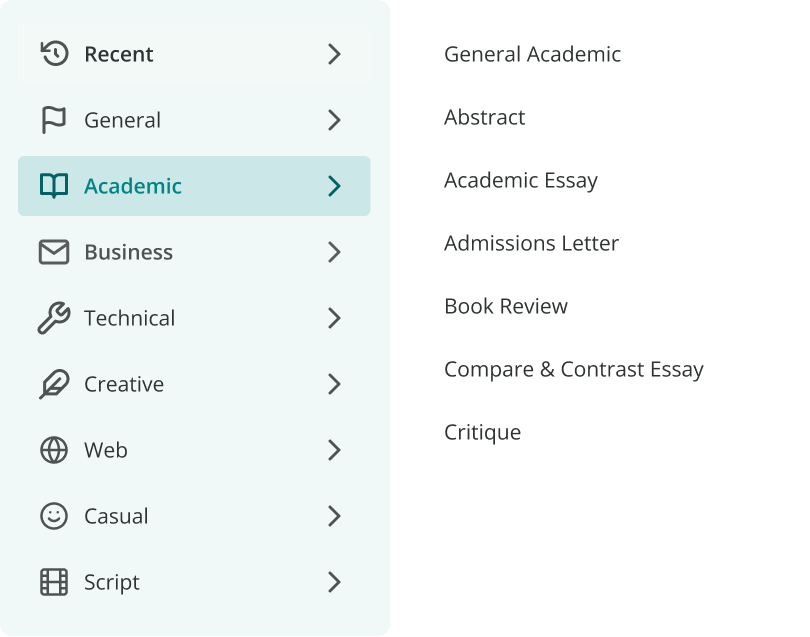

If you want to ensure your abstract is grammatically correct and easy to read, you can use ProWritingAid to edit it. The software integrates with Microsoft Word, Google Docs, and most web browsers, so you can make the most of it wherever you’re writing your paper.

Before you edit with ProWritingAid, make sure the suggestions you are seeing are relevant for your document by changing the document type to “Abstract” within the Academic writing style section.

You can use the Readability report to check your abstract for places to improve the clarity of your writing. Some suggestions might show you where to remove words, which is great if you’re over your word count.

We hope the five steps and examples we’ve provided help you write a great abstract for your research paper.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

46 Essays that Worked at MIT

Updated for the 2024-2025 admissions cycle.

.css-1l736oi{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;gap:var(--chakra-space-4);font-family:var(--chakra-fonts-heading);} .css-1dkm51f{border-radius:var(--chakra-radii-full);border:1px solid black;} .css-1wp7s2d{margin:var(--chakra-space-3);position:relative;width:1em;height:1em;} .css-cfkose{display:inline;width:1em;height:1em;} About MIT .css-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;}

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a world-renowned research university based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Known for its prioritization of intellectual freedom and innovation, MIT offers students an education that’s constantly on the cutting-edge of academia. The school’s star-studded roster of professors includes Nobel prize winners and MacArthur fellows in disciplines like technology, biology, and social science. A deeply-technical school, MIT offers students with the resources they need to become specialists in a range of STEM subjects. In many ways, MIT is the gold standard for creativity, critical thinking, and problem solving.

Unique traditions at MIT

1. "Ring Knocking": During the weeks preceding the MIT Commencement Ceremony, graduating students celebrate by finding a way to touch the MIT seal in the lobby of Building 10 with their newly-received class rings. 2. "Steer Roast": Every year in May, the MIT Science Fiction Society hosts a traditional event on the Killian Court lawn for incoming freshmen. During the Steer Roast, attendees cook (and sometimes eat) a sacrificial male cow and hang out outside until the early hours of the morning. 3. Pranking: Pranking has been an ongoing tradition at MIT since the 1960s. Creative pranks by student groups, ranging from changing the words of a university song to painting the Great Dome of the school, add to the quirkiness and wit of the MIT culture. 4. Senior House Seals: The all-senior undergraduate dormitory of Senior House is known for its yearly tradition of collecting and displaying seals, which are emblems that represent the class of the graduating seniors.

Programs at MIT

1. Global Entrepreneurship Lab (G-Lab): G-Lab provides undergraduate and graduate students with the skills to build entrepreneurial ventures that meet developing world challenges. 2. Mars Rover Design Team: This club is part of the MIT Student Robotics program that provides students with the engineering, design, and fabrication skills to build robots for planetary exploration. 3. Media Lab: The Media Lab is an interdisciplinary research lab that explores new technologies to allow individuals to create and manipulate communication presentation of stories, images, and sounds. 4. Independent Activities Period (IAP): A month-long intersession program that allows students to take courses and participate in extracurricular activities from flying classes to volunteering projects and sports. 5. AeroAstro: A club that provides students with the opportunity to learn about aerospace engineering and build model rockets.

At a glance…

Acceptance Rate

Average Cost

Average SAT

Average ACT

Cambridge, MA

Real Essays from MIT Admits

Prompt: mit brings people with diverse backgrounds and experiences together to better the lives of others. our students work to improve their communities in different ways, from tackling the world’s biggest challenges to being a good friend. describe one way you have collaborated with people who are different from you to contribute to your community..

Last year, my European History teacher asked me to host weekly workshops for AP test preparation and credit recovery opportunities: David, Michelangelo 1504. “*Why* is this the answer?” my tutee asked. I tried re-explaining the Renaissance. Michelangelo? The Papacy? I finally asked: “Do you know the story of David and Goliath?” Raised Catholic, I knew the story but her family was Hindu. I naively hadn’t considered she wouldn’t know the story. After I explained, she relayed a similar story from her culture. As sessions grew to upwards of 15 students, I recruited more tutors so everyone could receive more individualized support. While my school is nearly half Hispanic, AP classes are overwhelmingly White and Asian, so I’ve learned to understand the diverse and often unfamiliar backgrounds of my tutees. One student struggled to write idiomatically despite possessing extensive historical knowledge. Although she was initially nervous, we discovered common ground after I asked about her Rohan Kishibe keychain, a character from Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure. She opened up; I learned she recently immigrated from China and was having difficulty adjusting to writing in English. With a clearer understanding of her background, I could now consider her situation to better address her needs. Together, we combed out grammar mistakes and studied English syntax. The bond we formed over anime facilitated honest dialogue, and therefore genuine learning.

Essay by Víctor

i love cities <3

Prompt: We know you lead a busy life, full of activities, many of which are required of you. Tell us about something you do simply for the pleasure of it.

I slam the ball onto the concrete of our dorm’s courtyard, and it whizzes past my opponents. ******, which is a mashup of tennis, squash, and volleyball, is not only a spring term pastime but also an important dorm tradition. It can only be played using the eccentric layout of our dorm’s architecture and thus cultivates a special feeling of community that transcends grade or friend groups. I will always remember the amazing outplays from yearly tournaments that we celebrate together. Our dorm’s collective GPA may go significantly down during the spring, but it’s worth it.

Essay by Brian

CS, math, and economics at MIT

Prompt: Describe the world you come from (for example, your family, school, community, city, or town). How has that world shaped your dreams and aspirations?

The fragile glass beaker shattered on the ground, and hydrogen peroxide, flowing furiously like lava, began to conquer the floor with every inch the flammable puddle expanded. This was my solace. As an assistant teacher for a middle school STEM class on the weekends, mistakes were common, especially those that made me mentally pinpoint where we kept the fire extinguishers. However, these mishaps reminded me exactly why I loved this job (besides the obvious luxury of cleaning up spills): every failure was a chance to learn in the purest form. As we conducted chemical experiments or explored electronics kits, I was comforted by the kids’ genuine enthusiasm for exploration—a sentiment often lost in the grade-obsessed world of high school. Accordingly, I tried to help my students recognize that mistakes are often the most productive way to grow and learn. I encouraged my students to persist when faced with failure, especially those who might not have been encouraged in their everyday lives. I was there for students like Nathan, a child on the autism spectrum who reminded me of my older brother with autism. I was there for the two girls in a class of 17, reminding me of my own journey navigating the male-dominated world of STEM. I wanted to encourage them into a lifelong journey of pursuing knowledge and embracing mistakes. I may have been their mentor, but these lessons also serve as a crucial reminder to me that mistakes are not representative of one’s overall worth.

Essay by Sarah J.

cs @ stanford!! lover of STEM, taylor swift, and dogs!

.css-310tx6{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;text-align:center;gap:var(--chakra-space-4);} Find an essay from your twin at MIT .css-1dkm51f{border-radius:var(--chakra-radii-full);border:1px solid black;} .css-1wp7s2d{margin:var(--chakra-space-3);position:relative;width:1em;height:1em;} .css-cfkose{display:inline;width:1em;height:1em;}

Someone with the same interests, stats, and background as you

- Sign Up for Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

« All Events

- This event has passed.

How to Write a Great Abstract

Tuesday, january 8, 2019 @ 10:00 am - 11:15 am.

Thalia Rubio, Writing and Communication Center lecturer

Enrollment: Limited: Advance sign-up required Sign-up by 01/07 Limited to 25 participants Prereq: none

For your paper to be successful, people have to actually read it. A compelling abstract is essential for capturing their attention and making them want to read more. But writing an effective abstract is challenging because you need to summarize what motivated you, what you did, and what you found, in a small number of words. In this workshop, we’ll analyze sample abstracts from different fields, learn editing strategies, and practice revising abstracts. You’ll leave with a better understanding of how to write a strong abstract that clearly presents your research.

Contact: Steven Strang, E18-233 B, 617 253-4459, SMSTRANG@MIT.EDU

On the site

Guidelines for preparing abstracts and keywords.

The following guidelines explain how to prepare book and chapter-level abstracts and keywords for your book. The abstracts and keywords you prepare will facilitate the discovery of your book via online retailers. It will also enable us to consider the book for digital collections such as MIT Press Scholarship Online , part of the University Press Scholarship Online (UPSO) publishing platform hosted by Oxford University Press. Inclusion in such collections will increase the readership of your book and its availability in libraries worldwide.

Please use the templates below to prepare your abstracts and keywords. We will need this material when you submit your final manuscript.

Book Abstract and Keywords

The book abstract should be concise, between 5-10 sentences, around 200 words and no more than 250 words, and should provide a clear idea of the main arguments and conclusions of your book. It might be useful to use the book’s blurb as a basis for the abstract (as supplied in your Author’s Marketing Questionnaire). Where possible, the personal pronoun should not be used, but an impersonal voice adopted: ‘This chapter discusses . . .’ rather than: ‘In this chapter, I discuss . . .’

Please provide keywords that describe the content, themes, concepts, or other relevant aspects of the book. Keywords increase the likelihood that your audience will be able to find your book through search on a retail website.

- Keywords should be no more than 500-600 characters in total.

- List the most relevant keywords first.

- Do not use any special characters.

- Separate keywords with semicolons.

- Each keyword should be a single word or a 2-3 word phrase.

- For additional help creating keywords, please refer to the Guidelines and Tips document provided at the bottom of the page.

Chapter Abstracts and Keywords

Please supply an abstract for each chapter of your book, including Introductory and Concluding chapters, giving the name and number of the chapter in each case. Each chapter abstract should be concise, between 3-6 sentences, around 120 words and no more than 150 words. It should provide a clear overview of the content of the chapter. Where possible, the personal pronoun should not be used, but an impersonal voice adopted: ‘This chapter discusses . . .’ rather than: ‘In this chapter, I discuss . . .’

Please suggest 5–10 keywords for each chapter which can be used for describing the content of the chapter. They should distinguish the most important ideas, names, and concepts in the chapter.

- Each chapter keyword should be a single word or a 2-3 word phrase.

- Chapter keywords should not be too generalized.

- Each chapter keyword should appear in the accompanying chapter abstract.

- A chapter keyword can be drawn from the book or chapter title, as long as it also appears in the text of the related abstract.

Sample Abstracts and Keywords

The Act Itself

Book Abstract: The distinction between the consequences of an act and the act itself is supposed to define the fight between consequentialism and deontological moralities. This book, though sympathetic to consequentialism, aims less at taking sides in that debate than at clarifying the terms in which it is conducted. It aims to help the reader to think more clearly about some aspects of human conduct—especially the workings of the ‘by’-locution, and some distinctions between making and allowing, between act and upshot, and between foreseeing and intending (the doctrine of double effect). It argues that moral philosophy would go better if the concept of ‘the act itself’ were dropped from its repertoire.

Book Keywords : action; allowing; consequences; consequentialism; deontological ethics; double effect; ethics; intention; human conduct; human behavior; morality; moral thought; conceptual analysis; metaphysics; philosophy of action

Chapter Abstract : This chapter discusses attempts by Dinello, Kamm, Kagan, Bentham, Warren Quinn, and others to explain the making/allowing distinction. In each case, it is shown that if the proposed account can be tightened up into something significant and defensible, that always turns it into something equivalent to the analysis of Bennett (Ch. 6) or, more often, that of Donagan (Ch. 7). It is argued that on either of the latter analyses, making/allowing certainly has no basic moral significance, though it may often be accompanied by factors that do have such significance.

Chapter Keywords : allowing; Bentham; Dinello; Donagan; KaganKamm; making; Quinn

University Press Scholarship Online, Abstract and Keyword Forms

Welcome to the MIT CISR website!

This site uses cookies. Review our Privacy Statement.

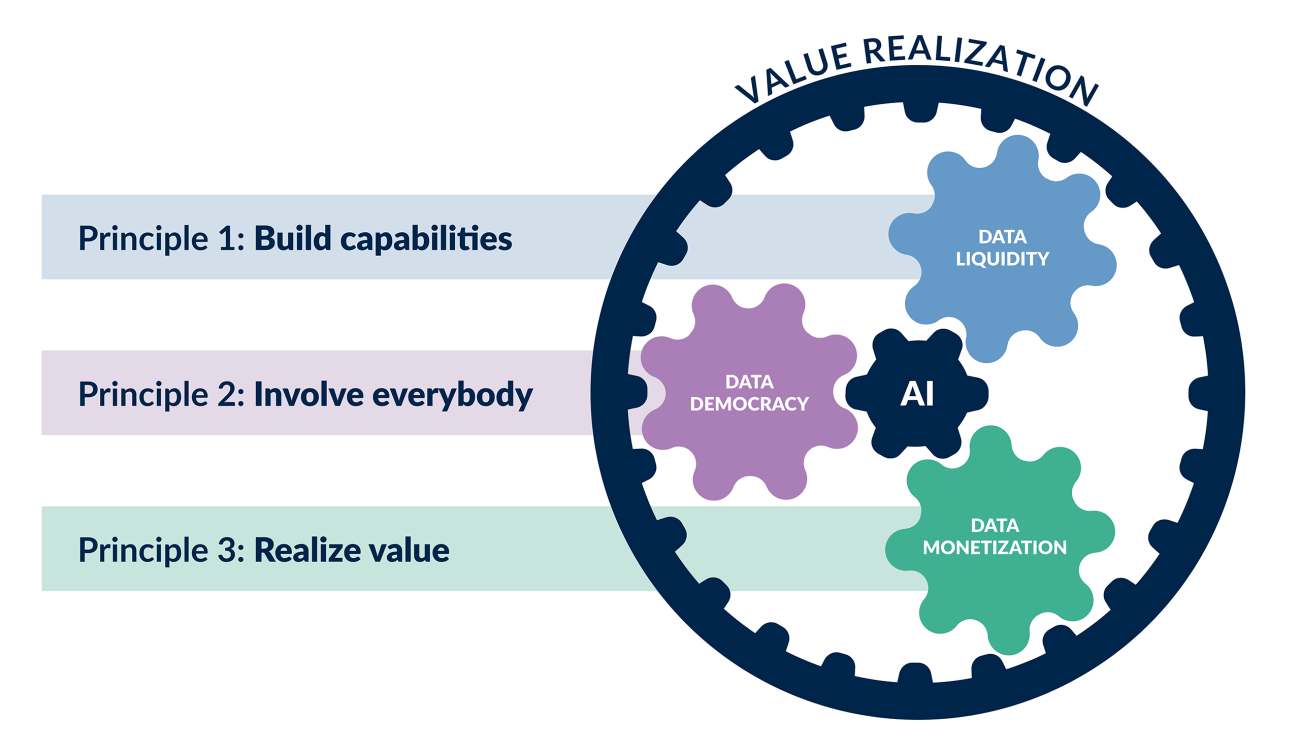

AI Is Everybody’s Business

This briefing presents three principles to guide business leaders when making AI investments: invest in practices that build capabilities required for AI, involve all your people in your AI journey, and focus on realizing value from your AI projects. The principles are supported by the MIT CISR data monetization research, and the briefing illustrates them using examples from the Australia Taxation Office and CarMax. The three principles apply to any kind of AI, defined as technology that performs human-like cognitive tasks; subsequent briefings will present management advice distinct to machine learning and generative tools, respectively.

Access More Research!

Any visitor to the website can read many MIT CISR Research Briefings in the webpage. But site users who have signed up on the site and are logged in can download all available briefings, plus get access to additional content. Even more content is available to members of MIT CISR member organizations .

Author Barb Wixom reads this research briefing as part of our audio edition of the series. Follow the series on SoundCloud.

DOWNLOAD THE TRANSCRIPT

Today, everybody across the organization is hungry to know more about AI. What is it good for? Should I trust it? Will it take my job? Business leaders are investing in massive training programs, partnering with promising vendors and consultants, and collaborating with peers to identify ways to benefit from AI and avoid the risk of AI missteps. They are trying to understand how to manage AI responsibly and at scale.

Our book Data Is Everybody’s Business: The Fundamentals of Data Monetization describes how organizations make money using their data.[foot]Barbara H. Wixom, Cynthia M. Beath, and Leslie Owens, Data Is Everybody's Business: The Fundamentals of Data Monetization , (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2023), https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048217/data-is-everybodys-business/ .[/foot] We wrote the book to clarify what data monetization is (the conversion of data into financial returns) and how to do it (by using data to improve work, wrap products and experiences, and sell informational solutions). AI technology’s role in this is to help data monetization project teams use data in ways that humans cannot, usually because of big complexity or scope or required speed. In our data monetization research, we have regularly seen leaders use AI effectively to realize extraordinary business goals. In this briefing, we explain how such leaders achieve big AI wins and maximize financial returns.

Using AI in Data Monetization

AI refers to the ability of machines to perform human-like cognitive tasks.[foot]See Hind Benbya, Thomas H. Davenport, and Stella Pachidi, “Special Issue Editorial: Artificial Intelligence in Organizations: Current State and Future Opportunities , ” MIS Quarterly Executive 19, no. 4 (December 2020), https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol19/iss4/4 .[/foot] Since 2019, MIT CISR researchers have been studying deployed data monetization initiatives that rely on machine learning and predictive algorithms, commonly referred to as predictive AI.[foot]This research draws on a Q1 to Q2 2019 asynchronous discussion about AI-related challenges with fifty-three data executives from the MIT CISR Data Research Advisory Board; more than one hundred structured interviews with AI professionals regarding fifty-two AI projects from Q3 2019 to Q2 2020; and ten AI project narratives published by MIT CISR between 2020 and 2023.[/foot] Such initiatives use large data repositories to recognize patterns across time, draw inferences, and predict outcomes and future trends. For example, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) used machine learning, neural nets, and decision trees to understand citizen tax-filing behaviors and produce respectful nudges that helped citizens abide by Australia’s work-related expense policies. In 2018, the nudging resulted in AUD$113 million in changed claim amounts.[foot]I. A. Someh, B. H. Wixom, and R. W. Gregory, “The Australian Taxation Office: Creating Value with Advanced Analytics,” MIT CISR Working Paper No. 447, November 2020, https://cisr.mit.edu/publication/MIT_CISRwp447_ATOAdvancedAnalytics_SomehWixomGregory .[/foot]

In 2023, we began exploring data monetization initiatives that rely on generative AI.[foot]This research draws on two asynchronous generative AI discussions (Q3 2023, N=35; Q1 2024, N=34) regarding investments and capabilities and roles and skills, respectively, with data executives from the MIT CISR Data Research Advisory Board. It also draws on in-progress case studies with large organizations in the publishing, building materials, and equipment manufacturing industries.[/foot] This type of AI analyzes vast amounts of text or image data to discern patterns in them. Using these patterns, generative AI can create new text, software code, images, or videos, usually in response to user prompts. Organizations are now beginning to openly discuss data monetization initiative deployments that include generative AI technologies. For example, used vehicle retailer CarMax reported using OpenAI’s ChatGPT chatbot to help aggregate customer reviews and other car information from multiple data sets to create helpful, easy-to-read summaries about individual used cars for its online shoppers. At any point in time, CarMax has on average 50,000 cars on its website, so to produce such content without AI the company would require hundreds of content writers and years of time; using ChatGPT, the company’s content team can generate summaries in hours.[foot]Paula Rooney, “CarMax drives business value with GPT-3.5,” CIO , May 5, 2023, https://www.cio.com/article/475487/carmax-drives-business-value-with-gpt-3-5.html ; Hayete Gallot and Shamim Mohammad, “Taking the car-buying experience to the max with AI,” January 2, 2024, in Pivotal with Hayete Gallot, produced by Larj Media, podcast, MP3 audio, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/taking-the-car-buying-experience-to-the-max-with-ai/id1667013760?i=1000640365455 .[/foot]

Big advancements in machine learning, generative tools, and other AI technologies inspire big investments when leaders believe the technologies can help satisfy pent-up demand for solutions that previously seemed out of reach. However, there is a lot to learn about novel technologies before we can properly manage them. In this year’s MIT CISR research, we are studying predictive and generative AI from several angles. This briefing is the first in a series; in future briefings we will present management advice specific to machine learning and generative tools. For now, we present three principles supported by our data monetization research to guide business leaders when making AI investments of any kind: invest in practices that build capabilities required for AI, involve all your people in your AI journey, and focus on realizing value from your AI projects.

Principle 1: Invest in Practices That Build Capabilities Required for AI

Succeeding with AI depends on having deep data science skills that help teams successfully build and validate effective models. In fact, organizations need deep data science skills even when the models they are using are embedded in tools and partner solutions, including to evaluate their risks; only then can their teams make informed decisions about how to incorporate AI effectively into work practices. We worry that some leaders view buying AI products from providers as an opportunity to use AI without deep data science skills; we do not advise this.

But deep data science skills are not enough. Leaders often hire new talent and offer AI literacy training without making adequate investments in building complementary skills that are just as important. Our research shows that an organization’s progress in AI is dependent on having not only an advanced data science capability, but on having equally advanced capabilities in data management, data platform, acceptable data use, and customer understanding.[foot]In the June 2022 MIT CISR research briefing, we described why and how organizations build the five advanced data monetization capabilities for AI. See B. H. Wixom, I. A. Someh, and C. M. Beath, “Building Advanced Data Monetization Capabilities for the AI-Powered Organization,” MIT CISR Research Briefing, Vol. XXII, No. 6, June 2022, https://cisr.mit.edu/publication/2022_0601_AdvancedAICapabilities_WixomSomehBeath .[/foot] Think about it. Without the ability to curate data (an advanced data management capability), teams cannot effectively incorporate a diverse set of features into their models. Without the ability to oversee the legality and ethics of partners’ data use (an advanced acceptable data use capability), teams cannot responsibly deploy AI solutions into production.

It’s no surprise that ATO’s AI journey evolved in conjunction with the organization’s Smarter Data Program, which ATO established to build world-class data analytics capabilities, and that CarMax emphasizes that its governance, talent, and other data investments have been core to its generative AI progress.

Capabilities come mainly from learning by doing, so they are shaped by new practices in the form of training programs, policies, processes, or tools. As organizations undertake more and more sophisticated practices, their capabilities get more robust. Do invest in AI training—but also invest in practices that will boost the organization’s ability to manage data (such as adopting a data cataloging tool), make data accessible cost effectively (such as adopting cloud policies), improve data governance (such as establishing an ethical oversight committee), and solidify your customer understanding (such as mapping customer journeys). In particular, adopt policies and processes that will improve your data governance, so that data is only used in AI initiatives in ways that are consonant with your organization's values and its regulatory environment.

Principle 2: Involve All Your People in Your AI Journey