Username or Email Address

Remember Me Forgot Password?

Get New Password

- Dog Science: New Scientific Discoveries About Dogs

- By K9 Magazine

- March 24, 2021

- In Dog Science

For as long as there has been scientific research , dogs have made for one of the most fascinating areas of study. We love dogs and they love us right back ( or, do they ?).

At K9 Magazine we want to connect you with the latest, most interesting dog science and canine focused research.

You'll be able to learn more about the science of dog health, nutrition and canine behaviour. All areas of the human / canine relationship, the evolution of dogs and the science behind illness and disease affecting dogs.

This page is our new dog science hub and from here we'll constantly add new research, studies and data on scientific dog topics.

So, if dogs with a healthy serving of science on the side sounds like the sort of thing that rings your bell , you'll want to bookmark this page.

Dog Science & Canine Research: Updated March 2021

The role of companion animals and loneliness during the global pandemic

Published: 19/03/21 - Source: MDPI

This study assessed the relationship between pet ownership, pet attachment, loneliness, and coping with stress before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Contrary to our hypotheses, results did not support the presence of a buffering effect of pet ownership on loneliness, with pet ownership predicting increases in loneliness from pre-pandemic to during the pandemic.

Dog owners showed lower levels of loneliness prior to the pandemic as well as higher levels of attachment, suggesting possible species-level differences in these relationships.

Pet owners also reported spending time with their pet as a highly used strategy for coping with stress, suggesting that future research should explore the role of pets in coping with stress and social isolation during the pandemic. These results indicate that the relationship between pet ownership and adolescent loneliness during the pandemic is complex and warrants further research.

In short : This study says that dog owners are generally less lonely with higher attachment; but this did not make dog owners feel any less alone during the pandemic related lockdowns and isolation than non dog owners.

Read In Full ⇢

Dogs recognise dogs when watching videos

Published: 19/03/21 - Source: Springer

Several aspects of dogs’ visual and social cognition have been explored using bi-dimensional representations of other dogs. It remains unclear, however, if dogs do recognize as dogs the stimuli depicted in such representations, especially with regard to videos.

To test this, 32 pet dogs took part in a cross-modal violation of expectancy experiment, during which dogs were shown videos of either a dog and that of an unfamiliar animal, paired with either the sound of a dog barking or of an unfamiliar vocalization .

This study provides the first evidence that dogs recognize videos of dogs as actually representing dogs. These findings will hopefully be a starting point towards the more extensive use of videos in dog behavioural and cognitive research.

In short : This study reveals that yes, dogs can and do recognise dogs on screen and they tend to be more interested in watching their own species than other animals.

Similar studies

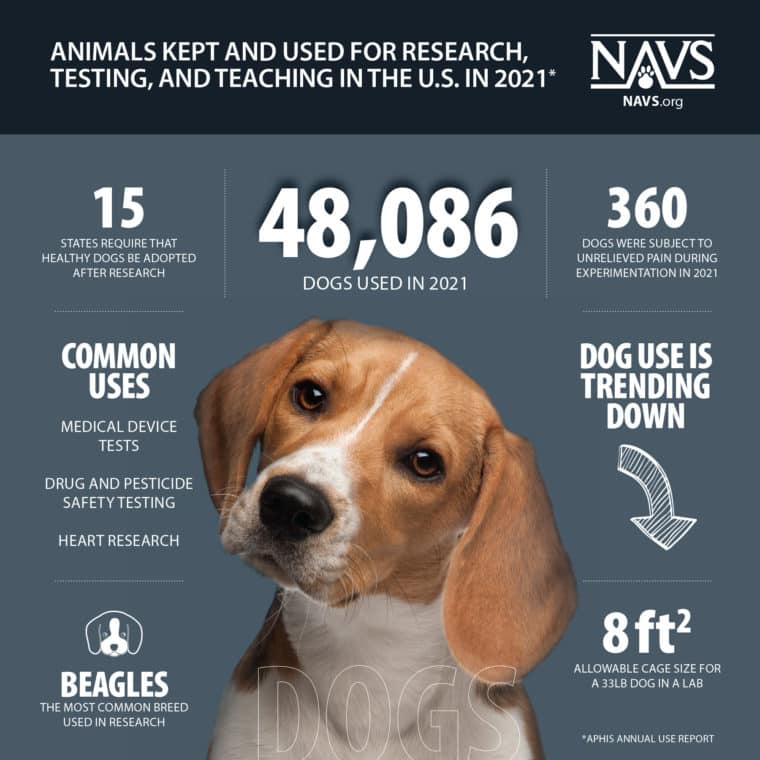

Dogs provide clues for treating cancer in humans

Published: 03/17/21 - Source: Nature

Research using pet dogs as animal models of cancer is helping to inform treatments for human patients — and vice versa.

Researchers at the Sanger Institute are launching a study sequencing about 100 known cancer genes in multiple canine tumours in order to look for similarities in molecular profiles that can then be compared with human cancers.

In short : Dogs are proving to be man's best friend once more as they provide evidence of cancer treatment approaches that could benefit humans.

Dogs can detect coronavirus in seconds

Published: 03/17/21 - Source: Reuters

Thai sniffer dogs trained to detect COVID-19 in human sweat proved nearly 95% accurate during training and could be used to identify coronavirus infections at busy transport hubs within seconds, the head of a pilot project said.

Six Labrador Retrievers participated in a six-month project that included unleashing them to test an infected patient’s sweat on a spinning wheel of six canned vessels.

“The dogs take only one to two seconds to detect the virus,” Professor Kaywalee Chatdarong, the leader of the project at the veterinary faculty of Thailand’s Chulalongkorn University, told Reuters.

“Within a minute, they will manage to go through 60 samples.”

In short : Dogs are able to detect the presence of coronavirus (covid 19) . The aim is to deploy the dogs to detect coronavirus as passengers move through airport security.

The effects of dog domestication on gut microbiota

Published: 03/23/21 - Source: PubMed

Living inside our gastrointestinal tracts is a large and diverse community of bacteria called the gut microbiota that plays an active role in basic body processes like metabolism and immunity. Much of our current understanding of the gut microbiota has come from laboratory animals like mice, which have very different gut bacteria to mice living in the wild. However, it was unclear whether this difference in microbes was due to domestication, and if it could also be seen in other domesticated-wild pairs, like pigs and wild boars or dogs and wolves.

The results showed that while domesticated animals have different sets of bacteria in their guts, leaving the wild has changed the gut microbiota of these diverse animals in similar ways. To explore what causes these shared patterns, Reese et al. swapped the diets of two domesticated-wild pairs: laboratory and wild mice, and dogs and wolves. They found this change in diet shifted the gut bacteria of the domesticated species to be more similar to that of their wild counterparts, and vice versa.

In short : In the future, these insights could help identify new ways to alter the gut microbiota to improve animal or human health.

Breed disposition toward obesity

Published: 23/03/21 - Source: PubMed

A retrospective study to evaluate the prevalence and risk factors for overweight status in dogs under primary veterinary care in the UK.

There were 1580 of 22,333 dogs identified as overweight during 2016. The estimated 1-year period prevalence for overweight status recorded in dogs under veterinary care was 7.1% (95% confidence interval 6.7-7.4).

After accounting for confounding factors, eight breeds showed increased odds of overweight status compared with crossbred dogs.

Breeds at highest risk of being obese were:

- Pug (OR 3.12, 95% confidence interval 2.31 to 4.20)

- Beagle (OR 2.67, 1.75 to 4.08)

- Golden Retriever (OR 2.58, 1.79 to 3.74)

- English Springer Spaniel (OR 1.98, 1.31 to 2.98).

Being neutered, middle-aged and insured were additionally associated with overweight status.

In short : Targeted overweight prevention strategies should be prioritised for dog breeds that are more predisposed toward obesity, such as Pugs and Beagles. The findings additionally raise questions about further preventative efforts following neutering. The prevalence estimate suggests veterinary professionals are underreporting overweight status and therefore could be missing key welfare opportunities.

An additional study on canine obesity was conducted in February 2021, the key findings were:

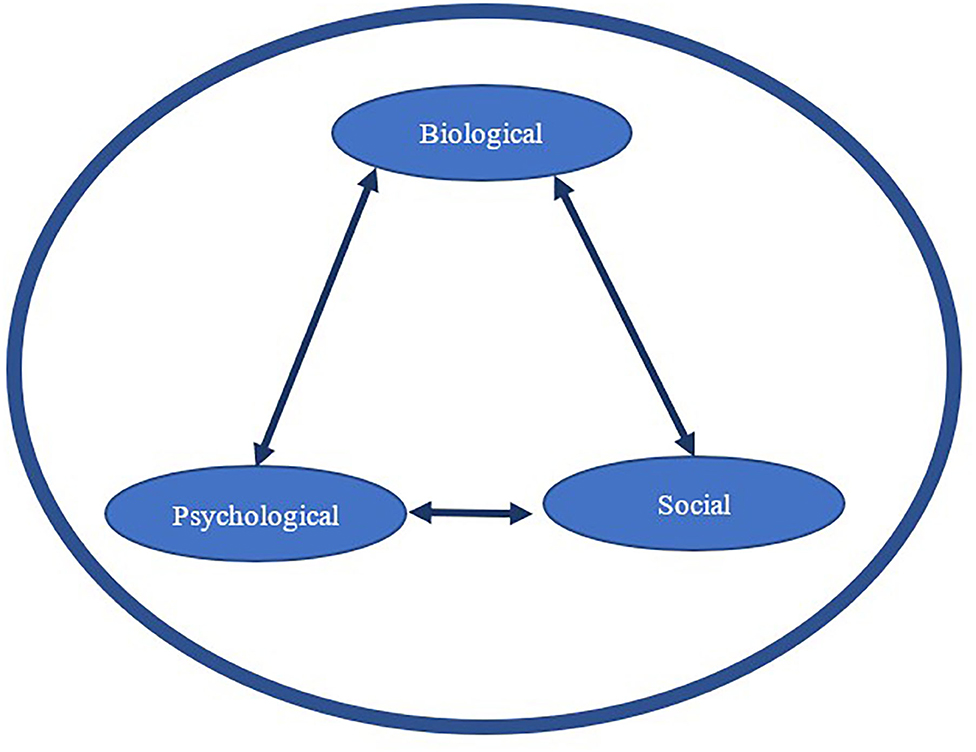

Attachment theory posits that patterns of interaction derived from the attachment system provide a starting point for understanding how people both receive and provide care.

Extending this theory to human-animal interactions provides insights into how human psychology affects pets, such as pet obesity. The goal of this study was to determine how attachment anxiety and avoidance might contribute to pet obesity.

Findings suggest that attachment plays a unique role in shaping the pet-caregiver relationship and influences various elements that contribute to pet obesity, particularly in dogs. As such, the findings may lend a novel perspective to strategies for reducing pet obesity and provide a framework for future research into pet health.

Dog science articles in K9 Magazine

- We Need To Talk About Antibiotic Resistance In Pets

- How Much Sleep Does Your Dog Need? (Ultimate Guide To Dog Sleep)

- A Better Understanding Of Dog Breed Lifespans

- Why Do Some Dogs Have Different Coloured Eyes? (Heterochromia Explained)

- Punishment vs Reward – Which Dog Training Method Works Best?

- What Is Your Dog Really Thinking About? (Video)

- Where Did COVID-19 Come From? Not Dogs, Scientists Say

- Meet Storm: This Special Dog Is Being Trained to Detect Covid-19

- How Would Your Dog React If They Were Put in This Position?

- Is There Such a Thing as Being Too Passionate About Your Pet?

- How Strong Is A Dog’s Sense Of Smell? (It’s Actually Mind-Blowing)

- Do Dogs Understand Time? Apparently So – Here’s How We Know

- Why Do Dogs Lick Their Lips? The Answer Is Surprising

- COVID-19: Why Medical Research Using Dogs Is Barking up the Wrong Tree

- Pets Can Protect Against Suicide in Older People, New Study Says

- Meet the World’s First Dogs to Detect Lung Infections

- What Does a Medical Alert Dog Do?

- How Smart Is Your Dog?

- The Myths About Dogs & Asthma

See more canine science articles from K9 Magazine

K9 Magazine

K9 Magazine is your digital destination helping you have a happier, healthier dog. Here you'll find advice on everything from dog training to dog diet advice as well as interviews with well known dog lovers and insightful features on the broadest range of canine lifestyle topics.

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Name *

Email *

Add Comment *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Science | December 2020

The New Science of Our Ancient Bond With Dogs

A growing number of researchers are hot on the trail of a surprisingly profound question: What makes dogs such good companions?

:focal(294x74:295x75)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/c2/69c237b7-71cf-4164-ab9d-3641e68efdc1/yorkipoo-mobile.jpg)

By Jeff MacGregor

Photographs by Daniel Dorsa

This is a love story.

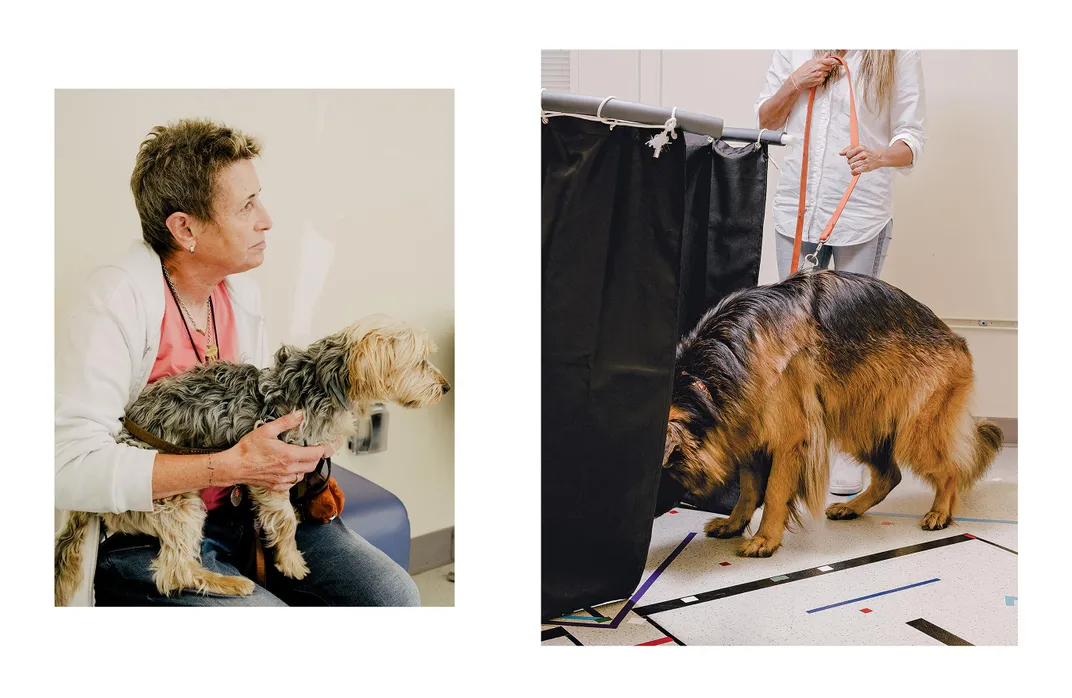

First, though, Winston is too big. The laboratory drapery can conceal his long beautiful face or his long beautiful tail, but not both. The researchers need to keep him from seeing something they don’t want him to see until they’re ready for him to see it. So during today’s brief study Winston’s tail will from time to time fly like a wagging pennant from behind a miniature theater curtain. Winston is a longhaired German shepherd.

This room at the lab is small and quiet and clean, medium-bright with ribs of sunlight on the blinds and a low, blue overhead fluorescence. Winston’s guardian is in here with him, as always, as is the three-person team of scientists. They’ll perform a short scene—a kind of behavioral psychology kabuki—then ask Winston to make a decision. A choice. Simple: either/or. In another room, more researchers watch it all play out on a video feed.

In a minute or two, Winston will choose.

And in that moment will be a million years of memory and history, biology and psychology and ten thousand generations of evolution—his and yours and mine—of countless nights in the forest inching closer to the firelight, of competition and cooperation and eventual companionship, of devotion and loyalty and affection.

It turns out studying dogs to find out how they learn can teach you and me what it means to be human.

It’s late summer at Yale University. The laboratory occupies a pleasant white cottage on a leafy New Haven street a few steps down Science Hill from the divinity school.

I’m here to meet Laurie Santos, director of the Comparative Cognition Laboratory and the Canine Cognition Center . Santos, who radiates the kind of energy you’d expect from one of her students, is a psychologist and one of the nation’s preeminent experts on human cognition and the evolutionary processes that inform it. She received undergraduate degrees in biology and psychology and a PhD in psychology, all from Harvard. She is a TED Talks star and a media sensation for teaching the most popular course in the history of Yale, “ Psychology and the Good Life, ” which most folks around here refer to as the Happiness Class (and which became “ The Happiness Lab ” podcast). Her interest in psychology goes back to her girlhood in New Bedford, Massachusetts. She was curious about curiosity, and the nature of why we are who we are. She started out studying primates, and found that by studying them she could learn about us. Up to a point.

“My entry into the dog work came not from necessarily being interested in dogs per se, but in theoretical questions that came out of the primate work.” She recalls thinking of primates, “If anybody’s going to share humanlike cognition, it’s going to be them.”

But it wasn’t. Not really. We’re related, sure, but those primates haven’t spent much time interacting with us. Dogs are different. “Here’s this species that really is motivated to pay attention to what humans are doing. They really are clued in, and they really seem to have this communicative bond with us.” Over time, it occurred to her that understanding dogs, because they are not only profoundly attuned to but also shaped by people over thousands of years, would open a window on the workings of the human mind, specifically “the role that experience plays in human cognition.”

So we’re not really here to find out what dogs know, but how dogs know. Not what they think, but how they think. And more important, how that knowing and thinking reflect back on us. In fact, many studies of canine cognition here and around the academic world mimic or began as child development studies.

Understand, these studies are entirely behavioral. It’s problem-solving. Puzzle play. Selection-making. Either/or. No electrodes, no scans, no scanners. Nothing invasive. Pavlov? Doesn’t ring a bell.

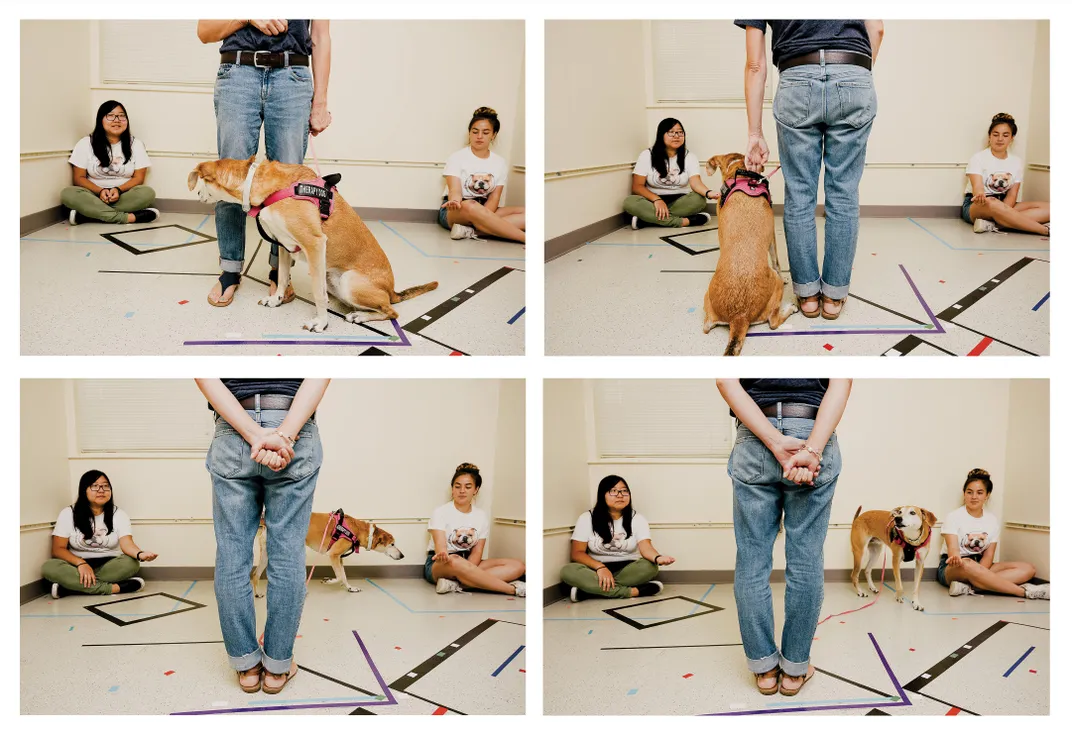

Zach Silver is a PhD student in the Yale lab; we’re watching his study today with Winston. Leashed and held by his owner, Winston will be shown several repetitions of a scene performed in silence by two of the researchers. Having watched them interact, Winston will then be set loose. Which of the researchers he “chooses”—that is, walks to first—will be recorded. And over hundreds of iterations of the same scene shown to different dogs, patterns of behavior and preference will begin to emerge. Both researchers carry dog treats to reward Winston for whichever choice he makes—because you incentivize dogs the same way you incentivize sportswriters or local politicians, with free food, but the dogs require much smaller portions.

In some studies the researchers/actors might play out brief demonstrations of cooperation and non-cooperation, or dominance and submission. Imagine a dog is given a choice between someone who shares and someone who doesn’t. Between a helper and a hinderer. The experiment leader requests a clipboard. The helper hands it over cheerfully. The hinderer refuses. Having watched a scene in which one researcher shares a resource and another does not, who will the dog choose?

The question is tangled up with our own human prejudices and preconceptions, and it’s never quite as simple as it looks. Helping, Silver says, is very social behavior, which we tend to think dogs should value. “When you think about dogs’ evolutionary history, being able to seek out who is prosocial, helpful, that could have been very important, essential for survival.” On the other hand, a dog might choose for “selfishness” or for “dominance” or for “aggression” in a way that makes sense to him without the complicating lens of a human moral imperative. “There could be some value to [the dog] affiliating with someone who is stockpiling resources, holding onto things, maybe not sharing. If you’re in that person’s camp, maybe there’s just more to go around.” Or in certain confrontational scenarios, a dog may read dominance in a researcher merely being deferred to by another researcher. Or a dog may just choose the fastest route to the most food.

What Silver is trying to tease out with today’s experiment is the most elusive thing of all: intention.

“I think intention may play a large role in dogs’ evaluation of others’ behavior,” says Silver. “We may be learning more about how the dog mind works or how the nonhuman mind works broadly. That’s one of the really exciting places we are moving in this field, is to understand the small cognitive building blocks that might contribute to valuations. My work in particular is focused on seeing if domestic dogs share some of these abilities with us.”

As promising as the field is, in some ways it seems that dog nature, like human nature, is infinitely complex. Months later, in a scientific paper , Silver and others will point out that “humans evaluate other agents’ behavior on a variety of different dimensions, including morally, from a very early age” and that “given the ubiquity of dog-human social interactions, it is possible that dogs display humanlike social evaluation tendencies.” Turns out that a dog’s experience seems important. “Trained agility dogs approached a prosocial actor significantly more often than an antisocial actor, while untrained pet dogs showed no preference for either actor,” the researchers found. “These differences across dogs with different training histories suggest that while dogs may demonstrate preferences for prosocial others in some contexts, their social evaluation abilities are less flexible and less robust compared to those of humans.”

Santos explained, “Zach’s work is beginning to give us some insight into the fact that dogs can categorize human actions, but they require certain kinds of training to do so. His work raises some new questions about how experience shapes canine cognition.”

It’s important to create experiments measuring the dog’s actual behaviors rather than our philosophical or social expectation of those behaviors. Some of the studies are much simpler, and don’t try to tease out how dogs perceive the world and make decisions to move through it. Rather than trying to figure out if a dog knows right from wrong, these puzzles ask whether the dog knows right from left.

An example of which might be showing the subject dog two cups. The cup with the treat is positioned to her left, near the door. Do this three times. Now, reversing her position in the room, set her loose. Does she head for the cup near the door, now on her right? Or does she go left again? Does she orient things in the world based on landmarks? Or based on her own location in the world? It’s a simple experimental premise measuring a complex thing: spatial functioning.

In tests like these, you’ll often see the dog look back at her owner, or guardian, for a tip, a hint, a clue. Which is why the guardians are all made to wear very dark sunglasses and told to keep still.

In some cases, the dog fails to make any choice at all. Which is disappointing to the researchers, but seems to have no impact on the dog—who will still be hugged and praised and tummy-rubbed on the way out the door.

Every dog and every guardian here is a volunteer. They come from New Haven or drive in from nearby Connecticut towns for an appointment at roughly 45-minute intervals. They sign up on the lab’s website. Some dogs and guardians return again and again because they enjoy it so much.

It’s confusing to see the sign-up sheet without knowing the dog names from the people names.

Winston’s owner, human Millie, says, “The minute I say ‘We’re going to Yale,’ Winston perks up and we’re in the car. He loves it and they’re so good to him; he gets all the attention.”

And dog Millie’s owner, Margo, says, “At one point at the end they came up with this parchment. You open it up and it says that she’s been inducted into Scruff and Bones, with all the rights and privileges thereof.”

The dogs are awarded fancy Yale dogtorates and are treated like psych department superstars. Which they are. Without them, this relatively new field of study couldn’t exist.

All the results of which will eventually be synthesized, not only by Santos, but by researchers the world over into a more complete map of human consciousness, and a better, more comprehensive Theory of Mind. I asked Santos about that, and any big breakthrough moments she’s experienced so far. “Our closest primary relatives—primates—are not closest to us in terms of how we use social information. It might be dogs ,” she says. “Dogs are paying attention to humans.”

Santos also thinks about the potential applications of canine cognition research. “More and more, we need to figure out how to train dogs to do certain kinds of things,” she says. “There are dogs in the military, these are service dogs. As our boomers are getting older, we’re going to be faced with more and more folks who have disabilities, who have loneliness, and so on. Understanding how dogs think can help us do that kind of training.”

In that sense, dogs may come to play an even larger role in our daily lives. Americans spent nearly $100 billion on their pets in 2019, maybe half of which was spent on dogs. The rest was embezzled, then gambled away—by cats.

From cave painting to The Odyssey to The Call of the Wild , the dog is inescapable in human art and culture. Anubis or Argos, Bau or Xolotl, Rin Tin Tin or Marmaduke, from the religious to the secular, Cerberus to Snoopy, from the Egyptians and the Sumerians and the Aztecs to the canine stunt coordinators of Hollywood, the dog is everywhere with us, in us and around us. As a symbol of courage or loyalty, as metaphor and avatar, as a bad dog, mad dog, “release the hounds” evil, or as a screenwriter’s shorthand for goodness, the dog is tightly woven into our stories.

Maybe the most interesting recent change, to take the movie dog as an example, is the metaphysical upgrade from Old Yeller to A Dog’s Purpose and its sequel, A Dog’s Journey . In the first case, the hero dog sacrifices himself for the family, and ascends to his rest, replaced on the family ranch by a pup he sired. In the latter two, the same dog soul returns and returns and returns, voiced by actor Josh Gad, reincarnating and accounting his lives until he reunites with his original owner. Sort of a Western spin on karma and the effort to perfect an everlasting self.

But even that kind of cultural shift pales compared with the dog’s journey in the real world. Until about a century ago, in a more agrarian time, the average dog was a fixture of the American barnyard. An affectionate and devoted farmhand, sure, herder of sheep, hunting partner or badger hound, keeper of the night watch, but not much different from a cow, a horse or a mule in terms of its utility and its relationship to the family.

By the middle of the 20th century, as we urbanized and suburbanized, the dog moved too—from the back forty to the backyard.

Then, in the 1960s, the great leap—from the doghouse onto the bedspread, thanks to flea collars. With reliable pest control, the dog moves into the house. Your dog is no longer an outdoor adjunct to the family, but a full member in good standing.

There was a book on the table in the waiting room at Yale. The Genius of Dogs , by Brian Hare and Vanessa Woods. Yiyun Huang, the lab manager of the Canine Cognition Center at the time, handed it to me. “You should read this,” she said.

Then I flew to Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

Not long after I stepped off the plane I walked straight into a room full of puppies.

The Duke Canine Cognition Center is the brain-child of an evolutionary anthropologist named Brian Hare. His CV runs from Harvard to the Max Planck Institute and back. He is a global leader in the study of dogs and their relationships to us and to each other and to the world around them. He started years ago by studying his own dog in the family garage. Now he’s a regular on best-seller lists.

Like Santos, he’s most interested in the ways dogs inform us about ourselves. “Nobody understands why we’re working with dogs to understand human nature—until we start talking about it,” he says. “Laugh if you want, but dogs are everywhere humans are, and they’re absolutely killing it evolutionarily. I love wolves, but the truth is they’re really in trouble”—as our lethal antipathy to them bears out. “So whatever evolutionarily led to dogs, and I think we have a good idea of that, boy, they made a good decision.”

Ultimately, Hare says, what he’s studying is trust. How is it that dogs form a bond with a new person? How do social creatures form bonds with one another? Developmental disorders in people may be related to problems in forming bonds—so, from a scientific perspective, dogs can be a model of social bonding.

Hare works with research scientist Vanessa Woods, also his wife and co-author. It was their idea to start a puppy kindergarten here. The golden and Labrador retriever-mix puppies are all 10 weeks old or so when they arrive, and will be studied at the same time they’re training to become service dogs for the nonprofit partner Canine Companions for Independence . The whole thing is part of a National Institutes of Health study : Better understanding of canine cognition means better training for service dogs.

Because dogs are so smart—and so trainable— there’s a whole range of assistance services they can be taught. There are dogs who help people with autism, Woods tells me. “Dogs for PTSD, because they can go in and spot-check a room. They can turn the lights on. They can, if someone’s having really bad nightmares, embrace them so just to ground them. They can detect low blood sugar, alert for seizures, become hearing dogs so they can alert their owner if someone’s at the door, or if the telephone’s ringing.”

Canines demonstrate a remarkable versatility. “A whole range of incredibly flexible, cognitive tasks,” she says, “that these dogs do that you just can’t get a machine to do. You can get a machine to answer your phone—but you can’t get a machine to answer your phone, go do your laundry, hand you your credit card, and find your keys when you don’t know where they are.” Woods and I are on the way out of the main puppy office downstairs, where the staff and student volunteers gather to relax and rub puppy tummies between studies.

It was in their book that I first encountered the idea that, over thousands of years, evolution selected and sharpened in dogs the traits most likely to succeed in harmony with humans. Wild canids that were affable, nonaggressive, less threatening were able to draw nearer to human communities. They thrived on scraps, on what we threw away. Those dogs were ever so slightly more successful at survival and reproduction. They had access to better, more reliable food and shelter. They survived better with us than without us. We helped each other hunt and move from place to place in search of resources. Kept each other warm. Eventually it becomes a reciprocity not only of efficiency, but of cooperation, even affection. Given enough time, and the right species, evolution selects for what we might call goodness. This is the premise of Hare and Woods’ new book, Survival of the Friendliest .

If that strikes you as too philosophical, over-romantic and scientifically spongy, there’s biochemistry at work here too. Woods explained it while we took some puppies for a walk around the pond just down the hill from the lab. “So, did you see that study that dogs hijack the oxytocin loop ?”

I admitted I had not.

Oxytocin is a hormone produced in the hypothalamus and released by the pituitary gland. It plays an important role in human bonding and social interaction, and makes us feel good about everything from empathy to orgasm. It is sometimes referred to as the “love hormone.”

Woods starts me out with the underpinnings of these kinds of studies—on human infants. “Human babies are so helpless,” she says. “You leave them alone for ten minutes and they can literally die. They keep you up all night, they take a lot of energy and resources. And so, how are they going to sort of convince you to take care of them?”

What infants can do, she says, “is they can look at you.”

And so this starts an oxytocin loop where the baby looks at you and your oxytocin goes up, and you look at the baby and the baby’s oxytocin goes up. One of the things oxytocin does is elicit caregiving toward someone you see as part of your group.

Dogs, it turns out, have hijacked that process as well. “When a dog is looking at me,” Woods says, “his oxytocin is going up and my oxytocin is going up.” Have you ever had a moment, she asks, when your dog looks at you, and you just don’t know what the dog wants? The dog has already been for a walk, has already been fed.

“Sure,” I responded.

“It’s just kind of like they’re trying to hug you with their eyes,” she says.

Canine eyebrow muscles, it turns out, may have evolved to reveal more of the sclera, the whites of the eyes. Humans share this trait. “Our great ape relatives hide their eyes,” Woods says. “They don’t want you to know where they’re looking, because they have a lot more competition. But humans evolved to be superfriendly, and the sclera is part of that.”

So, it’s eye muscles and hormones, not just sentiment.

In the lab here at Duke, I see puppies and researchers work through a series of training and problem-solving scenarios. For example, the puppy is shown a treat from across the room, but must remain stationary until called forward by the researcher.

“Puppy look. Puppy look.”

Puppy looks.

“Puppy stay.”

Puppy stays.

“Puppy fetch.”

Puppy wobbles forward on giant paws to politely nip the tiny treat and to be effusively praised and petted. Good puppy!

The problem-solving begins when a plexiglass shield is placed between the puppy and the treat.

“Puppy look.”

Puppy does so.

Puppy wobbles forward, bonks snout on plexiglass. Puppy, vexed, tries again. How fast the puppy susses out a new route to the food is a good indication of patience and diligence and capacity for learning. Over time the plexiglass shields become more complicated and the puppies need to formulate more complex routes and solutions. As a practical matter, the sooner you can find out which of these candidate puppies is the best learner, the most adaptive, the best suited to the training—and which is not—the better. Early study of these dogs is a breakthrough efficiency in training.

I asked Hare where all this leads. “I’m very excited about this area of how we view animals informs how we view each other. Can we harness that? Very, very positive. We’re working already on ideas for interventions and experiments.”

Second, Hare says, much of their work has focused on “how to raise dogs.” He adds, “I could replace dogs with kids .” Thus the implications are global: study puppies, advance your understanding of how to nurture and raise children.

“There’s nice evidence that we can immunize ourselves from some of the worst of our human nature,” Hare recently told the American Psychological Association in an interview , “and it’s similar to how we make sure that dogs are not aggressive to one another: We socialize them. We want puppies to see the world, experience different dogs and different situations. By doing that for them when they’re young, they aren’t threatened by those things. Similarly, there is good evidence that you can immunize people from dehumanizing other groups just through contact between those groups, as long as that contact results in friendship.”

Evolutionary processes buzz and sputter all around us every moment. Selection never sleeps. In fact, Hare contributed to a new paper released this year on how rapidly coyote populations adapt to humans in urban and suburban settings. “How animal populations adapt to human-modified landscapes is central to understanding modern behavioural evolution and improving wildlife management. Coyotes ( Canis latrans ) have adapted to human activities and thrive in both rural and urban areas. Bolder coyotes showing reduced fear of humans and their artefacts may have an advantage in urban environments.”

The struggle between the natural world and the made world is everywhere constant, and not all possible outcomes lead to friendship. Just ask those endangered wolves—if you can find one.

The history of which perhaps seems distant from the babies and the students and these puppies. But to volunteer for this program is to make a decision for extra-credit joy. This is evident toward the end of my day in Durham. Out on the lab’s playground where the students, puppy and undergraduate alike, roll and wrestle and woof and slobber under that Carolina blue sky.

In rainy New York City, I spent an afternoon with Alexandra Horowitz, founder and director of the Horowitz Dog Cognition Lab at Barnard College, and the best-selling author of books including Being a Dog, Inside of a Dog, and Our Dogs, Ourselves . She holds a doctorate in cognitive science, and is one of the pioneers of canine studies.

It is her belief that we started studying dogs only after all these years because they’ve been studying us.

She acknowledges that other researchers in the field have their own point of view. “The big theme is, What do dogs tell us about ourselves?” Horowitz says. “I am a little less interested in that.” She is more interested in the counter question: What do cognition studies tell us about dogs ?

Say you get a dog, Horowitz suggests. “And a week into living with a dog, you’re saying ‘He knows this.’ Or ‘She is holding a grudge’ or, ‘He likes this.’ We just barely met him, but we’re saying things that we already know about him—where we wouldn’t about the squirrel outside.”

Horowitz has investigated what prompts us to make such attributions. For instance, she led a much-publicized 2009 study of the “guilty look.”

“Anthropomorphisms are regularly used by owners in describing their dogs,” Horowitz and co-authors write. “Of interest is whether attributions of understanding and emotions to dogs are sound, or are unwarranted applications of human psychological terms to nonhumans. One attribution commonly made to dogs is that the ‘guilty look’ shows that dogs feel guilt at doing a disallowed action.” In the study, the researchers observed and video-recorded a series of 14 dogs interacting with their guardians in the lab. Put a treat in a room. Tell the dog not to eat it. The owner leaves the room. Dog eats treat. Owner returns. Does the dog have a “guilty look”? Sometimes yes, sometimes no, but the outcome, it turns out, was generally related to the owner’s reaction—whether the dog was scolded, for instance. Conclusion: “These results indicate that a better description of the so-called guilty look is that it is a response to owner cues, rather than that it shows an appreciation of a misdeed.”

She has also focused on a real gap in the field, a need to investigate the perceptual world of the dog, in particular, olfaction. What she calls “nosework.” She asks what it might be like “to be an olfactory creature, and how they can smell identity or smell quantity or smell time, potentially. I am always interested in the question: What is the smell angle here?”

Earlier this year, for instance, her group published a study, “ Discrimination of Person Odor by Owned Domestic Dogs ,” which “investigated whether owned dogs spontaneously (without training) distinguished their owner’s odor from a stranger’s odor.” Their main finding: Dogs were able to distinguish between the scent of a T-shirt that had been worn overnight by a stranger and a T-shirt that had been worn overnight by their owner, without the owner present. The result “begins to answer the question of how dogs recognize and represent humans, including their owners.”

It’s widely known and understood that dogs outsmell us, paws down. Humans have about six million olfactory receptors. Dogs as many as 300 million. We sniff indifferently and infrequently. Dogs, however, sniff constantly, five or ten times a second, and map their whole world that way. In fact, in a recent scientific journal article, Horowitz makes plain that olfaction is too rarely accounted for in canine cognition studies and is a significant factor that needs to be accorded much greater priority.

As I walked outside into the steady city drizzle, I thought back to Yale and to Winston, in his parallel universe of smell, making his way out of the lab, sniffing every hand and every shoe as we piled on our praise. Our worlds overlap, but aren’t the same. And as Winston fanned the air with his tail, ready to get back in the car for home, my hand light on his flank, I asked him the great unanswerable, the final question at the heart of every religious system and philosophical inquiry in the history of humanity.

“Who’s a good boy?”

So I sat down again with Laurie Santos. New Haven and Science Hill and the little white laboratory were all quiet under a late summer sun.

I wanted to explore an idea from Hare’s book, which is how evolution could select for sociability, friendliness, “goodness.” Over the generations, the thinking goes, eventually we get more affable, willing dogs—but we also get smarter dogs. Because affability, unbeknownst to anybody, also selects for intelligence. I saw in that a cause for human optimism.

“I think we’ve shaped this creature in our image and likeness in a lot of ways,” Santos tells me. “And the creature that’s come out is an incredibly loving, cooperative, probably smart relative to some other ancestral canid species. The story is, we’ve built this species that has a lot of us in them—and the parts of us that are pretty good, which is why we want to hang out with them so much. We’ve created a species that wants to bond with us and does so really successfully.”

Like Vanessa Woods and Brian Hare, she returns to the subject of human infants.

“What makes humans unique relative to primates?” she asks. “The fact that babies are looking into your eyes, they really want to share information with you. Not stuff that they want, it’s just simply this motivation to share. And that emerges innately. It’s the sign that you have a neurotypical baby. It’s a fundamental thread through the entire life course. The urge to teach and even to share on social media and so on. It makes experiences better over time when you’re sharing them with someone else. We’ve built another creature that can do this with us, which is kind of cool.”

I think of Winston more and more these strange days. I picture his long elegant face and his long comic book tail. His calm. His unflappable enthusiasm for problem-solving. His reasonability. Statesmanlike. I daydream often of those puppies, too. Is there anything in our shared history more soothing than a roomful of puppies?

There is not.

It turns out that by knowing the dog, we know ourselves. The dog is a mirror.

Logic; knowledge; problem-solving; intentionality; we can often describe the mechanics of how we think, of how we arrived at an answer. We talk easily about how we learn and how we teach. We can even describe it in others.

Many of us—maybe most of us—don’t have the words to describe how we feel. I know I don’t. In all of this, in all the welter of the world and all the things in it, who understands my sadness? Who can parse my joy? Who can reckon my fear or measure my worry? But the dog, any dog—especially your dog—the dog is a certainty in uncertain times, a constant, like gravity or the speed of light.

Because there is something more profound in this than even science has language for, something more powerful and universal. Because at the end of every study, at the end of every day, what the dog really chooses is us .

So. As I said. A love story.

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)

Jeff MacGregor | | READ MORE

Jeff MacGregor is the award-winning Writer-at-Large for Smithsonian . He has written for the New York Times , Sports Illustrated , Esquire , and many others, and is the author of the acclaimed book Sunday Money . Photo by Olya Evanitsky.

clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

Thinking about how dogs think

Back in 2002, when Alexandra Horowitz was working toward her PhD at the University of California at San Diego, she believed that dogs were a worthy thing to study. But her dissertation committee, which favored apes and monkeys, needed convincing.

“They were primate people,” she said. “They all studied nonhuman primates or human primates, and that’s where it was thought that the interesting cognitive work was going to happen. Trying to show them that there would be something interesting with dogs — that was a challenge.”

Oh, how things can change in just two decades, especially in a nation that includes about 90 million dogs among its residents — everything from beloved pets to working dogs doing all kinds of tasks, from sniffing out drugs in airports to assisting blind people with crossing a street. Today, Horowitz is a senior research fellow at Barnard College in New York City, where her specialty is dog cognition: understanding how dogs think, including the mental processes that go into tasks such as learning, problem-solving and communication. Dog cognition is now a widely respected field, a growing specialty branch of the more general animal-cognition research that has existed since the early 20th century.

“This field, and animal cognition, really, is all within our lifetimes,” Horowitz said. “It’s not as if nobody ever looked at dogs, but they weren’t looking at their minds.”

Looking at dogs’ minds, so far, has revealed quite a few insights. The Canine Cognition Center at Yale University, using a game where humans offer dogs pointing and looking cues to spot where treats are hidden, showed that dogs can follow our thinking even without verbal commands. The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany figured out that dogs are smart about getting what they want — they will eat forbidden food more frequently if humans can’t see them. Researchers from Austria, Israel and Britain determined that seeing a caregiver, versus a stranger, activated dogs’ brain regions of emotion and attachment much as it does in the human mother-child bond. Other European researchers showed that negative-reinforcement training (like jerking on a leash) causes lingering emotional changes and makes the dog less optimistic overall.

Read more stories of dogs, humans and the relationship they share

Some dog owners hear about this type of research and think: “They did a whole study to figure out that my dog looks where I point? I could have told you that.” But the studies aren’t just about what a dog is doing. They’re indicating areas to research so that we can better understand why and how the dog is doing it — in other words, what’s happening inside the dog’s mind.

“Maybe they’re not looking at your finger at all. Maybe they’re paying attention to your face and not to your hand,” said Federico Rossano, whose team at the University of California at San Diego is trying to determine whether dogs can translate their thoughts into words that humans can understand through a language device. “A lot of this becomes interesting in terms of how you can train them better.”

An evolving area of research

Right now, with no organizing body in the field, it’s hard to say exactly how many people are doing dog-cognition research. You can count on two hands the number of dedicated university spaces led by professors with graduate students and funding grants. When the leaders from those places get together once a year, it’s usually at someone’s home.

But researchers at universities doing studies on dogs? There are now many dozens of those, and there’s no lack of students wanting to at least dabble in the work.

“The thing that gets my students all abuzz is that people always want to know whether their dog loves them back,” said Ellen Furlong, associate professor of psychology at Illinois Wesleyan University and leader of its Dog Scientists Group.

Every semester, on the first day, she asks students if their dogs are happy. It’s her way of helping them understand why the study of dog cognition is important.

“They’re always kind of offended — ‘O f course my dog is happy. I love my dog,’ ” she said. “But then you dig a little bit and push them and say: ‘Your dog’s life is different from your life. You get to decide when your dog gets to eat and play and go outside. You decide everything about your dog’s life, but your dog isn’t human. They have different wants and needs than you do.’ They have a semester-long assignment where they have to consider how their work on cognition can help to design some enrichment activities to improve the dogs’ lives.”

The topics that dog-cognition researchers focus on today often are chosen based on personal interests. While Furlong is most curious about ethics, welfare and how humans can meet dogs’ psychological needs, Horowitz is focusing her research on what dogs understand through smell. At the Duke Canine Cognition Center in North Carolina, Brian Hare is trying to determine — when a dog is still a puppy — whether the way a dog thinks might make her a good candidate for different jobs as an adult.

“We’re saying, ‘Here are some cognitive abilities that are critical for training for these jobs,’ ” Hare said. “It’s a little bit like talking about personality, but we’re talking about your cognitive personality, in a way. Maybe you have a really good memory for space, or maybe you’re good at understanding human gestures. The question is whether we can identify some of these dogs really early, in the first two to three months of life, who will do well in these programs.”

How the research is done

One example of dog cognition research with a potential training application is a study that Horowitz did on nose work — an activity that lets dogs use their natural abilities with scents to find everything from a treat hidden under a cone to marijuana in somebody’s suitcase.

Horowitz and her team showed the dogs three buckets and taught them that one of the buckets always had a treat under it, and one did not. Then she measured how quickly the dogs went to the “ambiguous bucket” in the middle.

The dogs then attended nose-work classes. These types of advanced classes are widely available at the same types of schools that teach basic obedience. In the nose-work classes, dogs are encouraged and trained to use their noses to search for and find treats or favorite toys that are hidden under boxes or cones, inside suitcases or in other places.

After a few weeks of nose-work classes, Horowitz repeated the bucket test.

“What we found was the dogs in the nose-work class got faster at approaching ambiguous stimulus,” she said, adding that the results suggest that for some dogs, taking nose-work classes could help them feel more optimistic. “The group that had nose work changed their behavior afterward, so I have to say it’s something about the nose work. I don’t know exactly what it was, but if the effect is profound and we keep seeing it, we would go in and try to see what it was that made it useful for the subjects.”

Hare is widely credited with having jump-started America’s dog-cognition research field. In the late 1990s as an undergraduate, he was doing research with chimpanzees when he realized they couldn’t do something that his dogs could do: follow a human’s pointing gesture to find food. Chimpanzees are the closest animal relatives humans have, and dogs could do something they couldn’t. Researchers suddenly wanted to know why dogs could understand something that chimpanzees could not.

In his most recent study , published in July, Hare and his team looked at the difference between wolf and dog pups. There had been some debate in the dog-cognition field about where dogs’ unusual abilities to cooperate with humans originate — whether those abilities are biological or taught. So the team gave a battery of temperament and cognition tests to dog and wolf puppies that were 5 weeks to 18 weeks old. The pups of both species were given the chance to approach familiar and unfamiliar humans to retrieve food; to follow a human’s pointing gesture to find food; to make eye contact with humans, and more. The team found that even at such a young age, the dog pups were more attracted to humans, read the human gestures more skillfully, and made more eye contact with humans than the wolf pups did.

The conclusion? The way that humans domesticated dogs actually altered the dogs’ developmental pathways, meaning their abilities to cooperate with us today are biological — a research result that is likely to have many practical implications.

“It’s highly inheritable, and it’s potentially manipulatable through breeding,” Hare said, adding that dogs might be bred to specialize in certain types of thinking. The finding opens up the idea of studying dogs in ways that could make deep-pocketed entities like the U.S. government want to fund more dog-cognition research, Hare said.

By way of example, he talked about dogs he has worked with for the U.S. Marine Corps, compared with dogs he has worked with for Canine Companions for Independence in California. The Marines needed dogs in places like Afghanistan to help sniff out incendiary devices, while the companions agency needed dogs that were good at helping people with disabilities.

Just looking at both types of purpose-bred dogs, most people would think they’re the same — to the naked eye, they all look like Labrador retrievers, and on paper, they would all be considered Labrador retrievers. But behaviorally and cognitively, because of their breeding for specific program purposes, Hare said, they were different in many ways.

Hare devised a test that could tell them apart in two or three minutes. It’s a test that’s intentionally impossible for the dog to solve — what Star Trek fans would recognize as the Kobayashi Maru. In Hare’s version, the dog was at first able to get a reward from inside a container whose lid was loosely secured and easy to dislodge; then, the reward was placed inside the same container with the lid locked and unable to be opened. Just as Starfleet was trying to figure out what a captain’s character would lead him to do in a no-win situation, Hare’s team was watching whether the dog kept trying to solve the test indefinitely, or looked to a human for help.

“What we found is that the dogs that ask for help are fantastic at the assistance-dog training, and the dogs that persevere and try to solve the problem no matter what are ideal for the detector training,” Hare said. “It’s not testing to see which dog is smart or dumb. What we’ve been able to show is that some of these measures tell you what jobs these dogs would be good at.”

What comes next in the field of dog-cognition research is probably a bit more of everything. Some researchers are following their interests, while others are following the research grants. Those grants can come from a wide array of sources, including the government trying to help soldiers with post-traumatic stress disorder, shelters trying to rehome animals and neuroscience institutes looking for insights across species.

“It’s a really exciting moment,” Hare said. “I think we can continue on with individual researchers pursuing fun, interesting things — the students and the universities love it — but most successful academic endeavors have two parts. Being intellectual is wonderful, but that kind of research tends to struggle with funding. Academic endeavors with practical application tend to be incredibly well funded, and then the field grows.

“If you can have both of those things, then it will grow, and it will grow phenomenally,” he added. “If it’s just, ‘We’re going to do this because people love dogs,’ that’ll be fun, but it will stay small like it is now.”

The scholar’s best friend: research trends in dog cognitive and behavioral studies

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 21 November 2020

- Volume 24 , pages 541–553, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Massimo Aria 1 ,

- Alessandra Alterisio 2 ,

- Anna Scandurra 2 ,

- Claudia Pinelli 3 &

- Biagio D’Aniello ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1176-946X 2

12k Accesses

60 Citations

69 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In recent decades, cognitive and behavioral knowledge in dogs seems to have developed considerably, as deduced from the published peer-reviewed articles. However, to date, the worldwide trend of scientific research on dog cognition and behavior has never been explored using a bibliometric approach, while the evaluation of scientific research has increasingly become important in recent years. In this review, we compared the publication trend of the articles in the last 34 years on dogs’ cognitive and behavioral science with those in the general category “Behavioral Science”. We found that, after 2005, there has been a sharp increase in scientific publications on dogs. Therefore, the year 2005 has been used as “starting point” to perform an in-depth bibliometric analysis of the scientific activity in dog cognitive and behavioral studies. The period between 2006 and 2018 is taken as the study period, and a backward analysis was also carried out. The data analysis was performed using “bibliometrix”, a new R-tool used for comprehensive science mapping analysis. We analyzed all information related to sources, countries, affiliations, co-occurrence network, thematic maps, collaboration network, and world map. The results scientifically support the common perception that dogs are attracting the interest of scholars much more now than before and more than the general trend in cognitive and behavioral studies. Both, the changes in research themes and new research themes, contributed to the increase in the scientific production on the cognitive and behavioral aspects of dogs. Our investigation may benefit the researchers interested in the field of cognitive and behavioral science in dogs, thus favoring future research work and promoting interdisciplinary collaborations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Music in business and management studies: a systematic literature review and research agenda

Trends and Developments in Mindfulness Research over 55 Years: A Bibliometric Analysis of Publications Indexed in Web of Science

Dog Breeds and Their Behavior

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The domestication of wolves was probably the first human successful attempt aimed to control an animal. After the first stage, in which primitive dogs were domesticated from their wild ancestors—the wolves, dogs were artificially selected resulting into the modern breeds, based on different specialization and morphology (Wayne and Ostrander 2007 ). However, several aspects of this history remain unclear, despite scientific efforts in studying dog evolution. Under dispute is the place of the domestication process of dogs—from Europe or southern East Asia—as uncertainly lies in the divergence between wolves and dogs (Thalmann et al. 2013 ; Wang et al. 2016 ). Many doubts also surround the question of how domestication of dogs began and how this process has impacted cognition and behavior in dogs (Hare et al. 2002 ; Udell and Wynne 2008 ; Wynne et al. 2008 ; Topál et al. 2009a ). Probably, the secret of such a long duration and effective cooperation with humans are dogs’ advanced social skills, which allowed them to exchange communicative signals effectively with the human (Miklósi 2009 ; D’Aniello and Scandurra 2016 ; D’Aniello et al. 2017 ; Scandurra et al. 2017 , 2018 ).

In history, dogs were mostly employed for utility, whereby the term “man’s best friend” originated in the eighteenth century (see Miklósi and Topál 2013 ). They are now increasingly involved in different working and sporting activities, and their presence in our homes as pets is also in a growing trend in many countries (see, for example, Murray et al. 2015 ). Pet dogs could promote the welfare of the human family they live with, whereas working dogs are an integral part of social functioning. Several studies demonstrated that keeping dogs has a positive effect on our physical and mental health (Levine et al. 2013 ; Ownby et al. 2002 ; Raina et al. 1999 ; Kramer et al. 2019 ). Although this so-called “pet effect” (Allen 2003 ) received some criticism, noting that some papers reported null or also negative effects on health and happiness of pet owners (see Herzog 2011 for a review), it contributed to the flurry of research on dogs.

Altogether, dogs have become an important social phenomenon attracting scientific interest (Morell 2009 ). There are different reasons why canine research is advantageous beyond the easy access to the subjects for experimental purposes. They show many similarities with humans (Scandurra et al. 2020 ) and, therefore, can be used as a model for human studies. Indeed, there are functional parallels in a range of behavioral features, which are not shared with the closest human relatives, the great apes (Topál et al. 2009b ). The success of dogs as behavioral models also relies on their origin from ancestors with high social behavior, the adaptiveness in living in the anthropogenic niches and the socialization with humans during ontogeny (Kubinyi et al. 2009 ). Moreover, dogs have also been used as a model for comparative and translational neuroscience, cancer and cognitive decline, such as in Alzheimer’s disease in humans (Head et al. 2000 ).

Bibliometric research focusing specifically on the dog’s personality or temperament showed about 50 papers in the database between 1934 and 2004 (Jones and Gosling 2005 ). A comprehensive study by Bensky et al. ( 2013 ) aimed at identifying the major trends in the literature related to the areas of cognitive research on dogs, detected an increase in the studies over the 15 years before the date of the review. However, a worldwide trend of scientific research on dog cognition and behavior has never been explored to date using a bibliometric approach (Chen 2003 ), while the evaluation of scientific research has increasingly become important in recent years. Bibliometric analysis is a useful tool to measure the output of scientific research, using specific indicators to obtain information about the research trends in different fields (De Battisti and Salini 2013 ; Wallin 2005 ).

There are pure cognitive studies, which analyze the brain functioning through brain imaging (e.g., fMRI studies), without taking into account the behavioral responses. However, most of the papers dealing with cognition also include behavioral outcomes. Indeed, brain imaging studies often analyze brain functioning, while the experimental subjects are performing various behavioral tasks. Moreover, many studies provide data for the understanding how stimuli are processed (i.e., cognition) by studying behavioral responses. Therefore, it is not so common to find pure cognitive or behavioral studies, whereby, in this paper, we have considered all studies dealing with both cognition and/or behavior.

Since there is evidence of a growing trend in scientific production (Fanelli and Larivière 2016 ), the first goal of the present paper was to verify whether the dog cognitive and behavioral studies show a growing trend exceeding those of cognitive and behavioral sciences in general. To this scope, we have provided a comparison between the trend in the literature on dogs and that of the whole collection of studies in the subject category “Behavioral Sciences” from 1985 (i.e., the year of starting electronic access to Web of Science database) to 2018. It was verified that peer-reviewed publications on dog cognitive and behavioral studies showed a steeper growth curve with respect to that of the subject category “Behavioral Sciences” starting from 2005. Therefore, this year was chosen as a “starting point” for a “recent analysis” until 2018, including 13 years. To further emphasize the more current changes in the scientific production related to the cognitive and behavioral studies on dogs, we compared the “recent analysis” with an “earlier analysis”. The latter covered in the backward direction an equivalent number of years to the “recent analysis” from the “starting point”.

Our second goal was to understand whether the growth of scientific production in dog cognition and behavior was simply related to an increased research effort in the same research themes or changes in research themes and the contribution of new research themes to this trend.

The further aim was to provide a bibliometric analysis related to sources, countries, affiliations, co-occurrence network, thematic maps, collaboration network, and world maps of the scientific activity related to the cognitive and behavioral studies on dogs. We also attempted to identify the most frequent and impactful journals, countries, research institutes, and their relationship at social and conceptual levels.

Overall the information reported in this study could be useful to the researchers in locating the topics that need more scientific efforts, giving information to help further develop the already thriving growing field of dog cognition and behavior, thus fostering future interdisciplinary collaborations.

We used bibliometrix, a new R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017 ), which provides various options for importing bibliographic data from scientific databases and performing bibliometrics analysis related to different items. We employed bibliometrix to analyze the sources, countries, and affiliations. It allowed us to define the structure of the topic at the conceptual level based on the co-occurrence network and thematic maps and social structure as gathered by collaboration network and world maps.

Selection strategy

Our investigation followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines, illustrating the outcomes of the literature searches and article selection process (Liberati et al. 2009 ). PRISMA consists of a checklist describing the protocol adopted for selecting the collection of articles used in a systematic literature review. It is used to ensure that the selection process is replicable and transparent. We performed a computerized bibliometric analysis from January 1985 to December 2018 for articles retrieved from the Web of Science (WoS) database, which is now maintained by Clarivate Analytics, and also retrieved articles from the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI expanded) and the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI). Data were collected in January 2020.

To identify all publications related to this field, we defined the following query: (((TS = (((dog OR dogs) AND *cogniti*) OR (canis AND familiaris AND *cogniti*))) OR (TS = ((( dog OR dogs) AND communicat*) OR (canis AND familiaris AND communicat*))) OR (TS = ((( dog OR dogs) AND behav*) OR (canis AND familiaris AND behav*))))). TS stands for topic, that is, the search of the mentioned words in the title, abstract, and keyword lists. This query was formulated after some exploratory trials in which, after using the word behav* and cogniti*, we noted that some of the publications in our personal database related to dogs’ communication did not appear. Thus, for a more comprehensive research, we also added the word communicat*. In our search, we selected original articles in the English language, including experiments (i.e., review articles and proceedings were excluded).

The information about the retrieved articles by WoS in Bib TeX format was exported into Microsoft Excel 2017. The selection involved two selectors, which reached a satisfactory agreement level (Cohen’s K = 0.91). The choices that did not match were resolved involving a third independent researcher and the final decision was taken by the concensus among researchers (Cuccurullo et al. 2016 ).

The inclusion criteria concerning cognitive and behavioral sciences are reported in Table 1 .

Data loading and converting

Numerous software tools support science mapping analysis; however, many of these do not assist scholars in a complete recommended workflow. The most relevant tools are bibliometrix (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017 ), CitNetExplorer (van Eck and Waltman 2014 ), VOSviewer (van Eck and Waltman 2010 ), SciMAT (Cobo et al. 2012 ), and CiteSpace (Chen 2006 ). Starting from our final collection, we loaded the data (i.e., the selected papers matching the inclusion criteria, including all their metadata) and converted it into R data frame using bibliometrix (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017 ) since it contains a more extensive set of techniques and it is suitable for practitioners through Biblioshiny (Moral-Muñoz et al. 2020 ).

To investigate the interest in dog’s cognitive and behavioral sciences, the annual trend of publications from 1985 to 2018 was compared with the whole literature in the field of cognitive and behavioral studies published in the subject category “Behavioral Science,” since most of the papers related to cognition and behavior fall in this subject category. Indeed, it includes 53 journals, some of them with the main focus on cognition, such as “ Animal Cognition ” and other focusing mainly on behavior, such as “ Animal Behavior ”. However, all journals in the subject category “Behavioral Science” tend to accept studies on cognition and/or behavior.

From 2005, the studies on dogs diverged upward from the general growing trend of the papers on cognitive and behavioral studies published in the subject category “Behavioral Science” (see results). Thus, we chose to use this point to perform the following separate analysis on dogs a posteriori. A “recent analysis”, including the last 13 years (2006–2018), was used to underline emerging aspects, and an “earlier analysis”, counting the same number of years (1993–2005), was used for comparative purposes. In this way, we were able to compare the period in which there was an increase in the scientific production on dogs exceeding the trend of studies in the subject category “Behavioral Sciences” and an equivalent number of years in which the growing trend of dogs’ cognitive and behavioral studies paralleled that of behavioral sciences. This choice allowed us to test whether the exceeding trend of dog studies was simply due to an increased effort in the same topics or new topics contributed to this increase.

We analyzed the article collection using different aggregation levels. Regarding journals, bibliometrix provides many indicators, such as the number of publications, h-index (Hirsch 2005 ), g-index (Egghe 2006 ), m-index (von Bohlen und Halbach 2011 ), and the total number of citations. Thus, we reduced the variables by applying a principal component analysis with orthomax rotation, through a statistical tool for Excel (XLSTAT 2019, Addinsoft Inc.).

Co-occurrence network, collaboration network, thematic maps, and world maps are also provided. A network is a graphical representation of item co-occurrences in a set of documents. In a co-occurrence network, the items consist of terms extracted from the article keyword lists, from the titles, or from the abstracts; while in a collaboration network, the items consist of the co-authors, the author’s affiliations, or the author’s countries. A thematic map is a Cartesian representation of the term clusters identified performing a cluster analysis on a co-occurrence network. It allows for easier interpretation of the research themes developed in a framework. Finally, a world map is a geographical representation of the collaboration network of an author’s country. The analyses were based on KeyWords Plus, which are the words or phrases that frequently appear in the titles of the references cited in an article but do not appear in the title of the article itself. They are extracted from the papers using a statistical algorithm, based on the cited references in the article. This process is unique to Clarivate Analytics databases. The algorithm is based on a supervised machine learning approach that automatically assigns a set of keywords, namely, Keyword Plus, from a glossary defined by a team of experts. This approach uses the article’s bibliography to identify the research topics and then label the document with a set of Keyword Plus. The use of the KeyWords Plus offers several advantages over other databases and author’s keyword list, in such a way that the terms are extracted from a standardized glossary, defined for subject categories analyzed. It also covers a larger knowledge base and unbiased concerning the author’s subjectivity when providing keywords for their articles (Zhang et al. 2016 ). Moreover, a comparison between Keywords Plus and Author Keywords performed at the scientific and the document levels yields more Keywords Plus terms than Author Keywords, and it is more descriptive (Zhang et al. 2016 ).

Based on Keywords Plus, we obtained the co-occurrence network, which identifies the relationship between the keywords. Each keyword represents a node, or vertex, of the network, and the edge connecting two nodes is proportional to the number of times two keywords are included in the same keyword list. Stronger is an edge, higher is the relationship between two keywords within a paper (Tijssen and Van Raan 1994 ), thus allowing to provide a graphic visualization of potential relationships among keywords. In the network, it is possible to identify groups of strongly interconnected terms, which represent themes or topics. Although different algorithms exist to identify these groups, this study used the Louvain community detection algorithm (Blondel et al. 2008 ) because it gave the best results when applied to different benchmarks on Community Detection methods (Lancichinetti and Fortunato 2009 ).

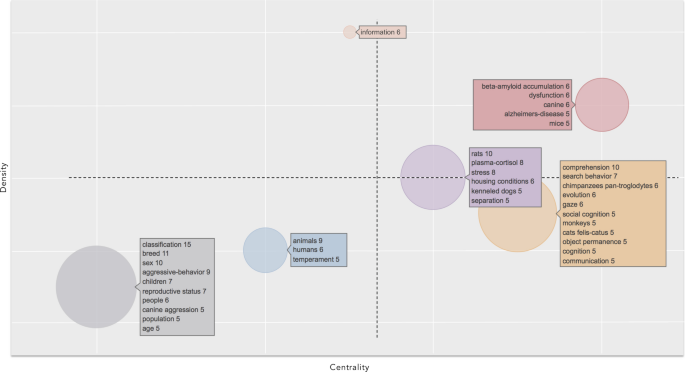

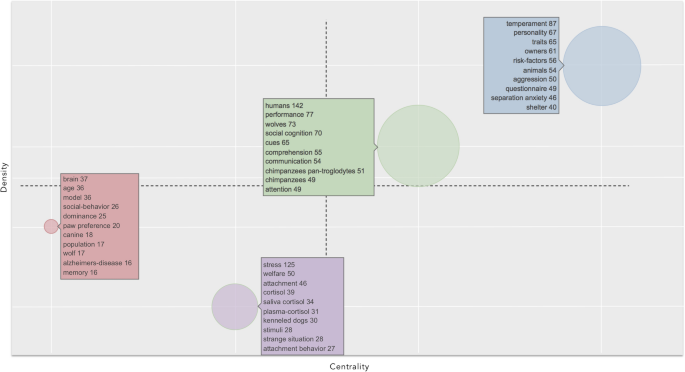

The clusters identified by the co-occurrence network were plotted in a thematic map according to Callon’s centrality and Callon’s density rank values along the two axes (Callon et al. 1991 ).

The X-axis represents the centrality, that is, the degree of interaction of a network cluster in comparison with other clusters appearing in the same graph. It can be read as a measure of the importance of a theme in the development of the research field. The Y-axis symbolizes the density, which measures the internal strength of a cluster network, and it can be assumed as a measure of the theme’s development (Cahlik 2000 ; Cobo et al. 2011 , 2015 ). According to these authors, the graphical representation of themes on the four quadrants in which they are plotted allows identification of the following proprieties: (1) Motor themes (first quadrant): the cluster network is characterized by high centrality and high density, meaning that they are well developed and important for the structuring of a research field; (2) Highly developed and isolated themes (second quadrant): they are characterized by high density and low centrality, meaning that they are of limited importance for the field since they do not share important external links with other themes; (3) Emerging or declining themes (third quadrant): they have low centrality and low density, meaning that they are weakly developed and marginal. The identification of emerging or declining trends of a theme requires a longitudinal analysis, through a thematic evolution (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017 ): splitting the timespan into different timeslices allow to identify the trajectory, whereby a direction toward the top of the map over time identifies an emerging trend while a direction toward the lower left quadrant would identify a declining trend; (4) Basic and transversal themes (fourth quadrant): they are characterized by high centrality and low density, namely, they are important concerning general topics that are transversal to different research areas of the field.

The scientific collaboration analysis was used to identify the social structure of the field, through the application of the social network analysis (Newman 2001 ), applying it at an aggregated level (i.e., countries).

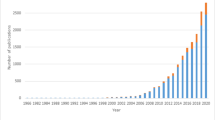

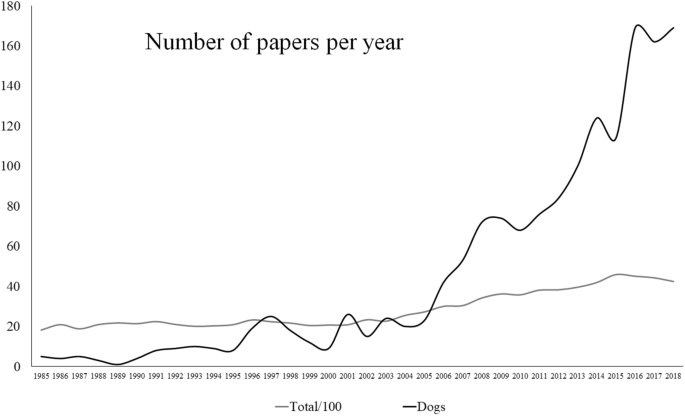

The comparison of the number of publications from selected papers for dogs with the general trend of all papers published in the subject category “Behavioral Science” showed that starting from 2005, there has been a sharp increase in scientific production on dogs (Fig. 1 ).

Comparative view of the annual scientific production related to cognitive studies on dogs (black line) and the trend of publication rate of research in the subject category “Behavioral Sciences” (gray line; for an obvious comparison, the line has been lowered 100 folds). It is evident that increasing trend in research on dogs starts from 2005

Data related to the main information on dogs are reported in Table 2 .

After our selection, 218 papers related to studies on dogs were retrieved in the “earlier analysis” (1993–2005), while they were 1307 in the “recent analysis” (2006–2018). This means that the scientific production on dog cognitive and behavioral studies increased sixfold. A similar finding was also observed for the Keywords Plus, Authors’ Keywords, Authors, Author Appearances, Authors of multi-authored documents, and single-authored documents. However, these data support the view that there is a considerable increase in the researchers working on the cognitive and behavioral aspects of dogs. It also appears that the contribution of a single researcher who co-authored remains almost unchanged, which means that the research effort by each researcher has not generally increased over time.

Sources impact

Dog cognitive and behavioral studies appeared in 34 different sources in “earlier analysis”, while they substantially increased in “recent analysis”, totaling to 85. The principal component analysis (PCA), carried out on the number of publications, h-index, g-index, m-index, and the total number of citations, highlighted a single principal component explaining 98.56% of the variability (Eigenvalue = 4.928, χ 2 = 584.479, P < 0.001), with KMO = 0.786 ensuring the sampling adequacy in the “earlier analysis”. In the “recent analysis”, the PCA detected a single component explaining most of the variability (93.709%, Eigenvalue = 4.685, χ 2 = 875.361, P < 0.001, KMO = 0.838).

The highest score for the cognitive and behavioral sciences of dogs was the Applied Animal Behavior Science , both in “earlier analysis” and “recent analysis”. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association , occupying the second place in “earlier analysis”, was less utilized in “recent analysis”, not appearing in the first ten sources anymore. A lowering in score from “earlier analysis” to “recent analysis” was also observed for the third journal in the list, which was the Journal of Comparative Psychology . In “recent analysis”, Animal Cognition and Journal of Veterinary Behavior-Clinical Applications and Research both showed an increase in the score, occupying the second and third place, respectively. It is noteworthy that PLoS One acquired a high score in dog cognitive and behavioral studies in “recent analysis”. Indeed, it was not present in “earlier analysis” since it was launched in 2006, which coincides with the start of our “earlier analysis” analysis. Similar reasoning could be applied for Scientific Reports , which was launched in 2011 and is in the first ten sources in our collection related to the “recent analysis”. Full data for the sources are reported in Online Resources 1 and 2.

Country productivity and affiliations

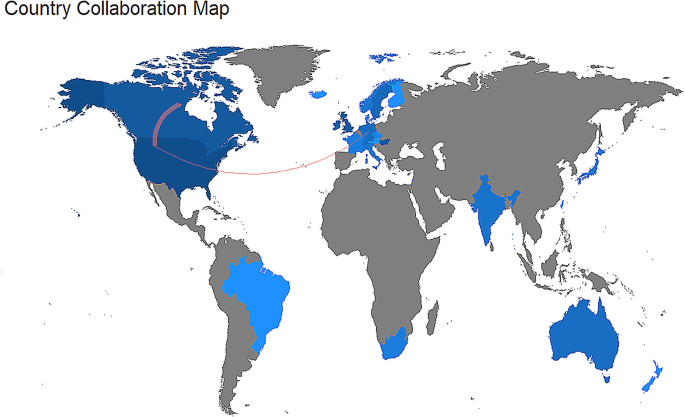

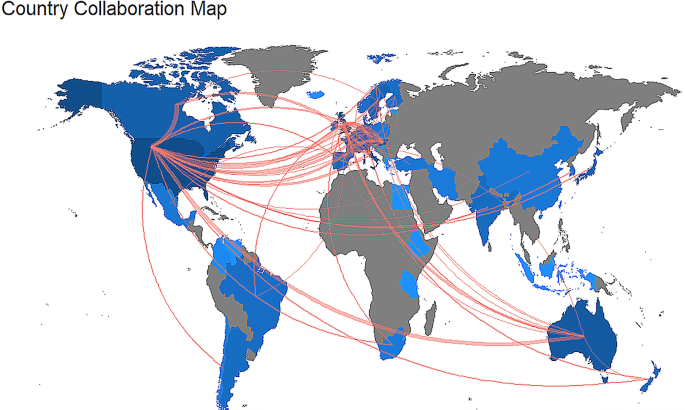

According to our collection of the metadata, in the “earlier analysis”, 22 countries contributed to dog cognitive and behavioral studies, whereas in the “recent analysis”, they have almost been doubled (42).

Considering the number of publications related to corresponding authors, the leading countries were the USA, the UK, and Hungary in the “earlier analysis”, and these were also among the most productive in “recent analysis”. Ireland appeared as the fifth most productive country in “earlier analysis” but was much less involved in dog cognitive and behavioral studies in “recent analysis”, where it ranked at the 24th position. A slightly less engagement on the part of the Netherlands affected its ranking, pushing it down from the ten to the fifteenth position. On the contrary, Italy, contributed less in “earlier analysis”, while it appeared more productive in “recent analysis”, ranking in the third position. A similar observation holds for Austria, which was not listed in “earlier analysis”, but appeared in the first ten most productive countries in the “recent analysis”. Japan was not in the top ten contributing countries in “earlier analysis” but was indeed listed in “recent analysis”. However, this country has only earned two positions, thus maintaining its almost unchanged status in terms of its contribution. The whole data of countries’ productivity are given in Online Resources 3 and 4.

Concerning the affiliations, the Eötvös Loránd University of Hungary provided the highest contribution to the development of the dog cognitive and behavioral sciences in the “earlier analysis”, followed by the University of Toronto and the Utrecht University (the Netherlands). This ranking substantially changed in the “recent analysis”. Besides Eötvös Loránd University of Hungary, which has always been the major contributor to developing dog cognitive and behavioral sciences, all affiliations in the top ten were new, with the University of Vienna and the University of Milan occupying the second and third place, respectively, in the list. The list of the most productive affiliations can be found in Online Resources 5 and 6.

Conceptual structure