Volume 27, Number 6—June 2021

Perspective

Reflections on 40 years of aids.

Cite This Article

June 2021 marks the 40th anniversary of the first description of AIDS. On the 30th anniversary, we defined priorities as improving use of existing interventions, clarifying optimal use of HIV testing and antiretroviral therapy for prevention and treatment, continuing research, and ensuring sustainability of the response. Despite scientific and programmatic progress, the end of AIDS is not in sight. Other major epidemics over the past decade have included Ebola, arbovirus infections, and coronavirus disease (COVID-19). A benchmark against which to compare other global interventions is the HIV/AIDS response in terms of funding, coordination, and solidarity. Lessons from Ebola and HIV/AIDS are pertinent to the COVID-19 response. The fifth decade of AIDS will have to position HIV/AIDS in the context of enhanced preparedness and capacity to respond to other potential pandemics and transnational health threats.

“When the history of AIDS and the global response is written, our most precious contribution may well be that, at a time of plague, we did not flee, we did not hide, we did not separate ourselves.”

—Jonathan Mann, Founding Director of Project SIDA and the World Health Organization Global Programme on AIDS, 1998

Forty years ago, on June 5, 1981, the Centers for Disease Control’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report described 5 cases of Pneumocystis pneumonia in gay men ( 1 ). That report heralded the HIV/AIDS pandemic, which has resulted in over 75 million HIV infections and 32 million deaths. In 2011, we reviewed 30 years of AIDS and commented that the HIV/AIDS response would be a benchmark against which responses to other health threats would be compared ( 2 ). After 40 years of AIDS, we present our personal reflections on scientific and global health evolution over the fourth decade of AIDS in a world that has recently suffered other major epidemics. We focus on biomedical advances because these have had the greatest effect on HIV transmission and disease; advances in structural and behavioral interventions are reviewed in the CDC Compendium of Evidence-Based Interventions and Best Practices for HIV Prevention ( 3 ).

After the initial MMWR report was published, it took 2–3 years for the cause of AIDS, the novel retrovirus designated HIV, to be identified ( 4 , 5 ), and many more years to uncover its simian origin ( 6 ). Because of the asymptomatic spread of HIV, the long incubation period before disease, and transmission through sex and blood, millions of persons around the world, including several hundred thousand in the United States, were infected by the time the first AIDS cases were reported. The epidemiology and natural history of HIV infection, combining elements of acute and chronic diseases, ensured a diverse and long-lasting pandemic.

The history of HIV/AIDS and the struggle to contain it have seen the best and worst of human nature. Frequent examples of discrimination and exclusion are contrasted by leadership, illustrated by community activists ( 7 ), Jonathan Mann molding the first global response ( 8 ), Kofi Annan rallying the United Nations behind the search for a global fund ( 9 ), and President George W. Bush committing United States generosity to a war on HIV/AIDS of uncertain duration ( 10 ). Despite continued instances of injustice, the story has overall been a positive one, providing lessons for how to respond to other epidemic and pandemic threats.

Evolving Epidemiology

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimates that in 2019, 38 million persons worldwide were living with HIV, 1.7 million became newly infected, and 690,000 died with HIV disease ( 11 ). Compared with 2010 estimates, overall HIV incidence in 2019 decreased by 23% and mortality by 37%. However, age stratification shows that new infections have decreased by 52% among children but by only 13% among adults. With reduced mortality rates yet continued HIV incidence and population growth, the overall number of persons living with HIV was 24% greater in 2019 than in 2010.

Global summaries hide regional differences. The epicenter of the pandemic remains in East and southern Africa, which account for 54% of all HIV-infected persons and 43% of incident HIV infections and deaths ( 11 ). High prevalence of HIV-infected persons with unsuppressed viremia predicts high incidence and maintenance of community infection, an observation that applies to regions and countries, as well as specific populations such as men who have sex with men (MSM).

The next greatest HIV burden is in the Asia and Pacific region, where the population is vastly greater than that of East and southern Africa but there are 3.5 times fewer HIV-infected persons ( 11 ). Despite overall prevention progress, HIV incidence has not declined equally everywhere; little success has been seen in eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia.

Ever clearer is the global burden of HIV in key populations: MSM, transgender persons, people who inject drugs, sex workers and their clients, and incarcerated persons. In 2019, an estimated 62% of all new HIV infections were in members of those key populations ( 11 ). In 7 of the 8 UNAIDS regions, key populations accounted for 60%–99% of incident HIV infections; only in East and southern Africa, where the proportion was 28%, were new infections predominant in general populations ( 11 ).

Among high-income nations, the most heavily affected country is still the United States. In 2018, a total of 37,881 HIV infections were newly reported, with regional differences ( 12 ). In the South, the rate of new infections was more than twice that for the Midwest, where the rate was the lowest. Major disparities by race/ethnicity persist; the rate among Black/African American persons is 2 times that among Hispanic and 8 times that among White persons. Also associated with higher rates are factors indicating social deprivation and poverty, even allowing for racial and ethnic disparities. Among new HIV infections, 70% resulted from male-to-male sex. A cause for concern is potential overlap between the HIV/AIDS and opioid epidemics through increased drug injection and needle sharing, which has resulted in explosive HIV outbreaks ( 13 ).

Evolving Science and Program

In our 2011 commentary ( 2 ), we considered the following as priorities: improving use of existing interventions, defining how best to use HIV testing and antiretroviral therapy (ART) for prevention as well as treatment, continuing the quest for new knowledge and interventions, and ensuring sustainability of the global response. By and large, progress has been made on all fronts.

After the CAPRISA 004 trial of precoital and postcoital use of tenofovir gel was published in 2010 ( 14 ), the Ring ( 15 ) and Aspire ( 16 ) studies (randomized, placebo-controlled trials in South Africa) examined the protective efficacy of a self-inserted vaginal ring impregnated with slow-release dapivirine, a nonnucleoside reverse transcription inhibitor. The overall efficacy rates for reducing HIV incidence were 31% (Ring) and 27% (Aspire); many questions about overall efficacy, adherence, and differences by age remained. This collective experience provided proof of concept for woman-controlled prevention but did not provide the definitive public health solution to high HIV incidence among young women in Africa.

Four pivotal randomized trials ( 17 – 20 ) of oral preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with Truvada (combination of tenofovir and emtricitabine) were pivotal for international licensing of the compound. The relevant trials studied MSM, transgender women having sex with men, and at-risk heterosexual persons. A review of evidence considered another 9 studies, some of tenofovir alone, in different populations including people who inject drugs ( 21 ). The pivotal trials showed reduced HIV incidence (44%–86%) with Truvada use. However, a consistent observation has been a strong association between efficacy and adherence; PrEP is effective, but the drugs need to be taken.

Subsequent research focused on differential tissue penetration of drugs to relevant anatomic sites in men and women and on modes of drug delivery. HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) studies compared the prevention efficacy of the long-acting injectable drug cabotegravir with Truvada in men and transgender women who have sex with men (study 083 [ 22 ]) and in heterosexual women (study 084 [ 23 ]). Interim results showed that cabotegravir, delivered every 8 weeks by injection, was associated with 66% lower incidence than oral Truvada in study 083 and 89% less in study 084. The long half-life of cabotegravir enables intermittent dosing, but waning drug levels over time may become subtherapeutic, thus requiring additional interventions to prevent infection and preclude development of drug resistance.

In its 2016 guidelines, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended public health use of PrEP, as have other national and international regulatory or advisory bodies. However, the enthusiasm engendered by PreP science needs to be tempered by consideration of cost, need for rigorous adherence, rising rates of other sexually transmitted infections and thus need for continued condom use, and contraception for women. Long-acting injectables could be a major advance, but accessibility and logistics for their delivery need to be considered.

Mathematical modeling and ecologic studies suggested that greatly increased delivery of ART could reduce HIV transmission at the community level. The definitive study showing that ART provided prevention benefits was the landmark HPTN 052 study ( 24 ), published in interim form in 2011. This trial among discordant couples found a 96% reduction in HIV transmission among those who started ART early versus those for whom it was deferred. Combined with an influential modeling study ( 25 ) that suggested that regular HIV testing and immediate use of ART could suppress and perhaps ultimately eliminate HIV transmission, the results of HPTN 052 led to studies in East and southern Africa of the so-called test and treat intervention ( 26 – 29 ). These studies were community randomized evaluations of widespread HIV testing and immediate ART compared with standard care; the primary endpoint was HIV incidence. These large, expensive implementation science studies yielded rich information but did not lead to local HIV elimination. Of the 4 studies, 2 showed no significant incidence reduction and the other 2 showed 20%–30% reduction.

One of the reasons for the unexpectedly modest differences in HIV incidence between intervention and control communities in the test and treat study was changing global practice with regard to when to start ART. In 2015, results of the START ( 30 ) and TEMPRANO ( 31 ) trials showed unequivocally that immediate ART, irrespective of CD4+ lymphocyte count, resulted in reduced HIV-associated disease and death, ending more than 2 decades of argument about when to start treatment. WHO rapidly changed global recommendations to immediately start ART, one result of which was erosion of differences between intervention and control communities in the test and treat trials.

Although test and treat did not reduce HIV incidence to the extent hoped for, the accumulated evidence supports the notion of early, universal ART for extending the lives of HIV-positive persons as well as reducing the prevalence of unsuppressed viremia, the driver of HIV transmission. Large observational studies ( 32 ) showed that persons with suppressed viremia do not transmit the virus sexually, leading to the slogan “U = U”—undetectable equals untransmittable. This experience provides a much more compelling argument for active HIV case finding through increased HIV testing and partner notification, to enhance individual and public health through early treatment.

Although none of the approaches described provides a unique solution, the combination of widespread HIV testing, early ART for those infected, and PrEP for those at risk offers opportunity for substantially limiting the epidemic. Such approaches have been associated with reductions in new HIV infections among MSM in London, UK ( 33 ), and in New South Wales, Australia ( 34 ). In the United States, these advances—testing, case finding including through partner notification, universal treatment, PrEP, and rapid molecular investigation of clusters for service provision—have been incorporated into a revised national strategy for HIV elimination ( 35 ).

Progress toward an HIV vaccine remains discouraging. The only report of protective efficacy, published in 2009, has been the RV-144 study in Thailand ( 36 ), which investigated use of a recombinant canarypox vector vaccine (ALVAC-HIV) delivered in 4 monthly priming injections followed by a recombinant glycoprotein 120 subunit vaccine (AIDSVAX B/E) given in 2 additional injections. Reported efficacy was 26%–31%, but statistical and technical interpretation of these results was controversial ( 37 ). In 2016, the HVTN 702 study was launched in South Africa and used the same product as in the Thailand trial but modified for the dominant subtype C. After interim analysis, the study was halted for futility in early 2020 ( 38 ). Other efficacy studies of vaccines based on so-called mosaic immunogens from diverse HIV subtypes are in progress.

There has been great interest in broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV, which some infected persons produce naturally and which might protect against a wide variety of strains. Two international trials of infusions with a broadly neutralizing antibody, VRC01, every 8 weeks showed relative protection against sensitive strains but no significantly reduced HIV incidence overall ( 39 ).

In 2014, UNAIDS launched its 90:90:90 initiative, aiming for 90% of persons with HIV infection to be diagnosed, 90% of those with an HIV diagnosis to receive ART, and 90% of those receiving treatment to show viral suppression by 2020. Globally, the respective proportions in 2019 were 81%, 82%, and 88%, so that an estimated 59% of persons living with HIV were showing viral suppression. Initially, 90:90:90 (with a goal of these numbers being 95s by 2030) was an advocacy proposal rather than an evidence-based initiative, but these targets have become adopted as policy promising “epidemic control,” itself a concept requiring precise definition ( 40 ).

ART scale-up, increased male circumcision, and prevention of mother-to-child transmission have all contributed to encouraging advances in the most heavily affected regions of Africa ( 11 , 41 , 42 ). Successful program implementation and declines in new HIV infections and deaths, combined with scientific progress, have led to a certain complacency that “AIDS is over.” Former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and staff promoted the idea that current tools could abruptly halt the epidemic. We largely agree with the 2018 judgment of the International AIDS Society–Lancet Commission on AIDS: “The HIV/AIDS community made a serious error by pursuing ‘the end of AIDS’ message” ( 43 ). Key populations, hiding in obscurity as well as in plain sight, will probably remain as reservoirs, even with highly performing programs. Experience in East and southern Africa has highlighted the challenge of adequate service provision to youth and men. Stigma and discrimination remain barriers in many parts of the world, and lack of an HIV cure (a priority research area) and vaccine remain scientific obstacles ( 44 ).

Evolving Global Health

The HIV/AIDS pandemic has evolved in parallel with other global health events that necessarily influence how HIV/AIDS is perceived and prioritized. In a 2012 paper, author K.D.C. suggested that global health trends could best be analyzed through the lenses of development, public health, and health security ( 45 ). The fourth decade of AIDS started in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the influenza (H1N1) pandemic and is finishing amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Although substantial progress has been made toward reducing maternal deaths, improving child survival rates, and scaling up programs for HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis, the past decade has seen major disease outbreaks and a consequent focus on health security. Because of its sociodemographic effects, AIDS was portrayed as a security issue in United Nations discussions early in this century. With massive scale-up of treatment and prevention, HIV/AIDS is now perceived as another public health priority rather than a security emergency.

In 2014, Ebola was reported in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, far west of previously recognized outbreaks. The epidemic lasted until mid-2016 and ultimately resulted in 28,646 reported cases and 11,323 deaths ( 46 ). Infections were exported to 3 other countries in Africa, several countries in Europe, and the United States. This health crisis resulted in widespread fear of possible global spread, unparalleled global mobilization of emergency health assistance including use of armed forces of the different high-income countries, and political involvement at the highest levels of governments and the United Nations. Subsequent outbreaks of Ebola have occurred in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), including a large epidemic in conflict-ridden eastern DRC in 2018–2020 that resulted in 3,481 reported cases and 2,299 deaths ( 47 ). Underemphasized aspects of these Ebola epidemics were that cases over the past 6 years represent more than 90% of all cases reported cumulatively since recognition of Ebola in 1976; that vast geographic distances were involved; and that these outbreaks were largely urban, sometimes involving capital and other major cities. Ebola epidemiology has changed from that of an exotic, remote infection in Africa to one capable of causing extensive urban outbreaks threatening global health ( 48 ). Also of note was that field research conducted during the outbreaks under the most difficult conditions showed efficacy of a vaccine and therapeutics, both now considered the standard of care for Ebola ( 49 , 50 ).

Over the past decade, arboviral epidemic activity has been diverse. The epidemics of yellow fever in Angola and the DRC in 2015–2016 were the world’s largest over the past 30 years. A total of 965 cases and 400 deaths were reported, but true numbers were far greater. Over 30 million persons were vaccinated, and shortage of yellow fever vaccine required healthcare providers to resort to the untested practice of fractionating vaccine doses ( 51 ). Huge epidemics of chikungunya and dengue occurred internationally; virus was transmitted to areas previously considered at low risk, such as Europe ( 52 ). In 2015, the Zika epidemic raised global concern when infection with this virus was shown to be associated with microcephaly in infants and with Guillain-Barré syndrome and to be sexually transmissible. The outbreak resulted in at least 3,700 cases of birth defects in the Americas ( 53 ).

In 2005, after the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), WHO revised its International Health Regulations ( 54 ). A key change was authority to declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, a health emergency that could result in international spread or required coordinated action. WHO has implemented this authority only 6 times, 5 of them during the fourth decade of AIDS: for polio (2014), Ebola (2014 and 2019), Zika (2015), and COVID-19 (2019).

Related to health security are the interrelated challenges of global warming, demographic change, and migration. Climate change affects social and environmental determinants of health, such as access to clean air, water, shelter, and arable lands, but also exerts direct health effects. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees characterized 2010–2019 as “a decade of displacement,” during which 100 million persons were forced to flee their homes, many because of conflict such as that in the Middle East. During 2014–2020, some 20,000 migrants crossing the Mediterranean Sea to Europe drowned, and another 12,000 or more were unaccounted for.

Broad themes that have dominated global health discourse include the transition from the era of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs; 2000–2015) to that of the broader Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs; 2015–2030) ( 55 ) and the issue of universal health coverage. Other disease-specific programs require continued support, such as the unfinished efforts to eradicate polio and Guinea worm disease. The MDGs had 3 specific health goals relating to child survival; maternal health; and HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. Only 1 of the 17 SDGs is devoted to health, SDG3, which has 13 targets and 28 indicators. Specifically, SDG3 calls for: “By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases.” Another target and WHO priority is provision of universal health coverage, global access to decent healthcare, and protection against penury from out-of-pocket health expenditures. HIV/AIDS exists in a crowded and complex global health space.

Preparing for the Fifth Decade of AIDS

As the world emerged from the financial crisis a decade ago, there was concern that HIV/AIDS funding might be constrained. Development assistance for health reached $40.6 billion in 2019, an increase of 15% over the amount in 2010 ( 56 ). Approximately half of this assistance goes to HIV/AIDS, especially for treatment, and to newborn, maternal, and child health. Thus, although health security has eclipsed health development and global public health in this fourth decade of AIDS, financial commitments have been largely maintained.

The overall annual spending on HIV/AIDS by low- and middle-income countries is ≈$20.2 billion, of which ≈$9.5 billion represents donor funding. UNAIDS consistently communicates that to meet SDG targets, overall spending on HIV/AIDS needs to increase by ≈40%. Nonetheless, this HIV-specific spending is privileged compared with funding for other high-impact diseases in low-income settings, such as malaria and tuberculosis. AIDS is no longer among the 10 leading causes of death globally and is now widely viewed as a medically manageable disease. HIV/AIDS prioritization and funding may be justified by the youthful groups affected and its lifelong nature, but this view may be increasingly challenged. Expecting the United States to pay indefinitely for most of the world’s HIV/AIDS response is unrealistic. The end of the SDG era in 2030 will probably come with reappraisal of global commitments, including those for global health funding, disease-specific focus, and maintenance of single-disease organizations such as UNAIDS. Over the coming years, HIV/AIDS programs need to show good fiscal management and epidemiologic results, and affected countries need to shoulder an increased share of their disease burdens.

Lessons from HIV/AIDS and Other Epidemics

The most dramatic epidemics in recent time (COVID-19 [ 57 ], Ebola, and HIV/AIDS) involve quite different biological agents and challenges yet also raise common themes and questions. Especially needed are global responses to challenges that transcend national borders. Pathogen emergence is enhanced by globalization, but globalized systems are needed to address an interconnected worldwide emergency. The slogan “no one is safe until everyone is safe” has been heard in relation to COVID-19, but it was said years ago about HIV. And global health needs global funding.

Individual leaders and organizations have performed valiant work on COVID-19, yet countries have isolated themselves in all senses, resulting in global fragmentation. Major powers look inward yet are reluctant to cede space, and the influence of multilateral agencies is limited. WHO was heavily criticized after the Ebola epidemic in West Africa but is constrained by restricted authority, inadequate funding, and unrealistic expectations from member states. Repeated calls for WHO reform are unclear about what is really wanted.

Honesty is required concerning preparedness and surveillance. The Ebola epidemic in West Africa became as severe as it did because the 3 affected countries had been neglected for years and had no functioning surveillance and public health infrastructure. We cannot say that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was completely unexpected; the literature on pandemic threats is voluminous. SARS in 2002–2003 was severe but not widespread; the 2009 influenza (H1N1) pandemic was widespread but not severe. It is hubristic to assume that pathogen severity and spread would always segregate, yet we were not prepared. Preparedness metrics can give false reassurance, witnessed by the lamentable response to COVID-19 in the United States in 2020. “Never again” was the mood after the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, but preparedness just seems too hard and costly. Perhaps true preparedness exists only in the military, where personnel train continuously for wars they hope will never happen.

As a result of technologic advances such as whole-genome sequencing, scientific progress on COVID-19 has been breathtakingly rapid compared with early laboratory research on HIV. We hope to not see a replay of the early history of ART, with scientific advances relating to COVID-19, and specifically vaccines, not being rapidly or equitably accessible everywhere. “Vaccine nationalism” is a new term raising the specter of lower risk groups in high-income countries receiving vaccine before, for example, frontline healthcare workers in low-income settings. Healthcare workers have been disproportionately affected by Ebola and COVID-19, highlighting the need for much greater investment in infection prevention and control in healthcare settings worldwide. Attention and innovation are required to ensure maintenance of HIV and other essential public health services amid other outbreaks such as COVID-19.

Although initially slow, the HIV/AIDS response over the years has been a beacon in global health for respect for individuals and their rights and for health equity. More reflection is required with regard to what the responses to HIV and Ebola have taught us and how they might be relevant to COVID-19 and other future epidemics.

Conclusions

Although great need remains, the past decade has seen scientific and programmatic successes with regard to the HIV/AIDS priorities we defined after 30 years of AIDS. Existing interventions have been scaled up, and new tools such as PrEP and long-lasting drug preparations have been introduced. The roles of HIV testing and ART for treatment and prevention have been clarified, and the need for immediate ART for all HIV-infected persons has been proven. The global HIV/AIDS response has been sustained, financing has been maintained, and the world has kept focus on the SDGs. Mann’s judgment that “we did not separate ourselves” remains justified. We must also accept that political promises of “the end of AIDS” were hyperbole that current epidemiology does not support.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exploited the fault lines of global systems and existing inequalities in a way that HIV did early on. Regrettably, the solidarity that HIV/AIDS engendered has not yet been carried over. In retrospect, the recent epidemics of Ebola in West Africa and DRC were preparation for the COVID-19 pandemic, but follow-through was lacking. The fifth decade of AIDS will take us to the SDG target date and reassessment of global health and development priorities. HIV/AIDS may not be central to global health discourse as it was earlier, but it will remain a yardstick by which to judge commitment and efforts, including, and especially in relation to, health security.

On February 7, 2021, the Ministry of Health of DRC reported a laboratory-confirmed case of Ebola in North Kivu Province, the most heavily affected province during the 2018–2020 outbreak in eastern Congo. The case-patient experienced symptom onset on January 25, 2021, and died in Butembo, a city of ≈1 million persons, on February 4, 2021. She was reportedly linked epidemiologically to an Ebola survivor, and genetic sequencing reportedly showed phylogenetic association with the earlier outbreak rather than a new spillover event. As of February 8, 2021, a total of 118 contacts were being investigated ( https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/ebola/ebola-2021-north-kivu , https://www.who.int/csr/don/10-february-2021-ebola-drc/en ).

Separately, on February 14, 2021, the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Guinea reported an outbreak of Ebola in the subprefecture of Gouécké, Nzérékoré Region, the first report of Ebola in Guinea since the 2014–2016 epidemic. The index case-patient, a nurse, experienced symptoms on January 18, 2021, and died on January 28, 2021. A total of 6 secondary Ebola cases were reported, 1 in a traditional practitioner who cared for the index case-patient and 5 in family members attending her subsequent funeral. Of the 7 case-patients, 5 died. As of February 15, 2021, a total of 192 contacts were being investigated, including in the capital city, Conakry ( https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/ebola/ebola-2021-nzerekore-guinea , https://www.who.int/csr/don/17-february-2021-ebola-gin/en ).

Dr. De Cock retired from CDC in December 2020. He had previously served as founding director of Projet RETRO-CI, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire; director of the CDC Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Surveillance and Epidemiology; director of the WHO Department of HIV/AIDS; founding director of the CDC Center for Global Health; and director, CDC Kenya.

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) . Pneumocystis pneumonia—Los Angeles. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 1981 ; 30 : 250 – 2 . PubMed Google Scholar

- De Cock KM , Jaffe HW , Curran JW . Reflections on 30 years of AIDS. Emerg Infect Dis . 2011 ; 17 : 1044 – 8 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Compendium of evidence-based interventions and best practices for HIV prevention [ cited 2021 Apr 18 ]. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/index.html

- Barré-Sinoussi F , Chermann J-C , Rey F , Nugeyre MT , Chamaret S , Gruest J , et al. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Science . 1983 ; 220 : 868 – 71 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Popovic M , Sarngadharan MG , Read E , Gallo RC . Detection, isolation, and continuous production of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and pre-AIDS. Science . 1984 ; 224 : 497 – 500 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Hahn BH , Shaw GM , De Cock KM , Sharp PM . AIDS as a zoonosis: scientific and public health implications. Science . 2000 ; 287 : 607 – 14 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- France D . How to survive a plague: the inside story of how citizens and science tamed AIDS. New York: Alfred Knopf; 2016 .

- Merson M , Inrig S . The AIDS pandemic. Searching for a global response. 2018 . Cham (Switzerland); Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 25–113.

- Piot P . No time to lose. A life in pursuit of deadly viruses. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.; 2012 . p. 316–34.

- Fauci AS , Eisinger RW . PEPFAR—15 years and counting the lives saved. N Engl J Med . 2018 ; 378 : 314 – 6 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS . UNAIDS data 2020 [ cited 2021 Apr 18 ]. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2020_aids-data-book_en.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV surveillance report, 2018 (Preliminary); vol. 30 [ cited 2021 Mar 14 ]. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html

- Peters PJ , Pontones P , Hoover KW , Patel MR , Galang RR , Shields J , et al. ; Indiana HIV Outbreak Investigation Team . HIV infection linked to injection use of oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014–2015. N Engl J Med . 2016 ; 375 : 229 – 39 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Abdool Karim Q , Abdool Karim SS , Frohlich JA , Grobler AC , Baxter C , Mansoor LE , et al. ; CAPRISA 004 Trial Group . Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science . 2010 ; 329 : 1168 – 74 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Nel A , van Niekerk N , Kapiga S , Bekker L-G , Gama C , Gill K , et al. ; Ring Study Team . Safety and efficacy of a dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV prevention in women. N Engl J Med . 2016 ; 375 : 2133 – 43 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Baeten JM , Palanee-Phillips T , Brown ER , Schwartz K , Soto-Torres LE , Govender V , et al. ; MTN-020–ASPIRE Study Team . Use of a vaginal ring containing dapivirine for HIV-1 prevention in women. N Engl J Med . 2016 ; 375 : 2121 – 32 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Grant RM , Lama JR , Anderson PL , McMahan V , Liu AY , Vargas L , et al. ; iPrEx Study Team . Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med . 2010 ; 363 : 2587 – 99 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Baeten JM , Donnell D , Ndase P , Mugo NR , Campbell JD , Wangisi J , et al. ; Partners PrEP Study Team . Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med . 2012 ; 367 : 399 – 410 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- McCormack S , Dunn DT , Desai M , Dolling DI , Gafos M , Gilson R , et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet . 2016 ; 387 : 53 – 60 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Molina J-M , Capitant C , Spire B , Pialoux G , Cotte L , Charreau I , et al. ; ANRS IPERGAY Study Group . On-demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med . 2015 ; 373 : 2237 – 46 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Pre-exposure prophylaxis of HIV in adults at high risk: Truvada (emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil). Evidence summary. [ESNM78] [ cited 2021 Mar 14 ]. https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/esnm78/chapter/full-evidence-summary

- National Institutes of Health . Long-acting injectable form of HIV prevention outperforms daily pill in NIH study [ cited 2021 Apr 18 ]. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/long-acting-injectable-form-hiv-prevention-outperforms-daily-pill-nih-study

- National Institutes of Health . NIH study finds long-acting injectable drug prevents HIV acquisition in cisgender women [ cited 2021 Apr 18 ]. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-study-finds-long-acting-injectable-drug-prevents-hiv-acquisition-cisgender-women

- Cohen MS , Chen YQ , McCauley M , Gamble T , Hosseinipour MC , Kumarasamy N , et al. ; HPTN 052 Study Team . Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med . 2011 ; 365 : 493 – 505 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Granich RM , Gilks CF , Dye C , De Cock KM , Williams BG . Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet . 2009 ; 373 : 48 – 57 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Iwuji CC , Orne-Gliemann J , Larmarange J , Balestre E , Thiebaut R , Tanser F , et al. ; ANRS 12249 TasP Study Group . Universal test and treat and the HIV epidemic in rural South Africa: a phase 4, open-label, community cluster randomised trial. Lancet HIV . 2018 ; 5 : e116 – 25 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Havlir DV , Balzer LB , Charlebois ED , Clark TD , Kwarisiima D , Ayieko J , et al. HIV testing and treatment with the use of a community health approach in rural Africa. N Engl J Med . 2019 ; 381 : 219 – 29 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Makhema J , Wirth KE , Pretorius Holme M , Gaolathe T , Mmalane M , Kadima E , et al. Universal testing, expanded treatment, and incidence of HIV infection in Botswana. N Engl J Med . 2019 ; 381 : 230 – 42 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Hayes RJ , Donnell D , Floyd S , Mandla N , Bwalya J , Sabapathy K , et al. ; HPTN 071 (PopART) Study Team . HPTN 071 (PopART) Study Team. Effect of universal testing and treatment on HIV incidence—HPTN 071 (PopART). N Engl J Med . 2019 ; 381 : 207 – 18 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Lundgren JD , Babiker AG , Gordin F , Emery S , Grund B , Sharma S , et al. ; INSIGHT START Study Group . Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med . 2015 ; 373 : 795 – 807 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Danel C , Moh R , Gabillard D , Badje A , Le Carrou J , Ouassa T , et al. ; TEMPRANO ANRS 12136 Study Group . TEMPRANO ANRS 12136 Study Group. A trial of early antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med . 2015 ; 373 : 808 – 22 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Rodger AJ , Cambiano V , Bruun T , Vernazza P , Collins S , van Lunzen J , et al. ; PARTNER Study Group . Sexual activity without condoms and risk of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. JAMA . 2016 ; 316 : 171 – 81 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Nwokolo N , Hill A , McOwan A , Pozniak A . Rapidly declining HIV infection in MSM in central London. Lancet HIV . 2017 ; 4 : e482 – 3 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Grulich AE , Guy R , Amin J , Jin F , Selvey C , Holden J , et al. ; Expanded PrEP Implementation in Communities New South Wales (EPIC-NSW) research group . Population-level effectiveness of rapid, targeted, high-coverage roll-out of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men: the EPIC-NSW prospective cohort study. Lancet HIV . 2018 ; 5 : e629 – 37 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Fauci AS , Redfield RR , Sigounas G , Weahkee MD , Giroir BP . Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA . 2019 ; 321 : 844 – 5 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Rerks-Ngarm S , Pitisuttithum P , Nitayaphan S , Kaewkungwal J , Chiu J , Paris R , et al. ; MOPH-TAVEG Investigators . Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. N Engl J Med . 2009 ; 361 : 2209 – 20 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Desrosiers RC . Protection against HIV acquisition in the RV144 trial. J Virol . 2017 ; 91 : e00905 – 17 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- National Institutes of Health . Experimental HIV vaccine regimen ineffective in preventing HIV [ cited 2021 Apr 18 ]. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/news-events/experimental-hiv-vaccine-regimen-ineffective-preventing-hiv

- National Institutes of Health . Antibody infusions prevent acquisition of some HIV strains, NIH studies find [ cited 2021 Apr 18 ]. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/news-events/antibody-infusions-prevent-acquisition-some-hiv-strains-nih-studies-find

- Ghys PD , Williams BG , Over M , Hallett TB , Godfrey-Faussett P . Epidemiological metrics and benchmarks for a transition in the HIV epidemic. PLoS Med . 2018 ; 15 : e1002678 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Grabowski MK , Serwadda DM , Gray RH , Nakigozi G , Kigozi G , Kagaayi J , et al. ; Rakai Health Sciences Program . HIV prevention efforts and incidence of HIV in Uganda. N Engl J Med . 2017 ; 377 : 2154 – 66 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Borgdorff MW , Kwaro D , Obor D , Otieno G , Kamire V , Odongo F , et al. HIV incidence in western Kenya during scale-up of antiretroviral therapy and voluntary medical male circumcision: a population-based cohort analysis. Lancet HIV . 2018 ; 5 : e241 – 9 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Das P , Horton R . Beyond the silos: integrating HIV and global health. Lancet . 2018 ; 392 : 260 – 1 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Eisinger RW , Fauci AS . Ending the HIV/AIDS Pandemic. Emerg Infect Dis . 2018 ; 24 : 413 – 6 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- De Cock KM , Simone PM , Davison V , Slutsker L . The new global health. Emerg Infect Dis . 2013 ; 19 : 1192 – 7 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Lo TQ , Marston BJ , Dahl BA , De Cock KM . Ebola: Anatomy of an Epidemic. Annu Rev Med . 2017 ; 68 : 359 – 70 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- World Health Organization . Ending an Ebola outbreak in a conflict zone [ cited 2021 Apr 18 ]. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/813561c780d44af38c57730418cd96cd

- Arwady MA , Bawo L , Hunter JC , Massaquoi M , Matanock A , Dahn B , et al. Evolution of ebola virus disease from exotic infection to global health priority, Liberia, mid-2014. Emerg Infect Dis . 2015 ; 21 : 578 – 84 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Mulangu S , Dodd LE , Davey RT Jr , Tshiani Mbaya O , Proschan M , Mukadi D , et al. ; PALM Writing Group ; PALM Consortium Study Team . PALM Consortium Study Team. A randomized, controlled trial of Ebola virus disease therapeutics. N Engl J Med . 2019 ; 381 : 2293 – 303 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Henao-Restrepo AM , Camacho A , Longini IM , Watson CH , Edmunds WJ , Egger M , et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of an rVSV-vectored vaccine in preventing Ebola virus disease: final results from the Guinea ring vaccination, open-label, cluster-randomised trial (Ebola Ça Suffit!). Lancet . 2017 ; 389 : 505 – 18 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- World Health Organization . Yellow fever outbreak Angola, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda 2016–2017 [ cited 2021 Mar 14 ]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/yellow-fever/en

- Paixão ES , Teixeira MG , Rodrigues LC . Zika, chikungunya and dengue: the causes and threats of new and re-emerging arboviral diseases. BMJ Glob Health . 2018 ; 3 ( Suppl 1 ): e000530 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Musso D , Ko AI , Baud D . Zika virus infection—after the pandemic. N Engl J Med . 2019 ; 381 : 1444 – 57 . DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- World Health Organization . International Health Regulations (2005). 2nd ed. Geneva: The Organization; 2008 .

- United Nations . The 17 goals [ cited 2021 Apr 18 ]. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . Financing global health 2019 . Tracking health spending in a time of crisis [ cited 2021 Mar 14 ]. http://www.healthdata.org/policy-report/financing-global-health-2019-tracking-health-spending-time-crisis

- World Health Organization . Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19—13 April 2021 [ cited 2021 Apr 27 ]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---13-april-2021

DOI: 10.3201/eid2706.210284

Original Publication Date: April 29, 2021

Table of Contents – Volume 27, Number 6—June 2021

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Kevin M. De Cock, c/o Miriam McNally, 669 Palmetto Ave, Suites H–I, Chico, CA 95926, USA, and PO Box 25705-00603, Lavington, Nairobi, Kenya

Comment submitted successfully, thank you for your feedback.

There was an unexpected error. Message not sent.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Article Citations

Highlight and copy the desired format.

Metric Details

Article views: 9100.

Data is collected weekly and does not include downloads and attachments. View data is from .

What is the Altmetric Attention Score?

The Altmetric Attention Score for a research output provides an indicator of the amount of attention that it has received. The score is derived from an automated algorithm, and represents a weighted count of the amount of attention Altmetric picked up for a research output.

- About Degrees

- A Deeper Look

- Research Blog

Living with HIV: A reflection on the past 25 years

A version of this post originally appeared on Interagency Youth Working Group’s Blog, "Half the World". Reposted with permission.

Greg Louganis is a gold-medal-winning Olympic diver and author. He tested positive for HIV in 1988 and has become a prominent and inspirational activist.

It has been almost 25 years since I was diagnosed with HIV. At the time the only drug we had available for treatment was AZT. The prescription for AZT was two pills every four hours around the clock. It’s a bit of an understatement to say this was not conducive to a good night’s rest while I was in training for a challenge of a lifetime, the Olympics.

Dealing with HIV was, on a daily basis, a physical and emotional challenge. The fear, the shame, the pain were, at times, almost more than I could bear. But then, it’s not really in my makeup to give up.

Ten years after I was diagnosed, I thought I would have to say good-bye to my friends and family. I was wasting away to almost nothing. Alone, I boarded a plane and flew thousands of miles from my home, where I checked into a hospital under an assumed name. To my good fortune, my doctors found the treatment to address the fungal infection in my colon and I recovered! But the next issue to face was how the heck to pay those enormous bills?! I didn’t claim it on my insurance as I was afraid of anyone finding out about my diagnoses.

I also survived the Protease Inhibitors treatment — not an easy ride! But it gave hope to many who were failing on other medications.

Now today, holy moly. I can’t believe I’m here. And the longer I live the more exciting my life becomes. So many new adventures before me and I am looking ahead fearlessly!

While it is comforting to know HIV is no longer necessarily a death sentence, I would be negligent if I did not address prevention. I wouldn’t wish my drug regimen on anyone … the side effects, not to mention the cost. Thankfully, the treatments are MUCH more tolerable and there are choices now.

I have spoken with quite a number of young, newly diagnosed men, and the first questions they are plagued by are “Why?” and “How?” Accidents happen. In the long run, does it really help to let yourself go there? It just “is.”

On a practical note, the one thing my HIV has taught me is the importance of exercise to help me tolerate my meds. I think my workouts are as important as the meds themselves. Also, I alleviate stress in my life; stress kills! I also spend time trying to tweak my thinking, looking at — and accepting — what I can change and what I cannot. It’s simple enough, and it becomes easier the more I practice it!

The fact is I live with a virus called HIV; it is a part of me, like an old friend. At times we challenge each other. But it’s clear to me now that those questions “How?” and “Why?” are irrelevant. They do not support my constitution; they inhibit my growth as a human being.

Though it may be cliché, I actually am thankful to my HIV; it has given me perspective and pushed me to pursue my passions because I don’t know how much time I have left on this earth. I have truly learned to appreciate every day. While I was expecting to be gone within 5 years of my diagnoses, it has now been 25 years and the light of my life has never been brighter. I have someone with whom to share my adventures and amazing opportunities for the future!

I have been incredibly blessed to have had such strong support and understanding as I’ve told the world about my HIV. Yes, I have my haters, but I give as little energy to those people as I possibly can. And I practice choosing words that are supportive to myself and others. I do my best not to participate in gossip and trash talk because I am sure it affects my T-cells. It’s easy to spin in other people’s stories, but it’s also pointless. And, it’s exhausting!

That’s not to say all stress is bad …. I am a bit of an adrenaline junky. Now in my 50s, I’ve taken up trapeze, and next year, I’m looking forward to an incredible scuba diving trip and a sky dive! Awareness is my path. Do the people around me make me feel good? They can stay! Those who seem like a black hole and bring me down, I let them go. It’s been a long road to get here, but now that I’m here, I’ve chosen a joyous and happy life!

No one knows how long we have, so all we can do is be at peace with ourselves and make the most of our opportunities. I never thought I would have such a wonderful impact … to be able to try to make everywhere I go better because I was there … to have a purpose! Actually, don’t ask what my purpose is, because it shifts as events present themselves. But right now, it has to do with living outside of myself and being in service to others.

It’s been 25 long years filled with trials, adventures, lessons and ultimately — at last — love. I love my life so in turn, I love my HIV; it is a part of me but doesn’t define me.

No Responses

More from this series, youth: our best sexual health investment.

Ward Cates, MD, MPH, president emeritus and distinguished scientist at FHI 360, makes a clear case for prioritizing investments in the sexual and reproductive health of the world’s youth.

Moving USAID’s Youth in Development Policy Forward: What’s Next for Sexual and Reproductive Health?

Joy Cunningham, a senior technical officer at FHI 360, explains why a 2012 U.S. Agency for International Development policy is critical to young people’s sexual and reproductive health.

Our use of cookies

Privacy overview.

- Open access

- Published: 20 October 2006

A reflection on HIV/AIDS research after 25 years

- Robert C Gallo 1

Retrovirology volume 3 , Article number: 72 ( 2006 ) Cite this article

57k Accesses

63 Citations

32 Altmetric

Metrics details

Dr. Robert C. Gallo provides a personal reflection on the 25 year history of AIDS.

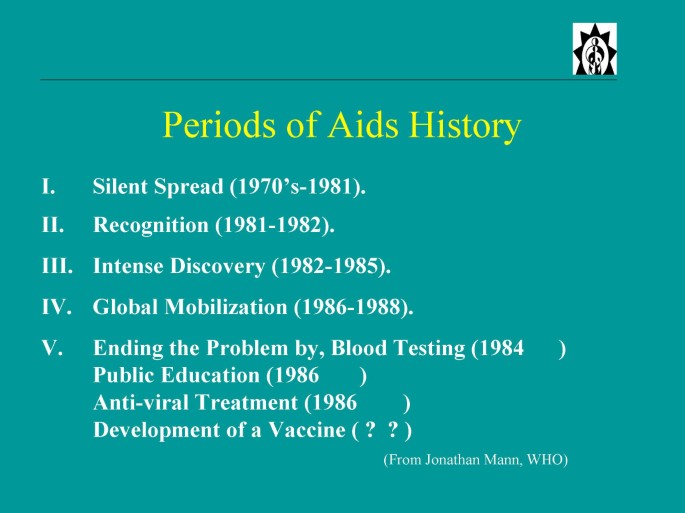

A reflection on the 25 year history of AIDS can begin with no better outline than that provided by the late Jonathan Mann of WHO. A slide he gave to me in the late 1980's divides the history of AIDS into four periods: (see fig. 1 ). Jonathan could not know that the period of silent spread (part 1 of this saga) of HIV actually began years earlier. We now know that, by 1971, the virus had moved to several different regions of the world, but exactly when it came out of Africa is conjectural.

A summary of the five periods of AIDS history as modified after Jonathan Mann.

There has been considerable attention (no less than three papers in Science and Nature over the past few years from B. Hahn and her colleagues) that the natural reservoir for HIV-1 is a particular subspecies of chimp [ 1 – 3 ]. The primate-to-man origin of HIV was suspected almost from the beginning, albeit without knowing which primate. The reasons were three fold: 1) the early evidence that HIV was widespread in central Africa; 2) the evidence that HIV was more variable in Africa (hence longer presence); and 3) prior experience with HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 and their related retroviruses in African and Asian primates (STLV strains), especially the evidence suggesting a chimp origin of HTLV-1, coupled with the discovery of SIV by scientists in Boston, and later of many other strains identified in various African but not Asian monkeys. Human sera reacted better with some of these SIV strains from West Africa than they did with HIV-1, giving impetus to the work that led to the finding of HIV-2, and the obvious conclusion that HIV-2 came into man from these monkeys (sooty mangabey) [ 4 ].

But, how did the original infection of people in rainforests become an epidemic? Here we must rely on history. I presume people in rainforests (especially hunters) were occasionally infected for a long time, but died with their disease. Migration to cities may have been associated with increased prostitution. The movement of the rainforests to the world can be seen as the consequence of post World War II societal changes: increased travel with increased promiscuity, advancing intravenous drug addiction, and blood and blood products moving from one nation to another for medical purposes.

Part 2 (Fig. 1 ) is the identification of the disease by U.S. clinicians (1981) [ 5 – 7 ], and defining it as an immune disorder characterized by a decline of immune function and of T cells, and notably CD4 T cells, and by 1982 the identification of risk groups then called the "4 H's" (hemophiliacs, heroin addicts, homosexuals and Haitians). It is in the period (1982) when my colleagues and I began to think about this problem, and we initiated our first experiments in May 1982.

Along with Max Essex in Boston, I speculated in early 1982 that AIDS would be caused by a retrovirus. This was based on information that some retroviruses, like feline leukemia virus (FeLV), caused not only leukemia, but blood cell deficiencies including those of T cells [ 8 ]. This was apparently associated with genetic changes in the FeLV envelope. More importantly, I was influenced by our experiences with human retroviruses (HTLV-1 and HTLV-2), which we had only recently discovered [ 9 – 11 ]. The reasons were six fold: 1) HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 mainly targeted CD4 T cells; 2) we knew they were transmitted by blood, sex, and mother to infant especially by breast feeding. These were precisely the suggested modes of transmission of the putative microbial cause of AIDS suggested by James Curran of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC); 3) HTLV's were endemic in parts of Africa and in Haiti, and CDC had announced these were hot-beds for AIDS; 4) we knew that, even in the absence of leukemia, HTLV-1 could cause minor immune impairment; 5) we had just discovered HTLV-1 and HTLV-2, so why not a 3 rd human retrovirus, and one with the capacity to cause a profound immune disorder? 6) finally, as we began this work somewhat tentatively, I was encouraged by David Baltimore, who independently wondered aloud to me that a retrovirus was probably the origin of AIDS.

The idea, however, has sometimes been misunderstood and misrepresented as our hypothesizing that HTLV-1 itself was the cause of AIDS. That is clearly not the case. Our idea was that AIDS would be caused by a new retrovirus , but one in the HTLV family. At the time, there were at least a dozen theories as to the cause of AIDS, including non-infectious causes. Our hypothesis was the one that bore fruit. As we soon learned to our astonishment, HIV would be in a separate family of retroviruses.

J. Mann's Part 3 of AIDS history are the years 1983–85. He called this the period of intense discovery. It begins with the isolation of HIV. Our approach to find the virus of AIDS was to follow our successful pattern with the HTLV's, namely, the culture of blood cells from patients, activation of the T cells in these samples, growth of the T cells with IL-2, and search for reverse transcriptase actively in the supernatant. If positive, we would look for some cross reactivity with HTLV-1 or HTLV-2 with antibodies to proteins of these viruses. Concomitantly, we probed DNA and RNA of some primary tissues of AIDS patients using cDNA from HTLV-1 under rather relaxed conditions in order to detect sequences that might be related to HTLV-1 and 2. In 1982 and in early 1983, these experiments gave variable results that were sometimes highly positive, other times borderline or even negative. In retrospect, the highly positive samples (with sequences related to HTLV) were due to patients being doubly infected with HTLV-1 or HTLV-2 plus HIV, which occurred in close to 10% of our samples. Negative or borderline RT positive samples were due to our performing the RT assays later than the optimal peak of virus production, which occurs days earlier with HIV than with HTLV. Luc Montagnier was stimulated in part by our ideas brought to France by the French clinician Jacques Leibowitch and, in early 1983, I sent Montagnier IL-2 and antibodies against the HTLV's. He and his co-workers had found evidence of a retrovirus in a patient with lymphadenopathy, and they could distinguish it from the HTLV-1 and with those antibodies [ 12 ]. This was the first "clean" finding of HIV. Our samples at that time always had HTLV-1 as the dominant virus. However, by mid 1983, we were able to obtain many isolates of HIV, and by the time we published our papers (May 4, 1984) we described isolates from 48 patients [ 13 ]. Importantly, we were able to put six of these isolates into continuously growing T cell lines [ 14 ].

This was the necessary breakthrough, because for the first time there would be sufficient virus for detailed characterization and the development of a workable HIV blood test. The blood test (for serum antibodies to HIV), along with the large number of isolates from AIDS patients, were the major convincing results that HIV (which at the time we called HTLV-III and the French group called LAV) was the causative agent of AIDS [ 15 ].

Demonstrating that HIV was the cause of AIDS provided some special challenges – unlike most viral infections. The first was the long period between infection and the signs of AIDS (5 to 15 years). Physicians and public health officials do not ask a patient what they did a decade earlier, but rather think in terms of days or weeks. The second was the numerous infections a patient develops as they present with AIDS. Which one, if any, was the cause? The third was our concerns about verification. For rapid progress, it was essential to have rapid verification, and there were at least two factors that could greatly prolong achieving this goal. (1) Samples from AIDS patients were not only limited, but some institutions had forbade even their entry due to fears of infection. (2) T-cell culture technology, though available in immunology laboratories, was not widely available in virology laboratories. Both of these restrictions made it unlikely that there would be sufficiently rapid and conclusive confirmation by HIV isolation. Consequently, the blood test seemed to us to be particularly urgent for three reasons: 1) it allowed prevention of HIV transmission from contaminated blood; 2) it opened the door to our ability to follow the epidemic from the early period of infection, and 3) it provided for verification of HIV's causative role in AIDS. The test for serum antibodies was simple, inexpensive, safe, rapid, sensitive and accurate. Consequently, verification came rapidly and globally.

A problem then occurred that enormously hindered our work over the coming years. One of our culture samples became contaminated with virus sent to us by Luc Montagnier. At first we stubbornly refused to believe that this was possible, because the strain of HIV from Paris had different characteristics in cell culture. However, this has now been clarified [ 16 , 17 ]. Montagnier had unknowingly sent us a very different strain of HIV that grows well in cell lines. This strain contaminated his culture of LAV before it contaminated one of ours.

Then, from all sides and in big doses, came patent suits over royalties to the blood test, lawyers, media, politics and just plain pressure. Meanwhile, there were other odd problems such as people who denied the existence of AIDS, others who believed HIV did not exist, groups who believed HIV existed, but didn't cause AIDS, and those who believed HIV existed, caused AIDS, and was developed in a U.S. laboratory to kill African Americans and gay men. Suffice it to say, no scientist is prepared for things like this. Despite these distractions, science progressed with great speed. Mann called it the fastest pace of discovery in medical history from the time of inception of a new disease.

To briefly revisit that period, some of the noteworthy advances are listed here. They include discovery of HIV (1983–84) [ 12 – 14 ]; convincing evidence that it was the cause of AIDS ('84) [ 15 , 18 , 19 ]; modes of transmission understood ('84–'85); genome sequenced ('85) [ 20 – 22 ]; most genes and proteins defined ('84–'85) though not all their functions[ 23 – 25 ]; main target cells CD4 T cells, macrophages, and brain microglial cells – elucidated [ 26 , 27 ]; key reagents produced and made available for involved scientists all over the world ('84–'85); genomic heterogeneity of HIV ('84) – including the innumerable microvariants within a single patient ('86–'88) [ 28 , 29 ], first practical life saving advance ('85); the blood test ('84)[ 30 ]; close monitoring of the epidemic for the first time, because of the wide availability of the blood test ('85); the SIV-monkey model ('85) [ 31 , 32 ]; the beginning of therapy – AZT ('85)[ 33 ]; and the beginning understanding of pathogenesis ('85)[ 34 ].

These rapid advances led to expectations that AIDS might be quickly solved. However, those scientists with experience in retrovirology knew differently: Unless a successful vaccine was soon available, this would be a long road – an infection that might be permanent in the population as retroviruses are in many species. Furthermore, we knew by mid-1984 that the infection was becoming global. We had tested sera from many countries, and we could follow the evidence for HIV coming into a region (a positive HIV blood test) with subsequent AIDS. However, we could never anticipate the HIV African tragedy.

Despite the rapid advances in those years, I think it is still appropriate to ask whether we could have done better. For example, were we as medical scientists, health officials, doctors or simply as members of society prepared? The answer is an interesting mix of opposites! On the one hand, if AIDS had to come, we were lucky that (scientifically speaking) it came at a very good time. The 1970's saw the revelation of the replication cycle of animal retroviruses (so we had a framework to work by once HIV was established as the cause). We had most modern tools of molecular biology (mainly developed in the 1970's). We had monoclonal antibodies also developed in the 1970's. We had access to technology to grow human T-cells with IL-2 which my colleagues and I developed in the mid-1970's, and we had found other human retroviruses in the 1980's-82 giving the first credence to their presence in humans. However, if AIDS had to come, we could also say it came at the worst of times. It seems that people have a memory span not longer than 25–30 years. Here are three examples of what I mean: First, was the surprise and lack of preparation in 1918–1919 for the great influenza epidemic – forgetting lessons of the late 19 th century [ 35 ]. Secondly, there was surprise and lack of preparation at the onset of the polio epidemic in the late 1940's and early 1950's [ 36 ]. It is eerie to read accounts of that period showing that medical science in particular and society as a whole, were focused on chronic degenerative diseases, believing serious infectious diseases to be "conquered". Eerie also because, thirdly that was precisely the attitude once again by the late 1970's evidenced by the closure of some microbiology departments, and threats of increasing reductions to CDC. The microbe would be simply the playground of the molecular biologist. Some even felt humans could not be infected by retroviruses.

No group was really responsible for unraveling the cause of the new epidemic, except the CDC, but in my view the CDC cannot and does not have expertise in every class of microbes, let alone for all types of viruses, and indeed they had no expertise in animal or human retroviruses. Our group became involved only after I listened to a lecture by the CDC's James Curran, who called for help from virologists. I have suggested that the government provide base support for 10 or more virus centers, covering all types of viruses among the centers. These centers would be responsible for providing needed expertise to the CDC for the etiological agent, diagnostics and possibly therapy and prevention. In accordance with the kind of virus suspected, the center(s) would be activated. Each center might also be required to have close collaborations with at least two groups from developing nations.

Though the HIV blood test was brought forward rapidly (early 1985) to large companies that could make the test available on an industrialized scale, I believe we could have still done better. For instance, we could have tested the pooled plasma used for hemophiliacs in 1984 without a large industrial scale production of the test. I don't think anyone was thinking of this. We were advised to return to basic laboratory research and assumed someone would be doing these tests. The lesson here for me is to take more control of things that come from your own work.

Where did things go since this early period of 1982–85? Jonathan Mann describes Part 4 ('86) as the time of global mobilization. This means education leading to prevention of infection, and no doubt this was the second major practical advance and it continues today with results that vary in place and even in time. There is proven success in some places, but not all, and sometimes there is only temporary success. It is noteworthy that appropriate education also depends upon the blood test, hence on basic science.

There were many other major advances over these next 20 years ('86-06), but none were more important than therapy. This is listed as Part 5 of Mann's summary, but it was added by me as the "period" era of practical advances, but the time lines for these advances are actually from 1984–1995. AZT showed for the first time that a viral disease could be objectively treated (decline in virus levels and lessened signs of AIDS), and there is no need to embellish here on the great advances made with the triple drug therapy in the mid 1990's. This was from contributions of a great number of scientists: those who contributed to our basic understanding of HIV replication, and as a result to targets for therapy, and those who developed the culture systems to grow HIV that could also be used in drug testing, and of course to the pharmaceutical industry, especially those like E. Emini who helped design and develop the protease inhibitors.

The other major practical advances in the last two decades have mainly been an extension of the earlier ones: more widespread use of the blood test as well as educational programs; refining therapies; learning about HIV drug resistance and how best to avoid it; better care of patients; and learning about serious co-infections especially of tuberculosis and HCV. A selection of the most important basic science advances will be debatable. In my view, the most important include the following: clarification of the two HIV strain functional extremes – the pure CCR5 tropic viruses and the CXCR4 tropic viruses [ 37 – 42 ], for review, see [ 43 , 44 ]; the discovery of the first endogenous inhibitors of HIV (β-chemokines) [ 44 ]; elucidation of the mechanisms involved in the action of some the HIV non-structural proteins [ 45 , 46 ]; an appreciation of the role of abnormal immune activation in pathogenesis, which impacts not only HIV infected cells, but is also detrimental to uninfected immune cells for review, see [ 44 , 47 ]; major advances in our understanding of the various types of HIV in different regions of the world and new recombinant forms; evolving knowledge of the envelope structure [ 48 , 49 ]; the details of HIV entry into cells [ 50 ]; and various genetic and some environmental mechanisms for resisting infection and slowing progression to AIDS in infected persons, as well others fostering infection and progression [ 51 , 52 ]. These latter basic advances have already had their practical impact, including for example several new approaches for drugs that target HIV entry.

We have reached the end of the first 25 years of AIDS, and we can safely say that we know as much about HIV as we do of any pathogen and about AIDS as we do any human disease. The remaining problems and needs are evident: bringing therapy and better health infrastructure to poor nations; continuing to develop new treatments because of the need for life-long therapy and the associated drug side effects and HIV resistance; continuing and advancing education; global monitoring of the different strains of HIV for changes in their virulence, transmissibility and drug resistance; and development of a preventive vaccine which provides sterilizing immunity (or close to it) [ 53 ]. For a successful vaccine, I believe we need neutralizing antibodies that are sustained (do not need rapid recall), and I think this is a reachable objective. Parenthetically, it has often been erroneously said (most recently in the New York Times reporting of the Toronto International AIDS Conference) that, at the April 1984 press conference, Secretary of Health, Margaret Heckler stated that a successful vaccine would be available within two years. Transcripts of comments are still available and show that no such claim was made. Rather, it was said that the virus could be continuously produced in large amounts, thereby making trials possible within two years. Indeed, this proved true, because in 1986, Daniel Zagury carried out some phase 1 trials in Africa and in Paris.

Several encouraging developments provide some optimism for the future, such as the ability of some nations to diminish rates of infection by education, and major new funding sources aimed at practical achievements. One laudable example is President Bush's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, which is providing $15 billion for therapy for HIV positive patients in needy nations. We have been impressed that this effort carries out its mission with leadership by university clinical scientists who work with groups with long experience in the specific country. In contrast to alternative plans that simply and rapidly provide funds for the drugs, these programs add to local infrastructure and training, thereby reducing the prospects for creating more multi-drug resistant HIV mutants. Private foundations have also been a new forceful addition; International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) for developing vaccine candidates and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for fulfilling many needs.

There are also major concerns for the future. We know science is essential for solving the HIV problem and, as noted before, science has been responsible for all the major practical advances in fighting this disease. However, there is a growing distance between scientists and the larger public. John Moore of Cornell Weill Medical School reminded me that C.P. Snow wrote about this in the 1950's, but I think the gap has continued to widen as technology becomes more and more specialized. Sometimes, it leads to tension and even hostility by the larger public toward scientists. This is sometimes evident in AIDS, seemingly so in recent years. Consider a recent CNN program that was a positive educational force, but advertised as one composed of AIDS experts. However, not one scientist was among the experts, and the program ended with a movie actor stating that to solve the problem, we all "had to be together." It was togetherness rather than science that he informed us would solve AIDS.

To return to and end on a positive note: it is interesting and useful to remember that there has been some silver lining on the dark AIDS clouds. Consider the many positive spin-offs to science in immunology, cancer biology, basic virology, and even molecular biology along with the leadership and focus AIDS research has provided to therapy of viral infections and to vaccine development. Positive spin-offs have not been limited to science. Consider how AIDS has inspired far greater tolerance (at least in the West) of differences in sexuality and much greater scientific and humanitarian collaborations between developed and less developed nations. Certainly, this is the case for relations between the U.S. and Africa. Let us hope these advances in understanding and in conscience will continue to evolve and grow so that there will be no need for anyone to reflect on AIDS in its 50 th birthday year.

Gao F, Bailes E, Robertson DL, Chen Y, Rodenburg CM, Michael SF, Cummins LB, Arthur LO, Peeters M, Shaw GM, Sharp PM, Hahn BH: Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes. Nature. 1999, 397: 436-441. 10.1038/17130.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Keele BF, Van HF, Li Y, Bailes E, Takehisa J, Santiago ML, Bibollet-Ruche F, Chen Y, Wain LV, Liegeois F, Loul S, Ngole EM, Bienvenue Y, Delaporte E, Brookfield JF, Sharp PM, Shaw GM, Peeters M, Hahn BH: Chimpanzee reservoirs of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1. Science. 2006, 313: 523-526. 10.1126/science.1126531.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Santiago ML, Rodenburg CM, Kamenya S, Bibollet-Ruche F, Gao F, Bailes E, Meleth S, Soong SJ, Kilby JM, Moldoveanu Z, Fahey B, Muller MN, Ayouba A, Nerrienet E, McClure HM, Heeney JL, Pusey AE, Collins DA, Boesch C, Wrangham RW, Goodall J, Sharp PM, Shaw GM, Hahn BH: SIVcpz in wild chimpanzees. Science. 2002, 295: 465-10.1126/science.295.5554.465.

Sharp PM, Bailes E, Chaudhuri RR, Rodenburg CM, Santiago MO, Hahn BH: The origins of acquired immune deficiency syndrome viruses: where and when?. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001, 356: 867-876. 10.1098/rstb.2001.0863.

Siegal FP, Lopez C, Hammer GS, Brown AE, Kornfeld SJ, Gold J, Hassett J, Hirschman SZ, Cunningham-Rundles C, Adelsberg BR: Severe acquired immunodeficiency in male homosexuals, manifested by chronic perianal ulcerative herpes simplex lesions. N Engl J Med. 1981, 305: 1439-1444.

Gottlieb MS, Schroff R, Schanker HM, Weisman JD, Fan PT, Wolf RA, Saxon A: Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and mucosal candidiasis in previously healthy homosexual men: evidence of a new acquired cellular immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med. 1981, 305: 1425-1431.

Friedman-Kien AE: Disseminated Kaposi's sarcoma syndrome in young homosexual men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981, 5: 468-471.

Wernicke D, Trainin Z, Ungar-Waron H, Essex M: Humoral immune response of asymptomatic cats naturally infected with feline leukemia virus. J Virol. 1986, 60: 669-673.

PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kalyanaraman VS, Sarngadharan MG, Robert-Guroff M, Miyoshi I, Golde D, Gallo RC: A new subtype of human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV-II) associated with a T-cell variant of hairy cell leukemia. Science. 1982, 218: 571-573. 10.1126/science.6981847.

Poiesz BJ, Ruscetti FW, Gazdar AF, Bunn PA, Minna JD, Gallo RC: Detection and isolation of type C retrovirus particles from fresh and cultured lymphocytes of a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980, 77: 7415-7419. 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7415.

Poiesz BJ, Ruscetti FW, Reitz MS, Kalyanaraman VS, Gallo RC: Isolation of a new type C retrovirus (HTLV) in primary uncultured cells of a patient with Sezary T-cell leukaemia. Nature. 1981, 294: 268-271. 10.1038/294268a0.

Barre-Sinoussi F, Chermann JC, Rey F, Nugeyre MT, Chamaret S, Gruest J, Dauguet C, Axler-Blin C, Vezinet-Brun F, Rouzioux C, Rozenbaum W, Montagnier L: Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Science. 1983, 220: 868-871. 10.1126/science.6189183.

Gallo RC, Salahuddin SZ, Popovic M, Shearer GM, Kaplan M, Haynes BF, Palker TJ, Redfield R, Oleske J, Safai B: Frequent detection and isolation of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and at risk for AIDS. Science. 1984, 224: 500-503. 10.1126/science.6200936.

Popovic M, Sarngadharan MG, Read E, Gallo RC: Detection, isolation, and continuous production of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and pre-AIDS. Science. 1984, 224: 497-500. 10.1126/science.6200935.

Sarngadharan MG, Popovic M, Bruch L, Schupbach J, Gallo RC: Antibodies reactive with human T-lymphotropic retroviruses (HTLV-III) in the serum of patients with AIDS. Science. 1984, 224: 506-508. 10.1126/science.6324345.

Wain-Hobson S, Vartanian JP, Henry M, Chenciner N, Cheynier R, Delassus S, Martins LP, Sala M, Nugeyre MT, Guetard D: LAV revisited: origins of the early HIV-1 isolates from Institut Pasteur. Science. 1991, 252: 961-965. 10.1126/science.2035026.

Guo HG, Chermann JC, Waters D, Hall L, Louie A, Gallo RC, Streicher H, Reitz MS, Popovic M, Blattner W: Sequence analysis of original HIV-1. Nature. 1991, 349: 745-746. 10.1038/349745a0.

Schupbach J, Popovic M, Gilden RV, Gonda MA, Sarngadharan MG, Gallo RC: Serological analysis of a subgroup of human T-lymphotropic retroviruses (HTLV-III) associated with AIDS. Science. 1984, 224: 503-505. 10.1126/science.6200937.

Safai B, Sarngadharan MG, Groopman JE, Arnett K, Popovic M, Sliski A, Schupbach J, Gallo RC: Seroepidemiological studies of human T-lymphotropic retrovirus type III in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Lancet. 1984, 1: 1438-1440. 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91933-0.

Sanchez-Pescador R, Power MD, Barr PJ, Steimer KS, Stempien MM, Brown-Shimer SL, Gee WW, Renard A, Randolph A, Levy JA: Nucleotide sequence and expression of an AIDS-associated retrovirus (ARV-2). Science. 1985, 227: 484-492. 10.1126/science.2578227.

Ratner L, Haseltine W, Patarca R, Livak KJ, Starcich B, Josephs SF, Doran ER, Rafalski JA, Whitehorn EA, Baumeister K: Complete nucleotide sequence of the AIDS virus, HTLV-III. Nature. 1985, 313: 277-284. 10.1038/313277a0.

Wain-Hobson S, Sonigo P, Danos O, Cole S, Alizon M: Nucleotide sequence of the AIDS virus, LAV. Cell. 1985, 40: 9-17. 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90303-4.

Arya SK, Gallo RC, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Popovic M, Salahuddin SZ, Wong-Staal F: Homology of genome of AIDS-associated virus with genomes of human T-cell leukemia viruses. Science. 1984, 225: 927-930. 10.1126/science.6089333.

Muesing MA, Smith DH, Cabradilla CD, Benton CV, Lasky LA, Capon DJ: Nucleic acid structure and expression of the human AIDS/lymphadenopathy retrovirus. Nature. 1985, 313: 450-458. 10.1038/313450a0.

Robey WG, Safai B, Oroszlan S, Arthur LO, Gonda MA, Gallo RC, Fischinger PJ: Characterization of envelope and core structural gene products of HTLV-III with sera from AIDS patients. Science. 1985, 228: 593-595. 10.1126/science.2984774.

Harper ME, Marselle LM, Gallo RC, Wong-Staal F: Detection of lymphocytes expressing human T-lymphotropic virus type III in lymph nodes and peripheral blood from infected individuals by in situ hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986, 83: 772-776. 10.1073/pnas.83.3.772.

Shaw GM, Hahn BH, Arya SK, Groopman JE, Gallo RC, Wong-Staal F: Molecular characterization of human T-cell leukemia (lymphotropic) virus type III in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Science. 1984, 226: 1165-1171. 10.1126/science.6095449.