- Skip to search box

- Skip to main content

Princeton University Library

Dissertations/theses.

The Senior Thesis

From the outset of their time at Princeton, students are encouraged and challenged to develop their scholarly interests and to evolve as independent thinkers.

The culmination of this process is the senior thesis, which provides a unique opportunity for students to pursue original research and scholarship in a field of their choosing. At Princeton, every senior writes a thesis or, in the case of some engineering departments, undertakes a substantial independent project.

Integral to the senior thesis process is the opportunity to work one-on-one with a faculty member who guides the development of the project. Thesis writers and advisers agree that the most valuable outcome of the senior thesis is the chance for students to enhance skills that are the foundation of future success, including creativity, intellectual engagement, mental discipline and the ability to meet new challenges.

Many students develop projects from ideas sparked in the classes they’ve taken; others fashion their topics on the basis of long-standing personal passions. Most thesis writers encounter the intellectual twists and turns of any good research project, where the questions emerge as they proceed, often taking them in unexpected directions.

Planning for the senior thesis starts in earnest in the junior year, when students complete a significant research project known as the junior paper. Students who plan ahead can make good use of the University's considerable resources, such as receiving University funds to do research in the United States or abroad. Other students use summer internships as a launching pad for their thesis. For some science and engineering projects, students stay on campus the summer before their senior year to get a head start on lab work.

Writing a thesis encourages the self-confidence and high ambitions that come from mastering a difficult challenge. It fosters the development of specific skills and habits of mind that augur well for future success. No wonder generations of graduates look back on the senior thesis as the most valuable academic component of their Princeton experience.

Navigating Colombia’s Magdalena River, One Story At A Time

For his senior thesis, Jordan Salama, a Spanish and Portuguese major, produced a nonfiction book of travel writing about the people and places along Colombia’s main river, the Magdalena.

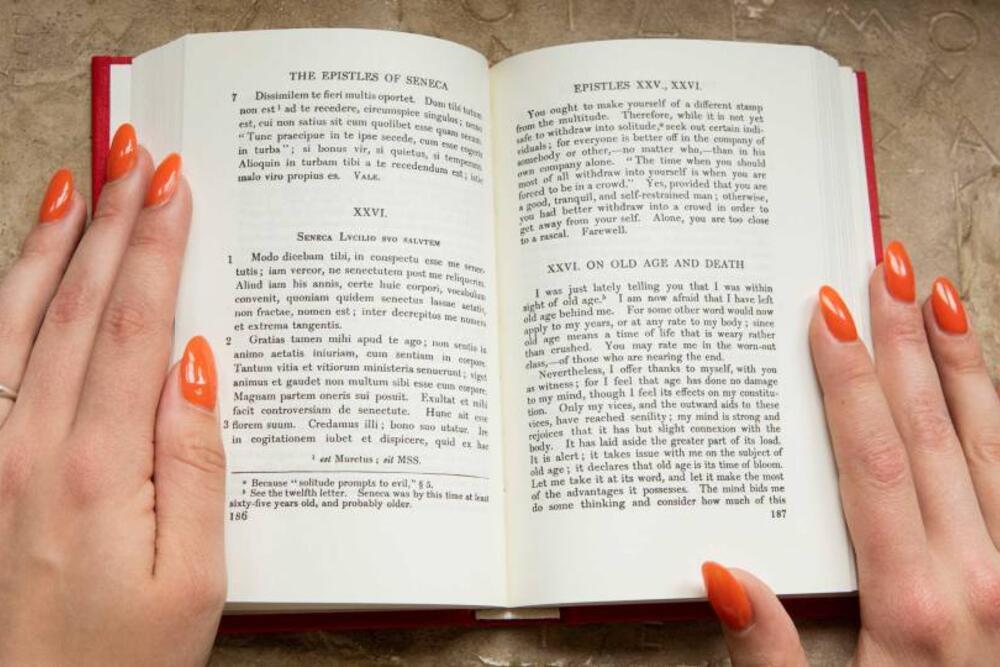

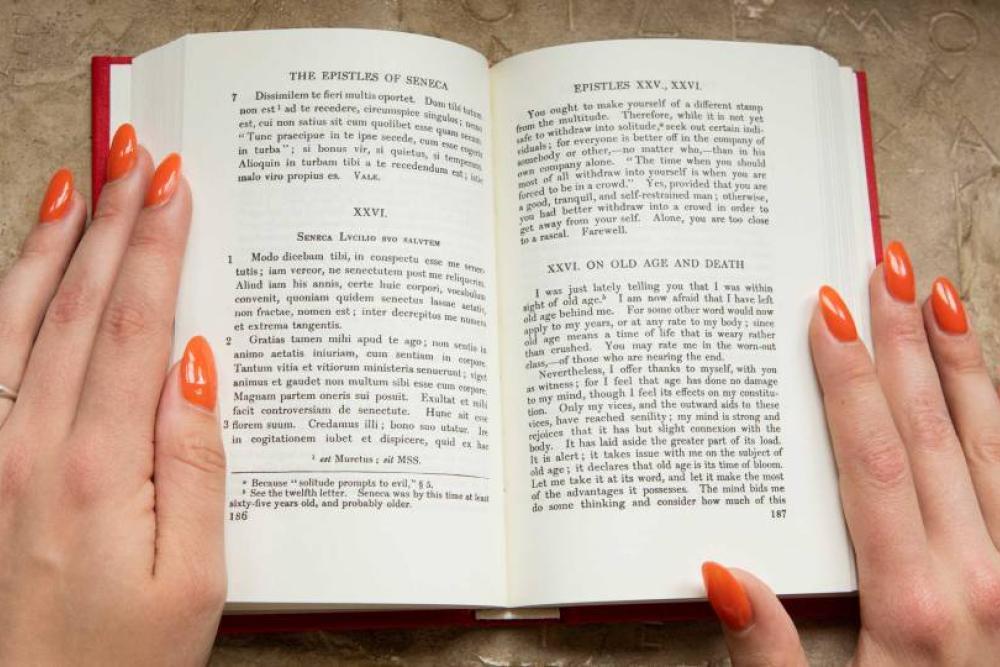

Embracing the Classics to Inform Policymaking for Public Education

For her senior thesis, Emma Treadwayconsiders how the basic tenets of Stoicism — a school of philosophy that dates from 300 BCE — can teach students to engage empathetically with the world and address inequities in the classroom.

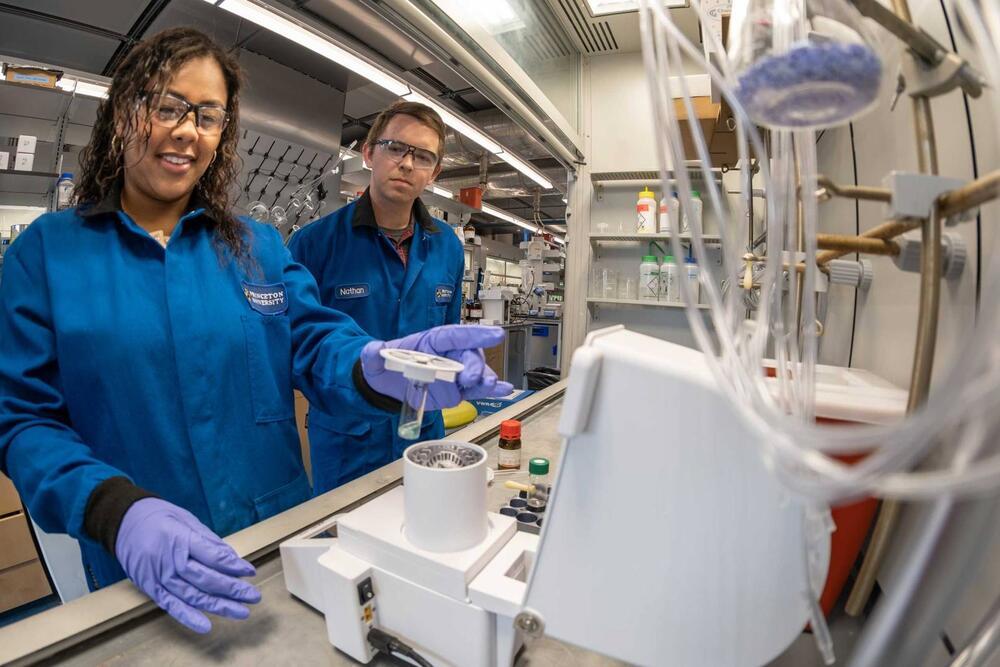

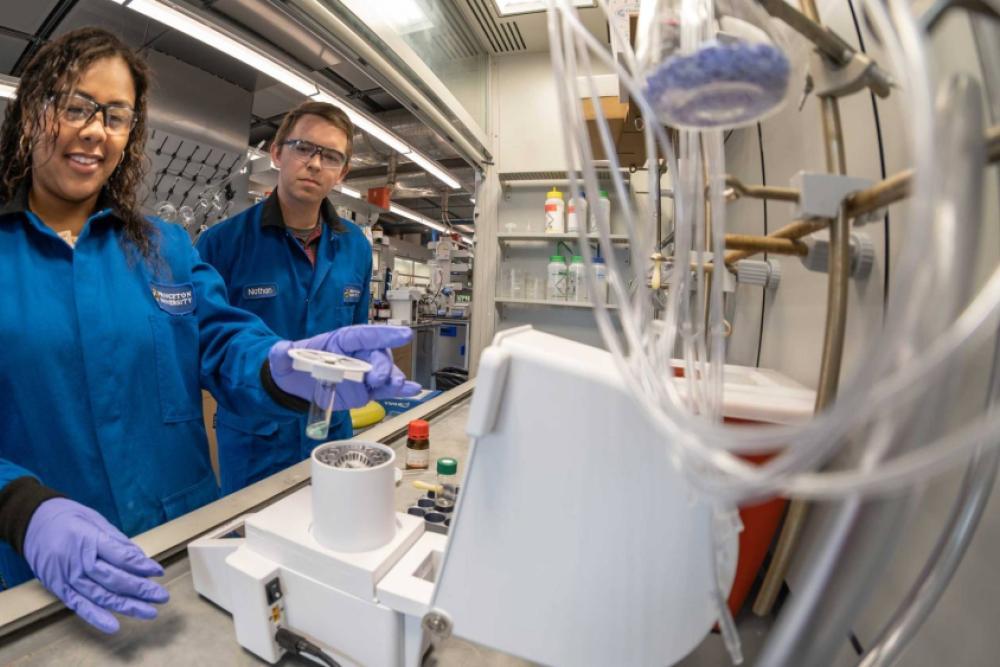

Creating A Faster, Cheaper and Greener Chemical Reaction

One way to make drugs more affordable is to make them cheaper to produce. For her senior thesis research, Cassidy Humphreys, a chemistry major with a passion for medicine, took on the challenge of taking a century-old formula at the core of many modern medications — and improving it.

The Humanity of Improvisational Dance

Esin Yunusoglu investigated how humans move together and exist in a space — both on the dance floor and in real life — for the choreography she created as her senior thesis in dance, advised by Professor of Dance Susan Marshall.

From the Blog

The infamous senior thesis, revisiting wwii: my senior thesis, independent work in its full glory, advisers, independent work and beyond.

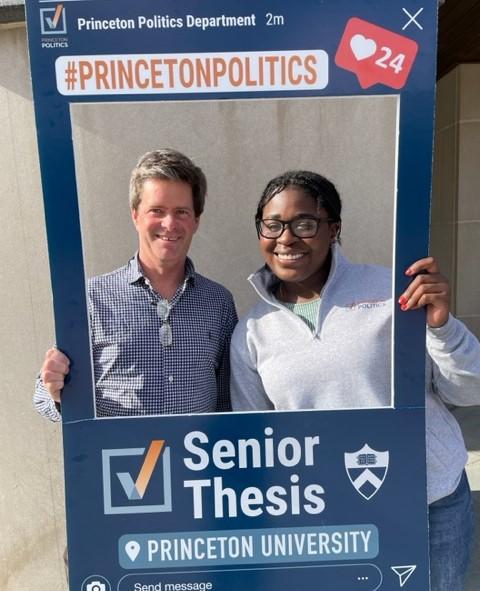

Senior Thesis

During the senior year, each student writes a thesis. The senior thesis is expected to make an original (or otherwise distinctive) contribution to broader knowledge in the field in which the student is working. It is important that the thesis be situated explicitly in relation to existing published literature. The senior thesis must be judged satisfactory by two members of the faculty, at least one of whom must be a member of the Department of Politics.

It is common, but by no means required, for junior paper topics, especially in the spring term, to serve as starting points for a senior thesis topic. The Department encourages students to use the summer between junior and senior year for work on the senior thesis.

Your senior thesis may expand upon ideas that you explored in the JP. You may draw on and cite your own JP just like you would use other resources. In addition, you may re-use a limited portion of your JP in your senior thesis; for instance, the literature review could be re-used across the two. Whenever material from the JP is re-used, you must add a footnote noting the duplication across the JP or senior thesis. Note this policy does not affect the standard university guidelines for attributing ideas and research findings, whenever appropriate. The same policy holds with respect to incorporating the Fall junior research prospectus into either the Spring JP or senior thesis.

The length of a senior thesis is generally about 100 double-spaced pages and rarely under 80 pages. No thesis should be longer than 125 pages, including appendices. (This limit does not include the ancillary pages for the title, dedication, table of contents, abstract, bibliography and honor code statement.) Any pages after 125 may or may not be read by the second reader. A thesis longer than 125 pages will not be considered for Politics thesis prizes.

- Senior Thesis Project Planning Map and Timeline

- Research Advice

- Senior Thesis Funding

- Submission and Grading of Independent Work

Also, seniors are required to prepare and present a professional poster describing their senior thesis results.

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

Tips on Writing a Philosophy Paper for Non-Philosophy Majors

Last spring, I took PHI 203: Introduction to Metaphysics and Epistemology. I had never taken a philosophy class before in my life, and in the beginning it was difficult to wrap my head around the theories brought up in the readings and precept, let alone execute a coherent argument in a paper. Throughout the course, I learned a lot not just about the theories and arguments in philosophy, but about the distinct style of philosophical writing itself. In drafting the papers, I realized just how different writing a philosophy paper is compared to writing papers in other humanities and social science disciplines. This post contains some tips on how to approach a philosophy paper for those unfamiliar with the field:

Make your argument simple. Throughout the course, we were taught that we did not need to make a grand claim in order to create a solid paper. In a philosophy paper of any scope, it’s most important that you defend and execute your claims coherently . Especially since you will most likely not have a lot of room to develop your argument, it’s important not to be overambitious–this might lead you to make an elaborate claim with poorly supported examples and evidence. You can instead take a modest point and develop it gradually with sound explanations, which will lead to a much stronger paper. As was stated on the PHI 203 syllabus, the goal in a philosophy paper is not to “offer your own staggeringly original theory of everything” but to make “incremental progress on a philosophical problem.”

Examples are crucial to your argument. No matter how minor a statement you are making, clarifying that statement with an example can help solidify your argument and make your paper much stronger. Especially when you are discussing highly abstract ideas and theories, giving a few real-life examples can make your argument more concrete and accessible to the reader. The examples, however, should not be complex, and should serve to further clarify your argument. Using hypothetical examples can often work as a form of evidence to further back your argument, and can also help the reader better grasp the usually abstract terms and definitions in the claim you are discussing. For instance, in my first short paper about Pascal’s Wager, I used the example of winning money to explain how people do not give up a finite sum of happiness for a slim chance of infinite happiness.

Anticipate and respond to possible objections. Addressing possible objections to your argument is critical in philosophy and makes for a solid, well-founded paper. If you are aware of possible objections and loopholes in your argument, do not leave them unaddressed and hope that your reader won’t notice them. Do not feel pressured, however, to provide an answer to any and all potential counterarguments. If it proves to be difficult, you do not even have to provide an answer to your counterarguments–it is more important that you recognize and discuss the strongest oppositions in your paper.

Keep your language direct and concise. Precision and clarity are key when writing a philosophy paper. Having written mostly English and Politics papers, I was more used to embellishing my argument with flowery prose and allowing some room for digression. In my philosophy class, however, we were given a strict word limit for each writing assignment, and our first papers were limited to 500 words. I could not afford to waste words on ornate transitions and language, and realized the importance of executing my argument well through a clear, straightforward structure. In a philosophy paper, each sentence should have a substantial purpose, adding something new to the argument or clarifying a previous point. This clear structure is especially important as philosophy papers often deal with very abstract concepts. As such, it’s imperative that you guide the reader step by step through the logic of your argument.

Define all the terms you discuss in your paper. In a philosophy paper, you usually consider an existing thesis and either support it or raise an objection to it. In doing so, it’s imperative that you familiarize yourself with the specific terms of the thesis and define them in your paper. In addition to the terms that are specific to your argument, you should also be familiar with terms used frequently in philosophy, such as a priori and a posteriori . When I was writing my first paper, I was very confused on how to determine the validity of an argument, as an argument being valid in the conventional sense is not necessarily the same as how an argument is valid in philosophy. As such, familiarizing yourself with the specific terms of the thesis and defining them in your paper, as well as knowing the basic terminology used in philosophy are crucial steps. The Norton Introduction to Philosophy , the required book for PHI 203, contains sections titled, “A Brief Guide to Logic and Argumentation” and “Some Guidelines for Writing Philosophy Papers,” which would be great in learning the special terminology and principles in logic.

Discuss your ideas with others. Especially with philosophy papers, it’s easy to get lost in the abstract technicalities of your argument, which is bound to make it even more confusing for your reader. It’s critical then, that you have the chance to talk through your ideas with others, whether that’s your preceptor, classmates, or even roommates. Even if you understand your own argument, your reader may have difficulty comprehending it through your writing. When drafting my papers, I often went to my preceptor during office hours to discuss my ideas, allowing me to more easily identify the loopholes that were particularly confusing. I was then able to more clearly formulate and articulate in writing my argument.

Philosophy papers require a very particular approach, and it can be daunting to write one if you are used to the conventional research or argumentative paper. However, you can learn so much from a philosophy class, including philosophical concepts, argumentative theories, and the principles of clear writing. Hopefully these tips will be helpful in writing your next philosophy paper!

–Soo Young Yun, Humanities Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

The Senior Thesis

From the outset of their time at Princeton, students are encouraged and challenged to develop their scholarly interests and to evolve as independent thinkers.

The culmination of this process is the senior thesis, which provides a unique opportunity for students to pursue original research and scholarship in a field of their choosing. At Princeton, every senior writes a thesis or, in the case of some engineering departments, undertakes a substantial independent project.

Integral to the senior thesis process is the opportunity to work one-on-one with a faculty member who guides the development of the project. Thesis writers and advisers agree that the most valuable outcome of the senior thesis is the chance for students to enhance skills that are the foundation of future success, including creativity, intellectual engagement, mental discipline and the ability to meet new challenges.

Many students develop projects from ideas sparked in the classes they’ve taken; others fashion their topics on the basis of long-standing personal passions. Most thesis writers encounter the intellectual twists and turns of any good research project, where the questions emerge as they proceed, often taking them in unexpected directions.

Planning for the senior thesis starts in earnest in the junior year, when students complete a significant research project known as the junior paper. Students who plan ahead can make good use of the University's considerable resources, such as receiving University funds to do research in the United States or abroad. Other students use summer internships as a launching pad for their thesis. For some science and engineering projects, students stay on campus the summer before their senior year to get a head start on lab work.

Writing a thesis encourages the self-confidence and high ambitions that come from mastering a difficult challenge. It fosters the development of specific skills and habits of mind that augur well for future success. No wonder generations of graduates look back on the senior thesis as the most valuable academic component of their Princeton experience.

Navigating Colombia’s Magdalena River, One Story At A Time

For his senior thesis, Jordan Salama, a Spanish and Portuguese major, produced a nonfiction book of travel writing about the people and places along Colombia’s main river, the Magdalena.

Embracing the Classics to Inform Policymaking for Public Education

For her senior thesis, Emma Treadwayconsiders how the basic tenets of Stoicism — a school of philosophy that dates from 300 BCE — can teach students to engage empathetically with the world and address inequities in the classroom.

Creating A Faster, Cheaper and Greener Chemical Reaction

One way to make drugs more affordable is to make them cheaper to produce. For her senior thesis research, Cassidy Humphreys, a chemistry major with a passion for medicine, took on the challenge of taking a century-old formula at the core of many modern medications — and improving it.

The Humanity of Improvisational Dance

Esin Yunusoglu investigated how humans move together and exist in a space — both on the dance floor and in real life — for the choreography she created as her senior thesis in dance, advised by Professor of Dance Susan Marshall.

From the Blog

The infamous senior thesis, revisiting wwii: my senior thesis, independent work in its full glory, advisers, independent work and beyond.

- Princeton University Undergraduate Senior Theses, 1924-2023

- Modern Languages, 1926-1958

Items in Dataspace are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated.

Search form

Inbox the value of the thesis, realized in retrospect.

We are grateful to Jimin Kang ’21 for her thorough research and look back at the centennial of the Princeton thesis in “The Senior Thesis at 100: Back to the Future” (May issue). Kang’s article properly credits Dean Luther Eisenhart as progenitor of Princeton’s independent study and the senior thesis from his time as dean of the faculty in the early 1920s.

Like many other readers of the piece, the pain of this ordeal and ultimately sense of accomplishment came back to us as we relived our own thesis sagas. What gives us additional pride, though, is how this capstone project of the Princeton undergraduate academic program has not only survived but thrived for a century, for reasons not only relayed in Kang’s piece but that Eisenhart himself understood as stated in his 1945 book, The Educational Process : “Many students have said that it was their first experience in college in feeling that what they were doing was really their own. Also graduates have testified that their work on a senior thesis was excellent training for investigations they made later, as part of their business or professional life, or as interesting avocation.”

The true value of the thesis experience, it seems, is most often realized in retrospect. We say thank you to Jimin Kang for her fine article, and we also say thank you to Dean Eisenhart for this enduring contribution to Princeton.

Editor’s note: The writers, brothers, are great nephews of Dean Luther Eisenhart.

- Seminars & Events -

- Directions -

- IT Support -

- Search for:

- Catalysis / Synthesis

- Chemical Biology

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Spectroscopy / Physical Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment

- Princeton Institute for Computational Science and Engineering

- Princeton Materials Institute

- Princeton Catalysis Initiative

- Research Facilities Overview

- Biophysics Core Facility

- Crystallography

- Merck Catalysis Center

- NMR Facility

- Mass Spectrometry

- Other Spectroscopy

- Small Molecule Screening Center

- Ultrafast Laser Spectroscopy

- Industrial Associates Program

- Libraries & Computing

- Frick Chemistry Laboratory

- Administration & Staff

- Business & Grants Office

- Frick Event Guidelines

- Faculty & Academic Jobs

- Seminars & Events

- Postdocs Overview

- New Postdocs

- Family-Friendly Initiatives

- Graduate Program Overview

- Academic Program

- Campus Life

- Living in Princeton

- Graduate News

- Undergraduate Overview

- Summer Undergrad Research Fellows in Chemistry

- Other Summer Research Opportunities

- Outside Course Approval

- PU Chemical Society

- Our Commitment

- Resources and Reporting

- Visiting Faculty Research Partnership

- Join the Department

“I wrote a book!” Chemistry concentrators offer a few words on the senior thesis

From the moment they are admitted to Princeton University, undergraduates anticipate the singular requirement of the senior thesis. It offers the chance for them to pursue original research and scholarship in a field of their choosing while working one-on-one with an adviser. Princeton is one of the few Ivy League schools to require a thesis for graduation.

Along with the rest of the senior class, the 23 chemistry concentrators finished their theses about a month ago. But the impact of the experience lingers, often for years, sometimes for decades.

We asked five graduating seniors about the process, which used to earn them the right to boast: “I wrote a book.” Today, senior theses in the Department of Chemistry are digital. But the phrase still carries the day.

Concentrators’ answers, edited for length, appear below. Congratulations to the Great Class of ’24 on achieving this commendable milestone.

Kit Foster, Class of '24

Adviser: Erik Sorensen

Thesis: Advancements in Nitrogen Deletion Enabled Squalene Synthesis

Was this a rewarding experience?

It was a real joy scouring the literature to find historical ways of making my compound of interest (i.e. Squalene). The chemists of old were so creative with their methods, and since Squalene is a significant molecule in the development of total synthesis, many “big name” scientists of the past century have taken a crack at producing it. By reading their papers, I became acquainted with these chemists and their stylistic quirks in a very parasocial way. By the time I was writing my conclusion, they felt like close friends of mine. They felt like real, fallible people who face both hurdles and roadblocks in their own unique ways.

Knowing the ideas of important players in your field is critical for any undergraduate education, but demystifying your predecessors is uniquely important for science students. We are far too frequently fed the narrative that pure genius exists and that we as students can only achieve genius status by living up to impossible standards. I felt like writing this thesis peeled back the facade that the academic giants are somehow different from the rest of us; and in doing so, I can now see myself as being capable of similar achievements.

What was the most difficult part of your thesis?

For me, there was this urge to push off certain easy but monotonous tasks. I found myself saying, “I’ll just write up my bibliography right before I submit,” or “I can edit this sentence for word-flow later; it’s easy and low priority.” This was a mistake because, by the end, these small tasks added up. While actually writing my thesis was slow but relatively relaxing, the last dash to finish all the little things that I hated doing was extremely mentally taxing. So, here is my advice to future seniors who are delving into their thesis: write your bibliography before the last day. You’ll thank me later.

What are your post-commencement plans?

I will be working in a post-baccalaureate program at Belharra Therapeutics in San Diego, CA. I’m really excited to continue developing my chemical intuition and immerse myself in drug-discovery chemistry, a field with which I am currently completely unacquainted. While New Jersey has been beautiful, I am also thrilled to be moving back to Southern California. I’ll be closer to my family and delicious Mexican restaurants, both of which I enjoy exorbitantly.

Emma Cavendish, Class of '24

EMMA CAVENDISH

Adviser: Paul Chirik

Thesis: Upgrading Bioderived Dienes through Cycloaddition and Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization: Catalyst Development and Materials Design

I think I like researching more than I like writing about the research, but there is something about putting it all down on paper that brings more clarity to the process and highlights weaknesses and areas that need further exploration.

The most difficult part of completing the thesis was selecting a stopping point. There is always more research that can be done and that would be informative, so I tried to wait until the last possible minute to wrap up the research that would be included in my paper.

After graduation I will be doing clinical research at Boston Children’s Hospital while applying to medical school.

Sandeep Mangat, Class of '24

SANDEEP MANGAT

Adviser: Erik Sorensen (also: Nick Falcone, John Hoskin, Samuel He)

Thesis: N-to-C Transmutations of Nitrogen-Containing Heterocycles

What I found most rewarding about the thesis was that it allowed me to become a sort of expert in a very focused field in organic synthesis. Classes had given me a broad look at the subject, but spending a year researching a specific topic helped me master some of the reactions we learned about in pursuit of my own synthesis goals.

I enjoyed the research process because it offered a break from the pace of the Princeton life. I like working with my hands and the demands of a project that involved a lot of benchwork gave me the chance to do just that. Purifying a reaction, for instance, allowed me to step away from my computer screen, before which I’d spent most of my time as a student. It allowed me to exercise my mind in a different way.

One thing I learned about the writing process was to have trust in the overarching goals of the project when trying to write about it. There were times at which I’d get lost in the granularity of a task; getting overwhelmed, for instance, by a figure that was taking too long to make sometimes led me to forget about the successes I luckily was able to achieve in the lab.

The most difficult part about completing this “book” was definitely balancing my time between the lab and my other commitments. In the year I did my thesis research, I was also an editor at The Daily Princetonian , a job that required a lot of attention. It was not uncommon for me to run out of lab to interview a source or write up the latest scoop. Simultaneously, running a column on a crude product required my undivided attention. Navigating these competing forces was difficult but, ultimately, successful, as both my articles and my thesis were able to be published!

Guided by an interest in bringing science to wider audiences, my next step after graduation is to pursue a career in journalism.

Beianka Tomlinson, Class of '24

BEIANKA TOMLINSON

Adviser: Joshua Rabinowitz

Thesis: Investigating how purified diets synergize with cancer therapy to improve outcomes in mouse models of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and melanoma

Was this a rewarding experience?

I learned a lot from writing my thesis—more than I thought I would. I had thought that the majority of my learning would take place in the lab or when I was doing my literature review, but it was surprising how much new knowledge and insight emerged as I was synthesizing the written parts of my thesis. What I learned about the writing process is that learning does not end in the lab but continues throughout all aspects of the project.

I really enjoy being in the lab, so even though it presented challenges as I managed my other responsibilities as a student, it was not the most difficult part for me. Writing, surprisingly, proved to be extremely rigorous. I was nervous about writing because there were so many results I had to work with and I didn’t know where to begin. I also found that the writing process magnifies parts of your project that has gaps or inconsistencies, so I always have to be taking notes on which parts of my lab work to review and fine-tune. I had to be more mentally present when I was writing than when I was in the lab. This process, despite being the most challenging, probably taught me the most about my project and even about myself and my tendencies as a researcher.

I plan to be an oncologist by profession, but I also enjoy research. In particular, I want to conduct research on diseases like cancer that affect people of color and those from low-income communities the most, as these groups are the most neglected by the medical community. Because of this long-held interest, I will be a post-baccalaureate fellow at the National Institute of Aging under the National Institutes of Health, where I will spend two years studying age-related diseases and how vulnerable populations develop a propensity for them on both an epidemiological and molecular level. I will then go to medical school and become a physician, practicing in both oncology and conducting cancer research.

Jess Wang, Class of '24

Thesis: Towards the Synthesis of Blazeispirol A: Progress Regarding the Preparation of an Enantiopure Phosphonate Fragment

Research-wise, I found the creative process involved in synthetic design to be the most rewarding. I also enjoyed organizing the different elements of this project together to provide a cohesive narrative in my writing.

The most difficult part of writing this thesis was the amount of time it took!

After graduation, I will be teaching at a college in Vietnam for one year through Princeton in Asia . Afterwards, I will pursue my Ph.D. in chemistry at Caltech.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Bound Ph.D. Dissertations in the Mudd Manuscript Library stacks. The Princeton University Archives located within the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library is the official repository for Undergraduate Senior Theses, Master's Theses and Ph.D. Dissertations. Princeton University undergraduate senior theses range from 1924 to the present.

Information on the dissertation topics written by Department of Philosophy Ph.D. recipients can be found in the following documents: ... The Department of Philosophy 212 1879 Hall Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544-1006. Phone: (609) 258-4289 Fax: (609) 258-1502. Footer menu.

New Warbeke Prize for theses in any area of philosophy (including history of philosophy) except moral or social philosophy or aesthetics. There are also two smaller prizes. ... The Department of Philosophy 212 1879 Hall Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544-1006. Phone: (609) 258-4289

Special Collections Schedule - Summer 2024. The Special Collections reading rooms in Firestone and Mudd Libraries will be closed on the following upcoming holidays: Monday, May 27 (Memorial Day), Wednesday, June 19 (Juneteenth), Thursday, July 4 (Independence Day), and Monday, September 2 (Labor Day). We will be closing at 12:00pm on Friday ...

Princeton University Undergraduate Senior Theses, 1924-2023 Members of the Princeton community wishing to view a senior thesis from 2014 and later while away from campus should follow the instructions outlined on the OIT website for connecting to campus resources remotely. ... Philosophy, 1924-2023 Physics, 1936-2023 Politics, 1927-2023 ...

The Department of Philosophy 212 1879 Hall Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544-1006. Phone: (609) 258-4289 Fax: (609) 258-1502

Princeton University Library One Washington Road Princeton, NJ 08544-2098 USA (609) 258-1470

This thesis can be viewed in person at the Mudd Manuscript Library. To order a copy complete the Senior Thesis Request Form. For more information contact [email protected]. Type of Material: Princeton University Senior Theses: Appears in Collections: Philosophy, 1924-2023

Princeton University Masters Theses, 2022-2024; Princeton University Undergraduate Senior Theses, 1924-2023; ... Login . My DataSpace; Princeton University Doctoral Dissertations, 2011-2024; Princeton University Doctoral Dissertations, 2011-2024 Communities Collections ; Items; ... Philosophy Physics Plasma Physics

At Princeton, every senior writes a thesis or, in the case of some engineering departments, undertakes a substantial independent project. ... For her senior thesis, Emma Treadwayconsiders how the basic tenets of Stoicism — a school of philosophy that dates from 300 BCE — can teach students to engage empathetically with the world and address ...

Department of Philosophy grad alums (L-R) Jessica Moss *04, Jill Sigman *98 and David Gordon *09 shared their different career paths at the department's annual Graduate Princeton and Beyond dinner. ... The Department of Philosophy 212 1879 Hall Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544-1006. Phone: (609) 258-4289 Fax: (609) 258-1502. Footer menu ...

Princeton philosophy major taught be to think clearly, argue persuasively and write clearly," says another, a journalist. ... thesis matters such as extracurricular activities, so as to determine what periods should see the most intensive work on the thesis. Once an advisor has been found or assigned and the project begun, a regular schedule of

For Princeton philosophy majors, the chief opportunity to acquire and display such skills and abilities comes with junior and especially senior independent work. 4 ... thesis matters such as extracurricular activities, so as to determine what periods should see the most intensive . the . of . philosophy.

The senior thesis is expected to make an original ... Philosophy of Law, Constitutional Interpretation, Civil Liberties, Moral and Political Philosophy, Bioethics, Law and Religion, Natural Law Theory ... 001 Fisher Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1012 T (609) 258-4760 F (609) 258-1110.

Tuesday, April 11, 2023 Deadline for SENIOR THESIS (three copies—two bound, one electronic) (see TURNING IN THE THESIS for details) Tuesday, May 2, 2023 Oral presentations (see THE THESIS SYMPOSIUM for details) All reports, except for the final thesis, must be turned in using Canvas by 4:30 . p.m. on the date indicated.

Overview: Work in this area is centered on relations between religion and philosophy, including religious uses of philosophical ideas, philosophical criticisms of religion, and philosophical issues in the study of religion. Critical attention is given to theories of knowledge and meaning, social-scientific theories of religion, and to problems ...

In a philosophy paper, each sentence should have a substantial purpose, adding something new to the argument or clarifying a previous point. This clear structure is especially important as philosophy papers often deal with very abstract concepts. As such, it's imperative that you guide the reader step by step through the logic of your argument.

At Princeton, every senior writes a thesis or, in the case of some engineering departments, undertakes a substantial independent project. ... For her senior thesis, Emma Treadwayconsiders how the basic tenets of Stoicism — a school of philosophy that dates from 300 BCE — can teach students to engage empathetically with the world and address ...

Princeton Neuroscience Institute; Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory; Princeton School of Public and International Affairs; Princeton University Doctoral Dissertations, 2011-2023; Princeton University Library; Princeton University Masters Theses, 2022-2023; Princeton University Undergraduate Senior Theses, 1924-2022; Seeger Center for Hellenic ...

Office. Green Hall, 3-S-8. Greg Yudin is a Professor of Political Philosophy and an MA Programme Head at The Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences. He studies political theory of democracy with the special emphasis on public opinion polls as a technology of representation and governance in contemporary politics.

INTRODUCTION. Ancient Egypt has le us with impressive remains of an early civilization. ese remains also directly and indirectly document the development and use of a mathematical cul-ture—without which, one might argue, other highlights of ancient Egyptian culture would not have been possible. Egypt's climate and geographic situation have ...

Bill was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1980, to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1984, and to the Finnish Academy of Arts and Sciences. For his Ph.D. thesis, Bill investigated the homology of loop spaces; Moore had given Bill a very beautiful idea. On the eve of Bill's departure to Rochester in August 1957, the ...

Class of 1869 Prize for theses in moral or social philosophy. Old Warbeke Prize for theses in aesthetics. New Warbeke Prize for theses in any area of philosophy except moral or social philosophy or aesthetics Dickinson Prize for theses in logic or theory of knowledge. Prizes are announced and awarded at the Class Day reception for parents.

The Value of the Thesis, Realized in Retrospect. We are grateful to Jimin Kang '21 for her thorough research and look back at the centennial of the Princeton thesis in "The Senior Thesis at 100: Back to the Future" (May issue). Kang's article properly credits Dean Luther Eisenhart as progenitor of Princeton's independent study and the ...

The Department of Geosciences and Princeton University congratulates Dr. Sirus Han on successfully defending their Ph.D. thesis: "In situ X-Ray Diffraction of Key High-Pressure Materials Under Dynamic Compression" on Thursday, May 16, 2024.

It offers the chance for them to pursue original research and scholarship in a field of their choosing while working one-on-one with an adviser. Princeton is one of the few Ivy League schools to require a thesis for graduation. Along with the rest of the senior class, the 23 chemistry concentrators finished their theses about a month ago.