Think of yourself as a member of a jury, listening to a lawyer who is presenting an opening argument. You'll want to know very soon whether the lawyer believes the accused to be guilty or not guilty, and how the lawyer plans to convince you. Readers of academic essays are like jury members: before they have read too far, they want to know what the essay argues as well as how the writer plans to make the argument. After reading your thesis statement, the reader should think, "This essay is going to try to convince me of something. I'm not convinced yet, but I'm interested to see how I might be."

An effective thesis cannot be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." A thesis is not a topic; nor is it a fact; nor is it an opinion. "Reasons for the fall of communism" is a topic. "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" is a fact known by educated people. "The fall of communism is the best thing that ever happened in Europe" is an opinion. (Superlatives like "the best" almost always lead to trouble. It's impossible to weigh every "thing" that ever happened in Europe. And what about the fall of Hitler? Couldn't that be "the best thing"?)

A good thesis has two parts. It should tell what you plan to argue, and it should "telegraph" how you plan to argue—that is, what particular support for your claim is going where in your essay.

Steps in Constructing a Thesis

First, analyze your primary sources. Look for tension, interest, ambiguity, controversy, and/or complication. Does the author contradict himself or herself? Is a point made and later reversed? What are the deeper implications of the author's argument? Figuring out the why to one or more of these questions, or to related questions, will put you on the path to developing a working thesis. (Without the why, you probably have only come up with an observation—that there are, for instance, many different metaphors in such-and-such a poem—which is not a thesis.)

Once you have a working thesis, write it down. There is nothing as frustrating as hitting on a great idea for a thesis, then forgetting it when you lose concentration. And by writing down your thesis you will be forced to think of it clearly, logically, and concisely. You probably will not be able to write out a final-draft version of your thesis the first time you try, but you'll get yourself on the right track by writing down what you have.

Keep your thesis prominent in your introduction. A good, standard place for your thesis statement is at the end of an introductory paragraph, especially in shorter (5-15 page) essays. Readers are used to finding theses there, so they automatically pay more attention when they read the last sentence of your introduction. Although this is not required in all academic essays, it is a good rule of thumb.

Anticipate the counterarguments. Once you have a working thesis, you should think about what might be said against it. This will help you to refine your thesis, and it will also make you think of the arguments that you'll need to refute later on in your essay. (Every argument has a counterargument. If yours doesn't, then it's not an argument—it may be a fact, or an opinion, but it is not an argument.)

This statement is on its way to being a thesis. However, it is too easy to imagine possible counterarguments. For example, a political observer might believe that Dukakis lost because he suffered from a "soft-on-crime" image. If you complicate your thesis by anticipating the counterargument, you'll strengthen your argument, as shown in the sentence below.

Some Caveats and Some Examples

A thesis is never a question. Readers of academic essays expect to have questions discussed, explored, or even answered. A question ("Why did communism collapse in Eastern Europe?") is not an argument, and without an argument, a thesis is dead in the water.

A thesis is never a list. "For political, economic, social and cultural reasons, communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" does a good job of "telegraphing" the reader what to expect in the essay—a section about political reasons, a section about economic reasons, a section about social reasons, and a section about cultural reasons. However, political, economic, social and cultural reasons are pretty much the only possible reasons why communism could collapse. This sentence lacks tension and doesn't advance an argument. Everyone knows that politics, economics, and culture are important.

A thesis should never be vague, combative or confrontational. An ineffective thesis would be, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because communism is evil." This is hard to argue (evil from whose perspective? what does evil mean?) and it is likely to mark you as moralistic and judgmental rather than rational and thorough. It also may spark a defensive reaction from readers sympathetic to communism. If readers strongly disagree with you right off the bat, they may stop reading.

An effective thesis has a definable, arguable claim. "While cultural forces contributed to the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, the disintegration of economies played the key role in driving its decline" is an effective thesis sentence that "telegraphs," so that the reader expects the essay to have a section about cultural forces and another about the disintegration of economies. This thesis makes a definite, arguable claim: that the disintegration of economies played a more important role than cultural forces in defeating communism in Eastern Europe. The reader would react to this statement by thinking, "Perhaps what the author says is true, but I am not convinced. I want to read further to see how the author argues this claim."

A thesis should be as clear and specific as possible. Avoid overused, general terms and abstractions. For example, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because of the ruling elite's inability to address the economic concerns of the people" is more powerful than "Communism collapsed due to societal discontent."

Copyright 1999, Maxine Rodburg and The Tutors of the Writing Center at Harvard University

How To Write A Dissertation Or Thesis

8 straightforward steps to craft an a-grade dissertation.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

Writing a dissertation or thesis is not a simple task. It takes time, energy and a lot of will power to get you across the finish line. It’s not easy – but it doesn’t necessarily need to be a painful process. If you understand the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis, your research journey will be a lot smoother.

In this post, I’m going to outline the big-picture process of how to write a high-quality dissertation or thesis, without losing your mind along the way. If you’re just starting your research, this post is perfect for you. Alternatively, if you’ve already submitted your proposal, this article which covers how to structure a dissertation might be more helpful.

How To Write A Dissertation: 8 Steps

- Clearly understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is

- Find a unique and valuable research topic

- Craft a convincing research proposal

- Write up a strong introduction chapter

- Review the existing literature and compile a literature review

- Design a rigorous research strategy and undertake your own research

- Present the findings of your research

- Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Step 1: Understand exactly what a dissertation is

This probably sounds like a no-brainer, but all too often, students come to us for help with their research and the underlying issue is that they don’t fully understand what a dissertation (or thesis) actually is.

So, what is a dissertation?

At its simplest, a dissertation or thesis is a formal piece of research , reflecting the standard research process . But what is the standard research process, you ask? The research process involves 4 key steps:

- Ask a very specific, well-articulated question (s) (your research topic)

- See what other researchers have said about it (if they’ve already answered it)

- If they haven’t answered it adequately, undertake your own data collection and analysis in a scientifically rigorous fashion

- Answer your original question(s), based on your analysis findings

In short, the research process is simply about asking and answering questions in a systematic fashion . This probably sounds pretty obvious, but people often think they’ve done “research”, when in fact what they have done is:

- Started with a vague, poorly articulated question

- Not taken the time to see what research has already been done regarding the question

- Collected data and opinions that support their gut and undertaken a flimsy analysis

- Drawn a shaky conclusion, based on that analysis

If you want to see the perfect example of this in action, look out for the next Facebook post where someone claims they’ve done “research”… All too often, people consider reading a few blog posts to constitute research. Its no surprise then that what they end up with is an opinion piece, not research. Okay, okay – I’ll climb off my soapbox now.

The key takeaway here is that a dissertation (or thesis) is a formal piece of research, reflecting the research process. It’s not an opinion piece , nor a place to push your agenda or try to convince someone of your position. Writing a good dissertation involves asking a question and taking a systematic, rigorous approach to answering it.

If you understand this and are comfortable leaving your opinions or preconceived ideas at the door, you’re already off to a good start!

Step 2: Find a unique, valuable research topic

As we saw, the first step of the research process is to ask a specific, well-articulated question. In other words, you need to find a research topic that asks a specific question or set of questions (these are called research questions ). Sounds easy enough, right? All you’ve got to do is identify a question or two and you’ve got a winning research topic. Well, not quite…

A good dissertation or thesis topic has a few important attributes. Specifically, a solid research topic should be:

Let’s take a closer look at these:

Attribute #1: Clear

Your research topic needs to be crystal clear about what you’re planning to research, what you want to know, and within what context. There shouldn’t be any ambiguity or vagueness about what you’ll research.

Here’s an example of a clearly articulated research topic:

An analysis of consumer-based factors influencing organisational trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms.

As you can see in the example, its crystal clear what will be analysed (factors impacting organisational trust), amongst who (consumers) and in what context (British low-cost equity brokerage firms, based online).

Need a helping hand?

Attribute #2: Unique

Your research should be asking a question(s) that hasn’t been asked before, or that hasn’t been asked in a specific context (for example, in a specific country or industry).

For example, sticking organisational trust topic above, it’s quite likely that organisational trust factors in the UK have been investigated before, but the context (online low-cost equity brokerages) could make this research unique. Therefore, the context makes this research original.

One caveat when using context as the basis for originality – you need to have a good reason to suspect that your findings in this context might be different from the existing research – otherwise, there’s no reason to warrant researching it.

Attribute #3: Important

Simply asking a unique or original question is not enough – the question needs to create value. In other words, successfully answering your research questions should provide some value to the field of research or the industry. You can’t research something just to satisfy your curiosity. It needs to make some form of contribution either to research or industry.

For example, researching the factors influencing consumer trust would create value by enabling businesses to tailor their operations and marketing to leverage factors that promote trust. In other words, it would have a clear benefit to industry.

So, how do you go about finding a unique and valuable research topic? We explain that in detail in this video post – How To Find A Research Topic . Yeah, we’ve got you covered 😊

Step 3: Write a convincing research proposal

Once you’ve pinned down a high-quality research topic, the next step is to convince your university to let you research it. No matter how awesome you think your topic is, it still needs to get the rubber stamp before you can move forward with your research. The research proposal is the tool you’ll use for this job.

So, what’s in a research proposal?

The main “job” of a research proposal is to convince your university, advisor or committee that your research topic is worthy of approval. But convince them of what? Well, this varies from university to university, but generally, they want to see that:

- You have a clearly articulated, unique and important topic (this might sound familiar…)

- You’ve done some initial reading of the existing literature relevant to your topic (i.e. a literature review)

- You have a provisional plan in terms of how you will collect data and analyse it (i.e. a methodology)

At the proposal stage, it’s (generally) not expected that you’ve extensively reviewed the existing literature , but you will need to show that you’ve done enough reading to identify a clear gap for original (unique) research. Similarly, they generally don’t expect that you have a rock-solid research methodology mapped out, but you should have an idea of whether you’ll be undertaking qualitative or quantitative analysis , and how you’ll collect your data (we’ll discuss this in more detail later).

Long story short – don’t stress about having every detail of your research meticulously thought out at the proposal stage – this will develop as you progress through your research. However, you do need to show that you’ve “done your homework” and that your research is worthy of approval .

So, how do you go about crafting a high-quality, convincing proposal? We cover that in detail in this video post – How To Write A Top-Class Research Proposal . We’ve also got a video walkthrough of two proposal examples here .

Step 4: Craft a strong introduction chapter

Once your proposal’s been approved, its time to get writing your actual dissertation or thesis! The good news is that if you put the time into crafting a high-quality proposal, you’ve already got a head start on your first three chapters – introduction, literature review and methodology – as you can use your proposal as the basis for these.

Handy sidenote – our free dissertation & thesis template is a great way to speed up your dissertation writing journey.

What’s the introduction chapter all about?

The purpose of the introduction chapter is to set the scene for your research (dare I say, to introduce it…) so that the reader understands what you’ll be researching and why it’s important. In other words, it covers the same ground as the research proposal in that it justifies your research topic.

What goes into the introduction chapter?

This can vary slightly between universities and degrees, but generally, the introduction chapter will include the following:

- A brief background to the study, explaining the overall area of research

- A problem statement , explaining what the problem is with the current state of research (in other words, where the knowledge gap exists)

- Your research questions – in other words, the specific questions your study will seek to answer (based on the knowledge gap)

- The significance of your study – in other words, why it’s important and how its findings will be useful in the world

As you can see, this all about explaining the “what” and the “why” of your research (as opposed to the “how”). So, your introduction chapter is basically the salesman of your study, “selling” your research to the first-time reader and (hopefully) getting them interested to read more.

How do I write the introduction chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this post .

Step 5: Undertake an in-depth literature review

As I mentioned earlier, you’ll need to do some initial review of the literature in Steps 2 and 3 to find your research gap and craft a convincing research proposal – but that’s just scratching the surface. Once you reach the literature review stage of your dissertation or thesis, you need to dig a lot deeper into the existing research and write up a comprehensive literature review chapter.

What’s the literature review all about?

There are two main stages in the literature review process:

Literature Review Step 1: Reading up

The first stage is for you to deep dive into the existing literature (journal articles, textbook chapters, industry reports, etc) to gain an in-depth understanding of the current state of research regarding your topic. While you don’t need to read every single article, you do need to ensure that you cover all literature that is related to your core research questions, and create a comprehensive catalogue of that literature , which you’ll use in the next step.

Reading and digesting all the relevant literature is a time consuming and intellectually demanding process. Many students underestimate just how much work goes into this step, so make sure that you allocate a good amount of time for this when planning out your research. Thankfully, there are ways to fast track the process – be sure to check out this article covering how to read journal articles quickly .

Literature Review Step 2: Writing up

Once you’ve worked through the literature and digested it all, you’ll need to write up your literature review chapter. Many students make the mistake of thinking that the literature review chapter is simply a summary of what other researchers have said. While this is partly true, a literature review is much more than just a summary. To pull off a good literature review chapter, you’ll need to achieve at least 3 things:

- You need to synthesise the existing research , not just summarise it. In other words, you need to show how different pieces of theory fit together, what’s agreed on by researchers, what’s not.

- You need to highlight a research gap that your research is going to fill. In other words, you’ve got to outline the problem so that your research topic can provide a solution.

- You need to use the existing research to inform your methodology and approach to your own research design. For example, you might use questions or Likert scales from previous studies in your your own survey design .

As you can see, a good literature review is more than just a summary of the published research. It’s the foundation on which your own research is built, so it deserves a lot of love and attention. Take the time to craft a comprehensive literature review with a suitable structure .

But, how do I actually write the literature review chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this video post .

Step 6: Carry out your own research

Once you’ve completed your literature review and have a sound understanding of the existing research, its time to develop your own research (finally!). You’ll design this research specifically so that you can find the answers to your unique research question.

There are two steps here – designing your research strategy and executing on it:

1 – Design your research strategy

The first step is to design your research strategy and craft a methodology chapter . I won’t get into the technicalities of the methodology chapter here, but in simple terms, this chapter is about explaining the “how” of your research. If you recall, the introduction and literature review chapters discussed the “what” and the “why”, so it makes sense that the next point to cover is the “how” –that’s what the methodology chapter is all about.

In this section, you’ll need to make firm decisions about your research design. This includes things like:

- Your research philosophy (e.g. positivism or interpretivism )

- Your overall methodology (e.g. qualitative , quantitative or mixed methods)

- Your data collection strategy (e.g. interviews , focus groups, surveys)

- Your data analysis strategy (e.g. content analysis , correlation analysis, regression)

If these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these in plain language in other posts. It’s not essential that you understand the intricacies of research design (yet!). The key takeaway here is that you’ll need to make decisions about how you’ll design your own research, and you’ll need to describe (and justify) your decisions in your methodology chapter.

2 – Execute: Collect and analyse your data

Once you’ve worked out your research design, you’ll put it into action and start collecting your data. This might mean undertaking interviews, hosting an online survey or any other data collection method. Data collection can take quite a bit of time (especially if you host in-person interviews), so be sure to factor sufficient time into your project plan for this. Oftentimes, things don’t go 100% to plan (for example, you don’t get as many survey responses as you hoped for), so bake a little extra time into your budget here.

Once you’ve collected your data, you’ll need to do some data preparation before you can sink your teeth into the analysis. For example:

- If you carry out interviews or focus groups, you’ll need to transcribe your audio data to text (i.e. a Word document).

- If you collect quantitative survey data, you’ll need to clean up your data and get it into the right format for whichever analysis software you use (for example, SPSS, R or STATA).

Once you’ve completed your data prep, you’ll undertake your analysis, using the techniques that you described in your methodology. Depending on what you find in your analysis, you might also do some additional forms of analysis that you hadn’t planned for. For example, you might see something in the data that raises new questions or that requires clarification with further analysis.

The type(s) of analysis that you’ll use depend entirely on the nature of your research and your research questions. For example:

- If your research if exploratory in nature, you’ll often use qualitative analysis techniques .

- If your research is confirmatory in nature, you’ll often use quantitative analysis techniques

- If your research involves a mix of both, you might use a mixed methods approach

Again, if these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these concepts and techniques in other posts. The key takeaway is simply that there’s no “one size fits all” for research design and methodology – it all depends on your topic, your research questions and your data. So, don’t be surprised if your study colleagues take a completely different approach to yours.

Step 7: Present your findings

Once you’ve completed your analysis, it’s time to present your findings (finally!). In a dissertation or thesis, you’ll typically present your findings in two chapters – the results chapter and the discussion chapter .

What’s the difference between the results chapter and the discussion chapter?

While these two chapters are similar, the results chapter generally just presents the processed data neatly and clearly without interpretation, while the discussion chapter explains the story the data are telling – in other words, it provides your interpretation of the results.

For example, if you were researching the factors that influence consumer trust, you might have used a quantitative approach to identify the relationship between potential factors (e.g. perceived integrity and competence of the organisation) and consumer trust. In this case:

- Your results chapter would just present the results of the statistical tests. For example, correlation results or differences between groups. In other words, the processed numbers.

- Your discussion chapter would explain what the numbers mean in relation to your research question(s). For example, Factor 1 has a weak relationship with consumer trust, while Factor 2 has a strong relationship.

Depending on the university and degree, these two chapters (results and discussion) are sometimes merged into one , so be sure to check with your institution what their preference is. Regardless of the chapter structure, this section is about presenting the findings of your research in a clear, easy to understand fashion.

Importantly, your discussion here needs to link back to your research questions (which you outlined in the introduction or literature review chapter). In other words, it needs to answer the key questions you asked (or at least attempt to answer them).

For example, if we look at the sample research topic:

In this case, the discussion section would clearly outline which factors seem to have a noteworthy influence on organisational trust. By doing so, they are answering the overarching question and fulfilling the purpose of the research .

For more information about the results chapter , check out this post for qualitative studies and this post for quantitative studies .

Step 8: The Final Step Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Last but not least, you’ll need to wrap up your research with the conclusion chapter . In this chapter, you’ll bring your research full circle by highlighting the key findings of your study and explaining what the implications of these findings are.

What exactly are key findings? The key findings are those findings which directly relate to your original research questions and overall research objectives (which you discussed in your introduction chapter). The implications, on the other hand, explain what your findings mean for industry, or for research in your area.

Sticking with the consumer trust topic example, the conclusion might look something like this:

Key findings

This study set out to identify which factors influence consumer-based trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms. The results suggest that the following factors have a large impact on consumer trust:

While the following factors have a very limited impact on consumer trust:

Notably, within the 25-30 age groups, Factors E had a noticeably larger impact, which may be explained by…

Implications

The findings having noteworthy implications for British low-cost online equity brokers. Specifically:

The large impact of Factors X and Y implies that brokers need to consider….

The limited impact of Factor E implies that brokers need to…

As you can see, the conclusion chapter is basically explaining the “what” (what your study found) and the “so what?” (what the findings mean for the industry or research). This brings the study full circle and closes off the document.

Let’s recap – how to write a dissertation or thesis

You’re still with me? Impressive! I know that this post was a long one, but hopefully you’ve learnt a thing or two about how to write a dissertation or thesis, and are now better equipped to start your own research.

To recap, the 8 steps to writing a quality dissertation (or thesis) are as follows:

- Understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is – a research project that follows the research process.

- Find a unique (original) and important research topic

- Craft a convincing dissertation or thesis research proposal

- Write a clear, compelling introduction chapter

- Undertake a thorough review of the existing research and write up a literature review

- Undertake your own research

- Present and interpret your findings

Once you’ve wrapped up the core chapters, all that’s typically left is the abstract , reference list and appendices. As always, be sure to check with your university if they have any additional requirements in terms of structure or content.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

20 Comments

thankfull >>>this is very useful

Thank you, it was really helpful

unquestionably, this amazing simplified way of teaching. Really , I couldn’t find in the literature words that fully explicit my great thanks to you. However, I could only say thanks a-lot.

Great to hear that – thanks for the feedback. Good luck writing your dissertation/thesis.

This is the most comprehensive explanation of how to write a dissertation. Many thanks for sharing it free of charge.

Very rich presentation. Thank you

Thanks Derek Jansen|GRADCOACH, I find it very useful guide to arrange my activities and proceed to research!

Thank you so much for such a marvelous teaching .I am so convinced that am going to write a comprehensive and a distinct masters dissertation

It is an amazing comprehensive explanation

This was straightforward. Thank you!

I can say that your explanations are simple and enlightening – understanding what you have done here is easy for me. Could you write more about the different types of research methods specific to the three methodologies: quan, qual and MM. I look forward to interacting with this website more in the future.

Thanks for the feedback and suggestions 🙂

Hello, your write ups is quite educative. However, l have challenges in going about my research questions which is below; *Building the enablers of organisational growth through effective governance and purposeful leadership.*

Very educating.

Just listening to the name of the dissertation makes the student nervous. As writing a top-quality dissertation is a difficult task as it is a lengthy topic, requires a lot of research and understanding and is usually around 10,000 to 15000 words. Sometimes due to studies, unbalanced workload or lack of research and writing skill students look for dissertation submission from professional writers.

Thank you 💕😊 very much. I was confused but your comprehensive explanation has cleared my doubts of ever presenting a good thesis. Thank you.

thank you so much, that was so useful

Hi. Where is the excel spread sheet ark?

could you please help me look at your thesis paper to enable me to do the portion that has to do with the specification

my topic is “the impact of domestic revenue mobilization.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Joseph Wakim PhD Thesis Defense

Physical models of chromatin organization and epigenetic domain stability, event details:, this event is open to:.

Joseph Wakim PhD Candidate Chemical Engineering Academic advisor: Professor Andrew Spakowitz

Abstract: Physical Models of Chromatin Organization and Epigenetic Domain Stability

Although there are about 200 distinct cell types in the human body, all somatic cells in an individual share the same genetic code. The spatial organization of DNA plays an important role in regulating gene expression, enabling broad cellular diversity. In each cell, approximately two meters of DNA is organized into a cell nucleus only about 10 microns in diameter. This high degree of compaction is achieved by wrapping DNA tightly around histone octamers to form units called nucleosomes. These nucleosomes are arranged into tight chains called chromatin. Chemical modifications along the chromatin fiber, known as epigenetic marks, cause chromatin to phase separate into loose “euchromatin” and dense “heterochromatin.” Genes in euchromatin are accessible to transcriptional machinery and are more likely to be expressed, while those in heterochromatin are inaccessible and tend to be suppressed. Dysregulation of 3D chromatin architecture has been implicated in several age-related disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease and cancer.

During this presentation, I will explore how patterns of epigenetic marks and conditions in the nuclear environment dictate chromatin organization. I will begin by focusing on the transcriptionally active euchromatic phase. Despite its overall accessibility, euchromatin is characterized by isolated clusters of nucleosomes, which can affect local transcription levels. I will introduce a model that explains how nucleosome geometry and positioning are affected by trace levels of epigenetic marks in euchromatin, causing clusters to form along the chromatin fiber. Using this model, I will evaluate the physical factors dictating cluster sizes.

I will then introduce a model that explains how interacting “reader proteins,” which preferentially bind specific epigenetic marks, affect large-scale chromatin organization and contribute to the segregation of euchromatic and heterochromatic phases. I will demonstrate that direct interactions between different reader proteins are not required to facilitate their crosstalk. Rather, due to the shared scaffold to which reader proteins bind, chromatin condensation by one reader protein may indirectly support the binding of another. According to our model, if different reader proteins compete for binding sites along the chromatin fiber, large-scale chromatin organization can be remodeled in response to changes in reader protein concentrations. By characterizing modes of epigenetic crosstalk, I will demonstrate the interdependence of multiple epigenetic marks on the spatial organization of DNA.

Overall, my presentation will leverage principles from polymer theory, statistical mechanics, and molecular biology to identify factors contributing to the physical regulation of gene expression. The projects I will discuss offer a framework for evaluating how changes in epigenetic patterning and the nuclear environment affect local chromatin accessibility, which is implicated in cell differentiation and age-related diseases.

Related Topics

Explore more events, sevahn vorperian phd thesis defense, benny freeman, four l.a.s.e.r. talks: human embodiment, 3d printing, ocean health, chinese computing".

Skip to Content

Zach Schiffman wins Colorado Three Minute Thesis competition

CU Boulder doctoral student takes first prize in state 3MT competition for presentation on the urea molecule

Zach Schiffman (right) accepting a certificate recognizing his accomplishment.

Zach Schiffman, a doctoral candidate in chemistry, beat out Colorado’s other universities to win the state Three Minute Thesis (3MT) competition last month. He won with his presentation, “The Urea Molecule: From Fertilizer . . . to Climate Change?”

This is the second win for Schiffman, who took first prize in the Graduate School’s annual 3MT competition earlier this year. As part of his winnings, he was then invited to represent the university at both the regional (Western Region of Graduate Schools) and state (Colorado Council of Graduate Schools) competitions.

The 3MT event, which began at the University of Queensland in 2008, challenges graduate students to describe their research within three minutes to a general audience. To prepare, CU Boulder graduate students participate in a series of workshops focusing on storytelling, writing, presentation skills and improvisation comedy techniques. The Graduate School then holds a preliminary competition to whittle down the competition to ten finalists, who participate in the final competition at the beginning of February.

More information about the 3MT competition, including how to get involved in the 2024–25 school year, is available on the 3MT webpage .

- Spring 2024

- Three Minute Thesis

Raft of senior concentrators awarded prestigious thesis prizes

We are very proud to announce that eight thesis prizes have been awarded to our senior concentrators for their outstanding scholarly research.

The Hoopes Prize – funded by the estate of Thomas T. Hoopes, class of 1919, and overseen by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) – was awarded to Amen Gashaw, Fred Larsen, and Jaya Nayar, alongside 73 fellow Harvard undergraduate students.

The prize was established for the purpose of “promoting, improving, and enhancing the quality of education” as well as encouraging “excellence in the art of teaching”. As a result, student winners are awarded $5,000 and their faculty advisors are awarded $2,000. Each winning thesis is bound and available in Lamont Library for two years before being sent to the student.

Speaking to The Harvard Crimson , Susan L. Lively, secretary of the FAS, said: “The Hoopes Prize represents Harvard College at its very best. The range and quality of this year’s winning projects are a testament to the hard work and talent of both the students who produced the theses and the faculty who advised them”. Read the full article here .

Fred Larsen also went on to win the 2023–2024 Seymour E. and Ruth B. Harris Prize for Honors Thesis in the Social Sciences for his essay: “A Musical Politics” .

Seymour Harris was a Professor of Economics from 1946 to 1957 and the Lucius N. Littauer Professor of Political Economy from 1957 until his retirement in 1964. Through a bequest, the Seymour E. and Ruth B. Harris prizes are awarded to “two Harvard College seniors who write outstanding Honors Theses, one in Economics and the other in another Social Science”, with a prize payment of $3,500.

Three of our senior concentrators were recipients of the African and African American Studies (AAAS) department awards.

Nia Warren won the Kwame Anthony Appiah Prize for her paper, titled “SHE HAD TWO CHOICES: HOMELESSNESS OR HARASSMENT: An Intersectional Study of Underreporting of Sexual Harassment in Housing” .

Awarded to the most outstanding thesis relating to the African diaspora, the prize was established in 2005 by Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Henry Finder and named after a distinguished colleague who served in the AAAS Department from 1991-2002.

Nia was also awarded the Kathryn Ann Huggins Prize alongside classmate Ebony Smith, whose paper “ Consuming Chocolate and Blackness: Reparative Imagery to Address the Triple Oppression of Black Women in the Cocoa and Chocolate Industry ” was highly praised.

Awarded to the most outstanding theses relating to African American life, history, or culture, the prize was established in 1987 by Kathryn Huggins’s brother, the late Professor Nathan I. Huggins, W. E. B. Du Bois Professor of History and Afro-American Studies. It aims to remember Kathryn by bringing attention to the values she held most dear: personal commitment and dedication to study, humanism through the study of other peoples and cultures, and respect for the marginalized and dispossessed.

The final AAAS Department award was won by Jolly Rop, with her essay on “ The Politics of Tea & Robots in Western Kenya: Implications for Our Understanding of the Political Impact of Automation ” earning the Philippe Wamba Prize for best senior thesis in African Studies.

A 1993 graduate of Harvard College, Philippe Wamba profoundly impacted his fellow students and the faculty of the African and African American Studies Department in his short life. Following his graduation, he soon returned to Harvard University where he became the Editor-in-Chief of Africana.com. Known for his remarkable personality as well as his outstanding intellectual capability, Philippe Wamba’s life is celebrated through this prize.

The final prize for the 2023-24 graduating class is from the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS), which awarded senior concentrator Jorge Ruiz the James R. and Isabel D. Hammond Thesis Prize on Spanish-speaking Latin American Studies for his thesis, “ Old Parties and New Cleavages: Puerto Rico’s Emerging Multi-Party System ” . Read the full article here .

We’re very proud of Amen, Fred, Jaya, Nia, Ebony, Jolly, and Jorge for their hard work and dedication toward producing a fantastic senior thesis.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Chicago teen earns doctorate at 17 years old from Arizona State

Dorothy Jean Tillman II spoke at her commencement this month at Arizona State University. She successfully defended her dissertation to earn a doctorate in integrated behavioral health last December.

Copyright © 2024 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

- Apply to UW

- Programs & Majors

- Cost & Financial Aid

- Current Students

- UW Libraries

- Degree Plans & Courses

- Advising & Career Services

- UW College of Law

- Honors College

- Academic Affairs

- Geological Museum

- All Colleges

- Campus Recreation

- Campus Maps

- Housing & Dining

- Transit & Parking

- University Store

- Student Organizations

- Campus Activities

- Campus Safety

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- Research & Economic Dev.

- Wyoming INBRE

- Neuroscience Center

- Technology Business Center

- National Parks Service

- Research Production Center

- Supercomputing

- Water Research

- WY EPSCoR/IDeA

- American Heritage Center

- Where We Shine

- About Laramie

- Student Stories

- Campus Fact Book

- UWYO Magazine

- Marketing & Brand Center

- Administrative Resources

- Strategic Plan

- +Application Login

- Indigenous youth camps

“When the Elder prayed, the buffalo appeared to listen in” – Janna Black organizes Indigenous youth camp as thesis project

Published May 03, 2024 By DeeDee DuPlessis, photos: London Bernier/GYC

In September 2023, the Indigenous Youth Culture and Climate Day camps started with a memorable moment: An elder was saying a prayer in Shoshone. She paused, looked up and said a buffalo had joined to listen and recognized the Shoshone language. Indeed, a buffalo was perched up on the hillside. When the prayer was finished the buffalo came down toward the camp and to the river. The 41 fifth graders from Wyoming Indian Elementary School, who had assembled for a day at the Shoshone Buffalo herd within the Wind River Indian Reservation, were impressed and couldn’t stop talking about it. Hearing this story from camp organizer Janna Black during her thesis defense is enough to give anyone goosebumps.

More Than One Way of Knowing

As part of her Master of Science in Environment, Natural Resources & Society degree on the Plan B track, Black planned and organized three-day camps at the Shoshone buffalo herd pasture for grades 5, 8 and 11-12, respectively. Plan B studies replace a traditional thesis with a more flexible project.

Black, who spent several years as an organic farmer and homeschooling mother in Washington state before she came to University of Wyoming in 2022, says her perspective is shaped by a holistic view of ecology where everything is interconnected. She seeks to combine, or as she expresses it, “braid together,” Indigenous, local, and scientific knowledge systems to generate new insights and innovations.

This approach of knowledge co-production is also at the heart of UWyo’s WyACT five-year project on the effects of the changing climate on Wyoming’s waters. Black’s graduate advisor Corinne Knapp, professor at the Haub School of ENR, is also a co-PI of WyACT. She feels that projects like this complement climate-change research seamlessly: “The Wind River that gave today’s Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho reservation its name, is one of the headwaters rivers of the project, and the Tribes of Wyoming will feel the effect of environmental changes intensely due to their close connection with the land.”

The core planning team for the Indigenous Youth Camps (from left): Wes Martel, Janna Black, Colleen Friday, and Signa McAdams

Janna Black wanted to help strengthen sense of place rooted in culture through intergenerational land-based learning. Wes Martel, Senior Wind River Conservation Associate with the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, was a key member of her planning team. He agrees: “I always talk about strengthening our families and our communities, and this camp was a good start for that.”

A day in the outside classroom

So, how did the day camp go about achieving this? Near Kinnear, where the buffalo heard roams, a teepee and nine booths were set up. Student groups took turns attending the stations for 20-minute hands-on “lessons”. They learned new Arapaho and Shoshone words, got to see and touch many cultural objects, furs and bones, and learned Arapaho hand games. Plants like the landscape-defining sagebrush played a large role in the lessons, as did animals, first and foremost the buffalo, whose many uses and cultural significance was stressed at several stations. At the camp itself, the buffalo provided nourishment: In the form of buffalo burgers that the students helped prepare!

Not all activities were stationary – students walked around the landscape identifying plants and climbed a vantage point to spot signs of drought across the river. Immersed in the beauty and sacredness of the land, the next generation of leaders got some impulses to think about their future.

Youth camp participants were able to interact with a variety of animal furs, bones, and skulls

There were only four months to plan the camps with a core team of four people. Black cooperated with the High Plains American Indian Research Institute (HPAIRI) at UWyo, which is working out a process for the University and the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone people to work together. Having a process is helpful, but: “Building relationships is very important” stresses Black. “It is important to have reciprocal relationships based on trust, sense of belonging, and accountability”.

Building relationships and trust takes time and effort. But the results were well worth it. Students expressed increased knowledge about the land and their culture and came up with many actions to conserve water and protect the environment.

Blueprint for Land-Based Learning

The success of the camp can also be measured by the fact that the second edition is slated for June. And the concept does not have to be confined to the Wind River Indian Reservation. Black: “While there were many elements specific to the location, the planning process could be a blueprint for other Tribes and regions.” She describes the steps for planning and holding the camp in great detail in an illustrated brochure available as PDF and a limited number of printed copies.

Now that she has graduated, what is next for Janna Black? “I am the new Tribal Climate Resilience Liaison working for the Great Plains Tribal Water Alliance and closely with the North Central Climate Adaptation Science Center. She will be Working to connect resources to Tribal Nations in climate adaptation efforts in the north central region which consists of 32 federally recognized Tribes from Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas. “I am looking forward to helping Tribal Nations build climate resiliency and sustainability for many years to come.”

Camps were funded through a Western Water Assessment (a NOAA-funded CAP RISA) small grants opportunity and Janna's time was funded through a Kemmerer Fellowship and the WyACT Project.

* High Plains American Indian Research Institute (HPAIRI)

* What is a Plan B thesis?

* To obtain a copy of the planning booklet, please contact Janna Black

- EXPLORE Random Article

How to Write Acknowledgements for a Thesis

Last Updated: January 19, 2023

This article was co-authored by wikiHow Staff . Our trained team of editors and researchers validate articles for accuracy and comprehensiveness. wikiHow's Content Management Team carefully monitors the work from our editorial staff to ensure that each article is backed by trusted research and meets our high quality standards. This article has been viewed 18,946 times.

The acknowledgements section of your thesis provides you with an opportunity to thank anyone who supported you during the research and writing process. Before writing your acknowledgements, it's helpful to first choose who exactly you want to include. Then, you can construct your acknowledgements using the right tone and language to properly thank those who contributed to and supported your work in both academic and personal ways.

Choosing Who to Thank

- If you choose not to include funders or advisors in your acknowledgements, you could risk insulting them. This could prevent them from working with you in the future, and could even lead them to refuse to write you any letters of recommendation.

- In many cases, you'll have 1 academic advisor who is the chair of your thesis review committee, and then 2 or 3 additional faculty members who serve as secondary co-advisors. If this is the case, make sure that you include your secondary co-advisors in addition to your chair.

- This could be other faculty members, fellow students, research assistants, archivists, librarians, or other institutional personnel who assisted in the research and writing process in any way.

- Professional contributors could include people who read and reviewed your work, helped facilitate research, or talked through challenging concepts and ideas with you throughout the thesis-writing process.

- For example, while you may be close with and enjoy seeing a particular cousin or childhood friend, if they weren't actively supporting you during this time, you likely won't have space to include them in your acknowledgements.

- If a well-known academic in your field was particularly inspirational but did not read your work, you can also mention them in your acknowledgements if you have space to do so.

- If your faith is particularly important to you, you could also consider dedicating your thesis to the higher power you believe in. This could be done within the acknowledgments, or on a separate dedication page depending on your institution's formatting preferences.

- If someone was a great influence in your life but didn't contribute to your thesis directly, you could consider writing them a personal letter or email instead of including them in your acknowledgements.

Constructing Your Acknowledgements

- While there's no set rule about acknowledgement order, in general, funders are thanked first for their financial support, then academic supervisors, followed by other academics and professionals, as well as colleagues and classmates.

- If you're afraid that your personal supporters might be offended by being acknowledged last, you could explain to them that this is a professional courtesy.

- Since your academic advisor was likely a big part of your research and writing process, you'll likely want to expand on how they helped you. For example, you could write, “I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Timothy Kelly, for his guidance and prompt feedback throughout this process.”

- In contrast, you can include only first names for your personal acknowledgements if you choose.

Using the Right Tone and Language

- If you focus on your own accomplishments too much, you could risk coming off as a bit smug. Instead, let the quality of your work speak for itself and use the acknowledgements to focus on others.

- This is particularly important to keep in mind when you thank your academic peers or faculty members that you've developed a personal relationship with, as it can be tempting to write too casually in these instances. [16] X Research source

- For example, to thank your advisor, you could write, “I could not have completed this work without the unwavering support of my chair, Dr. Sherre McWhorter. Dr. McWhorter, your patience and guidance made this work possible.”

- If your parents provided substantial support for you during this process, thank them in a personal manner by saying something like, “It is impossible to extend enough thanks to my family, especially my parents, who gave me the encouragement I needed throughout this process.”

- Instead of naming each of your friends individually, you could try thanking them collectively in a more casual manner. For example, you could write, “To my friends, this would have been a much more difficult feat without you. Thank you all for your unwavering support and for reminding me to take breaks and have fun when I’ve been stressed out.”

- If you want to thank someone for their support in a more emotional, personal manner, try thanking them in person or with a handwritten letter.

Expert Q&A

You might also like.

- ↑ https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/acknowledgements/

- ↑ https://www.phdstudent.com/Writing-Tips/writing-acknowledgements-your-personal-gratitude

- ↑ Jeremiah Kaplan. Research & Training Specialist. Expert Interview. 2 September 2021.

- ↑ https://elc.polyu.edu.hk/FYP/html/ack.htm

About this article

Did this article help you?

- About wikiHow

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

May 21, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

New thesis shows Lynch syndrome should be seen as a common condition

by Karolinska Institutet

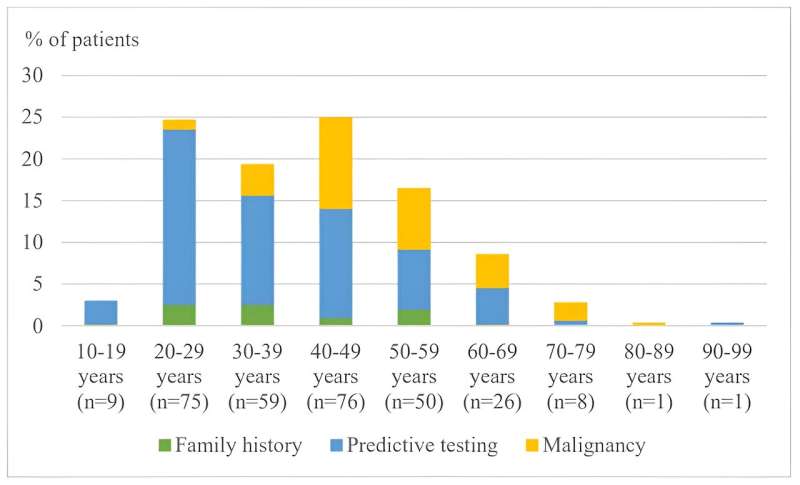

Sophie Walton Bernstedt from the Gastroenterology and Rheumatology Unit at the Department of Medicine, Huddinge (MedH), is defending her thesis "Risk factors for colorectal cancer and the impact on life in Lynch syndrome," on 24 May, 2024. The main supervisor is Ann-Sofie Backman (MedH).

"We have investigated various risk factors associated with the development of colorectal cancer in Lynch syndrome and what it is like for these patients to live with a greatly increased cancer risk," says Walton Bernstedt.

"There is likely still a large number of patients yet to be identified with Lynch syndrome. It is necessary to identify these patients in time in order to prevent and detect early stage cancer by preventive procedures.

"By implementing routines in follow-up services for this group of patients it is possible to create optimal conditions for early detection. These routines include bowel preparation , but also the quality of the procedure, adaptation to genetic risk but also accommodating psychosocial needs among patients.

"Lynch syndrome no longer should be considered a rare condition. By increasing the knowledge of hereditary cancer in the public we hope to increase the efficiency of cancer preventive measures ."

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Regular fish oil supplement use might increase first-time heart disease and stroke risk

2 hours ago

Pedestrians may be twice as likely to be hit by electric/hybrid cars as petrol/diesel ones

Study finds jaboticaba peel reduces inflammation and controls blood sugar in people with metabolic syndrome

3 hours ago

Study reveals how extremely rare immune cells predict how well treatments work for recurrent hives

5 hours ago

Researchers find connection between PFAS exposure in men and the health of their offspring

Researchers develop new tool for better classification of inherited disease-causing variants

Specialized weight navigation program shows higher use of evidence-based treatments, more weight lost than usual care

Exercise bouts could improve efficacy of cancer drug

6 hours ago

Drug-like inhibitor shows promise in preventing flu

Scientists discover a novel way of activating muscle cells' natural defenses against cancer using magnetic pulses

Related stories.

New gene markers detect Lynch syndrome-associated colorectal cancer

Sep 20, 2023

Daily aspirin reduces bowel cancer risk in people with Lynch syndrome

Aug 5, 2019

Lynch syndrome found to be associated with more types of cancers

Jun 4, 2018

Hereditary colon cancer more common in Indonesia, new study finds

Jan 5, 2022

New cancer screening study could affect treatment for thousands in the UK

Sep 18, 2020

Increasing the age limit for Lynch syndrome genetic testing may save lives

May 29, 2017

Recommended for you

Cancer drug shows powerful anti-tumor activity in animal models of several different tumor types

7 hours ago

Study shows drug helps reprogram macrophage immune cells, suppress prostate and bladder tumor growth

9 hours ago

How immune cells recognize the abnormal metabolism of cancer cells

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Medical Xpress in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write a Research Essay

Last Updated: January 12, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Michelle Golden, PhD . Michelle Golden is an English teacher in Athens, Georgia. She received her MA in Language Arts Teacher Education in 2008 and received her PhD in English from Georgia State University in 2015. There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 385,089 times.

Research essays are extremely common assignments in high school, college, and graduate school, and are not unheard of in middle school. If you are a student, chances are you will sooner or later be faced with the task of researching a topic and writing a paper about it. Knowing how to efficiently and successfully do simple research, synthesize information, and clearly present it in essay form will save you many hours and a lot of frustration.

Researching a Topic

- Be sure to stay within the guidelines you are given by your teacher or professor. For example, if you are free to choose a topic but the general theme must fall under human biology, do not write your essay on plant photosynthesis.

- Stick with topics that are not overly complicated, especially if the subject is not something you plan to continue studying. There's no need to make things harder on yourself!

- Specialty books; these can be found at your local public or school library. A book published on your topic is a great resource and will likely be one of your most reliable options for finding quality information. They also contain lists of references where you can look for more information.

- Academic journals; these are periodicals devoted to scholarly research on a specific field of study. Articles in academic journals are written by experts in that field and scrutinized by other professionals to ensure their accuracy. These are great options if you need to find detailed, sophisticated information on your topic; avoid these if you are only writing a general overview.

- Online encyclopedias; the most reliable information on the internet can be found in online encyclopedias like Encyclopedia.com and Britannica.com. While online wikis can be very helpful, they sometimes contain unverified information that you should probably not rely upon as your primary resources.

- Expert interviews; if possible, interview an expert in the subject of your research. Experts can be professionals working in the field you are studying, professors with advanced degrees in the subject of interest, etc.

- Organize your notes by sub-topic to keep them orderly and so you can easily find references when you are writing.

- If you are using books or physical copies of magazines or journals, use sticky tabs to mark pages or paragraphs where you found useful information. You might even want to number these tabs to correspond with numbers on your note sheet for easy reference.

- By keeping your notes brief and simple, you can make them easier to understand and reference while writing. Don't make your notes so long and detailed that they essentially copy what's already written in your sources, as this won't be helpful to you.

- Sometimes the objective of your research will be obvious to you before you even begin researching the topic; other times, you may have to do a bit of reading before you can determine the direction you want your essay to take.

- If you have an objective in mind from the start, you can incorporate this into online searches about your topic in order to find the most relevant resources. For example, if your objective is to outline the environmental hazards of hydraulic fracturing practices, search for that exact phrase rather than just "hydraulic fracturing."

- Avoid asking your teacher to give you a topic. Unless your topic was assigned to you in the first place, part of the assignment is for you to choose a topic relevant to the broader theme of the class or unit. By asking your teacher to do this for you, you risk admitting laziness or incompetence.

- If you have a few topics in mind but are not sure how to develop objectives for some of them, your teacher can help with this. Plan to discuss your options with your teacher and come to a decision yourself rather than having him or her choose the topic for you from several options.

Organizing your Essay

- Consider what background information is necessary to contextualize your research topic. What questions might the reader have right out of the gate? How do you want the reader to think about the topic? Answering these kinds of questions can help you figure out how to set up your argument.

- Match your paper sections to the objective(s) of your writing. For example, if you are trying to present two sides of a debate, create a section for each and then divide them up according to the aspects of each argument you want to address.

- An outline can be as detailed or general as you want, so long as it helps you figure out how to construct the essay. Some people like to include a few sentences under each heading in their outline to create a sort of "mini-essay" before they begin writing. Others find that a simple ordered list of topics is sufficient. Do whatever works best for you.

- If you have time, write your outline a day or two before you start writing and come back to it several times. This will give you an opportunity to think about how the pieces of your essay will best fit together. Rearrange things in your outline as many times as you want until you have a structure you are happy with.

- Style guides tell you exactly how to quote passages, cite references, construct works cited sections, etc. If you are assigned a specific format, you must take care to adhere to guidelines for text formatting and citations.

- Some computer programs (such as EndNote) allow you to construct a library of resources which you can then set to a specific format type; then you can automatically insert in-text citations from your library and populate a references section at the end of the document. This is an easy way to make sure your citations match your assigned style format.

- You may wish to start by simply assigning yourself a certain number of pages per day. Divide the number of pages you are required to write by the number of days you have to finish the essay; this is the number of pages (minimum) that you must complete each day in order to pace yourself evenly.

- If possible, leave a buffer of at least one day between finishing your paper and the due date. This will allow you to review your finished product and edit it for errors. This will also help in case something comes up that slows your writing progress.

Writing your Essay

- Keep your introduction relatively short. For most papers, one or two paragraphs will suffice. For really long essays, you may need to expand this.

- Don't assume your reader already knows the basics of the topic unless it truly is a matter of common knowledge. For example, you probably don't need to explain in your introduction what biology is, but you should define less general terms such as "eukaryote" or "polypeptide chain."

- You may need to include a special section at the beginning of the essay body for background information on your topic. Alternatively, you can consider moving this to the introductory section, but only if your essay is short and only minimal background discussion is needed.

- This is the part of your paper where organization and structure are most important. Arrange sections within the body so that they flow logically and the reader is introduced to ideas and sub-topics before they are discussed further.

- Depending upon the length and detail of your paper, the end of the body might contain a discussion of findings. This kind of section serves to wrap up your main findings but does not explicitly state your conclusions (which should come in the final section of the essay).

- Avoid repetition in the essay body. Keep your writing concise, yet with sufficient detail to address your objective(s) or research question(s).

- Always use quotation marks when using exact quotes from another source. If someone already said or wrote the words you are using, you must quote them this way! Place your in-text citation at the end of the quote.

- To include someone else's ideas in your essay without directly quoting them, you can restate the information in your own words; this is called paraphrasing. Although this does not require quotation marks, it should still be accompanied by an in-text citation.

- Except for very long essays, keep your conclusion short and to the point. You should aim for one or two paragraphs, if possible.

- Conclusions should directly correspond to research discussed in the essay body. In other words, make sure your conclusions logically connect to the rest of your essay and provide explanations when necessary.

- If your topic is complex and involves lots of details, you should consider including a brief summary of the main points of your research in your conclusion.

- Making changes to the discussion and conclusion sections instead of the introduction often requires a less extensive rewrite. Doing this also prevents you from removing anything from the beginning of your essay that could accidentally make subsequent portions of your writing seem out of place.

- It is okay to revise your thesis once you've finished the first draft of your essay! People's views often change once they've done research on a topic. Just make sure you don't end up straying too far from your assigned topic if you do this.

- You don't necessarily need to wait until you've finished your entire draft to do this step. In fact, it is a good idea to revisit your thesis regularly as you write. This can save you a lot of time in the end by helping you keep your essay content on track.

- Computer software such as EndNote is available for making citation organization as easy and quick as possible. You can create a reference library and link it to your document, adding in-text citations as you write; the program creates a formatted works cited section at the end of your document.

- Be aware of the formatting requirements of your chosen style guide for works cited sections and in-text citations. Reference library programs like EndNote have hundreds of pre-loaded formats to choose from.

- Create a catchy title. Waiting until you have finished your essay before choosing a title ensures that it will closely match the content of your essay. Research papers don't always take on the shape we expect them to, and it's easier to match your title to your essay than vice-versa.

- Read through your paper to identify and rework sentences or paragraphs that are confusing or unclear. Each section of your paper should have a clear focus and purpose; if any of yours seem not to meet these expectations, either rewrite or discard them.

- Review your works cited section (at the end of your essay) to ensure that it conforms to the standards of your chosen or assigned style format. You should at least make sure that the style is consistent throughout this section.

- Run a spell checker on your entire document to catch any spelling or grammar mistakes you may not have noticed during your read-through. All modern word processing programs include this function.

- Note that revising your draft is not the same as proofreading it. Revisions are done to make sure the content and substantive ideas are solid; editing is done to check for spelling and grammar errors. Revisions are arguably a more important part of writing a good paper.

- You may want to have a friend, classmate, or family member read your first draft and give you feedback. This can be immensely helpful when trying to decide how to improve upon your first version of the essay.

- Except in extreme cases, avoid a complete rewrite of your first draft. This will most likely be counterproductive and will waste a lot of time. Your first draft is probably already pretty good -- it likely just needs some tweaking before it is ready to submit.

Community Q&A

- Avoid use of the word "I" in research essay writing, even when conveying your personal opinion about a subject. This makes your writing sound biased and narrow in scope. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Even if there is a minimum number of paragraphs, always do 3 or 4 more paragraphs more than needed, so you can always get a good grade. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Never plagiarize the work of others! Passing off others' writing as your own can land you in a lot of trouble and is usually grounds for failing an assignment or class. Thanks Helpful 12 Not Helpful 1

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/research_papers/choosing_a_topic.html

- ↑ https://libguides.mit.edu/select-topic

- ↑ https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/research-objectives

- ↑ https://www.hunter.cuny.edu/rwc/handouts/the-writing-process-1/organization/Organizing-an-Essay

- ↑ https://www.lynchburg.edu/academics/writing-center/wilmer-writing-center-online-writing-lab/the-writing-process/organizing-your-paper/

- ↑ https://www.mla.org/MLA-Style

- ↑ http://www.apastyle.org/

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/PlanResearchPaper.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa6_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/in_text_citations_the_basics.html

- ↑ https://opentextbc.ca/writingforsuccess/chapter/chapter-12-peer-review-and-final-revisions/

- ↑ https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/wrd/back-matter/creating-a-works-cited-page/

About This Article

The best way to write a research essay is to find sources, like specialty books, academic journals, and online encyclopedias, about your topic. Take notes as you research, and make sure you note which page and book you got your notes from. Create an outline for the paper that details your argument, various sections, and primary points for each section. Then, write an introduction, build the body of the essay, and state your conclusion. Cite your sources along the way, and follow the assigned format, like APA or MLA, if applicable. To learn more from our co-author with an English Ph.D. about how to choose a thesis statement for your research paper, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Nov 18, 2018

Did this article help you?

Jun 11, 2017

Christina Wonodi

Oct 12, 2016

Caroline Scott

Jan 28, 2017

Fhatuwani Musinyali

Mar 14, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

Mom delivers baby in car hours before defending her Rutgers doctoral thesis

- Updated: May. 08, 2024, 3:05 p.m. |

- Published: May. 08, 2024, 11:30 a.m.

Tamiah Brevard-Rodriguez delivered her son, Enzo, hours before defending her dissertation at the Rutgers-New Brunswick Graduate School of Education. Nick Romanenko/Rutgers University

- Tina Kelley | NJ Advance Media for NJ.com

Giving birth and defending a doctoral dissertation could easily be considered among the most stressful items on a bucket list. For Tamiah Brevard-Rodriguez, it was all in a day’s work. One day’s work.

She even grabbed a shower in between.

On March 24, Brevard-Rodriguez, director of Aresty Research Center at Rutgers University, was finishing up preparations for her doctoral defense the next day. Eight months pregnant with her second child, she didn’t feel terrific, but she persisted.

She was trying to hone down to 20 minutes her remarks on “The Beauty Performances of Black College Women: A Narrative Inquiry Study Exploring the Realities of Race, Respectability, and Beauty Standards on a Historically White Campus.” The Zoom link had gone out to family, friends, and colleagues for the defense, scheduled for 1 p.m. the next day.

“Operation Dissertation before Baby,” as she called it, was a go.

But at 2:15 a.m. on March 25 her water broke, a month and a day early.

As the contractions came closer and closer, her wife drove her down the Garden State Parkway, trying to get to Hackensack Meridian Mountainside Medical Center in Montclair before Baby Enzo showed up.

But the baby was faster than a speeding Maserati and arrived in the front seat at 5:55 a.m., after just three pushes. He weighed in at 5-pounds 12-ounces, 19 inches long, and in perfect health for a baby four weeks early.

“I did have to detail her car afterward,” the new mom said of her wife.

Brevard-Rodriguez was feeling so good after the birth that she decided against asking to reschedule her thesis defense.

“I had more than enough time to regroup, shower, eat and proceed with the dissertation,” she said. She had a quick nap, too. The doctors and nurses supported her decision and made sure she had access to reliable wifi at the hospital.