- my research

- contributions and comments

- connecting chapters/chapter introductions

Writing a thesis, or indeed an academic book, means constructing an extended argument. One common problem in writing a very long text is that it’s not hard in 80,000 to 100,000 words for the reader to get lost in between chapters – they aren’t sure of the connection of one to the other and of how they work together to advance the case being made, move by move. And sometimes the writer can get lost too! That’s because chapters are often written in a different order to the order in which they are read, and sometimes they are written at very different times. Of course, sometimes the text is written straight through. But whatever the circumstances, it’s easy for both reader and writer to get lost in the overall argument because there is just soooo much detail to cover.

Here is one way to address the getting lost problem and one that many thesis writers find helpful. Confident and clever writers will find their own way to connect chapters together, but if you’re feeling a bit stuck this will help. It’s just a simple frame to use at the beginning of each new chapter. The frame – link, focus, overview – can be used for writing the first draft of the whole text. Because it’s a bit formulaic, it’s helpful to play with it on the second and third drafts so it reads more easily. But even when playing with it, keep the three moves because this is a good way to keep yourself as writer, and the reader, on track.

Paragraph One: LINK Make a connection to what has immediately gone before. Recap the last chapter. In the last chapter I showed that… Having argued in the previous chapter that… As a result of x, which I established in the last chapter….. It is also possible to make a link between this chapter and the whole argument… The first step in answering my research question (repeat question) .. was to.. . In the last chapter I …

Paragraph Two: FOCUS Now focus the reader’s attention on what this chapter is specifically going to do and why it is important. In this chapter I will examine.. I will present… I will report … This is crucial in (aim of thesis/research question) in order to….

Paragraph Three: OVERVIEW The third paragraph simply outlines the way that you are going to achieve the aim spelled out in the previous paragraph. It’s really just a statement of the contents in the order that the reader will encounter them. It is important to state these not simply as topics, but actually how they build up the internal chapter argument… I will begin by examining the definitions of, then move to seeing how these were applied… I first of all explain my orientation to the research process, positioning myself as a critical scholar.. I then explain the methodology that I used in the research, arguing that ethnography was the most suitable approach to provide answers to the question of…

Now, as I said, this is pretty mechanical and it doesn’t make for riveting reading. It’s meant for conventional theses and not those that break the mould. However, the bottom line is that it’s better to be dull and establish coherence and flow between chapters, than to have the reader, particularly if it’s your supervisor or the examiner, wondering what’s going on and how what they are now reading links back to what has gone before, and what the chapter is going to do. And if you’re the writer, it really does help keep you on the straight and narrow.

This post is the first of a four part series suggesting one strategy for achieving flow. Read the rest here , here and here.

Share this:

About pat thomson

18 responses to connecting chapters/chapter introductions.

‘Mechanical’ approaches to specific aspects of writing can be life savers, both for the writer and the reader. Thanks for sharing that way of linking chapters/chapter introductions. I’ll definitely keep that in mind for an upcoming book project (as the on I am in the process of writing right now is more a “mosaic” approach than a traditional one on a more focused subject).

Pingback: Connecting chapters/chapter introductions | Lif...

I notice that you are speaking in the first person in some of the sentence starters. Thanks for that, Pat.

Like Liked by 1 person

Dear Pat This is to say that I greatly appreciate your posts, so relevant and helpful. There….I’ve found a moment to thank you. I’m sure I speak for a large number of researchers. Best wishes Rev’d Theresa

________________________________

Pingback: Academic writing: some resources | Achilleas Kostoulas

Pingback: connecting chapters/chapter conclusions | patter

Dear Pat. Good pointers and perfect timing for me as I have just started my writing. Thanks

Pingback: chapter flow /using headings to help | patter

Pingback: Writing the Thesis | Thesislink

Pingback: The zombie thesis | The Thesis Whisperer

Pingback: The zombie thesis %%sep%% World leading higher education information and services

Hi Pat, I used this framework yesterday. What a great tool! It was useful in structuring my writing in relation to my question and aims. It also provided me with a structure to work from. Thank you.

Reblogged this on TouRNet and commented: …good helpful tips to help in the process of writing

Pingback: Thesis writing advice | A Roller In The Ocean

Hi patter, your tips on “Chapter Connection” in this website is so amazing, really useful. I was struggling with connecting the chapters in the book I am writing, then I came across this website, it fitted the missing puzzle I was looking for. Thank you for writing an article like this to help those of us stuck in similar situation . I really appreciate.

Reblogged this on lateneze and commented: Very helpful

Reblogged this on Xaquín S. Pérez-Sindín López .

Pingback: Linking chapters of your thesis – Research Pointers

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Search for:

Follow Blog via Email

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

patter on facebook

Recent Posts

- a musing on email signatures

- creativity and giving up on knowing it all

- white ants and research education

- Anticipation

- research as creative practice – possibility thinking

- research as – is – creative practice

- On MAL-attribution

- a brief word on academic mobility

- Key word – claim

- key words – contribution

- research key words – significance

- a thesis is not just a display

SEE MY CURATED POSTS ON WAKELET

Top posts & pages.

- a musing on email signatures

- aims and objectives - what's the difference?

- writing a bio-note

- use a structured abstract to help write and revise

- I can't find anything written on my topic... really?

- five ways to structure a literature review

- connecting chapters/chapter conclusions

- headings and subheadings – it helps to be specific

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.com

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Creating an Outline for Your Master’s Thesis

1. introduction.

Your master’s thesis serves to explain the research that you have done during your time as a masters student. For many students, the master’s thesis is the longest document that they’ve ever written, and the length of the document can feel intimidating. The purpose of this CommKit is to cover a key element of writing your thesis: the outline.

2. Criteria for Success

The most important criterion for success is that you’ve shown an outline with your chapter breakdown to your advisor. Your advisor is the one that formally signs off on your thesis as completed, so their feedback is the most important.

Every master’s thesis will have the following elements.

- Introduction – Familiarize the reader with the topic and what gap exists in the field.

- Literature Review – Provide a detailed analysis of similar work in the field and how your work is unique. Master’s thesis literature reviews typically have at least 60 citations throughout the entire document

- Methods – Explain how you produced your results

- Results – Show your results and comment on their significance and implications.

- Conclusion – Summarize the methodology you used to generate results, your key findings, and any future areas of work.

Having an outline for your master’s thesis will help you explain the motivation behind your work, and also connect the different experiments or results that you completed. Furthermore, an outline for your master’s thesis can help break down the larger task of writing the entire thesis into smaller, more manageable chapter-sized subtasks.

4. Analyze Your Audience

The most important audience member for your master’s thesis is your advisor, as they are ultimately the person that signs off on whether or not your thesis is sufficient enough to graduate. The needs of any other audience members are secondary.

Ideally, a good master’s thesis is accessible to people that work in your field. In some cases, master’s theses are passed on to newer students so that that research can continue. In these cases, the thesis is used as a guide to introduce newer students to the research area. If you intend for your thesis to be used as a guide for new students, you may spend more time explaining the state of the field in your introduction and literature review. Additionally, your thesis will be posted publicly on DSpace , MIT’s digital repository for all theses.

5. Best Practices

5.1. identify your claims.

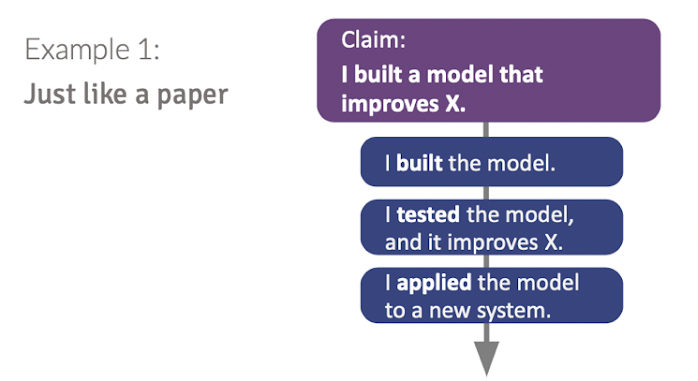

A key element to figuring out the unique structure to your master’s thesis is identifying the claims of your work. A claim is an answer to a research question or gap. Your thesis can have both a higher level claim and also lower level claims that motivate the research projects that you worked on. Identifying your claims will help you spot the key objectives which you want to highlight in the thesis. This will keep your writing on topic.

Some examples are shown below:

Gap/Question : There are no field-portable microplastic sensing technologies to measure their distribution in the environment.

→ Claim : Impedance spectroscopy can be used in a microfluidic device to rapidly distinguish organic matter from polymers.

Gap/Question: How effective are convolutional neural networks for pose estimation during in-space assembly?

→ Claim : Convolutional neural networks can be used to estimate the pose of satellites, but struggle with oversaturated images and images with multiple satellites.

5.2. Support Your Claims

Once you have identified your claim, the next step is to identify evidence that will support it. The structure of your paper will be very dependent on the claim that you make. Figure 1 and 2 demonstrate two different structures to support a claim. In one outline, the claim is best supported by a linear structure that describes the building, testing, and validation of a model. In another outline, the claim is best supported by a trifold structure, where three independent methods are discussed. Depending on the extent of the evidence, you could break this trifold structure into 3 separate chapters, or they could all be discussed in a singular chapter. The value of identifying claims and evidence is that it helps you organize your paper coherently at a high level. The number of chapters that are output as a result of your claim identification is up to you and what you think would be sufficient discussion for a chapter within your thesis.

5.3. Connect the Evidence to Your Claims with Reasoning

One common mistake that students make when writing their thesis is treating each chapter as an isolated piece of writing. While it is helpful to break down the actual task of thesis writing into chapter-size pieces, these chapters should have some connection to one another. For your outline, it is ideal to identify what these connections were. Perhaps what made you start on one project was that you realized the weaknesses in your prior work and you wanted to make improvements. For readers who were not doing the research with you, describing the connections between your work in different chapters can help them understand the motivation and value of why you pursued each component.

5.4. Combine Your Claims, Evidence, and Reasoning to Produce Your Outline

Once you have identified your claims, the evidence you have surrounding each claim, and the reasoning that connects each piece of your work, you can now create your full outline, putting the pieces together like a jigsaw puzzle. An example outline is provided as an annotated example.

There are no requirements for minimum or maximum number of chapters that your master’s thesis can have. Therefore, when translating your outline to a literal chapter breakdown, you should feel free to use as many chapters as needed. If your methods section for a claim is extremely long, it may make more sense to have it be a standalone chapter, as shown in the attached annotated pdf.

6. Additional Resources

Every IAP, the Comm Lab hosts a workshop on how to write your master’s thesis. This workshop provides tips for writing each of these sections, and steps you through the process of creating an outline.

Resources and Annotated Examples

Example 1. structure diagram and table of contents, example 2. table of contents.

- Directories

Chapter writing

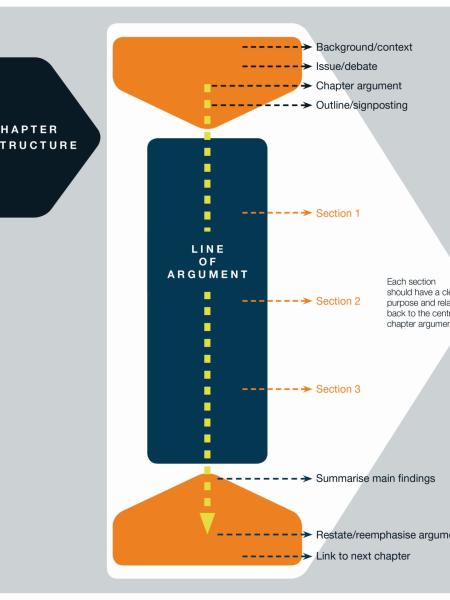

A chapter is a discrete unit of a research report or thesis, and it needs to be able to be read as such.

Your examiners may read your thesis abstract, introduction and conclusion first, but then they may come back weeks later and read a chapter at random, or select one that they are interested in (Mullins & Kiley, 2002). This means that each chapter needs to be easy to read, without the reader having to reread the thesis' introduction to remember what it is about. At the same time, it needs to be clear how the chapter contributes to the development of your overall thesis argument. In the following pages you'll find advice on how to effectively plan and structure your chapters, commuicate and develop your argument with authority, and create clarity and cohesion within your chapters.

Chapter structures

When it comes to structuring a chapter, a chapter should:

- have an introduction that indicates the chapter's argument / key message

- clearly address part of the thesis' overall research question/s or aim/s

- use a structure that persuades the reader of the argument

- have a conclusion that sums up the chapter's contribution to the thesis and shows the link to the next chapter.

To make your chapter easy to read, an introduction, body and conclusion is needed. The introduction should give an overview of how the chapter contributes to your thesis. In a chapter introduction, it works well to explain how the chapter answers or contributes to the overall research question. That way, the reader is reminded of your thesis' purpose and they can understand why this chapter is relevant to it. Before writing, make an outline and show it to a friend or supervisor to test the persuasiveness of the chapter's structure.

The chapter's body should develop the key message logically and persuasively. The sequence of sections and ideas is important to developing a persuasive and clear argument. When outlining your chapter, carefully consider the order in which you will present the information. Ask yourself these questions.

- Would it make your analysis clearer and more convincing to organise your chapter by themes rather than chronologically?

- If you were demonstrating why a particular case study contradicts extant theoretical literature, would it be better to organise the chapter into themes toshow how the case study relates to the literature in respect to each theme, rather than having a dense literature review at the beginning of the chapter?

- Is a brief literature review at the beginning of the chapter necessary and sufficient to establish the key ideas that the chapter's analysis develops?

- What is the best order to convince readers of your overall point?

Our friend the Thesis Whisperer has written about writing discussion chapters and discussion sections within chapters .

If used appropriately, subheadings can also be useful to help your reader to follow your line of argument, distinguish ideas and understand the key idea for each section. Subheadings should not be a substitute for flow or transitional sentences however. In general, substantive discussion should follow a subheading. Use your opening paragraph to a new section to introduce the key ideas that will be developed so that your readers do not get lost or are left wondering how the ideas build on what's already covered. How you connect the different sections of your paper is especially important in a long piece of writing like a chapter.

Paragraphing techniques are essential to develop a persuasive and coherent argument within your chapters. Each paragraph needs to present one main idea. Each paragraph needs to have a topic sentence and supporting evidence, and a final sentence that might summarise that idea, emphasise its significance, draw a conclusion or create a link to the next idea. Using language that shows the connections between ideas can be helpful for developing chapter flow and cohesion .

As suggested in our page on thesis structures , a good way to test out the persuasiveness and logic of your chapter is to talk it over with a friend or colleague. Try to explain the chapter's purpose and argument, and give your key reasons for your argument. Ask them whether it makes sense, or whether there are any ideas that weren't clear. If you find that you express your ideas differently and in a different order to how they're written down, consider whether it would better to revise your argument and adjust the structure to persuasively and more logically make your case in writing.

In sum, when you plan, write and edit your chapter, think about your reader and what they need in order to understand your argument.

- Have you stated your chapter's argument?

- Will a reader be able to identify how it contributes to the whole thesis' research question/s or aim/s?

- Does your chapter flow logically from one idea to the next, and is it convincing?

- Finally, does it have a conclusion that pulls the chapter's key points together and explains its connection to the next chapter?

These elements are central to helpfing your reader follow and be persuaded by your work.

- Mullins, G., & Kiley, M. (2002). 'It's a PhD, not a Nobel Prize': How experienced examiners assess research theses. Studies in Higher Education , 27 (4), 369-386. doi:10.1080/0307507022000011507

Reference documents

- Chapter diagram (PDF, 1.14 MB)

- Chapter template (DOCX, 66.58 KB)

Use contact details to request an alternative file format.

- ANU Library Academic Skills

- +61 2 6125 2972

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write a Thesis Chapter Outline

4-minute read

- 30th April 2023

Are you writing a thesis ? That’s amazing! Give yourself a pat on the back, because reaching that point in your academic career takes a lot of hard work.

When you begin to write, you may feel overwhelmed and unsure of where to start. That’s where outlines come in handy. In this article, we’ll break down an effective outline for a thesis chapter – one that you can follow for each section of your paper.

What Is a Thesis Chapter?

Your thesis will be broken up into several sections . Usually, there’s an introduction, some background information, the methodology, the results and discussion, and a conclusion – or something along those lines.

Your institution will have more specific guidelines on the chapters you need to include and in what order, so make sure you familiarize yourself with those requirements first. To help you organize the content of each chapter, an outline breaks it down into smaller chunks.

The Outline

While the content and length of each chapter will vary, you can follow a similar pattern to organize your information. Each chapter should include:

1. An Introduction

At the start of your chapter, spend some time introducing what you’re about to discuss. This will give readers the chance to quickly get an idea of what you’ll be covering and decide if they want to keep reading.

You could begin with a link to the previous chapter, which will help keep your audience from getting lost if they’re not reading it from start to finish in one sitting. You should then explain the purpose of the chapter and briefly describe how you will achieve it.

Every chapter should have an intro like this, even the introduction ! Of course, the length of this part will vary depending on the length of the chapter itself.

2. The Main Body

After introducing the chapter, you can dive into the meat of it. As with the introduction, the content can be as brief or as lengthy as it needs to be.

While piecing together your outline, jot down which points are most important to include and then decide how much space you can devote to fleshing out each one. Let’s consider what this might look like, depending on the chapter .

If your thesis is broken up into an introduction, a background/literature review section, a methodology chapter, a discussion of the results, and a conclusion, here’s what the main body could include for each:

● Introduction : A brief summary of the problem or topic and its background, the purpose of the thesis, the research questions that will be addressed, the terminology you’ll be using, and any limitations or unique circumstances.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Background/literature review : A more thorough explanation of the problem, relevant studies and literature, and current knowledge and gaps in knowledge.

● Methodology : A detailed explanation of the research design, participants and how they were chosen, and how the data was collected and analyzed.

● Results/discussion : A thorough description of the results of the study and a discussion of what they could mean.

● Conclusion : A summary of everything that’s been covered, an explanation of the answers that were (or weren’t) found to the research questions, and suggestions for future research.

This is a rough plan of what the main body of each chapter might look like. Your thesis will likely have more chapters, and some of these topics may be broken down into multiple paragraphs, but this offers an idea of where to start.

3. A Conclusion

Once you’ve detailed everything the chapter needs to include, you should summarize what’s been covered and tie it all together. Explain what the chapter accomplished, and once again, you can link back to the previous chapter to point out what questions have been answered at this point in the thesis.

If you’re just getting started on writing your thesis, putting together an outline will help you to get your thoughts organized and give you a place to start. Each chapter should have its own introduction, main body, and conclusion.

And once you have your draft written, be sure to send it our way! Our editors will be happy to check it for grammar, punctuation, spelling, references, formatting, and more. Try out our service for free today!

Frequently Asked Questions

How do you outline a thesis chapter.

Each chapter of your thesis should have its own introduction, the main content or body of the chapter, and a conclusion summarizing what was covered and linking it to the rest of the thesis.

How do you write a thesis statement?

A thesis statement should briefly summarize the topic you’re looking into and state your assumption about it.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

9-minute read

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

How To Write The Discussion Chapter

A Simple Explainer With Examples + Free Template

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2021

If you’re reading this, chances are you’ve reached the discussion chapter of your thesis or dissertation and are looking for a bit of guidance. Well, you’ve come to the right place ! In this post, we’ll unpack and demystify the typical discussion chapter in straightforward, easy to understand language, with loads of examples .

Overview: The Discussion Chapter

- What the discussion chapter is

- What to include in your discussion

- How to write up your discussion

- A few tips and tricks to help you along the way

- Free discussion template

What (exactly) is the discussion chapter?

The discussion chapter is where you interpret and explain your results within your thesis or dissertation. This contrasts with the results chapter, where you merely present and describe the analysis findings (whether qualitative or quantitative ). In the discussion chapter, you elaborate on and evaluate your research findings, and discuss the significance and implications of your results .

In this chapter, you’ll situate your research findings in terms of your research questions or hypotheses and tie them back to previous studies and literature (which you would have covered in your literature review chapter). You’ll also have a look at how relevant and/or significant your findings are to your field of research, and you’ll argue for the conclusions that you draw from your analysis. Simply put, the discussion chapter is there for you to interact with and explain your research findings in a thorough and coherent manner.

What should I include in the discussion chapter?

First things first: in some studies, the results and discussion chapter are combined into one chapter . This depends on the type of study you conducted (i.e., the nature of the study and methodology adopted), as well as the standards set by the university. So, check in with your university regarding their norms and expectations before getting started. In this post, we’ll treat the two chapters as separate, as this is most common.

Basically, your discussion chapter should analyse , explore the meaning and identify the importance of the data you presented in your results chapter. In the discussion chapter, you’ll give your results some form of meaning by evaluating and interpreting them. This will help answer your research questions, achieve your research aims and support your overall conclusion (s). Therefore, you discussion chapter should focus on findings that are directly connected to your research aims and questions. Don’t waste precious time and word count on findings that are not central to the purpose of your research project.

As this chapter is a reflection of your results chapter, it’s vital that you don’t report any new findings . In other words, you can’t present claims here if you didn’t present the relevant data in the results chapter first. So, make sure that for every discussion point you raise in this chapter, you’ve covered the respective data analysis in the results chapter. If you haven’t, you’ll need to go back and adjust your results chapter accordingly.

If you’re struggling to get started, try writing down a bullet point list everything you found in your results chapter. From this, you can make a list of everything you need to cover in your discussion chapter. Also, make sure you revisit your research questions or hypotheses and incorporate the relevant discussion to address these. This will also help you to see how you can structure your chapter logically.

Need a helping hand?

How to write the discussion chapter

Now that you’ve got a clear idea of what the discussion chapter is and what it needs to include, let’s look at how you can go about structuring this critically important chapter. Broadly speaking, there are six core components that need to be included, and these can be treated as steps in the chapter writing process.

Step 1: Restate your research problem and research questions

The first step in writing up your discussion chapter is to remind your reader of your research problem , as well as your research aim(s) and research questions . If you have hypotheses, you can also briefly mention these. This “reminder” is very important because, after reading dozens of pages, the reader may have forgotten the original point of your research or been swayed in another direction. It’s also likely that some readers skip straight to your discussion chapter from the introduction chapter , so make sure that your research aims and research questions are clear.

Step 2: Summarise your key findings

Next, you’ll want to summarise your key findings from your results chapter. This may look different for qualitative and quantitative research , where qualitative research may report on themes and relationships, whereas quantitative research may touch on correlations and causal relationships. Regardless of the methodology, in this section you need to highlight the overall key findings in relation to your research questions.

Typically, this section only requires one or two paragraphs , depending on how many research questions you have. Aim to be concise here, as you will unpack these findings in more detail later in the chapter. For now, a few lines that directly address your research questions are all that you need.

Some examples of the kind of language you’d use here include:

- The data suggest that…

- The data support/oppose the theory that…

- The analysis identifies…

These are purely examples. What you present here will be completely dependent on your original research questions, so make sure that you are led by them .

Step 3: Interpret your results

Once you’ve restated your research problem and research question(s) and briefly presented your key findings, you can unpack your findings by interpreting your results. Remember: only include what you reported in your results section – don’t introduce new information.

From a structural perspective, it can be a wise approach to follow a similar structure in this chapter as you did in your results chapter. This would help improve readability and make it easier for your reader to follow your arguments. For example, if you structured you results discussion by qualitative themes, it may make sense to do the same here.

Alternatively, you may structure this chapter by research questions, or based on an overarching theoretical framework that your study revolved around. Every study is different, so you’ll need to assess what structure works best for you.

When interpreting your results, you’ll want to assess how your findings compare to those of the existing research (from your literature review chapter). Even if your findings contrast with the existing research, you need to include these in your discussion. In fact, those contrasts are often the most interesting findings . In this case, you’d want to think about why you didn’t find what you were expecting in your data and what the significance of this contrast is.

Here are a few questions to help guide your discussion:

- How do your results relate with those of previous studies ?

- If you get results that differ from those of previous studies, why may this be the case?

- What do your results contribute to your field of research?

- What other explanations could there be for your findings?

When interpreting your findings, be careful not to draw conclusions that aren’t substantiated . Every claim you make needs to be backed up with evidence or findings from the data (and that data needs to be presented in the previous chapter – results). This can look different for different studies; qualitative data may require quotes as evidence, whereas quantitative data would use statistical methods and tests. Whatever the case, every claim you make needs to be strongly backed up.

Step 4: Acknowledge the limitations of your study

The fourth step in writing up your discussion chapter is to acknowledge the limitations of the study. These limitations can cover any part of your study , from the scope or theoretical basis to the analysis method(s) or sample. For example, you may find that you collected data from a very small sample with unique characteristics, which would mean that you are unable to generalise your results to the broader population.

For some students, discussing the limitations of their work can feel a little bit self-defeating . This is a misconception, as a core indicator of high-quality research is its ability to accurately identify its weaknesses. In other words, accurately stating the limitations of your work is a strength, not a weakness . All that said, be careful not to undermine your own research. Tell the reader what limitations exist and what improvements could be made, but also remind them of the value of your study despite its limitations.

Step 5: Make recommendations for implementation and future research

Now that you’ve unpacked your findings and acknowledge the limitations thereof, the next thing you’ll need to do is reflect on your study in terms of two factors:

- The practical application of your findings

- Suggestions for future research

The first thing to discuss is how your findings can be used in the real world – in other words, what contribution can they make to the field or industry? Where are these contributions applicable, how and why? For example, if your research is on communication in health settings, in what ways can your findings be applied to the context of a hospital or medical clinic? Make sure that you spell this out for your reader in practical terms, but also be realistic and make sure that any applications are feasible.

The next discussion point is the opportunity for future research . In other words, how can other studies build on what you’ve found and also improve the findings by overcoming some of the limitations in your study (which you discussed a little earlier). In doing this, you’ll want to investigate whether your results fit in with findings of previous research, and if not, why this may be the case. For example, are there any factors that you didn’t consider in your study? What future research can be done to remedy this? When you write up your suggestions, make sure that you don’t just say that more research is needed on the topic, also comment on how the research can build on your study.

Step 6: Provide a concluding summary

Finally, you’ve reached your final stretch. In this section, you’ll want to provide a brief recap of the key findings – in other words, the findings that directly address your research questions . Basically, your conclusion should tell the reader what your study has found, and what they need to take away from reading your report.

When writing up your concluding summary, bear in mind that some readers may skip straight to this section from the beginning of the chapter. So, make sure that this section flows well from and has a strong connection to the opening section of the chapter.

Tips and tricks for an A-grade discussion chapter

Now that you know what the discussion chapter is , what to include and exclude , and how to structure it , here are some tips and suggestions to help you craft a quality discussion chapter.

- When you write up your discussion chapter, make sure that you keep it consistent with your introduction chapter , as some readers will skip from the introduction chapter directly to the discussion chapter. Your discussion should use the same tense as your introduction, and it should also make use of the same key terms.

- Don’t make assumptions about your readers. As a writer, you have hands-on experience with the data and so it can be easy to present it in an over-simplified manner. Make sure that you spell out your findings and interpretations for the intelligent layman.

- Have a look at other theses and dissertations from your institution, especially the discussion sections. This will help you to understand the standards and conventions of your university, and you’ll also get a good idea of how others have structured their discussion chapters. You can also check out our chapter template .

- Avoid using absolute terms such as “These results prove that…”, rather make use of terms such as “suggest” or “indicate”, where you could say, “These results suggest that…” or “These results indicate…”. It is highly unlikely that a dissertation or thesis will scientifically prove something (due to a variety of resource constraints), so be humble in your language.

- Use well-structured and consistently formatted headings to ensure that your reader can easily navigate between sections, and so that your chapter flows logically and coherently.

If you have any questions or thoughts regarding this post, feel free to leave a comment below. Also, if you’re looking for one-on-one help with your discussion chapter (or thesis in general), consider booking a free consultation with one of our highly experienced Grad Coaches to discuss how we can help you.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

36 Comments

Thank you this is helpful!

This is very helpful to me… Thanks a lot for sharing this with us 😊

This has been very helpful indeed. Thank you.

This is actually really helpful, I just stumbled upon it. Very happy that I found it, thank you.

Me too! I was kinda lost on how to approach my discussion chapter. How helpful! Thanks a lot!

This is really good and explicit. Thanks

Thank you, this blog has been such a help.

Thank you. This is very helpful.

Dear sir/madame

Thanks a lot for this helpful blog. Really, it supported me in writing my discussion chapter while I was totally unaware about its structure and method of writing.

With regards

Syed Firoz Ahmad PhD, Research Scholar

I agree so much. This blog was god sent. It assisted me so much while I was totally clueless about the context and the know-how. Now I am fully aware of what I am to do and how I am to do it.

Thanks! This is helpful!

thanks alot for this informative website

Dear Sir/Madam,

Truly, your article was much benefited when i structured my discussion chapter.

Thank you very much!!!

This is helpful for me in writing my research discussion component. I have to copy this text on Microsoft word cause of my weakness that I cannot be able to read the text on screen a long time. So many thanks for this articles.

This was helpful

Thanks Jenna, well explained.

Thank you! This is super helpful.

Thanks very much. I have appreciated the six steps on writing the Discussion chapter which are (i) Restating the research problem and questions (ii) Summarising the key findings (iii) Interpreting the results linked to relating to previous results in positive and negative ways; explaining whay different or same and contribution to field of research and expalnation of findings (iv) Acknowledgeing limitations (v) Recommendations for implementation and future resaerch and finally (vi) Providing a conscluding summary

My two questions are: 1. On step 1 and 2 can it be the overall or you restate and sumamrise on each findings based on the reaerch question? 2. On 4 and 5 do you do the acknowlledgement , recommendations on each research finding or overall. This is not clear from your expalanattion.

Please respond.

This post is very useful. I’m wondering whether practical implications must be introduced in the Discussion section or in the Conclusion section?

Sigh, I never knew a 20 min video could have literally save my life like this. I found this at the right time!!!! Everything I need to know in one video thanks a mil ! OMGG and that 6 step!!!!!! was the cherry on top the cake!!!!!!!!!

Thanks alot.., I have gained much

This piece is very helpful on how to go about my discussion section. I can always recommend GradCoach research guides for colleagues.

Many thanks for this resource. It has been very helpful to me. I was finding it hard to even write the first sentence. Much appreciated.

Thanks so much. Very helpful to know what is included in the discussion section

this was a very helpful and useful information

This is very helpful. Very very helpful. Thanks for sharing this online!

it is very helpfull article, and i will recommend it to my fellow students. Thank you.

Superlative! More grease to your elbows.

Powerful, thank you for sharing.

Wow! Just wow! God bless the day I stumbled upon you guys’ YouTube videos! It’s been truly life changing and anxiety about my report that is due in less than a month has subsided significantly!

Simplified explanation. Well done.

The presentation is enlightening. Thank you very much.

Thanks for the support and guidance

This has been a great help to me and thank you do much

I second that “it is highly unlikely that a dissertation or thesis will scientifically prove something”; although, could you enlighten us on that comment and elaborate more please?

Sure, no problem.

Scientific proof is generally considered a very strong assertion that something is definitively and universally true. In most scientific disciplines, especially within the realms of natural and social sciences, absolute proof is very rare. Instead, researchers aim to provide evidence that supports or rejects hypotheses. This evidence increases or decreases the likelihood that a particular theory is correct, but it rarely proves something in the absolute sense.

Dissertations and theses, as substantial as they are, typically focus on exploring a specific question or problem within a larger field of study. They contribute to a broader conversation and body of knowledge. The aim is often to provide detailed insight, extend understanding, and suggest directions for further research rather than to offer definitive proof. These academic works are part of a cumulative process of knowledge building where each piece of research connects with others to gradually enhance our understanding of complex phenomena.

Furthermore, the rigorous nature of scientific inquiry involves continuous testing, validation, and potential refutation of ideas. What might be considered a “proof” at one point can later be challenged by new evidence or alternative interpretations. Therefore, the language of “proof” is cautiously used in academic circles to maintain scientific integrity and humility.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

ORDER YOUR PAPER

15% off today

from a verified trusted writer

Dissertation writing: how to logically connect all chapters

So what chapters generally make up the dissertation, the generic chapters for most dissertations.

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Methodology and or Procedures

- Findings or Results

- Analysis or Interpretation of Data

- Summary and Conclusions

- Discussions and Recommendations

The art of organizing

You can think of your organizational structure as..., examples of organizational patterns.

- chronological

- problem-solution

Staying focused

So how do you ensure that your paper flows smoothly.

- Have a crystal clear research objective and thesis

- Create an outline for your work early on; right after the first stab at research

- Make changes to the outline as you progress in your research

- When drafting constantly refer back to your main thesis and ensure that you are working towards it

- Prioritize information and begin by including the most vital data first

- Avoid temptations to just 'throw in' information because its interesting or sounds good; all details should be relevant to the thesis

- Attempt to cover your topic thoroughly; no holes or gaps; you can't afford to be lazy when it comes to coverage

- Be diligent about consistency throughout your paper!

Logically connecting all chapters

A clear example, *final note*, our top writers.

Master's in Project Management, PMP, Six Sigma

3436 written pages

432 a+ papers

My Master’s degree and comprehensive writing experience allow me to complete any order fast and hit the nail on the head every time.

MBA, PMP, ITIL

5081 written pages

458 a+ papers

I am experienced writer with an MBA, PMP, ITIL, that consistently delivers unique, quality papers. I take pride in my experience and quickness.

MS in Human Resource Management

38849 written pages

3885 orders

3652 a+ papers

I hold a MS degree in Human Resource and my goal is to help students with flawless, unique papers, delivered on time.

RN, MSN, PCN, PHN

19412 written pages

2774 orders

2691 a+ papers

As Registered Nurse (RN, PCN), I can quickly deal with any medical paper. My expertise and writing skills are perfect for this job.

3179 written pages

763 a+ papers

I have MPA, MHA degrees but, most importantly, experience and skills to provide unique, well-written papers on time.

DNP, BA, APN, PMHNP-BC

2197 written pages

290 a+ papers

I can write about multiple areas and countless topics, as I have a DNP and BA degrees. High-quality writing is my second name.

PhD in American History

1707 written pages

559 a+ papers

A PhD in American history comes handy. Unique papers, any topics, swift delivery — helping with academic writing is my passion.

MA, PsyD, LMFT

22503 written pages

2501 orders

2326 a+ papers

Incredibly fast PsyD writer. Efficient paper writing for college. Hundreds of different tasks finished. Satisfaction guaranteed.

MEd, NCC, LPC, LMFT

2397 written pages

552 a+ papers

Top-ranked writer with tons of experience. Ready to take on any task, and make it unique, as well as objectively good. Always ready!

MSW, LICSWA, DSW-C

3607 written pages

831 a+ papers

Experienced Social Work expert focused on good writing, total uniqueness, and customer satisfaction. My goal — to help YOU.

- Stats & Feedback

Have your tasks done by our professionals to get the best possible results.

NO Billing information is kept with us. You pay through secure and verified payment systems.

All papers we provide are of the highest quality with a well-researched material, proper format and citation style.

Our 24/7 Support team is available to assist you at any time. You also can communicate with your writer during the whole process.

You are the single owner of the completed order. We DO NOT resell any papers written by our expert

All orders are done from scratch following your instructions. Also, papers are reviewed for plagiarism and grammar mistakes.

You can check the quality of our work by looking at various paper examples in the Samples section on our website.

Like your services! Your customer support is very nice and attentive. I used several writing companies and I know the difference now. Your attitude to your clients is the best!

My experience with bestcustomwriting.com was good. My essay was completed on time, content was ok and I could submit it without any revision. Will order again in the future.

- High School $11.23 page 14 days

- College $12.64 page 14 days

- Undergraduate $13.2 page 14 days

- Graduate $14.08 page 14 days

- PhD $14.59 page 14 days

Free samples of our work

There are different types of essays: narrative, persuasive, compare\contrast, definition and many many others. They are written using a required citation style, where the most common are APA and MLA. We want to share some of the essays samples written on various topics using different citation styles.

- Essay Writing

- Term Paper Writing

- Research Paper Writing

- Coursework Writing

- Case Study Writing

- Article Writing

- Article Critique

- Annotated Bibliography Writing

- Research Proposal

- Thesis Proposal

- Dissertation Writing

- Admission / Application Essay

- Editing and Proofreading

- Multiple Choice Questions

- Group Project

- Lab Report Help

- Statistics Project Help

- Math Problems Help

- Buy Term Paper

- Term Paper Help

- Case Study Help

- Complete Coursework for Me

- Dissertation Editing Services

- Marketing Paper

- Bestcustomwriting.com Coupons

- Edit My Paper

- Hire Essay Writers

- Buy College Essay

- Custom Essay Writing

- Culture Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- Citation Styles

- Cause and Effect Essay

- 5 Paragraph Essay

- Paper Writing Service

- Help Me Write An Essay

- Write My Paper

- Research Paper Help

- Term Papers for Sale

- Write My Research Paper

- Homework Help

- College Papers For Sale

- Write My Thesis

- Coursework Assistance

- Custom Term Paper Writing

- Buy An Article Critique

- College Essay Help

- Paper Writers Online

- Write My Lab Report

- Mathematics Paper

- Write My Essay

- Do My Homework

- Buy a PowerPoint Presentation

- Buy a Thesis Paper

- Buy an Essay

- Comparison Essay

- Buy Discussion Post

- Buy Assignment

- Deductive Essay

- Exploratory Essay

- Literature Essay

- Narrative Essay

- Opinion Essay

- Take My Online Class

- Reflective Essay

- Response Essay

- Custom Papers

- Dissertation Help

- Buy Research Paper

- Criminal Law And Justice Essay

- Political Science Essay

- Pay for Papers

- College Paper Help

- How to Write a College Essay

- High School Writing

- Personal Statement Help

- Book Report

- Report Writing

- Cheap Coursework Help

- Literary Research Paper

- Essay Assistance

- Academic Writing Services

- Coursework Help

- Thesis Papers for Sale

- Coursework Writing Service UK

I have read and agree to the Terms of Use , Money Back Guarantee , Privacy and Cookie Policy of BestCustomWriting.com

Use your opportunity to get a discount!

To get your special discount, write your email below

Best papers and best prices !

Want to get quality paper done on time cheaper?

5.5 Connecting Thesis and Argument

Amy Guptill

As an instructor, I’ve noted that a number of new (and sometimes not-so-new) students are skilled wordsmiths and generally clear thinkers but are nevertheless stuck in a high-school style of writing. They struggle to let go of certain assumptions about how an academic paper should be. Some students who have mastered that form, and enjoyed a lot of success from doing so, assume that college writing is simply more of the same. The skills that go into a very basic kind of essay—often called the five-paragraph theme —are indispensable. If you’re good at the five-paragraph theme, then you’re good at identifying a clear and consistent thesis, arranging cohesive paragraphs, organizing evidence for key points, and situating an argument within a broader context through the intro and conclusion.

In college you need to build on those essential skills. The five-paragraph theme, as such, is bland and formulaic; it doesn’t compel deep thinking. Your professors are looking for a more ambitious and arguable thesis, a nuanced and compelling argument, and real-life evidence for all key points, all in an organically [1] structured paper.

Figures 3.1 and 3.2 contrast the standard five-paragraph theme and the organic college paper. The five-paragraph theme, outlined in Figure 3.1 is probably what you’re used to: the introductory paragraph starts broad and gradually narrows to a thesis, which readers expect to find at the very end of that paragraph. In this idealized format, the thesis invokes the magic number of three: three reasons why a statement is true. Each of those reasons is explained and justified in the three body paragraphs, and then the final paragraph restates the thesis before gradually getting broader. This format is easy for readers to follow, and it helps writers organize their points and the evidence that goes with them. That’s why you learned this format.

Figure 3.2, in contrast, represents a paper on the same topic that has the more organic form expected in college. The first key difference is the thesis. Rather than simply positing a number of reasons to think that something is true, it puts forward an arguable statement: one with which a reasonable person might disagree. An arguable thesis gives the paper purpose. It surprises readers and draws them in. You hope your reader thinks, “Huh. Why would they come to that conclusion?” and then feels compelled to read on. The body paragraphs, then, build on one another to carry out this ambitious argument. In the classic five-paragraph theme (Figure 3.1) it hardly matters which of the three reasons you explain first or second. In the more organic structure, (Figure 3.2) each paragraph specifically leads to the next.

The last key difference is seen in the conclusion. Because the organic essay is driven by an ambitious, non-obvious argument, the reader comes to the concluding section thinking, “OK, I’m convinced by the argument. What do you, author, make of it? Why does it matter?” The conclusion of an organically structured paper has a real job to do. It doesn’t just reiterate the thesis; it explains why the thesis matters.

The substantial time you spent mastering the five-paragraph form in Figure 3.1 was time well spent; it’s hard to imagine anyone succeeding with the more organic form without the organizational skills and habits of mind inherent in the simpler form. But if you assume that you must adhere rigidly to the simpler form, you’re blunting your intellectual ambition. Your professors will not be impressed by obvious theses, loosely related body paragraphs, and repetitive conclusions. They want you to undertake an ambitious independent analysis, one that will yield a thesis that is somewhat surprising and challenging to explain.

The Three-Story Thesis: From the Ground Up

You have no doubt been drilled on the need for a thesis statement and its proper location at the end of the introduction. And you also know that all of the key points of the paper should clearly support the central driving thesis. Indeed, the whole model of the five-paragraph theme hinges on a clearly stated and consistent thesis. However, some students are surprised—and dismayed—when some of their early college papers are criticized for not having a good thesis. Their professor might even claim that the paper doesn’t have a thesis when, in the author’s view, it clearly does. That’s because the thesis might NOT have the following which illustrates a more organic method of writing:

- A good thesis is non-obvious. High school teachers needed to make sure that you and all your classmates mastered the basic form of the academic essay. Thus, they were mostly concerned that you had a clear and consistent thesis, even if it was something obvious like “sustainability is important.” A thesis statement like that has a wide-enough scope to incorporate several supporting points and concurring evidence, enabling the writer to demonstrate his or her mastery of the five-paragraph form. Good enough! When they can, high school teachers nudge students to develop arguments that are less obvious and more engaging. College instructors, though, fully expect you to produce something more developed.

- A good thesis is arguable. In everyday life, “arguable” is often used as a synonym for “doubtful.” For a thesis, though, “arguable” means that it’s worth arguing and there is a certain level of probability involved: it’s something with which a reasonable person might disagree. This arguability criterion dovetails with the non-obvious one: it shows that the author has deeply explored a problem and arrived at an argument that legitimately needs 3, 5, 10, or 20 pages to explain and justify. In that way, a good thesis sets an ambitious agenda for a paper. A thesis like “sustainability is important” isn’t at all difficult to argue for, and the reader would have little intrinsic motivation to read the rest of the paper. However, an arguable thesis like “sustainability policies will inevitably fail if they do not incorporate social justice” brings up some healthy skepticism. Thus, the arguable thesis makes the reader want to keep reading.

- A good thesis is well specified. Some student writers fear that they’re giving away the game if they specify their thesis up front; they think that a purposefully vague thesis might be more intriguing to the reader. However, consider movie trailers: they always include the most exciting and poignant moments from the film to attract an audience. In academic papers, too, a well-specified thesis indicates that the author has thought rigorously about an issue and done thorough research, which makes the reader want to keep reading. Don’t just say that a particular policy is effective or fair; say what makes it so. If you want to argue that a particular claim is dubious or incomplete, say why in your thesis.

- A good thesis includes implications. Suppose your assignment is to write a paper about some aspect of the history of linen production and trade, a topic that may seem exceedingly arcane. And suppose you have constructed a well-supported and creative argument that linen was so widely traded in the ancient Mediterranean that it actually served as a kind of currency. [2] That’s a strong, insightful, arguable, well-specified thesis. But which of these thesis statements do you find more engaging?

Linen served as a form of currency in the ancient Mediterranean world, connecting rival empires through circuits of trade.

Linen served as a form of currency in the ancient Mediterranean world, connecting rival empires through circuits of trade. The economic role of linen raises important questions about how shifting environmental conditions can influence economic relationships and, by extension, political conflicts.

Putting your claims in their broader context makes them more interesting to your reader and more impressive to your professors who, after all, assign topics that they think have enduring significance. Finding that significance for yourself makes the most of both your paper and your learning.

How do you produce a good, strong thesis? And how do you know when you’ve gotten there? Many instructors and writers find useful a metaphor based on this passage by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.: [3]

There are one-story intellects, two-story intellects, and three-story intellects with skylights. All fact collectors who have no aim beyond their facts are one-story men. Two-story men compare, reason, generalize using the labor of fact collectors as their own. Three-story men idealize, imagine, predict—their best illumination comes from above the skylight.

One-story theses state inarguable facts. Two-story theses bring in an arguable (interpretive or analytical) point. Three-story theses nest that point within its larger, compelling implications. [4]

The biggest benefit of the three-story metaphor is that it describes a process for building a thesis. To build the first story, you first have to get familiar with the complex, relevant facts surrounding the problem or question. You have to be able to describe the situation thoroughly and accurately. Then, with that first story built, you can layer on the second story by formulating the insightful, arguable point that animates the analysis. That’s often the most effortful part: brainstorming, elaborating, and comparing alternative ideas, finalizing your point. With that specified, you can frame up the third story by articulating why the point you make matters beyond its particular topic or case.

For example, imagine you have been assigned a paper about the impact of online learning in higher education. You would first construct an account of the origins and multiple forms of online learning and assess research findings about its use and effectiveness. If you’ve done that well, you’ll probably come up with a well-considered opinion that wouldn’t be obvious to readers who haven’t looked at the issue in depth. Maybe you’ll want to argue that online learning is a threat to the academic community. Or perhaps you’ll want to make the case that online learning opens up pathways to college degrees that traditional campus-based learning does not. In the course of developing your central argumentative point, you’ll come to recognize its larger context; in this example, you may claim that online learning can serve to better integrate higher education with the rest of society, as online learners bring their educational and career experiences together. To outline this example:

- First story: Online learning is becoming more prevalent and takes many different forms.

- Second story: While most observers see it as a transformation of higher education, online learning is better thought of as an extension of higher education in that it reaches learners who aren’t disposed to participate in traditional campus-based education.

- Third story: Online learning appears to be a promising way to better integrate higher education with other institutions in society, as online learners integrate their educational experiences with the other realms of their life, promoting the freer flow of ideas between the academy and the rest of society.

Here’s another example of a three-story thesis: [5]

- First story: Edith Wharton did not consider herself a modernist writer, and she didn’t write like her modernist contemporaries.

- Second story: However, in her work we can see her grappling with both the questions and literary forms that fascinated modernist writers of her era. While not an avowed modernist, she did engage with modernist themes and questions.

- Third story: Thus, it is more revealing to think of modernism as a conversation rather than a category or practice.

Here’s one more example:

- First story: Scientists disagree about the likely impact in the U.S. of the light brown apple moth (LBAM) , an agricultural pest native to Australia.

- Second story: Research findings to date suggest that the decision to spray pheromones over the skies of several southern Californian counties to combat the LBAM was poorly thought out.

- Third story: Together, the scientific ambiguities and the controversial response strengthen the claim that industrial-style approaches to pest management are inherently unsustainable.

A thesis statement that stops at the first story isn’t usually considered a thesis. A two-story thesis is usually considered competent, though some two-story theses are more intriguing and ambitious than others. A thoughtfully crafted and well-informed three-story thesis puts the author on a smooth path toward an excellent paper.

The concept of a three-story thesis framework was the most helpful piece of information I gained from the writing component of our class. The first time I utilized it in a college paper, my professor included “good thesis” and “excellent introduction” in her notes and graded it significantly higher than my previous papers. You can expect similar results if you dig deeper to form three-story theses. More importantly, doing so will make the actual writing of your paper more straightforward as well. Arguing something specific makes the structure of your paper much easier to design.

Peter Farrell

Three-Story Theses and the Organically Structured Argument

The three-story thesis is a beautiful thing. For one, it gives a paper authentic momentum. The first paragraph doesn’t just start with some broad, vague statement; every sentence is crucial for setting up the thesis. The body paragraphs build on one another, moving through each step of the logical chain. Each paragraph leads inevitably to the next, making the transitions from paragraph to paragraph feel wholly natural. The conclusion, instead of being a mirror-image paraphrase of the introduction, builds out the third story by explaining the broader implications of the argument. It offers new insight without departing from the flow of the analysis.

I should note here that a paper with this kind of momentum often reads like it was knocked out in one inspired sitting. But in reality, just like accomplished athletes and artists, masterful writers make the difficult thing look easy. As writer Anne Lamott notes, reading a well-written piece feels like its author sat down and typed it out, “bounding along like huskies across the snow.” However, she continues,

This is just the fantasy of the uninitiated. I know some very great writers, writers you love who write beautifully and have made a great deal of money, and not one of them sits down routinely feeling wildly enthusiastic and confident. Not one of them writes elegant first drafts. All right, one of them does, but we do not like her very much. [6]

Experienced writers don’t figure out what they want to say and then write it. They write in order to figure out what they want to say.

Experienced writers develop theses in dialog with the body of the essay. An initial characterization of the problem leads to a tentative thesis, and then drafting the body of the paper reveals thorny contradictions or critical areas of ambiguity, prompting the writer to revisit or expand the body of evidence and then refine the thesis based on that fresh look. The revised thesis may require that body paragraphs be reordered and reshaped to fit the emerging three-story thesis. Throughout the process, the thesis serves as an anchor point while the author wades through the morass of facts and ideas. The dialogue between thesis and body continues until the author is satisfied or the due date arrives, whatever comes first. It’s an effortful and sometimes tedious process. Novice writers, in contrast, usually oversimplify the writing process. They formulate some first-impression thesis, produce a reasonably organized outline, and then flesh it out with text, never taking the time to reflect or truly revise their work. They assume that revision is a step backward when, in reality, it is a major step forward.

Everyone has a different way that they like to write. For instance, I like to pop my earbuds in, blast dubstep music, and write on a white board. I like using the white board because it is a lot easier to revise and edit while you write. After I finish writing a paragraph that I am completely satisfied with on the white board, I sit in front of it with my laptop and just type it up.

Kaethe Leonard

Another benefit of the three-story thesis framework is that it demystifies what a “strong” argument is in academic culture. In an era of political polarization, many students may think that a strong argument is based on a simple, bold, combative statement that is promoted in the most forceful way possible. “Gun control is a travesty!” “Toni Morrison is the best writer who ever lived!” When students are encouraged to consider contrasting perspectives in their papers, they fear that doing so will make their own thesis seem mushy and weak. However, in academics a “strong” argument is comprehensive and nuanced, not simple and polemical. The purpose of the argument is to explain to readers why the author—through the course of his or her in-depth study—has arrived at a somewhat surprising point. On that basis, it has to consider plausible counter-arguments and contradictory information. Academic argumentation exemplifies the popular adage about all writing: show, don’t tell. In crafting and carrying out the three-story thesis, you are showing your reader the work you have done.

The model of the organically structured paper and the three-story thesis framework explained here is the very foundation of the paper itself and the process that produces it. The subsequent chapters, focusing on sources, paragraphs, and sentence-level wordsmithing, all follow from the notion that you are writing to think and writing to learn as much as you are writing to communicate. Your professors assume that you have the self-motivation and organizational skills to pursue your analysis with both rigor and flexibility; that is, they envision you developing, testing, refining, and sometimes discarding your own ideas based on a clear-eyed and open-minded assessment of the evidence before you.

Additional Resources

- The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill offers an excellent, readable run-down on the five-paragraph theme, why most college writing assignments want you to go beyond it, and those times when the simpler structure is actually a better choice.

- There are many useful websites that describe good thesis statements and provide examples. Those from the writing centers at Hamilton College and Purdue University are especially helpful.

- Find a scholarly article or book that is interesting to you. Focusing on the abstract and introduction, outline the first, second, and third stories of its thesis.

- Television programming includes content that some find objectionable.

- The percent of children and youth who are overweight or obese has risen in recent decades.

- First-year college students must learn how to independently manage their time.

- The things we surround ourselves with symbolize who we are.

- Find an example of a five-paragraph theme (online essay mills, your own high school work), produce an alternative three-story thesis, and outline an organically structured paper to carry that thesis out.

- “Organic” here doesn’t mean “pesticide-free” or containing carbon; it means the paper grows and develops, sort of like a living thing. ↵

- For more, see Fabio Lopez-Lazaro “Linen.” In Encyclopedia of World Trade from Ancient Times to the Present . Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2005. ↵

- Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., The Poet at the Breakfast Table (New York: Houghton & Mifflin, 1892). ↵

- The metaphor is extraordinarily useful even though the passage is annoying. Beyond the sexist language of the time, I don’t appreciate the condescension toward “fact-collectors.” which reflects a general modernist tendency to elevate the abstract and denigrate the concrete. In reality, data-collection is a creative and demanding craft, arguably more important than theorizing. ↵

- Drawn from Jennifer Haytock, Edith Wharton and the Conversations of Literary Modernism (New York: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2008). ↵ ↵

- Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life (New York: Pantheon, 1994), 21. ↵

Rhetoric Matters: A Guide to Success in the First Year Writing Class Copyright © 2022 by Amy Guptill is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How To Write A Discussion Chapter In Your PhD Discussion

If you’re here, you probably got to the part in your thesis or dissertation where you have to work on the discussion chapter. Don’t worry; we’re here to help! In this article, we’ll break down the discussion chapter in simple language and give you lots of examples to make it easier to understand.”

What is the discussion chapter?

The discussion chapter plays a vital role in your thesis or dissertation.

Unlike the results chapter, which presents your analysis findings, whether they are qualitative or quantitative, this chapter is where you really dig into your results.

Here, you’ll interpret and explain your research findings, exploring their significance and implications.

In this section, you’ll connect your research findings with your research questions or hypotheses and link them back to previous studies and literature, as you did in your literature review chapter.

You’ll also assess the relevance and importance of your findings to your field of study and make a persuasive argument for the conclusions you’ve drawn from your analysis.

In essence, the discussion chapter is your opportunity to engage with and elucidate your research findings in a comprehensive and cohesive manner.

What to Incorporate in the Discussion Chapter?

Let’s start with the basics: in certain studies, the results and discussion chapters are merged into a single chapter.

Whether this applies to your work depends on the type of study you conducted, including its nature and chosen methodology, as well as the guidelines set by your university.

In essence, your discussion chapter’s primary purpose is to dissect, delve into the meaning of, and establish the significance of the data you presented in the results chapter. Here, you will infuse your results with significance by critically evaluating and interpreting them.

This process aids in addressing your research questions, achieving your research objectives, and bolstering your overall conclusions. Therefore, your discussion chapter should squarely focus on findings that are directly relevant to your research objectives and questions.

Since this chapter mirrors your results chapter, it’s imperative that you refrain from introducing any new findings.

In simpler terms, you should avoid making claims in this section if you haven’t already presented the pertinent data in the results chapter.

Hence, ensure that each discussion point you raise in this chapter corresponds to the data analysis covered in the results chapter.

Crafting the Discussion Chapter: A Step-by-Step Guide

Now that you’ve grasped the essence of the discussion chapter and its essential elements let’s delve into structuring this pivotal chapter. In a broad sense, you can break down this chapter into six key components, which serve as sequential steps in the chapter-writing journey.

Step 1: Reiterate Your Research Problem and Questions

When you begin writing your discussion chapter, the first thing to do is remind your reader about what your research is all about, like the main problem you’re trying to solve and what questions you’re trying to answer. This reminder is important because, after reading a bunch of stuff, your reader might forget what your research was really about or get distracted by other things.

Step 2: Sum Up The Main Discoveries

Moving ahead, it’s time to sum up the most important thing you found in your results chapter. Now, this might look different if you did qualitative or quantitative research. Qualitative research could be all about themes and connections, while quantitative research might talk about things like correlations and reasons behind everything happening.

Usually, this part doesn’t need to be long, just a paragraph or two, depending on how many research questions you had. Try to keep it short because you’ll go into more detail later on in the chapter.

Here are some examples of what you might say:

The analysed data suggest that…

The data support/oppose the defined theory that…

The detailed analysis identifies…

Remember, these are just examples. What you say here depends on the questions you were trying to answer in your research, so make sure you address them correctly.

Step 3: Interpret your results

Once you’ve started your research problem and questions and given a quick rundown of what you found, it’s time to explain your discoveries by looking at your results more closely.

But remember, only talk about what you already told them in the results part – don’t bring in new information.

From a structure point of view, it might be a good idea to organise this chapter, kind of like how you did the results one. This makes it easier for your reader to follow along and understand your points better.

Here are a few things to think about while you’re explaining your findings:

- How do your results match up with what other studies found?

- If your results are different from other studies, why do you think that happened?

- What do your results add to your field of research?

- Are there any other reasons your findings could be the way they are?

When you’re explaining your findings, make sure not to say anything that doesn’t have proof. Every idea you put out there should have something to back it up, like data or facts (and you already put that in the results chapter).

Step 4: Admit the Flaws in Your Research