Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

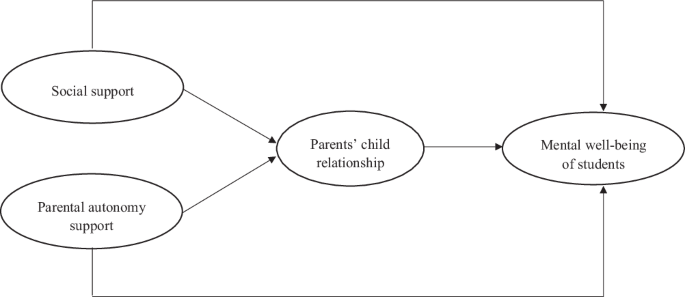

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 26 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

How to Develop a Good Research Hypothesis

The story of a research study begins by asking a question. Researchers all around the globe are asking curious questions and formulating research hypothesis. However, whether the research study provides an effective conclusion depends on how well one develops a good research hypothesis. Research hypothesis examples could help researchers get an idea as to how to write a good research hypothesis.

This blog will help you understand what is a research hypothesis, its characteristics and, how to formulate a research hypothesis

Table of Contents

What is Hypothesis?

Hypothesis is an assumption or an idea proposed for the sake of argument so that it can be tested. It is a precise, testable statement of what the researchers predict will be outcome of the study. Hypothesis usually involves proposing a relationship between two variables: the independent variable (what the researchers change) and the dependent variable (what the research measures).

What is a Research Hypothesis?

Research hypothesis is a statement that introduces a research question and proposes an expected result. It is an integral part of the scientific method that forms the basis of scientific experiments. Therefore, you need to be careful and thorough when building your research hypothesis. A minor flaw in the construction of your hypothesis could have an adverse effect on your experiment. In research, there is a convention that the hypothesis is written in two forms, the null hypothesis, and the alternative hypothesis (called the experimental hypothesis when the method of investigation is an experiment).

Characteristics of a Good Research Hypothesis

As the hypothesis is specific, there is a testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. You may consider drawing hypothesis from previously published research based on the theory.

A good research hypothesis involves more effort than just a guess. In particular, your hypothesis may begin with a question that could be further explored through background research.

To help you formulate a promising research hypothesis, you should ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the language clear and focused?

- What is the relationship between your hypothesis and your research topic?

- Is your hypothesis testable? If yes, then how?

- What are the possible explanations that you might want to explore?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate your variables without hampering the ethical standards?

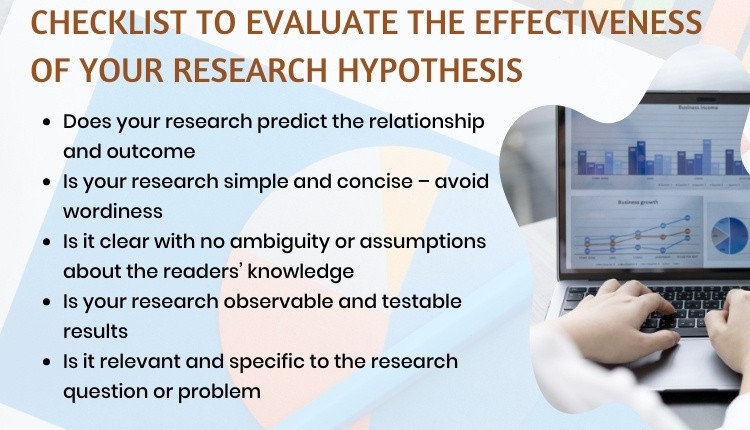

- Does your research predict the relationship and outcome?

- Is your research simple and concise (avoids wordiness)?

- Is it clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Is your research observable and testable results?

- Is it relevant and specific to the research question or problem?

The questions listed above can be used as a checklist to make sure your hypothesis is based on a solid foundation. Furthermore, it can help you identify weaknesses in your hypothesis and revise it if necessary.

Source: Educational Hub

How to formulate a research hypothesis.

A testable hypothesis is not a simple statement. It is rather an intricate statement that needs to offer a clear introduction to a scientific experiment, its intentions, and the possible outcomes. However, there are some important things to consider when building a compelling hypothesis.

1. State the problem that you are trying to solve.

Make sure that the hypothesis clearly defines the topic and the focus of the experiment.

2. Try to write the hypothesis as an if-then statement.

Follow this template: If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.

3. Define the variables

Independent variables are the ones that are manipulated, controlled, or changed. Independent variables are isolated from other factors of the study.

Dependent variables , as the name suggests are dependent on other factors of the study. They are influenced by the change in independent variable.

4. Scrutinize the hypothesis

Evaluate assumptions, predictions, and evidence rigorously to refine your understanding.

Types of Research Hypothesis

The types of research hypothesis are stated below:

1. Simple Hypothesis

It predicts the relationship between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable.

2. Complex Hypothesis

It predicts the relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables.

3. Directional Hypothesis

It specifies the expected direction to be followed to determine the relationship between variables and is derived from theory. Furthermore, it implies the researcher’s intellectual commitment to a particular outcome.

4. Non-directional Hypothesis

It does not predict the exact direction or nature of the relationship between the two variables. The non-directional hypothesis is used when there is no theory involved or when findings contradict previous research.

5. Associative and Causal Hypothesis

The associative hypothesis defines interdependency between variables. A change in one variable results in the change of the other variable. On the other hand, the causal hypothesis proposes an effect on the dependent due to manipulation of the independent variable.

6. Null Hypothesis

Null hypothesis states a negative statement to support the researcher’s findings that there is no relationship between two variables. There will be no changes in the dependent variable due the manipulation of the independent variable. Furthermore, it states results are due to chance and are not significant in terms of supporting the idea being investigated.

7. Alternative Hypothesis

It states that there is a relationship between the two variables of the study and that the results are significant to the research topic. An experimental hypothesis predicts what changes will take place in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated. Also, it states that the results are not due to chance and that they are significant in terms of supporting the theory being investigated.

Research Hypothesis Examples of Independent and Dependent Variables

Research Hypothesis Example 1 The greater number of coal plants in a region (independent variable) increases water pollution (dependent variable). If you change the independent variable (building more coal factories), it will change the dependent variable (amount of water pollution).

Research Hypothesis Example 2 What is the effect of diet or regular soda (independent variable) on blood sugar levels (dependent variable)? If you change the independent variable (the type of soda you consume), it will change the dependent variable (blood sugar levels)

You should not ignore the importance of the above steps. The validity of your experiment and its results rely on a robust testable hypothesis. Developing a strong testable hypothesis has few advantages, it compels us to think intensely and specifically about the outcomes of a study. Consequently, it enables us to understand the implication of the question and the different variables involved in the study. Furthermore, it helps us to make precise predictions based on prior research. Hence, forming a hypothesis would be of great value to the research. Here are some good examples of testable hypotheses.

More importantly, you need to build a robust testable research hypothesis for your scientific experiments. A testable hypothesis is a hypothesis that can be proved or disproved as a result of experimentation.

Importance of a Testable Hypothesis

To devise and perform an experiment using scientific method, you need to make sure that your hypothesis is testable. To be considered testable, some essential criteria must be met:

- There must be a possibility to prove that the hypothesis is true.

- There must be a possibility to prove that the hypothesis is false.

- The results of the hypothesis must be reproducible.

Without these criteria, the hypothesis and the results will be vague. As a result, the experiment will not prove or disprove anything significant.

What are your experiences with building hypotheses for scientific experiments? What challenges did you face? How did you overcome these challenges? Please share your thoughts with us in the comments section.

Frequently Asked Questions

The steps to write a research hypothesis are: 1. Stating the problem: Ensure that the hypothesis defines the research problem 2. Writing a hypothesis as an 'if-then' statement: Include the action and the expected outcome of your study by following a ‘if-then’ structure. 3. Defining the variables: Define the variables as Dependent or Independent based on their dependency to other factors. 4. Scrutinizing the hypothesis: Identify the type of your hypothesis

Hypothesis testing is a statistical tool which is used to make inferences about a population data to draw conclusions for a particular hypothesis.

Hypothesis in statistics is a formal statement about the nature of a population within a structured framework of a statistical model. It is used to test an existing hypothesis by studying a population.

Research hypothesis is a statement that introduces a research question and proposes an expected result. It forms the basis of scientific experiments.

The different types of hypothesis in research are: • Null hypothesis: Null hypothesis is a negative statement to support the researcher’s findings that there is no relationship between two variables. • Alternate hypothesis: Alternate hypothesis predicts the relationship between the two variables of the study. • Directional hypothesis: Directional hypothesis specifies the expected direction to be followed to determine the relationship between variables. • Non-directional hypothesis: Non-directional hypothesis does not predict the exact direction or nature of the relationship between the two variables. • Simple hypothesis: Simple hypothesis predicts the relationship between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable. • Complex hypothesis: Complex hypothesis predicts the relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables. • Associative and casual hypothesis: Associative and casual hypothesis predicts the relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables. • Empirical hypothesis: Empirical hypothesis can be tested via experiments and observation. • Statistical hypothesis: A statistical hypothesis utilizes statistical models to draw conclusions about broader populations.

Wow! You really simplified your explanation that even dummies would find it easy to comprehend. Thank you so much.

Thanks a lot for your valuable guidance.

I enjoy reading the post. Hypotheses are actually an intrinsic part in a study. It bridges the research question and the methodology of the study.

Useful piece!

This is awesome.Wow.

It very interesting to read the topic, can you guide me any specific example of hypothesis process establish throw the Demand and supply of the specific product in market

Nicely explained

It is really a useful for me Kindly give some examples of hypothesis

It was a well explained content ,can you please give me an example with the null and alternative hypothesis illustrated

clear and concise. thanks.

So Good so Amazing

Good to learn

Thanks a lot for explaining to my level of understanding

Explained well and in simple terms. Quick read! Thank you

It awesome. It has really positioned me in my research project

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right approach

The process of choosing the right research design can put ourselves at the crossroads of…

- Industry News

COPE Forum Discussion Highlights Challenges and Urges Clarity in Institutional Authorship Standards

The COPE forum discussion held in December 2023 initiated with a fundamental question — is…

- Career Corner

Unlocking the Power of Networking in Academic Conferences

Embarking on your first academic conference experience? Fear not, we got you covered! Academic conferences…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

How to Design Effective Research Questionnaires for Robust Findings

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

How to Write a Hypothesis: A Step-by-Step Guide

Introduction

An overview of the research hypothesis, different types of hypotheses, variables in a hypothesis, how to formulate an effective research hypothesis, designing a study around your hypothesis.

The scientific method can derive and test predictions as hypotheses. Empirical research can then provide support (or lack thereof) for the hypotheses. Even failure to find support for a hypothesis still represents a valuable contribution to scientific knowledge. Let's look more closely at the idea of the hypothesis and the role it plays in research.

As much as the term exists in everyday language, there is a detailed development that informs the word "hypothesis" when applied to research. A good research hypothesis is informed by prior research and guides research design and data analysis , so it is important to understand how a hypothesis is defined and understood by researchers.

What is the simple definition of a hypothesis?

A hypothesis is a testable prediction about an outcome between two or more variables . It functions as a navigational tool in the research process, directing what you aim to predict and how.

What is the hypothesis for in research?

In research, a hypothesis serves as the cornerstone for your empirical study. It not only lays out what you aim to investigate but also provides a structured approach for your data collection and analysis.

Essentially, it bridges the gap between the theoretical and the empirical, guiding your investigation throughout its course.

What is an example of a hypothesis?

If you are studying the relationship between physical exercise and mental health, a suitable hypothesis could be: "Regular physical exercise leads to improved mental well-being among adults."

This statement constitutes a specific and testable hypothesis that directly relates to the variables you are investigating.

What makes a good hypothesis?

A good hypothesis possesses several key characteristics. Firstly, it must be testable, allowing you to analyze data through empirical means, such as observation or experimentation, to assess if there is significant support for the hypothesis. Secondly, a hypothesis should be specific and unambiguous, giving a clear understanding of the expected relationship between variables. Lastly, it should be grounded in existing research or theoretical frameworks , ensuring its relevance and applicability.

Understanding the types of hypotheses can greatly enhance how you construct and work with hypotheses. While all hypotheses serve the essential function of guiding your study, there are varying purposes among the types of hypotheses. In addition, all hypotheses stand in contrast to the null hypothesis, or the assumption that there is no significant relationship between the variables .

Here, we explore various kinds of hypotheses to provide you with the tools needed to craft effective hypotheses for your specific research needs. Bear in mind that many of these hypothesis types may overlap with one another, and the specific type that is typically used will likely depend on the area of research and methodology you are following.

Null hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that there is no effect or relationship between the variables being studied. In statistical terms, it serves as the default assumption that any observed differences are due to random chance.

For example, if you're studying the effect of a drug on blood pressure, the null hypothesis might state that the drug has no effect.

Alternative hypothesis

Contrary to the null hypothesis, the alternative hypothesis suggests that there is a significant relationship or effect between variables.

Using the drug example, the alternative hypothesis would posit that the drug does indeed affect blood pressure. This is what researchers aim to prove.

Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis makes a prediction about the relationship between two variables, and only two variables.

For example, "Increased study time results in better exam scores." Here, "study time" and "exam scores" are the only variables involved.

Complex hypothesis

A complex hypothesis, as the name suggests, involves more than two variables. For instance, "Increased study time and access to resources result in better exam scores." Here, "study time," "access to resources," and "exam scores" are all variables.

This hypothesis refers to multiple potential mediating variables. Other hypotheses could also include predictions about variables that moderate the relationship between the independent variable and dependent variable .

Directional hypothesis

A directional hypothesis specifies the direction of the expected relationship between variables. For example, "Eating more fruits and vegetables leads to a decrease in heart disease."

Here, the direction of heart disease is explicitly predicted to decrease, due to effects from eating more fruits and vegetables. All hypotheses typically specify the expected direction of the relationship between the independent and dependent variable, such that researchers can test if this prediction holds in their data analysis .

Statistical hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is one that is testable through statistical methods, providing a numerical value that can be analyzed. This is commonly seen in quantitative research .

For example, "There is a statistically significant difference in test scores between students who study for one hour and those who study for two."

Empirical hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is derived from observations and is tested through empirical methods, often through experimentation or survey data . Empirical hypotheses may also be assessed with statistical analyses.

For example, "Regular exercise is correlated with a lower incidence of depression," could be tested through surveys that measure exercise frequency and depression levels.

Causal hypothesis

A causal hypothesis proposes that one variable causes a change in another. This type of hypothesis is often tested through controlled experiments.

For example, "Smoking causes lung cancer," assumes a direct causal relationship.

Associative hypothesis

Unlike causal hypotheses, associative hypotheses suggest a relationship between variables but do not imply causation.

For instance, "People who smoke are more likely to get lung cancer," notes an association but doesn't claim that smoking causes lung cancer directly.

Relational hypothesis

A relational hypothesis explores the relationship between two or more variables but doesn't specify the nature of the relationship.

For example, "There is a relationship between diet and heart health," leaves the nature of the relationship (causal, associative, etc.) open to interpretation.

Logical hypothesis

A logical hypothesis is based on sound reasoning and logical principles. It's often used in theoretical research to explore abstract concepts, rather than being based on empirical data.

For example, "If all men are mortal and Socrates is a man, then Socrates is mortal," employs logical reasoning to make its point.

Let ATLAS.ti take you from research question to key insights

Get started with a free trial and see how ATLAS.ti can make the most of your data.

In any research hypothesis, variables play a critical role. These are the elements or factors that the researcher manipulates, controls, or measures. Understanding variables is essential for crafting a clear, testable hypothesis and for the stages of research that follow, such as data collection and analysis.

In the realm of hypotheses, there are generally two types of variables to consider: independent and dependent. Independent variables are what you, as the researcher, manipulate or change in your study. It's considered the cause in the relationship you're investigating. For instance, in a study examining the impact of sleep duration on academic performance, the independent variable would be the amount of sleep participants get.

Conversely, the dependent variable is the outcome you measure to gauge the effect of your manipulation. It's the effect in the cause-and-effect relationship. The dependent variable thus refers to the main outcome of interest in your study. In the same sleep study example, the academic performance, perhaps measured by exam scores or GPA, would be the dependent variable.

Beyond these two primary types, you might also encounter control variables. These are variables that could potentially influence the outcome and are therefore kept constant to isolate the relationship between the independent and dependent variables . For example, in the sleep and academic performance study, control variables could include age, diet, or even the subject of study.

By clearly identifying and understanding the roles of these variables in your hypothesis, you set the stage for a methodologically sound research project. It helps you develop focused research questions, design appropriate experiments or observations, and carry out meaningful data analysis . It's a step that lays the groundwork for the success of your entire study.

Crafting a strong, testable hypothesis is crucial for the success of any research project. It sets the stage for everything from your study design to data collection and analysis . Below are some key considerations to keep in mind when formulating your hypothesis:

- Be specific : A vague hypothesis can lead to ambiguous results and interpretations . Clearly define your variables and the expected relationship between them.

- Ensure testability : A good hypothesis should be testable through empirical means, whether by observation , experimentation, or other forms of data analysis.

- Ground in literature : Before creating your hypothesis, consult existing research and theories. This not only helps you identify gaps in current knowledge but also gives you valuable context and credibility for crafting your hypothesis.

- Use simple language : While your hypothesis should be conceptually sound, it doesn't have to be complicated. Aim for clarity and simplicity in your wording.

- State direction, if applicable : If your hypothesis involves a directional outcome (e.g., "increase" or "decrease"), make sure to specify this. You also need to think about how you will measure whether or not the outcome moved in the direction you predicted.

- Keep it focused : One of the common pitfalls in hypothesis formulation is trying to answer too many questions at once. Keep your hypothesis focused on a specific issue or relationship.

- Account for control variables : Identify any variables that could potentially impact the outcome and consider how you will control for them in your study.

- Be ethical : Make sure your hypothesis and the methods for testing it comply with ethical standards , particularly if your research involves human or animal subjects.

Designing your study involves multiple key phases that help ensure the rigor and validity of your research. Here we discuss these crucial components in more detail.

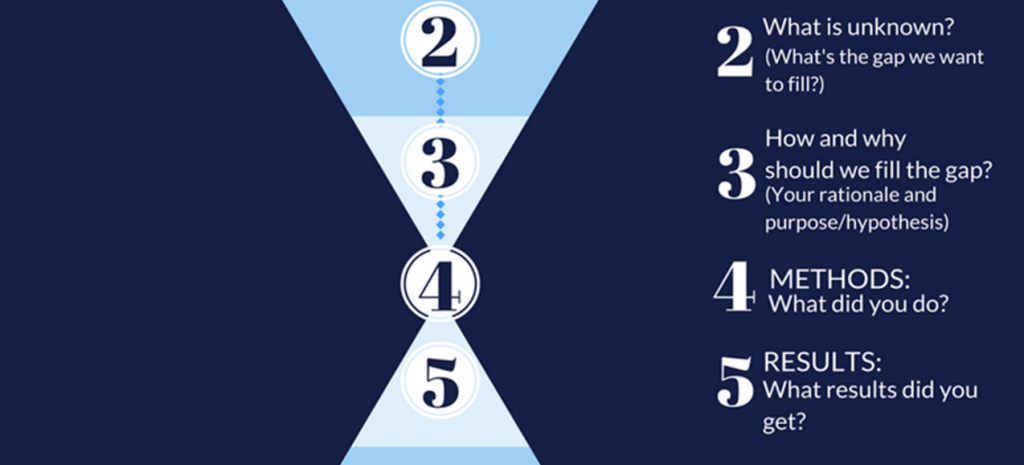

Literature review

Starting with a comprehensive literature review is essential. This step allows you to understand the existing body of knowledge related to your hypothesis and helps you identify gaps that your research could fill. Your research should aim to contribute some novel understanding to existing literature, and your hypotheses can reflect this. A literature review also provides valuable insights into how similar research projects were executed, thereby helping you fine-tune your own approach.

Research methods

Choosing the right research methods is critical. Whether it's a survey, an experiment, or observational study, the methodology should be the most appropriate for testing your hypothesis. Your choice of methods will also depend on whether your research is quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods. Make sure the chosen methods align well with the variables you are studying and the type of data you need.

Preliminary research

Before diving into a full-scale study, it’s often beneficial to conduct preliminary research or a pilot study . This allows you to test your research methods on a smaller scale, refine your tools, and identify any potential issues. For instance, a pilot survey can help you determine if your questions are clear and if the survey effectively captures the data you need. This step can save you both time and resources in the long run.

Data analysis

Finally, planning your data analysis in advance is crucial for a successful study. Decide which statistical or analytical tools are most suited for your data type and research questions . For quantitative research, you might opt for t-tests, ANOVA, or regression analyses. For qualitative research , thematic analysis or grounded theory may be more appropriate. This phase is integral for interpreting your results and drawing meaningful conclusions in relation to your research question.

Turn data into evidence for insights with ATLAS.ti

Powerful analysis for your research paper or presentation is at your fingertips starting with a free trial.

- Manuscript Preparation

What is and How to Write a Good Hypothesis in Research?

- 4 minute read

Table of Contents

One of the most important aspects of conducting research is constructing a strong hypothesis. But what makes a hypothesis in research effective? In this article, we’ll look at the difference between a hypothesis and a research question, as well as the elements of a good hypothesis in research. We’ll also include some examples of effective hypotheses, and what pitfalls to avoid.

What is a Hypothesis in Research?

Simply put, a hypothesis is a research question that also includes the predicted or expected result of the research. Without a hypothesis, there can be no basis for a scientific or research experiment. As such, it is critical that you carefully construct your hypothesis by being deliberate and thorough, even before you set pen to paper. Unless your hypothesis is clearly and carefully constructed, any flaw can have an adverse, and even grave, effect on the quality of your experiment and its subsequent results.

Research Question vs Hypothesis

It’s easy to confuse research questions with hypotheses, and vice versa. While they’re both critical to the Scientific Method, they have very specific differences. Primarily, a research question, just like a hypothesis, is focused and concise. But a hypothesis includes a prediction based on the proposed research, and is designed to forecast the relationship of and between two (or more) variables. Research questions are open-ended, and invite debate and discussion, while hypotheses are closed, e.g. “The relationship between A and B will be C.”

A hypothesis is generally used if your research topic is fairly well established, and you are relatively certain about the relationship between the variables that will be presented in your research. Since a hypothesis is ideally suited for experimental studies, it will, by its very existence, affect the design of your experiment. The research question is typically used for new topics that have not yet been researched extensively. Here, the relationship between different variables is less known. There is no prediction made, but there may be variables explored. The research question can be casual in nature, simply trying to understand if a relationship even exists, descriptive or comparative.

How to Write Hypothesis in Research

Writing an effective hypothesis starts before you even begin to type. Like any task, preparation is key, so you start first by conducting research yourself, and reading all you can about the topic that you plan to research. From there, you’ll gain the knowledge you need to understand where your focus within the topic will lie.

Remember that a hypothesis is a prediction of the relationship that exists between two or more variables. Your job is to write a hypothesis, and design the research, to “prove” whether or not your prediction is correct. A common pitfall is to use judgments that are subjective and inappropriate for the construction of a hypothesis. It’s important to keep the focus and language of your hypothesis objective.

An effective hypothesis in research is clearly and concisely written, and any terms or definitions clarified and defined. Specific language must also be used to avoid any generalities or assumptions.

Use the following points as a checklist to evaluate the effectiveness of your research hypothesis:

- Predicts the relationship and outcome

- Simple and concise – avoid wordiness

- Clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Observable and testable results

- Relevant and specific to the research question or problem

Research Hypothesis Example

Perhaps the best way to evaluate whether or not your hypothesis is effective is to compare it to those of your colleagues in the field. There is no need to reinvent the wheel when it comes to writing a powerful research hypothesis. As you’re reading and preparing your hypothesis, you’ll also read other hypotheses. These can help guide you on what works, and what doesn’t, when it comes to writing a strong research hypothesis.

Here are a few generic examples to get you started.

Eating an apple each day, after the age of 60, will result in a reduction of frequency of physician visits.

Budget airlines are more likely to receive more customer complaints. A budget airline is defined as an airline that offers lower fares and fewer amenities than a traditional full-service airline. (Note that the term “budget airline” is included in the hypothesis.

Workplaces that offer flexible working hours report higher levels of employee job satisfaction than workplaces with fixed hours.

Each of the above examples are specific, observable and measurable, and the statement of prediction can be verified or shown to be false by utilizing standard experimental practices. It should be noted, however, that often your hypothesis will change as your research progresses.

Language Editing Plus

Elsevier’s Language Editing Plus service can help ensure that your research hypothesis is well-designed, and articulates your research and conclusions. Our most comprehensive editing package, you can count on a thorough language review by native-English speakers who are PhDs or PhD candidates. We’ll check for effective logic and flow of your manuscript, as well as document formatting for your chosen journal, reference checks, and much more.

- Research Process

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

What is a Problem Statement? [with examples]

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

How to Write a Research Hypothesis

- Research Process

- Peer Review

Since grade school, we've all been familiar with hypotheses. The hypothesis is an essential step of the scientific method. But what makes an effective research hypothesis, how do you create one, and what types of hypotheses are there? We answer these questions and more.

Updated on April 27, 2022

What is a research hypothesis?

General hypothesis.

Since grade school, we've all been familiar with the term “hypothesis.” A hypothesis is a fact-based guess or prediction that has not been proven. It is an essential step of the scientific method. The hypothesis of a study is a drive for experimentation to either prove the hypothesis or dispute it.

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is more specific than a general hypothesis. It is an educated, expected prediction of the outcome of a study that is testable.

What makes an effective research hypothesis?

A good research hypothesis is a clear statement of the relationship between a dependent variable(s) and independent variable(s) relevant to the study that can be disproven.

Research hypothesis checklist

Once you've written a possible hypothesis, make sure it checks the following boxes:

- It must be testable: You need a means to prove your hypothesis. If you can't test it, it's not a hypothesis.

- It must include a dependent and independent variable: At least one independent variable ( cause ) and one dependent variable ( effect ) must be included.

- The language must be easy to understand: Be as clear and concise as possible. Nothing should be left to interpretation.

- It must be relevant to your research topic: You probably shouldn't be talking about cats and dogs if your research topic is outer space. Stay relevant to your topic.

How to create an effective research hypothesis

Pose it as a question first.

Start your research hypothesis from a journalistic approach. Ask one of the five W's: Who, what, when, where, or why.

A possible initial question could be: Why is the sky blue?

Do the preliminary research

Once you have a question in mind, read research around your topic. Collect research from academic journals.

If you're looking for information about the sky and why it is blue, research information about the atmosphere, weather, space, the sun, etc.

Write a draft hypothesis

Once you're comfortable with your subject and have preliminary knowledge, create a working hypothesis. Don't stress much over this. Your first hypothesis is not permanent. Look at it as a draft.

Your first draft of a hypothesis could be: Certain molecules in the Earth's atmosphere are responsive to the sky being the color blue.

Make your working draft perfect

Take your working hypothesis and make it perfect. Narrow it down to include only the information listed in the “Research hypothesis checklist” above.

Now that you've written your working hypothesis, narrow it down. Your new hypothesis could be: Light from the sun hitting oxygen molecules in the sky makes the color of the sky appear blue.

Write a null hypothesis

Your null hypothesis should be the opposite of your research hypothesis. It should be able to be disproven by your research.

In this example, your null hypothesis would be: Light from the sun hitting oxygen molecules in the sky does not make the color of the sky appear blue.

Why is it important to have a clear, testable hypothesis?

One of the main reasons a manuscript can be rejected from a journal is because of a weak hypothesis. “Poor hypothesis, study design, methodology, and improper use of statistics are other reasons for rejection of a manuscript,” says Dr. Ish Kumar Dhammi and Dr. Rehan-Ul-Haq in Indian Journal of Orthopaedics.

According to Dr. James M. Provenzale in American Journal of Roentgenology , “The clear declaration of a research question (or hypothesis) in the Introduction is critical for reviewers to understand the intent of the research study. It is best to clearly state the study goal in plain language (for example, “We set out to determine whether condition x produces condition y.”) An insufficient problem statement is one of the more common reasons for manuscript rejection.”

Characteristics that make a hypothesis weak include:

- Unclear variables

- Unoriginality

- Too general

- Too specific

A weak hypothesis leads to weak research and methods . The goal of a paper is to prove or disprove a hypothesis - or to prove or disprove a null hypothesis. If the hypothesis is not a dependent variable of what is being studied, the paper's methods should come into question.

A strong hypothesis is essential to the scientific method. A hypothesis states an assumed relationship between at least two variables and the experiment then proves or disproves that relationship with statistical significance. Without a proven and reproducible relationship, the paper feeds into the reproducibility crisis. Learn more about writing for reproducibility .

In a study published in The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India by Dr. Suvarna Satish Khadilkar, she reviewed 400 rejected manuscripts to see why they were rejected. Her studies revealed that poor methodology was a top reason for the submission having a final disposition of rejection.

Aside from publication chances, Dr. Gareth Dyke believes a clear hypothesis helps efficiency.

“Developing a clear and testable hypothesis for your research project means that you will not waste time, energy, and money with your work,” said Dyke. “Refining a hypothesis that is both meaningful, interesting, attainable, and testable is the goal of all effective research.”

Types of research hypotheses

There can be overlap in these types of hypotheses.

Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a hypothesis at its most basic form. It shows the relationship of one independent and one independent variable.

Example: Drinking soda (independent variable) every day leads to obesity (dependent variable).

Complex hypothesis

A complex hypothesis shows the relationship of two or more independent and dependent variables.

Example: Drinking soda (independent variable) every day leads to obesity (dependent variable) and heart disease (dependent variable).

Directional hypothesis

A directional hypothesis guesses which way the results of an experiment will go. It uses words like increase, decrease, higher, lower, positive, negative, more, or less. It is also frequently used in statistics.

Example: Humans exposed to radiation have a higher risk of cancer than humans not exposed to radiation.

Non-directional hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis says there will be an effect on the dependent variable, but it does not say which direction.

Associative hypothesis

An associative hypothesis says that when one variable changes, so does the other variable.

Alternative hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis states that the variables have a relationship.

- The opposite of a null hypothesis

Example: An apple a day keeps the doctor away.

Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis states that there is no relationship between the two variables. It is posed as the opposite of what the alternative hypothesis states.

Researchers use a null hypothesis to work to be able to reject it. A null hypothesis:

- Can never be proven

- Can only be rejected

- Is the opposite of an alternative hypothesis

Example: An apple a day does not keep the doctor away.

Logical hypothesis

A logical hypothesis is a suggested explanation while using limited evidence.

Example: Bats can navigate in the dark better than tigers.

In this hypothesis, the researcher knows that tigers cannot see in the dark, and bats mostly live in darkness.

Empirical hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is also called a “working hypothesis.” It uses the trial and error method and changes around the independent variables.

- An apple a day keeps the doctor away.

- Two apples a day keep the doctor away.

- Three apples a day keep the doctor away.

In this case, the research changes the hypothesis as the researcher learns more about his/her research.

Statistical hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a look of a part of a population or statistical model. This type of hypothesis is especially useful if you are making a statement about a large population. Instead of having to test the entire population of Illinois, you could just use a smaller sample of people who live there.

Example: 70% of people who live in Illinois are iron deficient.

Causal hypothesis

A causal hypothesis states that the independent variable will have an effect on the dependent variable.

Example: Using tobacco products causes cancer.

Final thoughts

Make sure your research is error-free before you send it to your preferred journal . Check our our English Editing services to avoid your chances of desk rejection.

Jonny Rhein, BA

See our "Privacy Policy"

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

What Is A Research (Scientific) Hypothesis? A plain-language explainer + examples

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

If you’re new to the world of research, or it’s your first time writing a dissertation or thesis, you’re probably noticing that the words “research hypothesis” and “scientific hypothesis” are used quite a bit, and you’re wondering what they mean in a research context .

“Hypothesis” is one of those words that people use loosely, thinking they understand what it means. However, it has a very specific meaning within academic research. So, it’s important to understand the exact meaning before you start hypothesizing.

Research Hypothesis 101

- What is a hypothesis ?

- What is a research hypothesis (scientific hypothesis)?

- Requirements for a research hypothesis

- Definition of a research hypothesis

- The null hypothesis

What is a hypothesis?

Let’s start with the general definition of a hypothesis (not a research hypothesis or scientific hypothesis), according to the Cambridge Dictionary:

Hypothesis: an idea or explanation for something that is based on known facts but has not yet been proved.

In other words, it’s a statement that provides an explanation for why or how something works, based on facts (or some reasonable assumptions), but that has not yet been specifically tested . For example, a hypothesis might look something like this:

Hypothesis: sleep impacts academic performance.

This statement predicts that academic performance will be influenced by the amount and/or quality of sleep a student engages in – sounds reasonable, right? It’s based on reasonable assumptions , underpinned by what we currently know about sleep and health (from the existing literature). So, loosely speaking, we could call it a hypothesis, at least by the dictionary definition.

But that’s not good enough…

Unfortunately, that’s not quite sophisticated enough to describe a research hypothesis (also sometimes called a scientific hypothesis), and it wouldn’t be acceptable in a dissertation, thesis or research paper . In the world of academic research, a statement needs a few more criteria to constitute a true research hypothesis .

What is a research hypothesis?

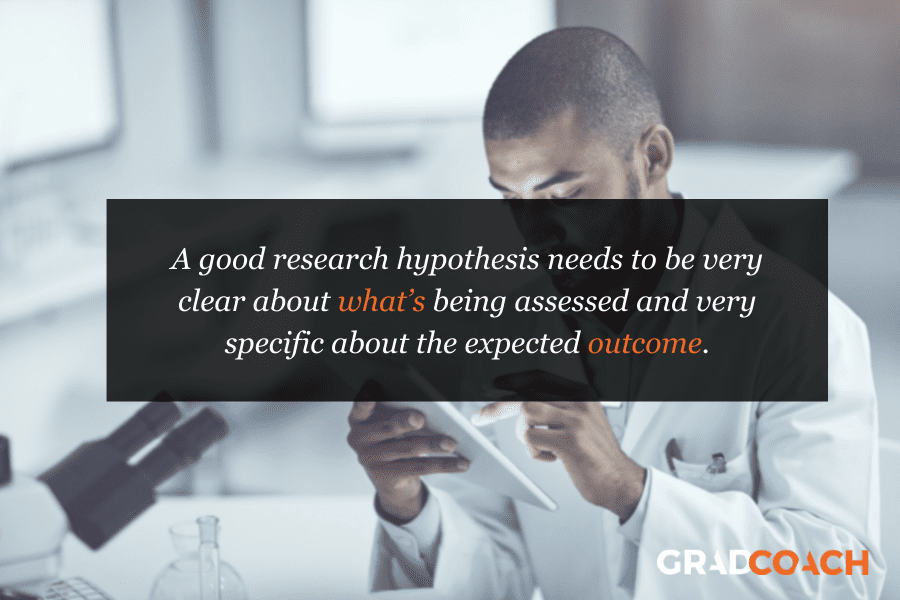

A research hypothesis (also called a scientific hypothesis) is a statement about the expected outcome of a study (for example, a dissertation or thesis). To constitute a quality hypothesis, the statement needs to have three attributes – specificity , clarity and testability .

Let’s take a look at these more closely.

Need a helping hand?

Hypothesis Essential #1: Specificity & Clarity

A good research hypothesis needs to be extremely clear and articulate about both what’ s being assessed (who or what variables are involved ) and the expected outcome (for example, a difference between groups, a relationship between variables, etc.).

Let’s stick with our sleepy students example and look at how this statement could be more specific and clear.

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

As you can see, the statement is very specific as it identifies the variables involved (sleep hours and test grades), the parties involved (two groups of students), as well as the predicted relationship type (a positive relationship). There’s no ambiguity or uncertainty about who or what is involved in the statement, and the expected outcome is clear.

Contrast that to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – and you can see the difference. “Sleep” and “academic performance” are both comparatively vague , and there’s no indication of what the expected relationship direction is (more sleep or less sleep). As you can see, specificity and clarity are key.

Hypothesis Essential #2: Testability (Provability)

A statement must be testable to qualify as a research hypothesis. In other words, there needs to be a way to prove (or disprove) the statement. If it’s not testable, it’s not a hypothesis – simple as that.

For example, consider the hypothesis we mentioned earlier:

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

We could test this statement by undertaking a quantitative study involving two groups of students, one that gets 8 or more hours of sleep per night for a fixed period, and one that gets less. We could then compare the standardised test results for both groups to see if there’s a statistically significant difference.

Again, if you compare this to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – you can see that it would be quite difficult to test that statement, primarily because it isn’t specific enough. How much sleep? By who? What type of academic performance?

So, remember the mantra – if you can’t test it, it’s not a hypothesis 🙂

Defining A Research Hypothesis

You’re still with us? Great! Let’s recap and pin down a clear definition of a hypothesis.

A research hypothesis (or scientific hypothesis) is a statement about an expected relationship between variables, or explanation of an occurrence, that is clear, specific and testable.

So, when you write up hypotheses for your dissertation or thesis, make sure that they meet all these criteria. If you do, you’ll not only have rock-solid hypotheses but you’ll also ensure a clear focus for your entire research project.

What about the null hypothesis?

You may have also heard the terms null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis, or H-zero thrown around. At a simple level, the null hypothesis is the counter-proposal to the original hypothesis.

For example, if the hypothesis predicts that there is a relationship between two variables (for example, sleep and academic performance), the null hypothesis would predict that there is no relationship between those variables.

At a more technical level, the null hypothesis proposes that no statistical significance exists in a set of given observations and that any differences are due to chance alone.

And there you have it – hypotheses in a nutshell.

If you have any questions, be sure to leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help you. If you need hands-on help developing and testing your hypotheses, consider our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

16 Comments

Very useful information. I benefit more from getting more information in this regard.

Very great insight,educative and informative. Please give meet deep critics on many research data of public international Law like human rights, environment, natural resources, law of the sea etc

In a book I read a distinction is made between null, research, and alternative hypothesis. As far as I understand, alternative and research hypotheses are the same. Can you please elaborate? Best Afshin

This is a self explanatory, easy going site. I will recommend this to my friends and colleagues.

Very good definition. How can I cite your definition in my thesis? Thank you. Is nul hypothesis compulsory in a research?

It’s a counter-proposal to be proven as a rejection

Please what is the difference between alternate hypothesis and research hypothesis?

It is a very good explanation. However, it limits hypotheses to statistically tasteable ideas. What about for qualitative researches or other researches that involve quantitative data that don’t need statistical tests?

In qualitative research, one typically uses propositions, not hypotheses.

could you please elaborate it more

I’ve benefited greatly from these notes, thank you.

This is very helpful

well articulated ideas are presented here, thank you for being reliable sources of information

Excellent. Thanks for being clear and sound about the research methodology and hypothesis (quantitative research)

I have only a simple question regarding the null hypothesis. – Is the null hypothesis (Ho) known as the reversible hypothesis of the alternative hypothesis (H1? – How to test it in academic research?

this is very important note help me much more

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is Research Methodology? Simple Definition (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and objectives are confirmatory in nature. For example,…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- How it works

How to Write a Hypothesis – Steps & Tips

Published by Alaxendra Bets at August 14th, 2021 , Revised On October 26, 2023

What is a Research Hypothesis?

You can test a research statement with the help of experimental or theoretical research, known as a hypothesis.

If you want to find out the similarities, differences, and relationships between variables, you must write a testable hypothesis before compiling the data, performing analysis, and generating results to complete.

The data analysis and findings will help you test the hypothesis and see whether it is true or false. Here is all you need to know about how to write a hypothesis for a dissertation .

Research Hypothesis Definition

Not sure what the meaning of the research hypothesis is?

A research hypothesis predicts an answer to the research question based on existing theoretical knowledge or experimental data.

Some studies may have multiple hypothesis statements depending on the research question(s). A research hypothesis must be based on formulas, facts, and theories. It should be testable by data analysis, observations, experiments, or other scientific methodologies that can refute or support the statement.

Variables in Hypothesis

Developing a hypothesis is easy. Most research studies have two or more variables in the hypothesis, particularly studies involving correlational and experimental research. The researcher can control or change the independent variable(s) while measuring and observing the independent variable(s).

“How long a student sleeps affects test scores.”

In the above statement, the dependent variable is the test score, while the independent variable is the length of time spent in sleep. Developing a hypothesis will be easy if you know your research’s dependent and independent variables.

Once you have developed a thesis statement, questions such as how to write a hypothesis for the dissertation and how to test a research hypothesis become pretty straightforward.

Looking for dissertation help?

Researchprospect to the rescue then.

We have expert writers on our team who are skilled at helping students with quantitative dissertations across a variety of STEM disciplines. Guaranteeing 100% satisfaction!

Step-by-Step Guide on How to Write a Hypothesis

Here are the steps involved in how to write a hypothesis for a dissertation.

Step 1: Start with a Research Question

- Begin by asking a specific question about a topic of interest.

- This question should be clear, concise, and researchable.

Example: Does exposure to sunlight affect plant growth?

Step 2: Do Preliminary Research

- Before formulating a hypothesis, conduct background research to understand existing knowledge on the topic.

- Familiarise yourself with prior studies, theories, or observations related to the research question.

Step 3: Define Variables

- Independent Variable (IV): The factor that you change or manipulate in an experiment.

- Dependent Variable (DV): The factor that you measure.

Example: IV: Amount of sunlight exposure (e.g., 2 hours/day, 4 hours/day, 8 hours/day) DV: Plant growth (e.g., height in centimetres)

Step 4: Formulate the Hypothesis

- A hypothesis is a statement that predicts the relationship between variables.

- It is often written as an “if-then” statement.

Example: If plants receive more sunlight, then they will grow taller.

Step 5: Ensure it is Testable

A good hypothesis is empirically testable. This means you should be able to design an experiment or observation to test its validity.

Example: You can set up an experiment where plants are exposed to varying amounts of sunlight and then measure their growth over a period of time.

Step 6: Consider Potential Confounding Variables

- Confounding variables are factors other than the independent variable that might affect the outcome.

- It is important to identify these to ensure that they do not skew your results.

Example: Soil quality, water frequency, or type of plant can all affect growth. Consider keeping these constant in your experiment.

Step 7: Write the Null Hypothesis

- The null hypothesis is a statement that there is no effect or no relationship between the variables.

- It is what you aim to disprove or reject through your research.

Example: There is no difference in plant growth regardless of the amount of sunlight exposure.

Step 8: Test your Hypothesis

Design an experiment or conduct observations to test your hypothesis.

Example: Grow three sets of plants: one set exposed to 2 hours of sunlight daily, another exposed to 4 hours, and a third exposed to 8 hours. Measure and compare their growth after a set period.

Step 9: Analyse the Results

After testing, review your data to determine if it supports your hypothesis.

Step 10: Draw Conclusions

- Based on your findings, determine whether you can accept or reject the hypothesis.

- Remember, even if you reject your hypothesis, it’s a valuable result. It can guide future research and refine questions.

Three Ways to Phrase a Hypothesis

Try to use “if”… and “then”… to identify the variables. The independent variable should be present in the first part of the hypothesis, while the dependent variable will form the second part of the statement. Consider understanding the below research hypothesis example to create a specific, clear, and concise research hypothesis;

If an obese lady starts attending Zomba fitness classes, her health will improve.

In academic research, you can write the predicted variable relationship directly because most research studies correlate terms.

The number of Zomba fitness classes attended by the obese lady has a positive effect on health.

If your research compares two groups, then you can develop a hypothesis statement on their differences.

An obese lady who attended most Zumba fitness classes will have better health than those who attended a few.

How to Write a Null Hypothesis

If a statistical analysis is involved in your research, then you must create a null hypothesis. If you find any relationship between the variables, then the null hypothesis will be the default position that there is no relationship between them. H0 is the symbol for the null hypothesis, while the hypothesis is represented as H1. The null hypothesis will also answer your question, “How to test the research hypothesis in the dissertation.”

H0: The number of Zumba fitness classes attended by the obese lady does not affect her health.

H1: The number of Zumba fitness classes attended by obese lady positively affects health.

Also see: Your Dissertation in Education

Hypothesis Examples

Research Question: Does the amount of sunlight a plant receives affect its growth? Hypothesis: Plants that receive more sunlight will grow taller than plants that receive less sunlight.