- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

October 30, 2023

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

FDA approves mirikizumab, a promising induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis

by The Mount Sinai Hospital

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved mirikizumab, on October 26, 2023, a highly effective new treatment for ulcerative colitis (UC), offering a new option to patients battling this chronic and debilitating inflammatory bowel disease.

This therapy offers a safe and effective treatment option for patients with moderate-to-severely active UC who have yet to achieve rapid and lasting improvements on currently available therapies. Unlike existing treatments for UC, mirikizumab also offers relief from a key symptom—bowel urgency—that greatly impacts patients' quality of life.

Ulcerative colitis affects millions of people worldwide. The induction and maintenance of remission are critical goals in the management of UC. However, existing therapies may not provide sufficient efficacy or patients may have trouble tolerating them.

"Mirikizumab is the first antibody targeting p19/interleukin-23 to be approved for the treatment of ulcerative colitis . Its performance in both induction and maintenance phases of the clinical trials is truly impressive," said Bruce Sands, MD, MS, senior author of the clinical trial study published in the New England Journal of Medicine ( NEJM ). Dr. Sands is Chief, Dr. Henry D. Janowitz Division of Gastroenterology, Mount Sinai Health System, and the Dr. Burrill B. Crohn Professor of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Sands is also a paid consultant for Lilly U.S., LLC.

"The Lucent program was the first clinical trial program that addressed bowel urgency in a meaningful way," said Marla C. Dubinsky, MD, co-author of the NEJM study, Co- director, Susan and Leonard Feinstein Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinical Center, and Professor of Pediatrics, and Medicine, Icahn Mount Sinai. "It is one of the most burdensome patient-reported symptoms, and a drug that achieves bowel urgency remission is an outcome of great importance to our patients with UC."

As published in NEJM , mirikizumab demonstrated exceptional results in both the induction and maintenance arms of the phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in adults with moderately-to-severely active UC.

Induction Phase (LUCENT-1 Trial)

During the induction phase, the LUCENT-1 trial evaluated the efficacy of mirikizumab in inducing clinical remission at week 12 in patients with moderate to severely active UC.

The study enrolled 1,281 patients who were randomized 3:1 to receive intravenous 330mg mirikizumab or placebo every four weeks for 12 weeks. A significantly greater proportion of mirikizumab-treated patients achieved clinical remission at week 12 (mirikizumab: 24.2%; placebo: 13.3%; p<0.001).

Maintenance Phase (LUCENT-2 Trial)

In the maintenance phase, the LUCENT-2 trial assessed the potential of mirikizumab to maintain clinical remission in patients who had achieved a clinical response in the induction phase. This phase enrolled 544 patients who were re-randomized 2:1 to receive mirikizumab 200 mg or placebo subcutaneously every four weeks for 40 weeks (mirikizumab: 49.9%; placebo: 25.1%; p<0.001).

All major secondary endpoints were achieved in both trials, including clinical response, endoscopic remission, and bowel urgency. Bowel urgency, in particular, was tremendously improved in patients who responded to the treatment, an important achievement because relief from this symptom is a major unmet patient need.

Mirikizumab demonstrated a favorable safety profile in both trials, with adverse events consistent with those expected in this patient population. These safety findings further support the potential of mirikizumab as a well-tolerated therapy for long-term use. The data showed not only rapid relief of symptoms but also the potential to maintain remission over the long term.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Study finds jaboticaba peel reduces inflammation and controls blood sugar in people with metabolic syndrome

45 minutes ago

Study reveals how extremely rare immune cells predict how well treatments work for recurrent hives

2 hours ago

Researchers find connection between PFAS exposure in men and the health of their offspring

Researchers develop new tool for better classification of inherited disease-causing variants

Specialized weight navigation program shows higher use of evidence-based treatments, more weight lost than usual care

Exercise bouts could improve efficacy of cancer drug

Drug-like inhibitor shows promise in preventing flu

Scientists discover a novel way of activating muscle cells' natural defenses against cancer using magnetic pulses

3 hours ago

Cancer drug shows powerful anti-tumor activity in animal models of several different tumor types

4 hours ago

Ultra-processed foods increase cardiometabolic risk in children, study finds

Related stories.

New drug application doubles rates of remission in patients with ulcerative colitis

Jun 28, 2023

Two new studies evaluate agents for treating ulcerative colitis

Sep 27, 2019

FDA approves Skyrizi for moderately to severely active Crohn disease

Jun 20, 2022

Ozanimod beats placebo for ulcerative colitis

Sep 30, 2021

FDA approves velsipity for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis in adults

Oct 18, 2023

Upadacitinib superior to placebo in moderate-to-severe Crohn disease

May 31, 2023

Recommended for you

Second Phase 3 clinical trial again shows dupilumab lessens disease in COPD patients with type 2 inflammation

May 20, 2024

Low-dose iron supplementation has no benefit for breastfed infants, shows study

Acetaminophen shows promise in warding off acute respiratory distress syndrome, organ injury in patients with sepsis

May 19, 2024

Better medical record-keeping needed to fight antibiotic overuse, studies suggest

May 18, 2024

Researcher discovers drug that may delay onset of Alzheimer's, Parkinson's disease and treat hydrocephalus

May 17, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Medical Xpress in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Ulcerative colitis articles within Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology

Review Article | 25 April 2024

Pouchitis: pathophysiology and management

Pouchitis is a common condition that can occur after intestinal surgery. In this Review, Shen discusses our current understanding of the multifactorial pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of pouchitis, primarily in patients with underlying ulcerative colitis.

Year in Review | 07 December 2023

Upgrading therapeutic ambitions and treatment outcomes

Important studies published in 2023 outlined new agents and strategies for the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Therapeutic ambitions for the management of inflammatory bowel disease were raised by the success of combinations of biologic agents in ulcerative colitis and early surgical resection in Crohn’s disease.

- Paulo Gustavo Kotze

- & Severine Vermeire

Review Article | 10 November 2023

Deciphering the different phases of preclinical inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease (IMID). Here, the authors review evidence on the preclinical phase of IBD, outlining and describing the proposed at-risk, initiation and expansion phases. Overlap with other IMIDs is discussed alongside the possible future directions for research into preclinical IBD.

- Jonas J. Rudbaek

- , Manasi Agrawal

- & Tine Jess

In Brief | 08 August 2023

Mirikizumab for inducing and maintaining clinical remission in ulcerative colitis

- Jordan Hindson

Perspective | 20 April 2023

The appendix and ulcerative colitis — an unsolved connection

The appendix is thought to have a role in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis but the association remains unclear. In this Perspective, the authors consider the biology of the appendix with respect to its immunological function and the microbiome, and how this relates to its possible involvement in ulcerative colitis.

- Manasi Agrawal

- , Kristine H. Allin

- & Jean-Frederic Colombel

In Brief | 07 March 2023

Two therapeutic antibodies better than one

Clinical Outlook | 27 January 2023

Positioning therapies for the management of inflammatory bowel disease

A careful integration of the effectiveness and safety of the therapies for inflammatory bowel disease, considering patients’ disease risks, treatment complications and preferences, is warranted to inform the positioning of therapies in clinical practice. Precision medicine might help choose the best option for an individual patient.

- Siddharth Singh

Comment | 19 December 2022

Risk minimization of JAK inhibitors in ulcerative colitis following regulatory guidance

The European Medicines Agency safety committee has revisited the label and recommended the use of Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with certain risk factors only if no suitable treatment alternatives are available. Although regulatory decisions are key to place therapeutic options based on safety, broad restrictions might lead to unintended consequences without an individualized benefit–risk evaluation.

- Silvio Danese

- , Virginia Solitano

- & Laurent Peyrin-Biroulet

Clinical Outlook | 16 September 2022

Medical therapy of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease

Antibodies targeting tumour necrosis factor have substantially advanced the treatment of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Understanding pharmacokinetics and therapeutic drug monitoring has led to increased efficacy and durability of response. Primary non-response is more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease, highlighting the need for alternative biologic agents and oral small molecules.

- Luca Scarallo

- & Anne M. Griffiths

Review Article | 07 December 2021

Revisiting fibrosis in inflammatory bowel disease: the gut thickens

Intestinal fibrosis is an important feature of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that remains poorly understood. Here, D’Alessio and Ungaro et al. review the cellular and molecular mechanisms contributing to intestinal fibrosis and discuss future therapeutic strategies for IBD-related fibrosis.

- Silvia D’Alessio

- , Federica Ungaro

- & Silvio Danese

In Brief | 01 October 2021

Ozanimod is efficacious in ulcerative colitis

- Katrina Ray

Journal Club | 20 September 2021

Inflammatory bowel disease and corticosteroids: the first RCT

- Fernando Gomollón

In Brief | 22 June 2021

Filgotinib for ulcerative colitis

Research Highlight | 04 May 2021

Intercrypt goblet cells — the key to colonic mucus barrier function

News & Views | 05 February 2021

IBD risk prediction using multi-ethnic polygenic risk scores

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has emerged as a global disease, yet identifying those at higher risk of developing IBD remains challenging. A new study highlights the use of a multi-ethnic polygenic risk score to determine risk of inflammatory bowel disease in a large primary care population.

- Ashwin N. Ananthakrishnan

Comment | 20 January 2021

SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in IBD: more pros than cons

Data on the efficacy and safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are now available, but evidence for these vaccines in those who are immunocompromised (including patients with inflammatory bowel diseases) are lacking. As vaccination begins, questions on advantages and disadvantages can be partially addressed using the experience from other vaccines or immune-mediated inflammatory disorders.

- Ferdinando D’Amico

- , Christian Rabaud

News & Views | 01 October 2020

Environmental stimuli and gut inflammation via dysbiosis in mouse and man

A new study sheds further light on the interplay between environmental stimuli, the gut microbiota and intestinal inflammation. Identification of modifiable environmental triggers and the mechanisms by which they act has implications for the prevention and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease.

- Charlie W. Lees

Research Highlight | 03 September 2020

Deciphering the role of CD8 + T cells in IBD: from single-cell analysis to biomarkers

Research Highlight | 21 January 2020

Shining a spotlight on somatic mutations in ulcerative colitis

Research Highlight | 15 October 2019

New trials in ulcerative colitis therapies

- Iain Dickson

Comment | 13 September 2019

Evolving therapeutic goals in ulcerative colitis: towards disease clearance

In ulcerative colitis, treating beyond endoscopic healing has shown a reduction of relapse and hospitalization, pushing for histological remission to be embraced in clinical practice and clinical trials. Here, we propose the concept of disease clearance (symptomatic, endoscopic and histological remission) as the ultimate goal in the treatment of ulcerative colitis.

- , Giulia Roda

In Brief | 29 March 2019

Gut mucosal virome altered in ulcerative colitis

News & Views | 08 March 2019

FMT for ulcerative colitis: closer to the turning point

A new study shows that a sustainable faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) treatment protocol, including anaerobic sample preparation, induces remission of active ulcerative colitis. The promising results are another piece in the puzzle, but it is not yet possible to draw conclusions and implement the procedure in clinical practice.

- Giovanni Cammarota

- & Gianluca Ianiro

In Brief | 06 April 2018

Autofluorescence inferior for dysplasia surveillance

In Brief | 02 November 2017

The changing epidemiology of IBD

Review Article | 11 October 2017

Environmental triggers in IBD: a review of progress and evidence

A wide variety of environmental triggers have been associated with IBD pathogenesis, including the gut microbiota, diet, pollution and early-life factors. This Review discusses the latest evidence and progress towards better understanding the environmental factors associated with IBD.

- , Charles N. Bernstein

- & Claudio Fiocchi

Review Article | 19 July 2017

Gut microbiota and IBD: causation or correlation?

Changes in the composition and metabolic function of the gut microbiota have been linked to IBD, but a direct causal association has yet to be established in humans. This Review discusses the evidence supporting dysbiosis in the gut microbiota in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, exploring evidence from animal models and the translation to human disease.

- Josephine Ni

- , Gary D. Wu

- & Vesselin T. Tomov

In Brief | 14 June 2017

Phase II trial success for anti-MADCAM1 antibody

Research Highlight | 17 May 2017

Tofacitinib effective in ulcerative colitis

- Conor A. Bradley

Research Highlight | 01 March 2017

FMT induces clinical remission in ulcerative colitis

- Hugh Thomas

News & Views | 07 December 2016

Mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis: what constitutes remission?

Patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission are increasingly undergoing colonoscopies to determine endoscopic remission. However, the histological evaluation of biopsy samples provides additional criteria to predict which patients are most likely to undergo relapse, so what is the ideal therapeutic end point for patients with ulcerative colitis?

- Robert H. Riddell

Research Highlight | 05 October 2016

A role for GATA3 in ulcerative colitis

Review Article | 01 September 2016

Acute severe ulcerative colitis: from pathophysiology to clinical management

Acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC) is a potentially life-threatening condition that occurs in ∼20% of patients with ulcerative colitis. Here, the authors provide an overview of ASUC from pathophysiology to clinical management (including drug therapy and surgery).

- Pieter Hindryckx

- , Vipul Jairath

- & Geert D'Haens

In Brief | 13 July 2016

Treatment for acute severe ulcerative colitis

- Isobel Leake

News & Views | 05 May 2016

Vitamin D and IBD: moving towards clinical trials

A new study reports that low vitamin D levels are associated with increased morbidity and severity of IBD. A number of issues must now be addressed to enable the optimal design of interventional studies to test whether vitamin D supplementation can improve outcomes in this disease.

- Margherita T. Cantorna

In Brief | 17 February 2016

CT-P13: a safe and effective treatment for IBD

Research Highlight | 24 December 2015

Maintaining the mucosal barrier in intestinal inflammation

In Brief | 18 November 2015

Who benefits the most from etrolizumab in ulcerative colitis?

In Brief | 08 September 2015

Gel-based drug delivery for IBD hits the target

In Brief | 21 April 2015

Faecal transplant from donors no more effective than autologous transplant for treating ulcerative colitis

News & Views | 15 July 2014

Sequential rescue therapy in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis

Treatment of patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis is still a challenge for physicians. A recent study has evaluated the effectiveness and safety of sequential rescue therapies in this subgroup of patients.

- Paolo Gionchetti

- & Fernando Rizzello

Research Highlight | 24 June 2014

T H 9 cells might have a role in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis

In Brief | 17 June 2014

Phase II study reveals potential of etrolizumab as induction therapy for ulcerative colitis

Research Highlight | 22 April 2014

Mouse model reveals how appendicitis protects against ulcerative colitis

- Claire Greenhill

Research Highlight | 18 March 2014

EUS can differentiate Crohn's disease from ulcerative colitis

- Natalie J. Wood

News & Views | 04 March 2014

Which makes patients happier, surgery or anti-TNF therapy?

Quality of life and disability have been compared in patients with ulcerative colitis who were undergoing one of the two current major treatments of choice, proctocolectomy or anti-TNF therapy. The only significant differences between the two groups were increased use of antidiarrhoeal medication and stool frequency in those who underwent surgery.

- Taku Kobayashi

- & Toshifumi Hibi

Review Article | 07 January 2014

Tailoring anti-TNF therapy in IBD: drug levels and disease activity

Despite the proven and often clinically marked efficacy of anti-TNF drugs for IBD, these biologic agents are not immune to treatment failures. Tailoring anti-TNF treatment in IBD mandates considerations of the different clinical scenarios in which therapy failure might occur while bearing in mind an opposite group of patients in whom intensive therapy might be unnecessary.

- Shomron Ben-Horin

- & Yehuda Chowers

In Brief | 17 September 2013

Induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis—vedolizumab more effective than placebo

News & Views | 13 August 2013

Activity of IBD during pregnancy

Women worry that their IBD will flare during pregnancy. A prospective multicentre study from Europe has now demonstrated that although women with Crohn's disease do not have an increased risk of relapse during pregnancy, women with ulcerative colitis are at increased risk of relapse, both during pregnancy and postpartum.

- Sunanda Kane

News & Views | 30 July 2013

Golimumab in ulcerative colitis: a 'ménage à trois' of drugs

Golimumab, a human anti-TNF antibody, is effective in patients with ulcerative colitis, according to new findings from an international phase III double-blind trial. The addition of this drug makes a ménage à trois of available drugs—comprising infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab—for the treatment of ulcerative colitis.

Browse broader subjects

- Inflammatory diseases

- Inflammatory bowel disease

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Switch language:

J&J’s Tremfya meets endpoints in Phase III ulcerative colitis trial

The company’s monoclonal antibody met primary and secondary endpoints as a maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis in a Phase III trial.

- Share on Linkedin

- Share on Facebook

Johnson and Johnson (J&J) has announced positive data from the Phase III QUASAR maintenance trial for Tremfya (guselkumab) as a maintenance therapy in patients with moderate to severe active ulcerative colitis.

Tremfya is an interleukin (IL)-23 and CD64-inhibiting monoclonal antibody. It was first approved as a treatment for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in 2017. Tremfya has since been approved to treat psoriatic arthritis.

Go deeper with GlobalData

LOA and PTSR Model - JNJ-4703 in Ulcerative Colitis

Loa and ptsr model - jnj-4804 in ulcerative colitis, premium insights.

The gold standard of business intelligence.

Find out more

Related Company Profiles

Johnson & johnson.

The therapy achieved the primary and nine major secondary endpoints in the placebo-controlled Phase III QUASAR maintenance study (NCT04033445). The participants in the trial were randomised to receive either placebo or one of the two doses of subcutaneous Tremfya – 200mg every four weeks (q4w) or 100mg every eight weeks (q8w).

The trial met its primary endpoint by inducing remission in 50% and 45.2% of the participants in the q4w and q8w treatment groups respectively at 44 weeks, compared to the placebo. Of the participants who were in clinical remission, 67% and 71% of the participants in the q4w and q8w treatment groups respectively also achieved endoscopic remission at 44 weeks.

Clinical response was seen in 74.7% and 77.7% of the participants in the q4w and q8w treatment groups respectively at 44 weeks, compared to 43.2% of participants in the placebo group. Endoscopic improvement was seen in 51.6% and 49.5% of the participants in the q4w and q8w treatment groups respectively at 44 weeks, compared to 18.9% of participants in the placebo group.

The data from the trial was presented at the Digestive Disease Week 2024 taking place in Washington DC from 19 to 21 May.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

J&J’s Tremfya is expected to be the successor to the company’s IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor Stelara (ustekinumab). Stelara is an approved treatment for severe plaque psoriasis, active psoriatic arthritis, and ulcerative colitis. As per J&J’s annual report, the therapy generated $10.8bn in global sales last year, but its future sales are expected to decline with multiple biosimilars entering the market .

J&J is also evaluating Tremfya as a treatment for Crohn’s disease in a Phase II GALAXI trial (NCT03466411). The therapy maintained efficacy for three years, with 54.1% of the participants demonstrating clinical remission.

Sign up for our daily news round-up!

Give your business an edge with our leading industry insights.

More Relevant

Faron Pharmaceuticals reports positive data from MDS trial

Gsk boasts win for depemokimab in asthma trials, rila therapeutics doses first cohort in phase i ckd treatment trial, gigagen doses first subject in phase i advanced solid tumour trial, sign up to the newsletter: in brief, your corporate email address, i would also like to subscribe to:.

I consent to Verdict Media Limited collecting my details provided via this form in accordance with Privacy Policy

Thank you for subscribing

View all newsletters from across the GlobalData Media network.

- See us on facebook

- See us on twitter

- See us on youtube

- See us on linkedin

- See us on instagram

Stanford scientists link ulcerative colitis to missing gut microbes

Bacteria normally inhabiting healthy people’s intestines — and the anti-inflammatory metabolites these bacteria produce — are depleted in ulcerative colitis patients, a Stanford study shows.

February 25, 2020 - By Bruce Goldman

Aida Habtezion is the senior author of a study that describes how people with ulcerative colitis have insufficient amounts of a metabolite produced by a family of gut-dwelling bacteria. Steve Castillo

About 1 million people in the United States have ulcerative colitis, a serious disease of the colon that has no cure and whose cause is obscure. Now, a study by Stanford University School of Medicine investigators has tied the condition to a missing microbe.

The microbe makes metabolites that help keep the gut healthy.

“This study helps us to better understand the disease,” said Aida Habtezion , MD, associate professor of gastroenterology and hepatology. “We hope it also leads to our being able to treat it with a naturally produced metabolite that’s already present in high amounts in a healthy gut.”

When the researchers compared two groups of patients — one group with ulcerative colitis, the other group with a rare noninflammatory condition — who had undergone an identical corrective surgical procedure, they discovered that a particular family of bacteria was depleted in patients with ulcerative colitis. These patients also were deficient in a set of anti-inflammatory substances that the bacteria make, the scientists report.

A paper describing the research findings was published online Feb. 25 in Cell Host & Microbe . Habtezion is the senior author. Lead authorship is shared by Sidhartha Sinha , MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology and hepatology, and postdoctoral scholar Yeneneh Haileselassie, PhD.

The discoveries raise the prospect that supplementing ulcerative colitis patients with those missing metabolites — or perhaps someday restoring the gut-dwelling bacteria that produce them — could effectively treat intestinal inflammation in these patients and perhaps those with a related condition called Crohn’s disease, Habtezion said.

A clinical trial to determine whether those metabolites, called secondary bile acids, are effective in treating the disease is now underway at Stanford. Sinha is the trial’s principal investigator, and Habtezion is the co-principal investigator.

Surgery often required

Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory condition in which the immune system attacks tissue in the rectum or colon. Patients can suffer from heavy bleeding, diarrhea, weight loss and, if the colon becomes sufficiently perforated, life-threatening sepsis.

There is no known cure. While immunosuppressant drugs can keep ulcerative colitis at bay, they put patients at increased risk for cancer and infection. Moreover, not all patients respond, and even when an immunosuppressant drug works initially, its effectiveness can fade with time. About one in five ulcerative colitis patients progress to the point where they require total colectomy, the surgical removal of the colon and rectum, followed by the repositioning of the lower end of the small intestine to form a J-shaped pouch that serves as a rectum.

These “pouch patients” can lead quite normal lives. However, as many as half will develop pouchitis, a return of the inflammation and symptoms they experienced in their initial condition.

The new study began with a clinical observation. “Patients with a rare genetic condition called familial adenomatous polyposis, or FAP, are at extremely high risk for colon cancer,” Habtezion said. “To prevent this, they undergo the exact same surgical procedure patients with refractory ulcerative colitis do.” Yet FAP pouch patients rarely if ever experience the inflammatory attacks on their remaining lower digestive tract that ulcerative-colitis patients with a pouch do, she said.

The Stanford scientists decided to find out why. Their first clue lay in a large difference in levels of a group of substances called secondary bile acids in the intestines of seven FAP patients compared with 17 patients with ulcerative colitis who had undergone the pouch surgery. The investigators measured these metabolite levels by examining the participants’ stool samples.

Primary bile acids are produced in the liver, stored in the gallbladder and released into the digestive tract to help emulsify fats. The vast majority of secreted primary bile acids are taken up in the intestine, where resident bacteria perform a series of enzymatic operations to convert them to secondary bile acids.

Prior research has suggested, without much elaboration or follow-up, that secondary bile acids are depleted in ulcerative colitis patients and in those with a related condition, Crohn’s disease, in which tissue-destroying inflammation can occur in both the colon and the small intestine.

The researchers confirmed that levels of the two most prominent secondary bile acids, deoxycholic acid and lithocholic acid, were much lower in stool specimens taken from the ulcerative colitis pouch patients than from FAP pouch patients. Clearly, the surgical procedure hadn’t caused the depletion.

Diminished microbial diversity

These findings were mirrored by the scientists’ observation that microbial diversity in the specimens from ulcerative colitis pouch patients was diminished. Moreover, the investigators showed that a single bacterial family — Ruminococcaceae — was markedly underrepresented in ulcerative colitis pouch patients compared with FAP pouch patients. A genomic analysis of all the gut bacteria in the participants showed that the genes for making enzymes that convert primary bile acids to secondary bile acids were underrepresented, too. Ruminococcaceae, but few other gut bacteria, carry those genes.

“All healthy people have Ruminococcaceae in their intestines,” Habtezion said. “But in the UC pouch patients, members of this family were significantly depleted.”

Incubating primary bile acids with stool samples from FAP pouch patients, but not from ulcerative colitis pouch patients, resulted in those substances’ effective conversion to secondary bile acids.

In three different mouse models of colitis, supplementation with lithocholic acid and deoxycholic acid reduced infiltration by inflammatory immune cells and levels of several inflammatory signaling proteins and chemicals in the mice’s intestines, the researchers showed. The supplements also mitigated the classic symptoms of colitis in the mice, such as weight loss or signs of colon pathology.

All three mouse models are considered representative of not just ulcerative colitis but inflammatory bowel disease in general, a category that also includes Crohn’s disease. So the findings may apply to Crohn’s disease patients, as well, Habtezion said.

In an ongoing Phase 2 trial at Stanford, Sinha, Habtezion and their colleagues are investigating the anti-inflammatory effects, in 18- to 70-year-old ulcerative colitis pouch patients, of oral supplementation with ursodeoxycholic acid, a naturally occurring secondary bile acid approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of primary biliary sclerosis and for management of gall stones. Information about the trial, which is still recruiting people, is available at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03724175 .

Habtezion is associate dean for academic affairs in the School of Medicine, a faculty fellow of Stanford ChEM-H and a member of Stanford Bio-X , the Stanford Cancer Institute , the Stanford Pancreas Cancer Research Group and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford .

Other Stanford co-authors of the study are postdoctoral scholars Min Wang, PhD, Estelle Spear, PhD, Gulshan Singh, PhD, and Hong Namkoong, PhD; former research scientist Linh Nguyen, PhD; former postdoctoral scholar Carolina Tropini, PhD; former gastroenterology medical fellow Davis Sim, MD; research assistant Karolin Jarr; Laren Becker , MD, instructor of gastroenterology and hepatology; Michael Fischbach, PhD, associate professor of bioengineering; and Justin Sonnenburg , PhD, associate professor of microbiology and immunology.

Researchers from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia also contributed to the work.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01DK101119, KL2TR001083 and UL1TR001085), the Ann and Bill Swindells Charitable Trust, the Kenneth Rainin Foundation, and Leslie and Douglas Ballinger.

Stanford’s Department of Medicine also supported the work.

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu .

Hope amid crisis

Psychiatry’s new frontiers

A comprehensive review and update on ulcerative colitis

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Science Center El Paso, 2000B Transmountain Road, El Paso, TX 79911, USA; Paul L. Foster School of Medicine (PLFSOM), Texas Tech University Health Science Center El Paso, 5001 El Paso Dr, El Paso, TX 79905, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Internal Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, 4800 Alberta Avenue, El Paso, TX 79905, USA.

- 3 Paul L. Foster School of Medicine (PLFSOM), Texas Tech University Health Science Center El Paso, 5001 El Paso Dr, El Paso, TX 79905, USA.

- 4 Department of Family Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Science Center El Paso, 2000B Transmountain Road, El Paso, TX 79911, USA.

- 5 Department of Surgery, Texas Tech University Health Science Center El Paso, 2000B Transmountain Road, El Paso, TX 79911, USA.

- 6 Department of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, University of California San Francisco (UCSF), Fresno, CA, USA.

- 7 Division of Gastroenterology, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon.

- 8 Division of Gastroenterology, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon; Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, University of Pittsburgh, M2, C Wing, 200 Lothrop Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA.

- PMID: 30837080

- DOI: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2019.02.004

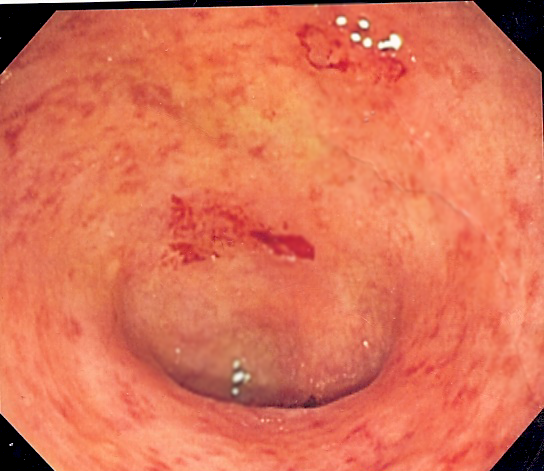

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic idiopathic inflammatory bowel disorder of the colon that causes continuous mucosal inflammation extending from the rectum to the more proximal colon, with variable extents. UC is characterized by a relapsing and remitting course. UC was first described by Samuel Wilks in 1859 and it is more common than Crohn's disease worldwide. The overall incidence and prevalence of UC is reported to be 1.2-20.3 and 7.6-245 cases per 100,000 persons/year respectively. UC has a bimodal age distribution with an incidence peak in the 2nd or 3rd decades and followed by second peak between 50 and 80 years of age. The key risk factors for UC include genetics, environmental factors, autoimmunity and gut microbiota. The classic presentation of UC include bloody diarrhea with or without mucus, rectal urgency, tenesmus, and variable degrees of abdominal pain that is often relieved by defecation. UC is diagnosed based on the combination of clinical presentation, endoscopic findings, histology, and the absence of alternative diagnoses. In addition to confirming the diagnosis of UC, it is also important to define the extent and severity of inflammation, which aids in the selection of appropriate treatment and for predicting the patient's prognosis. Ileocolonoscopy with biopsy is the only way to make a definitive diagnosis of UC. A pathognomonic finding of UC is the presence of continuous colonic inflammation characterized by erythema, loss of normal vascular pattern, granularity, erosions, friability, bleeding, and ulcerations, with distinct demarcation between inflamed and non-inflamed bowel. Histopathology is the definitive tool in diagnosing UC, assessing the disease severity and identifying intraepithelial neoplasia (dysplasia) or cancer. The classical histological changes in UC include decreased crypt density, crypt architectural distortion, irregular mucosal surface and heavy diffuse transmucosal inflammation, in the absence of genuine granulomas. Abdominal computed tomographic (CT) scanning is the preferred initial radiographic imaging study in UC patients with acute abdominal symptoms. The hallmark CT finding of UC is mural thickening with a mean wall thickness of 8 mm, as opposed to a 2-3 mm mean wall thickness of the normal colon. The Mayo scoring system is a commonly used index to assess disease severity and monitor patients during therapy. The goals of treatment in UC are three fold-improve quality of life, achieve steroid free remission and minimize the risk of cancer. The choice of treatment depends on disease extent, severity and the course of the disease. For proctitis, topical 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) drugs are used as the first line agents. UC patients with more extensive or severe disease should be treated with a combination of oral and topical 5-ASA drugs +/- corticosteroids to induce remission. Patients with severe UC need to be hospitalized for treatment. The options in these patients include intravenous steroids and if refractory, calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine, tacrolimus) or tumor necrosis factor-α antibodies (infliximab) are utilized. Once remission is induced, patients are then continued on appropriate medications to maintain remission. Indications for emergency surgery include refractory toxic megacolon, colonic perforation, or severe colorectal bleeding.

Copyright © 2019 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Anti-Inflammatory Agents / therapeutic use

- Colitis, Ulcerative / complications

- Colitis, Ulcerative / diagnosis

- Colitis, Ulcerative / pathology

- Colitis, Ulcerative / therapy*

- Colon / pathology

- Inflammation / diagnosis

- Inflammation / therapy

- Intestinal Mucosa / pathology*

- Quality of Life

- Rectum / pathology

- Severity of Illness Index

- Anti-Inflammatory Agents

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Open Access

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- ECCO Guideline/Consensus Papers

- ECCO Topical Reviews

- ECCO Scientific Workshop Papers

- ECCO Position Statements

- Why Publish with JCC

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Order Offprints

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Advertising

- Reprints and ePrints

- Sponsored Supplements

- Branded Books

- Journals Career Network

- About Journal of Crohn's and Colitis

- About the European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Mri features indicative of permanent colon damage in ulcerative colitis: an exploratory study.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jordi Rimola, Jesús Castro-Poceiro, Víctor Sapena, Marta Aduna, Juan Arevalo, Isabel Vera, Miguel Ángel Pastrana, Marta Gallego, Maria Carme Masamunt, Agnès Fernández-Clotet, Ingrid Ordás, Elena Ricart, Julian Panés, MRI features indicative of permanent colon damage in ulcerative colitis: an exploratory study, Journal of Crohn's and Colitis , 2024;, jjae075, https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjae075

- Permissions Icon Permissions

It is uncertain whether ulcerative colitis leads to accumulated bowel damage on cross sectional image. We aimed to characterize bowel damage in patients with ulcerative colitis using magnetic resonance imaging and determine its relation with duration of disease and the impact on patients’ quality of life.

In this prospective study, subjects with ulcerative colitis in endoscopic remission underwent MRI without bowel cleansing and completed quality-of-life questionnaires. Subjects’ magnetic resonance findings were analyzed considering normal values and thresholds determined in controls with no history of inflammatory bowel disease (n=40) and in patients with Crohn’s disease with no history of colonic involvement (n=12). Subjects with UC were stratified according to disease duration (<7 years vs. 7‒14 years vs. >14 years).

We analyzed 41 subjects with ulcerative colitis [20 women; Mayo endoscopic subscore 0 in 38 (92.7%) and 1 in 3 (7.3%)]. Paired segment-by-segment comparison of magnetic resonance findings in colonic segments documented of being affected by ulcerative colitis versus controls showed subjects with ulcerative colitis had decreased cross-sectional area (p≤0.0034) and perimeter (p≤0.0005), and increased wall thickness (p=0.026) in all segments. Colon damage, defined as wall thickness ≥3 mm, was seen in 22 (53.7%) subjects. Colon damage was not associated with disease duration or quality of life.

Morphologic abnormalities in the colon were highly prevalent in patients with ulcerative colitis in the absence of inflammation. Structural bowel damage was not associated with disease duration or quality of life.

- nuclear magnetic resonance

- magnetic resonance imaging

- ulcerative colitis

- quality of life

- illness length

Supplementary data

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- About Journal of Crohn's and Colitis

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1876-4479

- Print ISSN 1873-9946

- Copyright © 2024 European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) Published by Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Open access

- Published: 14 May 2024

The development of probiotics and prebiotics therapy to ulcerative colitis: a therapy that has gained considerable momentum

- Jing Guo 1 ,

- Liping Li 1 ,

- Yue Cai 2 &

- Yongbo Kang 1

Cell Communication and Signaling volume 22 , Article number: 268 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

344 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is increasingly common, and it is gradually become a kind of global epidemic. UC is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and it is a lifetime recurrent disease. UC as a common disease has become a financial burden for many people and has the potential to develop into cancer if not prevented or treated. There are multiple factors such as genetic factors, host immune system disorders, and environmental factors to cause UC. A growing body of research have suggested that intestinal microbiota as an environmental factor play an important role in the occurrence and development of UC. Meanwhile, evidence to date suggests that manipulating the gut microbiome may represent effective treatment for the prevention or management of UC. In addition, the main clinical drugs to treat UC are amino salicylate and corticosteroid. These clinical drugs always have some side effects and low success rate when treating patients with UC. Therefore, there is an urgent need for safe and efficient methods to treat UC. Based on this, probiotics and prebiotics may be a valuable treatment for UC. In order to promote the wide clinical application of probiotics and prebiotics in the treatment of UC. This review aims to summarize the recent literature as an aid to better understanding how the probiotics and prebiotics contributes to UC while evaluating and prospecting the therapeutic effect of the probiotics and prebiotics in the treatment of UC based on previous publications.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic non-specific intestinal inflammatory disease [ 1 ]. UC becomes an important health problem, because it’s high morbidity. Especially in newly industrialized countries [ 2 ]. Research shows that the incidence of UC is 10 to 20 patients per 100,000 people every year [ 3 ]. UC often presents with recurrent attacks. And the inflammatory of UC will become a factor of colon cancer in the long run [ 4 ]. The pathogenic factors of UC are sophisticated, it is related to intestinal microbiota, immune function of the body (For example, UC is closely related with Th2 cells) [ 5 ], genetic factor and environment factor (e.g. life-style, dietary habits) and so on [ 6 ]. wherein, intestinal microbiota is one of the most important factor that arise UC [ 7 ]. Therefore, we can use probiotics to regulate the intestinal flora in the treatment of UC [ 8 , 9 ]. A growing body of research has shown that probiotics and prebiotics can bring about remission the symptoms of UC improving intestinal mucosal homeostasis, ameliorating the intestinal microbiota environment, regulating the body’s immune function. Therefore, probiotics and prebiotics may be a very safe and efficient treatment for UC. At the same time, it can greatly reduce the financial burden of patients. Furthermore, New techniques have made it possible to attempt systematic studies of probiotics prebiotics, which can provide more specific information about their functions and pathological variations. This review summarizes cutting-edge research on probiotics and prebiotics treatment for UC, existing issues in probiotics treatment and prebiotics therapy, the future of probiotics and prebiotics, and microbial therapeutics.

Pathogenesis of UC

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. It is characterized by a progressive decline in health. UC is marked by inflammation of the mucosal lining, usually confined to the colon and rectum [ 10 ]. The pathogenesis of UC is closely related to a variety of factors, such as genetics and environment [ 11 ]. Statistically, genetics can only explain 7.5% of the variation in disease and has little predictive power for phenotype. Therefore, it has limited clinical application. Examples of loci associated with increased susceptibility to UC including genes associated with barrier function and human leukocyte antigen, such as HNF4A and CDH1 [ 12 , 13 ]. Environment plays an important role in the development of UC. Such as, living condition, hygiene, diet, etc. While UC is mainly due to immune dysfunction and intestinal barrier dysfunction. Colonic epithelial cells (colonocytes), as the first line of defense of the gut immune system, are closely related to the pathogenesis of the UC. Research findings, the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR γ) is reduced in the colonocytes in patients with UC. And the reduced expression of PPAR γ, which is a nuclear receptor that downregulates inflammation, will stimulate an inflammatory cascade responses through a series of immune responses, leading to the production of large quantities of inflammatory factors [ 14 ]. Also, when certain genes in the intestinal epithelium are functionally deficient, it may lead to disruption of the intestinal barrier function [ 10 ]. The deficiency or malfunction of various immune cells and the abnormal expression of cytokines, which play an important signaling function, can also lead to inflammation, which, if prolonged, can lead to the development of UC. The intestinal immune system also involves the intrinsic and adaptive immunity [ 15 ], involving a variety of immune cells and molecules and others. If dendritic cells abundantly express Toll-like receptors (TLR) which can recognize pathogen pattern receptors, this will leads to the activation of several inflammatory signaling pathway, such as NF-κB [ 16 ] and MAPK pathway, triggering an inflammatory response. The production of large amounts of pro-inflammatory factors affects the differentiation of immune cells such as T cell differentiation towards subpopulation. For example, massive activation of Th2 cells leads to high expression of IL-13, which induces apoptosis of epithelial cells and disrupts the integrity of mucosal barrier [ 17 , 18 ]. Other T helper cells also play an important role in UC. And some research suggest that Breg deficiency may also associated with UC [ 19 ]. The damage of the intestinal mucosal barrier is also an important causative factor in UC. Intestinal secretory dysfunction such as decreased secretion of antimicrobial peptides and mucus layer, or structural defects of intestinal barrier including occludin, ZO-1, ZO-2 and so on. It has been found that the disruption of human gut microbiota, the largest collection of microbes within the body [ 20 ], is critical in the progression of UC, but the specific mechanism is not yet clear.

The role of gut microflora in UC

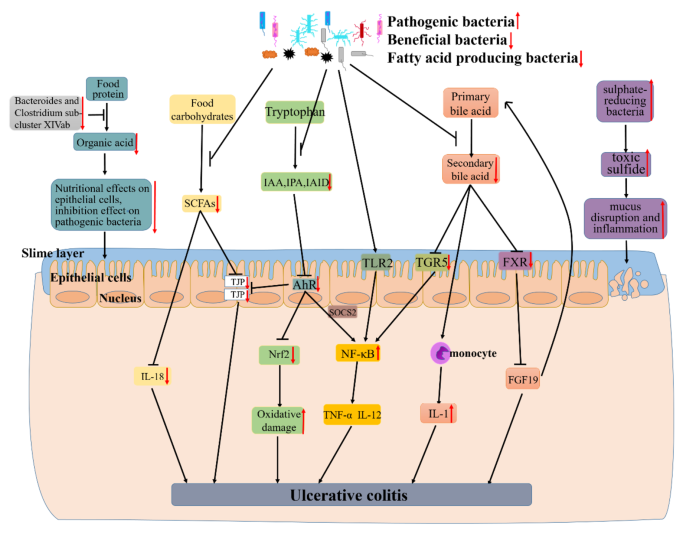

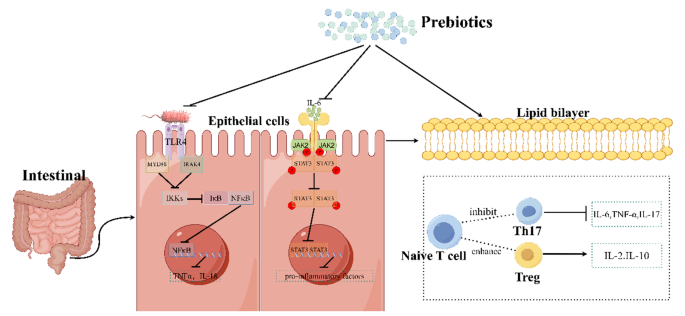

Gut microflora lives on intestinal mucosal and forms bacterial layer. Thus, there is a strong and complex relationship between gut microbiota and gut. Intestinal dysbacteriosis can leads to a decrease in intestinal defense function and immune regulatory function. Furthermore, the decrease of the body immune function and an increase in associated pathogenic factors leading to the intestinal mucosal invasion or exacerbates the gastrointestinal diseases [ 6 ]. Recently, a large number of studies have shown that alterations of intestinal microbiota can play an important role in the occurrence and development of UC. Meanwhile, some studies have shed light on UC subjects exhibiting alterations in the relative abundance of “beneficial” and potentially “harmful” bacteria compared to healthy subjects. The existence of a link between UC and the gut microbiota was indicated based on studies in animals and patients with UC. Changes of gut microbiota together with their-derived products and metabolites account for the important factors to promote UC occurrence. Here, the possible mechanisms of microbiome-gut action in promoting UC occurrence are discussed as well as outlined in Fig. 1 .

The mechanism of UC caused by dysbiosis of gut microbiota. Research findings, the decline of certain beneficial bacteria inhibits the conversion of food protein into organic acid which can nourish epithelial cells and inhibit pathogenic bacteria. Firmicutes as a major producer of butyrate (a kind of SCFAs), its decline leads to lower intestinal SCFAs. Leading the decreased secretion of epithelial repair cytokine interleukin-18, reduced the integrity of epithelial cells, and inhibited goblet cells secrete mucin and modification of tight junctions. And the decline of some gut microbiota also can lead to a decrease of indoles and their derivatives (e.g., IAA, IPA and IAID) which is produced by tryptophan. Thereby reducing the activation of AhR, a member of the activation of PER-ARNT-SIM (PAS) superfamily of transcription factors. The activation of AhR can inhibited the expression of NF-κB in a manner dependent on suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 (SOCS2). And AhR can also maintains the integrity of intestinal barrier activation by increasing the expressions of intestinal tight junction protein (TJPs) or activating the AhR-Nrf2 pathway. All of these effects were reversed due to the decrease of IAA, IPA or IAID. Thus lead to the increase of inflammatory factors (e.g., TNF-α and IL-17) and oxidative damage. Other researchers found that certain pathogenic bacteria such as Bacteroides (B.) fragilis and capsular lipopolysaccharide A can activate NF-κB signaling pathway and promote the secretion of inflammatory factors. The gut microbiota dysbiosis can also lead to the decreased synthesis of secondary bile acid. And secondary acid act as high-affinity ligands for TGR5 and FXR, its decline can promote NF-κB activation to synthesize inflammatory and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines secreted by monocyte and downregulate the expression of FGF19 and promote the synthesis of bile acids thus increasing its toxicity effect on tissues. As an intestinal pathogen, the increase of sulphate-reducing bacteria leads to cell disintegration and inflammatory via toxic sulfide. All of these can lead to the occurrence and development of UC.

A large number of studies have shown that patients with UC have a decrease in the bacterial diversity of gut microbiota [ 21 ]. Animal study results indicate a close association between gut microbiota and UC. Li et al. found that Firmicutes and Proteobacteria increased, whereas Bacteroidetes decreased in UC rats. And Lactobacillus , Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group , Prevotella_9 and Bacteroides were dominant genera in the model group [ 22 ]. Consistent with animal studies, the existence of a link between UC and the gut microbiota was indicated based on studies in patients with UC. Guo et al. also found that the abundance of Bacteroides and Clostridium sub-cluster XIVab as well as the concentration of organic acids significantly decrease by comparing with healthy individuals [ 23 ]. Similarly, Mizoguchi et al. shown that UC patients harbored relatively more abundant Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria and Tenericutes [ 24 ]. A comparison between UC and healthy individuals differed in the composition and diversity of the microbiota, with an upward trend in the Clostridium cluster IX and a decreased Clostridium cluster XIVa in patients with UC [ 25 ]. Consistent with the above results, there is a reduced amounts of bacterial groups from the Clostridium cluster XIVa , and the levels of Bacteroidetes was increased [ 26 ].

In addition, Kotlowski et al. found that the numbers of Escherichia coli were high in the rectal tissue of patients with UC [ 27 ]. By comparing with healthy controls, Xu et al. showed that the inflamed mucosa had more Proteobacteria (e.g. Escherichia–Shigella ) and fewer Firmicutes (e.g., Enterococcus ) [ 28 ]. As demonstrated by Schwiertz et al., Patients with active UC have lower cell counts of Bifidobacterium than healthy controls [ 29 ]. Another study found that the sulfate-reducing bacteria which is the dominant microflora in UC, it may proliferate with the release of toxic sulfide [ 30 ].

Recently, Verma et al. shown that during the active and remission stages of UC cases, the proportions of Bacteroides , Eubacterium , and Lactobacillus spp. are decrease [ 31 ]. Similarly, in another analysis of mucosa-associated flora in UC patients, it was learned that UC patients contained proportionally less Firmicutes , and correspondingly more Bacteroidetes [ 32 ]. Tahara et al. demonstrated that Fusobacterium nucleatum is common which is isolate from human intestinal biopsy from UC, compared to healthy controls [ 33 ].

In keeping with these results, Machiels et al. found that there is a decrease of the Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in patients with UC [ 34 ]. Lepage et al. demonstrated that patients with UC are characterized by more Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria and less bacteria from the Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae families [ 35 ]. Likewise, a significant reduction was found on the UC mucosa compared with the non-IBD controls, that is levels of Clostridium clostridioforme , the Eubacterium rectale group, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii , Bifidobacteria , Lactobacilli , and Clostridium butyricum [ 36 ]. Consistent with the above results of this study, patients with UC in remission compared to that of controls, there is a loss of Bacteroides , Escherichia , Eubacterium , Lactobacillus , and Ruminococcus spp [ 37 ].

Recently, Hu et al. [ 38 ] found that the decreased of the dominant bacteria that digest food carbohydrates to short chain fatty acid (SCFA) lead to the reduce of intestinal barrier integrity (for example, the decrease of TJPs in colon). Guo et al. [ 23 ] also found that SCFAs can affect the secretion of the epithelial repair cytokine interleukin-18. And they found that the decreased of Bacteroides and Clostridium sub-cluster XIVab leading to the decrease of organic acid, which reduces the trophic effect of organic acid to epithelial cells and the inhibitory effect on pathogenic bacteria [ 39 ]. Agus et al. [ 40 ] found that the reduced of certain intestinal flora inhibited the conversion of tryptophan to indole and its derivatives, and AhR as a receptor of indole and its derivatives, its activation will reduced, thereby inhibiting the intestinal TJP and AhR-Nrf2 pathway, leading to the reduced of intestinal barrier integrity and increased oxidative stress [ 41 ]. Rothhammer et al. [ 42 ] demonstrated that the reduce of AhR can promote the activation of NF-κB pathway in a manner dependent on suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 (SOCS2), then increase the expression of a number of inflammatory factors, including TNF-α and IL-12 et al. It is reported that some bacteria regulate the secretion of TNF-α and IL-12 by activating the NF-κB pathway through TLR2 receptor [ 43 ]. Iracheta et al. [ 44 ] found that primary bile acid are converted to secondary bile acid by gut microorganisms after being secreted into gut through a series of reactions, and that a decline of these gut microorganisms leads to a decrease of secondary bile acid. The decrease of secondary bile acid, which act as high-affinity ligands for TGR5 and FXR, leads to a decreased activation of TGF5 and FXR. The inhibitory effect of TGR5 on NF-κB is reduced, thereby promoting the activation of NF-κB. Reduced activation of FXR down-regulates the expression of FGF19, then its inhibitory effect to hepatic bile acid is declined, leading to a further increase of bile acid and exacerbating the development of inflammation [ 45 ]. And the decrease of secondary bile acids promote the secretion of pro-inflammatory factors by monocytes [ 46 ]. Figliuolo et al. [ 47 ] found that the increase of sulphate-reducing bacteria lead to an increase of toxic sulfide, which cause the disruption of gut epithelial cell and increase intestinal inflammatory.

Taken together, these results provide further insights into a role for gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of UC and might potentially serve as guidance for the interventions of UC by manipulating gut microbiota.

Research advances existing challenges IBD treatment

At present, there are many various treatment methods for IBD. Conventional treatment is the use of pharmacotherapy, including aminosalicylates, corticosteroids (CSs), immunomodulators (e.g., thiopurines (TPs), methotrexate (MTX), and calcineurin inhibitors), and biologics (e.g., pro-inflammatory cytokine inhibitors and integrin antagonists). Surgical resection and other methods including apheresis therapy, antibiotics, probiotics and prebiotics can also be used for treatment [ 48 ]. However, the side effects and high reccurence rate of these substances and methods limit there application. For example, research found, although aminosalicylates have been used in the treatment of IBD for the past 80 years, its efficacy remains controversial. And its mild side effects include diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, flatulence and others [ 49 ]. Severe cases can lead to infertility and anemia. CSs inhibits the transcription of certain inflammatory factors [ 50 ] and regulate the expression of certain anti-inflammatory genes [ 51 ] through certain signaling pathways. And it has many side effects, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, venous thromboembolism (VTE), etc [ 52 ].. Some patients may also have dependence on this medication [ 53 ]. TPs inhibits intestinal inflammatory response by regulating T cell proliferation and activation. But TPs can cause side effects such as liver damage [ 54 ] and gastrointestinal intolerance [ 55 ]. MTS excerts its effects also by downregulating inflammatory factors. But it can cause adverse reactions such as fatigue, diarrhea, pneumonia and rash [ 51 ]. Calcineurin inhibitors also supresses inflammatory responses by interfering with signaling pathways. The incidence of side effects of calcineurin inhibitors is high, including renal function damage, hyperkalemia and infectious diseases and so on [ 56 ]. Anti-TNF therapy will inhibit the secretion of pro-inflammatory factor TNF-α. Anti-IL-12/23 therapy works by inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory factor IL-12 and IL-23 by antigen-presenting cells. Anti-integrin therapy inhibits the accumulation of white blood cells in intestinal and alleviates intestinal inflammatory. But these biological agents are expensive and many patients may experience unresponsive and intolerant states. Therefore, it is urgent to study effective and safe methods to treat UC.

In the recent years, regulating gut microbiota has become a hot topic in the treatment of UC. Therefore, as a promising method for treating IBD, probiotics act as live microorganisms have therapeutic effects on IBD which is caused by intestinal ecological disorders and other reasons. The treatment of IBD can be achieved through its antioxidant effects [ 57 ], the regulatory effect on gut microbiota [ 58 ], anti-inflammatory effect [ 59 ], the promotion effect to intestinal barrier integrity [ 60 ] and so on. As an indigestible food ingredient, prebiotics can also be used to treat or alleviate UC by regulating the redox system, immune system, etc. It can also selectively regulate colon microbiota, for example, enhancement of beneficial intestinal bacteria and inhibition of the growth of pathogenic microorganisms. All of these suggests that probiotics and prebiotics have a lot of room to develop as new form of treatment.

Effect and mechanism of probiotics and prebiotics in treating UC

Probiotics are nonpathogenic living microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, have been shown to confer health benefits to the host and regulate intestinal microecological balance. Probiotics are widely used in medical application to prevent or treat many diseases, such as obesity [ 61 ], hepatocellular Carcinoma [ 62 ], autoimmune hepatitis [ 63 ], diabetic retinopathy [ 64 ], and alcoholic liver disease [ 65 ] and so on. The therapeutic effects of probiotics on UC have also been confirmed in animals and humans (Tables 1 and 2 ). Thus, therapeutic interventions with probiotics may offer new treatment for UC. Here, the possible effects and mechanisms of probiotics in the treatment of UC are summarized in Fig. 2 .

The potential mechanism of probiotics in alleviating Ulcerative Colitis (UC). Probiotics that enter the gut can bind with corresponding receptors (e.g. PTK) which are on the intestinal epithelial cells, then inhibit its stimulation to MAPKKK (e.g. TNK1, ASK1, MEKK1, MLK3), further suppress the activation of MAPKK (e.g. MKK3/6, MKK4/7) which are activated by MAPKKK, thereby inhibiting the activation of MAPK (e.g. p38, JNK1,2,3). Blocking the transcription factor transcribe of relevant genes (e.g. Cyclin D1, Raf). Finally, inhibition the inflammatory, apoptosis, and differentiation activated by this pathway. Meanwhile, probiotics protect the intestinal barrier by increasing the levels of tight junction proteins of ZO-1 and Occludin between intestinal epithelial cells, preventing the invasion of pathogenic microorganisms. In addition, probiotics can bind with its receptors (e.g. TLR) on the intestinal epithelial cells, inhibiting the activation of adaptor protein (e.g. RIP1) and suppressing the recruitment of TAB/TAK complex, thereby inhibiting the ubiquitination degradation of IκB by ubiquitinatingNEMO. Prevents the release of NF-κB proteins (RelA/p50) to nucleus. Ultimately inhibits the transcription of proinflammatory factors (e.g. TNF-β) and reduces the promotion effect of TNFα releasing by macrophages to this pathway. Meanwhile, probiotics act on intestinal epithelial cells-associated receptors (e.g. TLR), then phosphorylate AKT, and inhibit the degradation of Nrf2. Nrf2 enters the nucleus and promotes the expression of a range of cytoprotective genes (e.g. SOD, CAT, GSH).

Probiotics therapy

Experimental studies.

Convincing evidence from animal studies indicate that probiotics treatment can relieve UC (Table 1 ). Wu et al. [ 66 ] found that the use of Bifidobacterium longum CCFM1206 to treat Dextran-Sulfate-Sodium (DSS) induced Colitis mice will promotes the conversion of Glucoraphanin (GRP) to sulforaphane (SFN). SFN help to upregulate the Nrf2 signaling pathway and inhibit the NF-κB activity, which can ameliorate DSS-induced colitis. The result also indicated that the intervention of B.longum CCFM1206 could relieve the dysbiosis of intestinal microbiota. That is, promoted the proportion of Alistipes , Bifidobacterium , Blautia and Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group and inhibited the proportion of Acinetobacter , and Lachnospiraceae A2 in the gut. Similar study, Han et al. [ 67 ] demonstrated that Bifidobacterium infantis enhances genetic stability by maintaining the balance of gut flora to increase anaphase-promoting complex subunit 7 (APC7) expression in colonic tissues, changing gut flora such as an increase in B.infantis . Then reducing DSS-induced colonic inflammation. Consistent with the above results, Fu et al. [ 68 ] found that Bacteroides xylanisolvens AY11-1 regulate the intestinal microbiota through the efficient degradation of alginate, improving the dysbiosis of intestinal ecology and promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria, for example, the increase of Blautia spp and Prevotellaceae UCG-001. Then ameliorated the symptoms of DSS-induced UC in mice. Wang et al. [ 69 ] revealed that the administration of probiotic Companilactobacillus crustorum MN047 in DSS-induced UC mice resulted in the expression of tight junctions, and down-regulation of pro-inflammatory and chemokine expression. It was also found that an increase of goblet cells, MUCs, TFF3, and TJs in the probiotic group, which demonstrated that the treat with CCMN could enhance the gut barrier function. And confirmed by fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), the mechanisms of CCMN alleviating UC were partly due to its modulation to gut microbiota. The result showed that an increase in Bacteroidaceae and Burkholderiaceae and a decrease in Akkermansiaceae and Eggerthellaceae . Hu et al. [ 70 ] also found that Selenium-enriched Bifidobacterium longum DD98 administration alleviated the symptoms caused by DSS, inhibited the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, decreased the level of oxidative stress, promoted the expression of tight junction proteins, inhibited the activation of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), and regulated the gut flora. They found that after the treatment of Se-B. longum DD98, the phylum of Bacteroidetes decreased and the phylum of Firmicutes increased. All of the above can be effective attenuated DSS-induced colitis in mice. In another study, the results of Han et al.’s [ 71 ] study of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus Hao9 in DSS-induced UC mice showed that the use of Hao9 attenuated weight loss which is caused by DSS, lowered DAI scores, attenuated colonic damage and inflammatory infiltrates and promoted the growth of Faecalibaculum and Romboutsia in the gut. The researcher attributed the observed effects of Hao9 on UC to its ability to inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced intestinal IκB activation of mice. Consistent with the above results, Huang et al. [ 72 ] also showed that Lactobacillus paracasei R3 supplementation improved the general symptoms of murine colitis, attenuated inflammatory cell infiltration and more. And it was showed that the imbalance of Treg/Th17 cell in the intestinal inflammation caused by DSS was restored after treatment with L.p R3. Similarly, Xu et al. [ 73 ] investigated the effect of Saccharomyces boulardii and its postbiotics on DSS-induced UC in mice, showing that both S. boulardii elements and its postbiotics could significantly alleviate weight loss, reduce colonic tissue damage, regulate the balance of pro/anti-inflammatory cytokines in serum and colon, promote the expression of colonic tight junction proteins, and regulate the stability of intestinal microecology in mice. Changing in the bacterial flora were characterized by a significant increase in Turcibacter at the genus level, which collectively attenuate DSS-induced colitis. Komaki et al. [ 74 ] administered Lactococcus lactis subsp.lactis JCM5850 to mices with colitis induced by DSS and found that moderate amounts of L. lactis had a mitigating effect on colitis. In keeping with these results, Hizay et al. [ 75 ] also found that Lactobacillus acidophilus reduces abnormally high levels of serotonin in colon tissue in acetic acid-induced UC and relieves inflammation in intestinal tissue. As with the results above, Gao et al. [ 76 ] made Saccharomyces boulardii into suspension, observing its effect on DSS induced colitis in mice. The results suggested that S. boulardii can alleviate the clinical symotoms of colitis in mice exposed to DSS and the histological lesions. And it was found that the mechanism of S. boulardii to treat UC is inhibite nuclear transcription factor kappa B (NF-κB) and activate nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway. As demonstrated by He [ 77 ] et al., Enterococcus faecium administration prevented DSS-induced intestinal inflammation and intestinal flora dysbiosis and particially repaired the damage to intestinal mucosal barrier and tight junctions. The modulatory effect on intestinal flora was characterized by an increase in Butyricicoccus sp., Lactobacillus sp., and Bifidobacterium sp. and a decrease in Ochrobactrum sp. and Acinetobacter sp. .

By studying the effects of tetrapeptide from maize (TPM) and probiotic (5 Lactobacillus strains: L.animalis- BA12, L.bulgaricus- LB42, L.paracasei- LC86, L.casei- LC89 and L.plantarum- LP90) in mice with DSS-induced UC, Li et al. [ 78 ] found that it could reduce the level of oxidative stress, attenuate the loss of kidney and colon, and regulate the intestinal flora to alleviate the inflammatory effects of UC. Wherein, the modulation effect to gut microbiota in manifested as an increase in Muribaculaceae, Alistipes, Ligilactobacillus and Lactobacillus . Recently, Shang et al. [ 79 ] reported that Bifidobacterium bifidum H3-R2 can effectively alleviate of pathogenesis by inhibiting inflammatory signaling, maintaining intestinal ecological homeostasis, and protecting colonic integrity. B.bifidum H3-R2 administration similarly affected the composition of gut microbiota, showing that B.bifidum H3-R2 caused a significant increase in the abundance of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus and a decrease in Enterobacter , Enterococcus and Streptococcus . Chen et al. [ 80 ] also discovered Lactobacillus fermentum ZS40 could inhibit DSS-induced mice colon shortening, colon damage, and intestinal wall thickening. It does so by inhibiting the activation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, and ultimately relieved inflammation.

To sum up, these results provide important clues for the design and use of more effective probiotic agents to treat UC and may provide new insights into the mechanisms by which host-microbe interactions confer the protective effect. And probiotics as additionally supplemented active micro-organisms, may have better value in clinical applications as drugs in the future [ 81 ].

Clinical studies