While Sandel argues that pursuing perfection through genetic engineering would decrease our sense of humility, he claims that the sense of solidarity we would lose is also important.

This thesis summarizes several points in Sandel’s argument, but it does not make a claim about how we should understand his argument. A reader who read Sandel’s argument would not also need to read an essay based on this descriptive thesis.

Broad thesis (arguable, but difficult to support with evidence)

Michael Sandel’s arguments about genetic engineering do not take into consideration all the relevant issues.

This is an arguable claim because it would be possible to argue against it by saying that Michael Sandel’s arguments do take all of the relevant issues into consideration. But the claim is too broad. Because the thesis does not specify which “issues” it is focused on—or why it matters if they are considered—readers won’t know what the rest of the essay will argue, and the writer won’t know what to focus on. If there is a particular issue that Sandel does not address, then a more specific version of the thesis would include that issue—hand an explanation of why it is important.

Arguable thesis with analytical claim

While Sandel argues persuasively that our instinct to “remake” (54) ourselves into something ever more perfect is a problem, his belief that we can always draw a line between what is medically necessary and what makes us simply “better than well” (51) is less convincing.

This is an arguable analytical claim. To argue for this claim, the essay writer will need to show how evidence from the article itself points to this interpretation. It’s also a reasonable scope for a thesis because it can be supported with evidence available in the text and is neither too broad nor too narrow.

Arguable thesis with normative claim

Given Sandel’s argument against genetic enhancement, we should not allow parents to decide on using Human Growth Hormone for their children.

This thesis tells us what we should do about a particular issue discussed in Sandel’s article, but it does not tell us how we should understand Sandel’s argument.

Questions to ask about your thesis

- Is the thesis truly arguable? Does it speak to a genuine dilemma in the source, or would most readers automatically agree with it?

- Is the thesis too obvious? Again, would most or all readers agree with it without needing to see your argument?

- Is the thesis complex enough to require a whole essay's worth of argument?

- Is the thesis supportable with evidence from the text rather than with generalizations or outside research?

- Would anyone want to read a paper in which this thesis was developed? That is, can you explain what this paper is adding to our understanding of a problem, question, or topic?

- picture_as_pdf Thesis

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement: 4 Steps + Examples

What’s Covered:

What is the purpose of a thesis statement, writing a good thesis statement: 4 steps, common pitfalls to avoid, where to get your essay edited for free.

When you set out to write an essay, there has to be some kind of point to it, right? Otherwise, your essay would just be a big jumble of word salad that makes absolutely no sense. An essay needs a central point that ties into everything else. That main point is called a thesis statement, and it’s the core of any essay or research paper.

You may hear about Master degree candidates writing a thesis, and that is an entire paper–not to be confused with the thesis statement, which is typically one sentence that contains your paper’s focus.

Read on to learn more about thesis statements and how to write them. We’ve also included some solid examples for you to reference.

Typically the last sentence of your introductory paragraph, the thesis statement serves as the roadmap for your essay. When your reader gets to the thesis statement, they should have a clear outline of your main point, as well as the information you’ll be presenting in order to either prove or support your point.

The thesis statement should not be confused for a topic sentence , which is the first sentence of every paragraph in your essay. If you need help writing topic sentences, numerous resources are available. Topic sentences should go along with your thesis statement, though.

Since the thesis statement is the most important sentence of your entire essay or paper, it’s imperative that you get this part right. Otherwise, your paper will not have a good flow and will seem disjointed. That’s why it’s vital not to rush through developing one. It’s a methodical process with steps that you need to follow in order to create the best thesis statement possible.

Step 1: Decide what kind of paper you’re writing

When you’re assigned an essay, there are several different types you may get. Argumentative essays are designed to get the reader to agree with you on a topic. Informative or expository essays present information to the reader. Analytical essays offer up a point and then expand on it by analyzing relevant information. Thesis statements can look and sound different based on the type of paper you’re writing. For example:

- Argumentative: The United States needs a viable third political party to decrease bipartisanship, increase options, and help reduce corruption in government.

- Informative: The Libertarian party has thrown off elections before by gaining enough support in states to get on the ballot and by taking away crucial votes from candidates.

- Analytical: An analysis of past presidential elections shows that while third party votes may have been the minority, they did affect the outcome of the elections in 2020, 2016, and beyond.

Step 2: Figure out what point you want to make

Once you know what type of paper you’re writing, you then need to figure out the point you want to make with your thesis statement, and subsequently, your paper. In other words, you need to decide to answer a question about something, such as:

- What impact did reality TV have on American society?

- How has the musical Hamilton affected perception of American history?

- Why do I want to major in [chosen major here]?

If you have an argumentative essay, then you will be writing about an opinion. To make it easier, you may want to choose an opinion that you feel passionate about so that you’re writing about something that interests you. For example, if you have an interest in preserving the environment, you may want to choose a topic that relates to that.

If you’re writing your college essay and they ask why you want to attend that school, you may want to have a main point and back it up with information, something along the lines of:

“Attending Harvard University would benefit me both academically and professionally, as it would give me a strong knowledge base upon which to build my career, develop my network, and hopefully give me an advantage in my chosen field.”

Step 3: Determine what information you’ll use to back up your point

Once you have the point you want to make, you need to figure out how you plan to back it up throughout the rest of your essay. Without this information, it will be hard to either prove or argue the main point of your thesis statement. If you decide to write about the Hamilton example, you may decide to address any falsehoods that the writer put into the musical, such as:

“The musical Hamilton, while accurate in many ways, leaves out key parts of American history, presents a nationalist view of founding fathers, and downplays the racism of the times.”

Once you’ve written your initial working thesis statement, you’ll then need to get information to back that up. For example, the musical completely leaves out Benjamin Franklin, portrays the founding fathers in a nationalist way that is too complimentary, and shows Hamilton as a staunch abolitionist despite the fact that his family likely did own slaves.

Step 4: Revise and refine your thesis statement before you start writing

Read through your thesis statement several times before you begin to compose your full essay. You need to make sure the statement is ironclad, since it is the foundation of the entire paper. Edit it or have a peer review it for you to make sure everything makes sense and that you feel like you can truly write a paper on the topic. Once you’ve done that, you can then begin writing your paper.

When writing a thesis statement, there are some common pitfalls you should avoid so that your paper can be as solid as possible. Make sure you always edit the thesis statement before you do anything else. You also want to ensure that the thesis statement is clear and concise. Don’t make your reader hunt for your point. Finally, put your thesis statement at the end of the first paragraph and have your introduction flow toward that statement. Your reader will expect to find your statement in its traditional spot.

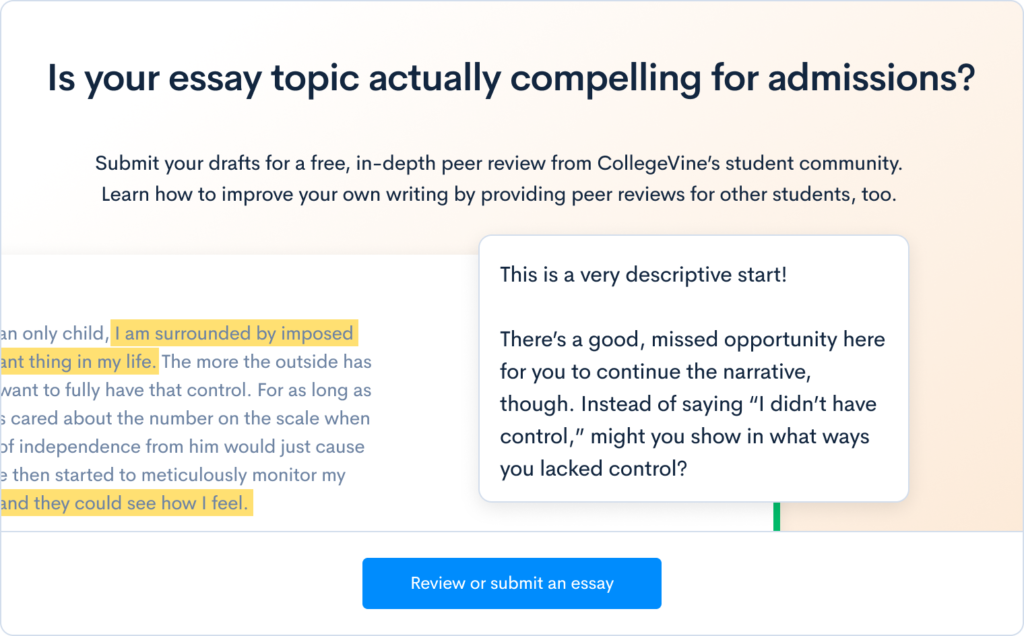

If you’re having trouble getting started, or need some guidance on your essay, there are tools available that can help you. CollegeVine offers a free peer essay review tool where one of your peers can read through your essay and provide you with valuable feedback. Getting essay feedback from a peer can help you wow your instructor or college admissions officer with an impactful essay that effectively illustrates your point.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

It appears you have javascript disabled. Please enable javascript to get the full experience of gustavus.edu

Tips on writing a thesis statement: composing compelling thesis statements.

College-level courses demand a solid grasp of writing concepts, and some students arrive at Intro to Composition unprepared to write a high-quality essay. Teachers tend to give a bit more slack at the high school level, but college professors are often much more exacting. That’s why excellent writing skills are crucial to the majority of college courses — even outside the English department.

One of the most important elements to master is the thesis statement. A strong thesis statement is at the root of all writing, from op-eds to research papers. It’s an essential element of any persuasive piece; something we look for without even thinking about it. A convincing, attention-grabbing thesis statement keeps the reader engaged — and lets them know where the piece is headed.

Having a few tips and tricks in your toolbox can help you to make a convincing academic argument every time.

What is a Thesis Statement?

First, the basics. A thesis statement is a sentence or two that states the main idea of a writing assignment. It also helps to control the ideas presented within the paper. However, it is not merely a topic. It often reflects a claim or judgment that a writer has made about a reading or personal experience. For instance: Tocqueville believed that the domestic role most women held in America was the role that gave them the most power, an idea that many would hotly dispute today.

Every assignment has a question or prompt. It’s important that your thesis statement answers the question. For the above thesis statement, the question being answered might be something like this: Why was Tocqueville wrong about women? If your thesis statement doesn’t answer a question, you’ll need to rework your statement.

Where Will I Use Thesis Statements?

Writing an exceptional thesis statement is a skill you’ll need both now and in the future, so you’ll want to be confident in your ability to create a great one. Whether in academic, professional, or personal writing, a strong thesis statement enhances the clarity, effectiveness, and impact of the overall message. Here are some real-world examples that demonstrate the importance of composing an outstanding thesis statement:

- Academic writing. The success of academic research papers depends on an exceptional thesis statement. Along with establishing the focus of the paper, it also provides you with direction in terms of research. The thesis sets a clear intention for your essay, helping the reader understand the argument you’re presenting and why the evidence and analysis support it.

- Persuasive writing. Persuasive writing depends on an excellent thesis statement that clearly defines the author’s position. Your goal is to persuade the audience to agree with your thesis. Setting an explicit stance also provides you with a foundation on which to build convincing arguments with relevant evidence.

- Professional writing. In the business and marketing world, a sound thesis statement is required to communicate a project’s purpose. Thesis statements not only outline a project’s unique goals but can also guide the marketing team in creating targeted promotional strategies.

Where Do Thesis Statements Go?

A good practice is to put the thesis statement at the end of your introduction so you can use it to lead into the body of your paper. This allows you, as the writer, to lead up to the thesis statement instead of diving directly into the topic. Placing your thesis here also sets you up for a brief mention of the evidence you have to support your thesis, allowing readers a preview of what’s to come.

A good introduction conceptualizes and anticipates the thesis statement, so ending your intro with your thesis makes the most sense. If you place the thesis statement at the beginning, your reader may forget or be confused about the main idea by the time they reach the end of the introduction.

What Makes a Strong Thesis Statement?

A quality thesis statement is designed to both inform and compel. Your thesis acts as an introduction to the argument you’ll be making in your paper, and it also acts as the “hook”. Your thesis should be clear and concise, and you should be ready with enough evidence to support your argument.

There are several qualities that make for a powerful thesis statement, and drafting a great one means considering all of them:

A strong thesis makes a clear argument .

A thesis statement is not intended to be a statement of fact, nor should it be an opinion statement. Making an observation is not sufficient — you should provide the reader with a clear argument that cohesively summarizes the intention of your paper.

Originality is important when possible, but stick with your own convictions. Taking your paper in an already agreed-upon direction doesn’t necessarily make for compelling reading. Writing a thesis statement that presents a unique argument opens up the opportunity to discuss an issue in a new way and helps readers to get a new perspective on the topic in question. Again, don’t force it. You’ll have a harder time trying to support an argument you don’t believe yourself.

A strong thesis statement gives direction .

If you lack a specific direction for your paper, you’ll likely find it difficult to make a solid argument for anything. Your thesis statement should state precisely what your paper will be about, as a statement that’s overly general or makes more than one main point can confuse your audience.

A specific thesis statement also helps you focus your argument — you should be able to discuss your thesis thoroughly in the allotted word count. A thesis that’s too broad won’t allow you to make a strong case for anything.

A strong thesis statement provides proof.

Since thesis statements present an argument, they require support. All paragraphs of the essay should explain, support, or argue with your thesis. You should support your thesis statement with detailed evidence that will interest your readers and motivate them to continue reading the paper.

Sometimes it is useful to mention your supporting points in your thesis. An example of this could be: John Updike's Trust Me is a valuable novel for a college syllabus because it allows the reader to become familiar with his writing and provides themes that are easily connected to other works. In the body of your paper, you could write a paragraph or two about each supporting idea. If you write a thesis statement like this, it will often help you to keep control of your ideas.

A strong thesis statement prompts discussion .

Your thesis statement should stimulate the reader to continue reading your paper. Many writers choose to illustrate that the chosen topic is controversial in one way or another, which is an effective way to pull in readers who might agree with you and those who don’t!

The ultimate point of a thesis statement is to spark interest in your argument. This is your chance to grab (and keep) your reader’s attention, and hopefully, inspire them to continue learning about the topic.

Testing Your Thesis Statement

Because your thesis statement is vital to the quality of your paper, you need to ensure that your thesis statement posits a cohesive argument. Once you’ve come up with a working thesis statement, ask yourself these questions to further refine your statement:

- Is it interesting ? If your thesis is dull, consider clarifying your argument or revising it to make a connection to a relatable issue. Again, your thesis statement should draw the reader into the paper.

- Is it specific enough ? If your thesis statement is too broad, you won’t be able to make a persuasive argument. If your thesis contains words like “positive” or “effective”, narrow it down. Tell the reader why something is “positive”. What in particular makes something “effective”?

- Does it answer the question ? Review the prompt or question once you’ve written your working thesis and be sure that your thesis statement directly addresses the given question.

- Does my paper successfully support my thesis statement ? If you find that your thesis statement and the body of your paper don’t mesh well, you’re going to have to change one of them. But don’t worry too much if this is the case — writing is intended to be revised and reworked.

- Does my thesis statement present the reader with a new perspective? Is it a fresh take on an old idea? Will my reader learn something from my paper? If your thesis statement has already been widely discussed, consider if there’s a fresh angle to take before settling.

- Finally, am I happy with my thesis ? If not, you may have difficulty writing your paper. Composing an essay about an argument you don’t believe in can be more difficult than taking a stand for something you believe in.

Quick Tips for Writing Thesis Statements

If you’re struggling to come up with a thesis statement, here are a few tips you can use to help:

- Know the topic. The topic should be something you know or can learn about. It is difficult to write a thesis statement, let alone a paper, on a topic that you know nothing about. Reflecting on personal experience and/or researching your thesis topic thoroughly will help you present more convincing information about your statement.

- Brainstorm. If you are having trouble beginning your paper or writing your thesis, take a piece of paper and write down everything that comes to mind about your topic. Did you discover any new ideas or connections? Can you separate any of the things you jotted down into categories? Do you notice any themes? Think about using ideas generated during this process to shape your thesis statement and your paper.

- Phrase the topic as a question. If your topic is presented as a statement, rephrasing it as a question can make it easier to develop a thesis statement.

- Limit your topic. Based on what you know and the required length of your final paper, limit your topic to a specific area. A broad scope will generally require a longer paper, while a narrow scope can be sufficiently proven by a shorter paper.

Writing Thesis Statements: Final Thoughts

The ability to compose a strong thesis statement is a skill you’ll use over and over again during your college days and beyond. Compelling persuasive writing is important, whether you’re writing an academic essay or putting together a professional pitch.

If your thesis statement-writing skills aren’t already strong, be sure to practice before diving into college-level courses that will test your skills. If you’re currently looking into colleges, Gustavus Adolphus offers you the opportunity to refine your writing skills in our English courses and degree program . Explore Gustavus Adolphus’ undergraduate majors here .

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

How to write a thesis statement, what is a thesis statement.

Almost all of us—even if we don’t do it consciously—look early in an essay for a one- or two-sentence condensation of the argument or analysis that is to follow. We refer to that condensation as a thesis statement.

Why Should Your Essay Contain a Thesis Statement?

- to test your ideas by distilling them into a sentence or two

- to better organize and develop your argument

- to provide your reader with a “guide” to your argument

In general, your thesis statement will accomplish these goals if you think of the thesis as the answer to the question your paper explores.

How Can You Write a Good Thesis Statement?

Here are some helpful hints to get you started. You can either scroll down or select a link to a specific topic.

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned

Almost all assignments, no matter how complicated, can be reduced to a single question. Your first step, then, is to distill the assignment into a specific question. For example, if your assignment is, “Write a report to the local school board explaining the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class,” turn the request into a question like, “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” After you’ve chosen the question your essay will answer, compose one or two complete sentences answering that question.

Q: “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” A: “The potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class are . . .”

A: “Using computers in a fourth-grade class promises to improve . . .”

The answer to the question is the thesis statement for the essay.

[ Back to top ]

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned

Even if your assignment doesn’t ask a specific question, your thesis statement still needs to answer a question about the issue you’d like to explore. In this situation, your job is to figure out what question you’d like to write about.

A good thesis statement will usually include the following four attributes:

- take on a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree

- deal with a subject that can be adequately treated given the nature of the assignment

- express one main idea

- assert your conclusions about a subject

Let’s see how to generate a thesis statement for a social policy paper.

Brainstorm the topic . Let’s say that your class focuses upon the problems posed by changes in the dietary habits of Americans. You find that you are interested in the amount of sugar Americans consume.

You start out with a thesis statement like this:

Sugar consumption.

This fragment isn’t a thesis statement. Instead, it simply indicates a general subject. Furthermore, your reader doesn’t know what you want to say about sugar consumption.

Narrow the topic . Your readings about the topic, however, have led you to the conclusion that elementary school children are consuming far more sugar than is healthy.

You change your thesis to look like this:

Reducing sugar consumption by elementary school children.

This fragment not only announces your subject, but it focuses on one segment of the population: elementary school children. Furthermore, it raises a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree, because while most people might agree that children consume more sugar than they used to, not everyone would agree on what should be done or who should do it. You should note that this fragment is not a thesis statement because your reader doesn’t know your conclusions on the topic.

Take a position on the topic. After reflecting on the topic a little while longer, you decide that what you really want to say about this topic is that something should be done to reduce the amount of sugar these children consume.

You revise your thesis statement to look like this:

More attention should be paid to the food and beverage choices available to elementary school children.

This statement asserts your position, but the terms more attention and food and beverage choices are vague.

Use specific language . You decide to explain what you mean about food and beverage choices , so you write:

Experts estimate that half of elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar.

This statement is specific, but it isn’t a thesis. It merely reports a statistic instead of making an assertion.

Make an assertion based on clearly stated support. You finally revise your thesis statement one more time to look like this:

Because half of all American elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar, schools should be required to replace the beverages in soda machines with healthy alternatives.

Notice how the thesis answers the question, “What should be done to reduce sugar consumption by children, and who should do it?” When you started thinking about the paper, you may not have had a specific question in mind, but as you became more involved in the topic, your ideas became more specific. Your thesis changed to reflect your new insights.

How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

1. a strong thesis statement takes some sort of stand..

Remember that your thesis needs to show your conclusions about a subject. For example, if you are writing a paper for a class on fitness, you might be asked to choose a popular weight-loss product to evaluate. Here are two thesis statements:

There are some negative and positive aspects to the Banana Herb Tea Supplement.

This is a weak thesis statement. First, it fails to take a stand. Second, the phrase negative and positive aspects is vague.

Because Banana Herb Tea Supplement promotes rapid weight loss that results in the loss of muscle and lean body mass, it poses a potential danger to customers.

This is a strong thesis because it takes a stand, and because it's specific.

2. A strong thesis statement justifies discussion.

Your thesis should indicate the point of the discussion. If your assignment is to write a paper on kinship systems, using your own family as an example, you might come up with either of these two thesis statements:

My family is an extended family.

This is a weak thesis because it merely states an observation. Your reader won’t be able to tell the point of the statement, and will probably stop reading.

While most American families would view consanguineal marriage as a threat to the nuclear family structure, many Iranian families, like my own, believe that these marriages help reinforce kinship ties in an extended family.

This is a strong thesis because it shows how your experience contradicts a widely-accepted view. A good strategy for creating a strong thesis is to show that the topic is controversial. Readers will be interested in reading the rest of the essay to see how you support your point.

3. A strong thesis statement expresses one main idea.

Readers need to be able to see that your paper has one main point. If your thesis statement expresses more than one idea, then you might confuse your readers about the subject of your paper. For example:

Companies need to exploit the marketing potential of the Internet, and Web pages can provide both advertising and customer support.

This is a weak thesis statement because the reader can’t decide whether the paper is about marketing on the Internet or Web pages. To revise the thesis, the relationship between the two ideas needs to become more clear. One way to revise the thesis would be to write:

Because the Internet is filled with tremendous marketing potential, companies should exploit this potential by using Web pages that offer both advertising and customer support.

This is a strong thesis because it shows that the two ideas are related. Hint: a great many clear and engaging thesis statements contain words like because , since , so , although , unless , and however .

4. A strong thesis statement is specific.

A thesis statement should show exactly what your paper will be about, and will help you keep your paper to a manageable topic. For example, if you're writing a seven-to-ten page paper on hunger, you might say:

World hunger has many causes and effects.

This is a weak thesis statement for two major reasons. First, world hunger can’t be discussed thoroughly in seven to ten pages. Second, many causes and effects is vague. You should be able to identify specific causes and effects. A revised thesis might look like this:

Hunger persists in Glandelinia because jobs are scarce and farming in the infertile soil is rarely profitable.

This is a strong thesis statement because it narrows the subject to a more specific and manageable topic, and it also identifies the specific causes for the existence of hunger.

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Writing Tutorial Services social media channels

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a thesis statement + examples

What is a thesis statement?

Is a thesis statement a question, how do you write a good thesis statement, how do i know if my thesis statement is good, examples of thesis statements, helpful resources on how to write a thesis statement, frequently asked questions about writing a thesis statement, related articles.

A thesis statement is the main argument of your paper or thesis.

The thesis statement is one of the most important elements of any piece of academic writing . It is a brief statement of your paper’s main argument. Essentially, you are stating what you will be writing about.

You can see your thesis statement as an answer to a question. While it also contains the question, it should really give an answer to the question with new information and not just restate or reiterate it.

Your thesis statement is part of your introduction. Learn more about how to write a good thesis introduction in our introduction guide .

A thesis statement is not a question. A statement must be arguable and provable through evidence and analysis. While your thesis might stem from a research question, it should be in the form of a statement.

Tip: A thesis statement is typically 1-2 sentences. For a longer project like a thesis, the statement may be several sentences or a paragraph.

A good thesis statement needs to do the following:

- Condense the main idea of your thesis into one or two sentences.

- Answer your project’s main research question.

- Clearly state your position in relation to the topic .

- Make an argument that requires support or evidence.

Once you have written down a thesis statement, check if it fulfills the following criteria:

- Your statement needs to be provable by evidence. As an argument, a thesis statement needs to be debatable.

- Your statement needs to be precise. Do not give away too much information in the thesis statement and do not load it with unnecessary information.

- Your statement cannot say that one solution is simply right or simply wrong as a matter of fact. You should draw upon verified facts to persuade the reader of your solution, but you cannot just declare something as right or wrong.

As previously mentioned, your thesis statement should answer a question.

If the question is:

What do you think the City of New York should do to reduce traffic congestion?

A good thesis statement restates the question and answers it:

In this paper, I will argue that the City of New York should focus on providing exclusive lanes for public transport and adaptive traffic signals to reduce traffic congestion by the year 2035.

Here is another example. If the question is:

How can we end poverty?

A good thesis statement should give more than one solution to the problem in question:

In this paper, I will argue that introducing universal basic income can help reduce poverty and positively impact the way we work.

- The Writing Center of the University of North Carolina has a list of questions to ask to see if your thesis is strong .

A thesis statement is part of the introduction of your paper. It is usually found in the first or second paragraph to let the reader know your research purpose from the beginning.

In general, a thesis statement should have one or two sentences. But the length really depends on the overall length of your project. Take a look at our guide about the length of thesis statements for more insight on this topic.

Here is a list of Thesis Statement Examples that will help you understand better how to write them.

Every good essay should include a thesis statement as part of its introduction, no matter the academic level. Of course, if you are a high school student you are not expected to have the same type of thesis as a PhD student.

Here is a great YouTube tutorial showing How To Write An Essay: Thesis Statements .

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Thesis Statements

Basics of thesis statements.

The thesis statement is the brief articulation of your paper's central argument and purpose. You might hear it referred to as simply a "thesis." Every scholarly paper should have a thesis statement, and strong thesis statements are concise, specific, and arguable. Concise means the thesis is short: perhaps one or two sentences for a shorter paper. Specific means the thesis deals with a narrow and focused topic, appropriate to the paper's length. Arguable means that a scholar in your field could disagree (or perhaps already has!).

Strong thesis statements address specific intellectual questions, have clear positions, and use a structure that reflects the overall structure of the paper. Read on to learn more about constructing a strong thesis statement.

Being Specific

This thesis statement has no specific argument:

Needs Improvement: In this essay, I will examine two scholarly articles to find similarities and differences.

This statement is concise, but it is neither specific nor arguable—a reader might wonder, "Which scholarly articles? What is the topic of this paper? What field is the author writing in?" Additionally, the purpose of the paper—to "examine…to find similarities and differences" is not of a scholarly level. Identifying similarities and differences is a good first step, but strong academic argument goes further, analyzing what those similarities and differences might mean or imply.

Better: In this essay, I will argue that Bowler's (2003) autocratic management style, when coupled with Smith's (2007) theory of social cognition, can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover.

The new revision here is still concise, as well as specific and arguable. We can see that it is specific because the writer is mentioning (a) concrete ideas and (b) exact authors. We can also gather the field (business) and the topic (management and employee turnover). The statement is arguable because the student goes beyond merely comparing; he or she draws conclusions from that comparison ("can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover").

Making a Unique Argument

This thesis draft repeats the language of the writing prompt without making a unique argument:

Needs Improvement: The purpose of this essay is to monitor, assess, and evaluate an educational program for its strengths and weaknesses. Then, I will provide suggestions for improvement.

You can see here that the student has simply stated the paper's assignment, without articulating specifically how he or she will address it. The student can correct this error simply by phrasing the thesis statement as a specific answer to the assignment prompt.

Better: Through a series of student interviews, I found that Kennedy High School's antibullying program was ineffective. In order to address issues of conflict between students, I argue that Kennedy High School should embrace policies outlined by the California Department of Education (2010).

Words like "ineffective" and "argue" show here that the student has clearly thought through the assignment and analyzed the material; he or she is putting forth a specific and debatable position. The concrete information ("student interviews," "antibullying") further prepares the reader for the body of the paper and demonstrates how the student has addressed the assignment prompt without just restating that language.

Creating a Debate

This thesis statement includes only obvious fact or plot summary instead of argument:

Needs Improvement: Leadership is an important quality in nurse educators.

A good strategy to determine if your thesis statement is too broad (and therefore, not arguable) is to ask yourself, "Would a scholar in my field disagree with this point?" Here, we can see easily that no scholar is likely to argue that leadership is an unimportant quality in nurse educators. The student needs to come up with a more arguable claim, and probably a narrower one; remember that a short paper needs a more focused topic than a dissertation.

Better: Roderick's (2009) theory of participatory leadership is particularly appropriate to nurse educators working within the emergency medicine field, where students benefit most from collegial and kinesthetic learning.

Here, the student has identified a particular type of leadership ("participatory leadership"), narrowing the topic, and has made an arguable claim (this type of leadership is "appropriate" to a specific type of nurse educator). Conceivably, a scholar in the nursing field might disagree with this approach. The student's paper can now proceed, providing specific pieces of evidence to support the arguable central claim.

Choosing the Right Words

This thesis statement uses large or scholarly-sounding words that have no real substance:

Needs Improvement: Scholars should work to seize metacognitive outcomes by harnessing discipline-based networks to empower collaborative infrastructures.

There are many words in this sentence that may be buzzwords in the student's field or key terms taken from other texts, but together they do not communicate a clear, specific meaning. Sometimes students think scholarly writing means constructing complex sentences using special language, but actually it's usually a stronger choice to write clear, simple sentences. When in doubt, remember that your ideas should be complex, not your sentence structure.

Better: Ecologists should work to educate the U.S. public on conservation methods by making use of local and national green organizations to create a widespread communication plan.

Notice in the revision that the field is now clear (ecology), and the language has been made much more field-specific ("conservation methods," "green organizations"), so the reader is able to see concretely the ideas the student is communicating.

Leaving Room for Discussion

This thesis statement is not capable of development or advancement in the paper:

Needs Improvement: There are always alternatives to illegal drug use.

This sample thesis statement makes a claim, but it is not a claim that will sustain extended discussion. This claim is the type of claim that might be appropriate for the conclusion of a paper, but in the beginning of the paper, the student is left with nowhere to go. What further points can be made? If there are "always alternatives" to the problem the student is identifying, then why bother developing a paper around that claim? Ideally, a thesis statement should be complex enough to explore over the length of the entire paper.

Better: The most effective treatment plan for methamphetamine addiction may be a combination of pharmacological and cognitive therapy, as argued by Baker (2008), Smith (2009), and Xavier (2011).

In the revised thesis, you can see the student make a specific, debatable claim that has the potential to generate several pages' worth of discussion. When drafting a thesis statement, think about the questions your thesis statement will generate: What follow-up inquiries might a reader have? In the first example, there are almost no additional questions implied, but the revised example allows for a good deal more exploration.

Thesis Mad Libs

If you are having trouble getting started, try using the models below to generate a rough model of a thesis statement! These models are intended for drafting purposes only and should not appear in your final work.

- In this essay, I argue ____, using ______ to assert _____.

- While scholars have often argued ______, I argue______, because_______.

- Through an analysis of ______, I argue ______, which is important because_______.

Words to Avoid and to Embrace

When drafting your thesis statement, avoid words like explore, investigate, learn, compile, summarize , and explain to describe the main purpose of your paper. These words imply a paper that summarizes or "reports," rather than synthesizing and analyzing.

Instead of the terms above, try words like argue, critique, question , and interrogate . These more analytical words may help you begin strongly, by articulating a specific, critical, scholarly position.

Read Kayla's blog post for tips on taking a stand in a well-crafted thesis statement.

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Introductions

- Next Page: Conclusions

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- Enroll & Pay

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

Thesis Statements

Thesis statements establish for your readers both the relationship between the ideas and the order in which the material will be presented. As the writer, you can use the thesis statement as a guide in developing a coherent argument. In the thesis statement you are not simply describing or recapitulating the material; you are taking a specific position that you need to defend . A well-written thesis is a tool for both the writer and reader, reminding the writer of the direction of the text and acting as a "road sign" that lets the reader know what to expect.

A thesis statement has two purposes: (1) to educate a group of people (the audience) on a subject within the chosen topic, and (2) to inspire further reactions and spur conversation. Thesis statements are not written in stone. As you research and explore your subject matter, you are bound to find new or differing points of views, and your response may change. You identify the audience, and your thesis speaks to that particular audience.

Preparing to Write Your Thesis: Narrowing Your Topic

Before writing your thesis statement, you should work to narrow your topic. Focus statements will help you stay on track as you delve into research and explore your topic.

- I am researching ________to better understand ________.

- My paper hopes to uncover ________about ________.

- How does ________relate to ________?

- How does ________work?

- Why is ________ happening?

- What is missing from the ________ debate?

- What is missing from the current understanding of ________?

Other questions to consider:

- How do I state the assigned topic clearly and succinctly?

- What are the most interesting and relevant aspects of the topic?

- In what order do I want to present the various aspects, and how do my ideas relate to each other?

- What is my point of view regarding the topic?

Writing a Thesis Statement

Thesis statements typically consist of a single sentence and stress the main argument or claim of your paper. More often than not, the thesis statement comes at the end of your introduction paragraph; however, this can vary based on discipline and topic, so check with your instructor if you are unsure where to place it.

Thesis statement should include three main components:

- TOPIC – the topic you are discussing (school uniforms in public secondary schools)

- CONTROLLING IDEA – the point you are making about the topic or significance of your idea in terms of understanding your position as a whole (should be required)

- REASONING – the supporting reasons, events, ideas, sources, etc. that you choose to prove your claim in the order you will discuss them. This section varies by type of essay and level of writing. In some cases, it may be left out (because they are more inclusive and foster unity)

A Strategy to Form Your Own Thesis Statement

Using the topic information, develop this formulaic sentence:

I am writing about_______________, and I am going to argue, show, or prove___________.

What you wrote in the first blank is the topic of your paper; what you wrote in the second blank is what focuses your paper (suggested by Patrick Hartwell in Open to Language ). For example, a sentence might be:

I am going to write about senior citizens who volunteer at literacy projects, and I am going to show that they are physically and mentally invigorated by the responsibility of volunteering.

Next, refine the sentence so that it is consistent with your style. For example:

Senior citizens who volunteer at literacy projects are invigorated physically and mentally by the responsibility of volunteering.

Here is a second example illustrating the formulation of another thesis statement. First, read this sentence that includes both topic and focusing comment:

I am going to write about how Plato and Sophocles understand the proper role of women in Greek society, and I am going to argue that though they remain close to traditional ideas about women, the authors also introduce some revolutionary views which increase women's place in society.

Now read the refined sentence, consistent with your style:

When examining the role of women in society, Plato and Sophocles remain close to traditional ideas about women's duties and capabilities in society; however, the authors also introduce some revolutionary views which increase women's place in society.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.1 Developing a Strong, Clear Thesis Statement

Learning objectives.

- Develop a strong, clear thesis statement with the proper elements.

- Revise your thesis statement.

Have you ever known a person who was not very good at telling stories? You probably had trouble following his train of thought as he jumped around from point to point, either being too brief in places that needed further explanation or providing too many details on a meaningless element. Maybe he told the end of the story first, then moved to the beginning and later added details to the middle. His ideas were probably scattered, and the story did not flow very well. When the story was over, you probably had many questions.

Just as a personal anecdote can be a disorganized mess, an essay can fall into the same trap of being out of order and confusing. That is why writers need a thesis statement to provide a specific focus for their essay and to organize what they are about to discuss in the body.

Just like a topic sentence summarizes a single paragraph, the thesis statement summarizes an entire essay. It tells the reader the point you want to make in your essay, while the essay itself supports that point. It is like a signpost that signals the essay’s destination. You should form your thesis before you begin to organize an essay, but you may find that it needs revision as the essay develops.

Elements of a Thesis Statement

For every essay you write, you must focus on a central idea. This idea stems from a topic you have chosen or been assigned or from a question your teacher has asked. It is not enough merely to discuss a general topic or simply answer a question with a yes or no. You have to form a specific opinion, and then articulate that into a controlling idea —the main idea upon which you build your thesis.

Remember that a thesis is not the topic itself, but rather your interpretation of the question or subject. For whatever topic your professor gives you, you must ask yourself, “What do I want to say about it?” Asking and then answering this question is vital to forming a thesis that is precise, forceful and confident.

A thesis is one sentence long and appears toward the end of your introduction. It is specific and focuses on one to three points of a single idea—points that are able to be demonstrated in the body. It forecasts the content of the essay and suggests how you will organize your information. Remember that a thesis statement does not summarize an issue but rather dissects it.

A Strong Thesis Statement

A strong thesis statement contains the following qualities.

Specificity. A thesis statement must concentrate on a specific area of a general topic. As you may recall, the creation of a thesis statement begins when you choose a broad subject and then narrow down its parts until you pinpoint a specific aspect of that topic. For example, health care is a broad topic, but a proper thesis statement would focus on a specific area of that topic, such as options for individuals without health care coverage.

Precision. A strong thesis statement must be precise enough to allow for a coherent argument and to remain focused on the topic. If the specific topic is options for individuals without health care coverage, then your precise thesis statement must make an exact claim about it, such as that limited options exist for those who are uninsured by their employers. You must further pinpoint what you are going to discuss regarding these limited effects, such as whom they affect and what the cause is.

Ability to be argued. A thesis statement must present a relevant and specific argument. A factual statement often is not considered arguable. Be sure your thesis statement contains a point of view that can be supported with evidence.

Ability to be demonstrated. For any claim you make in your thesis, you must be able to provide reasons and examples for your opinion. You can rely on personal observations in order to do this, or you can consult outside sources to demonstrate that what you assert is valid. A worthy argument is backed by examples and details.

Forcefulness. A thesis statement that is forceful shows readers that you are, in fact, making an argument. The tone is assertive and takes a stance that others might oppose.

Confidence. In addition to using force in your thesis statement, you must also use confidence in your claim. Phrases such as I feel or I believe actually weaken the readers’ sense of your confidence because these phrases imply that you are the only person who feels the way you do. In other words, your stance has insufficient backing. Taking an authoritative stance on the matter persuades your readers to have faith in your argument and open their minds to what you have to say.

Even in a personal essay that allows the use of first person, your thesis should not contain phrases such as in my opinion or I believe . These statements reduce your credibility and weaken your argument. Your opinion is more convincing when you use a firm attitude.

On a separate sheet of paper, write a thesis statement for each of the following topics. Remember to make each statement specific, precise, demonstrable, forceful and confident.

- Texting while driving

- The legal drinking age in the United States

- Steroid use among professional athletes

Examples of Appropriate Thesis Statements

Each of the following thesis statements meets several of the following requirements:

- Specificity

- Ability to be argued

- Ability to be demonstrated

- Forcefulness

- The societal and personal struggles of Troy Maxon in the play Fences symbolize the challenge of black males who lived through segregation and integration in the United States.

- Closing all American borders for a period of five years is one solution that will tackle illegal immigration.

- Shakespeare’s use of dramatic irony in Romeo and Juliet spoils the outcome for the audience and weakens the plot.

- J. D. Salinger’s character in Catcher in the Rye , Holden Caulfield, is a confused rebel who voices his disgust with phonies, yet in an effort to protect himself, he acts like a phony on many occasions.

- Compared to an absolute divorce, no-fault divorce is less expensive, promotes fairer settlements, and reflects a more realistic view of the causes for marital breakdown.

- Exposing children from an early age to the dangers of drug abuse is a sure method of preventing future drug addicts.

- In today’s crumbling job market, a high school diploma is not significant enough education to land a stable, lucrative job.

You can find thesis statements in many places, such as in the news; in the opinions of friends, coworkers or teachers; and even in songs you hear on the radio. Become aware of thesis statements in everyday life by paying attention to people’s opinions and their reasons for those opinions. Pay attention to your own everyday thesis statements as well, as these can become material for future essays.

Now that you have read about the contents of a good thesis statement and have seen examples, take a look at the pitfalls to avoid when composing your own thesis:

A thesis is weak when it is simply a declaration of your subject or a description of what you will discuss in your essay.

Weak thesis statement: My paper will explain why imagination is more important than knowledge.

A thesis is weak when it makes an unreasonable or outrageous claim or insults the opposing side.

Weak thesis statement: Religious radicals across America are trying to legislate their Puritanical beliefs by banning required high school books.

A thesis is weak when it contains an obvious fact or something that no one can disagree with or provides a dead end.

Weak thesis statement: Advertising companies use sex to sell their products.

A thesis is weak when the statement is too broad.

Weak thesis statement: The life of Abraham Lincoln was long and challenging.

Read the following thesis statements. On a separate piece of paper, identify each as weak or strong. For those that are weak, list the reasons why. Then revise the weak statements so that they conform to the requirements of a strong thesis.

- The subject of this paper is my experience with ferrets as pets.

- The government must expand its funding for research on renewable energy resources in order to prepare for the impending end of oil.

- Edgar Allan Poe was a poet who lived in Baltimore during the nineteenth century.

- In this essay, I will give you lots of reasons why slot machines should not be legalized in Baltimore.

- Despite his promises during his campaign, President Kennedy took few executive measures to support civil rights legislation.

- Because many children’s toys have potential safety hazards that could lead to injury, it is clear that not all children’s toys are safe.

- My experience with young children has taught me that I want to be a disciplinary parent because I believe that a child without discipline can be a parent’s worst nightmare.

Writing at Work

Often in your career, you will need to ask your boss for something through an e-mail. Just as a thesis statement organizes an essay, it can also organize your e-mail request. While your e-mail will be shorter than an essay, using a thesis statement in your first paragraph quickly lets your boss know what you are asking for, why it is necessary, and what the benefits are. In short body paragraphs, you can provide the essential information needed to expand upon your request.

Thesis Statement Revision

Your thesis will probably change as you write, so you will need to modify it to reflect exactly what you have discussed in your essay. Remember from Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” that your thesis statement begins as a working thesis statement , an indefinite statement that you make about your topic early in the writing process for the purpose of planning and guiding your writing.

Working thesis statements often become stronger as you gather information and form new opinions and reasons for those opinions. Revision helps you strengthen your thesis so that it matches what you have expressed in the body of the paper.

The best way to revise your thesis statement is to ask questions about it and then examine the answers to those questions. By challenging your own ideas and forming definite reasons for those ideas, you grow closer to a more precise point of view, which you can then incorporate into your thesis statement.

Ways to Revise Your Thesis

You can cut down on irrelevant aspects and revise your thesis by taking the following steps:

1. Pinpoint and replace all nonspecific words, such as people , everything , society , or life , with more precise words in order to reduce any vagueness.

Working thesis: Young people have to work hard to succeed in life.

Revised thesis: Recent college graduates must have discipline and persistence in order to find and maintain a stable job in which they can use and be appreciated for their talents.

The revised thesis makes a more specific statement about success and what it means to work hard. The original includes too broad a range of people and does not define exactly what success entails. By replacing those general words like people and work hard , the writer can better focus his or her research and gain more direction in his or her writing.

2. Clarify ideas that need explanation by asking yourself questions that narrow your thesis.

Working thesis: The welfare system is a joke.

Revised thesis: The welfare system keeps a socioeconomic class from gaining employment by alluring members of that class with unearned income, instead of programs to improve their education and skill sets.

A joke means many things to many people. Readers bring all sorts of backgrounds and perspectives to the reading process and would need clarification for a word so vague. This expression may also be too informal for the selected audience. By asking questions, the writer can devise a more precise and appropriate explanation for joke . The writer should ask himself or herself questions similar to the 5WH questions. (See Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” for more information on the 5WH questions.) By incorporating the answers to these questions into a thesis statement, the writer more accurately defines his or her stance, which will better guide the writing of the essay.

3. Replace any linking verbs with action verbs. Linking verbs are forms of the verb to be , a verb that simply states that a situation exists.

Working thesis: Kansas City schoolteachers are not paid enough.

Revised thesis: The Kansas City legislature cannot afford to pay its educators, resulting in job cuts and resignations in a district that sorely needs highly qualified and dedicated teachers.

The linking verb in this working thesis statement is the word are . Linking verbs often make thesis statements weak because they do not express action. Rather, they connect words and phrases to the second half of the sentence. Readers might wonder, “Why are they not paid enough?” But this statement does not compel them to ask many more questions. The writer should ask himself or herself questions in order to replace the linking verb with an action verb, thus forming a stronger thesis statement, one that takes a more definitive stance on the issue:

- Who is not paying the teachers enough?

- What is considered “enough”?

- What is the problem?

- What are the results

4. Omit any general claims that are hard to support.

Working thesis: Today’s teenage girls are too sexualized.

Revised thesis: Teenage girls who are captivated by the sexual images on MTV are conditioned to believe that a woman’s worth depends on her sensuality, a feeling that harms their self-esteem and behavior.

It is true that some young women in today’s society are more sexualized than in the past, but that is not true for all girls. Many girls have strict parents, dress appropriately, and do not engage in sexual activity while in middle school and high school. The writer of this thesis should ask the following questions:

- Which teenage girls?

- What constitutes “too” sexualized?

- Why are they behaving that way?

- Where does this behavior show up?

- What are the repercussions?

In the first section of Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , you determined your purpose for writing and your audience. You then completed a freewriting exercise about an event you recently experienced and chose a general topic to write about. Using that general topic, you then narrowed it down by answering the 5WH questions. After you answered these questions, you chose one of the three methods of prewriting and gathered possible supporting points for your working thesis statement.

Now, on a separate sheet of paper, write down your working thesis statement. Identify any weaknesses in this sentence and revise the statement to reflect the elements of a strong thesis statement. Make sure it is specific, precise, arguable, demonstrable, forceful, and confident.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

In your career you may have to write a project proposal that focuses on a particular problem in your company, such as reinforcing the tardiness policy. The proposal would aim to fix the problem; using a thesis statement would clearly state the boundaries of the problem and tell the goals of the project. After writing the proposal, you may find that the thesis needs revision to reflect exactly what is expressed in the body. Using the techniques from this chapter would apply to revising that thesis.

Key Takeaways

- Proper essays require a thesis statement to provide a specific focus and suggest how the essay will be organized.

- A thesis statement is your interpretation of the subject, not the topic itself.

- A strong thesis is specific, precise, forceful, confident, and is able to be demonstrated.

- A strong thesis challenges readers with a point of view that can be debated and can be supported with evidence.

- A weak thesis is simply a declaration of your topic or contains an obvious fact that cannot be argued.

- Depending on your topic, it may or may not be appropriate to use first person point of view.

- Revise your thesis by ensuring all words are specific, all ideas are exact, and all verbs express action.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Developing a Thesis

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Once you've read the story or novel closely, look back over your notes for patterns of questions or ideas that interest you. Have most of your questions been about the characters, how they develop or change?

For example: If you are reading Conrad's The Secret Agent , do you seem to be most interested in what the author has to say about society? Choose a pattern of ideas and express it in the form of a question and an answer such as the following: Question: What does Conrad seem to be suggesting about early twentieth-century London society in his novel The Secret Agent ? Answer: Conrad suggests that all classes of society are corrupt. Pitfalls: Choosing too many ideas. Choosing an idea without any support.

Once you have some general points to focus on, write your possible ideas and answer the questions that they suggest.

For example: Question: How does Conrad develop the idea that all classes of society are corrupt? Answer: He uses images of beasts and cannibalism whether he's describing socialites, policemen or secret agents.

To write your thesis statement, all you have to do is turn the question and answer around. You've already given the answer, now just put it in a sentence (or a couple of sentences) so that the thesis of your paper is clear.

For example: In his novel, The Secret Agent , Conrad uses beast and cannibal imagery to describe the characters and their relationships to each other. This pattern of images suggests that Conrad saw corruption in every level of early twentieth-century London society.

Now that you're familiar with the story or novel and have developed a thesis statement, you're ready to choose the evidence you'll use to support your thesis. There are a lot of good ways to do this, but all of them depend on a strong thesis for their direction.

For example: Here's a student's thesis about Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent . In his novel, The Secret Agent , Conrad uses beast and cannibal imagery to describe the characters and their relationships to each other. This pattern of images suggests that Conrad saw corruption in every level of early twentieth-century London society. This thesis focuses on the idea of social corruption and the device of imagery. To support this thesis, you would need to find images of beasts and cannibalism within the text.

6.3 Supporting a Thesis

Learning objectives.

- Understand the general goal of writing a paper.

- Be aware of how you can create supporting details.

- Recognize procedures for using supporting details.

Supporting your thesis is the overall goal of your whole paper. It means presenting information that will convince your readers that your thesis makes sense. You need to take care to choose the best supporting details for your thesis.

Creating Supporting Details

You can and should use a variety of kinds of support for your thesis. One of the easiest forms of support to use is personal observations and experiences. The strong point in favor of using personal anecdotes is that they add interest and emotion, both of which can pull audiences along. On the other hand, the anecdotal and subjective nature of personal observations and experiences makes them too weak to support a thesis on their own.

Since they can be verified, facts can help strengthen personal anecdotes by giving them substance and grounding. For example, if you tell a personal anecdote about having lost twenty pounds by using a Hula-Hoop for twenty minutes after every meal, the story seems interesting, but readers might not think it is a serious weight-loss technique. But if you follow up the story with some facts about the benefit of exercising for twenty minutes after every meal, the Hula-Hoop story takes on more credibility. Although facts are undeniably useful in writing projects, a paper full of nothing but fact upon fact would not be very interesting to read.

Like anecdotal information, your opinions can help make facts more interesting. On their own, opinions are weak support for a thesis. But coupled with specific relevant facts, opinions can add a great deal of interest to your work. In addition, opinions are excellent tools for convincing an audience that your thesis makes sense.

Similar to your opinions are details from expert testimony and personal interviews. Both of these kinds of sources provide no shortage of opinions. Expert opinions can carry a little more clout than your own, but you should be careful not to rely too much on them. However, it’s safe to say that finding quality opinions from others and presenting them in support of your ideas will make others more likely to agree with your ideas.

Statistics can provide excellent support for your thesis. Statistics are facts expressed in numbers. For example, say you relay the results of a study that showed that 90 percent of people who exercise for twenty minutes after every meal lose two pounds per week. Such statistics lend strong, credible support to a thesis.

Examples Choices of details used to clarify a point for readers. —real or made up—are powerful tools you can use to clarify and support your facts, opinions, and statistics. A detail that sounds insignificant or meaningless can become quite significant when clarified with an example. For example, you could cite your sister Lydia as an example of someone who lost thirty pounds in a month by exercising after every meal. Using a name and specifics makes it seem very personal and real. As long as you use examples ethically and logically, they can be tremendous assets. On the other hand, when using examples, take care not to intentionally mislead your readers or distort reality. For example, if your sister Lydia also gave birth to a baby during that month, leaving that key bit of information out of the example would be misleading.

Procedures for Using Supporting Details

You are likely to find or think of details that relate to your topic and are interesting, but that do not support your thesis. Including such details in your paper is unwise because they are distracting and irrelevant.

In today’s rich world of technology, you have many options when it comes to choosing sources of information. Make sure you choose only reliable sources. Even if some information sounds absolutely amazing, if it comes from an unreliable source, don’t use it. It might sound amazing for a reason—because it has been amazingly made up.

When you find a new detail, make sure you can find it in at least one more source so you can safely accept it as true. Take this step even when you think the source is reliable because even reliable sources can include errors. When you find new information, make sure to put it into your essay or file of notes right away. Never rely on your memory.

Take great care to organize your supporting details so that they can best support your thesis. One strategy is to list the most powerful information first. Another is to present information in a natural sequence, such as chronological A method of narrative arrangement that places events in their order of occurrence. order. A third option is to use a compare/contrast A writing pattern used to explain how two (or more) things are alike and different. format. Choose whatever method you think will most clearly support your thesis.

Make sure to use at least two or three supporting details for each main idea. In a longer essay, you can easily include more than three supporting details per idea, but in a shorter essay, you might not have space for any more.

Key Takeaways

- A thesis gives an essay a purpose, which is to present details that support the thesis.

- To create supporting details, you can use personal observations and experiences, facts, opinions, statistics, and examples.

- When choosing details for your essay, exclude any that do not support your thesis, make sure you use only reliable sources, double-check your facts for accuracy, organize your details to best support your thesis, and include at least two or three details to support each main idea.

Choose a topic of interest to you. Write a personal observation or experience, a fact, an opinion, a statistic, and an example related to your topic. Present your information in a table with the following headings.

Choose a topic of interest to you. On the Internet, find five reliable sources and five unreliable sources and fill in a table with the following headings.

- Choose a topic of interest to you and write a possible thesis related to the topic. Write one sentence that is both related to the topic and relevant to the thesis. Write one sentence that is related to the topic but not relevant to the thesis.

The future of robotics

Guest Jeannette Bohg is an expert in robotics who says there is transformation happening in her field brought on by recent advances in large language models.

The LLMs have a certain common sense baked in and robots are using it to plan and to reason as never before. But they still lack low-level sensorimotor control – like the fine skill it takes to turn a doorknob. New models that do for robotic control what LLMs did for language could soon make such skills a reality, Bohg tells host Russ Altman on this episode of Stanford Engineering’s The Future of Everything podcast.

Listen on your favorite podcast platform:

Related : Jeannette Bohg , assistant professor of computer science

[00:00:00] Jeannette Bohg: Through things like ChatGPT, we have been able to do reasoning and planning on the high level, meaning kind of on the level of symbols, very well known in robotics, in a very different way that we could do before.

[00:00:17] Russ Altman: This is Stanford Engineering's The Future of Everything, and I'm your host, Russ Altman. If you enjoy The Future of Everything, please hit follow in whatever app you're listening to right now. This will guarantee that you never miss an episode.

[00:00:29] Today, Professor Jeannette Bohg will tell us about robots and the status of robotic work. She'll tell us that ChatGPT is even useful for robots. And that there are huge challenges in getting reliable hardware so we can realize all of our robotic dreams. It's the future of robotics.

[00:00:48] Before we get started, please remember to follow the show and ensure that you'll get alerted to all the new episodes so you'll never miss the future, and I love saying this, of anything.

[00:01:04] Many of us have been thinking about robots since we were little kids. When are we going to get those robots that can make our dinner, clean our house, drive us around, make life really easy? Well, it turns out that there's still some challenges and they're significant for getting robots to work. There are hardware challenges.

[00:01:20] It turns out that the human hand is way better than most robotic manipulators. In addition, robots break. They work in some situations like factories, but those are dangerous robots. They just go right through whatever's in front of them.

[00:01:34] Well, Jeannette Bohg is a computer scientist at Stanford University and an expert on robotics. She's going to tell us that we are making good progress in building reliable hardware and in developing algorithms to help make robots do their thing. What's perhaps most surprising is even ChatGPT is helping the robotics community, even though it just does chats.

[00:01:58] So Jeannette, there's been an increased awareness of AI in the last year, especially because of things like ChatGPT and what they call these large language models. But you work in robotics, you're building robots that sense and move around. Is that AI revolution for like chat, is that affecting your world?