How To Write A Dissertation Or Thesis

8 straightforward steps to craft an a-grade dissertation.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

Writing a dissertation or thesis is not a simple task. It takes time, energy and a lot of will power to get you across the finish line. It’s not easy – but it doesn’t necessarily need to be a painful process. If you understand the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis, your research journey will be a lot smoother.

In this post, I’m going to outline the big-picture process of how to write a high-quality dissertation or thesis, without losing your mind along the way. If you’re just starting your research, this post is perfect for you. Alternatively, if you’ve already submitted your proposal, this article which covers how to structure a dissertation might be more helpful.

How To Write A Dissertation: 8 Steps

- Clearly understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is

- Find a unique and valuable research topic

- Craft a convincing research proposal

- Write up a strong introduction chapter

- Review the existing literature and compile a literature review

- Design a rigorous research strategy and undertake your own research

- Present the findings of your research

- Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Step 1: Understand exactly what a dissertation is

This probably sounds like a no-brainer, but all too often, students come to us for help with their research and the underlying issue is that they don’t fully understand what a dissertation (or thesis) actually is.

So, what is a dissertation?

At its simplest, a dissertation or thesis is a formal piece of research , reflecting the standard research process . But what is the standard research process, you ask? The research process involves 4 key steps:

- Ask a very specific, well-articulated question (s) (your research topic)

- See what other researchers have said about it (if they’ve already answered it)

- If they haven’t answered it adequately, undertake your own data collection and analysis in a scientifically rigorous fashion

- Answer your original question(s), based on your analysis findings

In short, the research process is simply about asking and answering questions in a systematic fashion . This probably sounds pretty obvious, but people often think they’ve done “research”, when in fact what they have done is:

- Started with a vague, poorly articulated question

- Not taken the time to see what research has already been done regarding the question

- Collected data and opinions that support their gut and undertaken a flimsy analysis

- Drawn a shaky conclusion, based on that analysis

If you want to see the perfect example of this in action, look out for the next Facebook post where someone claims they’ve done “research”… All too often, people consider reading a few blog posts to constitute research. Its no surprise then that what they end up with is an opinion piece, not research. Okay, okay – I’ll climb off my soapbox now.

The key takeaway here is that a dissertation (or thesis) is a formal piece of research, reflecting the research process. It’s not an opinion piece , nor a place to push your agenda or try to convince someone of your position. Writing a good dissertation involves asking a question and taking a systematic, rigorous approach to answering it.

If you understand this and are comfortable leaving your opinions or preconceived ideas at the door, you’re already off to a good start!

Step 2: Find a unique, valuable research topic

As we saw, the first step of the research process is to ask a specific, well-articulated question. In other words, you need to find a research topic that asks a specific question or set of questions (these are called research questions ). Sounds easy enough, right? All you’ve got to do is identify a question or two and you’ve got a winning research topic. Well, not quite…

A good dissertation or thesis topic has a few important attributes. Specifically, a solid research topic should be:

Let’s take a closer look at these:

Attribute #1: Clear

Your research topic needs to be crystal clear about what you’re planning to research, what you want to know, and within what context. There shouldn’t be any ambiguity or vagueness about what you’ll research.

Here’s an example of a clearly articulated research topic:

An analysis of consumer-based factors influencing organisational trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms.

As you can see in the example, its crystal clear what will be analysed (factors impacting organisational trust), amongst who (consumers) and in what context (British low-cost equity brokerage firms, based online).

Need a helping hand?

Attribute #2: Unique

Your research should be asking a question(s) that hasn’t been asked before, or that hasn’t been asked in a specific context (for example, in a specific country or industry).

For example, sticking organisational trust topic above, it’s quite likely that organisational trust factors in the UK have been investigated before, but the context (online low-cost equity brokerages) could make this research unique. Therefore, the context makes this research original.

One caveat when using context as the basis for originality – you need to have a good reason to suspect that your findings in this context might be different from the existing research – otherwise, there’s no reason to warrant researching it.

Attribute #3: Important

Simply asking a unique or original question is not enough – the question needs to create value. In other words, successfully answering your research questions should provide some value to the field of research or the industry. You can’t research something just to satisfy your curiosity. It needs to make some form of contribution either to research or industry.

For example, researching the factors influencing consumer trust would create value by enabling businesses to tailor their operations and marketing to leverage factors that promote trust. In other words, it would have a clear benefit to industry.

So, how do you go about finding a unique and valuable research topic? We explain that in detail in this video post – How To Find A Research Topic . Yeah, we’ve got you covered 😊

Step 3: Write a convincing research proposal

Once you’ve pinned down a high-quality research topic, the next step is to convince your university to let you research it. No matter how awesome you think your topic is, it still needs to get the rubber stamp before you can move forward with your research. The research proposal is the tool you’ll use for this job.

So, what’s in a research proposal?

The main “job” of a research proposal is to convince your university, advisor or committee that your research topic is worthy of approval. But convince them of what? Well, this varies from university to university, but generally, they want to see that:

- You have a clearly articulated, unique and important topic (this might sound familiar…)

- You’ve done some initial reading of the existing literature relevant to your topic (i.e. a literature review)

- You have a provisional plan in terms of how you will collect data and analyse it (i.e. a methodology)

At the proposal stage, it’s (generally) not expected that you’ve extensively reviewed the existing literature , but you will need to show that you’ve done enough reading to identify a clear gap for original (unique) research. Similarly, they generally don’t expect that you have a rock-solid research methodology mapped out, but you should have an idea of whether you’ll be undertaking qualitative or quantitative analysis , and how you’ll collect your data (we’ll discuss this in more detail later).

Long story short – don’t stress about having every detail of your research meticulously thought out at the proposal stage – this will develop as you progress through your research. However, you do need to show that you’ve “done your homework” and that your research is worthy of approval .

So, how do you go about crafting a high-quality, convincing proposal? We cover that in detail in this video post – How To Write A Top-Class Research Proposal . We’ve also got a video walkthrough of two proposal examples here .

Step 4: Craft a strong introduction chapter

Once your proposal’s been approved, its time to get writing your actual dissertation or thesis! The good news is that if you put the time into crafting a high-quality proposal, you’ve already got a head start on your first three chapters – introduction, literature review and methodology – as you can use your proposal as the basis for these.

Handy sidenote – our free dissertation & thesis template is a great way to speed up your dissertation writing journey.

What’s the introduction chapter all about?

The purpose of the introduction chapter is to set the scene for your research (dare I say, to introduce it…) so that the reader understands what you’ll be researching and why it’s important. In other words, it covers the same ground as the research proposal in that it justifies your research topic.

What goes into the introduction chapter?

This can vary slightly between universities and degrees, but generally, the introduction chapter will include the following:

- A brief background to the study, explaining the overall area of research

- A problem statement , explaining what the problem is with the current state of research (in other words, where the knowledge gap exists)

- Your research questions – in other words, the specific questions your study will seek to answer (based on the knowledge gap)

- The significance of your study – in other words, why it’s important and how its findings will be useful in the world

As you can see, this all about explaining the “what” and the “why” of your research (as opposed to the “how”). So, your introduction chapter is basically the salesman of your study, “selling” your research to the first-time reader and (hopefully) getting them interested to read more.

How do I write the introduction chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this post .

Step 5: Undertake an in-depth literature review

As I mentioned earlier, you’ll need to do some initial review of the literature in Steps 2 and 3 to find your research gap and craft a convincing research proposal – but that’s just scratching the surface. Once you reach the literature review stage of your dissertation or thesis, you need to dig a lot deeper into the existing research and write up a comprehensive literature review chapter.

What’s the literature review all about?

There are two main stages in the literature review process:

Literature Review Step 1: Reading up

The first stage is for you to deep dive into the existing literature (journal articles, textbook chapters, industry reports, etc) to gain an in-depth understanding of the current state of research regarding your topic. While you don’t need to read every single article, you do need to ensure that you cover all literature that is related to your core research questions, and create a comprehensive catalogue of that literature , which you’ll use in the next step.

Reading and digesting all the relevant literature is a time consuming and intellectually demanding process. Many students underestimate just how much work goes into this step, so make sure that you allocate a good amount of time for this when planning out your research. Thankfully, there are ways to fast track the process – be sure to check out this article covering how to read journal articles quickly .

Literature Review Step 2: Writing up

Once you’ve worked through the literature and digested it all, you’ll need to write up your literature review chapter. Many students make the mistake of thinking that the literature review chapter is simply a summary of what other researchers have said. While this is partly true, a literature review is much more than just a summary. To pull off a good literature review chapter, you’ll need to achieve at least 3 things:

- You need to synthesise the existing research , not just summarise it. In other words, you need to show how different pieces of theory fit together, what’s agreed on by researchers, what’s not.

- You need to highlight a research gap that your research is going to fill. In other words, you’ve got to outline the problem so that your research topic can provide a solution.

- You need to use the existing research to inform your methodology and approach to your own research design. For example, you might use questions or Likert scales from previous studies in your your own survey design .

As you can see, a good literature review is more than just a summary of the published research. It’s the foundation on which your own research is built, so it deserves a lot of love and attention. Take the time to craft a comprehensive literature review with a suitable structure .

But, how do I actually write the literature review chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this video post .

Step 6: Carry out your own research

Once you’ve completed your literature review and have a sound understanding of the existing research, its time to develop your own research (finally!). You’ll design this research specifically so that you can find the answers to your unique research question.

There are two steps here – designing your research strategy and executing on it:

1 – Design your research strategy

The first step is to design your research strategy and craft a methodology chapter . I won’t get into the technicalities of the methodology chapter here, but in simple terms, this chapter is about explaining the “how” of your research. If you recall, the introduction and literature review chapters discussed the “what” and the “why”, so it makes sense that the next point to cover is the “how” –that’s what the methodology chapter is all about.

In this section, you’ll need to make firm decisions about your research design. This includes things like:

- Your research philosophy (e.g. positivism or interpretivism )

- Your overall methodology (e.g. qualitative , quantitative or mixed methods)

- Your data collection strategy (e.g. interviews , focus groups, surveys)

- Your data analysis strategy (e.g. content analysis , correlation analysis, regression)

If these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these in plain language in other posts. It’s not essential that you understand the intricacies of research design (yet!). The key takeaway here is that you’ll need to make decisions about how you’ll design your own research, and you’ll need to describe (and justify) your decisions in your methodology chapter.

2 – Execute: Collect and analyse your data

Once you’ve worked out your research design, you’ll put it into action and start collecting your data. This might mean undertaking interviews, hosting an online survey or any other data collection method. Data collection can take quite a bit of time (especially if you host in-person interviews), so be sure to factor sufficient time into your project plan for this. Oftentimes, things don’t go 100% to plan (for example, you don’t get as many survey responses as you hoped for), so bake a little extra time into your budget here.

Once you’ve collected your data, you’ll need to do some data preparation before you can sink your teeth into the analysis. For example:

- If you carry out interviews or focus groups, you’ll need to transcribe your audio data to text (i.e. a Word document).

- If you collect quantitative survey data, you’ll need to clean up your data and get it into the right format for whichever analysis software you use (for example, SPSS, R or STATA).

Once you’ve completed your data prep, you’ll undertake your analysis, using the techniques that you described in your methodology. Depending on what you find in your analysis, you might also do some additional forms of analysis that you hadn’t planned for. For example, you might see something in the data that raises new questions or that requires clarification with further analysis.

The type(s) of analysis that you’ll use depend entirely on the nature of your research and your research questions. For example:

- If your research if exploratory in nature, you’ll often use qualitative analysis techniques .

- If your research is confirmatory in nature, you’ll often use quantitative analysis techniques

- If your research involves a mix of both, you might use a mixed methods approach

Again, if these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these concepts and techniques in other posts. The key takeaway is simply that there’s no “one size fits all” for research design and methodology – it all depends on your topic, your research questions and your data. So, don’t be surprised if your study colleagues take a completely different approach to yours.

Step 7: Present your findings

Once you’ve completed your analysis, it’s time to present your findings (finally!). In a dissertation or thesis, you’ll typically present your findings in two chapters – the results chapter and the discussion chapter .

What’s the difference between the results chapter and the discussion chapter?

While these two chapters are similar, the results chapter generally just presents the processed data neatly and clearly without interpretation, while the discussion chapter explains the story the data are telling – in other words, it provides your interpretation of the results.

For example, if you were researching the factors that influence consumer trust, you might have used a quantitative approach to identify the relationship between potential factors (e.g. perceived integrity and competence of the organisation) and consumer trust. In this case:

- Your results chapter would just present the results of the statistical tests. For example, correlation results or differences between groups. In other words, the processed numbers.

- Your discussion chapter would explain what the numbers mean in relation to your research question(s). For example, Factor 1 has a weak relationship with consumer trust, while Factor 2 has a strong relationship.

Depending on the university and degree, these two chapters (results and discussion) are sometimes merged into one , so be sure to check with your institution what their preference is. Regardless of the chapter structure, this section is about presenting the findings of your research in a clear, easy to understand fashion.

Importantly, your discussion here needs to link back to your research questions (which you outlined in the introduction or literature review chapter). In other words, it needs to answer the key questions you asked (or at least attempt to answer them).

For example, if we look at the sample research topic:

In this case, the discussion section would clearly outline which factors seem to have a noteworthy influence on organisational trust. By doing so, they are answering the overarching question and fulfilling the purpose of the research .

For more information about the results chapter , check out this post for qualitative studies and this post for quantitative studies .

Step 8: The Final Step Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Last but not least, you’ll need to wrap up your research with the conclusion chapter . In this chapter, you’ll bring your research full circle by highlighting the key findings of your study and explaining what the implications of these findings are.

What exactly are key findings? The key findings are those findings which directly relate to your original research questions and overall research objectives (which you discussed in your introduction chapter). The implications, on the other hand, explain what your findings mean for industry, or for research in your area.

Sticking with the consumer trust topic example, the conclusion might look something like this:

Key findings

This study set out to identify which factors influence consumer-based trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms. The results suggest that the following factors have a large impact on consumer trust:

While the following factors have a very limited impact on consumer trust:

Notably, within the 25-30 age groups, Factors E had a noticeably larger impact, which may be explained by…

Implications

The findings having noteworthy implications for British low-cost online equity brokers. Specifically:

The large impact of Factors X and Y implies that brokers need to consider….

The limited impact of Factor E implies that brokers need to…

As you can see, the conclusion chapter is basically explaining the “what” (what your study found) and the “so what?” (what the findings mean for the industry or research). This brings the study full circle and closes off the document.

Let’s recap – how to write a dissertation or thesis

You’re still with me? Impressive! I know that this post was a long one, but hopefully you’ve learnt a thing or two about how to write a dissertation or thesis, and are now better equipped to start your own research.

To recap, the 8 steps to writing a quality dissertation (or thesis) are as follows:

- Understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is – a research project that follows the research process.

- Find a unique (original) and important research topic

- Craft a convincing dissertation or thesis research proposal

- Write a clear, compelling introduction chapter

- Undertake a thorough review of the existing research and write up a literature review

- Undertake your own research

- Present and interpret your findings

Once you’ve wrapped up the core chapters, all that’s typically left is the abstract , reference list and appendices. As always, be sure to check with your university if they have any additional requirements in terms of structure or content.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

20 Comments

thankfull >>>this is very useful

Thank you, it was really helpful

unquestionably, this amazing simplified way of teaching. Really , I couldn’t find in the literature words that fully explicit my great thanks to you. However, I could only say thanks a-lot.

Great to hear that – thanks for the feedback. Good luck writing your dissertation/thesis.

This is the most comprehensive explanation of how to write a dissertation. Many thanks for sharing it free of charge.

Very rich presentation. Thank you

Thanks Derek Jansen|GRADCOACH, I find it very useful guide to arrange my activities and proceed to research!

Thank you so much for such a marvelous teaching .I am so convinced that am going to write a comprehensive and a distinct masters dissertation

It is an amazing comprehensive explanation

This was straightforward. Thank you!

I can say that your explanations are simple and enlightening – understanding what you have done here is easy for me. Could you write more about the different types of research methods specific to the three methodologies: quan, qual and MM. I look forward to interacting with this website more in the future.

Thanks for the feedback and suggestions 🙂

Hello, your write ups is quite educative. However, l have challenges in going about my research questions which is below; *Building the enablers of organisational growth through effective governance and purposeful leadership.*

Very educating.

Just listening to the name of the dissertation makes the student nervous. As writing a top-quality dissertation is a difficult task as it is a lengthy topic, requires a lot of research and understanding and is usually around 10,000 to 15000 words. Sometimes due to studies, unbalanced workload or lack of research and writing skill students look for dissertation submission from professional writers.

Thank you 💕😊 very much. I was confused but your comprehensive explanation has cleared my doubts of ever presenting a good thesis. Thank you.

thank you so much, that was so useful

Hi. Where is the excel spread sheet ark?

could you please help me look at your thesis paper to enable me to do the portion that has to do with the specification

my topic is “the impact of domestic revenue mobilization.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Franklin University |

- Help & Support |

- Locations & Maps |

- | Research Guides

To access Safari eBooks,

- Select not listed in the Select Your Institution drop down menu.

- Enter your Franklin email address and click Go

- click "Already a user? Click here" link

- Enter your Franklin email and the password you used to create your Safari account.

Continue Close

Ed.D.: Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership

- Education Research

- Scholarly Research

- GoogleScholar

- Doctoral Writing Guide This link opens in a new window

- Annotated Bibliography Resources

- Literature Review This link opens in a new window

- APA Style Guide This link opens in a new window

- Research Methods

Dissertation Databases

Dip resources, citi training.

- Dissertation

- RefWorks This link opens in a new window

- Doctoral FAQs

Franklin Dissertation Resources

- Franklin University Doctoral Resources Doctoral Studies Resource documents, including the dissertation handbook and guide to submitting your dissertation are available on the Office of Academic Scholarship page.

- Franklin University Student Dissertations View former Franklin student's dissertations in the OhioLINK ETD Center.

- Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center (OhioLINK) This link opens in a new window Online theses and dissertations from Ohio graduate students.

- Open Access Theses and Dissertations This link opens in a new window Information about and links to freely-available full-text to almost almost 3.5 million graduate theses and dissertations from over 1,100 colleges, universities, and research institutions.

- Open Dissertations This link opens in a new window Open access database providing both historic and contemporary dissertations and theses. Includes content of the American Doctoral Dissertations database, which provides more than 153,000 theses and dissertations from 1902 to the present, as well as additional dissertation information provided by colleges and universities from around the world. Includes links to full-text from free platforms where available.

- ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global This link opens in a new window Doctoral dissertations and theses from around the world, spanning from 1743 to the present day and offering full text for graduate works added since 1997, along with selected full text for works written prior to 1997. It contains a significant amount of new international dissertations and theses both in citations and in full text.

- WorldCat Dissertations and Theses This link opens in a new window Catalog of dissertations, theses and published material based on theses, worldwide.

- CPED Dissertation in Practice Find sample dissertations in practice from institutions that are members of the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED)

Doctoral students are required to prepare a research proposal for their dissertation study. All doctoral projects that involve human subjects must be reviewed and approved by Franklin University's Institutional Review Board (IRB) to ensure the rights and welfare of human participants are protected. The research proposal will be included in the IRB application.

Anyone who conducts human subjects research at Franklin University must complete training before any research activities commence and before submitting a research proposal to the IRB for review. The Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) provides an online training course to satisfy this requirement and must be completed by all faculty, staff, and students involved in human subjects research. CITI educational courses help researchers to understand their obligations to protect the rights and welfare of human subjects in research.

Please take the following steps to complete your CITI training:

- Log on to the CITI homepage: www.citiprogram.org and click on the Register link. You will register with Franklin University in this seven-step process. Please use your Franklin University email address, which will link your CITI record to Cayuse IRB.

- Franklin learners must complete the Social and Behavioral Research (SBE) course. Additional elective courses are available but not required to conduct human subjects research at the University. The SBE course will take a few hours to complete, but you are not required to complete all modules in one sitting.

Completing the CITI course will keep your training current for three years, after which time you will be required to complete a refresher course that updates your training for another three years. You will receive an email reminder from CITI when it is time to refresh your training. If your training expires during any human subjects research project, you must cease all research activities until your training has been updated.

- Institutional Review Board (IRB) Office For questions or issues with CITI Training, please contact the Franklin University IRB Office. Email: [email protected] Phone: 614.947.6037

- << Previous: Research Methods

- Next: RefWorks >>

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 9:37 AM

- URL: https://guides.franklin.edu/EdD

EdDPrograms.org

What is an Ed.D. Dissertation? Complete Guide & Support Resources

Wondering how to tackle the biggest doctoral challenge of all? Use our guide to the Ed.D. dissertation to get started! Learn about the purpose of a Doctor of Education dissertation and typical topics for education students. Read through step-by-step descriptions of the dissertation process and the 5-chapter format. Get answers to Ed.D. dissertation FAQs . Or skip to the chase and find real-world examples of Doctor of Education dissertations and websites & resources for Ed.D. dissertation research.

What is an Ed.D. Dissertation?

Definition of an ed.d. dissertation.

An Ed.D. dissertation is a 5-chapter scholarly document that brings together years of original research to address a problem of practice in education. To complete a dissertation, you will need to go through a number of scholarly steps , including a final defense to justify your findings.

Purpose of an Ed.D. Dissertation

In a Doctor of Education dissertation, you will be challenged to apply high-level research & creative problem-solving to real-world educational challenges. You may be asked to:

- Take a critical look at current educational & administrative practices

- Address urgent issues in the modern education system

- Propose original & practical solutions for improvements

- Expand the knowledge base for educational practitioners

Topics of Ed.D. Dissertations

An Ed.D. dissertation is “customizable.” You’re allowed to chose a topic that relates to your choice of specialty (e.g. elementary education), field of interest (e.g. curriculum development), and environment (e.g. urban schools).

Think about current problems of practice that need to be addressed in your field. You’ll notice that Ed.D. dissertation topics often address one of the following:

- Academic performance

- Teaching methods

- Access to resources

- Social challenges

- Legislative impacts

- System effectiveness

Wondering how others have done it? Browse through Examples of Ed.D. Dissertations and read the titles & abstracts. You’ll see how current educators are addressing their own problems of practice.

Ed.D. Dissertation Process

1. propose a dissertation topic.

Near the beginning of a Doctor of Education program, you’ll be expected to identify a dissertation topic that will require substantial research. This topic should revolve around a unique issue in education.

Universities will often ask you to provide an idea for your topic when you’re applying to the doctoral program. You don’t necessarily need to stick to this idea, but you should be prepared to explain why it interests you. If you need inspiration, see our section on Examples of Ed.D. Dissertations .

You’ll be expected to solidify your dissertation topic in the first few semesters. Talking to faculty and fellow Ed.D. students can help in this process. Better yet, your educational peers will often be able to provide unique perspectives on the topic (e.g. cultural differences in teaching methods).

2. Meet Your Dissertation Chair & Committee

You won’t be going through the Ed.D. dissertation process alone! Universities will help you to select a number of experienced mentors. These include:

- Dissertation Chair/Faculty Advisor: The Chair of the Dissertation Committee acts as your primary advisor. You’ll often see them referred to as the Supervising Professor, Faculty Advisor, or the like. You’ll rely on this “Obi Wan” for their knowledge of the field, research advice & guidance, editorial input on drafts, and more. They can also assist with shaping & refining your dissertation topic.

- Dissertation Committee: The Dissertation Committee is made up of ~3 faculty members, instructors and/or adjuncts with advanced expertise in your field of study. The Committee will offer advice, provide feedback on your research progress, and review your work & progress reports. When you defend your proposal and give your final defense , you’ll be addressing the Dissertation Committee.

3. Study for Ed.D. Courses

Doctor of Education coursework is designed to help you: a) learn how to conduct original research; and b) give you a broader perspective on your field of interest. If you take a look at the curriculum in any Ed.D. program, you’ll see that students have to complete credits in:

- Practical Research Methods (e.g. Quantitative Design & Analysis for Educational Leaders)

- Real-World Educational Issues (e.g. Educational Policy, Law & Practice)

When you’re evaluating possible Ed.D. programs, pay attention to the coursework in real-world educational issues. You’ll want to pick an education doctorate with courses that complement your dissertation topic.

4. Complete a Literature Review

A literature review is an evaluation of existing materials & research work that relate to your dissertation topic. It’s a written synthesis that:

- Grounds your project within the field

- Explains how your work relates to previous research & theoretical frameworks

- Helps to identify gaps in the existing research

Have a look at Literature Review Guides if you’d like to know more about the process. Our section on Resources for Ed.D. Dissertation Research also has useful links to journals & databases.

5. Craft a Dissertation Proposal

During the first two years of your Doctor of Education, you’ll use the knowledge you’ve learned from your coursework & discussions to write the opening chapters of your dissertation, including an:

- Introduction that defines your chosen topic

- Literature Review of existing research in the field

- Proposed Research Methodology for finding the answer to your problem

When you’re putting together these elements, think about the practicals. Is the topic too big to address in one dissertation? How much time will your research take and how will you conduct it? Will your dissertation be relevant to your current job? If in doubt, ask your faculty advisor.

6. Defend Your Dissertation Proposal

About midway through the Ed.D. program, you will need to present your proposal to your Dissertation Committee. They will review your work and offer feedback. For example, the Committee will want to see that:

- Your research topic is significant.

- Your research methodology & timeline make sense.

- Relevant works are included in the literature review.

After the Committee approves your proposal, you can get stuck into conducting original research and writing up your findings. These two important tasks will take up the final years of your doctorate.

7. Conduct Original Research into Your Topic

As a Doctor of Education student, you will be expected to conduct your own research. Ed.D. students often use a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods (quantitative/qualitative) approach in this process.

- Quantitative Research: Collection & analysis of numerical data to identify characteristics, discover correlations, and/or test hypotheses.

- Qualitative Research: Collection & analysis of non-numerical data to understand & explain phenomena (e.g. questionnaires, in-depth interviews, focus groups, video artifacts, etc.).

Your Ed.D. coursework will ground you in research methods & tools, so you’ll be prepared to design your own project and seek IRB approval for any work involving human subjects.

Note: Occasionally, universities can get creative. For example, the Ed.D. program at San Jose State University asks students to produce a documentary film instead of conducting traditional research.

8. Write the Rest of Your Dissertation

Once you have written up the first few chapters of your dissertation (Intro, Literature Review & Proposed Methodology) and completed your research work, you’ll be able to complete the final chapters of your dissertation.

- Chapter 4 will detail your research findings.

- Chapter 5 is a conclusion that summarizes solutions to your problem of practice/topic.

This is where you and your faculty advisor will often have a lot of interaction! For example, you may need to rework the first few chapters of your dissertation after you’ve drafted the final chapters. Faculty advisors are extremely busy people, so be sure to budget in ample time for revisions and final edits.

9. Defend Your Dissertation

The final defense/candidacy exam is a formal presentation of your work to the Dissertation Committee. In many cases, the defense is an oral presentation with visual aides. You’ll be able to explain your research findings, go through your conclusions, and highlight new ideas & solutions.

At any time, the Committee can challenge you with questions, so you should be prepared to defend your conclusions. But this process is not as frightening as it sounds!

- If you’ve been in close contact with the Committee throughout the dissertation, they will be aware of your work.

- Your faculty advisor will help you decide when you’re ready for the final defense.

- You can also attend the defenses of other Ed.D. students to learn what questions may be asked.

Be aware that the Committee has the option to ask for changes before they approve your dissertation. After you have incorporated any notes from the Committee and addressed their concerns, you will finalize the draft, submit your dissertation for a formal review, and graduate.

Ed.D. Dissertation Format: 5 Chapters

Chapter 1: introduction.

Your Doctor of Education dissertation will begin with an introduction. In it, you’ll be expected to:

- Provide an overview of your educational landscape

- Explain important definitions & key concepts

- Define a real-world topic/problem of practice

- Outline the need for new studies on this topic

Chapter 2: Literature Review

The literature review is a summary of existing research in the field. However, it is not an annotated bibliography. Instead, it’s a critical analysis of current research (e.g. trends, themes, debates & current practices). While you’re evaluating the literature, you’re also looking for the gaps where you can conduct original research.

Sources for a literature review can include books, articles, reports, websites, dissertations, and more. Our section on Resources for Ed.D. Dissertation Research has plenty of places to start.

Chapter 3: Research Methodology

In the research methodology, you’ll be expected to explain:

- The purpose of your research

- What tools & methods you plan to use to research your topic/problem of practice

- The design of the study

- Your timeline for gathering quantitative & qualitative data

- How you plan to analyze that data

- Any limitations you foresee

Chapter 4: Results & Analysis

Chapter 4 is the place where you can share the results of your original research and present key findings from the data. In your analysis, you may also be highlighting new patterns, relationships, and themes that other scholars have failed to discover. Have a look at real-life Examples of Ed.D. Dissertations to see how this section is structured.

Chapter 5: Discussions & Conclusions

The final chapter of your Ed.D. dissertation brings all of your work together in a detailed summary. You’ll be expected to:

- Reiterate the objectives of your dissertation

- Explain the significance of your research findings

- Outline the implications of your ideas on existing practices

- Propose solutions for a problem of practice

- Make suggestions & recommendations for future improvements

Ed.D. Dissertation FAQs

What’s the difference between a dissertation and a thesis.

- Dissertation: A dissertation is a 5-chapter written work that must be completed in order to earn a doctoral degree (e.g. Ph.D., Ed.D., etc.). It’s often focused on original research.

- Thesis: A thesis is a written work that must be completed in order to earn a master’s degree. It’s typically shorter than a dissertation and based on existing research.

How Long is a Ed.D. Dissertation?

It depends. Most Ed.D. dissertations end up being between 80-200 pages. The length will depend on a number of factors, including the depth of your literature review, the way you collect & present your research data, and any appendices you might need to include.

How Long Does it Take to Finish an Ed.D. Dissertation?

It depends. If you’re in an accelerated program , you may be able to finish your dissertation in 2-3 years. If you’re in a part-time program and need to conduct a lot of complex research work, your timeline will be much longer.

What’s a Strong Ed.D. Dissertation Topic?

Experts always say that Doctor of Education students should be passionate about their dissertation topic and eager to explore uncharted territory. When you’re crafting your Ed.D. dissertation topic , find one that will be:

- Significant

See the section on Examples of Ed.D. Dissertations for inspiration.

Do I Have to Complete a Traditional Dissertation for an Ed.D.?

No. If you’re struggling with the idea of a traditional dissertation, check out this guide to Online Ed.D. Programs with No Dissertation . Some Schools of Education give Ed.D. students the opportunity to complete a Capstone Project or Dissertation in Practice (DiP) instead of a 5-chapter written work.

These alternatives aren’t easy! You’ll still be challenged at the same level as you would be for a dissertation. However, Capstone Projects & DiPs often involve more group work and an emphasis on applied theory & research.

What’s the Difference Between a Ph.D. Dissertation and Ed.D. Dissertation?

Have a look at our Ed.D. vs. Ph.D. Guide to get a sense of the differences between the two degrees. In a nutshell:

- Ed.D. dissertations tend to focus on addressing current & real-world topics/problems of practice in the workplace.

- Ph.D. dissertations usually put more emphasis on creating new theories & concepts and even completely rethinking educational practices.

How Can I Learn More About Ed.D. Dissertations?

Start with the section on Examples of Ed.D. Dissertations . You can browse through titles, abstracts, and even complete dissertations from a large number of universities.

If you have a few Doctor of Education programs on your shortlist, we also recommend that you skim through the program’s Dissertation Handbook . It can usually be found on the School of Education’s website. You’ll be able to see how the School likes to structure the dissertation process from start to finish.

Ed.D. Dissertation Support

University & campus resources, dissertation chair & committee.

The first port of call for any questions about the Ed.D. dissertation is your Dissertation Chair. If you get stuck with a terrible faculty advisor, talk to members of the Dissertation Committee. They are there to support your journey.

University Library

An Ed.D. dissertation is a massive research project. So before you choose a Doctor of Education program, ask the School of Education about its libraries & library resources (e.g. free online access to subscription-based journals).

Writing Center

Many universities have a Writing Center. If you’re struggling with any elements of your dissertation (e.g. editing), you can ask the staff about:

- Individual tutoring

- Editorial assistance

- Outside resources

Mental Health Support

It’s well-known that doctoral students often face a lot of stress & isolation during their studies. Ask your faculty advisor about mental health services at the university. Staff in the School of Education and the Graduate School will also have information about on-campus counselors, free or discounted therapy sessions, and more.

Independent Dissertation Services

Dissertation editing services: potentially helpful.

There are scores of independent providers who offer dissertation editing services. But they can be expensive. And many of these editors have zero expertise in educational fields.

If you need help with editing & proofreading, proceed with caution:

- Start by asking your Dissertation Chair about what’s permitted for third party involvement (e.g. you may need to note any editor’s contribution in your dissertation acknowledgments) and whether they have any suggestions.

- The Graduate School is another useful resource. For example, Cornell’s Graduate School maintains a list of Editing, Typing, and Proofreading Services for graduate students.

Dissertation Coaches: Not Worth It

Dissertation coaches are defined as people who offer academic & mental support, guidance, and editorial input.

- That means the person who should be your coach is your Dissertation Chair/Faculty Advisor. Remember that faculty members on the Dissertation Committee can also provide assistance.

- If you’re looking for extra support, you might consider consulting a mentor in your line of work and collaborating with fellow Ed.D. students.

But hiring an independent Ed.D. dissertation coach is going to be an absolute waste of money.

Dissertation Writing Services: Just Don’t!

Universities take the dissertation process very seriously . An Ed.D. dissertation is supposed to be the culmination of years of original thought and research. You’re going to be responsible for the final product. You’re going to be defending your written work in front of a phalanx of experienced faculty members. You’re going to be putting this credential on your résumé for everyone to see.

If you cheat the process by having someone else write up your work, you will get caught.

Ed.D. Dissertation Resources

Examples of ed.d. dissertations, dissertation databases.

- Open Access Theses and Dissertations

- ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- EBSCO Open Dissertations

Ed.D. Dissertations

- USF Scholarship Repository: Ed.D. Dissertations

- George Fox University: Doctor of Education

- UW Tacoma: Ed.D. Dissertations in Practice

- Liberty University: School of Education Doctoral Dissertations

- University of Mary Hardin-Baylor: Dissertation Collection

Ed.D. Dissertation Abstracts

- Michigan State University: Ed.D. Dissertation Abstracts

Ed.D. Dissertation Guides & Tools

General ed.d. guides.

- SNHU: Educational Leadership Ed.D./Ph.D. Guide

Dissertation Style Manuals

- Chicago Manual of Style

Style manuals are designed to ensure that every Ed.D. student follows the same set of writing guidelines for their dissertation (e.g. grammatical rules, footnote & quotation formats, abbreviation conventions, etc.). Check with the School of Education to learn which style manual they use.

Examples of Ed.D. Dissertation Templates

- Purdue University: Dissertation Template

- Walden University: Ed.D. Dissertation Template

Each School of Education has a standard dissertation template. We’ve highlighted a couple of examples so you can see how they’re formatted, but you will need to acquire the template from your own university.

Literature Review Guides

- UNC Chapel Hill: Writing Guide for Literature Reviews

- University of Alabama: How to Conduct a Literature Review

Resources for Ed.D. Dissertation Research

Journal articles.

- EBSCO Education Research Databases

- Education Resources Information Center (ERIC)

- Emerald Education eJournal Collection

- Gale OneFile: Educator’s Reference Complete

- Google Scholar

- NCES Bibliography Search Tool

- ProQuest Education Database

- SAGE Journals: Education

Useful Websites

- Harvard Gutman Library: Websites for Educators

- EduRef: Lesson Plans

Educational Data & Statistics

- Digest of Education Statistics

- Education Policy Data Center (EPDC)

- ICPSR Data Archive

- National Assessment of Educational Progress

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES)

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started

Published on 26 March 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 5 May 2022.

A dissertation is a large research project undertaken at the end of a degree. It involves in-depth consideration of a problem or question chosen by the student. It is usually the largest (and final) piece of written work produced during a degree.

The length and structure of a dissertation vary widely depending on the level and field of study. However, there are some key questions that can help you understand the requirements and get started on your dissertation project.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

When and why do you have to write a dissertation, who will supervise your dissertation, what type of research will you do, how should your dissertation be structured, what formatting and referencing rules do you have to follow, frequently asked questions about dissertations.

A dissertation, sometimes called a thesis, comes at the end of an undergraduate or postgraduate degree. It is a larger project than the other essays you’ve written, requiring a higher word count and a greater depth of research.

You’ll generally work on your dissertation during the final year of your degree, over a longer period than you would take for a standard essay . For example, the dissertation might be your main focus for the last six months of your degree.

Why is the dissertation important?

The dissertation is a test of your capacity for independent research. You are given a lot of autonomy in writing your dissertation: you come up with your own ideas, conduct your own research, and write and structure the text by yourself.

This means that it is an important preparation for your future, whether you continue in academia or not: it teaches you to manage your own time, generate original ideas, and work independently.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

During the planning and writing of your dissertation, you’ll work with a supervisor from your department. The supervisor’s job is to give you feedback and advice throughout the process.

The dissertation supervisor is often assigned by the department, but you might be allowed to indicate preferences or approach potential supervisors. If so, try to pick someone who is familiar with your chosen topic, whom you get along with on a personal level, and whose feedback you’ve found useful in the past.

How will your supervisor help you?

Your supervisor is there to guide you through the dissertation project, but you’re still working independently. They can give feedback on your ideas, but not come up with ideas for you.

You may need to take the initiative to request an initial meeting with your supervisor. Then you can plan out your future meetings and set reasonable deadlines for things like completion of data collection, a structure outline, a first chapter, a first draft, and so on.

Make sure to prepare in advance for your meetings. Formulate your ideas as fully as you can, and determine where exactly you’re having difficulties so you can ask your supervisor for specific advice.

Your approach to your dissertation will vary depending on your field of study. The first thing to consider is whether you will do empirical research , which involves collecting original data, or non-empirical research , which involves analysing sources.

Empirical dissertations (sciences)

An empirical dissertation focuses on collecting and analysing original data. You’ll usually write this type of dissertation if you are studying a subject in the sciences or social sciences.

- What are airline workers’ attitudes towards the challenges posed for their industry by climate change?

- How effective is cognitive behavioural therapy in treating depression in young adults?

- What are the short-term health effects of switching from smoking cigarettes to e-cigarettes?

There are many different empirical research methods you can use to answer these questions – for example, experiments , observations, surveys , and interviews.

When doing empirical research, you need to consider things like the variables you will investigate, the reliability and validity of your measurements, and your sampling method . The aim is to produce robust, reproducible scientific knowledge.

Non-empirical dissertations (arts and humanities)

A non-empirical dissertation works with existing research or other texts, presenting original analysis, critique and argumentation, but no original data. This approach is typical of arts and humanities subjects.

- What attitudes did commentators in the British press take towards the French Revolution in 1789–1792?

- How do the themes of gender and inheritance intersect in Shakespeare’s Macbeth ?

- How did Plato’s Republic and Thomas More’s Utopia influence nineteenth century utopian socialist thought?

The first steps in this type of dissertation are to decide on your topic and begin collecting your primary and secondary sources .

Primary sources are the direct objects of your research. They give you first-hand evidence about your subject. Examples of primary sources include novels, artworks and historical documents.

Secondary sources provide information that informs your analysis. They describe, interpret, or evaluate information from primary sources. For example, you might consider previous analyses of the novel or author you are working on, or theoretical texts that you plan to apply to your primary sources.

Dissertations are divided into chapters and sections. Empirical dissertations usually follow a standard structure, while non-empirical dissertations are more flexible.

Structure of an empirical dissertation

Empirical dissertations generally include these chapters:

- Introduction : An explanation of your topic and the research question(s) you want to answer.

- Literature review : A survey and evaluation of previous research on your topic.

- Methodology : An explanation of how you collected and analysed your data.

- Results : A brief description of what you found.

- Discussion : Interpretation of what these results reveal.

- Conclusion : Answers to your research question(s) and summary of what your findings contribute to knowledge in your field.

Sometimes the order or naming of chapters might be slightly different, but all of the above information must be included in order to produce thorough, valid scientific research.

Other dissertation structures

If your dissertation doesn’t involve data collection, your structure is more flexible. You can think of it like an extended essay – the text should be logically organised in a way that serves your argument:

- Introduction: An explanation of your topic and the question(s) you want to answer.

- Main body: The development of your analysis, usually divided into 2–4 chapters.

- Conclusion: Answers to your research question(s) and summary of what your analysis contributes to knowledge in your field.

The chapters of the main body can be organised around different themes, time periods, or texts. Below you can see some example structures for dissertations in different subjects.

- Political philosophy

This example, on the topic of the British press’s coverage of the French Revolution, shows how you might structure each chapter around a specific theme.

This example, on the topic of Plato’s and More’s influences on utopian socialist thought, shows a different approach to dividing the chapters by theme.

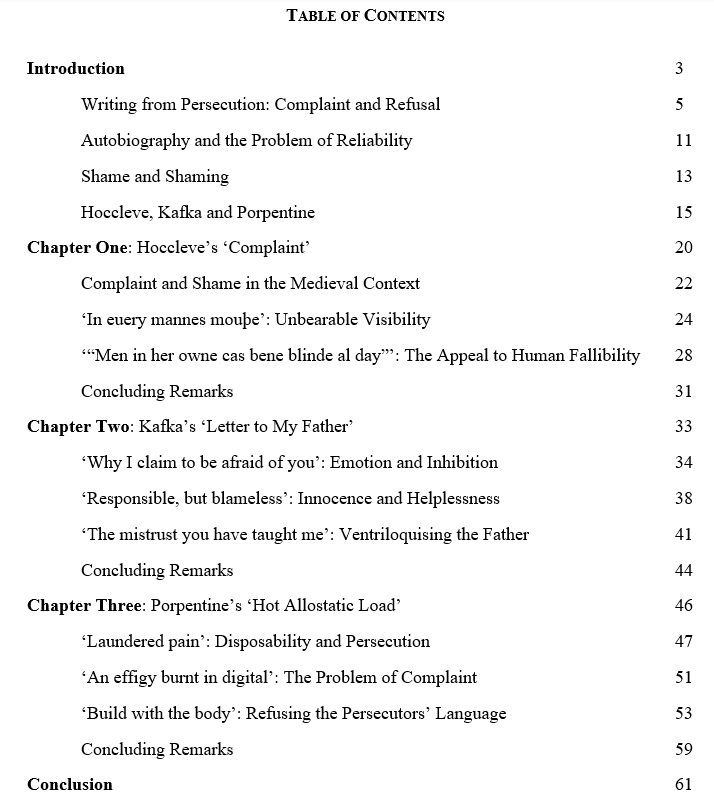

This example, a master’s dissertation on the topic of how writers respond to persecution, shows how you can also use section headings within each chapter. Each of the three chapters deals with a specific text, while the sections are organised thematically.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Like other academic texts, it’s important that your dissertation follows the formatting guidelines set out by your university. You can lose marks unnecessarily over mistakes, so it’s worth taking the time to get all these elements right.

Formatting guidelines concern things like:

- line spacing

- page numbers

- punctuation

- title pages

- presentation of tables and figures

If you’re unsure about the formatting requirements, check with your supervisor or department. You can lose marks unnecessarily over mistakes, so it’s worth taking the time to get all these elements right.

How will you reference your sources?

Referencing means properly listing the sources you cite and refer to in your dissertation, so that the reader can find them. This avoids plagiarism by acknowledging where you’ve used the work of others.

Keep track of everything you read as you prepare your dissertation. The key information to note down for a reference is:

- The publication date

- Page numbers for the parts you refer to (especially when using direct quotes)

Different referencing styles each have their own specific rules for how to reference. The most commonly used styles in UK universities are listed below.

You can use the free APA Reference Generator to automatically create and store your references.

APA Reference Generator

The words ‘ dissertation ’ and ‘thesis’ both refer to a large written research project undertaken to complete a degree, but they are used differently depending on the country:

- In the UK, you write a dissertation at the end of a bachelor’s or master’s degree, and you write a thesis to complete a PhD.

- In the US, it’s the other way around: you may write a thesis at the end of a bachelor’s or master’s degree, and you write a dissertation to complete a PhD.

The main difference is in terms of scale – a dissertation is usually much longer than the other essays you complete during your degree.

Another key difference is that you are given much more independence when working on a dissertation. You choose your own dissertation topic , and you have to conduct the research and write the dissertation yourself (with some assistance from your supervisor).

Dissertation word counts vary widely across different fields, institutions, and levels of education:

- An undergraduate dissertation is typically 8,000–15,000 words

- A master’s dissertation is typically 12,000–50,000 words

- A PhD thesis is typically book-length: 70,000–100,000 words

However, none of these are strict guidelines – your word count may be lower or higher than the numbers stated here. Always check the guidelines provided by your university to determine how long your own dissertation should be.

At the bachelor’s and master’s levels, the dissertation is usually the main focus of your final year. You might work on it (alongside other classes) for the entirety of the final year, or for the last six months. This includes formulating an idea, doing the research, and writing up.

A PhD thesis takes a longer time, as the thesis is the main focus of the degree. A PhD thesis might be being formulated and worked on for the whole four years of the degree program. The writing process alone can take around 18 months.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, May 05). What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/what-is-a-dissertation/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to choose a dissertation topic | 8 steps to follow, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples.

Dissertation in Practice: Reconceptualizing the Nature and Role of the Practitioner-Scholar

Cite this chapter.

- Valerie A. Storey &

- Bryan D. Maughan

446 Accesses

3 Citations

The richness of dialog about the differing approaches to doctoral educational research from the viewpoint of a scholar and from the viewpoint of the professional has been inspiring and continues to shed new light on the role of the practitioner who performs research under the aegis of the academe (Butlerman-Bos, 2008; Drake & Heath, 2011; Hochbein & Perry, 2013; Jarvis, 1999b; Shulman, Golde, Bueschel, & Garabedian, 2006). However, there continues to be a curious lack of understanding about the signature product of a practitioner performing scholarly research who must satisfy the demands of both viewpoints (Dawson & Kumar, 2014; Willis, Inman, & Valenti, 2010). Accountability to traditionally disparate institutions—the academe and professional practice stakeholders (decision-makers)—decries innovative approaches to the capstone product—the dissertation. We will continue this discussion by outlining the unique characteristics of the dissertation produced by a practitioner who performed educational research. We refer to a dissertation produced by a practitioner while in practice as the Dissertation in Practice (DiP) (ProDEL, 2012; Storey & Maughan, 2014). We continue the discussion about how methodologies of applied or practice-oriented research assists the researcher in professional preparation, public service, outreach, and organizational change (Shulman, 2010).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Archbald, D. (2010). “Breaking the mold” in the dissertation: Implementing a problem based, decision-oriented thesis project. Journal of Continuing Higher Education , 58 (2), 99–107.

Article Google Scholar

Bauman, Z. (1987). Legislators and interpreters . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Google Scholar

Beebe, J. (2001). Rapid assessment process: An introduction . Walnut Creek, CA: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bhoyrub, J., Hurley, J., Neilson, G. R., Ramsay, M., & Smith, M. (2010). Heutagogy: An alternative practice based learning approach. Nurse Education in Practice , 10 , 322–326.

Bouck, B. M. (2011). Scholar-practitioner identity: A liminal perspective. Scholar Practitioner Quarterly , 5 (2), 201–210.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice . Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Butlerman-Bos, J. A. (2008). Will a clinical approach make education research more relevant for practice? Educational Researcher , 37 (7), 412–420.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (1999). The teacher research movement: A decade later. Educational Researcher , 28 (7), 15–25.

Choo, C. W. (2006). The knowing organization: How organizations use information to construct meaning, create knowledge, and make decisions (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Christensen, C., Horn, M. B., & Johnson, C. W. (2008). Disrupting class: How disruptive innovation will change the way the world learns . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Costa, A., & Kallick, B. (1993). Through the lens of a critical friend. Educational Leadership , 51 (2), 49–51.

Costley, C., & Lester, S. (2012). Work-based doctorates: Professional extension at the highest levels. Studies in Higher Education , 37 (3), 257–269. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2010.503344

Council of Graduate Schools. (2007). CGS task force report on the professional doctorate . Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools.

Dall’Alba, G. (2009). Learning professional ways of being: Ambiguities of becoming. Educational Philosophy & Theory41 (1), 34–45.

Davis, J. R. (1995). Interdisciplinary courses and team teaching: New arrangements for learning . Phoenix, AZ: American Council on Education, Oryx.

Dawson, K., & Kumar, S. (2014). An analysis of professional practice Ed.D. dissertations in educational technology. TechTrends , 58 (4), 62–72.

De Jong, M. J., Moser, D. K., & Hall, L. A. (2005). The manuscript option dissertation: Multiple perspectives. Nurse Author & Editor , 15 (3), 7–9.

Donovan, G. T. (2013). MyDigitalFootprint.ORG: Young people and proprietary ecology of everyday data . Retrieved from: http://mydigitalfootprint.org /dissertation/.

Drake, P., & Heath, L. (2011). Practitioner research at doctoral level: Developing coherent research methodologies . New York: Routledge.

Duke, N. K., & Beck, S. W. (1999). Education should consider alternative formats for the dissertation. Educational Research , 28 (3), 31–36.

Erwin, E. J., Brotherson, M., & Summers, J. (2011). Understanding qualitative metasynthesis: Issues and opportunities in early childhood intervention research. Journal of Early Intervention , 33 (3), 186–200.

Finch, B. (1998). Developing the skills for evidence-based practice. Nurse Education Today , 18 (1), 46–51.

Fulton, J., Kuit, J., Sanders, G., & Smith, P. (2012). The role of the Professional Doctorate in developing professional practice. Journal of Nursing Management , 20 (1), 130–139.

Gross, D., Alhusen, J., & Jennings, B. M. (2012). Authorship ethics with the dissertation manuscript option. Research in Nursing & Health , 35 (5), 431–434.

Guthrie, J. W. (2009). The case for a modern doctor of education degree (EdD): Multipurpose education doctorates no longer appropriate. Peabody Journal of Education , 84 (1), 3–8.

Gutierrez, K. D., & Vossoughi, S. (2010). Lifting off the ground to return anew: Mediated praxis, transformative learning, and social design experiments. Journal of Teacher Education , 61 (1/2), 100–117.

Hochbein, C., & Perry, J. A. (2013). The role of research in the professional doctorate. Planning & Changing , 44 (3/4), 181–195.

Holmes, B. D., Seay, A. D., & Wilson, K. N. (2009). Re-envisioning the dissertation stage of doctoral study: Traditional mistakes with non-traditional learners. Journal of College Teaching and Learning , 6 (8), 9–13.

Jarvis, P. (1999a). The practitioner-researcher: Developing theory from practice . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Jarvis, P. (1999b). Global trends in lifelong learning and the response of the universities. Comparative Education , 35 (2), 249–257. Retrieved from r0/docview/195149382?accountid=98

Klein, J. T. (2005). Interdisciplinary teamwork: The dynamics of collaboration and integration. In S. J. Derry, C. D. Shunn, & M. A. Gernsbacher (Eds.), Interdisciplinary collaboration: An emerging cognitive science (pp. 23–50). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. E, & Swanson, R. A. (2012). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development . Burlington, MA: Elsevier.

Kram, K. E., Wasserman, I. C., & Yip, J. (2012). Metaphors of identity and professional practice: Learning from the scholar-practitioner. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science , 48 (3), 304–341.

Langley, G. J., Moen, R. D., Nolan, K. M., Nolan, T. W., Norman, C. L., & Provost, L. P. (2009). The improvementguide: A practical approach to enhancing organizational performance . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry . Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Margolin, V. (2010). Doctoral education in design: Problems and prospects. Design Issues , 26 (3), 70–78.

Murphy, J., & Vriesenga, M. (2005). Developing professionally anchored dissertations: Lessons from innovative programs. School Leadership Review , 1 (1), 33–57. Retrieved from http://www.tcpea.org /slr/2005/murphy.pdf

Patton, S. (2013). The dissertation can no longer be defended. Chronicles of Higher Education . Retrieved from: http://ida.lib.uidaho.edu:2282 /article/The-DissertationCan-No-Longer/137215/

Polanyi, M. (1966). The tacit dimension . Chicago, IL: Random House.

Prewitt, K. (2006). Who should do what? Implications for institutional and national leaders. In C. Golde & G. Walker (Eds.), Envisioning the future of doctoral education (pp. 23–33). San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Professional Doctorate in Educational Leadership [ProDEL]. (2012). Dissertation in practice guidelines (DP-2.2-Fa12). Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA: Author.

QAA. (2011). Doctoral degree qualifications . London, UK: QAA.

Reid, W. M. (1978). Will the future generations of biologists write a dissertation? Bioscience , 28 , 651–654.

Reardon, R. M., & Shakeshaft, C. (2013). Criterion-inspired, emergent design in doctoral education: A critical friend perspective. In V. A. Storey (Ed.), Redesigning professional education doctorates: Application of critical friendship theory to the EdD (pp. 177–194). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Robinson, S., & Dracup, K. (2008). Innovative options for the doctoral dissertation in nursing. Nursing Outlook , 56 (4), 174–178.

Shulman, L. S. (2010, April 4). Doctoral education shouldn’t be a marathon. The Chronicle of Higher Education , 56 (30), B9–B12.

Shulman, L. S., Golde, C. M., Bueschel, A. C., & Garabedian, K. J. (2006). Reclaiming education’s doctorates: A critique and a proposal. Educational Researcher , 35 (3), 25–32.

Smith, S. (2014). Beyond the dissertation monograph. Reprinted from the Spring 2010 MLA Newsletter . Retrieved from http://www.mla.org /blog&topic=133

Smith, S., Sanders, G., Fulton, J., & Kuit, J. (2014). An alternative approach to the final assessment of professional doctorate candidates. Paper presented at 4th International Conference on Professional Doctorates , April 10–11, 2014, Cardiff, Wales: United Kingdom Council on Graduate Education.

Sousanis, N. (2015). Unflattening: A visual-verbal inquiry into learning in many dimensions . Harvard, MA: Harvard University Press. Retrieved from http://www.hup.harvard.edu /catalog.php?isbn=9780674744431.

Stevens, D. A. (2010). A comparison of non-traditional capstone experiences in Ed.D. programs at three highly selective private research universities (Order No. 3418175). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Full Text: Social Sciences; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global: Social Sciences (750445117). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com /docview/750445117?accountid=9817

Storey, V. A., & Hartwick, P. (2010). Critical friends: Supporting a small, private university face the challenges of crafting an innovative scholar-practitioner doctorate. In G. Jean-Marie & A. H. Normore (Eds.), Educational leadership preparation: Innovative and interdisciplinary approaches to the EdD and graduate education (pp. 111–133). New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan Publishers.

Storey, V. A., & Maughan, B. D. (2014). Beyond a definition: Designing and specifying Dissertation in Practice (DiP) models . Pittsburgh, PA: The Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate. Retrieved from: http://cpedinitiative.org /findings

Storey, V. A., & Richard, B. (2013). Critical friend groups: Moving beyond mentoring. In V. A. Storey (Ed.), Redesigning professional education doctorates: Application of critical friendship theory to the EdD (pp. 9–25). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Chapter Google Scholar

Stringer, E. T. (2014). Action research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Swaffield, S. (2004). Critical friends: Supporting leadership, improving learning. Improving Schools , 7 (3), 267–278.

Thomas, R. (2015). The effectiveness of alternative dissertation models in graduate education . Unpublished master’s thesis. Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

Thomas, R., West, R., & Rich, P. (2015). The effectiveness ofalternative dissertation models in graduate education . Under Review. Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

Vanderbilt University Peabody College (2015). Ed.D. Capstone Experience. Retrieved from http://peabody.vanderbilt.edu /departments/lpo/graduate_and_professional_programs/edd/capstone_experience/index.php

Willis, J., Inman, D., & Valenti, R. (2010). Completing a professional practice dissertation: A guide for doctoral students and faculty . Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311–318.

Zusman, A. (2013). How new kinds of professional doctorates are changing higher education institutions . Research & Occasional Paper Series: 8.13. Center for Studies in Higher Education, University of California, Berkeley.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Copyright information.

© 2016 Valerie A. Storey and Bryan D. Maughan

About this chapter

Storey, V.A., Maughan, B.D. (2016). Dissertation in Practice: Reconceptualizing the Nature and Role of the Practitioner-Scholar. In: Storey, V.A. (eds) International Perspectives on Designing Professional Practice Doctorates. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137527066_13

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137527066_13

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-56385-2

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-52706-6

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

At Marymount University, we aim to elevate your Online Doctorate in Education (Ed.D.) experience and empower you to make a meaningful impact. You will grow professionally and personally as you delve into meaningful research and leadership topics that will propel your career trajectory.

Gain an advanced understanding of the theory and skills required to become a more confident and strategic leader. Our renowned team of professors and faculty mentors will give you the tools and guidance you need to design solutions for a real-world problem you are passionate about solving. Upon graduation, you will be a published author contributing to the academic and research community for years to come.

Learn more about our innovative Online Ed.D. program that gives you scaffolded support, an embedded dissertation experience and a high-impact community to guide you every step of the way.

Complete The Form to Connect With an Advisor

Dissertation in Practice

Unlike a traditional dissertation, Marymount Online Ed.D. students complete a dissertation in practice (DiP) that emphasizes the application of research and theory to provide a solution to a problem of practice that your organization or industry is facing. A DiP provides a practical and applied focus to actively solve problems in your community or organization. This is in comparison to a traditional dissertation grounded in academic theory, usually associated with prolonged programs and Ph.D. degrees.

The chart below outlines general and key distinctions between each type of dissertation.

Your own research journey may take unexpected and inspiring turns. To give you a glimpse of the exciting possibilities that await, here are some of the dissertation topics Marymount students have completed:

- Empowering Leaders for Effective Organizational Change: Unveiling the SPY2 Methodology

- Leadership Matters: Affecting Social Transformation in Africa