- My Account |

- StudentHome |

- TutorHome |

- IntranetHome |

- Contact the OU Contact the OU Contact the OU |

- Accessibility hub Accessibility hub

Postgraduate

- International

- News & media

- Business & apprenticeships

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

You are here

- School of Arts & Humanities

- Postgraduate Research

Preparing a History PhD proposal

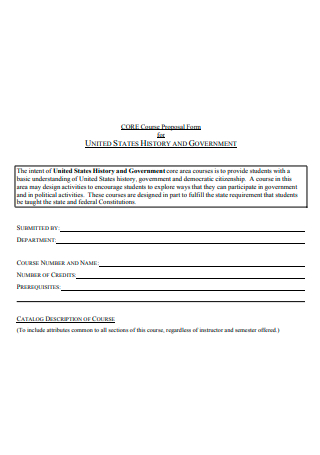

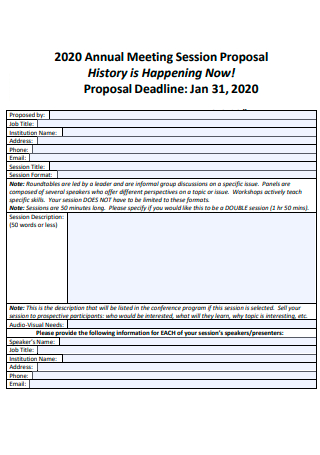

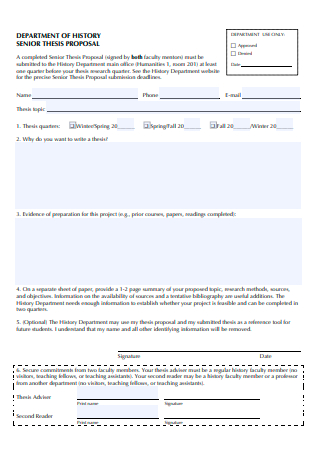

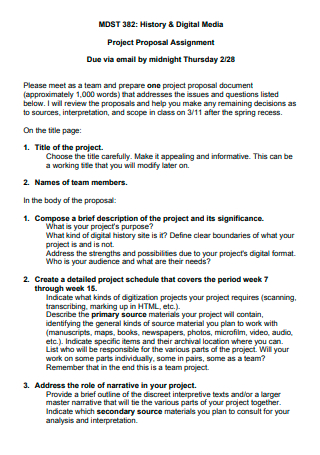

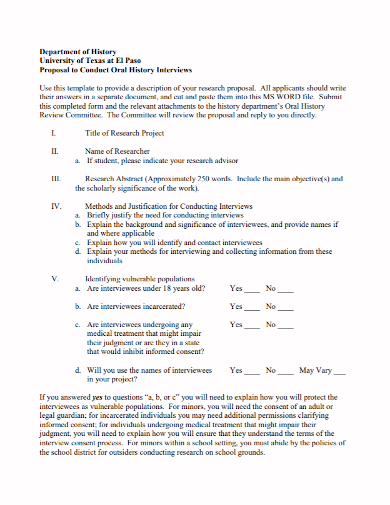

The carefully thought-out and detailed research proposal to be submitted with the formal application is the product of a sometimes prolonged negotiation with your potential supervisor. The supervisor may be enthusiastic about your project or might advise you to consider a different subject or change your angle on it; they may query aspects of your plan such as its breadth, the availability of primary sources or the extent to which you are familiar with the secondary literature. You may be asked to demonstrate the originality of your research question or be advised to consider applying to another institution which may have more appropriate expertise. During this process you will likely be asked to submit a specimen of written-up historical research, such as your Masters or BA dissertation. The sooner you start developing the structure that is expected in a research proposal, the more productive your exchanges with your potential supervisor will be.

You may find different advice for writing a research proposal across different OU webpages. Given that a research proposal can vary significantly across different disciplines, when applying to the History Department you should follow the guidance provided here.

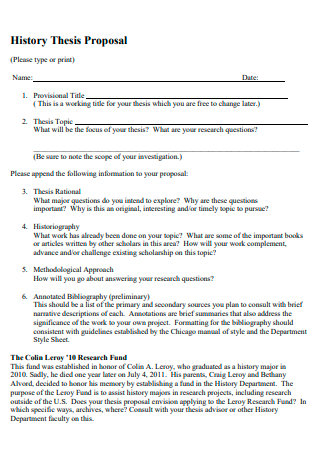

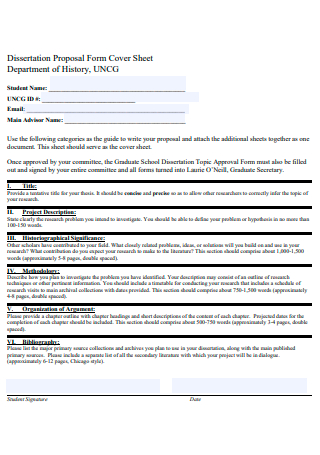

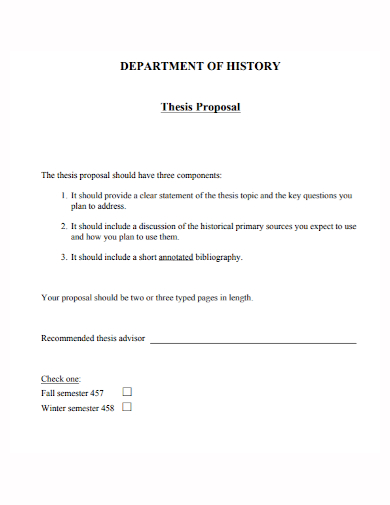

The research proposal you submit in January should be approximately 1000 words, plus a bibliography, and should contain the following:

A title, possibly with a subtitle

The title should not take the form of a question and it may run to a dozen words or more. Like the title of a book, it should clearly convey the topic you propose to work on. A subtitle may explain the chronological or geographical focus of your work, or the methodological approach you will take. Choosing a title is a good way for focusing on the topic you want to investigate and the approach you want to take.

These are examples of poor titles and topics to research:

- Captain Cook’s Third Voyage

- Women in eighteenth-century England

These would be poor topics to research because they lack a strong question and it is not clear which approach they take to their already well-researched subjects. They are generic or merely descriptive.

Examples of good research topics

- Constructing the Eternal City: visual representations of Rome, 1500-1700

- Rearing citizens for the state: manuals for parents in France, 1900-1950

These projects combine a sharp chronological and geographical focus with a clear indication of how the sources will be analysed to respond to a precise question. In the first case, for example, the premise is that visual representations are critical in the making of a city’s eminence. This indicates the type of sources that will be analysed (paintings, engravings and other visual sources). The chronology is particularly well chosen because in these two centuries Rome turned from being the capital of the Catholic world to becoming the much sought-after destination of the Grand Tour; interesting questions of change and continuity come into focus.

Brief summary of your argument

An acceptable PhD thesis must have a central argument, a 'thesis'. You need to have something to argue for or against, a point to prove or disprove, a question to answer. What goes into this section of the proposal is a statement of your question and the answer you plan to give, even if, for now, it remains a hypothesis.

Why this subject is important

We expect originality in a thesis and so under this rubric we expect you to explain why the knowledge you seek on the subject you propose to work on is important for its period and place, or for historians’ views on its period and place. Finding some early-modern English laundry lists would not suffice on its own to justify writing a PhD thesis about them. But those laundry lists could be important evidence for a thesis about the spread of the Great Plague in London, for example.

Framing your research

Your proposal has to show awareness of other scholarly writing on the subject. This section positions your approach to the subject in relation to approaches in some of those works, summarising how far you think it differs. For instance, you could challenge existing interpretations of the end the Cold War, or you might want to support one historian or another; you could open up a neglected aspect of the debate - say by considering the role of an overlooked group or national government - and perhaps kick-start a debate of your own. All this is to show that you have read into your subject and familiarised yourself with its contours. We don’t expect you to have done all your research at the start, but it is essential for you to show familiarity with the key texts and main authors in your chosen field.

What sources might you need to consult in libraries and archives?

Here you should describe or at least list the primary materials you are likely to use in researching your thesis. This demonstrates your confidence that enough relevant sources exist to support a sustained scholarly argument. Many archival catalogues are available online and can be searched remotely, including The National Archives, the National Archives of Scotland, the National Archives (Ireland), the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland and Archives Wales. You can search the London-based Historical Manuscripts Commission and the National Register of Archives, both of which provide access to local county record offices. Databases such as ‘Eighteenth Century Collections Online’ and the British Library’s ‘British Newspapers Online 1600-1900’ will help you identify and locate relevant sources.

What skills are required to work on the sources you plan to use?

You need to show that you have the linguistic competence to pursue your research. With few exceptions, original sources must be read in the original languages; if the principal historical literature is not in English, you must be able to read it too. Palaeographic problems aren’t confined to ancient writing. You might have to tackle early modern or other scripts that are hard to decipher. Even with fluent German, an applicant baffled by the Gothic script and typeface would flounder without undertaking ancillary study. Training is available at The Open University, or in some circumstances you can be funded to undertake training elsewhere, and you should demonstrate awareness of the skills that you need to acquire.

Do you have the technical competence to handle any data-analysis your thesis may require?

Databases, statistical evidence and spreadsheets are used increasingly by historians in certain fields. If your research involves, say, demographic or economic data, you will need to consider whether you have the necessary IT and statistical skills and, if not, how you will acquire them.

How will you arrange access to the libraries and archives where you need to work?

Although primary sources are increasingly available in digitised form, you should consider that important sources may be closed or in private hands. To consult them may require some travelling and so you should be realistic as to what you will be able to do, particularly if you are applying to study part-time as not all archives are open out of regular office hours.

A bibliography

This should come at the end and include a list of the primary sources you plan to use and the relevant secondary literature on the subject. While you should show that you are on top of recent work (and of important older studies) on the topic, there is no point in having a long list of works only marginally related to your subject. As always, specificity is the best policy.

Please follow this link to see an example of a successful research proposal [PDF].

All this may seem daunting, as if the department is asking you to write a thesis before you apply. But that is not our intention; the advice is to help you perform the necessary spadework before entering the formal application process. Working up a proposal under the headings suggested above will, if your application is successful, save you and your supervisor(s) much time if and when the real work begins.

- Study with Us

- News (OU History Blog)

- @history_ou

Request your prospectus

Explore our qualifications and courses by requesting one of our prospectuses today.

Request prospectus

Are you already an OU student?

Go to StudentHome

The Open University

- Study with us

- Work with us

- Supported distance learning

- Funding your studies

- International students

- Global reputation

- Sustainability

- Apprenticeships

- Develop your workforce

- Contact the OU

Undergraduate

- Arts and Humanities

- Art History

- Business and Management

- Combined Studies

- Computing and IT

- Counselling

- Creative Arts

- Creative Writing

- Criminology

- Early Years

- Electronic Engineering

- Engineering

- Environment

- Film and Media

- Health and Social Care

- Health and Wellbeing

- Health Sciences

- International Studies

- Mathematics

- Mental Health

- Nursing and Healthcare

- Religious Studies

- Social Sciences

- Social Work

- Software Engineering

- Sport and Fitness

- Postgraduate study

- Research degrees

- Masters in Social Work (MA)

- Masters in Economics (MSc)

- Masters in Creative Writing (MA)

- Masters in Education (MA/MEd)

- Masters in Engineering (MSc)

- Masters in English Literature (MA)

- Masters in History (MA)

- Masters in International Relations (MA)

- Masters in Finance (MSc)

- Masters in Cyber Security (MSc)

- Masters in Psychology (MSc)

- A to Z of Masters degrees

- OU Accessibility statement

- Conditions of use

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Manage cookie preferences

- Modern slavery act (pdf 149kb)

Follow us on Social media

- Student Policies and Regulations

- Student Charter

- System Status

- Contact the OU Contact the OU

- Modern Slavery Act (pdf 149kb)

© . . .

Megamenu Global

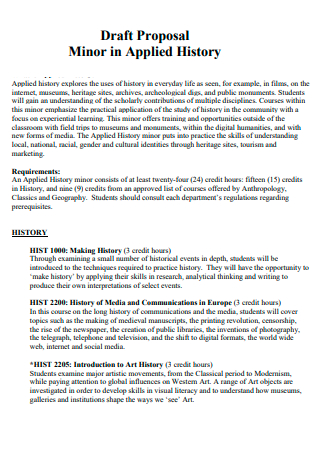

Megamenu featured, megamenu social, sample thesis proposals.

Lanfranc of Bec: Confrontation and Compromise Imperial Expansion and the Evolution of the South and Southeast Asian economies Nantucket’s Role in the War of 1812 Letters Home: Records of the Experiences of Common Soldiers in the American Civil War Writing for Stalin: American Journalists in the USSR, 1928-1941 Dismal Scientists, Diplomats, and Spooks: Bissell, Milliken, and Rostow and Their Impact on U.S. Foreign Policy Media Reflections of Western Public Opinion in the Suez Crisis The Implications, Effects, and Uses of Media in the Emmett Till Lynching Cromwell Lives while Mason Stalks: Irish Nationalism and Historical Memory during the Troubles ‘My broken dreams of peace and socialism’: Youth propaganda, personality, and selfhood in the GDR, 1979-1989.

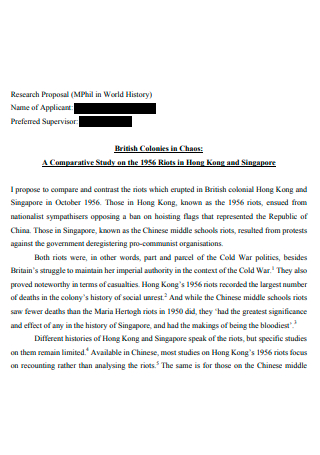

Lanfranc of Bec: Confrontation and Compromise

The ecclesiastical history of Europe in the 11th century revolves around the investiture conflict and the Gregorian reform effort. These two issues forced their way into religious lives around the continent. Even in England, on the edge of the world, Anglo-Saxon and Norman reformers grappled with these challenges to the construction of a “universal church.” I would like to enter into this world through the case study of Lanfranc of Bec. Lanfranc is an apt choice for this intensive focus because of the apparent philosophical paradoxes that dominated his life.

Early in his career, Lanfranc was a staunch supporter of Pope Leo IX in the Eucharistic controversy with Berengar of Tours. The doctrine of transubstantiation was, however, less important to Lanfranc than the idea of “the universal church.” Significantly, this new church was to be united under the stronger and more demanding popes in Rome who were early supporters of the young Italian monk. Lanfranc’s transformation began when was appointed abbot of St. Etienne, Caen in 1063 under the direct patronage of William the Conqueror. This relationship continued with Lanfranc’s promotion to Archbishop of Canterbury in 1070. In this role, Lanfranc severed all most traditional ties with Rome. He did command the right to supervise and veto any papal synods planned for England. In addition, Lanfranc even skipped the mandatory pilgrimage to Rome to receive the pallium, a tradition for English bishops that dated back to Gregory the Great and the 6th century.

Traditional scholarship has tended to portray this break as pragmatic. Lanfranc’s new master, William, demanded a more present loyalty than the faraway Church of St. Peter’s. Loyalty in turn led to advancement and a place in religious governance of countless souls in England. To justify these mercenary considerations scholars described the admittedly conservative Lanfranc as a Carolingian bishop, a relic of an empire then dead for two centuries. The Carolingian era was a time of dramatic expansion for the church, largely under the protections of its secular Christian protector, Charlemagne. It is easy to see parallels, at least from the Norman point of view, between the conquest of England in 1066 and the forceful conversion of the Saxons in 8th century. Both these invasions brought subject peoples in line with a new, larger Christendom. Historians have written about Lanfranc as a player within this system of sacred reform spearheaded by the secular.

In my study I plan to reexamine this view. Although the Archbishop did abandon Gregory VII at the time of his greatest need, the investiture conflict, Lanfranc’s role in the English reform need not be seen as driven by Normandy rather than Rome. For example, William’s concern for the piety of his new subjects was at best secondary to an interest in appointing bishops who would maintain order on the tumultuous island in place of the absentee king. Thus it was with a relatively free hand that Lanfranc directly reformed both Canterbury and England as a whole. Some of these changes, like his emphasis on clerical celibacy, were directly in line with the Gregorian reforms that he had supposedly renounced upon his arrival. In other instances, Lanfranc was more open minded to the religious practices that preceded him. Unlike other Norman bishops that arrived after the conquest, the Archbishop was far more accommodating to both local English saints and the institution of monastic cathedrals. These examples create a far more complex picture of Lanfranc. It is clear that he was more loyal to the Gregorian reform movement than to any particular pontiff occupying the See of St. Peter. At the same time, his syncretistic approach would have been at odds with any of the uncompromising popes that he had dealings with. These incongruous details suggest the need to revise traditional interpretations of Lanfranc’s life. Within a wider scope, I hope to demonstrate how the clergy positioned themselves in the larger conflict between the church and state at this time.

In pursuing this topic I want to integrate traditional and less traditional sources in an attempt to create a fresh portrayal. Any study of medieval political and ecclesiastical history will rely heavily on the chroniclers. Specifically I will use the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Eadmer’s Vita Anselmi for the Anglo-Saxon perspective. For the Norman point of view I will use chronicles by William of Jumièges and Gilbert Crispin. To supplement these more formally produced histories, I will read Lanfranc’s own works including his major treatise on the Eucharist, the Liber Corpore et Sanguine Domini, which I fail to believe he so easily abandoned on his arrival to England. In addition, his personal correspondence and monastic constitutions, both of which have been recently republished, will be usefully in understanding his own views, whether they be practical or theological. Lastly, I want to use architectural analyses of the church that Lanfranc built at Canterbury and studies of relic worship surrounding the remains of local saints like Dunstan and Theodore. These less traditional sources, while harder to obtain, will, I hope, provide new insight into Lanfranc’s life and, at the very least, provide social and cultural context for this specific period. The result will be a study that uses the analysis of Lanfranc to address larger question concerning the orientation of individuals within 11th century conflicts.

Back to top of page

Imperial Expansion and the Evolution of the South and Southeast Asian economies

The arrival of Vasco De Gama in 1498 on the beaches of modern-day Calicut marked the beginning of the intensification of economic relations between East and West, and the first encounter of Europeans with an ancient and complex commercial network reaching by land and sea from Europe to China, handling trade and traffic of far greater value than anything known in the West. Luxury products from China, silk and precious metals from Iran, the cotton textiles of India, the gold and ivory of East Africa, and the spices of Indonesia were all connected through highly advanced and dense trading networks. While the Indian economy is often represented as having stagnated under the weight of European intrusions, it is clear that particularly in coastal areas, a brisk and dynamic coastal trade flourished under the aegis of European rule. The creation of a world market in commodities such as rice gold, silver, spices, textiles and other raw materials occurred simultaneous with displacement of local markets as European imperial reach was extended over an increasingly wide part of the globe.

By the mid 18th century, the two great chartered companies, the British East India Company and the VOC (Dutch East India Company) had transformed from mere commercial trading ventures to entities that dominated economic relationships with Asian economies and began to acquire auxiliary governmental and military functions. By 1765 the British East India Company was effectively the de facto sovereign in Bengal by virtue of its overwhelming military power in the region, and its acquisition of the diwani, or the right to collect territorial revenues. For both the Dutch and British East India Companies, it is clear that the acquisition of territorial empires and quasi-governmental functions had profound effects upon the nature, scope, and distribution of investment within the Companies from Europe, but also upon the character of the relationship between indigenous traders, merchants, and financiers, and Europeans. Lakshmi Subramanian, a historian who has published some of the most important works dealing with the relationship of the Marathas and the British in Bombay, mentions how Law de Lauriston, the ex-Governor General of French India, “recognized the local banking community in 1777 as the decisive factor in any future alliance of the French and Indian States against their inveterate antagonist the English East India Company.” In a recent paper Chaudhury asserts how the local credit markets of eastern India, particularly Bengal, were seminal in rescuing financially several of the European Companies in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries from chronic shortages of working capital, yet with victory at Plessy and the transformation of the British role in Bengal, the nature of the relationship between local creditors and European merchants changed dramatically.

This project will comparatively look at the Dutch and British East India Companies and their relationships with groups such as the Marathas, the Chettiars, and the Chinese banking and mercantile families, and will draw upon resources that deal with the relationships of other European powers with indigenous merchants and financiers. By examining the interaction of indigenous financial institutions and capital with Europeans in Asia, particularly South and Southeast Asia, I am hoping to explore many aspects of the Asian economies of the 17th-19th century under the aegis of this broader topic, such as the different development paths between European and Asian societies, the dynamics of the extension of European power in south and southeast Asia, and the radically different financial and economic structures that characterized Asian societies prior to the expansion of Europe, and how the imposition of colonial rule altered (or didn’t) the dynamics of indigenous capital. This project will look at the relationship from the European perspective by utilizing Dutch and British East India Company records. Particularly in recent years, several historians have sought to expand our understanding of the relationship between European traders and Indian merchants and financiers, and this project will attempt to both build upon their work and form a more global and far-reaching conclusion about the role of indigenous capital in imperial expansion by looking at the phenomenon from a comparative perspective.

The chief question I am seeking out to answer is to define and delineate the nature of the relationship between indigenous credit institutions and imperial expansion; effectively, examine the relationship between native bankers, financiers, and traders, and the Europeans who came to trade and later colonize. Above all, I hope to posit a link between these economic relationships, and changes to the political and economic map of Asia.

Nantucket’s Role in the War of 1812

I am a junior history major currently studying abroad at the Williams-Exeter in Oxford Programme. Since August, I have been casually researching the whaling industry on Nantucket during the late 18th to mid-19th century. I am committed to Nantucket as a general topic not only because its history is exceedingly interesting to me but also because there is a wealth of primary data. For example, the Nantucket Historical Association boasts 5000 volumes (ship logs, diaries, legal documents, etc.) that are accessible to scholars.

Although I have explored a number of topics within Nantucket history, I find myself returning again and again to the whaling industry. In particular, I am intrigued by Nantucket’s role in the 1812 war. Nantucket was the only US territory to seek and receive a truce with Great Britain, formally withdrawing from the war in 1814. The islanders were motivated to pursue neutrality because of the importance of the whaling industry as the island’s livelihood and the British fleet’s threat to Nantucket ships. Furthermore, the US government not only offered little to no protection for the islanders but also alienated them by taxing them heavily. In order to understand the1814 treaty, I anticipate needing to research two other areas that I believe are connected: first, how did Nantucket’s experiences in the American Revolution inform and shape its course of action in 1812? During the Revolution, the island declared neutrality, probably because Nantucket whalers did not care which side was victorious, so long as the whaling industry survived the war. The whalers had appealed to other Quakers in England and won an amendment to the parliamentary motion to restrict whaling in New England. However, because the law was not enforced properly, the island fell into economic depression. British naval ships not only prevented Nantucket whalers from selling spermaceti oil to London, its biggest market, but also captured many of their ships. Any threat to the whaling industry would be a true moment of crisis because most of the island was directly or indirectly involved in whaling, and many of the islanders were not rich enough to relocate their families to the mainland. Certainly, there were members of the community in 1812 who would have remembered this treatment by the British and the economic depression.

The second issue that I anticipate addressing pertains to Nantucket’s sense of identity: how “American” did they feel? The circumstances under which the island declared neutrality makes the issue of patriotism more oblique because the “betrayal” of the US can be explained by the need for economic stability without addressing the issue of identity. In these early stages of nationhood, the island seems to have acted very differently from other whaling communities in the US. Socially and politically, Nantucket seemed to be more liberal than the mainland, especially in terms of the role of women and the political (but not always social) equality of African Americans. For example, racial segregation in schools was banned in the 1850s in a legal case that resembles Brown vs. Board of Education. As I have mentioned above, American policies also sometimes alienated the islanders. In the first two years of the 1812 war, Nantucket whaling was almost exclusively threatened not by the British fleet but by American policy, as Congress placed an embargo on trade with Britain; unfortunately, only days after Congress lifted the embargo, Britain enforced is own against New England. During the American Revolution, Nantucket toyed with the idea of becoming either an independent or a British territory. Did it face the same choices in 1812?

Primary Sources :

A Selection from the Nantucket Historical Society Manuscripts Collection:

Allen Family Papers, 1790-1930. Banks on Nantucket, 1804-1985. Barker Family Papers, 1720-1853. Benevolent Society’s Papers, 1814-1976. Carey Family Papers, 1809-1894. Citizens News Room Record. Charles Congdon Collection, 1671-1844. Clapp Family Papers, 1804-1896. Margaret Coffin Papers/Small Collection, 1761-1913. Mary M Coffin Collection, 1806-1865. William Coffin Letter Book, 1811-1833. Coleman Family Papers, 1729-1873. Crosby Family Papers. 1812-1893. Ewer Family Papers, 1813-1875. Fish Family Papers, 1708-1916. Paddock Family Papers, 1755-1853, Phebe Coffin Hanaford Papers, 1848-1929. Jones Family Papers, 1817-1868. Joy Family Papers, 1806-1880. Keziah Coffin Fanning Papers, 1775-1812. Macy Family Papers/ Cloyes Collection, 1812-1869. Myrick Family Papers, 1796-1863. Nantucket Censuses Collection, 1796-1900. Nantucket Monthly Meeting of Friends’ Papers, 1664-1889. Nantucket Monthly Meeting of Friends’ Records, 1672-1944. Ray Family Papers, 1776-1844. Starbuck Family Papers, 1662-1973. Worth Family Papers, 1743-1912. Henry Barnard Worth Collection, 1641-1905.

(I’ve only gone through half of the list of available manuscripts, so I expect that there should be a lot more sources of interest from the Nantucket Historical Society collection. Information about Nantucket Historical Society archives found on www.nha.org)

Annals of Congress, 13th Congress, 2d session. Hutchinson, Thomas. History of Massachusetts, Vol. II, Boston: Thomas & Andrews, 1767. Journal of Samuel Swain, 1813-1837. “Keziah Coffin Fanning’s Diary,” Historical Nantucket 6 (July 1958). Macy, Obed. The History of Nantucket (New York: Research Reprints, 1970 [1835]). Napier, Henry Edward. New England Blockaded in 1814: The Journal of Henry Edward Napier, Lieutenant in H.M.S ‘Nymphe,’ ed. Walter Muir Whitehill. Salem, MA: Peabody Museum, 1939. “Notes on Nantucket. August 1st 1807,” Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society 3 (1815). Scoresby, William. History and Description of the Northern Whale Fisheries, Vol. II. Edinburgh, 1820.

Secondary :

Anderson, Florence Bennet. Through the Hawse-Hole: The True Story of a Nantucket Whaling Captain. New York: Macmillan Co., 1932. Byers, Edward. The Nation of Nantucket: Society and Politics in an Early American Commercial Center, 1660-1820. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1987. Graham, Gerald S. “The Migrations of the Nantucket Whale Fishery: An Episode in British Colonial Policy.” The New England Quarterly 8, no. 2 (Jun. 1935):179-202. Davis, Ralph. The Rise of the English Shipping Industry in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. London: David & Charles, 1972. Hegarty, Reginald B. Returns of Whaling Vessels Sailing from American Ports: A Continuation of Alexander Starbuck’s “History of the American Whale Fishery” 1876-1928. New Bedford, MA: Old Dartmouth Historical Society and Whaling Museum, 1959. Hickey, Donald R. “American Trade Restrictions during the War of 1812.” Journal of American History 68, no. 3 (Dec. 1981): 517-538. Hohman, Elmo Paul. The American Whaleman: A Study of the Life and Labor in the American Whaling Industry. New York: Longmans, Green & Co., 1928. Horsman, Reginald. “Nantucket’s Peace Treaty with England in 1814.” New England Quarterly 54, no. 2 (Jun. 1981): 180-198. Horsman, Reginald. The War of 1812. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1969. Johnson, Robert. “Black-White Relations on Nantucket.” Historical Nantucket (Spring 2002). Taken from www.nha.org. Kugler, Richard C. “The Whale Oil Trade, 1750-1775,” Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1980. Main, Jackson Turner. The Social Structure of Revolutionary America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965. McDevitt, Joseph L. The House of Rotch: Whaling Merchants of Massachusetts, 1734-1828. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1986. Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Maritime History of Massachusetts, 1783-1860. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1979. Tower, Walter. A History of an American Whalefishery, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1907. Starbuck, Alexander. History of Nantucket, Boston: C. E. Goodspeed Co.,1924. ______. History of the American Whale Fishery from Its Earliest Inception to the Year 1876. Repr., 2 vols., with preface by Stuart C. Sherman. New York: Argosy Antiquarian, 1964. Vickers, Daniel Frederick. “Maritime Labor in Colonial Massachusetts: A Case Study of the Essex County Cod Fishery and the Whaling Industry of Nantucket, 1630-1775.” Ph.D. Thesis, Princeton University, 1981.

Letters Home: Records of the Experiences of Common Soldiers in the American Civil War

The idea for my honors thesis project is inspired by my work last summer in the Chapin Library of Rare Books at Williams. I spent the summer reading and organizing the library’s collection of Civil War soldiers’ letters—a group of about one thousand letters written by men in army camps to the loved ones they left behind at home. Besides a cursory chronological arrangement, no one before me had touched these letters since the library acquired them. For me they represented a vast untapped historical resource—they were sitting in a closet waiting to be discovered, and I was the first to explore their possibilities. I found myself completely absorbed, squinting at line after line of cramped, faded script and imagining the words flowing haltingly from the authors’ pens as they crouched by the light of a sputtering campfire, the booming of cannon fire echoing in the distance. It fascinated me how these young men portrayed their experiences to family members back home—reassuring them of their safety and expressing enthusiasm for their causes while also betraying paralyzing fear and devastating homesickness. In one particularly memorable series of letters a Union soldier continued to write home to his wife from the battlefield during a siege of a Confederate fort, knowing that no mail was running and suspecting that the days he spent crouching under fire in the brush of a Louisiana forest would be his last. But somehow his letters did get through, and the final letter in the sequence told of his harrowing escape to a field hospital, giving me the hope that he and his wife were reunited soon afterwards.

The words of letters like these haunted me after I left work everyday, and stayed with me even after I left Williams for the year. As I started thinking about my plans for my honors thesis, I knew that I wanted to work closely with the letters in the Chapin collection. In my thesis, I plan to explore the average soldier’s experience of the war, using Union and Confederate sources in the form of the letters soldiers sent home to their families and friends. The Chapin Library’s collection is mainly made up of Union letters, so the Union side will be heavily based upon that resource. For the upcoming summer, I have been granted a summer research fellowship from Williams. My plan for this project is to gather resources from the Confederate side, visiting facilities in Virginia that hold extensive collections of Confederate letters. I am deeply interested in letting the authors of the letters speak for themselves so I will be comparing and contrasting specific experiences related by specific soldiers in relation to broader questions such as what reasons Union and Confederate soldiers gave for fighting, whether the views they express in their letters aligned with the professed views of their respective causes, what they knew—if anything—about these causes, and what they thought of one another. Perhaps most of all I would like to use these primary documents to emphasize how the soldiers on opposing sides were alike—how they commonly identified with certain ‘American’ values and ambitions, and how their views on the War were shaped significantly by the coincidence of which side of the divided country they happened to be born on.

I believe letters like these offer historians an invaluable means for stepping inside the minds of the actors who participated in historical events. And the particular set of letters I will examine in my project is important because it does not tell the ‘great man’ version of the Civil War, governed by figures like Abraham Lincoln and Robert E. Lee. Instead, it gives us a broader sense of the common man’s—in this case the common soldier’s—experiences of events that fundamentally shaped the American past. This is a version of the past that is often inaccessible to us, so it is important for historians to take advantage of resources like those housed in the Chapin Library. It is impossible for me to encompass all the perspectives and experiences offered by surviving Civil War letters, which is why I have chosen to focus my research closely on the Chapin collection, which is manageably sized and within convenient proximity to me for research during the academic year. After working with those letters for several months, I feel that I have a general sense of what they have to offer—a representative sample of the experiences of the common soldier in the war. In my research in the South this summer, I plan to supplement the Chapin collection with more Confederate examples. I also plan to draw inspiration from secondary sources, a small collection of which I have listed below. Many scholars have worked from Civil War soldier’s letters in the past, and they have even infiltrated popular culture to a considerable extent—most famously through Ken Burns’ Civil War documentary. These authors will help me to get a sense of wider patterns in the experiences of soldiers, but I will rely upon my reading of primary sources to draw out specific examples.

The most exciting thing about my proposed thesis for me is that I really do not know what I will find or where my research will take me. I suspect that there are an inexhaustible number of topics that may be drawn out from Civil War soldiers’ letters, and I am confident I will find many things in my research that will inspire me. I am deeply committed to approaching history through contact with authentic documents and artifacts, and I look forward to the opportunity to do this over the course my project next year.

Preliminary Bibliography :

Primary sources: I will rely heavily upon the collection of approximately one thousand Civil War letters in the collection of the Chapin Library of Rare Books at Williams for the Union perspective. For the Confederate point of view, I will use collections of letters held by the Virginia Historical Society, the Museum of the Confederacy, and the Library of Virginia, all in Richmond, as well as the library of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. There are also collections of letters accessible online, in particular The American Civil War: Letters and Diaries at http://solomon.cwld.alexanderstreet.com/.

Secondary sources :

Barton, Michael, and Larry M. Logue, eds. The Civil War Soldier: A Historical Reader. New York: New York University Press, 2002. Manning, Chandra. What This Cruel War Was Over. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007. McPherson, James M. The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ______. For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ______. What they Fought For, 1861-1865, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994. ______, ed. The Mighty Scourge: Perspectives on the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. ______ and William J. Cooper, Jr., eds. Writing the Civil War: The Quest to Understand. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998. Mitchell, Reid. Civil War Soldiers, New York: Viking, 1988. ______. The Vacant Chair: The Northern Soldier Leaves Home. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. Rosenblatt, Emil & Ruth, eds. Hard Marching Every Day: The Civil War Letters of Private Wilbur Fisk, 1861-1865, Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992. Sheehan-Dean, Aaron. The View From the Ground: Experiences of Civil War Soldiers, Wiley, Bell I. The Life of Billy Yank. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008. ______. The Life of Johnny Reb, the Common Soldier of the Confederacy. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1943. ______. The Plain People of the Confederacy. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000.

Writing for Stalin: American Journalists in the USSR, 1928-1941

“There is no famine or actual starvation nor is there likely to be.” So wrote the Moscow bureau chief for The New York Times, Walter Duranty, on November 15, 1931. By the end of 1933, between six and eight million Soviet citizens, at least half of them Ukrainians, had perished in the wake of consecutive failed harvests and official repression, in one of the worst man-made famines in history. Duranty won his Pulitzer Prize a year before the end of the famine. Duranty was not alone in his whitewashing of the Soviet Union in general and Stalinist policy in particular. Journalists from all over the world writing from the USSR depicted a land of noble struggle, where the working class, guided by leader and Party, were forging a utopia free from the injustice and squalor of capitalism. Why did so many Western visitors to the USSR allow themselves to become mouthpieces for the Soviet regime, with evidence of political repression and hideous suffering all around them, while only a few observers spoke out against the communist regime? What was the appeal of Stalinism in this age of the great crisis of capitalism? The 1930s were a time of uncertainty for liberal democracy, with the Great Depression causing misery across the world and calling into question the old liberal creeds of free market capitalism, while democracy itself was under siege from totalitarianisms of the left and right. To attempt to encompass this immense crisis in an entire book, let alone a thesis, would be a daunting task. Instead, I propose to probe this crisis through the microcosm of the men and women who visited the Soviet Union hoping to find a workers’ utopia. Many Westerners came to the USSR at the invitation of the regime, as journalists, technical experts, and travel writers who left behind an impressive body of news reports, diaries, letters, and memoirs. My thesis project will examine a particular subset of these visitors—the American journalists writing for US papers like The Nation, Harper’s, The Atlantic Monthly, and The New York Times, or English-language publications in the USSR like The Moscow News. The time frame discussed will open with the launch of the first Five Year Plan in 1928, and conclude with the entry of both the Soviet Union and the United States into the Second World War in 1941. I will further focus my project on the coverage of two particular events: the much-denied famine taking place in the Ukraine, and Stalin’s Purge-era show trials, where many observers wrote either that those on trial really were saboteurs and agents of foreign powers, or that their guilt or innocence was of little consequence in the grand historical drama that was unfolding. I choose these two events because they represent indictments of the Soviet system’s claim to legitimacy—its ability to feed all its people, and its claim to be a truly fair society. The gymnastics of fact and logic undertaken by the regime’s apologists on these points are thus of particular significance.

So far, the question of what it was about most journalists visiting the USSR in this period, and what it was about Soviet communism, that made most reporters toe the Party line has not been addressed in particularly great depth. Today, those who favored the regime, like Walter Duranty, Maurice Hindus, and Anna Louise Strong, tend to be dismissed as ideological hacks, either willfully ignorant or purposely lying in the service of socialism. Those who see through the regime’s cloud of deception are by contrast heroic truth-tellers. A certain amount of work has been done on official Soviet efforts to win over liberal-minded Westerners in this period, and the Duranty Pulitzer Prize controversy has generated a number of articles and books in recent years, most notably S.J. Taylor’s Stalin’s Apologist. However, the historiography leaves open a number of questions. Were the journalists reluctant to speak against the regime because they could lose their access to the leadership, because their families might be targeted (many married in Russia), or similar, practical causes? To what extent did the practical intersect with the ideological as reporters sympathized with the official ideology and goals of the regime, and were prepared to forgive a little gangsterism on the part of the leadership if it would bring about a genuinely fair and equal society? As Duranty put it in his article of May 14th, 1933, “You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.” Was there something about the generally well-meaning liberalism of the American journalists that led them in droves to whitewash the crimes of Stalinism in service of some genuinely laudable social projects like universal literacy and the welfare state, as well as a powerful vision of a society that could come to be? Moreover, how were these journalists’ points of view informed by the society that produced them? What, if any, were the differences in the attitudes of those who were foreign-born, like Duranty and Hindus, and those like Strong who were natural-born citizens? To what extent did the reporters’ experience of Depression-era America, with all its hunger and inequality, influence their perception of the Soviet Union, which claimed to eliminate all such evils of capitalism?

In seeking an explanation of why so many American reporters upheld the Stalinist line in this period, I plan to explore three distinct sets of sources. First, I will examine the actual newspaper reports produced by these journalists. Americans reporting from Moscow were well aware that they were virtually the only source of information about events inside the USSR available to Americans, and their articles naturally give a great deal of insight into how they hoped to explain the Soviet system to the American public. Next I will consider more private sources like the reporters’ diaries and letters, which may shed light on the internal thoughts, goals, motivations, and reservations of the journalists, and include thoughts that were left out of their news articles or later memoirs. Finally, I will consider the memoirs that many journalists wrote during or directly after this period about their experiences in the USSR. The memoirs that I have read so far are extremely rich sources, raising a number of important questions of methodology. How far can we trust these reporters, who often wrote several years after the events they witnessed? Were the memoirs published before or after the Soviet Union had become engaged in the battle against fascism, either indirectly in Spain, or directly after 1941? Are these memoirs little more than cases of special pleading by journalists hoping to prop up both the great idea of communism and their own reputations? The memoirs by those reporters like Eugene Lyons who defied the safe consensus of their colleagues and wrote against Stalinism (often at the price of their careers) present a fascinating set of outliers. Can we trust such former sympathizers to report the truth as they saw it, or do conversions from fellow traveler to anticommunist attack dog represent swings between extremes of endorsement and repulsion, implying unreliability? These sources, both the ones I encountered and wrote about in my tutorial last term with Robert Service, as well as those I have come across since, will constitute a very rich base for my research.

Using this source material, I am seeking to tie together the grand political and ideological debates of the 1930s and the personal lives of the journalists in question to explain why so many of these men and women embraced Stalinism, while a few wrote furious condemnations of the Soviet system. This project will in many ways be an exploration of the crisis of capitalism and seeming rise of socialism in microcosm, driven by the particular nuances and intricacies of my particular material. In 2010, it seems all too obvious to us that Stalinism was a nightmare for millions of Soviet citizens, but eighty years ago, it was still very much an open question whether the future belonged to capitalism or communism. Those who made excuses for Stalinism sometimes did so for the best of reasons. However, that so many people could be so wrong about Stalinism demands an explanation.

Dismal Scientists, Diplomats, and Spooks: Bissell, Milliken, and Rostow and Their Impact on U.S. Foreign Policy

As the current global economic crisis shakes countries around the world, its effects resonate beyond the realms of financial regulators, central banks, and finance ministries. This crisis has created a number of foreign policy challenges for the United States government, and Director of National Intelligence Dennis C. Blair recently declared to the Senate intelligence committee, “The primary near-term security concern of the United States is the global economic crisis and its geopolitical implications.” Blair, however, is not the first representative of the U.S. intelligence apparatus, or even the foreign policy-making establishment of the country as a whole, to advocate for incorporating economics into the conduct of U.S. foreign relations.

Richard Bissell, Max Milliken, and Walt Rostow share a number of similarities; all three, born in the beginning of the twentieth century, graduated from Yale University, became economics professors at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and later worked as researchers at a number of the same think tanks. More remarkably, all three of these men wandered from academia and into influential roles in the foreign policy-making establishment of the U.S. government during the early Cold War. Between them, these former economists developed strong ties to the Central Intelligence Agency, the State Department, and the White House during the formative years of the United States’ as a global hegemon.

This commonality opens a number of interesting questions. What motivated their decisions to become economists and then to transition from academics to Cold Warriors? Was their overlap coincidental or does some common thread or societal trend connect their journeys? And, most important and relevant to questions at hand today, what role did these social scientists see for economic theory and analysis in the planning and practice of foreign policy? I plan to explore how world events shaped the career decisions and ideologies of these men, and, in turn, what effect their ideas and contributions had on the development of U.S. foreign policy.

I expect to mainly explore their ideas on economic intelligence, especially with regard to Milliken and Bissell, who both spent significant periods in the CIA, and modernization theory, for which both Rostow and Milliken served as strong advocates to the White House and State Department. With current debates in the U.S. on rebuilding our economic intelligence capacities, correctly using foreign aid, and coping with the current financial crises, the insights gleaned from these former scholars and Cold Warriors could shed light on contemporary issues.

As sources for my investigation, I plan on utilizing the papers of Max Milliken and Walt Rostow, which are both available at the John F. Kennedy Library. Bissell’s memoir and several oral interviews in which he participated are also publicly available. Furthermore, several working papers, which these men produced as officials of the U.S. government and as researchers at numerous think tanks, are known to exist. And, finally, I plan to utilize the rich existing scholarship on modernization theory and its role in U.S. foreign policy.

Bibliography

Central Intelligence Agency On-line Library. Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room. Personal Papers of Max Millikan (1913-1969), John F. Kennedy Library. Walt W. Rostow (#8.24), John F. Kennedy Library. Wilson, Theodore A. and Richard D. McKinzie. “Oral History Interview with Richard M. Bissell, Jr.” Harry S. Truman Library. Works by all three at various think tanks, including one collaboration between Bissell and Milliken at the Center for International Studies (CENIS). Bissell, Jr., Richard M. Reflections of a Cold Warrior: From Yalta to the Bay of Pigs. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996. Fialka, John J. War by Other Means: Economic Espionage in America. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1999. Latham, Michael. Modernization as Ideology. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000. Light, Jennifer S. From Warfare to Welfare. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. Pearce, Kimber Charles. Rostow, Kennedy, and the Rhetoric of Foreign Aid. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2001.

Media Reflections of Western Public Opinion in the Suez Crisis

In the years following the Second World War, the global balance of power shifted significantly; following conflict amongst the traditional Great Powers, a bipolar power struggle emerged between the United States and the Soviet Union. The military and financial costs of the Second World War made it extremely difficult for European powers to hold their colonial empires, the loss of which compounded their economic downfall and ensured their decline as world powers. These material conditions were certainly a major factor in determining the new balance of power, as was the relative strength of the U.S.’s economic position, but less quantifiable factors were also importantly at play, namely the ability of each of the new and old powers to reconceptualize its role in the world and adapt its attitudes toward other nations accordingly. As decolonization occurred and Cold War conflicts began to arise across the globe, the Cold War powers and the traditional Great Powers were facing novel foreign policy challenges, mostly in the vein of trying to establish influence overseas when using force to do so was no longer feasible or morally acceptable. Thus each nation contending for global influence was forced to reassess its identity as a player on the world stage. Government officials developing policy carried out this reassessment as a conscious process, but it also occurred spontaneously within national populations responding to the obvious shifts in global power dynamics, begging the question: how well did government reconceptions of identity reflect public attitudes in the early Cold War era? The emergence of many new nations and nationalisms in the postwar world created ample cases which exemplify how modern national self-perceptions developed on different levels and how that led to the consolidation of a new world order. My thesis will focus on the 1956 Suez Crisis, due to its location in the strategically important and materially rich Middle East, which resulted in the involvement of many countries, and within that conflict, on the Western powers involved, for whom government was supposedly representative- England, France, and the United States.

Despite historiographical debates about precipitating and intermediate causes, the Suez Crisis of 1956 can be traced at least in part to the joint U.S.-British decision to discontinue their planned funding for the Egyptian government’s Aswan High Dam project, leaving the Egyptians in need of ready money, which served to justify Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal. The proposed Aswan High Dam project was exemplary of the new state of relations between Egypt and the western powers following the Egyptian Revolution of 1952. The new Egyptian leadership was anti-colonial, but not opposed to productive relations with the Western world. Thus, it hoped cooperative projects like the construction of the Aswan High Dam could usher in a new type of relationship between Egypt and the West. For Britain, this would mean relations based on voluntary economic cooperation rather than exploitation by force, while for the U.S. the change of policy consisted not in promoting an anti-colonial position but in doing so quite actively, as opposed to its former stance of relative isolationism. Britain and the U.S. tried to advance anti-colonial economic relations as per Egyptian requirements in order to maintain and create, respectively, a presence in the region, which was important in order to protect financial interests in the Middle East that were highly dependent on access to the Suez Canal, and to keep the Soviets from establishing rival influence there.

However, when the U.S. and Britain ultimately deemed the Aswan High Dam project inopportune and Nasser nationalized the canal in the summer of 1956, the ensuing Suez Crisis featured the British, influenced by the French, playing a traditional colonial imperialist role, while the U.S. took on a novel modern role, acting as an international arbitrator in pursuit of its own Cold War related interests. That Britain aligned with France rather than U.S. during the Suez Crisis is not entirely surprising given each nation’s recent history in international relations; careful study has reflected the extent to which French and British politicians were misguided in their political calculations by thought processes that were still largely driven by outmoded colonial considerations. There is also debate about the extent to which they based their policies on false assumptions about the U.S. position. The leaders involved in the Suez Crisis based their decisions about how best to serve their material interests without losing political capital not only on analysis of other nations’ official positions but also on their reading of public opinion at the time. No Western government wanted to act against national will and lose popularity with its constituents over Suez. It is therefore natural to wonder to what degree the western leadership’s gauge of popular thought was skewed by historicism, or conversely, how closely public attitudes in Britain, France, and the U.S. towards the developing crisis in the Middle East actually tended to match official ones in judging what action each nation should take.

For my thesis, I would like to examine this question: to what extent were policy-influencing perceptions of public opinion about the Suez Crisis in Britain, France, and the U.S. accurate? To fill out the high command side of the picture I would use mostly secondary sources, and when necessary the primary documents they are based upon (such as sources available in the U.S. National Archives, British Public Records Office, and French Foreign Ministry Archives), focusing my original research on French, British, and U.S. newspaper and perhaps radio coverage as indicative of trends within the field of public opinion in each country. To manage the scope of this study, I intend to concentrate on the two most publicly controversial time periods within the months of the Suez Crisis, the week after the canal was nationalized on July 26, 1956 (up to and including August 2) and the week after Israel invaded Egypt on October 29, 1956 (up to and including November 6). By analyzing the straight news coverage of, and the range of editorial responses to, the decision taken by Nasser to nationalize the canal, the decision of Israel to invade Sinai, and the subsequent statements and actions taken by France, Britain, and the U.S., I hope to determine the tenor of each national discourse about the crisis, and to place all three within a comparative framework in order to determine the relative degree to which elite and mass perceptions corresponded over the appropriate role for each Western power to play in Suez. The degree to which the press (on a national and local level, across the full spectrum of political stances), condoned and encouraged official decisions taken during the Suez Crisis will hopefully illuminate how well the political development of the crisis matched mainstream contemporary attitudes not merely about the situation, but about where the world powers now stood as arbiters of international relations and, thereby, how far long-serving leaders with deeply rooted beliefs about the role of their nations in the world were able to conform to the demands of a world in which the ideological as well as material environment had recently undergone major changes.

Preliminary Reading List :

Relevant Primary Sources to be located through:

The Times online archives, at http://archive.timesonline.co.uk/tol/archive/ British Library Integrated Catalogue: Newspapers, at http://catalogue.bl.uk ProQuest Historical Newspapers (US) including The New York Times, at http://proquest.umi.com French sources through Gallica, the French National Library’s Digital Browser, at http://gallica.bnf.fr/?&lang=FR

Azar, Edward E. “Conflict Escalation and Conflict Reduction in an International Crisis: Suez, 1956.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 16 (1972): 183-201. Cockett, R. “The Observer and the Suez Crisis.” Contemporary British History 5, no.1 (Summer 1991): 9-31. Gorst, Anthony, and Lewis Johnman. The Suez Crisis. London: Routledge, 1997. Louis, Wm. Roger, and Roger Owen. Suez 1956: The Crisis and its Consequences. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989. Lucas, W. Scott. Divided We Stand: Britain, the United States and the Suez Crisis. Sevenoaks: Hodder and Stoughton, 1991. Negrine, Ralph. “The Press and the Suez Crisis: A Myth Re-Examined.” Historical Journal 25, no. 4 (1982): 975-983. Oneal, John R., Brad Lian, and James H. Joyner, Jr. “Are the American People ‘Pretty Prudent’? Public Responses to U.S. Uses of Force, 1950-1988.” International Studies Quarterly 40, no. 2 (Jun., 1996): 261-279. Owen, Jean. “The Polls and Newspaper Appraisal of the Suez Crisis.” Public Opinion Quarterly 21 (1957): 350-354. Parmentier, Guillaume. “The British Press in the Suez Crisis.” Historical Journal 23, no. 2 (1980): 435-448. Rawnsley, G. D. “Cold War Radio in Crisis: the BBC Overseas Services, the Suez Crisis and the 1956 Hungarian Uprising.” Historical Journal of Radio and Television 16, no.2 (Jun., 1996): 197-219. ______. “Overt and Covert: The Voice of Britain and Black Radio Broadcasting in the Suez crisis, 1956.” Intelligence and National Security 11, no. 3 (July, 1996): 497-522. Shaw, Tony. Eden, Suez and the Mass Media: Propaganda and Persuasion During the Suez Crisis. London: Tauris, 1996.

The Implications, Effects, and Uses of Media in the Emmett Till Lynching

I propose to write an Honors Thesis in History during the xxxx academic year. After researching topics that interest me and consulting with Professor xxxx, I have developed a project that analyzes the uses and effects of media during the Civil Rights Movement. More specifically, my project will investigate how children, and the American media’s depiction of them, greatly impacted the American consciousness of the Civil Rights Movement. Children were a part of some of the most widely televised and reported Civil Rights events such as the lynching of Emmett Till, the use of water cannons and police dogs on children, the deaths of four black girls in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, the desegregation of Central High School, and the Selma marches where children were trampled by police horses.

Taking on a project with all these events would be beyond the scope of a senior thesis, so Professor Long and I have narrowed our focus to the lynching of Emmett Till in 1955. To briefly summarize this event, after allegedly whistling at a white woman, fourteen year old Emmett Till was shot and his body thrown in the Tallahatchie River in Mississippi by a group of white men. Emmett’s great-uncle identified two of these men, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, as those who had forced Emmett into their car the night he was killed. The trial lasted a mere five days, and the all-white jury acquitted both men of Emmett’s death in about an hour.

Media coverage served very important roles in Emmett Till’s death. In The Chicago Defender, Emmett’s hometown newspaper, the first articles on Emmett Till include pictures of his inconsolable mother being held upright by family members in front of Emmett’s casket. The newspaper articles focusing on Emmett also refer to the recent lynchings of black voting rights activists and the recent Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case. In effect, these articles attached a name, face, and picture to individuals affected by racist violence in the South while incorporating and increasing the visibility of large-scale race issues. Television crews broadcast Emmett’s mutilated face at his open-casket funeral, sparking outrage and horror throughout the country. Viewing these images in white America’s living room made the Jim Crow South more visible across white America. Media coverage of Emmett’s death further motivated black America to take a stand against white supremacy, all the more so after both white men confessed to Emmett’s murder in Look Magazine. This event raises myriad questions regarding race relations in the South, but I want to focus my efforts on a few that interest me most. I want to explore the reasons, implications, and effects of Emmett’s mother’s decision to display Emmett’s mutilated and decomposed face at his open-casket funeral. This investigation leads to the history, reasons, and importance of open-casket funerals in the African-American community. My project will also analyze the response of the white community in the immediate area where Emmett was murdered. His murder has been well documented in television coverage, newspaper articles, and magazine interviews; however, very little research has examined the media’s impact on the regional, national, and international levels. I want to examine how these communities responded to Emmett’s death and how the white South was viewed as a result of different reactions according to race and location.

Furthermore, Emmett Till’s murder raises questions regarding white masculinity and femininity and their relationship to black masculinity. Another aspect to this project may include how the image of Emmett Till has been remembered and reconstructed by the media more recently in the form of television series and movies. I seek to investigate these issues primarily through primary sources such as photographs, television coverage, newspaper articles, and interviews of individuals. Secondary resources, particularly in the field of media studies will be helpful to my project. Overall, my project will become part of a greater dialogue that explores the media’s perception of the white response to black life and culture in the Jim Crow South.

Since the summer after my sophomore year at Williams, I have laid the foundation for this project. My independent research through the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship has allowed me to develop my research skills, work closely with a professor, and read over a dozen seminal primary and secondary sources in the field of race relations in the United States. I have already written two research papers, (with a third on the way) about these books.

I am interested in writing an Honors Thesis in History for many reasons. Most importantly, I want the opportunity to immerse myself in a subject that greatly interests me while contributing to a larger body of academic work in the field. Writing a thesis is also important because it will allow me to dedicate an extended period of time to a very specific subject. I enjoy historical research and want the satisfaction of knowing that I thoroughly understand the intricacies and nuances of a particular topic, even though it may be a small fraction of a larger whole. Additionally, I want to complete a large historical project to show history graduate schools of my seriousness in pursuing a Ph.D. in American History.

Cromwell Lives while Mason Stalks: Irish Nationalism and Historical Memory during the Troubles

In my proposed thesis I want to ask how significant perceptions of Irish history were in perpetuating the Troubles. Often, the pieces of history that get retold vindicate the present. I believe that perceptions of Irish history are significant in perpetuating the conflict in Northern Ireland because both Unionists and Nationalists created their own versions of history which they use to give legitimacy to their political visions for the future. Within the communities, different interest groups manipulate and re-manipulate history and each separate reading of the past justifies the present actions of its perpetuators. In this sense, the issue of history is an issue of legitimacy, and legitimacy is directly linked to political power. In their book The Northern Ireland Conflict: Consociational Engagements, John McGarry and Brendan O’Leary write that Northern Ireland is “a site of competing analogies and norms. Neither of its communities… have been able to achieve hegemonic legitimacy. This is one reason why the conflict continues.” It’s a trope that history is written by the winners, and in Northern Ireland, both sides are trying to write themselves as winners. Far from just an intellectual debate, the separate readings of history are crafted to justify political action, perpetuating the conflict.

Partition is a classic example of how Unionists and Nationalists use history to justify their current political positions. The Unionists perception of history accentuates the continuity of partition as a social force. Historian A.T.Q. Stewart uses the election of 1886 to emphasize the innate nature of partition. In it, seventeen out of thirty-three Ulster members of parliament elected were for Home Rule. That emphasized to Protestants that they were characteristically different from the rest of the inhabitants of Ireland. Stewart writes, “from 1886 to 1920, Ulster Protestants were a minority under threat.” By stressing the deep, cultural roots of partition, Stewart justifies it as a logical action and just solution that was a long time coming.

In contrast, the general Nationalist reading of the same period of history frames partition as “the arbitrary division of the country”, to quote the New Ireland Forum Report. “In the period immediately after 1920,” the Report continues, “many saw partition as transitory.” Nationalists tend to blame British imperialism or other exogenous factors as the cause of the conflict. In this way, they are able to represent partition an illegitimate action imposed on Ireland. The emphasis on exogenous factors allows Nationalists to imply that partition is the problem. Generally, they argue that by removing it and restoring the territorial integrity of Ireland, the conflict would be solved.

Both Unionists and Nationalists construct elaborate historical myths that legitimate their claim to the territory of Northern Ireland. Andy Tyrie, the supreme commander of the Ulster Defense Association in the early 1980s, broke from the traditional Unionist position of supporting union with Great Britain and advocated for an independent Ulster in the early 1980s. He created historical justification for his position by arguing that the areas of Scotland where Ulster Protestants came from were originally colonized by tribesmen from Ulster in the early middle ages—so in a sense Ulster Protestants were just returning to their ancestral homeland when they re-colonized in the seventeenth century. “Many people are convinced that the Protestants arrived here in 1607,” he said. “But their ancestors arrived here long before that. The Ulster people have always been here.”

Tyrie’s myth about Ulster was designed to compete with the traditionally Republican version of history of centuries of Irish resistance to British imperial rule. The Nationalist myth, as summarized by Padraig O’Malley, begins with the invasion of Ireland by England 800 years ago. In it, O’Malley writes, “history is linear. Thus, Ireland was subdued by superior arms and resources, but not beaten; the struggle to re-establish a free and united Ireland was carried forward from generation to generation.” The H-Block Song, written for the Republican prisoners in the maze perpetuates this view of events. The song ends with the question, “Does Britain need a thousand years of protest, riot, death, and tears?” emphasizing the long history of Irish oppression at the hands of British invaders. Lines like “Black Cromwell lives while Mason stalks” create a sense of the historical continuity of the fight against British imperialism, linking Oliver Cromwell with Roy Mason, the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland when the H-Block song was written in 1976.

Both of these “ancestral tribe” myths are designed to support current claims to the island. Neither one is particularly valid historically, but the point is not historical accuracy. These myths are designed to create legitimacy for current political claims. Thus, history has become a tool allowing each side to perpetuate and justify their view of the conflict.

In my proposed thesis I’d ask the significance of perceptions of Irish history in perpetuating the Troubles. Much of the scholarship that I’ve read concentrates on specific historical occurrences and doesn’t directly investigate Irish historiography, or the link between historical memory and political action. I’d begin with a definition and explanation of the Nationalist myth of unbroken struggle. I’d draw on the writings of Irish Nationalists such as Padraig Pearse, as well as later scholarship by historians such as Padraig O’Malley. I’d also study how this historical myth has been created and perpetuated both inside Ireland and also abroad. On the international front, I’d specifically focus on how Irish Nationalists draw historical analogies to oppressed-native minority/settler-oppressor conflicts such as comparing their situation to the struggle over apartheid in South Africa. I’d study memoirs and interviews, like Adrian Kerr’s book Perceptions: Cultures in Conflict, and scholarship, such as Adrian Guelke’s book on comparative politics, Northern Ireland: An International Perspective. I’d also draw on art and propaganda: music, street murals, accounts of parades, 1916 commemoration posters issued by Sinn Fein and other Republican groups, and films, such as the 1980 documentary The Patriot Game, which gives a Nationalist account of the Troubles.

The well-established historical myth of Nationalist struggle presupposes an almost inevitable pattern to history: “Ireland unfree will never be at peace.” Therefore, I’d next investigate how the Nationalist reading of Irish history has affected political events during the Troubles. I’d focus on two important historical occurrences, the 1974 Ulster Worker’s Council strike that brought down the Sunningdale power-sharing agreement and the 1981 Republican hunger strikes. According to the strike bulletins, the main reason the UWC wanted to stop Sunningdale was because of the provisions it made to involve the Irish Free State in Northern Ireland’s affairs, which it characterizes as “the main danger.” I’d investigate if this anti-Irish attitude was affected by the striker’s perceptions of Ulster history and the North’s relationship to the South.

With the hunger strikes, I’d research the connection between the strikers’ experiences and Irish history. I’d specifically ask if the hunger strikers appealed to historically Irish motifs of martyrdom in an attempt to gain political legitimacy for the Provisional IRA. My hunch is that the Nationalist movement consciously used history as a practical tool in order to get political status for their prisoners, but it would take further research to figure this out. Not Meekly Serve My Time, the remembrances of Republican H-Block prisoners and hunger strikers would be invaluable, as would the diaries of Bobby Sands and the writings of Gerry Adams, as well as the memoirs of SDLP party leader John Hume.

Through these two specific incidents, I’d study how perceptions of Irish history affected the politics of Northern Ireland during the 1970s and early 1980s and also investigate how Nationalists and Unionists used interpretations of history to generate political legitimacy.

Adams, Gerry. Selected Writings. Kerry: Brandon, 1994. Bew, Paul and Patterson, Henry. The British State and the Ulster Crisis. New York: Verso, 185. Patrick Bishop and Eamonn Mallie. The Provisional IRA. Aylesbury: Corgi Books, 1989. Campbell, Brian, Laurence McKeown, and Felim O’Hagan, ed. Not Meekly Serve My Time: The H Block Struggle 1976-1981. Belfast: Beyond the Pale Publications, 1998. Farrell, Michael. Northern Ireland: The Orange State. London: Pluto Press Limited, 1976. Gallagher, AM. “Majority Minority Review 2: Employment, Unemployment and Religion in Northern Ireland.” CAIN Web Service, http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/csc/reports/mm210.htm. Guelke, Adrian. Northern Ireland: An International Perspective. New York : St. Martin’s Press, 1988. Hepburn, A.C., ed. The Conflict of Nationality in Modern Ireland. London: Edward Arnold Ltd., 1980. Hume, John. Personal views, Politics, Peace and Reconciliation in Ireland. Dublin: Town House, 1996 Kerr, Adrian, ed. Perceptions: Cultures in Conflict. Derry: Guildhall Press, 1996. McAllister, Ian. The Northern Ireland Social Democratic and Labor Party. London: Unwin Brothers Ltd., 1977. MacDonagh, Oliver. States of Mind. London: Pimlico, 1992. McGarry, John and Brendan O’Leary. Explaining Northern Ireland. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1995. ______. The Northern Ireland Conflict: Consociational Engagements. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. Mulchaly, Aogan. “Claims-Making and the Construction of Legitimacy: Press Coverage of the 1981 Hunger Strikes.” Social Problems 42, No. 4 (Nov. 1995): 467-499. “The New Ireland Forum Report,” CAIN Web Service, http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/ issues/politics/nifr.htm. O’Malley, Padriag. Biting at the Grave. Belfast: Blackstaff Press, 1990. ______. The Uncivil Wars. Belfast: Blackstaff Press, 1983. O’Neill, Terence. Ulster at the Crossroads. Faber and Faber: London, 1969. Rose, Richard. Governing without Consensus. London: Faber and Faber, 1971. Sands, Bobby. Writings from Prison. Cork: Mercier Press, 1998. Stewart, A.T.Q. The Narrow Ground: The Roots of the Conflict in Ulster. London: Faber and Faber, 1997. “Strike Bulletins of the Ulster Worker’s Council Strike, No 1.” CAIN Web Service. http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/uwc/uwc-pdfs/one.pdf. Sweeney, George. “Irish Hunger Strikes and the Cult of Self-Sacrifice.” Journal of Contemporary History 28, No. 3 (Jul. 1993): 421-437. Wichert, Sabine. Northern Ireland Since 1945. London: Longman, 1999.

‘My broken dreams of peace and socialism’: Youth propaganda, personality, and selfhood in the GDR, 1979-1989.

“I was a young citizen in a young nation, and it was my duty to advance the cause of socialism,” writes Jana Hensel in her memoir of childhood during East Germany’s final decade of socialism. The molding of youth and children like Hensel into healthy “socialist personalities” desirous of political stability and unity had been the object of the Socialist Unity Party’s (SED) most ardent ideological efforts ever since the foundation of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in 1949. By the 1980’s, however, when the GDR could no longer rely on brute force to secure the loyalty of its subjects, the very survival of the Communist East German regime had come to depend on the success of the socialist mentality building project. To urge the new generations of East Germans to develop personal qualities essential for the advancement of socialism, the SED mobilized all of its resources: the school system, youth organizations, mass events, and leisure time activities. Unlike the youth of the 1960’s, however, “Honecker’s children” turned out to be much more concerned with personal matters than with the fulfillment of their social and political obligations. Moreover, with the assimilation of new psychological models and concepts of individuality throughout the 1980’s, the anachronism and absurdity of SED’s personality building project became increasingly apparent.

In my Honors thesis, I plan to examine the manifold ways in which the ideological prescriptions disseminated by the SED during the 1980’s actually shaped the lived experience and affected the sense of selfhood of young members of East German society. I also wish to reflect on the lasting effects of GDR’s preoccupation with character building on the sense of identity of “Honecker’s children” twenty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. My work thus aims to complement current historical literature on the politics of the GDR’s youth project with a thorough investigation of the cultural, psychological, and sociological aspects of socialist character building in the GDR. To this end, I plan to relate my investigation of the ways in which the youth responded to new ideas about the socialist East German self to sociological and anthropological works on identity and selfhood, as well as to psychological theory on childhood and memory. By examining the ideas about selfhood lying at the very heart of East German youth policies and focusing on the ways in which the youth understood them and responded to them, I hope to challenge current understandings of the overarching roles of culture and ideology in postwar German history.