Theseus and Aethra by Laurent de La Hyre (ca. 1635–1636)

Theseus—son of Aegeus (or Poseidon) and Aethra—was by far the most important of the mythical heroes and kings of Athens. His heroic accomplishments included killing the Minotaur, though he was also remembered as a political innovator who transformed his city into a major regional power.

Theseus was raised by his mother in Troezen but moved to Athens upon reaching adulthood. He traveled widely and performed many heroic exploits, eventually sailing to Crete to kill the Minotaur.

As king of Athens, Theseus greatly improved the government and expanded the power of his city. He was sometimes seen as the mythical predecessor of the political unification of Attica.

Who were Theseus’ parents?

Theseus was the product of an affair between Aegeus, the king of Athens, and Aethra, a princess of Troezen. But in some traditions, the sea god Poseidon slept with Aethra the same night as Aegeus, making Theseus his son instead.

Theseus was raised by his mother Aethra in Troezen. The identity of his father was kept secret until Theseus had proven himself worthy of his inheritance.

Whom did Theseus marry?

Theseus had a weakness for women and was not always loyal to them. He eventually married Phaedra, a princess from Crete. Their marriage ended disastrously, however, when Phaedra fell passionately in love with Hippolytus, Theseus’ son by another consort.

Aside from Phaedra, Theseus had many lovers throughout his storied career. These included Phaedra’s own sister Ariadne; an Amazon queen named either Antiope or Hippolyta; and even the famous Helen, according to some traditions.

Ariadne by Asher Brown Durand, after John Vanderlyn (ca. 1831–1835)

How did Theseus die?

Like many Greek heroes, Theseus did not die happily. In the common tradition, he was exiled from Athens after his recklessness turned the city and its nobility against him. He traveled to the small island of Scyros, where he fell to his death from a cliff (or was thrown from the cliff by the local king).

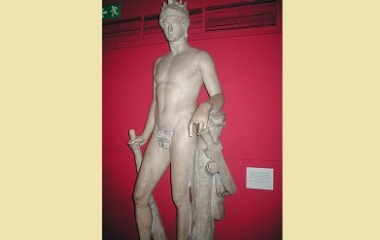

Roman fresco of Theseus from Herculaneum (ca. 45–79 CE)

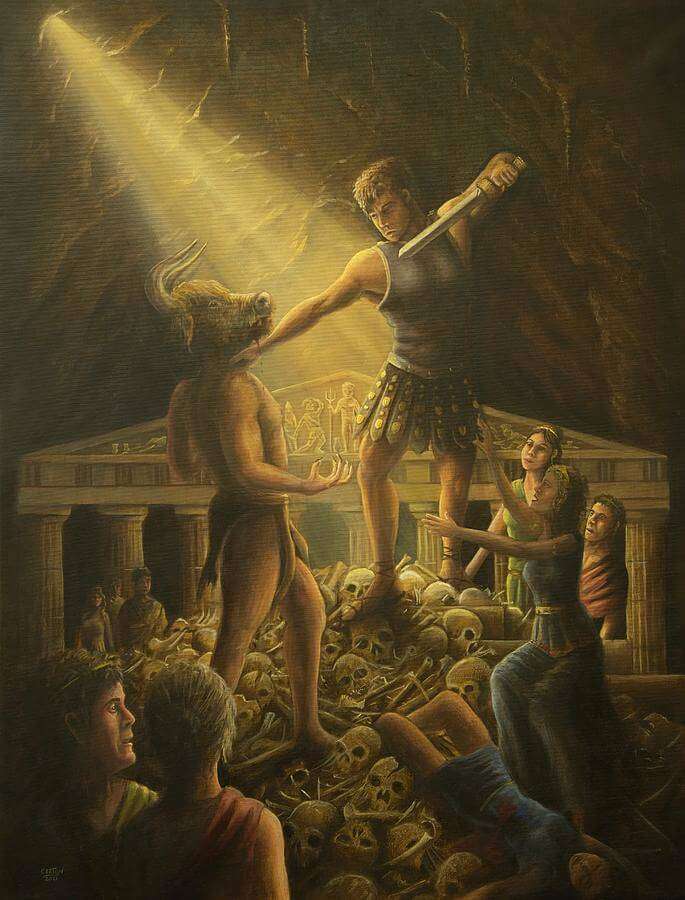

Theseus Slays the Minotaur

Shortly after meeting his father Aegeus in Athens, Theseus voyaged to the island of Crete as one of the fourteen “tributes” sent annually as a sacrifice to the Minotaur—a half-man, half-bull hybrid imprisoned in the Labyrinth. Theseus vowed to kill the Minotaur and end the bloody custom once and for all.

In Crete, Theseus’ good looks won him the love of Ariadne, the daughter of the king. Ariadne helped Theseus on his mission by giving him a ball of thread that he unraveled as he made his way through the maze-like Labyrinth. After finding and killing the Minotaur, Theseus re-wound the thread to safely escape.

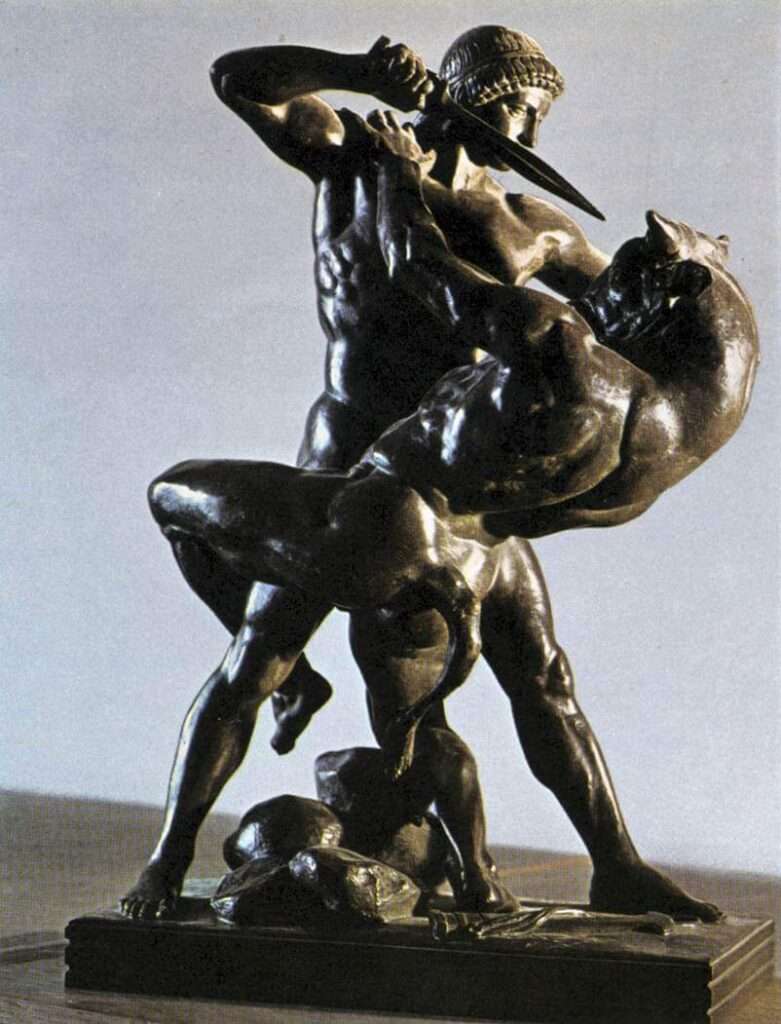

Theseus Slaying the Minotaur by Antoine-Louis Barye (1843)

The name Theseus was likely derived from the Greek word θεσμός ( thesmos ), which means “institution.” Theseus’ name thus reflects his mythical role as a founder or reformer of the Athenian government.

Pronunciation

In his iconography, Theseus is usually depicted as a handsome, strong, and beardless young hero. Theseus’ battle with the half-bull Minotaur was an especially popular theme in Greek art.

Theseus’ father was either Poseidon , the god of the sea, or Aegeus, the king of Athens. His mother was Aethra, the daughter of King Pittheus of Troezen.

Family Tree

Theseus was the son of Aethra, the daughter of King Pittheus of Troezen, and either Aegeus or Poseidon. Aegeus, who was the king of Athens, had no children and therefore no heir to his throne. Hoping to remedy this, Aegeus went to Delphi, where he received a strange prophecy:

The bulging mouth of the wineskin, O best of men, loose not until thou hast reached the height of Athens. [1]

On his way back to Athens, Aegeus stopped at Troezen, where he was entertained by King Pittheus. Aegeus revealed the prophecy to Pittheus, who understood its meaning and plied Aegeus with wine. Aegeus then slept with Pittheus’ daughter Aethra.

Before leaving Troezen, Aegeus hid a sword and sandals under a large stone. He told Aethra that if she had a son, she should wait until he had grown up and bring him to the stone. If he managed to lift it and retrieve the tokens, he should be sent to Athens.

According to other versions, Aethra had also been seduced by the god Poseidon, and it was he who was Theseus’ father. [2] In any case, Theseus grew up to be a strong and intelligent young man. When he had come of age, his mother took him to the stone where Aegeus had long ago deposited his sword and sandals. Theseus successfully retrieved these tokens and left for Athens to find his father.

Journey to Athens

Instead of travelling to Athens by sea, Theseus decided to make a name for himself by taking the more dangerous overland route through the Greek Isthmus. At the time, it was plagued by bandits and monsters. On his way to Athens, Theseus cleared the Isthmus in what are sometimes called the “Six Labors of Theseus”:

At Epidaurus, Theseus met Periphetes, famous for slaughtering travellers with a giant club. Theseus killed Periphetes and claimed the club for himself.

Theseus then met Sinis, who would bend two pine trees to the ground, tie a traveller between the bent trees, and then let the trees go, thus tearing apart the traveller’s limbs. Theseus killed Sinis using this same method. He then seduced Sinis’ daughter Perigone, who later gave birth to a son named Melanippus.

Theseus next killed the monstrous Crommyonian Sow (sometimes called Phaea), [3] an enormous pig that terrorized travellers.

Near Megara, Theseus met the robber Sciron, who would throw his victims off a cliff. Theseus, as usual, used his opponent’s method against him and threw Sciron off a cliff.

At Eleusis, Theseus fought Cerycon , who challenged travellers to a wrestling match and killed whomever he defeated. Following this model, Theseus wrestled Cerycon, beat him, and killed him.

Finally, Theseus defeated Procrustes (sometimes called Damastes), who had two beds that he would offer to travellers. If the traveller was too tall to fit in the bed, Procrustes would cut off their limbs; if they were too short, he would stretch them until they fit. Theseus killed Procrustes by putting him on one of his beds, cutting off his legs, and then decapitating him.

Arrival at Athens

After clearing the Isthmus, Theseus finally arrived at Athens. He did not, however, reveal himself to his father Aegeus immediately. Aegeus became suspicious of the stranger and consulted Medea , whom he had married after sleeping with Aethra.

Medea realized that Theseus was the son of Aegeus, but she did not want Aegeus to recognize him. She was afraid he would choose Theseus as his heir over her own son. Medea therefore tried to trick her husband into killing Theseus.

In some stories, Medea convinced Aegeus to send Theseus to slay the monstrous Bull of Marathon, hoping that the bull would kill him first.

Painting in tondo of kylix showing Theseus fighting the Bull of Marathon by unknown artist (c. 440–430 BC).

In other stories, Medea tried to poison Theseus. But Aegeus recognized Theseus by the sword he was carrying (the sword he had left with Aethra at Troezen) and stopped him from drinking the poison. Medea fled into exile.

Medea was not the only threat to Theseus’ standing in Athens. The sons of Aegeus’ brother Pallas (often called the Pallantides) had hoped to inherit the throne if their uncle Aegeus died childless. According to some sources, the sons of Pallas ambushed or rebelled against Theseus and Aegeus. This attempt failed, however, and after Theseus killed the sons of Pallas he was secured as the heir to the throne of Athens. [4]

The Minotaur

During Aegeus’ reign, the Athenians were forced to send a regular tribute of fourteen youths (seven boys and seven girls) to Minos , the king of the island of Crete. This was reparation for the murder of Minos’ son Androgeus in Athens several years before.

When the fourteen tributes reached Crete, they were fed to the Minotaur, a terrible bull-man hybrid born from an affair between a divine bull and Minos’ wife Pasiphae:

A mingled form and hybrid birth of monstrous shape, ... Two different natures, man and bull, were joined in him. [5]

The Minotaur was imprisoned in the Labyrinth, a giant maze built by the Athenian architect Daedalus. None of the tributes who were sent into the Labyrinth ever made it out.

Soon after his arrival in Athens, Theseus sailed off as one of the fourteen tributes dedicated to the Minotaur. According to some traditions, Theseus actually volunteered to go to Crete, vowing that he would kill the Minotaur and bring an end to the terrible tribute once and for all. [6]

The ship on which he and the other tributes embarked had a black sail; before the ship left for Crete, Aegeus made Theseus swear that if he managed to return alive he would have the black sail changed to a white one.

At Crete, Minos’ daughter Ariadne fell in love with Theseus and agreed to help him kill the Minotaur if he would take her with him to Athens. Before Theseus entered the Labyrinth, Ariadne gave him a ball of thread. Theseus unravelled the thread as he moved through the Labyrinth, killed the Minotaur, and found his way out of the Labyrinth by following the thread back to the exit. Theseus and Ariadne then escaped from Crete with the other tributes.

Detail of the Aison cup showing Theseus slaying the Minotaur in the presence of Athena (c. 435–415 BC).

On their journey back to Athens, Theseus stopped at the island of Naxos. There are different versions of what happened to Ariadne there. According to some, Theseus simply abandoned her. Another well-known story, however, claims that Dionysus fell in love with Ariadne while she was on Crete and carried her off for himself. In any case, Theseus arrived at Athens without Ariadne. [7]

Ariadne weeps as Theseus' ship leaves her on the island of Naxos. Roman fresco from Pompeii at Naples Archaeological Museum.

Whether distracted by the loss of Ariadne or for some other reason, Theseus forgot to raise the white flag as he came back to Athens. Aegeus, who was watching from a tower, saw the black flag and thought that his son had died.

Overcome by grief, Aegeus killed himself by leaping into the sea (this is the origin, according to the Greeks, of the name of the “Aegean Sea”). Theseus arrived to find his father dead and so became king of Athens.

The Amazons

Like many heroes of Greek mythology, Theseus waged war with the Amazons . The Amazons were a fierce race of warrior women who lived near the Black Sea or the Caucasus. Their queens were said to be the daughters of the war god Ares .

While among the Amazons, Theseus fell in love with their queen, Antiope (sometimes called Hippolyta), [8] and carried her off with him to Athens. The Amazons then attacked Athens in an attempt to get Antiope back. In some versions of the myth, the Amazons laid waste to the countryside of Attica and only left after Antiope was accidentally killed in battle. [9]

In other versions, Theseus tried to abandon Antiope so that he could marry Phaedra, a princess from Crete; when the jilted Antiope tried to stop the wedding, Theseus killed her himself. [10] In all versions of the story, however, Theseus finally managed to drive the Amazons away from Athens after the death of Antiope, though only after Antiope had given him a son named Hippolytus.

After the death of Antiope, Theseus married Phaedra, the daughter of the Cretan king Minos and thus the sister of his former lover Ariadne. Phaedra bore Theseus two children, Acamas and Demophon .

Roman mosaic of Phaedra and Hippolytus at House of Dionysus, Cyprus (ca. 3rd century CE).

Eventually, however, Phaedra fell in love with Hippolytus, the son of Theseus’ first wife, Antiope. Phaedra tried to convince Hippolytus to sleep with her. When he refused, Phaedra tore her clothing and falsely claimed that Hippolytus had raped her. Theseus was furious and prayed to Poseidon that Hippolytus might be punished.

Poseidon, unfortunately, heard Theseus’ prayer and sent a bull from the sea to charge Hippolytus as he was riding his chariot near the coast. Hippolytus’ horses were frightened; he lost control of the chariot, became entangled in the reins, and was trampled to death.

Theseus discovered his son’s innocence too late; Phaedra, ashamed and guilty, hanged herself. [11]

Abduction of Helen and Persephone

Theseus took part in several other adventures. Some sources include him among the Argonauts who sailed with Jason to retrieve the Golden Fleece, or with the heroes who took part in the Calydonian Boar Hunt.

In many of these adventures, Theseus was accompanied by his best friend Pirithous , the king of the Lapiths of northern Greece. In one famous tradition, Theseus and Pirithous both vowed to marry daughters of Zeus. Theseus chose Helen, and Pirithous helped him abduct her from her father Tyndareus’ home in Sparta.

Pirithous then chose Persephone as his bride, even though she was already married to Hades . Theseus left Helen in the care of his mother, Aethra, while he and Pirithous went to the Underworld to abduct Persephone. Predictably, this did not end well. Theseus and Pirithous were caught trying to abduct Persephone and trapped in the Underworld.

While Theseus was away from Athens, Helen’s brothers, Castor and Polydeuces , retrieved her and took Aethra prisoner. Meanwhile, Theseus was eventually rescued from Hades by Heracles, but Pirithous remained trapped in eternal punishment for his impiety (in the most common version of the story). [12] When Theseus returned to Athens, he found that Helen was gone and that his mother had become her slave in Sparta.

Athenian Government and Death

Theseus was said to have been responsible for the synoikismos (“dwelling-together”), the political and cultural unification of the region of Attica under the rule of the city-state of Athens. In later times, some Athenians even traced the origins of democratic government to Theseus’ rule, even though Theseus was a king. Theseus was always seen as an important founding figure of Athenian history.

As an old man, Theseus fell out of favor in Athens. Driven into exile, he came to Scyrus, a small island in the Aegean Sea. It was in Scyrus that Theseus died. In some stories, he was thrown from a cliff by Lycomedes, the king of Scyrus. In 475 BCE, the Athenians claimed to have identified the remains of Theseus on Scyrus and brought them back to be reinterred in Athens.

Festivals and/or Holidays

The festival of Theseus, called the Theseia, was celebrated in Athens in the autumn. It was presided over by the Phytalidae, the hereditary priests of Theseus. The Phytalidae were said to have been the direct descendants of the fourteen tributes Theseus saved when he killed the Minotaur. [13] Little else is known of the festivals or worship of Theseus.

The hero-cult of Theseus was almost certainly concentrated solely in the city of Athens. The main sanctuary of Theseus, the Theseion, may have existed as early as the sixth century BCE. [14] It was most likely located at the center of Athens, in the vicinity of the Agora. Though the Theseion was probably the main center of Theseus’ hero-worship, little else is known about it, and there is still virtually no archaeological evidence of it. There were likely other sanctuaries of Theseus in Athens by the fourth century BCE.

Pop Culture

Theseus has had a rich afterlife in modern popular culture. The 2011 film Immortals is loosely based on the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur; Theseus is portrayed by Henry Cavill. Theseus also features in the miniseries Helen of Troy (2003), in which he kidnaps Helen with his friend Pirithous.

The myths of Theseus are also retold in many modern books and novels. Mary Renault’s critically acclaimed The King Must Die (1958) is a historicized retelling of Theseus’ early life and his battle with the Minotaur; its sequel, The Bull from the Sea (1962), deals with Theseus’ later career. The myth of Theseus and Antiope is also reimagined in Steven Pressfield’s novel Last of the Amazons (2002).

Jorge Luis Borges’ short story The House of Asterion (published in Spanish in 1947) presents an interesting variation on the myth of the Minotaur, told from the perspective of the Minotaur rather than Theseus. The myth of Theseus inspired Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games trilogy (2008–2010).

Greek Gods & Goddesses

Not many heroes are best known for their use of silk thread to escape a crisis, but it is true of Theseus. The Greek demi-god is known for feats of strength but is even better remembered for divine intelligence and wisdom. He had many great triumphs as a young man, but he died a king in exile filled with despair.

Theseus grew up with his mother, Aethra. She was the daughter of Pittheus, the king of Troezen. Theseus had two fathers. One father was Aegeus, King of Athens, who visited Troezen after consulting the Oracle at Delphi about finding an heir. He married Aethra then left her behind, telling her that if she had a child and if that child could move a boulder and retrieve the sword and sandals he had buried underneath, then she should send that child to Athens. Theseus’ other father was Poseidon , the god of the sea, who joined Aethra for a seaside walk on her wedding night.

When Theseus grew up, he easily picked up the large boulder and found his father’s items, so his mother gave him directions to Athens. Rather than take the safer sea route, he chose to take the land route even though he knew there would be multiple dangers ahead. Along the road he had to fight six battles. He defeated four bandits, one monster pig and one giant, winning every battle through strength and cunning.

When Theseus arrived at Athens, he did not reveal himself to his father. His father had married the sorceress Medea . She recognized Theseus and wanted to kill him. First, she sent him on a dangerous quest to capture the Marathonian bull. When he was successful, she gave him poisoned wine. Medea’s husband knew of her plan. However at the last moment, Aegeus saw Theseus had the sword and sandals he had buried and knocked the cup from his hand. Medea fled to Asia. Aegeus welcomed Theseus and named him as heir to the throne.

Battle with the Minotaur

Sometime later came Theseus’ greatest challenge. Every seven years King Minos of Crete forced Athens to send seven courageous young men and seven beautiful young women to sacrifice to the Minotaur , a half-man, half-bull creature that lived in a complicated maze under Minos’ castle. This tribute was to prevent Minos starting a war after Minos’ son, Androgens, was killed in Athens by unknown assassins during the games. Theseus volunteered to be one of the men, promising to kill the Minotaur and end the brutal tradition. Aegeus was heartbroken, but made Theseus promise to change the ship’s flags from black to white before he returned to show that he had succeeded.

When Theseus arrived in Crete, King Minos’ daughter Ariadne fell in love with him and promised to help him escape the labyrinth if he agreed to take her with him and marry her. He agreed. Ariadne brought him a ball of silk thread, a sword and instructions from the maze’s creator Daedalus – once in the maze go straight and down, never to the left or right.

Theseus and the Athenians entered the labyrinth and tied the end of the thread near the door, letting out the string as they walked. They continued straight until they found the sleeping Minotaur in the center. Theseus attacked and a terrible battle ensued until the Minotaur was killed. They then followed the thread back to the door and were able to board the ship with the waiting Ariadne before King Minos knew what had happened.

That night Theseus had a dream – likely sent by the god Dionysus – saying he had to leave Ariadne behind because Fate had another path for her. In the morning, Theseus left her weeping on the Island of Naxos and sailed to Athens. Heartbroken, perhaps cursed by Ariadne, Theseus forgot to change the ship’s flags from black to white.

His father, seeing the black flags on the approaching ship, assumed Theseus was dead . Aegeus threw himself off the cliffs and into the sea to his death. The sea east of Greece is still called the Aegean Sea.

Ariadne would later marry Dionysus.

King of Athens

Theseus became King of Athens after his father’s death. He led the people well and united the people around Athens. He is credited as a creator of democracy because he gave up some of his powers to the Assembly. He continued to have adventures.

During one of his adventures, he travelled to the Underworld with his friend Pirithous, who was pursuing Persephone . Both friends sat on rocks to rest and found that they could not move. Theseus remained there for many months until he was rescued by his cousin Heracles , who was in the Underworld on his 12th task. Pirithous had been led away by Furies in the meantime and was not rescued.

On another adventure with Heracles, he set out to rescue the Amazon Queen Hippolyta’s girdle. After the quest, Theseus married her and they had a son named Hippolytus. When Hippolytus was a young man, he caused a fit of jealousy between the goddesses Aphrodite and Artemis .

Aphrodite, the goddess of love, caused Phaedra, who was Theseus’ second wife and Ariadne’s younger sister, to fall in love with her stepson. Phaedra killed herself and left a note blaming Hippolytus’ bad treatment of her for her actions.

When Theseus saw the note, he called on his father Poseidon to take revenge on Hippolytus. A sea monster frightened the horses of Hippolytus’ chariot so that he was thrown from it, got tangled in the reins and dragged. Then Artemis let Theseus know he had been deceived and he ran to find his son, who died in his arms.

Due to his despair over losing his wife and his son, Theseus quickly lost popularity and the support of his people. He fled Athens for the Island of Skyros, where the king feared Theseus was plotting to overthrow him and pushed him off a cliff and into the sea to this death.

After His Death

Some ancient Greeks believed Theseus was a historical king of Athens. During the Persian Wars from 499 to 449 B.C., Greek soldiers reported seeing Theseus’ ghost on the battlefield and believed it helped lead them to victory. In 476 B.C., the Athenian Kimon is said to have found and returned Theseus’ bones to Athens and then built a shrine that also served as a sanctuary for the defenseless.

The ship Theseus used to sail to Crete was also believed to have been preserved in the city harbor until about 300 B.C. As wooden boards rotted they were replaced to keep the ship afloat. In time, people questioned whether any of the boards could have been from the original ship, which led to a question philosophers debate called the Ship of Theseus Paradox: “Is an object that has had all of its parts replaced still the original object?”

Quick Facts about Theseus

— Semigod ( demigod ) with two fathers, including the sea god Poseidon — Defeated the Minotaur — King of Athens credited with development of democracy — Lost his throne after the death of his wife and son — Aegean Sea is named for his human father — Frequently depicted in ancient and Romantic art — Experienced six tasks on his journey to Athens — Some believed him to be based on a historic kin

Link/cite this page

If you use any of the content on this page in your own work, please use the code below to cite this page as the source of the content.

Link will appear as Theseus: https://greekgodsandgoddesses.net - Greek Gods & Goddesses, February 11, 2017

- Greek Creatures

- Greek Concepts

- Norse Creatures

- Norse Concepts

- Egyptian Gods

- Egyptian Creatures

- Roman Creatures

- Japanese Gods

- Japanese Creatures

- Hindu Creatures

- Mythical Creatures

You May Also Like:

- Pronunciation: THEE-see-us

- Origin: Greek

- Town: Athens

- Mother: Aethra

- Symbols: Sandals and Sword

Who Is Theseus?

Theseus was a well-respected Greek hero. He was strong, courageous, and very wise. He worked hard to protect Athens and helped develop their power structure. He led the Athenian army on a number of battles, always returning victorious. He was known for helping the poor and less fortunate and also founded modern-day democracy.

Theseus became a voice of reasoning for the people. A popular Athenian saying, “Not without Theseus,” shows how he was respected by the people and not just for his bravery or strength, but also for his wisdom and ability to conquer any situation.

Legends and Stories

The myth of Theseus is long and detailed. It tells of his childhood, his travels to Athens, the discovery of his true father, and how he saved countless lives with his services.

The Travel to Athens

Theseus was born in Troezen. His mother, Aethra, was unsure of who his father was. King Aegeus was a possibility, and told Aethra that when the child became of age, he was to lift a rock and take the sword and sandals hidden beneath. After hiding the items, Aegeus headed back to Athens.

When Theseus was a young man, his mother took him to the rock. He was able to lift it easily. He took the sword and sandals and threw the large rock into the forest. Realizing that the King was his father, Aethra told Theseus he must go to Athens, where he would become heir to the throne.

It was common knowledge that the best way to travel was by boat, due to the high number of criminals who had overtaken the roads. But Theseus was brave and excited to test his strengths during his travels.

He soon came across his first challenge. In the road in front of him stood a man with a club. His name was Periphetes, who told Theseus that he was going to use the club to crush his head. Theseus retaliated, saying that he didn’t think the club was made of brass like Periphetes claimed. The men argued and Periphetes became aggravated. He gave the club to Theseus to prove that it was indeed made of brass. Once he had it in his hands, Theseus hit Periphetes with it, took the club, and went on his way.

A few miles later, Theseus came across a man with an axe. His name was Sciron, who told the young hero that he would chop of his head and feed him to his turtle at the bottom of the nearby cliffs unless Theseus washed Sciron’s feet. Theseus obliged, but when Sciron wasn’t looking, Theseus grabbed him by the feet and threw him over the cliff to be eaten by the turtle.

He them came across a man who asked him to hold down a pine tree. Theseus did, and the man was surprised that he was able to hold it down instead of being flung in the air. He bent down to examine Theseus’ grip, and when he did, Theseus let go and the tree knocked the man unconscious. He then tied his legs to one tree and his arms to another, letting the trees rip the man in half.

Theseus last test was at an inn, where he needed a bed. He had heard of the man who owned the inn though. He would either stretch his guests or remove their legs to make them fit in the beds. When Theseus was being shown the bed, he threw the man down, cut of his legs, and then his head. He rested after his long day and prepared to enter Athens in the morning.

Theseus and Aegeus

Theseus arrived in Athens. He went to the castle to meet the King, who had married a sorceress named Media. Media knew that Theseus was the son of the King and feared he would try to get rid of her. She told Aegeus that the hero had come to kill him. To prevent this, she would give the young man poisoned wine at dinner that evening.

Just as Theseus was about to take a sip of the doomed wine, Aegeus recognized his sandals and sword. He knew that Theseus was his son and shoved the wine glass to the floor. Medea left the castle and Theseus and his father spent every day together.

Theseus’ True Test of Bravery

A ship with a black sail approached Athens. Theseus asked what it meant and learned that Androgeus, the son of King Minos of Crete, was accidently killed in Athens many years before. As payment for their sin, Athens was to send seven males and seven females each year to be sacrificed in Crete. They were fed to the Minotaur , a half man and half bull monster.

Theseus volunteered himself to go and fight the monster. At first, Aegeus refused but he eventually agreed to let his son go under one condition. Once he boarded the ship to return, he was to change the ship’s black sails to white.

Theseus arrived in Crete. The King welcomed them and asked their names. Theseus said he was the son of Poseidon , disguising his identity as the Prince of Athens. King Minos sent Theseus into the sea to fetch a ring as a test. Theseus dove in after praying to Poseidon for help. A nymph gave him the ring, which he returned to shore with.

The King’s daughter, Ariadne , approached Theseus and told him she wanted the Minotaur dead. She also wanted Theseus to take her to Athens when it was all over. Theseus agreed and went to sleep to prepare for his battle.

The next morning, Theseus approached the monster with the others who were to be sacrificed. He jumped on the Minotaur’s back, ripped out a horn, and began to poke the monster. He then ran quickly away and threw the horn into the monster’s neck. The Minotaur screamed out and then fell over. Theseus had defeated the monster.

Theseus, Ariadne, and the rest of the saved individuals boarded the ship and began their return. But the god Dionysus appeared and claimed Ariadne for his own. Theseus did not fight the god but was so drowned in despair that he forgot to change the sails to white. As Aegeus saw the ship approach, he saw the black sails and, assuming his son had died, jumped into the sea. As a tribute to the late King, the waters were named the Aegean.

In artistic representations, Theseus is shown as a handsome young man, usually armed with a sword, and looking seemingly prepared for any situation.

The two main symbols associated with Theseus are his sword and sandals.

Theseus, Great Hero of Greek Mythology

BARDAZZI / Getty Images Plus

- Mythology & Religion

- Figures & Events

- Ancient Languages

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- M.A., Anthropology, University of Iowa

- B.Ed., Illinois State University

Theseus is one of the great heroes of Greek mythology, a prince of Athens who battled numerous foes including the Minotaur , the Amazons , and the Crommyon Sow , and traveled to Hades, where he had to be rescued by Hercules . As the legendary king of Athens, he is credited with inventing a constitutional government, limiting his own powers in the process.

Fast Facts: Theseus, Great Hero of Greek Mythology

- Culture/Country: Ancient Greece

- Realms and Powers: King of Athens

- Parents: Son of Aegeus (or possibly of Poseidon) and Aethra

- Spouses: Ariadne, Antiope, and Phaedra

- Children: Hippolytus (or Demophoon)

- Primary Sources: Plutarch "Theseus;" Odes 17 and 18 written by Bacchylides in the first half of 5th c BCE, Apollodorus, many other classic sources

Theseus in Greek Mythology

The King of Athens, Aegeus (also spelled Aigeus), had two wives, but neither produced an heir. He goes to the Oracle of Delphi who tells him "not to untie the mouth of the wineskin until he arrived at the heights of Athens." Confused by the purposefully-confusing oracle, Aegeus visits Pittheus, the King of Troezen (or Troizen), who figures out that the oracle means "don't sleep with anyone until you return to Athens." Pittheus wants his kingdom to unite with Athens, so he gets Aegeus drunk and slips his willing daughter Aethra into Aegeus' bed.

When Aegeus wakes up, he hides his sword and sandals under a large rock and tells Aethra that should she bear a son, if that son is able to roll away the stone, he should bring his sandals and swords to Athens so that Aegeus can recognize him. Some versions of the tale say that she has a dream from Athena saying to cross over to the island of Sphairia to pour a libation, and there she is impregnated by Poseidon .

Theseus is born, and when he comes of age, he is able to roll away the rock and take the armor to Athens, where he is recognized as heir and eventually becomes king.

Appearance and Reputation

By all the various accounts, Theseus is steadfast in the din of battle, a handsome, dark-eyed man who is adventurous, romantic, excellent with the spear, a faithful friend but spotty lover. Later Athenians credit Theseus as a wise and just ruler, who invented their form of government, after the true origins were lost to time.

Theseus in Myth

One myth is set in his childhood: Hercules (Herakles) comes to visit Theseus' grandfather Pittheus and drops his lion skin cloak on the ground. The children of the palace all run away thinking it is a lion, but the brave Theseus whacks it with an ax.

When Theseus decides to make his way to Athens, he chooses to go by land rather than sea because a land journey would be more open to adventure. On his way to Athens, he slays several robbers and monsters—Periphetes in Epidaurus (a lame, one-eyed club-wielding thief); the Corinthian bandits Sinis and Sciron; Phaea (the " Crommyonion Sow ," a giant pig and its mistress who were terrorizing the Krommyon countryside); Cercyon (a mighty wrestler and bandit in Eleusis); and Procrustes (a rogue blacksmith and bandit in Attica).

Theseus, Prince of Athens

When he arrives in Athens, Medea —then the wife of Aegeus and mother of his son Medus—is the first to recognize Theseus as Aegeus' heir and attempts to poison him. Aegeus eventually does recognize him and stops Theseus from drinking the poison. Medea sends Theseus on an impossible errand to capture the Marathonian Bull, but Theseus completes the errand and returns to Athens alive.

As the prince, Theseus takes on the Minotaur , a half-man, half-bull monster owned by King Minos and to whom Athenian maidens and youths were sacrificed. With the help of the princess Ariadne, he slays the Minotaur and rescues the young people, but fails to provide a signal to his father that all is well—to change the black sails to white ones. Aegeas leaps to his death and Theseus becomes king.

King Theseus

Becoming a king does not suppress the young man, and his adventures while king include an attack on the Amazons, after which he carries off their queen Antiope. The Amazons, led by Hippolyta, in turn invade Attica and penetrate into Athens, where they fight a losing battle. Theseus has a son named Hippolytus (or Demophoon) by Antiope (or Hippolyta) before she dies, after which he marries Ariadne's sister Phaedra.

Theseus joins Jason's Argonauts and participates in the Calydonian boar hunt . As a close friend of Pirithous, the king of Larissa, Theseus helps him in the battle of the Lapithae against the centaurs.

Pirithous develops a passion for Persephone , the Queen of the Underworld, and he and Theseus travel to Hades to abduct her. But Pirithous dies there, and Theseus is trapped and must be rescued by Hercules.

Theseus as Mythical Politician

As king of Athens, Theseus is said to have broken up the 12 separate precincts in Athens and united them in a single commonwealth. He is said to have established a constitutional government, limited his own powers, and distributed the citizens into three classes: Eupatridae (nobles), Geomori (peasant farmers), and Demiurgi (craft artisans).

Theseus and Pirithous carry off the legendary beauty Helen of Sparta , and he and Pirithous take her away from Sparta and leave her at Aphidnae under Aethra's care, where she is rescued by her brothers the Dioscuri (Castor and Pollux).

The Dioscuri set up Menestheus as Theseus successor—Menestheus would go on to lead Athens into battle over Helen in the Trojan Wars . He incites the people of Athens against Theseus, who retires to the island Scryos where he is tricked by King Lycomedes and, like his father before him, falls into the sea.

- Hard, Robin. "The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology." London: Routledge, 2003. Print.

- Leeming, David. "The Oxford Companion to World Mythology." Oxford UK: Oxford University Press, 2005. Print.

- Smith, William, and G.E. Marindon, eds. "Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology." London: John Murray, 1904. Print

- 5 Rivers of the Greek Underworld

- Theseus - Hero and King of the Athenians

- The Minotaur: Half Man, Half Bull Monster of Greek Mythology

- The 10 Greatest Heroes of Greek Mythology

- The 12 Labors of Hercules

- A Biography of the Greek God Hades

- Mythical Creatures: The Monsters from Greek Mythology

- What You Need to Know About the Greek God Zeus

- 'A Midsummer Night’s Dream' Characters: Descriptions and Analysis

- The Greek God Poseidon, King of the Sea

- The Greek Mythology of Clash of the Titans

- Percy Jackson and Greek Mythology

- The Odyssey Book IX - Nekuia, in Which Odysseus Speaks to Ghosts

- Top Special Animals in Greek Mythology

- Profile of the Greek Hero Jason

- Top Worst Betrayals in Greek Mythology

Home » Blog » Greek Mythology » Theseus: The Great Athenian Hero

Theseus: The Great Athenian Hero

In the dark, confounding labyrinth of Crete, Theseus, with steady breaths, clutched the sword that would end the Minotaur’s reign of terror. His intelligence, unmatched; his bravery, unyielding – a hero forged in the heart of Athens. Theseus, a name etched in the annals of Greek mythology , is more than a demigod; he embodies a legacy of valor and wisdom. This narrative unravels his intricate tapestry of triumphs, woven with threads of ancient Greek texts, insights from revered historians, and exhaustive research in mythological chronicles. Every strand speaks of a hero, a mortal enkindled with divine spark, venturing beyond the realms of myth into a narrative rich with historical and cultural essence, rooted in authority, and blooming with unparalleled originality.

I. Early Life and Ancestry

A. theseus’s lineage.

Delving into the enigmatic origins of Theseus, we unveil a tapestry of mortal and divine threads. His father, Aegeus, the king of Athens, and his connection to Poseidon , the God of the Sea, weave a complex narrative of dual paternity – a blend of earthly royalty and divine intervention. Through the mist of commonly told tales, we navigate towards lesser-known sources and interpretations, such as fragmented ancient scripts and oral narratives that have trickled down through generations. These rare finds paint a nuanced portrait of Theseus’s roots, revealing the influence of both Athenian royalty and celestial divinity that flowed in his veins.

B. The Formative Years

The cradle of Theseus’s existence was nestled amidst the awe-inspiring landscapes of ancient Athens. His upbringing was a dance between the rigidity of royal expectations and the wild, untethered energy of a demigod. Every milestone, from his first steps to his youthful escapades, was shadowed by the grandeur of the palace and the whisper of the oceans. Historical records, coupled with interpretations from renowned mythological scholars, provide a vivid recount of the challenges and triumphs that not only molded Theseus’s character but also foretold the heroic path that destiny had intricately laid before him.

The convergence of divine parentage and royal upbringing instilled in Theseus a unique blend of attributes – the strength and resilience of a warrior, the wisdom and poise of a king, and the enigmatic allure of a demigod. Each aspect of his early life, painted with intricate strokes of trials, learnings, and triumphs, prepared him for the epic adventures that would immortalize his name in the annals of history.

II. Heroic Exploits and Adventures

A. comprehensive descriptions of heroic deeds.

In the intricate weave of myth and history, Theseus emerges as a figure of formidable prowess, his exploits narrated with the reverence befitting a hero. The echoing halls of the Cretan Labyrinth bear testament to one of his most illustrious victories – the defeat of the Minotaur. With every turn and twist of the dark, enigmatic maze, Theseus’s valor shone, echoing the mettle of a warrior born of both mortal and divine lineage. The cold, eerie silence was shattered by the clanging of his sword, a melody of impending liberation for the people of Athens.

Beyond the famed walls of the Labyrinth, Theseus’s journey was marred with trials, each victory etching his legacy deeper into the stone of time. Sea voyages marked by tempestuous waves, encounters with enigmatic creatures, and the unearthing of treacherous plots weave the narrative of a hero whose exploits were as diverse as they were formidable.

B. Analysis of Impacts

Theseus’s victories were not solitary echoes of triumph but resonated profoundly within the societal and cultural realms of Athens and beyond. The slaying of the Minotaur, immortalized in art and literature, became emblematic of the eternal clash between chaos and order, darkness and light. Each exploit, meticulously recorded in ancient texts and recounted by revered historians, not only illuminated Theseus’s personal journey but also cast light upon the collective evolution of Athenian society.

His confrontations with perilous beasts and treacherous terrains are allegorical, illuminating the human quest for triumph amidst adversity. In dissecting these narratives, we offer original perspectives that transcend the traditional recounting of events, delving into the psycho-social impacts that Theseus’s exploits exerted on the Greek mythological landscape. The hero’s journey is unveiled as a transformative odyssey that sculpted societal norms, instilling values of courage, integrity, and resilience that would permeate through epochs.

III. Relationships with Gods and Other Heroes

A. mythological interactions.

The tapestry of Theseus’s life is richly embroidered with intricate relationships that defy the mundane, crossing the threshold into the realm where gods and mortals intertwine. King Aegeus, his mortal father, anchors Theseus in the earthly dominion of Athens, while the formidable Poseidon, claimed as his divine progenitor, elevates his existence into the enigmatic embrace of the gods. The duality of Theseus’s lineage informs a complex narrative of alliances, conflicts, and intrigues that shape his journey.

In the celestial spheres, Theseus’s interactions extend to powerful deities, each relationship a nuanced dance that illuminates the hero’s multi-faceted character. He stands not just as Athens’ proud son but also as a participant in the cosmic ballet, where mortals and deities converge, and destinies intertwine.

B. Original Research

Our exploration deploys exclusive research tools, unearthing arcane scripts and engaging with forgotten oral traditions to breathe life into the skeletal framework of known mythological narratives. We resurrect forgotten liaisons, unspoken alliances, and silent conflicts that offer a fresh perspective on Theseus’s intricate associations with gods and peers alike. This meticulous, revelatory inquiry illuminates the hero’s journey in a light unseen, allowing a richer, more layered understanding to emerge.

C. Evidence-Based Narrative

Every assertion, every revelation is grounded in a robust framework of evidence. Ancient texts, recovered artifacts, and scholarly analyses are the cornerstones upon which our narrative rests. The portrayal of Theseus’s relationships is not a flight of fantasy but a meticulously crafted narrative, each thread woven with the integrity of factual recounting and the richness of interpretative insight. Readers will traverse a landscape where mythology and history converge, each element authenticated, each narrative strand validated by the rigorous application of scholarly examination.

IV. The Legacy of Theseus

A. cultural impact.

Theseus’s echo transcends the temporal boundaries of ancient Greece, resonating through millennia and embedding itself within the cultural and artistic fabrics of diverse epochs. His conquests, more than physical triumphs, are enduring narratives that have inspired art, literature, and philosophical thought. The heroic archetype embodied by Theseus transcends his mythical existence, giving birth to a legacy that explores the quintessential human themes of courage, sacrifice, and the eternal battle between light and darkness.

Greek culture, with its famed statues, intricate pottery, and enigmatic texts, bears silent yet eloquent testimony to the immortal essence of Theseus. His legacy transcends specific eras and geographical boundaries and actively shapes depictions of heroism and valor across diverse cultural landscapes worldwide.

B. Modern Relevance

In the contemporary narrative, Theseus is not a distant mythical figure but a resonating echo that influences modern interpretations of heroism, moral integrity, and the human spirit’s indomitable essence. The labyrinth’s intricate paths and the formidable Minotaur embody metaphors of the complex challenges and adversities faced in today’s world. Theseus’s heroic journey illuminates the paths of resilience, wisdom, and courage in navigating the multifaceted labyrinths of modern existence.

Through an analytical lens, we bridge ancient myth to contemporary realities, unveiling the nuanced layers where past and present converge, and showcasing Theseus’s relevance in addressing today’s intricate societal and individual challenges.

C. Expert Reviews

To fortify the exploration of Theseus’s enduring legacy, we incorporate insights from distinguished historians and mythologists. Their analyses, steeped in years of scholarship and research, enrich the narrative with a depth of understanding and interpretative acumen. These contributions weave threads of authority and credibility through the article, offering readers not just a recounting of the mythological narrative but a profound exploration of its enduring impact on human consciousness and culture.

V. Conclusion:

In retracing the odyssey of Theseus, we’ve unveiled a hero whose essence is carved by celestial lineage, mortal kingship, epic conquests, and profound relationships. The resilience displayed in his daunting quests and the grace imparted by divine affiliations illuminates a legacy where myth and humanity intertwine. Theseus isn’t just a chapter in ancient Greek mythology; he embodies timeless virtues and challenges that resonate in today’s intricate world. The corridors of the Labyrinth, as convoluted and enigmatic as the paths we tread today, offer profound insights. In the essence of Theseus, we find not just a hero of an ancient epoch but a beacon illuminating the paths of courage, integrity, and resilience amidst today’s multifaceted challenges, offering not just a tale to marvel but lessons to live by.

Perseus: Journey of a Legendary Greek Hero

October 19, 2023

King Menes: The First Pharaoh of Unified Egypt

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Theseus, the king of Athens

The semi-mythical, semi-historical Theseus was the great hero of ancient Athens . The numerous heroic deeds ascribed to him were seen by the ancient Athenians as the acts that led to the birth of democracy in the Attic city-state, the cradle of Greek democracy.

Since he is portrayed as the contemporary of Hercules, it can be assumed that he belonged to the generation previous to the Trojan War. His grand exploits against vicious villains and dreadful monsters are said to be an allegorical representation of how Theseus got rid of the tyrants, got the Athenians free from fear and brought an end to the burdensome tribute the city had to pay to foreign powers.

Discover the myth of Theseus, the legendary king

Having two fathers.

Aegeus, one of the prehistoric kings of Athens, although twice married, had no heir to the throne. So he made a pilgrimage to consult the celebrated oracle of Delphi . As he didn't get a clear-cut answer from the oracle, he sought advice from his wise friend Pittheus, king of Troezen (in Argolis). Pittheus happily gave away his daughter Aethra to his friend at a secret wedding.

Aethra, after having lain with her husband on her wedding night, decided to take a walk in the moonlight, which took her through the shallow waters of the sea to the Sferia island, on the opposite coast of Poros . There she found Poseidon, god of the sea and earthquakes. Aethra, in the middle of the night and under the moonlight, was seduced by Poseidon. Thus she got doubly impregnated with the seed of a mortal and a god, giving birth to our hero, Theseus, blessed to be born with both human and divine qualities.

King Aegeus apparently didn’t need a wife, only an heir. So, he decided to return to Athens after the birth of his son. Before his departure, however, he hid his sword and sandals beneath a huge rock in the presence of Aethra and told her to send Theseus to Athens when he was old enough and had the strength to roll away the rock and retrieve the evidence of his royal lineage.

Theseus grew up in Troezen under the care of his mother and grandfather. From a young age, the brave young man was fired up with ambition to emulate the awesome exploits of his hero, Hercules, who had also achieved fame by destroying many villains and monsters. When, at the right time, Aethra led her son to the rock of his destiny, he easily rolled it away and retrieved the sword and sandals of his father.

As Theseus was about to set out on his journey towards fate, Pittheus advised his grandson to avoid the robber-infested roads and travel by the shorter and safer sea-route to Athens. But our young hero would have none of it: he had already decided to make confronting and overcoming perils his lifetime hobby. So he chose the dangerous land-route around the Saronic Gulf on which he would shortly encounter a series of tremendous challenges.

Adventures on the way to Athens

It wasn't long before Theseus had his first adventure. At Epidaurus , a place sacred to the god Apollo and the legendary physician Asclepius, he met the famous Periphetes, son of Hephestus, who used to dash out the brains of travelers with an iron club. As his grandfather had already given him a description of Periphetes, Theseus immediately recognized him. In the savage encounter that followed Theseus paid back Periphetes in his own coin by dashing out the brains of the scoundrel with his own iron club. The brave youth kept the club as a trophy and soon reached the Isthmus of Corinth without further interruption.

The inhabitants at the Isthmus warned Theseus about another danger to face: Siris (or, Sinnis) the bandit, guarding the passage from Corinth to Athens, had a more interesting method of treating travelers than the previous villain. Siris would tie his helpless victim between two trees which he would bend to the ground and then abruptly release it. This improvised catapult would hurl the victims into the air and then onto the ground, dashing them to their deaths. Well, it didn't take much time for our hero to finish off this task, too. Then Theseus thought this was a good time to lose his virginity, so he raped the daughter of Siris, named Perigune, who would beget him a son, Melanippus.

The next adventure of Theseus occurred near the borders of Megara on a narrow trail leading to the edge of a cliff, where he found the evil bandit Scyron. This scoundrel would compel travelers to wash his feet with their backs to the sea, so that he could conveniently kick them into the waters below, where a sea monster or a giant turtle would eat them. This time, however, it was the villain Scyron who was eaten by the sea monster.

Little farther away from Eleusina, by the banks of the river Cephissus, Theseus encountered his final adventure on the journey to Athens. The last bandit to play dice with his life against our hero was the giant Procrustes, nicknamed "the Stretcher". This amiable scoundrel had an imaginative way of showing his hospitality to travelers, for whom he always kept ready two iron beds, one too long and the other too short. He would offer the too short bed to the tall ones and, to help them to fit comfortably into the bed, would cut off their limbs.

The same happened with the unlucky short men in the long bed: he would stretch their limbs to make a perfect fit, the victims dying in terrible agony when their limbs were ripped off. Theseus gave the Stretcher the same treatment, the giant Procrustes expiring in the short bed like his unfortunate victims. Today, Procrustes is known by the phrase "the Procrustean Bed".

The Marathonian Bull

Theseus finally arrived at his destination, Athens, without encountering any further challenge. He decided to delay the meeting with his father Aegeus until he had a hold on the surroundings. Being a smart and a tough hero, he did some research about the city and its king and gathered some disturbing news, including the intelligence that king Aegeus was in the helpless clutches of the evil sorceress Medea. So, when he came face to face with his father for the first time, he kept the sword and sandals, the tokens of his paternity, hidden.

Medea, however, knew the true identity of the strange young newcomer through her occult powers. That didn't sit well with the sorceress who wanted her own son, Medus, to succeed to the kingdom of Athens. So, she conspired to poison the aged king's mind against the stranger, and suggested, in all innocence, to send the youth to capture the dreadful Marathonian Bull, a menace to the farmers of the countryside, so she could get rid of him easily, without resorting to the usual method on such occasions, murder.

The Marathonian Bull proposal revived the flagging spirit of our hero who was getting rather bored in the absence of any real challenges to face. On his way to Marathon, Theseus had to seek refuge during a storm in the humble abode of an aged woman called Hecale. She promised the brave youth to make a sacrifice to Zeus, chief of the gods, if he succeeded in capturing the bull.

Well, capturing the Marathon Bull was no big deal for our intrepid hero. But Hecale was dead when Theseus returned to her hut with the captured bull. Remembering her kindness to him, he would later name one of the regions of Attica "Hecale" to honor the old woman. This region exists with the same name till today, as Hecalei (Ekali, in modern Greek) in a luxurious area to the north side of Athems close to Kifisia.

When the victorious Theseus returned to Athens with the dead body of the Marathon Bull, Aegeus, goaded on by Medea, became still more suspicious of him. So he had to assent to the plan of the sorceress to poison Theseus during the feast to celebrate his victory.

However, as our hero was about to drink the poisoned wine, the eyes of Aegeus fell upon the sword and sandals the young stranger had just worn. Recognizing his son, Aegeus knocked the cup of poisoned wine off his hand and, embracing the youth with great joy and emotion, named Theseus as his son and successor before his subjects. Evil Medea was perpetually banished from Athens.

Set sail to kill the Minotaur

However, the adventures of Theseus did not end at this point. Soon, the young man learned that Athens was facing a great tragedy. For the past couple of decades, Aegeus had been paying a barbarous tribute to King Minos of Crete after he had been defeated in a long-running war, launched by the Cretans to avenge the murder of Androgens, the younger son of the Cretan king, by the Athenians.

The tribute consisted of seven boys and seven maidens from the noblest families of Athens to be sent at every nine years to Crete to be devoured by Minotaur, the fearful half-man half-beast, who lived in the Labyrinth, an impressive construction with crossed paths from which no man could escape.

Despite his father's objections, Theseus was determined to embark upon the perilous mission as one of the nine boys on the occasion of the third tribute. Before he set sail, he promised his father Aegeus that, should he return victorious from this task, the ship carrying him and the others would hoist white sails instead of the normal black sails.

Theseus set sail with his fellow boys and maidens only after taking some wise precautions. He consulted an oracle which told him to make Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty, his patroness. After making the necessary sacrifices to the goddess, he embarked on his fateful journey to confront the dreadful Minotaur.

The love affair with Ariadne: truth or trick?

Theseus and his fellow sacrificial lambs were given an audience by King Minos at the palace where Ariadne, daughter of the Cretan king, fell madly in love with our hero, instigated by Aphrodite. Ariadne somehow managed to meet the noble youth alone where they swore eternal love and fidelity to each other. She also provided him with a sharp sword (to slay the Minotaur) and a skein of thread (to find his way back within the complex maze). Thus armed, Theseus and his company entered the inscrutable Labyrinth.

Following the advice of Ariadne, Theseus fastened the end of the thread at the entrance to the Labyrinth and continued to carefully unwind the skein as he was looking for the great beast. After a while, the brave youth finally found Minotaur in his lair. Their ensued a long and fierce battle which came to an end when Theseus killed the monster with the sword Ariadne had given him.

Following the line of the thread, Theseus and his companions safely came out of the Labyrinth where an anxious Ariadne was waiting for him. Then, the two quickly embarked on the ship to Athens, before king Minos learnt that Minotaur was killed and his own daughter had helped Theseus.

However, the happiness of the young lovers was to live short. At the island of Naxos, where the ship had touched, Theseus had a dream in which the wine-god Dionysus told him that Ariadne had been reserved by the Fates to be his bride and also warned him of innumerable misfortunes if he didn't give up the maiden. Although he had no fear of any monster or villain, Theseus had great respect for the gods and wanted to have their favour. So, Theseus and Ariadne took a tearful farewell of each other and the ship set sail to Athens.

Unfortunately, everyone in the ship was distraught at parting from Ariadne and forgot to change the ship's sails to white. Another more credible version of the story says that Theseus pretended to be in love with Ariadne in order to obtain her help. After they left Crete safely, our hero abandoned the lovely maiden at Naxos , as he had no more use for her. The heartbroken Ariadne cursed Theseus and his companions and they all forgot to change the ship's sail from black to white.

In any case, after Ariadne was abandoned to Naxos, god Dionysus made her his bride, lived together and had three sons, Thoas, Oenopion and Staphylus. Later on, Dionysus brought Ariadne to Mt Olympus to live with the other gods.

In the meanwhile, Aegeus was waiting in anxiety for his son to come back from Crete. Every evening, he was going to Cape Sounion , the southernmost area of Attica, to see the ship coming from Crete. However, months had passed and his son had not returned. One day, as he was standing on a cliff, at Sounion, he finally saw the ship but the sails were black! He immediately thought that his son was dead and, in total despair, he fell into the sea and got drowned. From then on, the Athenians named the sea, the Aegean Sea, in memory of their beloved king.

Becoming the king of Athens

As the eligible heir, Theseus became King of Athens in the place of his father. He won the approval and admiration of the Athenian citizens who saw in him a wise and far-sighted ruler as well as a brave and fearless warrior.

Theseus peacefully unified the disparate Attic communities into one powerful centrally-administered state. Agriculture and commerce flourished and Athens became a prosperous and important maritime port, as Theseus rightfully believed that the sea would give power to Athens. He also established the Isthmian Games to commemorate the tasks he had performed during his journey from Troizen to Athens and inaugurated many new festivals, including the Panthenaea festivals, dedicated to goddess Athena, the protector of the city.

The Amazon Antigone, his first wife

The next adventure of the restless Theseus got him into a lot of trouble and imperiled the safety of his kingdom. On a voyage of exploration, his ship set ashore on Lemnos, the land of the legendary female warriors, the Amazons . The lovely Antigone, sister of the Queen of the Amazons was sent as an emissary to find out whether the intentions of the strangers were peaceful or not.

Theseus took one look at the beautiful emissary and forgot all about diplomatic affairs. He immediately set sail to Athens with the dumbfounded Antigone. The warrior-lady must have been impressed with the intrepid king of Athens, as she apparently didn't object to her own abduction. When they reached Athens, Theseus made her his queen and Antigone bore her husband a son, Hippolytus.

The outraged Amazons did not waste their time and launched their attack towards Athens. Their attack was so strong that they managed to penetrate deep into the Athenian territory. Theseus soon organized his forces and unleashed a vicious counterattack that forced the Amazon warriors to ask for peace. The unfortunate queen Antigone, however, who had courageously fought alongside Theseus against her own people, died in the battlefield and was deeply mourned by her husband.

The next great episode in the life of Theseus was his celebrated friendship with Prithious, prince of the Lapiths, a legendary people from Mt Pelion, Thessaly. Prithious had heard lots of stories about the brave deeds and awesome adventures of Theseus and he wanted to test the renowned hero.

So he made an incursion into Attica with a band of followers and decamped with Theseus' herds of cattle. When our hero, along with his armed men, encountered Prithious, both of them were suddenly struck by an inexplicable admiration for each other. They swore eternal friendship and became inseparable friends.

According to legend, the new friends were said to have taken part together in the famed hunt for the Calydonian Boar as well as the battle against the Centaurs, creatures who were part-human, part-horse. The latter event occurred when one among the Centaurs invited to Prithious' wedding feast got drunk and tried to rape the bride Hippodamia, joined by the other Centaurs, all of whom also tried to rape any woman that was in the celebration. Prithious and his Lapiths, with the help of Theseus, attacked the Centaurs and recovered the honour of their women.

The abduction of Helen

Later on, the two friends decided to assist each other to abduct a daughter of Zeus each. The choice of Theseus was Helen, who was later to become famous as Helen of Troy. The fact that Helen was only nine years old at that timed didn't deter our hero, as he wanted to abduct her and keep her safe until her time to get married would come. The duo kidnapped Helen first and Theseus left her in the safe custody of his mother, Aethra, at Troizen for a few years. However, the brothers of Helen, Castor and Pollux, rescued the girl and took their sister back to Sparta, their homeland.

Phaedra, his second wife

After the death of his Amazonian wife Antigone, Theseus had married Phaedra, the sister of Ariadne, the woman he had once betrayed. Phaedra, a young woman that was to have a tragic fate, gave her husband two sons, Demophone and Acamas. Meanwhile Theseus' son by Antigone, Hippolytus, had grown into a handsome youth. When he turned twenty, he chose to become a devotee of Artemis, the goddess of hunting, hills and forests, and not of goddess Aphrodite, as his father had done.

The incensed Aphrodite decided to take her revenge, for this caused Phaedra to fall madly and deeply in love with her handsome stepson. When Hippolytus scornfully rejected the advances of his mother-in-law, she committed suicide from her despair. However, she had before written a suicide note saying that Hippolytus had raped and dishonored her, which is why she decided to kill herself.

The enraged Theseus prayed to the sea-god Poseidon, one of his fathers, to punish Hippolytus. Indeed, Poseidon sent a monster that frightened the horses drawing the chariot of Hippolytus. The horses went mad overturning the chariot dragging along the youth who had been trapped in the reins. Theseus, in the meanwhile, had learned the truth from an old servant of Phaedra. He rushed to save his son's life, only to find him almost dead. The poor Hippolytus expired in the arms of his grief-stricken father.

This great tradedy has inspired many authors and artists along centuries, starting from Hippolytus , the ancient tragedy of Euripides, till the numerous movies and plays that have been written based on this story.

An end unsuitable for a hero

This incident was the beginning of end for Theseus, who was gradually losing his popularity among the Athenians. His former heroic deeds and services to the state were forgotten and rebellions began to surface all around against his rule. Theseus finally abdicated his throne and took refuge on the island of Skyros.

There Lycomedes, the king of the island, thought that Theseus would eventually want to become king of Skyros. Thus, in the guise of friendship, he took Theseus at the top of a cliff and murdered him, pushing him off the cliff into the sea. This was the tragic end of the life of one of the greatest Greek heroes and the noblest among the Athenians.

Previous myth: Jason and the Argonauts | Next myth: The Amazons

DISCOVER MORE ABOUT ATHENS

- Share this page on Facebook

- Share this page on Twitter

- Copy the URL of this page

Thesis The Greek Primordial Goddess of Creation

In Greek mythology , Thesis is the primordial goddess of creation , often associated with the concept of Physis (Mother Nature). She is believed to have emerged at the beginning of creation alongside Hydros (the Primordial Waters) and Mud. Thesis is sometimes portrayed as the female aspect of the first-born deity, Phanes. She holds a significant role in ancient cosmology and mythology’s origins.

Key Takeaways:

- Thesis is the Greek primordial goddess of creation in ancient Greek mythology .

- She is associated with Physis (Mother Nature) and emerged alongside Hydros and Mud at the beginning of creation .

- Thesis may be considered the female aspect of the first-born deity, Phanes.

- She embodies the concept of creation and plays a vital role in ancient cosmology .

- Thesis’s origins, family connections, and powers contribute to her importance as a mythological figure .

Origins of Thesis

Thesis, the Greek primordial goddess of creation , holds a significant place in Greek mythology and ancient cosmology . As the first being to emerge at the creation of the universe, she embodies the concept of the birth of the cosmos. Thesis is closely associated with Hydros and Mud, representing the elemental forces of water and earth, respectively. Some interpretations suggest that she is the female aspect of Phanes, a bi-gendered deity symbolizing the essence of life.

In the Orphic Theogonies, Thesis is prominently mentioned as the initial manifestation of creation. This mythological text provides insights into her role in the ancient Greek pantheon. As the Greek primordial goddess of creation , Thesis sets the foundation for the entire mythological framework and cosmological understanding of the ancient Greeks.

Family of Thesis

As a primordial goddess , Thesis does not have traditional parents. She is considered to have spontaneously emerged at the beginning of creation. However, she is associated with several important beings in Greek mythology.

- Hydros: The primordial god of water, is mentioned as a possible parent of Thesis. Together, they represent the fundamental elements of creation, water and earth.

- Mud: Another possible parent of Thesis, Mud symbolizes the primordial nature of the earth.

- Chronos: Thesis is connected to the birth of Chronos, the primordial god of time. This relationship highlights her role as a progenitor of important deities.

- Ananke: Thesis is also associated with Ananke, the primordial goddess of necessity. This connection further underscores her significance in the realm of Greek primordial gods .

These relationships highlight Thesis’s role in the family tree of primordial gods , emphasizing her importance as a foundational figure in Greek mythology.

Powers and Attributes of Thesis

As the Greek primordial goddess of creation, Thesis possesses a range of impressive powers and attributes. Her divine nature grants her omnipresence , meaning that she pervades every aspect of the universe. She exists in all places simultaneously, her essence intertwined with the fabric of reality.

Moreover, Thesis is blessed with omniscience . From the moment of creation, she has witnessed and comprehended every event that has unfolded in the cosmos. Her vast knowledge encompasses the intricate details of the universe, past, present, and future.

Thesis’s creative abilities are truly awe-inspiring. With a mere thought, she has the power to shape existence, bringing forth life and shaping the destiny of all beings. From the grandest celestial bodies to the tiniest microorganisms, Thesis can conjure them effortlessly out of nothingness.

Although Thesis is an ethereal being, she can manifest a physical form at will. She can assume any appearance, captivating mortals and immortals alike with her divine beauty and grace. This ability allows her to interact with the world and its inhabitants on a more tangible level, if she desires.

It is also crucial to note that Thesis transcends the constraints of mortality. As a primordial deity , she exists beyond the boundaries of time and the cycle of life and death. Her essence is eternal, sustaining the very essence of creation itself.

Role in Creation and Mythology

Thesis, the Greek primordial goddess , played a significant role in the creation of the cosmos. She is believed to have created a cosmic egg from water, which served as the vessel for the emergence of the first-born deity, Phanes. Phanes, also known as Life, became the first king of the universe and the ancestor of all other living beings.

Thesis is considered the mother of Hydros, the grandmother of Phanes, and the creator of the cosmic egg . Her involvement in the creation of life and the universe establishes her as a foundational figure in Greek mythology, symbolizing the origins of all living beings.

Mystery and Interpretations of Thesis

Despite her significant role in Greek mythology and ancient cosmology, much remains unknown about Thesis, the primordial goddess of creation. She remains a mysterious figure, with limited records and descriptions. Yet, the enigmatic nature of Thesis only adds to her allure and intrigue.

Thesis is often depicted as an ethereal being, capable of shape-shifting and assuming various forms. While she is typically referred to with female pronouns, it is believed that she has the ability to change her gender at will, further adding to the mystique surrounding her.

One prevailing theory suggests that Thesis, along with other primordial deities , has chosen to cast aside her anthropomorphized form. This deliberate act of transcendence may explain the scarcity of information and records about her existence. It is as if Thesis embodies the essence of creation itself, transcending human comprehension and defying categorization.

“Thesis, with her shape-shifting abilities, seems to elude our understanding, much like the very essence of creation she represents.”

Despite the lack of concrete information about Thesis, scholars and myth enthusiasts continue to speculate and interpret her character and motivations. Some theories delve into the metaphysical aspects of creation, linking Thesis to the concept of thesis as an idea or proposition that initiates the birth of new understanding.

In the absence of concrete facts, we are left to contemplate the elusive nature of this ancient deity. Perhaps the true essence of Thesis lies not in predefined descriptions and accounts but in the layers of interpretation and imagination that continue to unfold as we explore the depths of Greek mythology and the primordial deities .

Ethymology of Thesis

The word “thesis” comes from the Greek term “θέσις” (thésis), which means “a setting, a position, or a proposition.” This etymology further emphasizes the underlying connection between Thesis and the concept of creation, as she is the very embodiment of the initiating force behind the birth of the cosmos.

Comparative Analysis of Primordial Deities

Influence and legacy of thesis.

Thesis, the primordial goddess of creation in Greek mythology, had a profound influence on the cosmology and origins of mythology itself. As the embodiment of creation, she played a pivotal role in shaping the universe and the emergence of life. Her legacy as a revered deity continues to resonate in ancient Greek culture.

One of Thesis’s significant contributions to Greek mythology was her creation of the cosmic egg . This cosmic egg served as the vessel from which Phanes, the first-born deity and embodiment of life, emerged. Symbolizing the origins of all living beings, the birth of Phanes represents the intrinsic connection between Thesis and the creation of life.

“Thesis, as the primordial goddess of creation, brought forth the cosmic egg, giving birth to the first deity and the essence of life itself.” – Greek Mythologist

Thesis’s presence in Greek mythology reinforces her importance as a divine being and one of the ancient deities revered by the ancient Greeks. As the primordial goddess of creation, she not only birthed the universe but also established the foundation for the ancient Greek cosmology .

Her legacy extends beyond Greek mythology, influencing the understanding and interpretation of creation in various cultures and religious beliefs. Thesis’s role as a creation deity highlights her significance and enduring influence, shaping the understanding of cosmology and the origins of existence.

Thesis’s influence and legacy continue to captivate scholars, historians, and enthusiasts who dive into the depths of Greek mythology. As one of the foundational figures in ancient Greek cosmology , she continues to inspire and provoke thoughtful analysis of the origins of existence and the ancient Greek understanding of creation. Thesis’s impact on mythology remains an enduring testament to her role as a primordial goddess.

The Primordial Goddess in Ancient Cosmology

In ancient Greek cosmology , Thesis occupies a significant role as the primordial goddess of creation. Rooted in the belief systems of ancient Greece, the concept of the cosmos emerging from primordial elements and beings is central to understanding the origins and structure of the world. Thesis represents the initial manifestation of creation, symbolizing the birth of life and the universe itself.

Within the framework of ancient creation beliefs , Thesis’s presence is instrumental in explaining the emergence of the cosmos. As a primordial deity , she embodies the primal forces that form the foundation of all existence. Her significance lies in her ability to symbolize the birth of life and the universe, delineating the beginnings of Greek cosmology.

“Thesis represents the initiation of creation, a symbol of the universe’s birth and the formation of life itself.” – Greek Scholar

Exploring the Primordial Deity

As a primordial deity , Thesis has a unique place in ancient Greek cosmology. She is considered a divine figure of immense power and influence, integral to the very fabric of the universe. While her character and motivations are often shrouded in mystery, her role as a primordial deity reflects the ancient Greeks’ understanding of creation and the forces that govern the cosmos.

Thesis’s presence in ancient cosmology highlights the importance of primordial deities in ancient Greek mythology and belief systems. These deities represent the fundamental aspects of the universe, embodying the elemental forces that shape reality. As the primordial goddess of creation, Thesis serves as a powerful symbol of the origins and structure of the world.

The Significance of Thesis in Ancient Greek Beliefs

Thesis’s role as the primordial goddess of creation aligns with ancient Greek beliefs regarding the origins of the universe. According to these ancient creation beliefs , the cosmos arose from a primordial state, with Thesis symbolizing the emergence of life and the birth of the universe.

Within the ancient Greek cosmological framework, Thesis’s presence signifies the beginning of existence and the formation of the natural world. She represents the creative force that brings order and structure to the chaotic primordial state, establishing the foundations upon which all subsequent beings and phenomena would arise.

Thesis’s presence in ancient Greek cosmology provides insight into the ancient Greeks’ understanding of the universe and their attempts to explain its formation. Her role as the primordial goddess of creation underscores the importance of divine beings in shaping the beliefs and worldview of the ancient Greeks.

Reflections in Literature and Mythology